#paleonotlogy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Fossil Crocs of 2024

Another year another list of new fossil crocodilians that greatly expand our knowledge of Pseudosuchia across deep time. Happy to say that this is my third time doing this now, so I'm not going to bog you down with the details and get right into it.

Benggwigwishingasuchus

Our first entry, sorted by geological age of course, is Benggwigwishingasuchus eremicarminis (desert song fishing crocodile) from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of Nevada. It was a member of the clade Poposauroidea, which some of you might recognize as also containing such bizarre early croc cousins like Arizonasaurus and Effigia. Also notable about Benggwigwishingasuchus is that it was found in the Fossil Hill Member of the Favret Formation. Why is that notable? Well the Fossil Hill Member preserves an environment deposited 10 km off the Triassic coastline and also yielded fossils of animals like Cymbospondylus, the giant ichthyosaur. Despite this however, Benggwigwishingasuchus shows no obvious signs of having been a swimmer or diver. Instead, its been hypothesized that it was simply foraging around the coast and might have been washed out to sea.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe (@knuppitalism-with-ue) and Jorge A. Gonzalez

Parvosuchus

Fast forward some 5 million years to the Ladinian - Carnian of Brazil, specifically the Santa Maria Formation. Here you'll find the one new genus on the list I did not write the wikipedia page for: Parvosuchus aurelioi (Aurélio's Small Crocodile). With only a meter in length, Parvosuchus is amongst the smallest pseudosuchians of the year and a member of the aptly named Gracilisuchidae. Santa Maria was actually home to multiple pseudosuchians, including the mighty Prestosuchus (and its possible juvenile form Decuriasuchus), the small erpetosuchid Archeopelta and larger Pagosvenator and one more...

Artwork by Matheus Fernandes and Joschua Knüppe

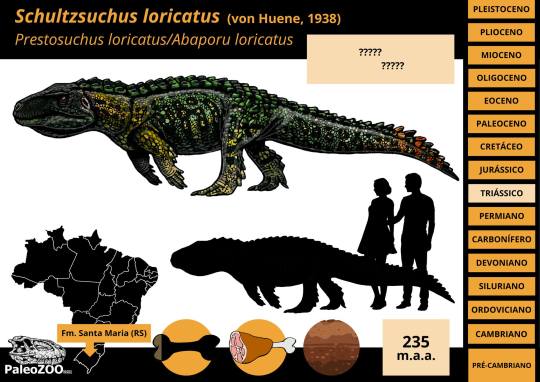

Schultzsuchus

Yup, Santa Maria has been eating good this year. Before the description of Parvosuchus, scientists coined the name Schultzsuchus loricatus (Schultz's Crocodile). Now this one's not entirely new and has long been known under the name Prestosuchus loricatus (by which I mean since 1938). What's interesting is that this new redescription suggests that rather than being a Loricatan, Schultzsuchus was actually an early member of Poposauroidea like Benggwigwishingasuchus. Even if it was no longer thought to be close to Prestosuchus, it was liekly still a formidable predator and among the larger pseudosuchians of the formation.

Artwork by Felipe Alves Elias

Garzapelta

Our last Triassic pseudosuchian and our only aetosaur of the year came to us in the form of Garzapelta muelleri (Mueller's Garza County Shield). It comes from the Late Triassic (Norian) Cooper Canyon Formation of, you guessed it, Garza County, Texas. As an aetosaur, the osteoderms are already regarded as diagnostic, tho unlike some other recent examples there is a little more material to go off from. It's still primarily osteoderms, but at least a good amount and even some ribs.

Artwork by Márcio L. Castro

Ophiussasuchus

Our only Jurassic newcommer is Ophiussasuchus paimogonectes (Paimogo Beach Swimmer Portuguese Crocodile), but arguably you couldn't find a better posterchild for Jurassic crocodyliforms. This new lad is a goniopholidid from the Kimmeridgian to Tithonian Lourinhã Formation, yup, Europe's Morrison. It's anatomy is perhaps not the most exciting, like other goniopholidids it had a flattened, very crocodilian-esque snout and was likely semi-aquatic like its relatives.

Artwork by @manusuchus and Joschua Knüppe

Enalioetes

Another quintessential group of Jurassic crocodyliforms are the metriorhynchoids, however, 2024's only new addition to this clade was actually Cretaceous, specifically from the earliest Cretaceous (Valanginian) of Germany. Like Schultzsuchus, Enalioetes schroederi (Schroeder's Sea Dweller) is new in name only, as fossil material has been found at the latest in 1918 and given the name Enaliosuchus "schroederi" in 1936. This kickstarted a whole series of taxonomic back and forth until the recent redescriptoin finally just gave it a new name and settled things (for now). Looking back I realize that I really need to take the time and fix up the Wikipedia page. Tho I've written its current status, I was kinda limited by being on vacation and never dived into the description section.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe and Jackosaurus

Varanosuchus

Another Early Cretaceous crocodyliform is Varanosuchus sakonnakhonensis (Monitor Lizard Crocodile from the Sakon Nakhon Province), described from Thailand's Sao Khua Formation. It lived around the same time as Enalioetes, but otherwise couldn't have been more different. Where Enalioetes was fully marine, Varanosuchus was more a land dweller as evidenced by the deep skull and long, slender legs. At the same time, some other features, like its more robust limbs compared to its kin, might suggest that Varanosuchus could have still spent some time in the water like some modern lizards. Tho one might be reminded of Parvosuchus from earlier, Varanosuchus is a much more recent example of small terrestrial croc-relatives, the atoposaurids, which are much closer to todays crocodiles and alligators.

Artwork once again by Manusuchus

Araripesuchus manzanensis

Yet another example of a small, gracile land "crocodile" comes to us in the form of Araripesuchus manzanensis (Araripe Basin Crocodile from the El Manzano Farm). And once again, it belonged to a completely different group, this time the notosuchian family Uruguaysuchidae. Now Araripesuchus is well known as a genus, in part due to the work of Paul Sereno and Hans Larsson (who popularized the names "dog croc" and "rat croc" for two species). Tangent aside, A. manzanensis is known from the upper layers of Argentina's Candeleros Formation, corresponding to the Cenomanian (earliest Late Cretaceous). The same locality also yielded A. buitreraensis, from which A. manzanensis can be distinguished on account of its blunt molariform teeth in the back of its jaw. This dentition, which corresponds to a durophageous diet of hardshelled prey, could explain how it coexisted with the related A. buitrensis at the same locality, allowing the two to occupy different niches. There is a neat little animation done for this animal you can watch here.

Artwork by Gabriel Diaz Yantén

Caipirasuchus catanduvensis

We're staying in South America but moving to Brazil's Adamantina Formation for our next entry: Caipirasuchus catanduvensis (Caipiras Crocodile from Catanduva). This one is a little more recent, tho the age of the Adamantina Formation is a bit of a mess far as I can tell, ranging anywhere from the Turonian to the Maastrichtian. One could also argue that C. catanduvensis is part of the "lanky small croc club" that Parvosuchus, Varanosuchus and A. manzanensis belong to, but I feel that the very short snout helps it stand out from that bunch more easily. Anyhow, Caipirasuchus catanduvensis is a member of Sphagesauridae, related to Armadillosuchus, and herbivorous. What's really interesting tho is that the internal anatomy suggests the presence of resonance chambers not unlike that of hadrosaurs, possibly suggesting that these animals were quite vocal. This could also explain why baurusuchids appear to have had very keen hearing.

Artwork by Joschua Knüppe and Guilherme Gehr

Epoidesuchus

We're staying in the Adamantina Formation for our last Mesozoic croc of the year, Epoidesuchus tavaresae (Tavares' Enchanted Crocodile). Tho also a Notosuchian like Araripesuchus and Caipirasuchus, this one belongs to the family Itasuchidae (or the subfamily Pepesuchinae depending on who you ask), which stand out as being rare examples of semi-aquatic members of this otherwise largely terrestrial group. Epoidesuchus was fairly large for its kin and had long, slender jaws. Like I said, Epoidesuchus and its relatives were likely more semi-aquatic than other notosuchians, something that might explain the relative lack of semi-aquatic neosuchians across Gondwana. They aren't absent mind you, but noticably rarer than they are in the northern hemisphere.

Artwork by Guilherme Gehr

And thus we move into the Cenozoic and towards the end our or little list. From here on out, say goodbye to Notosuchians or other weird crocodylomorphs and get ready for Crocodilia far as the eye can see.

Ahdeskatanka

The first Cenozoic croc we got is Ahdeskatanka russlanddeutsche (Russian-German Alligator), which despite its name comes from North Dakota, specifically the Early Eocene Golden Valley Formation. Ahdeskatanka is similar to many early alligatorines like Allognathosuchus in being small with rounded, globular teeth that suggest that it fed on hardshelled prey. This would have definitely helped avoid competition in the Golden Valley Formation, which also housed a second, similar form not yet named, a large generalist with a V-shaped snout similar to Borealosuchus and the generalized early caiman Chrysochampsa, also large but with a U-shaped snout.

Artwork by meeeeeeee

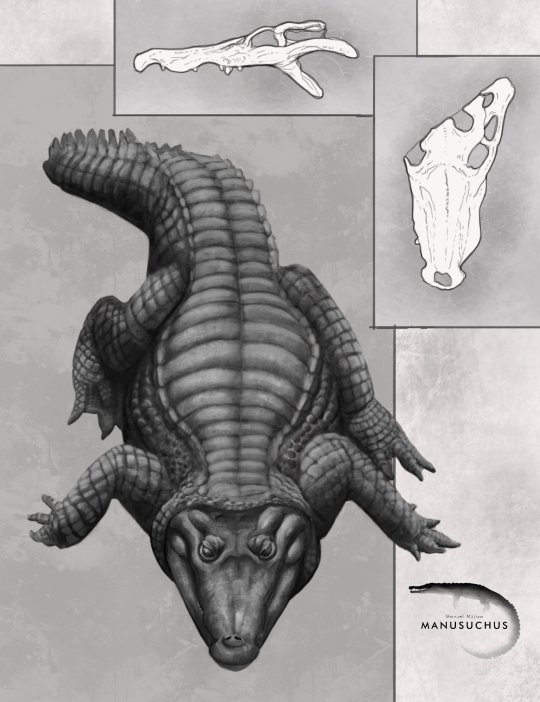

Asiatosuchus oenotriensis

We had an alligatoroid, so now its time for a crocodyloid. Asiatosuchus has been recognized from the Late Eocene Duero Basin of Spain for a while now, but now we have a name: Asiatosuchus oenotriensis (Asian Crocodile Belonging To The Land Of Wine). Asiatosuchus is a complex genus, most often not really forming a monophyletic clade and likely representing several distinct or at least successive taxa that form the "Asiatosuchus-like complex". Within this complex, A. oenotriensis is thought to have been close-ish to Germany's Asiatosuchus germanicus.

Artwork by Manusuchus

Sutekhsuchus

Rounding out the trio of major crocodilian clades is Sutekhsuchus dowsoni (Set's Crocodile/God of Deception Crocodile), representing our only gavialoid of the year. Originally described as Tomistoma dowsoni in 1920 based on fossil remains from the Miocene of Egypt, Sutekhsuchus has been at times regarded as distinct and at other times lumped into Tomistoma lusitanica. It was one of several early gavialoids to inhabit the coast of the Tethys during the Miocene and appears to have been most closely related to the genus Eogavialis, clading together just outside of the American and Asian gharials. A fun little personal anecdote, I prematurely learned about this one due to a friend highlighting the name in a study on Eogavialis. Never having heard of "Sutekhsuchus" I took to google scholar, where I found a single result: a reference to the then unpublished description, which naturally I ended up eagerly awaiting.

Artwork by Manusuchus and Joschua Knüppe

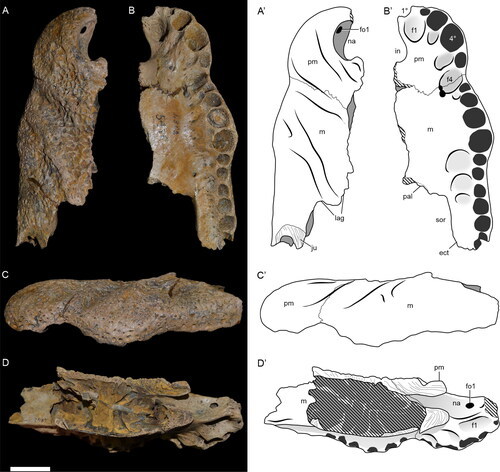

Paranacaiman

Two more and we're done. First, completely arbitrarily, Paranacaiman bravardi (Bravard's Caiman from Parana) from the Miocene Ituzaingo Formation of Argentina. Material of this genus has originally been referred to Caiman lutescens, described in 1912 but now considered a nomen dubium. Paranacaiman is known from limited material only, just the skull table, but that would indicate a "huge" animal. My personal scaling recovered a size of almost 5 meters in length, similar to large black caimans today.

Once again, credit to me

Paranasuchus

Last but not least, Paranasuchus gasparinae (Gasparini's Crocodile from Parana). Coming from the same deposits as Paranacaiman, this one too has been known as a species of Caiman for some time before being assigned its own genus, though it at least got to retain its old species name. Alas, I have not scaled it myself, tho its material is at least more extensive than that of Paranacaiman, including even parts of the snout. A little nitpick because I don't have much to say, but I personally think the name was ill conceived. On its own both Paranacaiman and Paranasuchus are fine names don't get me wrong, but together, coined by the same authors in the same study no less, they strike me as needlessly confusing to non experts. Both are caimans, both are from Parana, so the distinction between "Parana Caiman" and "Parana Crocodile" is entirely arbitrary and doesn't really distinguish them. Not helped by the fact that they are even closely related in the original description. Other than that tho another good addition to our understanding of fossil crocs.

No artwork on this one, but fossil material from Bona et al. 2024

And that wraps up 2024. I hope This post, or my posts throughout the year or even my work on Wikipedia has helped to make these fascinating animals just a little bit more approachable and a massive thanks to all the artists who took their time to create fantastic pieces featuring these incredible animals. Special shout outs to Manusuchus, who diligently illustrated a lot of the featured animals and Joschua Knüppe, who had to listen to me suggest Ahdeskatanka every Sunday for about two months straight now.

Fossil Crocs of 2023

Fossil Crocs of 2022

#paranasuchus#paranacaiman#ahdeskatanka#sutekhsuchus#ophiussasuchus#epoidesuchus#caipirasuchus#araripesuchus#enalioetes#parvosuchus#benggwigwishingasuchus#schultzsuchus#garzapelta#varanosuchus#paleontology#prehistory#palaeoblr#long post#fossil crocs of 2024#paleo#paleonotlogy#crocodilia#crocodylomorpha#pseudosuchia#fossils#2024

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

@isindismay Okay, now I'm really going to think about what you actually look like!

.

.

.

Well, here's some of mine:

reblog and put in the tags your favorite compliment you’ve ever received

#1 “You're beautifully prehistoric!”#1.2 (by my boyfriend who is a paleonotlogy enthusiast ...#1.3 ... and he's also been platonically in love with Raquel Welch in One Million Years B.C. since he was a kid - for a bit of context ...#1.4 ... but no I don't look like her)#2 “Are you going for a PhD? That's actually the main thing we're here to talk about today.”#2.2 (by opponent of my history diploma thesis about Czechoslovakian member of Women's Auxiliary Air Force)#3 Any praise regarding the believability of the characters in my fanfics or original stories.

668 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Bats: Ancient Origins of a Halloween Icon

Specimen Carnegie Museum (CM) 62641, the holotypic, or name-bearing, right dentary (lower jaw bone) of the tiny fossil bat Honrovits tsuwape in lingual (= internal) view, still partially encased in ~50-million-year-old rock of the Wind River Formation of west-central Wyoming. Note the length of the scale bar, only 1 cm (less than half an inch)!

Did you know that bats have been around for at least 55 million years? In 1992, several fossils in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History collection, including the lower jaw bone shown above, were described as representing a new genus and species of ancient bat, Honrovits tsuwape—Shoshone for “bat” and “ghost,” respectively—by a team that included two former curators in the museum’s Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, Christopher Beard and Leonard Krishtalka, both now of the University of Kansas. Honrovits dates to the early part of the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era (the ‘Age of Mammals’), about 50 million years ago, and is a member of a now-extinct bat group called the Onychonycteridae.

Replica of a beautifully preserved fossil skeleton of Onychonycteris finneyi, a close relative of Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s own Eocene-aged bat Honrovits tsuwape, on display at Fossil Butte National Monument in Wyoming. Photo by Matthew Dillon.

Interestingly, Honrovits shares dental characteristics with a mammal group known as insectivores, which includes today’s hedgehogs, shrews, and moles, and in that sense, it differs from the condition in most other bats. However, bat teeth possess distinctive diagnostic features, so although Honrovits is known only from a few tooth-bearing jaw bones and a skull fragment, there’s no doubt that the diminutive beast was indeed an early bat. The fragmentary nature of its fossils means that we don’t know for sure what Honrovits looked like in life, though it’s a good bet that it bore a close resemblance to other onychonycterid bats, such as Onychonycteris finneyi, which is known from exquisitely preserved skeletons (such as the one shown above).

Flesh reconstruction of the ~50-million-year-old bat Onychonycteris finneyi. There’s an excellent chance that Honrovits tsuwape would have looked like this. Art by Nobu Tamura.

The incompleteness of the Honrovits fossils is, unfortunately, the norm rather than the exception when it comes to prehistoric bats. Fossils of these creatures are exceedingly rare because most bats have very small, light skeletons and achieve their greatest diversity and abundance in areas that have low potential for fossil preservation, such as tropical forests. Occasionally, complete skeletons such as those of Onychonycteris are found, but not nearly as often as fragments.

So, this autumn, if you happen to catch a glimpse of a bat silhouetted against the evening sky, acrobatically wheeling and plunging in pursuit of flying insects, pause and reflect on the history of these extraordinary flying mammals whose ancestry dates nearly to the time of the dinosaurs.

Linsly Church is a Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

#Carnegie Museum of Natural History#Bat fossil#Fossils#Paleonotlogy#Halloween#Honrovits tsuwape#Onychontcteris finneyi

133 notes

·

View notes

Note

See now I wanna make a poke-paleonotlogy blog, cause this- a student paleontologist

*gasp* DOITDOITDOITDOITDOIT!

More scientists! More blogs! More content for me to read! (you will tell me when you make it, right? I can't get enough of these blogs!)

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

That thigh gap...

17 notes

·

View notes