#Kenji Nakagami

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mitsuo Yanagimachi

- Fire Festival

1985

#柳町光男#mitsuo yanagimachi#中上健次#kenji nakagami#火まつり#fire festival#japanese film#1984#ending#sea#sunset#fire

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

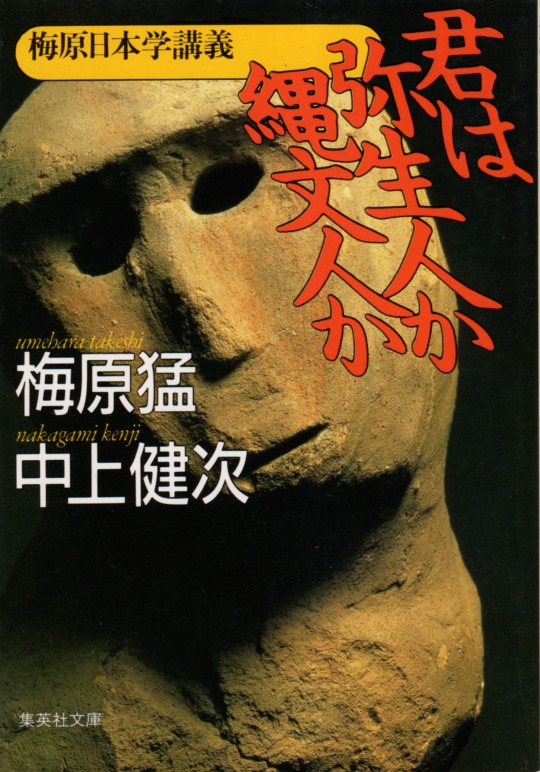

君は弥生人か縄文人か-梅原日本学講義 梅原猛・中上健次 集英社文庫 デザイン=菊地信義

#君は弥生人か縄文人か-梅原日本学講義#君は弥生人か縄文人か#梅原日本学講義#takeshi umehara#梅原猛#kenji nakagami#中上健次#集英社文庫#nobuyoshi kikuchi#菊地信義#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#book cover

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

2024/03/12 English

BGM: 中谷美紀 - STRANGE PARADISE

I worked early today. At this lunchtime, I asked to myself this question - Why do I work? Maybe I could get any welfare to live on from this government without having any stresses… I remember that I've been working at this company for about 20 years. Why? I ask this to myself, but it seems nothing comes upon my mind. Why? This life seems really full of enigmatic essences…

I won't say that NEET (the person who has not been employed by any companies) must be bad, because once I was one of that kind of NEET. At that "blank" period, I had just read many books (Kenzaburo Oe, Haruki Murakami, Kenji Nakagami, etc.) to kill the boring time, and been soaked myself into gallon of alcohol. That kind of NEET or hikikomori period sometimes come to us as a kind of inevitable event. I believe that's life.

But, I have kept on working by now… Even now, I can't feel this job is a calling of mine. I ALWAYS keep on thinking that my talented ability must be to write something like this. But, even almost everyday I have to face a lot of bothersome events, I don't stop working… just because I am basically a poor Japanese? Too square Japanese…

Once, in my 30s, I had gotten into some social media activities. Even during my work, my mind had gotten into those media to post something cool to get buzzed. Oh, what a shame! At that time, I couldn't have found any funny/humorous events in my life, therefore I wanted to run away from the poor reality. Now, I can accept that I should stay on this earth to live this real life… I have written this as today's homework to show the teachers.

This evening, we had the final lesson of English class in this semester/season. At the first half of this class, we enjoyed listening to the songs as Ben E. King and ONE OK ROCK (this is a popular Japanese band.) to train our ability. After that, we started enjoying a chatting time. This kind of opportunity of communication in English is so RARE for me in this life, therefore I really appreciate this. After that class (or the party,) we took some memorial pics of the class.

0 notes

Photo

The Millennial Rapture (Kôji Wakamatsu, 2012).

31 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Albert Ayler - Ghosts: First Variation (1965)

アイラーは、今、耳にすると、暗い。ただ、本当の事を、ジャズで吹いている。 - 中上健次『破壊せよ、とアイラーは言った 』

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

拙著『燃エガラからの思考』刊行記念対談のご案内など

ここ福岡ではようやく秋の深まりが肌で感じられるようになってきましたが、いかがお過ごしでしょうか。来たる11月24日(木)の19:00より、七月に上梓した拙著『燃エガラからの思考──記憶の交差路としての広島へ』(インパクト出版会)をめぐって、中国文芸研究会──その読書会のことは、拙著第二部の「残余の文芸のために」に書かれています──の行友太郎さんとオンラインで対談します。広島/ヒロシマの現在を「軍都」の歴史を踏まえながら問い、「破局の残骸を継ぎ合わせ、核の普遍史に抵抗する連帯の場を開く」(帯文)ことを追究する思考を芸術論を中心にまとめた拙著を紹介する機会を設けてくださった誠品生活日本橋の神谷康宏さんに心より感謝申し上げます。 一緒に観たテント芝居──『図書��聞』第3564号に行友さんが寄稿された今夏の野戦之月の公演「TOKIOネシア荒屋敷予想《鯨のデーモス》」の劇評「分解は止まらない」は…

View On WordPress

#Azumi Tamura#燃エガラからの思考#Eri Watanabe#Franz Schubert#Impact Press#Inscript#Izumi Hall#Jean-Luc Godard#Jupiter#Kenji Nakagami#Kinyobi#Masae Yuasa#Mercure des Arts#Nobuyuki Kakigi#Nouvelle Vogue#Peace Studies Association of Japan#Seihin Seikatsu Nipponbashi#Shiho Azuma#Takefu International Composition Workshop#Takefu International Music Festival#Taro Yukitomo#Theodor W. Adorno#Tomohei Hori#Yasuhiro Kamiya

0 notes

Text

To the hijiri, the sound of wind blowing over bamboo leaves was the sound of his own throat, the sound of life rising from every pore of his skin.

—Nakagami Kenji, The Immortal (The Shōwa Anthology, Modern Japanese Short Stories)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Los escarabajos de tierra empezaban a zumbar. Si aguzaba el oído podía escucharlos a lo lejos, como un runrún en los oídos. Seguirían así toda la noche. Akiyuki imaginó el frío olor de la tierra nocturna.

Su hermana entró con un gran plato de carne. «¡Eh, bebe con nosotros!» le dijo Kuda levantando una botella de cerveza. «Yo no bebo —respondió Mie dejando el plato junto a la parrilla de carbón—. Me da miedo. Tienes esa cosa en la sangre y te mata el cerebro. Nada más verlo a él bebiendo ya me da fatiga.» Habló con intención, sin mirar a Kuda, sino a su hermano Akiyuki, que tenía la cara roja tras beber sólo un vaso de cerveza, el corpachón encorvado y el aliento en candela. Mie sonrió, a punto de llorar. Kuda no tenía intención de empujar a Mie a beber, solo pretendía agradecerle que trajera carne y cerveza para él y los demás empleados.

—¡Venga, bebe! —barbulló Mitsuko desde el otro lado de la mesa—. Olvídate del jefe de vez en cuando y disfruta.

—No, no puedo —Mie sacudía la cabeza, sin dejar de sonreír.

—Vamos, tómate una —Mitsuko cambió de postura y cruzó las piernas, Akiyuki pudo verle las bragas color durazno, de encajitos.

—¡Oye, tápate, mujer! —dijo riendo su marido Yasuo, sentado a su lado. Se puso a tirarle de la falda, que se le había subido sobre las rodillas.

—¿Qué pasa por enseñar un poco? ¡Tengo para todos! —y Mitsuko rechazó a Yasuo dándole un empellón—. Deja que te diga, Yasuo, yo no soy como la Mie. Yo he trotado lo mío. Más de lo que te figuras.

Mie recogió las botellas vacías y volvió a la cocina. La puerta de la casa y las ventanas estaban abiertas de par en par. Después del trabajo los hombres habían empezado a beber en la oficina entarimada donde el jefe tenía su mesa. Los niños del barrio se asomaban a mirar, curiosos. Los hombres estaban sentados en semicírculo de cara al callejón. Una brisa se llevaba calle abajo los olores de la carne asada, el hierro y el polvo de la casa del jefe. El aire trascendía los olores fríos de las macetas que cuidaban los viejos y las viudas, de las zanjas y de la noche que se venía encima rápidamente.

—¡A beber, a beber, a beber! ¿Qué más da si nos quedamos tontos? —voceó Yasuo, levantando la botella de cerveza—. Nadie aquí era ninguna lumbrera ya de antes —Akiyuki trasegó su vaso y Yasuo se lo volvió a llenar.

—En mi familia somos famosos por lerdos —dijo Mitsuko. Los palillos que estaba usando para volver la carne se prendieron—. Si me escucha mi hermano, me mata; pero es la verdad —y sacó la lengua.

—El jefe no es lerdo, tiene cabeza —terció Fujino.

—Eso te parece a ti. Lo dices porque es tu jefe, pero es de mi sangre. Mi segundo hermano mayor, si nos ponemos pamplinosos. Pero nos criamos juntos y siempre me pareció un imbécil. ¿Quién lo va a saber mejor que yo?

—¡Deja de rajar de mi hombre! —chilló Mie desde la cocina. Mitsuko volvió a sacar la lengua.

—Pero digan lo que digan —Mitsuko se volvió a su marido y le dio de coscorrones—, tú vienes de la mayor casta de idiotas. Incluso peor que la mía. ¿No fue tu abuelo el que se metió con una puerca que le pegó purgaciones? Y de ahí salió tu padre ¿no?

Yasuo soltó un carcajada desde las tripas. No parecía que la bebida le hiciera nada. Yasuo sobrio era manso como un gato, alegre, trabajaba como el que más; dejaba que Mitsuko se metiera con él. Ahora, Yasuo borracho ya era otra cosa.

Mie llamó a Akiyuki y éste fue a la cocina: —¿Que tal si dejas de beber y me acompañas a casa de madre? Me da miedo la carretera de noche.

—¿Y qué tienes que hacer allá? —preguntó Akiyuki, hasta la voz le ardía con la bebida.

—Es por el oficio de difuntos de papá —respondió Mie—, me tienes que hacer de guardaespaldas. Cuando te vean, nadie se meterá con nosotros.

—Qué cagona eres, Mie —saltó Mitsuko desde la oficina—, no podrías vivir en la casa de la playa.

Mitsuko se puso a contarles a todos lo miedosa que era Mie. La casa de la playa era del padre de Mitsuko; después que murió, su hijo mayor Furuichi —que trabajaba para una empresa de camiones— se había mudado allí con su mujer. Mitsuko siempre se lo echaba en cara: «Yo era la niña linda de papá. Él siempre quiso que yo viviera en la casa de la playa», decía. La casa estaba junto a los espigones de cemento de la playa. Cerca quedaban un soto plantado como cortavientos y un cementerio.

—¿Qué estás hablando? ¿Eso es ser miedosa según tú, Mitsu? —Mie agarró a Akiyuki de la mano—: Vamos, guardaespaldas. Enseguida vuelvo. Mit-chan, ocúpate de que todos tengan de beber mientras estoy fuera.

—¡Cagooooona! —le gritó Mitsuko—. Pero eso mismo te gusta de ella. No es una perdonavidas como Furuichi y la mujer. La próxima vez que pille al jefe engañándola, lo voy a colgar de un pino —Mitsuko apoyó la cabeza en el hombro de Yasuo.

La noche era fresca. Akiyuki y Mie bajaron por el callejón, cruzando el paso a nivel. Mie daba pasitos cortos, como trotando; apenas le llegaba al hombro a su hermano. Akiyuki se ató la chaqueta a la cintura. El sudor de su camiseta de algodón se heló de pronto que era un gusto. Había bancos con tiestos a la orilla del callejón. El aroma de las flores colmaba el aire. Siguieron la revuelta, cruzaron una calle que venía de la estación y tomaron un sendero entre los campos de cultivo. De nuevo sonó el zumbido de los insectos en los oídos de Akiyuki. Cogiendo un camino que salvaba un mogote, pasaron junto a una vaqueriza.

—Vienen todos otra vez al oficio de papá —dijo Mie. Luego lo interpeló, así de golpe—: ¿Akiyuki? —él gruñó—. No tontees con Mitsuko. No me gusta. Podría causar problemas en la familia.

—Está bien —dijo él. A cada paso le rozaban los pantalones de faena y caminaba separando las piernas. Los chanclos tipo tabi que llevaba no hacían ruido ninguno. Un cochecito se acercó y los cegó con sus luces. Se pararon un momento para que pasara y Mie levantó la vista hacia su hermano. Un dulce olor a gasolina los envolvió.

—Akiyuki, cógeme la mano —y tomó la mano de su hermano entre las suyas.

—¡Qué chiquilla! —dijo él soltándose brusco—. ¿Te vas a asustar ahora? —Mie se la volvió a agarrar.

—Sentí ahora mismo que... Akiyuki, cógeme de la mano como hacía hermano mayor. Siempre bajábamos esta carretera de la mano los dos, camino de casa de madre. Y cuando llegábamos aquí solía decir: «¿Tienes miedo, Mie?», aunque yo no lo tenía. Pero luego sí, porque me lo había preguntado —Mie se rio bajito. Su mano era fría y prieta.

—¿Va todo bien con el jefe?

—Ajá —asintió Akiyuki.

—A veces es muy brusco —Akiyuki no dijo nada al respecto.

No eran ni diez minutos lo que se echaba desde casa de Mie y el jefe. La madre estaba en la cocina lavando los platos. «Llegáis a punto», dijo al ver a Mie, saliendo a la puerta con un paño entre las manos. «Me acaban de llamar de Nagoya —dijo ceñuda—. Era Yoshiko, dándome otro disgusto: "Pues yo soy la mayor", me dice muy hecha persona.»

—¿Dónde está padre? —preguntó Mie.

—Fue a una reunión. Fumiaki volvió a su apartamento. —Al ver a Akiyuki añadió—: Akiyuki, apúrate y tómate tu cena, luego te bañas. Te he dejado ahí una muda. —Luego, como si acabara de advertir su cara colorada, siguió—: ¿Otra vez bebiendo con los compañeros? No me digas nada mañana si te duele todo el cuerpo.

—Sólo se tomó una o dos —dijo la hermana, tapándolo.

—Un par de ellas después del trabajo —dijo Akiyuki.

—Ah, bueno, si no es más que un par —rió la madre—. Tienes veinticuatro, no quince; no es para tanto.

—Tiene la edad del hermano mayor cuando murió —dijo Mie, estudiándolo.

—Tienes razón —la madre se sentó ante la mesita baja de té. De repente pareció que se quedaba floja. Los ojos de Mie destellaron a la luz del tubo fluorescente.

—Hace nada, viniendo, sentí que el hermano estaba conmigo. Qué repelús —Mie se sentó—. Se ha puesto igual que él.

—Es verdad —asintió la madre—. Eso pienso cada vez que lo miro.

Akiyuki cenó oyendo hablar a las mujeres. Trataron del oficio de difuntos del padre. Un rato antes Yoshiko, que vivía en Nagoya, se había estado quejando por teléfono de que se celebrara en casa del padrastro. Akiyuki no estaba emparentado ni con uno ni con otro, su único vínculo con los hermanos era por parte de madre. Su padre era un hombre que vestía pantalón de faena y gafas de sol, aunque no trabajaba en la construcción, un tío con el morro de un león y el cuerpo de un jayán. Cada vez que su madre o su hermana decían la palabra padre, era en él en quien Akiyuki pensaba. De vez en cuando se lo topaba por la ciudad. Él lo llamaba; intercambiaban algunas palabras, y se acabó. El rostro y el cuerpo del hombre se parecían a los suyos. ¿Pero qué puñetas significaba aquello? Había escuchado por ahí que el hombre, por lo que parece, tenía una chiquita en el barrio rojo. Pero Mie decía que tenía que ser una hermana de Akiyuki, de otra madre. De todos los hijos del hombre con diferentes mujeres por la misma época, ésta sería la hija de una ramera, que había crecido y acabado allí. El tipo se había hecho rico de la noche a la mañana. Se decía que le había estafado a un propietario una parcela forestal y otros terrenos. Cada vez que Akiyuki pensaba en el hombre recordaba lo que oyó decir una vez a alguien: «Hay cada indeseable en este mundo...».

Las mujeres seguían charlando cuando Akiyuki terminó de comer. Todavía no habían acabado cuando entró en el baño. Sentía el cuerpo rasposo de polvo. De cintura para abajo estaba blanco como la leche, de cintura para arriba negro de sol. Se tiró encima el balde de agua caliente.

Nakagami Kenji

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

we are having a crisis about never having anything published at 2 am. i don't even really want to go back to do linguistic research anymore i don't think. i just want to write papers about my japanese animes where the girls kiss and why i think kenji nakagami fucks.

#i wrote notes in my bullet journal to start doing research#into finding ways of getting something i write out there#gods help me if i must learn to edit video

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I added 2 my tbr today...

the prophet of zongo street

The hero's walk by Anita Badami

The known world by Edward p Jones

The cape by Kenji Nakagami

The moor's last sigh by salman Rushdie

Cinnamon gardens by Shyam selvadurai

The republic of love by carol shields

Uhuru street by mg Vassangi

Brick lane by Monica Ali

Purple Hibiscus by chimamanda ngozi Adichie

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Toru Takemitsu

- Fire Festival

1985

#武満徹#fire festival#toru takemitsu#modern music#柳町光男#mitsuo yanagimachi#中上健次#kenji nakagami#火まつり#fire#1985#himatsuri#Youtube

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

俳句の時代-遠野・熊野・吉野聖地巡礼 中上健次・角川春樹 角川文庫 装幀=杉浦康平

#俳句の時代-遠野・熊野・吉野聖地巡礼#俳句の時代#kenji nakagami#中上健次#haruki kadokawa#角川春樹#角川文庫#kohei sugiura#杉浦康平#anamon#古本屋あなもん#あなもん#book cover

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

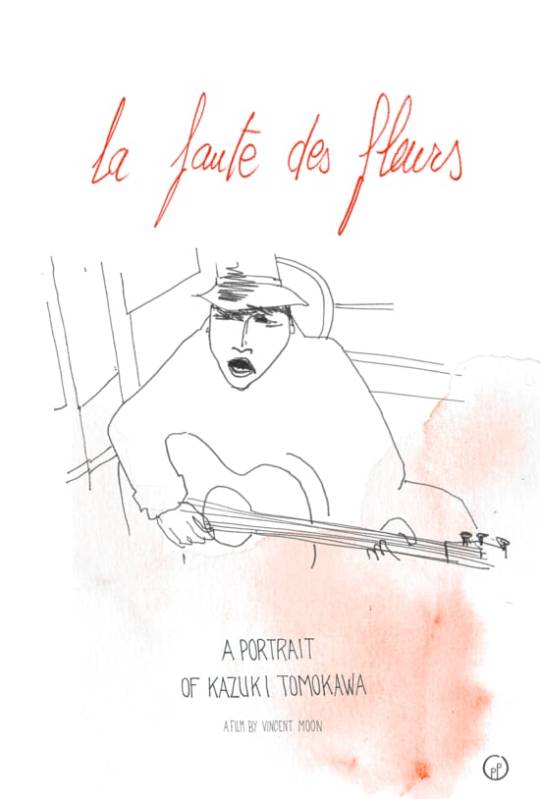

Proiezione di “La Faute des Fleurs, a portrait of Kazuki Tomokawa” (2009, di Vincent Moon)

Presso Ikigai Room via Nosadella 15 A, Bologna, 30 Maggio 2019, ore 21:30

(Proiezione gratuita riservata soci AICS 2018/19. Apertura circolo ore 18:00, inizio proiezione ore 21:30) Continua la rassegna di #Ikigai dedicate alle sottoculture del Giappone contemporaneo, con il documentario "La Faute des Fleurs" di Vincent Moon (2009), incentrato sul musicista e poeta Tomokawa Kazuki. Ancora una volta la rassegna vede incrociarsi personaggi e interpreti chiave di quella che è stata la cultura dissidente in Giappone, quali Wakamatsu Koji, Nagisa Oshima, oltre alle proteste antinucleari, la musica e il cinema d'avanguardia, il dissenso politico. "La Faute des Fleurs — a portrait of Kazuki Tomokawa 友川��ズキ" – un film di Vincent Moon Versione in giapponese con sottotitoli in inglese / 2009 / Giappone / Colore / 70min. Vincitore del Sound and Vision Award 2009 Winner al Copenhagen International Documentary Film Festival (CPH: DOX 2009) Kazuki Tomokawa: Poeta, cantante, artista, commentatore di gare ciclistiche, saggista, attore, bevitore. Un artista che incarna miracolosamente il romanticismo del poeta vagabondo, una rarità in un'epoca in cui la nostra stessa libertà significa che abbiamo dimenticato come vivere.. Nato a Hachiryu-mura (ora ribattezzato Mitane-machi), Akita nel nord del Giappone il 16 febbraio 1950, il vero nome di Tomokawa è Tenji Nozoki. Fu cresciuto dai nonni, circondato dalla natura rigogliosa del fiume Mitane che sfocia nel lago Hachiro. Durante i suoi anni alla scuola media di Ukawa, Tomokawa era uno studente particolarmente scarso e non mostrava alcun interesse per la letteratura. Tuttavia, per caso un giorno in biblioteca si imbatté nella poesia Hone (Bone) del poeta simbolista giapponese Chuya Nakahara, dell’inizio del XX secolo. Questa poesia lo scosse nel profondo, e iniziò a scrivere i suoi versi. Dopo aver lasciato la scuola media, entrò al Liceo Tecnico di Noshiro, una scuola famosa per il suo programma di pallacanestro. Mentre dirigeva la squadra di basket della scuola, iniziò a leggere molto - divorando libri del romanziere decadente Osamu Dazai e del noto critico letterario Hideo Kobayashi. (In seguito ha allenato la squadra per un po' di tempo, uno dei suoi studenti rappresenterà poi il Giappone ai Giochi Olimpici). Ispirato da Bob Dylan e altri, i primi anni '70 in Giappone videro un boom della musica popolare. Tomokawa si trovò coinvolto nel movimento, imparò a suonare la chitarra acustica e cominciò a mettere in musica le sue poesie. Nel 1975 fece il suo tanto atteso debutto discografico, pubblicando l'album Yatto Ichimaime (Finally, The First Album). In questo periodo conobbe i membri del gruppo rock radicale giapponese Zuno Keisatsu. Si trovò particolarmente bene con il percussionista del gruppo, Toshiaki Ishizuka, che sarebbe poi diventato uno dei più importanti collaboratori musicali di Tomokawa. Alla fine degli anni Settanta Tomokawa era molto impegnato con diverse compagnie teatrali, scrivendo canzoni per le loro opere teatrali e persino apparendo sul palco come attore. Questo fu un periodo in cui cercava sempre nuovi spazi in cui esprimere la sua creatività. È anche in questo periodo che si interessò per la prima volta all'arte. Tomokawa ha tenuto la sua prima mostra personale a Tokyo nel 1985, con il supporto del critico d'arte Yoshie Yoshida. Da allora ha avuto mostre in tutto il Giappone e ha attirato l'attenzione e gli elogi di artisti e opinionisti come lo scrittore outsider Kenji Nakagami e il poeta Yasuki Fukushima. Nel 1993, Tomokawa ha diede alle stampe l'album Hanabana no Kashitsu (Fault of Flowers) per la PSF Records, etichetta fino ad allora meglio conosciuta per la musica d'avanguardia e il rock psichedelico. L'album attirò molte lodi dal compositore contemporaneo Shigeaki Saegusa, e improvvisamente Tomokawa vide molti dei suoi album fuori stampa ristampati. Il rapporto tra la PSF Records e Tomokawa continua ancora oggi, producendo un flusso costante di uscite. Uno dei suoi album sotto la PSF è Maboroshi to asobu (Playing with Phantoms, 1994), che ha aperto un nuovo terreno artistico col suo incontro con musicisti di free jazz. In questo periodo, Tomokawa produsse anche una serie di libri - la raccolta di poesie Chi no banso (Earth Accompaniment), un libro illustrato, Aozora (Blue Sky, testo di Wahei Tatematsu, illustrazioni di Tomokawa), e una raccolta di saggi, Tenketsu no kaze (Wind from the Skyhole). Più recentemente Tomokawa è diventato noto come un'autorità sulle corse in bicicletta, lavorando come commentatore al canale televisivo satellitare Speed Channel, e scrivendo una rubrica di corse per un giornale serale. Le corse in bicicletta sono oggi una delle principali ossessioni di Tomokawa. Nel 2004 Tomokawa è apparso nel film Izo del regista di culto Takashi Miike, incentrato sulla figura dell'assassino del XIX secolo Izo Okada, ritraendo scene di carneficine e massacri e viaggi nel tempo. Tomokawa appare come un misterioso cantante che simboleggia i processi mentali del killer, e canta cinque canzoni nel corso del film. Tomokawa ha anche fornito la musica per il film 17 sai no fukei (Cycling Chronicles: Landscapes the Boy Saw) di Koji Wakamatsu del 2005. Da quando è passato alla PSF, Tomokawa ha continuato a pubblicare un album all'anno. La sua reputazione ha cominciato a crescere all'estero, e negli ultimi anni si è esibito in Scozia, Belgio, Svizzera, Francia e anche in Corea nell'autunno del 2009. Mentre la musica di Tomokawa è stata accolta calorosamente da artisti e appassionati di musica, ciò non significa che sia difficile da capire. Piuttosto è il risultato ironico del suo modo di vivere come artista. Con il passare degli anni, la musica e l'arte di Tomokawa sembrano diventare ancora più belle, sempre più pure, e continueranno sicuramente ad ispirare i suoi ascoltatori con il coraggio di essere se stessi. VINCENT MOON Nato a Parigi nel 1979, all'età di 18 anni Vincent decise di voler vedere tutto, di imparare le cose da solo, per curiosità, anche se questo avrebbe potuto portare alla sovralimentazione, e così per dieci anni. Da quell'esperienza sono nate le immagini, prima attraverso la fotografia, che ha studiato sotto l'influenza di Michael Ackerman e Antoine D'Agata. Qualche anno dopo, scoprendo l'opera di Peter Tscherkassky, le sue immagini acquistano movimento/mozione. Grazie a Internet ha sviluppato diversi progetti legati alla musica, dirigendo video per Clogs, Sylvain Chauveau, Barzin, The National. Nel 2006, travolto dalla bellezza di Step Across the Border, diretto da Nicolas Humbert e Werner Penzel, sul chitarrista inglese Fred Frith, ha creato con Chryde "the Take Away Shows project", il video podcast della Blogotheque (www.takeawayshows.com). Questa serie di documentari outdoor consiste in sessioni video improvvisate con musicisti, ambientate in luoghi inaspettati e trasmesse liberamente sul web. In 3 anni è riuscito a girare oltre un centinaio di clip con band come REM, Arcade Fire, Sufjan Stevens, Beirut, Grizzly Bear e molte altre. Ha perfezionato uno stile immediatamente riconoscibile di inquadrature intime, fragili, danzanti e ombreggianti, e allo stesso tempo ha cambiato l'idea di quello che dovrebbe essere un video musicale. L'intero 'concept' è stato poi esportato in tutto il mondo da molti giovani registi ispirati dal suo naturale approccio organico alla musica. Mentre lavora alle sue mostre Take Away, Vincent Moon tiene anche progetti collaterali, esplorando altri formati, sperimentando le relazioni tra immagini e suoni. Ha diretto un saggio cinematografico sulla band newyorkese The National dal titolo "A skin, A night", uscito nel maggio 2008. È stato il principale creatore del cult "Miroir Noir", un film di 76 minuti su The Arcade Fire e ha poi lavorato a stretto contatto con Michael Stipe e REM su diversi progetti video e web legati al loro ultimo album: il saggio di 48' "6 Days", un documentario gratuito sulla registrazione di "Accelerate", il progetto web sperimentale di novanta giorni chiamato "90nights" (wwww.ninetynights.com), il video e sito web unico per il singolo "Supernatural Superserious" (www.supernaturalsuperserious.com), e l'acclamato "This Is Not a Show" (co-diretto da Jeremiah, l'altro giovane regista musicale francese), un film dal vivo sulle loro performance dublinesi considerato come uno dei film live più unici di tutti i tempi. Ha pubblicato nel novembre 2007, insieme a Chryde, la fondatrice della Blogotheque, un film molto particolare con Beirut, dove tutte le 12 canzoni del suo nuovo album sono state girate per le strade di Brooklyn, in un finto esperimento one-take. (www.flyingclubcup.com) Nel tentativo di trovare nuove strade per la musica da film, prendendo le distanze dai formati mainstream e commerciali, ha girato nel 2006 un mediometraggio gonzo al Festival ATP, "Sketches from a Nightmare", il primo di una serie su questo festival, e ha partecipato attivamente al film di 90 minuti All Tomorrow's Parties, uscito nel 2009 con il plauso della critica. Nell'ottobre 2007, Warp Films lo ha assunto come regista di video musicali. Un'altra parte della sua vita è ora dedicata a lunghi ritratti su musicisti di culto e rari - realizzati con Antoine Viviani e Gaspar Claus, collaboratori di lunga data, la serie "Musicians of Our Times" (due volumi sono stati completati finora), "Little Blue Nothing" sugli Havels, una mitica coppia praghese, e "La Faute des Fleurs", spesso considerato il suo lavoro migliore, su Kazuki Tomokawa, cantante folk giapponese estremo. Links: www.lafautedesfleurs.com http://kazukitomokawa.com/

#vincent moon#kazuki tomokawa#associazione culturale ikigai#ikigai#ikigai room#documentaries#documentari#japanese music#folk#japanese folk#bologna#eventi#la faute des fleurs#wakamatsu koji#izo#takashi miike#psf records#experimental music

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#finishedbooks The Cape and Other Stories by Nakagami Kenji. Nakagami has the unique perspective of writing from Japan's little known outcaste class the burakumin...a group who still suffer from discrimination today. They originated from workers who held what society deemed unclean jobs, i.e. butchers during the Tokugawa government in the early eighteenth century. There was speculation that they originally descended from ancient slaves or were of Korean descent, but that was debunked as burakumin are racially and ethnically Japanese. The author comes from this group growing up in Shingu an area with a rather unique history that was known for treason to the central government in 1910 and is still marginalized politically-economically lying inconspicuously in between Wakayama and Mie prefecture. With that this is only one of two books he has in English translation (five in French). I actually have only heard of the writer from his screenplay of a rare film Himatsuri by Yanagimachi Mitsuo that to me was one the best Japanese films of the 80s (Juzo's The Funeral and Yoshimitsu's The Family Game as well as Typhoon Club too, etc). With that, this here is a collection of three early short stories that set up the foundation for his work. He isn't attempting to be any sort of spokesman for his people instead is an artist who describes this life with an honesty and anger that lacks self pity. His work (at least here) deals exclusively with the burakumin yet never once does he mention his characters are that or does he digress to explain a character's psychology as a burakamin. His style concerns itself more with genealogy than psychology that is rather naturalistic akin to Emile Zola. And like Zola there are quite a lot characters in his story that overlap into his other stories that objectively paint an overall picture of Shingu (for Zola it was the French Second Empire). The first two stories, "Cape" and "House on Fire" both are autobiographical dealing with an absent father and suicide of his brother and with both the father assumes something of a divine status as his work as strong element of Japanese mythology from Kojiki arriving at some shocking conclusions: here for example purification through incest, while in the film the father abruptly takes an axe to his family to achieve that. The last story, "Red Hair" is a whether graphic sexual account of a lingering one night stand that details no context as sexuality and violence with no real conclusion, something the translator relates to that late great Imamura Shohei film Vengeance is Mind that has the great reverse freeze frame angle of the of the killer ghost that carries the same themes of mythology. In all this is quite different from other Japanese writers as the drama and plight is more akin to poor families in middle American, oddly enough. A unique read...and see that film!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2023/03/19 English

BGM: Boards of Canada - Happy Cycling

Today was a day off. This morning I read Shohei Ohoka's "Seijyo Press" completely with Thievery Corporation's music. It's a journal by him at his late ages, and delivers his keen eyes to manga, music, literature, and movies with strong curiosity therefore really wonderful. I had learned about him by Mieko Kanai's essays as a really gentle, and modest person (and he also shows his great anger when he sees terrible things). The journal also shows about his that character. TBH I have not read his works so much. Just I read and was beaten by the "Fires on the Plain" that had influenced even J.G.Ballard. I might have to read Ohoka's novels... yes, I write like this but we certainly says "If you run after two hares, you will catch neither". This is autism.

Today was the day for the meeting about autism. We did it on ZOOM, and a new member joined in it. A really great time. I did a presentation about Aphorism which I had already done at another meeting. The purpose of that presentation was, of course, I wanted to share how fun the Aphorism is. But also I wanted to introduce that Shiso city has such an interesting group which has this kind of meeting. I talked about Nietzsche's dangerous and anachronic quotes, and also Gloria Steinem's cool quote "a woman without a man is like a fish without a bicycle" which was based on feminism. Other members exactly showed their interested about them so I was really glad. Indeed, it was not related with autism, but I enjoyed it. Other members' comment also gave me various things. I hope we will do this meeting at offline again.

After that meeting, I went to the library and borrowed Natsuki Ikezawa's "The Navidad Incident: The Downfall of Matias Guili". Indeed, I have read at the fall of last year, but I wanted to read again. Nowadays I am reading this kind of the books I have already read. When I was young, I had tried to read anything of Kenji Nakagami completely. But, getting older, I started thinking that I have to "enjoy" the reading and that's the meaning of it. In other words, I can never read the books I "must" read in my life... I even think that it was a certain sin if I can't enjoy reading those books. But, probably because I started choosing books to "enjoy" at the first, or maybe because I just am getting older, I started reading "classic" books. In Haruki Murakami's "Norwegian Wood", the person Nagasawa appears. He chooses reading classics and ignores new books. I have sympathy with him. I started thinking the classic books which are like milestones, which don't fade away even thought time passes,. are saying a lot to me.

I can't keep on doing just one thing steadily step by step till the end. My interest goes from here to where. A lot of things attract me so they would end incompletely. On reading, I am always attracted by various books so I read them in a "parallel" way. This evening I read Haruki Murakami's short novels and Natsuki Ikezawa's "World Literature Remix" with Boards of Canada's music. Recently I am feeling like a slump so I don't have the book which fits me. Therefore my mood goes randomly. I think that reading the collection of "Complete World Literature" which Ikezawa edited once would be valuable, so I choose the one of them, Jack Kerouac's "On The Road". TBH I have learned English literature at a university, but I have never read Kerouac's works. At this age, I read Kerouac as doing the homework of summer vacation hurriedly... that's life. Yes, it must be uncool, but an unique life.

0 notes

Text

Read Kenji Nakagami’s Remaining Flowers (1988) last night and felt the urge to know more about him… and then I see this super interesting research and a picture of him with none other than Bob Marley himself!!!

0 notes