#Louis Prang

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Woman with Lily, ca. 1861–1897

Louis Prang

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis Prang - L'amour et Psyché (1887)

#art#painting#peinture#louis prang#american art#19th century#love#nature#cupid#psyche#mythologie#roman mythology

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

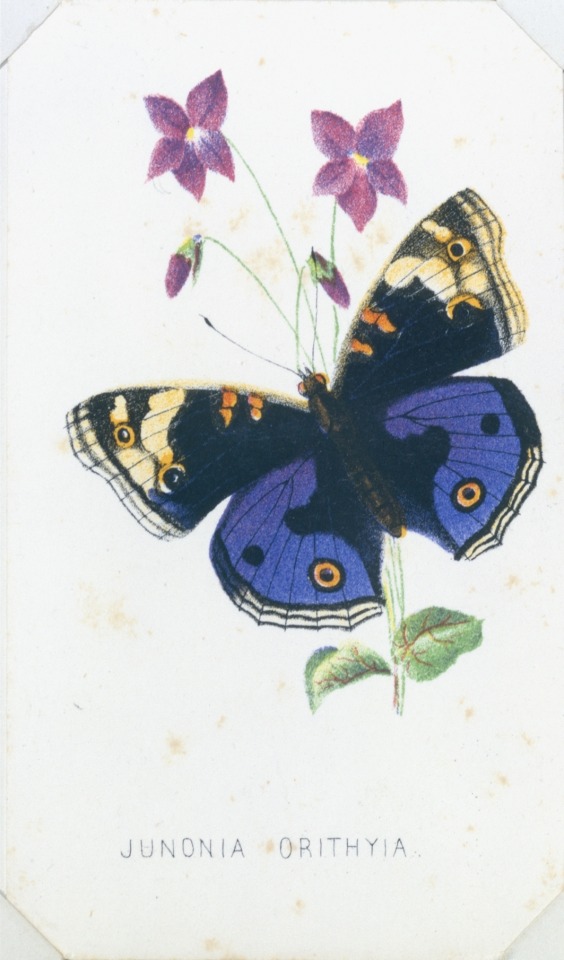

Junonia Orithyia from The Butterflies and Moths of America Part 1, Louis Prang & Co., 1860

Lithograph 4 ⅛ x 2 ⅜ in. (10.4 x 6.1 cm)

40 notes

·

View notes

Video

Spaniel and Woodcock by Boston Public Library Via Flickr: File name: 07_11_000779 Title: Spaniel and Woodcock Creator/Contributor: Tait, Arthur Fitzwilliam, 1819-1905 (artist); L. Prang & Co. (publisher) Date issued: 1861-1897 (approximate) Copyright date: Physical description note: Genre: Chromolithographs Location: Boston Public Library, Print Department Rights: No known restrictions

0 notes

Photo

The first mass-produced book to deviate from a rectilinear format, at least in the United States, is thought to be this beautiful 1863 edition of Red Riding Hood, published by Boston-based publisher Louis Prang. Leaf through its person-shaped pages here: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/the-first-shape-book-little-red-riding-hood-1863

216 notes

·

View notes

Text

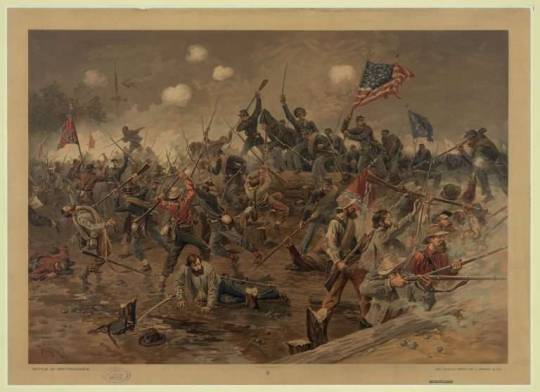

Crowd Scenes . 04 November 2024 . Battle of Spotsylvania Court House . Thure de Thulstrup 1887

Credit: Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division Original Author: Thure de Thulstrup, artist; L. Prang & Co., publisher Created: 1887 Medium: Chromolithograph Publisher: Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

An 1887 chromolithograph by well-known contemporary illustrator Thure de Thulstrup depicts a bayonet charge by Union forces during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. That bloody battle took place in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, over the course of nearly two weeks in May 1864, and resulted in more than 18,000 dead, wounded, captured, or missing Union soldiers, and more than 12,000 casualties on the Confederate side. During the fighting, a young West Point–educated Union colonel named Emory Upton concluded that attacking the Confederates' well-constructed earth-and-log works required a new mode of attack. Rather than advancing in long lines of infantry that halted in the open in order to exchange fire with a well-protected enemy behind earthworks, Upton argued for storming columns that never stopped to open fire, but instead advanced right up to the earthworks, engaging the enemy with the bayonet. He tested his new tactics as part of an all-out attack on the evening of May 10; its initial success impressed the Union commander Ulysses S. Grant, who duplicated the maneuver on a larger scale.

Thulstrip was a Swedish-born artist and magazine illustrator who specialized in military scenes. The print was published by L. Prang and Company in Boston, Massachusetts, a firm known for producing scenes from the Civil War, and for pioneering the sale of Christmas cards in the United States. The owner of the company, Louis Prang—a native of Prussia who emigrated to Boston in 1850–-has been referred to as the "father of the American Christmas card."

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas words: Christmas card

At Christmas time, it always felt like every surface of my grandparents house was covered in Christmas cards. Cards from family and friends and from all corners of the world. My grandfather enjoyed writing and sending many cards, as well as receiving many in return.

I really love the tradition of Christmas cards, although I only have the enthusiasm to send them to close family and friends. It's one of the few times of the year I still take the time to make use of the postal service for social correspondence.

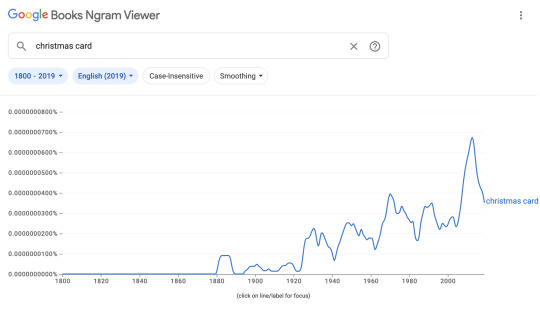

Like many things I think of as canonically Christmas, seasonal greetings cards are only a tradition from the last couple of centuries. The earliest citation in the Oxford English Dictionary for Christmas cards is from 1860. You can also see from Google ngrams viewer (screenshot below) that the phrase 'Christmas card' took a while to pick up in written English.

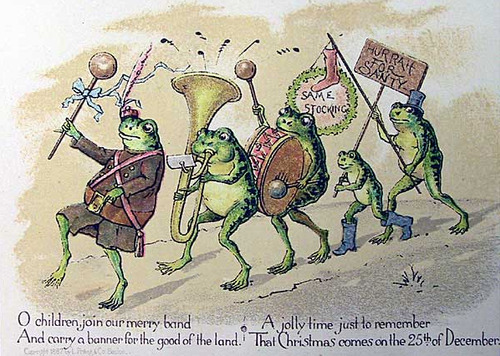

Christmas cards are such a wonderful reflection of the aesthetic, concerns and sometimes the sense of humour of a particular era. There's a great range of Christmas cards on the relevant Wikipedia page, including these charming marching frogs.

Christmas card by Louis Prang, showing a group of anthropomorphized frogs parading with banner and band. Via Wikipedia.

At Superlinguo, I celebrate the silly season with Christmasy words. The full list is here. If you’ve got a Christmas word you’re curious about, let me know!

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

This set of portfolios entitled “Oriental Ceramic Art, illustrated by Examples from the Collection of W.T. Walters” contains one hundred and sixteen gorgeous chromolithograph plates created by Louis Prang. Prang (1824-1909) was a German immigrant who ran a highly successful printing firm in Boston during the late nineteenth century.

The publication features objects from the collection of successful businessman and art collector William Thompson Walters (1820-1894), which later formed the basis of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, MD.

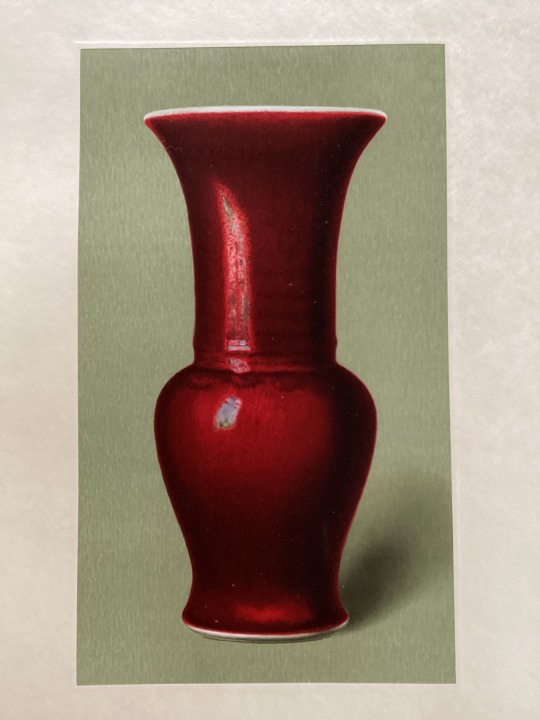

Each plate in the portfolios is accompanied by guard sheet with descriptive letterpress. In this post, we show you Plate 1 from Volume I with the guard sheet as well as the beautiful illustration of a porcelain vase underneath. Sang-de-boeuf is a deep red colored glaze that first appeared in Chinese porcelain at the start of the 18th century. The term is French, meaning “ox blood.”

Plate 1. Lang Yao Beaker. Beaker-shaped vase (Hua Ku), 16” high, enameled with the crackled glaze of the sang-de-boeuf mottled tints of the celebrated Lang Yao. The interior is coated with the same rich red glaze.

Oriental ceramic art : illustrated by examples from the collection of W. T. Walters : with one hundred and sixteen plates in colors and over four hundred reproductions in black and white Author / Creator: Bushell, Stephen W. (Stephen Wootton), 1844-1908. New York : D. Appleton, 1897. 10 v. in portfolios (v, 429 p., 96 col. leaves of plates) English HOLLIS number: 990041622660203941

#OrientalCeramicArt#Ceramic#Porcelain#SangDeBoeufGlaze#ChineseCeramic#ChinesePorcelain#LangYaoBeaker#SpecialCollection#ChineseArt#HarvardFineArtsLibrary#Fineartslibrary#Harvard#HarvardLibrary

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosina Emmet Sherwood (13 Dec 1854 – 19 Jan 1948) was an American painter.

Sherwood may have received her earliest training in art from her mother; #JuliaPiersonEmmet | Julia Colt Pierson Emmet (1829 – Sep 26, 1908) who was an American illustrator and painter. A sketchbook dating to 1873 was in the hands of family members in 1987.

Rosina traveled to Europe in 1876–1877, and was presented to Queen Victoria during the trip. Returning to New York, she and her friend #DoraWheeler began study art, and by 1881 she took studio space in the Tenth Street Studio Building.

Among her earliest works were illustrations for publications such as Harper's Magazine, and in 1880 she won the $1,000 first prize in a competition to design a Christmas card for Louis Prang & Company.

Sherwood and Wheeler worked together in the design firm Associated Artists, run by #CandaceWheeler, Dora's mother; they designed tapestries, curtains, and wallpaper. Subjects included a variety drawn from American literature. In 1884–1885 the women attended classes at the Académie Julian in Paris. Source and more Wikipedia

1. Cecilia Beaux by Rosina Emmet Sherwood, 1892

2. Forsyth Park

3. The Black Cuchrade, 1892

Pastel on paper board, 14" x 13"

#RosinaSherwood #RosinaEmmet #palianshow #art #artbywomen #RosinaSherwoodEmmet #Americanpainter

#Rosina Sherwood#Rosina Emmet#Rosina Emmet Sherwood#Julia Pierson Emmet#Dora Wheeler#Candace Wheeler#Cecilia Beaux#art by women#art herstory#women painters

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

El simbolismo de la Naturaleza: Mariposa

El significado de la mariposa varía de cultura a cultura, como sucede con la mayoría de los símbolos.

Generalmente, la mariposa es símbolo de transformación e inmortalidad, transmite la belleza que surge después de la muerte tras la aparente corrupción del cuerpo. Esto es debido a la metamorfosis que sufre para pasar de oruga a mariposa. Por esto es que es símbolo de renacimiento y resurrección.

En el mundo griego, la mariposa simboliza el alma; en China y en Japón es alegría e inmortalidad. En el arte chino, el significado de la mariposa puede cambiar según los elementos que le rodeen. Por ejemplo, en combinación con el ciruelo simboliza larga vida; dos mariposas juntas significan un matrimonio feliz.

Contrario a los significados que ya se han dado, en el arte cristiano la mariposa es ligereza e inconsistencia. Como está se precipita en el fuego atraída por la brillante luz emanada, muere rápidamente consumida. Así mismo sucede a los seres humanos que eligen la perdición por sobre el camino hacia Dios. Por supuesto que no por ello deja de relacionarse con la resurrección, pues surge de la crisálida y asciende a los cielos como lo hizo Cristo.

www.tarotdeana.tumblr.com

Lee mitos griegos aquí.

Lee mitos coreanos aquí.

Lee mitos japoneses aquí.

Imágenes:

"Butterflies Flying above Clouds", por Migishi Kotaro, 1934

"Naturaleza muerta con duraznos y mariposas", por Jan Mortel, 1683

"Actia Virgo de Mariposas y Polillas de América Pt. 5", por Louis Prang & Co, 1862

"Chica con mariposa", por Gh. Panaiteanu Bardarsare, 1816/1900

#símbolos#simbolismo#simbologia#symbolism#symbols#mariposa#butterfly#tarot#cartomancia#tarot reading#ocultismo#tarot cards#ocultista#witchcraft#brujería#artes ocultas#cosas de brujas#nature#art

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

It Can't Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis

Chapter 15-16

CHAPTER XV

USUALLY I'm pretty mild, in fact many of my friends are kind enough to call it "Folksy," when I'm writing or speechifying. My ambition is to "live by the side of the road and be a friend to man." But I hope that none of the gentlemen who have honored me with their enmity think for one single moment that when I run into a gross enough public evil or a persistent enough detractor, I can't get up on my hind legs and make a sound like a two-tailed grizzly in April. So right at the start of this account of my ten-year fight with them, as private citizen, State Senator, and U. S. Senator, let me say that the Sangfrey River Light, Power, and Fuel Corporation are—and I invite a suit for libel—the meanest, lowest, cowardliest gang of yellow-livered, back-slapping, hypocritical gun-toters, bomb-throwers, ballot-stealers, ledger-fakers, givers of bribes, suborners of perjury, scab-hirers, and general lowdown crooks, liars, and swindlers that ever tried to do an honest servant of the People out of an election—not but what I have always succeeded in licking them, so that my indignation at these homicidal kleptomaniacs is not personal but entirely on behalf of the general public.

Zero Hour, Berzelius Windrip

ON Wednesday, January 6, 1937, just a fortnight before his inauguration, President-Elect Windrip announced his appointments of cabinet members and of diplomats.

Secretary of State: his former secretary and press-agent, Lee Sarason, who also took the position of High Marshal, or Commander-in-Chief, of the Minute Men, which organization was to be established permanently, as an innocent marching club.

Secretary of the Treasury: one Webster R. Skittle, president of the prosperous Fur & Hide National Bank of St. Louis—Mr. Skittle had once been indicted on a charge of defrauding the government on his income tax, but he had been acquitted, more or less, and during the campaign, he was said to have taken a convincing way of showing his faith in Buzz Windrip as the Savior of the Forgotten Men.

Secretary of War: Colonel Osceola Luthorne, formerly editor of the Topeka (Kans.) Argus, and the Fancy Goods and Novelties Gazette; more recently high in real estate. His title came from his position on the honorary staff of the Governor of Tennessee. He had long been a friend and fellow campaigner of Windrip.

It was a universal regret that Bishop Paul Peter Prang should have refused the appointment as Secretary of War, with a letter in which he called Windrip "My dear Friend and Collaborator" and asserted that he had actually meant it when he had said he desired no office. Later, it was a similar regret when Father Coughlin refused the Ambassadorship to Mexico, with no letter at all but only a telegram cryptically stating, "Just six months too late."

A new cabinet position, that of Secretary of Education and Public Relations, was created. Not for months would Congress investigate the legality of such a creation, but meantime the new post was brilliantly held by Hector Macgoblin, M.D., Ph.D., Hon. Litt.D.

Senator Porkwood graced the position of Attorney General, and all the other offices were acceptably filled by men who, though they had roundly supported Windrip's almost socialistic projects for the distribution of excessive fortunes, were yet known to be thoroughly sensible men, and no fanatics.

It was said, though Doremus Jessup could never prove it, that Windrip learned from Lee Sarason the Spanish custom of getting rid of embarrassing friends and enemies by appointing them to posts abroad, preferably quite far abroad. Anyway, as Ambassador to Brazil, Windrip appointed Herbert Hoover, who not very enthusiastically accepted; as Ambassador to Germany, Senator Borah; as Governor of the Philippines, Senator Robert La Follette, who refused; and as Ambassadors to the Court of St. James's, France, and Russia, none other than Upton Sinclair, Milo Reno, and Senator Bilbo of Mississippi.

These three had a fine time. Mr. Sinclair pleased the British by taking so friendly an interest in their politics that he openly campaigned for the Independent Labor Party and issued a lively brochure called "I, Upton Sinclair, Prove That Prime-Minister Walter Elliot, Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden, and First Lord of the Admiralty Nancy Astor Are All Liars and Have Refused to Accept My Freely Offered Advice." Mr. Sinclair also aroused considerable interest in British domestic circles by advocating an act of Parliament forbidding the wearing of evening clothes and all hunting of foxes except with shotguns; and on the occasion of his official reception at Buckingham Palace, he warmly invited King George and Queen Mary to come and live in California.

Mr. Milo Reno, insurance salesman and former president of the National Farm Holiday Association, whom all the French royalists compared to his great predecessor, Benjamin Franklin, for forthrightness, became the greatest social favorite in the international circles of Paris, the Basses-Pyrénées, and the Riviera, and was once photographed playing tennis at Antibes with the Duc de Tropez, Lord Rothermere, and Dr. Rudolph Hess.

Senator Bilbo had, possibly, the best time of all.

Stalin asked his advice, as based on his ripe experience in the Gleichshaltung of Mississippi, about the cultural organization of the somewhat backward natives of Tadjikistan, and so valuable did it prove that Excellency Bilbo was invited to review the Moscow military celebration, the following November seventh, in the same stand with the very highest class of representatives of the classless state. It was a triumph for His Excellency. Generalissimo Voroshilov fainted after 200,000 Soviet troops, 7000 tanks, and 9000 aeroplanes had passed by; Stalin had to be carried home after reviewing 317,000; but Ambassador Bilbo was there in the stand when the very last of the 626,000 soldiers had gone by, all of them saluting him under the quite erroneous impression that he was the Chinese Ambassador; and he was still tirelessly returning their salutes, fourteen to the minute, and softly singing with them the "International."

He was less of a hit later, however, when to the unsmiling Anglo-American Association of Exiles to Soviet Russia from Imperialism, he sang to the tune of the "International" what he regarded as amusing private words of his own:

"Arise, ye prisoners of starvation, From Russia make your getaway. They all are rich in Bilbo's nation. God bless the U.S.A.!"

Mrs. Adelaide Tarr Gimmitch, after her spirited campaign for Mr. Windrip, was publicly angry that she was offered no position higher than a post in the customs office in Nome, Alaska, though this was offered to her very urgently indeed. She had demanded that there be created, especially for her, the cabinet position of Secretaryess of Domestic Science, Child Welfare, and Anti-Vice. She threatened to turn Jeffersonian, Republican, or Communistic, but in April she was heard of in Hollywood, writing the scenario for a giant picture to be called, They Did It in Greece.

As an insult and boy-from-home joke, the President-Elect appointed Franklin D. Roosevelt minister to Liberia. Mr. Roosevelt's opponents laughed very much, and opposition newspapers did cartoons of him sitting unhappily in a grass hut with a sign on which "N.R.A." had been crossed out and "U.S.A." substituted. But Mr. Roosevelt declined with so amiable a smile that the joke seemed rather to have slipped.

The followers of President Windrip trumpeted that it was significant that he should be the first president inaugurated not on March fourth, but on January twentieth, according to the provision of the new Twentieth Amendment to the Constitution. It was a sign straight from Heaven (though, actually, Heaven had not been the author of the amendment, but Senator George W. Norris of Nebraska), and proved that Windrip was starting a new paradise on earth.

The inauguration was turbulent. President Roosevelt declined to be present—he politely suggested that he was about half ill unto death, but that same noon he was seen in a New York shop, buying books on gardening and looking abnormally cheerful.

More than a thousand reporters, photographers, and radio men covered the inauguration. Twenty-seven constituents of Senator Porkwood, of all sexes, had to sleep on the floor of the Senator's office, and a hall-bedroom in the suburb of Bladensburg rented for thirty dollars for two nights. The presidents of Brazil, the Argentine, and Chile flew to the inauguration in a Pan-American aeroplane, and Japan sent seven hundred students on a special train from Seattle.

A motor company in Detroit had presented to Windrip a limousine with armor plate, bulletproof glass, a hidden nickel-steel safe for papers, a concealed private bar, and upholstery made from the Troissant tapestries of 1670. But Buzz chose to drive from his home to the Capitol in his old Hupmobile sedan, and his driver was a youngster from his home town whose notion of a uniform for state occasions was a blue-serge suit, red tie, and derby hat. Windrip himself did wear a topper, but he saw to it that Lee Sarason saw to it that the one hundred and thirty million plain citizens learned, by radio, even while the inaugural parade was going on, that he had borrowed the topper for this one sole occasion from a New York Republican Representative who had ancestors.

But following Windrip was an un-Jacksonian escort of soldiers: the American Legion and, immensely grander than the others, the Minute Men, wearing trench helmets of polished silver and led by Colonel Dewey Haik in scarlet tunic and yellow riding-breeches and helmet with golden plumes.

Solemnly, for once looking a little awed, a little like a small-town boy on Broadway, Windrip took the oath, administered by the Chief Justice (who disliked him very much indeed) and, edging even closer to the microphone, squawked, "My fellow citizens, as the President of the United States of America, I want to inform you that the real New Deal has started right this minute, and we're all going to enjoy the manifold liberties to which our history entitles us—and have a whale of a good time doing it! I thank you!"

That was his first act as President. His second was to take up residence in the White House, where he sat down in the East Room in his stocking feet and shouted at Lee Sarason, "This is what I've been planning to do now for six years! I bet this is what Lincoln used to do! Now let 'em assassinate me!"

His third, in his role as Commander-in-Chief of the Army, was to order that the Minute Men be recognized as an unpaid but official auxiliary of the Regular Army, subject only to their own officers, to Buzz, and to High Marshal Sarason; and that rifles, bayonets, automatic pistols, and machine guns be instantly issued to them by government arsenals. That was at 4 P.M. Since 3 P.M., all over the country, bands of M.M.'s had been sitting gloating over pistols and guns, twitching with desire to seize them.

Fourth coup was a special message, next morning, to Congress (in session since January fourth, the third having been a Sunday), demanding the instant passage of a bill embodying Point Fifteen of his election platform—that he should have complete control of legislation and execution, and the Supreme Court be rendered incapable of blocking anything that it might amuse him to do.

By Joint Resolution, with less than half an hour of debate, both houses of Congress rejected that demand before 3 P.M., on January twenty-first. Before six, the President had proclaimed that a state of martial law existed during the "present crisis," and more than a hundred Congressmen had been arrested by Minute Men, on direct orders from the President. The Congressmen who were hotheaded enough to resist were cynically charged with "inciting to riot"; they who went quietly were not charged at all. It was blandly explained to the agitated press by Lee Sarason that these latter quiet lads had been so threatened by "irresponsible and seditious elements" that they were merely being safeguarded. Sarason did not use the phrase "protective arrest," which might have suggested things.

To the veteran reporters it was strange to see the titular Secretary of State, theoretically a person of such dignity and consequence that he could deal with the representatives of foreign powers, acting as press-agent and yes-man for even the President.

There were riots, instantly, all over Washington, all over America.

The recalcitrant Congressmen had been penned in the District Jail. Toward it, in the winter evening, marched a mob that was noisily mutinous toward the Windrip for whom so many of them had voted. Among the mob buzzed hundreds of Negroes, armed with knives and old pistols, for one of the kidnaped Congressmen was a Negro from Georgia, the first colored Georgian to hold high office since carpetbagger days.

Surrounding the jail, behind machine guns, the rebels found a few Regulars, many police, and a horde of Minute Men, but at these last they jeered, calling them "Minnie Mouses" and "tin soldiers" and "mama's boys." The M.M.'s looked nervously at their officers and at the Regulars who were making so professional a pretense of not being scared. The mob heaved bottles and dead fish. Half-a-dozen policemen with guns and night sticks, trying to push back the van of the mob, were buried under a human surf and came up grotesquely battered and ununiformed—those who ever did come up again. There were two shots; and one Minute Man slumped to the jail steps, another stood ludicrously holding a wrist that spurted blood.

The Minute Men—why, they said to themselves, they'd never meant to be soldiers anyway—just wanted to have some fun marching! They began to sneak into the edges of the mob, hiding their uniform caps. That instant, from a powerful loudspeaker in a lower window of the jail brayed the voice of President Berzelius Windrip:

"I am addressing my own boys, the Minute Men, everywhere in America! To you and you only I look for help to make America a proud, rich land again. You have been scorned. They thought you were the 'lower classes.' They wouldn't give you jobs. They told you to sneak off like bums and get relief. They ordered you into lousy C.C.C. camps. They said you were no good, because you were poor. I tell you that you are, ever since yesterday noon, the highest lords of the land—the aristocracy—the makers of the new America of freedom and justice. Boys! I need you! Help me—help me to help you! Stand fast! Anybody tries to block you—give the swine the point of your bayonet!"

A machine-gunner M.M., who had listened reverently, let loose. The mob began to drop, and into the backs of the wounded as they went staggering away the M.M. infantry, running, poked their bayonets. Such a juicy squash it made, and the fugitives looked so amazed, so funny, as they tumbled in grotesque heaps!

The M.M.'s hadn't, in dreary hours of bayonet drill, known this would be such sport. They'd have more of it now—and hadn't the President of the United States himself told each of them, personally, that he needed their aid?

When the remnants of Congress ventured to the Capitol, they found it seeded with M.M.'s, while a regiment of Regulars, under Major General Meinecke, paraded the grounds.

The Speaker of the House, and the Hon. Mr. Perley Beecroft, Vice- President of the United States and Presiding Officer of the Senate, had the power to declare that quorums were present. (If a lot of members chose to dally in the district jail, enjoying themselves instead of attending Congress, whose fault was that?) Both houses passed a resolution declaring Point Fifteen temporarily in effect, during the "crisis"—the legality of the passage was doubtful, but just who was to contest it, even though the members of the Supreme Court had not been placed under protective arrest... merely confined each to his own house by a squad of Minute Men!

Bishop Paul Peter Prang had (his friends said afterward) been dismayed by Windrip's stroke of state. Surely, he complained, Mr. Windrip hadn't quite remembered to include Christian Amity in the program he had taken from the League of Forgotten Men. Though Mr. Prang had contentedly given up broadcasting ever since the victory of Justice and Fraternity in the person of Berzelius Windrip, he wanted to caution the public again, but when he telephoned to his familiar station, WLFM in Chicago, the manager informed him that "just temporarily, all access to the air was forbidden," except as it was especially licensed by the offices of Lee Sarason. (Oh, that was only one of sixteen jobs that Lee and his six hundred new assistants had taken on in the past week.)

Rather timorously, Bishop Prang motored from his home in Persepolis, Indiana, to the Indianapolis airport and took a night plane for Washington, to reprove, perhaps even playfully to spank, his naughty disciple, Buzz.

He had little trouble in being admitted to see the President. In fact, he was, the press feverishly reported, at the White House for six hours, though whether he was with the President all that time they could not discover. At three in the afternoon Prang was seen to leave by a private entrance to the executive offices and take a taxi. They noted that he was pale and staggering.

In front of his hotel he was elbowed by a mob who in curiously unmenacing and mechanical tones yelped, "Lynch um—downutha enemies Windrip!" A dozen M.M.'s pierced the crowd and surrounded the Bishop. The Ensign commanding them bellowed to the crowd, so that all might hear, "You cowards leave the Bishop alone! Bishop, come with us, and we'll see you're safe!"

Millions heard on their radios that evening the official announcement that, to ward off mysterious plotters, probably Bolsheviks, Bishop Prang had been safely shielded in the district jail. And with it a personal statement from President Windrip that he was filled with joy at having been able to "rescue from the foul agitators my friend and mentor, Bishop P. P. Prang, than whom there is no man living who I so admire and respect."

There was, as yet, no absolute censorship of the press; only a confused imprisonment of journalists who offended the government or local officers of the M.M.'s; and the papers chronically opposed to Windrip carried by no means flattering hints that Bishop Prang had rebuked the President and been plain jailed, with no nonsense about a "rescue." These mutters reached Persepolis.

Not all the Persepolitans ached with love for the Bishop or considered him a modern St. Francis gathering up the little fowls of the fields in his handsome LaSalle car. There were neighbors who hinted that he was a window-peeping snooper after bootleggers and obliging grass widows. But proud of him, their best advertisement, they certainly were, and the Persepolis Chamber of Commerce had caused to be erected at the Eastern gateway to Main Street the sign: "Home of Bishop Prang, Radio's Greatest Star."

So as one man Persepolis telegraphed to Washington, demanding Prang's release, but a messenger in the Executive Offices who was a Persepolis boy (he was, it is true, a colored man, but suddenly he became a favorite son, lovingly remembered by old schoolmates) tipped off the Mayor that the telegrams were among the hundredweight of messages that were daily hauled away from the White House unanswered.

Then a quarter of the citizenry of Persepolis mounted a special train to "march" on Washington. It was one of those small incidents which the opposition press could use as a bomb under Windrip, and the train was accompanied by a score of high-ranking reporters from Chicago and, later, from Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and New York.

While the train was on its way—and it was curious what delays and sidetrackings it encountered—a company of Minute Men at Logansport, Indiana, rebelled against having to arrest a group of Catholic nuns who were accused of having taught treasonably. High Marshal Sarason felt that there must be a Lesson, early and impressive. A battalion of M.M.'s, sent from Chicago in fast trucks, arrested the mutinous company, and shot every third man.

When the Persepolitans reached Washington, they were tearfully informed, by a brigadier of M.M.'s who met them at the Union Station, that poor Bishop Prang had been so shocked by the treason of his fellow Indianans that he had gone melancholy mad and they had tragically been compelled to shut him up in St. Elizabeth's government insane asylum.

No one willing to carry news about him ever saw Bishop Prang again.

The Brigadier brought greetings to the Persepolitans from the President himself, and an invitation to stay at the Willard, at government expense. Only a dozen accepted; the rest took the first train back, not amiably; and from then on there was one town in America in which no M.M. ever dared to appear in his ducky forage cap and dark-blue tunic.

The Chief of Staff of the Regular Army had been deposed; in his place was Major General Emmanuel Coon. Doremus and his like were disappointed by General Coon's acceptance, for they had always been informed, even by the Nation, that Emmanuel Coon, though a professional army officer who did enjoy a fight, preferred that that fight be on the side of the Lord; that he was generous, literate, just, and a man of honor—and honor was the one quality that Buzz Windrip wasn't even expected to understand. Rumor said that Coon (as "Nordic" a Kentuckian as ever existed, a descendant of men who had fought beside Kit Carson and Commodore Perry) was particularly impatient with the puerility of anti-Semitism, and that nothing so pleased him as, when he heard new acquaintances being superior about the Jews, to snarl, "Did you by any chance happen to notice that my name is Emmanuel Coon and that Coon might be a corruption of some name rather familiar on the East Side of New York?"

"Oh well, I suppose even General Coon feels, 'Orders are Orders,'" sighed Doremus.

President Windrip's first extended proclamation to the country was a pretty piece of literature and of tenderness. He explained that powerful and secret enemies of American principles—one rather gathered that they were a combination of Wall Street and Soviet Russia—upon discovering, to their fury, that he, Berzelius, was going to be President, had planned their last charge. Everything would be tranquil in a few months, but meantime there was a Crisis, during which the country must "bear with him."

He recalled the military dictatorship of Lincoln and Stanton during the Civil War, when civilian suspects were arrested without warrant. He hinted how delightful everything was going to be— right away now—just a moment—just a moment's patience—when he had things in hand; and he wound up with a comparison of the Crisis to the urgency of a fireman rescuing a pretty girl from a "conflagration," and carrying her down a ladder, for her own sake, whether she liked it or not, and no matter how appealingly she might kick her pretty ankles.

The whole country laughed.

"Great card, that Buzz, but mighty competent guy," said the electorate.

"I should worry whether Bish Prang or any other nut is in the boobyhatch, long as I get my five thousand bucks a year, like Windrip promised," said Shad Ledue to Charley Betts, the furniture man.

It had all happened within the eight days following Windrip's inauguration.

CHAPTER XVI

I HAVE no desire to be President. I would much rather do my humble best as a supporter of Bishop Prang, Ted Bilbo, Gene Talmadge or any other broad-gauged but peppy Liberal. My only longing is to Serve.

Zero Hour, Berzelius Windrip.

LIKE many bachelors given to vigorous hunting and riding, Buck Titus was a fastidious housekeeper, and his mid-Victorian farmhouse fussily neat. It was also pleasantly bare: the living room a monastic hall of heavy oak chairs, tables free of dainty covers, numerous and rather solemn books of history and exploration, with the conventional "sets," and a tremendous fireplace of rough stone. And the ash trays were solid pottery and pewter, able to cope with a whole evening of cigarette-smoking. The whisky stood honestly on the oak buffet, with siphons, and with cracked ice always ready in a thermos jug.

It would, however, have been too much to expect Buck Titus not to have red-and-black imitation English hunting-prints.

This hermitage, always grateful to Doremus, was sanctuary now, and only with Buck could he adequately damn Windrip & Co. and people like Francis Tasbrough, who in February was still saying, "Yes, things do look kind of hectic down there in Washington, but that's just because there's so many of these bullheaded politicians that still think they can buck Windrip. Besides, anyway, things like that couldn't ever happen here in New England."

And, indeed, as Doremus went on his lawful occasions past the red-brick Georgian houses, the slender spires of old white churches facing the Green, as he heard the lazy irony of familiar greetings from his acquaintances, men as enduring as their Vermont hills, it seemed to him that the madness in the capital was as alien and distant and unimportant as an earthquake in Tibet.

Constantly, in the Informer, he criticized the government but not too acidly.

The hysteria can't last; be patient, and wait and see, he counseled his readers.

It was not that he was afraid of the authorities. He simply did not believe that this comic tyranny could endure. It can't happen here, said even Doremus—even now.

The one thing that most perplexed him was that there could be a dictator seemingly so different from the fervent Hitlers and gesticulating Fascists and the Cæsars with laurels round bald domes; a dictator with something of the earthy American sense of humor of a Mark Twain, a George Ade, a Will Rogers, an Artemus Ward. Windrip could be ever so funny about solemn jaw-drooping opponents, and about the best method of training what he called "a Siamese flea hound." Did that, puzzled Doremus, make him less or more dangerous?

Then he remembered the most cruel-mad of all pirates, Sir Henry Morgan, who had thought it ever so funny to sew a victim up in wet rawhide and watch it shrink in the sun.

From the perseverance with which they bickered, you could tell that Buck Titus and Lorinda were much fonder of each other than they would admit. Being a person who read little and therefore took what he did read seriously, Buck was distressed by the normally studious Lorinda's vacation liking for novels about distressed princesses, and when she airily insisted that they were better guides to conduct than Anthony Trollope or Thomas Hardy, Buck roared at her and, in the feebleness of baited strength, nervously filled pipes and knocked them out against the stone mantel. But he approved of the relationship between Doremus and Lorinda, which only he (and Shad Ledue!) had guessed, and over Doremus, ten years his senior, this shaggy-headed woodsman fussed like a thwarted spinster.

To both Doremus and Lorinda, Buck's overgrown shack became their refuge. And they needed it, late in February, five weeks or thereabouts after Windrip's election.

Despite strikes and riots all over the country, bloodily put down by the Minute Men, Windrip's power in Washington was maintained. The most liberal four members of the Supreme Court resigned and were replaced by surprisingly unknown lawyers who called President Windrip by his first name. A number of Congressmen were still being "protected" in the District of Columbia jail; others had seen the blinding light forever shed by the goddess Reason and happily returned to the Capitol. The Minute Men were increasingly loyal— they were still unpaid volunteers, but provided with "expense accounts" considerably larger than the pay of the regular troops. Never in American history had the adherents of a President been so well satisfied; they were not only appointed to whatever political jobs there were but to ever so many that really were not; and with such annoyances as Congressional Investigations hushed, the official awarders of contracts were on the merriest of terms with all contractors.... One veteran lobbyist for steel corporations complained that there was no more sport in his hunting—you were not only allowed but expected to shoot all government purchasing-agents sitting.

None of the changes was so publicized as the Presidential mandate abruptly ending the separate existence of the different states, and dividing the whole country into eight "provinces"—thus, asserted Windrip, economizing by reducing the number of governors and all other state officers and, asserted Windrip's enemies, better enabling him to concentrate his private army and hold the country.

The new "Northeastern Province" included all of New York State north of a line through Ossining, and all of New England except a strip of Connecticut shore as far east as New Haven. This was, Doremus admitted, a natural and homogeneous division, and even more natural seemed the urban and industrial "Metropolitan Province," which included Greater New York, Westchester County up to Ossining, Long Island, the strip of Connecticut dependent on New York City, New Jersey, northern Delaware, and Pennsylvania as far as Reading and Scranton.

Each province was divided into numbered districts, each district into lettered counties, each county into townships and cities, and only in these last did the old names, with their traditional appeal, remain to endanger President Windrip by memories of honorable local history. And it was gossiped that, next, the government would change even the town names—that they were already thinking fondly of calling New York "Berzelian" and San Francisco "San Sarason." Probably that gossip was false.

The Northeastern Province's six districts were: 1, Upper New York State west of and including Syracuse; 2, New York east of it; 3, Vermont and New Hampshire; 4, Maine; 5, Massachusetts; 6, Rhode Island and the unraped portion of Connecticut.

District 3, Doremus Jessup's district, was divided into the four "counties" of southern and northern Vermont, and southern and northern New Hampshire, with Hanover for capital—the District Commissioner merely chased the Dartmouth students out and took over the college buildings for his offices, to the considerable approval of Amherst, Williams, and Yale.

So Doremus was living, now, in Northeastern Province, District 3, County B, township of Beulah, and over him for his admiration and rejoicing were a provincial commissioner, a district commissioner, a county commissioner, an assistant county commissioner in charge of Beulah Township, and all their appertaining M.M. guards and emergency military judges.

Citizens who had lived in any one state for more than ten years seemed to resent more hotly the loss of that state's identity than they did the castration of the Congress and Supreme Court of the United States—indeed, they resented it almost as much as the fact that, while late January, February, and most of March went by, they still were not receiving their governmental gifts of $5000 (or perhaps it would beautifully be $10,000) apiece; had indeed received nothing more than cheery bulletins from Washington to the effect that the "Capital Levy Board," or C.L.B. was holding sessions.

Virginians whose grandfathers had fought beside Lee shouted that they'd be damned if they'd give up the hallowed state name and form just one arbitrary section of an administrative unit containing eleven Southern states; San Franciscans who had considered Los Angelinos even worse than denizens of Miami now wailed with agony when California was sundered and the northern portion lumped in with Oregon, Nevada, and others as the "Mountain and Pacific Province," while southern California was, without her permission, assigned to the Southwestern Province, along with Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Hawaii. As some hint of Buzz Windrip's vision for the future, it was interesting to read that this Southwestern Province was also to be permitted to claim "all portions of Mexico which the United States may from time to time find it necessary to take over, as a protection against the notorious treachery of Mexico and the Jewish plots there hatched."

"Lee Sarason is even more generous than Hitler and Alfred Rosenberg in protecting the future of other countries," sighed Doremus.

As Provincial Commissioner of the Northeastern Province, comprising Upper New York State and New England, was appointed Colonel Dewey Haik, that soldier-lawyer-politician-aviator who was the chilliest-blooded and most arrogant of all the satellites of Windrip yet had so captivated miners and fishermen during the campaign. He was a strong-flying eagle who liked his meat bloody. As District Commissioner of District 3—Vermont and New Hampshire—appeared, to Doremus's mingled derision and fury, none other than John Sullivan Reek, that stuffiest of stuffed-shirts, that most gaseous gas bag, that most amenable machine politician of Northern New England; a Republican ex-governor who had, in the alembic of Windrip's patriotism, rosily turned Leaguer.

No one had ever troubled to be obsequious to the Hon. J. S. Reek, even when he had been Governor. The weediest back-country Representative had called him "Johnny," in the gubernatorial mansion (twelve rooms and a leaky roof); and the youngest reporter had bawled, "Well, what bull you handing out today, Ex?"

It was this Commissioner Reek who summoned all the editors in his district to meet him at his new viceregal lodge in Dartmouth Library and receive the precious privileged information as to how much President Windrip and his subordinate commissioners admired the gentlemen of the press.

Before he left for the press conference in Hanover, Doremus received from Sissy a "poem"—at least she called it that—which Buck Titus, Lorinda Pike, Julian Falck, and she had painfully composed, late at night, in Buck's fortified manor house:

Be meek with Reek, Go fake with Haik. One rhymes with sneak, And t' other with snake. Haik, with his beak, Is on the make, But Sullivan Reek— Oh God!

"Well, anyway, Windrip's put everybody to work. And he's driven all these unsightly billboards off the highways—much better for the tourist trade," said all the old editors, even those who wondered if the President wasn't perhaps the least bit arbitrary.

As he drove to Hanover, Doremus saw hundreds of huge billboards by the road. But they bore only Windrip propaganda and underneath, "with the compliments of a loyal firm" and—very large—"Montgomery Cigarettes" or "Jonquil Foot Soap." On the short walk from a parking-space to the former Dartmouth campus, three several men muttered to him, "Give us a nickel for cuppa coffee, Boss—a Minnie Mouse has got my job and the Mouses won't take me—they say I'm too old." But that may have been propaganda from Moscow.

On the long porch of the Hanover Inn, officers of the Minute Men were reclining in deck chairs, their spurred boots (in all the M.M. organization there was no cavalry) up on the railing.

Doremus passed a science building in front of which was a pile of broken laboratory glassware, and in one stripped laboratory he could see a small squad of M.M.'s drilling.

District Commissioner John Sullivan Reek affectionately received the editors in a classroom.... Old men, used to being revered as prophets, sitting anxiously in trifling chairs, facing a fat man in the uniform of an M.M. commander, who smoked an unmilitary cigar as his pulpy hand waved greeting.

Reek took not more than an hour to relate what would have taken the most intelligent man five or six hours—that is, five minutes of speech and the rest of the five hours to recover from the nausea caused by having to utter such shameless rot.... President Windrip, Secretary of State Sarason, Provincial Commissioner Haik, and himself, John Sullivan Reek, they were all being misrepresented by the Republicans, the Jeffersonians, the Communists, England, the Nazis, and probably the jute and herring industries; and what the government wanted was for any reporter to call on any member of this Administration, and especially on Commissioner Reek, at any time—except perhaps between 3 and 7 A.M.—and "get the real low-down."

Excellency Reek announced, then: "And now, gentlemen, I am giving myself the privilege of introducing you to all four of the County Commissioners, who were just chosen yesterday. Probably each of you will know personally the commissioner from your own county, but I want you to intimately and cooperatively know all four, because, whomever they may be, they join with me in my unquenchable admiration of the press."

The four County Commissioners, as one by one they shambled into the room and were introduced, seemed to Doremus an oddish lot: A moth-eaten lawyer known more for his quotations from Shakespeare and Robert W. Service than for his shrewdness before a jury. He was luminously bald except for a prickle of faded rusty hair, but you felt that, if he had his rights, he would have the floating locks of a tragedian of 1890.

A battling clergyman famed for raiding roadhouses.

A rather shy workman, an authentic proletarian, who seemed surprised to find himself there. (He was replaced, a month later, by a popular osteopath with an interest in politics and vegetarianism.)

The fourth dignitary to come in and affectionately bow to the editors, a bulky man, formidable-looking in his uniform as a battalion leader of Minute Men, introduced as the Commissioner for northern Vermont, Doremus Jessup's county, was Mr. Oscar Ledue, formerly known as "Shad."

Mr. Reek called him "Captain" Ledue. Doremus remembered that Shad's only military service, prior to Windrip's election, had been as an A.E.F. private who had never got beyond a training-camp in America and whose fiercest experience in battle had been licking a corporal when in liquor.

"Mr. Jessup," bubbled the Hon. Mr. Reek, "I imagine you must have met Captain Ledue—comes from your charming city."

"Uh-uh-ur," said Doremus.

"Sure," said Captain Ledue. "I've met old Jessup, all right, all right! He don't know what it's all about. He don't know the first thing about the economics of our social Revolution. He's a Cho-vinis. But he isn't such a bad old coot, and I'll let him ride as long as he behaves himself!"

"Splendid!" said the Hon. Mr. Reek.

0 notes

Photo

Science Saturday

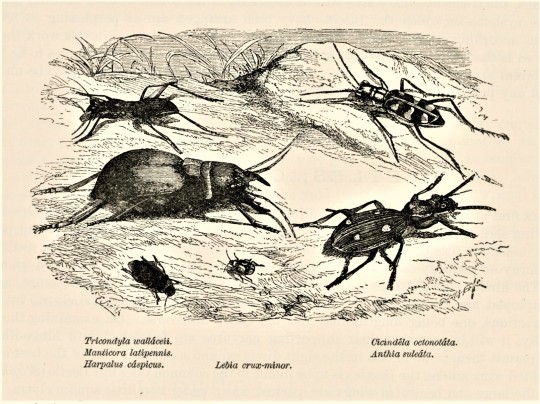

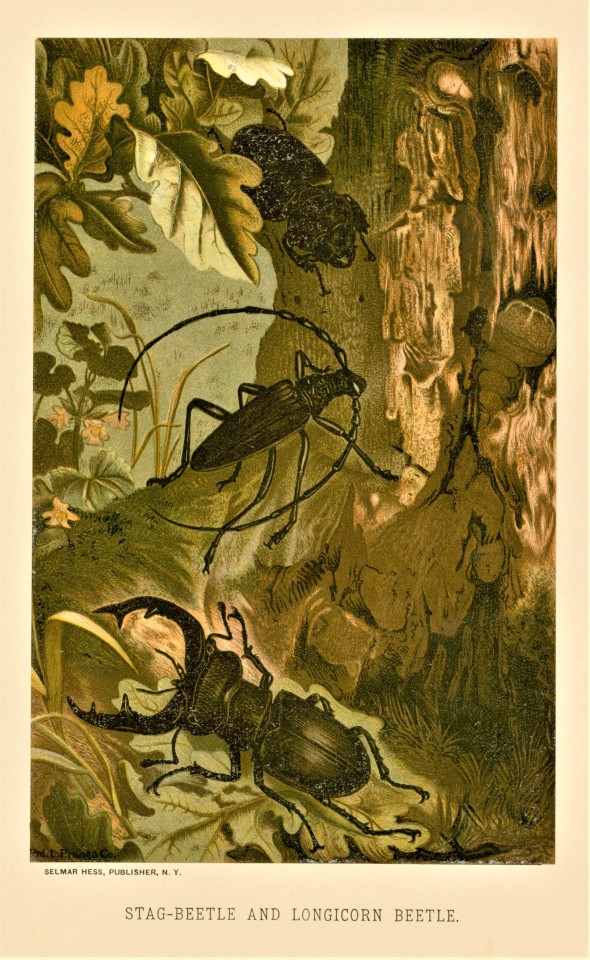

IT’S THE BEETLES!

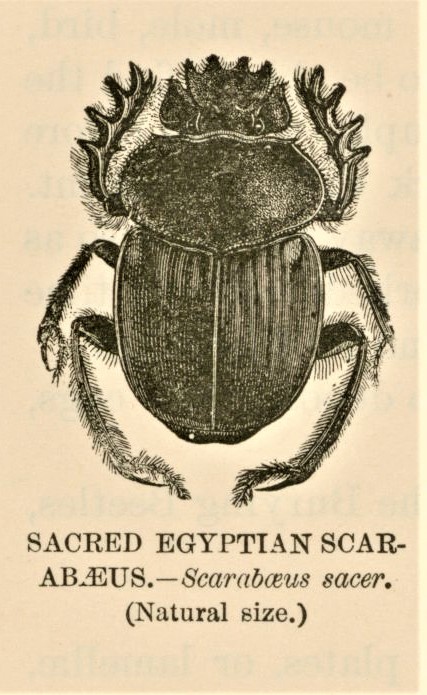

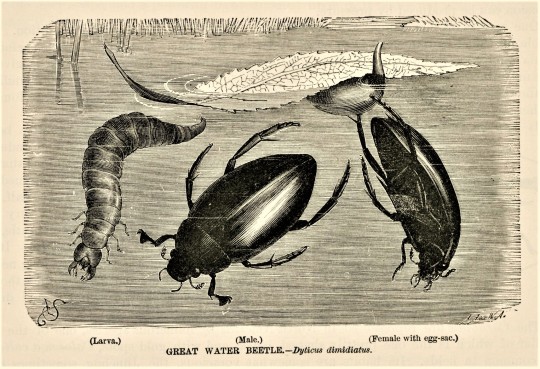

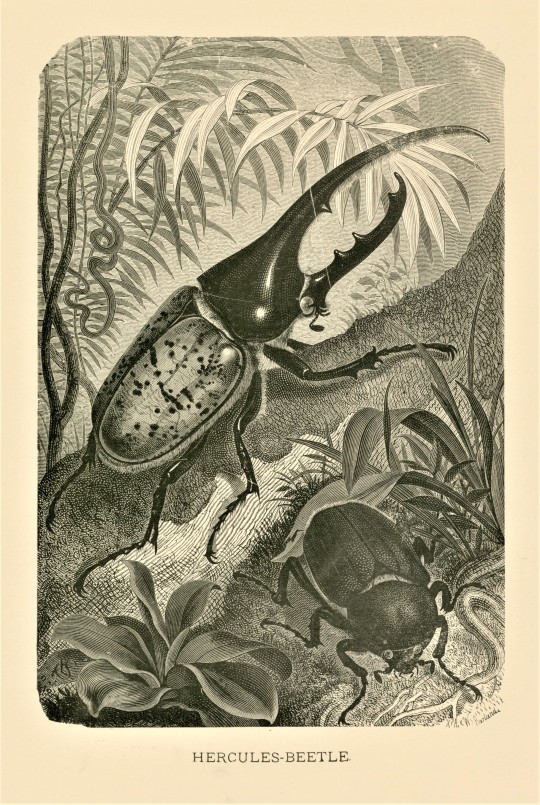

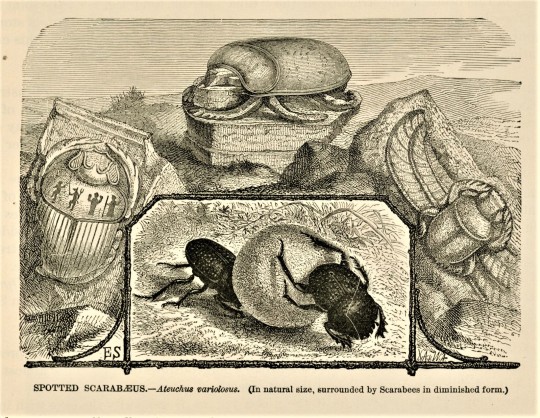

Sarah Finn, our long-time graduate intern and former social media science editor (now Archival Projects Librarian at Milwaukee Public Library) was always deeply intrigued by insects, especially beetles. So, in her honor we present these wood-engraved and chromolithographed beetles from our 1885 three-volume edition of J. G Wood’s Animate Creation, adapted to American zoology by the American physician and zoologist Joseph B. Holder and published in New York by Selmar Hess. The publication, a revision of Wood’s original 1853 British publication The Illustrated Natural History, was originally issued in 60 fascicles, with the chromolithographs printed by the noted Boston lithographing firm L. Prang & Company. Many of the images used in these volumes also appeared in other natural history publications in America and Europe, such as Brehms Thierleben.

View another post from Animate Creation.

#Science Saturday#beetles#insects#stag beetle#Sarah Finn#Animate Creation#J. G Wood#John George Wood#Joseph B. Holder#Selmar Hess#L. Prang & Company#Louis Prang#wood engravings#chromolithographs#Yay chromoliths!#diving beetle#longhorn beetle#scarabs#scarab beetle#spotted scarab#Scarabaeus sacer#dung beetle#Hercules beetle#rhinoceros beetle#water beetle#natural history

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cards by Louis Prang, 1861–1897.

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Painted Lady from The Butterflies and Moths of America Part 2, Louis Prang & Co., 1862

Lithograph 4 ⅛ x 2 ⅜ in. (10.4 x 6.1 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, USA

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The first mass-produced book to deviate from a rectilinear format, at least in the United States, is thought to be this beautiful 1863 edition of Red Riding Hood, published by Boston-based publisher Louis Prang. Leaf through its person-shaped pages here: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/the-first-shape-book-little-red-riding-hood-1863

133 notes

·

View notes