#Martin Freemen

Text

🎊Happy birthday Bilbo and Frodo!!!🎊

🎉🎉🎉

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i’m really not invested in this but there are like 2 tim/gareth fics on ao3 and someone has to fix that

#lately whenever i watch something i hop onto ao3 just to see what’s on there and you would not believe what gets fics and what doesnt#the fact internationally acclaimed dramedy series the office uk ao3 tag isn’t overflowing w slashfic…#also the tag is full of crossovers w other martin freemen media I WONDER WHY#my post

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m gonna stop posting about this movie someday, but . . . today is not that day!

The filmmakers lazily dismiss the idea of racism in the movie by making its hero, a South Carolina farmer with enough social standing to be invited to a Charlestown assembly, not an enslaver, but the problems persist. It’s not enough that Benjamin Martin is not explicitly racist himself when no Black person in the movie has any priority or purpose other than protecting White people.

*For the purposes of this meta, I’ve chosen to focus on Black characters tasked with protecting Martin’s children for the sake of (ha!) brevity. Occam and his fellow militiamen’s response to him is a whole other clown show that deserves its own meta.

If we look behind Martin when he rushes to get between Colonel Tavington’s gun and his children, we see that his Black housekeeper, Abigale, is also pulling the children behind her, using her own body as a shield in case the ball misses their father. When Abigale is taken into British custody along with the rest of Martin’s employees, all her protestations focus on the children is she is being take from. When she, for reasons never made clear, appears in the sea island community of free Black people, her sole line is “why it’s the children!” when Martin’s brood arrives to, again, be placed under Black protection.

The people the children’s aunt enslaves are not so lucky. When Tavington arrives seeking Martin’s children, the only people he finds are enslaved men who come out of their quarters to see what all the ruckus is. He asks them where Martin’s children are and shoots them when they fail to answer. This violence appears to exist in the narrative for shock value . . . except it’s not that shocking. When Tavington first appears in the story, before he shoots one of Martin’s children, one of the Black men he kidnaps points out that they “work this land as free men.” At the moment, though, they are acting as orderlies in the field hospital Martin has set up for Continental and British wounded, a task that is well outside their job description if they are indeed freemen.

Martin involves his Black employees in his rash decisions, and they are forced to share in the consequences. While the ones who work for Martin loose whatever measure of freedom they had, those on Charlotte’s plantation suffer a more permanent loss. Martin has left his children, who have already been targeted by the British once, in the care not only of their aunt but the enslaved people who live with her in the expectation that she and they will die to protect them if need be. The plantation also turns out to be a location so obvious that Tavington learns the children are there by asking a Loyalist in his own regiment. Again, Martin’s thoughtlessness not only endangers his children but visits consequences on Black people who, in this case, definitely had no choice in the matter.

Ultimately, Martin not being an enslaver is a technicality. Connection with him and his family brings nothing but peril to Black people, peril that goes largely unnoticed by Martin, his family, and the narrative generally. And yet all the Black people in the movie seem delighted to serve him. It’s Gone with the Wind with more realistic war violence.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 6.13 (after 1950)

1952 – Catalina affair: A Swedish Douglas DC-3 is shot down by a Soviet MiG-15 fighter.

1966 – The United States Supreme Court rules in Miranda v. Arizona that the police must inform suspects of their Fifth Amendment rights before questioning them (colloquially known as "Mirandizing").

1967 – U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson nominates Solicitor-General Thurgood Marshall to become the first black justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

1971 – Vietnam War: The New York Times begins publication of the Pentagon Papers.

1973 – In a game versus the Philadelphia Phillies at Veterans Stadium, Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Ron Cey and Bill Russell play together as an infield for the first time, going on to set the record of staying together for 8+1⁄2 years.

1977 – Convicted Martin Luther King Jr. assassin James Earl Ray is recaptured after escaping from prison three days before.

1977 – The Uphaar Cinema Fire took place at Green Park, Delhi, resulting in the deaths of 59 people and seriously injured 103 others.

1981 – At the Trooping the Colour ceremony in London, a teenager, Marcus Sarjeant, fires six blank shots at Queen Elizabeth II.

1982 – Fahd becomes King of Saudi Arabia upon the death of his brother, Khalid.

1982 – Battles of Tumbledown and Wireless Ridge, during the Falklands War.

1983 – Pioneer 10 becomes the first man-made object to leave the central Solar System when it passes beyond the orbit of Neptune.

1990 – First day of the June 1990 Mineriad in Romania. At least 240 strikers and students are arrested or killed in the chaos ensuing from the first post-Ceaușescu elections.

1994 – A jury in Anchorage, Alaska, blames recklessness by Exxon and Captain Joseph Hazelwood for the Exxon Valdez disaster, allowing victims of the oil spill to seek $15 billion in damages.

1996 – The Montana Freemen surrender after an 81-day standoff with FBI agents.

1996 – Garuda Indonesia flight 865 crashes during takeoff from Fukuoka Airport, killing three people and injuring 170.

1997 – A jury sentences Timothy McVeigh to death for his part in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

1999 – BMW win 1999 24 Hours of Le Mans.

2000 – President Kim Dae-jung of South Korea meets Kim Jong-il, leader of North Korea, for the beginning of the first ever inter-Korea summit, in the northern capital of Pyongyang.

2000 – Italy pardons Mehmet Ali Ağca, the Turkish gunman who tried to kill Pope John Paul II in 1981.

2002 – The United States withdraws from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.

2005 – The jury acquits pop singer Michael Jackson of his charges for allegedly sexually molesting a child in 1993.

2007 – The Al Askari Mosque is bombed for a second time.

2010 – A capsule of the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa, containing particles of the asteroid 25143 Itokawa, returns to Earth by landing in the Australian Outback.

2012 – A series of bombings across Iraq, including Baghdad, Hillah and Kirkuk, kills at least 93 people and wounds over 300 others.

2015 – A man opens fire at policemen outside the police headquarters in Dallas, Texas, while a bag containing a pipe bomb is also found. He was later shot dead by police.

2018 – Volkswagen is fined one billion euros over the emissions scandal.

2021 – A gas explosion in Zhangwan district of Shiyan city, in Hubei province of China kills at least 12 people and wounds over 138 others.

2023 – At least 100 people are killed when a wedding boat capsizes on the Niger River in Kwara State, Nigeria.

2023 – Three people are killed and another three injured in an early morning stabbing and van ramming attack in Nottingham, England.

1 note

·

View note

Text

i love shows where martin freemen gets to look disgruntled and yell at dark haired men

0 notes

Video

youtube

oh my god............ hilarious

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hmm…

#Sherlock#sherlock season 4#bbc sherlock#benedict cumberbatch#martin freemen#steven moffat#doctor who

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherlock Theories SPOILERS BELOW So it was a fun episode but didn't hold the necessary punch I was expecting in terms of mystery and Sherlock doing his Sherlock thing. I refuse to believe Mary is dead because FUCK no. 1. Sherlock said in his text to Mary something about "the final act". "Act" suggests it staged, faked, all of the above. 2. His reaction to her "death"; no real tears just kinda blank. I understand shock and such but no, and Sherlock's not stupid and would never let his ego put Mary or others at physical risk. 3. Because in her video she kept saying "if I'm died." "If I'm gone" etc, maybe Sherlock doesn't even know she's not dead, but she's hella not dead. 4. It's the only way for Mary to live a normal life with John eventually, if everyone thinks she's already dead. Okay, I think the woman John was texting (FUCK U JOHN) is a set up and was sent by someone. Other than that, the story/mystery was interesting but not totally gripping as I expected it to be, but I was so entertained by Mary doing her secret agent stuff I forgot to care.

#Sherlock#Season 4#Benedict Cumberbatch#Martin Freemen#Amanda Abington#Mark Gattis#spoilers#sorry if you haven't seen it yet#go make a drink and watch it

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Freemans

So my brother just came up with the best idea ever

He thinks (and now so do I) that there should be a movie where Morgan Freeman is a slave to Martin Freeman’s family and be like a mentor figure to Martin Freeman’s character and the entire thing should be a joke on their last name with Martin Freeman trying to free(man) Morgan Freeman.

(And we also figured out that Morgan Freeman would be God and Martin would be a reeeeeaaalllly annoying angel.)

#morgan freeman#morgan freeman is god#martin freeman#The freemen#The freemans#thank you little bro#we were watching even almighty#sorry#blame netflix

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

“...We may quickly describe the Dothraki social organization; while we only see inside one traditional Dothraki khalasar, we are repeatedly told it is typical and may take it as such (AGoT, 83-5, 195, 328). Each group of Dothraki is led by a male war-leader called a khal (whose wife is a khaleesi and whose heir is the khalakka) in a group called a khalasar. The khal‘s personal guard are ‘bloodriders’ and are sworn to the khal and are supposed to kill themselves after he dies (AGoT, 328).

The khalasar also has subordinate commanders called kos and smaller bodyguard units called khas (and at this point, you will forgive me a joke that I began to wonder if the Dothraki rode to battle on their khorses, drank out their khups and fought with khords, kows, and kharrows; it will surprise no one that Martin is not a linguist). The khal is the autocrat of this organization, he has a single, readily identifiable male heir who is his direct descendant (the khalakka) and should that heir be underage or not exist, the khalasar will disband. Strikingly, beyond the khal‘s male heir, family ties play no role at all in the organization of the khalasar or in relations between them.

This is not how horse-borne nomads organized themselves, although it bears a passing resemblance to some elements of pre-Chinggis Mongol organization. We can start by quickly ruling out the Great Plains as an inspiration and move from there. I am not an expert in the organization of any Plains Native American society (so please forgive any errors – but do tell me, so I can make corrections – I am doing my best!), but from what I have been able to read, the key institution is not the ‘chief’ but rather the extended family network (what the Sioux call, I believe, the ‘thiyóšpaye’) which were then composed by smaller households (‘thiwáhe’). The elders of those households elected their leaders; while certain families seem to have been more prominent than others, leadership wasn’t directly heritable. Direct inheritance doesn’t seem to have been as pressing an issue; territorial claims were held by the nation or tribe (the ‘oyáte’) while moveable property was held by the household or extended family network (and personal items might be buried with the deceased).

I am being a bit schematic here to avoid outrunning my limited knowledge, but a system of kinship bonds with elected leaders coordinating the efforts of multiple ethnically or linguistically related kinship groups is a fairly common system for non-state social organization (obviously that label obscures a lot of cultural and regional variation!). This would have been a plausible enough way to organize the Dothraki, with lots of deliberative councils of household leaders and chiefs that are often shrewd political leaders, managing the interests of many households, but presumably that wasn’t badass enough. It would have involved lots of complicated political dialogue and quite a lot less random murder. In any event, it is clear the Dothraki are not organized along these lines; kinship matters functionally not at all in their organization and even when Daenerys is present, we see no deliberation, merely the authority of the khal, enforced by violence.

What about the Mongols and other Eurasian steppe nomads? The Mongols and other steppe nomads were broadly organized into tribes (an ulus or ordu, the latter giving us the word ‘horde’ in reference to nomads) which were organized around a leader (for the Mongols, a khan or ‘chieftain’) and understood to be part of a given ethnic or linguistic grouping which might or might not be united politically at any given time. The position of khan was heritable, but with some significant quirks we’ll get to in a minute.

In theory, these were kinship groups, but in practice the incorporation of defeated clans and sometimes shifting allegiances blurred those lines. Ratchnevsky (op. cit., 12-3) notes a divide within groups between the non-free captives (otogus bo’ol) and the free followers of a khan (nökhör or sometimes spelled nökhöd), but these categories were flexible and not ethnically based – individuals could and did move between them as the fortunes of war and politics shifted; Temujin himself – the soon-to-be Chinggis Khan – was at one point probably one of these bo’ol. The nökhör were freemen who could enter the service of a khan voluntarily and also potentially leave as well, living in the leader’s household. This is a rather more promising model or the Dothraki, but beyond this very basic description, things begin to go awry.

First off – and you will note how this flows out of the subsistence systems we discussed last week – inheritance does matter a great deal to the Mongols. Steppe nomads generally tended to share an inheritance system which – I have never seen it given a technical name – I tend to call Steppe Partible Inheritance (though it shares some forms with Gaelic tanistry and is sometimes termed by that name). In essence (barring any special bequests), each male member of the ruling clan or house has an equally valid claim on the property and position of the deceased. You can see how this would function where the main forms of property are herds of horses and sheep, which are easily evenly divisible to satisfy such claims. Divide a herd of 100 sheep between 5 sons and you get 5 herds of 20 sheep; wait a few years and you have five herds of 100 sheep again. And for most nomads, that would be all of the property to divide.

This partibility was one of the great weaknesses, however, of steppe empires, because it promoted fragmentation, with the conquests of the dynastic founder being split between their sons, brothers and so on, fragmenting down further at each succession (each inherited chunk is often called an appanage, after the Latin usage and often they were granted prior to the khan‘s death as administrative assignments). But overall leadership of the empire cannot be divided; in theory it went to the most capable male family member, though proving this might often mean politics, war or murder (but see below on the kurultai).

Thus Attila’s three sons turned on each other and made themselves easy prey for what was left of the Roman Empire; Chinggis’ heirs did rather better, sticking together as regional rulers in a larger ‘family business’ run by the descendants of Chinggis until 1260 (Chinggis died in 1227), when they began to turn on each other. The Ottomans resolved this problem – seeing their empire as indivisible – through fratricide to avoid civil war. Note also here, how important knowing the exact parentage (or more correctly, patrilineal descent) of any potential descendant of the khan would be – we’ll come back to that.

On the surface, this might sound a bit like how Khal Drogo’s khalasar disintegrates on his death, but there are enough key wrinkles missing here that I think the match fails. The biggest difference is the importance of the larger kin group and biological inheritance. You will note above that the males of the entire royal family generally had claims on the titles and property of the deceased. And actual, patrilineal descent was important here – all of the successor states of the Mongols were ruled by rulers claiming direct descent from Chinggis Khan, down to the disestablishment of the Mughal Empire in 1857. If Khal Drogo has any extended family, they seem to be unimportant and we never meet them; they do not figure into to the collapse of his khalasar (AGoT, 633), whereas in a Mongol ulus, they’d be some of the most important people.

Indeed, Drogo’s khalasar splits up with no regard at all to the ruling family, something that Jorah notes is normal – had there been a living heir, he would have been killed (AGoT, 591). This is obviously not true of the Mongols, because Temujin, the future Chinggis Khan himself (and his brothers), was exactly such young living heir of a powerful khan and was not killed, nor was any serious attempt apparently made to kill him (Ratchnevsky, op. cit. 22) and Ratchnevsky notes that was unusual in this instance that Temujin’s mother was not supported by her brother-in-law (possibly because she refused to be remarried to him).

Moreover, succession to leadership was not automatic as it is portrayed in A Game of Thrones (either automatic in the way that Khal Ogo’s son Fogo could become Khal in the mere moments of battle between his death and his father’s, AGoT, 556 or automatic in how Drogo’s khalasar automatically disintegrates, AGoT, 591). Instead there was a crucial mediating institution, the kurultai (sometimes spelled quriltai), a council of chiefs and khans – present in both Mongol and Turkic cultural spheres – which met to decide who of the valid claimants ought to take overall leadership. Such kurultai could also meet without a succession event – Temujin was declared Chinggis Khan in the kurultai of 1206. There wasn’t typically a formal heir-designate as with the Dothraki, both because of the need for a deliberative kurultai but also because of the partible inheritance. It was rather exceptional when Chinggis designated Ögedei as his chief heir (as a way to avoid war between his other sons; Ögedei was the compromise candidate) in 1219.

We might imagine the kurultai upon the death of the Mongol version of Drogo would have been a complex affair, with political negotiations between Drogo’s brothers and uncles (should he have any) who might well use the existence of an heir as an excuse to consolidate power within the family, along with Drogo’s key lieutenants also seeking power. Of course we do not see those events because Daenerys is asleep for them, but we do hear them described and it is clear that the key factors in a Mongol kurultai – descent, family ties, collective decision-making – do not matter here. As Jorah notes, “the Dothraki only follow the strong” (AGoT 633) and “Drogo’s strength was what they bowed to, and only that” (AGoT, 591). There is no council – instead Drogo’s key lieutenants (all unrelated to him) take their chunk of followers and run off in the night. There is no council, no effort to consolidate the whole, no division of livestock or territory (because, as we’ve discussed, the Dothraki subsistence system considers neither and consequently makes no sense).

Likewise, the structures of Mongol control, either before or after Chinggis (who makes massive changes to Mongol social organization) are not here. Drogo’s horde is not the decimal-system organized army of Chinggis, but it is also not the family-kin organized, deeply status-stratified society that Chinggis creates the decimal system to sweep away. The Mongols did have a tradition of swearing blood-brothership (the Mongolian word is anda), but it only replicated strong reciprocal sibling alliances. It certainly came with no requirement to die if your blood-brother died, something made quite obvious by the fact that Chinggis ends up killing his blood-brother Jamukha after the two ended up at war with each other. And these relationships were not a form of ‘royal guard’ but intimate and rare. Instead, Chinggis intentionally assembled a personal guard, the keshig, out of promising young leaders and the relatives of his subordinates, both as a military instrument but also a system of control. Members of the keshig did not simply die after the death of their leader, but were bound to take care of the surviving family of the deceased ruler.

So apart from the observation that Steppe nomads tended to have singular leaders (but, of course, monarchy is probably the most common form of human organization in the historical period) and that they tend to fragment, almost nothing about actual patterns of Steppe leadership is preserved here. Not the basic structures of the society (the ‘nobles,’ kinship groups and larger tribal and ethnic groups which so dominated Temujin’s early life, for instance, see Ratchnevsky, op. cit. 1-88), nor its systems of inheritance and succession. Instead, most of the actual color of how Mongol society – or Steppe rulership more broadly – worked has been replaced with ‘cult of the badass’ tropes about how the Dothraki “only follow the strong,” only value strength and have essentially no other cultural norms.”

- Bret Devereaux, “That Dothraki Horde, Part III: Horse Fiddles.”

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Salver, Myer Myers, 1755, Art Institute of Chicago: American Art

Restricted gift of Warren L. Batts, Quinn E. Delaney, Jamee J. and Marshall Field, Mrs. Harold T. Martin, Brooks McCormick, Mrs. Eric Oldberg, Mrs. Frank L. Sulzberger, the Maurice Freemen fund in honor of Mrs. Eric Oldberg, the Mrs. Jacob H. Bischof Fund, Wesley M. Dixon Jr., Laura S. Matthews funds, and Mr. and Mrs. John W. Puth and Major Acquisitions Centennial endowments

Size: 3.8 × 40.6 cm (1 1/2 × 16 in.)

Medium: Silver

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/111397/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SPN Series finale.

I’m not going to say a lot about this, but I feel I need to at least say something. I stopped watching SPN awhile ago. When the show became very much a walking libertarian ideological playground, and the constant faux woke shit, I couldn’t take it anymore. I already made my peace that Destiel would NEVER be canon, and took the words of tptb, that Destiel would ALWAYS be subtext, and they are “happy” to cater to shippers that way. I said typical and moved on. The more I watched, the more it hurt to watch. I felt used and dirty. The only reason I kept watching is because I invested sooooo many years into this series. As well as my support for the actors, but then that became an issue.

As the show went on, as choices by the actors were made, as I became more cognoscente of the world I live in, and the serious decline and rise of fascism in the world, this show became public enemy number one. It left a bad taste in my mouth. And the choices of the actors I supported became problematic for me. This is NOT and attack on them, it’s just how I feel, pls respect that. I’ve seen a lot of outrage and cancel culture coming for the show after said finale, but I also see, like most times, real voices trying to be heard and taken seriously beneath the ruckus. They have something substantive to say. Many stans are choosing far more to simp for their fave then to actually take the time to truly understand the issue. In a time of homophobia, hate, ignorance, and fascism, you would think these stans would take a moment to not DEFEND the actors, but listen to the concerns. The actors will be fine, they are white and privileged, and no, it doesn’t matter if they are part of the lgbt community, or allies, no one is beyond criticisms. One thing that needs to be understood, is if you are NOT apart of an offended community, any apology to said community is NOT YOURS to forgive! PERIOD! And I see a lot of that!

That brings me to Misha. First: SPN has failed the Bechdel test, has failed to represent the LGBT+ community correctly, or with respect, it has failed poc. FAILED! I don’t expect much from actors, and I never expected much from J2, but Misha has always been a brave, and it shouldn’t be considered brave, a brave voice when it came to this show. Things became sour with me and regards to Misha, when he supported ICE! YES, that ICE. Things became sour, when he began uplifting centrist politicians whom care more about continuing money in politics, then helping those most in need, suppressed, and oppressed. Politicians far more concerned with party then policy and the people. I can forgive this ignorance do to the nature of American politics. Wealthy people do what wealthy people do, stay woefully ignorant. But despite Misha’s political failures, what broke the Camels back for me, was his statement regarding the series and it’s finale. It was the most un Misha thing I ever thought I’d see. Many stans are choosing to do PR for him, and make excuses for what he said, and trying to smooth things over, while woefully choosing to gaslight through their posts, and ignore the true concerns, and forcing forgiveness because their adorable muffin shouldn’t be hurting, and he said sorry. Oh poor poor Misha.

No! Nope! Nah! Firstly, no one should be attacking Misha, and I’m glad I’m not really seeing that. I’m happy to see so many trying to educate him, and actually reaching him to release a statement, correcting his mistake, which he did in the way the Misha I knew would, despite him becoming unrecognizable to me as of late, as well as disappointing. His previous statement was filled with bs. So much gaslighting, and revisionist history, and disregard of the issue and concerns of what fans were pointing out. I was shocked. Not Misha, he would never, but he DID. Either he was so brainwashed that he actually convinced himself this was the truth, or he was working us. I want to believe the ladder, but I don’t know who he is anymore.

I have a lot of beliefs, and theories. Things that answer so many of my concerns, and shines a light on this situation in ways that some won’t or won’t ever see. I can’t imagine the confusion for those who don’t hold my opinion, or view on this situation. Because of what I believe, things for me just hurt more. Every interview the actors do, every lie they tell, every choice they make, made it very hard for me. I had to walk completely away. Next to Merther and JohnLock, Destiel was magic. That magic had died for me. It can’t be unseen or unknown. Even in fanfiction, I can’t unsee it. They were ruined for me, and this situation is fucked up. As perfect as Misha’s response was, all I see are manipulations, and I can’t help feel that we are being humored more than listened to.

I would love nothing more than for the stans to stop simping, and also listen, the way Misha is seemingly doing. All I see is them defending, instead of listening. I don’t understand why Misha made this statement. It wasn’t his responsibility to do damage control for a hate filled ignorant show. His statements weren’t to make us feel better, it was in defense. Defense against our concerns. When ever we’ve felt this way, he was right there with us, and now he abandoned us. He now sits with egg on his face. Rightfully so. This is practically a JohnLock finale all over again, but even they had a better ending then this BS. Unfortunately Martin Freemen also pulled a Misha. The only difference is Freeman never apologized, and chose to once again gaslight. If you asked me that we would be here at the finale in this way, I’d say you were nuts. I would says, yes, the finale would look EXACTLY like what happened, but I would have never seen Misha defend it, or Jensen hating it. This blog no longer supports Misha, Desitel, cockles, mishalecki or SPN. I wish everyone well. I hope that things one day work out if they can, but I do believe this will forever be IT!

#SPN#Misha Collins#Destiel#deancas#Jensen Ackles#Cockles#mishalecki#supernatural#the cw#homophobia#representation#bechdel test#bury your gays

17 notes

·

View notes

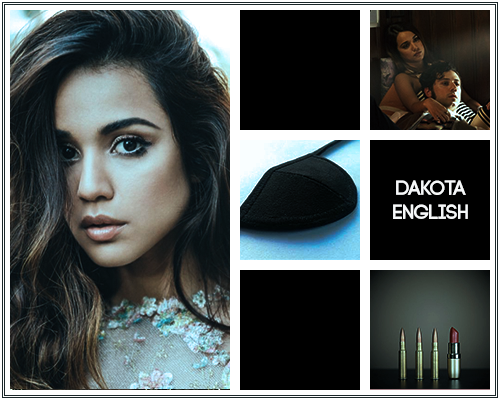

Photo

Dakota English → Summer Bishill → Rat Shifter

→ Basic Information

Age: 36

Gender: Female

Sexuality: Straight

Born or Made: Born

Birthday: October 11th

Zodiac Sign: Libra

Religion: Deism

→ Her Personality

Dakota is a beautiful, strong-willed, powerful, highly intelligent, and self-made woman, who does not allow the world to stand in the way of her ambition. She is considerably powerful and influential. Dakota swings way above the depression and anxiety line, having her work and social life in order despite having to routinely deal with incredibly dangerous missions and warlocks. She is fierce and she always stands her ground no matter the circumstances. She gives a feminist element to the pack in the most cunning and intelligent way. Although at first sight, she may seem superficial, Dakota is a keen observer; whose specialties are gossip, competition, and drama. Dakota has shown to be the most rational of her teams during stressful situations, often being mistaken for cruel and bitter, when in truth she is pragmatic, focusing on what needs to be done instead of her emotions.

→ Her Personal Facts

Occupation: Team member of BOND and GOLD

Scars: Missing her right eye

Tattoos: None

Two Likes: Morning after Mission Breakfasts and Gold jewelry

Two Dislikes: Warlocks/Witches and Jameson

Two Fears: Watching someone she loves hurt/killed while she can do nothing about it and being eaten alive by fire ants

Two Hobbies: Archery and Tai Chi

Three Positive Traits: Loyal, Daring, Pragmatic

Three Negative Traits: Standoffish, Calculating, Cut Throat

→ Her Connections

Parent Names:

Rina English (Mother): They have a perfect mother, daughter relationship. She confides in her with everything, from bad days at work to her struggles with West’s addiction. Rina was the only person who had an inkling West and Dakota were eloping when her daughter asked for something old and blue from her. Dakota can’t keep anything from her mother, and wouldn’t want it any other way.

Michael English (Father): Dakota has always been a daddy’s girl; his pride and joy. Michael believes that she deserves only the best and it’s what made him decide to take West under his wing. He knew that his head strong little girl was set on the gangly boy and decided to shape him into a good, respectable man.

Sibling Names:

None

Children Names:

None

Romantic Connections:

West Freemen (Mate): Dakota married her best friend. They fight and argue, smile and laugh, irritate and cry for each other. West loves her and she loves his weirdness and the man he has become. She wants to spend her time with him and respects his decisions. His drug habits annoy her but they’re a two person team that no one else is allowed to join. But she refuses to let that habit stop them from being together. They resolve their problems and bounce back to normal after every misstep.

Platonic Connections:

Louis Martin-Rovet (Head/Friend): Louis is her “at-home” head and stake out partner. He’s incredibly smart, and Dakota has learned a lot from him. Louis is the only one of her bosses who has treated her like she’s still capable, and allows her in the field.

Neaera Jayweed (Acquaintance): Dakota really likes Neaera and her complete and utter confidence in going against Nick. She thinks she’s probably fun and wants to get to know her more.

Jo Floyd (Confidant): Jo is the only rat who knows she’s looking into trying to find a way to get her eye back. She has been cautiously supportive and has even investigated links with her, but a part of Dakota knows she’ll tell Nick as soon as it gets serious.

Judson Clerigh (Only Lead): Judson mentioned to her in passing he could make her a new working eye, but Dakota is terrified of the consequences. She knows Louis would not be ok with her doing that and she knows the dangers of accepting magic and the hidden costs that come with it. Still it’s been the only thing she’s found that’s an option.

Hostile Connections:

Flower Hanes (Dislike): Dakota kept getting tripped up and caught in vines one day, only to find Flower and Belle laughing.

Roman Clerigh (Dislike): Roman Clerigh is like a necessary evil to her. His potions are safe for West, but she wished that West wasn’t hooked on them. And it’s easier for her to blame Roman than address the actual problem.

Minsky Edison (Scared of): There is something truly horrifying about mind control to Dakota. She’s head strong and unwavering in her beliefs, and to have someone be able to take that from her is incredibly frightening to her.

Nick Hamelin (Annoyed with): Nick has banned her from BOND missions since she lost her eye. She keeps trying to convince him to let her back in the field, but she’s pretty sure that now he’s keeping her out due to spite.

Pets:

None

→ History

Dakota was Michael and Rina English’s miracle baby. With both having high stress teams (her’s GOLD, his BOND) the likelihood of Rina getting pregnant was slim, but right before they were about to stop their aging again, she began getting sick. Both knew she would be their one and only and strived to give her the best life they could. Immediately they began reading parenting books, and strategize how to best bring their child up. When Dakota finally arrived her parents became dedicated to teaching her how to be the smartest and strongest person they could.

Her cleverness became evident when Dakota was in second grade. She’d seen one of the rat kids getting bullied. She collected as many rocks as she could carry and started her assault. The bullies quickly scattered quickly after the rat boy did. She found him later and introduced herself, and from there the greatest friendship of her life began. Dakota and West became inseparable that Summer and spent most of it getting back at the bullies in rat form. From that year West became a part of the English family, with Rina taking care of him like he was her own son. Unfortunately that didn’t mean he was immune from his own parents’ comments, and Dakota felt him slipping away from her in their teen years. She tried supporting him the best she could, keeping his secrets and helping him hide his hangovers from the older rats. When he was 16, West got caught. He told her everything that had happened with Jalissa, but it wasn’t until his parents outed his problem to the whole pack. Rina and Michael eventually heard and pulled their own daughter aside, wanting to know how involved she was in everything. When she finally broke down and told her she had to make a choice of whether she cared about West’s health or his friendship. It woke her up to what could happen to him and the feelings she had for her best friend. She began actually helping keep him safe. Making sure she was always there if he went too overboard, or couldn’t protect himself. Their friendship quickly blurred the lines into a relationship, and her parents caught them. Michael decided to train West to take a spot in BOND, while Rina offered to train her for GOLD. Dakota knew she’d be good for BOND and begged Ray to train her. He took her under his wing, after months of bothering, and by the time she hit 18 she was team mates with her father and boyfriend on BOND. She and West went to the University of Chicago together and after graduation became mates.

She and West became a reliable team for BOND, being capable of taking on most of the “couple” assignments, as well as just having a good understanding of each other. But West fell back into drugs, and especially potions, and began taking larger risks. During a mission in Prague, West needed a fix and got his supply from a random witch, who wanted something way more than a usual payment. Dakota offered her own sacrifice for him, and gave up her eye to protect him from the witch’s magic. After that mission West mostly cleaned up his act, but alternated babying her while endlessly apologizing, and sinking into a deep depression spurred on by the comments from others in the pack, especially his mother. The wrath and rage that had come from losing her eye was released onto those who felt like her lost eye was their business. She got him to eventually see her as the same woman she was before, and they came out in the end stronger.

→ The Present

It’s been about a year and a half since Dakota gave up her eye for West. She’s gone through most of the stages of grieving over it and is finally looking into fixing it. She’s looked all over for any kind of remedy. Since it is a magical wound, it’s never going to heal naturally. Which means she’s stuck looking for a magical source to fix it. She’s currently looking into witches or warlocks both locally and out of town for solutions but her sources are not readily forthcoming with that kind of information. Dakota’s also making great strides to hide it from her pack, parents, and especially West. She wants to put on a brave face for them, and it took West months before he trusted himself again. She’s accepted it the way she looks now, but still yearns to have both eyes back. Jo stumbled upon her researching at a cafe and got her to spill, and is now trying to assist in her search. Ultimately Dakota is aware Nick is going to find out, and so will the rest of the pack, but she wants to have a plan to show before that happens.

West and Dakota recently were outed as married by an accidental opening of mail. She knows the pack was thrown by it, and that Nick is pissed, but she is waiting to let someone else pick the fight. She has something bigger to fight. Dakota would really like West to stop relying on potions and try out therapy to deal with his inner emotional turmoil. His parents truly messed him up and Dakota knows how he could be even more incredible if he didn’t have their criticisms hanging in her head. She’s gotten the higher ups in the pack to approve of sessions for West and is now trying to think of how to pitch it to him.

→ Available Gif Hunts (we do not own these)

Summer Bishil (Dakota English) [1][2][3][4]

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

when you feel crickcrack in your mouth its cool crackly poppin breath mints --

https://moonoralcare.com/

Martin Freemen

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the West African Kingdom of Dahomey, before the Kingdom’s captives departed for the New World to be enslaved, they were forced “to march around the ‘Tree of Forgetfulness’ six times” so that they would remember neither their home continent nor the people they were leaving behind.

By the middle of the 18th century, the British were annually shipping tens of thousands of Africans in chains from the west coast of Africa across the Atlantic Ocean, feeding their seemingly inexhaustible desire for enslaved labor to work their sugar plantations dotted across the Caribbean. For Africans forced to leave their continent and spread across the Americas as a diaspora, these voyages have frequently been referred to as the Middle Passage, a one-way journey transforming Africans into Black slaves. The irreversibility of this journey is a bedrock of the African American origin story.

The Dahomey aristocrats forced captives to sever ties with their homeland. In the same vein, contemporary Afro-pessimist intellectuals argue that the Middle Passage means that today’s Africans and members of the African diaspora have forgotten one another. Afro-pessimism is a theory developed by Black American intellectuals like Frank Wilderson, Christina Sharpe, Saidiya Hartman and Fred Moten, which holds that the experience of racism and slavery in the Americas makes the Black American experience so unique that it cannot be compared with the suffering of other peoples.

Rendered strangers by the Middle Passage, Afro-pessimists see no shared identity that can serve as the basis for solidarity between Africans and African Americans. Historical records, however, show that occasionally, some captives, even after forcibly crossing the Atlantic, later returned to their homes in Africa as freemen.

In 1777, a British slaver, Captain Benjamin Hughes, sold African navigators — who enjoyed the status of freemen along the Gold Coast — into slavery. Years before, according to Christopher Leslie Brown’s “Moral Capital,” nine Englishmen had been taken hostage over a similar incident.

The British Company of Merchants Trading to Africa, eager to avoid the same outcome and fearing disruptions to trade, dispatched Cofee Aboan, a relative of the surviving captive Quamino Amissah, urgently to the West Indies to bring him home by way of England and sued Hughes for damages. This story demonstrates, Brown writes, that even at the height of Trans-Atlantic Slave trade, “the British were in no position to treat all black people alike.”

Despite the cruelty of slavery throughout the Atlantic world and herculean efforts on the part of European and African elites to force the enslaved to forget their past, connections between the African diaspora in the New World and those who remained in Africa persisted and grew. By the beginning of the 20th century, ties across the Atlantic gave rise to Pan-Africanism, which helped fuel the social movements that resulted in the wave of independent states in Africa and Civil Rights legislation in the United States during the 1960s.

0Pan-Africanism was an ideology that saw the suffering of Black people throughout the world, whether from colonialism, slavery or segregation, as interrelated. No less a figure than Martin Luther King Jr. understood the two struggles to be connected. In Ghana for the celebration of its independence from Britain, Dr. King said, “This event, the birth of this new nation, will give impetus to oppressed peoples all over the world. I think it will have worldwide implications and repercussions — not only for Asia and Africa, but also for America.” For decades, through the final overthrow of apartheid in South Africa in the 1990s, movements for the rights of Black Africans on both sides of the Atlantic propelled and reinforced one another.

As an ideology, Pan-Africanism’s fiercest proponents — W. E. B. Du Bois, Henry Sylvester Williams, C. L. R. James and George Padmore — argued that the struggle for national self-determination was essential to the reassertion of Black Africans’ rightful place on the world stage and their self-respect.

Yet by the 1990s, the equation of self-determination with self-respect was being challenged from three directions. The first and perhaps oldest line of critique, launched during the Cold War, argued that when nationalist movements came to power, they frequently created authoritarian states. The second, building on postcolonial authoritarianism, also highlighted the ways in which African elites were impoverishing their peoples.

Finally, a powerful strand of pessimism swept over Black American intellectuals in the 1990s, fueled both by a disappointment in the performance of postcolonial states and a growing sense that slavery and colonialism were not analogous to one another.

The Afro-pessimists insist on the particularity of enslavement in the Americas and reject the equation of the struggles of a permanent minority with anti-colonial nationalism in Africa and Asia. Today Afro-pessimism has become one of the principal ways that Black Americans engage with Africa, both intellectually and through pop culture.

Because Afro-pessimists insist on the particularity of the Black American struggle and refuse to see their struggles as connected to and reflected in the struggles of other anti-colonial movements, they are more isolated from Africa than even earlier generations. This is despite greater migration over the last few decades and vastly increased communication and transportation links between the United States and the continent.

The rise of Afro-pessimism in the 1990s has helped to freeze in place a view of the continent as “hopeless,” as the cover of The Economist announced in May 2000. In the process, Americans — particularly Black Americans, who for decades were at the vanguard of cultivating links between the U.S. and Africa — have lost a chance to build genuine solidarities with the continent.

In the process, despite our huge cultural resources, the United States has less of an economic and cultural presence on the continent today than it did at the beginning of the century, even as Africa has flourished economically since the beginning of the 21st century. Between 2000 and 2019, Sub-Saharan Africa enjoyed an average GDP growth rate of 4.35%, according to the World Bank — well above the global average over that time period.

These 20 years of respectable growth contrast sharply with what economists call the African Tragedy. During the period between 1975 and 1999, Sub-Saharan Africa’s percentage of global GNP shrank from 17.6% to 10.5%. Sub-Saharan Africa’s health, mortality and literacy rates had all followed similar trends. Capturing the world’s attention, Sub-Saharan Africa during the 1990s also had the world’s highest rates of HIV positivity: fully 9% of adults in the region were living with HIV/AIDs at the turn of the century.

Writing in the immediate aftermath of the African Tragedy, the Columbia University Professor Saidiya Hartman asserted that for Africans, “independence was a short century.” After a little less than a decade of independence, Ghana, in many ways the poster child for Pan-Africanism under the leadership of the charismatic Kwame Nkrumah, experienced the first of several military coups in 1966. Military coups swept the continent in the 1970s and ‘80s, and southern Africa and the Horn of Africa were ravaged by some of the last large-scale conflicts, outside of Afghanistan, witnessed by the twilight years of the Cold War.

Intellectually, pessimism about the political capacity of Africans to govern themselves reigned supreme in the elite universities of the United States and Britain, as well as in foreign policy think tanks and large international financial institutions. In 1981, the Harvard political scientist Robert Bates captured the zeitgeist of the moment in his classic “Markets and States in Tropical Africa” when he pointed out that agriculture — which formed the backbone of many African states’ economies — was declining in productivity due to the flagrant negligence of political elites who favored their own political constituencies over the needs of the general population.

In this context, one would be forgiven for seeing a connection between self-interested and shortsighted contemporary African elites, who traded immediate personal gains for the long-term interest of their states and people, and the African rulers during the centuries of the slave trade who made similar calculations.

The Afro-pessimists of the 1990s came of age just as South Africa won its independence from white minority rule. This victory was a symbol of the political power of Pan-Africanism, as it grew out of decades of tireless activism by South African activists in the cities and townships, as well as the strength of a global anti-apartheid coalition. At the center of this coalition were newly independent African states like Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Tanzania, Angola and Namibia, all of which faced violent incursions from the apartheid government as it resisted democracy.

Also crucially important was the mobilization of African American civil society, religious and political organizations to pressure the U.S. government to limit its support for apartheid. This support saw Reagan’s State Department, despite the presence of staunch supporters for segregation inside the administration, begin to distance itself from the apartheid government. This culminated in Nelson Mandela, the future president of South Africa and one-time political prisoner of the apartheid regime, visiting the White House to meet with President George H. W. Bush in 1990. After years of African American pressure, Bush finally declared that apartheid was a “repugnant” system.

Yet when the subject of discrimination against Americans of African descent later came up during a town hall hosted by Ted Koppel, Mandela said that, while “the entire mass democratic movement in South Africa condemns racialism wherever it may be found,” it “would not be proper for me to delve into the controversial issues which are tearing the society of this country apart. I am sure that the U.S.A. has produced competent leaders of all population groups who are able to handle their own affairs very effectively.”

The refuge of state sovereignty — a refuge unavailable to groups like African Americans destined to always be minorities — was offensive and disappointing to many Black leaders in the United States, who felt that they had put their own political capital on the line, only to receive so little in return.

Similarly, in the works of Black scholars like Hartman, Moten and Wilderson, there is a pessimism about the utility of politics, particularly politics expressed through the institutions of the state. Because while it is state power that ultimately redeems captives like Amissah from bondage or that protects its citizens from predation and capture, it is also that same power that polices the boundaries of political membership and decides who is worthy of protection. These are the same states that sent and still send people into bondage.

Amissah, despite being captured, smuggled across the Atlantic and forced to work as a slave, was never stripped of his social relations or rendered kinless. In the end, his people used their political power to call him back to their land.

The desire to return to Africa remains a powerful impulse throughout the African diaspora. Igbos, an ethnic group located in southeastern Nigeria who disappeared from enslavement in the New World, were often thought to have flown magically back to Africa. Being rescued by one’s African kin is a reoccurring theme in African American cultural consciousness. Just witness the plots of recent Hollywood blockbusters like “Black Panther” and “Coming to America 2.”

As “Black Panther” reveals, however, even cinematic reconciliation is fraught between a Black diaspora estranged from the continent and those who got to stay in the mythical kingdom of Wakanda, largely untouched by the slave trade and European colonialism. In the movie’s final moments, the King of Wakanda, T’Challa, offers Erik Killmonger, the son of a Wakandan abandoned to live in the New World, forgiveness for trying to kill him and overthrow his regime. T’Challa then tells Killmonger that he can return to Wakanda, that his exile can be ended. There is a place for him in Africa, and he does not need to wander any further in the diaspora.

In what is perhaps the film’s most poignant line, Killmonger snarls at T’Challa and says, “Just bury me in the ocean with my ancestors that jumped from the ships, ‘cause they knew death was better than bondage.” Staring out over Wakanda, Killmonger pulls a blade out of his chest and proceeds to die as T’Challa is left helpless to close the gap between them. Even if only allegorically, the filmmakers end the movie by reaffirming the intractable gap between the descendants of the dispossessed Black diaspora and the subjects of African sovereigns.

It is a skepticism about whether people of the African diaspora can find meaning in a shared narrative of the past or hope of the future that makes Hartman doubt the political potential of an identity like Africa. Instead, she writes poignantly in “Lose Your Mother:”

Unlike we come together or we who fled or we who were liberated, African people crossed the lines of raider and captive, broker and commodity, master and slave, kin and stranger. The capaciousness of these words — African people — was as dangerous as it was promising. No doubt, for the priest, the longing that resided within them concerned what we might become together or the possibility of solidarity, which would enable us to defeat the enemy again, except that they describe the enemy too.

…Africa was never one identity, but plural and contested ones.

…I came to realize that it mattered whether the “we” was called we who became together or African people or slaves, because these identities were tethered to conflicting narratives of our past, and well, these names conjured different futures.

The root of the pessimism in Hartman’s reading of African history is the knowledge that the African elites and the states that they control have for centuries been at best complicit if not at the root of their own people’s exploitations. African political projects, however well-intentioned, were doomed to impotence.

Even the children’s adaptation of The New York Times’ popular 1619 Project, “Born on the Water,” emphasizes that those of us of African descent in the United States are a new people. A recent review of the children’s book called the idea of being born on the water “beautifully reparative.” In this tale, the child making her family tree is encouraged to reflect on her people’s origins in the Kingdom of Ndongo — which by the 17th century was Catholic and in close alliance with the Portuguese, later fighting alongside them against the larger Kingdom of the Kongo and its Dutch allies.

The narrative arc centers the question of what sort of knowing state allowed its people to be captured and enslaved, before establishing — not without criticism — the idea that African Americans are the foundation upon which the United States is built. Nevertheless, the story is still one of an Africa that, even if not forgotten, willingly forsook some of its people and an imperfect republic in the United States that must be cajoled into accepting its original citizens.

It’s an irony that the United States’ relationship with Africa, outside of its ever-present security partnerships, grew weaker under its first Black President, Barack Obama. Obama, whose father came from Kenya, saw the United States lose its place as the major trading partner of most African countries, and in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Western Banks also began to leave the continent in droves.

The Obama administration’s signature initiative was Power Africa, which aimed to address glaring needs in electricity generation and access across the continent, but a lack of financing and a complicated public-private scheme led this program to have only limited impact. As the former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Tibor Nagy recently noted, “For too long when investors have knocked on the door, and Africans have opened the door, the only person standing there was the Chinese.”

One of the reasons for this increased disengagement of U.S. officials in the African continent has been the near-absence of Pan-Africanist civil society activists in policymaking about Africa. The highpoint of Pan-Africanism was the anti-apartheid struggle.

But in recent decades, African American civil society has been marked in part by a rising movement called American Descendants of Slavery, a popular nationalist movement, building for several decades, that argues that the United States and Black Americans should show special treatment to the descendants of American slavery over other people in the global Black diaspora. Similarly, the global war on terror, which intensified after the attacks on 9/11, reframed much of Africa — a continent that is home to many Muslim-majority countries — as part of a hostile and culturally alien Muslim world for many moderate Black Americans.

The African American community has also lost many of its autonomous foreign policy institutions. These institutions had historically spearheaded U.S. engagement with Africa, whether in the push for African independence, famine relief in the 1970s, the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1980s, the fight against AIDS and debt forgiveness in the 1990s or the creation of free-trade agreements in the early 2000s.

The most famous of these is TransAfrica (now the TransAfrica Forum). This organization grew out of the Black Forum on Foreign Affairs in 1976. It gave organizational and legislative capacity to the Congressional Black Caucus and the Free South Africa Movement. It had luminary members like Arthur Ashe, Mary Frances Berry, Danny Glover and Harry Belafonte. Its legislative high point was its work in passing the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986.

Yet today, groups like TransAfrica have largely faded from the public sphere. The organization today does not even maintain its own website. It is common to hear U.S. foreign policy experts relegate African affairs to a position of secondary importance, only significant as it relates to the U.S.-China competition or the spectra of terrorism. Because the links between the Black diaspora remain partially severed, Africa’s flourishing today has more to do with the rise of China and the Indian Ocean rim economies than the West.

Afro-pessimist intellectuals might argue that the growing political separation between African and Black American social movements is a welcome sign of maturity, and that distance allows for each side to articulate and look after its own interests. Yet this logic relies on an equally false belief that there is a Black American identity that can easily be demarcated from African and African diaspora identities and politics. In fact, the Middle Passage, European racism and the work of Black intellectuals throughout the world have created ties that cannot be severed.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Clovis’s grandfather Merovech

The Gaul that the Franks created, called Merovingian after Clovis’s grandfather Merovech, had its own landscape and economy. It was a country of small fortified cities and—the secret of its success—an increasing number of small communities of landholders: villages, at long last. The cities were the places of the kings, their military lieutenants, and the bishops of the Christian church. We know a lot, for example, about sixth-century Tours because of the abundant writings of Bishop Gregory there.

He was famous for his history of the Franks and other books about churchmen, but his city’s walls enclosed only about twenty-five acres of land, an area about one fortieth the size of New York’s Central Park. There would be no great or ambitious cities in Frankish realms for a very long time, but there was increasingly order, stability, a monarchy, and a lordly class made wealthy beyond its dreams by a level of taxation low enough to allow many others to feel prosperous as well. From the late fourth century to the late sixth century, military talent and good fortune had largely replaced noble birth as the basis for success and prosperity. Now birth began to matter again, as it would matter there until our own time.

Charlemagne’s time around 800

The Merovingian kings particularly favored and fostered the growth of monasticism in their domains, first invoking the heavenly patronage of Saint Martin of Tours and then in later centuries (from Charlemagne’s time around 800) under that of Saint Benedict. Monasticism on this western model combined two contradictory impulses. First, an ideology of austerity and self-sacrifice gave structure to the days and the lives of those members of the community. Second, they were places of wealth and conspicuous consumption.

All that land and all those hands were removed from the normal economy, providing an assurance of comfort and care for all those who lived on it, an assurance that no secular landlord or sharecropper could know. Land that fell into monastic hands was like an old master’s painting that comes today into the hands of a public museum: it would never be sold again, and the monastery would grow richer with time. The architecture of the monastery soon grew more and more impressive, as gift followed gift and the small community of privileged ascetics would live on the produce of rafts of farmers, be they freemen or serfs.

The right way to think about the Franks, in other words, is to imagine them as a fragment of the Roman empire, cut off and abandoned by the Mediterranean-centered government. This fragment grew, flourished, and prospered, precisely in realization of its Roman cultural DNA. (The Franks’ native way of putting it was to claim descent from the ancient Trojans, the ancestors of the Romans themselves.) When Frankishness encountered other fragments of the Roman world—for example, the Burgundian kings who flourished for a time between the Franks and the Mediterranean province but were then vanquished—different expressions of what the Romans had planted competed with one another. The Franks prevailed bulgaria tour balchik.

Eurasian landmass

In their prevalence, something fundamental to the geopolitics of the whole Eurasian landmass was finally accomplished. The outpost of civilization that had crept around the shores of the Mediterranean in the Hellenistic age was able now, decisively, to plant a replica of itself on the northern shores of the European mainland. From the middle ages onward, it has been fashionable to speak of a “transfer of empire” and a “transfer of culture” from the Mediterranean northward. The history of the period 500-2000 CE has been profoundly influenced by this coherence of culture on the northwestern fringe of Eurasia’s westernmost peninsula. Until very recently, those who grew up in that part of the world and its colonial dependencies found that introduction to the history of the world, or of western civilization, or of Europe, effectively meant indoctrination into the history of England and France, with attention to Germany during wars or reformations and to Italy during renaissances, but little more.

In the twenty-first century, such a picture of the past already seems provincial, threatened, and precious all at once. The Franks, that is to say the Romans of the Rhine, made it possible, and their success should be taken as the last western triumph of the Roman order. If we hear that Bertram of Le Mans died in 516 and from his will we learn that he left behind property of about 740,000 acres in fourteen communities, separated into more than 100 individual properties he had accumulated, we should realize that to some people any talk of decline and fall was just sour grapes on the part of the unambitious or unsuccessful.

0 notes