#Kubaba

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It is characteristic of leadership in this early period that there is a merging of divine and secular power personified by the ruler. The king list, a document written down in about 1800 B.C., traces the successive dynasties for the major cities in Mesopotamia back into the third millennium. While the chronologies are somewhat inflated, archaeologists have verified some of the data with other evidence. The earliest Sumerian dynasties were based in the cities of Kish, Warka, and Ur. According to the king list, the founder of the dynasty of Kish was Queen Ku-Baba, who is listed as having reigned a hundred years. She is identified as having formerly been a tavern-keeper, an occupation which puts her at the margins of society. She was later identified with the goddess Kubaba, who was worshiped in Northern Mesopotamia. She is the only woman listed in the king list as reigning in her own right, but the merging of her historic personality with that of a divinity is not unlike that of the mythical demigod Gilgamesh, ruler of Warka, who supposedly reigned in the Early Dynastic period, but for whose historical existence there is no hard evidence, and whose exploits are immortalized in the epic of Gilgamesh.

-Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

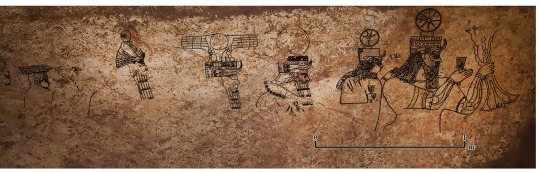

Atarata (Atargatis/Astarte) & (Baal) Hadad

Shamash (Sun God) & Syn (Moon God)

Unknown Deities. Goddess Second-from-left may be Kubaba?

Aramaic names of deities:

a) HDD “Hadad”

b) ’TRT “’Attar‘ata”

c) Ṣ(YN)? “Sîn”

d) MK[N]-’BW[’] R[’]Š TŠḤ[N] “Mukīn-abūa the head (re’š) of Tušhan”

The Başbük Rock Wall Panel

Başbük, Türkiye

c. 750 BCE?

Wall picture of several Syro-Anatolian deities.

Drawings by Selim Ferruh Adalı

Source:

ANE Today (News Article)

Cambridge Core (Original Article from Cambridge University Press)

#shamash#sin#yarach#yarich#baal#hadad#adad#baal hadad#astarte#ashtart#atargatis#atarata#syn#kubaba#canaan#canaanite gods#phoenicia#phoenician gods#aram#aramean gods#syria#syrian gods#levantine gods#mesopotamia#mesopotamian gods#pagan gods#polytheism#archeology#magic#witchcraft

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Je reviens à mon projet de présenter la plupart de mes 55000 photos (nouveau compte approximatif. On se rapproche du présent !).

2016. Une petite virée à Bruxelles avec Julien. C’était surtout pour visiter une expo sur l’Anatolie au Palais des Beaux-Arts:

- Tarhunzas, dieu hittite de l'Orage - Niğde, 700 av.J-C.

- dieu hittite - Çiğdem- Akacaköy, XIIIe s.av.J-C.

- déesse Kubaba - Karkemish, 800 av.J-C.

- Matar, déesse phrygienne et un démon - Etki, VI e s. av.J-C.

- l’Artémis d'Ephèse - 2ème s. apr.J-C.

- Athéna période romaine - Miletopolis, IIe s. apr.J-C

- Poséidon période romaine - Sagalassos, IIe s. apr.J-C.

#souvenirs#belgique#bruxelles#palais des beaux-arts#turquie#anatolie#archéologie#mythologie#divinité#tarhunza#hittite#orage#nigde#çigdem#akacaköy#kubaba#karkemish#phrygie#matar#démon#monstre#etki#artémis#artémis d'éphèse#éphèse#efes#athéna#poséidon#grèce antique#rome antique

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kurak Topraklar, Salt Beyoğlu.

https://saltonline.org/projects/exhausted/

#saltbeyoglu#2021#beyoglu#salt#museum#bereketli hilal#fertile crescent#kubaba#carchemish#kargamış#goddess#tanrıça

0 notes

Text

Translated from Arabic

The most famous women in the history of Mesopotamia

Kubaba The first queen and the first warrior in history, 25th century BC

Shibad A Sumerian princess, priestess, and wife of King Mescalamduke, 26th century BC

Enheduanna The first poet, the first high priestess, and the first to sign her name to literary works Daughter of Emperor Sargon of Akkad, 23rd century BC

0 notes

Text

Ngahamba ekhaya ngimncane ngazi inhlonipho, ngabuya sengigugile ngazi inhluphekho.

Nyembezi zami zigcwele uthuli, zihlathi zami ziphihlika udaka.

Impilo yami? Ucwephe lephepha, ngine mfundo yeminyaknyaka kepha ulwazi lami luncane luyateketa. Ngilalele ngendlebe kwaze kwakhanya ilanga kanti kwakufanele ngilalele ngenhliziyo.

izandla zes'khathi azisafinyeleli umphefumulo udukile, indonga zidume kwazwakala, noma ngihleka kuvela ubala, sewasapa ezinkambeni amazinyo indoda.

Imizwa yami? ididekele, ime ndawonye ibindekile. ukube ngangazile ngabe ngavuma ukuba ingane kubaba kodwa ngakhetha ukuba ingane yezizwe.

ngakhetha inyuvesi ngafunda; yakhononda imizwa yakhihla es'kaShaka.

Sengihlala ngiyotyiwe, ngonyiwe, amanzi awasazigezi izithende zami, umphimbo wam', amakhala ami, amaphaphu ami, amaphupho ami, impuphu ekhaya, kugoqana unwele, esolwathamba ekwephuphu linethile.

Noma likhipha umkhov' etsheni kweyami inhliziyo likhithikile. ngigula okwangempela, kaze ngiyolitholaphi ikhambi? mhlawumbe ebhodleni, nginekeni ushevu - ngiphile. nginiken' ikhambi - ngife.

esami isono ngiyasazi, ukugijimisa ulwazi kodwa iqiniso ngalishiya ekhaya. mama, mama, uqinisile uqinisile, ngezenzo zami ngikubulale usaphila.

kungaphela izinkulungwane zeminyaka, ihlazo lami linomsindo okweqaqa. unembeza wami soze walifihla. noma izandla zeskhathi zingathi umzimba wami aw'mbozwe inhlabathi, ngizolivuma icala lam'.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The myth of Dionysos (1)

What’s better to complete this Christmas season, alongside some Arthuriana and some ghost stories, than some Greek mythology?

There is a great book in France that serves as a key research reference, and that is called the Dictionary of Literary Myths, composed under the direction of Pierre Brunel. Within this bookthere are several articles covering the complexity and evolution of the Greek gods, both within their own mythology and within European literature as a whole (with a strong focus on French literature, of course, being a French book). Given I do not know if the book was ever translated or not, I thought I’d share some of the text within it. And to begin, I will focus on one of the several articles dedicated to Dionysos – the god you English speakers known as “Dionysus” (even though the whole -us thing stays completely weird for me who grew up with all the Greek names ending in -os). This first article, written by Alain Moreau, is titled “The Antique Dionysos: The Elusive One”, and as the title says, it is a study of the figure of Dionysos within Antiquity.

I will offer here a vaguely-faithful translation of the text – and given it is a longarticle, I will break it down over several parts.

THE ANTIQUE DIONYSOS: THE ELUSIVE ONE

Of all the gods of Olympus, Dionysos is the one whose character is the hardest to define. Despite his many historical uses and the numerous interpretations of mythologists, we cannot fully understand the god. His origins, his childhood, his physical appearance, his behavior, his role in the city, his symbolism… It is all rich, all complex, all fleeting. Dionysos is the god of metamorphosis: the elusive one.

I) The origins: Old god, new god

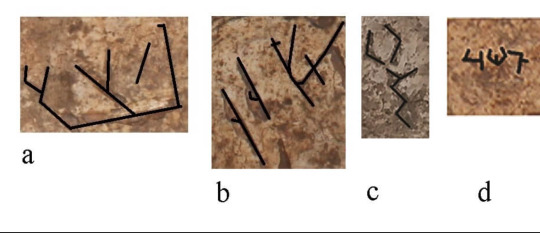

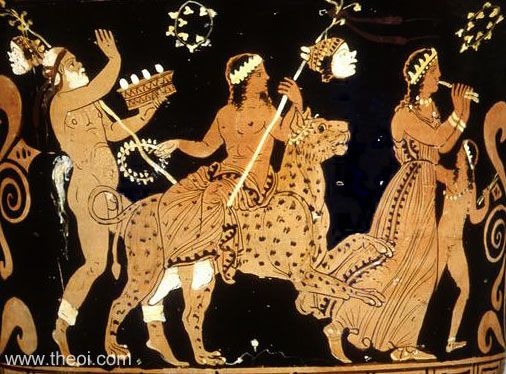

The impossibility to confine Dionysos within a specific setting already manifests in the beginning of this investigation: the research of the god’s origins is puzzling. There is no doubt that Dionysos is a very ancient god. He was called “Dendrites”, “god of the tree” – and he was even depicted with branches growing out of his chest – which links him to the oldest deities of vegetation and fecundity, the ancient mother-goddesses. For example, the Greek Demeter: Callimachus’ Hymn to Demeter says “Everything that huts Demeter also hurts Dionysos”, and Pindar names him “the consort of Demeter” in his Isthmics. Dionysos is also linked to Cybele, and though her to the Syrian goddess Kubaba – the Dionysos-Cybele link is made clear in Euripides’ Bacchants. There is also the Phrygian mother-goddess Zemelo, whose name sounds strangely like Dionysos’ mother’s, Semele. And all these deities were worshiped in Asia Minor, in Thrace, in Crete, and in the Aegean world. In Athens, very ancient festivals partially celebrate him; Anthesteria, Apaturia, Oschophoria… It explains why Tiresias, in the Bacchants, speaks of “traditions that come from our fathers, and whose age is as old as time itself”. All points out to the Dionysian cult having pre-Hellenic roots. During the Mycenaean era in the middle of the second millennium BCE, his presence was attested by two tablets found at Pylos written in linear B. The name of Dionysos is found in its genitive form: “diwonusoyo”. Bacchants gives us another clue about the ancient nature of the god: beyond the tragedy-of-impiety that is the death-punishment of Pentheus, one can sense a second level of comprehension, maybe hidden to the play’s creator, but that mythologists and ethnologists all perceived. That is to say, a ritual of human sacrifice – the tragedy takes its root in a primitive rite.

And yet, the historian Herodotus claims in his Histories that the name of Dionysos is the last one that the inhabitants of Greece learned when discovering their gods, while Pentheus and Tiresias in Bacchants both call Dionysos a “new god”. A new god, because he is foreign, supposedly coming from Thrace or Asia Minor. Ancient Greeks analyzed his name as coming from a fabulous land, whose exact location kept changing from person to person, but that was always outside of the Greek world: Caucasus, Ethiopia, India, Arabia, Egypt, Libya… Numerous myths tell of the strong difficulties that the cult of Dionysos had to face when implanting itself in Greece – especially in Boeotia, the land of Dionysos’ mother, Semele (who herself was the daughter of Cadmos, the founder of Thebes). Mythologists themselves were fooled and, up until a recent date, most of them believed that Dionysos was a latecomer to the pantheon, an imported god.

Where does this contradiction comes from? It is probably because of how unique the worship of Dionysos was: religious possession, orgiastic rituals, running races throughout the mountains… It always made him an eccentric, isolated god, a god of the people rather than a god of the aristocracy (he plays almost no role within the works of Homer), and as such a much less prestigious deity than the other Olympians. But Dionysos had his revenge: starting from the 8th century BCE onward, it seems that the god “woke up” and was brought back under the spotlight, thanks to women, who spread his cult. Various religious movements coming from Phrygia, Lydia, Thrace and the Greek islands also helped this renewal by revitalizing the old forms of the cult and accentuating its orgiastic aspect. The rise of Oriental cults in Athens at the end of the 5th century made everything go even faster. All these outside additions explain why the Greeks themselves felt that Dionysos was a foreigner and a “new” god. All in all, this look at the god’s origins accentuates one of his most fundamental characteristics: the impossibility to clearly define his personality.

II) A very complicated childhood: births and rebirths

The childhoods of Dionysos all bear the same strangeness. He is a god that is constantly born and that constantly dies, before escaping those that hunt him down, and finally imposing himself definitively. Let’s take a look.

1) Semele, beloved by Zeus, follows the wicked advice of the jealous Hera, and asks the king of the gods to appear before her in his full, shining glory. Zeus, who had made the solemn promise to grant any wish Semele would make, has no other choice but to obey. He appears to her wrapped and surrounded by thunder and lightning, and the poor Semele dies because of it. She was in her sixth month of pregnancy – and Zeus saved Dionysos from death, by ripping the fetus away from his mother’s belly, and placing it in his own thigh. There, Dionysos finished his growth during three more months, before finally being “born” out of Zeus’ leg. This is why one of the etymologies of “Dionysos” means “the god born twice”. In France, it also led to the common expression “se croire sorti de la cuisse du Jupiter” ; “to believe one’s got out of Jupiter’s thigh”.

2) The god Hermes, by order of Zeus, gives the child to king Athamas and queen Ino, rulers of Orchomenos. They raise the little Dionysos by forcing him to wear feminine clothes, in hope that Hera will not recognize him disguised as a girl. Unfortunately Zeus’ wife is not fooled, and she turns Dionysos’ foster parents insane. Zeus then transports his child towards Nysa, and entrusts him to the nymphs of the region. This time, it is said that he was turned into a kid (as in a baby goat). In the Homeric version of the story (found in Iliad, VI), Nysa is replaced by “the divine Nyseion”, a Thracian mountain where rules king Lycurgus. Lycurgus ended up hunting down the nurses of the child and wounding them – the terrified Dionysos jumped into the sea to flee the attack, and ended up protected by the goddess Thetis. [Note: Jeanmaire offered an alternative reading of the Homeric tale, proposing that maybe the Nyseion was actually the name of the "country of the Nysai", aka the land of the Nymphs, which would make it an Ancient Greece version of Elfland or Fairyland]

3) Finally, there is the Cretan legend of Dionysos-Zagreus. While the legend was only recorded by very late text, in truth it seems to be a very ancient story: the name Zagreus first appears in the 6th century BCE in the Alcmeonis, and then came back in the first half of the 5th century within Aeschylus’ Sisyphus the Runaway. In the Zagreus story, Dionysos is given a new group of nursing parents: the Kouretes. As they dance with their weapons around the child and do not pay attention, the Titans discreetly reach Dionysos-Zageus and lure him away using toys (a ball, a spinning top, a mirror, a fleece, jackstones, apples, a bullroarer…). Once they had him, the Titans killed him, dismembered him and cooked the pieces of his body within a cauldron before roasting them and eating them. Zeus struck the Titans with his lightning, but hopefully could resurrect the young god, using his still-beating heart that had been saved by Athena from the Titans’ gruesome feast.

Next time: The Shapeshifting God, and A Complex Personality

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

Is there any information about Mukishanu outside of his roles in the Song of Hedammu and Song of Ulikummi? I'm assuming there's little to nothing, but but I'm curious either way.

There indeed isn’t much otherwise. As far as I am aware, the brief survey given by Gernot Wilhelm in the Reallexikon is still up to date.

All of the available attestations of Mukishanu come from Hattusa - from Hurrian or at least Hurrian-adjacent sources. The bulk of them are passages from Song of Hedammu and Song of Ullikummi, plus some which according to Wilhelm cannot be placed in either with certainty but belong to the same cycle at the very least. As far as I know, none of these ever go beyond the usual formula “Kumarbi repeats a message he wants to send, Mukishanu leaves to deliver it”.

On top of the literary sources there is a single ritual text which mentions Mukishanu, a list of offerings connected with the cult of Shaushka of Samuha (CTH 712). It’s a peculiar oddity in that every single deity listed in the relevant passage is a sukkal, and explicitly identified as such. I’m not aware of any parallels to this from any part of the “cuneiform world”. The ritual is not very informative, though, it just repeats the formula “a flatbread for x sukkal of y”. No reason is given for gathering attendant deities like that. Perhaps they’re unionizing or something.

More under the cut, including some speculation.

Wilhelm doesn’t discuss CTH 712 beyond Mukishanu’s appearance in it, but it’s not hard to find a full list of the deities invoked, for example here, p. 370: Undurumma (Shaushka’s), Tenu (Teshub’s), Mukishanu (Kumarbi’s), Izzumi (ie. Mesopotamian Isimu/Usmu; Ea’s); Lipparuma (Shimige’s) and Ḫupuštukar (Ḫešui’s). Most of them are relatively well attested, but there are two peculiarities: Undurumma is pretty much unattested otherwise (in the overwhelming majority of ritual and literary texts and in visual arts Shaushka almost invariably appears with Ninatta and Kulitta, so you’d expect them to have this role, but nope) and Ḫešui is himself quite rare so learning he was major enough to have an attendant is quite surprising (granted, there is a theory he was worshiped more commonly earlier on or in different Hurrian communities as these which influenced the Hattusa archive). It also strikes me as odd that Hebat and Takitu are missing.

The only other information about Mukishanu comes from the etymology of his name. While he is attested exclusively in Hurrian and Hurro-Hittite sources, his name actually comes from a Semitic language (I am not aware of any more precise attempts at identification) and means something like “he from Mukish”. This term referred to the area around Alalakh. As discussed here (p.3 ) by Alfonso Archi, it essentially underwent cultural “Hurrianization”: by the fourteenth century, about three fourths of its inhabitants mentioned in textual sources bore Hurrian names, and the ritual text CTH 780 mentions an apparently famous Hurrian expert from Mukish, a certain ms. Allaituraḫḫi. The calendar was seemingly Hurrian too, though with one month name - Pagri - goes back to an Akkadian term (pagrum, a ceremony for the dead).

We don’t have much in the way of religious texts from Alalakh. The local pantheon attested in royal documentation was discussed briefly in Volkert Haas’ Geschichte der hethitischen Religion (p. 556-557). There is evidence for Teshub, Ishara/Shaushka/Ishtar (the writing is logographic and notoriously hard to untangle in this case; I think the evidence for Ishara is the strongest), Hebat, Kubaba, Umbu (a moon god or at least a name of the Hurrian moon god) and earth and heaven. There is also at least one reference to the worship of Kumarbi as well, and to a temple of a deity named Kūbi, see here, p. 207. Mukishanu is notably absent, though, and I haven’t really seen any proposals regarding this state of affairs. I personally see two possible solutions: Mukishanu was an epithet or generic designation which developed into a separate deity; or alternatively he represented the image of inhabitants of Alalalkh in the eyes of another group (much like how Amurru was not actually an Amorite god despite his name). However, this is just my own speculation. It’s also worth noting that Gary Beckman at least seems to imply he assumes Mukishanu was actually worshiped in Alalakh or somewhere nearby, since he counts his presence in the Kumarbi cycle as an argument for seeking its origin across Upper Mesopotamia and northern Syria rather than in Anatolia here (p. 25).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

As with other history women's history begins with kings and battles for very specific reasons:

One of the various elements that goes into all history, not just women's history, is that history begins with a vastly different world where less than 5% of the population could read and write, and where histories worked very differently and reflected the literate audience of the time. As a general rule scribes were overwhelmingly masculine and had some of the usual cliquish elements of such groups then and now. This is why an overwhelming number of the women who appear in more traditional, as opposed to the harder and deeper work of social histories, are elites, rulers and nobles, and why the view of women's lives is shaped by that of an elite caste who were not necessarily typical by any means of how most women lived, any more than their male counterparts were of men at the time.

This is also why women's history tends to zero in on specific personalities who rose both in spite and because of these biases in specific ways, a pattern that lasts well into the 20th Century in different parts of the world. In this case a bartender named Kubaba became one of the rulers of Kish, which at the time was the central hegemon of all Sumer, and in this sense could retroactively be called the first Empress. She predates Sobeknefru and Hatshepshut by a millennium, and this too makes a point about the nature of elites and power. The women who were parts of these groups were always able to fit into various holes, so to speak, in how power worked and to seize and hold it in various ways.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Statues of two great kings from Mesopotamia.

They are Queen Kubaba and King Sargon of Akkad

The common characteristic between these two kings is that they were not of royal origin, but were of the common people, but they were able to reach the seat of power, and achieved impressive victories that are known for the first time in history!

Queen Kubaba is the first Mesopotamian woman ruler known to history, she ruled within the limits of the period between (2500-2330) BC, where her name was mentioned in the list of Sumerian kings, and she did not descend from a royal family, but was a woman from the common people who was able to reach the throne

Queen Kubaba led a fierce war against the king of the city of Mari and defeated him, as well as defeated the king of Kishak and annexed that city to her kingdom.

In doing so, Queen Kubaba is the first female ruler to lead and win a war in human history.

As for King Sargon of Akkad, he was proud of being a commoner, as he worked as a butler for the king, but he was able, with his intelligence and ambition, to reach the throne and rule in the period between (2334-2279) BC.

King Sargon of Akkad possessed the strength of personality and the spirit of leadership, so he was able to win 35 wars throughout his reign, unite the states, and establish the first great empire known to history, which is the Akkadian empire.

#real_history

The first female ruler to fight a war and win it in human history, and the first person to establish the first empire in history, were from Mesopotamia.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tons of monarchs make an appearance on the Sumerian King List, but there’s only one lady Kubaba. The Chronical of rulers that often straddles the boundary between history and legend, provides us with the little information we do know about her.

The Sumerian queen Kubaba was a true monarch. A queen regnant who ruled in her own right, rather than a queen consort, who is simply the wife of the monarch. The King List refers to her as Lugal (king), not as Eresh (queen consort). She is the only woman to bear this title.

Well known rulers who were strong women in antiquity is Egypt, the country of the pharaohs Sobekneferu, Hatshepsut, and Cleopatra. Very few women ever rose to power in the kingdoms and empires established in the Near East, Asia, and Europe. These women often first accessed their power through men (fathers, husbands, brothers, and sons).

#history#archeology#archeologicalsite#ancient sculpture#ancient sumeria#strong women#sumerian kings list#ancient civilizations

0 notes

Text

By the end of the second millennium, the religious thinkers of Mesopotamia saw the cosmos as controlled and regulated by male gods, with only Ishtar maintaining a position of power. When we see such a pattern of theological change, we must ask whether the religious imagery is leading society, or whether it is following socioeconomic development? Was the supplanting of goddesses in Sumerian religious texts an inner theological development that resulted purely from the tendency to view the world of the gods on the model of an imperial state in which women paid no real political role? Or does it follow in the wake of sociological change, of the development of what might be called "patriarchy"? And if the latter is true, is the change in the world of the gods contemporary to the changes in human society, or does it lag behind it by hundreds of years? To these questions we really have no answer. The general impression that we get from Sumerian texts is that at least some women had a more prominent role than was possible in the succeeding Babylonian and Assyrian periods of Mesopotamian history. But developments within the 600-year period covered by Sumerian literature are more difficult to detect. One slight clue might (very hesitantly) be furnished by a royal document called the Reforms of Uruinimgina." Uruinimgina (whose name is read Urukagina in earlier scholarly literature) was a king of Lagash around 2350 B.C.E. As a nondynastic successor to the throne, he had to justify his power, and wrote a "reform" text in which he related how bad matters were before he became king and described the new reforms that he instituted in order to pursue social justice. Among them we read, "the women of the former days used to take two husbands, but the women of today (if they attempt to do this) are stoned with the stones inscribed with their evil intent." Polyandry (if it ever really existed) has been supplanted by monogamy and occasional polygyny.

In early Sumer, royal women had considerable power. In early Lagash, the wives of the governors managed the large temple estates. The dynasty of Kish was founded by Enmebaragesi, a contemporary of Gilgamesh, who it now appears may have been a woman; later, another woman, Kubaba the tavern lady, became ruler of Kish and founded a dynasty that lasted a hundred years. We do not know how important politically the position of En priestess of Ur was, but it was a high position, occupied by royal women at least from the time of Enheduanna, daughter of Sargon (circa 2300 B.C.E.), and through the time of the sister of Warad-Sin and Rim-Sin of Larsa in the second millennium. The prominence of individual royal women continued throughout the third dynasty of Ur. By contrast, women have very little role to play in the latter half of the second millennium; and in first millennium texts, as in those of the Assyrian period, they are practically invisible.

We do not know all the reasons for this decline. It would be tempting to attribute it to the new ideas brought in by new people with the mass immigration of the West Semites into Mesopotamia at the start of the second millennium. However, this cannot be the true origin. The city of Mari on the Euphrates in Syria around 1800 B.C.E. was a site inhabited to a great extent by West Semites. In the documents from this site, women (again, royal women) played a role in religion and politics that was not less than that played by Sumerian women of the Ur IlI period (2111-1950 B.C.E.). The causes for the change in women's position is not ethnically based. The dramatic decline of women's visibility does not take place until well into the Old Babylonian period (circa 1600 B.C.E.), and may be function of the change from city-states to larger nation-states and the changes in the social and economic systems that this entailed.

The eclipse of the goddesses was undoubtedly part of the same process that witnessed a decline in the public role of women, with both reflective of fundamental changes in society that we cannot yet specify. The existence and power of a goddess, particularly of Ishtar, is no indication or guarantee of a high status for human women. In Assyria, where Ishtar was so prominent, women were not. The texts rarely mention any individual women, and, according to the Middle Assyrian laws, married women were to be veiled, had no rights to their husband's property (even to movable goods), and could be struck or mutilated by their husbands at will. Ishtar, the female with the fundamental attributes of manhood, does not enable women to transcend their femaleness. In her being and her cult (where she changes men into women and women into men), she provides an outlet for strong feelings about gender, but in the final analysis, she is the supporter and maintainer of the gender order. The world by the end of the second millennium was a male's world, above and below; and the ancient goddesses have all but disappeared.

-Tikva Frymer-Kensky, In the Wake of the Goddesses: Women, Culture, and the Biblical Transformation of Pagan Myth

#Tikva Frymer-Kensky#Ishtar#female oppression#mesopotamian mythology#goddess erasure#ancient history#religious history

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kuttamuwa Stele Sam´al / Bit Gabbari Modern Zincirli Höyük, Turkey c. 8th Century BCE

The stele measures three feet tall and two feet wide. It was a stele for Kuttamuwa, an 8th-century BCE royal official from Sam'al who ordered an inscribed stele, that was to be erected upon his death. The inscription requested that his mourners commemorate his life and his afterlife with feasts "for my soul that is in this stele." It is one of the earliest references in a Near East culture to a soul as a separate entity from the body.

The translation of the stele:

"I am KTMW (Kuttamuwa), servant of Panamuwa, who commissioned for myself (this) stele while still living. I placed it in an eternal chamber and established a feast (at) this chamber: a bull for Hadad Qarpatalli, a ram for NGD/R ṢWD/RN, a ram for Šamš, a ram for Hadad of the Vineyards, a ram for Kubaba, and a ram for my “soul” (NBŠ) that (will be) in this stele. Henceforth, whoever of my sons or of the sons of anybody (else) should come into possession of this chamber, let him take from the best (produce) of this vine(yard) (as) a (presentation)-offering year by year. He is also to perform the slaughter (prescribed above) in (proximity to) my “soul” and is to apportion for me a leg-cut." Source: Wikipedia

#Kuttamuwa#funerary stele#stele#table#food#offering#chair#aramean costume#aram#aramea#canaan#phoenicia#syria#levantine gods#pagan gods#polytheism#archeology#magic

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

L'Alchimia delle Anime - La Prima Prova (on Wattpad) https://www.wattpad.com/1400424993-l%27alchimia-delle-anime-la-prima-prova?utm_source=web&utm_medium=tumblr&utm_content=share_reading&wp_uname=AA_Black&wp_originator=RM%2Bk5XUWtnSpY%2BR2YafyKRf%2F2KZYZXI7hT9jJ8JjZOM1QOFtf9Xdj5EdePxfnyd61y%2BhjAto51y5oZ%2BqIrc1tqjZq7rAD2Jimd27l7f%2FdFEmLA2Fu6ZDL6oX37d82ttc

Anù vive nella mente. Haru vive nel cuore. Lei è una delle migliori NeuroProgrammatrici. Lui è uno dei migliori PsicoEmpatici. Anù può leggere la mente di chiunque, tranne quella di Haru. Haru può sentire le emozioni di tutti, ma non quelle di Anù. In un mondo diviso tra Koriani e Terrestri, sull'isola di Terra, a comandare, sono i Dharmici ed i Karmici. Sono coloro che hanno raggiunto il livello più alto di consapevolezza e che hanno il potere di ordinare gli Elementi. Anù è una Dharmica, una ricercatrice dell'Equilibrio. Asteria invece è la figlia della Kubaba, la capo tribù dei figli di Gemeter. Coloro che fanno si che le leggi del Karma vengano rispettate. Anù è alla scoperta di se stessa, Asteria invece ha uno scopo ben preciso. Eliminare tutti i figli di Gemeter. Tra storie d'amore che vanno oltre la dimensione fisica e conoscenze che viaggiano attraverso i piani di esistenza, Anù e Asteria comprenderanno qual è il vero scopo della vita su Terra. Faranno esperienza di Amore, nella sua forma più pura e primordiale. E performeranno... L'Alchimia delle Anime.

#accademia#alchimia#amore#anime#artimarziali#azione#darkfantasy#elementi#fantascienza#fantasia#fantasy#magia#oscurit#romance#romanticismo#spirituale#youngadult#storie-damore#books#wattpad#amreading

1 note

·

View note

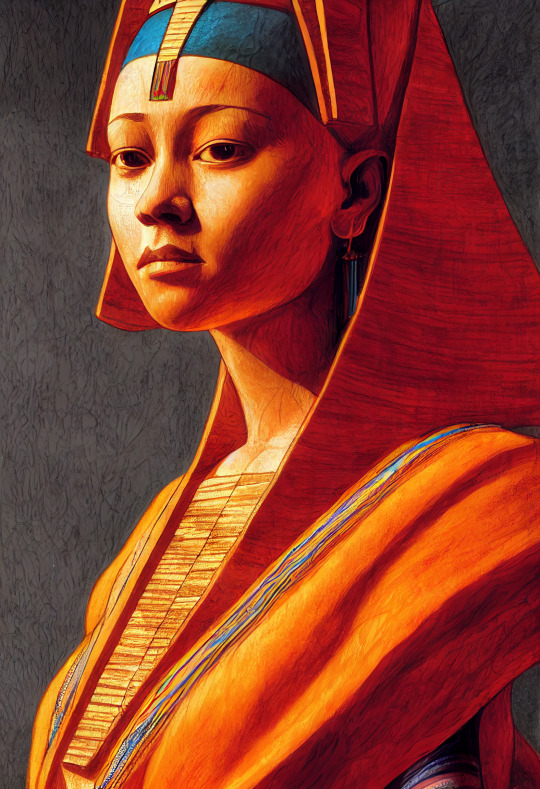

Text

Ancient Queens, mostly Queens Regnant, made by Midjourney, in the style of Leonardo da Vinci. I'm pretty sure Midjourney got many of them horribly wrong. 1 Kubaba of Sumeria 2 Hatshepsut of Egypt 3 Nefertiti of Egypt 4 Elissa "Dido" of Carthage 5 Queen of Sheba 6 Semiramis of Assyria 7 Salomé Alexandra, Queen of Judea 8 Cleopatra VII of Egypt 9 Boudica of the Icenia, Britain 10 Zenobia of Palmyra 11 Medb of Connacht, Ireland 12 Empress Theodora

#Midjourney#AI Art#Ancient Queens#portraits#Kubaba#Hatshepsut#Nefertiti#Dido#Queen of Sheba#Semiramis#Salomé#Cleopatra#Cleopatra VII#Boudica#Zenobia#Medb#Theodora

217 notes

·

View notes