#Jon McClenahan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

PROFILES IN HISTORY: On September 13th, 1993 Yakko, Wakko and Dot were released from the Water Tower on the Warner Bros. Lot, and into the living rooms across America, and the world. Thanks to Steven Spielberg, Tom Ruegger, Jean MacCurdy and the whole “Animaniacs” team, things haven’t quite been the same ever since! Happy Birthday guys!

#Spike Brandt#Steven Spielberg#Tom Ruegger#Jean MacCurdy#Tony Cervone#James Tucker#Jon McClenahan#Animaniacs#Warner Bros#Warner Bros Animation#StarToons#Yakko#Wakko#Dot#Rob Paulsen#Jess Harnell#Tress MacNeille#WB Lot#Warner Brothers and the Warner Sister

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

A scene i reanimated in the Smurfs episode "The Root of Evil"

This is my attempt at trying to resemble Jon McClenahan’s animation work on the second season of the 1986 version of Pound Puppies, Animaniacs and Tiny Toon Adventures. He is notable for animating at Hanna-Barbera's Australian division until 1987

The Smurfs © Peyo

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You'd think it was Jon McClenahan from the art, but nah, it's Claude Pelletier, who also did a bunch of Looney Tunes themed games.

From: Jersey Devil

255 notes

·

View notes

Text

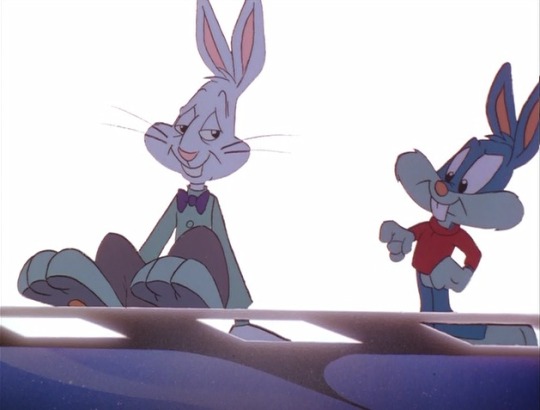

A little late, but as of yesterday (December 6th) it’s been 30 years since Tiny Toon Adventures ended its initial run with the Christmas-themed episode “It’s a Wonderful Tiny Toons Christmas”.

#tiny toon adventures#episode 98#it’s a wonderful tiny toons christmas#season 3#tom ruegger#jon mcclenahan#steven spielberg#startoons#warner bros#series finale#30th anniversary#buster bunny#babs bunny#(no relation)#plucky duck

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imagine if Bill Melendez hired Jon McClenahan to do retakes for Happy New Year, Charlie Brown to avoid repetition and add in more acting for the characters in some scenes, such as the one with Lucy and Schroeder and the part with Charlie Brown and Peppermint Patty on the phone. This would be done for future airings.

Peanuts © Charles M. Schulz/United Feature Syndicate

#charles m schulz#peanuts#what if meme#happy new year charlie brown#jon mcclenahan#1986#meme#animator#bill melendez

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animaniacs Animation Studios: StarToons

Alright, today we got the American studio.

StarToons is a funny case to me. At first, I didn’t like it much ‘cuz of how cartoony the animation was. Like I said, I thought (and still do think) TMS was more “sophisticated” while StarToons was more exaggerated. But over time, I grew to really appreciate it. (But in my defense, the earlier episodes were pretty trash ngl. :P)

The main reason why I appreciate it? Jon McClenahan.

He was the head of the studio and he always encouraged other animators to do a part. It was never just him and he never took outright control of everything, and seeing all their styles only makes me admire it more, especially when they blend together.

Helps that his style is really appealing. Broad faces and expressions (can you tell that I have a big thing for expressions lolll) that give a confident aura to the animation.

Small thing that I grew to love about his style is that Wakko’s hat bill is drawn pointing straight down.

Jeff Siergey’s style is like really liquid-y. His faces have a squishy feel which helps the animation look bouncy.

By contrast, Spike Brandt’s style is more broad (not as much as McClenahan) and more sharp. My favorite part of his is how devious he can make the kids look with the half-circle eyes.

Also, other small thing: in “Macbeth”, I love that Yakko’s ears are drawn in the same angle as he turns his head.

One animator that I’m hella sad that we didn’t get enough was David Pryor.

He joined during season 5 and you can see his work in the Macadamia Nut parody, “Magic Time”, and the “There’s Only One of You” song from “Hooray for North Hollywood Pt. 1″. His designs took inspiration from McClenahan and you can tell by like the head shape, but the more angular look makes it distinct, and I really like it.

Lastly, I want to leave Neal Sternecky as an honorable mention.

In the show, I’ve only recognized his stuff in “Chairman of the Bored” and “Macadamia”, but he’s also featured in the comics. His style is really loose and smooth (I particularly like it in “Macademia”), and I wish we saw more of it in the show.

So sad that they shut down in the same year I was born in yikes. I hope the crew’s doing alright.

Favorite Segments (in episode order)

“Chairman of the Bored” (Ep. 32)

“Ragamuffins” (Ep. 59)

“Dot - The Macadamia Nut” (Ep. 92)

“Magic Time” (Ep. 94)

Very special mention goes to “There’s Only One of You”; I know I said that songs were exempt, but since the rest of the episode is animated by Wang, I figured this was a fitting exception.

#animaniacs#animaniatag#animation#yakko wakko and dot#a!countdown#yakko warner#wakko warner#dot warner

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

FredFilms promises...

Creators first.

I've always believed that we owe you, our fans and now at FredFilms we all take it as gospel. We owe you our best work, of course. But beyond we examine everything about ourselves constantly, to assure ourselves and you that we’re trying to stay on the right track. To that end, whatever work I’ve done –whether it be in the music business, the network television business, and certainly, cartoons– has been done with making public promises that try and assure you that we’ll deliver.

To that end, I thought it would be good to print out a new set of our limited edition postcards to make the FredFilms promises completely clear. This one’s the first.

As throughout my entire cartoon career, and now at FredFilms, it’s been my mission to let exceptional creators do their thing. We’re not in the business of micro-managing our creative talent. Instead, we seek out and nurture creators who have a story they need to tell and give them as much room as possible to tell it.. We go to festivals, art schools, comedy clubs, and explore the dustiest corners of the internet to find folks we know we have to work with.

We believe there are new stories to be told.

We promise.

.....

It might seem extreme, but I thought it might be interesting to list all of the creators that have worked on my productions, starting in 1995 with What A Cartoon! at Hanna-Barbera and Cartoon Network in 1995. If you look at any of the 140 individual links (!) you’ll see that almost all of them have had estimable careers in cartoons or animation adjacent (comics, video games, VFX and the like). Some have created hit series with me, some without (sigh!) and some have become quite famous. One way or the other, they’ve all been amazing.

Raul Aguirre

Natasha Allegri

Robert Alvarez

Amy Anderson

Tex Avery

Ralph Bakshi

Joe Barbera

Damien Barchowsky

Charlie Bean

Jerry Beck

D.R. Beitzel

Mike Bell

Tim Biskup

Bob Boyle

Chris “Spike” Brandt

Eric Bryan

Michelle Bryan

David Burd

Bill Burnett

Breehn Burns

Jaime Diaz

Angelo diNallo

Kyle A. Carrozza

Elyse Castro

Tony Cervone

Alison Cowles

David Cowles

Rick Delcarmen

Jeff DeGrandis

Andrew Dickman

John R. Dilworth

Davis Doi

Greg Eagles

Jerry Eisenberg

Warren Ellis

Greg Emison

John Eng

Jun Falkenstein

David Feiss

Eddie Fitzgerald

John Fountain

Manny Galán

Dana Galin

James Giordano

Alan Goodman

Tom Gran

Mike Gray

Antoine Guilbaud

Bill Hanna

Meinert Hansen

Russ Harris

Butch Hartman

Andy Helm

Adam Henry

Bill Ho

Larry Huber

Gabe Janisz

George Johnson

Don Jurwich

Kang yo-kong

Ken Kessel

Jiwook Kim

Alex Kirwan

Kevin Kolde

Grant Kolton

Erik Knutson

Dahveed Kolodny-Nagy

Diane Kredensor

Harvey Kurtzman

Juris Lisovs

Seth MacFarlane

Steve Marmel

Miss Kelly Martin

Eugene Mattos

Craig McCracken

Jon McClenahan

John McIntyre

Harry McLaughlin

Dan Meth

Mike Milo

Zac Moncrief

Russell Mooney

Jesse Moynihan

Justin Moynihan

Adam Muto

Andre Nieves

Jeret Ochi

Joe Orrantia

Victor Ortado

Rory Panagotopulos

Paul Parducci

Van Partible

Lincoln Peirce

Jonni Phillips

Jason Plapp

Polygon Pictures

Bill Plympton

Carlos Ramos

Michael Rann

Russ Reiley

Christopher Reineman

Rob Renzetti

G. Brian Reynolds

John Reynolds

John Rice

Bill Riling

Mel Roach

Eric Robles

Mike Rosenthal

Jason Butler Rote

Jim Ryan

Fred Seibert

Seo jun-kyo

Don Shank

David Shute

Brent Sievers

Achiu So

Hamish Steele

Elizabeth Stonecypher

Jennifer Cho Suhr

Genndy Tartakovsky

Doug TenNapel

Aliki Theofilopoulos

Miles Thompson

Karl Toerge

Kate Tsang

Guy Vasilovich

Byron Vaughns

Joel Veitch

Pat Ventura

Anne Walker

Vincent Waller

Pendleton Ward

Dave Wasson

Mike Wellins

Melissa Wolfe

Martin Woolley

Jim Wyatt

Niki Yang

Carey Yost

.....

FredFilms Postcard Series 2.1

From the postcard back:

Congratulations! You are one of 75 people to receive this limited edition FredFilms postcard!

www.fredfilms.com

A FredFilms promise: Creators first.

FredFilms’ mission is to ‘put the right people in the room.’ By helping extraordinary creators we can produce innovative shows with enduring characters.

We know there a new stories to be told.

Executive producer: Fred Seibert

Series 2.1 [mailed out April 6, 2021]

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

An interview with Startoons founder Jon McClenahan from years ago:

Startoons is the Best (In My Opinion)

I’d just like to take a moment as to why I love Startoons the most out of any of the animation studios. Many people point to TMS to being the best animation studio, and while I think they are very good, I don’t think they draw the characters the best. That goes to Startoons.

Credit to @legion1979 for all of the pictures used.

First, Startoons is very stylized. Yeah, TMS has great expressions, but no one ever points out the expressions that Startoons has done.

Look at them! They have so much personality. You would never see TMS do an expression like Yakko with the NOT! sign.

Startoons has had a handful of songs, just like TMS. They’ve done, off of the top of my head, Wakko’s America, Be Careful What You Eat, Dot: The Macademia Nut, and There’s Only One of You. There’s probably more, but again, that’s just off the top of my head.

I’m gonna talk about Dot: The Macademia Nut, and that it features some of the best animation and drawings the show has ever had.

First of all, Dot. All of her outfits are on point, and the expressions and poses are amazing. Here are some pictures.

Yakko and Wakko look amazing too.

Just watching the song shows how perfect the animation is. It’s unbelievably good.

Anyway, I’d like to talk about the BAD animation. Yes, Startoons has bad animation occasionally. The Big Candy Store comes to mind.

But hey, TMS has some pretty bad animation sometimes. Taming of the Screwy has it for a majority of the episode. The Warners look very weird.

Finally, I’d like to say that Startoons improved over the course of the series. Macademia Nut came from the last season, and looks better than Wakko’s America from season one. On the other hand, I’d say TMS went down in quality instead. Cutie and the Beast has some pretty weird moments, and Wakko’s Wish also has some strange moments. The best of that movie goes to Pinky and the Brain.

Honestly, I just prefer how the Warners look in the Startoons style. I know there are different animators and boarders that still give differences in the style, you can see that, but I love all of them. I really do. Just watch Ragamuffins to see the best the show can look.

The above picture of them running is my favorite way the Warners are drawn. They look perfect.

Anyway. That’s it.

#animaniacs#animation studios#startoons#jon mcclenahan#spike brandt#they’re my 2nd favorite after tms#I do agree that startoons got better over time while tms got worse#it’s tragic how startoons was treated later on

159 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy 70th birthday Taz! June 19th, 1954 saw the release of director Robert McKimson’s “Devil May Hare,” the first Tasmanian Devil cartoon.

#Spike Brandt#Robert McKimson#Sid Marcus#Bob Givens#Tony Cervone#Jon McClenahan#Kirk Tingblad#James Tucker#Art Vitello#Doug McCarthy#Keith Baxter#Looney Tunes#Merrie Melodies#Tazmania#Warner Bros Animation#Taz#Tasmanian Devil#Bugs#Bugs Bunny#Mel Blanc

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Atomic City, USA: how once-secret Los Alamos became a millionaire’s enclave

Home to the scientists who built the nuclear bomb, the company town of Los Alamos, New Mexico is today one of the richest in the country even as toxic waste threatens its residents and neighbouring Espaola struggles with poverty

In August 1945, the US army dropped a secret over Japan: fully functional nuclear bombs, which instantly killed tens of thousands of people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. More than 6,000 miles away, meanwhile, in northern New Mexico, one newspaper carried a headline with uniquely local flair.

Now They Can be Told Aloud These Stoories[ sic] of the Hill blared a rushed edition of the Santa Fe New Mexican. The article revealed that Los Alamos a mysterious settlement, built atop a picturesque mesa had been instrumental in the process of developing these new weapons of mass destruction.

Today, Los Alamos is a secret no longer: its a small community with about 18,000 people living in the main town and a suburb called White Rock. But the nuclear lab remains, and the city is still an island in many ways: an extraordinary pocket of wealth and privilege, surrounded by some of the poorest counties in New Mexico, one of the poorest states in America.

The city is also partly toxic. The nuclear research lab still disposes of radioactive waste, and an underground plume of hexavalent chromium a contaminant linked to increased risks of cancer and constructed famous by Erin Brockovich has been drifting from the lab. A September 2016 report from the labs environmental management office said it could take more than 20 years and virtually$ 4bn( 3.3 bn) to clean up decades-old nuclear waste in the area.

And yet Los Alamos has more millionaires per capita than almost anywhere else in the country.

Instant city

The city has always been unique. During the second world war, Los Alamos was the site of a classified research laboratory, built as part of the Manhattan Project to develop an atom bomb. Along with Oak Ridge, Tennessee and Hanford, Washington, it was also home to a secret city built to house thousands of scientists, technologists and their families.

It was isolated, and it was also beautiful, which was something[ J Robert] Oppenheimer employed where reference is recruited people, says Jon Hunner, professor of history at New Mexico State University, referring to the theoretical physicist who led the Los Alamos lab.

Los Alamoss once secret nuclear history has become a tourist attraction. Photograph: Brooks Saucedo-McQuade

The goal, he explains, had been to build top secret, temporary research facilities in order to keep US nuclear scientists and their work away from prying eyes and ears.

Hunners 2007 book, Inventing Los Alamos, describes the birth of what he calls an instant city. In some routes, the story sounds similar to that of the hundreds of company towns built across the US in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries, to provide labor for single industries: mining, coal and logging towns.

Except here the industry was nuclear weapon. And, officially, the town did not exist.

Those who lived in Los Alamos were forbidden to talk about it. The town was not mentioned on drivers licenses, birth certificates, or postal mail. The whole region was surrounded by fencings, gates and guards.

Constructed virtually overnight, much of the land was simply appropriated from traditional Hispanic homesteaders and Native American communities, as well as an upper-class private sons school that counted Gore Vidal as one of its famous graduates.

To guard its secret, Los Alamos was built to be almost completely self-contained. There were schools, a hospital, and theatres that doubled as dance halls on Saturdays and churches on Sundays. Housing was allocated according to ones rank at the lab. By the end of the war, it had a population of 6,000.

Everything was run by the Army Corps of Engineers. There were no private industries in Los Alamos until the 1950 s. Nobody could own property. Nobody could own their home, says Hunner. With its focus on the social sciences behind the bomb, he describes it like a university town that was controlled by the military.

It was also shoddily constructed, he says, because it was only supposed to exist during the second world war. But then the cold war with the Soviet Union dedicated the US nuclear weapon program, and Los Alamos, a new raison detre. Both were here to stay.

Los Alamos laboratory in the 1950 s those who lived and work there had to keep it at secret. Photograph: Jeffrey Markowitz/ Sygma via Getty Images

Its a stark example of the 1% and 99%

Today Los Alamos has become one of the richest cities in America. At least one in every nine people a whopping 12% of the population is thought to be a millionaire. Los Alamos also regularly tops the listing in terms of the best education and lowest crime levels in the nation. It has one of the countrys greatest concentration of PhDs.

On the map of New Mexico, Los Alamos county created in 1949 is a tiny dot next to Rio Arriba, one of the largest counties in the nation. In Los Alamos, average incomes are twice as high as those in Rio Arriba. A 2012 Census Bureau report said this was one of the largest wealth gaps between two neighbouring counties in America.

Just 30 km from this affluent island is the town of Espaola. Here the median household income is $33,000 and virtually 30% of the population live under the poverty line. For years it has also fought with its reputation as the heroin overdose capital of America.

Hunner describes the disparity between Los Alamos and neighbouring towns as virtually inevitable. Were really a poor nation, he says. So you plop this federally supported research and development lab, where you have to pay people a lot of money to stay there, and of course theres going to be a disparity between the people who live there and the people in Espaola.

But, he adds, a lot of people who live in Espaola work in Los Alamos. In that whole northern New Mexico region, there is a big commute.

Los Alamos, where benefits have been very insular. Photograph: Brooks Saucedo-McQuade

Others insure the inequality between Los Alamos and neighbouring communities as an excellent example of a common dynamic across the country and a reminder of how narratives of wealth percolating down can be far-fetched.

Its a stark example of the proverbial 1% and the other 99%, says Jay Coghlan, sitting in a large reclining chair in the living room of his home in Santa Fe. A 45 minute drive south-east from Los Alamos, his home doubleds as an office for Nuclear Watch New Mexico.

Neighbouring communities have not benefited much at all, with the obvious exception that theres tasks, he says. Benefits have been very insular and privileged to the nuclear enclave itself.

The environmental impact of living next door to a nuclear research lab is another sore issue. Some radioactive waste is still disposed of at the labs Area G compound( although this could objective next year ), and there is still so-called legacy waste, which has not been cleaned up and will take billions of dollars to address. The carcinogenic plume of hexavalent chromium, meanwhile, which was discovered 10 years ago, is migrating towards nearby Native lands and the regional aquifer.

Atomic City, USA

Los Alamos sits on a hill at more than 7,000 ft( 2,000 metres) above sea level. The single, steep road to the town winds through picturesque northern New Mexico: arid scenery punctuated with desert plants and native American pueblos, with the Jemez mountains in the background.

On a sunny September afternoon, the town is calm and peaceful. A perfectly landscaped and manicured pond is surrounded by a park of bright green grass. A young couple pushes a newborn in a stroller.

Inside a supermarket in Los Alamos, there are fine wines on sale along with cigars, stored in a purpose-built humidor. The supermarkets indoor Atomic Bar serves a range of craft brews on tap. Nearby, a small strip mall houses a chocolatier, an acupuncturist, and a sensory deprivation flotation therapy clinic.

In the waiting room at a bank, there is a Sothebys catalogue of luxury real estate in Santa Fe, from where many of the labs better-paid employees commute. A grand new municipal building stands on the side of the main street much larger than one might expect in such a small town.

Sipping a glass of Atomic beer … Photograph: Brooks Saucedo-McQuade

But while Los Alamos is clean and orderly with clues of privilege, its affluence is comparatively understated. It doesnt looking like one of the richest counties in the nation, let alone the country.

Its not old wealth, says Heather McClenahan, executive director of the Los Alamos Historical Society. Its people who work at the lab. And if youve got two people who work at the lab, whove both got six-figure incomes, thats going to generate wealth in your family.

McClenahan has lived here for more than 15 years. Her spouse does environmental work at the lab. Its a great place to create kids, she says. Its a company town. Most households have at least one person working at the laboratory. There are fabulous schools. Its very safe.

And because its a small town, we dont have traffic problems, we dont have a lot of crime.

And yet references to war and nuclear weapon are everywhere. Atomic City Transit buses rumble down roads with names like Oppenheimer Drive and Trinity Street. Atomic City Salsa is on sale at a gift shop in the town centre, along with bumper stickers and playsuits for newborns, including one with a mushroom cloud on the front, and the punchline( Ive been falling BOMBS since Day 1) on the reverse.

Research at the lab today includes fields like climate change, supercomputing and astrophysics. But still nuclear weapon is the dominant subject.

Pete Sheehey, a Los Alamos county councillor, first moved to the town 30 years ago from California while finishing a PhD in physics. He described the community as very dependent on the one lab contract, but said that it is trying to encourage and maintain spin-off companies in the area, so there will be more jobs independent of the lab contract. And we are working to increase tourism as well.

Made in Los Alamos. Photograph: Brooks Saucedo-McQuade

Los Alamos is part of the new Manhattan Project National Park, and a new mobile app released by the lab lets users explore the 1940 s Atomic City. Already Los Alamos receives tens of thousands of guests each year to consider the place where the atom bomb was developed, says McClenahan. Some of the biggest numbers are from Russia, Germany and Japan.

McClenahan says Los Alamos has always been conflicted about the impact of the research done here. From the beginning, she says, there were scientists who were so proud of not only the scientific work they did, but of telling We ended world war two. And then there were others who said, We only killed hundreds of thousands of people.

For decades, she adds, there was also a sense of Stay out of our town, were doing top-secret run and you cant come here. But attitudes have changed. Now, she says, people are guessing: How do we bring tourists to our tiny little town?

Espaola: Its complicated

Espaola is a 25 minute drive north-east of Los Alamos. It, too, is a small town, with a population of about 10,000. But, in many respects, it feels a world away from the nuclear island on the hill.

The road into Espaola pass by brightly painted murals and drive-thru fast food restaurants. Other builds bear hand-painted signs on storefronts, selling animal feed, boots and party supplies for quinceaeras . Boldly coloured low-rider autoes, which have become key cultural symbols of this part of New Mexico, rumble down the towns wide roads.

Sheehey, the Los Alamos councillor, says that thousands of people commute to Los Alamos each day from neighbouring communities like this one. Economic benefit is felt throughout the region, he says. Children from outside the county are allowed to attend Los Alamos schools, which still get a federal subsidy and are some of the best public schools in New Mexico.

The lab has also been generous in supporting education and other community programs in Espaola and other neighbouring communities, Sheehey adds. He dedicates the example of a free bus service through northern New Mexico, funded partly by a Los Alamos county program called Progress through Partnering.

Like many people in Espaola, Patricia Trujillo, 39, says she has always been connected to the lab in some way. When we talk about the company town its much wider than Los Alamos, she says. Its the whole valley.

Two towns divided by extreme wealth and inequality. Photograph: Brooks Saucedo-McQuade

As a child in the late 1980 s, Trujillo says she recollects her teachers sending her and her classmates to wait by the side of the road and cheer as new scientific equipment was brought to Los Alamos by truck. They had us sit outside all day long, she says. Instead of getting us to question it, they had us cheering.

Her own grandmother ran in Los Alamos in the 1940 s, as a home matron in charge of a dormitory for other women who worked in the then-secret city households and offices. And Trujillo herself has worked at the lab, including as a technical novelist after university.

There are small businesses in Espaola, she says that have also benefited from subcontracts to provide supplies for the lab.

But the word Trujillo chooses to describe Espaolas relationship with Los Alamos is complicated.

Now professor of literature and Chicano surveys at Northern New Mexico College in Espaola, and head of the schools equity and diversity program, she explains: A plenty of our middle class, our wealthier parents, will drive their kids to Los Alamos county every day, to send them to school there. But then we lose that parent base here.

Trujillo says Los Alamos has supported projects including those to write science curriculum for schools in Espaola. But these efforts have been piecemeal and problematic, she says, doing little to address structural inequalities between the two communities.

There is instead a pervasive hill-valley gap, Trujillo argues, which impacts imaginations and limits people aspirations. The majority of manual labourers come from the Espaola valley … but theres no trickle down, she says. Its a multibillion dollar industry, but unfortunately theres a lot of inequity.

Secrecy , not safety

In Espaolas Valdez Park, Beata Tsosie Pea, 38, is sitting with her young son near a freshly terraced slope where she will soon assistance plant trees as part of a new community garden.

Pea was born in the nearby Santa Clara pueblo, and is coordinator of the environmental justice programme at Tewa Women United( TWU ), a civil society organisation led by indigenous women in the area( Tewa is the name of a native language group ). Trujillo is also on the board of trustees of the TWU.

Pea describes the Los Alamos lab as intertwined with issues of power and injustice from the very beginning. Much of the land for the lab was taken from Native communities in the 1940 s, in what she says started with temporary agreements, and understanding that it would be returned after the war.

Los Alamos is on all these sacred sites, ancestral sites. We knew not to develop there, to construct there. We would never have said and done, because we were put there as custodians of the water and the land, she said.

There are also concerns about the labs environmental impact on neighbouring communities. Peas organisation is part of the Communities for Clean Water alliance created to monitor Los Alamoss impact on water for drinking, agriculture, sacred ceremonies, and a sustainable future.

The September 2016 report on nuclear waste came from the the labs own environmental management office. The 20 -plus years and$ 4bn clean-up costs were criticised for being likely underestimates.

The[ labs] location was chosen for its privacy , not its safety. And now theres so much fund, its seen as an investment they dont want to lose, says Pea, wondering aloud how many of Los Alamoss residents know on whose land they are, and that the privilege of living here comes with responsibility.

But, again, the word she opts is complicated.

There needs to be a transition to a different mission[ for the lab ], to things like clean-up technologies, alternative energy, green energy, she argues. Protest groups come here and say Shut it down. But for us, its much more complicated, because our families are economically tied to the lab.

Travel for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

Read more: www.theguardian.com

The post Atomic City, USA: how once-secret Los Alamos became a millionaire’s enclave appeared first on Top Rated Solar Panels.

from Top Rated Solar Panels http://ift.tt/2nR9RN7 via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

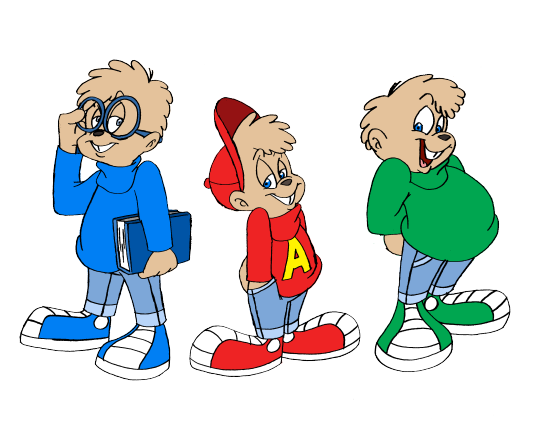

Tried my best to emulate Jon McClenahan’s art style for the Chipmunks and Dave Seville. Any artist with good experience is free to redraw these and credit me, if they have the time. Alvin and the Chipmunks is property of Bagdasarian Productions.

#alvin seville#simon seville#theodore seville#dave seville#alvin and the chipmunks#aatc#the chipmunks#jon mcclenahan#startoons#bagdasarian productions#tom ruegger#warner bros animation#amblin entertainment#steven spielberg#fanart

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

“No relation”-Babs Bunny and Buster Bunny were introduced to the world on September 14th, 1990 when “Steven Spielberg Presents ‘Tiny Toon Adventures’” premiered on CBS as a prime-time special.

#Spike Brandt#Steven Spielberg#Tom Ruegger#Jean MacCurdy#Jon McClenahan#Sherri Stoner#Tony Cervone#Kirk Tingblad#James Tucker#Neal Sternecky#Tiny Toon Adventures#WB#WB Studios#Buster#Buster Bunny#Babs#Babs Bunny#John Kassir#Charlie Adler#Tress MacNeille

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday Baby Plucky! Cel setup of Baby Plucky dealing with a plumbing emergency from “The Potty Years,” directed by Jon McClenahan. One of three shorts from the “Henny Youngman Day” episode of “Steven Spielberg Presents ‘Tiny Toon Adventures’” which first aired November 22nd, 1991. This was the first full episode that StarToons completed and I was fortunate enough to animate on this little gem of a short featuring Baby Plucky!

#Spike Brandt#Jon McClenahan#Tom Ruegger#Tony Cervone#Jeff Siergey#Steven Spielberg#Jean MacCurdy#Tiny Toon Adventures#Looney Tunes#Merrie Melodies#Warner Bros#Warner Bros Animation#Star Toons#Steven Spielberg Presents#Plucky#Plucky Duck#Nathan Ruegger#Joe Alaskey#animation artwork#animation cel

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Animaniacs” cel from “Meet Minerva” directed by Kirk Tingblad. This cel is from one of the scenes Kirk gave me to animate. When I saw it for sale a few years ago, I snapped it up.

#Spike Brandt#Kirk Tingblad#Barry Caldwell#Sherri Stoner#Dan Haskett#Jon McClenahan#Tom Ruegger#Jean MacCurdy#Steven Spielberg#Animaniacs#WB#Warner Bros Animation#StarToons#Minerva#Minerva Mink#Newt#Julie Brown#Arte Johnson#cel#animation cel

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Animaniacs” cel from “Critical Condition” directed by Jon McClenahan 1993. Slappy and Skippy give “Two Toes Up!” as their review in the final scene of this short, where Slappy exacts her revenge on Siskel and Ebert for a bad review of her cartoons. The cel, which is from a scene I animated, was signed by series producer Tom Ruegger, director Jon McClenahan, along with Tony Cervone and myself who were animators on the cartoon.

#Spike Brandt#Tony Cervone#Jon McClenahan#Tom Ruegger#Jean MacCurdy#Steven Spielberg#Animaniacs#Warner Bros#Warner Bros Animation#StarToons#Slappy#Slappy Squirrel#Skippy#Skippy Squirrel#Sherri Stoner#Nathan Ruegger#Gene Siskel#Roger Ebert#Jurassic Park#animation cel

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday to Louie and Elmo, “The Fat Cats.” Their first and only cartoon “Drip Dry Drips” directed by Jon McClenahan, was released on Cartoon Network’s “What a Cartoon!” on July 16th, 1995. Ken Hudson Campbell and Hank Azaria voiced the brothers Louie and Elmo. Tony Cervone and I created “Fat Cats” at StarToons in Chicago. It was the first cartoon that we wrote and boarded together.

#Spike Brandt#Tony Cervone#Jon McClenahan#What a Cartoon#The Fat Cats#Cartoon Network#CN#Hanna Barbera#HB#StarToons#Fat Cats#Louie#Elmo#president#Ken Hudson Campbell#Hank Azaria#Doug James#birthday#anniversary#watercolor painting

15 notes

·

View notes