#Lehrstück

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Russische Soldaten

im Kampfeinsatz

in einem erbeuteten

-> US-Bradley - !!!

https://rumble.com/v5ovv3b-trophe-im-einsatz-us-panzer-bradley-im-dienst-der-russischen-armee.html

#russland#deutschland#ukraine#usa#nato#eu#ukraine krieg#amherd#ukraine-krieg#bradley#kriegstüchtigkeit#kriegstauglichkeit#schweizer armee#süssli#selenskyj#selenskyi#lehrstück#pistorius#bundeswehr#schweiz#taurus#merz#friedrich merz

0 notes

Text

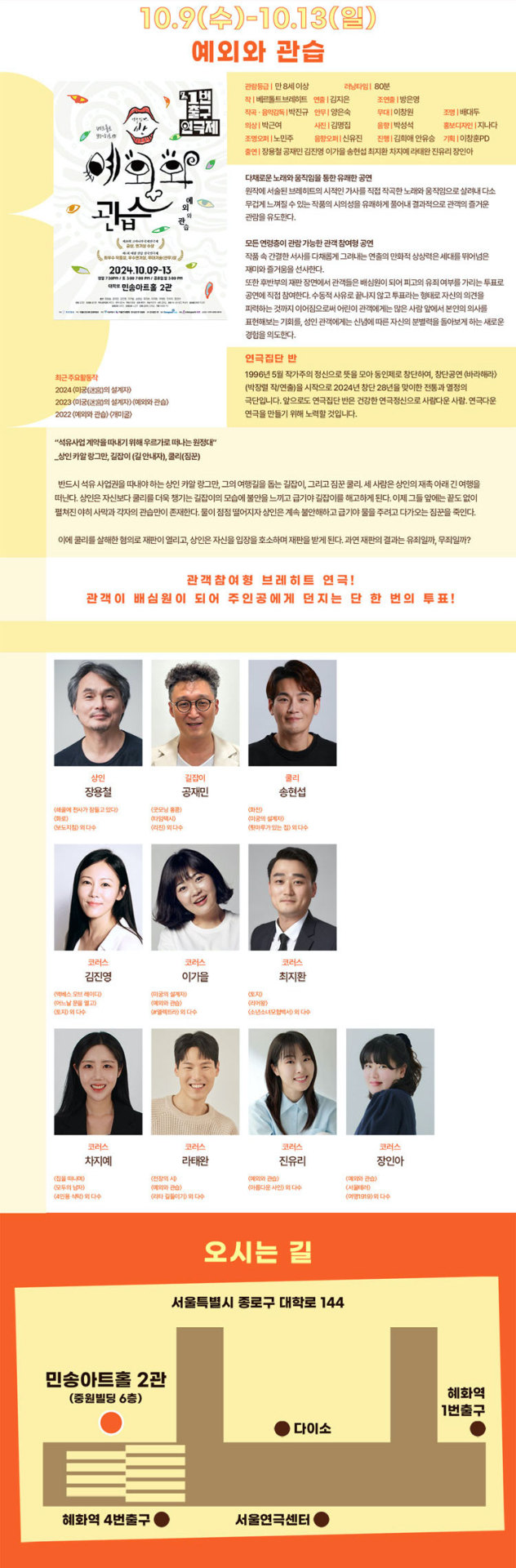

2024–10–09 ~ 13 민송아트홀

예외와 관습

예외와 관습 (1번출구연극제), 연출: 김지은, 출연: 장용철, 공재민, 송현섭, 김진영, 이가을, 최지환, 차지예, 라태완, 진유리, 장인아, 조연출: 방은영, 작곡/음악감독: 박진규, 안무: 양은숙, 무대: 이창원, 조명: 배대두, 의상: 박근여, 사진: 김명집, 홍보물 디자인: 지나다, 음향op: 신유진, 조명op: 노민주, 진행: 김희애, 안유승, 기획: 이창훈, 제작: 연극집단 반, 주최: (주) 다컬쳐, 주관: 1번출구연극제 집행위원회, 후원: 서울특별시, 서울연극협회, 연극집단 반 후원회, 협찬: Dongwon F&B, 장소: 세명대학교 민송아트홀 2관, 2024년 10월 9일 ~ 13일 (평일 19:30pm, 토 15:00, 19:00, 일, 공휴일 15:00), 이장료: 30,000원(전석), 문의: 070-4355-0010, 예매: via Interpark

0 notes

Text

Hab gerade nochmal an Staffel 25 gedacht und daran, wie gut das Writing war und wie sie darin mit einigen Schloss Einstein Klischess gebrochen haben

Julia und Colins Story scheint anfangs eine typische "Friends to Lovers" Story zu sein, wird dann aber zu einem Lehrstück über Amatonormativität (später dann auch Heteronormativität) und darüber, dass platonische Liebe genauso intensiv sein kann wie romantische Liebe.

Im Gegensatz zu anderen Story, in denen Charaktere Problem mit ihren Eltern haben, endet Joyces Story nicht mit einer Versöhnung sondern mit einem Kontaktabbruch und der Erkenntnis, dass Familie nicht nur aus Blutsverwandtschaft besteht.

Es wurden zum bisher einzigen Mal die Probleme von Abiturient:innen beleuchtet, obwohl Leute in dem Alter eigentlich nicht mehr zur Zielgruppe gehören.

Sirius trägt Nagellack und einen pinken Schlafanazug, was aber nie angesprochen wird. Es ist einfach normal. Im Gegensatz zu den "Haha, ein Junge hat ein Kleid an!" Storys in der Vergangenheit.

Das Theatermodul war zwar das Hauptthema der Staffel, hat aber allen Storys trotzdem genug Raum gelassen, um sich zu entfalten. Selbt denen, die nicht darin involviert waren. Für den jüngeren Teil der Zielgruppe gab es stattdessen Nesrin und Annika mit ihrem Pranks.

Hermanns Ausstiegsgeschichte ist immer noch eine meiner liebsten Ausstiegsgeschichten, einfach, weil sie so eine tolle Message sendet - Dass man seinen eigenen Weg gehen und machen soll, worauf man selbst Bock hat, auch wenn die Erwachsenen was anderes für einen geplant haben.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The defining works of Brechtian epic theater – such as The Threepenny Opera, Mother Courage and the Lehrstücke, among others – are collective productions; yet these texts have been subsumed into the life work of one person and “Brecht” has come to stand in for an author like many others. Even against considerable active and passive resistance from subjects’ own attempts to create meaning and a narrative and their writing practices, individual authorship is reproduced. The institutions of publishing, literary scholarship, biography and journalism all have stakes in producing Brecht as an author like other authors to solve their particular problems of coordination and strategies of reproduction. For the collaborators this contributed to their alienation. Their work came to confront them as something external and their recognition by others was mediated through the construction of “Brecht.” Is this alienation inevitable? How could authorship be more in tune with actual writing practices? Authorship is institutionally firmly entrenched and in order to formulate and identify oppositional projects, it is not enough to simply deconstruct authorship or try to undo it by unconventional writing or reading practices. It is worth investigating more closely in these terms how the relationship between practices and authorship has changed historically and in particular in the last decades. Has authorship become more democratic? Here, I can only hint at some of the developments worth considering. The gender inequalities in the literary field that have made possible the Brechtian workshop seem to have lessened. Women today find it easier to publish on their own and access to stages may be more open to female playwrights. The prominence of Sarah Kane, Carol Churchill and Elfriede Jelinek bear witness to the new possibilities that have opened up for female playwrights." - Monika Krause, Practicing Authorship: The Case of Brecht’s Plays

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dass Pubertierende in dem für die Pubertät so kennzeichnenden Widerspruch der Sehnsüchte nach Individualität und Zugehörigkeit sich der gängigen kulturindustriell verwursteten Identitätsschablonen bedienen, die eben mit dem Charakter der Besonderung, der (vermeintlichen) Rebellion gegen gängige Ordnungen und gleichsam mit dem Versprechen einer Zugehörigkeit in ähnlicher sinn- wie identitätsgebender Funktion (früherer) Subkulturen die Auflösung des Widerspruchs genannter Sehnsüchte versprechen, ist im Grunde gewöhnlich und legitimer Ausdruck pubertären Ringens um das Selbst. Wenn aber daueradoleszente Erwachsene jene geschlechtsbezogenen Identitätsschablonen in albernen Ermächtigungstänzchen aufführen und diese noch mit allerhand Pseudomoral und abgedroschenem Praxisfetischismus überziehen, dann ist das kaum an selbstgerechter Peinlichkeit zu überbieten. Aber es ist ein Lehrstück darin, wie die Subjekte mehr denn je in den bedrückenden gesellschaftlichen Verhältnissen Handlungsmacht und Individualität, und sei es nur in Form diskursiver, mantraartiger gegenseitiger Lügen- und Täuschungsrituale einer vermeintlichen Ermächtigung über Sexus, Eros und geschlechtliche Natur, inszenieren müssen, wo die Praxis und das Individuum längst abgeschafft sind. In die Ermächtigungsträume dieser Menschen bricht stets die allgemeine Ohnmacht als eigene herein. Daraus erklärt sich auch die Aggressivität, die in der Abwehr gegen alles und jeden liegt, die jene prekären Episoden der inszenierten und selbsttäuschenden Ermächtigung hinterfragen.

M. Schönwetter

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Für Israel gegen die postkoloniale Konterrevolution.

Bahamas (Heft 93 / Winter 2024)

Zum Inhalt des Hefts Nr. 93, ausgewählten Online-Artikeln und Bestellung: redaktion-bahamas.org

Ausgewählte Artikel online lesen:

Es geht um Israel

Tödliche Illusionen

One Family gegen Israel

Inhalt:

Die Möglichkeit für die Gaza-Bewohner, jemals einer gesitteten Welt zuzugehören, hat ihre restlose Bezwingung und die Anerkenntnis von Palestinian Guilt zur Voraussetzung. Warum die gesittete Welt heute noch weniger existiert als zu Zeiten Thomas Manns, erklärt Justus Wertmüller in Es geht um Israel.

Der Ewige Siedler ist nicht nur ein antisemitisches, sondern auch ein antiamerikanisches Feindbild. Martin Stobbe verteidigt das Kolonisieren gegen seine progressiven Kritiker und benennt die Fakten sogenannter Siedlergewalt in Judäa und Samaria.

Israel steht Allein gegen die Umma. Die Gegnerschaft zwischen den arabischen Königshäusern und den Hamas-nahen Moslembrüdern macht das nicht ungeschehen. Kurt Karow mit seiner Analyse arabischer Verhältnisse unter besonderer Berücksichtigung Saudi-Arabiens.

Ob es auch Tödliche Illusionen waren, die 10/7 möglich machten, dieser Frage geht Martin Stobbe nach. Wieso er von einer Banalisierung des Bösen spricht und das Abwehrsystem Iron Dome zwiespältig nennt.

Anspruch und Wirklichkeit deutscher Staatsräson nach 10/7 nimmt Jonas Dörge unter die Lupe und begutachtet staatliche und ziviligesellschaftliche Israelsolidarität.

Bad Religion. Über den Zusammenhang von Islamkritik und Israelsolidarität, Deutschland und Islamliebe schreibt die AG Antifa Halle.

Jude, denke an Chaibar!, ruft die Hamas unter Berufung auf den Propheten Mohammed aus. Weshalb ein solcher Schlachtruf auch diejenigen im Westen zu mobilisieren vermag, die es ebenfalls auf die Vernichtung Israels abgesehen haben, erläutert Karl Nele.

Wie die postkoloniale Leugnung des Antisemitismus die Rationalisierung des Judenschlachtens möglich machte, zeichnet Tjark Kunstreich in The Holocaust in the room nach.

Nach dem Raver-Abschlachten durch die Hamas formierte sich die One Family gegen Israel auch in der Musik-Szene. Mario Möller mit Einblicken in die globale Raver- und lokale Berliner Clubszene.

Wo eine Kultur der Offenheit gepflegt wird, müssen auch linke Israelis den Mob fürchten. Justus Wertmüller mit einem Lehrstück über Neuköllner Szene-Verhältnisse.

Non-binär gegen Israel oder was Queers wie die Hannah-Arendt-Preisträgerin Masha Gessen mit der Hamas eint. Albert Berger darüber, wie das queere Bekenntnis endgültig zum antisemitischen wurde.

Gegen sich selbst denken hält Sören Pünjer für eine Grundvoraussetzung der Israelsolidarität. Über die Gründe ihrer relativen Erfolge und die ihres Schwindens in Zeiten bitterer Notwendigkeit.

Die oder wir, ein Drittes gibt es nicht mehr. Clemens Nachtmann mit seiner Feindbestimmung nach 10/7.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Lesley Chamberlain

The horror of a functioning democracy turning into a brutal dictatorship in a single month is etched into the German psyche. While Nazism claimed millions of victims at home and abroad, it also disfigured the national literary fabric. No biographer, critic or historian of the outstandingly creative 1920s and 1930s can ignore the moment when Hitler’s party, the NSDAP, tore apart the culture of the permissive Weimar Republic by targeting Jews, homosexuals, communists and “degenerate” expressionists. Writers and artists confronted a nightmare, with beatings in the street and storm troops at the door. For the 500 or so who eventually fled, the question was how long to hang on; where to go; how to survive. The panic strained families and ripped lovers apart. Personal loyalties were not always steadfast.

Uwe Wittstock, a prizewinning journalist whose late mother was two years old in 1933, suggests that while we struggle to grasp the catastrophe now, it was all the more unimaginable to its contemporary victims. February 1933: The Winter of Literature revisits moments in those well-documented lives by way of diaries, letters and public events. The personal routines, giddy socializing and creative obsessions belong to some of the best-known names in German culture of the last century, from the monumental novelist Thomas Mann and his brilliant, provocative adult children Erika and Klaus to the communist playwright Bertolt Brecht, the fabulous jazz-age composer Kurt Weill, who was Brecht’s collaborator, and the unforgettable satirical painters Otto Dix and George Grosz.

That transformative February Mann loftily decried his intellectual enemies as “hideous, violent little creatures”. His “Avowal of Socialism” (1922) had made him an enemy of the new regime. Yet he waged a curious battle in his last days in Germany, with his attachment to the high cultural past prompting persistent equivocations. Brecht, meanwhile, had recently written an “instructional play” – one of several such Lehrstücke for revolutionaries – which also made him radically unacceptable. In Erfurt the premiere of Die Maßnahme (The Measures Taken) was prevented by the police. Brecht demanded a bodyguard as he considered ways of escape.

The Nazis targeted not only individuals, but also the democratic institutions they served. Heinrich Mann, Thomas’s brother, fellow novelist and a staunch supporter of the Republic, was eased out of the Prussian Academy of Arts in what struck everyone as a scandal. Fellow academicians, ashamed, found themselves powerless to object. He was a huge name on the literary scene, thanks to Der Untertan and, Professor Unrat, soon to be filmed with Marlene Dietrich as The Blue Angel. Yet so vulnerable was his position that the French ambassador offered him his embassy should he need refuge.

But it is on figures less familiar outside Germany, such as the writer Else Lasker-Schüler, the left-wing editor Carl von Ossietzky and the anarchist poet and playwright Erich Mühsam, that the perverted age extracted particularly brutal revenge. Lasker-Schüler, born in 1869, aged sixty-three in January 1933, was occupying a tiny room in a Berlin hotel when Hitler was elected chancellor. “For a couple of years she [had been] the undisputed queen of Berlin’s bohemian society, boyishly slight, her black hair cut noticeably short, garbed mostly in baggy clothes and velvet jackets with glass-bead necklaces, clattering bangles and rings on every finger.” As Hitler began targeting every aspect of German life, her play Arthur Aronymus was blocked. It had won a coveted award, as the Nazi rag the Völkischer Beobachter fumed: “The daughter of a Bedouin sheikh receives the Kleist Prize!”. As if her clothes were not enough, her latest play featured conflicts between Jews and Christians. The avant-garde director Gustav Hartung was already in trouble with the NSDAP in Darmstadt over plans to produce Brecht’s Saint Joan. To put on the Lasker-Schüler play in Berlin seemed just too provocative. The author, knocked to the ground in her hotel foyer, bit her tongue so hard that she needed stitches.

Ossietzky, meanwhile, as editor of Die Weltbühne (“The World Stage”), the sharpest political and social weekly of the Weimar Republic, had already served two years in prison for decrying German military violations of the Versailles treaty. As the “winter of literature” closed in his friends begged him to flee, but this brave man insisted he would stay “to watch history unfold”.

On February 17 Mühsam rushed to the pub where Ossietzky was speaking that evening and spread the newspaper out on the table. Henceforth Reichsminister Hermann Goering was permitting the police to shoot to kill. “We will probably never see one another again”, Ossietzky responded, but “let us promise … to remain true to ourselves and to stand up with our body and our lives for what we have believed in and fought for”. Meanwhile, on February 18 the disruptive Brownshirts of the SA, Hitler’s Sturmabteilung, broke up the premiere of Kurt Weill’s musical The Silver Lake. Weill, the genius who had set Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera to music, was Jewish. The playwright Georg Kaiser was not – indeed, he was only vaguely leftist – but the Nazis went after him nonetheless. Wittstock doesn’t make the point, but it was a reflection of how politically powerful theatre had been in Germany since the time of the French Revolution that it represented such a threat. Overall, the Nazis feared “Bolshevization” – and their fear of socialist radicalism and artistic modernism stirring up Germany in the Soviet wake was in many ways well founded. The German Communist Party (KPD) would win eighty-one seats in the March 5 election (though its mandates would be annulled three days later). The Nazis especially hated the Jewish Mühsam for his involvement in the briefly established Soviet Bavarian Republic of 1918.

Ossietzky and Mühsam were both arrested in Berlin on February 28, the night after the Reichstag fire, together with the Czechoslovak Communist journalist Egon Erwin Kisch. Kisch, eventually released after ten days because of his foreign passport, witnessed abominable tortures administered to homosexual men at police headquarters. Mühsam held out, but died in a concentration camp in 1934. Ossietzky survived a while longer. The Nobel peace prize for 1935, organized by the future West German president Willy Brandt and awarded to Ossietzky the following year, recognized the courage of his spirit, but his body gave out shortly after the publicity that brought his release.

Throughout that February of 1933, blacklists of every kind grew longer. At her provocative Pfeffermühle (“Pepper Mill”) show in Munich, Erika Mann spotted three sombre figures in the audience taking notes on myriad sexual transgressions and political innuendo. Sex was always an issue for the Nazis (despite the culture minister Joseph Goebbels’s own secret adventures) and cabaret, particularly in Berlin, was an easy target.

Wittstock’s present-tense chronicle is packed with detail, from the crowd that formed a human pyramid so that someone could hand Hitler a rose at his window to the first book-burning in Dresden on March 8. As orgies of destruction spread across the country, university students lined up to pronounce “fire verdicts” on chosen works. “I consign to the flames…”, they chanted, naming Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, essays by the country’s foremost drama critic, Alfred Kerr, and anything by Ossietzky and his outstanding predecessor, the journalist and poet Kurt Tucholsky. Wittstock was mindful of the Capitol riots of January 2021 as he researched his book. He knows that history can repeat itself.

Each of Wittstock’s thirty-five days ends with brief newspaper reports of violent incidents around the country – including news of two brave souls who cut the cable during the broadcast of a Hitler speech – and there is a glossary of what happened to the main characters subsequently. My only criticism is that all this detail doesn’t actually build tension on the page. This reader had to work hard to bring the drama together.

Florian Illies has a more engaging – indeed, at times sensational – style. In Love in a Time of Hate the time span is ten years rather than one month, but many of the characters are the same, shown here in intensely private moments of their suddenly besieged lives. Like Wittstock, Illies immerses us in a stream of gossip (exchanged not least at the Romanisches Café in Berlin), and political rumour, in love affairs past and present, somehow carried on amid great personal achievements and terrible folly. There is a Freudian element and no little writerly brilliance in the way Illies implicitly asks: what did these people mean by love? The question lies at the heart of this racy catalogue raisonée of private passions.

Illies’s entries range beyond Germany to include the outrageous Black dancer Josephine Baker, the cold-hearted young Jean-Paul Sartre and his tortured new partner, Simone de Beauvoir, the Berlin-based fugitives from the Bolshevik Revolution Vladimir Nabokov and his wife, Véra, Picasso and his serial mistresses, and the surrealist painter Salvador Dalí and his devoted Gala (once the wife of the poet Paul Éluard, and still occasionally to be found in his bed). The catalogue of love affairs includes the extravagant bisexual adventures of Marlene Dietrich in America and even the infidelities of Charlie Chaplin, while Christopher Isherwood and Henry Miller look for extreme sex in Berlin and Paris respectively. All these characters and their antics belong to the same era as Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science, established in Berlin to clear up, on a wave of post-Freudian enthusiasm, any problems with inhibition and malfunction. This, then, was Europe in love.

Key figures in Illies’s German story are once again Klaus and Erika Mann, their choices homosexual and occasionally incestuous. The serial heterosexual loves of their uncle Heinrich also feature, though it’s his poor taste in women that upsets the family when they reunite in exile. (The erratic behaviour of his alcoholic wife, Nelly Kröger, he tries to blame on a fall.) Well known but worth repeating is the record-breaking callousness of Brecht as anti-lover of the decade. Unlike the novelist Hermann Hesse, who only left his bride to honeymoon alone, Brecht left his actual wedding to the actress Helene Weigel to spend the evening with his mistress. “Here you have someone on whom you can’t rely”, he told each new conquest, perhaps believing that exculpated him. Illies has some astonishing vignettes, all related, like Wittstock, in the present tense. One was the moment when Baker was bowled over by the modernist architect Le Corbusier. Soon they were dressing up as each other, an erotic encounter culminating in the shower, with Josephine washing the black make-up off Corb’s white skin. Another was the plight of Thea Sternheim, whose ex-husband, the playwright Carl, was raving with tertiary syphilis while Klaus Mann introduced their untameable daughter Mopsa to cocaine. Thea rented adjacent flats to house her loved ones. But then Pamela Wedekind, daughter of the playwright Frank, former lover of Erika Mann and now fiancée of the dying Carl, moved in too. Thea, distraught, begged for opiate injections from her ex’s carer.

If this was the age of “the New Objectivity” in Germany, it was also, in Erich Kästner’s variation on the theme, the age of Reasonable Romance. It seems to have been a value-free erotic zone stretching from Munich to Berlin, Vienna to Paris. Its actors had little concern for politics, except when it spoilt the fun. Nightclubs and foreign travel, great villas built on some of Europe’s most beautiful coasts: such were the backdrops to their realized dreams. When numerous leading intellectuals were forced to bed down for a short idyllic summer beside the Mediterranean, it didn’t seem like the Hitler emergency at all. When the Mann family held court at Sanary-sur-Mer from June to September 1933, Aldous Huxley and Sybille Bedford, as well as the German writer Lion Feuchtwanger in his mansion on the cliffs, were their near neighbours.

Only the expressionist poet Gottfried Benn complained, in a letter to Klaus Mann: “Do you think history is particularly active in French seaside resorts?”. This is an odd question, because it sounds as if Benn had really had too much of Marxist-inclined German writers occupying the moral high ground. But it does have some critical force, helping to pinpoint two European ways of being culturally modern – a New Man, a New Woman – in the early twentieth century. You could be a ruthless communist theoretician. Or you could be a sun-worshipping, god-building, car-driving, sex-crazed, drug-addled individualist.

Or, indeed, you could be Benn, a practising doctor and brilliant poet who, back in a Berlin he would never leave, was setting a new standard for the merciless “objective” coldness of the age. “Life is the building of bridges over rivers that seep away” seems like decent enough German pessimism; “Love is a crisis of the organs of touch” is simply cruel. Benn still attracted a steady stream of women, one of whom, invited for a drink to his flat for the first time, felt that, dressed in his medical white coat, he was going to dissect her with surgical instruments. Was it Benn’s coldness that led him to invest emotionally in the Nazi vision of a new civilization? His fellow writers tried to dissuade him from advancing his uncongenial views, as if they didn’t really take him seriously. The Nazis left him alone because they didn’t want the support of an expressionist degenerate. When his muse returned he wrote some of the greatest poems of the century.

In his novel Mephisto Klaus Mann had based the main character on Gustaf Gründgens, the former husband of his lesbian sister. The three made a foursome, on occasion, with Pamela Wedekind. Illies’s book is full of such permutations, as if all the sexual taboos dictated by culture had vanished in a new age. Many of the heterosexual Weimar-era men believed that their creativity depended on pain, violence and new conquest, at whatever cost to their discarded partners. Neither of these books analyses the extremes it chronicles, but one remembers the strange and ambivalent role played by sexuality in Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (originally drafted in 1944), where the culture of Reason, now apparently reaching its apotheosis in Hitler, was somehow the product of rechannelled sexual aggression. A kind of sexuality hitherto underground had become a new extreme cultural and political force.

So what of love, in the end? Some of the most moving stories here concern children and pets. When sex was out of the way everyone behaved better. Ex-spouses helped each other in extremis. Wittstock has the marvellous story of how Brecht and Helene Weigel had their daughter, Barbara, smuggled out of Augsburg with the help of a German nanny and an Englishwoman living in Vienna. Irene Grant, with her four-year-old son on her passport, crossed the border and brought Barbara, two and a half, dressed as a boy, to her parents. (My own husband had a similar escape six years later.) The singer Lotte Lenya had divorced Kurt Weill, but then he helped her to escape Germany and eventually they got back together. Other friends made sure that Weill was reunited in exile with his dog. Back in Berlin, much worry went into not abandoning Gründgens’s sheepdog, Haari.

They were all enemies of Nazism, certainly. But what kind of politics, what kind of society, would have best suited this licentious, aesthetic-minded generation, with its gigantic artistic talents and potential for deep moral waywardness? Presumably, our ultra-liberal own. Perhaps that’s why Illies remains so reserved in his moral judgements, finding the antisemitic vamp Alma Mahler pretty nasty, but only the Hitler-loving film-maker Leni Riefenstahl (“there was a strong streak of elitism to her nymphomania”) “diabolical”. He’s rather lenient, to this reviewer’s mind, and rather hard on Thomas Mann’s “noun-heavy moralizing”. I would have liked to hear him call Brecht not only a great artist, but also a pernicious moral fraud. Illies engages with some relish in his tale, where Wittstock, two generations older, is outraged and sad. In m

aking these observations, though, I may be the product of a staider generation. So let me conclude by saying that, for all the compelling studies on the Weimar Republic, no one will want to miss either of these well-translated books on Weimar writers and Weimar in love.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Leviathan der Tyrann

Leviathan der Tyrann ⋆ Jeffrey A. Tucker ⋆ Glaube Ethik und Moral

Leviathan der Tyrann ⋆ Jeffrey A. Tucker ⋆ Glaube Ethik und Moral

Die letzten Jahre waren ein Lehrstück in Tyrannei. Ein mächtiger Hegemon aus Regierungen, Medien, Technologie-Konzernen und medizinischer Elite übernahm die Kontrolle über die meisten westlichen Nationen und setzte sich einfach über Gesetze, Traditionen und Bräuche von Milliarden von Menschen hinweg. Am Ende dieses großen Experiments ist nichts als Niedergang und Zerstörung zu sehen. Alles in allem waren die letzten Jahre eine große Machtausübung auf globaler Ebene. Aber was hier mit Machtausübung gemeint ist, ist der Transfer des Reichtums vom Mittelstand zu den Eliten, Cancel Culture - Zerstörung alter Werte - und die Kontrolle einer herrschenden Klasse über die gesamte Bevölkerung. Institutionen, auf die wir uns bei der Verteidigung unserer Freiheiten und Rechte verlassen haben – gemeinnützige Organisationen, Gerichte, Intellektuelle, Wissenschaft, Technik und Medien – haben alle auf spektakuläre Weise versagt. Deshalb brauchen wir dringend institutionelle Reformen. Man spricht zwar davon, vieles reformieren zu wollen, aber vergessen Sie das. Einige Institutionen sollten vollständig aus der Finanzierung gestrichen werden. Viele sind durch und durch korrupt. Es gibt keine Hoffnung mehr. Außerdem bedarf es einer drastischen Gesetzesreform. Wir Bürger hatten keine Ahnung, wie viele Institutionen schon seit langer Zeit gefangen genommen worden sind. Wir wussten nicht, dass Leviathan tief in Facebook, Instagram, Twitter und LinkedIn verwurzelt ist. Wir wussten nicht, dass Medien und Nachrichtenseiten nur zu Werkzeugen des Regimes geworden sind. Die Idee der Freiheit selbst, die Mutter dessen, was wir Zivilisation nennen, reicht weit in unsere Geschichte zurück. Die Botschaft ist klar: Es gibt Rechte, wie die Menschenrechte, die eine Regierung unter keinem Vorwand abschaffen kann. Aber sogar dieser Anspruch wird seit mehreren Jahren grundsätzlich infrage gestellt. Noch gibt es Gemeinschaften, die Widerstand leisten. Dies sind nicht die säkularen Eliten und schon gar nicht die Akademiker oder die Wirtschaft. Es sind meist kleine religiöse Gemeinschaften: die Chassidim, die Amish, die Mormonen, die Muslime, die Buddhisten, die Daoisten, und die Christen. Es stellte sich heraus, dass das Festhalten an einen festen Glauben, Werte und das Leben in einer Gemeinschaft von Menschen, die sich ebenfalls zu diesem Glauben bekennen, der beste geistige und intellektuelle Schutz gegen die Ansteckung mit den Mythen ist, die uns der Leviathan täglich auftischt. Alles deutet darauf hin, dass wir, wenn wir dem »Great Reset« widerstehen wollen, eine ganz andere Weltanschauung brauchen. Eine Weltanschauung, die tief in unseren Herzen und Seelen verankert ist, und eine Struktur von Überzeugungen, die weit über das bloße Geldverdienen und Konsumieren hinaus geht. Mein bescheidener Vorschlag lautet daher: Wer keinen Glauben und/oder keine Spiritualität besitzt, der sollte sich deshalb sofort dergleichen zulegen. Der Mensch bracht so etwas, um sich vor den Lügen der säkularen Eliten zu schützen, die nur ihre eigene falsche Version von Religion bzw. Ethik verkaufen wollen. Aber Vorsicht, auch aus fundamentalistischen Glaubensrichtungen kann ein Leviathan entstehen. Zur Zeit herrscht wirklich ein Notfall, den wir haben und den keiner von uns wollte. Aber er ist da und wir müssen handeln, bevor es zu spät ist. Wenn Sie jetzt noch Zweifel haben, denken Sie einfach darüber nach, was in den letzten Jahren so alles geschehen ist. Das Ganze war offensichtlich kein Versehen. Das Ganze ist der bewusste Versuch, alles, was wir lieben, was uns wichtig und wertvoll ist, zu demoralisieren und zu zerstören. Leviathan der Tyrann ⋆ Jeffrey A. Tucker ⋆ Glaube Ethik und Moral Read the full article

#Avemecum#Aventin#Brauch#Bürger#Essay#Ethik#Freiheit#Gesetz#Glaube#Institut#JeffreyA.Tucker#Leviathan#Moral#Spiritualität#Tradition#Tyrann#Weltanschauung

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Lehrstück Agendasetzung in der Politik

Podcast Steuergerechtigkeit AB Min 13:27

0 notes

Text

Russische Soldaten

fahren in

US-Bradley - !!!

https://rumble.com/v5ovv3b-trophe-im-einsatz-us-panzer-bradley-im-dienst-der-russischen-armee.html

#russland#deutschland#ukraine#usa#nato#eu#ukraine krieg#amherd#ukraine-krieg#bradley#lehrstück#pistorius#bundeswehr#süssli#schweiz#merz#taurus#schweizer Armee#kriegstauglichkeit#kriegstüchtigkeit

0 notes

Text

'Reduced to his smallest dimension, the thinker survived the storm.'--Brecht, Das Badener Lehrstück vom Einverständnis

1 note

·

View note

Text

Volkswagen und Volksfeinde

Tichy:»Es geht nicht nur um Volkswagen. Und auch nicht nur um die Automobilindustrie in Deutschland. Es geht gegen das Auto als Verkehrsmittel für’s Volk, um einen Angriff auf individuelle Freiheit. I. Die Krise des Volkswagenkonzerns ist ein Lehrstück. Die offenkundigen Gründe sind unter anderem Konjunkturschwäche, Einbruch des chinesischen Marktes, überstürzter Ausstieg aus der Verbrennertechnologie, mangelnde Der Beitrag Volkswagen und Volksfeinde erschien zuerst auf Tichys Einblick. http://dlvr.it/TFydXr «

0 notes

Text

Der Weg des Stahls in die Zukunft – ein Lehrstück in vielen Akten

Erster Akt: Der Anfang der Erkenntnis Es steht fest: Die Welt braucht Stahl. Er trägt Häuser, Brücken, Fahrzeuge – das Rückgrat des Fortschritts. Doch dieser Fortschritt hat einen hohen Preis, der nicht nur in Tonnen, sondern in unsichtbaren Wolken von CO2 zu messen ist. Etwa 8% der globalen Emissionen entspringen den Feuern der Stahlproduktion. Die Frage, die sich stellt: Ist es möglich, diesen…

0 notes

Text

Aus der Welt der Verkehrsteilnehmer

Artikel hinter Paywall und im Archiv

0 notes