#Legion: life in the roman army

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

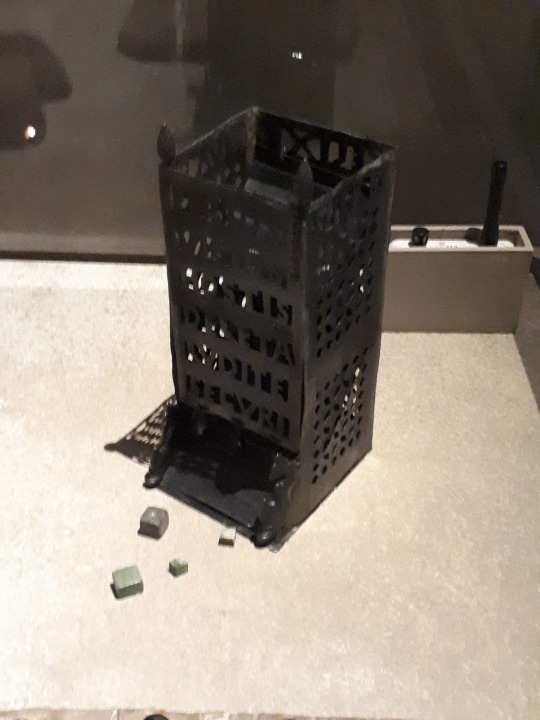

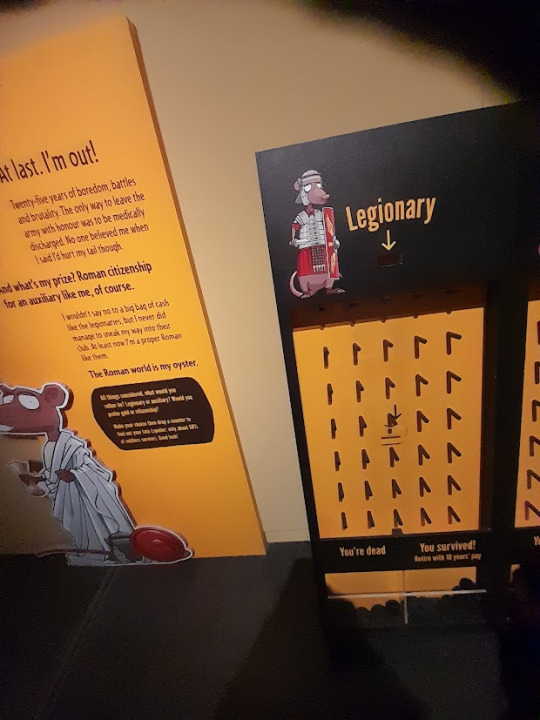

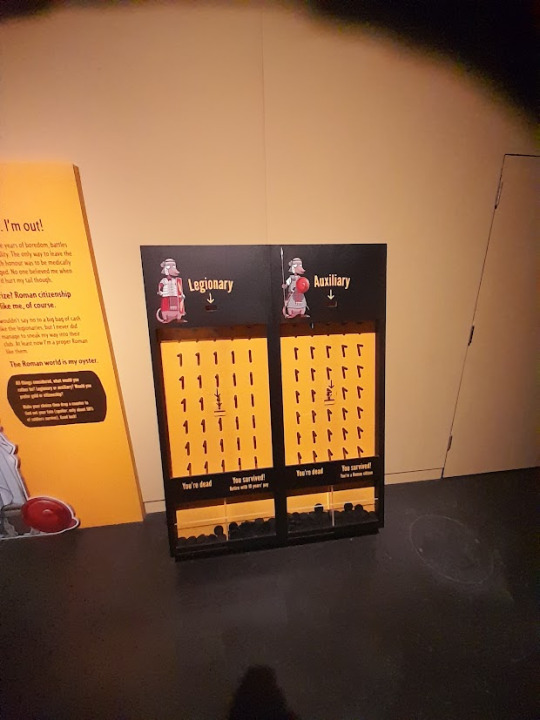

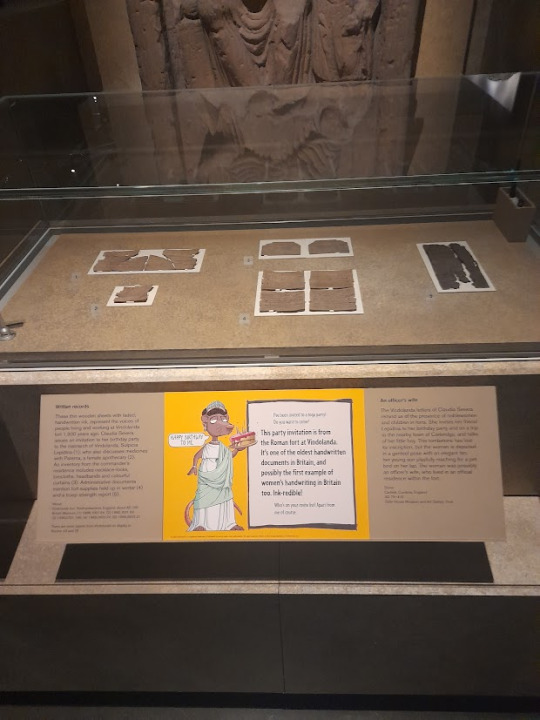

BEST THING IN THE EXHIBIT

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

What Was Life Like in the Roman Army?

The British Museum’s New Show Offers a Peek

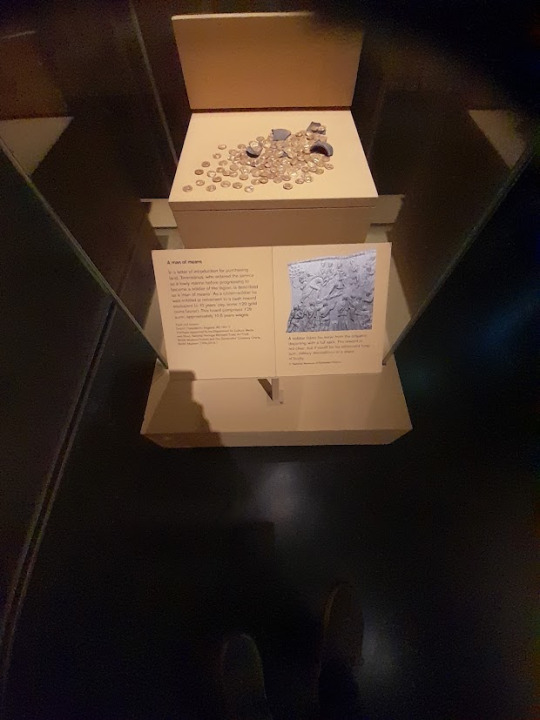

"Legion" showcases objects including scabbards, coins, and the world's only intact legionary shield.

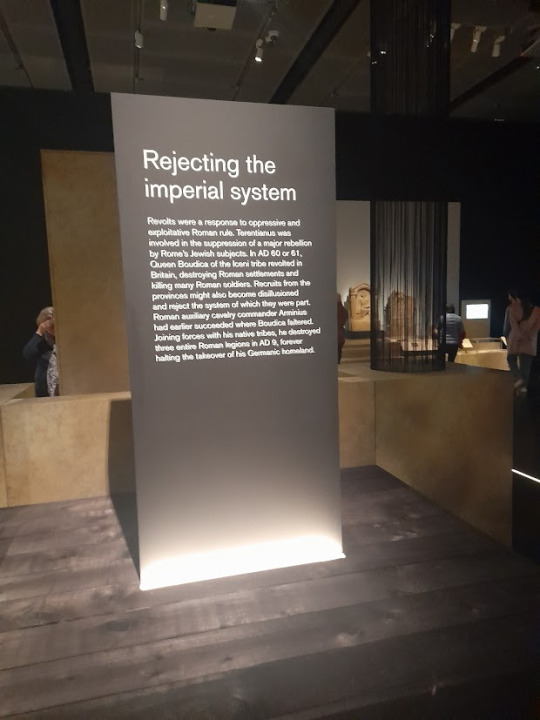

The viral nature of the term “Roman Empire” makes it easy to forget the trend started because ancient Rome had one of the most unforgettable armies in history. A new show at the British Museum is turning the spotlight on the soldiers that helped build and safeguard Roman rule.

Legion: Life in the Roman Army” transports visitors to the million square miles that was once the Roman Empire to explore its unparalleled military might through the eyes of the people who lived it. The museum already has a dedicated gallery space covering the rise of Rome from a small town to an imperial capital, covering a period of about 1,000 years. But the latest show humanizes that collective power through more than 200 exhibits ranging from soldierly objects to everyday items that capture the lives of citizens living under military rule.

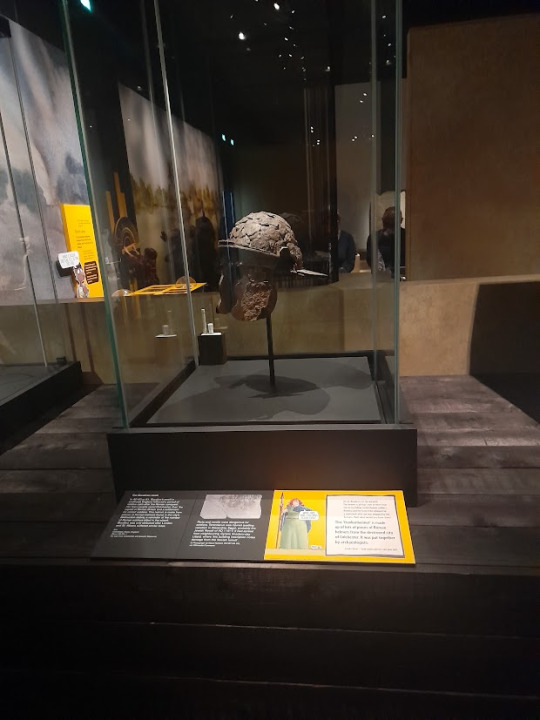

Copper alloy Roman legionary helmet.

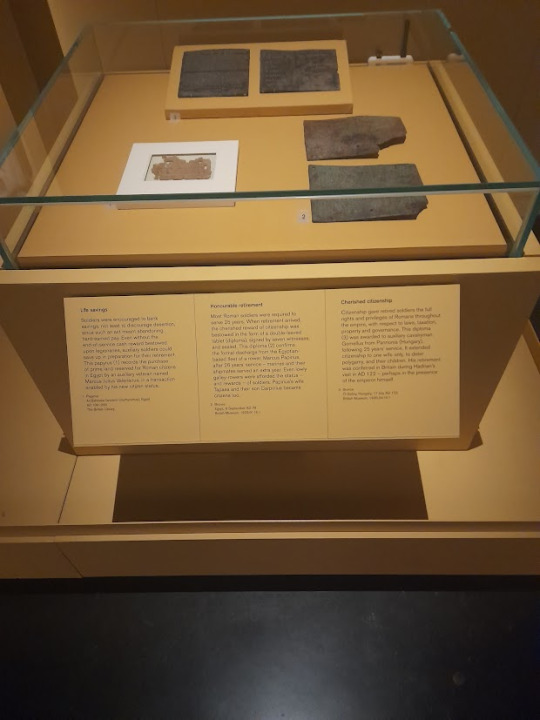

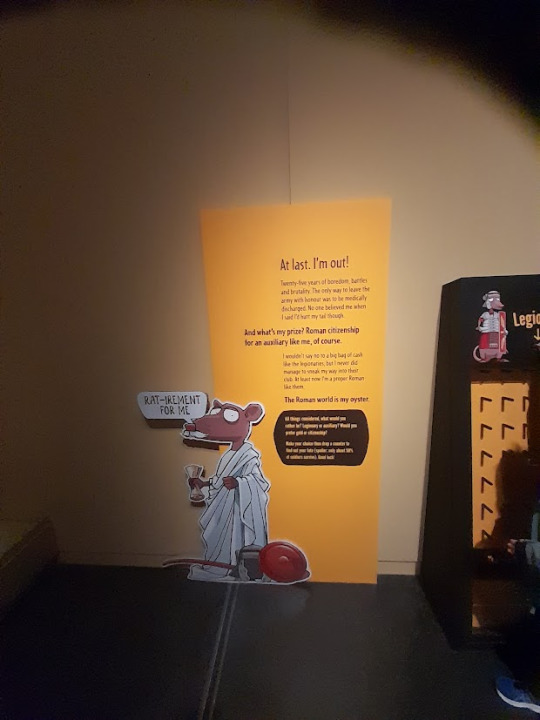

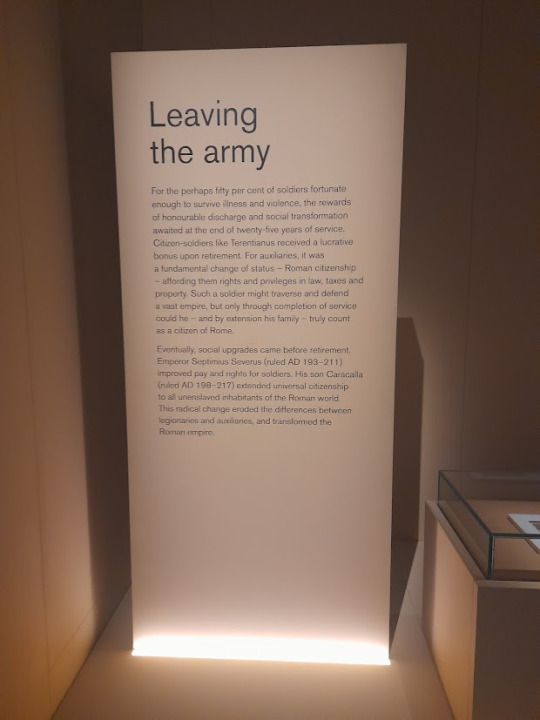

“Few men are born brave,” wrote Vegetius in the later Roman Empire. “Many become so from care and force of discipline.” From the 6th century B.C.E., soldiering was a career choice and joining the army came with substantial perks (if you lived), including a substantial pension. Foreigners entering the auxiliary troops could also attain citizenship for themselves and their families.

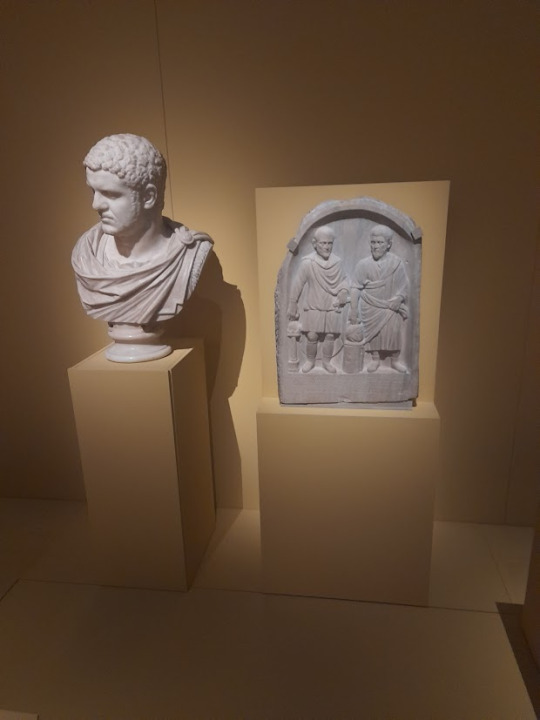

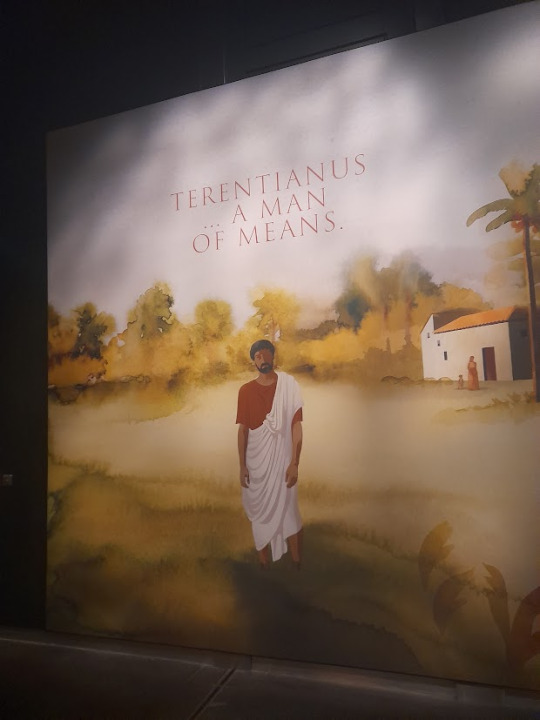

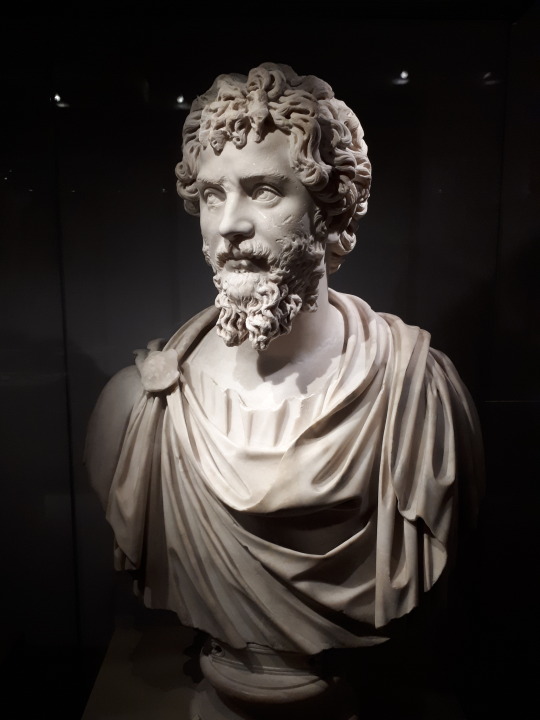

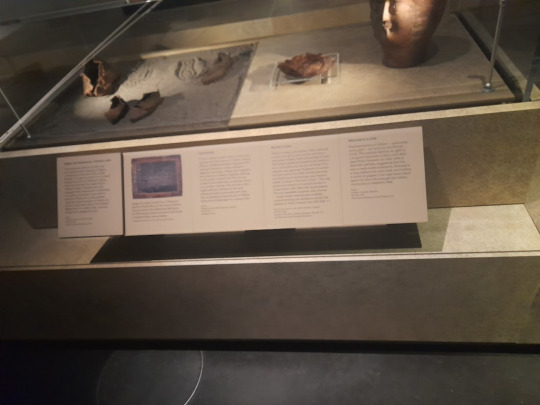

The show traces the journey of a notable Roman soldier, Claudis Terentianus, following him from his enlistment to his participation in campaigns to his retirement. Along the way, visitors can view the armor and weapons soldiers wielded in battle, from a gilded bronze scabbard to a copper alloy helmet to the world’s only intact legionary shield. Domestic objects such as children’s shoes illustrate the family life of military men; coins and tombstones allude to the cost of the empire’s wars.

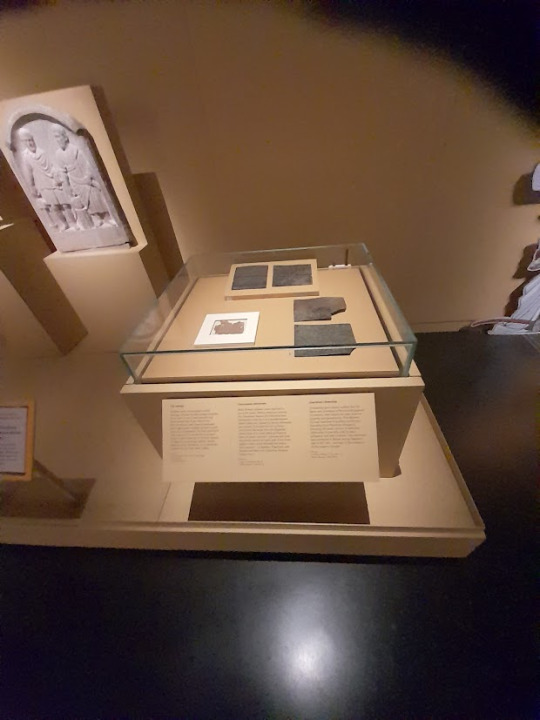

Also included in the show is an ancient Roman arm guard, found in fragments in 1906 and recently reconstructed by the National Museums Scotland—the first time the artifact can be viewed in its entirety in millennia.

“Sword and sandals, helmet and shield are all on parade here as would be expected, but told through often ordinary individuals,” Richard Abdy, the museum’s curator of Roman and Iron Age coins, said in a statement. “Every soldier has a story: it’s incredible that these tales are nearly 2,000 years old.”

By Jamie Valentino.

A helmet depicting the face of a Trojan.

Sword of Tiberius – Iron sword with gilded bronze scabbard.

Tombstone of an imaginifer’s daughter, 100-300 C.E.

Roman scutum (shield).

Gold coin featuring an oath-taking scene between two soldiers.

A 2,000-year-old Roman cavalry helmet.

#What Was Life Like in the Roman Army?#The British Museum#Legion: Life in the Roman Army#Claudis Terentianus#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#roman history#roman empire#roman legion#roman art#ancient art

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

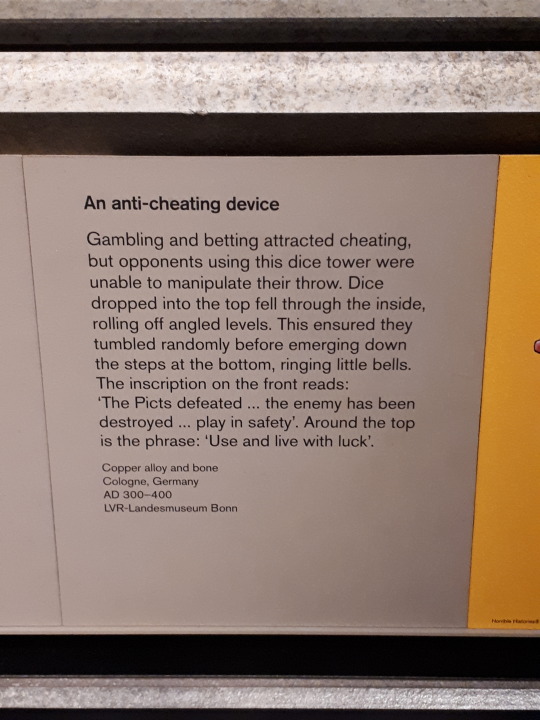

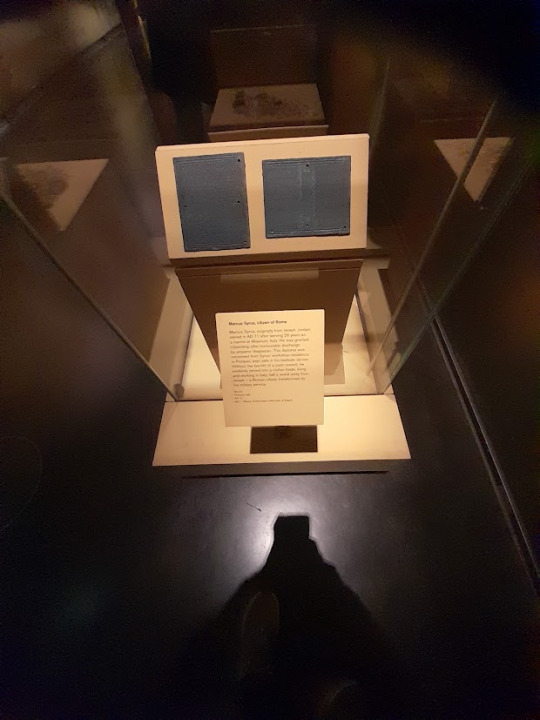

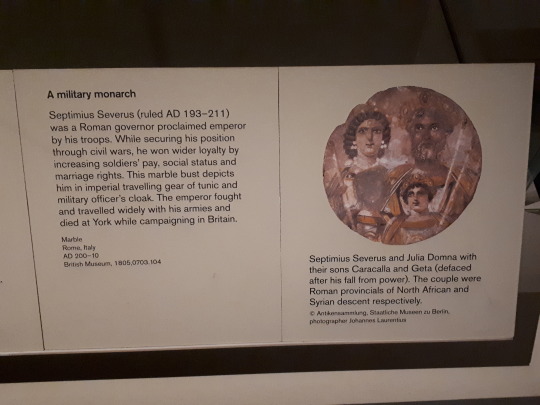

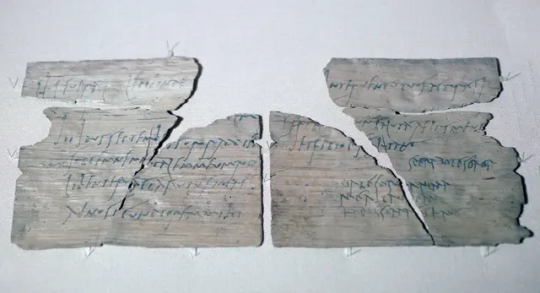

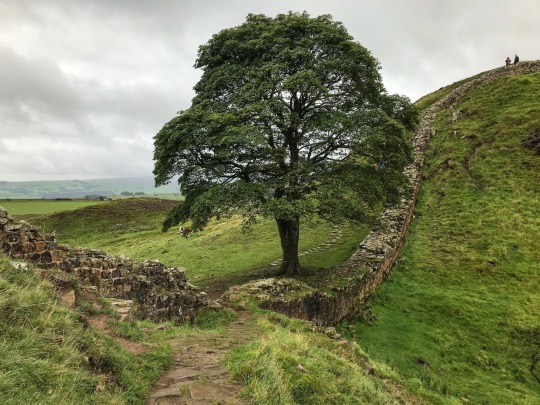

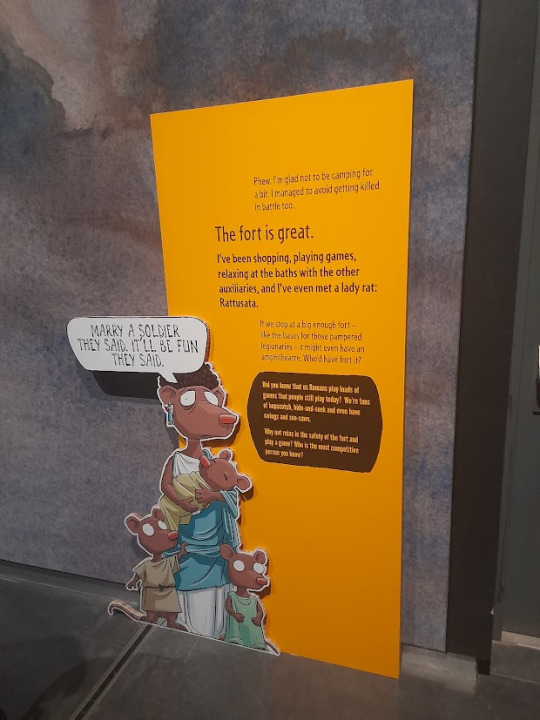

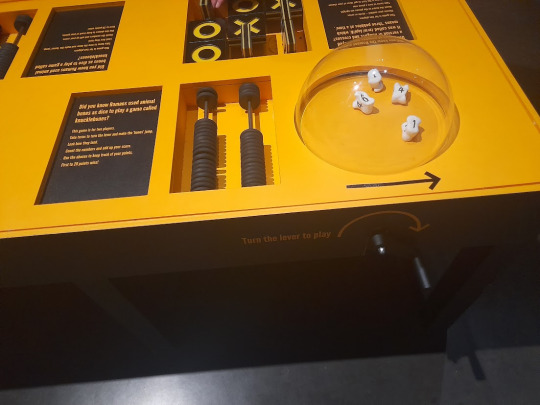

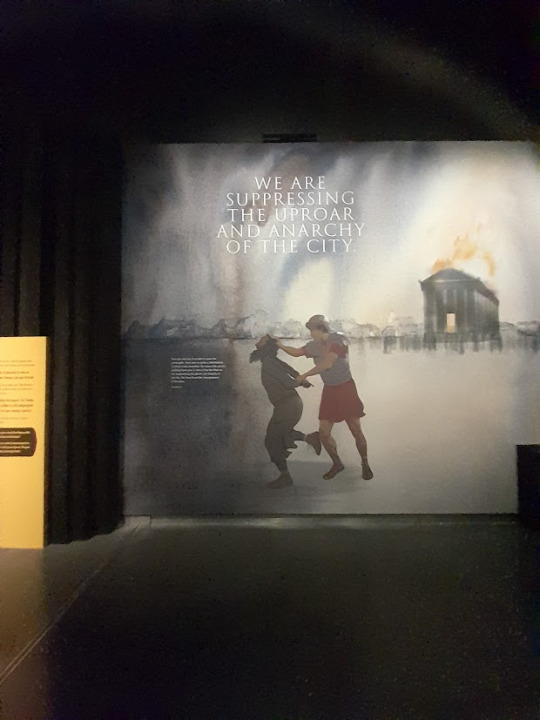

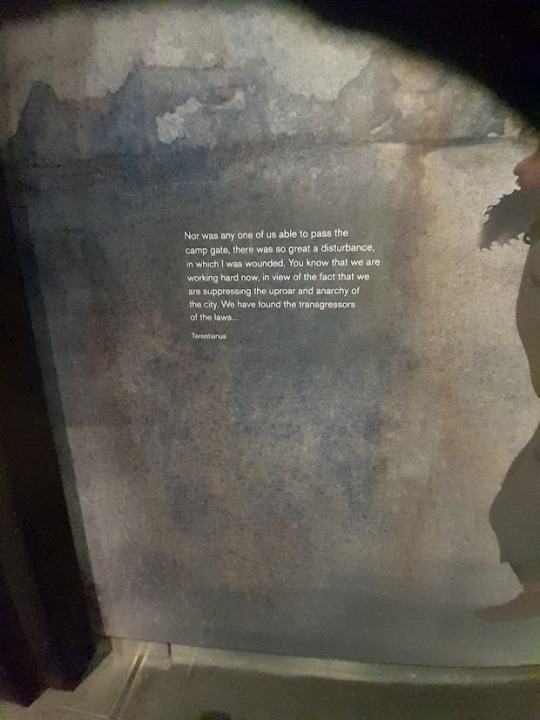

25th February 2024 British Museum: Legion: life in the Roman army Part 8

Nearly there now!

That's it!

0 notes

Text

Legion: life in the Roman Army

(Subtitle: YV decides to go to the British Museum and is very fortuitously surprised by the temporary exhibition there that season)

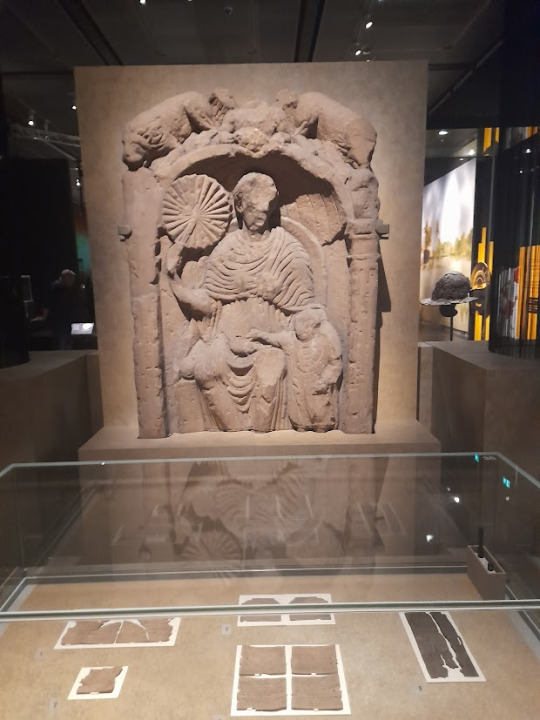

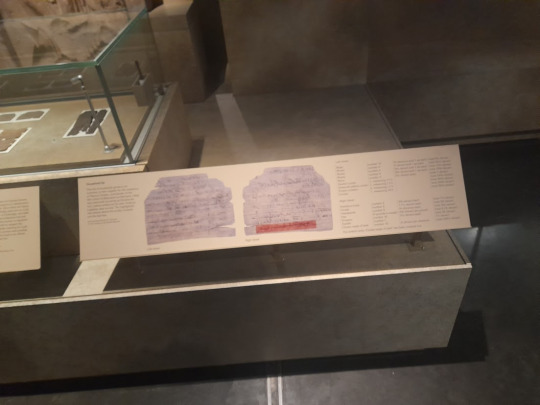

Back in April of 2024 I happened to be in London for a week and was right in the middle (literally, I had finished Part 2 and had yet to start Part 3) of The Lights That Burn.

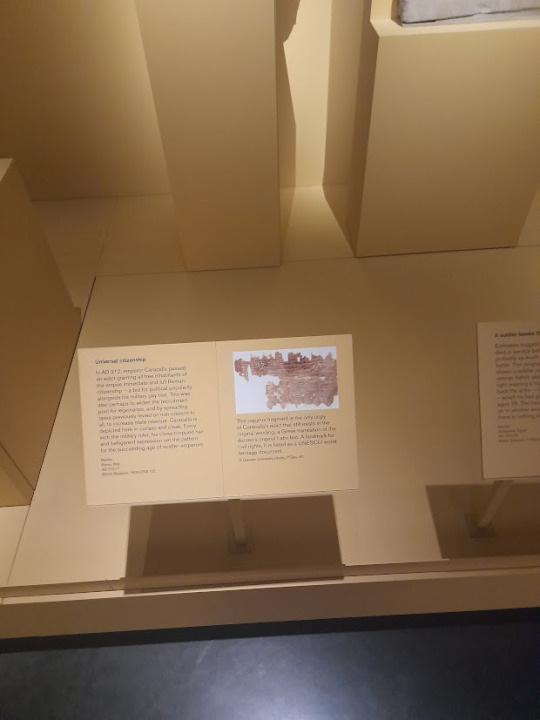

During a spontaneous visit to the British Museum I found out they were hosting an exhibition on Roman soldiers (I believe it ran until June that year). Luckily, my companion was game (shocking news, it is not difficult to convince a man to take an interest in the Roman Empire) and there was a lot of fascinating stuff to discover.

Below are some Highly Unimpressive (because of the quality not the content) photographs of Cool Shit and Fun Facts, some of which I found a way to work into the story I was writing, and some that I just enjoyed learning about because Rome Was Very Interesting. (This is probably going to be a few posts worth)

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

THREADS OF FATE

Pairings : pedro pascal (marcus acacius) x megara!reader

Genre : (AU where Ancient Greece and Rome existed at the same time, Hercules/Herakles is the general of Greece, use of Y/N L/N for reader and is the princess of Greece, inspired by Megara, described to have long hair, angst, mentions of death and war, sexual tension?, enemies to lovers trope, Marcus is an asshole at first)

Synopsis : In which the general of Rome captures the princess of Greece.

Word Count : 8.7k

Taglist : @orcasoul

Moodboard :

-----

“FOR THE GLORY OF ROME!”

The general of Rome proudly shouts in victory as his entire army of soldiers and warriors rejoices that Rome has once again won another war.

The air was thick with the stench of smoke and the clamor of soldiers as the Roman legions paraded through the conquered lands of Greece. The earth trembled beneath the weight of their triumph, Rome's banner now draped over the fallen city. The battle had been brutal, the resistance fierce, but in the end, the might of Rome had crushed it all.

Marcus Acacius, victorious and undefeated, rode at the head of his men, his armor gleaming in the dying light of the day. His eyes were sharp, his mind calculating. The campaign had been long and taxing, but Greece was finally subdued. The banners of Rome now flew high across the lands, marking the fall of one of the greatest civilizations to ever rise. And Marcus, he had earned his place as a general in the annals of Roman history.

But as the sun dipped below the horizon, casting a fiery red glow over the battlefield, Marcus’s steely gaze fell upon something that made him pull his horse to a halt. It was not the bodies of fallen soldiers, nor the smoldering ruins of a once-great city that caught his attention, it was the figure of a woman, kneeling amidst the wreckage of what had once been a proud Greek encampment.

Her hair cascaded around her face, her lavender dress stained with dirt and blood. Her posture was one of deep grief, as if the weight of the world had fallen upon her slender shoulders. Her eyes, swollen from crying, stared mournfully at the lifeless body cradled in her arms. The man she held was the very same Greek general who had fought against Marcus, whom he had killed in the final battle.

Her lover.

General Herakles.

For a moment, Marcus’s heart twisted in an unfamiliar way. It was a fleeting emotion, one he could barely comprehend, but it was there. The sight of her, clutching the body of the man who had once been her world, made something within him shift. He had never been a man to pity, but there was something about the raw anguish in her eyes that unsettled him.

The soldiers around him were unaware of the emotional stirrings of their commander, too busy with the spoils of war to notice the woman. But Marcus's mind was far from the victory feast awaiting them back in Rome. He dismounted from his horse with a swift motion, his cloak swirling around him. The rest of his men watched curiously, but none dared to question his actions.

“General.” One of his soldiers ventured cautiously, “We’ve taken the city.”

“I see that.” Marcus interrupted, his voice cold and sharp. He didn’t need the reminders of their conquest. His eyes remained fixed on the once princess of Greece.

Without a word, he began to walk toward her, his footsteps soft but steady on the charred earth. She did not notice him at first, too lost in her sorrow, her fingers gently caressing the dead general’s face, her lips whispering words of mourning. Her eyes were glazed over, lost in the final moment of what she had loved.

It was only when Marcus’s shadow fell over her that she lifted her gaze, her eyes locking onto his with a mixture of disbelief and fury. She recognized him immediately. The man who had taken everything from her, the man whose sword had ended the life of the only man she had ever truly loved. The same man who brought her home into ruins.

Her breath hitched, and the tears that had not yet dried began to spill once more. This time, however, they were no longer the tears of a woman mourning a lover, they were the tears of a princess wronged. Her grief hardened into something darker, more dangerous. The last thing she wanted was to face this man again. She had wished that she would never have to look upon his face again after what he has done.

But here he was.

“What are you still doing here, you monster? I thought you would be long gone by now.” Y/N spat, her voice trembling with a mixture of hate and sorrow. “Your precious Rome has betrayed us. You made sure to rob him of the chance to defend himself, to defend our lands.”

Marcus’s jaw clenched as she spoke. Her words were like daggers, each one striking a place inside of him he didn’t know was vulnerable. The way she spoke, with such raw venom, reminded him of why he had fought in the first place. To keep the world in order. To bend it to Rome’s will.

But the sight of her now, holding her dead lover, pierced through that certainty.

Her words struck deeper than the blade he had buried in her lover’s chest.

“Get up.” He ordered, his voice low and commanding. “We are leaving.”

The soldiers who followed Marcus approached slowly, unsure of what to make of the scene unfolding before them. One of them moved toward Y/N to drag her away, but she didn’t flinch. She didn’t even acknowledge the soldiers at first.

She simply stared at Marcus, her eyes cold, narrowing with every passing second.

“I won’t go with you.” She said firmly, her voice stronger now. “You have already taken everything from me. Do you truly think I would ever willingly follow you?”

Marcus’s gaze hardened. “You will follow me because I command it. You are coming back to Rome as a symbol of the victory of Rome. The world will know that even Greece has fallen to the might of the empire.”

Y/N shook her head, tears streaking down her face once more, but there was no defeat in her eyes. There was only the fire of defiance. “I have no place in your empire, Roman. I am a prisoner of my own sorrow, not yours. Do you think you can break me by forcing me into chains? You have already taken my life from me. I will not allow you to strip me of my dignity.”

The tension between them was palpable, but Marcus’s face remained stoic, unreadable. He had commanded the deaths of many, and had crushed countless opponents beneath his heel. He had brought entire cities to their knees, and this woman, this Greek woman, was no different.

“Chain her.” Marcus ordered coldly. “And bring her to the camp.”

Y/N resisted as they moved to restrain her, but the soldiers were swift and strong. She fought back with every ounce of her strength, but the pain in her chest was too overwhelming, and the soldiers’ iron grip proved stronger than her fury.

She was dragged away, her head held high despite the pain that coursed through her, her thoughts a storm of hatred and grief. Her world had been taken from her once, and now, once again, she would find herself under Roman control.

As the soldiers escorted the princess of Greece toward the Roman camp, Marcus Acacius rode silently beside them, his mind a tangled web of thoughts. He had won his victory, but in the depths of his heart, something unsettled him. Something about her, the way she had defied him, the strength in her sorrow, made him wonder if this war had truly been won.

The road to Rome was long, but the battle within Marcus had only just begun.

-----

The clinking of iron shackles echoed through the entire camp, the rusted irons grills of her cell and the undeniable scent of blood filled her senses. Y/N L/N, her form cast in shadows, paced back and forth in her cell, her mind sharp despite her exhaustion. The faint smell of blood and sweat filled her nostrils, but it was nothing compared to the bitterness that had settled in her chest. The memories of her life before captivity seemed like distant echoes, a cruel reminder of what had been lost.

She thinks back to the abandoned corpse of her husband, General Herakles, a man who had fought valiantly for their people. The now rotting corpses of her soldiers, her people and everyone who she had no choice but to leave behind, abandoning them to the desolate lands that were once the majestic grounds of Greece, her beloved home. But that was before Marcus Acacius had entered the battlefield, before he had torn her world asunder. He had slain her beloved husband in cold blood, a man she had adored and cherished. The very same man whom she was promised to and has shared dreams and promises of creating a brighter future together for Greece. Marcus's name had haunted her every waking moment since, a reminder of the power that men held and the devastation they could leave in their wake.

Her captors, the Roman soldiers, had treated her with the same cruel indifference they afforded to any prisoners of war. They all know who she was. The royal blood running through her veins and the crown she holds high upon her head. But they didn’t give a damn. To them, she was just another woman to be paraded in the gladiator pits, another piece of property in a city overflowing with ambition and lust for power. A reminder of their victory and glory for another war won. A proof of their never ending greed to expand their dynasty like it was the damn plague.

Her hair, tied into a high ponytail, swayed as she moved, the curls at the tips bouncing with each step. The lavender dress she wore clung to her form, accentuating her curves, but it was a mere symbol of her past life, a time before she had been reduced to a mere shadow of herself. The golden strap of her dress dug into her skin, reminding her of the chains that still bound her, metaphorically and physically. Her eyes were sharp and calculating, yet betrayed a deep sorrow that had no end.

Y/N had learned to keep her thoughts to herself. She knew better than to speak freely in this land of men who valued conquest above compassion. But despite her cold exterior, she dreamed of escape, of vengeance, of a world where men like Marcus Acacius did not get to dictate the fates of those they saw as lesser.

The fates had a cruel sense of humor, for now Marcus found himself standing before her. The same woman, who was once the princess of Greece. The same defiance that he has seen in countless prisoners that Rome has taken. And now she is no longer the dignified princess of Greece and was nothing more than a slave, bound to a life that had no dignity.

-----

The grand city of Rome was a sight to behold in the wake of its victory over Greece. The streets buzzed with triumphant energy as the Roman people poured out from their homes, eager to witness the return of their victorious general. Banners flew proudly from every corner, the golden eagle of Rome soaring high above, a symbol of power that now stretched across the lands of Greece. The people roared in approval, their chants rising up in a cacophony of celebration.

Marcus Acacius rode at the head of his soldiers, his armored figure a symbol of Rome’s invincibility. The cheers from the masses grew louder with each step he took. They hailed his name, shouting, "Marcus! Marcus!" The streets seemed to pulse with the energy of the people’s adoration, their voices like a thunderous storm that seemed to echo through the very foundations of the city.

But amidst the jubilation, Marcus’s gaze remained focused, his expression as stoic as ever. Though he basked in the glory of Rome’s triumph, there was something that gnawed at the edges of his mind. The sight of Y/N walking beside him, her chains that he was holding in his very hands, was a stark reminder of the weight of what he had done.

Y/N L/N, the Greek woman who had once held the heart of her fallen general, now stood at the center of Roman pride. Her eyes burned with defiance, her head held high, her posture regal even in the face of captivity. She did not beg for mercy. She did not weep like the many others had when brought to Rome as prisoners. No, she stood as a noblewoman would, unyielding, proud, and fierce in her own sorrow.

Her chains clinked with every step, the iron biting into the skin of her wrists, but she didn’t flinch. To the Roman people, she was but a symbol, an object of conquest, a mere prisoner to be paraded before their eyes. Yet, the princess of Greece was not so easily broken.

Her lavender dress, though now stained and torn from the journey, still held an air of dignity. The golden straps, now dulled from the harsh journey, glinted faintly as the sunlight caught them. Her hair, once immaculately styled, now fell in, tangled waves, but it didn’t matter. She was still beautiful, still a force to be reckoned with. Her eyes, though filled with the remnants of grief, held an unshakable strength that no Roman could take from her.

Marcus’s fingers curled around the chains that connected them, the weight of them in his hand a constant reminder of his authority, but even as he gripped them, he found his attention drawn to the woman beside him. There was something about the way she carried herself, as though she were not a prisoner at all. The crowds around them may have been celebrating Rome’s triumph, but Y/N’s quiet defiance was a challenge, one that lingered in the air like a slow-burning flame.

The people of Rome could see nothing but a prisoner at Marcus’s side, a broken woman who had lost everything. But Y/N knew better. She knew her worth, and she would not let these people forget that she was not just a casualty of war. She had been a figure of nobility, a woman with a past that was far more complicated than they could ever know. And in her heart, she would continue to hold herself as such, no matter the chains that bound her.

“Do they think you’ll beg for mercy, Greek?” Marcus’s voice cut through the sounds of the celebration. His gaze was still forward, but his words were pointed, as though testing her resolve. “You may be a woman of Greece, but here, you are nothing but a prisoner.”

Y/N didn’t turn to him, her steps steady as she walked beside him, feeling the weight of the eyes upon her. She had no intention of letting her spirit be crushed by this Roman parade. Her eyes scanned the crowd, the faces of the people who watched her as though she were an exhibit, a trophy to be admired.

“I will not beg for mercy.” Y/N replied, her voice low but firm. She met his gaze with a quiet intensity, her eyes never wavering from his. “And you will not break me. You may have conquered Greece, but you will never conquer me.”

Marcus’s jaw tightened at her words, but he didn’t respond. He didn’t need to. The people around them cheered louder, a deafening roar rising up from the masses as they reached the grand stairs leading to the Imperial Palace. There, a large crowd had crowded for Marcus’s triumphant return, where he would receive the accolades of Rome’s Emperors, senate and the people alike. The princess of Greece, however, was not to be treated as a guest. She was led to a smaller, less ceremonious area, far from the glory that awaited her captor.

The grandeur of the Imperial Palace was like no other in the empire. Marble columns stretched high into the sky, their surfaces gleaming with the brilliance of Rome’s wealth and power. Statues of past emperors lined the hallways, their stern faces gazing down on all who dared to enter. The palace buzzed with the preparations for the grand assembly where Marcus Acacius, the hero of Rome, would present his proof of conquest, Y/N L/N, the last of Greece’s nobility, captured and soon brought before the Emperor Brothers as the symbol of Rome’s undeniable triumph.

Marcus stood at the entrance of the lavish hall, his gaze focused on the grand throne of the imperial seat. The twin brothers, Emperor Geta and Emperor Caracalla, sat upon their thrones, their regal figures imposing in their splendor. Their eyes shifted to Marcus as he entered, the rumble of murmurs from the attendants around them quieting instantly at the sight of the victorious general. But their attention soon shifted toward the figure standing at his side.

Y/N stood tall and unwavering, her chains still hanging at her wrists, her head held high with defiance as ever. Her eyes, burning with an indignant fire, glanced across the room, meeting the Emperor’s gaze with unwavering poise. She did not flinch, not for a moment, under the weight of the attention that fell upon her. Her lavender dress, now even more torn and sullied from the journey, clung to her lithe figure. The golden spiral pendant on her hips glinted faintly, despite the dirt that had stained her skin. Even now, she is still beautiful.

Radiantly, stubbornly beautiful.

The Emperor brothers exchanged a look, their gazes moving from Marcus to Y/N. It was Geta, older of the two, who broke the silence first, his eyes widening as he took in her appearance. He had seen many prisoners in his time, but none quite like this woman. Her beauty was undeniable, and it sent an unexpected thrill through him.

“Ah, General Acacius.” Emperor Geta said, his voice smooth, though his eyes lingered a moment too long on Y/N. “You have indeed brought us a most... captivating prize. This one…” He motioned towards the princess with a nod of his head, his tone shifting into something more indulgent, “...is truly the epitome of Greek beauty, is she not?”

Y/N’s eyes flashed with a barely contained contempt, her lips twisting into a thin smile that was anything but friendly. The chains clinked with every slight movement of her hands, but she ignored them as she met Geta’s eyes directly.

“Compliments from a man such as you mean nothing.” The princess replied coldly, her voice laced with acid. “Your words may flatter, but they do not change the fact that you are a man who needs a woman's beauty only to satisfy your own insatiable ego.”

Geta blinked, momentarily taken aback by her harshness. But he refused to let her words strike him down. He leaned forward, attempting to regain his composure.

“Such a sharp tongue.” He smirked, clearly undeterred. “I admire it, Greek. You should be honored by the attention I offer you.”

Y/N recoiled, the disgust clear in her eyes. She took a step back, a deliberate action that sent a subtle but distinct message. The chains that bound her wrists clinked loudly, marking her defiance.

“I am no toy for your amusement.” She shot back, her voice unwavering. “I will not sit idly by and be paraded as some mere decoration for you to ogle. I am a woman of Greece, a noblewoman, a princess and I will not allow you or your Roman bastards to treat me as something less.”

The room fell silent, the tension thick and palpable as her words hung in the air. Marcus, who had been standing off to the side, watching the exchange, remained unmoved. He had anticipated her defiance, expected it even, but there was something in the way she spoke that made the situation feel more personal.

Caracalla, the younger brother, shifted in his seat, his eyes narrowing as he observed the scene. He was more outgoing than Geta, but now he was deadly serious for some reason, his face impassive, his posture rigid. There was something cold in his gaze as he appraised Y/N.

“Enough, brother.” Caracalla spoke, his voice low and firm. He turned his attention to Marcus, the weight of his authority suddenly felt throughout the room. “You’ve brought us the woman as a symbol of Greece’s fall. Let her beauty be the final tribute to their defeat. But do not forget her place.”

Geta bristled at his brother’s intervention, but he quickly quelled any sign of irritation. He turned to Y/N, who had yet to take her eyes off him, her defiance burning like an unquenchable fire.

“You are lucky to stand here.” Geta said, his tone now tinged with frustration. “You may be a prisoner, but your beauty alone might grant you some measure of respect. Do not make the mistake of forgetting where you are.”

Y/N’s lips curled in a bitter laugh, her gaze never wavering from Geta’s. “Respect?” She scoffed. “You think I would ever accept respect from the likes of you, a man who hides behind the power of an empire to get what he wants? You are nothing but a coward, wearing a crown that is built on the suffering of others.”

The words struck like a slap, and for the first time, Geta’s expression faltered. His lips parted, as though ready to retort, but no words came. He was taken aback, not by her beauty this time, but by her sheer audacity. Y/N L/N was not like any prisoner he had encountered.

Marcus stepped forward, his voice firm, interrupting the tense silence that followed Y/N’s insult. “Enough.” He commanded, his eyes narrowing as he addressed both emperors and the princess of Greece. “She may be a prisoner, but I will not tolerate her disrespect toward you, Emperor Geta.”

But Geta raised a hand, signaling Marcus to silence himself. “It is not her disrespect I care for, General.” He said slowly, his gaze still focused on Y/N. “It is her spirit that intrigues me. She may not be a toy, but she certainly is a challenge.”

Caracalla leaned forward then, his eyes narrowing with cold calculation. “Perhaps it is that very spirit that will make her valuable to us, Marcus. Not only as a symbol, but as a reminder to Greece of the cost of defiance.”

Marcus nodded, but his thoughts were elsewhere. Y/N had defied not just the Roman soldiers who had captured her, but the very authority of the Emperors themselves. The fire within her, that unyielding strength, was both admirable and troubling. He could not deny that it intrigued him, and perhaps even unsettled him in ways he had not expected.

“We will see if she can be tamed.” Marcus said under his breath, his gaze lingering on Y/N, who stood before the Emperors with her head held high, still refusing to bow to any of them.

The crowds around them continued their celebration, oblivious to her defiance, to the fire that still burned in her heart. They cheered for Marcus Acacius, the man who had brought them victory, the man who had crushed Greece beneath Rome’s boot. But as he took his place at the center of the stage for the Emperors to reward him for his victory, his eyes flickered briefly back toward Y/N. In the midst of the grandeur and adoration, something within him stirred. She was different from the other prisoners he had taken. She wasn’t broken. She wasn’t like the others who had begged and cried for mercy. There was a strength in her—a fire—that he had not expected.

As the evening wore on and the celebrations continued, Marcus could not shake the thought of her. He had conquered Greece, but in Y/N L/N, he had found a challenge unlike any other, a challenge that could not be measured in battles or bloodshed.

For in the end, it wasn’t Greece that had fallen. It was something far more elusive. Something he would need to reckon with in the days to come.

And Y/N, even in chains, had left her mark on him.

-----

The grand marble halls of Marcus Acacius’s home were starkly different from the humble yet regal surroundings Y/N L/N had once known in Greece. Here, everything gleamed with the opulence of the Roman Empire, gilded statues of past emperors staring down from every corner, while the walls were adorned with intricate mosaics depicting Roman conquests and celebrations. The air was thick with the scent of fresh flowers and the ever-present undertone of wealth.

It was within this imposing estate that Y/N found herself, though not as a guest, not as a noblewoman of Greece, but as a lowly servant—reduced to the status of a mere scullery maid.

The irony was not lost on her.

Once, she had stood proudly by the side of a general whose name echoed through the halls of Greece. She had been a woman of power, of influence. Now, her wrists were bound by the very chains she once wore as a prisoner, yet now they were metaphorical as well as literal. The chains of servitude were a constant reminder that she had fallen far from grace.

Y/N was led through the grand halls, the whispers of Roman servants and soldiers falling silent at the sight of her, the once proud and beautiful woman now relegated to the task of cleaning, scrubbing, and serving the very man who had stripped her of everything she held dear. She walked with her head held high, though the weight of it all bore down on her. Her eyes never once flinched from the ground, for she would not give them the satisfaction of seeing her beaten down.

“Clean the kitchens. Prepare the meal.” The steward ordered coldly, handing her a wooden bucket and a scrubbing brush. Y/N didn’t respond, her expression unreadable, her thoughts a turbulent storm inside her mind. The very thought of serving Marcus Acacius, the man who had caused the death of her lover and conquered her homeland, was a bitter pill she could hardly swallow.

But she would not show them weakness. Not here, not in Rome.

With measured steps, she moved to the kitchens, the servants parting before her as though she were some shadow from the past, lingering just outside their world. The clang of pots and the simmer of the fires seemed distant, muffled by the thoughts clouding her mind.

As the princess of Greece set to work, scrubbing the floor with practiced precision, her thoughts wandered back to the day she had been captured. She had been clutching her husband’s lifeless body in her arms, her grief as palpable as the air she breathed. And then, the soldiers had come for her. They hadn’t allowed her the dignity of mourning. They had ripped her away from the battlefield, from her husband’s side, and dragged her to this cold, heartless city, forcing her to exist as nothing more than a trophy of war.

She had been nothing but a prize.

Her thoughts were interrupted by the sound of footsteps approaching, heavy and deliberate. Y/N’s heart quickened for a moment, but she steeled herself, returning to her task. She would not look up.

“Still working, I see.” Marcus Acacius’s voice rang out from the entrance, smooth and commanding.

Y/N’s body tensed. She recognized his tone, the authority in his voice. But she refused to give him the satisfaction of seeing her lookup, so she kept her gaze fixed on the floor as she continued to scrub.

“You know, Greek, I could have chosen any number of positions for you.” Marcus continued, his voice tinged with something unreadable, his footsteps approaching closer. “But I thought this would be the most... fitting.”

Y/N’s breath caught in her throat for a brief moment before she exhaled sharply through her nose, still not looking at him. “Fitting?” She repeated, her voice low but sharp, laced with disgust. “You think it fitting to reduce me, a Greek royalty, to the level of your servants? To have me crawl on the floors, cleaning after the very man who has destroyed everything I once knew?”

Marcus chuckled, a sound that did not reach his eyes. He moved to stand just behind her, watching her work. “It is nothing personal, Greek. It is simply the way of things. Rome is the victor, and the spoils of war are always claimed by those who have the strength to take them.”

Y/N paused for a moment, the brush still in her hand as her mind raced. She wanted to lash out, to throw every insult she had ever known in his face. But she knew better. She was not yet broken, not yet defeated.

Without turning to him, she replied, her voice steady, though tinged with defiance. “And I suppose you believe this will make me accept my place here. As your slave. As your property.”

Marcus did not respond at first. The silence between them stretched long, almost painfully, until Y/N felt his presence move, his hand grabbing a hold of her face as if to force her to turn and look at him.

She froze, but only for a moment.

Slowly, she lifted her gaze to meet him, her eyes locking onto his with a piercing intensity that could cut through any pretense of control he might have. His expression was unreadable, but there was a glint in his eyes that was unmistakable, a recognition of the strength he still held over her.

“You are my property, Greek.” Marcus said, his voice quiet, yet it carried the weight of something deeper. Something more complex than he had let on. “But you are here because I choose to keep you. You will remain under my roof, in my service, and you will learn your place in Rome, as all those who come here must.”

Y/N’s pulse quickened, the words slicing through her like a dagger.

“You may have conquered my homeland, Marcus Acacius.” She said, her voice soft but firm. “But you will never conquer me. I will not bow to you. Not ever.”

For a moment, Marcus stared at her, his face unreadable. Then, without a word, he turned and walked away, his steps echoing in the quiet room.

Y/N, left alone in the kitchen, let out the breath she had been holding. Her heart raced, and her fingers gripped the scrub brush so tightly that her knuckles turned white. But there was no break in her posture, no crack in the armor she had carefully crafted. She would never be a slave, not in spirit, not in heart. Not while there was breath in her body.

She would bide her time.

Rome may have won the battle, but Y/N had not yet given in. She was still the proud woman of Greece, and that, above all, was something they could never take from her.

-----

The following days blurred together, each one melding into the next like the rhythmic motion of a pendulum. Y/N L/N, now a permanent fixture in Marcus Acacius’s home, continued her duties as a maid, a servant, words that burned her tongue each time she was forced to acknowledge them. The once proud princess of Greece had been reduced to the very thing she had despised most, and yet she did not break. Her heart remained unyielding, a shield against the constant reminder of her fall from grace.

Marcus Acacius, ever the commander, never let her forget what she had lost.

He would pass her in the hallways, his eyes sharp as they raked over her form, and often, his gaze lingered just a little too long, as if he were savoring the power he wielded over her. His presence was a constant shadow over her existence, a reminder of the world she had once been a part of and the one she now lived in. He would sometimes stand by her as she worked, arms crossed over his chest, his voice dripping with mock sympathy.

“Do you miss it, Greek?” He would ask, his tone tinged with something like amusement. “Your home, your people, the life you once had?”

She would not look up at him, nor would she allow her hands to tremble. She would continue to clean, to cook, to serve as though the weight of his words didn’t crush her heart. But deep inside, they did. They always did.

“I miss nothing.” She would say, her voice as cold and steady as the marble floors she scrubbed.

“Nothing but my dignity, which you’ve stolen.”

He would laugh at her response, the sound rich and full of mirth, as though her defiance was something to be enjoyed. It was never the same with him. With every word, every glance, Marcus reminded her that she had been conquered. That she was nothing more than a prisoner of war.

Yet Y/N never let him see how much it hurt. She couldn’t. If she did, it would be the last victory he would have over her.

Her life in his home was a series of monotonous tasks: cleaning, preparing meals, ensuring the needs of his household were met. There were moments when she thought she might slip into despair, moments when the weight of it all threatened to drag her under, but she would not allow it.

Instead, she found solace in the little rebellions, the small moments where she could still maintain some semblance of her former self. She refused to let her appearance suffer. Each day, she would pull her hair into the same high ponytail, the curls at the tips still framing her face with defiance. She kept her eyes sharp, and though they were often filled with the storm of emotions she refused to acknowledge, they never betrayed her.

Her lavender dress, the fabric faded and worn, still clung to her form in the same graceful way it always had. She did not let her clothing become as tarnished as her soul had been made to feel. Even in this prison, she was still Y/N L/N, and she would not let the Romans take that from her.

As for the other servants, they treated her with a mixture of pity and fear. Some avoided making eye contact with her, while others whispered behind her back, no doubt curious about the woman who had once been a princess in Greece and now slaved away in the kitchens of the man who had brought her to this state. Yet Y/N paid them no mind. They were as much a part of the system that had enslaved her as Marcus himself.

There were times when the bitter taste of loss would surge within her, when she would remember her husband, her beloved general, his body cold in her arms, the blood of her people staining her hands, and the sight of the Roman soldiers advancing, led by Marcus Acacius, ready to tear apart everything she had known. In those moments, the anger within her would rise like a firestorm, and she would clutch the scrub brush in her hands, tightening her grip until her knuckles ached.

One day, after Marcus had casually reminded her of the “grace” he had shown in taking her as a servant rather than disposing of her like the many other prisoners of war, Y/N could no longer hold her tongue.

“I hope you are satisfied.” She spat, her voice dripping with venom. “The great Roman general who has everything, and yet still takes pleasure in tormenting those beneath him. Have you no shame, Marcus?”

He stood there, arms folded, watching her with an unreadable expression. “Shame?” He asked, his voice low and dangerous. “You think I should feel shame for winning a war? For doing what was necessary for Rome’s future?”

Y/N’s lips curled into a sneer. “You have won your war, Marcus. But you will never win what truly matters.”

He stepped closer to her, the tension between them crackling in the air. “And what is that, Greek? What could you possibly think I could still lose?”

She met his gaze with defiance, not an ounce of fear in her eyes. “You may have taken my land, my home, my husband, my people.” She said, her voice firm despite the tightness in her chest. “But you will never break me. Not like you think.”

For a moment, neither of them spoke. The silence was thick with the weight of their unspoken words. And then, as if sensing that this was a battle he could not win, Marcus gave a low laugh.

“You’re stubborn, I’ll give you that. But stubbornness won’t save you, Greek. Not here.”

Y/N’s lips curved into a small bitter smile as she turned away to continue her work. “Maybe not.” She said, “But it will make it harder for you to enjoy your victory.”

Marcus didn’t respond, but the silence between them held a tension that was almost palpable. He may have conquered her body, her lands, her people but he had yet to break her spirit.

And as long as that spirit remained unbroken, Y/N L/N would continue to hold her head high, even in the face of defeat. The proud princess of Greece would not be erased, not by the man who had taken everything from her.

The battle was not over. Not yet.

-----

The air in Marcus Acacius's chamber felt heavier than usual that evening. He stood before the polished bronze mirror, adjusting his armor with careful precision. A meeting with the Emperor Brothers, Geta and Caracalla, awaited him in the Imperial Palace, and this time, the stakes felt higher than they ever had before. The whispers of Rome’s power growing ever more insatiable echoed in the back of his mind. He had been to countless meetings before, each one a seamless blend of politics and strategy, but something gnawed at him now.

Something unsettled him.

He adjusted his golden breastplate, the eagle of Rome etched onto the surface gleaming in the dim light. His soldiers, his trusted men, awaited him just beyond the door, ready to follow him to the heart of power. He took one last look in the mirror, making sure every part of his uniform was immaculate, before he turned sharply and left, his boots echoing in the corridor.

The Imperial Palace loomed ahead, its towering columns and marble statues a testament to the glory of Rome. He entered the grand hall where the generals and high-ranking soldiers stood in quiet anticipation, all waiting for the Emperor Twins to make their appearance. The atmosphere was thick with tension, a mixture of respect and trepidation filling the space.

When Geta and Caracalla finally entered, the room fell silent. The emperors were imposing figures, their presence commanding attention without the need for words. The men in the room straightened in their positions, and Marcus instinctively joined them, standing tall as he awaited their instructions.

Emperor Geta, always the more vocal of the two, stepped forward and addressed the gathering. “Today, we discuss the future of Rome.” He began, his voice carrying through the hall like the roll of thunder. “Our recent victory over Greece was a success. The fools didn’t see through our plans during our times of alliance with them. And because of that, we had our perfect opportunity to devise our revenge against them. And now, we have come out victorious thanks to our beloved General Acacius.”

Marcus, though silent, could feel the weight of the words settle in the pit of his stomach. An alliance with Greece? He had been a part of that conquest, had witnessed the fall of the Greek resistance, but something didn’t feel right upon knowing that Rome and Greece once had an alliance before he led the war against them. Why wasn’t he made aware of this?

Just as he opened his mouth to voice his concerns, Geta raised his hand, signaling for silence. His voice was quiet, almost soothing compared to his brother’s.

“The alliance was, indeed, a symbol of strength and prosperity for Rome.” Geta said, “But there were... complications we must address. It seems that Greece, despite the appearance of peace, still harbors those who wish to undermine our authority. The idea of a peaceful future with them was... flawed. So we decided what needs to be done.”

The room tensed at his words, but it was not the words themselves that caused Marcus to freeze in place. It was the shift in the air, the realization that the peace spoken of was nothing more than a deception..

Caracalla’s gaze shifted to the gathered officers, and his voice grew colder, more commanding. “Rome will never be a weak empire. We will not allow Greece to escape the consequences of their actions. We have made a pact with them, until the time for peace is over.” He smiled darkly. “We have declared war on them. Not because we must, but because we can.”

The words were like a thunderclap in Marcus's mind. He felt the ground beneath him shift, as though the earth itself had split in two. The shock that followed left him numb. Betrayal. It was not the Greeks who had broken their word, it was Rome.

“I am not sure I understand, my Emperor.” Marcus said, his voice betraying the confusion that churned within him. “We were allies with Greece. The alliance was forged to ensure peace, was it not? Surely…”

“Surely?” Caracalla interrupted, his smile twisting. “Do you not understand, Marcus? Power is not to be shared. We, Rome, cannot allow another empire to rise higher and shine brighter than ours. The Greeks were weak and blind, but they are proud, and that pride makes them dangerous.”

Marcus’s mind reeled. He had been the instrument of their destruction, the force that crushed their armies, and now he understood. It was never about peace. It was about control. The so-called alliance of peace was simply a tool to lure Greece into a false sense of security, so that they could strike. It was never about honor. It was about dominance.

“Are you telling me that all of this was a lie?” Marcus asked, the weight of the truth settling over him like a suffocating blanket. “That the alliance was nothing more than a ploy to deceive Greece into lowering their guard?”

Geta’s eyes narrowed. “It was a necessary deception.” He replied. “Your task was simple, Marcus, to win the war for Rome. The rest is beyond your concern. We finished what was started, and Rome will remain supreme.”

Marcus stood still, his chest tightening with the unbearable truth. He had been the one to end the war, the one to force Greece to its knees, and now he saw it for what it was: a grand scheme. They had never intended to honor their word. It was always a game, a twisted game where the lives of thousands were simply pawns on a board.

But in that moment, something deep within Marcus shifted. A cold, simmering fury began to rise within him, tempered by a gnawing sense of guilt. He had been used, but worse, he had participated in the destruction of a people who had done nothing to deserve this.

In the midst of the Emperors’ plotting and the conversation that followed, Marcus’s mind wandered back to Y/N. Her defiant eyes, her proud posture despite her circumstances, it was as if she knew, deep down, that the war had been a lie all along. That the Romans had never come to liberate, but to conquer. And in that, perhaps she had seen through the facade long before he had.

As the meeting drew to a close, Marcus left with a growing sense of disillusionment. The promise of Rome’s strength and prosperity felt hollow in his chest. The empire he had sworn to serve was no different than the villains he had fought against.

It was a painful realization, one that twisted the very foundation of his beliefs. The man who had fought for peace now found himself tangled in a web of lies.

And as the Emperor Twins reveled in their power, Marcus Acacius stood on the precipice of his own understanding, he was no longer certain where his loyalty lay.

-----

The days in Marcus Acacius’ villa were slow, stretching like the long shadows of a fading sun. Y/N had grown used to the monotonous rhythm of servitude, the quiet indignities, the whispered snickers of other servants, the weight of a life reduced to menial tasks. She had expected cruelty from her Roman captor, expected to be treated as nothing more than a disposable relic and reminder of the people the general had conquered.

But what she had not expected… was kindness.

It started subtly.

The harsh orders ceased. No longer was she forced to scrub floors until her fingers bled or serve the Roman general in humiliating silence. Her tasks became lighter, her burdens lessened.

Then came the offerings.

A warm cloak placed over her shoulders on a particularly cold morning. A fresh loaf of bread left on the table when he knew she hadn’t eaten. A goblet of wine pushed toward her at supper, his dark eyes watching, waiting.

Y/N ignored it all. She refused to accept his feigned kindness, refused to acknowledge whatever twisted sense of guilt had taken root in his mind.

She was no damsel in distress.

And she certainly did not need Marcus Acacius, her enemy, her captor, to start playing the role of her reluctant savior.

On the fourth day of his strange, unspoken shift in behavior, Y/N had finally had enough.

She stormed into the atrium of the villa, where Marcus stood in quiet contemplation, staring out into the courtyard. His dark hair was disheveled, his tunic unadorned, the regal formality of Rome momentarily shed. He did not turn when she approached, though he undoubtedly heard her.

Y/N crossed her arms over her chest, her lavender dress swaying as she came to a halt beside him. “You need to stop.”

Only then did Marcus shift his gaze to her. His brow furrowed slightly. “Stop what?”

“This.” She gestured between them, frustration flaring in her eyes. “The kindness. The leniency. The…” She exhaled sharply. “...the pity.”

His expression remained unreadable. “You mistake my actions for pity.”

“Oh, please.” She scoffed, rolling her eyes. “You’ve treated me like an insignificant speck of dust ever since you dragged me to Rome. And now, suddenly, you’re giving me warm cloaks and extra food? What am I supposed to think?”

Marcus studied her for a long moment.

Finally, he spoke. “Perhaps I was wrong to treat you as nothing.”

Y/N’s breath hitched, just barely, just for a second. But she quickly masked it with another scoff. “A little late for that realization, don’t you think?”

Marcus turned to fully face her now. “I will not ask for your forgiveness, nor will I insult you again by pretending that you deserve it.” He exhaled, tilting his head slightly. “But I will not treat you as if you are less than what you are anymore.”

She hated the way his words stirred something unfamiliar in her chest, something she quickly smothered beneath her fury.

“I do not need your guilt, Marcus Acacius.” She said, voice sharp as a blade. “I do not need your atonement. I am not some tragic, delicate flower you must tend to.”

His lips twitched in what might have been the ghost of a smirk. “No.” He agreed. “You are not.”

Y/N blinked, caught off guard by his easy agreement. She had expected him to refute her, to insist upon his newfound chivalry. But no, Marcus Acacius was not a man prone to embellishment.

“I am simply attempting to make amends.” The general said.

She let out a humorless laugh. “Amends?” Her eyes gleamed with something fierce, something unbroken. “You cannot undo what has been done. You cannot undo Greece’s fall. You cannot undo…” Her voice faltered, for just a breath. “...what you took from me.”

The air between them grew heavy. Marcus did not look away.

“I know.” He murmured.

For a moment, neither of them spoke.

Then, Y/N let out a sharp exhale, stepping back. “Just stop it.” She muttered, turning away from him. “I don’t need your kindness. It’s wasted on me.”

As she walked away, Marcus watched her retreating figure, something unreadable flickering across his face.

Because, despite her words…

He wasn’t so sure if he'd ever stop.

The days that followed their confrontation were strange, to say the least.

Y/N had expected Marcus Acacius to return to his usual self, stoic, commanding, the ever-dutiful general of Rome. But instead, he had become… irritatingly attentive.

He had not lessened her work, she was still a slave in his household after all but there was a shift in his demeanor, a softness in his approach that made her wary. He no longer barked orders at her like some barbarian. Instead, he asked if she was well. He offered her food from his own table instead of letting her eat with the other servants. He even, gods forbid, tried to make decent conversation.

Y/N, of course, was having none of it.

"Oh, so now you suddenly care about my well-being?" She remarked one evening, crossing her arms as she leaned against the doorway of the grand dining hall.

Marcus, seated at his table, merely sighed. "I have always cared for your well-being, Y/N."

She scoffed. "Oh, yes, I can see that. How thoughtful of you to drag me from my home, chain me like an animal, and make me scrub the floors of your villa. Truly, a paragon of kindness, General."

He set down his goblet, leveling her with an exasperated stare. "I did not know the truth then."

"And now that you do, what? You think offering me grapes and wine will undo what you've done?" She sauntered closer, plucking a grape from his untouched plate and popping it into her mouth. "Hate to break it to you, General, but I am not so easily won over."

A smirk tugged at his lips. "No, I suppose not."

Y/N expected him to snap, to command her back to work. Instead, he just watched her, as if memorizing every quirk of her expression, every flicker of defiance in her eyes. It was unnerving.

And yet… she found herself playing into it.

If he was going to act the part of a repentant soldier, she would make him work for it.

The next morning, Marcus found himself on the receiving end of Y/N’s pettiness.

His prized war cloak, the one gifted to him by Emperor Caracalla himself, was now mysteriously missing. In its place, draped over his chair, was a ratty, threadbare shawl from the servants’ quarters.

"Where is my cloak?" He demanded, pinching the bridge of his nose.

Y/N, passing by with a tray of fresh fruits, barely batted an eye. "Oh, you mean that garish red thing? Looked awfully dirty, so I threw it in the trash."

Marcus narrowed his eyes. "You expect me to believe you suddenly care about the cleanliness of my wardrobe?"

She offered him a saccharine smile. "Of course, Dominus. It is my duty to serve, after all."

He exhaled sharply. "Y/N…"

But she was already walking away, humming a Greek melody under her breath.

Later that evening, as Marcus settled into his chambers, he discovered yet another one of Y/N’s little games.

His usual goblet of wine? Replaced with water.

His ceremonial sandals? Mysteriously swapped with a pair that were two sizes too small.

His bedding? Missing entirely.

Marcus sat on the edge of his bed, rubbing his temples, as the realization dawned upon him, this was not a battle he could win with brute force.

Y/N L/N was a force unto herself, stubborn as a mule and twice as cunning. If he truly wished to atone, to earn her trust… he would have to fight a different kind of war.

A war of patience.

And gods help him, he had never fought a war this maddening.

#chat and chill#x female reader#x reader#pedro pascal#gladiator 2#gladiator ii#gladiator movie#gladiator ll#pedro pascal gladiator#marcus acacius#marcus acacius x reader#general acacius#general marcus acacius#marcus acacius x you#marcus acacius fanfiction#marcus acacius x female reader#marcus acacius x y/n

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

HoO redo-rodeo

So I've been having a lot of thoughts about HoO characters that I'm never going to get around to Actually Writing, so here we go:

The 7 demigods of prophecy being an uneven mix of Greek and Roman annoyed me, so here we have:

Greek: Percy, Annabeth, Piper

Roman: Jason, Hazel, Frank

Nonhuman: Leo

GREEK

PERCY

The Ascendant Godling.

His character arc is him unknowingly becoming a god, slowly drifting away from the mortal perspective, burning up his mortality faster and faster, sacrificing the last of it to strike the finishing blow to Gaea.

Keeps the Achilles Curse and we get to see it acting as a curse, how it cripples his stamina outside of active combat with adrenaline to keep him going. Needs so much more sleep and food, but while on the streets takes ambrosia/nectar to keep awake and moving. Amounts that would kill any other demigod, that he would never take if he had his memories.

Starts ending fights faster becauase he can't afford to draw them out with talking or negotiation, so falls into lethal intensity survival mode very quickly.

Arrives at Camp Jupiter earlier (timelines are messy anyways, but he should spend more time at Camp Jupiter before the Quest). I just want actual description of the bathhouse, the infrastructure, the routines and attitudes. I want to know what makes the Greeks and Romans different!

Goes by Perseus, because that's what monsters and gods know him as. Also for fun omens about being The Destroyer.

Camp Jupiter assumes they're being tested at first, but then assume that he's a god made mortal so Reyna claims his service for the Legion. She sends him on the Quest under Frank as his Task.

Becaue he's Greek, a very powerful unknown demigod older than the usual initiative and unknowingly becoming a god, he's uncomfortable with the crowds of Roman demigods and legacies, so spends a lot of time in the Temples and quiet places talking to naiads and fawns. Put into trainign as a priest for Neptune, to appease the god and keep Percy out of the way. Builds the understanding of Octavian's huge political power as Augur.

ANNABETH

The Powerless Demigod, the Strategist.

The only one without a clearly divine power, but she's spent her life training to make up the difference. Athena Cabin pours over battle plans and mythology books, anything to get an edge. She doesn't get magic weaving powers, but they all learn and practise weaving to honour their Mother's domain. Big ephasis in Athena Cabin of Athena always being the best and the wisest and Right and that whould never be questioned (which drove initial conflict with Percy in first series over parent's rivalry). Put a lot of stock in making Athena proud of her.

Character arc: after being disowned, forced onto a suicide quest that's killed countless siblings before her while on a world-saving deadlined Great Prophecy Quest, with her only magic support disenchanted... Annabeth becomes disillusioned with Athena as a goddess and a mother (because love and respect are earned, not entitled by blood... and with the example of Sally during interactions while searcing for Percy...). She disavows herself as a Child of Athena.

After Gaea: maybe she becomes a priestess to Percy after designing him a temple. Joins Jason as architect to his Potifex Maximus duties, eventually made Immortal as Architect of Olympus (because there's no way she finished redesigning Olympus in the months between the Titan War ending and Percy disappearing).

Tartarus: during the fall, she blindly sews together some of Arachne's tapasteries in the pitch blakcness to make them a parachute to halp survive the landing.

PIPER

The Titan Army Traitor.

Maybe she never got taken to Camp, maybe she did and immediately ran away from it that night or the next day rather than stay at the Hermes Distaster Relief Shelter Cabin. Either way, she gets picked up by the Titan Army cause. People who help her, train her, sympathise with feeling abandoned by the gods to the mercy of monsters. They don't have much, but they're fighting for a better world. They're family. Then things start to change; Luke becomes more Kronos and demigods start to go missing, some on Missions, some to shadowy corners and the satisfied grins of the monsters who were also angry at the gods and should be their allies. Maybe she even met Selena a few times fro Charmspeak training and listened to her sister share her worries and doubts about the Cause... then the Princess Andromeda blows up and she realises the other side are aiming to kill opposing demigods just the same as monsters. She runs before the Battle of Manhattan.

In Lost Hero, she doesn't get immediately Claimed at Camp and knows exactly why. While no one is looking, sacrifices something precious to her to Aphrodite, maybe with a vow of loyalty or something? She is very, very afraid of the gods.

Character alteration: Mean Girl. She puts on a defensive mask of vanity and sensuality, learned for the cameras and honed under the expectations of the Aphrodite Child stereotype. Runs cons with Leo as the face of the opperation, uses perfuumes to hide demigod scent.

Arc: learning to let down her walls and trust the team to have her back. Also, an earned (on both sides) reconicilliation with Aphrodite.

Embodies Aphrodite Areia, the war aspect of her mother's domain. Uses a spear and wears her cabin's enchanted pink armour. Maybe she also gets Katoptris, but parallels of Selena by training with Clarisse for the spear.

Abilities: Charmspeak, empath & emotional manipulation, voice mimicry and minor visual shapeshifting ability (ie. Mystique) for physical features (semi-involuntary with emotional surges, anger makes her teeth sharpen and nails grow points etc.). Innate sailing affinity as part of Aphrodite's domains, a way to connect with Percy.

ROMAN

JASON

The Olymian Champion.

A messy mix of feral wolf and absolute rule stickler. Was raised by Lupa and then learned how to be in human society through the Legion, through the lense of that being human pack dynamics. Human: polite, controlled, often wearing a small smile with no teeth, opperates by strict rules with Reyna offering the more flexible alernative. More than a bit OCD.

Puts the expectations of others above his personal desires and is pushed to be a puppet of the gods. Hera's Champion, Eagle Child of the God King Jupiter, Wolf Cub of Lupa (claimed as her child like Romulus and Remus, calls her mother). Blesing of Lupa gives him slightly pointed ears and teeth.

Appearance: platinum blonde hair that's almost like white lightning, electric blue eyes that glow when using powers, always carries glasses in a special armoured case and is farsighted (because he focuses too much on the bigger picture to see the immediate),

Arc: learning to live life outside of the rulebook. Letting out more wolfish behaviour and being comfortable in himself.

Conflict with Percy as caught between human knowledge of 'powerful stranger of a foreign pantheon' as a threat to protect the Pack against... and wolf instinct subconsciously recognising Baby God with Roman conditioning to kneel in deference.

HAZEL

The Living Ghost.

She came back to life, but spent decades dead and in Asphodel, so different from two-second deaths of Gwen and Jason. Hazel is a dead soul in a living body.

Physical: cold to the touch and always absolutely silent. Someone next to her hears her take a breath before speaking and is unsettled to realise they heard it because it's almost like he wan't breathing before (she was, but less than a normal human and completely inaudibly). She watches others with an like a owl-like unblinking stillness, a dark form with glowing eyes like an inverse of her father's sacred barn owl. I kind of also want her skin to be cracked through with veins of immortal gold, because her body was remade to return to life, not just resiscitated, so she would have early practice with manipulating the Mist to look normal.

Emotional: Quiet and kind but ruthless, strongly justice-oriented. Visciousness is its own mercy, especially in combat. Makes a judgement and cannot be swayed from her ruling, but is fair in learning all the contextual information before making decisions about people. A step out of rhythm with the rest of the living.

Hazel's Curse: Thanatos' chains are made out of Stygian Iron and Stygian Ice (frozen Styx water), which tries to rip her dead soul from her living body, freezes her hand to the chain. Frank sacrifices some of his life to her (via stick) to melt her hand off the chain, lighting up her gold-veins with blinding light and breaking her Curse (I just want them holding hands and glowing the gold of gods, this couple of a mortal and a ghost).

Abilities: Pluto domains over earth riches, death and agriculture. Cannon abilities, but after SoN wears cuff bracelets inlaid with gem shards that she can pull out and whip around like a deadly ribbon of shrapnel. Being semi/formerly dead, Hazel has a heightened sense for living things, extending to something agricultural (idk, but would be useful against Gaea, yeah?).

Weapon: Scythe, weapon of Proserpina (Persephony) and death connotations. Would just be cool to have her on Arion with a scythe like a golden Grim Reaper and it diversifies the weapons in the 7.

FRANK

The Cursed Legacy.

Frank is a 4th gen Legacy whose paternal Great Grandfather was a demigod son of Mars, but also secretly Legacy of Neptune by his ancestor marrying Neptune-demigod Shen Lun. Each generation has strived to earn patronage of Mars, but the blessings passed by blood have gotten weaker every generation, indicating losing divine favour. Family blames it on the dishonour of Shen Lun and his Neptune-blood sullying the bloodline.

Frank is essentially mortal, but high social class from heritage of Mars-bloodline-favour and lineage service to Legion.

He can't have any amborsia or nectar, but can carefully use the Roman alternative cures like unicorn draught.

Frank has been trained since childhood to be able to keep up with first-gen demigods in combat and uphold (secretly, to regain) the honour of Mars to the Legion. Would not be an outcast if he wasn't friends with Hazel, but he chose friendship with her over social standing/reputation.

Ended up in 5th Cohort through Octavian's machinations to 'improve the cohort standard', actually a subtle blackmail message that he knows about the fading Favour.

The stick: since Shen Lun (and his dishonourable Legion discharge), every member of his line has been born with one. Using the shapeshifting ability directly correlates to it 'burning' by dissolving in golden light. It also turns strands of hair white like the effect of holding the Sky.

There's not enough divinity in his body to handle the power in his blood. Every use kills him a little bit more, but is it dishonourable to prioritise selfish survival over the safety of his comrades? The survival of the Quest?

NONHUMAN

LEO

The Fading Spirit, the Healer.

Leo is a daimon (immortal spirit with power varying from satyr to minor god like Thanatos), a rustic fire spirit called a Dactyl (insert dinosaur jokes here). Predate satyrs and oreads, male counterpart to Hekaterides and often conflated with Kouretes. Species has almost entirely Faded into extinction.

Dactyls are ancient smiths and healing magicians, mostly associated with Hephaestus like satyrs are with Dionysus, but some individuals with others (like Paionios with Asclepius) always in a supporting role. Children of Anchiale, titanness of the warming heat of fire.

Pretends to be a demigod, disguised by Piper's perfume from Coach Hedge, after praying to Hephaeustus gets Claimed by him as a patron. Leo is Sammy and knew Hazel, protected her from monsters, left Alaska after her death, still has the diamond she gave him.

Abilities: metalworking, fire, maths, cannon abilities, healing and wild dancing.

Role: support role and essentially non-combatant, as no natural fighting ability/instinct like demigods. Engineer on the Argo II and team healer

Calypso: Leo has a lot of life experience all around the world, remebers Olympus being in different places and can catch her up of the world she's missed. By the end of the Quest, Leo is no longer in danger of Fading, Calypso is still immortal and their being together is a more equal deal.

Epilogue:

List of Immortals by the end of the series:

Percy (god), Annabeth (similar to Ariadne), Leo (daimon, but partnering with Calypso would become more level with minor god than satyr).

Other characters: Calypso, Grover (Lord of the Wild), Thalia (Huntress), Tyson, Bob and Damasen eventually.

Possibly Hazel and Frank, acting as soul guides/ psychopomps, otherwise Elysium. Possibly Jason for services as Pontifex Maximus in reviving belief of minor and/or Fading gods and daimons, but he'd probably prefer going to Elysium than staying with the Gods forever. Piper... I can't think of a significant divine link, so probably to Elysium. The immortal among the 7 would visit the Underworld souls, of course.

Camp development:

Romans: Become more inclusive, social development. Opening to trade with Greeks and through them also the Egyptians etc.

Greeks: Become more stablished, societal development. Colonize Ogygia (Calypso tethered it to Long Island) as a safe haven to live in full-time, start building a full Greek society.

#heroes of olympus#cannon rewrite#character redesign#percy jackson#annabeth chase#piper mclean#leo valdez#jason grace#hazel levesque#frank zhang#titan army piper mclean#nonhuman leo valdez#god percy#mortal frank#riordanverse

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of the light-touch worldbuilding/storytelling/dramatic irony moments I really enjoy in Fallout: New Vegas is everything to do with Aurelius of Phoenix, the Legion Slavemaster operating Cottonwood Cove. Nested bit here, right? On first glance it seems like psuedo-Latin gibberish, something grandiose but divorced from meaning, like a lot of the Legion guys- but then you do the double take and realize it's a cognomen, a nickname Romans would receive based on great achievements or conquests-e.g. Scipio Africanus- and that implicitly this is the guy who helped sack the actual former city of Phoenix in Arizona. Stealth Future-imperfect trope, disguised at first glance because "Phoenix" is already a kind of grandiose mythologic-sounding word. And when you realize that, right, it's suddenly very funny, for the same basic reason The Republic of Dave is funny- grandiose terminology juxtaposed with a mundane name from the world we recognize. If it were Aurelius of Boise, Aurelius of Cincinnati, right, there are cities you could use in the pairing that would cause it to parse as much more of an explicit gag. So now it's silly in the way everything about the Legion is silly. But then it wraps back around to actually kind of unnerving, because first off, basically it's an offhand implication of something very nasty having gone down in Phoenix, A City From Real Life That We Recognize, in order for him to have gotten a whole Cognomen out of it. And second, it's obviously not a coincidence that his name doesn't sound dumb. Caesar isn't gonna let a subordinate quote-unquote "earn" a cognomen unless it's useful to him, unless it enhances the brand somehow, and having a guy named "Aurelius of Phoenix" walking around, well, it does do that! It feels calculated. It's not the kind of name that's downstream of cultural decay and half-remembered information. It's another example of how Caesar micromanages his slave army down to their very names, and how he lifts random superficial elements of Roman culture on an ad-hoc basis without integrating any of it on a deeper level. A lot going on, with this one guy's goofy name!

#fallout new vegas#caesar's legion#late night posting so not fully endorsed#but yeah there's a lot going on here#fallout#fnv#fonv#thoughts#meta#effortpost

718 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Soldier and Society in Roman Egypt: A Social History

This is a highly recommended book for anyone who wants to learn more about Roman Egypt. It examines the role a Roman soldier played in Egypt from the reign of Augustus to Diocletian.

For many years, there have been many studies done on the Roman army. Many of the general studies have been popular, however, the more narrowly focused aspects of the Roman army have not gained as much attention. This book focuses on what it was like to be a soldier in Roman Egypt. Richard Alston, Professor of Roman History at the University of London, explores the cultural, economic, and legal aspects of a soldier’s life in this province. It gives readers a new insight into Roman Rule in Egypt after the time of the Pharaohs had long since passed. It is targeted at scholars and general readers alike.

This book is a good overview of the Roman army in Egypt from Augustus to Diocletian. In the first chapter, the author introduces the current state of the field. Roman military historians like Spiedel and Bierly have assumed the goals and ultimate role of militaries have been constant throughout history. Richard Alston criticizes this assertion and reminds us that we cannot assume that the Roman army behaved like modern armies. Alston seeks to identify “what the army was for, what the soldiers did, who the soldiers were and how the army related to the civilian population” (6). He argues that the Roman army in Egypt was organized similarly to other provinces. Furthermore, to a degree, every province had an exclusive cultural record. Chapters Two through Six examine aspects such as where the Roman legions were stationed in Egypt, how soldiers were recruited and how they retired, soldiers’ and veterans’ legal status in Roman Egypt, their daily activities, and how this impacted the Egyptian economy. Each chapter outlines the scholarship for these issues and how they can be improved. In the seventh chapter, Alston focuses on how soldiers interacted with civilians in the village of Karanis in the Fayum. He chose Fayum in northwestern Egypt because it was there that many veterans and soldiers settled. Generations of military families trace their ancestry there, too. Roman soldiers and veterans enjoyed a privileged lifestyle and belonged to the upper level of society. They interacted with the civilians and even married into their families. Alston concludes with the claim that the veterans stationed in Karanis were not the foremost in Romanization. However, it remained a relatively large village despite the minority of Romans.

Chapter Eight is brief and talks about the army reforms of Diocletian and the impact it had on the Roman army in Egypt. Chapter nine is a final chapter that summarizes Alston’s conclusions about Roman Egypt with how the army had an impact compared to other provinces such as Britain. He analyzes this from the evidence at the Vindolanda fort near Hadrian’s wall.

There are two detailed appendices, one offering a significant evaluation of the documentary evidence for each cohort and legion stationed in Egypt and the other reviewing the archaeological evidence for the Roman army stationed in Egypt. The illustrations of five forts in this section provide the reader with helpful visuals of Roman architecture.

This is a seminal work and is highly recommended. The conclusions in each section of the book vary depending on the available evidence. Military historians and general audiences alike will benefit from it. This book is different from other works on Roman Egypt because it focuses on the role of the Roman army in that time. Roman Egypt gives us insight into how the land of the Nile changed after the pharaohs, and this book is a perfect addition.

Read More

⇒ Soldier and Society in Roman Egypt: A Social History

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

The more you think about Jason Grace's life, the more fucked up it gets.

Like, the whole "joined Camp Jupiter as a three year old" thing. We already know Camp Jupiter is fucked up because it places heavy importance on a child army, despite having plenty of demigod adults at hand, but they straight up recruited a three year old into the military. He showed up and got promptly stuck in a barrack for the rest of his childhood.

Like, why?? Why on earth would they do that instead of giving him to someone in New Rome to raise and inducting him into the legion at a respectable twelve??

And who raised him anyway?? A rotating cast of nineteen-year-old demigods?? His bunkmates in the Fifth?? If he was a young teenager I could see that, but he arrived when he was three, was he even potty-trained??? Did he just grow up being educated by bored teenagers and ghosts, watching as demigods arrived and served and retired, being told that he had to be the greatest of them all?? Did he have any other children to grow up with?? Did the legion even consider him different than the other recruits, or did he have to shovel unicorn dung when he forgot his phonics and live with the constant threat of perhaps being sewn into a bag of weasels??

I find it odd that Jason, as a demigod who grew up in a demigod's world, doesn't have his unique perspective explored more. I find it especially odd that the difference between his childhood and everyone else's is ignored. However difficult and varied everyone else's backgrounds are, they've at least attended a school. They had parents, and family, and a home, at least at one point. They had mortal toys and dwellings and communities that weren't merged inextricably with the myths. They knew where they came from. Do you think Jason, with his powerful, kingly father and impending destiny, ever felt like he didn't know who his family was?

I also find it strange that he doesn't seem to have a very wide network of friends from Camp Jupiter? He has Reyna, who he trusts and works with and depends on. He lists Hazel and Frank among his friends, but they look up to him as a role model. He mentions Bobby and Dakota familiarly, but never again. He's familiar and on good terms with basically everyone—but the only person he seems to consider as a close friend is Reyna. And that wouldn't be odd if he hadn't grown up at Camp Jupiter. He doesn't seem to have any constant companion—anyone he considers his family until he meets Leo.

Maybe he and Leo bonded so well because they both knew what it was like to grow up transiently. To have any constant in your life, and know that the day you would move on or they would move on was fast approaching. Maybe the reason he looked at Camp Half-Blood and admired how united and familial they seemed, and wished Camp Jupiter could be similar, was that he could see in them the family he wished he had.

Honestly, I feel like meeting Thalia should have left him in a lot more turmoil than it did. He grew up with no family but a god for a father, and here's a person who wanted him. Someone who always wanted him because he was Jason, and not the demigod son of Zeus. Maybe even someone to whom he mattered more than his destiny.

I really, really wish we'd gotten to see more of the contrasts between him and Percy. He is explicitly the Romans' version of the hero Percy is, except he's the hero first, and the person second. Jason did everything right! He did everything perfectly, and Percy still got where he did without being trained for it his entire childhood. He's got such a better reason to resent him than "bad vibes". They could have been foils for each other hhhhhhhrngh.

Just. This lonely, idolized, child soldier's life hurts me.

#and honestly i want to know all about his life before HOO#all the quests he went on! the friends he made! what shaped him into the person he is today!#his identity problems should run deeper than “i like the greek way but i was born a roman” and “i find it difficult to process the kind of#person my mother was"!#riordanverse#heroes of olympus#jason grace#heros of olympus

335 notes

·

View notes

Note