#Max Beerbohm

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Web Treasure from the Wayback Machine:

The Enoch Soames Society's web pages. This will mean almost nothing to almost everyone. But I wish I'd found this site and linked to it when it was live, long long ago.

314 notes

·

View notes

Text

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

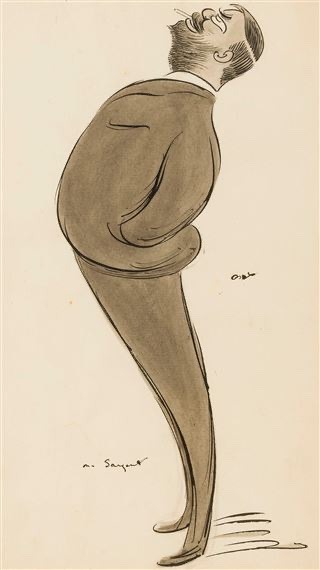

Oscar by Max Beerbohm.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Max Beerbohm, John Singer Sargent, 1909

Max Beerbohm, Mr. Sargent, circa 1900

#Max Beerbohm#john singer sargent#caricature#caricature artist#caricature art#illustration#english artist#english art#british art#british artist#british illustrator#art on tumblr#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#tumblr art#aesthetic#beauty#tumblrstyle

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1: Dim And Remote The Joys Of Saints I See (1869-1895) -- Part II

The trouble was not of conscience alone. Over the next years of his life, Robbie came to realise the hefty price he shall pay for being unapologetically homosexual in an intensely homophobic society.

By the accounts of those who knew him, Robbie was a short, delicate, and somewhat feminine-looking boy in his youth. Arthur Humphreys, a London bookseller who had known Robbie since the 1880s, remembered him as a ‘pathetically pale’, ’very delicate looking’ youth who sported flowery ‘Liberty’ ties and had ‘a tendency to be aesthetic in his dress’. Alfred Douglas, who had known him since the early 1890s, described him as an ‘attractive’ but ‘rather pathetic-looking little creature’ resembling ‘a kitten’. Rupert Croft-Cooke, who had probably heard much about Ross from Douglas, wrote that ‘Robert Baldwin Ross was an amusing little queen’ and ‘an invert’, who liked ‘older men of intelligence and social position’ and ‘looked for soldiers to play male to him’. And Neil McKenna went as far as saying that ‘[t]his slender, attractive and impulsive boy was a beacon for men who were attracted to younger men or boys and who often wanted to anally penetrate them.’. We may thus reasonably presume that Robbie’s refusal to adhere to the masculine norms of the day made him easy target for bullying, which was compounded by the fact that he never deliberately concealed his sexuality. Indeed, Richard Ellmann briefly mentioned that even before he got into university, Robbie had been ‘beaten for reading Wilde’s poems’, which were already considered effeminate if not homosexual.

In 1888, Robbie got into King’s College, University of Cambridge to study History. He was unabashedly progressive in a College known to be ardently conservative in his time, and he was not afraid of voicing controversial opinions. For instance, in support of King’s recent changes in admissions procedure to admit non-Etonians, Robbie wrote:

…however much the lovers of Eton, and those whose conservative prejudices are something more than mere sentiment, may regret the admission of non-Etonians into the place, we believe it was the salvation of the college, for in these advanced days an exclusively Etonian college is impossible for Cambridge. The change naturally brought evil with good, and among those who battered at the doors for admission under the new regulations, there came some of the most undesirable Undergraduates that could well be imagined. Not only long-haired, but the short-haired and the no-haired came — the purely social and the socially pure.

Already estranged from most of his Eton-educated peers by the fact that he had not attended a public school, Robbie’s opinionated nature, and most likely also his visibly queer outlook, infuriated the public school boys at King’s, who were determined to teach him a lesson by violence. Six months after he got into Cambridge, in one freezing evening, Robbie was dragged from the dining hall all the way to the college lawn, manhandled by six students, and ducked into the icy cold college fountain.. This, as Maureen Borland pointed out, could ‘well have resulted in the victim dying of pneumonia’ in Victorian times. The College was entirely unsympathetic towards Robbie: the six assailants were granted the honour to dine with a Tutor right after they left Robbie brutalised and shivering on the college lawn; and adding insult to injury, three days after the incident, the College decided that both the assailants and the assaulted had been guilty of breaking College rules, so no further action was to be taken.

The bullying and the miscarriage of justice left Robbie severely traumatised. According to Oscar Browning, then the Fellow for History at King’s, Robbie suffered ‘a violent brain attack’ as the result of ‘outrage preying on his mind’. This was likely an euphemistic under-statement given the Victorian attitude towards mental illness. By some accounts, Robbie was suicidal after the incident and had to be brought home from university. Though he returned to Cambridge two months later and managed to wrangle a reluctant apology out of his assailants through persistent effort, he never fully recovered from the traumatising incident and had recurrent episodes of measles, pneumonia, and mental breakdowns afterwards. Moreover, perhaps realising that he would forever remain an outcast in an institutionally homophobic college, eventually Robbie decided to drop out of Cambridge. The decision could hardly have been an easy one, for, prior to the incident, Robbie had enjoyed Cambridge a great deal.

After dropping out of Cambridge, Robbie made the monumental decision to come out to his family. It was an unbelievably courageous act in 1889, only four years after the notorious ‘Labouchere Amendment’ made all homosexual acts punishable by up to two years of imprisonment and hard labour, on top of the already draconian (though unenforceable) Offences against the Person Act 1861 which punished sodomy by life imprisonment. Few in his time were as brave. As Neil McKenna wrote, Robbie was one of the extremely few late-Victorian men who were open with their families about their sexuality since a young age and made no ‘prolonged attempts to divert his passions towards women’ Indeed, as we shall see later on, Robbie never considered marrying to conceal his homosexuality and probably tried to dissuade his homosexual friends from doing so. However, McKenna’s claim that there was no doubt or self-recrimination but only ‘joyous acceptance’ on Robbie’s parts went a bit too far: as a young adult made suicidal by violent homophobia, it was highly unlikely that he did not struggles before coming out to his family.

We would never know what was going on in Robbie’s mind back then. Was he trying to explain to his family his decision to drop out of Cambridge? Was he crying out for understanding and support? Was he defying a hostile world full of harsh prejudices? Or was he simply sick and tired of concealing himself? As with many other parts of his story, we could only guess.

Nor do we know exactly how his family reacted. Biographers had different ideas: Bogle did not record any significant reaction and merely said matter-of-factly that his family found him a job in Edinburgh not long after he left Cambridge; Borland wrote that his family was ‘distressed’ and tried to ‘force him to change his mode of life’ by throwing him out; and Fryer claimed that his brother Aleck and his mother were not judgemental about his sexuality, though his younger sister Lizzie was vehemently against it. I believe Borland’s theory is more credible. For one, his brother Aleck wrote to Oscar Browning saying that: ‘He [Robbie] must leave home…my present idea is to leave him to his own devices. I think it would be much better for him if he had to make his own plans and carry them out himself.’ These euphemistic words hardly belie the harshness of the deed: though Robbie later proved himself capable of ‘making his own plans and carrying them out’, it hardly justified his family’s decision to banish him to Edinburgh at a time when he was distressed, vulnerable, and desperately in need of care. Secondly, the cold and puritan Edinburgh hardly suited Robbie’s constitution, and the job Aleck found him was a minor editorial position with a bunch of ‘sports-loving, hard-drinking, nationalistic young men’ whom Robbie probably did not find pleasant. It is therefore highly unlikely that Robbie willingly took up the job. Thus it is reasonable to postulate that after being bullied out of Cambridge, Robbie was thrown out by his otherwise loving family for his sexuality and left to fight the battles of life without support.

We could only imagine how difficult it must have been: he was a teenager on the cusp of adulthood, had his education disrupted, wronged by the world, cast aside by his own family, and left stranded in an unfamiliar city. His health suffered, and he became so unwell that he had to be brought back to London after just a year. Yet, from his humble lodging in Rutland Square, Robbie was still writing to his former supervisor at Cambridge voicing his indignation and articulating his longing for justice. This stubborn tenacity never left him in his subsequent years.

With his tenacity and his nascent genius for friendship, Robbie survived the harsh ordeal and made his first friends in literary London over the next couple of years. Foremost in his connections was, of course, Oscar Wilde, which shall be the focus of the next section. Through Oscar, Robbie connected with other ‘disciples’ of Wilde and became part of the 1890 group —— that group of liberal and libertine queer young men wearing green carnations and setting the fashion of the age —— who included Reggie Turner, Max Beerbohm, and of course, Alfred Douglas. According to Max, the group found Robbie ‘cozy and useful’.

Following Wilde, Robbie befriended More Adey at around 1890, an Oxonian expelled from Keble College for his conversion to Catholicism. Adey was eleven years older than Robbie and shared much of his artistic taste. In 1891 they collaborated on a new edition of Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Maturin (Oscar Wilde’s great uncle) and referred to themselves as two halves of the same person. In that same year they began cohabiting and would lived together for the next fifteen years. Nobody can conclusively ascertain the nature of their relationship, some maintained that they were but platonic roommates who never shared a bed, whilst others believed that some form of long-term romantic relationship must have sustained their prolonged cohabitation. The only account of their interaction comes from Siegfried Sassoon, who knew Ross and Adey later in their lives. According to Sassoon, Adey was a kind but slightly unkempt and reclusive man with ‘lustreless dark eyes’ and a beard which looked ‘a bit moth-eaten'. After spending so long living with Robbie, the two men began resembling each other in their habits and mannerisms. He also had a ‘customary chair’ in Robbie’s flat even after they ceased to live together, and would shuffle into Robbie’s conversations late at night to ramble about the failures of the British government in his chair with no awareness that ‘two o’clock in the morning was the wrong hour’, whilst Robbie would tolerate his quirks and sit up with him regardless of the hour.

Then, in 1892, Robbie befriended Aubrey Beardsley through Aymer Vallance, a family friend. Robbie was dazzled by the ‘strange and fascinating originality’ of Beardsley and delighted in the subversive elements in his artistic designs. He later celebrated Beardsley’s decadent artistic style by comparing how he shocked the English public to how Juvenal’s satirised Roman society. Aubrey, in return, delighted in Robbie’s company, and over the next couple of years he frequently invited Robbie to lunch with him at very short notices when he needed artistic and personal advice.

Meanwhile, Mrs Ellen Beardsley, Aubrey’s mother, also took a great liking to Robbie as a reliable anchor in her son’s turbulent life. This was to become a lasting friendship. Though Robbie was twenty-three years her junior, his mature temperament and naturally caring disposition made him a trusted personal friend to her. Ellen often confided with Robbie the difficulties she had with her son’s turbulent mood and unstable health in great details. Upon occasions, she even relied on Robbie for advice on parenting: notably, in September 1893 Ellen entreated Robbie to ‘bring Aubrey to his senses’ and ‘shame him into proper behaviour’. In return, Robbie was to assist Ellen and care for Aubrey till the end of the latter’s life.

In that same year, Robbie befriended Edmund Gosse, who was twenty years his senior and ‘a great arbiter at the Savile as well as within literary London’. Gosse found Robbie very charming, and Robbie soon became a favourite with every member of the Gosse family. Through Gosse, Robbie made connections with many artists at different stages of their career, amongst whom counted Joseph and Elizabeth Pennell, R.A.M. Stevenson, Henry Harland, and D.S. MacColl, to name a few. Moreover, Gosse was to become some sort of life-long father figure to Robbie. In particular, during Oscar’s trial and imprisonment, Gosse was to be one of the few reliable shoulders Robbie could cry on, which for him was possibly a lifeline out of despair.

These friends of Robbie’s did not always mingle well with the Wilde circle. Chiefly amongst which was the animosity between Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde. Despite Wilde’s claim that he ‘invented’ Aubrey Beardsley, it was Ross who introduced Beardsley to Wilde and persuaded the latter to commission the famous illustrations for Salomé from Beardsley. However, despite their shared aestheticism and mutual artistic appreciation, they did not get along. According to Harris, the disagreement was chiefly artistic: in conversations with Beardsley Oscar showed ‘a touch of patronage, the superiority of the senior, […] and often praised him ineptly’, whereas Beardsley spoke of Oscar as a ‘showman’, who knew way more about literature than about art. Consequently their later-immortalised collaboration on Salomé was hardly collaborative at the time: Aubrey’s caricatures got on Oscar’s nerves, whilst Oscar trivialised Aubrey’s art as ‘the naughty scribbles a precocious schoolboy makes in the margins of his copybooks’. In the end, the relationship between Oscar, Aubrey, and the publisher of Salomé became rather strained, and the illustrations were sent back for re-working multiple times, much to Aubrey’s displeasure. However, their artistic differences probably had something to do with their respective sexualities as well. Despite his aesthetic appearances Aubrey was, for all we know, not interested in Uranian culture and disapproved of Oscar’s openness about his sex life. He once complained to Trelawny Backhouse that Oscar had bragged to him about having had ‘love affairs and resultant copulations’ with five boys in one night and had 'kissed each one of them in every part of their bodies’ including the dirtiest parts, which gave him ‘nausea like an emetic’. Later, Beardsley described both Wilde and Douglas to Robbie as ‘really very dreadful people’. Such personal disgust most likely animated their professional fights.

More Adey likewise disapproved Wilde’s flaunting of his sexuality, but his disapproval was more likely out of caution than disgust. Throughout his life Adey preferred to keep his private life strictly private, and he appeared so sexually aloof that few questioned his sexuality despite his 15-year-long cohabitation with Robbie (who was a ‘known homosexual’). However, like Beardsley, he seemed to have thought of Wilde and Douglas as dangerously corrupting influences on Robbie even if he stopped short of calling them ‘dreadful’. He once confided with a Catholic priest that he hoped to save Robbie from the ‘evil’ of Wilde and Douglas —— presumably meaning promiscuity with men.

But Robbie was hardly untouched canvas. Apart from the many sexual encounters he (probably) had in school and in Europe, from what we know, Robbie did enjoy himself rather liberally in queer London before 1895. Though we could not ascertain the extent of his involvement in Oscar and Bosie’s private ‘evil’, we do know that in Oscar’s ‘Neroian’ years Robbie was often a loyal fawn at his side. The three of them also shared liaisons with beautiful youths, though of those liaisons only bare outlines remain from a scandal in 1893. In that year Robbie fell hard for a young man called Claude Dansey, and after prolonged correspondence they spent a few nights together in Robbie’s London home. Afterwards, as Max Beerbohm whispered to Reggie Turner, Bosie ‘stole’ Claude from Robbie and ‘kept’ him at the Albermarle, leaving Robbie pining sadly for ‘the desire of his soul’. We do not know exactly what happened at the Albermarle —— we only know that many years later the notorious tale-weaver Frank Harris alleged that Oscar Browning had told him that at Albermarle Claude Dansey slept with Bosie, then Oscar, then a woman (most likely a prostitute) paid by Bosie —— but regardless, Claude went back to school three days late. Consequently, the school master Biscoe Wortham interrogated Claude on his whereabouts and intercepted a few letters from Bosie, which led him to discover Claude’s relationships with both Bosie and Robbie. This revelation came as a shock to Wortham, for Robbie had been a family friend. One thing led to another, Wortham then discovered that his elder son also had a brief fling with Robbie a few years back when both were teenagers. Both Wortham and the old Dansey threatened to sue Robbie for indecencies —— for some reason they were apprehensive about bringing up either Douglas or Wilde —— but Oscar Browning managed to dissuade them from prosecution.

In the aftermath of the affair Robbie was once again banished from home, except this time he had to go further than Scotland. His relatives denounced him as the ‘disgrace of the family’, the ‘social outcast’, and the son ‘unfit for society of any kind’. Like many gay men in the eye of the storm in the 1890s, he left his career and life behind for Europe. Bosie likewise went into exile to Egypt. He stayed in a house owned by his elder brother Jack and his wife Minnie, but they hardly spent time with him, so he spent most of his time alone except for attending gatherings of the English Literary Society. As with Oscar Wilde years later, the solitude and the shadows of the scandal left Robbie rather miserable. A reply from Max Beerbohm in 1893 showed that Robbie could not help but catastrophise about his grim future as a social pariah. He briefly made two trips back to London in 1894 but was sent away to North America by his family not long afterwards. Not much is known about him afterwards till 1895.

#history#queer history#victorian#victorian england#oscar wilde#robbie ross#literature#literary history#lgbtq+ history#Cambridge#aubrey beardsley#max beerbohm

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Nocturne" from Enoch Soames (1916) by Max Beerbohm.

#Nocturne#Enoch Soames#Max Beerbohm#Poems#Poetry#The Devil#Demons#Literature#Goth#Dark Academia#Hooves#Wine#Black Wine#Moonlight

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

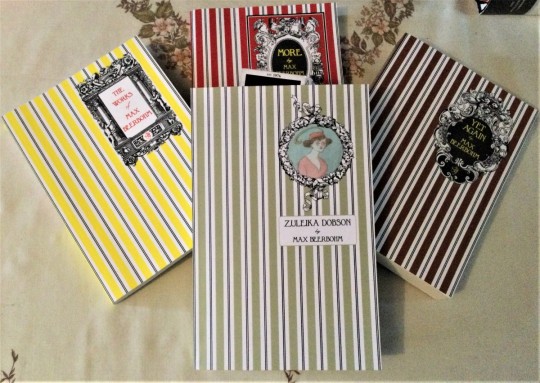

"One is taught to refrain from irony, because mankind does tend to take it literally." #zuleikadobson

In his time, Max Beerbohm was known as an essayist, parodist and caricaturist, publishing under his first name only; however, nowadays he’s best remembered for his one novel, “Zuleika Dobson“. Publisher Mike Walmer has been flying the flag for Beerbohm, and I’ve previously covered his reissues of “The Works” and “More“, in handsome paperbacks (and I still have “Yet Again” lurking!) Now Mike has…

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Storie fantastiche per uomini stanchi di Max Beerbohm: Un viaggio surreale nella mente umana. Rcensione di Alessandria today

Racconti tra ironia, fantastico e critica sociale dal genio dell'umorismo inglese

Racconti tra ironia, fantastico e critica sociale dal genio dell’umorismo inglese Recensione Storie fantastiche per uomini stanchi è una raccolta di racconti che mescola il fantastico con il surreale e l’ironico, una testimonianza del talento unico di Max Beerbohm. Questa raccolta, pubblicata da Sellerio Editore, presenta storie che sembrano uscite da un mondo parallelo, in cui la realtà è…

#Autore britannico#critica della società#critica sociale#humor britannico#ironia e satira#Letteratura del Novecento#letteratura fantastica#letteratura fantastica inglese#letteratura inglese#lettura surreale.#libri di Sellerio#Max Beerbohm#Max Beerbohm biografia#Narrativa breve#narrativa raffinata#narrativa sofisticata#narrativa surreale#narrazione ironica#paradossi sociali#parodia sociale#racconti assurdi#racconti brevi#Racconti di fantasia#racconti di Max Beerbohm#Racconti fantastici#racconti intellettuali#racconti ironici#racconti letterari#racconti umoristici#recensione Max Beerbohm

0 notes

Text

But beauty and the lust for learning have yet to be allied

Zuleika Dobson by Max Beerbohm

1 note

·

View note

Link

Sir Henry Maximilian Beerbohm was an English essayist, parodist and caricaturist under the signature Max. He first became known in the 1890s as a dandy and a hu...

Link: Max Beerbohm

0 notes

Text

James Elkington & Nathan Salsburg Interview: Poise, Levity, and Easygoingness

Photo Credit: James Elkington and Nathan Salsburg

BY JORDAN MAINZER

All Gist (Paradise of Bachelors), the third album of guitar duets from exploratory, thoughtful players James Elkington and Nathan Salsburg, sounds like what it is: two longtime friends and collaborators playing together, equal parts casual and focused. Since their 2015 album Ambsace, each has been busy, separately and together. Elkington's released three solo albums, played as part of Eleventh Dream Day, Brokeback, and Jeff Tweedy's live band, and recorded with Steve Gunn, Nap Eyes, and many more. Salsburg's dropped a bevy of albums and has played on records by Bonnie "Prince" Billy, Shirley Collins, and others. Meanwhile, the two have come together on four records by Salsburg's partner Joan Shelley, and Elkington produced Salsburg's Psalms, his 2021 album of arrangements of Hebrew psalms. Their duo records, however, are born of the most natural collaboration, each bringing to the table melodies they think--perhaps know--the other will respond to, combining them, and being open to feedback or changing gears entirely.

All Gist, specifically, carries the distinct quality of the Chicago winter during which it was recorded: You can picture Elkington and Salsburg sitting around the kitchen table, each culling from their vast repertoires and tendencies, creating something to warm their bodies and hearts and perk their heads and ears, unaware of any blusters outside. The songs are reflective of their shared artistic interests and inspirations, and they're rounded out by the presence of musical contemporaries with whom each has fostered relationships over the years. Opener "Death Wishes to Kill", which takes its title from T.F. Powys' Unclay, sports lilting guitar melodies that offer an affable sway, along with Wanees Zarour's violin solo. The minimal "Explanation Point" bounces along a groove that sounds bigger than it is, almost gestalt, as Jean Cook's strings and Anna Jacobson's brass shimmer. Moments of percussion come from other instruments like hand drums ("Long in the Tooth Again"), along with Wednesday Knudsen's woodwinds ("Nicest Distinction"), or as part of the sheer tactility of guitar scrapes and textures. The self-reflexive "Numb Limbs" gets its title from the physical aftereffects of playing a song that took forever to come together; you feel the spritely guitar picking and breakneck tempo in your own fingers.

Of course, All Gist has a few interpolations, namely a gentle, quiet, start-stopping version of Howard Skempton's "Well, Well, Cornelius" and a taut, concise combination of two traditional Breton dance tunes in "Rule Bretagne". Easily, the most unexpected song on the album is a version of Neneh Cherry's classic late 80s jam "Buffalo Stance". Oscillating and slowed down to an expanse, one guitarist plays Cherry's lyrical line, the other the song's instrumental melody, making something both recognizable and nostalgic as well as emblematic of the duo's adventurous nature. That combination, indeed, is the gist of Elkington and Salsburg.

Earlier this month, both guitarists answered some questions over email about All Gist, their creative process, covering songs, and their sometimes-overlapping, oft-diverging taste in art. Read their responses below, edited for clarity.

Photo Credit: Joan Shelley

Since I Left You: Why was it time again to make an album together? James Elkington: We’d been talking about it since we made the last one, but the truth is that we’ve both just been too busy. I started making solo records again after the last one, plus I got to produce one for Nathan, and we both help out with Joan Shelley’s records, so it never felt like we weren’t working together anyway. We were just working on projects in a different way. I think that Nathan and I both think there’s something about the duo’s music that is different from the other things we do, so we were keen to get back to it at some point. Fortunately for us, we got an invitation to play at a guitar festival in Chicago, and we used that as an excuse to start working on new material. I should also mention that our wives kept bugging us to do it again.

SILY: How was your collaboration on All Gist unique as compared to your other records together, and how was it similar? JE: We hadn’t played together like this for something like 7 years, so I was interested to see if we could even do it. But our writing together was as quick and easy as it ever was, and in that sense, it was really similar to how we worked before. Nathan has always worked with longer forms than me, but this time, I wanted to follow his lead a bit more in terms of writing longer pieces with less changes and more textures. We weren’t concerned this time with being able to play all of this stuff live, so we left more space for orchestration and overdubs. Nathan Salsburg: We’ve each lived through a world of experiences in the past ten years, musical and otherwise. Now that we’re each squarely into our middle age, I think the poise, levity, and easygoingness that should be attendant on this period of life show up in the music at [the] pitch they didn’t in the past.

SILY: Was there a lot of improvisation in the process of combining the different instrumental motifs you each brought to the recording session? JE: Because we don’t have a great deal of time to work together, we find things go much quicker if we come up with rough musical sketches by ourselves and then present them to the other. Nothing is ever written in stone, and the level of trust is very high. Anything Nathan suggests for one of my ideas is going to improve it. Both of us are more concerned with coming up with something that sounds cohesive and keeping the ball rolling than having any personal agenda for how this thing should be, and we always leave enough space for us to be surprised by what we end up with. I rarely have any idea what Nathan is playing, but I like how it sounds when it’s finished. We did experiment with recording something completely improvised and liked the results, but it sounded like a different record, so we didn’t use it. Maybe that’ll be the next one.

SILY: How or at what point in making each song do you determine whether it needs more musical accompaniment, from other instruments and/or players? JE: That’s a good question, and I’m not sure I have an answer, but the plan seems to be to write a piece that can stand by itself for the two guitars, record that to our satisfaction (which is nearly always the first take we can manage that has all the right parts), then start throwing other instruments at it to see what sticks. Most of that approach is me in my studio adding things and then taking them off again. There are certain pieces where, as were writing them, we can hear that a solo instrument would sound great in a certain part. Wannees Zarour’s solo in "Death Wishes To Kill" was like that. There are songs, like "All Gist Could Be Yours", where for a repeating chord sequence to have the effect we’re going for, its going to need a lot of support from other instruments, and we talked about that as we were writing it.

Cover art by Chris Fallon

SILY: Do you have a backlog of other people's songs you think might be fun or fulfilling to cover or reimagine as a guitar duet? What makes a song fit for a cover from your two artistic voices? JE: Well, I’m a little concerned that there’s a potential novelty aspect to our doing a lot of covers, but maybe it's okay. We certainly didn’t go out of our way to think of any for this record. Nathan suggested "Buffalo Stance" early on just because he loved the song and all the parts. I was resistant at first, just because I thought there wasn’t enough there for us to work with harmonically, but there’s so much good stuff going on with the synths and the bassline in that tune that it became more a process of picking and choosing what aspects of the song we wanted to shine a light on, at what time. Our Smiths cover from the last record is like that, too. It switches from the guitar line to the vocal depending on where we’re at or what seems to be most important, so I suppose we have a system for doing this. I think the only criteria we have for picking a song is whether one of us really really likes it and the other one can get their head around it.

SILY: "Death Wishes To Kill" takes its title from a T.F. Powys novel you both read. Do the two of you tend to recommend books, films, albums, etc. to each other a lot? Do you ever find you're about to recommend the same thing to one another? JE: I was going to write that we don’t have a huge amount of overlap, but I’m remembering going to his house when we hadn’t known each other long and being confronted with what appeared to be a wall of my own books. Its not as if we like exactly the same things, but there are some writers and records that we both like that NO-ONE else I can think of likes, so when Nathan suggests a book, I usually get to it pretty quickly. I think Nathan was reading the Powys novel, Unclay, and sent me a screen shot of one of the passages in the book with the caption "this is for you" underneath. He also sent me a link to an Australian liquor store commercial from the early 90’s because he knew it would make me laugh for a day and a half, and it did. NS: I remember we made common cause over Max Beerbohm not long after we met—Zuleika Dobson, maybe—but yeah, we each have some preoccupations that the other couldn’t give much of a shit about. Like, I can’t say mid-century British horror movies do a whole lot for me. I’m remembering when Jim spent the better part of an hour trying to explain the appeal of U.S. Maple, and I can’t say he succeeded. And Jim couldn’t care less about rural American string-bands of the late 1920s. But when we have an overlap—Unclay, say, or the totally under-appreciated Yorkshire singer-songwriter Jake Thackray, or Alan Partridge—and yes, these overlapping things do tend to all be English—it’s always stuff we’re super, super jazzed about.

SILY: Can you tell me about the cover art for All Gist? NS: The artist’s name is Chris Fallon, an old friend of mine from when I lived in New York City 20+ years ago. He’s a phenomenal painter, and I love his figures, his palette, and the scenes/settings that he dreams up. I asked him to create a portrait of us, and this is what he did. He’s never met Jim and hasn’t seen me in quite a few years, but I feel like he nailed something of Jim’s and my dynamic, equal parts earnest, bizarre, silly.

youtube

#interviews#james elkington#nathan salsburg#paradise of bachelors#all gist#james elkington & nathan salsburg#james elkington and nathan salsburg#ambsace#eleventh dream day#brokeback#jeff tweedy#steve gunn#nap eyes#bonnie “prince” billy#shirley collins#joan shelley#psalms#t.f. powys#unclay#wanees zarour#jean cook#anna jacobson#wednesday knudsen#howard skempton#neneh cherry#chris fallon#the smiths#max beerbohm#zuleika dobson#u.s. maple

0 notes

Text

Teller has an unbelievable ability to leave me speechless and overwhelmed with emotions I can't even name. I'm reffering to an essay written by him titled A Memory of the Nineteen-Nineties which was published in November 1997 in The Atlantic (you can find it here). It was dreamlike yet so real, there was something... poetic in it. And it was very much like him. That's exactly the kind of person Teller is

Oh, and if you're interested, there's a bit more info about that afternoon in the British Museum reading room in this interview article thingy

#teller#writing#the atlantic#1990s#1997#history#recent history#literature#enoch soames#max beerbohm#the british museum#british museum reading room

0 notes

Text

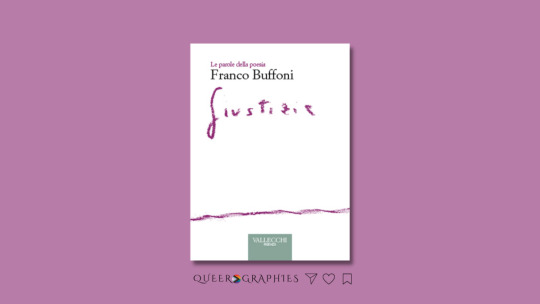

[Giustizia][Franco Buffoni]

Partendo dal rapporto tra poesia e legge, Franco Buffoni compone un magistrale percorso di rilettura della storia letteraria e dei suoi significati meno evidenti. Sul rovescio della giustizia c’è l’ipocrisia che ha costretto per secoli gli scrittori a nascondere il proprio orientamento sessuale. Da Oscar Wilde e Max Beerbohm, attraverso Giacomo Leopardi, Emily Dickinson, Giovanni Pascoli,…

View On WordPress

#2023#Elizabeth Bishop#Emily Dickinson#Franco Buffoni#Giacomo Leopardi#Giovanni Pascoli#Giustizia#Italia#LGBT#LGBTQ#Marianne Moore#Max Beerbohm#nonfiction#Oscar Wilde#Saggi#Saggistica#Vallecchi Firenze

0 notes

Text

The Spectator

Max Beerbohm Having begun a personal resurgence of interest in Max Beerbohm (exhibition, article) it would be remiss not to also allude to the special role he had with regard to Oscar Wilde. Max Beerbohm was first met Oscar in 1888 while a student at Charterhouse School, but it was not a moment likely to engender an immediate affinity. For Max it was just a brief introduction. And, as for…

View On WordPress

#oscarwilde#H. Montgomery Hyde#Lord Alfred Douglas#Max Beerbohm#oscar wilde#The Spectator#The Yellow Book#Vyvyan Holland

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is much to be said for failure. It is more interesting than success.

Max Beerbohm

0 notes

Text

Aubrey Beardsley, caricatured by Max Beerbohm:

(Possibly) Max Beerbohm, caricatured by Aubrey Beardsley:

1 note

·

View note