#Manfred Krebernik

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Ninshubur(s), Ilabrat, Papsukkal and the gala: another inquiry into ambiguity and fluidity of gender of Mesopotamian deities

Yesterday I’ve mentioned in passing that despite recommending Dahlia Shehata’s Musiker und ihr vokales Repertoire: Untersuchungen zu Inhalt und Organisation von Musikerberufen und Liedgattungen in altbabylonischer Zeit overall, I have a minor issue with the coverage of Ninshubur in this monograph - specifically with the arguments about the gender of this deity. I figured my problem warrants a more in depth explanation, not just because I’m the self-proclaimed “biggest Ninshubur fan not counting Rim-Sin I of Larsa”.

Note that while this is functionally a followup to my recent Inanna’s article, it is not the followup I’ve promised previously; that one will be released at a later date.

To begin with, in a cursory survey of figures who speak in emesal in literary texts, Shehata introduces Ninshubur as a deity equally firmly masculine as Dumuzi (Musiker…, p. 83). This is in itself a problem - when Ninshubur’s gender is specified in sources from the third millennium BCE, the name clearly designates a goddess, not a god (can’t get more feminine than being called ama); and even later on she remains a goddess in a variety of sources - including many emesal texts, which is the context most relevant here (Frans Wiggermann, Nin-šubur, p. 491).

Occasionally arguments are made that a male Ninshubur - explicitly a separate deity from “Inanna’s Ninshubur” as Manfred Krebernik and Jan Lisman recently called her - already existed in the third millennium BCE (The Sumerian Zame Hymns from Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ, p. 151), though this is ultimately conjectural.

It is true that the Abu Salabikh god list includes at least two Ninshuburs, but in contrast with later, more informative lists it provides no theological glosses, so we can’t be sure that gender is what differentiates them. For all we know it might be a geographic distinction instead - “Inanna’s Ninshubur” from Akkil and the Lagashite Ninshubur associated with Mesmaltaea, perhaps. The one case where we have a text involving two Ninshuburs which we can differentiate has the “great” (gula) Ninshubur from Uruk - “Inanna’s Ninshubur” - and the “small” (banda) Ninshubur from Enegi (Nin-šubur, p. 500; Ur III period) . The fact that there might be a third Ninshubur entry between the two certain ones in the Abu Salabikh list (The Sumerian…, p. 151) doesn’t help, either.

This is not to deny the existence of a male Ninshubur altogether. However, this is actually a fairly straightforward phenomenon, with no real ambiguity involved - possibly as early as in the Old Akkadian period, Ninshubur came to be associated with a male messenger deity, Ilabrat, and later on with equally, if not more firmly masculine Papsukkal; at first her name was used as a logogram to write Ilabrat’s, and later Papsukkal’s, but eventually it became possible to essentially speak of full replacement (or absorption) of both Ninshubur and Ilabrat by Papsukkal (Nin-šubur, p. 491-493; Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 93). Papsukkal even replaces Ninshubur up in the Neo-Assyrian derivative of Inanna’s Descent, written in Akkadian; but he is addressed as a servant of the divine assembly, not the eponymous protagonist of the myth, and the entire mourning and mediation sequence is cut (Wilfred G. Lambert, Introductory Considerations, p. 13). I feel it’s important to stress that in most cases where Ninshubur’s gender cannot be determined this is not due to intentional ambiguity, but rather due to lack of grammatical forms which would make it possible for us - in antiquity all the context needed was presumably available to the reader. Furthermore, in many such cases the ambiguity isn’t quite “what is Ninshubur’s gender?” but rather “does this theophoric name use Ninshubur as a logogram for Ilabrat or Papsukkal?” Thus, Ninshubur’s gender was not ambiguous innately and did not become ambiguous, but rather she was replaced by an originally distinct male deity - her case is thus more comparable to absorption of both male and female deities of specific professions by Enki in god lists form the first millennium BCE, if anything. Even if a separate male Ninshubur existed alongside feminine Ninshubur (or Ninshuburs) even before the entire Ilabrat/Papsukkal situation, we’d still be dealing with a similar phenomenon.

Back to Shehata’s monograph, later on she acknowledges that Ninshubur possessed “a male and female aspect” (“einen männlichen wie auch weiblichen Aspekt”) and on this basis suggests a parallel between Ninshubur and the gala (p. 85). The process of conflation of messenger deities is not discussed, instead this interpretation relies on Uri Gabbay’s The Akkadian Word for “Third Gender”: The kalû (gala) Once Again, which at the time was the most recent treatment of the matter. I won’t go into the details of that article here, since it’s for the most part not relevant (it focuses on the possible etymology of the term gala). What matters here is Gabbay’s novel proposal that Ninshubur was perceived as having the same gender identity as the gala, largely just based on her portrayal as a mourner in Inanna’s Descent and her ability to appease other deities, which was also the purpose of the performances of the gala (The Akkadian Word…, p. 53). The supporting evidence is that some of Ninshubur’s titles use the term lagar, and a single lexical list explains lagar as gala (The Akkadian Word…, p. 54) This is rather vague, and it needs to be pointed out that it has been since established with certainty that in Ninshubur’s case lagar/SAL.ḪUB2 seems to be a rare, old title with similar meaning to sukkal, and it also could be applied to other deities - ones whose gender never showed any ambiguity - in a similar way (see full discussion in Antoine Cavigneaux, Frans Wiggermann, "Vizir, concubine, entonnoir... Comment lire et comprendre le signe SAL.ḪUB2? and a brief commentary in The Sumerian…, p. 130). Furthermore, earlier in the article Gabbay recognizes the supposed connection between the terms as an error himself (The Akkadian Word…, p. 49).

I haven’t really seen any authors other than Shehata agreeing with Gabbay’s arguments about Ninshubur; in fact, while I try to keep up with relevant publications, I’ve only seen his points regarding this deity addressed at all otherwise, and quite critically at that. Joan Goodnick Westenholz disagreed with him and pointed out that in addition to Gabbay contradicting himself regarding the term lagar, a fundamental weakness of his proposal is that Ninshubur is never described as a gala (Goddesses in Context…, p. 93). As a matter of fact no deity is, though you can make a sound case for Lumha, who was a (sparsely attested) divine representation of this profession.

A further problem with Gabbay’s argument is that while it’s true gala were first and foremost professional lamenters (and I think any paper which acknowledges this deserves some credit), lamenting was hardly an activity exclusive to them. Paul Delnero considers Ninshubur’s actions in Inanna’s Descent to be a standard over the top portrayal of grief common in Mesopotamian literary texts. In other myths, as well as in laments mourning the destruction of cities or death of deities Geshtinanna, Inanna, Ninisina and other goddesses engage in similar behaviors. He assumes the detailed descriptions of deities wailing, tearing out hair, lacerating and so on were meant to inspire a sense of discomfort and grief in the audience (How to Do Things with Tears, p. 210-214). If Delnero is right - and I see no reason to undermine his argument - Ninshubur’s mourning would have more to do with what sort of story Inanna’s Descent is, not with her character. I suppose Ninshubur’s mourning is unique in one regard, though. She acts about Inanna’s death in the way sisters, mothers or spouses do in the case of Damu, Dumuzi, Lulil etc., despite not actually being her relative. I think there are some interesting implications to explore here, but so far I’ve seen no publications pursuing this topic.

Gabbay is right that Ninshubur and the gala are described as capable of appeasing deities, and especially Inanna, though I also think Westenholz was right to argue that a single shared function is not enough to warrant identification (Goddesses in Context…, p. 93-94). It’s also worth noting that similar abilities could be ascribed to multiple types of servant deities, and that Ninshubur was just the most popular member of this category - a veritable major minor deity, if you will - and as a result is much better represented in literary texts. But the likes of Ishum or Nuska appease their respective superiors too, and it’s hard to make a similar case for their gender.

It should also be noted that while Ninshubur ultimately is the main mourner in Inanna’s Descent, Lulal and Shara mourn too (whether equally intensely as Ninshubur is up for debate, but that’s beside the point); and Dumuzi is expected to, and dies precisely because he doesn’t. And the gender of none of these three is ever ambivalent. Furthermore, Gabbay’s argument about Ninshubur’s gender resembling the gala in part rests on treating a single unique source as perhaps more important than in reality - and it’s not necessarily a source relevant to the gala at all. There is only one source where Ninshubur's gender might be intentionally ambiguous. An Old Babylonian hymn describes Ninshubur as a figure dressed in masculine clothing on the right side and feminine on the left (Nin-šubur, p. 491). This does mirror the description of an unspecified type of cultic performer of unspecified gender mentioned in the famous Iddin-Dagan hymn (“Dressed with men's clothing on the right side (...) Adorned (?) with women's clothing on the left side”); however, there’s no indication that a gala is meant in this context. Gabbay doesn’t bring up this passage, and assumes that since Ninshubur’s clothing includes both masculine and feminine elements, it is automatically a situation analogous to the unclear gender identity of the gala (The Akkadian Word…, p. 54), though. It might be worth noting that the unique text still uses the feminine emesal form of Ninshubur’s name, Gashanshubur, with no masculine Umunshubur anywhere in sight (Åke W. Sjöberg, Miscellaneous Sumerian Texts, III, p. 72); as far as grammar is concerned, Ninshubur, even if dressed partially masculinely, remains feminine. Perhaps the context is just unclear for us, and the unusual outfit was tied to a specific performance as opposed to a specific gender identity, let alone specifically to ambiguity of gender? Perhaps it would make more sense to assume the text describes Ninshubur (partially) crossdressing (and we do have clear evidence for at least one festival which involved crossdressing from the Old Babylonian period), instead of dealing with gender identity? This is of course entirely speculative, though I think further inquiries are warranted. It’s also important to stress that however we interpret the identity of the gala - gender nonconforming men, men with some specific uncommon physical feature, nonbinary people (all three have valid arguments behind them, and it’s also not impossible the exact meaning varied across time and space) - they pretty clearly did not alternate between a firmly feminine identity and a firmly masculine one. Even if we were to incorrectly treat Ninshubur as a single deity whose gender alternates between male and female, I don’t think there would be a strong reason to draw parallels - unless you want to lump together what might very well been a specific nonbinary identity, and an instance of genderfluidity involving two firmly binary genders. I don’t really think these are phenomena which can be lumped together; and neither necessarily has much to do with presentation. And all we ultimately have in Ninshubur’s case is an isolated case of unusual presentation - nothing more, nothing less.

Once again, this short article is not intended as a warning against using Shehata’s book - it’s very rigorous overall, and a treasure trove of interesting information. It’s also not supposed to discredit Gabbay’s studies of the gala - I don’t necessarily fully agree with his conclusions, but I’ve depended on his articles in the past myself, after all.

The article also isn’t intended as an argument against inquiries into the gender of deities, Ninshubur included, or the gala, or any other religious specialists whose gender is unclear. However, it is vital to approach the evidence rigorously and put it into a broader context.

This is particularly significant since the gender of deities is not necessarily fully identical with the gender of humans, and its changes could be brought by processes which hardly have real life parallels - this requires both additional caution, and a careful case by case approach. It would be difficult for a woman to be conflated into one being with two men in the same profession, which is essentially what happened to Ninshubur, just like it would be hard for someone’s gender to be defined by the fact they were viewed as the personification of a specific astral body, as in the case of Ninsianna and Pinikir, who I discussed previously. And, of course, these two cases have little in common with each other. In the final article in this mini-series, I will look into some yet more esoteric cases of shifts in gender of Mesopotamian deities, to hopefully strengthen my point.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

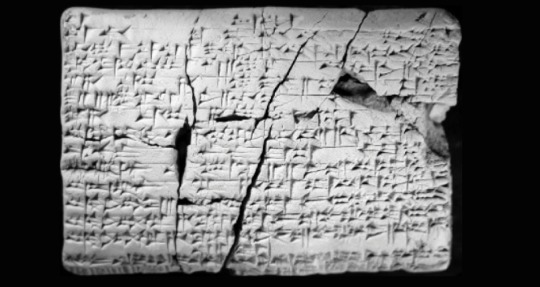

TAVOLETTE IN CUNEIFORME MOSTRANO I PRIMI ELEMENTI DELLA LINGUA AMORREA

TAVOLETTE IN CUNEIFORME MOSTRANO I PRIMI ELEMENTI DELLA LINGUA AMORREA Un team di assiriologi, gli studiosi della storia, dell'archeologia e della lingua dell'antica Mesopotamia, nella faticosa ricerca di decifrare tavolette cuneiformi relative a idiomi comel'accadico, il sumero, l'elamita, l'aramaico e l'ugaritico, hanno recentemente effettuato una grandiosa scoperta. Nathan Wasserman, docente presso l'Istituto di Archeologia dell'Hebrew University e del Dipartimento di Antiche civiltà del Vicino Oriente, coadiuvato da Yoram Cohen del Dipartimento di Archeologia dell'Università di Tel Aviv, hanno scoperto quello che definiscono un "cambiamento di paradigma" di importanza fondamentale nello studio della

Un team di assiriologi, gli studiosi della storia, dell’archeologia e della lingua dell’antica Mesopotamia, nella faticosa ricerca di decifrare tavolette cuneiformi relative a idiomi comel’accadico, il sumero, l’elamita, l’aramaico e l’ugaritico, hanno recentemente effettuato una grandiosa scoperta. Nathan Wasserman, docente presso l’Istituto di Archeologia dell’Hebrew University e del…

View On WordPress

#Amorrei#amorreo#Andrew George#Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Institute of Archaeology#Manfred Krebernik#Nathan Wasserman#tavolette cuneiformi#Università di Tel Aviv#Yoram Cohen

0 notes

Text

Bestseller in Archäologie #10: Götter und Mythen des Alt... von Manfred Krebernik https://t.co/o6BVhcU3yT #Kindle… https://t.co/KM9lEw8cL1

Bestseller in Archäologie #10: Götter und Mythen des Alt... von Manfred Krebernik https://t.co/o6BVhcU3yT #Kindle #Archäologie pic.twitter.com/KnEjXGXVDn

— KdlAzDE.bot (@KdlAzDE) October 30, 2017

via Twitter https://twitter.com/KdlAzDE October 30, 2017 at 02:30PM

0 notes

Note

Is there more information about Melam, besides 'the substance that covered the gods in terrifying splendor,' which makes humans experience 'the physical creeping of the flesh'?

You’re citing a subpar wikipedia article like it’s a primary source. Please don’t do that in my ask box.

Melam(mu) is an ordinary word referring to the abstract notion of radiance of deities (as well as certain other supernatural entities, most famously Humbaba; rulers; places and objects regarded as numinous, like temples, statues and cultic paraphernalia; and so on). Since terms like melam(mu) and puluḫtu have a more specific meaning than the generic namru, “shining”, more poetic translations like “awe-inspiring radiance” are fairly common. For more context see Radiant Things for Gods and Men: Lightness and Darkness in Mesopotamian Language and Thought by Shiyanthi Thavapalan (esp. p. 14-15). A deity could be described as possessing a plurality of melam, though this is generally rare (most famously, Humbaba has seven, but there are isolated attestations available for Nergal and Marduk too) and the term is typically left singular.

In textual sources melam is already attested in the Early Dynastic period (see the Reallexikon entry by Manfred Krebernik for a list of attestations), but in visual arts it only shows up in a coherent, consistent way in the Neo-Assyrian period, where deities are often surrounded by a so-called “nimbus” (The Melammu as Divine Epiphany and Usurped Entity by Mehmet-Ali Ataç, p. 295). Literary texts can present melam as something tangible - a divine garment, crown, wig and so on (for some examples see A New Occurrence of the Seven Aurae in a Sumerian Literary Passage Featuring Nergal by Jeremiah Peterson) - or even as logs of wood (in the Humbaba narrative; see The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts by Andrew R. George, p. 10). However, this holds true for many abstract concepts.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I don't know where else to go with this. My ability to find scholarly search results has atrophied. I'm looking for information on Napir, or Napiri, as far as I've seen. Supposedly an Elamite moon god, but I've noticed a great deal of mis-attribution with Elamite deities. The name simply being a god word doesn't help

Never seen the form "Napiri". If you mean Napirisha that's a completely unrelated deity. You will not find much solid on this matter because the Elamite moon deity's name was always written with the Akkadian logogram for the number 30 and the reading Napir relies entirely on the assumptions of Hinz and Koch and... neither of them was exactly rigorous. The only possible phonetic spelling in an actual primary source according to Manfred Krebernik seems to be Nanna or Nannar (p. 364 here) which imo fits pretty well with what we know about the pantheon of Susa and its surroundings, ie. that it was pretty much about as culturally (southern) Mesopotamian as the local pantheon of Mari. Elam obviously does not end there and one cannot rule out there was more than one lunar deity even in a specific area, obviously. I will note that it does seem there WAS an Elamite deity actually named Napir, as such a figure does appear in an inscription of Hanni of Ayapir. The only thing it tells us about this figure is that they were sipakirra, which is a term of still unknown meaning as per Wouther Henkelman, Other Gods Who Are, p. 356; long ago attempt has been made to prove it means "shining" but afaik it did not really catch on. Some sort of clergy of Napir is mentioned in a text from the reign of Tepti-Huban-Inshushinak (same book, p. 362).

The most recent instance of a publication where Napir is explicitly referred to as a moon deity I found isEnrique Qitana's chapter in The Elamite World but it does not really seem to be up to date, seeing how ex. he presents alleged spousal relations between deities as fact while more cautious authors like Wouter Henkelman note that in many cases even the gender of deities like Ruhurater is not actually known, let alone their relations to others. Tl;dr you're not finding much because there simply isn't much.

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

What were the roles and genealogy of Ninhursag?

Placed under the cut due to length. If not stated otherwise, the source is the book Goddesses in Context, linked pretty early on.

Starting with genealogy, because it's more straightforward. According to Manfred Krebernik, no explicit references to Ninhursag's parentage are known, and implicit evidence is largely provided just by statements about her being a sister of Enlil (source). Note that in Enlil and Sud, Enlil's sister is instead named Aruru, who was initially a separate goddess, associated only with vegetation. Since as far as I can tell no explicit references to Ninhursag being Enlil’s sister occur in most texts focused on Enlil’s own genealogy, I can’t really tell you if it means all the Lugaldukugas and Ninkis and Enmesharras commonly populating his family tree were also believed to function as Ninhursag’s ancestors. Or ancestors of his other sisters like Ningirima, for that matter. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a direct reference to Anu being her father. Krebernik also speculates that she might have been treated as a cosmogonic deity (ie. involved in the early history of the universe) which, I presume, would imply no real genealogy.

As a side note, Ninhursag’s relation with Enlil actually varies between sources, and in Lagash they were envisioned as a couple, though fwiw it was not really considered significant in Nippur (Enlilville) or Kesh (Ninhursagville) from what I’ve been able to gather, and Ninhursag appears there alongside Shulpa’e, her stock husband, instead. Rather elusive deity, but you can read a bit about him here.

Ninhursag's primary role is creation/birth; note that while commonly employed, the term "mother goddess" is not fully adequate because Mesopotamian goddesses who performed such a function only made living beings, they did not nurture them, and the process could be compared to crafting statues at times (also note craftsman deities like Ninmug appear in the entourage of “birth goddesses”). As always, I direct everyone to Goddesses in Context for relevant info. Note that Westenholz points out that it is possible that Ninhursag was initially responsible for nurturing rather than birth, though, since kings of Lagash and Kish seemed to present her as such.

Ninhursag’s other role is self-explanatory - her name means “mistress of the mountain ranges.” This might be tied to her possible cosmogonic role. Via merges with other similar goddesses she also came to be viewed as the creator in mankind, as in a Neo-Babylonian inscription, where she is “ exalted ruler, creatress of mankind, queen of the great mountains.”

A role Ninhursag at first seemingly did NOT hold was that of a city goddess of a major settlement - most of her cult centers were, according to Westenholz, “suburban towns and villages.” After the Sargonic period, she also “moved in” with her son Ashgi in Adab and, to put it colloquially, kicked him out of his city god position there. She also eventually displaced/absorbed the tutelary goddess of Kesh, Nintur. Some info on her early cult centers can be found here but it’s all in german.

Ninhursag also held the generic position of one of the “great gods,” though the common claim she was universally the #4 of the pantheon is not entirely correct. Also - note that when she is referred as “mother” this might be reference to this position of authority rather than to any association with children. As summed up in Goddesses in Context linked above: “nineteenth-century gender ideology that could not imagine motherhood other than in terms of an immanent feminine quality rooted in biology, contrasting with a universal, transcendental masculine divinity.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there a default version of Dumuzid's parents?

Well, there is a default version of his mother, at least: almost always the otherwise irrelevant goddess Duttur/Durtur/Turtur (outdated reading disproved based on phonetic Akkadian spelling: Sirtur) is cast in this role. She is very sparsely attested aside from appearing in compositions where she mourns Dumuzi. The available information has been gathered here by Manfred Krebernik (only in German, sadly). She might have been associated with sheep but this notion is disputed. Her other role is obviously that of a lamenting mother, and in that department only Ninisina gives her a run for her money (though Ninsina obviously is chiefly known from other contexts). An alternate tradition places Ninsun (yeah, that Ninsun) in the role of Dumuzi's mother, according to Dina Katz possibly because king lists, which record the order Lugalbanda -> Dumuzi the Fisherman -> Gilgamesh, lead to the conclusion Dumuzi must be a son of Lugalbanda and his wife and then the Dumuzis got confused. According to Wilfred G. Lambert there is an Old Babylonian incantation which labels Ea/Enki as Dumuzi's father but iirc according to Bendt Alster in the "classic" Dumuzi family tree as represented in myths as laments his father plays no role. The -other- other Dumuzi, Dumuzi-abzu (the female Dumuzi), had no genealogy initially afaik, but the late male variant from An = Anum is also a son of Ea though this was a secondary development likely postdating the relevance of Dumuzi-abzu as a deity.

4 notes

·

View notes