#Ladinian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Triassic palaeofauna of Miedary locality

#not very serious palaeoart#triassic#ladinian#miedary#temnospondyl#mastodonsaurus#bystrowiella#gerrothorax#owenettidae#blezingeria#what blezingeria even was? the mystery#tanystropheus#(the site is mostly them)#nothosaurus#jaxtasuchus#archosaur#saurichtys#serrolepis#prohalecites#who's missing? the lungfish#can't believe I forgot the lungfish#the best bit

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Crocs of 2024

Another year another list of new fossil crocodilians that greatly expand our knowledge of Pseudosuchia across deep time. Happy to say that this is my third time doing this now, so I'm not going to bog you down with the details and get right into it.

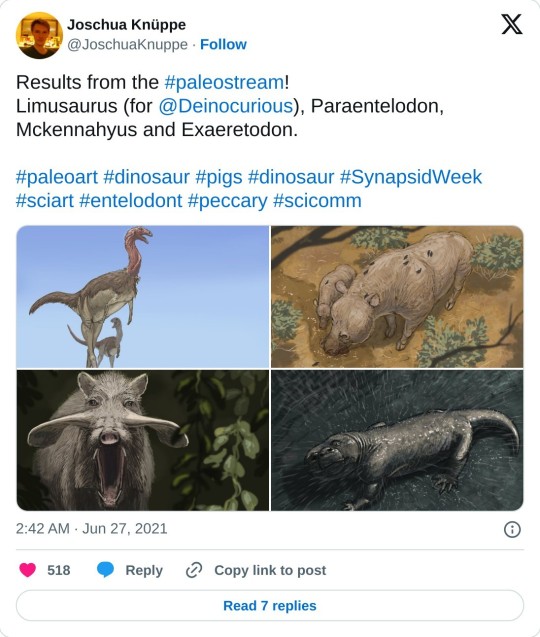

Benggwigwishingasuchus

Our first entry, sorted by geological age of course, is Benggwigwishingasuchus eremicarminis (desert song fishing crocodile) from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of Nevada. It was a member of the clade Poposauroidea, which some of you might recognize as also containing such bizarre early croc cousins like Arizonasaurus and Effigia. Also notable about Benggwigwishingasuchus is that it was found in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation. Why is that notable? Well the Fossil Hill Member preserves an environment deposited 10 km off the Triassic coastline and also yielded fossils of animals like Cymbospondylus, the giant ichthyosaur. Despite this however, Benggwigwishingasuchus shows no obvious signs of having been a swimmer or diver. Instead, its been hypothesized that it was simply foraging around the coast and might have been washed out to sea.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe (@knuppitalism-with-ue) and Jorge A. Gonzalez

Parvosuchus

Fast forward some 5 million years to the Ladinian - Carnian of Brazil, specifically the Santa Maria Formation. Here you'll find the one new genus on the list I did not write the wikipedia page for: Parvosuchus aurelioi (Aurélio's Small Crocodile). With only a meter in length, Parvosuchus is amongst the smallest pseudosuchians of the year and a member of the aptly named Gracilisuchidae. Santa Maria was actually home to multiple pseudosuchians, including the mighty Prestosuchus (and its possible juvenile form Decuriasuchus), the small erpetosuchid Archeopelta and larger Pagosvenator and one more...

Artwork by Matheus Fernandes and Joschua Knüppe

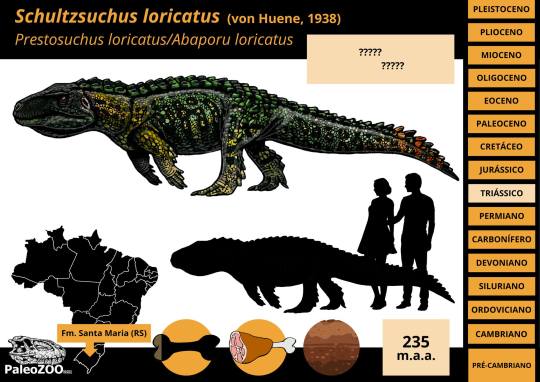

Schultzsuchus

Yup, Santa Maria has been eating good this year. Before the description of Parvosuchus, scientists coined the name Schultzsuchus loricatus (Schultz's Crocodile). Now this one's not entirely new and has long been known under the name Prestosuchus loricatus (by which I mean since 1938). What's interesting is that this new redescription suggests that rather than being a Loricatan, Schultzsuchus was actually an early member of Poposauroidea like Benggwigwishingasuchus. Even if it was no longer thought to be close to Prestosuchus, it was liekly still a formidable predator and among the larger pseudosuchians of the formation.

Artwork by Felipe Alves Elias

Garzapelta

Our last Triassic pseudosuchian and our only aetosaur of the year came to us in the form of Garzapelta muelleri (Mueller's Garza County Shield). It comes from the Late Triassic (Norian) Cooper Canyon Formation of, you guessed it, Garza County, Texas. As an aetosaur, the osteoderms are already regarded as diagnostic, tho unlike some other recent examples there is a little more material to go off from. It's still primarily osteoderms, but at least a good amount and even some ribs.

Artwork by Márcio L. Castro

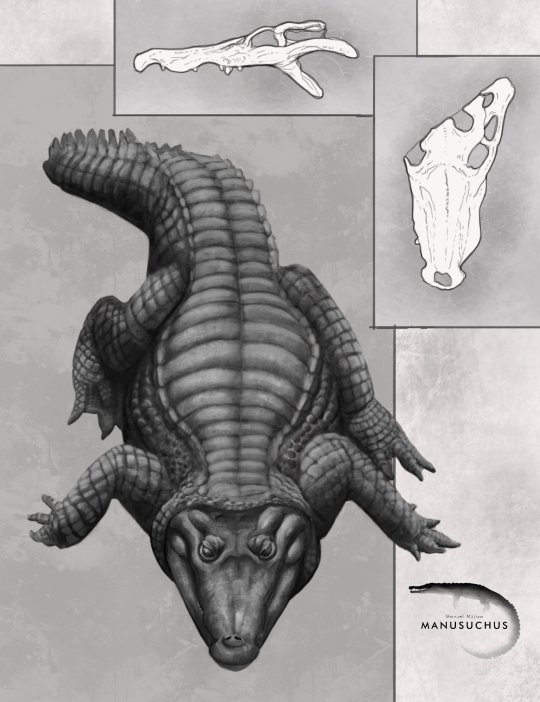

Ophiussasuchus

Our only Jurassic newcommer is Ophiussasuchus paimogonectes (Paimogo Beach Swimmer Portuguese Crocodile), but arguably you couldn't find a better posterchild for Jurassic crocodyliforms. This new lad is a goniopholidid from the Kimmeridgian to Tithonian Lourinhã Formation, yup, Europe's Morrison. It's anatomy is perhaps not the most exciting, like other goniopholidids it had a flattened, very crocodilian-esque snout and was likely semi-aquatic like its relatives.

Artwork by @manusuchus and Joschua Knüppe

Enalioetes

Another quintessential group of Jurassic crocodyliforms are the metriorhynchoids, however, 2024's only new addition to this clade was actually Cretaceous, specifically from the earliest Cretaceous (Valanginian) of Germany. Like Schultzsuchus, Enalioetes schroederi (Schroeder's Sea Dweller) is new in name only, as fossil material has been found at the latest in 1918 and given the name Enaliosuchus "schroederi" in 1936. This kickstarted a whole series of taxonomic back and forth until the recent redescriptoin finally just gave it a new name and settled things (for now). Looking back I realize that I really need to take the time and fix up the Wikipedia page. Tho I've written its current status, I was kinda limited by being on vacation and never dived into the description section.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe and Jackosaurus

Varanosuchus

Another Early Cretaceous crocodyliform is Varanosuchus sakonnakhonensis (Monitor Lizard Crocodile from the Sakon Nakhon Province), described from Thailand's Sao Khua Formation. It lived around the same time as Enalioetes, but otherwise couldn't have been more different. Where Enalioetes was fully marine, Varanosuchus was more a land dweller as evidenced by the deep skull and long, slender legs. At the same time, some other features, like its more robust limbs compared to its kin, might suggest that Varanosuchus could have still spent some time in the water like some modern lizards. Tho one might be reminded of Parvosuchus from earlier, Varanosuchus is a much more recent example of small terrestrial croc-relatives, the atoposaurids, which are much closer to todays crocodiles and alligators.

Artwork once again by Manusuchus

Araripesuchus manzanensis

Yet another example of a small, gracile land "crocodile" comes to us in the form of Araripesuchus manzanensis (Araripe Basin Crocodile from the El Manzano Farm). And once again, it belonged to a completely different group, this time the notosuchian family Uruguaysuchidae. Now Araripesuchus is well known as a genus, in part due to the work of Paul Sereno and Hans Larsson (who popularized the names "dog croc" and "rat croc" for two species). Tangent aside, A. manzanensis is known from the upper layers of Argentina's Candeleros Formation, corresponding to the Cenomanian (earliest Late Cretaceous). The same locality also yielded A. buitreraensis, from which A. manzanensis can be distinguished on account of its blunt molariform teeth in the back of its jaw. This dentition, which corresponds to a durophageous diet of hardshelled prey, could explain how it coexisted with the related A. buitrensis at the same locality, allowing the two to occupy different niches. There is a neat little animation done for this animal you can watch here.

Artwork by Gabriel Diaz Yantén

Caipirasuchus catanduvensis

We're staying in South America but moving to Brazil's Adamantina Formation for our next entry: Caipirasuchus catanduvensis (Caipiras Crocodile from Catanduva). This one is a little more recent, tho the age of the Adamantina Formation is a bit of a mess far as I can tell, ranging anywhere from the Turonian to the Maastrichtian. One could also argue that C. catanduvensis is part of the "lanky small croc club" that Parvosuchus, Varanosuchus and A. manzanensis belong to, but I feel that the very short snout helps it stand out from that bunch more easily. Anyhow, Caipirasuchus catanduvensis is a member of Sphagesauridae, related to Armadillosuchus, and herbivorous. What's really interesting tho is that the internal anatomy suggests the presence of resonance chambers not unlike that of hadrosaurs, possibly suggesting that these animals were quite vocal. This could also explain why baurusuchids appear to have had very keen hearing.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe and Guilherme Gehr

Epoidesuchus

We're staying in the Adamantina Formation for our last Mesozoic croc of the year, Epoidesuchus tavaresae (Tavares' Enchanted Crocodile). Tho also a Notosuchian like Araripesuchus and Caipirasuchus, this one belongs to the family Itasuchidae (or the subfamily Pepesuchinae depending on who you ask), which stand out as being rare examples of semi-aquatic members of this otherwise largely terrestrial group. Epoidesuchus was fairly large for its kin and had long, slender jaws. Like I said, Epoidesuchus and its relatives were likely more semi-aquatic than other notosuchians, something that might explain the relative lack of semi-aquatic neosuchians across Gondwana. They aren't absent mind you, but noticably rarer than they are in the northern hemisphere.

Artwork by Guilherme Gehr

And thus we move into the Cenozoic and towards the end our or little list. From here on out, say goodbye to Notosuchians or other weird crocodylomorphs and get ready for Crocodilia far as the eye can see.

Ahdeskatanka

The first Cenozoic croc we got is Ahdeskatanka russlanddeutsche (Russian-German Alligator), which despite its name comes from North Dakota, specifically the Early Eocene Golden Valley Formation. Ahdeskatanka is similar to many early alligatorines like Allognathosuchus in being small with rounded, globular teeth that suggest that it fed on hardshelled prey. This would have definitely helped avoid competition in the Golden Valley Formation, which also housed a second, similar form not yet named, a large generalist with a V-shaped snout similar to Borealosuchus and the generalized early caiman Chrysochampsa, also large but with a U-shaped snout.

Artwork by meeeeeeee

Asiatosuchus oenotriensis

We had an alligatoroid, so now its time for a crocodyloid. Asiatosuchus has been recognized from the Late Eocene Duero Basin of Spain for a while now, but now we have a name: Asiatosuchus oenotriensis (Asian Crocodile Belonging To The Land Of Wine). Asiatosuchus is a complex genus, most often not really forming a monophyletic clade and likely representing several distinct or at least successive taxa that form the "Asiatosuchus-like complex". Within this complex, A. oenotriensis is thought to have been close-ish to Germany's Asiatosuchus germanicus.

Artwork by Manusuchus

Sutekhsuchus

Rounding out the trio of major crocodilian clades is Sutekhsuchus dowsoni (Set's Crocodile/God of Deception Crocodile), representing our only gavialoid of the year. Originally described as Tomistoma dowsoni in 1920 based on fossil remains from the Miocene of Egypt, Sutekhsuchus has been at times regarded as distinct and at other times lumped into Tomistoma lusitanica. It was one of several early gavialoids to inhabit the coast of the Tethys during the Miocene and appears to have been most closely related to the genus Eogavialis, clading together just outside of the American and Asian gharials. A fun little personal anecdote, I prematurely learned about this one due to a friend highlighting the name in a study on Eogavialis. Never having heard of "Sutekhsuchus" I took to google scholar, where I found a single result: a reference to the then unpublished description, which naturally I ended up eagerly awaiting.

Artwork by Manusuchus and Joschua Knüppe

Paranacaiman

Two more and we're done. First, completely arbitrarily, Paranacaiman bravardi (Bravard's Caiman from Parana) from the Miocene Ituzaingo Formation of Argentina. Material of this genus has originally been referred to Caiman lutescens, described in 1912 but now considered a nomen dubium. Paranacaiman is known from limited material only, just the skull table, but that would indicate a "huge" animal. My personal scaling recovered a size of almost 5 meters in length, similar to large black caimans today.

Once again, credit to me

Paranasuchus

Last but not least, Paranasuchus gasparinae (Gasparini's Crocodile from Parana). Coming from the same deposits as Paranacaiman, this one too has been known as a species of Caiman for some time before being assigned its own genus, though it at least got to retain its old species name. Alas, I have not scaled it myself, tho its material is at least more extensive than that of Paranacaiman, including even parts of the snout. A little nitpick because I don't have much to say, but I personally think the name was ill conceived. On its own both Paranacaiman and Paranasuchus are fine names don't get me wrong, but together, coined by the same authors in the same study no less, they strike me as needlessly confusing to non experts. Both are caimans, both are from Parana, so the distinction between "Parana Caiman" and "Parana Crocodile" is entirely arbitrary and doesn't really distinguish them. Not helped by the fact that they are even closely related in the original description. Other than that tho another good addition to our understanding of fossil crocs.

No artwork on this one, but fossil material from Bona et al. 2024

And that wraps up 2024. I hope This post, or my posts throughout the year or even my work on Wikipedia has helped to make these fascinating animals just a little bit more approachable and a massive thanks to all the artists who took their time to create fantastic pieces featuring these incredible animals. Special shout outs to Manusuchus, who diligently illustrated a lot of the featured animals and Joschua Knüppe, who had to listen to me suggest Ahdeskatanka every Sunday for about two months straight now.

Fossil Crocs of 2023

Fossil Crocs of 2022

#paranasuchus#paranacaiman#ahdeskatanka#sutekhsuchus#ophiussasuchus#epoidesuchus#caipirasuchus#araripesuchus#enalioetes#parvosuchus#benggwigwishingasuchus#schultzsuchus#garzapelta#varanosuchus#paleontology#prehistory#palaeoblr#long post#fossil crocs of 2024#paleo#paleonotlogy#crocodilia#crocodylomorpha#pseudosuchia#fossils#2024

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

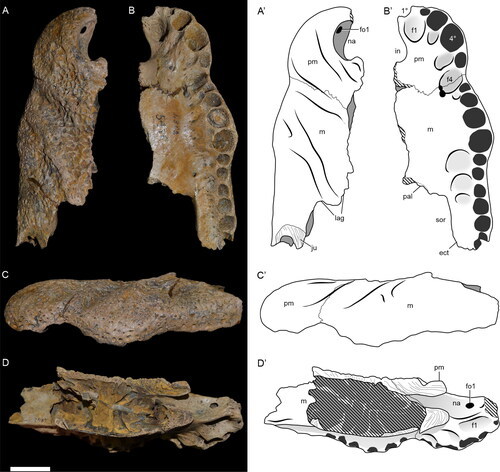

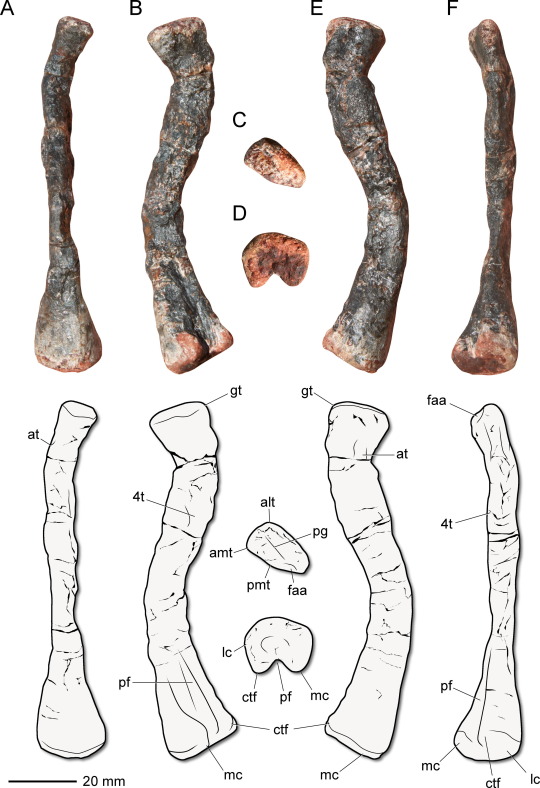

Gondwanax paraisensis Müller, 2024 (new genus and species)

(Type femur [thigh bone] of Gondwanax paraisensis, from Müller, 2024)

Meaning of name: Gondwanax = Gondwana king [in Greek]; paraisensis = from Paraíso do Sul

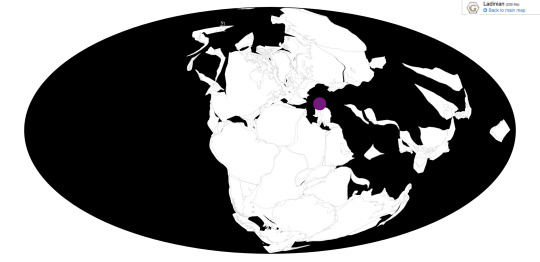

Age: Middle–Late Triassic (Ladinian–Carnian)

Where found: Santa Maria Formation, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

How much is known: A right femur (thigh bone), along with several vertebrae and a partial pelvis from the same site. It is unknown whether the other bones belonged to the same individual as the femur.

Notes: Gondwanax was a silesaurid, a group of probably quadrupedal Triassic reptiles that often had adaptations for herbivory (though there is evidence that they also ate insects). Until recently, silesaurids were generally considered to be close relatives of dinosaurs instead of dinosaurs themselves, and I previously excluded them from coverage on this blog. However, multiple recent analyses have suggested that they might in fact be true dinosaurs, specifically early members of Ornithischia ("bird-hipped" dinosaurs), so from here on out I will tentatively include them within this blog's purview. In fact, some of those studies have found that most "silesaurids" may not have formed a unique evolutionary group, but instead a series of lineages with some being more closely related to later ornithischians than others.

Regardless of whether it is a true dinosaur, Gondwanax is one of the oldest known dinosauromorphs (the group containing dinosaurs and their closest relatives). Compared to other dinosauromorphs of similar age, Gondwanax more closely resembles later dinosaurs in having three hip vertebrae (whereas dinosaurs ancestrally appear to have had only two). It is unusual among dinosauromorphs in having a very small fourth trochanter, a attachment point on the femur for muscles that pull the hindlimb backward.

(Schematic skeletal of Gondwanax paraisensis, with preserved bones in orange, from Müller, 2024)

Reference: Müller, R.T. 2024. A new "silesaurid" from the oldest dinosauromorph-bearing beds of South America provides insights into the early evolution of bird-line archosaurs. Gondwana Research advance online publication. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2024.09.007

#Palaeoblr#Dinosaurs#Gondwanax#Middle Triassic#Late Triassic#South America#Ornithischia#2024#Extinct

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

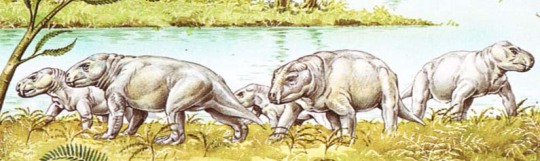

Exaeretodon is an extinct genus of traversodontid cynodont which lived throughout what is now India and South America from the Ladinian stage to the Norian stage of the Triassic period some 235 to 205 million years ago. The naming of exaeretodon seems to have a bit of a complicated history with different specimens having been attributed to various genere such as Belesodon, Traversodon, Theropsis, Ischignathus with the later two genere now considered completely synoyomous with exarertodon. For example the type specimen consisting of a near complete skull was initially described as Belesodon argentines in Ángel Cabrera until with the help of José Bonaparte, they distinquished it as its own distinct genus. Today over 200 specimens have been recovered, some in remarkably good condition including a mother who was preserved pregnant with two calves. Four species are considered valid. E. argentinus from the the Ischigualasto Formation in the Ischigualasto-Villa Unión Basin of northwestern Argentina. E. major and E. riograndensis are from the Santa Maria Formation of the Paraná Basin in southeastern Brazil. And E. statisticae is from the Lower Maleri Formation of India. Reachign some 5 to 6ft (1.5 to 1.8m) in length and 130 to 190lbs (60 to 86kgs) in weight, exaeretodon was a fairly large low-slung creature. Despite its massive jaws and terrifying appearance, studies show its teeth were well developed to grind vegetation meaning that exaeretodon was likely a grazing herbivore. And was on of the most numerous herbivores of the middle and late Triassic southern pangea.

Art used can be found at links below

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

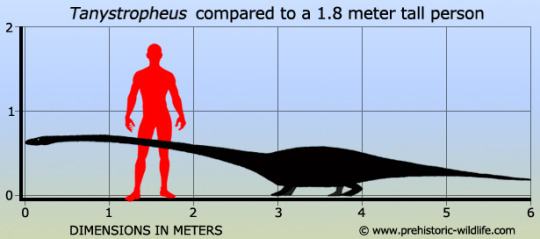

Tanystropheus

(temporal range: 245-235 mio. years ago)

[text from the Wikipedia article, see also link above]

Tanystropheus (Greek: τανυ~ 'long' + στροφευς 'hinged') is an extinct genus of 6-meter-long (20 ft) archosauromorph reptile from the Middle and Late Triassic epochs. It is recognisable by its extremely elongated neck, which measured 3 m (9.8 ft) long—longer than its body and tail combined.[1] The neck was composed of 12–13 extremely elongated vertebrae.[2] With its very long but relatively stiff neck, Tanystropheus has been often proposed and reconstructed as an aquatic or semi-aquatic reptile, an interpretation supported by the fact that the creature is most commonly found in semi-aquatic fossil sites where known terrestrial reptile remains are scarce. Complete skeletons are common in the Besano Formation at Monte San Giorgio in Italy and Switzerland; other fossils have been found throughout Europe, North America, and Asia, dating from the Middle Triassic (Anisian and Ladinian stages) to the early part of the Late Triassic (earliest Carnian stage).

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Geological period names that would be absolute bangers in a fantasy setting:

- Hadean

- Calabrian

- Serravallian

- Lutetian

- Thanetian

- Selandian

- Aalenian

- Sinemurian

- Rhaetian

- Norian

- Ladinian

- Anisian

- Asselian

- Kasimovian

- Famennian

- Calymnian

- Orosirian

- Rhyacian

- Siderian

#fantasy#books#scifi#science fiction#fantasy names#I’m treating school as a fantasy name generator#writing inspo#writeblr#writing#maybe I’ll learn them if I act like they’re fantasy land names#nothing Mesozoic related because it would be ridiculous but yeah

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

VERY RARE 8" CERATITES NODOSUS Ammonite Fossil, Muschelkalk Formation, Ladinian, Middle Triassic: Hollstadt, Germany

This listing features a very rare and beautifully preserved 8-inch ammonite fossil, Ceratites nodosus, from the Muschelkalk Formation. This stunning specimen originates from the Ladinian stage of the Middle Triassic period (approximately 240 million years ago) and was discovered in Hollstadt, Germany. Its remarkable preservation and historical significance make it a highly sought-after piece for collectors and enthusiasts alike.

Key Features:

Species: Ceratites nodosus

Size: 8 inches

Geological Formation: Muschelkalk Formation

Age: Ladinian, Middle Triassic (~240 million years ago)

Location: Hollstadt, Germany

Provenance: From the esteemed Alice Purnell Collection

About Ceratites nodosus and the Muschelkalk Formation:

Ceratites nodosus is a rare and iconic species of ammonoid, characterized by its intricate nodular ornamentation and suture patterns. These marine mollusks thrived in the Triassic seas and are considered a crucial link in the evolutionary lineage of ammonoids. The fossilized remains of Ceratites nodosus provide invaluable insights into the marine ecosystems of the Triassic period.

The Muschelkalk Formation is part of the Triassic Germanic Basin and is renowned for its exceptional fossil preservation. The Ladinian stage, within the Middle Triassic, represents a significant period in Earth's history when marine life was recovering and diversifying after the Permian mass extinction.

Provenance and Authenticity:

This fossil is part of the prestigious Alice Purnell Collection, one of the world's largest and most respected private collections of ammonites and fossils. Each specimen from this collection is hand-selected for its scientific value and aesthetic appeal. This fossil comes with a Certificate of Authenticity, guaranteeing its origin, species, and geological context.

Why This Fossil Is Special:

Very Rare Species: Ceratites nodosus is a highly sought-after ammonoid species, rarely found in such excellent condition.

Exceptional Preservation: The fossil showcases intricate details of the shell and nodular ornamentation, making it a true collector’s piece.

Historic Provenance: From the Alice Purnell Collection, known for its meticulously curated and scientifically valuable specimens.

Geological Significance: Originates from the Muschelkalk Formation, a globally recognized source of high-quality Triassic fossils.

What’s Included:

8-inch Ceratites nodosus ammonite fossil, as shown in the photos

Certificate of Authenticity, providing full documentation of the fossil’s species, age, and origin

Display and Collectability:

This Ceratites nodosus fossil is not only a scientifically significant piece but also a stunning display specimen. Its large size, exquisite detail, and rarity make it ideal for private collections, museum exhibits, or educational displays. Whether you're a seasoned collector or a fossil enthusiast, this extraordinary ammonite will undoubtedly be a prized addition to your collection.

Additional Information:

The fossil has been expertly prepared to highlight its natural features while maintaining its integrity. The accompanying photos depict the exact specimen you will receive, ensuring full transparency.

All of our Fossils are 100% Genuine Specimens and come with a Certificate of Authenticity.

Don’t miss the opportunity to own this very rare 8-inch Ceratites nodosus ammonite fossil from Hollstadt, Germany. A magnificent relic of Triassic history, this fossil offers a unique glimpse into the ancient seas that existed over 240 million years ago!

#ammonite#ammonites#fossils#fossil#genuine specimen#sea fossil#marine animal#amonite#snail shell#fossil specimen

0 notes

Text

Longisquama insignis

By Tas Dixon

Etymology: Long Scales

First Described By: Sharov, 1970

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, ???

Time and Place: 242 million years ago, in the Ladinian of the Middle Triassic

Longisquama is known from the Madygen Formation of Kyrgyzstan

Physical Description: Longisquama was a small, somewhat lizard-like reptile reaching somewhere around 8 or 9 centimeters in body length from snout to tail - though this is uncertain, as tail elements are not preserved at this time. It had very large, hockey-stick shaped scales in a single row going along its back, with some of the longest scales being as long as the body of the animal - or longer, we really don’t have its tail. They go from somewhat long towards the head, reaching a peak length right after this, and then shrink in size as they go towards the tail - probably. Again, we don’t have a lot in terms of preserved elements of this animal, and while we know they were shaped like hockey sticks, there is a chance the fronds may have varied in size or shape or extended more on the back. They were attached to the spine by knob-like attachment points, similar to follicles for other integumentary structures like hair. There was probably soft tissue surrounding this follicle to keep the scale steady. The fronds had a raised ridge down the middle, with horizontal bars going up and down the length of the scale. The head of Longisquama was small, ending in a short point with tiny teeth inside, and it had a small head. It appears to have been quadrupedal - maybe, we don’t really have hind limbs - and with its legs splayed out to the side on its body. It was also quite skinny, based on the size of its ribcage.

Diet: Longisquama was probably an insectivore, eating the variety of different insects that were present in its environment.

Behavior: We really have no idea what the long scaled were used for. They were probably for display, nothing like feathers at all, and would have looked pretty to other Longisquama. They may have even been iridescent, much like many lizard scales, allowing them to display to each other in their deeply green and dense forested environment. There is no evidence that they would have been suitable as flying structures, and honestly beyond that we have no idea. There doesn’t seem to be evidence that they were used like Synapsid sails for cooling, either. Display is the best idea we have at this point. As for other behaviors, it probably would spend a good chunk of time in trees, and may have been social in doing so - the display structures do seem to imply a certain amount of social behavior. As far as parental care or other complex social structures, however, we have no evidence either way.

Ecosystem: The Madygen was a deeply forested environment, with dense coniferous trees surrounding extensive lakes set in deep mud. This very wet and very green environment meant that there weren’t a lot of large animals present - instead, most of the animals were adapted for the trees and catching each other and plantlife among the branches. This extensively muddy and sticky environment means that a wide variety of animals - especially insects - were preserved well in the formation. Other creatures include the leg-glider Sharovipteryx; the Drepanosaur Kyrgyzsaurus; a mysterious probable-salamander Triassurus; a primitive cynodont Madysaurus; the Reptiliomorph Madygenerpeton; sharks such as Fayolia, Lonchidion, and Palaeoxyris; and many ray-finned fishes like Alvinia, Megaperleidus, Sixtelia, Ferganiscus, Oshia, and Saurichthys. As for insects, there too many to list: the earliest Hymenopterans (the group including wasps, bees, and ants); the great Titanopterans like Gigatian; moths, beetles, crickets, mosquitos, flies, grigs, and even mysterious Triassic insects with no close modern relatives. Seriously, you don’t want me to list them all - there’s hundreds of species on Fossilworks alone! So there was plenty for Longisquama to chow down on.

Other: Oh Longisquama. Such a poorly preserved animal. Locked away in Russia, far away from the prying eyes of so many in this world. Unstudied, unloved. And yet, from the few photographs we have of its fossil, so many have insisted - insisted - we know exactly what it is. The enigmatic nature of Longisquama and it's completely poor fossil record (and, again, entrapment in Russia) have left it as a sort of Schrodinger’s Triassic Weirdo. What is it? What is it related to? What are those frond things? Does it play a role in the evolution of other groups?

Here’s the thing, though. Longisquama is so poorly preserved and all we have are pictures of the fossil unless you want to go to Russia, badger some Russians, and look at the fossil - which very few people actually want to do. So, that having been said, we can’t use it for anything, basically, and we certainly can’t say anything about the fossil.

We do know some things:

The long ribbons on Longisquama are not leaves it fell on top of. There are enough fossils of Longisquama to reinforce that it has these fronds every time, and they weren’t really shaped like any known plant leaves anyway. I know, it’s a bummer.

It’s not a Dinosaur. It lacks Archosaur features, as far as we can tell from the fossil photos. So, if it’s not an Archosaur, it’s not a Dinosaur.

It is not a Bird Precursor. While Longisquama - and quite a few other reptiles of the Triassic - convergently evolved similar facial features in the superficial sense to birds, they weren’t actually that similar on the skeletal level - they aren’t archosaurs! - and none of the rest of the skeleton resembles birds. Furthermore, we have one of the best transitional sequences ever known specifically for bird evolution - we have in the fossil record every step of the process from ancestral archosaur to bird, through the dinosaur family tree. The sheer number of feathered dinosaur fossils and other features found in dinosaurs such as similar hand configuration, body shapes, skeletal structures, and behaviors have left no doubt in the minds of the vast majority of scientists that birds are dinosaurs and, therefore, not descendants of Longisquama.

It’s not a Pterosaur precursor. Literally all studies of its classification puts it far away from pterosaurs; furthermore, there are no clear links between Longisquama and the early pterosaurs of the Triassic period. While Pterosaur evolution isn’t quite as clear as bird evolution, we also have decent reason to believe pterosaurs are Archosaurs; meaning, Longisquama isn’t their ancestor.

The fronds aren’t feathers. Even if feathers were that deep in terms of reptile ancestry that it was retained through many stages of evolution from Longisquama to early dinosaurs and pterosaurs, there is no evidence for this trait in living non-avian reptiles like Crocodilians (no, they don’t carry a feather gene, they just have the same protein that feathers are made out of) or Lizards, and thus the odds of these being weird pre-feathers is low. Instead, they are most likely highly modified scales.

So, what is it? We don’t know. Maybe a Drepanosaur (more on those weirdos later). Maybe just a completely separate lineage of Triassic Weirdos. Probably an Archosauromorph? Maybe something else entirely? A Diapsid. We know it was a Diapsid. And that will have to be enough for now.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Alifanov, V. R., and E. N. Kurochkin. 2011. Kyrgyzsaurus bukhanchenkoi gen. et sp. nov., a new reptile from the Triassic of southwestern Kyrgyzstan. Paleontological Journal 45(6):42-50.

Fischer, J.; Voigt, S.; Schneider, J.W.; Buchwitz, M.; Voigt, S. (2011). "A selachian freshwater fauna from the Triassic of Kyrgyzstan and its implication for Mesozoic shark nurseries". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (5): 937–953.

Ivakhnenko, M. F. 1978. Tailed amphibians from the Triassic and Jurassic of Middle Asia. Paleontological Journal 1978(3):84-89.

Sharov, A. G. 1970. An unusual reptile from the Lower Triassic of Fergana. Paleontological Journal 1970(1):112-116.

Sharov, A. G. 1971. Novye letayushche reptilii is Mesosoya Kazachstana i Kirgizii [New Mesozoic flying reptiles from Kazakhstan and Kirgizia]. Trudy Paleontologicheskiya Instituta Akademiy Nauk SSSR 130:104-113.

SHCHERBAKOV, Dmitry (2008). "Madygen, Triassic Lagerstätte number one, before and after Sharov". Alavesia. 2 (5): 125–131.

Tatarinov, L. P. 2005. A new cynodont (Reptilia, Theriodontia) from the Madygen Formation (Triassic) of Fergana, Kyrgyzstan. Paleontological Journal 39:192-198.

Unwin, D. M., V. R. Alifanov, and M. J. Benton. 2000. Enigmatic small reptiles from the Middle-Late Triassic of Kirgizstan. In M. J. Benton, M. A. Shishkin, D. M. Unwin, E. N. Kurochkin (eds.), The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 177-186

#longisquama#longisquama insignis#diapsid#reptile#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#Prehistoric Life#paleontology

376 notes

·

View notes

Text

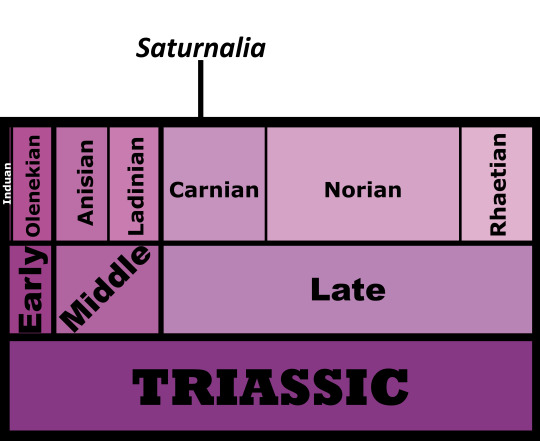

Saturnalia tupiniquim

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Named for the Roman festival of Saturn

First Described By: Langer et al., 1999

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Saturnaliidae

Status: Extinct

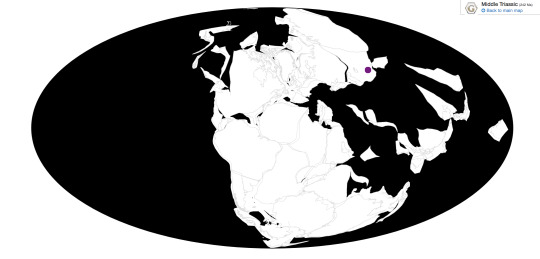

Time and Place: 233.23 million years ago, in the Carnian of the Late Triassic

Saturnalia is known from the Alemoa Member of the Santa Maria Formation - it is also possibly known from Zimbabwe, but this assignment is dubious

Physical Description: Saturnalia was probably a very early Prosauropod - aka, those dinosaurs that were more closely related to the large and famous Sauropods than any other kind of dinosaur (the official name for these dinosaurs being Sauropodomorphs). As an early Prosauropod, then, Saturnalia didn’t look very much different from other early dinosaurs - it was small, fluffy, squat, and bipedal. It was so much like other dinosaurs that it is often classified outside of Sauropodomorpha proper - and that continues to be a source of debate for these dinosaurs. In fact, according to some, it’s an early theropod!! More work is clearly needed, but regardless, Saturnalia was about 1.5 meters long and no more than a meter tall. It had a somewhat long neck - but no longer than other early dinosaurs, certainly not proper sauropodomorph length - and a small head. It had short arms, somewhat short legs, and a short tail as well. It was very slight, and had a skull like that of prosauropods, though its legs were more like those of theropods. Overall - a very average looking early dinosaur, and certainly very similar to the early Sauropodomorphs and the early Theropods of the time.

Diet: Saturnalia probably was an omnivore, feeding on both meat and plant food, at low levels of vegetation and mainly focusing on very small animals. Though it is also possible that it was a carnivore.

By Rex Chen

Behavior: Saturnalia, regardless of its affinity, would have been a very skittish animal - avoiding predators in its environment at all costs, and running about on its tip-toes in order to avoid danger. It was probably at least somewhat social, given multiple skeletons have been found of it, though of course we cannot be certain of such. Regardless, it would have spent a large portion of its day foraging on food, looking around for leaves to strip from branches and small animals to catch in its mouth. It would have probably taken care of its young, and may have formed family groups to do so. The long-ish neck of Saturnalia would have allowed it to reach deeper into the plantlife in order to grab food out of reach.

Ecosystem: The Santa Maria Formation is a hotspot of early dinosaur diversity, showcasing especially the initial explosion of Sauropodomorphs after dinosaurs first appeared. This was an extensive floodplain environment, filled with seed ferns and conifers, giving Saturnalia good amounts of cover to protect it from other creatures. This was important, because Saturnalia was far from alone in its home. Here, there were predatory dinosaurs, such as the Herrerasaurid Staurikosaurus and the prosauropod Buriolestes; mystery dinosaurs like Nhandumirim; other early prosauropods like Pampadromaeus and Bagualosaurus; the Lagerpetid Ixalerpeton; the weird Aphanosaur Spondylosoma; large Loricatan predators like Rauisuchus, Procerosuchus, Prestosuchus, Decuriasuchus, and Dagasuchus; large herbivorous Aetosaurs such as Aetobarbakinoides, Aetosauroides, and Polesinesuchus; rhynchosaurs like Hyperodapedon and Brasinorhynchus; mystery reptiles like Barberenasuchus; Proterochampsids like Cerritosaurus, Chanaresuchus, Proterochampsa, and Rhadinosuchus; Erpetosuchids like Pagosvnator; and plenty of synapsids such s Chiniquodon, Candelariodon, Exaeretodon, Protuberum, Santacruzodon, and Trucidocynodon. In short - an extremely diverse and flourishing environment, showcasing the true weirdness that was the Triassic period.

By Nobu Tamura, CC BY-SA 4.0

Other: Was Saturnalia a theropod or a prosauropod? The jury is still out. Its back half looks much like that of a theropod, but its head? Similar to prosauropods. The most recent analysis has it as a sauropodomorph - probably - but people still debate, and arguments continue to go on. It is often considered a part of a bigger group of dinosaurs including animals like Guaibasaurus, but some of these animals in recent studies have been found as prosauropods, and some as theropods, breaking up the group. So, the scientists continue to debate, and the exact nature of Saturnalia remains a mystery - but, for now, we can probably still call it a Sauropodomorph, along with Pampadromaeus.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Abdala, F., & A. M. Ribeiro (2003). "A new traversodontid cynodont from the Santa Maria Formation (Ladinian-Carnian) of southern Brazil, with a phylogenetic analysis of Gondwanan traversodontids". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 139 (4): 529–545.

Apaldetti, C., R. N. Martinez, O. A. Alcober and D. Pol. 2011. A new basal sauropodomorph (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from Quebrada del Barro Formation (Marayes-El Carrizal Basin), Northwestern Argentina. PLoS ONE 6(11):e26964:1-19

Aurélio, M., G. França; Jorge Ferigolo; Max C. Langer (2011). "Associated skeletons of a new middle Triassic "Rauisuchia" from Brazil". Naturwissenschaften. 98 (5): 389–395.

Barberena, MC (1978). "A huge tecodont skull from the Triassic of Brazil". Pesquisas Em Geociências. 9 (9): 62–75.

Bonaparte, J.F.; Ferigolo, J.; Ribeiro, A.M. (1999). "A new early Late Triassic saurischian dinosaur from Rio Grandedo Sul State, Brazil." Proceedings of the second Gondwanan Dinosaurs symposium". National Science Museum Monographs, Tokyo. 15: 89–109.

Bonaparte, J.F.; Brea, G.; Schultz, C.L.; Martinelli, A.G. (2007). "A new specimen of Guaibasaurus candelariensis (basal Saurischia) from the Late Triassic Caturrita Formation of southern Brazil". Historical Biology. 19 (1): 73–82.

Brea, G., J. F. Bonaparte, C. L. Schultz and A. G. Martinelli. 2005. A new specimen of Guaibasaurus candelariensis (basal Saurischia) from the Late Triassic Caturrita Formation of southern Brazil. In A. W. A.

Cabreira, Sergio F.; Cesar L. Schultz; Jonathas S. Bittencourt; Marina B. Soares; Daniel C. Fortier; Lúcio R. Silva; Max C. Langer (2011). "New stem-sauropodomorph (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Triassic of Brazil". Naturwissenschaften. 98 (12): 1035–1040.

Cabreira, S.F.; Kellner, A.W.A.; Dias-da-Silva, S.; da Silva, L.R.; Bronzati, M.; de Almeida Marsola, J.C.; Müller, R.T.; de Souza Bittencourt, J.; Batista, B.J.; Raugust, T.; Carrilho, R.; Brodt, A.; Langer, M.C. (2016). "A Unique Late Triassic Dinosauromorph Assemblage Reveals Dinosaur Ancestral Anatomy and Diet". Current Biology. 26: 3090–3095.

Colbert, EH (1970). "A saurischian dinosaur from the Triassic of Brazil". American Museum Novitates. 2045: 1–39.

Da-Rosa, Átila A. S. (2015-08-01). "Geological context of the dinosauriform-bearing outcrops from the Triassic of Southern Brazil". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 61: 108–119.

Da-Rosa, Átila Augusto Stock; Paes-Neto, Voltaire Dutra; Schultz, Cesar Leandro; Desojo, Julia Brenda; Brust, Ana Carolina Biacchi (2018-08-15). "Osteology of the first skull of Aetosauroides scagliai Casamiquela 1960 (Archosauria: Aetosauria) from the Upper Triassic of southern Brazil (Hyperodapedon Assemblage Zone) and its phylogenetic importance". PLOS ONE. 13 (8): e0201450.

De Oliveira, T. V., Cesar Leandro Schultz, Marina Bento Soares and Carlos Nunes Rodrigues (2011). "A new carnivorous cynodont (Synapsida, Therapsida) from the Brazilian Middle Triassic (Santa Maria Formation): Candelariodon barberenai gen. et sp. nov". Zootaxa. 3027: 19–28.

Delsate, D., and M. D. Ezcurra. 2014. The first Early Jurassic (late Hettangian) theropod dinosaur remains from the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Geological Belgica 17(2):175-181

Desojo, J. B., Martin D. Ezcurra and Edio E. Kischlat (2012). "A new aetosaur genus (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from the early Late Triassic of southern Brazil" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3166: 1–33. ISSN 1175-5334

Desojo, Julia B.; Trotteyn, M. Jimena; Hechenleitner, E. Martín; Taborda, Jeremías R. A.; Miguel Ezpeleta; von Baczko, M. Belén; Rocher, Sebastián; Martinelli, Agustín G.; Fiorelli, Lucas E. (October 2017). "Deep faunistic turnovers preceded the rise of dinosaurs in southwestern Pangaea". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (10): 1477–1483.

Dias-Da-Silva, Sérgio; Müller, Rodrigo T.; Garcia, Maurício S. (2019-07-04). "On the taxonomic status of Teyuwasu barberenai Kischlat, 1999 (Archosauria: Dinosauriformes), a challenging taxon from the Upper Triassic of southern Brazil". Zootaxa. 4629 (1): 146–150.

Ezcurra, M. D. 2010. A new early dinosaur (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic of Argentina: a reassessment of dinosaur origin and phylogeny. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 8:371-425

Ezcurra, MD (2012). "Comments on the Taxonomic Diversity andPaleobiogeography of the Earliest Known Dinosaur Assemblages (Late Carnian-Earliest Norian)". Historia Natural. 2.

Ezcurra, Martín D.; Desojo, Julia B.; Rauhut, Oliver W.M. (August 2015). "Redescription and Phylogenetic Relationships of the Proterochampsid Rhadinosuchus gracilis (Diapsida: Archosauriformes) from the Early Late Triassic of Southern Brazil". Ameghiniana. 52 (4): 391–417.

Flávio A. Pretto; Max C. Langer; Cesar L. Schultz (2018). "A new dinosaur (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic of Brazil provides insights on the evolution of sauropodomorph body plan". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. in press.

Galton, P. M., and P. Upchurch. 2004. Prosauropoda. In D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska (eds.), The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 232-258

Galton, P. M. 2007. Notes on the remains of archosaurian reptiles, mostly basal sauropodomorph dinosaurs, from the 1834 fissure fill (Rhaetian, Upper Triassic) at Clifton in Bristol, southwest England. Revue de Paléobiologie 26(2):505-591

Galton, P. M., A. M. Yates, and D. M. Kermack. 2007. Pantydraco n. gen. for Thecodontosaurus caducus Yates, 2003, a basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Upper Triassic or Lower Jurassic of South Wales, UK. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen 243(1):119-125

Griffin, C. T., and S. J. Nesbitt. 2016. The femoral ontogeny and long bone histology of the Middle Triassic (?late Anisian) dinosauriform Asilisaurus kongwe and implications for the growth of early dinosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(3):e1111224:1-22

Gower, D. J. (2000). "Rauisuchian archosaurs (Reptilia:Diapsida): An overview" (PDF). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 218 (3): 447–488

Harris, S. K., A. B. Heckert, S. G. Lucas and A. P. Hunt. 2002. The oldest North American prosauropod, from the Upper Triassic Tecovas Formation of the Chinle Group (Adamanian: latest Carnian), west Texas. In A. B. Heckert & S. G. Lucas (eds.), Upper Triassic Stratigraphy and Paleontology. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 21:249-252

Horn, B. L. D.; Melo, T. M.; Schultz, C. L.; Philipp, R. P.; Kloss, H. P.; Goldberg, K. (2014-11-01). "A new third-order sequence stratigraphic framework applied to the Triassic of the Paraná Basin, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, based on structural, stratigraphic and paleontological data". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 55: 123–132.

Irmis, R. B., and F. Knoll. 2008. New ornithischian dinosaur material from the Lower Jurassic Lufeng Formation of China. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen 247(1):117-128

Kellner, D. D. R. Henriques, and T. Rodrigues (eds.), II Congresso Latino-Americano de Paleontologia de Vertebrados, Boletim de Resumos. Museum Nacional/UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro 55-56

Kischlat, EE (1999). "A new dinosaurian "rescued" from the Brazilian Triassic: Teyuwasu barbarenai, new taxon". Paleontologia Em Destaque, Boletim Informativo da Sociedade Brasileira de Paleontologia. 14 (26): 58.

Lacerda, M. B.; Schultz, C. L.; Bertoni-Machado, C. (2015). "First 'Rauisuchian' archosaur (Pseudosuchia, Loricata) for the Middle Triassic Santacruzodon Assemblage Zone (Santa Maria Supersequence), Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil". PLoS ONE. 10 (2): e0118563. PMC 4340915 Freely accessible.

Langer, M. C., F. Abdala, M. Richter and M. J. Benton. 1999. A sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Upper Triassic (Carnian) of southern Brazil. Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences, Paris: Sciences de la terre et des planètes 329:511-517

Langer, Max C.; Schultz, Cesar L. (October 2000). "A New Species Of The Late Triassic Rhynchosaur Hyperodapedon From The Santa Maria Formation Of South Brazil". Palaeontology. 43 (4): 633–652.

Langer, M. C. 2003. The pelvic and hind limb anatomy of the stem-sauropodomorph Saturnalia tupiniquim (Late Triassic, Brazil). PaleoBios 23(2):1-40

Langer, M. C. 2004. Basal Saurischia. In D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmolska (eds.), The Dinosauria (second edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 25-46

Langer, M. C. 2005. Saturnalia tupiniquim and the origin of sauropodomorphs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25(3, suppl.):82A

Langer, M. C., and M. J. Benton. 2006. Early dinosaurs: a phylogenetic study. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 4(4):309-358

Langer, MC; Schultz, CL (2007). "The continental tetrapod-bearing Triassic of South Brazil". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 41: 201–218.

Langer, M. C., M. D. Ezcurra, J. S. Bittencourt and F. E. Novas. 2010. The origin and early evolution of dinosaurs. Biological Reviews 85:55-110

Langer, Max Cardoso; Brodt, André; Carrilho, Rodrigo; Raugust, Tiago; Batista, Brunna Jul’Armando; Bittencourt, Jonathas de Souza; Müller, Rodrigo Temp; Marsola, Júlio Cesar de Almeida; Bronzati, Mario (2016-11-21). "A Unique Late Triassic Dinosauromorph Assemblage Reveals Dinosaur Ancestral Anatomy and Diet". Current Biology. 26 (22): 3090–3095.

Langer, M.C.; Ramezani, J.; Da Rosa, Á.A.S. (2018). "U-Pb age constraints on dinosaur rise from south Brazil". Gondwana Research. X (18): 133–140.

Langer MC, McPhee BW, Marsola JCdA, Roberto-da-Silva L, Cabreira SF (2019) Anatomy of the dinosaur Pampadromaeus barberenai (Saurischia—Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation of southern Brazil. PLoS ONE 14(2): e0212543.

Lautenschlager, Stephan; Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (January 2015). "Osteology of Rauisuchus tiradentes from the Late Triassic (Carnian) Santa Maria Formation of Brazil, and its implications for rauisuchid anatomy and phylogeny: Osteology of Rauisuchus Tiradentes". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 173 (1): 55–91.

Leal, L. A., and S. A. K. Azevedo. 2003. A preliminary Prosauropoda phylogeny with comments on Brazilian basal Sauropodomorpha. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23(3, suppl.):71A

Liu, J. (2007). "The taxonomy of the traversodontid cynodonts Exaeretodon and Ischignathus" (PDF). Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 10 (2): 133–136.

Marsola, Júlio C. A.; Bittencourt, Jonathas S.; Butler, Richard J.; Da Rosa, Átila A. S.; Sayão, Juliana M.; Langer, Max C. (2018-09-03). "A new dinosaur with theropod affinities from the Late Triassic Santa Maria Formation, south Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 38 (5): e1531878.

Martínez, R. N., and O. A. Alcober. 2009. A basal sauropodomorph (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Triassic, Carnian) and the early evolution of Sauropodomorpha. PLoS ONE 4(2 (e4397)):1-12

Martinez, R. N.; Sereno, P. C.; Alcober, O. A.; Colombi, C. E.; Renne, P. R.; Montanez, I. P.; Currie, B. S. (2011-01-14). "A Basal Dinosaur from the Dawn of the Dinosaur Era in Southwestern Pangaea". Science. 331 (6014): 206–210.

Martínez, Ricardo N.; Apaldetti, Cecilia; Alcober, Oscar A.; Colombi, Carina E.; Sereno, Paul C.; Fernandez, Eliana; Malnis, Paula Santi; Correa, Gustavo A.; Abelin, Diego (November 2012). "Vertebrate succession in the Ischigualasto Formation". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (sup1): 10–30.

Mastrantonio, Bianca; von Baczko, María; Desojo, Julia; Schultz, Cesar (2019). "The skull anatomy and cranial endocast of Prestosuchus chiniquensis (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from Brazil". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 64.

Mattar, L.C.B. 1987. Descrição osteólogica do crânio e segunda vértebrata cervical de Barberenasuchus brasiliensis Mattar, 1987 (Reptilia, Thecodontia) do Mesotriássico do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Anais, Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 61: 319–333

Maurício S. Garcia; Rodrigo T. Müller; Átila A.S. Da-Rosa; Sérgio Dias-da-Silva (2019). "The oldest known co-occurrence of dinosaurs and their closest relatives: A new lagerpetid from a Carnian (Upper Triassic) bed of Brazil with implications for dinosauromorph biostratigraphy, early diversification and biogeography". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 91: 302–319.

McPhee, B. W., J. N. Choiniere, A. M. Yates and P. A. Viglietti. 2015. A second species of Eucnemesaurus Van Hoepen, 1920 (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha): new information on the diversity and evolution of the sauropodomorph fauna of South Africa's lower Elliot Formation (latest Triassic). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 35(5):e980504:1-24

Moser, M., U. B. Mathur, F. T. Fürsich, D. K. Pandey, and N. Mathur. 2006. Oldest camarasauromorph sauropod (Dinosauria) discovered in the Middle Jurassic (Bajocian) of the Khadir Island, Kachchh, western India. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 80(1):34-51

Müller, Rodrigo T; Langer, Max C; Bronzati, Mario; Pacheco, Cristian P; Cabreira, Sérgio F; Dias-Da-Silva, Sérgio (2018-05-15). "Early evolution of sauropodomorphs: anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of a remarkably well-preserved dinosaur from the Upper Triassic of southern Brazil". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Müller, Rodrigo T.; Garcia, Maurício S. (2019-03-08). "Rise of an empire: analysing the high diversity of the earliest sauropodomorph dinosaurs through distinct hypotheses". Historical Biology: 1–6.

Nesbitt, S. J., and M. D. Ezcurra. 2015. The early fossil record of dinosaurs in North America: A new neotheropod from the base of the Upper Triassic Dockum Group of Texas. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60(3):513-526

Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Butler, Richard J.; Ezcurra, Martín D.; Barrett, Paul M.; Stocker, Michelle R.; Angielczyk, Kenneth D.; Smith, Roger M. H.; Sidor, Christian A.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (April 2017). "The earliest bird-line archosaurs and the assembly of the dinosaur body plan". Nature. 544 (7651): 484–487.

Novas, F. E., M. D. Ezcurra, S. Chatterjee and T. S. Kutty. 2011. New dinosaur species from the Upper Triassic Upper Maleri and Lower Dharmaram formations of Central India. Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 101:333-349

Oliveira, T.V.; Soares, M.B.; Schultz, C.L. (2010). "Trucidocynodon riograndensis gen. nov. et sp. nov. (Eucynodontia), a new cynodont from the Brazilian Upper Triassic (Santa Maria Formation)". Zootaxa. 2382: 1–71.

Otero, A., and D. Pol. 2013. Postcranial anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Mussaurus patagonicus (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33(5):1138-1168

Philipp, Ruy P.; Schultz, Cesar L.; Kloss, Heiny P.; Horn, Bruno L.D.; Soares, Marina B.; Basei, Miguel A.S. (December 2018). "Middle Triassic SW Gondwana paleogeography and sedimentary dispersal revealed by integration of stratigraphy and U-Pb zircon analysis: The Santa Cruz Sequence, Paraná Basin, Brazil". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 88: 216–237.

Raath, M. A., P. M. Oesterlen, and J. W. Kitching. 1992. First record of Triassic Rhynchosauria (Reptilia: Diapsida) from the Lower Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe. Palaeontologia africana 29:1-10

Raugust, Tiago, Marcel Lacerda & Cesar Leandro Schultz (in press). "The first occurrence of Chanaresuchus bonapartei Romer 1971 (Archosauriformes, Proterochampsia) of the Middle Triassic of Brazil from the Santacruzodon Assemblage Zone, Santa Maria Formation (Paraná Basin)". In S.J. Nesbitt; J.B. Desojo & R.B. Irmis (eds.). Anatomy, phylogeny and palaeobiology of early archosaurs and their kin. The Geological Society of London.

Rauhut, O. W. M. 2003. The interrelationships and evolution of basal theropod dinosaurs. Special Papers in Palaeontology 69:1-213

Reichel, Míriam, Schultz , Cesar Leandro, & Soares , Marina Bento 2009 “A New Traversodontid Cynodont (Therapsida, Eucynodontia) from the Middle Triassic Santa Maria Formation of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil” Palaeontology 52(1):229-250

Roberto-da-Silva, L., Julia B. Desojo, Sérgio F. Cabreira, Alex S. S. Aires, Rodrigo T. Müller, Cristian P. Pacheco and Sérgio Dias-da-Silva (2014). "A new aetosaur from the Upper Triassic of the Santa Maria Formation, southern Brazil". Zootaxa. 3764 (3): 240–278.

Roberto-Da-Silva, Lúcio; Müller, Rodrigo Temp; França, Marco Aurélio Gallo de; Cabreira, Sérgio Furtado; Dias-Da-Silva, Sérgio (2018-12-24). "An impressive skeleton of the giant top predator Prestosuchus chiniquensis (Pseudosuchia: Loricata) from the Triassic of Southern Brazil, with phylogenetic remarks". Historical Biology: 1–20.

Romer, A. S. The Brazilian cynodont reptiles Belesodon and Chiniquodon. Breviora, 1969a, 332, 1–16.

Schultz, Cesar Leandro; Max Cardoso Langer & Felipe Chinaglia Montefeltro (2016). "A new rhynchosaur from south Brazil (Santa Maria Formation) and rhynchosaur diversity patterns across the Middle-Late Triassic boundary". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. in press. doi:10.1007/s12542-016-0307-7

Schultz, Cesar L.; de França, Marco A. G.; Lacerda, Marcel B. (2018-10-20). "A new erpetosuchid (Pseudosuchia, Archosauria) from the Middle–Late Triassic of Southern Brazil". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 184 (3): 804–824.

Smith, N. D., and D. Pol. 2007. Anatomy of a basal sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of Antarctica. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 52(4):657-674

Thulborn, T. 2006. On the tracks of the earliest dinosaurs: implications for the hypothesis of dinosaurian monophyly. Alcheringa 30:273-311

Upchurch, P., P. M. Barrett, and P. M. Galton. 2007. A phylogenetic analysis of basal sauropodomorph relationships: implications for the origin of sauropod dinosaurs. In P. M. Barrett, D. J. Batten (eds.), Evolution and Palaeobiology of Early Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs, Special Papers in Palaeontology 77:57-90

Weishampel, David B; et al (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Late Triassic, South America)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 527–528.

Yates, A. M. 2003. The species taxonomy of the sauropodomorph dinosaurs from the Löwenstein Formation (Norian, Late Triassic) of Germany. Palaeontology 46(2):317-337

Zerfass, Henrique; Lavina, Ernesto Luiz; Schultz, Cesar Leandro; Garcia, Antônio Jorge Vasconcellos; Faccini, Ubiratan Ferrucio; Chemale, Farid (2003-09-01). "Sequence stratigraphy of continental Triassic strata of Southernmost Brazil: a contribution to Southwestern Gondwana palaeogeography and palaeoclimate". Sedimentary Geology. 161 (1): 85–105.

#Saturnalia tupiniquim#Saturnalia#Prosauropod#Dinosaur#Sauropodomorph#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Triassic#south america#Mesozoic Monday#Omnivore

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mastodonsaurus pencil doodle

#mastodonsaurus#temnospondyl#plagiosaurus#triassic#ladinian#they probably had croc skin tho#big frog croc

86 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marasuchus lilloensis

Argentina, Ladinian Age of the Middle Triassic (Chañares Formation)

A small dinosauromorph archosaur (only about 40 cm long), Marasuchus lived in the shadows of larger animals and frequent volcanic activity. Relatives of Marasuchus, the dinosaurs themselves, would go on to dominate terrestrial ecosystems for millions of years.

Read more about Marasuchus, dinosauromorphs, and the Chañares Formation at Earth Archives.

#Marasuchus#lilloensis#Lagosuchus#triassic#Ladinian#Argentina#ornithodiran#Archosaur#dinosauromorphs#dinosauriformes#dinosauromorpha#Mesozoic#illustration#natural history#Nathan E. Rogers#Earth Archives#ornithodira#Chañares Formation#volcano#volcanic ash#dinosaur#Middle Triassic#science#paleontology#paleoart#evolution

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

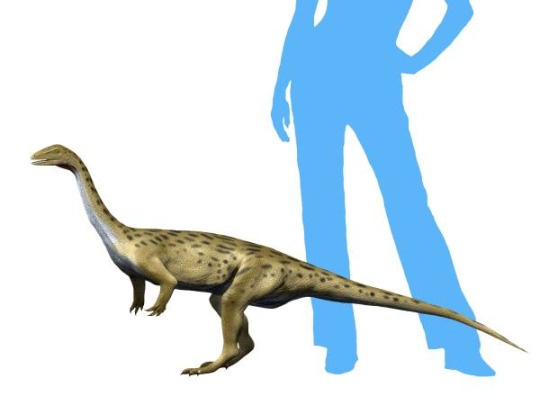

Nothosaurus

By Tas Dixon

Etymology: False Reptile

First Described By: Münster, 1834

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Reptiliomorpha, Amniota, Sauropsida, Eureptilia, Romeriida, Diapsida, Neodiapsida, Sauria, Archosauromorpha?, Archelosauria, Pantestudines, Sauropterygia, Eosauropterygia, Nothosauria, Nothosauridae, Nothosaurinae

Referred Species: N. mirabilis, N. cristatus, N. cymatosauroides, N. edingerae, N. giganteus, N. haasi, N. jagisteus, N. marchicus, N. mirabilis, N. tchernovi, N. yangjuanensis, N. zhangi

Time and Place: From 242 million years ago until 208 million years ago, from the Ladinian of the Middle Triassic through the earliest Rhaetian of the Late Triassic

Nothosaurus is known from all over Eurasia and North Africa, to the point that it’s pointless to list all the locations. Just assume that if it’s the Mid or Late Triassic of the Tethys Sea, Nothosaurus is there.

Physical Description: Nothosaurus is an iconic Triassic marine reptile - to the point that we had to include it, or else we would have violated some sort of rule of paleontology. Nothosaurus was about 4 meters long on average, but could reach up to 7 meters in length. It had a long, streamlined body, with a long neck and a long tail. Its head was narrow and filled with long and pointed teeth which interlocked together when the mouth closed, forming a tight trap. Its forelimbs were longer than its hind limbs, and all of its hands and feet had webbing between the long toes. In a lot of ways, it looked extremely similar to later marine reptiles to which it was closely related, like the Plesiosaurs and Pliosaurs, just with hands instead of proper flippers - however, current evidence indicates that the Plesiosaurs and Pliosaurs evolved from an ancestor of both groups, and Nothosaurus is just a Triassic offshoot. It had capabilities for diving in the water, though it also was still adapted for life on the shore.

Diet: Nothosaurus primarily ate fish and other marine animals, including other marine reptiles.

Behavior: Nothosaurus was semi-aquatic, spending a lot of its time both in the ocean and on land. On the beaches and shores it would rest and sleep, and then turn to the ocean for most of its everyday life. Diving for food would have been most of its daily activities, going after juvenile reptiles and large fish in the water and diving in order to reach it. It probably would have paddled with its webbed feet, and undulated its body to some extent to help propel forward. It may have been at least somewhat social, living in groups and colonizing the shores together before going for group dives for food. Interestingly enough, Nothosaurus was basically like a reptilian seal, coming up to shore to rest and sit with its relatives. Whether or not they would have given birth to live young is uncertain; while their close relatives, the Plesiosaurs, did; they retained enough land adaptations to allow them to lay eggs on the shore. More research as to their physiology is needed in order to determine that aspect of their life history. Trackways have been attributed to Nothosaurus, which may show that they rowed their paddles on the sea bed to shake up small animals trapped underneath; this would have allowed Nothosaurus to capture the invertebrates between its long teeth and hold onto them so they could not escape.

Ecosystem: Nothosaurus lived throughout the early Tethys sea, and was a common feature in many communities throughout this growing body of water during the Middle and Late Triassic. It would have stuck to the coasts for the most part, but still ventured out into deep and open water. As such, it’s rather difficult to list all the different animals it lived alongside - it’s found in Bulgaria, China, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Jordan, the Netherlands, Poland, Saudi Arabia, Spain, and Switzerland. So just, assume that a marine creature from the Tethys during this time lived with Nothosaurus rather than not.

Other: Nothosaurus has been treated as, unfortunately, a wastebasket taxon - it was discovered early enough in the history of paleontology as a science that many similar animals were just dumped into this name without any specific studies done. So, determining the factual relationships from this mess is still being worked out; in fact, it seems that this genus is paraphyletic, with many close relatives of Nothosaurus being more closely related to some species than to others. So that’s fun!

Species Differences: The varying species of Nothosaurus tend to differ based on where and when they lived, rather than any particularly notable differences. There are some differences in size and limb proportions as well, but in general the differing species of Nothosaurus would have had very similar ecological roles.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Albers, P. C. H., and O. Rieppel. 2003. A new species of the sauropterygian genus Nothosaurus from the Lower Muschelkalk of Winterswijk, The Netherlands. Journal of Paleontology 77(4):738-744.

Albers, P. C. H. 2005. A new specimen of Nothosaurus marchicus with features that relate the taxon to Nothosaurus winterswijkensis. Vertebrate Palaeontology 3 (1): 1- 7.

Brotzen, F. 1956. Stratigraphical studies on the Triassic vertebrate fossils from Wadi Raman, Israel. Arkiv foer Mineralogi och Geologi 2(9):191-217.

Chrzastek, A. 2008. Vertebrate remains from the Lower Muschelkalk of Raciborowice Górne (North-Sudetic Basin, SW Poland). Geological Quarterly 52:225-238.

Diedrich, C. 2009. The vertebrates of the Anisian/Ladinian boundary (Middle Triassic) from Bissendorf (NW Germany) and their contribution to the anatomy, palaeoecology, and palaeobiogeography of the Germanic Basin reptiles. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 273 (1): 1 - 16.

d'Orbigny, A. 1849. Cours Élémentaire de Paléontologie et de Géologie Stratigraphiques [Elementary Course in Paleontology and Stratigraphic Geology] 1:1-299.

Haas, G 1980. Ein Nothosaurier-Schädel aus dem Muschelkalk des Wadi Ramon (Negev, Israel). Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien 83:119-125.

Haines, Tim, and Paul Chambers. The Complete Guide to Prehistoric Life. Pg. 64. Canada: Firefly Books Ltd., 2006

Hinz, J. K., A. T. Matzke, and H.-U. Pfretzschner. 2019. A new nothosaur (Sauropterygia) from the Ladinian of Vellberg-Eschenau, southern Germany. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Jiang, W.; Maisch, M. W.; Hao, W.; Sun, Y.; Sun, Z. 2006. Nothosaurus yangjuanensis n. sp. (Reptilia, Sauropterygia, Nothosauridae) from the middle Anisian (Middle Triassic) of Guizhou, southwestern China. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte. 5: 257–276.

Jiang, D.-Y., L. Schmitz, R. Motani, W.-C. Hao, and Y.-L. Sun. 2007. The mixosaurid ichthyosaur Phalarodon cf. P. fraasi from the Middle Triassic of Guizhou Province, China. Journal of Paleontology 81(3):602-605.

Klein, N. and P. C. H. Albers. 2009. A new species of the sauropsid reptile Nothosaurus from the Lower Muschelkalk of the western Germanic Basin, Winterswijk, The Netherlands. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 54(4):589-598.

Lin, W.-B.; Jiang, D.-Y.; Rieppel, O.; Motani, R.; Ji, C.; Tintori, A.; Sun, Z.-Y.; Zhou, Min 2017. A new specimen of Lariosaurus xingyiensis (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) Zhuganpo Member, Falang Formation, Guizhou, China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37 (2): e1278703.

Liu, J. 2014. A gigantic nothosaur (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Middle Triassic of SW China and its implications for the Triassic biotic recovery. Scientific Reports 4: 7142.

Lu, H., D.-Y. Jiang, R. Motani, P.-G. Ni, Z.-Y. Sun, A. Tintori, S.-Z. Xiao, M. Zhou, C. Ji and W.-F. Fu. 2018. Middle Triassic Xingyi Fauna: Showing turnover of marine reptiles from coastal to oceanic environments. Palaeoworld 27(1):107-116.

Münster, G. G. 1834. Preliminary news about some new reptiles in the shell limestone of Baiern. New Yearbook for Mineralogy, Geognosy, Geology and Petriology 1834 : 521-527.

Palmer, D. ed. 1999. The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 72.

Rieppel, O., and J.-M. Mazin. 1997. Speciation along rifting continental margins: a new nothosaur from the Negev (Israel). Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences Série IIA, Sciences de la Terre et des planètes 326:991-997.

Rieppel, O. 2001. A new species of Nothosaurus (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Upper Muschelkalk (Lower Ladinian) of southwestern Germany. Palaeontographica Abteilung A 263:137-161.

Sepkoski, J. J. 2002. A compendium of fossil marine animal genera. Bulletins of American Paleontology 363:1-560.

#nothosaurus#nothosaur#sauropterygian#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

308 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mastodonsaurus

By Tas Dixon

Etymology: Nipple-toothed reptile

First Described By: Jaeger, 1828

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Temnospondyli, Limnarchia, Stereospondylomorpha, Stereospondyli, Capitosauria, Mastodonsauridae

Referred Species: M. jaegeri, M. cappalensis, M. giganteus, M. torvus

Status: Extinct

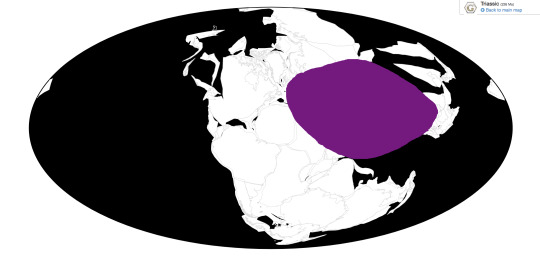

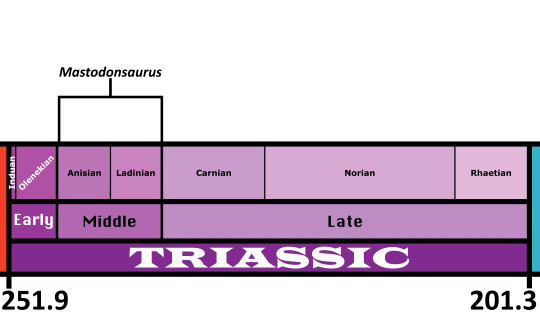

Time and Place: 247 to 237 million years ago, from the Anisian to the Ladinian of the Middle Triassic

Mastodonsaurus is known mostly from Germany and Russia.

Physical Description: Mastodonsaurus was a very large temnospondyl, growing up to 6 meters (20 feet) long. It’s one of the largest “amphibians” (if you accept the term to mean non-amniote tetrapods) known from actually decent remains. This thing’s downright badass. Its head was large, wide and flattened, with the eyes positioned at the top about ⅔ of the way back. The head was roughly-textured, being covered in rugosities that suggest a tight covering of skin. The upper and lower jaws were filled with spikelike teeth, of which there were two rows in the upper jaw. Each tooth has a complex labyrinthine structure in cross section, leading to the colloquialism “labyrinthodont” for big temnospondyls like this. Two teeth in the front of the lower jaw had developed into large tusks, which were so large that there are holes on the top of the jaw for the tusks to go through when the mouth was closed. I repeat: IT HAD HOLES IN ITS SKULL BECAUSE ITS TEETH WERE SO BIG. That’s downright gnarly. The upper jaw also had enlarged fanglike teeth on the palate, but they weren’t that huge. Postcranially Mastodonsaurus was similar to other temnospondyls, with short, sprawling limbs and a powerful tail.

Diet: Mastodonsaurus’s diet likely consisted of any living or until-recently-living animal that happened to be in the water (including if it was pulled in).

Behavior: Mastodonsaurus likely lived similarly to modern crocodiles, lurking in waterways waiting for prey. In the water it may have done short chases after prey such as fish and other temnospondyls, but it probably ambushed tetrapod prey. Its limbs were quite small relative to the rest of its body, indicating that it likely spent most of, or even almost all of, its time in the water. It may have been able to attack animals on the banks of waterways, but that’s probably the most it did on a regular basis: grabbing prey on the shore of the water and dragging it back in to be eaten.

Ecosystem: Mastodonsaurus lived in environments with lots of freshwater. Some Mastodonsaurus-preserving environments also bear marine fossils, suggesting it may have also lived in coastal deltas or estuaries. M. jaegeri, M. cappalensis and M. giganteus lived in what is now west-central Europe. This area was evidently very wet, as evidenced by the variety of aquatic animals discovered there. These include fellow temnospondyl Gerrothorax, the nothosaurs Nothosaurus and Simosaurus, the early turtle Pappochelys, Tanystropheus, sharks, mollusks, and our old friends Ceratodus and Saurichthys. Some terrestrial animals also lived in this area, like cynodonts and the pseudosuchians Batrachotomus and Ctenosauriscus. Meanwhile, M. torvus lived in what is now Russia, alongside fellow temnospondyls Plagioscutum and Plagiorotus, the prolacertid Malutinisuchus, the rauisuchid Energosuchus, the erythrosuchid Chalishevia, and Elephantosaurus, a dicynodont with a horrible name.

Other: I try not to be an awesomebro, but this thing was pretty cool.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources under the cut

Moser, M., Schoch, R. 2007. Revision of the type material and nomenclature of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (Jaeger) (Temnospondyli) from the Middle Triassic of Germany. Palaeontology 50(5): 1245-1266.

Owen, R. 1842. On the Teeth of Species of the Genus Labyrinthodon (Mastodonsaurus of Jaeger), common to the German Keuper formation and the Lower Sandstone of Warwick and Leamington. Transactions of the Geological Society of London 2(5). 503-513.

Schoch, R.R. 1999. Comparative osteology of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (JAEGER, 1828) from the Middle Triassic (Lettenkeuper: Longobardian) of Germany (Baden-Wurttemberg, Bayern, Thuringen). Stuttgarter Beitrage zur Naturkunde B 278: 1-175.

#mastodonsaurus#temnospondyl#labyrinthodont#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gerrothorax pulcherrimus

By @stolpergeist

Etymology: Wicker chest

First Described By: Nilsson, 1934

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Temnospondyli, Limnarchia, Stereospondylomorpha, Stereospondyli, Trematosauria, Plagiosauroidea, Plagiosauridae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 242 to 201 million years ago, from the Ladinian of the Middle Triassic to the Rhaetian of the Late Triassic

Gerrothorax is known from Germany, Greenland, and Sweden.

Physical Description: Gerrothorax is a very flat critter. At about a meter long, its body was wider than it was tall. So was its head. The eyes were large and positioned on the top of the head, as was a smaller parietal eye that wouldn’t have been as visible. Most animals open their mouths by angling the lower jaw downward. Gerrothorax, however, kept its lower jaw steady on the ground, and moved its entire upper skull upwards. It could have moved its skull up approximately 50 degrees from the horizontal. An action similar to the opening of a toilet seat lid. As this happened, the lower jaw would have been pushed outwards The teeth were small and peglike, running around the rim of the outside of the jaws. It retained its larval gills into adulthood, but they wouldn’t have been large and frilly like those of the living axolotl

Diet: Gerrothorax likely ate fish and other smaller aquatic organisms. It probably sat and waited for food to come by.

Behavior: All the weird features I mentioned above lead to the relatively obvious conclusion that Gerrothorax lived at the bottom of shallow freshwater bodies as an ambush predator. Its flat frame would keep it hidden. It may have been cryptically colored, or possibly buried itself beneath sand or mud. When prey came by, it would have raised its head with the jaws closed and rapidly opened the mouth. This would create a vacuum effect, which would suck the prey into the mouth to be eaten. A similar feeding strategy is used by certain fish and salamanders around today. It was different from those, however, in that all the skull bones were tightly fused, so they couldn’t have formed a “trap” around the prey.

By @stolpergeist

Ecosystem: Gerrothorax lived in shallow freshwater systems in Triassic Europe. It would have shared the waters with sharks, ray-finned and lobe-finned fish, phytosaurs, aquatic reptiles such as Nothosaurus, and other temnospondyls such as Cyclotosaurus and Metoposaurus. Around these rivers and lakes lived dinosaurs like Efraasia, Procompsognathus and Halticosaurus, pterosaurs like Arcticodactylus, and pseudosuchians such as Batrachotomus, Aetosaurus, and Saltoposuchus.

Other: Gerrothorax is known from a span of time lasting over 35 million years. In this time it barely changed morphologically - the latest Gerrothorax were basically identical to the earliest. This was probably because the niche it occupied offered little room for morphological change. Or maybe it simply wasn’t necessary. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources under the Cut

Jenkins, F.A., Shubin, N.H., Gatesy, S.M., Warren, A. 2008. Gerrothorax pulcherrimus from the Upper Triassic Fleming Fjord Formation of East Greenland and a reassessment of head lifting in temnospondyl feeding. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (4): 935-950.

Nilsson, T. 1946. A new find of Gerrothorax rhaeticus Nillson, a plagiosaurid from the Rhaetic of Scania. Lunds Universitates Arsskrift 42 (10).

Schoch, R.R., Witzmann, F. 2011. Cranial morphology of the plagiosaurid Gerrothorax pulcherrimus as an extreme example of evolutionary statis. Lethaia.

Witzmann, F., Schoch, R.R. 2013. Reconstruction of cranial and hyobranchial muscles in the Triassic temnospondyl Gerrothorax provides evidence for akinetic suction feeding. Journal of Morphology 274 (5): 525-542.

#gerrothorax#gerrothorax pulcherrimus#temnospondyl#amphibian#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#paleontology#prehistoric life#palaeoblr

378 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foreyia maxkuhni

Etymology: Forey’s Fish

First Described By: Cavin et al., 2017

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota, Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Actinistia, Coelacanthiformes, Latimerioidei, Latimeriidae,

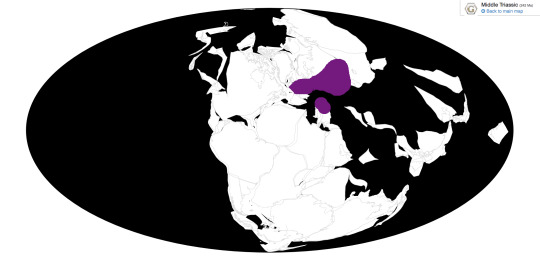

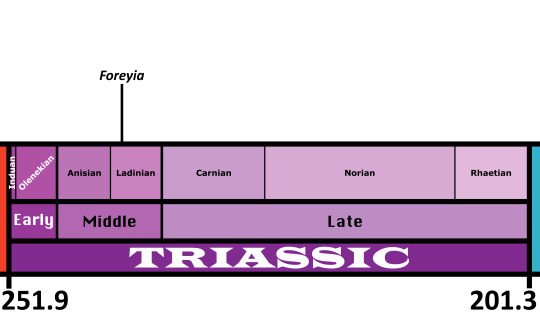

Time and Place: Foreyia lived about 240.91 million years ago, in the Ladinian of the Middle Triassic

Foreyia is known from the Prosanto Formation of Switzerland

Physical Description: Foreyia was a Coelacanth, a sort of Lobe-Finned Fish once thought to be a unique feature of prehistoric ecologies, and now known to survive in two different species today. This is wild, of course, but Coelacanths were weird in many different ways throughout their prehistoric tenure. Foreyia looked only a little similar to its cousins - it had a huge head compared to other Coelacanths, as well as a beak - something that you really only see in ray-finned fish and tetrapods - an underbite, and a horn on its head. That said, its body looks similar enough to other coelacanths, with dorsal fins and a wide tail fin, and large forelimb fins. However, the large size of its head makes it look like a Coelacanth that had been squished extensively, with the body looking quite short and squished compared to its close relative Ticinepomis. We aren’t sure as to what colors it may have been, but since it lived in a tropical region and may have had a similar niche as a Parrotfish, it is reasonable to suppose it may have been colorful. It was also very small, only around 20 centimeters long.

Diet: Given the beak, it’s likely that Foreyia ate hard food, potentially even similarly to living parrotfish - by chipping off algae covered rocks and reef builders, or potentially eating small shelled animals in the tidal pools.