#London and South Western Railway

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Adam's Radial tank, aka Lady! I need to make more liveries for her.

29 notes

·

View notes

Video

LMS (ex GSWR) loco No. 14116 c1925 by Frederick McLean Via Flickr: An old photograph of London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMS) engine No. 14116, with driver and fireman at an unknown station. The reverse has no information on, if you know who the photographer was please message me and I will credit them. This was a H. Smellie designed class 119 4-4-0 engine, built at the Kilmarnock Works, and new to the Glasgow and South Western Railway (GSWR) in Jun 1882 carrying number 119, changing to 119A in Jan 1910, then to 700 in Jun 1919. After grouping of the existing railway companies in 1923 into 'the big four', the GSWR became part of the LMS, in 1924 they renumbered it 14116. The locomotive was withdrawn from service in Dec 1931, then I assume was scrapped, although I could not find the date/place. If there are any errors in the above description please let me know. Thanks. 📷 Any photograph I post on Flickr is an original in my possession, nothing is ever copied/downloaded from another location. 📷 -------------------------------------------------

#old photograph#old transport#vintage transport#vintage photograph#G&SWR#Glasgow and South Western Railway#LMS#London#Midland and Scottish Railway#Midland & Scottish#Midland & Scottish Railway#steam engine#steam train#steam locomotive#steam loco#old steam engine#locomotive#loco#old locomotive#railway#railway station#old railway#old railway station#H Smellie#Kilmarnock Works#4-4-0#class 119#flickr

0 notes

Text

One of the major legacies of the British control of India was the planting of peoples of Indian origin all over the British Empire, including Britain itself. India was considered to be a reservoir of cheap labour. After African slavery was legally ended in 1833, ‘indentured’ labourers were recruited from India to work on plantations in Mauritius, Guyana, Trinidad, and Jamaica. This was slavery in a new guise: many laboured under conditions no less degrading than slavery. Thereafter wherever need arose, Indian labour was employed. Indians worked in the plantations and mines in Ceylon, Malaya, Burma, South Africa and Fiji. Indian labour provided the manpower to build the East African Railway. Indian sailors worked the British merchant navy. Indian soldiers not only helped to maintain the British Raj in India, but were used as cannon fodder overseas in colonial wars of conquest to extend its frontiers.

Indians were brought to Britain too. They did not come as ‘indentured’ labourers, but the principle of cheap labour applied here as well. Many Indian servants and ayahs (nannies or ladies’ maids) were brought over by British families returning from India. Indian sailors were employed by the East India Company to work on its ships. Some of these servants and sailors settled permanently in Britain.

One of the results of the policy of introducing western education in India was that, from about the middle of the nineteenth century, many Indian students began arriving in Britain, some on scholarships, to study law or medicine or to prepare for other professions. Some came to take the examination for entry into the Indian civil service since this examination could only be taken in London. Some Indian students settled in Britain after qualifying, to practise as doctors, lawyers or in other professions. Some Indian business firms opened branches in England. Nationalist politicians came to London, the centre of power, to argue the cause of Indian freedom. Indian princes and maharajahs visited England, not only as guests of the Crown on formal occasions, like the coronations, but also to pay their ‘respects’ to the monarch or for pleasure. London, as the metropolitan capital, attracted many visitors from India. Exhibitions of Indian arts and crafts were displayed in England too. The Asian presence in Britain therefore goes a long way back and forms a prelude to the post-independence migration of Asians to Britain.

�� Rozina Visram, Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: Indians in Britain, 1700-1947 (London: 1986), pp. 9-10.

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

January 29th 1848 saw the first adoption of GMT by Scotland. The subject has been the source of controversy ever since.

The change had broadly taken place south of the Border from September the previous year with those in Edinburgh living 12 and-a-half minutes behind the new standard time as a result.

Some people in those days were still using sundials to tell the time, Scottish inventor Alexander Bain had only given the world the first electric clock 7 years previously. Sundials were criticised for being poorly made and set by "incompetents" among those who supported the move to GMT in the 1840s.

The discrepancy grew the further west you moved, with the time in Glasgow some 17 minutes behind GMT. In Ayr the time difference was 18-and-a-half minutes with it rising to 19 minutes in the harbour town of Greenock.

All these lapses were ironed out over night on January 29 1848, but the move wasn’t without controversy as some resisted the move away from local time.

Sometimes referred to as natural time, it had long been determined by sun dials and observatories and later by charts and tables which outlined the differences between GMT and local time at various locations across the country.

But the need for a standard time measurement was broadly agreed upon given the surge in the number of rail services and passengers with different local times causing confusion, missed trains and even accidents as trains battled for clearance on single tracks.

An editorial in The Scotsman on Saturday, January 28, 1848, said: “It is a mistake to think that in the country generally the change will be felt as a grievance in any degree.

“Probably nine-tenths of those who have clocks and watches believe that their local time is the same with Greenwich time, and will be greatly surprise to learn that the two are not identical.

“Even if they wished to keep local time, they want the means.

“Observatories are only found in two or three of our Scottish towns.

“As for the sundials in use, their number is small, most of them, too, are made by incompetent persons and even when correctly constructed, the task of putting them up and adjusting them to the meridian is generally left to an ignorant mason, who perhaps takes the mid-day hour from the watch in his fob.”

The editorial added: “For the sake of convenience, we sacrifice a few minutes and keep this artificial time in preference to sundial time, which some call natural time, and if the same convenience counsels us to sacrifice a few minutes in order to keep one uniform time over the whole country, why should it not be done!”

Mariners had long observed Greenwich Mean Time and kept at least one chronometer set to calculate their longitude from the Greenwich meridian, which was considered to have a longitude of zero degrees.

The move to enforce it as the common time measurement was made by the Railway Clearing House in September 1847.

Some rail companies had printed GMT timetables much sooner. The Great Western Railway deployed the standard time in 1840 given that passengers on its service between London to Bristol, then the biggest trading port with the United States, faced a time difference of 22 minutes between its departure and arrival point.

Rory McEvoy, curator of horology at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, said travel watches of the day had two sets of hands, one gold and one blue steel, to help measure changes in local time during a journey.

Maps also depicted towns with had adopted GMT and those which had not, he added.

There was information out there for determine the local time difference so they would know the offset to apply to GMT before the telegraphic distribution of time.

Mr McEvoy said different towns and cities in Scotland would have had their own time differences before adoption of GMT.

Old local time measurements show that Edinburgh was four-and-a-half minutes ahead of that in Glasgow, for example.

Mr McEvoy added: “I think it is fair to say there was no real concept of these differences at the time. It was when communication began to expand quite rapidly that it became f an issue. I think generally, you would be quite happy that the time of day was your local time.”

Pics are the station clock at Glasgow Central in the early 1880s and the sundial at Stonehaven Harbour, Aberdeenshire.

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christmas Story

The letters continued...

Threats were issued:

“He’s dead if I ever see him.”

“-and if he ever shows his face around my shed, he’s a dead engine.”

“HIS COMPONENT PARTS WILL REGRET BEING ATTACHED TO HIM.”

“I’ll show him exactly what kind of a terror us diesels can be.”

“Personally, I’d have introduced his teeth to his superheater…”

-

And welcomes were given.

“I suppose this makes you one of ours now.”

“It’s nice to increase the ranks for once.”

“Can we keep you and trade Mallard to the Western?”

“I, for one, welcome you with smooth rails and green signals.”

“-and don’t worry! You’ll fit in just fine!”

-

Forgiveness was given, despite not being asked for.

“We have heard about your recent change in “livery” and we understand.”

“Considering what’s happened I don’t blame you for tossing us into the bin.”

“-I’ve heard talk that some engines are quite taken with what you’ve done. Might be a trend!”

“Usually, old allegiances die hard. In your case, I’m surprised it lasted as long as it did.”

“Perhaps some day we can dispense with the old rivalries altogether…”

“YOU DESERVE BETTER THAN US.”

-

And declarations were made.

“ - you will always be one of us, and we love you.”

“I can’t wait to see you at the next gala!”

“YOU’LL LOOK GOOD IN BLUE, I GUARANTEE IT.”

“Keep us in your memories, but go wherever your heart takes you.”

“Don’t let engines like him keep you in a bad place, okay?”

-

Then there were the signatures.

Your Brother

Your Sister

Your Friend

Your Compatriot

YOUR FELLOW WESTERNER

Your Eastern Acquaintance,

Caerphilly Castle

Evening Star

Deltic

Flying Scotsman

King George V

PENDENNIS CASTLE

№1306 Mayflower

D7017

D7018

D7026

D7076

Western Prince

Black Prince (92203)

Mallard [Who is writing this under duress]

Aerolite

26000 (Tommy)

№ 1420

D9500 & D9531

Lode Star

Green Arrow

№ 4498 Sir Nigel Gresley

The Engines of the Vale of Rheidol Railway

D821, D818, and D832

Blue Peter

55 022 (Royal Scots Grey)

Tuylar

Dominion of Canada

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Bittern

92212

Western Ranger

55 016

№4588

Alycidon (D9009)

№ 65462

Western Champion

Bradley Manor

7819 Hinton Manor

D9002

Royal Highland Fusilier (D9019)

№ 6412

Clun Castle

6990 Witherslack Hall

Sir Hadyn and Edward Thomas

№ 18000 (Kerosene Castle)

4488 (Union of South Africa)

Morayshire

Olton Hall

Hagley Hall

55 021

King Edward I

King Edward II

Western Courier

Western Lady

D9534

№ 7293

Western Campaigner

----------------------

Then they opened the boxes.

The small ones were addressed to Duck and Oliver. The first few were opened up, revealing, “Name plates? Why name plates?”

“Well, hang on a minute, these don’t look like any name plates I’ve seen before.”

“Ah, wait, that’s it. They’re usually curved, to go over the splashers.”

“And they’re not red.”

“Well, they are if… ooooh.”

“What?”

“They’re Eastern. With the red backing. These’re LNER plates.”

Oliver stared at Duck, ignoring how the men were opening up a separate box with a similar return address.

“It’s a builder’s plate?!”

“It’s an LNER builder’s plate, see the shape?”

“Forget the shape, it says London and North Eastern on it.”

“Oh gosh, this is serious, innit?”

“That’s borderline sacreligious is what it is. Lookit that! It says Swindon on it!”

“Gordon is going to be insufferable about this, I just don’t know how.”

-

There was an identical plate for Duck, and… glory be, it really was an LNER-styled builder’s plate, made out with his information. They even found out his original works number.

He breathed in deeply. In through the nose, out through the mouth. He mattered to them, in a way that felt just as, if not more personal than the pile of letters on the floor. Maybe it was the shock, the lingering feelings from hearing Truro’s unhinged rant in the cold December air.

“I think,” he looked between the plate, and Oliver. “That we’re at a moment in our lives that we can’t go back from.”

-----------

The boxes addressed to Bear were much larger, and were in greater quantities.

“Oh look, this one’s a headboard!” exclaimed his driver.

Bear’s eyes nearly popped out of their sockets when he saw that it said THE FLYING SCOTSMAN on it.

The note attached was short, but sweet. “‘Tis nice to have another Eastern Diesel. Mayhaps someday this shall be used again in anger.” It was signed “Royal Scots Grey”.

-

The next one had the GWR crest burned into the surface of the crate. Opening it revealed a rather lengthy nameplate wrapped in cloth. A note was tied around it.

“Dearest Bear,” it read. “He’s done, even if he doesn’t know it yet. This raises an issue - we do need a “City” in our ranks. We think you can take up that role.”

The wrapping was undone, and Bear could feel a shocked tear build up in his eye.

The words CITY OF TIDMOUTH glinted in the lights of the shed, the letters done in shining brass, just like the steam engines of old.

-

Another package, this one from an address that he vaguely remembered as being an old Eastern Region TMD, contained a host of plates both large and small. The largest of them was a bright red rectangle, with silver letters that read BEAR. After looking it over, his crew deemed it to be a dead ringer for the name boards on Eastern Region diesels.

“Which means…” said his driver, rifling through the smaller plates, each the size of a medallion. “That these must be from all the different Depots. Yeah, yeah, look. This one’s Stratford, and here’s York. Blimey, I didn’t know that anyone had a Colchester one.”

This went on for several minutes, as plates from seemingly every Eastern Region TMD were removed from the box. Bear’s eyebrows rose until they could go no higher.

-

The next morning, his crew busied themselves with attaching several of the plates to his sides. There was some argument as to where they should be placed, and how to avoid making Bear look like “he was covered in fridge magnets.”

Said argument was still ongoing as Gordon rolled by. His suddenly-wide eyes went from the Eastern Region name plate to THE FLYING SCOTSMAN headboard in shock.

Bear ignored his crew, who were intently measuring the “CITY OF TIDMOUTH” nameplate like it may suddenly change size, and fixed Gordon with an intent look. “This is unequivocally your fault,” he said, keeping his tone serious even as he started to smile. “Thank you.”

----------

A few days later, as the mail started to peter off, a deeply overstuffed document mailer ended up at the shed in Arlesburgh, addressed to Oliver and Duck collectively.

It was a long and dry letter, filled with passages about duty and honor, dictated by King George V, the “self-proclaimed pro tempore leader of our kind, now that Truro is out.”

Naturally, Duck found it fascinating, while Oliver would rather gnaw off his own buffers. It grew so dull that eventually the stationmaster got bored of reading Duck’s copy of the pair of identical letters aloud, and fetched a sheet music stand from the station, placing the type-written pages across it for the two engines to read at their own pace before leaving for the station.

Oliver’s pace was “no, thank you, but I’d really rather skip to the end,” but Duck was insistent on reading the entire letter aloud.

“-I humbly ask you as a fellow Westerner, free of all but our Swindon metal, do you have any interest…” Duck abruptly trailed off.

“Hm?” Oliver said, blinking himself to attention. “Interest in what? Don’t tell me you’ve gotten bored now?”

Duck ignored him. “They can’t really-”

“Really what? Out with it!”

“Look!” Duck yelped. “It’s right there, on the fifth page, towards the bottom.”

Oliver rolled his eyes, but eventually found the sentence. “-any interest in becoming the new figurehead of the Great Western? What?” He squeaked in surprise, eyes skimming the preceding paragraphs to see what in the world they were on about.

“-perhaps the most unfortunate part of Truro’s fall from grace is that he is - or perhaps was - the most recognizable member of our lineage by a wide margin. While it remains true that the enthusiast may recognize myself or Caerphilly, the general public likely knows Truro for the same reason that they know Flying Scotsman. The name Great Western, and what it stands for, is vestigial at best.

That being said, a new opportunity has presented itself. As I am sure you are aware, the books by the Reverend Awdry featuring you and Oliver have spawned a television show, which has in turn re-ignited popularity in the books. Already I have had to field queries about your Island from children clutching copies of “Duck and the Diesel Engine.” Many who have no other knowledge of our ways have nonetheless made the connection that we Westerners all know each other, and have asked me about you and Oliver. Strangely, none have asked about Truro; in fact, one child, who I have been assured does not yet know how to read, mistook me for Truro, and asked me what visiting Sodor was like. (I did not dissuade him of this view. I hope that I was correct in my assumption that Sodor is very pleasant in the summer.)

I’m sure that you can see the common thread here. You and Oliver will have an uncommon familiarity with the next generation, and possibly many more beyond. While I, Caerphilly, and the rest sit quietly behind ropes, you will continue as a working engine, adding to our common lore, and preaching our gospel. You are the highest ranking Paddie Shunter to survive the purges of Modernization, and you know more of Our Ways than even I do.

With this in mind - and please do not take this as an obligation, a chore, a weight against your buffers - I humbly ask you as a fellow Westerner, free of all but our Swindon metal, do you have any interest in becoming the new figurehead of the Great Western Railway?”

--

Neither engine got any sleep that night, and it was a very bleary Duck that took the first train into Tidmouth the next day.

“You look terrible,” Gordon sniffed unthinkingly. “Do you not sleep at night? Too much rearranging of your goods yard, perhaps?”

“Gordon, please-”

On the road opposite Duck, Bear raised an eyebrow. “It’s too early in the morning for either of you to start.”

“Oh fine,” Gordon huffed as the last of the passengers flooded into the express. “But it’s rather undignified for an Easterner to be so disheveled. Just look at us for an example, Duck!”

Point made, he set off with a whoosh of steam, and within a minute the train’s rear lamp was fading into the distance.

Bear didn’t say anything for a long while. Duck wondered if the diesel wasn’t saying anything because Gordon was right - compared to Bear’s mirror-shine paint and Gordon’s polished brass, he looked awful.

Or, the vicious little voice in the back of his mind piped up. He still doesn’t want to talk to you. Considering how you sided with Truro over-

“So, I got a letter yesterday.” Bear said, apropos of nothing. “From King George V herself.”

“Oh?” Duck seized the chance to get out of his own mind. “What about?”

“Seems like the Great Western needs a new figurehead, considering that somebody has lost all his prestige.”

“O-oh…” Duck warbled. “You got that too?”

“Mmhmm.” Bear wasn’t looking at anything in particular. “Apparently the television show is driving people to the books; people seem to like conflict in their children’s books. Something about being able to show right from wrong.”

“Do they now?” Oh, if only the rails could swallow him whole at this moment.

“Oh yes.” Bear looked contemplative. “It also helps that nobody really likes diesels. Smelly, underhanded things. It’s quite nice to be able to have one cause trouble and then get sent away for doing that in one single book.”

“Yes, I-I’m quite aware of what happened…” Maybe his boiler could explode. That might fix things.

“And everybody loves a runaway train.”

“Well, I -uh, I wouldn’t- um…”

Bear smirked. “Obviously I don’t include you in that.”

“W-w-well of course, I-”

Bear didn’t say anything for a second, and Duck continued to trip over his own tongue, until:

“She’s right, you know.”

“Wh-what?”

“King George. She’s right about you. Every child in the country is going to know your name someday, especially if they put you on the telly. And there’s not another engine alive who knows all of the history that you do.”

“Bear,” Duck finally managed to find his voice. “I can’t.”

“Why not?”

“Why not?” Duck was floored. “Bear, you were there! I just followed along behind him, doing whatever he said to-”

“Duck,” Bear cut him off and looked him straight in the eyes. “He was City of Truro. Who would have expected that out of any engine, let alone one of his stature?”

“But - but - but I-”

“Acted childish, perhaps,” Bear continued, gently. “But he revealed himself to you at the same time he did everyone. Even I didn’t think he’d hurt me on purpose!”

“But I should have noticed!” Duck cried. “And I didn’t! What sort of leader would I be?”

Bear was unmoved. “It’s true that you didn’t notice then, but look at what you’re doing right now.”

“What?”

Bear smiled gently, his new nameplates gleaming in the station lights. “You’re giving yourself the third degree over this. It’s been six months, Duck! Even I’ve moved on from that, or I would, if you’d let me. Truro’s got his just desserts, I’ve found that more engines care about me than I previously thought possible, and Oliver… is Oliver-ing along like nothing ever happened. It’s just you who hasn’t moved on from this yet, and that is the true mark of a leader.”

“No, Bear,” Duck started to stammer. “But-I can’t. Surely-”

“The only sure thing is that you’d do a good job.” Bear said as the last of his passengers boarded. “Besides, if you do badly enough…” The guard blew the whistle, and waved the green flag. “You’ll look really good in garter blue!”

And then he was off, engine roaring. The train sparkled against the early summer sun as it left, and Duck was suddenly alone at the platform.

“He does make a good point,” Well, he was almost alone. He was still coupled to Alice and Mirabel. “What do you want to do?”

Duck didn’t say anything for a long while.

He had a lot to think about.

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

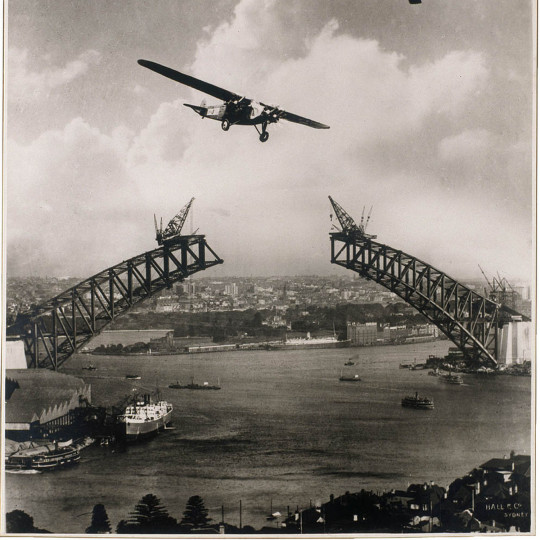

Sydney Harbour Bridge Construction

The Sydney Harbour Bridge – affectionately known as The Coathanger by Australians – was opened to great fanfare and a touch of scandal on 19 March 1932 and was the longest steel arch bridge in the world at the time, with a span of 503 metres (1,650 ft) and standing at 134 metres (440 ft) above Sydney harbour.

Sydney Harbour Bridge During Construction

State Library of New South Wales (Public Domain)

Before the bridge was constructed, there were two Sydneys – the north side, with a population of around 300,000, and the south side and central business district, with 600,000 people. A regular and reliable ferry service took passengers across the harbour, carrying 13 million annually by 1908. There was also a land route from the south to the north shore, which was a time-consuming journey known as the 'five bridges' – horses and cars crossed a series of bridges over the Parramatta River, a detour that added 20-30 kilometres (12-19 mi) to the trip.

As Sydney's population grew and up to 75 ferries crisscrossed the harbour, often in dangerous and foggy conditions, the need for a bridge to connect the northern and southern shores gained momentum. One extraordinary man, Dr John Job Crew Bradfield (1867-1943), envisioned a structure that would unite Sydney – a minimalist, sweeping steel structure embodying modernist design aesthetics, breaking free from the city's convict-era agrarian roots.

Early Designs

Charles Darwin's grandfather, Dr Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), was inspired by reports of the NSW colony and mentioned the vision of a 'proud arch' in his poem Visit of Hope to Sydney Cove, near Botany Bay, published in 1789. However, the first person to seriously propose a harbour bridge was the emancipated convict and New South Wales (NSW) government architect Francis Greenway (1777-1837). In an 1815 report to Governor Macquarie (1762-1824), Greenway raised the idea and also wrote to the editor of The Australian newspaper, which published Greenway's letter on 28 April 1825:

Thus in the event of the Bridge being thrown across from Dawes Battery to the North Shore, a town would be built on that shore, and would have formed with these buildings a grand whole, that would have indeed surprised anyone entering the harbour; and would have given an idea of strength and magnificence that would have reflected credit and glory on the colony and the Mother Country.

(The Australian, Letter to the Editor)

Greenway's vision was never adopted. The engineering skills and steel technology to span the harbour were not yet available, and the NSW colony was focused on agricultural production and settlement.

The next proposal was put forward in 1857 when English-trained engineer Peter Henderson designed a bridge from Dawes Battery (now Dawes Point on the south side) to Milsons Point. Henderson had worked with Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859), the renowned and groundbreaking 19th-century engineer who designed London's Paddington Station, the Great Western Railway linking London with the west of England and South Wales, and various steamships.

Sketch of Proposed Sydney Harbour Bridge

P. E. Henderson (Public Domain)

Henderson's sketch for a cast iron bridge supported by two pylons on either side of the harbour is the oldest existing practical plan. The population and economic activity on the northside in 1857 were not significant enough to convince the colonial government. It is also likely that engineering knowledge at the time would have resulted in a bridge that may have fallen into the harbour. Cast or wrought iron, which is not as strong as steel, might not have been capable of withstanding the stresses of a large span in a harbour with strong tides and a city frequently buffeted by high winds.

By the turn of the century, north shore residents had formed the Sydney and North Shore Junction League, championing a bridge inspired by the vision of Sir Henry Parkes (1815-1896), a local politician and five-time premier of NSW. Parkes had called for a bridge to improve transportation and promote urban development. This resulted in Minister for Works E. W. O'Sullivan (1846-1910), announcing a design competition in January 1900. Submissions were received from local and international engineers.

Continue reading...

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made Eras Tour bracelets of all the times Taylor Swift references trains in her songs. The colours are inspired by different trains and railway liveries. Excessive details under the cut:

"You know that my train could take you home" from Willow. Inspired by Great Western Railway's Intercity Express Trains. It's the train I catch most often, it's my train!

"I knew you, stepping on the last train" from Cardigan. Inspired by the subway cars in New York City, which I think of as having blue seats but it seems yellow/orange is just as (or more?) common. Idk I've never been to New York, my whole knowledge of the subway comes from Broad City and pictures of dogs in Ikea bags.

"I jump from the train, I ride off alone" from The Archer. Inspired by ye olde American locomotives like the Union Pacific No. 119. This lyric evokes Wild West imagery for me and this type of engine is what my British brain thinks of as a "cowboy train".

"Rebekah rode up on the afternoon train" from The Last Great American Dynasty. Inspired by the steam locomotives used in the 1940s by the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad, which is what Rebekah Harkness would have rode up on. Sadly I couldn't find a good colour image of one, so I leaned into it and chose a greyscale colour palette. As it happens the engines were almost certainly black anyway so it's fine.

"Silence, the train runs off its tracks" from Sad Beautiful Tragic. Inspired by my boy Thomas the Tank Engine. There are a lot of derailments on the Island of Sodor, the Fat Controller should probably have been sacked.

"Northbound I got carried away, as you boarded your train south" from I Look in People's Windows. Inspired by the London Underground map. I didn't have any brown beads so the Bakerloo line has been reassigned orange.

"We wait for trains that just aren't coming" from New Romantics. Inspired by the British Rail Class 195 trains created for Arriva Rail North, the network so incompetent that even the Tories had to re-nationalise it. Those trains just weren't coming.

"You took the night train for a reason" from Champagne Problems. Inspired by the British Rail Mark 5 coaches used on the Caledonian Sleeper Service.

"Some trains you can't catch again, you've gotta leave it as it was" from Tim McGraw - Acoustic Demo. This is a deep cut that I expect even a lot of Swifties wouldn't necessarily know, but I've always loved this lyric. It totally recontextualises the song and ironically is a much more adult sentiment than the lyrics of the final recording. Inspired by the livery of Anglia Railways, which are the trains of my childhood. Anglia Railways has been sold and rebranded several times since then, so they are quite literally the trains I can't catch again.

I imagine that Taylor Swift has not been on a train in many years, for obvious reasons. However I appreciate her continued use of train imagery in her songs and I hope she never ever stops :)

#is this the most autistic thing i've ever done?#idk but it's certainly up there#this is a long post that nobody will read#but i had fun putting it together so it's fine

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Train Fiend Day to all who celebrate!

Let's have some sexy Victorian trains, all photos and descriptions courtesy of the National Railway Museum in York.

Steam locomotive and tender, London & North Western Railway, 2-4-0 No 790 "Hardwicke", designed by F.W.Webb, built at Crewe in 1873, withdrawn 1932. (source)

Steam locomotive, London & South Western Railway, 2-4-0WT No 298, 'Beattie Well Tank', designed by W.G. Beattie, built in 1874, withdrawn in 1962. Renumbered 30587 by British Railways. (source)

Steam locomotive, London & South Western Railway, M7 class 0-4-4T No 245, designed by Dugald Drummond, built at Nine Elms in 1897, withdrawn in 1962. (source)

If we take a 1897 setting for Dracula, then this would be the kind of brand new train that Mina would get very excited about.

Steam locomotive and tender, No 3, 'Coppernob', 0-4-0, for Furness Railway, designed by E Bury, built by Bury, Curtis and Kennedy in 1846, withdrawn in 1900. (source)

Steam locomotive and tender, London & North Western Railway, 2-2-2 No 3020 "Cornwall", designed by Trevithick, built at Crewe in 1847, withdrawn in 1927 and components. (source)

Steam locomotive and tender, London Brighton & South Coast Railway, 0-4-2 No 214, "Gladstone", designed by William Stroudley, built at Brighton in 1882, withdrawn 1927. (source)

Steam locomotive and tender, Great Northern Railway, 4-2-2 No 1, designed by Patrick Stirling, built at Doncaster in 1870, withdrawn in 1907. (source)

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Modern Belgian masters" distracted me at the beginning of chapter V of The Hound of the Baskervilles in the most recent Letters from Watson. Doyle's offhand references to literature, pop culture, and politics usually have some substance behind them, and "modern Belgian masters" did not disappoint.

Belgium was a hotbed of artistic controversy! In 1876, a group of "rebellious" artists can formed what became L'Essor as a counterpoint to conservative art institutions. In 1883, L'Essor refused to exhibit James Ensor's De oestereetster on grounds that the painting was too risque (since oysters were considered an aphrodisiac, as well as resembling certain female parts). Rebels against L'Essor formed Les XX, which held its own exhibitions featuring more avant-garde artists, including Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and Seurat.

Since Watson refers to Holmes having "the crudest ideas" about art, I'm guessing Holmes sided with Les XX on using experimental styles and unusual subjects to provoke (and to make political points). Whether the conversation included Ensor's etching Le pisseur, which shows Ensor urinating on a wall of graffiti that declares "Ensor es fou" (Ensor is crazy)... we can only hope.

This is just the beginning of a chapter that contains a lot of sly humor. For instance, when Holmes social-engineers information out of the desk clerk, the guests he asks about are a coal-merchant from Newcastle (so known for its coal that the phrase "like taking coals to Newscastle" meant taking a thing to a place where everyone already has plenty) and a very old lady named Mrs. Oldmore.

Sir Henry Baskerville establishes himself as rough-edged, choleric, and unaware of social nuance by yelling at the German waiter. Being rude to any staff would have been seen as ungentlemanly at the time (as now). There's more to it, though. Germans were the largest immigrant group in London in 1889, and their tradition of professional training made them highly in demand as waiters (source).

And then there's the man with the black beard, who has the wit and gall to tell the cab driver that he's Sherlock Holmes. It seems that there have not been sketches of Holmes in any press! Is he the same man with a black beard as butler Barrymore?

The telegram experiment seems to indicate not, but I'm not sure how probative it is.

The bearded man in the cab had his cab driver make haste to Waterloo Station, which served the London & Southwestern Railway. The L&SR took a northern route around Dartmoor, stopping at Exeter and Plymouth.

Watson and Sir Henry will be leaving from Paddington Station, which served the Great Western Railway. GWR takes the southern route along the Devon coast.

When I look at modern railroad schedules, a trip from London to somewhere around Dartmoor takes about 3.5 hours. Is that within the time frame of Sir Henry and Mortimer walking back to the Northumberland, the wait for Holmes and Dr. Watson to arrive for lunch, the luncheon itself, and finally the rigamarole of sending the telegram? It feels to me like it could be -- and also, when I was looking up old schedules for the short story with the missing train, it seems that sometimes Victorian lines ran faster than modern ones.

How common even were black beards? In latter half of the 19th century, beards were fashionable, though not universal. Dr. Alun Withey's discussion of 19th century beard styles shows an ad for false beards. The style at far right looks about right.

It's possible that someone is framing -- or just confusing the issue by imitating -- the butler Barrymore.

We are assured again that Rodger Baskerville died unmarried, which is starting to strike me as "protesteth too much."

Rodger is the one who went to make his fortune in South America. The largest silver deposits were in Bolivia and Peru, and Agatha Christie's Hastings goes to Argentina, so those are the countries where I started on looking for when civil registration of marriages and births started. The answers are 1940 in Bolivia, 1886 in Peru, and 1886 in Argentina. Peru did not start registering deaths until 1889. Before that time, proving a marriage or a birth meant going to the parish church records.

So the Baskerville family solicitor could not simply send a telegram to a government agency in the capital of Bolivia, nor hire a clerk at a Bolivian law office in the capital city to go check. Someone would have to identify the parish where Rodger would have married, produced an heir, or died -- which might be three different places. And then someone has to see about looking through a handwritten register.

How sure are we really that Rodger is even dead?

Since Holmes is so eager to send Watson along with Sir Henry, I assume he's counting on Watson's credulity to maximize the impact of planned shenanigans. Is this a story about a mysterious dog or a story about a grift?

38 notes

·

View notes

Note

What are Sir Topham Hatt’s (and the engines) opinion on how privatization was handled? When I read about it, I always think how absurd it was to keep the track nationalized, but let other companies run the goods trains, then different run the passenger trains. It is a spaghetti mess. Sodor had the right idea to yoink the old Furness mainline.

Thank you for your ask! (and I'm really sorry for the long wait). This is actually going to be really fun to potentially answer, so let's see...

Officially, the NWR regards privatisation as: "an important milestone in Britain's railway history and the beginning of cooperation between the NWR and our partner railways throughout Great Britain." It's a very prim and proper way of saying "the only thing that changed was the name of the idiot company that keeps delaying our trains." In private however, reactions were very, very different.

For a few engines, it meant very little: Thomas in particular barely cared at all. "What'll change? Not my branchline, that's for sure!" he once snapped at Duck when the Western engine tried to goad him into ranting with him about privatisation. Duncan said something very similar to a visiting diesel, only his version was far too inappropriate to be put in writing. Ever.

In stark contrast, a lot of the engines had very loud opinions about the entire thing. Duck spent most of one night trying to tell anyone who would listen that it was "disgraceful, disgusting and despicable" that the GWR hadn't been reformed after privatisation. (Henry, James and Gordon had to be physically restrained by BoCo and Bear before they tore Duck a new funnel for stealing their catchphrases). Donald and Douglas both tried to convince the Fat Controller to send them to London to 'politely make a case for a fully independent Scottish network'... multiple times. They also managed to say such inappropriate things that Oliver had to double-head all of Douglas' trains for a month to act as a censor for his language!

Gordon decided to offer the press his own solution to the privatisation issue, which went something like this: "What we need, is four companies to look after trains in different parts of the country - like we used to." "Like the Big 4?" "Indeed!" "We can't do that, such a system is considered to be a monopoly, and the government won't allow it." "Alright then, how about this: we have one railway that runs in the North and the East... and down to London perhaps. Then we can also have one railway that runs in the Midlands, and in Scotland... and also down to London perhaps, so you have your competition. Then we could have a railway that is in the West, and one in the South-" "Like the Big 4?" "No! These companies would be completely different!" "Look, Gordon, the government has made it very clear that the Big 4 will not return." "Well then FUCK JOHN MAJOR AND ALL THE TORY PARTY! [...] There would be competition anyway, with the roads, don't those blithering idiots understand?! [...] If any of them took a train for once, they'd realise just how bloody stupid the whole thing is, the bunch of------" (About twenty minutes worth of ranting has been omitted, due to various constraints...)

It was no surprise to anyone that Gordon personally campaigned for the Labour Party in 1997.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Sir Stephen Hatt and his sister Bridget were frantically pouring over the old charters of the NWR, hoping to be able to keep the new companies off Sodor - and indeed they found they could, as a 1925 Government deal originally intended to keep the NWR independent of the LMS also (entirely by accident) meant that no private, standard-gauge railway company other than the NWR could operate on the Isle of Sodor. Sir Stephen happily shoved that document in parliament's face when they tried to privatise the NWR's various assets, and then got his deal for the Furness Line from a different parliament committee before anyone could cross-reference him. By the time anyone managed to question why exactly they were selling an entirely railway line to a man who had very loudly told them to 'shove off and leave my railway alone', Sir Stephen had already taken control.

Their opinion: "Why treat a railway like its an airline? Honestly, it'll just wind up causing more problems in the end. A railway is a public good - yes, it makes us a lot of money, but we still run it for the people of Sodor, not for - no, we don't know why they divided British Rail like that, it makes no sense to us either - please stop asking more questions before we can finish our thoughts."

Also, a small rather large side note - Britain's railway privatisation is a complex and very unique affair that really showcases how exactly not to privatise a railway network. For example: for around seven years, the railway infrastructure was owned by a private company called RailTrack... which was terrible at doing its job and caused a number of major railway accidents (See Hatfield, 2000; Southall, 1997; Ladbroke Grove, 1999) and then panicked after the Hatfield crash and basically shut the network down, leading to questions over its competence and the finally its re-nationalisation because - surprise surprise - a private company trying to produce profits really shouldn't be in charge of the safety of millions of people with almost no proper accountability. Worse yet, the monopolies that the Tories wanted to avoid by breaking up the system happened anyway - see EWS, which bought up almost all the freight franchises and created a monopoly, only to be bought by Deutsche Bahn, which created an even bigger monopoly as it also owned (at the time) Arriva (they sold Arriva in 2024). To worsen the spaghetti, the system was divided into three basic sections: the infrastructure (RailTrack), Train Operating Companies (who owned the trains) and Franchises (who ran the trains and hired staff). In other words: a ticket in the UK is so expensive because you are paying for: the train crew, renting the train, renting the track, renting the platforms and producing profits for shareholders.

Oh, and suddenly freight and passenger trains owned by different companies are all competing to have priority at every. single. signalbox. in the country.

Now, I am not an expert in fixing extremely broken railway systems, but even still, I feel like I could probably do better than this mess!

Thank you for reading!

#weirdowithaquill#thomas the tank engine#railways#railway series#real life railways too#ask answered#ask me anything#british railways#british rail#privatisation of british rail#ttte thomas#ttte duncan#ttte donald#ttte douglas#ttte gordon#ttte duck

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

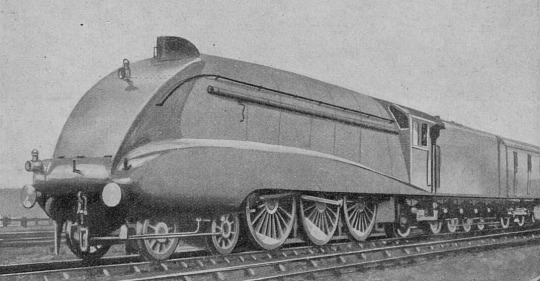

Happy Mallard Day!

Most people in my country will be celebrating tomorrow, July 4th. I’m a bit unusual for an American in that I’m always more excited for July 3rd, because a remarkable feat of engineering history happened that day in 1938 (in multiple senses of the word). Today I’m going to tell the story of a locomotive named for a duck.

(Image: 4468 Mallard, a streamlined 4-6-2 Pacific locomotive, sitting pretty in York, England, United Kingdom. She is painted bright blue with red wheel spokes.)

The story begins well before July 3rd, 1938, of course - mechanical engineer Sir Nigel Gresley was well established in his position as the CME of the London and North Eastern Railway by that date. In 1923, his most famous creation, a 4-6-2 Pacific A1 numbered 4472, took to the rails for the first time. Originally numbered 1472, within a year of running between London to Edinburgh she received her more familiar 4472 after the LNER finally settled on a company-wide numbering scheme - and the name she’d be best known under, Flying Scotsman. She became the company’s flagship locomotive and solidified Gresley’s ability to design Pacifics in the mind of the public.

Her most important contribution to what I’m about to get into the meat of here, though, occurred on November 30th, 1934. On that date, pulling a light testing train behind her, Flying Scotsman hit 100 mph, becoming the first locomotive to hit that speed whilst being officially measured. Other locomotives may have reached 100 mph before, most notably GWR 3700 City of Truro and NYC 999, but this was the first time the speed was officially recorded, and so Scotsman got her name into the record books.

Dating back to the 19th century, railroads in Great Britain competed against each other in what was known as the Race to the North, in which they actively attempted to outdo each other and get passengers from the south, usually London, up to various destinations in Scotland. Nobody ever actually said they were racing, of course, but in retrospect it was pretty obvious what was going on as the railroads introduced faster and faster services. By the 1930s, the railroads had been consolidated into four companies - the Big Four (the Great Western, the Southern, the London, Midland and Scottish, and the heroes of this story, the London and North Eastern). The LMS controlled the West Coast Main Line, and the LNER controlled the East Coast Main Line. (This is important.) In 1927, the LNER started running the named train Flying Scotsman non-stop from London to Edinburgh, utilizing corridor tenders to perform crew changes at speed without stopping. Not to be outdone, the LMS beat them to the punch, running non-stop services between London and Glasgow and London and Edinburgh on their own, and it was officially on. Although speeds were still within a reasonable range at this point, both railroads knew they needed to go faster, and Sir Nigel Gresley looked to Germany.

In Germany, a new streamlined service called the Flying Hamburger had been introduced. This was a diesel train set that ran between Hamburg and Berlin at remarkably high speeds - it had an average speed of 77 mph and could hit around 99-100 mph at its maximum. For regular service, this was impressive, and Gresley wondered if the same could be done using steam power. He knew streamlining was the key, but the LNER knew that the diesels in Germany didn’t have the same passenger capacity as their steam locomotives could pull in carriages, so he needed to get creative. He looked to Bugatti for inspiration; their racecars, in their resplendent blue, were but one thing the car company was working on - they were making streamlined railcars, as well. Gresley took note of their designs, and his new locomotives would eventually pay homage by being colored Bugatti blue.

(Image: a Bugatti Type 54 racecar, painted in a vivid blue.)

By the time Flying Scotsman hit 100 mph in 1934 and another Gresley Pacific locomotive, A3 2750 Papyrus, managed to hit a whopping 108 mph without streamlining, the LNER knew that Gresley was capable of the task, and they allowed him to design a streamlined locomotive. Gresley set to work making improvements to his A3 design, and the first four A4s were born.

(Image: an unidentified A4 Pacific locomotive.)

The A4s were fast, hitting 112 mph on the inaugural run of the Silver Jubilee service between London and Newcastle in 1935. Gresley, of course, was not satisfied - he knew he could still improve his design, and at any rate, his competition over at the LMS was going to be trying to catch him. He went back to the drawing board to make the A4s even better.

As this was going on, the LMS was indeed playing catchup, and they introduced their beautiful Coronation class locomotives, designed to pull the Coronation Scot starting in 1937. The first several of them were streamlined in gorgeous, bright casings, and they caused a stir, taking the British speed record back at 114 mph in an attempt by 6220 Coronation that ended with a sudden braking and a whole lot of kitchenware being flung every which way in the dining car. Engineer/driver T.J. Clark and fireman C. Lewis kept her under control, but the passengers were not amused, and speed records were shelved for the time being...until, once again, Germany entered the fray.

Back in 1936, a German locomotive, the DRG Class 05, set a land speed record for steam, hitting 124.5 mph. Gresley was aware of this and had it in the back of his mind as he improved his A4s. He experimented with giving some of them a Kylchap exhaust system, an innovation developed by French locomotive designer André Chapelon after the work of Finnish engineer Kyösti Kylälä. Chapelon’s work went woefully under-acknowledged, but Gresley paid attention and appreciated his work, and it would pay off. Wind tunnel tests proved a bit frustrating at first until a fortuitous accidental thumbprint helped to move the smoke up and over the locomotive instead of in the crew’s faces, and the stage was set.

4468 Mallard rolled off the line at Doncaster Works on March 3rd, 1938, her name derived from Gresley’s love of breeding waterfowl. Indeed, many of her sibling locomotives were also named for birds, like 4464 Bittern, 4467 Wild Swan, 4902 Seagull, and 4903 Peregrine, but the duck was about to steal the show. Mallard spent the next few months getting used to working and being broken in so she wasn’t brand new, and on the day she turned four months old, it was time to make history.

Mallard’s driver that day was a 61-year-old grandfather named Joe Duddington. As a locomotive engineer, he was experienced and knew how to take calculated risks, and so he’d been assigned to pilot her. With him on the footplate was fireman Tommy Bray and his massive tattooed arms, ready to keep Mallard fed as they drove into the history books. They were performing a “brake test” that day, or so the LNER told most people, passengers included, but Joe and Tommy knew what was actually going on. In the cab with them was an LNER official, Inspector Jenkins, and attached to the train behind the tender was a dynamometer car, there to record Mallard’s speed throughout her run. Since this was an alleged “brake test” the dynamometer car didn’t raise any eyebrows right away. Gresley himself unfortunately wasn’t in the best health that day and was unable to be present himself, but there were enough LNER officials on hand to see to it that everything ran smoothly. Mallard was fitted with a stink bomb of sorts of aniseed in case the big end bearing for the middle of her three cylinders overheated, as the A4s had previously had difficulty with this, and she set out heading northwards. The return trip was where everything was going to get serious.

Upon turning around to return south to King’s Cross, passengers were finally informed of what was going to happen and were given the opportunity to disembark and take another train if they were worried, especially given what had happened during the LMS record attempt a year prior. Everyone agreed to stay on board. Joe Duddington turned his hat backwards, a reference to George Formby’s character in the film No Limit, and opened the throttle.

Mallard slid back onto the main line, headed towards Grantham, where the speed-up was to begin. Unfortunately, work on the track limited her to only 15 mph at this stage, and Joe Duddington got her through the Grantham station at only 24 mph instead of the 60-70 mph she should have been at. Nevertheless, she began to build up more and more speed as she climbed up Stoke Bank, and Duddington had her at a solid 85 mph at the summit.

“Once over the top, I gave Mallard her head, and she just jumped to it like a live thing,” Duddington recounted later in an interview. Her speed rapidly increased, and she was soon hitting 110 mph, at which point he told her, “Go on, old girl, we can do better than this!” Mallard responded, and by the time she was flying through a village called Little Bytham, a blur of blue paint and pumping rods and flying ash, she had well exceeded the LMS record and was even with the German DRG Class 05. The needle in the dynamometer car tipped up higher and higher and surpassed the Class 05 by slipping up to 125 mph...then, for about a quarter of a mile, reached even higher, at 126 mph. She’d done it.

Mallard had to slow down soon after because of a junction, but Joe Duddington and Tommy Bray were sure she could have gone faster had they not had to slow for construction - they believed she was capable of 130. The big end bearing did overheat, and Mallard was detached from the train at Peterborough and brought back to Doncaster to be fixed up, but not before one of the most famous photos in railroad history was taken:

(Image: the crew poses in front of Mallard, a 4-6-2 Pacific locomotive numbered 4468, immediately after setting the speed record. L-R: Tommy Bray [fireman], Joe Duddington [driver/engineer], Inspector Jenkins, Henry Croucher [guard/conductor]. Joe Duddington has turned his hat around to face the correct way again after having it on backwards during the record run. Photo credit: National Railway Museum.)

Joe Duddington actually stayed on a bit past his retirement age to help free up soldiers for the war effort. When he finally retired, on his final day of work, he drove Mallard one last time.

Sir Nigel Gresley himself never accepted the brief stint at 126 mph, instead saying his locomotive set the speed record at 125 mph. But history has accepted the 126 mph as the true top speed, given that Mallard was possibly capable of even more, and today she has plaques on her streamlined cladding to commemorate her feat. A second record attempt was planned to see if she could go even faster, but World War II broke out and the idea was scrapped.

youtube

Tommy Bray eventually got on the throttle himself, fulfilling his own dreams. Both men are honored in a cemetery in Doncaster with a new memorial headstone for Duddington featuring Mallard on it.

As for Mallard herself, she continued working until April 25th, 1963, at which point she’d clocked nearly a million and a half miles in service. She was pulled for preservation for obvious reasons, and today she lives at the National Railway Museum in York, along with her dynamometer car that recorded her history-setting run. Five of her A4 siblings also survive, and a few of them are operational to this day, including the one named for her designer, Sir Nigel Gresley. Of all of his ‘birds,’ the one that flew fastest was the humble duck.

For more on Mallard and her creator Gresley, here are a few resources:

Mallard: How the Blue Streak Broke the World Speed Record by Don Hale is a great book on the subject that I enjoyed thoroughly. It does have a Kindle edition if you’d prefer an ebook variation, as well, and most major book retailers carry it on their websites.

The National Railway Museum, Mallard’s retirement home, has a 3D experience/ride of sorts that simulates what it was like to be running with her that day, the video of which is online here. Note the music, which mirrors her three cylinders pumping away. The video isn’t able to be embedded, but you can watch it here. There’s also a child-friendly version, too.

Lastly, the appropriately named prog rock band Big Big Train did a song about Mallard called East Coast Racer, which regularly moves me to tears because this locomotive means so much to me and they tell her story so lovingly.

youtube

I actually recommend checking out the live version, too, because they show the photo of the crew at the end and every single time I start sobbing.

If you want to visit the old girl herself, she’s at the National Railway Museum in York in the UK, and they have a ton of amazing resources and incredible locomotives and rolling stock in their collection. I’d highly recommend checking them out if you can!

Happy Mallard Day, everyone. Fly far, fly fast, make history.

#LNER Mallard#LNER 4468 Mallard#LNER#LNER A4#I like trains#I spent literal hours on this whoops#but she's really important to me

111 notes

·

View notes

Video

LMS (ex G&SWR) class 14 4-4-0 loco No. 14374 by Frederick McLean Via Flickr: An old photograph of locomotive No. 14374, unfortunately there is no information on the reverse so date, location, photographer are unknown. Leaning against the cab footplate is a 'long slice', used to clear out the firebox. No. 14374 was a J. Manson designed class 14 4-4-0 engine, built at the Kilmarnock Works and new to the Glasgow and South Western Railway (G&SWR) in Nov 1908, carrying No. 157, being changed to No. 346 in Jun 1919. After grouping of the existing railway companies in 1923 into 'the big four', the G&SWR became part of the London, Midland & Scottish Railway (LMS), in 1924 they renumbered 346 to 14374. It was withdrawn from service in Oct 1932, but I cannot find any details of where/when it was scrapped. If there are any errors in the above description please let me know. Thanks. 📷 Any photograph I post on Flickr is an original in my possession, nothing is ever copied/downloaded from another location. 📷 -------------------------------------------------

#London#Midland and Scottish Railway#Midland & Scottish#Glasgow and South Western Railway#14374#4-4-0#Kilmarnock Works#steam engine#old photograph#old transport#transport#transport history#transport photograph#vintage photograph#vintage transport#old train#steam train#vintage train#old steam engine#vintage steam engine#locomotive#old locomotive#steam loco#steam locomotive#vintage steam loco#class 18#photograph vintage#transport vintage#vintage#vintage railway

0 notes

Text

200 years of railroads apparently

So when I was waiting for the train today I noticed the departure boards saying that it was the 200th anniversary of the railway this year (I believe they’re going off of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which was the first public railway to use steam engines and opened in 1825). Which is an important milestone in railway history for sure (although whether it counts as when railroads were invented is debatable) and there are definitely many things we can do to celebrate. To start, however, we can look back at these past 200 years of railroad history and some of the major milestones that occurred. Note that this will focus on British & American rail history since that's what I'm most familiar with. With that out of the way, here is a timeline of railway history:

c. 600 BCE: the ancient greeks moved some boats (water vehicles) over land on some rails

1769 CE: James Watt makes a better steam engine, which is why power is measured in watts and not newcomens.

1804 CE: Richard Trevithick makes a steam train but just as a fairground attraction (railways already exist but they use horses for power).

1825 CE: George Stephenson makes a steam train for the Stockton & Darlington Railway, which marks the beginning of the end for horses. In the coming years, millions of horses are sent to farms upstate, around the back of the shed, or off to work at the glue factory.

Steam trains: - faster and stronger than horses - are made of physics instead of biology (much neater & cleaner) - all of their waste goes into the air instead of the ground - you don't have to wait years for them to grow up

1830 CE: The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) opens in the United States. While probably not the first railroad outside Britain to use steam trains, it is the first to do so in the United States, and since I don't really know much about, say, Belgian railway history it's the one we're going to be talking about.

1840s CE: Railroads form a crucial part of the US's westward expansion, bringing people and goods west (and east I suppose), along with letting the federal government outsource the genocide of the people who already lived there.

1863 CE: The Metropolitan Railway (eventually the Metropolitan Line) opens in central London, as the first urban rapid transit system. Since electric trains weren't a thing yet, this used steam trains. The smoke from the steam trains killed many people, most notably american President Abraham Lincoln when he visited in 1865.

1879 CE: Werner von Siemens makes an electric train but just as a fairground attraction (railways already exist but they use steam locomotives for power) (also there were prototype electric trains before this one but Siemens is the one with a unit named after him so he's who we care about)

c. 1880 CE: The Pennsylvania Railroad and London & North Western Railway become the largest corporations in the world. It's important to note that although railroads are one of humanity's greatest inventions, they did have the unfortunate side effect of also bringing about the dawn of modern capitalism, one of humanity's worst inventions.

1883 CE: The Volk's Electric Railway opens in Brighton. For a time, it included another line that went in the ocean (with rails on the sea floor and really long legs to keep passengers above the water) but this turned out to be a dumb idea and that part closed. The original Volk's Electric Railway is still open as the oldest operational electric railway, and you can go ride on it in the summer. I'll probably do this to celebrate at some point.

1890 CE: The City & South London Railway (later the Bank branch of the Northern Line) opens, finally providing an electric underground rapid transit system for the city and some much-needed relief from the smoke of steam trains. Unfortunately, this was too late to save Abraham Lincoln, who died from being shot in 1865.

1894 CE: a bunch of american southerners LARPing (but less cool than modern LARPers) as british aristocrats but even more racist (than the british aristocrats. all the LARPers I know personally aren't racist) form the Southern Railway. I mention it now because it'll be important later.

1895 CE: The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad opens the first mainline electric railroad. This doesn't mark the beginning of the end for steam power (although it should have) since most railways are privately owned, electrification costs money, and corporations hate spending money.

Electric trains: - faster and stronger than steam - don't require fuel at all - way quieter and don't create any local pollution (can go in tunnels!) - can be powered by renewables & nuclear, once they are invented (hydro is there from the start though) - can go both directions without needing to turn around - can form multiple units (better acceleration and don't need to move the engine around!) - very low maintenance (not constantly having a fire inside does tend to reduce wear and tear on parts) - generally very good

1912 CE: the first diesel locomotive enters service. This turns out to be what marks the end of steam, since diesels are better than steam but are cheaper (to set up. not to run) than electrics. In the coming years, millions of steam locomotives are sent to branch lines upstate, around the back of the depot, or off to work at the scrapyard.

Diesel trains: - faster than steam. except for normal, unmodified, in-service trains, since the fastest diesel is the Intercity 125 with a top speed of 201 km/hr while the steam powered Mallard reached a top speed of 203 km/hr. - stronger than steam. except they aren't, the most powerful diesel loco is weaker than several steam engines. - slower and weaker than electrics (unlike with steam engines, this isn't even close) - louder and more polluting than electrics (although not as bad as steam) - still require fuel (a different sort to steam locos though, and they don't need much water) - can go both directions without needing to turn around - can form multiple units - don't need overhead wires or third rail, which is the only reason they exist (they're mostly better than steam, and although they're worse than electrics they are cheaper. To set up. Not to run.)

1914 CE: The Milwaukee Road electrifies its Pacific Extension out in the american northwest, since steam trains couldn't go in tunnels and were too weak for the hills.

1917 CE: The United States of America nationalizes its railroads under the United States Railroad Administration, in order to put a stop to the private sector's incredible mismanagement of a vital public service during WWI.

1920 CE: After the war ends, the US hands the railroads back to the private companies. Just like all those other times the US did something really, really, good (i.e. Civil War Reconstruction, free school meals during Covid), the USRA didn't last very long and everything went right back to the terribleness of before.

1923 CE: Britain's railroads are grouped from lots of small (and some big) companies into four big companies: the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER), the Great Way Round Western Railway (GWR), the London, Midland, and Scottish Railway (LMS), and the Southern Railway (the real one, not the american south LARPers or modern-day corporate/french LARPers).

1920s CE: The Southern Railway (UK) electrifies much of its network with 750V DC third rail.

1938 CE: The LNER Class A4 "Mallard" sets the rail speed record, reaching 203 km/hr. This makes it the fastest steam train ever, especially since the Pennsylvania Railroad never discovered dynamometer cars or speedometers and had no idea how fast its trains were.

1948 CE: Britain's railroads are nationalized under British Railways (later British Rail).

1950s CE: Gas-turbine trains are invented. Union Pacific uses them for a while, and they briefly also are used for higher-speed trains in some places, but they never really go anywhere.

Gas-turbine trains: - more powerful than diesels - faster than diesels - very loud and kind of inefficient - these things were a bit strange weren't they?

1955 CE: Steam finally starts to die in Britain under BR's modernization plan, which sees electric (yay) and diesel (boo) trains replacing steam locomotives.

1959 CE: Ernest Marples becomes British Minister of Transport. He's also head of a road construction company. This means he wants more roads and less trains. This is a bad thing.

1960s CE: Dr Beeching (a guy Ernest Marples hired) makes a report suggesting closing most of Britain's rail network, starting with the least profitable and redundant routes. The government then ignores most of the suggestions in the report, and closes down whatever rail lines they feel like. Fortunately, the cuts aren't as large as the report suggested. Unfortunately, they are still enormous and cause huge damage to Britain's rail network that is only just starting to be repaired.

1964 CE: The Tokaido Shinkansen opens in Japan as the world's first dedicated high speed train. This marks the pinnacle of human transportation, and electric high speed rail takes its place as the most efficient, most comfortable, most environmentally friendly, and fastest (below a certain distance) form of transportation. Many other countries start to build their own networks, including France, Italy, Spain, China, Morocco, Turkey, Britain (tries to, anyway), some other places, and a couple failed attempts in the US (along with the successful kind-of-high-speed rail in the Northeast Corridor and the still under construction one in California).

1968 CE: Steam finally dies in Britain. Yes, after the Shinkansen was built. Unfortunately, diesel trains continue to exist to this day.

c. 1970 CE: Running out of money, the Milwaukee Road decides to end electrification, since diesels are much better than they used to be and fuel is pretty cheap.

1971 CE: With passenger service not making enough money (it was making money, just not enough money) due to all of those free government-provided highways and airplane subsidies, the US government under Richard Nixon forms Amtrak to take over passenger services and give them a quiet death. Fortunately, this doesn't work. Amtrak still exists, and Richard Nixon doesn't, so who's the real winner here?

1973 CE: The 70s oil crisis begins, and electric trains are suddenly back in fasion after gasoline and diesel become really really expensive. Except it ends before american railroads do anything.

1974 CE: The Milwaukee Road ends its last electric trains.

1976 CE: The Penn Central, formed from a merger between the Pennsylvania Railroad and New York Central, goes bankrupt and the US government replaces it with Conrail, a sort-of nationalization of some of the US rail network. This doesn't last either, with the network being sold off to Amtrak (who take as good care of it as they can with their limited money), and CSX & Norfolk Southern (who don't, but more on them later)

1977 CE: The Milwaukee Road goes bankrupt.

1980s CE: Several mergers between US railroads result in the B&O (under the Chessie System) becoming part of CSX Transportation (the most boring corporate named railroad in existence), while the Southern Railway (US) merges with the Norfolk & Western to form the Norfolk Southern railway.

1982 CE: The British Rail Class 455 – an electric multiple unit used in south London and the suburbs – is introduced.

1993 CE: Precision Scheduled Railroading – an ingenious way to squeeze as much money out of a railroad as possible while providing awful service, treating employees terribly, never investing in infrastructure until something collapses, not doing basic maintenance, and putting safety fourth – is created, and adopted by all of the largest railroads in North America.

Also 1993 CE: The privatization of British Rail begins. Generally considered a bad idea that even Thatcher wasn't going to do (although her privatizing everything else certainly encouraged it), it ends up creating a mess of privately owned companies, half of which end up being owned by foreign state-owned railway companies like SNCF and Trenitalia.

1994 CE: the british and french moved some trains (land vehicles) under water on some rails

c. 2000 CE: people start to care a lot about climate change, and then notice that electric trains are the most environmentally friendly form of transport (apart from walking I guess but let's see you walk anywhere from tens to hundreds of kilometers every time you want to go to a city you don't live in). Car traffic and local air pollution caused by cars are also problems, which trains can solve. (even diesel trains aren't as bad as cars. whether steam trains are as bad as cars is left as an excercise for the reader)

2001 CE: for no particular reason, planes become unpopular, americans suddenly remember trains exist, and Amtrak's brand new (introduced 2000 CE) sometimes high speed train the Acela becomes very popular.

2002 CE: after it turns out privatizing infrastructure and maintenance was a really bad idea that killed people, Britain's railway infrastructure is renationalized under Network Rail (that's us!)

2008 CE: massive financial crisis happens. China decides to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on high speed rail, the US (and to a lesser extent Europe) decide to spend hundreds of billions on bailing out the banks instead

c. 2018 CE: Battery-electric trains (which had existed in some form or another for over 100 years) and hydrogen powered trains (which were new) become things, because of the previously mentioned hatred of spending money by railroads (the pressure to at least appear sustainable combined with the desire to not spend any money on electrification caused these to exist)

Battery-electric trains - weaker and slower than all other types of train - terrible range (need charging very frequently) - require loads of rare earth metals - can catch fire really badly - the batteries eventually wear out (and are not as easy to replace - as the parts of other trains) - completely useless if you need high frequencies or long distances (you'd need to charge them so often that you'll end up reinventing third rail/overhead line electrification) - JUST ELECTRIFY PROPERLY DAMN IT

Hydrogen trains - anything hydrogen powered is either a scam or is going to explode. or both. explosions are only a good thing when going to space on a rocket and only when controlled. - why do these exist - why

2019 CE: In a major milestone for the company, Amtrak almost breaks even for the first time in its existence. (STOP TRYING TO MAKE IT TURN A PROFIT IT'S A PUBLIC SERVICE AND NEEDS AT LEAST AS MUCH MONEY AS THOSE SOCIALIST NATIONALIZED HIGHWAYS GET ALONG WITH SOME EXTRA FOR ALL OF THE MONEY THEY'VE MISSED OUT ON)

2020 CE: a global pandemic happens and everyone stays home. this means all of the privately operated train companies in the UK start losing loads of money (although a bunch of them were already government-owned. some even by the british government) and the conservatives are forced to do something. they do it badly as usual.

2020s CE: the british conservatives cancel almost all of HS2 except the bit that goes from Birmingham to near London (because they hate the north of england, and transit users, and the environment, and young people, and londoners, and effective infrastructure, and recovering from the pandemic, and investing in the futrue, and everything good in the world; and also because of the cost overruns and delays that they caused). They plan to start selling off the land safeguarded for the route so the north of England will never have high speed rail (or anywhere else in the country that didn't already have HS1. so basically everywhere except London) and no future government will be able to revive the project. Fortunately they lose the election before they can do this. Unfortunately the new government refuses to revive it (except saying it'll at least go to London), so the various northern mayors have to try and scrape together the money to build whatever replacement they can afford with the money they've found in the couch cushions.

2021 CE: Amtrak gets a whole bunch of money. Not as much as the highways get, but a lot more than they usually get, and they start making big plans, and there is some high speed rail still in progress in California (it's taking a while but they're still building all of it), and there may even be some in other places soon too.

2023 CE: Norfolk Southern blows up East Palestine (the town in Ohio) after dumping loads of toxic chemicals there, thanks to Precision Scheduled Railroading techniques. They mostly get away with this. Safety fourth!

2024 CE: The british government finally announces it's going to renationalize the railways under Great British Railways (and unlike the conservatives they actually use the term "renationalize"). Also, Network Rail is now on the tumbles (you're reading a post from it right now).

2025 CE: The first british train operating companies are set to be nationalized under GBR, just in time for 200 years since the Stockton & Darlington opened.

#network rail#network rail essays#Railway 200#railway history#this took a while#I may still be jetlagged#I did do some actual research to make sure I had the dates right#it is funny to imagine Abe Lincoln taking the metropolitan line#he totally could've done it#maybe it was after he got back from faxing a samurai#anyways thats enough writing for tonight#enjoy this somewhat informative and hopefully funny timeline of railway history

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

On July 31st 1845 The Caledonian Railway Company was incorporated by the Caledonian Railway Act.

In spite of its initial promotion and capital subscription being largely English, the Caledonian Railway became the most Scottish of the pre-grouping companies: its blue locomotives reflected the Saltire, and its adoption of both the “Lion of Scotland” and the Royal Arms of Scotland as the Company Coat of Arms meant that these appeared on everything from locomotives and carriages to buildings, timetables, stationery, and hotel crockery.

The first section of the railway between Carlisle and Beattock was opened on 10 September 1847. The line was completed to Glasgow and Edinburgh on 15th February 1848 and to Greenhill / Castlecary on 7th August 1848, where it joined the Scottish Central Railway. The line to Glasgow utilised the earlier railways Glasgow, Garnkirk & Coatbridge, and the Wishaw & Coltness, which it purchased in 1846 and 1849 respectively.

Between 1849 and 1864 the company repeatedly tried to absorb the Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway Co. into the Caledonian system. If it had succeeded the Caledonian would have had a virtual monopoly of Scottish Railways. The company however acquired other lines and later the services encompassed Aberdeen, Dundee, Forfar, Perth, Stirling, Oban, Ardrossan, Peebles and a large number of other locations.

The Company also owned two very fine hotels as part of the stations at Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Princes Street. The development of the majestic hotel and golf course at Gleneagles was interrupted by WW1 and was not fully completed until after the grouping.

Caledonian was grouped with the Glasgow & South Western Railway, the Highland Railway, the London & North Western Railway, the Midland Railway and a number of smaller railways across Scotland and England to form the London, Midland & Scottish Railway Co in 1923. This company was nationalised as part of British Rail in 1948.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

this is fucking deranged

this is baso one train interchange why does it look like this