#Lit Review

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Schizoid characters may privately devalue or mock what they see as repetitive conversations, empty gestures and meaningless ritual. Ironically, however, as much as the schizoid dislikes making small talk, in most of his interactions with others, he is apt to do just that to avoid saying anything that reveals his true feelings. Though he may view himself as capable of consequential exchanges, he is fearfully compelled to keep things banal. He fears that something will come out of him that he is not expecting. Unconsciously involved in this inner compensatory struggle, the schizoid usually reports feeling exhausted after social occasions without knowing why.

Zachary Wheeler- Treatment of schizoid personality: an analytic psychotherapy handbook

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary: Chapter 4 of Critical Intersex

For many of us, Chapter 4 of Critical Intersex (2009) turned out to be a particularly rich source of information about intersex history. So I (Elizabeth) have decided to give a fairly detailed summary of the chapter because I think it’s important to get that info out there. I’m gonna give a little bit of commentary as I go, and then a summary of our book club discussion of the chapter.

The chapter is titled “(Un)Queering identity: the biosocial production of intersex/DSD” by Alyson K. Spurgas. It is a history of ISNA, the Intersex Society of North America, and how it went from being a force for intersex liberation to selling out the movement in favour of medicalization. (See here for summary of the other chapters we read of the book!)

Our high level reactions:

Elizabeth (@ipso-faculty): Until I read chapter 4, I didn't really realise how reactionary “DSD” was. It hadn't been clear to me how much it was a response to the beginning of an organized intersex advocacy movement in the United States.

Michelle (@scifimagpie): I could feel the fury in the writer's tone. It was a real barn burner.

Also Michelle: the fuckin' respectability politics of DSD really got under my skin, as a term! I know the importance, as a queer person, of not forcing people to ID as queer, but this was a lot.

Introducing the chapter

The introduction sets the tone by talking about how in the Victorian era there was a historical shift from intersex being a religious/juridical issue to a pathology, and how this was intensified in the 1950s with John Money’s invention of the optimal gender rearing model.

Spurgas briefly discusses how the OGR model is harmful to intersex people, and how it iatrogenically produces sexual dysfunction and gender dysphoria. “Iatrogenic” means caused by medicine; iatrogenesis is the production of disease or other side-effects as a result of medical intervention.

This sets scene for why in the early 1990s, Cheryl Chase and other intersex activists founded the Intersex Society of North America (ISNA). It had started as a support group, and morphed significantly over its lifetime. ISNA closed up shop in 2008.

Initially, ISNA was what we’d now call interliberationist. They were anti-pathologization. Their stance was that intersexuality is not itself pathological and the wellbeing of intersex people is endangered by medical intervention. They organized around the abolition of surgical intervention. They also created fora like Hermaphrodites With Attitude for the deconstruction of bodies/sexes/genders and development of an intersex identity that was inherently queer.

The early ISNA activists explicitly aligned intersexuality in solidarity with LGB and transgender organizing. There was a belief that similar to LGBT organizing, once intersex people got enough visibility and consciousness-raising, people would “come out” in greater numbers (p100).

By the end of the 90s, however, many intersex people were actively rejecting being seen as queer and as political subjects/actors. The organization had become instead aligned with surgeons and clinicians, had replaced “intersex” with “DSD” in their language.

By the time ISNA disbanded in 2008 they had leaned in hard on a so-called “pragmatic” / “harm reduction” model / “children’s rights perspective”. The view was that since infants in Western countries are “born medical subjects as it is” (p100)

Where did DSD come from?

In 2005, the term “disorders of sexual differentiation” had been recently coined in an article by Alice Dreger, Cheryl Chase, “and three other clinicians associated with the ISNA��� [so as] to ‘label the condition rather than the person’” (p101). Dreger et al thought that intersex was “not medically accurate” (p101) and that the goal should be effective nomenclature to “sort patients into diagnostically meaningful groups” (p101).

Dreger et al argued that the term intersex “attracts the interest of a large number of people whose interest is based on a sexual fetish and people who suffer from delusions about their own medical histories” (Dreger et al quoted on p101)

Per Spurgas, Dreger et al had an explicit agenda of “distancing intersex activism from queer and transgressive sex/gender politics and instead in supporting Western medical productions of intersexuality” (p102). In other words: they were intermedicalists.

According to Dreger et al, an alignment with medicine is strategically important because intersex people often require medical attention, and hence need to be legible to clinicians. “For those in favor of the transition to DSD, intersex is first and foremost a disorder requiring medical treatment” (p102)

Later in 2005 there was a “Intersex Consensus Meeting” organized by a society of paediatricians and endocrinologists. Fifty “experts” were assembled from ten countries (p101)... with a grand total of two actually intersex people in attendance (Cheryl Chase and Barbara Thomas, from XY-Frauen).

At the meeting, they agreed to adopt the term DSD along with a “‘patient-centred’ and ‘evidence-based’ treatment protocol” to replace the OGR treatment model (p101)

In 2006, a consortium of American clinicians and bioethicists was formed and created clinical guidelines for treating DSDs. They defined DSD quite narrowly: if your gonads or genitals don’t match your gender, or you have a sex chromosome anomaly. So no hormonal variations like hyperandrogenism allowed.

The pro-DSD movement: it was mostly doctors

Spurgas quotes the consortium: “note that the term ‘intersex’ is avoided here because of its imprecision” (p102) - our highlight. There’s a lot of doctors hating on intersex for being a category of political organizing that gets encoded as the category is “imprecise” 👀

Spurgas gets into how the doctors dressed up their re-pathologization of intersex as “patient centred” (p103) - remember this is being led by doctors, not patients, and any intersex inclusion was tokenistic. (Elizabeth: it was amazing how much bs this was.)

As Spurgas puts it, the pro-DSD movement “represents an abandonment of the desire for a pan-intersexual/queer identity and an embrace of the complete medicalization of intersex… the intersex individual is now to be understood fundamentally as a patient” (p103)

Around the same time some paediatricians almost came close to publicly advocating against infant genital mutilation by denouoncing some infant surgeries. Spurgas notes they recommended “that intersex individuals be subjected (or self-subject) to extensive psychological/psychiatric, hormonal, steroidal and other medical” interventions for the rest of their lives (p103).

This call to instead focus on non-surgical medical interventions then got amplified by other clinicians and intermedicalist intersex advocacy organizations.

The push for non-surgical pathologization hence wound up as a sort of “compromise” path - it satisfied the intermedicalists and anti-queer intersex activists, and had the allure of collaborating with doctors to end infant surgeries. (Note: It is 2024 and infant surgeries are still a thing 😡.)

The pro-DSD camp within the intersex community

Spurgas then goes on to get into the discursive politics of DSD. There’s some definite transphobia in the push for “people with DSDs are simply men and women who happen to have congenital birth conditions” (p104). (Summarizer’s note: this language is still employed by anti-trans activists.)

The pro-DSD camp claimed that it was “a logical step in the ‘evolution in thinking’” 💩 and that it would be a more “humane” treatment model (p105) 💩

Also that “parents and doctors are not going to want to give a child a label with a politicized meaning” (p104) which really gives the game away doesn’t it? Intersex people have started raising consciousness, demanding their rights, and asserting they are not broken, so now the poor doctors can’t use the label as a diagnosis. 🤮

Spurgas quotes Emi Koyama, an intermedicalist who emphasized how “most intersex people identify as ‘perfectly ordinary, heterosexual, non-trans men and women’” (p104) along with a whole bunch of other quotes that are obviously queerphobic. Note from Elizabeth: I’m not gonna repeat it all because it’s gross. In my kindest reading of this section, it reads like gender dysphoria for being mistaken as genderqueer, but instead of that being a source of solidarity with genderqueers it is used as a form of dual closure (when a minority group goes out of its way to oppress a more marginalized group in order to try and get acceptance with the majority group).

Koyama and Dreger were explicitly anti-trans, and viewed intergender type stuff as “a ‘trans co-optation’ of intersex identity” (p105) 🤮

Most intersex people resisted “DSD” from its creation

On page 106, Spurgas shifts to talking about how a lot intersex people were resistant to the DSD shift. Organization Intersex International (OII) and Bodies Like Ours (BLO) were highly critical of the shift! 💛 BLO in particular noted that 80-90% of their website users were against the DSD term. Note from Elizabeth: indeed, every survey I’ve seen on the subject has been overwhelmingly against DSD - a 2015 IHRA survey found only 3% of intersex Australians favoured the DSD term.

Proponents of “intersex” over “DSD” testified to it being depathologizing. They called out the medicalization as such: that it serves to reinforce that “intersex people don’t exist” (David Cameron, p107), that it is damaging to be “told they have a disorder” (Esther Leidolf, p107), that there is “a purposeful conflation of treatment for ‘health reasons’ and ‘cosmetic reasons’ (Curtis Hinkle, p107), and that it’s being pushed mainly by perisex people as a reactionary, assimilationist endeavour (ibid).

Interliberationism never went away - intersex people kept pushing for 🌈 queer solidarity 🌈 and depathologization - even though ISNA, the largest intersex advocacy organization, had abandoned this position.

Spurgas describes how a lot of criticism of DSD came from non-Anglophone intersex groups, that the term is even worse in a lot of languages - it connotes “disturbed” in German and has an ambiguity with pedophilia and fetishism in French (p111).

The DSD push was basically entirely USA-based, with little international consultation (p111). Spurgas briefly addresses the imperialism inherent in the “DSD” term on pages 118/119.

Other noteworthy positions in the DSD debate

Spurgas gives a well-deserved shout out to the doctors who opposed the push to DSD, who mostly came from psychiatry and opposed it on the grounds that the pathologization would be psychologically damaging and that intersex patients “have taken comfort (and in many cases, pride) in their (pan-)intersex identity” (p108) 🌈 - Elizabeth: yay, psychiatrists doing their job!

Interestingly, both sides of the DSD issue apparently have invoked disability studies/rights for their side: Koyama claimed DSD would herald the beginning of a disability rights based era of intersex activism (p109) while anti-DSDers noted the importance in disability rights in moving away from pathologization (p109).

Those who didn’t like DSD but who saw a strategic purpose for it argued it would “preser[ve] the psychic comfort of parents”, that there is basically a necessity to coddle the parents of intersex children in order to protect the children from their parents. (p110)

Some proposed less pathologizing alternatives like “variations of sex development” and “divergence of sex development” (p110)

The DSD treatment model and the intersex treadmill

Remember all intersex groups were united that sex assignment surgery on infants needs to be abolished. The DSD framework that was sold as a shift away from surgical intervention, but it never actually eradicated it as an option (p112). Indeed, it keeps ambiguous the difference between medically necessary surgical intervention and culturally desired cosmetic surgery (p112). (Note from Elizabeth: funny how *this* ambiguity is acceptable to doctors.)

What DSD really changed was a shift from “fixing” the child with surgery to instead providing “lifelong ‘management’ to continue passing” (p112), resulting in more medical intervention, such as through hormonal and behavioural therapies to “[keep] it in remission” (p113).

Cheryl Chase coined the “intersex treadmill’: the never-ending drive to fit within a normative sex category (p113), which Spurgas deploys to talk about the proliferation of “lifelong treatments” and how it creates the need for constant surveillance of intersex bodies (p114). Medical specialization adds to the proliferation, as one needs increasingly more specialists who have increasingly narrow specialties.

There’s a cruel irony in how the DSD model pushes for lifelong psychiatric and psychological care of intersex patients so as to attend to the PTSD that is caused by medical intervention. (p115) It pushes a capitalistic model where as much money can be milked as possible out of intersex patients (p116).

The DSD treatment model, if it encourages patients to find community at all, hence pushes condition-specific medical support groups rather than pan-intersex advocacy groups (p115)

Other stuff in the chapter

Spurgas does more Foucault-ing at the end of the chapter. Highlight: “The intersex/DSD body is a site of biosocial contestation over which ways of knowing not only truth of sex, but the truth of the self, are fought. Both intelligibility and tangible resources are the prizes accorded to the winner(s) of the battle over truth of sex” (p117)

There’s some stuff on the patient-as-consumer that didn’t really land with anybody at the book club meeting - we’re mostly Canadians and the idea of patient-as-consumer isn’t relatable. Ei noted it isn’t even that relatable from their position as an American.

***

Having now summarized the chapter, here's a summary of our discussion at book club...

Opening reactions

Michelle (M): the way the main lady involved became medicalized really made my heart sink, reading that.

Elizabeth (E): I do remember some discussion of intersex people in the 90s, and it never really grew in the way that other queer identities did! This has kind of helped for me to understand what the fuck happened here.

E: It was definitely a very insightful reading on that part, while being absolutely outraging. I didn't know, but I guess I wasn't surprised at how pivotal US-centrism was. The author was talking about "North American centric" though but always meant the United States!!! Canada was just not part of this! They even make mention of Quebec as separate and one of the opposing regions. I was like, What are you doing here, America? You are not the entirety of our continent!!!

E: The feedback from non-Anglophone intersex advocates that DSD does not translate was something that I was like, "Yes!" For me, when I read the French term - that sounded like something that would include vaginismus, erectile dysfunction - it sounds far more general and negative.

M: the fuckin' respectability politics of DSD really got under my skin, as a term! I know the importance, as a queer person, of not forcing people to ID as queer, but this was a lot.

E: it was very assimilationist in a way that was very upsetting. I knew intellectually that this was going on. There was such a distinct advocacy push for that. The coddling of parents and doctors at the expense of intersex people was such a theme of this chapter, in a way that was very upsetting. They started out with this goal of intersex liberation, and instead, wound up coddling parents and doctors.

Solidarities

M: I feel like there's a real ableist parallel to the autism movement here… It dovetails with how the autism movement was like, "Aww, we're sorry about your emotionless monster baby! This must be so hard for you [parents]!" And it felt like "aw, it's okay, we'll fix your baby so they can interface with heterosexuality!" [Note: both of us are neurodivergent]

E: A lot of intersexism is a fear that you're going to have a queer child, both in terms of orientation and gender.

E: You cannot have intersex liberation without putting an end to homophobia and transphobia.

M: We're such natural allies there!

E: I understand that there are these very dysphoric ipsogender or cisgender people, who don't want to be mistaken as trans, but like it or not, their rights are linked to trans people! When I encounter these people, I don't know how to convey, "whether you like it or not, you're not going to get more rights by doing everything you can to be as distant as possible."

M: it reminds me of the movements by some younger queers to adhere to respectability politics.

E: Oh no. There are younger queers who want respectability politics????

M: well, some younger queers are very reactionary about neopronouns and kink at pride. they don't always know the difference between representation and "imposing" kinks on others. In a way, it reminds me of the more intentional rejection of queer weirdos, or queerdos, if you will, by republican gays.

E: I feel like a lot of anti-queerdom that comes out of the ipso and cisgender intersex community reads as very dysphoric to me. That needs to be acknowledged as gender dysphoria.

M: That resonates to me. When I heard about my own androgen imbalance, I was like, "does that mean I'm not a real woman?" And now I would happily say "fuck that question," but we do need an empathy and sensitivity for that experience. Though not tolerance for people who invalidate others, to be honest.

E: The term "iatrogensis" was new to me. The term refers to a disease caused or aggravated by medical intervention.

M: So like a surgical complication, or gender dysphoria caused by improper medical counselling!

The DSD debate

ei: i think the "disorder" discussion is really interesting. in my opinion, if someone feels their intersex condition is a disorder they have every right to label it that way, but if someone does not feel the same they have every right to reject the disorder label. personally i use the label "condition". i don't agree with forcing labels on anyone or stripping them away from anyone either.

M: for me, it felt like a cautionary tale about which labels to accept.

ei: i'm all around very tired of people label policing others and making blanket statements such as "all people who are this have to use this label”... i also use variation sometimes, i tend to go back and forth between variation and condition. I think it's a delicate balance between being sensitive to people's label preferences vs making space for other definitions/communities.

We then spoke about language for a bunch of communities (Black people, non-binary people) for a while

E: one thing that was very harrowing for me about this chapter is that while there was this push to end coercive infant surgery, they basically ceded all of the ground on "interventions" happening from puberty onward. And as someone who has had to fight off coercive medical interventions in puberty, I have a lot of trauma about violent enforcement of femininity and the medical establishment.

ei: i completely agree that it's psychologically harmful tbh…. i was assigned male at birth and my doctors want me to start testosterone to make me more like a perisex male. which is extremely counterproductive because i'm literally transfem and have expressed this many times

Doctors Doing Harm

M: for me, the validation of how doctors can be harmful in this chapter meant a lot.

E: something that surprised me and made me happy was that there were some psychiatrists who spoke out against the DSD label. As someone who routinely hears a lot of anti-psychiatry stuff - because there's a lot of good reason to be skeptical of psychiatry, as a discipline - it was just nice to see some psychiatrists on the right side of things, doing right by their patients. Psychiatrists were making the argument that DSD would be psychologically harmful to a lot of intersex people.

ei: like. being told that something so inherently you, so inherently linked to your identity and sense of self, is a disorder of sexual development, something to be fixed and corrected. that has to be so harmful

ei: like i won't lie i do have a lot of severe trauma surrounding the way i've been treated due to being intersex. but so much of my negative experiences are repetitive smaller things. Like the way people treat me like my only purpose is to teach them about intersex people …. either that or they get really creepy and gross. I’m lucky in that i'm not visibly intersex, so i do have the privilege of choosing who knows. but there's a reason why i usually don't tell people irl.

M: intersex and autism have overlap again about how like, minor presentation can be? As opposed to the sort of monstrous presentation [Carnival barker impression] "Come see the sensational half-man, half-woman! Behold the h-------dite!" And like - the way nonverbal people are also treated feels relevant to that, because that's how autism is often treated, like a freakshow and a pity party for the parents? And it's so dehumanizing. And as someone who might potentially have a nonverbal child, because my wife is expecting and my husband and she both have ADHD - I'm just very fed up with ableism and the perception of monstrosity.

Overall, this was a chapter that had a lot to talk about! See here for our discussion of Chapters 5-7 from the same volume.

#intersex#intersex studies#queer theory#gender studies#actually intersex#intersex rights#intersex activism#intersex books#book reviews#book summaries#paper summaries#lit review#critical intersex#intersex history

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queered Gothic: An Introduction to Queer Victorian Gothic Theory

In a time of massive societal change, queer people persisted (and were even written about)!

Welcome to the QVA (Queer Victorian Archive)! This is the first of many posts I hope to make about stories within the Victorian literary canon with queer themes. However, we must begin with some frequent frameworks I shall work with. These are frameworks that may apply to one story, many stories, or may even apply to all stories posted about. However, the purpose of this post is to allow you to understand the terms I will frequently reference.

Firstly, I’ve used numerous scholarly sources, which will be referred to in the citation section below the cut on this post. However, I’ve decided to also place them here. In sum, I will be sourcing from Michel Foucault’s The History of Sexuality, Volume I, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet & Between Men, and the works of Ardel Haefele-Thomas. Below are some key terms that these authors use to refer to Victorian-period sex, sexuality, and gender:

Repressive Hypothesis (Foucault): In the first volume of his History of Sexuality (1976), Foucault fundamentally argues that modern sexuality and sexual tensions are a product of a repressive era of time, roughly corresponding to the 17th through 20th centuries. He argues that under this era, it may appear that human sexuality and gender expression were repressed, but in fact, it was quite the opposite, and it appears that sexual discourses blossomed in the period rather than being functionally oppressed. Through medical, social, political, and other discourses in the 19th century, sex and particularly homosexuality was functionally controlled by a group who sought to distance Victorians from “sexual perversion”. Foucault also argues that sex has had a power structure hold over us, and therefore power, knowledge, and sex are intermingled among one another, and that sex has come to define us in a way that is both controlling but also sometimes freeing.

Homoerotic Triangles (Sedgwick): In her Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985), Eve Sedgwick argues that the relationship between men in literature has towed the fine line between sexual and platonic through the use of homosocial desire to negate homosexual desire/panic. Essentially, homosocial desire describes the existence of very strong bonds between men that they, in turn, fear could lean into homosexual desire. Through this, Sedgwick argues that English literature often has a triangular relationship, deemed a (homo)erotic triangle. In this triangle, two men often have a desire for one another, but use a woman as a channel to which they can focus this desire without slipping into homosexuality or homosociality. The woman often serves as the connecting point for the homosocial desires, and acts as a sort of conduit.

The Queer Victorian Gothic (Haefele-Thomas): Finally, one of my most important frameworks is directly from the Edinburgh Companion for the Victorian Gothic, and is from Chapter IX by Ardel Haefele-Thomas, “Queer Victorian Gothic”. Haefele-Thomas argues in this chapter that a lot of narratives within Victorian literature that are Gothic fundamentally have queer themes, characters, or tropes, primarily because of how much space that the Gothic gave writers. Particularly, she argues that the existence of these themes, characters, and/or tropes were allowed to be explored through numerous means, especially through familial worries, legal issues, and/or medical maladies. She also argues that the Gothic tended to be a liminal genre in the Victorian era, straddling between the “normative” novel genre and something quite different, which allowed for it to be explored more openly. She writes:

“[I]t allowed many nineteenth-century authors to look at social and cultural worries consistently haunting Victorian Britain even as the official discourse worked tirelessly to silence those concerns.”

She also goes on to argue that, because of a stratified, rigid nuclear family culture, these transgressive identities showed themselves only through secretive means; they stayed the “family secret”. It is also to say that the laws surrounding homosexuality were also taken into account at this period, and there were clearly anxieties surrounding transgressiveness and how a socially conservative culture would be changed by these transgressions. She also argues that the pathologization of queer people became common, writing:

“Definitions of disease began to diligently include and pathologize anyone who was not clearly heterosexual and who did not clearly ascribe to a strictly masculine or strictly feminine demeanour.”

While the Gothic allowed for the exploration of these facets of human identity, a wide variety of localized parts of the identity were explored, particularly sex, sexuality, gender, race, ethnicity, among numerous other aspects.

It is possible that from time to time, I will source other scholars and their writings, but this is just a brief summary of what I’ve studied thus far and have the most expertise. I will primarily be focusing on short stories at this time, but will migrate into other media eventually. With that in mind, my next posts will be focused on queer readings of Robert Louis Stevenson’s short story “Olalla”, as well as Vernon Lee’s decadently queer “A Wicked Voice”.

Below: Citations!

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. United Kingdom, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 1990.

Haefele-Thomas, Ardel. “Queer Victorian Gothic.” The Victorian Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion, edited by Andrew Smith and William Hughes, Edinburgh University Press, 2012, pp. 142–55. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt3fgt3w.13. Accessed 17 Nov. 2023.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. Italy, Columbia University Press, 1985. Accessed 25 Jul. 2024

#queer#theory#queer theory#queer lit#queer literature#victorian#queer victorian#gothic#queer gothic#victorian gothic#literature#writing#literary criticism#literature review#lit review#robert louis stevenson#vernon lee#english literature#book blog

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

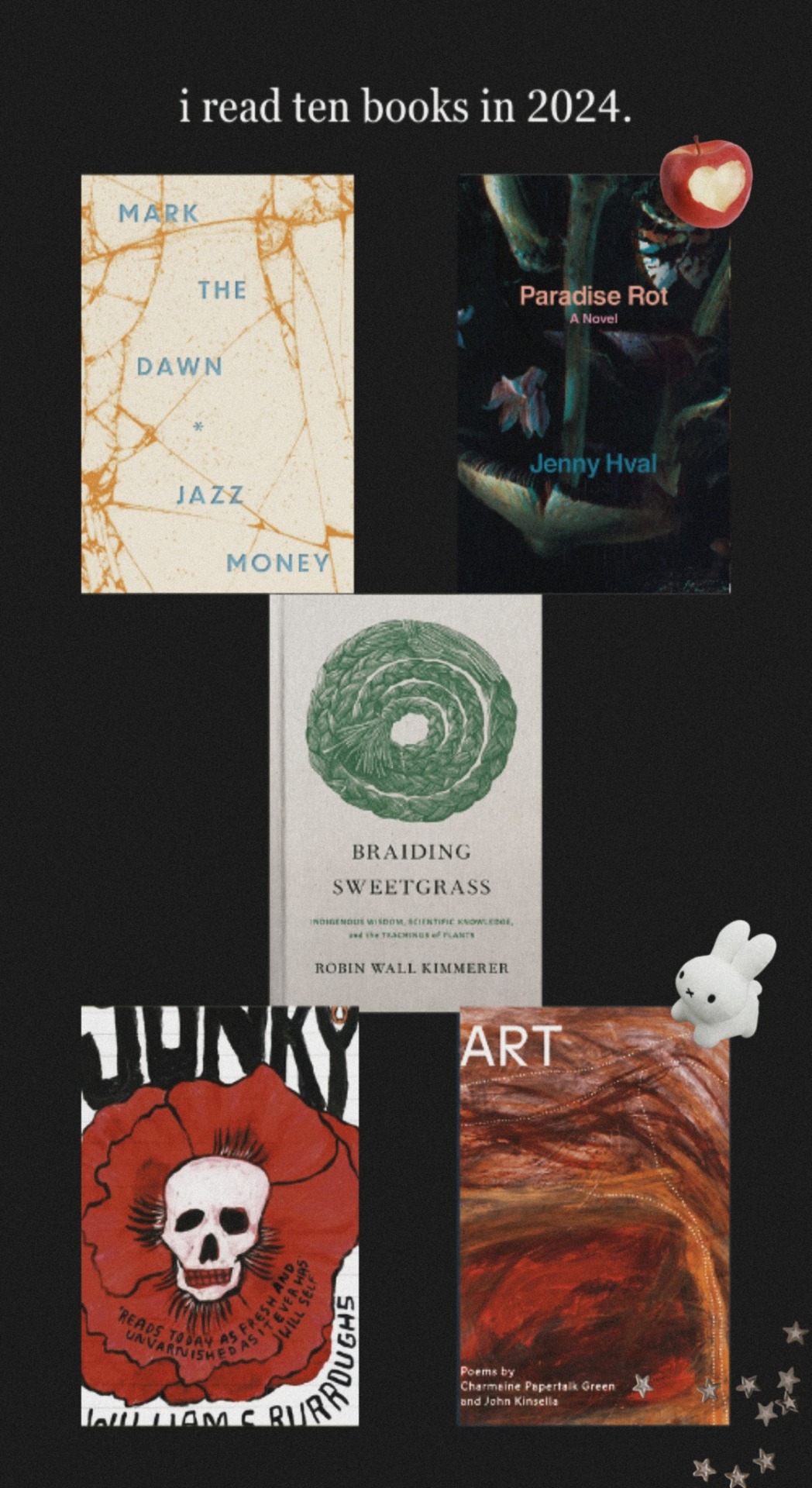

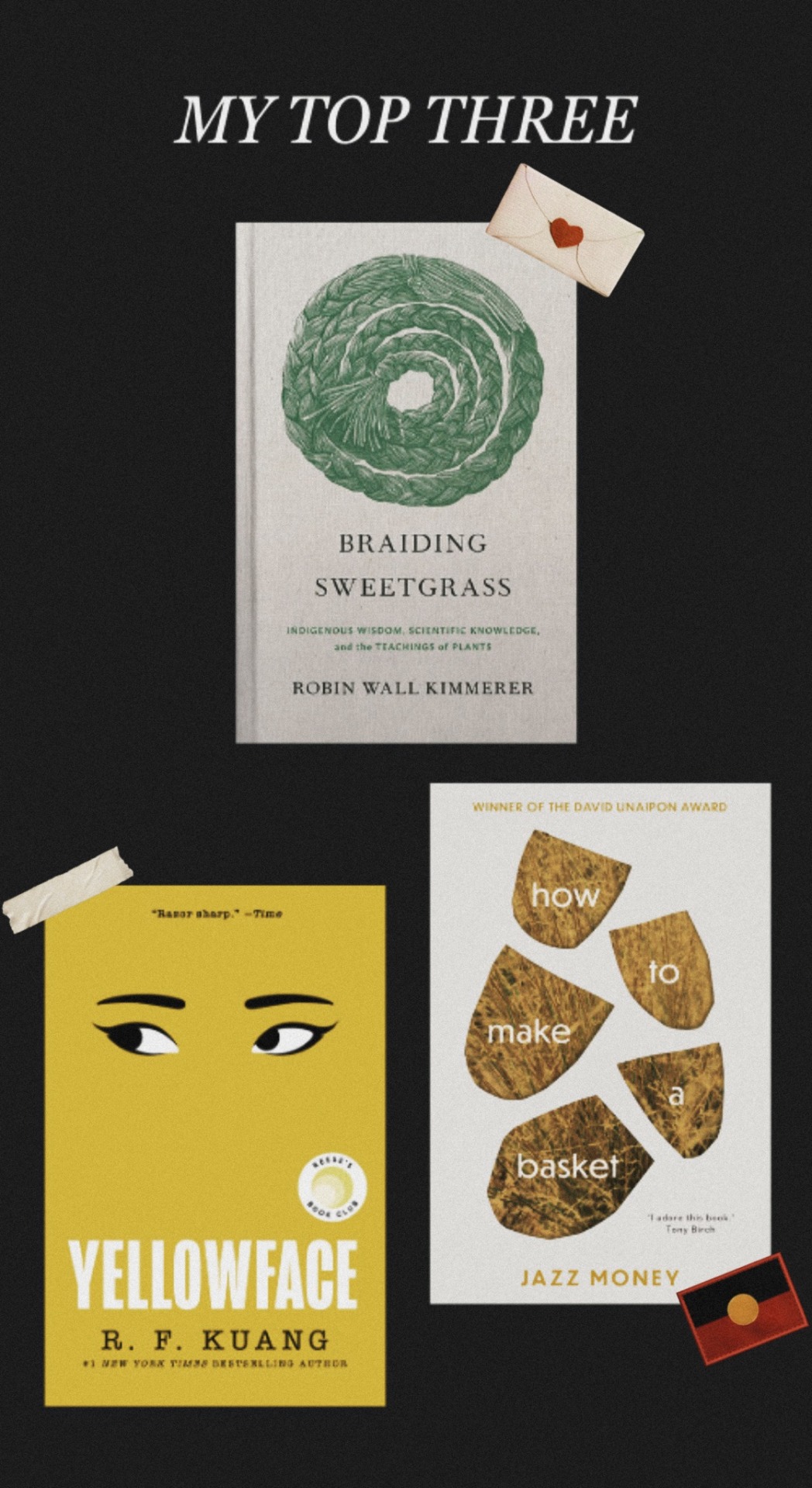

i read ten books in 2024!

while 10 may not seem like a lot- it genuinely helped me get into the habit of reading more regularly- my initial goal was five and i managed to double it, and also stopped using a star or number system to rate books, as i feel it is too volatile and a 3/5 means so many different things

#books#bookblr#book review#book#literature#lit review#2024 books#rf kuang#beat generation#william s. burroughs#pete wentz

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

im feeling batshit insane because im loving my lit review process, I fear I may be doing in wrong but why not have fun before we spiral?

#lit review#academics#grad school#grad student#graduate school#chaotic academia#dark academia#boku no hero academia

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Prom Queen was an exceptionally fun and bloody romp through Shadyside. It pulled off having a large cast of characters much better than many of its Fear Street predecessors, at least so far as the five prom queen candidates went. I can’t say the same for the boy characters; they all kinda blended together aside from being suspects. There are also some great examples in this book of how you don’t have to be a killer to be a total fucking creep. It was kinda funny how the students and parents were all anxious about the recent murders in Shadyside, as though murders don’t happen there all the time. It was also pretty ridiculous that the school would put on a play and do the prom on the same weekend. I mean, Shadyside is hardly a normal town, but maybe this was a tradition in some high schools. I can’t say for sure. It sounds like a logistical nightmare to me. In fact, I would say my biggest issues with the book were the baffling decisions made by the minor adult characters. I was pleasantly surprised by the twist at the end. That alone elevates this book for me. The plot may have followed a familiar Fear Street formula, but I felt like The Prom Queen was one of the best-executed books to use it.

Score: 4

Find my full review with spoilers snark, and memes over on my blog: https://www.danstalter.com/the-prom-queen/

#fear street#booksbooksbooks#books#book reviews#lit review#book revie#nostalgia#fits of nostalgia#rl stine#retro reads#90s kids#bookshelf#book photography#prom#prom queen#ya horror#horror#teen screams#teen horror#90s teens#paperbacks from hell

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

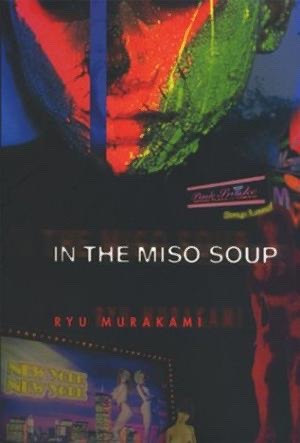

In the Miso Soup - Ryū Murakami (Review)

Summary: It is just before New Year’s. Frank, an overweight American tourist, has hired Kenji to take him on a guided tour of Tokyo’s sleazy nightlife. But Frank’s behavior is so strange that Kenji begins to entertain a horrible suspicion—that his new client is in fact the serial killer currently terrorizing the city. It is not until later, however, that Kenji learns exactly how much he has to fear and how irrevocably his encounter with this great white whale of an American will change his life.

Review: The first half of the book is a slow-rise build of unnerving tension. At moments, I had never felt such unease while reading something. The narrative kept me wondering, stringing me along while Kenji spirals to discover the truth behind his client’s nature. Only at the climax does the true horror of the situation finally and fully sink in. However, the events that unfold in the book’s last third feel dissatisfying. The dialogue that ensues may be thought-provoking, but the way it structures the story’s end left me feeling like something was lacking. Even so, I believe this book is an unforgettable experience due to its near-masterful grasp of creating suspense and thrilling the reader up to its peak of events.

3/5

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello there,

From the last post to now, life update is I'm pursuing PhD now. With confusion, self doubt, procrastination and at times taking pride in what I'm currently doing, I'm at that stage where I need to complete it. So here's me starting a 100dop to start that writing, to start those ideas flowing on paper or documents I've opened :D.

Because today is not day One but neither have I done much let's call it Day 4 of 100 dop :)

Note I won't go counting every next day but according to each day when being productive until I reach 100 as an attempt to be consistent.

Cheers<3

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What happened here? Are they lovers or mortal enemies?

#phd#lit review#trivers is super famous#don't know about brinkers but that isn't saying much#just thought those 2 titles right underwear each other were funny

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Literature Review as Academic Genealogy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

5-技術封建主義(雲主義)

核心內容主要在附錄。

一)資本主義如何生產財富和分配財富

I. 要素:

1價值-經驗價值+交換價值,2勞動- 經驗勞動+商品勞動,3資本-物質資本(即生產出的商品生產資料)+權力資本(即從不擁有資本的工人那裏榨取剩餘價值的權力) -- 由這些雙重性產生利潤與盈餘。

II.分配:

工資(反映商品勞動的交換價值;若低於交換價值,則差值轉化為雇主自留的壟斷租金)、利息(開始生產前資本家借貸來購買勞動力土地和資本貨物,支付給金融家的利息)、租金(買方支付的高於最能反映商品交換價值的價格的任何價格。普遍分類:金融地租-如股票房地產等 支付給金融家(如銀行家)、土地地租、壟斷地租、品牌地租)、利潤。

III.資本主義循環維繫:

利潤- 推動資本積累 + 私人債務(由金融家憑空創造)-允許在新一輪循環獲得利潤

IV.

1社會階級-中產易受擠壓;

2攫取權力類型:暴力、政治、軟權力(宣傳權力)、資本主義權力。

資本主義權力感染前三者,技術結構(新增勞動指揮服務部門+消費者指揮服務部門:旨在改變工人和消費者行為==專業化影響者市場(新型經理人)+注意力市場(吸引注意再出售給廣告商))加強資本權力。

二)資本主義與技術封建主義異同

異同:

雲主義:雲資本(網絡化機器、軟件、ai算法、通信硬件),煽動無薪人員(雲農奴)免費(無通常意識的)上傳更新雲資本庫(比如我在做的,以及被收集注意力記錄)。“利用ai和大數據指揮工廠車間工人勞動(雲無產者)同時驅動能源網絡、機器人、卡車、自動化生產線和3d打印機,從而繞過傳統製造業”。

雲資本,除了有資本物質+權力二重特性外,還擁有 行為修正和個性化命令的生產手段 這一特性。--消費者變為雲農奴,不穩定者和無產者變成雲無產者,雲封地取代市場。

雲資本,增加了一項剝削權:暴力、政治、軟、資本主義、雲資本所有者的剝削權。

雲地租和雲封地取代了利潤和市場。

“云资本的积累放大了导致严重资 本主义危机的两股力量:利润率下降和私人与 公共债务泡沫破裂。在技术封建主义下,劳动 力的非商品化(云奴隶劳动)与云无产者收入份额的

减少共同挤压了社会的总支出能力或总需求。同时, 附庸资本家向云端资本家输送更多剩余价值,减少了 对地面资本的投资;这是对总需求的另一个负面影响。”

--接下來結合全書概括--

演化過程:封建主義-資本主義-建立與雲技術、雲地租大過利潤的 技術封建主義。

三)現狀:

歷史關鍵事件:資本主義演化���期:巨型企業信貸潮 製造泡沫-布雷頓森林美元中心-尼克松衝擊布雷頓瓦解 金融危機

技術封建主義時期:谷歌等雲數據資本+蘋果apple store開啟雲租界(“新圈地運動”)-區塊鏈民主化貨幣失敗 - 俄烏戰爭美國中央銀行扣押俄羅斯1500億款額 -美國限制中國分享其租地(如 取締安卓系統於華為)- 中國雲資本巨頭,另一方面一帶一路等成為亞非甚至歐洲主要投資國 減少對地下合約的依賴-形成中美兩大租地

四)how all these work,雲or 實地:

以美元對黃金為匯率基準,進出口順逆差,“彌諾陶”巨獸與浮士德魔鬼條約:美國對_保持逆差而_國用此逆差帶來的利潤去投資美國FIRE華爾街或其允許的金融衍生品。

區塊鏈:跳過銀行貨幣

中國中央銀行直接發行的數字貨幣:跳過美元匯率兌換。(關於此,我不明白其他國家如何購買中國中央銀行數字貨幣)

四)作者的藍圖

0 notes

Text

The child may then cover over the resulting loneliness, emptiness, and sense of ineptness with a fantasy (often unconscious) of self-sufficiency. Love and anger get hopelessly intertwined. Fairbairn argued that the tragedy of schizoid children is that their conscience has been warped: they believe it is their love, rather than their hatred, that is the destructive force within. Love consumes.

Treatment of schizoid personality: an analytic psychotherapy handbook Zachary Wheeler

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary: Chapters 5-7 of Critical Intersex

After our first foray into academic intersex studies, people were curious for more, so for November we read a subset of the edited volume Critical Intersex. It was published in 2009 and was edited by Morgan Holmes, an intersex sociologist. We read Chapters 4-7.

As it turned out, Chapters 5-7 were all fairly similar - they all went over the modern-era history of intersex from a legal/bureaucratic perspective in The Netherlands (Ch 5), and Germany (Ch 6 & 7). Chapter 4 was on the history of the Intersex Society of North America.

We’re gonna split the book/discussion summary into two posts - this one for Chapters 5-7 and a separate post for Chapter 4.

First, some quick summaries of the chapters:

Ch 5: Do I Have XY Chromosomes? By Margriet van Heesch

This chapter provides a history of how AIS has been treated by doctors in the Netherlands from the 1880s to the 2000s. Treatment models changed several times during this time period, affected by shifting scientific understanding of the basis of sex as well as social changes in the late 20th century towards greater informed consent

An important shift happened in the 1960s: a new treatment model for intersex emerges, led by John Money at Johns Hopkins University in the USA. This posits that gender identity is a result of genital appearance and parenting in the early years’ of an infant/toddler’s life. They believed that the clinical goal should be to “erase all doubts about the sex of children with intersex conditions” (p123)

All three of the chapters talk about this paradigm, but none of them use a pithy name for it. As it turns out there is a name for it; its practitioners called it the optimum gender rearing model, or OGR model.

Heesch explains how the OGR model led to a dynamic where Dutch doctors would “protect” AIS women from learning that they have XY chromosomes. Women would AIS would still sometimes find out, by accident or through a lot of digging, and Heesch’s chapter focuses on interviews and life stories of women with AIS who were treated this way.

Interestingly, John Money himself argued “‘in all cases of genital deformity, whatever the diagnosis and whatever the rearing, it is psychologically advantageous to be straightforward and honest in talking with the child about the facts of his or her condition’” (p 133) - emphasis ours.

This part of Money’s treatment model did not make it into Dutch practice. Money was fairly accepting of homosexuality, whereas Dutch doctors openly declared a “wish to make intersex children into happily married adults … Medical prevention of homosexuality became disguised as the medical prevention of social problems.”

Heesch also interviewed women with AIS and relays their life stories. The stories are fairly grim and the usual sorts of stories about AIS (e.g. removing “cancerous tumours”). Notably, the women who did find out about being intersex expressed a desire to meet other women with the same condition (p138) in contrast to doctors’ approaches to hide information and connections from their patients.

Ch 6: Intersex, a Blank Space in German Law? By Angela Kolbe

In Germany, “there is no law to define what a man is, what a woman is, or how many sexes exist. the legal system simply assumes an obvious distinction between male and female, and structures laws to acknowledge only two sexes.” (p147)

As such, you cannot register a baby as as intersex, rather than female or male, on a birth certificate.

Interestingly, German law used to include a category for altvil, which Kolbe translates as “hermaphrodites”. The altvil were in German law as early as the Sachsenspiegel of 1230. The Sachsenspiegel encoded that “hermaphrodites, dwarfs and imbeciles could inherit neither land nor titles” (p149).

Kolbe then goes over a history of different laws and what they had to say about intersex people. Overall the picture is that intersex people had more limited rights than perisex people. Multiple historical laws set forth a “preponderance rule”, to assign intersex people to a binary gender based on the preponderance of sex characteristics; these laws encoded who was to make this determination and when.

Some laws (such as a law in 1794 Prussia) granted a right of choice: the intersex person (or their parents) could choose which binary gender they should be, and make a blood oath binding them to this gender. (Some laws penalized breaking this oath.)

After going through the history, Kolbe then explains the present situation in Germany. The legal challenges from intersex people, and the unwillingness of the German government to deal with it.

Kolbe describes a court case in Colombia that set a new standard: they denied the parental right to consent to surgery on intersex infants. “The court found that the parents did not really understand the implications of the operation on their child’s life.” (p159) and created a new model of “qualified and persistent informed consent”.

This Colombian model was a compromise between abolishing infant surgery and allowing parents to consent to surgery on behalf of their children - it required doctors to provide detailed information to parents, and it needs to be authorized in stages that are spread out to give “parents time to establish bonds with their child the way s/he is, and not to make a prejudicial decision based on shock at the baby’s appearance” (p159)

Kolbe discusses the Colombian model as a possible way forward for Germany, and then discusses other possible ways forward for Germany - should they make a legal third sex category? Or try to abolish gender categories in the law entirely? Kolbe details how gender is currently involved in German law and how it could be removed.

Ch 7: Who Has the Right to Change Gender Status? Drawing Boundaries between Inter- and Transsexuality by Ulrike Klöppel

In post-war Germany, the standard was to let intersex people pick their gender assignment - for infants with ambiguous sex at birth, they were given a provisional assignment. There was a clear commitment to defer plastic and hormone surgery until the intersex patient could decide what they wanted.

Klöppel documents how the “subject orientated” policy emerged in the early 1900s. Klöppel gives a history of medical treatment models in Germany, and how the subject-oriented model eventually lost out to the OGR model promoted by John Money.

Klöppel then provides a history of how trans people have been understood by German doctors, and common ground in how both trans and intersex were negatively impacted by laws that required all Germans to have a binary and unchangeable legal sex marker.

Klöppel discusses the role doctors have played in pushing back on these laws, the relationship between the law and medicine, and the history of relevant legislation in Germany in the 20th century.

Shifting now into our book club discussion...

High-level Reactions To These Chapters

Elizabeth (Eliz): I already knew the basic timeline of the social construction of sex, so that wasn't new to me. But it was new to me that the Netherlands and Germany would be so different. The doctors lying to their patients was really something. And then the Germans being like, "yeah, the intersex person gets to pick their gender!" I wasn't expecting such differences between such similar countries.

Michelle (M): I come from a medical family background, so medical ethics are familiar to me, but the concept of simply not telling a patient what they were diagnosed with is horrifying to me.

ei: i honestly didn't read very much, and there wasn't anything in particular i wanted to discuss. mostly just interested in listening in on you guys' discussion!

Doctors

Eliz: The chapters were emotionally difficult to read; reading about doctors being paternalistic is never fun. It was interesting that John Money, the guy associated with infant surgeries, advocated being open and honest with the intersex children and what had happened to them. I still don’t know what tests were done on me as an adolescent and it’s been a barrier in my care to this day.

Eliz: Another thing about the chapters is the importance physicians have on surveilling intersex people. The DSD model frames intersex as a lifelong model that requires surveillance and intersession by a team of healthcare workers.

ei: doctors HATE when intersex people are queer or trans or "weird" in another way. They expect us to all be cishet and as "normal" as possible, and that ofc includes forcing "treatments" to erase our intersex traits! I hate when i look up my variation and get hit with "men with (variation)"

Eliz: yeah doctors have appointed themselves into the job of surveilling intersex people to make sure we never deviate

M: it's gender as a police state. "You're already a recidivist. Don't you dare worsen your condition!" It's probably why doctors hate when patients band together in case "these intersex people get wrong ideas."

ei: yeah. my gender has always been seen as a medical issue, specifically one to be "corrected". i've fought consistently against so many medical "treatments" that are meant to make me more similar to a perisex person

Eliz: yeah I noticed how in one of the chapters (Ch 5) the author was like “why didn’t the doctors tell the patients how to connect with people with the same condition?” given all the evidence it’s beneficial for intersex people to do so, and how the people that author had interviewed had - upon finding out they were intersex - immediately wanted to meet others with the same condition. I don’t know if the author had been asking rhetorically but it feels like the answer is because doctors are scared if we talk to each other we might realize we’re being mistreated.

ei: I think also, they don't want intersex people to feel like their variation is okay. they want to maintain the Medically Fucked Up narrative, and they don't want us meeting other intersex people because we might realize that being intersex is normal, natural, and okay.

Eliz: yeah doctors don’t want to give up control. I liked this line in Ch 6: “in current legal and political developments the issue of intersexuality, although still quite unknown, has stepped out of the silence into which medical science had banished it”

Ableism and Eugenics

Eliz: I thought the link between intersexism and ableism going back so long was fascinating. Like how in the 1200s, people who were intersex or disabled couldn't inherit land.

M: And like, with intersex people, I think there's a fear that - forgive the ableist language - we could "breed more freaks!"

Eliz: it’s super eugenicist

M: It always comes back to eugenicism!

Surveillance and Technology

Eliz: these chapters have a big theme of surveillance. The DSD model putting doctors in the role of surveilling us intersex people to ensure the conformity of our genders and sexual orientations. And this was interesting for me because that this isn't the issue I'm used to thinking of when it comes to surveillance and intersex. So many surveillance technologies like facial recognition or whatever assume a sex or gender binary, so technologies don't work right on intersex people because they're not designed for us. There's just ways in which a lot of technologies assume a binaristic, dyadic view of humanity that are quite hurtful.

Eliz: Chapter 7 reminded me of this paper I have really ambivalent feelings about, by a Science and Technology Studies (STS) named Mar Hicks. The paper is about how the computerization of the British Census made gender more difficult. For a long time, you could write whatever gender you wanted, and no one could reaaaally keep track. So if you transitioned, and presented yourself as a new gender when you moved, there weren't really birth certificates; people just had to take you at your word. The paper shows how technology changed this. I have mixed feelings about Hicks’ paper because there is zero mention of intersex people in it. Hicks is trans. It’s really frustrating to me how intersex people just don’t exist at all in the minds of perisex people, and this is a really frustrating oversight in Hicks’ work.

Questions about the authors

Eliz: I did wonder how many of the authors of the book chapters were intersex; they read more perisex because of referring to the intersex community with "they" and "them" language instead of “our”. If the authors of these three chapters were intersex they were doing a weird pretend-distancing thing that I dislike seeing in academic writing. It's also possible that the book wasn't as intersex-authored as you'd expect from the title.

M: not me forgetting that academic textbooks have multiple authors!

Eliz: I don't know why so much of this scholarship is German! More Germans! Why? But I'm fascinated. What led to Germans being the leaders on intersex studies?

Jurisprudence, law, and politics

Eliz: Thinking of the chapters that were saying in the premodern era intersex people were just asked to decide what they gender wanted to be, and do a blood oath, like "this is my gender now!" As opposed to slotting you into female or male FROM birth, and experts need to be called in on which way you're going to go. The emphasis on trying to predict gender from birth feels so deeply counter productive. And because it’s so flimsy it requires all this extra work to enforce it.

Eliz: The Columbian compromise was surprisingly reasonable. There were still surgeries on children, but it was more acceptable, so I was kind of impressed. Good job, legal jurisprudence system.

M: You were adequate!

Eliz: One thing -getting more into ch 4 - there are a handful of countries that have banned intersex surgeries - like Greece - and I'm really curious to know how that happened, especially after ch 4, about the history of American intersex activism. What happened in Greece and Spain that was successful, in a way that hasn't been in these other countries, is something that I'm really itching to find out.

Germany

M: My feelings about the chapters were that there was a real simmering fury about sexual binarism in Germany. It seemed like a good opportunity for nonbinary and intersex people to have kinship and allyship there. I've come to identify more as a nonbinary person; I've always hated the word "woman," and that feels very connected to my intersexuality.

Eliz: there was this idea in the chapter that intersex people were just casualties of sexism that I didn't really like. I would have liked a lot more about the path forward with an X or I marker, rather than just removing gender categories altogether. I was also a bit "ehhhh" about the author dismissing Affirmative Action?! It's controversial, people don't like it, but it works! I felt that needed to be fleshed out more

Eliz: By the way, I looked it up, and Germany did legalize same-sex marriage in 2017.

M: that feels late!

ei: crazy that people think europe is like so progressive but then germany didn't even legalize gay marriage until after the united states

Germany since 2009

Bnuuy, who is German, gave us a very detailed update on what has happened in Germany since the book was published in 2009. Here’s a very brief summary of Bnuuy’s infodump, which you can read in the #23-11-critical-intersex channel on our discord:

Some court cases led to the courts ordering changes to the system to improve things for trans/intersex people, but German legislators absolutely failed to uphold the spirit of the constitutional rulings. The politicians have created a system that does the bare minimum of what the court ruled that in practice makes it incredibly difficult for trans & intersex people to change their gender markers.

Legal sex marker change for trans people still requires sterilization and to sue to have a court recognize your gender change. The government is not allowed to out you as trans if you go this route. Whereas if you go the pathway intended for intersex people, this right isn’t there; the government can out you as intersex.

The intersex pathway to sex marker change requires a doctor to write in your favour, and the government can’t check it. A diagnosis is required, and it’s not even for “intersex”, it’s for the German translation of DSD.

So a lot of trans people use the intersex pathway, since the doctor can write down ANYTHING to make it count as “intersex”. For nonbinary people it’s a real roll of the dice in the courts, and generally easier to go the route of “intersex”. It’s a super broken system.

Bnuuy conveyed a deep feeling of frustration with German politicians for failing to do right by their trans & intersex constituents, and the frustration in more progressive politicians making big promises to fix the system and then not delivering at all.

Bnuuy also had an important PSA to make which is when you hear news that a foreign country has made some legal/political victory for queer people actually read about it - too many people see that Germany has blank and “diverse” on the books for gender markers and think these options are actually available to genderqueer & intersex people, but they’re not actually.

Our discussion continues here for chapter 4.

#intersex#intersex studies#queer theory#intersex book#gender studies#sociology#legal studies#book reviews#book summaries#intersex rights#lit review#critical intersex

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wrote so much today for my assignment but I feel like I’ve still nothing at all 😩

0 notes

Text

The Echo of An Echo: Exploring Queer Themes in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Olalla”

“It was his mind that puzzled, and yet attracted me...”

This story is not one of Stevenson’s that I was interested in or even knew about before I started my research, but I quickly realized that this was a very queer story. In this post, I will be reviewing the story, providing analysis, and arguing the following:

Through the use of gothic tropes like familial & emotional degeneracy, derelict settings, and the homoerotic triangle between key characters, “Olalla” expresses that both experiencing and repressing queer desire results in the same fate in the Victorian Gothic: danger and destruction.

This story begins with a sick Scottish soldier discussing his condition with his doctor. The doctor recommends that the soldier turn to Spain to take respite from his injuries, soon recommending a stay at a home owned by a formerly noble family.

“[T]hey were once great people, and are now fallen to the brink of destitution. Nothing now belongs to them but the residencia, and certain leagues of desert mountain, in the greater part of which not even a goat could support life.”

If you know anything about the Gothic genre, you know that dereliction, destitution, and decay are three common “D words” when it comes to settings of stories in the genre. The residencia (Spanish for home or residence) is also placed in a normally Gothic setting: Southern Europe. The idea of the residencia being in desert and being unable to support any life, much less the one of a goat, is of particular interest. I asked myself then, how could the Senora and company live there? Numerous other stories, including the ones of Vernon Lee, are set in Southern Europe, primarily because of the associations that region had with homosexuality, loss, and dereliction. It also seems to allow for the displacement of British issues to a “foreign” soil, firmly keeping issues out of the “pristine” British culture.

However, when the soldier is told of the residencia that he will be living in, he seems to express interest into it, and the doctor provides him with more information about the inhabitants, a family of three: the Senora, Felipe, and Olalla. It is expected that the narrator will remain a stranger to them, primarily because of their seeming “plainness” as described by the doctor. However, the doctor goes on to describe the family as such:

“The mother was the last representative of a princely stock, degenerate both in parts and fortune. [...] Then, much of the fortune having died with [her father], and the family being quite extinct, the girl ran wilder than ever, until at last she married, Heaven knows whom, a muleteer some say, others a smuggler; while there are some who uphold there was no marriage at all, and that Felipe and Olalla are bastards.”

Ultimately, it isn’t known for sure what happened to the father of the family, even some of the old priests are unsure. But, the existence of the phrase “degenerate both in parts and fortune” seems to imply some form of sexual, physical, or cognitive difference, perhaps an intersex character. It also appears that she is hypersexualized given that she went “wilder than ever” following her father’s death. This seems to lean into the degeneracy part of the story. Because of this, the doctor continued to insist that the narrator should not “romance” at the residencia.

Soon though we are introduced to Felipe, the “quasi-patriarch” of the derelict residencia. Felipe is also seemingly “degenerate”, but perhaps less so than the mother, and it is apparent that he is unable to make full sentences, or even words, and the narrator reflects on this:

“The lad was but a child in intellect; his mind was like his body, active and swift, but stunted in development; and I began from that time forth to regard him with a measure of pity, and to listen at first with indulgence, and at last even with pleasure, to his disjointed babble”

To make the post shorter than it is, please click below to keep reading!

This seems to imply that there is some form of homoerotic attraction between the two, particularly because he finds “pleasure” in listening to Felipe. After arriving at the residencia and setting up shop, the narrator sees a portrait. The portrait, as it seems, bears a resemblance to Felipe, which is a peculiar connection that the narrator realizes. He finds this resemblance rather unsettling, and it seems that the pleasure is replaced by discomfort. He says the following:

“Something in both face and figure, something exquisitely intangible, like the echo of an echo, suggested the features and bearing of my guide; and I stood awhile, unpleasantly attracted and wondering at the oddity of the resemblance”

Clearly, the narrator is not comfortable with this implied homoerotic attraction, but does not dare to go against it; that being said, he later says the following:

“[M]y eyes continued to dwell upon [the portrait] with growing complacency; its beauty crept about my heart insidiously, silencing my scruples one after another; and while I knew that to love such a woman were to sign and seal one’s own sentence of degeneration, I still knew that, if she were alive, I should love her. [...] She came to be the heroine of many day-dreams, in which her eyes led on to, and sufficiently rewarded, crimes”

This is where I see the formation of the first of two homoerotic triangles within this story (if unfamiliar, the post where I describe the homoerotic triangle is here); the second involves Olalla, Felipe, and the narrator. However, I argue that the “crimes” in question involve autosexual urges, like masturbation and self-pleasure, and because of these pleasures coming through the portrait, they are also associated with queer desire for Felipe. The face of Felipe and the Senora seems to be duplicated, which is a symptom of incest, which is what the degeneracy position could be leaning into.

But, the relation with Felipe would increasingly become homoerotic in the coming days of the narrator’s stay in the residencia, notedly the following:

“[H]e loved to sit close before my fire, talking his broken talk or singing his odd, endless, wordless songs, and sometimes drawing his hand over my clothes with an affectionate manner of caressing that never failed to cause in me an embarrassment of which I was ashamed.”

Seemingly, this is a quote that speaks to the repression of the queer eroticism that I got at during the first part of this post. However, it does seem that this became a frequent thing, not just a one-time thing, and that the narrator enjoyed these caresses because he did not actively try to stop them. Even if shame was such a potent feeling for the narrator, pleasure came through rough emotions.

We must not forget that there was a second triangle and that queer anxieties were still present in the story throughout, especially when it came to choosing who the narrator loved the best or preferred, with him even writing that of the two (i.e., Felipe and the Senora), he preferred the Senora and liked her the best. However, the existence of this comparison seems to imply that he liked them both in a dubiously worded way, perhaps romantically, sexually, or platonically. But, it may also seem that he is trying to protect himself from allegations of homoeroticism by placing his desires somewhere safer, like onto a woman. It is up to interpretation.

That being said, the Senora had a similar pleasurability to the narrator than Felipe did, and he soon describes it as the following:

“I had come to like her dull, almost animal neighbourhood; her beauty and her stupidity soothed and amused me. I began to find a kind of transcendental good sense in her remarks, and her unfathomable good nature moved me to admiration and envy. The liking was returned; she enjoyed my presence half-unconsciously, as a man in deep meditation may enjoy the babbling of a brook”

I don’t truly know if the narrator actively sought out the Senora in the same way as he did Felipe or Olalla, but there could be evidence that he used both of the women as objects of affection that funneled affections for Felipe away from him. However, he does describe the woman with animalian terms in this above passage, which sort of adds to her docility and lack of active affections. I will discuss the possibility of the objectification of the women later.

With that said, there is a sense of potential sexual activity between Felipe and the narrator. The narrator writes:

“By the time Felipe brought my supper and lights, my nerve was utterly gone; and, had the lad been such as I was used to seeing him, I should have kept him (even by force had that been necessary) to take off the edge from my distasteful solitude”

What the narrator wanted to do with Felipe, I do not know, but it appears that there must have been a sexual aspect, perhaps one of coercion, to their relationship. Forcing Felipe to stay with him seems both romantic but also problematic for the narrator, and it sort of sheds light on the bond the two had built together. It does seem, however, that the narrator could be in denial about his feelings, as he writes later about an interaction with Felipe:

“I took his hand in mine, at which, thinking it to be a caress, he smiled with a brightness of pleasure that came near disarming my resolve.”

I truly think that this is one of the closer moments we reach homoerotic tensions bubbling over between the two. The narrator has made it abundantly clear that he enjoys the pleasure and happiness that Felipe exhibits around him, so it would make sense that following that logic, he could be more likely to lose his “resolve” to stay heterosexual exclusively with the pleasure that comes from Felipe. The repression of those homoerotic desires seems to be what he searches for as his primary resolution and he’s trying to desperately keep his facade of being heterosexual, but simply isn’t able to, even if funneling affections through two women.

Eventually, Olalla must step into the picture here as well. Felipe is good and all, but it appears that his relationship and enjoyment at the residencia comes from his meeting with the hermetic Olalla:

“My foot was on the topmost round, when a door opened, and I found myself face to face with Olalla. Surprise transfixed me; her loveliness struck to my heart; she glowed in the deep shadow of the gallery, a gem of colour; her eyes took hold upon mine and [bound] us together like the joining of hands; and the moments we [..] stood face to face, drinking each other in, were sacramental and the wedding of souls”

I like to argue that Olalla looks a bit better than the Senora and Felipe, because she has the first glowing review from the narrator of the entire family. She’s a “diamond in the rough” to the narrator, a gem of color. Already, it seems like the narrator is ready to marry and disappear with her. With that in mind, the resolve of the narrator comes back into view, and that his transfixing on Olalla perhaps a displacement of his feelings for Felipe:

“I swore I should make her mine; and that very evening I set myself, with a mingled sense of treachery and disgrace, to captivate the brother. Perhaps I read him with more favourable eyes, perhaps the thought of his sister always summoned up the better qualities of that imperfect soul; but he had never seemed to me so amiable, and his very likeness to Olalla, while it annoyed, yet softened me.”

Here, we have a displacement of the love for Felipe onto Olalla and vice versa. Personally, I think this truly indicates that the narrator’s only focus is to be one of Felipe’s affections, especially because Olalla is so beautiful herself. Perhaps, though, the narrator is trying to lean into polygamous desires and wants the both of them. However, the love of Olalla and Felipe is shortened throughout the latter half of the story, and Olalla has some closing remarks to the narrator:

“Think of me sometimes as one to whom the lesson of life was very harshly told, but who heard it with courage; as one who loved you indeed, but who hated herself so deeply that her love was hateful to her; as one who sent you away and yet would have longed to keep you for ever; who had no dearer hope than to forget you, and no greater fear than to be forgotten.”

This quote is particularly important to me because it showcases that the erotic desires of the narrator seemed to be in vain, and that both queer and heterosexual desires are ones of fragility and can be fallen in a sudden strike of the proverbial hand; this quote speaks to me as one of cautionary failures of the narrator. By failing to captivate either Olalla or Felipe, the narrator is left behind without either of them, ostensibly only wanting to have Olalla. The narrator’s exile seems to be important, and it may signal that queer people were unable to fit into the rigid family structure of the Victorian period, and that the exile was an inevitable result of transgression from traditional family structures.

Analysis:

Through these quotes and numerous others, it appears to me that there are many aspects of the queer Gothic within this story:

Because of the dubious sexual nature of the story, it seems that a lot of the queerness from this story stems from non-sexual romantic escapades. The existence of the homoerotic triangles provides detail and mystery to this story because it allows for room for interpretation. The Felipe-Olalla-narrator triangle seems to stem from degeneracy and familial incest, because Felipe and Olalla look the same.

However, it must also be noted that the degeneracy of the location of the story, a tucked-away old castle house, seems to be a result (or perhaps cause of) the degeneracy of the family. The Gothic worldwide seems to lean into these degenerate themes by allowing for stories to fix themselves within the genre, take those themes, and run with them.

I would also like to note that I think the triangles between the family members and the narrator are also a symptom of this larger degeneracy, and that the relationship between Felipe and the narrator is seen as “degenerate” as a result.

I also posit that the ending of the story, with the forcing of the narrator to leave the residencia, also stems from the degeneracy of his volition; he seems to be unable to fend for himself and argue on his behalf, therefore allowing his volition to implode.

He so clearly wants to live with this family, and love them, but Olalla insists, and he acquiesces to this request without seeming to put up a fight; this may signify his emotional degeneracy. Perhaps he has been too blase to see that the family will eventually get rid of him, perhaps he’s locked behind queer sorrow and shame for what he has done while at this home, or just perhaps he is ashamed that his queerness, which has been so repressed, is unable to work within his “family.”

#queer#theory#queer theory#queer lit#queer literature#victorian#queer victorian#gothic#queer gothic#victorian gothic#literature#writing#literary criticism#literature review#lit review#robert louis stevenson#olalla#english literature#book blog#story review

0 notes

Text

currently on day 2 of trying to hit my 4-article-a-day goal. but having to analyse articles after 8 hours of teaching is just painful.

0 notes