#John VIII Palaiologos

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

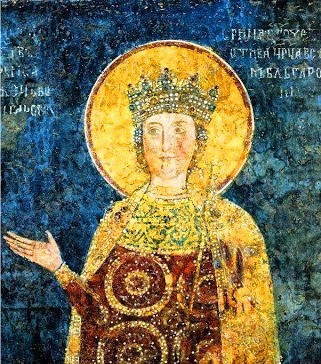

The last empress

And here is Maria of Trebizond (c.1404-1439) the last crowned Byzantine empress and wife of the penultimate emperorJohn VIII Palaiologos (and one of my favorite empresses).

I based my drawing on Bertrandon de la Broquière's account:

"He then placed the coat over her shoulders and put one of the long, pointed hats of Greece which bears along the said top three golden feathers and which fitted her very well. She seemed to me as beautiful as before. (…) She wore make up, which was unnecessary because she was young and fair-skinned. In each ear she had a hanging earring, large and flat bearing several stones, mostly rubies."

Maria was an active woman who often went hunting with her husband or alone. She rode her horse astride, something that fascinated the foreign visitors. I can't know for sure how she hunted. I chose to give her a bow as an allusion to Pisanello's depiction of her husband. Since her life was marked by many difficult events, I chose to depict her in a happy moment.

Maria was John's third wife, but also the only one that he had personally chosen (his first marriages had been marriages in name only). Her relationship with her husband was by all accounts a happy one, marked by love and respect.

The Ecthesis Chronica tells us that John loved her "beyond measure" because of her beauty and wisdom. He also valued her advice. Due to the Empire's dire situation, John left for Italy in 1438 in the hope of concluding an ecclesiastical union with the Catholic Church and thus obtaining western military aid.

Maria and her mother-in-law Helena Dragaš likely governed the capital in his absence. Maria didn't live to see her husband come back. She became ill, an event reportedly foretold by the appearance of a comet in the sky, and died on December 17, 1439.

John's entourage learned about her death during the return journey. They hid it to the emperor, fearing that his grief would delay their journey further. It was only when John returned to the capital that his mother told him the truth.

The emperor fell into a deep depression and was later buried in Maria's tomb after his death in 1448.

#maria of trebizond#niniane's drawing journey#byzantine empire#women in history#queen of cities#I really wanted to draw her because her story makes me so emotional#this was colored with a lot of patience and love#30+ minutes!#One day I will make a more detailed post about her on my sideblog#In the meantime here it is#John VIII Palaiologos

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

End of an era….

#digital art#history art#byzantium#byzantine empire#byzantine emperor#gay#pride#12th century#13th century#14th century#15th century#john ii komnenos#manuel komnenos#john iii vatatzes#michael viii palaiologos#john viii palaiologos#constantine xi palaiologos#greek tag#roman tag#empire of nicaea#nicaean empire

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

#byzantine#double headed eagle#sympilena#eagle#emblem#john viii palaiologos#emperor#palaiologos#art#history#eagles#byzantines#byzantium#byzantine empire#europe#european#roman#constantinople#romans

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The most notable players in Palaiologue politics were the empresses Yolanda-Irene of Montferrat and Anna of Savoy, and on the whole their record is woeful: Yolanda-Irene of Montferrat, second wife of Andronikos II, was unable to comprehend the succession rights of her eldest stepson, Michael IX, and since her husband remained obstinately unmoved by her representations she flounced off with her three sons to Thessalonika where she kept a separate court for many years from 1303 to her death in 1317. From her own domain she issued her own decrees, conducted her own foreign policy and plotted against her husband with the Serbs and Catalans: in mitigation, she had seen her five-year-old daughter married off to the middle-aged Serbian lecher Milutin, and considered that her eldest son John had been married beneath him to a Byzantine aristocrat, Irene Choumnaina. She died embittered and extremely wealthy.

When Yolanda’s grandson Andronikos III died early, leaving a nine-year old son John V and no arrangements for a regent, the empress Anna of Savoy assumed the regency. In so doing she provoked a civil war with her husband’s best friend John Kantakouzenos, and devastated the empire financially, bringing it to bankruptcy and pawning the crown jewels to Venice, as well as employing Turkish mercenaries and, it appears, offering to have her son convert to the church of Rome. Gregoras specifically blames her for the civil war, though he admits that she should not be criticised too heavily since she was a woman and a foreigner. Her mismanagement was not compensated for by her later negotiations in 1351 between John VI Kantakouzenos and her son in Thessalonika, who was planning a rebellion with the help of Stephen Dushan of Serbia. In 1351 Anna too settled in Thessalonika and reigned over it as her own portion of the empire until her death in c. 1365, even minting her own coinage.

These women were powerful and domineering ladies par excellence, but with the proviso that their political influence was virtually minimal. Despite their outspokenness and love of dominion they were not successful politicians: Anna of Savoy, the only one in whose hands government was placed, was compared to a weaver’s shuttle that ripped the purple cloth of empire. But there were of course exceptions. Civil wars ensured that not all empresses were foreigners and more than one woman of Byzantine descent reached the throne and was given quasi-imperial functions by her husband.

Theodora Doukaina Komnene Palaiologina, wife of Michael VIII, herself had imperial connections as the great-niece of John III Vatatzes, and issued acts concerning disputes over monastic properties during her husband’s reign, even addressing the emperor’s officials on occasion and confirming her husband’s decisions. Nevertheless, unlike other women of Michael’s family who went into exile over the issue, she was forced to support her husband’s policy of church union with Rome, a stance which she seems to have spent the rest of her life regretting. She was also humiliated when he wished to divorce her to marry Constance-Anna of Hohenstaufen, the widow of John III Vatatzes.

Another supportive empress consort can be seen in Irene Kantakouzene Asenina, whose martial spirit came to the fore during the civil war against Anna of Savoy and the Palaiologue ‘faction’. Irene in 1342 was put in charge of Didymoteichos by her husband John VI Kantakouzenos; she also organised the defence of Constantinople against the Genoese in April 1348 and against John Palaiologos in March 1353, being one of the very few Byzantine empresses who took command in military affairs. But like Theodora, Irene seems to have conformed to her husband’s wishes in matters of policy and agreed with his decisions concerning the exclusion of their sons from the succession and their eventual abdication in 1354.

Irene and her daughter Helena Kantakouzene, wife of John V Palaiologos, were both torn by conflicting loyalties between different family members, and Helena in particular was forced to mediate between her ineffectual husband and the ambitions of her son and grandson. She is supposed to have organised the escape of her husband and two younger sons from prison in 1379 and was promptly taken hostage with her father and two sisters by her eldest son Andronikos IV and imprisoned until 1381; her release was celebrated with popular rejoicing in the capital. According to Demetrios Kydones she was involved in political life under both her husband and son, Manuel II, but her main role was in mediating between the different members of her family.

In a final success story, the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, owed his throne to his mother. The Serbian princess Helena Dragash, wife of Manuel II Palaiologos, in the last legitimating political manoeuvre by a Byzantine empress, successfully managed to keep the throne for her son Constantine and fend off the claims of his brother Demetrios. She arranged for Constantine’s proclamation as emperor in the Peloponnese and asserted her right to act as regent until his arrival in the capital from Mistra in 1449.

Despite the general lack of opportunity for them to play a role in politics, Palaiologue imperial women in the thirteenth century found outlets for their independent spirit and considerable financial resources in other ways. They were noted for their foundation or restoration of monastic establishments and for their patronage of the arts. Theodora Palaiologina restored the foundation of Constantine Lips as a convent for fifty nuns, with a small hospital for laywomen attached, as well as refounding a smaller convent of Sts Kosmas and Damian. She was also an active patron of the arts, commissioning the production of manuscripts like Theodora Raoulaina, her husband’s niece. Her typikon displays the pride she felt in her family and position, an attitude typically found amongst aristocratic women.

Clearly, like empresses prior to 1204, she had considerable wealth in her own hands both as empress and dowager. She had been granted the island of Kos as her private property by Michael, while she had also inherited land from her family and been given properties by her son Andronikos. Other women of the family also display the power of conspicuous spending: Theodora Raoulaina used her money to refound St Andrew of Crete as a convent where she pursued her scholarly interests.

Theodora Palaiologina Angelina Kantakouzene, John Kantakouzenos’s mother, was arguably the richest woman of the period and financed Andronikos III’s bid for power in the civil war against his grandfather. Irene Choumnaina Palaiologina, in name at least an empress, who had been married to Andronikos II’s son John and widowed at sixteen, used her immense wealth, against the wishes of her parents, to rebuild the convent of Philanthropes Soter, where she championed the cause of ‘orthodoxy’ against Gregory Palamas and his hesychast followers. Helena Kantakouzene, too, wife of John V, was a patron of the arts. She had been classically educated and was the benefactor of scholars, notably of Demetrios Kydones who dedicated to her a translation of one of the works of St Augustine.

The woman who actually holds power in this period, Anna of Savoy, does her sex little credit: like Yolanda she appears to have been both headstrong and greedy, and, still worse, incompetent. In contrast, empresses such as Irene Kantakouzene Asenina reflect the abilities of their predecessors: they were educated to be managers, possessed of great resources, patrons of art and monastic foundations, and, given the right circumstances, capable of significant political involvement in religious controversies and the running of the empire. Unfortunately they generally had to show their competence in opposition to official state positions. While they may have wished to emulate earlier regent empresses, they were not given the chance: the women who, proud of their class and family, played a public and influential part in the running of the empire belonged to an earlier age."

Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium AD 527-1204, Lynda Garland

#history#women in history#historyedit#queens#empresses#byzantine empire#byzantine history#medieval women#13th century#14th century#15th century#historyblr#historical figures#byzantine empresses#irene of montferrat#anna of savoy#helena dragas#Theodora Doukaina Komnene Palaiologina#Irene Kantakouzene Asenina#Helena Kantakouzene

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! This might sound weird but i was curious to know if you think that Vlad was more sympathetic in private. For example when he is with his wife or something.

I think he was but in the medieval rulers style, What matters the most to them is their goal and legacy, Anything else is just background noise. Gotta remember that Vlad had countless opportunities to "retire" with his family and become a relaxed high ranking noble/general and spend all his life in pleasure and riches, but from a young age to middle-age always pursed the throne, no matter what or in what conditions. So I believe he enjoyed his time with his family but he got it pretty rare and didn't mind that much. I remember when Vlad Dracul lost the throne and found shelter at John VIII Palaiologos and he wrote about him "When he had free time he spent it with top ranking soldiers and with people good at revolts and war" So It was normal to dedicate all your life to the throne.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wives and Daughters of Byzantine Emperors: Ages at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list.

Theodora, wife of Justinian I; age 35 when she married Justinian in 435 AD

Constantina, wife of Maurice; age 22 when she married Maurice in 582 AD

Eudokia, wife of Heraclius; age 30 when she married Heraclius in 610 AD

Fausta, wife of Constans II; age 12 when she married Constans in 642 AD

Maria of Amnia, wife of Constantine VI; age 18 when she married Constantine in 788 AD

Theodote, wife of Constantine VI; age 15 when she married Constantine in 795 AD

Euphrosyne, wife of Michael II; age 33 when she married Michael in 823 AD

Theodora, wife of Theophilos; age 15 when she married Theophilos in 830 AD

Eudokia Dekapolitissa, wife of Michael III; age 15 when she married Michael in 855 AD

Eudokia Ingerina, wife of Basil I; age 25 when she married Basil in 865 CE

Theophano Martinakia, wife of Leo VI; age 16/17 when she married Leo in 882/883 AD

Helena Lekapene, wife of Constantine VII; age 9 when she married Constantine in 919 AD

Theodora, wife of John I Tzimiskes; age 25 when she married John in 971 AD

Theophano, wife of Romanos II (and later Nikephoros II); age 14 when she married Romanos in 955 AD

Anna Porphyrogenita, daughter of Romanos II; age 27 when she married Vladimir in 990 AD

Zoe Porphyrogenita, wife of Romanos III (and later Michael IV & Constantine IX); age 50 when she married Romanos in 1028 AD

Eudokia Makrembolitissa, wife of Constantine X Doukas (and later Romanos IV Diogenes); age 19 when she married Constantine in 1049 AD

Maria of Alania, wife of Michael II Doukas (and later Nikephoros III Botaniates); age 12 when she married Michael in 1065 AD

Irene Doukaina, wife of Alexios I Komnenos; age 11 when she married Alexios in 1078 AD

Anna Komnene, wife of Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger; age 14 when she married Nikephoros in 1097 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Alexios I Komnenos; age 14/15 when she married Nikephoros Katakalon in 1099/1100 AD

Eudokia Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Michael Iasites in 1109 AD

Theodora Komnene, daughter of Alexios Komnenos; age 15 when she married Constantine Kourtikes in 1111 AD

Maria of Antioch, wife of Manuel I Komnenos; age 16 when she married Manuel in 1161 AD

Euphrosyne Doukaina Kamatera, wife of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Alexios in 1169 AD

Maria Komnene, daughter of Manuel I Komnenos; age 27 when she married Renier of Montferrat in 1179 AD

Anna of France, wife of Alexios II Komnenos (and later Andronikos Komnenos); age 9 when she married Alexios in 1180 AD

Eudokia Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 13 when she married Stefan Nemanjic in 1186 AD

Margaret of Hungary, wife of Isaac II Angelos; age 11 when she married Isaac in 1186 AD

Anna Komnene Angelina, daughter of Alexios III Angelos; age 14 when she married Isaac Komnenos Vatatzes in 1190 AD

Irene Angelina, daughter of Isaac II Angelos; age 16 when she married Philip of Swabia in 1197 AD

Philippa of Armenia, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 31 when she married Theodore in 1214 AD

Maria of Courtenay, wife of Theodore I Laskaris; age 15 when she married Theodore in 1219 AD

Maria Laskarina, daughter of Theodore I Laskaris; age 12 when she married Bela IV of Hungary in 1218 AD

Elena Asenina of Bulgaria, wife of Theodore II Laskaris; age 11 when she married Theodore in 1235 AD

Anna of Hohenstaufen, wife of John III Doukas Vatatzes; age 14 when she married John in 1244 AD

Theodora Palaiologina, wife of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Michael in 1253 AD

Anna of Hungary, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 13 when she married Andronikos in 1273 AD

Eudokia Palaiologina, daughter of Michael VIII Palaiologos; age 17 when she married John II Megas Komnenos in 1282 AD

Irene of Montferrat, wife of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 10 when she married Andronikos in 1284 AD

Rita of Armenia, wife of Michael IX Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Michael in 1294 AD

Simonis Palaiologos, daughter of Andronikos II Palaiologos; age 5 when she married Stefan Milutin in 1299 AD

Irene of Brunswick, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 25 when she married Andronikos in 1318 AD

Anna of Savoy, wife of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Andronikos in 1326 AD

Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Basil of Trebizond in 1335 AD

Maria-Irene Palaiologina, daughter of Andronikos III Palaiologos; age 9 when she married Michael Asen IV of Bulgaria in 1336 AD

Theodora Kantakouzene, daughter of John VI Palaiologos; age 16 when she married Orhan Gazi in 1346 AD

Helena Kantakouzene, wife of John V Palaiologos; age 13 when she married John in 1347 AD

Keratsa of Bulgaria, wife of Andronikos IV Palaiologos; age 14 when she married Andronikos in 1362 AD

Helena Dragas, wife of Manuel II Palaiologos; age 20 when she married Manuel in 1392 AD

Anna of Moscow, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 21 when she married John in 1414 AD

Maria Komnene, wife of John VIII Palaiologos; age 23 when she married John in 1427 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Theodore II Palaiologos; age 14 when she married John II of Cyprus in 1442 AD

Helena Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 15 when she married Lazar Brankovic in 1446 AD

Sophia Palaiologina, daughter of Thomas Palaiologos; age 23 when she married Ivan III of Russia in 1472 AD

The average age at first marriage was 17 years old.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos (Iōánnēs Palaiológos), German emperor Sigmund (Sigismund) and King Eric the Pomeranian (Erik) of Scandinavia, meeting in Buda, 1424

I wish I could find a higher res image of this, supposedly this is in the Louvre but I can’t find it in their digital collections

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 6.18 (before 1940)

618 – Li Yuan becomes Emperor Gaozu of Tang, initiating three centuries of Tang dynasty rule over China. 656 – Ali becomes Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate. 860 – Byzantine–Rus' War: A fleet of about 200 Rus' vessels sails into the Bosphorus and starts pillaging the suburbs of the Byzantine capital Constantinople. 1053 – Battle of Civitate: Three thousand Norman horsemen of Count Humphrey rout the troops of Pope Leo IX. 1264 – The Parliament of Ireland meets at Castledermot in County Kildare, the first definitively known meeting of this Irish legislature. 1265 – A draft Byzantine–Venetian treaty is concluded between Venetian envoys and Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, but is not ratified by Doge Reniero Zeno. 1391 – Tokhtamysh–Timur war: Battle of the Kondurcha River: Timur defeats Tokhtamysh of the Golden Horde in present-day southeast Russia. 1429 – Charles VII's army defeats an English army under John Talbot at the Battle of Patay during the Hundred Years' War. The English lost 2,200 men, over half their army, crippling their efforts during this segment of the war. 1633 – Charles I is crowned King of Scots at St Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh. 1684 – The charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony is revoked via a scire facias writ issued by an English court. 1757 – Battle of Kolín between Prussian forces under Frederick the Great and an Austrian army under the command of Field Marshal Count Leopold Joseph von Daun in the Seven Years' War. 1778 – American Revolutionary War: The British Army abandons Philadelphia. 1799 – Action of 18 June 1799: A frigate squadron under Rear-admiral Jean-Baptiste Perrée is captured by the British fleet under Lord Keith. 1803 – Haitian Revolution: The Royal Navy led by Rear-Admiral John Thomas Duckworth commence the blockade of Saint-Domingue against French forces. 1812 – The United States declaration of war upon the United Kingdom is signed by President James Madison, beginning the War of 1812. 1815 – Napoleonic Wars: The Battle of Waterloo results in the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte by the Duke of Wellington and Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher forcing him to abdicate the throne of France for the second and last time. 1822 – Konstantinos Kanaris blows up the Ottoman navy's flagship at Chios, killing the Kapudan Pasha Nasuhzade Ali Pasha. 1858 – Charles Darwin receives a paper from Alfred Russel Wallace that includes nearly identical conclusions about evolution as Darwin's own, prompting Darwin to publish his theory. 1859 – First ascent of Aletschhorn, second summit of the Bernese Alps. 1873 – Susan B. Anthony is fined $100 for attempting to vote in the 1872 presidential election. 1887 – The Reinsurance Treaty between Germany and Russia is signed. 1900 – Empress Dowager Cixi of China orders all foreigners killed, including foreign diplomats and their families. 1908 – Japanese immigration to Brazil begins when 781 people arrive in Santos aboard the ship Kasato-Maru. 1908 – The University of the Philippines is established. 1920 – The Troubles in Northern Ireland (1920–1922) begin with a week of sectarian violence in Derry. 1928 – Aviator Amelia Earhart becomes the first woman to fly in an aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean (she is a passenger; Wilmer Stultz is the pilot and Lou Gordon the mechanic). 1935 – Police in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, clash with striking longshoremen, resulting in a total of 60 injuries and 24 arrests.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Irene Doukaina Laskarina was empress consort of Bulgaria (1258–1268). She was the second wife of Tsar Constantine Tikh of Bulgaria.

She was a daughter of Emperor Theodore II Laskaris of Nicaea, and his wife Elena of Bulgaria, and sister of Nicaean Emperor John IV Laskaris. Her maternal grandparents were Tsar Ivan Asen II and Anna Maria of Hungary.

In 1257, Irene married Bulgarian nobleman Constantine Tikh as his second wife. Her husband was a pretender to the Bulgarian crown. Constantine was proud to be married to a granddaughter of Tsar Ivan Asen II, and he adopted the Bulgarian dynastic name Asen to enhance his claim to the crown. In the next year Constantine was elected Tsar of Bulgaria by a boyar council in Tarnovo and Irene become his consort.

In 1261 Irene's young brother, Emperor John IV Laskaris, was deposed and blinded by Nicaean regent Michael VIII Palaiologos, who had just regained Constantinople from the Latin Empire, re-establishing the Byzantine Empire. Tsaritsa Irene was a bitter enemy of the usurper. She became a leader of the anti-Byzantine party in the Bulgarian court.

Irene died in 1268. She had no children.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mirrors for princes - Wikipedia

Byzantine texts

edit

See also: Basilikos logos

Synesius, Bishop of Cyrene, De regno, speech delivered to emperor Arcadius.

Agapetus the deacon, speech delivered to emperor Justinian I. (c. 530s)

Basil I the Macedonian, Admonitory chapters I and II to his son emperor Leo VI the Wise

Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos, De Administrando Imperio, a domestic and foreign policy manual for the use of Constantine's son and successor, the Emperor Romanos II. (948–952)

Kekaumenos, Strategikon (1075/1078), chapters 77 – 91.

Archbishop Theophylact of Ohrid, Paideia Basilike (Lat. Institutio Regia) (c. 1088), addressed to his pupil Constantine Doukas, son of Emperor Michael VII Doukas.

Spaneas or Didaskalia Parainetike, modelled on the Isocratean Ad Demonicum (12th century)

Nikephoros Blemmydes, Andrias Basilikos (Lat. Regia statua, "Statue of a King"), written for Theodore II Laskaris, the future Nicaean emperor (c. 1250)

Thomas Magistros, La regalita addressed to Andronikos II Palaiologos. (14th century)

Manuel II Palaiologos, Paideia Regia dedicated to his son, John VIII Palaiologos. (15th century)

PORTIEUX

0 notes

Photo

~ “When the Byzantine emperor John VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus - born in Constantinople on December 18, 1392 - entered Florence, the population was amazed, fascinated by his way of dressing. It is said that Giovanni conditioned Florentine fashion for over a century, despite not being loved by the population, who considered him a malevolent and sarcastic person, simply because of his Byzantine origin. It was depicted in 1459 by Benozzo Gozzoli in the Adoration of the Magi, the famous cycle of frescoes housed in Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence and which was the pretext to represent the procession with Pope Pius II Piccolomini and the numerous personalities following him, who he arrived in Florence in April 1458, headed for Mantua.“ ~

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why did he blind people that he now ruled over that he conquered? “Michael VIII Palaiologos, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea, took Constantinople, promptly burned the Venetian quarter and re-established the Byzantine Empire. Captured Venetian citizens were blinded”

Michael was fond of blinding those he wanted to get rid of. He blinded his predecessor John IV and stuck him in a monastery. Some monarchs stick to the same record.

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Late Byzantine naturalism: Hagia Sophia’s Deësis mosaic Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, responsible for reclaiming the Byzantine capital, is likely responsible for installing a monumental new mosaic of the Deësis in the south gallery of Hagia Sophia—a part of the church traditionally reserved for imperial use—not long after reclaiming Constantinople in 1261. The monumental Deësis mosaic depicts Christ flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist approximately two and a half times larger than life. The looming stature of these three figures reflects their importance in Byzantine culture. Christ, the Son of God, appears at the center of the composition and is labeled, IC XC, the Greek abbreviation for “Jesus Christ.” The Byzantines viewed the Virgin Mary—Christ’s mother—as a powerful protector. She appears at Christ’s right hand and is labeled, MP ΘY, “Mother of God.” John was a prophet and relative of Christ, whose preaching and baptizing prepared the way for Christ’s ministry in the Gospels. He appears on Christ’s left with the label, “Saint John the Forerunner.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

House of Hohenstaufen & Byzantine Imperial Family: Konstanze “Anna” of Hohenstaufen

Konstanze was born as the daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and his mistress Bianca Lancia. Matthew of Paris reports that Frederick married his mistress on her deathbed and thereby legitimized his children by her. The church never noted this marriage down but Frederick did definitely consider his children by Bianca as legitimate since he treated them like they were. Konstanze’s brother became the heir to the Italian throne and she was promised to the Nicaen Emperor.

In 1244, Konstanze was married to Byzantine Emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes of Nicaea. She was 14 while he was 52. This marriage, unsurprisingly, was not very happy. Konstanze, who as tradition demanded had taken a new name and was now called Anna, was soon replaced in all but name by a young mistress. The mistress’ name is unknown but it is speculated that she actually belonged to Anna’s ladies-in-waiting. At the same time, Konstanze’s father was facing issues because of this marriage. The Pope was extremely against Konstanze marrying the Byzantine Emperor and even went so far to try to replace the Holy Roman Emperor with a candidate of his own choosing.

Konstanze became a widow on November 3rd, 1254, when she was in her mid-twenties. Her father had no intervened in her marriage since he needed Byzantine Empire’s military and financial support. She was completely isolated at court even after her husband’s death. The Byzantines viewed her as a hostage to pressure the House of Hohenstaufen into doing their biding. It would take another seven years until John’s son by Irene Laskarina, who was a sister of Eudokia Laskarina, The Hereditary Duchess of Austria, died and his son was forced from his position and Konstanze’s situation changed.

The new Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos fell in love with the now 31-year-old Konstanze. Michael asked for a divorce from his wife Theodora. It is uncertain whether Konstanze was also interested in him or was even his mistress at the time, she might have even been against the match herself. However the match was never made since the privy council and the Patriarch of Constantinople turned the proposal down.

In 1262, King Manfred of Sicily, Konstanze’s brother, received the captive Alexios Strategopoulos from his second wife’s brother Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas. Three years later, Manfred successfully randsomed hin for his sister Konstanze who now went to South Italy. Only a year later, Manfred was killed in battle and most of her family was captured by Charles I of Anjou. However, Konstanze was one of the few people who were able to flee in time. She went to her niece who was married to the future king Peter III of Aragon and was also the Hohenstaufen heiress to Italy after her father’s death.

Konstanze remained for a short time at the court of her niece of the same name before she decided to retire to a monastery in Valencia. She spent the rest of her life as a nun. Konstanze died at the age of 66 or 67 in April of the year 1307. Her wooden casket is stored inside the church of San Juan del Hospital in Valencia until this very day.

// Ece Çeşmioğlu in Magnificent Century: Kösem (2015-17)

#historyedit#women in history#historic women#Middle Ages#1200s#13th century#Byzantine Empire#Holy Roman Empire#House of Hohenstaufen#Konstanze of Hohenstaufen#Empress Anna of Nicaea#German history#European history

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Marble Emperor

**DISCLAIMER: This short story was originally written back in 2014 for a college writing class.**

*May 28th, 1453*

Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI Dragaš Palaiologos knelt on the cold marble floor of the Hagia Sophia, the church at the center of Constantinople, with his head bowed and his eyes closed in prayer.

“To surrender the city to you is beyond my authority or anyone else's who lives in it, for all of us, after taking the mutual decision, shall die out of free will without sparing our lives,” he had growled as he threw the Turkish delegation out.

His father Manuel II, his mother Helena, and his older brother John VIII had prepared Constantine his entire life for the possibility that the Ottomans would one day try to destroy the Empire. (If they were here, they would know what to do, he thought solemnly.) Their stories of the centuries of Muslim atrocities against Christians horrified him as a child. And he suffered a bitter military loss when the Turks drove his armies from an attempted conquest of Athens back to Corinth in 1446. Therefore, from the moment he took the throne in 1449, he undertook to strengthen the city and spill their blood fighting for it. But now those very words of defiance came back to bite him like vipers that now hissed with the accusation, What empire is there left to destroy? What empire indeed? The Byzantines were the eastern, Greek speaking descendants of the Roman Empire, which once had uncontested dominion from Britain to Persia. After ten centuries of weathering attacks from barbarians, Muslims, and Christians alike, however, the Byzantines now only ruled a small portion of the southernmost part of Greece called the Despotate of the Morea (astride what used to be Sparta), a handful of Aegean islands, and the immediate environs of Constantinople.

And yet, Constantine reflected, he was not truly alone in this fight. Kneeling in prayer beside him was Giovanni Gustiniani. Constantine had joked to Giovanni during a rare break in the siege that he was the only good man to ever come out of Genoa. But it was true. The Italian had sailed to Constantinople’s aid with seven hundred Genoese mercenaries. But far more importantly, he quickly became Constantine’s protostrator (or second in command) and made sure the ragtag Byzantine, Genoese, and Venetian soldiers remained unified and could effectively defend the walls. Without his help, the city would not have held out for as long as it had so far.

Right now, though, Giovanni looked worried as he turned to Constantine. Constantine did his best to not show the fear that this look caused to spread through his whole body. If Giovanni was nervous, then surely something must be wrong. But Constantine dared not show his trepidation. He certainly could not afford to appear weak in front of the throng of thousands of civilian refugees who had been praying with them. They now took shelter in the center of this cathedral that remained strong for them and that housed the priests who fed them with meager stores of bread, even as paint from the mosaics peeled off and critical masonry in the walls started to show cracks and strain. It seemed to the Emperor that his subjects were also barely holding themselves together, especially recently.

On the night of May 22nd, when the Moon rose, it was partially eclipsed by the Earth's shadow and its light glowed red like blood. This already caused enough panic for Constantine and what remained of his government in a city that had been besieged for a month to have to deal with. To make things worse, rumors flew around that there was a prophecy that the city would fall after a blood moon. Then four days later, the entire city was blanketed by a large, thick, and choking cloud of black fog. When the fog lifted, there appeared around the dome of the Hagia Sophia a strange multicolored light, which some hoped came from the fires of foreign armies come to relieve the city. Most, however, despaired, wailing throughout the crumbling streets that the Holy Spirit had abandoned the capital to the heathens.

Under these circumstances, Constantine could not blame anyone for panicking. He almost envied that they were able to scream.

"Is there something that troubles you, my friend?" he asked calmly, placing a large, weary hand on the Italian captain's shoulder.

"I don't know quite how to say this, my lord..."

"Please. We have known each other long enough, Giovanni. It is Constantine."

"Alright- Constantine," Giovanni stammered quietly, hoping that he wasn't disturbing the Latin and Greek churchmen and the Imperial nobility who sat immediately behind him as the service continued. "I am afraid I must beg leave to attend to the walls. It appears that the Turks are concentrating their cannon fire on the Blachernae." These were the most weakened walls, and were situated in the northwest of the city.

“I will excuse you and ask for God's forgiveness on your behalf if He should be offended by this," Constantine nodded.

As Giovanni attempted to slink towards the exit without arousing the panic of the commoners or the offended huffs of the churchmen, Constantine wished that he could leave. He was, of course, a very devout Christian, and it was important that the Emperor remain implacably, solemnly beseeching of God's mercy at a time like this. But now he could very well feel the weight of the sword on his right hip and the shield leaning on his left arm, and he knew they would soon be needed.

*****

*Rumeli Hisari, Ottoman Fortress Just North of Constantinople*

"Are you sure that it will not break this time?" Sultan Mehmed shouted at Orban the Dacian, his Hungarian gunsmith. He did this not out of any anger towards the other man, but simply in order for his words to be heard over the constant gunfire.

"Yes, my lord," Orban bowed. "I have made several small but important improvements to the design since the last time we fired it."

"Excellent, my friend," Mehmed replied.

However, the Sultan made a careful mental note to keep an eye on Orban. He had initially offered to work for the Byzantines. It was only because his asking price was too high and because the Byzantines did not have the resources necessary for what he was asking to create them that he had changed sides, and that would pose a problem.

“When will it be ready?"

Orban's blond mustache trembled before he said, "I- I have the full team of sixty oxen and four hundred men rolling it into position in front of the fort even as we speak."

"Good," Mehmed smiled, something which Orban had rarely seen.

Orban then enthusiastically cried, "I will go down there and personally make sure that it is aimed and fired properly. Where would you like me to aim it?"

"See how the other cannons are concentrating their fire at the northwest corner?" Mehmed asked and then pointed.

Orban nodded and immediately rushed down and made preparations to fire upon the Blachernae. At whatever price his loyalty may have been bought to start with, with that gesture Mehmed was now confident that Orban would remain on his side.

When he came to the throne two years earlier after the death of his father, Sultan Murad II, no one would have ever thought that Mehmed, then only nineteen, would ever inspire any kind of loyalty or do anything great. Even Mehmed himself had not been confident in himself when he took the throne.

He had done it before, ruling for a short time when his father abdicated in 1444. But he was only twelve at the time. Frustrated when his teachers assumed he could not do anything competently, took power out from under him, and then nearly ran the entire nation into the ground, Mehmed had had to supplicate his father to return to the throne and resented being lectured by the old fool afterwards. Thereafter father and son bitterly resented each other.

Mehmed had not wanted to have to go through it all again, and almost cursed Allah for taking his father away and making him do this.

But as his father lay dying in 1451, he had summoned young Mehmed into his chambers and had him sit beside him on the bed and read from one of the hadiths, a report of the deeds and sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him). In it he said, "Verily you shall conquer Constantinople. What a wonderful leader will he be, and what a wonderful army will that army be!"

"I know that you can do what I could not, my son," Sultan Murad coughed, and then closed his eyes and drifted into Paradise.

His teacher Ak Şemseddin had drilled into him from the moment he could read that it was his Islamic duty to capture Constantinople. And now, as he wept for the loss of his father, Mehmed was reminded of that. He knew what his first act in office must be, and knew that the Christian and Muslim enemies that surrounded him would never take him seriously unless he did this. Therefore, from the moment he had taken the throne, Mehmed prepared his armies to crush Constantinople. In doing so, he would succeed where Muslim armies had failed since 678. In the process he would eliminate a small but annoying foe in the middle of his country, establish for it a natural capital, and turn his Sultanate into an heir to the glory of Rome herself.

Of course, since he was a reasonable man, he had first offered a way for Byzantine "Emperor" Constantine to step down without bloodshed. He didn’t expect Constantine would *agree*, but all this blood was now on the Greek.

"Fire!" the Sultan cried once Orban had positioned the cannon correctly. It was now midnight on the morning of May 29th, and the Sultan now prayed that this would mark the final assault that would deliver the city to himself, his people, and to Allah.

No sooner had the fuse been lit then the hiss and pop of the fire dancing on the edges of the rope that fed itself into the monstrous bronze beast echoed within its cavernous belly. To some who were on the ground, it was almost was as if this cannon, which was heavier than several ships put together, was an unholy djinn taking a deep inhalation before breathing out terrible fire upon its enemies. And when it belched its black smoke, wheels taller than two men standing on top of one another nearly buckled from the recoil as the ball sailed across the Golden Horn, the small inlet that formed the northern boundary of Constantinople.

Several soldiers immediately noticed another loud bang emerge from the metal dragon. But none of them remembered loading and firing it at all, which seemed odd. One went to take a closer look. By the time he heard another angry shout emerging from the cracks, however, an enraged fireball devoured him and spat out only ash in its wake. The frightened rabbits ran for their lives but it was already too late. Mehmed could not bear to watch the carnage below him. When the bloated weapon finally shuddered and died, he despaired to learn that was left of Orban had been incinerated in the blast and crushed by falling pieces of bronze as well.

Struggling to keep away tears so as not to panic those men who still lived and were dealing with the horror of seeing their mangled comrades, the Sultan's eyes followed the cannonball for a moment before he knelt on the fortress's walls and made this solemn prayer.

"Allah, if it be your will, bring Orban into Paradise and let his death not have been in vain. Bless our endeavor this night and deliver Constantinople unto us."

"What will you have me do, my lord?" the Commander of the Janissaries, the Empire's brave, elite soldiers, asked the Sultan.

"Assemble every man you have and prepare to attack!"

*****

"All of you, get away from the walls and take cover!" Giovanni cried. He was at the front of the line, waving with his sword and banging his shield to get the attention of those who were still manning the Blachernae guard posts at that moment.

Most saw his message and tried to escape by leaping away from the towers and onto piles of hay below. This did not work at all, but fortunately, when compared to those who were caught on the walls when the cannonball slammed into them, their deaths were swift and painless.

Giovanni squinted as his entire body and his suit of armor was coated in a thin layer of powdered limestone from the hole that had been punched through the city's defenses. And worse, mere moments seemed to pass before a horde of howling Turks streamed through the walls, seemingly endless. And not just any Turks.

Janissaries.

Brutal, merciless, and born only to kill and maim, these monstrous, gnarled mercenaries drove fear into the hearts of the defenders.

"Stand your ground!" Giovanni yelled. "For we will fight and die honorably and on our feet, as our Roman forefathers did before us!"

He did not get to say much more before a river of Turkish shields slammed against his own. The Italian leaned his shoulder into his shield to push back against them and stabbed his foes through whatever hole in their guard he could find, coating the cobblestones generously with their blood.

Just as Giovanni was about to say something further to rally the defenders to push the Turks back towards the breach in the wall, a crossbow bolt lodged itself in his throat and stifled the Emperor's friend forever. And as word of Giovanni's death spread around the ranks, the Byzantines and their foreign allies broke ranks and retreated now that the man who had single-handedly kept the Empire together was gone.

“Why are they retreating?" Emperor Constantine asked to himself with his hands folded behind his long purple robes, even though he already knew what the answer was.

"I do not know, my lord," one of the churchmen said.

"The Turks are pouring into the city like a river!" a man who used to be a merchant yelled. "We're doomed!"

"I just saw two priests disappear into the cathedral walls! God is punishing us up for our sins," a woman sobbed.

But then, even though Constantine was coming apart at the moment he knew the city was lost, the Emperor walked calmly through the teeming masses and said, "My friends, fellow Romans! Do not despair. For whatever happens this night, trust in our Lord and Savior, for he has said to us, 'Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven'."

With that, Constantine commanded the guards still inside to bolt the doors to the Hagia Sophia, quickly picked up his sword and shield, and ran through the city in full armor, fueled by adrenaline to meet with his men before they could completely retreat.

His robes were long and cumbersome and the trappings of what little of his Imperial office he had left now only served to slow him down. With that, he cried at the top of his lungs, "The city is fallen and I am still alive," tore them off so as to no longer distinguish himself from his soldiers, and charged into the fray with them. After that, no one saw Constantine again.

Some say even to this day that just at the moment of his death, an angel flew in and carried the beloved last Emperor of Rome away. Others say he left the battle, stood atop a platform overlooking the carnage, and wept before hanging himself.

From that moment on, he became the Marble Emperor, turned to stone and entombed underneath the city until he would awaken again in its hour of need. Simultaneously, legends grew that the two priests who disappeared into the walls of Hagia Sofia would reemerge when the city would be retaken by the soldiers of Christ.

*****

The great oak doors to the Hagia Sophia now leaned slackly against the rotting pillars of stone as the Sultan entered the passageway. It had only been three days since the Ottomans captured Constantinople and already his workers were busy painting over the mosaics of Mary with child with beautiful white Arabic lettering on top of a simple black background, as well as placing minarets at the tops of the towers. Within a month, his planners told him, the mosque would be renovated enough to allow for Friday prayers to be read.

Mehmed's soldiers had also been hard at work looting over the past three days, an enterprise that personally disgusted the young ruler. But this had to be allowed, if only for this limited amount of time, for soldiers on any side of a war these days were often a fickle bunch, prone to deserting if every little demand of theirs was not met. For instance, he had had to build Rumeli Hisari in the shape of the Arabic letters for Muhammad in order to keep morale up, and that had only lasted a week. (It hadn't hurt, however, that his name was styled the same way.)

The results of the three day looting period were almost too much for him to gaze upon. Elderly men who just days earlier had been praying for deliverance from the prophet Isa, who they called Jesus, were now stacked on wagons and preparing to be dumped into the Bosporus. Children were in shackles, about to be sold to slave markets as far as the Songhai in the heart of Africa. And women and young girls were weeping, their clothes in tatters.

He could do nothing about those whose freedom had already been lost, but now his voice boomed through the mosque,

"Henceforth, those who are still in hiding will not be harmed."

Hopefully, he thought, this would be the first step in beginning to rebuild the city to its former glory. Soon, he reasoned, it would become the glorious, shimmering golden crown of an Empire without end. It would welcome commerce from all over the world, shelter Muslim, Christian, and Jew, and become the greatest power the world had ever known. "The spider weaves the curtains in the palace of the Caesars and the owl calls the watches in the towers of Afrasiab," Mehmed had proclaimed when he first stepped into the city. Hopefully, that would not be the case for much longer.

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

WOMEN IN BULGARIAN HISTORY :: Elena Asenina, Empress of Nicaea

Elena Asenina (also known as Elena of Bulgaria) was born in the 13th century, possibly in 1224. The daughter of tsar Ivan Asen II of Bulgaria and his second wife Anna Maria of Hungary, she was probably named after her paternal grandmother Elena.

Elena’s grandfather was Ivan Asen I, who, together with his elder brother Peter founded the Second Bulgarian Tsardom in 1185. After the two brothers were successivly assassinated, their youngest brother Kaloyan became tsar in 1197. After Kaloyan himself was assassinated 10 years later, his supporters tried to secure the throne for Ivan Asen II, however, his cousin Boril seized the throne instead and he and his brother Alexander were forced to flee to “the lands of the Russians”. Boril, however, never managed to strenghten his rule, which enabled Ivan Asen II to muster an army and return to Bulgaria, capturing the capital Turnovo and blinding his cousin Boril in 1218. Once tsar, Ivan Asen II tried to conclude alliances with the neighbouring powers through marriages - the first one being his marriage to Elena’s mother - Anna of Hungary, followed by his daughter and Elena’s older sister Maria’s marriage to Manuel Komnenos Doukas, brother of the ruler of Epirus, Emperor of Thessalonica and self-proclaimed Byzantine Emperor Theodore Komnenos Doukas.

Another advantageous marriage would be that of Elena. In 1228, the neighbouring Latin Empire’s ruler, Robert I, died, leaving the Empire to his underaged brother Baldwin II. The Latin aristocrats offered the regency to Ivan Asen II, who agreed. Elena was betrothed to the Latin Emperor to strenghten the new alliance and was most likely sent to Constantinople. However, feeling threatened by Ivan Asen II’s increasing influence, the Latins soon started secretly negotiating with the former King of Jerusalem, John of Brienne, offering him the regency instead. Once John of Brienne was ceremoniously crowned as co-Emperor in 1231 and Elena was sent back home, Ivan Asen II was furious, tearing the treaty and the union with the Catholic Roman Church (signed by his uncle Kaloyan) down.

Ivan Asen II then turned to the Nicaean Empire (founded by the Byzantines after Constantinople was occupied by the crusaders in 1204), signing a treaty with Emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes. To strenghten this alliance, Elena was betrothed to the emperor’s son, Theodore Laskaris in 1234. Ivan Asen II also sent envoys to the Ecumenical Patriarch Germanus II to start negotiations about the position of the Bulgarian Church. In the following 1235 Ivan Asen II and John III Doukas Vatatzes met to conclude a former alliance. According to George Akropolites

“Then Asen and his wife, the Hungarian Maria, and his daughter Elena came to Kaliopolis and met the Emperor there. Both did the necessery in terms of friendship. Ivan Asen did not go to Hellespont but stayed within the borders of Kaliopolis. Emperor John went to Lampsacus with his [Ivan Asen’s] wife and daughter, where Empress Irene was. There the children were married by Patriarch Germanus. It was then decided by the Emperor’s decree that the Archbishop of Turnovo, who was subordinate to Constantinople, should be named Patriarch, as the rulers thanked the Bulgarian ruler Asen for his friendship. After everything was done, Empress Irene took her son and his bride and lived in the eastern lands. Asen’s wife also returned to her lands. Emperor John and Asen took with them troops and attacked the western lands that were under the yoke of the Latins.”

This alliance, however, worried Ivan Asen II’s son-in-law’s brother, Theodore Komnenos Doukas, who hoped he would be the one to restore the Byzantine Empire. Thus Theodore invaded Bulgaria but was decisively defeated by Ivan Asen II himself in the battle of Klokotnitsa and was later captured and deposed. Epirus was now ruled by his brother Manuel, who swore fealty to his father-in-law Ivan Asen II.

Bulgarian and Latin troops unsuccessfully laid seige on Constantinople twice. The unsuccess and the death of John of Brienne (which was a possibility for Ivan Asen II to finally become regent of the Latin Empire) in 1237 made Ivan Asen II put an end to the alliance with the Nicaean Empire. Elena returned to Bulgaria.

“As his [John III Doukas Vatatzes’] son Theodore was a child - he was, as we said, 11 years old when he married princess Elena - the marriage remained formal. They were taken and educated by Empress Irene, for she was of good characted and inclined to everything good. And so the Latins’ situation was very difficult and they were humiliated by the intermarriage of the two Autocrats. King John [of Brienne], having lived a little longer, died and left the power in Constantinople to his son-in-law Baldwin and Asen, regretting, as it turned out, the treaties with Emperor John, sought a way to free his daughter from her marriage to Emperor Theodore and to marry her to another. Because as the ruler of a nation that was once subordinate to the Romans, he was afraid of a favourable turn for them. And so he was looking, as it seemed, for an excuse, although this was not a secret to those who knew the situation. He sent envoys to the Emperor and the Empress, to tell them that because they were close to Adrianopolis, he and his wife wanted to see their daughter and give her paternal embrace. They would do this and then immediately send her back to her father-in-law and her husband. Although Emperor John and Empress Irene realized what could happen, they sent Asen his daughter. They knew that if he keeps his daughter and takes her away from her lawful husband there is a God who sees everything and punishes those who break the oaths and treaties made before God. And so the Bulgarian took his daughter and left, sending those who accompanied her back. He headed for Turnovo but his daughter wept for her mother-in-law - Empress Irene - and grieved because she was separated from her husband. Then, it is said, Asen took her to sit on his saddle, hit her with [his] hand on her head and threatened to kill her if she did not silently bear what he had decided for her.” - George Akropolites

Ivan Asen II then concluded an alliance with the Latin Empire against Nicaea. Bulgarian and Latin troops laid seige to Tzurulum. Ivan Asen II was there himself, when news of the simultaneous deaths of his wife Anna Maria of Hungary, his youngest son Peter and the Patriarch reached him. He took these events as signs of the wrath of God for breaking the alliance with John III Doukas Vatatzes, abandoned the seige and sent Elena back to Nicaea at the end of 1237.

And so Elena stayed with her husband, Theodore Laskaris. The two had 6 children:

Irene - married Constantine Tikh Asen of Bulgaria

Maria - married Nikephoros I Komnenos Doukas of Epirus

Theodora - married Mathieu de Mons, baron of Veligosti

Eudoxia - first married Pietro I, Count of Ventimiglia and then Arnaud Roger, Count of Pallars-Subirà

a daughter whose name is unknown - married Yakov Svetoslav, a Bulgarian despot

John IV Doukas Laskaris - Emperor of Nicaea

In 1254, after John III Doukas Vatatzes’ death, Theodore Laskaris became Emperor and thus Elena became Empress of Nicaea. 4 years later, in 1258, Theodore II Laskaris died and Elena’s son John became Emperor.

The date of Elena’s death is not known. It is believed that she was alive when her son was blinded on the orders of Michael VIII Palaiologos on his eleventh birthday. It is possible she died shortly afterwards.

#women in history#women in bulgarian history#elena asenina#helena asenina#elena of bulgaria#helena of bulgaria#nicaean empress#empress of nicaea#historyedit#perioddramaedit#myedit#fancast#holliday grainger#the borgias#13th century#insteresting women#unknown women#bulgarian history#european history#medieval#medieval history#long live the queue

139 notes

·

View notes