#Marvel Impel

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

𝟏𝟗𝟗𝟎 𝐈𝐦𝐩𝐞𝐥 - 𝐌𝐚𝐫𝐯𝐞𝐥 𝐔𝐧𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐬𝐞 - 𝐒𝐞𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝟏 - "𝐏𝐢𝐜𝐤 𝐀 𝐂𝐚𝐫𝐝"

𝐒𝐭𝐚𝐧 𝐋𝐞𝐞 "𝐌𝐫.𝐌𝐚𝐫𝐯𝐞𝐥"

#marvel#mcu#marvel trading cards#stan lee#mr marvel#marvel characters#marvel cinematic universe#90s#90s trading cards#marvel cast#marvel impel#mr. marvel#mcu comics#mcu fandom#marvel fandom#avengers

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marvel Universe Cards Series I 38: Nightcrawler

#Marvel Universe Cards#nightcrawler#kurt wagner#mutants#excalibur#trivia#trading cards#comics trading cards#90s comics trading cards#marvel comics trading cards#impel

207 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marvel Universe trading cards, series II, 1991, Disney Adventures Magazine ad.

#marvel#trading cards#1991#comics#spiderman#wolverine#magneto#daredevil#the thing#ben grimm#x-men#fantastic four#impel marketing#superheroes#supervillians#ad#ads#magazine ads#advertisement#advertising#disney adventures

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

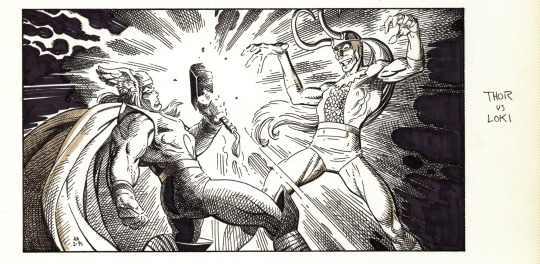

Thor Vs Loki, by Arthur Adams

#Thor Vs Loki#Thor#Loki#Arthur Adams#Trading Card Process#Trading Card#Marvel Comics#Impel#Process#Marvel#Comics#Art#Illustration#Master Class

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

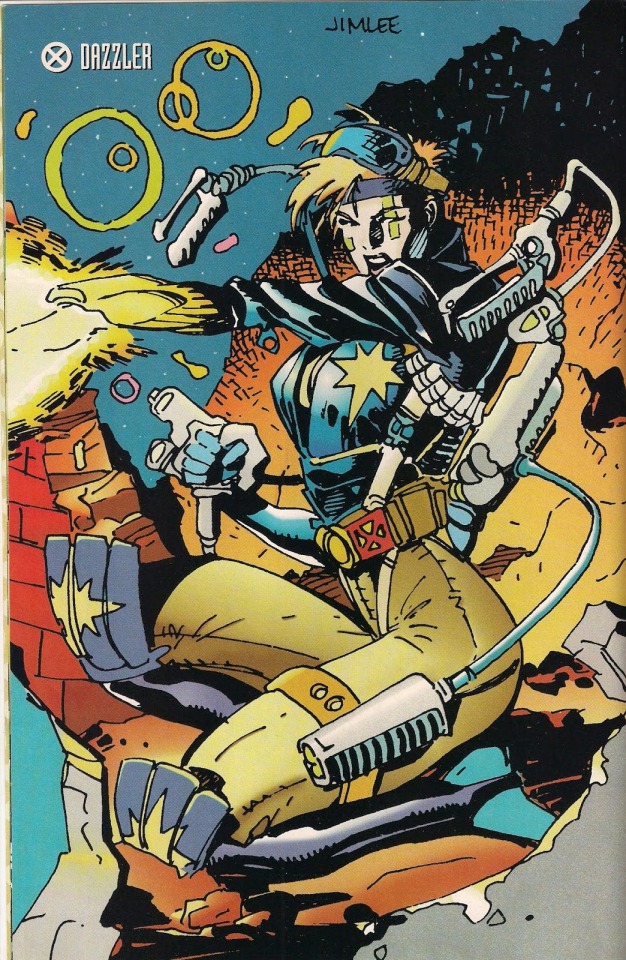

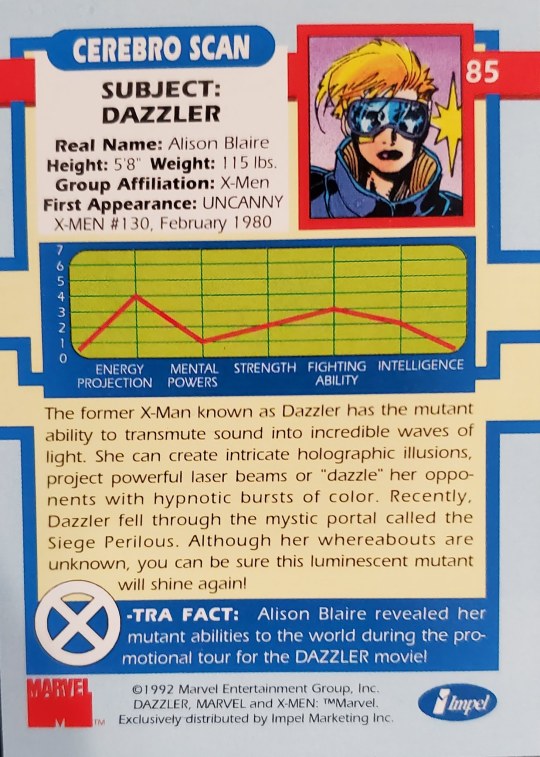

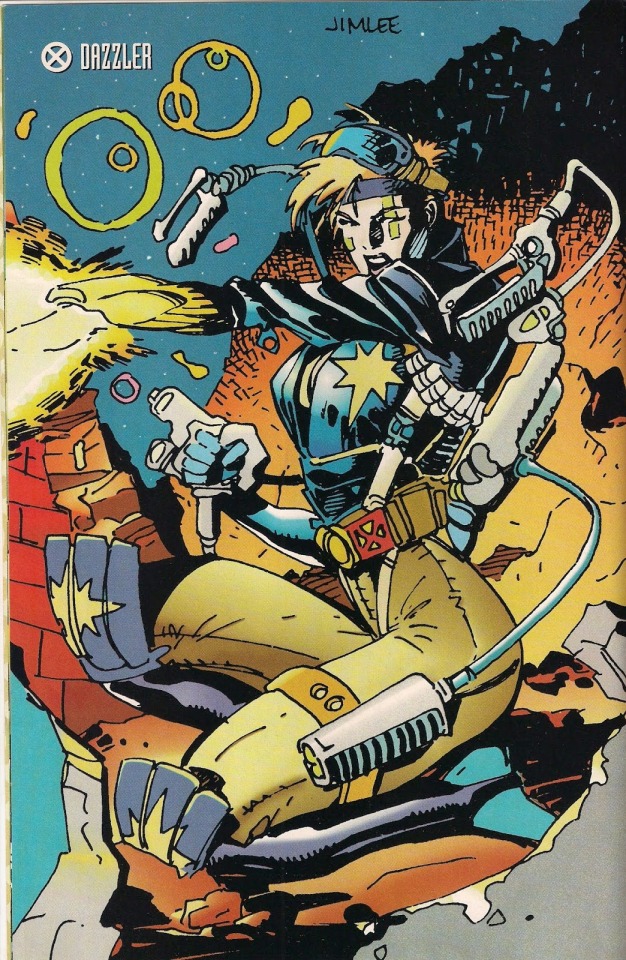

"SHE CAN CREATE INTRICATE HOLOGRAPHIC ILLUSIONS, PROJECT POWERFUL LASER BEAMS OR "DAZZLE" HER OPPONENTS..."

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on pin-up art of Alison Blaire, a.k.a., "Dazzler," in full battle mode against the forces of Mojo in the Mojoverse, from "The Marvel X-Men Collection" Vol. 1 #1 (of 3 issues). January, 1993. Marvel Comics. Artwork by Jim Lee.

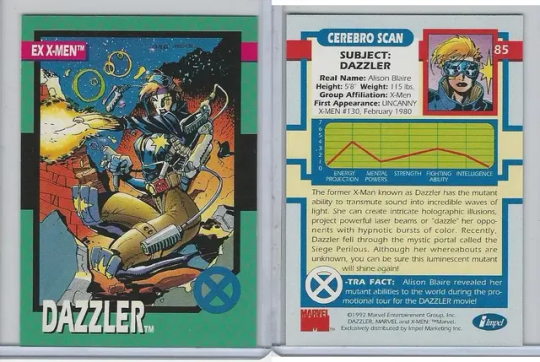

BONUS PICS: Front and back of trading card #85, Dazzler, from "X-Men" Trading Card Series 1 by Impel/Marvel, c. 1992. Artwork by Jim Lee.

Resolution from largest to smallest: 1489x2048 (2x) 1044x1600, & 1139x764.

DAZZLER OVERVIEW: "When you think of Dazzler, odds are you think of disco and rollerskates. If you're a fan of the the classic X-Men arcade game or animated "Pryde of the X-Men" pilot, then your definitive Dazzler might rock a blue bodysuit, headband and bomber jacket. Well, there's another Dazzler: Freedom Fighter Dazzler! Jim Lee's Dazzler redesign could have taken the mutant musician totally grunge, but instead she went full "Universal Soldier."

Dazzler's one of a few "Ex-X-Men" included in the set, a group devoted to characters -- like Magik and Sunspot -- who had recently left their X-teams. This card actually coincided with the debut of this rough-and-ready version of Dazzler. As her bio states, Dazzler's whereabouts were unknown prior to her return in summer 1992's "X-Men" #10. This is the version of Dazzler -- a freedom fighter commanding troops alongside Longshot in the Mojoverse -- that debuted in that story-arc. Fans wouldn't get all that much of Dazzler in the '90s, though, and once she returned in the '00s, this period of her history was mostly forgotten."

-- CBR, "Marvel Trading Cards: 15 Greats From X-Men Series I," by Brett White, c. November 2016

Sources: www.cbr.com/marvel-trading-cards-15-greats-from-x-men-series-i/#dazzler, www.yesteryearretro.com/2021/09/retro-scans-1992-marvel-uncanny-x-men.html, eBay, various, etc...

#Dazzler#Alison Blaire#X-Universe#X-MEN#Pin-ups#X-Woman#Jim Lee#Jim Lee Art#Mojoworld#Mojoverse#Impel Cards#Impel Trading Cards#Women of Marvel#Marvel Trading Cards#X-Women#90s Marvel#Marvel Cards#1990s#Sci-fI Fri#Sci-fi Art#1992#Impel#Pin-up Art#Marvel Ladies#X-Men#Pin-up Ladies#Ladies of Marvel#X-Ladies#Trading Cards#Marvel Women

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

playing with this bow (and arrow)

— chapter 1

author’s note: we’ve made it, folks. i’m writing yet another all-vibes meagre plot erotic thing. everybody act surprised!modern au (well, the 90s, since i’m so very consistent). classical musicians au set in beautiful brno. both viktor and reader are pushing 30. lots of longing and unresolved issues. reader is kind of insufferable, but oh well. you know exactly how i usually write her, don’t you? and, of course, my favorite thing to dabble with: failed marriages. also. i took it upon myself to give viktor a czech last name.

pairing: viktor x fem! reader

rating: mature. mildly nsfw-ish (some bitter masturbation), but expect explicit chapters in the future.

word count: 5k

—

Your bow plows through the strings like a thin dagger, wieldy in the hand of its swordswoman. You drag it to and fro, frenzied in a sweaty-templed convulsion. With your nyloned calves cramping from itchy tension, you almost leap swinging off the edge of your seat, pulling the cello south. The high-pitched finale of Saint-Saëns’ longest concerto finally perishes.

Your bow comes to rest on the A-string, idly fleeing away; the strain of your mouth relaxing, the flutter of eyelids ceasing. And when they spring up, unleashing your blown-out pupils, you have to flinch again—away from the scorching chandelier and its dozen artificial suns, struggling through the white patches in your shielded retinas.

You hold a breath and bask in stunned silence, counting precisely four heartbeats before the audience erupts into a standing ovation. One. The air returns to their lungs, charging for a screeching Bravo! Two. They jump out of their seats, the rustling of their clothes merging into one big swish. Three. The silence finally perishes. Each pair of palms, no matter the size, joins in on the frantic clapping. Four. Someone demands an encore. The others pick it up like an obedient hive, yelling, cheering, impelling you to grab another hold of the bow. You’d turn towards the orchestra, crooking your best fake smile, and the cycle would repeat until everyone had run out of lungfuls to request resumption.

Then there would be flowers, hearty shoulder pats, and countless impressed gasps preceding endless dithyrambs: colleagues, students and occasional admirers all producing repetitive praises—the things once catering to your ego, yet long failing to fill the void now.

‘You were marvelous, Professor.’ Of course they would say that. They could never quite catch your foibles, the way you shamefully strangled allegro moderato’s briskness, delivering but a decent-ish con-brio instead.

But you’ve always known your etiquette. Turning down praise, no matter how generic, is bad manners. So what if marvelous hardly suited your performance? So what if you were after life-changing, masterful or flawless—everything you've been chasing and failing to seize, a distant idyll that kept slipping through your calloused fingers?

So you’d shrink your shoulders and bob your head, returning the affectations, and the world would spin in a blur of your suffocating mediocrity until the afterglow of the concert had burned out, leaving you to your doleful tread down the reticent conservatory halls. Marvelous will have to suffice. You’d never call your skills something half as nice, after all.

You slid the cello onto your hunched shoulders and its weight thumped against their blades, bending you in half. One last adjustment of the strap, and you were out of the dusty building—the heavy door budging under your shove, trading its carved whimsy for the wet, pitch-black grains of tarmacadam under your oxfords. You wanted to tumble right there, to rest your heavy head against the scabrous ground, drunk on the clean smell of ozone. August had no intention of overlapping with September this year, and Brno was drenched to the marrow nearly as soon as your tear-off calendar revealed a big two in fancy cursive.

You stared at the streetlights, contemplating getting a taxi. The humidity couldn’t be any good for your Klingenthal—the mere thought of slackened plates and lax strings made you feel nauseous, and suddenly, the weight of the instrument in its shiny case had quadrupled. Taxi it is. There’s no chance you’re climbing the Golgotha with a cross that massive.

The Golgotha was what Viktor had dubbed the uphill walk to the bus stop—a spindly street, malicious with bumpy pavement—more so now that it was soaked with slick raindrops. The nickname would reach a twelve-year mark soon—an intimate inside joke that you still found hilarious. It reminded you of the better times, of the first flicker of rosin-colored eyes in the very cool halls behind you, back when neither of you was bound by the same last name or troubled with the title Professor.

You gently laid your cello on the backseat, stroking its downward slope; that, too, was Viktor’s doing—a fifth-anniversary gift, pricey as a fine vintage like that can be. You sighed and crawled into the passenger seat, tiredly announcing the destination to the driver. The man looked spent and drowsy, and you bit your cheek, cautiously staring at the instrument in its lacquered carapace. Your right hand found the ring on your left, anxiously teasing the metal warm.

“Please, drive safely.” You sank into the soft headrest. “My cello is very expensive.”

The driver gave you a lazy nod and took off, slowly struggling up the Golgotha. The world had sagged under your eyelids.

It was hard to tell when exactly things went wrong with Viktor. They say young love is bound to ruin you. There’s an inherent danger to it, a gamble of will it-won’t it. But even when it doesn’t tumble right away—there’s always something waiting to be discerned—a crack in the foundation that had been overlooked or deliberately ignored for years, a cancerous tumor surreptitiously waiting to reveal itself during the autopsy. The question is: who will be the first to reach for the scalpel in this marriage?

You preferred ostracizing Viktor from his omissions. The trick required guile—a self-subjected mind game of believing that he could do no wrong. It was easier that way. How else were you supposed to bask in self-deprecation, to find more excuses for delving into your obsession? You picked a tale old as time—the sinner and the saint, the neglector and the neglected. I am the indiscretor, you chanted. The selfish wife. The bigamist, simultaneously married to man and music. There’s no redemption for me. And I shall make my heart bleed on the fingerboard.

Dr. Talis didn’t like that approach. Matter of fact, he detested it, always trying his hardest not to roll his eyes at your weekly spirals into hypocrisy.

“Don’t start, Mrs. Knirsch.” He’d tap his pen against the notepad—a brisk staccato of condemnation. “It’s hardly ever productive.”

Productive. You winced at the word and sliced the condensate with your finger, watching a pivot of sodden city lights creep into the dripping gash. It looked harsh: a cut of black and dazzle in the foggy car window, a mini starry night. You proceeded to carve more amorphous lines into the dusky glass: they dribbled into corpulence, crawling everywhere like thick oak roots. There were five of them—precisely the number of times Jayce had uttered ‘productive’ the last time you saw him, and so you added the sixth crooked mark—a struck-through one, prison tally style.

Dr. Talis was recommended to you by a concerned upstairs neighbor. She was a darling spinster, nosy—but benevolent. When Viktor bid his indefinite farewell, her motherly shoulder was the first (and only) one to welcome your puffy face.

The next morning you were dragging up Petrov Hill, looking an utter mess—all laddered tights and tear-sodden cheeks. The shrink had taken you in before his opening hours, no questions asked. He hovered above you in the bulky stance of a weary, kind man, and you hit the wall, choking on whines.

But, as it often happens, that first impression was nothing short of mutual deception. His—of you crying all over his parquet. Yours—of him understandingly nodding along. Every session following that one was spent strictly within your confines. You quit sobbing. He quit being patient. A professional relationship built on a vulnerable mishap that had rarely occurred ever since.

And yet, you had nowhere else to go. This bespectacled, large therapist had become your only friend—a paid-for one, no less (and even so, you still confided in him quite selectively). Every Monday and Friday, you were sitting on his vintage couch, pondering anything but the issue at hand. All while he was trying to crack you again, confused by the loss of a miserable woman who had crawled to him at seven in the morning two months ago.

For all it’s worth, you quite liked the man. There was an ineffable comfort in his mild incompetence, ridiculous height, motley ties, and expensive woolly sweaters. He always looked tired, browline glasses hanging low on a big nose, dark hair glinting with too much gel. His face was sheer jawline and perpetual morning shade (another ridiculous feature, considering you only ever booked evening sessions). You wondered if he’d worn the glasses just to sharpen his big eyes: light and perceptive, they stared right through you with tender, glassy might, clashing with his virile angles.

His office resided in a moldy Austrian building—a two-story, worn-down thing flanking the cathedral, with its dusty Biedermeier windows staring right through the pretty lancets.

The place was hoarding all kinds of contentious trinkets—Tiffany lamps, fake flowers, checkered cushions, and little mockeries of classical masterpieces strewn across every wall. Mona Lisa smoking a cigarette. A frame from The Simpsons recreating The Last Supper. Venus boldly flashing the viewer instead of shyly covering her breasts with a dainty palm.

Your only grievance with the place was the window. Such a clear view of the church’s insides made your sessions feel like soft-spoken confessions, supervised by Christ himself; the distant crucifix always dwelling somewhere in your peripheral, creeping in the bleakness of gorgeous neighboring windows.

You’ve only properly visited the cathedral once: when Viktor volunteered to introduce you to Brno, utterly enraged by your scarce route of choice.

“How dare you disrespect us like that!” he murmured, shaking his head in earnest disapproval. “How come you’ve spent an entire year here, in the heart of Moravia, and yet the only walk you ever take is from the dorm to the conservatory? No, that won’t do! I have this thing,” he nudged you with his cane, earning himself a chuckle, “what’s your excuse?”

So he showed you picturesque at its finest, from Old Town Hall to St. Peter and Paul’s—an entire day of labyrinths, ossuaries, and bunkers, a palette of Czech beauties guided by the main one—lanky, well-spoken, and dressed in corduroy head-to-toe. Too bad your most vivid memory from the church was Viktor’s nape, dissected into a dozen square watts of light and drowning in not-yet-overgrown hair, its prickly ends sunbleached—the pipeline of umber to ochre. You didn’t mind, though. ‘In a room full of art, I’d still stare at you,’ or however that cheesy saying goes.

And now that swivel of maudlin was intruding on your attempts to fix the irreparable: twice a week, like clockwork, Jesus was poking his pierced-through legs into Jayce’s window, disturbing your therapy session.

“Stop ogling Jesus’ feet, Mrs. Knirsch.” Jayce snapped his fingers at you—a dull, sweat-spoiled sound. You bolted and met his eyes, scrunching your nose in sudden awareness of some mawkish whiff in the room. The culprit—a reed aroma diffuser the color of cough syrup—was glowering at you from the coffee table, emitting stifling vanilla.

You pulled at a stick, watching the oil dribble down the thin trunk. It made you smile, meek and lopsided—a shaky omen of inevitable distraction. The therapist clicked his tongue, drawing your attention back to his scorn. The clock above his head showed a quarter past six, meaning there were forty-five more minutes of confession left at your disposal.

“I don’t like his feet.” You abandoned the reeds, pushing the bottle away. Jayce caught it just in time, sucking a furious breath: right before the essence had the chance to spill all over his Turkish carpet.

“Mrs. Knirsch.”

“What? They’re pale and disturbing. I don’t know how you can just sit here, having them stare at you all day.”

“Mrs. Knirsch!”

“I told you to stop calling me that.”

“Because it reminds you of your ex-husband?”

“No, because I prefer to be addressed by my first name. And he’s still my husband. We’re merely going through a separation.”

“Oh, believe me, with that attitude, you’re definitely going to end up divorced.”

“Are you sure you’re a real therapist? Can I see your license again?”

Jayce didn’t react to that. He sighed and nosed his notepad, looking up at you from under his crooked glasses. The whimsy of bickering never lasted with him. It always dissolved when Jayce would return to the very thing therapists were meant for.

Probing.

“Please, remind me, why are you here?” Jayce coughed and propped his chin on a sturdy fist, taking his signature cross-legged interrogation stance.

You pondered his impressive knuckles, swallowing a lumpy gulp. They were thick digits of a stern man—digits that could’ve easily pulled classified information out of terrified KGB agents. You wondered if that was his occupation before he decided to become a shrink.

You pulled your skirt over your knees, straightening into a defensive sapling.

“I’m here to figure out why my husband wants to leave me—“

Jayce didn’t let you finish. His pen (that infuriating bauble!) loudly tapped the notepad again—like a makeshift incorrect buzzer. You wanted to tear the thing from his grip and throw it into Mona Lisa’s mouth, wincing with rage. But that option implied being ejected out of this quaint place.

So you decided to budge.

“I’m here because I work too much.”

The pen stopped mid-strike, hanging in the air.

“And?” The therapist trailed off, tongue running over his palate in pregnant anticipation.

“And I’m obsessed to the point of neglecting everyone around me. Myself included.”

Jayce smiled. The pen-guillotine withdrew from the blow, limply landing on the table.

“Correct.” He nodded, looking very pleased with himself. “Figuring out your Viktor business is but a bonus point. Speaking of the devil—“ Jayce licked his fingers and flicked the page, preparing a clean sheet for his observations. “How is he doing?”

You stared at the clock, drawing a nasal breath. The dial foreboded forty more minutes of this torture.

“I don’t know. He’s in London, playing Schubert.”

“Ah.” Jayce clicked his tongue. “So you do know. Is the separation not going as planned?”

You scoffed, tumbling against the couch, limbs flailing boneless in resignation. “The separation is going just fine. We haven’t spoken in two months. I just know he’s touring in Europe this time of the year.”

“But have you seen each other?”

“We work at the same conservatory. Go figure.”

“How’s that, by the way?”

“Fine. My students think I’m their local Yo-Yo Ma, or something. The usual.”

“And what do you have to say about that?”

“I think they ought to go see a doctor for an ear irrigation.”

Jayce huffed, quickly scribbling something down. “I see. Self-deprecating as ever. Well done, Mrs. Knirsch. No productivity in that capacity. But that’s all right. It’s a… process. Have you been following the curfew, at the very least?”

You chuckled at the wording, squeezing the hem of your skirt. ‘The curfew’ was a newly imposed restriction to help you overcome your compulsive rehearsing—no coming near the cello first thing in the morning (brush your teeth and have breakfast first, for god’s sake!), no playing it past eight PM, either.

Now, this part of ‘the process’ has been rather dreary. If anything, you found it damaging to Jayce’s beloved productivity—it hardly did anything except make you count the torturous seconds until you were allowed to pick up the instrument again, fingers itching like those of an addict in urgent need of a fix.

Anyhow.

“It’s okay,” you acquiesced, throwing your head back. The rippled ceiling gazed back at you, threatening to crumble into your eyes. “God. You really need to refresh this place. Am I not paying you enough?”

“As a matter of fact: yes. I don’t get paid nearly enough to catechize you like this twice a week.”

“Ha!” You pointed your shaky finger at Jayce, smiling an accusatory grin. “I see what you did there. Catechize. You have a cathedral rearing your windows. Well done, Mr. Talis. Have you considered becoming a stand-up comedian?”

“Define okay for me, Mrs. Knirsch.”

“Okay is okay. What’s there to define?”

“Everything needs definition with you. I’m going to ask you again: please, define okay.”

You sat up.

“Well, I’m following it. I have an alarm set for eight PM. I still think it’s stupid, though. It accomplishes nothing but my misery.”

The KGB interrogator melted back into a smiling man.

“Excellent!” He affirmed, almost sing-songy. His pen followed in a sequence of happy scribbles. “That’s the aim.”

“What is? My misery?” You sneered, curtly eyeing the dial. Only thirty-two minutes left. Thirty-two endless minutes until you can finally play your guts out—if you make it home in time, that is.

“No. The process. That’s how you treat an addiction.”

“Addiction? Please. Music is not heroin.”

“I beg to differ. In your case, it might just be opium.”

You sipped your bottom lip into your mouth and chewed on the soft tissue; tongue and teeth grinding over little wounds, tasting bronzey guilt. Dr. Talis pointed to his mouth, urging you to stop. You spat out your mangled lip and he watched it become plump again—all swollen skin dribbling with fresh bloody crescents. The incident was immediately reported to his little dossier.

“You’re doing that thing to your lip again.”

“I’m sorry. I can’t help. I always do that when I feel attacked.”

“Oh. Admission. That’s nice, for a change. What made you feel attacked? Was it something I did?”

“It’s not you, per se. It’s Viktor. He said something similar about opium once. It’s a shrewd metaphor.”

“Shrewd enough to make you eat yourself alive like that?”

“Don’t be a smartass. I’m contemplating cracking here.”

The minute hand shuffled, and you were reminded of the remaining half of the torture. You skimmed over the selection of Jayce’s caricatures, only to invariably linger on the voyeur-Venus, squinting for a better look. Ever since you first started coming here, she’d become a scapegoat for your telltales. Who could possibly be more vulnerable than a woman with her soul out? That’s right. A woman with her tits out. Though, you’d rather reveal the latter than the former. And the voyeur-Venus looked vastly more comfortable anyhow.

Jayce hurried to intrude, shielding the painting as his head emerged from the notes. You groaned, having been reduced to the only bare person in the room again.

“Do you think of him often?”

He regretted the fumble right away. Your eyes had regained their bludgeon glint, aiming for his throat.

“My partner of twelve years, seven of which we’ve been married, had just requested a separation. Take an educated guess.”

“I’m sorry. I’ll rephrase the question. How often do you think of him?”

“My every waking moment. And, considering that I get six hours of sleep on a good night, that adds up to a rather pathetic sum of… about eighteen to twenty hours a day. All the time, Jayce. I think of him all the time.”

“Once again, I’m so, so sorry. This separation—how long is it supposed to last? And, if it doesn’t help your cause—which, let’s hope it never comes down to that, yeah?” He shot you an apologetic smile, shakily clicking his pen. “What’s the plan in that case?”

You glowered past him, tiredly seeking Venus again, and Jayce hunched, aiding the fervent pursuit of your beacon. But when the frame sprang up from above his head, you rejected it, squeezing your eyes shut. Temples full of pulsating blood, short nails deep under bleeding cuticles (Dr. Talis had put that down, too, by the way), and in a second you were recoiling at your embarrassed “I don’t know”—all dry throat and taut calves, charging as if to snap.

Jayce blinked: once, twice. The third one must’ve been staged, just to match your three-syllable answer. He huffed, at last, wiping his glasses against his cashmere sweater.

“Don’t know…to the separation deadline or the plan in case you go through with the divorce?”

“All of it.” You whined. “Any of it. I live in willful ignorance.”

“But why? Hasn’t it occurred to you to… at least request some ephemeral due date?”

“You’re judging me. Proper therapists are not supposed to do that.”

“Well, I’m no ‘proper’ therapist. I’m just the kind you need.”

A giggle had rippled through the tears—a brief exchange of pathetic things coming in and out of your mouth. You tasted salt now, prickly, raw, and sizzling, a mess of wailing and mascara chunks, all dribbling down your chin and onto the mohair skirt, its saddle brown now speckled with wet carob. You tried to stop it, to push those shameful things back into your waterline, and yet they rolled, and rolled, and rolled, flooding the quaint office. Dr. Talis got his miserable patient back.

He offered you his handkerchief, lamenting the decision as you loudly blew your nose into the shiny white.

“I just… I felt like I had no say in it. I hurt him. He wanted a break from me. I simply went along.”

“It’s not a question of who hurt whom. You’re supposed to make those decisions together, as a couple.”

You looked up from the ruined cloth, blinking the blur away. “I thought you were on his side.”

“There is no side.” Jayce tsked, mentally calling the dry cleaning. “You’re hurting too. It’s time you embraced it.”

“Nonsense. I have no right to feel hurt.”

And then it came. The third pen-thud of the session, the weary frown, the infamous “Don’t start, Mrs. Knirsch. It’s hardly ever productive.”

The hour hand was practically licking the chunky Franklin Gothic seven on the dial. It’s truly unsettling how much time one can waste sobbing.

“Tell you what.” Jayce set his notepad on his lap, and you instantly arched, trying to sneak a glance. But, to your utmost disappointment, the thing was laid report-down, irrevocably classified.

You flicked the last parched tear and shrugged, rolling the mascara crumbs between your thumb and index. “Tell me what.”

“By next Tuesday, I want you to prepare me a list of all the reasons why you feel hurt by this separation. Could be minor, inconsequential details. Could be something more tangible. Your choice. Anything but the absence of a due date, since we’ve already established that much.”

You sniffled, peering at your hands. Black stains of makeup were drying on your calluses, enhancing the scabs of your labor. These were pockmarks of a true cellist—one-of-a-kind, immaculate, sensual. Suddenly, you were yearning for the instrument, to hell with curfew—your only desire was to have the beloved four strings cut through your fingertips, merging with the marrow.

You quit picking at your dirty skin. “That’s just weird. I’m here to stop hurting Viktor. What you’re suggesting is just gloating in poor-me’s.”

Dr. Talis gripped his nose bridge, twisting it as if to snap the cartilage. “How do you expect to un-learn your hurtful ways when you hardly even know what hurt is?”

“What if I discover something I hate about him?”

“So be it!” Jayce rose to his feet. His knees made a crunchy sound, screaming for a long walk. “Any scenario where you feel anything but pointless guilt is a win in my book.”

“Can I read it?” You nodded to his notes.

“No chance.”

“What about the handkerchief?”

“Keep it. I’m not interested in catching some weird, wailing disease.”

“Failed marriages are not contagious, you know.”

“And thank god for that!”

You lumbered out of the car, spilling a bunch of korunas. They jarred onto the slippery pavement out of your loose pockets—a downpour of fives and tens, all swiveling in between sandy joints. The driver murmured a rhotic profanity, tutting at his scattered tip, and the cab trundled away, bobbing on the pebbles.

“Sorry,” you offered into the alley, watching the plate number canter into the smog of the awry Veveří district. The curious upstairs neighbor gawked out of her window, hunching over the ledge; her frantic Einstein-blowout parted in twain, out like a greying halo. You tipped your head backward and waved, cracking your last smile of the night. She waved back and lolloped inside, heavy slippers shuffling around. You watched her disappear under the citrusy light of her lamp, swearing to never take therapist recommendations from sweet old ladies again.

You conquered three flights of stairs with breathy effort, hanging on to the straps of your cello case. Then came the habitual array of jingling keys and wan grips on the doorframe—inevitably through stinging, agape pants as the instrument gently thumped to the floor, the hum of strings an eerie vibration in between plates. It’s an unwieldy position: back—pressed against the jaundiced wallpaper, legs—tangled in a frenetic kick-away of clunky oxfords, and, finally, you were free of your confines: stockings, scarf, and skirt, all divested of into a limp heap. The heavy coat plopped over the mess, leaving but a dirty shoe to glint from beneath the huge leather sleeve—a single unshielded thing, waiting to be swept to the side.

The apartment greets you with a damp smack of bare feet against the saggy hardwood, the wallpaper daffodils becoming the cheery color of mustard when you roughly flicker the switch and idly grope your way through the half-lit rooms. You bump into the bathroom door—all awkward brushes of naked thighs—and the world cuts itself into dozens of paper-white tiles, their glint ghostly, almost asylumish. You yearn for the mirror, bending above the slippery sink. The reflection shows you a weary, barely clad woman. Her underwear slides down her legs, scrunching into a skimpy fold of—yet again—paper-white. Her tile-counterparts copy the sentiment: a bunch of flyweight-yous, all peeling the final layer of their dignity.

This used to be Viktor’s job. The thought follows you into the glass door, refusing to vaporize even when you blast hot water into your mouth—like you expect it to somehow reach your brain and melt its austerity into obtuse condensation. Sick from chlorine, your capillaries pop like a bloodshot spill. The stream persists, crawling under your prickly lashes. Viktor’s face emerges from the froth, urging you to add some salt into this whirling cocktail, and the tears oblige, goading their way out of your waterlines.

Viktor bled kindness from his fingertips. You mourned the feeling of his hands, their slothful, caring glide over the gorges of your hip dips—gently peeling the lace from those pretty dents and dragging it over your darling convexities. An exciting, albeit not-yet-erotic dance. A sweet routine, every night before shower—a blessing long forgotten.

You hold the soap under the steaming water in a vain attempt at feigning a human’s touch, its flit foreign on your back—a mushy lick that could never compete with the real thing. It pours in between your toes, thick and foamy; splits your body with milky rivulets, and lingers there in a murky trace—a study in things unfinished, a desperate search for whatever little hatred you’re allowed.

Your options assemble into the shittiest hand one could be dealt—a measly two-seven offsuit where two stands for the torturous months of his absence, and seven for the number of pathetic highs you dryly rode out around your sore fingers. Oh the miserable repercussions of sexual frustration. You contemplate upgrading it to two-eight, wet forehead tightly pressing against the glass, the squeak of clean skin a wince-igniting high-pitch.

Your hand falters. The dirty double-down stops mid-slope, coiled under your breast—a skittish tug and drop, half-hard nipple seized mid-thumb and index. You try to blow on it as Viktor-esque as you can—a stupid, vicarious stunt, but your breath gets lost in the vapor, failing to land home. You quit the thing with a strangled groan, tepidly going straight for the main ache. The itch between your thighs welcomes one awkward finger, not nearly enough to make up for the loss of him—the painful opposite of a tight fit.

Viktor. A two-syllabic, tender torture. You murmur the name like a breathy chant, the third reiteration half-assed and stumbling over the consonants. Your molars grind into powder when you claim your first head-to-toe shiver, the balls of your feet suddenly unsturdy. You think of his mouth, chapped lips upturned in a cruel denial of a kiss. The smell of him, now banished from the sheets with detergent. But you could still make it out: clean skin and the faintest whiff of piney soap. The very one slithering out of your grasp, the closest you’ve come to touching him in months. His button-down, forgotten on the shabby piano stool—the one you don’t dare move, as if trying to conjure him bent over the keys and vehemently taping out Beethoven. His penciled-in partiture, thrown all over the place—kitchen counters, desks, shelves and floors, a map of minuscule scribbles and serendipitous choices for countless coituses.

Your high slips through your fingers, escaping down the drain. You change the angle, but the chase proves fruitless: your every inch both sensitive and senseless, a stubborn ache refusing to be tamed. With your lips bitten bloodless and your hair a wet sheet of cold strands, you screw the faucet, catching your angry face in its warped reflection.

The strange, tired woman comes back, now smudged with runny mascara. You ponder her, naked and afraid, wrapped in the terror of her-your sudden revelation.

You didn’t hate Viktor for leaving. To that, he was fully entitled. For that, you could even forgive him if only you tried hard enough.

The culprit lay deeper. Uglier. Out of all his grudges, no matter how thoroughly you went over them, you always failed to find a single valid one. Hell, you failed to acknowledge there were any grudges to begin with.

All along, you didn’t hate him for the separation. You hated him for finding a reason to separate.

For being the first to reach for the scalpel.

You stumble out of the shower, staring straight ahead. Viktor’s piano glints at you from the bedroom, sad and lacquered, with no fluff of hair darkly hovering above it. You linger in the doorway, wrinkled fingers damply groping the wall, and the naked staring contest lasts a few long minutes. That is, before you grow bored. That is, before you pivot into the hallway and drag the expensive tumor of your marriage out of its shiny case.

At one in the morning, the sweet upstairs neighbor banged on your door with a noise complaint.

But you couldn’t hear her. Not over the maniacal squeaking of strings. Well, what did she expect? Dvořák’s cello pieces are known for crescendos.

—

-> chapter 2

#viktor arcane#viktor x reader#viktor fanfic#viktor x reader smut#viktor smut#viktor x f!reader#arcane#arcane modern au#playing with this bow (and arrow)#new fic yall#no beta we die#viktor x reader angst#viktor x reader fluff

183 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sabretooth, Marvel Renditions. Impel card n°15. Done in Procreate ✨ Video process on YouTube!

98 notes

·

View notes

Text

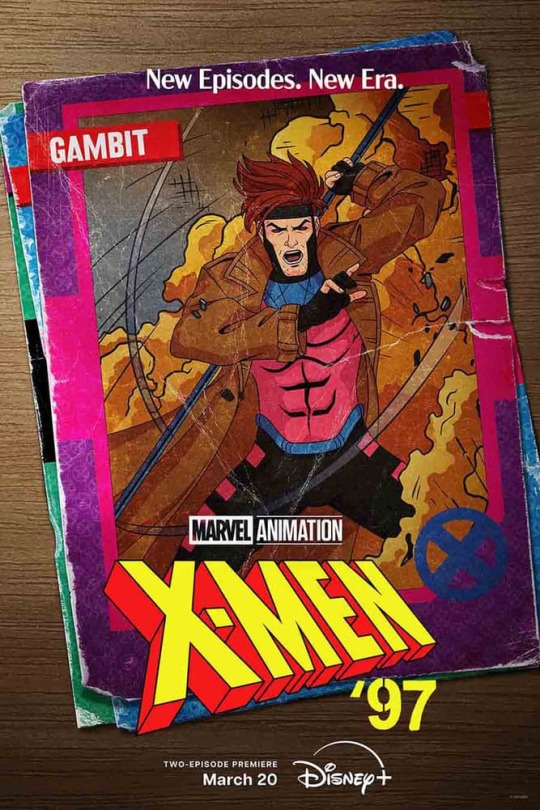

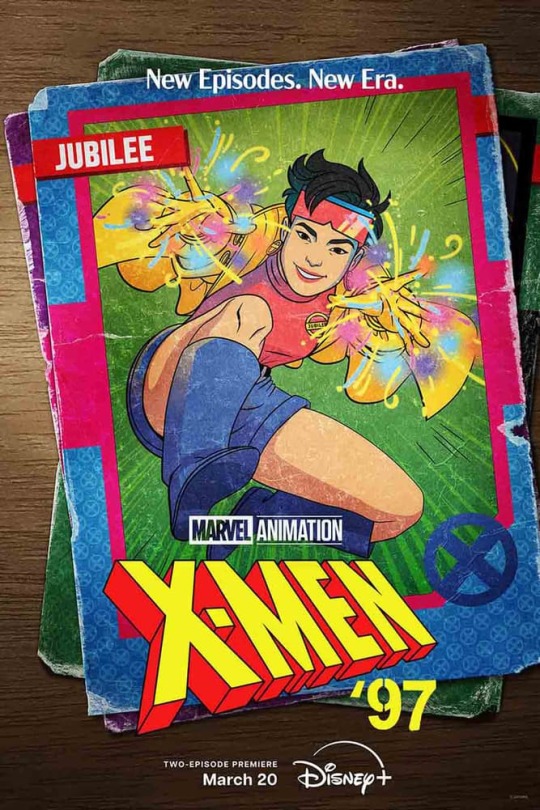

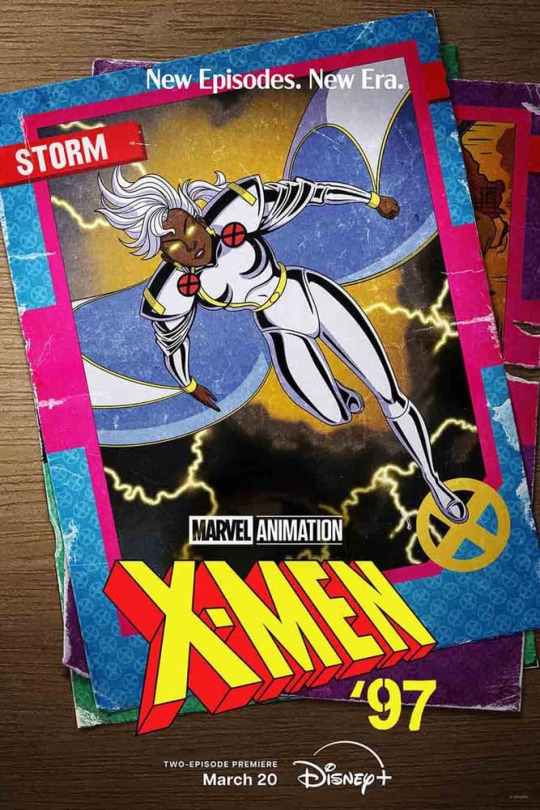

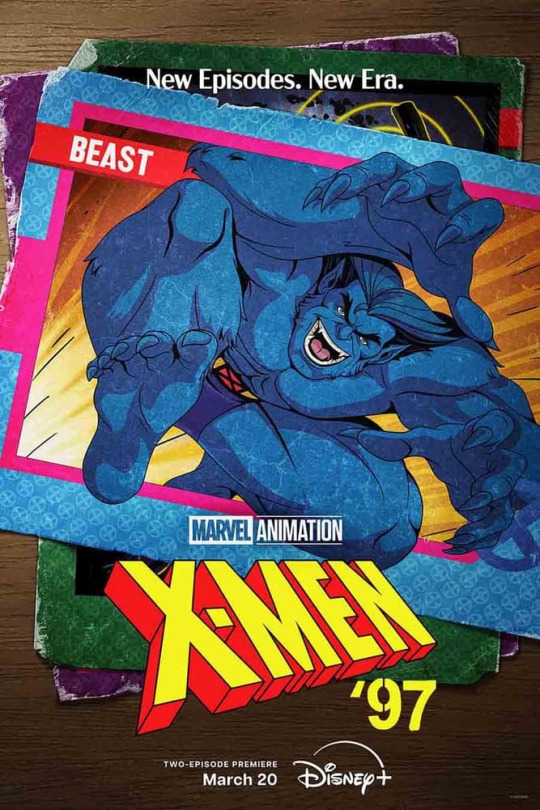

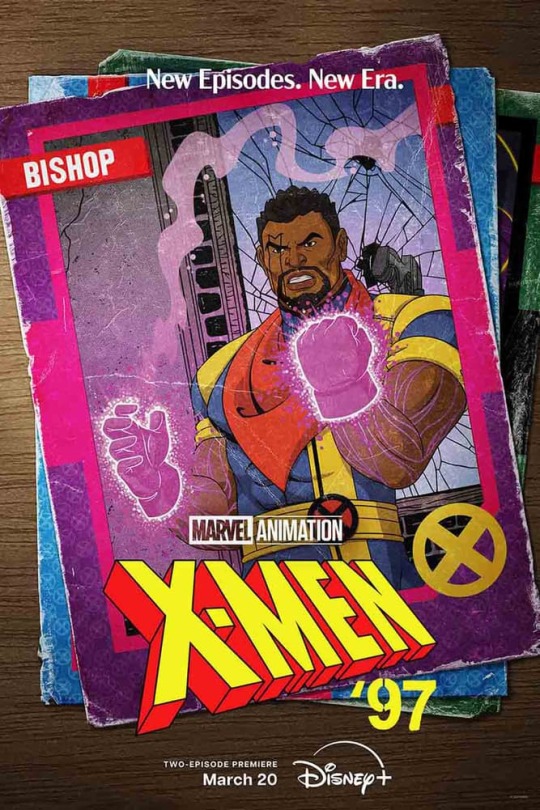

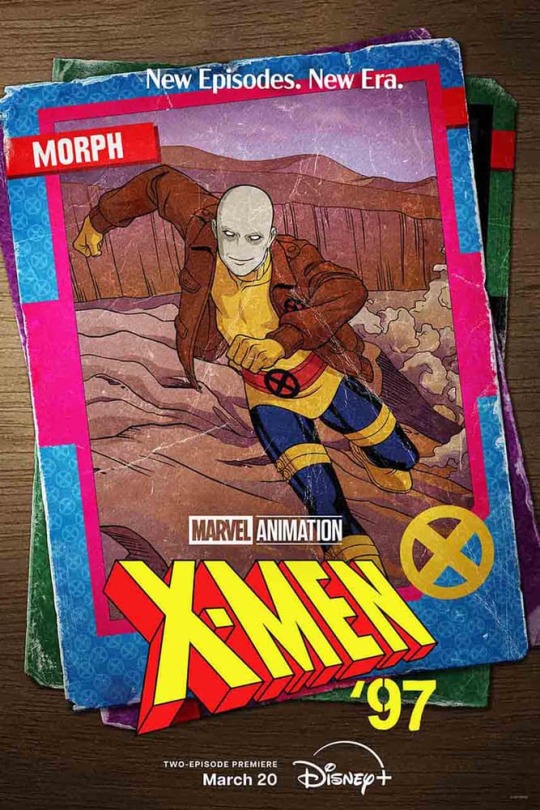

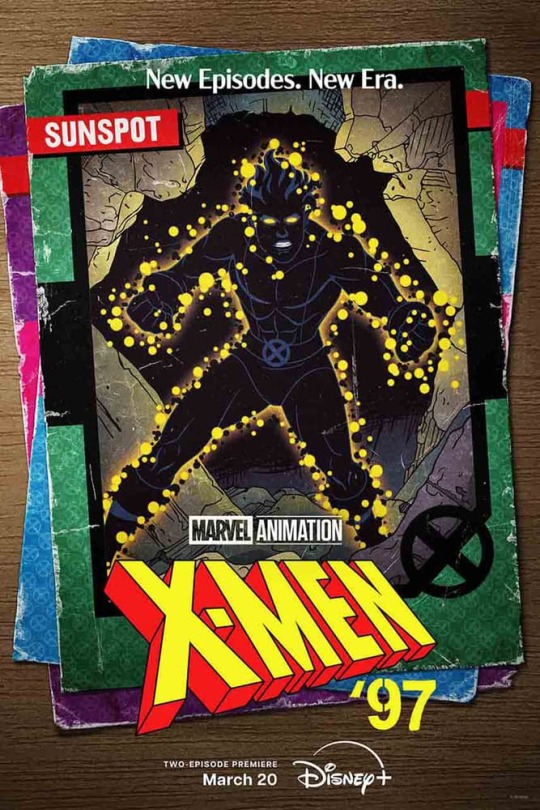

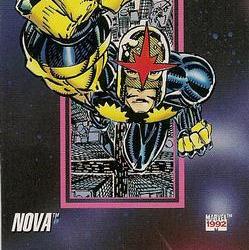

Marvel's most recent set of promo posters for X-Men '97 are a fantastic homage to Jim Lee's iconic art in Impel's The Uncanny X-Men Trading Cards series (1992)

#marvel comics#marvel animation#x-men '97#x-men: the animated series#x-men#uncanny x-men#marvel posters#marvel trading cards#marvel 1992#marvel 1997

210 notes

·

View notes

Text

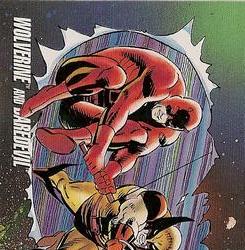

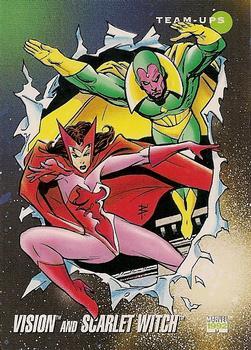

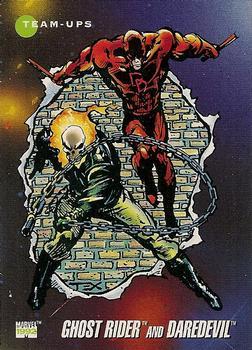

1992 Impel Marvel Universe Trading Cards (Part 3)

#spiderman#wolverine#daredevil#thor#wonder man#scarlet witch#havok#rogue#cyclops#jean grey#marvel#comic books#nova#silver sable

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Piece Chapter 1122 - Initial Thoughts

And we're back

A bit late, scanlations didn't come in my time zone yesterday and I've been unable to graft out time until now. Also My Hero's final chapter happened so I had to read that too.

But finally, back from another break in One Piece. It's 'getting off this island, this time, for real' time in Egghead, the Sunny still soars in the sky, Vegapunk's broadcast is still ongoing and there are some lingering factors still to consider.

Let's see how the chapter unravels them

Spoilers for the Chapter, Support the Official Release too

Sadly Yamato's cover story has been so boring that for a split second I got excited about seeing a Smoker cover story, but instead it's a redraw of an artwork (edit: a redraw of My Hero's mangaka's artwork, which is sweet), he looks badass though - Oda make Smoker badass more in the story! He and Tashigi need some Ws

Vegapunk's last reveal that the One Piece will decide the fate of the world has led to international worry, many not exactly thrilled with the idea that the fate of the world is likely gonna be in the hands of pirates

Pirates of course are happy, the world's smartest man just told everyone that the One Piece exists, there was more deniability when it came from a dying pirate after all

Impel Down are rambunctious, as Oda reminds us that the broadcast is piggybacking off of all Den Den Mushi whether people like it or not

Many misc Vice Admirals don't like that reveal either

Koby though, remembering his first encounter with Luffy, is forced to put himself at odds with his friend once more

Koby you know Luffy ain't like that can't you just resolve to stop his opposition?

Buggy meanwhile wins the hearts of his masses by refuting that it'll be 'his world' but rather 'our world'

His gesture at least spares him more assault from Crocodile and Mihawk - who it was really directed to

Devon and Augur are still with Caribou, asking Teach if they should kill him

Blackbeard seems willing to hear him out, which means a lot of worry awaiting Fishman Island and Wano

Vegapunk's broadcast is once again cut off after Vegapunk utters Joy Boy, with Warcury having once again damaged Emeth

As the giants call out to it's mecha kin, the Den Den Mushi inside explodes, ending the transmission once and for all

Up with the Sunny, V. Nusjuro makes chase, I guess he can gallop on air?

Zoro does prepare to confront V. Nusjuro but it's time for Emeth to do THAT JUTSU

He apologizes to Joy Boy and charges

He also apologizes to Luffy, realising that he's not the same person

What a spread though, it's like a painting seeing the Sunny flying overhead, the Gorosei's forms one side, Emeth in the middle and the longboat on the other, also with the reveal that Emeth is sorry that he couldn't make Joy Boy King

King of what though? It was implied that he led the Ancient Kingdom, perhaps he like Rocks wanted to be King of the World?

Emeth asks for Luffy's name, and he does his usual declaration

Pulling out a knotted rope, Emeth marvels at him having D. in his name

He unknots the rope, and an immense Conqueror's Haki emits from it!

Emeth thanks Luffy for letting it hear the Drums of Liberation once more, and demands that he doesn't die

The haki is so intense that not only does it revert the Gorosei to their human state, but it sends Warcury, V. Nusjuro and Ju Peter back to Marejois!!!

Mars is there waiting having been given the Manga's second successful space launch

Oh Shit! Imu even felt it, and they are rattled!

I wonder if this confirms that Imu is somehow connected to the Gorosei in some way?

Also we have a new shaded character acting as an attendant to Imu, wonder who that is?

The Sunny lands safely, much to the crew's relief

Only Saturn remains, staring down Emeth as he remembers an encounter with Joy Boy

Sadly it seems Joy Boy wasn't a giant, his silhouette is small and he must look Luffy-like

In the past Joy Boy tells Emeth that 'the time is at hand'

That Haki was Joy Boy's, which he embedded into a knot for Emeth to use, knowing that Emeth will likely outlive him

He permits Emeth to untie the knot when their life or someone's life that they care about is in danger, so they will be there to help

Joy Boy happily notes how it's like saving him with help from the past

Emeth seems to shut down once more, heartbreaking that his last memory is hoping that he won't feel lonely

Welp we pour one out for Emeth this chapter

This was an exciting chapter to come back to, and it once again puts Haki in a new perspective. Shanks has already shown that Conqueror's Haki can be utilised differently than just a shockwave or coating, but this was a lingering imbuement, something that stayed intact long after Joy Boy died, that is very fascinating.

The fact that Joy Boy's Haki could repel the Gorosei shows the ceiling Luffy and co need to get to as well, it feels like we've just breached the surface of how powerful Haki can really be, the will of the spirit, the quality of a King. And we have to mull on that, because being King does mean a lot, the end of the chapter shows Joy Boy - at least his silhouette - to be a caring person, focused on being able to help his friends, but what did Emeth want to make him king of? Was it Joy Boy's will to be king too or was it like a Whitebeard thing where he wanted to make Ace king? I'm not saying there's duplicity but the conflict between Joy Boy and the very shaken Imu could be a conflict of ruling philosophy, two extremes rather than a comfy middle ground. Food for thought at least.

With the threat of the Gorosei gone, minus Saturn we should still keep an eye on him (maybe Saturn didn't get sent back because he did technically sail there? The rest were summoned), the crew are safe to leave. But there's still other matters to deal with; the mother flame is still in Saturn's hands now, York that bitch is still alive, there's also the worldwide reaction and however Morgans wants to spin this (we never did get a reason to have a video feed from Vegapunk? Maybe his explanation of the D or the recent cutoff had the visual aids?) and there's whatever CP0 will do - I doubt Saturn will treat their and Kizaru's failures as unable to be helped, not to mention Sentomaru and Stussy's treachery.

The all out pirate war is on the horizon though, Koby looks like he's gonna step up again even if it means opposing Luffy, but as we leave Egghead the world is for sure about to be shaken more than it's ever been shook.

#one piece#one piece spoilers#op spoilers#egghead island#egghead island arc#monkey d. luffy#joy boy#roronoa zoro#straw hat pirates#dr vegapunk#gorosei#saint jay garcia saturn#saint ethanbaron v. nusjuro#saint marcus mars#saint topman warcury#buggy the clown#buggy the genius jester#cross guild#sir crocodile#dracule mihawk#blackbeard#blackbeard pirates#marshall d. teach#koby one piece#emeth one piece

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your legend impels the tides in every ocean there is by Alecto

Chapters: 1/4 Fandom: Yu-Gi-Oh! Duel Monsters (Anime & Manga) Rating: Teen And Up Audiences Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Relationships: Jounouchi Katsuya | Joey Wheeler/Kaiba Seto Characters: Kaiba Seto, Jounouchi Katsuya | Joey Wheeler Additional Tags: JouKai Week 2024, Alternate Universe - Honkai: Star Rail Fusion, Alternate Universe - Science Fiction, Crossovers & Fandom Fusions, Science Fiction, Developing Relationship, Vidyadhara (Honkai: Star Rail), First Meetings, Herta Space Station (Honkai: Star Rail), Eventual Romance

The universe housed marvels great and small. Even for those as long-lived as Seto's species, there were new discoveries to be regularly made. Seto had never met anything—anyone like Katsuya. And he was certain he wouldn't in subsequent lifetimes, either. The collected vignettes of Katsuya, the Trailblazer, and Seto, a Vidyadhara always far from home.

Written for @joukaiweek 2024 day 1 prompts: star & dragon

Read Chapter 1 on AO3

#fic: Your legend impels the tides in every ocean there is#joukaiweek2024#yugioh#puppyshipping#violetshipping#kaijou#joukai#ygo#my fanfiction#look ma! the Honkai Star Rail fusion no one asked for!#title taken from the most recent Pure Fiction update#just continuing my thing of writing random and niche fusions featuring my favorites who can never do anything wrong

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Impel Marvel National Safe Kids Campaign Trading Card Wolverine (1991) / Artist: John Romita Sr

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marvel Universe Cards Series I 63: Magneto

#Marvel Universe Cards#magneto#Magnus#erik lehnsherr#max eisenhardt#magnetic#villain#mutants#trivia#trading cards#comics trading cards#90s comics trading cards#marvel Comics trading cards#impel

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nightcrawler 1990 Impel Marvel Universe Series 1 #38 Trading Card

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Playing with fire, Transgression as truth (A)

The second article from the "Queering the Grimms" anthology I offer you was written by Kay Turner. It is part of the section "Queering the Tales" and its full title is...

Playing with fire: Trangression as truth in Grimms' Frau Trude

For many years I have been inordinately curious about an obscure Grimms’ fairy tale called “Frau Trude” (ATU 334). The tale concerns a witch and a girl and how their passionate relationship comes into being despite staunch prohibition. As a story arguing the nature of “truth,” it makes numerous direct and indirect claims concerning identity, feeling, sex and gender fluidity, kinship, and being—all within the framework of transgression and transformation, or perhaps better put, transgression as transformation

I make much of this brief tale, one infrequently given scholarly consideration. And yet, as I see it, and as the history of queer studies attests, the very task of queering the Grimms’ or any other traditional tales is to seek out the small and little-known story to discover queer possibility in the traces it offers, realizing that, as José Muñoz states, “instead of being clearly available as visible evidence, queerness has instead existed as innuendo, gossip, fleeting moments, and performances” (1996, 6). “Frau Trude” is a model for tracking the traces of queer existence in folklore.

The manifest and various relations between witches and girls in fairy tales, as between old women and young girls generally, have been undertheorized. Yet such attraction is as old as Sappho, who pined for and then penned her desire for lithe Atthis and youthful Anactoria.1 Fairy-tale scholarship rarely dips a proverbial toe into interpretive waters that might impel readers to take account of attractions, rather than repulsions, between witches and maidens. But in both well-known and obscure tales, girls find themselves drawn consciously toward, or inadvertently encountering, old women in various roles, including witch, sorceress, old woman, very old woman, grandmother, mother, mistress, wise woman, old hag, and stepmother.2 The old woman/young girl character dyad shapes a complex narrative model of female relationships, some of which beg for queer interpretation. Thus, working through “Frau Trude” leads down a winding path of transgressive wonder to arrive at bolder possibilities for understanding the diversities of desire between older and younger women in other fairy tales.3

The Grimms’ Kinder- und Hausmärchen is filled with a rich assortment of Frau Trude’s “sisters.” Though it is beyond my scope here, reading “Frau Trude” intertextually with others of its kind would no doubt bear analytical fruit concerning the structural position queer old women occupy in the fairy tale. Whether they are malevolent, like the cannibal in “Hansel and Gretel” (ATU 327A) and the kidnapper of one thousand girls in “Jorinda and Joringle” (ATU 405), or benevolent, like the old woman who hides the girl in “The Robber Bridegroom” (ATU 955) and provides for her in “The Sweet Porridge” (ATU 565), the charisma associated with these female figures emanates from their unusual propensity for agency. Housed in their marginality, abjection, and private nature, they seem to take secret delight in going it alone in those cottages deep in the woods. Frau Trude is among them: an outcast and outlaw living in her self-created house of marvels. But she finds her solitary confinement has lost its allure

Frau Trude’s tale merits reading in its entirety. I use Bettina Hutschek’s translation of “Frau Trude,” from the version in Hans-Jörg Uther’s (1996, 1:216–17) edition of the Grimms’ seventh edition of the KHM. 4

There was once a little girl who was very obstinate and willful, and who never obeyed when her elders spoke to her; and so how could she be happy? One day she said to her parents, “I have heard so much of Frau Trude, that I will go and see her. People say she has a marvelous[1]looking place and they say there are many weird things in her house, so I became very curious.” Her parents, however, forbade her going, saying, “Frau Trude is a wicked old woman, who performs godless deeds, and if you go to see her, you are no longer our child.” The girl, however, did not care about her parents’ interdiction and went to Frau Trude’s house. When she arrived there, Frau Trude asked her, “Why are you so pale?” “Ah” replied she, trembling all over her body, “I have frightened myself so with what I have just seen.” “What have you seen?” “I saw a black man on your steps.” “That was a collier.” “Then I saw a green man.” “That was a hunter.” “Then I saw a blood-red man.” “That was a butcher.” “Oh, Frau Trude, I was most terrified, I peeped through the window, and did not see you, but the devil with a fiery head.” “Oh, ho,” she said, “Then you have seen the witch in her proper dress. For you I have long waited, and longed for you, and now you shall give me light.” Thus she transformed the girl into a block of wood, and then threw it into the fire. And when it was in full glow, she sat down next to it, warmed herself on it and said, “For once it burns brightly!”

I read certain structural binaries—girl/woman; young/old; youth/age; life/death; human/witch (devil); parents/witch (lover); home/house; blood/ non-blood relations; fire/light; and light/dark—as leverage to interpret this short but provocative tale as it marks intergenerational mutual attraction and lesbian seduction, inviting understanding of strategic ways that social and sexual prohibitions may be overcome symbolically and imaginatively. Indebted to a generation of queer and LGBT academics who began broadly theorizing the heterogeneity of sex in the 1980s, I work with “Frau Trude” to invite folklore and fairy-tale scholars to touch queer theory in new ways.5 Queer scholarship generally accepts postmodern assumptions concerning the contradictory and contingent nature of signs and their systems of representation. I follow medievalist Carolyn Dinshaw, claiming for queer fairy tale analysis what she asserts for a queer history interested in unraveling the multiple meanings of sex (including sex acts, sexual desire, sexual identity, and sexual subjectivity): “Sex . . . is at least in part contingent upon systems of representation, and, as such, is fissured and contradictory. Its meaning or significance cannot definitively be pinned down without exclusivity or reductiveness, and such meanings and significances shift, moreover, with shifts in context and location” (1999, 12). Sounds like the stuff of folklore, doesn’t it? But Dinshaw’s new twist helps us rethink traditional narrative, suggesting that when queerness touches interpretation, it demonstrates “something disjunctive within unities that are presumed unproblematic, even natural. I speak of the tactile, ‘touch,’ because I feel queerness work by contiguity and displacement; like metonymy as distinct from metaphor, queerness knocks signifiers loose, ungrounding bodies, making them strange, working in this way to provoke perceptual shifts and subsequent corporeal response in those touched” (151).

There may be no better narrative site for discovering strange, ungrounded bodies and contingent sexual meanings than the fairy-tale genre, which problematizes desire, convened as wish fulfillment set in the realm of enchantment. Operating as a trope for the non-normative (but not necessarily the non-heteronormative), enchantment’s liminal state invites speculation along queer lines. Even if many tales hurtle headlong toward normative reunion, marriage, and stability, often the route navigates a topsy-turvy space filled with marvels, magic, and weird encounters that don’t simply contradict the “normal” but offer, or at least hint at, alternative possibilities for fulfilling desires that might alter individual destinies. Remarkably, in the case of “Frau Trude,” disenchantment never even occurs; rather, the witch’s marvelous realm is queered as a new home for the young girl and the old woman.

If sex, desire, and pleasure can signify heterogeneously in the fairy tale, attendant issues of kinship, family, and spousal attachment come to the fore. What narrative room does the genre supply to enlarge our consideration of relational bonds across binary differences of age, status, gender, sex, and even species? The heterogeneity of kinship is the central human problem the fairy tale presents, often queerly construed within the fundamental, if ambivalent and shifting, binary “belonging/exclusion.” Certain tales trans[1]pose the social and emotional tensions stemming from this division into architectural motifs (see, e.g., Labrie 2009). Two houses oppose each other in the landscape described by “Frau Trude.” One, symbolizing conventional belonging, is natal, heteronormative, parental, known; the other is non-kin based, homonormative, single dweller, strange. I seek in this chapter to demonstrate that the distance between them can be bridged by queer desire.

“Frau Trude” presents an especially useful example for exploring the predicament raised by these oppositions because the tale draws force from a considerably more profound one: natural/unnatural, or what Robert McRuer calls the ultimate binary of “who fits/who doesn’t” (1997, 143). The tale unmakes this divide’s inexorability by different terms of desire and agency. Queering, as a utopian project built with the brick and mortar of failure to comply, privileges the necessity of that which not only does not fit but chooses not to fit. “Frau Trude” offers two “choosey” gals—stubborn, unruly, in a word, perverse—who prove unwilling to belong to anything or anyone but themselves and each other

ENCOUNTERING “FRAU TRUDE”

My initial encounter with “Frau Trude” occurred in 1998. Invited to teach as a guest professor at the University of Winnipeg by co-editor Pauline Green[1]hill, I prepared a course called Sexualities, Folklore, and Popular Culture. For a session on folk narrative, I wanted us to study the fairy tale because the feminist scholarship in this area had by that time matured into its own fertile field of reconsiderations and new ideas. Indeed, feminist reimagin[1]ings of the Grimms’ and other tales had reached an apex of production. Among the rewriters, Irish novelist Emma Donoghue’s Kissing the Witch proffered an explicitly lesbian take. I vividly remember my first reading of her version of “Rapunzel” in which the sorceress and the long-tressed girl, after much despair, separation, and longing, come back together as lovers in the tale’s end (1997, 83–99).

I wondered how Donoghue got there. Did the Grimms’ version of the tale embed motifs, functions, or structural oppositions that made such rei[1]magining logical? Bonnie Zimmerman would answer that lesbianism as a way of knowing the world affects how we read literature, that lesbians may willfully “misread” texts, adopting “a perverse strategy of reading” (1993, 139). But what stood out most at the time and has sustained me through[1]out these Grimm years was Zimmerman’s instruction that appropriation through reading perversely requires “hints and possibilities that the author, consciously or not, has strewn in the text” (144). Thus while reading Jack Zipes’s (1992) translation of the KHM in preparation to teach, I found myself regularly exclaiming my discovery of deeply queer “hints and possibilities.” Numerous tales held such requirements, especially lesser-known ones such as “The Three Spinners,” “The Star Coins,” “The Grave Mound,” and, of course, “Frau Trude,” which struck me then, as it does now, as the queerest tale of all.

For class, I assigned Kay F. Stone’s (1993) feminist rewriting of “Frau Trude” called “The Curious Girl.” Comparing the Grimms’ original with her adaptation, what a difference a gay makes! With the encouragement and help of my young lesbian students, we interpreted “Frau Trude” as a classic “coming-out story,” an adumbration replete with the desire mixed with prohibition and fear that now distinguishes that genre. We found plenty of sex, too. Stone visited our class and I remember the evening’s brilliant explosion of ideas as we engaged with her. She conceded that, though she had “lived with” the tale for many years, returning again and again as she rewrote and told it, she had never thought of it in queer sexual terms.

Rather Stone’s interest landed in her conviction that the girl was neither destroyed nor punished for being too curious; instead, her inquisitiveness was prized. In Stone’s retelling, the girl is transformed into a log, becoming fire, a shower of sparks, a bird, a hare, and a fish. “Through these meta[1]morphoses, she experienced the sacrifice of her ego-self, which . . . gave her even greater power—freedom over herself as a fuller human being” (1993, 298–99), rewarded finally with her own story of self-knowledge and fulfillment. At the essay’s close, Stone summarizes the evolution of her relationship to “Frau Trude” with a question equally pertinent to my interpretation: “And I wonder: Is it possible to ignite oneself without being consumed?” (304). Our answers are different, but compatible.6

I, too, began to live with “Frau Trude.” Years passed and still she nagged, so to speak. My interest waxed and waned and slowly changed. Whereas earlier my interest—like the other Kay’s—centered on the girl, later I felt more and more Frau Trude’s fire drawing me to her hearth. It seemed she and I had been waiting a long time for each other. I became the curious scholar compelled to meet the witch.

THE TALE: ITS HISTORY, VARIANTS AND LANGUAGE

Numbered 43 in the KHM, “Frau Trude” (“Mistress Trude” or “Mother Trude”) conforms to ATU 334, “Household of the Witch.” It belongs to the complex of old “devourer tales” (Ranke 1990, 617–18), which also includes 333B, “The Cannibal Godfather (Godmother),” subsumed by Uther under ATU 334 in his recently updated tale type index: “A girl (woman) disregards the warning of friendly animals (parts of her body) and visits her godmother (grandmother) who is a cannibal. The girl sees many gruesome things (e.g., fence of bones, barrel full of blood, and her godmother with an animal’s head). When the girl tells her godmother what she has seen she is killed (devoured)” (2004, 1:225).

The Aarne-Thompson synopsis yields less information but more intrigue: “Visit to house of a witch (or other horrible creature). Many gruesome and marvelous happenings. Lucky escape” (Aarne 1961, 125). Demonstrating the longevity of ATU 334’s hundreds of variants, Kurt Ranke (1978, 98–100) traces its roots in Eastern Europe, with subsequent migration west from Slavic and Baltic realms—Poland, Lithuania, former Yugoslavia (Bosnia and Serbia)—to eastern Germany. He speculates that ATU 334 evolved from a myth concerning the realm of death, then changed to a macabre, demonic tale, and finally to a somewhat farcical one, happily ending with escape from the ogre. He counts about ninety variants, including thirty-six from Germany alone, where the historic-geographic record demonstrates the story’s notable change to its milder version.

In his study devoted to the form and function of gruesome children’s tales, Walter Scherf (1987) interprets twenty-seven thematically related types, including AT(U) 334, with “Frau Trude” as an example. To reflect its pro[1]gressive shift in content from horrific to moderate, he proposes the tale’s division into Eastern (334A+) and Western (334B+) European versions of different oikotypes (61–62). Reminiscent of Russian Baba Yaga tales, the descriptively more ghastly Eastern versions feature, for example, a fence strung with human intestines and doorknobs made of hands.7 Discovering her “true nature”—not woman but ogress—is a pivotal plot device in ATU 334, often intensified through a series of riddle-like questions and answers concerning what the visitor has seen at the witch’s house. In numerous variants, the girl (cousin, neighbor woman, sister, rarely a male) encounters frightening figures right before meeting the witch (Ranke 1990, 617). Once inside the house, the formulaic interrogation about these individuals be[1]gins. Initially ameliorating, the discourse recalibrates markedly in ATU 334 when the girl states she also saw a horrifying creature, witch, or devil. The ogress identified as such then usually kills her visitor but in “Frau Trude” transforms her

In older variants typically a horrifying devourer and uncompromising murderer, the witch—or death-woman (Tödin)—sometimes possesses a flexible animal head she removes at will, for the purpose of picking lice. This ogress who became Frau Trude changes dramatically as she moves west to Germany. For one thing, she gains a proper name. Likely a descrip[1]tion of her nature, it may be derived from trut or drut, a type of demon well known in the Bavarian-Austrian regions (Uther 1996, 4:88).8 As the gory, death-driven tale slowly modulates, the marvelous replaces the gruesome until finally “only a fairy tale, moreover for children, remains”; one that “is totally disarmed . . . and trivialized” (Ranke 1978, 99). If Ranke regrets that the German variant has been belittled, I offer a remedy for his woe. Once drained of the explicitly gory and murderous death drive, a different drive, equally potent, replaces it in the tale

The Grimms’ version of “Frau Trude,” first published in the 1837 KHM, substituted for “Die wunderliche Gasterei” (“The Strange Feast”), the co[1]medic variant of ATU 334, which filled slot 43 in the first two editions. This innocuous tale features a liverwurst escaping from a murderous blood sausage (Zipes 1992, 658–59). Zipes suggests the change happened because “The Strange Feast” too closely resembled number 42 in the KHM, “The Godfather,” ATU 332 (738). “Frau Trude” derives from a literary source, Meier Teddy’s Frauentaschenbuch (1823), a pocket book for women including the poem “Little Cousin and Frau Trude” (see Bolte and Polívka 1913, 377), which the Grimms retold in prose.9

According to Uther (1996, 4:88), Wilhelm Grimm conceived a new open[1]ing, creating a didactic tale to show children the punishment that results from disobedience to their parents. One wishes to have been present in the editorial chambers when the brothers decided to make the switch from sausage to witch. No doubt, sometime between publishing the volume of notes for the second edition in 1822 and the publication of the third edition of the tales in 1837, one or both read Meier Teddy’s little lyric tale and saw in it an opportunity to intensify their project’s moral agenda. Moving from meat to Mädchen (maiden), from comedy to tragedy, from lucky escape to murder seems to me a profound reflection of the Grimms’ desire to solidify their narrative portrayal of social values such as women’s silence and obedi[1]ence. Equally, it might signal their worry over changing mores, including those sexual ones slightly slipping out of closets across Europe, a result of the first prospects of the Enlightenment’s individual freedoms.10

“Frau Trude” evidences these concerns in its use of language. Though compact, the Grimms’ version nonetheless spends a wealth of linguistic currency in direct speech of an intense and ardor-laden kind: argumentative between daughter and parents, then discursive between girl and witch. Though the story begins with a standard “There once was a little girl” followed by description of her obstinate and stubborn ways, the third-person narrator soon gives over the account to the first-person protagonists. Plunged immediately into a tense, dramatic dialogue, the reader first hears the girl’s definitive, assertive tone as she demonstrates her desire to go to Frau Trude. Her parents respond by admonishing her and denouncing the Frau. A few lines later, in quick succession, girl and Frau engage with each other in interrogative, reported, expository, and declarative speech modes. Having transformed her visitor into fire, Frau Trude sits down by her bright flame and, speaking to herself/to the girl, declares her satisfaction.

The exceptionally argumentative and chatty girl and the loquacious witch by no means hold to the “silent woman” protocol Ruth Bottigheimer (1986, 116) finds in full swing in Germany by the 1830s, when “Frau Trude” was first published. Bottigheimer’s correlation of the Grimm tales’ speech patterns, gender hierarchies, and values is suggestive for “Frau Trude.” In what she calls the “century of criticism” celebrating “Wilhelm Grimm’s shift from indirect speech in the earliest versions of individual tales to direct speech in the later and final versions,” she finds, “No critic has asked, ‘Who speaks?’ or ‘Under what circumstances?’” (1987, 52). In contrast, Bottigheimer argues that Wilhelm consciously determined how much speech he would bestow any particular character (53).

Finding “good” girls and women muted or relegated to indirect speech and authority, often male, noted in direct speech, Bottigheimer also discovers that if “sprach” (spoke) too often introduces speech from a woman’s mouth, “it usually heralds a bad hat” (1987, 55). That girl and witch both speak di[1]rectly and constantly suggests Wilhelm’s editorial choices in “Frau Trude.” He loads the tale with a garrulousness that announces how “bad” he thinks both protagonists are. Again Bottigheimer is suggestive: “Transgressions can be carried out knowingly or unwittingly. Conscious transgressions by girls occur in at least four tales; in two the girls are punished and in two they escape. These two possible outcomes correspond with the good or evil nature of the prohibitor.” Bottigheimer says “Frau Trude” exemplifies a knowingly disobedient girl’s punishment, foretold in Grimm’s rhetorical insertion at the tale’s start: “so how could she fare well?” (88). We thank Wilhelm Grimm for filling the tale with direct speech, for thereby inadvertently he raises our awareness of the impassioned relationships between the characters by giving us access to their heightened emotional states (including fascination, anger, resentment, fear, yearning, and contentment) expressed in a range of speech acts.

#queering the grimm#queering the grimms#frau trude#mother trudy#grimm fairytales#queer fairytales#fairytale analysis#queer reading#kay turner#fairytale types

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

ARMED REVOLUTIONARIES IN THE FIGHT AGAINST THE MOJOVERSE.

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on X-couple (husband & wife) Dazzler and Longshot during their interdimensional stint battling Mojo and his forces in the Mojoverse, artwork by Jim Lee, from "The Marvel X-Men Collection" Vol. 1 #1 (of 3 issues). January, 1993. Marvel Comics.

"Cyclops, Rogue, Wolverine -- you have to listen to me! We're all being manipulated by a creature called Mojo! He's using us to provide entertainment to an enslaved people -- we're a narcotic for the masses!"

-- LONGSHOT to the X-Men, from "X-MEN" Vol. 2 #11 (story/script by Jim Lee)

Source: https://1ojodemelkart.blogspot.com/2014/03/the-marvel-x-men-collection-n1-children.html.

#Longshot#Dazzler#X-MEN#Jim Lee Artist#X-Women#X-Ladies#Mojoverse#Sci-fi#Marvel Comics#Marvel Universe#Jim Lee#ChildrenoftheAtom#Marvel#X-Universe#X-Men#Sci-fi Art#Sci-fi Fri#Mojoworld#Ladies of Marvel#Impel#Impel Trading Cards#Impel Cards#Marvel Cards#90s Marvel#1990s#Dazzler Alison Blaire#Alison Blaire#Marvel Women#Pin-up Art#Women of Marvel

5 notes

·

View notes