#Marine Corps Logistics Command

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

#youtube#militarytraining#Marine Corps Logistics Command#Brig. Gen. Maura M. Hennigan#2nd Marine Logistics Group#Change of Command#Defense News#Marine Corps Leadership#Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune#Leadership#Marine Corps Times#Military#Command#USMC#Marine Corps General#General Officer#Marine Corps Forces Command#Ceremony#Marine Corps#2nd MLG#National Defense#United States#Respect#Courage#Honor#General#Patriotism#Duty#Tradition#Service

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you want, and only if you want to, could you explain about making Logistics a big part of Ice's career path? Not only did fit so well with your Ice's characterization, it was just so neat I've made it my HC for Ice's career path.

yes!

I got REALLy deep into the defense policy weeds in this post so I’m putting a cut to save people’s dashboards

1. when i was rewriting chapters 8 &9 last winter i did literally the bare minimum of research about the current set of high-level officers. the commander of the pacific fleet at the time had previously been the director of pacific fleet logistics ordnance & supply. So that was easy to yoink. a proven chain of succession.

2. but also: it fit ice’s (or his alter ego admiral Kazansky’s) neat, orderly, effective, collected, strategic characterization. And as professional tactics go, there would be no better promotion for a high-level officer looking to take over the fleet than DFLOS. understand the fleet by the numbers, you comprehensively understand the fleet.

3. In terms of secret-keeping logistics, ice is supposed to be kind of the best. like, because of his logistical thinking, he & maverick get away with it. Or that’s how I would’ve written it if I were a little smarter. Obviously in practice a bunch of people find out so it’s not great. but the navy AS A WHOLE doesn’t find out.

4. The field of military logistics is rigorously bureaucratic, boring, soulsucking, selfdefeating, notoriously corrupt, and yet entirely necessary for the military to succeed at any level (in the very first draft of WWGATTAI i included a famous US marine corps maxim that most people have heard at some point: “amateurs talk tactics. professionals talk logistics.” but that was literally the only good thing about the original chapter 6 which got entirely rewritten a month after i published it). So logistics as a field of specialization fit in perfectly with my secondary character thesis that rising through the boring bureaucratic ranks of the Navy sucked all the humanity & will to live out of ice one day at a time.

a couple related interesting things that I’ve never talked about on this blog & might never get the chance to again:

a) ice canonically joins the navy as a fighter pilot & ends his career as a glorified bureaucrat. that sucks. obviously the struggle to rise in the ranks is a notoriously cutthroat, political, sleazy business (you do not get to the top of the United States Navy by being nice to people), but i would also not be the first person to say that—for exemplary officers—leadership is an EXPECTATION that can counterbalance someone’s natural drive to excel, if that makes sense. You get promoted because you’re good at something (flying), but you get promoted away from the thing you were good at. There is an extent to which you have to fight for a promotion—but there is also an extent to which commanders above you pick you for the job, suck you up along the pipeline. Loss of agency—a major major component of joining the military—does still apply to upper-level officers.

B) to that end, i am reminded of one quote from Todd Schmidt’s 2023 book “Silent Coup of the Guardians: US Military Elite Influence on National Security.” This is an Army training & doctrine commander speaking: “the military has a lot of two- and three-star senior leaders that were confident, charismatic commanders at the O-6 level. But that’s the end of the story. One in fifty, maybe one in a hundred, truly have what it takes to operate successfully at the strategic level and make a real difference for their service. The problem is that they all tend to think that, since they have stars on their shoulders, they’re the one.” —I’ve been writing ice as “The Chosen One,” the officer unicorn, for two reasons: one, it provides him cover for his illegal relationship (and also asks an interesting chicken-egg question: does he get away with his rlnship because he’s so good, or is he so good JUST to get away with his relationship?); and two, he’s “the chosen one” in canon, i.e. he already has four stars in canon: canonically he is not a mediocre officer. But most officers (cough cough maverick) are not cut out for high-level leadership.

C.) in Thomas E. Ricks’ book “The Generals,” Ricks argues that (at least in the Army) mediocrity in the general/flag officer ranks is unfortunately by design. In WWII, if you were a mediocre officer, you got relieved! You got fired! It’s part of why we won: merciless culling of the general officer ranks! But between WWII and Korea, officer relief began to be associated with shame & wasted resources. Mediocre officers got promoted anyways. The military elite pipeline sucks mediocrity up the chain of command. Ricks blames this issue for (at least the Army’s) shit leadership in every post-WWII war, including but most especially Iraq and Afghanistan. There’s no penalty for mediocrity. That in turn reflects on military strategy (mediocre strategists at the helm) & the outcome of every military foray (mediocre outcomes).

D) additionally. There’s a whole neverending debate in the field of civil-military relations (an extremely interesting field of study btw) about the corporatization of the military—lots of high-level talk over the years of “running the military like a business.” If you get kinda into defense policy like me (am i still antimilitary? Idk! but i CAN easily tell you i am against the navy’s littoral combat ship program! It sucks!) then you will know that the navy is struggling right now on a lot of different fronts (procurement [shipbuilding esp. is a disaster—ford-class carriers are under budget though 👍🏽], recruitment, theatre prioritization, general preparedness, readiness against major adversaries [China in particular]). Simply, the navy is pretty mediocre at the minute. I talk a big game about ice being COMPACFLT & SECNAV, but if those are true, & if he “exists” in our current timeline, or even canon timeline (COMPACFLT in 2020), then he’s complicit in a lot of why the navy is sucking ass right now. He didn’t do his job very well. LOL. So, because I love (especially my version of) ice too much to see his legacy suffer, I am stating for the record that my timeline is a different timeline where ice saves the navy from itself and fixes all its issues & solves all its problems & makes it the pride of the armed forces & the tip of the spear of American defense :) because I said so

E.) unrelated but important. It sounds obvious but it must be said. Ice dies on the job in TGM canon. To the extent that in earlier drafts of the script, not-his-sister-Sarah even points out to maverick that ice is still active duty, in the same breath as she tells him ice is sick again. (A wise move to remove that line.) ice does not resign his commission. Ice does not retire to spend time with his family at the end of his life. Ice dies as commander of the pacific fleet. He dies on the job; he dies FOR the job, bureaucratic as it is. If you were wondering why I wrote ice so dormantly suicidal, it’s because canon (i argue) has made it clear that—since the second ice signed up to be a fighter pilot during the Cold War to the second he died active duty—ice has ALWAYS been ready and willing to die for his honorable Navy career.

#so imagine what would have happened had he been publicly dishonored 😶#It’s also why i interrupted his SECNAV tenure with his cancer#to pay respects to compacflt Ice having the same thing happen to him#my Ice is built different tho. it doesn’t kill him#he retires to spend time with his family ☺️#unlike selfish asshole canon ice ‼️🤬#/s#this post gets DEEP into it but i find this stuff sooo interesting#got really into defense policy & missing the forest for the trees#i will admit that#military bad? yes but.#but defense policy so interesting anyway.#tom iceman kazansky#top gun#top gun maverick#icemav#edts notes#asks#last post of the night

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marine Air’s Dark Day at Midway

Marine Aircraft Group 22’s experience at the Battle of Midway serves as a hard lesson in trying to do too much with too little.

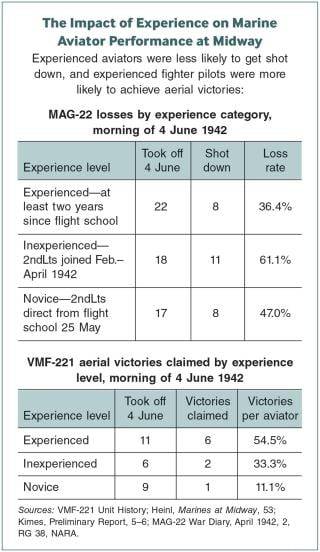

The 4th of June 1942 was a very bad day for Marine Corps aviation. At the Battle of Midway, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 22 suffered terrible losses and contributed little to the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s spectacular victory that day. The group’s fighting squadron, VMF-221, lost far more aircraft than its pilots shot down. Its dive-bomber squadron, VMSB-241, suffered staggering losses without hitting a single Japanese ship.

Midway historians have thoroughly chronicled the actions of these two squadrons and touched on some reasons for their performance. The most cited causes are the obsolescence of Marine aircraft and the inexperience of Marine aviators.1 A closer examination of archival material reveals additional factors that impaired the group’s performance at Midway and new insights into why MAG-22 sent such green pilots into battle.

The heart of MAG-22’s troubles lay in its two competing missions: While forward deployed to defend an advanced base, the group also served as a de facto training command for new aviators. This alone would have undermined its combat readiness. But additional factors worked against MAG-22. In the weeks before the battle, the flight hours the group devoted to training were limited by its responsibilities to defend Midway Atoll and by logistical shortfalls. During the battle, Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 were unable to coordinate aircraft from three services based at the atoll. Finally, imprecise direction from Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz led to misunderstandings of how MAG-22 would employ its fighting squadron.

Present-day naval commanders are acutely familiar with the challenge of balancing combat readiness and forward presence. As naval leaders look for ways to maintain Navy and Marine Corps forces in the western Pacific and prepare for possible conflict there, the experience of MAG-22 at Midway provides a sobering reminder of the risks of attempting to do too much with too little.

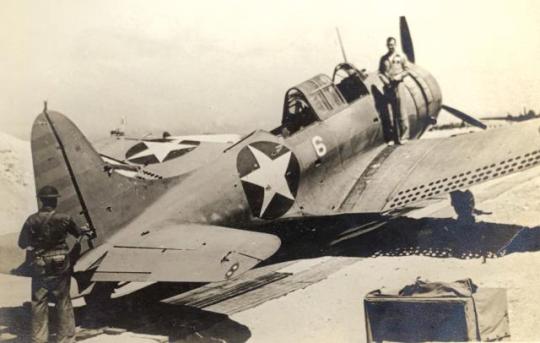

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida.

At Midway, First Lieutenant Daniel Iverson stands on a wing of his shot-up SBD-2 Dauntless, one of MAG-22’s 46 aircraft losses in the Battle of Midway. Later repaired in the United States, the restored SBD is now an exhibit at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. National Naval Aviation Museum

MAG-22’s Very Bad Day

At 0555 on 4 June 1942, Midway’s radar detected a large formation of aircraft 93 miles northwest of the atoll. MAG-22’s siren wailed. In accordance with orders issued the previous evening by Lieutenant Colonel Ira L. Kimes, the commander of MAG-22, VMF-221 launched its aircraft immediately. A detachment of six Navy TBF Avengers took off next, followed by four Army Air Forces B-26 Marauders armed with torpedoes. The TBFs and B-26s proceeded independently to attack the Japanese carriers. The 16 SBD-2 Dauntlesses and 12 SB2U-3 Vindicators of VMSB-241 took off last and rendezvoused about 20 miles east of Midway’s Eastern Island.2

VMF-221’s commanding officer, Major Floyd B. Parks, had organized his 21 F2A-3 Buffalos and seven F4F-3 Wildcats into four divisions of Buffalos and one of Wildcats. All but one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 were mission ready and got airborne, though the divisions became slightly disorganized during the hasty scramble. The Japanese strike consisted of 108 aircraft—36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, 36 Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” carrier attack aircraft, and 36 Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zeke,” or Zero, fighters. In accordance with Kimes’ plan, MAG-22’s fighter direction center funneled all five of VMF-221’s divisions to intercept the incoming strike. The Marines had the altitude advantage, and the separate divisions launched a series of overhead gunnery passes against the Japanese bomber formations. As the slower Marine aircraft recovered for additional passes, the nimbler Zeros overtook them and sent one after another tumbling downward.3

There is little doubt VMF-221 got the worst of the fight. The Japanese shot down 15 Marine fighters and severely damaged another nine, leaving just one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 ready to fly. Though Kimes afterward estimated Japanese losses at 43 aircraft, his surviving pilots definitively claimed just nine victories. Kimes’ estimate included “probable victories by missing fighter pilots” as well as claims by rear-seat gunners of VMSB-241.4 The actual total was far lower. VMF-221 probably shot down just three aircraft outright. Another 16 Japanese aircraft survived the raid but either ditched or were so irreparably damaged they could not fly again.5

A PBY Catalina flying boat had spotted the Japanese carriers, and MAG-22 passed their location to VMSB-241.6 Major Lofton R. Henderson, the squadron commander, led the SBDs. Major Benjamin W. Norris, the executive officer, led the SB2Us. While Henderson took his unit to 9,000 feet, Norris climbed to 13,000 feet.7 On paper, the SB2U-3s were nearly as fast as the SBD-2s, but the two flights proceeded independently.8

Because the Marine dive bombers were slower than the TBFs and B-26s, had taken off last, and had flown east before heading northwest, VMSB-241 did not attack until a half hour after the TBF and B-26 attacks had ended. The Japanese combat air patrol had shot down five of the six Avengers and two of the four Marauders; none had scored a hit. When Henderson and his SBDs spotted the carrier Hiryū at about 0755, the Japanese combat air patrol still had 13 fighters aloft.9

Henderson conducted a glide-bombing attack. A dive-bombing attack would have facilitated bombing accuracy and complicated fighter gunnery and antiaircraft solutions. But more than half of Henderson’s pilots were too inexperienced to attempt the technique, and the cloud cover would have made dive bombing particularly difficult.10

The combat air patrol’s Zeros attacked Henderson first. On their second pass, they sent him down in flames. The remaining SBDs continued the gliding attack. One by one, the Marines released their bombs—and missed. Some came petrifyingly close for the Hiryū’s crew, and many Marines mistakenly believed they had scored hits.11

Norris and his Vindicators arrived at about 0820, less than ten minutes after the surviving SBD-2s had departed and amid an attack by Army Air Forces B-17 Flying Fortresses. The combat air patrol had doubled to 26 fighters. Norris descended through the clouds toward the carrier Akagi. The Zeros could not find the dive bombers as long as they were in the safety of the cloud bank, but neither could the Marines see the ships below. When they emerged at 2,000 feet, they saw only the battleship Haruna. Norris also attempted a gliding attack. The Haruna maneuvered evasively, neatly avoiding every one of the Marines’ bombs. The SB2Us hugged the surface and flew back to Midway.12 Only 8 of VMSB-241’s 16 SBD-2s and 8 of its 12 SB2U-3s returned.13

VMSB-241 conducted two more strikes during the battle. That evening Norris led five SB2U-3s and six SBD-2s in a vain search for burning carriers. They found nothing, and Norris did not return, lost in the inky, moonless squalls. On 5 June, VMSB-241 attacked the cruisers Mogami and Mikuma. The squadron lost another Vindicator to antiaircraft fire and again scored no hits.14

What Was Done Well

MAG-22 did some things remarkably well in its first action. Due to superb intelligence and early warning, no airworthy planes were caught on the ground. The fighter direction center placed the fighters in an optimum intercept position. The dive bombers located the Japanese carriers. Most impressively, every fighter and dive-bomber pilot attacked without hesitation into the teeth of a formidable defense.

MAG-22’s efforts indirectly contributed to the destruction of the Akagi and two other carriers, the Kaga and Sōryū, later that morning. As historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully demonstrated, the cumulative effect of the series of failed attacks by bombers from Midway and U.S. carriers created conditions that delayed Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s counterattack and placed his carriers at greater vulnerability to the dive bombers from the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and Yorktown (CV-5). Dodging the attacks required the carriers to maneuver violently. Defending against them required the carriers to launch and recover fighters. Perhaps just as important, Nagumo faced a series of menacing dilemmas, complicating his decision-making. When the dive bombers from the Enterprise and Yorktown appeared overhead at 1020, Kates and Vals were still below on the hangar decks, where their fuel and ordnance amplified the destructive power of the American bombs.15

VMF-221 also helped reduce the strength of Nagumo’s counterpunch when it did come. The only carrier that survived the Enterprise and Yorktown dive-bomber attacks was the Hiryū. It was her air group that VMF-221 had attacked. Though the Marine fighters shot down just two Kates outright, another seven Kates were shot down by Marine antiaircraft guns, ditched, or were too damaged to participate in the strikes against the U.S. carriers.16 In other words, the Marines did not bring down many aircraft, but the ones they did bring down were the right ones—aircraft from the Hiryū’s air group.

Nonetheless, 4 June had been an awful day for MAG-22. It had lost many aircraft, shot down only a handful of the enemy, and hit no ships. Forty-two MAG-22 Marines had died; 36 pilots and gunners were missing; and six Marines had been killed in the bombing of Eastern Island.17

‘Not a Combat Airplane’

On 17 April, Major (soon to be Lieutenant Colonel) Ira L. Kimes (below) landed at Midway Atoll to replace Lieutenant Colonel William Wallace as MAG-22 commander. Accompanying Kimes were six second lieutenants, green aviators who replaced six captains, seasoned fliers, who left the atoll with Wallace three days later. Public Domain

Every surviving Marine fighter pilot from VMF-221 attested to the superiority of the Zero over the Marine fighters. Captain

The F2A-3 is not a combat airplane. It is inferior to the planes we were fighting in every respect.

It is my belief that any commander that orders pilots out for combat in a F2A-3 should consider the pilot as lost before leaving the ground.18

Kimes agreed. In his endorsement to his aviator’s statements, Kimes recommended that the fleet relegate the F2A-3 Buffalo, the F4F-3 Wildcat, and the SB2U-3 Vindicator to training commands.19

The Vindicator was indeed past its usefulness. However, there is evidence that neither fighter was to blame for VMF-221’s poor performance. With improved tactics, Marine and Navy pilots would achieve far better results with the F4F in the Solomons. Captain Marion Carl, the only Marine to shoot down a Zero over Midway, believed the F2A-3 was as maneuverable and fast as the F4F-3, and its only drawbacks were that it could not absorb punishment and was less stable as a gunnery platform than the Wildcat.20

Some British and Dutch Buffalo aces, whose squadrons suffered grievously against Imperial Japanese Navy Zeros, attributed their lopsided outcome to Japanese proficiency and numbers rather than the Buffalo’s inferiority. Finnish Buffalo pilots enjoyed great success flying the planes against the Soviets.21 The Buffalo’s mixed performance in other theaters suggests that other factors contributed to VMF-221’s poor performance.

‘Half-Baked Flyers’

When VMF-221 and VMSB-241 had landed on Eastern Island in December 1941, both squadrons were top heavy with experience. VMF-221’s most junior pilot had been flying for at least a year since flight school.22 But the 57 aviators who flew on 4 June included 35 second lieutenants, none of whom had been with their squadron more than four months, and 17 of whom had arrived on 27 May directly from flight school.23

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles.

SB2U-3 Vindicator dive bombers take off from Midway’s Eastern Island in early June, possibly to attack Japanese carriers the morning of 4 June. While inferior aircraft—including Vindicators—were factors in MAG-22’s poor performance at Midway, tactics and training played key roles. U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

In the first half of 1942, Marine aviation had two conflicting missions: defending the fleet’s advanced bases and training new aviators. Newly winged aviators reported to the fleet with just 200 hours of flight time, and none in the aircraft they would fly in combat.24 The new aviators needed operational training, but the aircraft they needed to train in were defending advanced bases in the Pacific.

On 8 January 1942, Brigadier General Ross E. Rowell, the commander of 2d Marine Air Wing, described the dilemma in a letter to Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., the commander of Aircraft, Battle Force, Pacific Fleet: “I have now accumulated 35 second lieutenants in various stages of advanced training. . . . If ComAirBatFor approves and you want some half-baked flyers, send me a dispatch to that effect.” Halsey approved; he directed Rowell to order the green fliers to squadrons like VMF-221 and VMSB-241.25 This decision set in motion a sequence of personnel transfers that diluted the combat readiness of forward-deployed squadrons. As inexperienced aviators joined squadrons at advanced bases, experienced aviators left to form new squadrons in Hawaii and California.

Marine aviation was still following its prewar training pipeline. Once students were designated naval aviators, they reported to squadrons in the Fleet Marine Force for about a year of operational flight training in combat aircraft.26

Not only did MAG-22 not have a year to train its new aviators, but the group’s commitment to the defense of Midway also required it to devote most of its operational flights to patrols and radar calibration vice gunnery and tactics. Less than 30 percent of VMF-221’s missions from December 1941 to May 1942 were dedicated to improving the lethality of its fighter pilots.27

Logistics shortfalls further impinged on the group’s training. A shortage of .50-caliber machine-gun ammunition often limited gunnery practice to dummy runs.28 In the final week before combat, PBY Catalinas and B-17 Flying Fortresses drew thirstily from Midway’s fuel stocks, which were already limited due to an incredible blunder. On 22 May, demolition charges placed at an underground fuel storage facility detonated when one of the defense battalion batteries fired its 11-inch guns. The station lost 375,000 gallons of precious aviation fuel and its pipeline to Eastern Island.29 The resulting shortage prevented the group from providing the 17 Marines fresh out of flight school with anything more than familiarization flights. VMSB-241 could not even check out its new pilots in their SBDs.30

Without question, MAG-22 fought the Battle of Midway with inferior aircraft and many “half-baked” pilots. Though the odds were stacked against the group’s aviators, command decisions may have stacked the odds higher than they needed to be.

‘No Organized Plan Whatsoever’

In a 1966 interview, MAG-22’s former executive officer stated there had been “no organized plan whatsoever” to coordinate Midway’s Army Air Forces, Navy, and Marine aircraft.31 Though not strictly true, his characterization betrays how Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 struggled to coordinate air operations.

In anticipation of the coming fight, Nimitz had abundantly reinforced Midway. In addition to MAG-22, Midway’s air force included 31 PBYs, 17 B-17s, the 4 B-26s, and the 6 TBFs. Nimitz assigned tactical control of all these to the naval air station commander, Navy Captain Cyril T. Simard, and sent an experienced aviator and a naval base air defense detachment to coordinate air operations.32

While the naval air station directed scouting operations superbly, integrating the bombers in a coordinated strike proved beyond its reach. Each aircraft type attacked without regard to the next, permitting the Japanese the opportunity to fend off each in turn. As Kimes observed in perfect hindsight, “It would have been better had they arrived simultaneously.”33

Coordination was exacerbated by the physical separation of the naval air station and MAG-22 command posts. Simard and his air operations officer were on Sand Island; Kimes and his command post were on Eastern Island. According to Kimes’ executive officer, the “Marines ran their own show” but did not command the other services’ bombers on Eastern Island, including the six Navy TBFs.34

Kimes’ air group struggled to coordinate its own aircraft. VMSB-241 does not seem to have attempted to integrate its SBD and SB2U attacks. Most puzzlingly, MAG-22 allocated no fighter protection to VMSB-241 for its strike against the Japanese carriers.

‘Go All Out for the Carriers’

Kimes employed his fighting squadron in what Marine Corps doctrine termed “general support.” As then–Major William J. Wallace lectured Marine officers at Quantico in 1941, general support was an offensive mission that allowed fighters the freedom to be “on the prowl.” In contrast, missions that tied fighters to protection missions, such as escorting bombers, were termed “special support.” As a fighter pilot, Wallace clearly favored the freedom to go find trouble and emphasized, “The rule, then, for the employment of fighter units should be-—general support wherever and whenever possible.”35

In January 1942, now–Lieutenant Colonel Wallace took command of Marine aviation on Midway, which he retained until relieved by Kimes in April. It was Wallace who had developed the fighter direction system MAG-22 employed for defense of the atoll. As Wallace’s views on fighter employment reflected Marine Corps doctrine, and Wallace commanded MAG-22 until two months before the battle, this bias likely influenced Kimes’ decision to place all of VMF-221 in general support on 4 June.

MAG-22’s fighter employment stands in stark contrast to how Japanese and U.S. carrier task forces operated on 4 June. Carriers were far more vulnerable to air attack than an island base. Nonetheless, every Japanese and American task force commander allocated fighter escorts to increase their bombers’ chances of getting through the enemy’s fighters.

Hitting the Japanese fleet was exactly what Nimitz had in mind when he reinforced Midway with so many aircraft. On 20 May, Nimitz provided the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King, with some views on the role of land-based aircraft he had drawn from the recent Battle of the Coral Sea:

The shore commander should assign attack missions designed to render the greatest possible assistance to the Fleet Task Force when it is engaged and should particularly be ready to provide fighter protection when it is practicable.36

Nimitz incorporated these views in his planning guidance for Midway. In a 23 May memorandum to his chief of staff, Captain Milo F. Draemel, Nimitz explicitly directed that “Midway planes must thus make the CV’s [aircraft carriers] their objective, rather than attempting any local defense of the atoll.”37 In an undated memorandum likely written about the same time, Nimitz reiterated his intent to Captain Arthur C. Davis, his air officer:

Balsa’s [Midway’s] air force must be employed to inflict prompt and early damage to Jap carrier flight decks if recurring attacks are to be stopped. Our objectives will be first—their flight decks rather than attempting to fight off the initial attacks on Balsa. . . . If this is correct, Balsa air force . . . should go all out for the carriers . . . leaving to Balsa’s guns the first defense of the field.38

But in his operations order for Midway, Nimitz was less clear in the tasks he assigned to Simard at Midway:

(1) Hold MIDWAY.

(2) Aircraft obtain and report early information of enemy advance by searches to maximum practicable radius from MIDWAY covering daily the greatest arc possible with the number of planes available between true bearings from MIDWAY clockwise two hundred degrees dash twenty degrees. Inflict maximum damage on enemy, particularly carriers, battleships, and transports.

(3) Take every precaution against being destroyed on the ground or water. Long range aircraft retire to OAHU when necessary to avoid such destruction. Patrol planes fuel from AVD [seaplane tender] at French Frigate Shoals if necessary.

(4) Patrol craft patrol approaches; exploit favorable opportunities to attack carriers, battleships, transports, and auxiliaries. Observe KURE and PEARL and HERMES REEF. Give prompt warning of approaching enemy forces.

(5) Keep Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander Hawaiian Sea Frontier fully informed of air searches and other air operations; also the weather encountered by search planes.39

The very explicit language Nimitz used in his planning guidance—that Midway’s aircraft “should go all out for the carriers”—is not reflected in his order. Absent such direction, Simard left it to Kimes to command the Marine squadrons as he saw fit. In accordance with Marine Corps doctrine, Kimes placed his fighting squadron in general support over Midway—and sent his dive bombers against the Japanese fleet without fighter escorts. Had he allocated one or two divisions from VMF-221 to escort VMSB-241, more Marine dive bombers may have survived to drop bombs on the Hiryū, and their accuracy may have improved had they attacked with less interference from the Japanese combat air patrol.

Trying to Do More with Less

MAG-22 had not gone all out for the carriers but had massed its fighters in defense of Midway. Naval Air Station Midway had struck the Japanese carriers with every bomber available but had been unable to coordinate their attacks to increase their chances for success and survival. Most tragically, many of the Marines lost in the battle were just not ready to fight the Imperial Japanese Navy, despite their willingness and eagerness to try.

MAG-22’s very bad day is a cautionary tale. Trying to do more with less—in MAG-22’s case, trying to defend Midway while training novice aviators—carries risks that may be hidden until they are exposed through combat. In his report of the battle, Kimes included a page and a half of candid comments and recommendations.40 After Midway, Marine aviators applied the lessons MAG-22 had learned at enormous cost and achieved spectacular results against the same foe in the Solomons, often under the leadership of aviators who had survived Midway.

Those same lessons are noteworthy today. Naval experts have cautioned the naval services against maintaining too much forward presence with too little fleet.41 An enduring lesson of MAG-22 may be that very bad days result from very bad choices, and that choosing to do more with less is often a very bad choice.

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

What is the closest military base to the white house?

The White House IS a military installation.

It is the home and workplace of the Commander-in-Chief of United States military forces, so that alone makes it an important command and control headquarters. The various branches of the military have an active role in the everyday logistics of running the White House campus and supporting the Executive Office of the President. The White House's complex and extensive communications agency is staffed by members of each individual branch of the military. The U.S. Navy is responsible for the White House Mess and providing food services to the President, the First Family, any potential guests, and the President's staff. The White House Medical Unit is staffed by military doctors who have a round-the-clock presence in the White House and the official Physician to the President is usually an active-duty military officer.

While the Secret Service -- which includes the traditional plainclothes agents and the more visible uniformed division -- is responsible for protecting the President, his family, and the White House itself, the military also has a protective footprint in and around the White House complex. It's believed that amongst the White House's protective measures -- most of which are highly classified -- are anti-aircraft defenses, which are almost certainly manned by the military rather than the Secret Service. Marine Corps guards also are stationed at the White House (often seen opening and closing doors while manning the entry and exit points around the West Wing) as sentries and sometimes act as military valets during events hosted by the President in the White House. The role of the Marine sentries is purely ceremonial as opposed to protective.

And one of the most important White House responsibilities of the military is transportation. The White House Transportation Agency is responsible for all aspects of the President's travel, and the military works in tandem with the Secret Service on planning and carrying out the immense logistical challenges of transporting the President anywhere in the world -- a challenge magnified by the sheer size of Presidential traveling parties. A Presidential motorcade consists of, on average, 50-60 vehicles. And the majority of those vehicles actually have to be transported from the United States to wherever the President is traveling -- even if it is to several different foreign countries or continents. The Air Force is, obviously, responsible for the President's plane, along with any other aircraft making the trip which are usually carrying White House staff, members of the press, or cargo. For short distances that can be made by helicopter, the Marine Corps takes the lead. And any ground travel by motor vehicles is handled by the Army.

Security and the President's personal protective detail is always led by the Secret Service, but the military is responsible for many of the day-to-day logistics of the institution of the Presidency, which illustrates why the White House is an important military command and control base.

#White House#Presidency#Commander-in-Chief#U.S. Military#Military Bases#Military Installations#Command and Control#White House Communications Agency#Communications#White House History#Military History#U.S. Army#U.S. Air Force#U.S. Marine Corps#U.S. Navy#White House Mess#White House Transportation Agency#White House Sentries#U.S. Secret Service#Secret Service#Presidential History#History#Presidential Motorcade#Air Force One#Marine One#The Beast#Executive Office of the President#Presidents

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Don’t mind me, just making a self-reference checklist for my clone encyclopedia, nothing to see here)

GAR

ARC CLASS

ARC

ARC MEDIC

ARC HEAVY INFANTRY

ALPHA

NULL

BARC / BIKER ARC / LANCER

NAVY / CC-CT CLASS

TROOPER / INFANTRY

LOGISTICS / SUPPLY

OFFICER

NAVIGATION OFFICER

CORPORAL

LIEUTENANT

SERGEANT

MAJOR

GRENADIER

GUNNER

MAINTENANCE TECH

FLIGHT CREW

COMMS TECH

COLD ASSAULT

HEAVY INFANTRY

COMMANDO CLASS

MARSHALL COMMANDER

CLONE COMMANDER

CAPTAIN

ENGINEER

PILOT

MEDIC

SNIPER

SCOUT

ARTILLERY

ARF CLASS

ARF

GUARD DETECT / SECURITY CORP / MASSIFF TROOPER

ORDNANCE / BOMB UNIT

SHADOW ARF

ARF SCOUT

MARINE / MEC CLASS

MARINE

AERIAL RECON

FLAME TROOPER

SPECIAL OPERATIONS

SCUBA (SUB)

JET UNIT

BLAZE / ZERO-G

PARATROOPER

[Certifiably insane at this point. But for some reason, I had to have a military that made sense for this single fanfic I wanted to write. Wack.

I'll hopefully add full scans to each unit type. It's all because I wanted to actually make a sensible military model, and design armour. I will hopefully also have options for phase 1, phase 2, and the theoretical phase 3 armour types.

This is the REDUCED Unit variety. The wiki, and what I can find from forums have even more unit types, but I can't see anything different regarding symbols, or kit, so this is the current list. For now.]

#clone troopers#grand army of the republic#GAR#clone wars#clones#Star Wars Military#clone trooper models and blanks#star wars meta#clone wars fanon#clone commanders#clone captains#clone medics#clone commandos#star wars lore#star wars reference#clone wars reference

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Marine is in custody after authorities found a 14-year-old girl in the barracks of a California base in late June after she had run away from her grandparent's home earlier in the month, according to reports.

Melissa Aquino of the San Diego County Sheriff's Department first confirmed the news to NBC San Diego, saying the 14-year-old girl's grandmother reported her missing four days after her initial disappearance June 9. Aquino said the girl had run away from home before, but "always returned home quickly."

The girl was found June 28 by military police at the Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California. Neither the girl nor the Marine in custody have been publicly identified.

Marijuana in the military? A push in Congress would loosen cannabis rules, ease recruitment crisis

According to Capt. Charles Palmer, the director of communications strategy and operations for the 1st Marine Logistics Group, the Marine was taken into custody for questioning June 28 by Naval Criminal Investigative Services, a military law enforcement agency, he told NBC. Palmer said the Marine has not been formally charged, and remains in the custody of his command.

The sheriff's department said the teen has been returned to her grandmother, CNN reported.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Airbus Awarded US NAVAIR Contract to Develop US Marine Corps Aerial Logistics Connector

Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) awarded Airbus U.S. Space & Defense a Phase I Other Transactional Authority Agreement, through Naval Aviation Systems Consortium, in support of the United States Marine Corps Aerial Logistics Connector. The award is part of a Middle Tier of Acquisition (MTA) Rapid Prototyping Program which aims to provide the USMC with prototypes to demonstrate the aircrafts capabilities to the warfighter through a series of operationally experiments. The Airbus U.S. UH-72 Unmanned Logistics Connector, a variant of the proven Lakota platform, is intended to provide logistical support during expeditionary operations within contested environments. The unmanned autonomous helicopter is the low risk, affordable solution for the contested logistics problem. #military #defense #defence #militaryleak #hrlicopter

Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) awarded Airbus U.S. Space & Defense a Phase I Other Transactional Authority Agreement, through Naval Aviation Systems Consortium, in support of the United States Marine Corps Aerial Logistics Connector. The award is part of a Middle Tier of Acquisition (MTA) Rapid Prototyping Program which aims to provide the USMC with prototypes to demonstrate the aircrafts…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

General Officer Announcements

View Online IMMEDIATE RELEASE General Officer Announcements May 9, 2024 Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III announced that the president has made the following nominations: Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Sklenka for appointment to the grade of lieutenant general, with assignment as deputy commandant for Installations and Logistics. Sklenka is currently serving as the deputy commander,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Governor Whitmer Announces Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation and Executive Director Appointment

Col. John Gutierrez, USMC (Ret.) to Lead Michigan's Defense and Aerospace Industry Growth

Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer has unveiled the new Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation (ODAI) as part of the state's efforts to boost its defense and aerospace industry. The ODAI aims to increase awareness of Michigan's capabilities, attract and expand businesses involved in Department of Defense-related activities, and support the growth of the commercial and defense-related aerospace sectors. Col. John Gutierrez, a retired U.S. Marine Corps officer with extensive military experience, has been appointed as the executive director of the ODAI.

"Michigan is all-in on defense," Governor Whitmer stated. "With our new Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation and its new director, we are positioning Michigan to build on its long, proud legacy of leadership in these sectors."

youtube

Col. John Gutierrez: A Leader with Decades of Military Expertise

Col. John Gutierrez brings over thirty years of experience in acquisition, operational, and joint assignments to his new role as the executive director of the Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation. His military career began in 1990 when he enlisted in the U.S. Naval Reserve as a Hospital Corpsman.

In 1996, he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Marine Corps, where he served until 2024. Col. Gutierrez's most recent position was as the portfolio manager for Logistics Combat Element Systems at the U.S. Marine Corps Systems Command.

With a strong educational background, Col. Gutierrez holds a B.S. in biology from Arizona State University, an M.S. in management from the U.S.

Naval Postgraduate School, an M.A. in national security and strategic studies from the U.S. Naval War College, and a masters of military studies from the U.S. Marine Corps University.

He has also completed post-graduate studies in project management at George Washington University and in advanced project management at Stanford University. Additionally, he is a graduate of the Joint Forces Staff College.

Michigan's Defense and Aerospace Industry

The defense industry in Michigan contributes $30 billion to the state's economy, supporting over 116,000 jobs and involving nearly 4,000 Michigan businesses. The state is home to five major installations of the Michigan National Guard, including the National All-Domain Training Center in Grayling and one of the largest Air National Guard bases in the nation at Selfridge in Macomb County.

The Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation will focus on growing defense and aerospace-related jobs in Michigan, increasing federal Department of Defense spending in the state, and supporting research and development in the industry. It will also promote innovation and testing in advanced aerial mobility for both defense and commercial applications.

Support for the Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation

The establishment of the Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation has received support from various stakeholders. U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Paul D. Rogers, adjutant general of the Michigan National Guard, expressed his enthusiasm for the collaboration between the ODAI and the National Guard, which aims to maximize the potential of training facilities through investment and awareness.

The NDIA Michigan Chapter, representing the National Defense Industrial Association, also expressed its support for Col. Gutierrez's appointment and the ODAI's mission. Valde Garcia, president of NDIA Michigan, emphasized the potential for Michigan's defense sector to gain recognition, funding, and programs.

Other supporters include Tammy Carnrike, chief operating officer of the Detroit Regional Chamber and civilian aide to the secretary of the Army (CASA) Michigan, who highlighted the economic impact and job opportunities in the defense and aerospace industry. Mark Hackel, Macomb County Executive, and Sean Carlson, Oakland County Deputy County Executive, both expressed their commitment to advancing defense and aerospace initiatives in their respective regions.

The establishment of the Office of Defense and Aerospace Innovation in Michigan marks a significant step in the state's efforts to strengthen its defense and aerospace industry. With Col. John Gutierrez at the helm, the ODAI aims to leverage Michigan's capabilities, attract businesses, and support the growth of defense and aerospace-related jobs. By focusing on innovation, research, and development, Michigan is positioning itself as a leader in the defense and aerospace sectors, contributing to the state's economic growth and national security.

0 notes

Text

Military students innovate technology solutions for US Special Operations Command

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/military-students-innovate-technology-solutions-for-us-special-operations-command/

Military students innovate technology solutions for US Special Operations Command

All eyes were on the robot-dog pacing the hangar on Hanscom Air Force Base. The robot was just one technology, among small drones, autonomous mapping vehicles, and virtual-environment simulators, set up for military cadets to interact with. The goal was to open cadets’ minds to possibilities. Over the next year, they will be applying such technologies to challenges facing the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) for a program called SOCOM Ignite.

SOCOM Ignite connects military students with research scientists and special operations forces to address SOCOM’s pressing technology challenges, while ushering in new generations of technology-savvy officers and operators. Now in its fourth year, the program invites cadets from across the nation’s military academies and Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) programs to participate.

“We started as just a two-day hackathon having less than 10 cadets, and now we are a year-long program with more than 80 cadets from more than 19 different universities, representing the Army, Navy, and Air Force. We hope to extend to the Marines and any other group out there,” says Raoul Ouedraogo, who helped establish the program and is a leader within MIT Lincoln Laboratory’s Homeland Sensors and Analytics Group.

Lincoln Laboratory researchers serve as the technical mentors in the program. To start the program this year, they offered new “innovation incubators,” or crash courses on the basics of machine learning and autonomy, two topics of high interest to SOCOM. Following those sessions, a formal kick-off ceremony brought in SOCOM leaders to explain the impact of the program for the command’s mission. SOCOM is the nation’s only unified combatant command that oversees special operations forces across all branches of the armed services.

“What makes SOCOM so important to the Department of Defense is that we are pathfinders. We look at advanced concepts, take those visions and dreams, and make them real,” says SOCOM Senior Enlisted Leader (Retired) Greg Smith.

“We have a mix of academy cadets and ROTC students, providing diverse perspectives. We have access to users in the SOCOM community, whose time is precious, and to technology mentors, who do this for a living. Those three things make this a unique program,” Lisa Sanders, the director of science and technology for Special Operations Forces, Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, USSOCOM, said at the ceremony. “SOCOM also has acquisition authority — people who get ideas on the market. The ideas that you come up with will make a meaningful difference.”

After the opening ceremonies, the cadets traveled to the MIT campus for a weekend-long hackathon, which took place Sept. 16-17. At the hackathon, SOCOM operators presented more than a dozen Ignite challenges to the cadets. Cadets then formed teams to begin brainstorming concepts, working first-hand with special operations forces and laboratory technical experts to refine their ideas.

The challenges are diverse in their needs. One challenge is to develop a way to deploy air tags from small uncrewed air vehicles (UAVs) onto ground vehicles. Another is seeking algorithms and hardware to enhance autonomous UAV flight and mapping indoors. New this year, a biotechnology challenge calls for methods to improve the storage and delivery of blood in a tactical environment.

“The hackathon experience was inspiring. It was great to see such a large number of cadets coming from different institutions attend and have a desire to conduct meaningful research,” says Jack Perreault, a recent West Point graduate whose team is applying computer vision and speech recognition to the process of reporting and triaging casualties. “Getting insight on how our technical skills can help enable operators achieve their missions has left the greatest impact on me overall.”

The cadets will continue working on their concepts and receive funding to build prototypes throughout the school year. Over the winter, some might visit Fort Liberty, which houses the headquarters of the U.S. Army Special Operations Command, to showcase their solutions to users and update SOCOM leaders on their progress. In the spring, they’ll return to Lincoln Laboratory for final presentations. After that, Lincoln Laboratory and various SOCOM components will take on some cadets as interns or military fellows to continue their research. Perreault is one such military fellow, developing his SOCOM solution at the laboratory while pursuing a master’s degree at Boston University.

U.S. Air Force cadet Christopher Christmas is also continuing his work as a research assistant at the laboratory. A third-time SOCOM Ignite participant, he is pursuing a system that can ingest data from distributed sensors and generate useful information, sending it to the right people and in a scalable way.

Christmas recommends SOCOM Ignite to any cadet looking for an opportunity to make an impact. “It’s an excellent leadership experience, exposing cadets to unique career fields and officers of various ranks. It has completely altered the trajectory of my life in the best way possible.”

#air#air force#Algorithms#Analytics#autonomous vehicles#biotechnology#blood#career#challenge#Christmas#communications#Community#computer#Computer vision#courses#crash#data#data analytics#defense#Department of Defense (DoD)#dog#drones#Environment#eyes#flight#Funding#generations#hand#Hardware#how

0 notes

Text

Argentine and Brazilian Navies Hold Combined Exercises

The Argentine and Brazilian navies strengthened interoperability with combined exercises Passex and Fraterno XXXVI. Service members carried out various maneuvers on the high seas, including navigation in low visibility, transit under air, and surface threat and submarine operations. Participants also visited strategic logistics ports, such as Mar del Plata in Argentina and Itajaí in Brazil.

Exercise Passex took place in Argentine jurisdictional waters, while Fraterno XXXVI was held in Brazilian waters. “Exercise Passex and Exercise Fraterno are held alternately in each of the two countries and their adjacent waters, and consist of war games and exercises at sea,” the Argentine Ministry of Defense said.

“Fundamentally, [Passex and Fraterno] contribute to optimizing the degree of interoperability between both navies, through the exchange of information based on the command and control systems of naval surface assets, submarines, aircraft, and the Marine Corps,” the Argentine Defense Ministry said of the exercises held in late August.

“Holding this exercise [Fraterno] again, after six years, is proof of the will to deepen fraternity, interoperability, and that energy that arises between both countries,” Argentina’s Defense Minister Jorge Taiana, said during the launch of the exercises at Mar del Plata Naval Base.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#argentina#brazilian politics#argentine politics#foreign policy#international politics#military#navy#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Without the CMV-22, the U.S. Navy needs 15 former C-2A to carry out missions aboard the aircraft carriers

Fernando Valduga By Fernando Valduga 02/20/2024 - 20:58in Military

The uncertainty of the return of the tiltrotor V-22 to full operation is leading the U.S. Navy to rethink its plans on how to refuel its aircraft carrier fleet in the short term, with more uncertainty in the long term, and the remaining C-2A Greyhounds become essential.

The service had initially planned to retire its remaining 15 C-2A Greyhound onboard delivery (COD) aircraft in the next two years and replace them with a total of 38 CMV-22B Ospreys, which DOT&E reported "not to be operationally adequate".

“For the luck of the Navy, the C-2 Greyhound is still available,” said Vice Admiral Air Boss Daniel Cheever at a panel at the WEST 2024 conference, co-organized by the U.S. Naval Institute and the AFCEA. "Limited operational impacts at this time, but there are still operational impacts. And when you look to the future, there are significant operational impacts."

As part of the Greyhounds' planned retirement, the U.S. Navy stopped training new C-2 pilots and began to reduce spare parts and logistical support for the 60-year project.

This transition, completed on the West Coast, is now paralyzed with the grounding of the V-22 in the U.S. Marines, Navy and Air Force after the fall of a USAF Special Operations MV-22 off the coast of Japan late last year.

The grounding of the Ospreys has already been out of operation for 75 days, with no indication of how long the grounding can continue.

CMV-22B Osprey.

The suspension of operation of the tiltrotors forced the U.S. Navy to exchange the V-22 aboard the West Coast aircraft carriers USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70) and USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) for the C-2As of the East Coast Fleet Logistics Support Squadron (VRC) 40, the "Rawhides".

"The VRC-40 is currently emerging to fulfill the mission [COD] for aircraft carriers deployed in the 5ª and 7ª U.S. Fleets," says a statement from the Naval Air Forces. "There was no change in the planned retirement of C-2A for 2026."

Although there is still no change in the plan for the C-2, there is little indication of any of the forces for how long the V-22 will be able to remain out of service. After the initial grounding of the fleet, there was very limited information about the underlying cause of the grounding, in addition to a "potential material failure".

For the Marines, the situation is more terrible, said Lieutenant Karsten Heckl during the panel. He said that the operations of the 31ª Marine Expeditionary Unit based in Japan, the 26º MEU deployed in the Bataan Amphibious Ready Group and the 15º MEU that is preparing to be deployed aboard the Boxer ARG had "dramatic impacts".

Navy officers said that Marines are allowed to use Ospreys deployed aboard the Bataan ARG in specific emergency situations. A main mission of the 26º MEU, currently deployed in the Eastern Mediterranean, is the evacuation of non-combatants from Lebanon.

Last month, the Assistant Commander of the Marine Corps, General Chris Mahoney, said that the Force risks losing proficiency with the aircraft the longer it stays on the ground.

"At some point, if a pilot does not fly, if a maintainer does not turn a wrench, if an observer or crew chief is not exercising his profession, this will become a matter of competence and then there will be a matter of safety," he said.

Tags: Military AviationCMV-22B OspreyGrumman C-2 GreyhoundUSN - United States Navy/U.S. Navy

Sharing

tweet

Fernando Valduga

Fernando Valduga

Aviation photographer and pilot since 1992, he has participated in several events and air operations, such as Cruzex, AirVenture, Dayton Airshow and FIDAE. He has works published in specialized aviation magazines in Brazil and abroad. He uses Canon equipment during his photographic work in the world of aviation.

Related news

EMBRAER

VIDEO: Embraer and Sierra Nevada demonstrate A-29 Super Tucano for Ghana Air Force

20/02/2024 - 18:08

MILITARY

Leonardo tests new technologies for sustainable flight on C-27J aircraft

20/02/2024 - 15:30

MILITARY

Manufacture of 120 KF-21 Boramae jets for the South Korean Air Force will begin this year

20/02/2024 - 13:30

MILITARY

Air exercise "Spears of Victory" allowed Pakistan to evaluate JF-17 capabilities against Rafale

20/02/2024 - 09:30

MILITARY

Argentine Air Force receives second Embraer ERJ-140LR aircraft to expand its capabilities

20/02/2024 - 08:35

MILITARY

Ukraine claims to have shot down three more Russian jets, totaling six in three days

19/02/2024 - 22:07

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dept. of Defense - Contracts Awarded on July 14, 2023

U.S. Dept. of Defense Announced Contracts Awarded on July 14, 2023 Washington, DC (STL.News) The U.S. Department of Defense released the following statement: M.A. Mortenson Co., Minneapolis, Minnesota, was awarded a $67,384,000 firm-fixed-price contract to construct a training and collaboration center. Bids were solicited via the Internet, with seven received. Work will be performed in Layton, Utah, with an estimated completion date of January 19, 2026. For fiscal 2023 military construction, Army funds for $67,384,000 were obligated at the time of the award. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Sacramento, California, is the contracting activity (W91238-23-C-0023). Applied Research Associates Inc., Albuquerque, New Mexico, was awarded a $24,128,896 cost-plus-fixed-fee contract for geospatial intelligence support services. Bids were solicited via the Internet, with one received. Work will be performed in Raleigh, North Carolina, with an estimated completion date of July 13, 2026. Fiscal 2023 defense developmental test and evaluation funds in the amount of $24,128,896 were obligated at the time of the award. Army Contracting Command, Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, is the contracting activity (W911QX-23-C-0010). General Dynamics Information Technology, Falls Church, Virginia, was awarded a $17,928,474 cost-plus-fixed-fee contract for information technology support services. Bids were solicited via the Internet, with one received. Work will be performed at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, with an estimated completion date of April 25, 2024. For fiscal 2010 operation and maintenance, Army funds in the amount of $17,928,474 were obligated at the time of the award. Army Contracting Command, Detroit Arsenal, Michigan, is the contracting activity (W50NH9-23-C-0009). Lockheed Martin Corp., Orlando, Florida, was awarded an $11,900,000 firm-fixed-price contract for Common Sensor Electronic Unit engineering support. Bids were solicited via the Internet, with one received. Work locations and funding will be determined with each order, with an estimated completion date of June 30, 2026. Army Contracting Command, Redstone Arsenal, Alabama, is the contracting activity (W58RGZ-23-D-0011). Dubuque Barge and Fleeting Service Co., doing business as Newt Marine Service,* Dubuque, Iowa, was awarded an $8,654,530 firm-fixed-price contract to construct an island in the Mississippi River in order to increase floodplain forest and fish overwintering areas. Bids were solicited via the Internet, with three received. Work will be performed in Bay City, Wisconsin, with an estimated completion date of October 31, 2027. Fiscal 2023 civil construction funds in the amount of $8,654,530 were obligated at the time of the award. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, St. Paul, Minnesota, is the contracting activity (W912ES-23-C-0009). Weston Solutions Inc., Albuquerque, New Mexico, was awarded a $7,750,313 (P00006) modification to contract W912DY-20-F-0475 for regular and recurring maintenance for Defense Logistics Agency facilities. Work will be performed in Albuquerque, New Mexico, with an estimated completion date of August 13, 2024. Fiscal 2023 revolving funds in the amount of $7,750,313 were obligated at the time of the award. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineering and Support Center, Huntsville, Alabama, is the contracting activity. Air Force Contractor Integrated Data Services, El Segundo, California, has been awarded a $99,997,000 firm-fixed-price contract for comprehensive cost and requirements. This contract provides subject matter expert support for web comprehensive costs and requirements. Work will be performed at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, and is expected to be completed by July 31, 2028. This contract was a sole-source acquisition. Fiscal 2023 procurement funds in the amount of $2,814,092 are being obligated at the time of award. The Air Force Life Cycle Management Center, Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio, is the contracting activity (FA8604-23-D-B004). (Awarded July 13, 2023) Frontline King George JV LLC, Silver Spring, Maryland, was awarded a $47,185,098 firm-fixed-price, indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract for civil engineering facility and equipment support services. This contract provides for all personnel, tools, supervision, and other items and services, to perform civil engineering support of government equipment and facilities for multiple customers located at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio. Work will be performed at Wright Patterson AFB, Ohio, and is expected to be completed by August 31, 2028. This contract was a competitive acquisition, and eight offers were received. No funds will be allocated at the time of award. Air Force Life Cycle Management Center, Wright Patterson AFB, Ohio, is the contracting activity (FA8601-23-D-0009). L3Harris Technologies Inc., Colorado Springs, Colorado, has been awarded a $17,000,000 contract modification (P00203) to previously awarded contract FA8823-20-C-0004 for period four Space Fence System Sustainment Services. The modification brings the total cumulative face value of the contract to $705,851,350. Work will be performed in Colorado Springs, Colorado; Kwajalein Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands; Eglin Air Force Base, Florida; and Huntsville, Alabama, and is expected to be completed by January 31, 2024. Fiscal 2023 operations and maintenance funds in the amount of $11,000,000 are being obligated at the time of award. The Space Systems Center Directorate of Contracting, Peterson Space Force Base, Colorado Springs, Colorado, is the contracting activity. Textron Systems Corp., Hunt Valley, Maryland, was awarded a $12,018,807 firm-fixed-price contract for the repair of Joint Service Electronic Combat System Tester internal components. This contract provides for an end-to-end functional testing capability to determine the status of an electronic combat system installed in or on operational aircraft. Work will be performed in Hunt Valley, Maryland, and is expected to be completed by July 13, 2028. This contract was a sole-source acquisition. No funds are being obligated at the time of award. The Air Force Sustainment Center, Robins Air Force Base, Georgia, is the contracting activity (FA8517-23-D-0006). D7 LLC, Colorado Springs, Colorado, was awarded a $11,054,453 firm-fixed-price contract for the design and build renovation project in Hangar 1002 on Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico. This contract provides a hoist crane and renovation of three floors of Hangar 1002, Island B, in preparation for the upcoming AC-130J mission. Work will be performed at Kirtland AFB, New Mexico, and is expected to be completed by December 13, 2024. This contract was a sole-source acquisition. Fiscal 2023 operational and maintenance funds in the amount of $11,054,453 are being obligated at the time of award. The Air Force Installation Contract Center, Kirtland AFB, New Mexico, is the contracting activity (FA9401-23-C-0016). Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency Raytheon Missiles and Defense, Tucson, Arizona, has been awarded an $81,000,000 modification (P00072) to cost-plus-fixed-fee contract HR0011-17-C-0025, excluding unexercised options, for more opportunities with the Hypersonic Airbreathing Weapon Concept Program. The modification brings the total cumulative face value of the contract to $352,950,076 from $271,950,076. Work will be performed in Tucson, Arizona (99%) and Point Mugu, California (1%), with an estimated completion date of January 2026. Fiscal 2022 research and development funds in the amount of $114,734; and fiscal 2023 research and development funds in the amount of $57,068,058 are being obligated at the time of award. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, Arlington, Virginia, is the contracting activity. U.S. Special Operations Command Teledyne FLIR Surveillance Inc., North Bellerica, Massachusetts, is being awarded an $8,317,505 firm-fixed-price, cost-plus-fixed-fee, indefinite-delivery/indefinite-quantity contract (H-92241-23-D-0010) to provide Life-Cycle Contractor Support for the AN/ZSQ-3 Electro-Optical Infra-Red Imaging System for the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) Technology Applications Program Office. Fiscal 2023 operations & maintenance funding in the amount of $1,484,204 is being obligated at the time of award. The majority of the work will be performed in Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and is expected to be completed by June 30, 2028. This was a non-competitive award in accordance with Federal Acquisition Regulation 6.302-1. USSOCOM, MacDill Air Force Base, Florida, is the contracting activity. SOURCE: U.S. Department of Defense Read the full article

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

US Marine Corps Conduct Long-range Convoy Throughout Saudi Arabia

U.S. Marines and Sailors with 2nd Distribution Support Battalion, Combat Logistics Regiment 2, 2nd Marine Logistics Group, 4th Law Enforcement Battalion, Force Headquarters Group, U.S. Marine Corps Forces Reserve, Army Soldiers with 541st Division Sustainment Support Battalion, Sustainment Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, and members of the Royal Saudi Armed Forces, conduct a long-range convoy during exercise Native Fury 24 throughout the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), May 8, 2024. U.S. and partner forces engaging in on-load and off-load operations using commercial maritime shipping, long-distance convoys, urban combat training, and various dynamic training events in both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The KSA, the UAE, and U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Central Command (USMARCENT) launched Exercise NATIVE FURY 24 (NF 24) at a Saudi Naval Port on May 5, 2024. In its 8th iteration, NF24 will showcase U.S. and partner forces engaging in on-load and off-load operations using commercial maritime shipping, long-distance convoys, urban combat training, and various dynamic training events in both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The constellation of exercises happening in multiple countries at once demonstrates USCENTCOM’s capability to project power abroad and conduct advanced training in cooperation with our partners across the region. #military #defense #defence #militaryleak

U.S. Marines and Sailors with 2nd Distribution Support Battalion, Combat Logistics Regiment 2, 2nd Marine Logistics Group, 4th Law Enforcement Battalion, Force Headquarters Group, U.S. Marine Corps Forces Reserve, Army Soldiers with 541st Division Sustainment Support Battalion, Sustainment Brigade, 1st Infantry Division, and members of the Royal Saudi Armed Forces, conduct a long-range convoy…

View On WordPress

0 notes