#John D’Emilio

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I need to queen out with John D’Emilio. I also need him to take me to get New York Style pizza in Chicago with me.

#i am very normal#i am so fine and normal I am not daddy issues posting that’s not what I’m doing at all#I just wanna hang out with an older Italian American gay man and have him teach me things is that so wrong?#gay history#queer history#John D’Emilio#history#historian

0 notes

Text

This quote, from John D’Emilio’s 1989 essay Not A Simple Matter: Gay History and Gay Historians, highlights exactly why I hate the vapid memes about historians and historical erasure:

This is what the founders of gay history, as an academic discipline, were facing at the time: both the genuine barriers within academia and an internalised sense that their work wasn’t as valuable, academic, relevant etc as that produced in other specialisations within history. Queer elders in academia— many of whom lacked formal training, and were community organisers as well— laid the groundwork for those of us continuing that struggle now.

Ignoring the work of actual lgbtq+ historians, past and present, colludes in the erasure and flattening of our history rather than its expansion.

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: Navigating Homosexuality in Ancient Greece: A Comprehensive Exploration

Introduction: Embarking on a journey through the complexities of homosexuality in ancient Greece requires a thorough understanding of the cultural and historical context. From the archaic period to the classical era, societal attitudes towards same-sex love evolved, influenced by religious beliefs, and shaped by city-state politics.

Symposiums and the Dichotomy of Same-Sex Relationships: Symposiums in ancient Greece served as intellectual hubs and settings for the expression of same-sex desire. Eros, the god of love, infused these gatherings with passion, contributing to a rich tapestry of relationships in both public and private spheres. The dichotomy between intellectual and personal aspects of symposiums reflects the nuanced nature of same-sex relationships, where cultural acceptance coexisted with a need for discretion.

Pederasty: A Complex Institution: The institution of pederasty reflects a complex interplay of cultural norms, educational aspirations, and power dynamics. In this practice, an adult male (erastes) over 20 formed a relationship with a younger male (eromenos). "Pederasty literally means lust for, or love of, in a strong sexual sense, children," explains Professor Cartledge, specifying that it refers specifically to boys in ancient Greece (HistoryExtra). Pederasty was widely accepted in certain city-states and social classes but not without controversy and criticism. Examining this practice provides insights into the multifaceted nature of same-sex relationships and their intersection with education, mentorship, and broader societal structures.

Challenges and Shadows in Ancient Greek Society: Acknowledging the challenges and shadows in ancient Greek society offers a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities individuals faced in expressing their sexuality. While certain forms of same-sex love were accepted, societal expectations, stigmas, and potential consequences cast shadows on the experiences of those deviating from accepted norms. "That such pure love is not deemed possible between men and women" raises questions about the historical perception of love within heterosexual relationships (Hawkes, "A Sociology of Sex and Sexuality").

Greek Ethic of Pleasure: The concept of aphrodesia was fundamental to the Greek ethic of pleasure, viewing sexual pleasure as a significant component of a fulfilling life. The ancient Greek idea of "one sex" suggested that men and women shared a common human nature, including similar desires and passions. Gail Hawkes discusses this concept, stating, "there was a belief that men and women shared a common human nature, including similar desires and passions" ("A Sociology of Sex and Sexuality").

Queer Evolution: The term "queer" has evolved significantly, shifting from its historical usage to describe those who were considered strange to its contemporary usage within the LGBTQ+ community. Understanding the historical context and myths surrounding the "eternal homosexual" provides insights into the complex relationship between sexuality and societal acceptance over time. John D’Emilio notes, "gay men and lesbians always were and always will be" throughout history, challenging the myth of the "eternal homosexual" (D’Emilio, "Capitalism and Gay Identity").

Conclusion: Exploring the intricacies of homosexuality in ancient Greece reveals a nuanced landscape shaped by cultural, political, and philosophical factors. While certain practices like pederasty were common, societal attitudes varied, and the interplay of acceptance and limitations shaped the experiences of individuals expressing their sexuality in ancient Greek society.

D’Emilio, John, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” pp. 169-178 in Lancaster and di Leonardo, The Gender Sexuality Reader, NY: Routledge, 1997.

Hawkes, Gail, A Sociology of Sex and Sexuality. Philadelphia: Open University Press 1999.

0 notes

Text

According to D’Emilio “There is another historical myth that enjoys nearly universal assertion in the gay movement, the myth of the "eternal homosexual." The argument runs something like this: gay men and lesbians always were and always will be. We are everywhere; nor just now, but throughout history, in all societies and all periods”(170).

From this quote, one can understand that in the 16th and 18th centuries, being gay was not taken seriously. then there were many problems with the economy and refugees and people simply were not up to the problems of the LGBT community, but still, they continued to be humiliated.

D’Emilio, John, “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” pp. 169-178 in Lancaster and di Leonardo, The Gender Sexuality Reader, NY: Routledge, 1997.

0 notes

Note

Damn, Matteo... Your thoughts on transmasculine oppression are just *kisses ur brain* This is also sooo in-line with ideas that both Kate Bornstein and Leslie Feinberg have discussed in that 1996 interview. I feel like that interview should be a mandatory watch for all the online queers fr

👁👁 i watched the interview and im very flattered you think my thoughts are like the founding queers of the community. I dont feel like anything I say here is new; countless people have written countless articles and books about my thoughts regarding queerness. I mean besides Leslie and Bornstein, theres John D’Emilio, Jonathan Katz, Michael Bronski, Susan Stryker, Gil Cuadros, Essex Hemphill, Marsha P Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and so many more. I know academic is not accessible to everyone, but it is more accessible now than ever before, and I just want to encourage any and all queers to read up on our history and lived experience. I also feel this interview should be mandatory, I definitely felt myself becoming more and more transsexual HAHA but thank u for the compliment, I appreciate it :)

#muertoresponds#thanks for kissing my brain#queer theory#ive been doing nothing but queer reading the past 3 weeks so#my brain is full of queer theory

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

[“Marriage manuals were best sellers because the average American wanted to read and think about sexuality. Americans discovered that the changes wrought by the sexology movements allowed them to have discussions not possible before. Changes in book distribution, the low cost of mass book production, and increasing literacy rates made this information easily accessible to a huge, diverse readership. Not all Americans could agree on the specifics of sex education, but most agreed that the topic should be discussed. As Estelle Freedman and John D’Emilio point out, “[B]y the 1920s circumstances were present to encourage acceptance of the modern idea that sexual expression was of overarching importance to individual happiness.”

This “modern idea” was antithetical to the social purity movement, since one person’s sexual expression was another’s mortal sin. The vision of social purity was fueled mainly by women and men who were attempting to gain full citizenship for women through suffrage and other reforms. Some, such as Frances Willard, had lives centered on other women. Unfortunately, this vision was essentially denying full citizenship to others, especially racial minorities. The social purity movement also reinforced social standards that were directly antithetical to sexual freedom and directly harmful to many women and men who desired their own sex. These standards, predicated on traditional heterosexual ideals of gender, were written into laws clearly delineating what was legally pure and impure. That was the language of politics. The politics of language, in contrast, allowed for an individual interpretation that was not based on absolutes. People wanted to read about sex so that they could imagine, in private, their sexual lives. This was the underlying fear about masturbation and its connection to sexual fantasies.”]

michael Bronski, a queer history of America

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I highly recommend these books on US queer history:

George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940

Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness

Allan Bérubé, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in the Second World War

David Johnson, The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in The Federal Government

Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name

John D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority, 1945-1970

Dudley Clendinin and Adam Nagourney, Out for Good: The Struggle to Build a Gay Rights Movement in America

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

I am begging some of y’all to learn even the first thing about LGBTQ+ history. Please.

Here are some resources (with links!) to get you started:

Before Stonewall

(a documentary about LGBTQ+ life before the Stonewall riots of 1969, including interviews with queer elders).

Nancy podcast, The Word ‘Queer’

(on the history of the word ‘queer’ and its relation to LGBTQ+ people).

Jeffrey Weeks, “Against Nature”

(on the importance of understanding categories of gender and sexuality as historically contingent, culturally specific, and socially constructed rather than “natural,” universal, or innate).

Jonathan Ned Katz, “The Invention of Heterosexuality”

(on the origin of the concepts “heterosexual” and “homosexual,” the history of late-19th century sexology, and the formation of modern norms of sexuality).

John D’Emilio, “Capitalism and Gay Identity”

(on the role of capitalism in the formation of LGBTQ+ communities in the first half of the 20th century).

Michel Foucault, “We ‘Other Victorians’”

(on some of the persistent pitfalls and traps that people fall into when thinking about the history of sexuality, and the recent origins of our ideas about sexuality itself).

Leslie Feinberg, “Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come”

(an early work on trans politics and history that aims to show that trans people have always existed).

Susan Stryker, “A Hundred-Plus Years of Transgender History”

(a more historical account of the formation of trans identities, and the existence of gender nonconforming individuals pre- the formation of LGBTQ+ community).

Sheila Cavanagh, “Touching Gender: Abjection and the Hygienic Imagination”

(on the history of gender-segregated public toilets and how they have contributed to the construction and policing of norms of gender and sex).

Siobhan Somerville, “Scientific Racism and the Invention of the Homosexual Body”

(an examination of the connection between the invention of racial categories and early sexology). Scott Lauria Morgensen, “The Biopolitics of Settler Sexuality and Queer Modernities”

(a theoretical and historical examination of the way norms of gender and sexuality have been enforced through colonization and settler colonialism).

Making Gay History podcast series on Stonewall

(a series of podcasts about the Stonewall riots of 1969 which acted as a catalyst for the Gay Liberation and the modern LGBTQ+ rights movement, including Pride. Includes interviews with Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P. Johnson, and other central figures who were present at the riots).

“Prelude to a Riot”

“Everything Clicked...And The Riot Was On”

“Say it Loud! Gay and Proud!”

New York Times, “The Stonewall You Know is a Myth, and That’s O.K.”

(debunking some of the persistent myths about the Stonewall riots).

Sylvia Rivera, “Y’all Better Quiet Down -- Christopher Street Liberation Day, 1973″

(a famous speech given by Sylvia Rivera to the crowd at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day (i.e., Pride) event in New York. Note how the crowd boos her and tries to get her off the stage).

United In Anger: A History of ACT UP

(a documentary about the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s/90s and the community of activists that helped shift perception and policy around the virus).

David France, How to Survive a Plague

(David France discusses his book on the history of the HIV/AIDS epidemic).

PhilosophyTube, “Queer*”

(an excellent video essay on queer theory and the “queer” turn in LGBT politics, community, etc.)

All of this is just a beginning. There are tons of other free resources out there, and I encourage people to add on to this post with recommendations.

#lgbt#lgbtq+#queer#trans#history#lgbtqia2s+ history#resources#queer history#trans history#texts#podcasts#documentary#personal#pride#pride month#gay history#lesbian history#stonewall#before stonewall#ACT UP#sylvia rivera#making gay history#nancy

813 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Always these were blue-collar guys, identifiable as such because they weren't wearing the white shirt, jacket, and tie that was the universal uniform of office workers. We never exchanged information about ourselves. One guy did start talking. He asked if I had friends whom I did this with but I just shook my head no. Occasionally they told me their first names, but I was too scared to say anything back. This was come (literally) and go, as fast as possible. After my arrival home, I had to act as if nothing unusual happened. I covered my tracks by talking about all that I had done at school, how I had stayed late because of a practice debate or a basketball game. If I was learning anything beyond that there were men who wanted to have sex with men, it was how easy it was to like, to invent stories so that no one ever knew what was going on.

John D’Emilio from Memories of a Gay Catholic Boyhood

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

an endearing marxist syllabus

Summer and Fall/Autumn 2021 – Winter 2022

I. What is the Left? – What is Marxism?

Thursdays, starting July 29th 6:00 - 8:00 p.m. SEC Plaza, Memorial Union, Oregon State University 2501 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, OR 97331

• required / + recommended reading

Marx and Engels readings pp. from Robert C. Tucker, ed., Marx-Engels Reader (Norton 2nd ed., 1978)

Week A. Introduction: Capital in history | Jul. 29, 2021

• Max Horkheimer, "The little man and the philosophy of freedom" (1926–31)

• epigraphs on modern history and freedom by Louis Menand (on Marx and Engels), Karl Marx, on "becoming" (from the Grundrisse, 1857–58), and Peter Preuss (on history)

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) chart of terms

• Chris Cutrone, "Capital in history" (2008)

+ Capital in history timeline and chart of terms

+ video of Communist University 2011 London presentation

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

• Cutrone, "The Marxist hypothesis" (2010)

• Cutrone, “Class consciousness (from a Marxist persective) today” (2012)

+ G.M. Tamas, "Telling the truth about class" [HTML] (2007)

+ Robert Pippin, "On Critical Theory" (2004)

+ Rainer Maria Rilke, "Archaic Torso of Apollo" (1908)

Week B. 1960s New Left I. Neo-Marxism | Aug. 5, 2021

• Martin Nicolaus, “The unknown Marx” (1968)

+ Commodity form chart of terms

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

+ Organic composition of capital chart of terms

+ Marx on surplus-value chart of terms

• Theodor W. Adorno, “Late Capitalism or Industrial Society?” (AKA “Is Marx Obsolete?”) (1968)

• Moishe Postone, “Necessity, labor, and time” (1978)

+ Postone, “Interview: Marx after Marxism” (2008)

+ Postone, “History and helplessness: Mass mobilization and contemporary forms of anticapitalism” (2006)

+ Postone, “Theorizing the contemporary world: Brenner, Arrighi, Harvey” (2006)

Week C. 1960s New Left II: Gender and sexuality | Aug. 12, 2021

The situation of women is different from that of any other social group. This is because they are not one of a number of isolable units, but half a totality: the human species. Women are essential and irreplaceable; they cannot therefore be exploited in the same way as other social groups can. They are fundamental to the human condition, yet in their economic, social and political roles, they are marginal. It is precisely this combination — fundamental and marginal at one and the same time — that has been fatal to them.

— Juliet Mitchell, "Women: The longest revolution" (1966)

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

• Juliet Mitchell, “Women: The longest revolution” (1966)

• Clara Zetkin and Vladimir Lenin, “An interview on the woman question” (1920)

• Theodor W. Adorno, “Sexual taboos and the law today” (1963)

• John D’Emilio, “Capitalism and gay identity” (1983)

Week D. 1960s New Left III. Anti-black racism in the U.S. | Aug. 19, 2021

As a social party we receive the Negro and all other races upon absolutely equal terms. We are the party of the working class, the whole working class, and we will not suffer ourselves to be divided by any specious appeal to race prejudice; and if we should be coaxed or driven from the straight road we will be lost in the wilderness and ought to perish there, for we shall no longer be a Socialist party.

— Eugene Debs, "The Negro in the class struggle" (1903)

+ Eugene Debs, "The Negro in the class struggle" (1903)

+ Debs, "The Negro and his nemesis" (1904)

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

• Richard Fraser, “Two lectures on the black question in America and revolutionary integrationism” (1953)

+ Fraser, "For the materialist conception of the Negro struggle" (1955)

• James Robertson and Shirley Stoute, “For black Trotskyism” (1963)

+ Spartacist League, “Black and red: Class struggle road to Negro freedom” (1966)

+ Bayard Rustin, “The failure of black separatism” (1970)

• Adolph Reed, “Black particularity reconsidered” (1979)

+ Reed, “Paths to Critical Theory” (1984)

Week E. Frankfurt School precursors | Aug. 26, 2021

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

• Wilhelm Reich, “Ideology as material power” (1933/46)

• Siegfried Kracauer, “The mass ornament” (1927)

+ Kracauer, “Photography” (1927)

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) / immanent dialectical critique chart of terms

Week F. Radical bourgeois philosophy I. Rousseau: Crossroads of society | Sep. 2, 2021

To be radical is to go to the root of the matter. For man, however, the root is man himself. — Marx, Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right (1843)

Whoever dares undertake to establish a people’s institutions must feel himself capable of changing, as it were, human nature, of transforming each individual, who by himself is a complete and solitary whole, into a part of a larger whole, from which, in a sense, the individual receives his life and his being, of substituting a limited and mental existence for the physical and independent existence. He has to take from man his own powers, and give him in exchange alien powers which he cannot employ without the help of other men.

— Jean-Jacques Rousseau, On the Social Contract (1762)

• Max Horkheimer, "The little man and the philosophy of freedom" (1926–31)

• epigraphs on modern history and freedom by James Miller (on Jean-Jacques Rousseau), Louis Menand (on Marx and Engels), Karl Marx, on "becoming" (from the Grundrisse, 1857–58), and Peter Preuss (on history)

+ Rainer Maria Rilke, "Archaic Torso of Apollo" (1908)

+ Robert Pippin, "On Critical Theory" (2004)

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) chart of terms

• Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the Origin of Inequality (1754) PDFs of preferred translation (5 parts): [1] [2] [3] [4] [5]

+ Capital in history timeline and chart of terms

• Rousseau, selection from On the Social Contract (1762)

Week G. Radical bourgeois philosophy II. Adam Smith: On the wealth of nations (part 1) | Sep. 9, 2021

• Adam Smith, selections from The Wealth of Nations

Volume I [PDF] Introduction and Plan of the Work Book I: Of the Causes of Improvement… I.1. Of the Division of Labor I.2. Of the Principle which gives Occasion to the Division of Labour I.3. That the Division of Labour is Limited by the Extent of the Market I.4. Of the Origin and Use of Money I.5 Of the Real and Nominal Price of Commodities I.6. Of the Component Parts of the Price of Commodities I.7. Of the Natural and Market Price of Commodities I.8. Of the Wages of Labour I.9. Of the Profits of Stock Book III: Of the different Progress of Opulence in different Nations III.1. Of the Natural Progress of Opulence III.2. Of the Discouragement of Agriculture in the Ancient State of Europe after the Fall of the Roman Empire III.3. Of the Rise and Progress of Cities and Towns, after the Fall of the Roman Empire III.4. How the Commerce of the Towns Contributed to the Improvement of the Country

Week H. Radical bourgeois philosophy III. Adam Smith: On the wealth of nations (part 2) | Sep. 16, 2021

• Smith, selections from The Wealth of Nations

Volume II [PDF] IV.7, Of Colonies V.1. Of the Expences of the Sovereign or Commonwealth

Week I. Radical bourgeois philosophy IV. What is the Third Estate? | Sep. 23, 2021

• Abbé Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès, What is the Third Estate? (1789) [full text]

+ Bernard Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees (1732)

Week J. Radical bourgeois philosophy V. Kant and Constant: Bourgeois society | Sep. 30, 2021

• Immanuel Kant, "Idea for a universal history from a cosmopolitan point of view" and "What is Enlightenment?" (1784)

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) chart of terms

+ Kant's 3 Critiques [PNG] and philosophy [PNG] charts of terms

• Benjamin Constant, "The liberty of the ancients compared with that of the moderns" (1819)

+ Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discourse on the origin of inequality (1754)

+ Rousseau, selection from On the social contract (1762)

Week K. Radical bourgeois philosophy VI. Hegel: Freedom in history | Oct. 7, 2021

• G.W.F. Hegel, Introduction to the Philosophy of History (1831) [HTML] [PDF pp. 14-128] [Audiobook]

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) chart of terms

Week 1. What is the Left? I. Capital in history | Oct. 14, 2021

• Max Horkheimer, "The little man and the philosophy of freedom" (1926–31)

• epigraphs on modern history and freedom by Louis Menand (on Marx and Engels), Karl Marx, on "becoming" (from the Grundrisse, 1857–58), and Peter Preuss (on history)

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) chart of terms

• Chris Cutrone, "Capital in history" (2008)

+ Capital in history timeline and chart of terms

+ video of Communist University 2011 London presentation

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

• Cutrone, "The Marxist hypothesis" (2010)

• Cutrone, “Class consciousness (from a Marxist persective) today” (2012)

+ G.M. Tamas, "Telling the truth about class" [HTML] (2007)

+ Robert Pippin, "On Critical Theory" (2004)

+ Rainer Maria Rilke, "Archaic Torso of Apollo" (1908)

Week 2. What is the Left? II. Utopia and critique | Oct. 21, 2021

• Max Horkheimer, selections from Dämmerung (1926–31)

• Adorno, “Imaginative Excesses” (1944–47)

• Leszek Kolakowski, “The concept of the Left” (1958)

• Herbert Marcuse, "Note on dialectic" (1960)

• Marx, To make the world philosophical (from Marx's dissertation, 1839–41), pp. 9–11

• Marx, For the ruthless criticism of everything existing (letter to Arnold Ruge, September 1843), pp. 12–15

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) / immanent dialectical critique chart of terms

Week 3. What is Marxism? I. Socialism | Oct. 28, 2021

• Marx, selections from Economic and philosophic manuscripts (1844), pp. 70–101

+ Commodity form chart of terms

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) / immanent dialectical critique chart of terms

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

• Marx and Friedrich Engels, selections from the Manifesto of the Communist Party (1848), pp. 469–500

• Marx, The coming upheaval (from The Poverty of Philosophy, 1847), pp. 218–19

Week 4. What is Marxism? II. Revolution in 1848 | Nov. 4, 2021

• Marx, Address to the Central Committee of the Communist League (1850), pp. 501–511 and Class struggle and mode of production (letter to Weydemeyer, 1852), pp. 218–220

• Engels, The tactics of social democracy (Engels's 1895 introduction to Marx, The Class Struggles in France), pp. 556–573

• Marx, selections from The Class Struggles in France 1848–50 (1850), pp. 586–593

• Marx, selections from The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), pp. 594–617

Week 5. What is Marxism? III. Bonapartism | Nov. 11, 2021

+ Karl Korsch, "The Marxism of the First International" (1924)

• Marx, Inaugural address to the First International (1864), pp. 512–519

• Marx, selections from The Civil War in France (1871, including Engels's 1891 Introduction), pp. 618–652

+ Korsch, Introduction to Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme (1922)

• Marx, Critique of the Gotha Programme, pp. 525–541

• Marx, Programme of the Parti Ouvrier (1880)

Week 6. What is Marxism? IV. Critique of political economy | Nov. 18, 2021

The fetish character of the commodity is not a fact of consciousness; rather it is dialectical, in the eminent sense that it produces consciousness. . . . [P]erfection of the commodity character in a Hegelian self-consciousness inaugurates the explosion of its phantasmagoria. — Theodor W. Adorno, letter to Walter Benjamin, August 2, 1935

+ Commodity form chart of terms

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

+ Organic composition of capital chart of terms

+ Marx on surplus-value chart of terms

• Marx, selections from the Grundrisse (1857–61), pp. 222–226, 236–244, 247–250, 276–293 ME Reader pp. 276–281

• Marx, Capital Vol. I, Ch. 1 Sec. 4 "The fetishism of commodities" (1867), pp. 319–329

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) / immanent dialectical critique chart of terms

Winter break readings

+ Richard Appignanesi and Oscar Zarate / A&Z, Introducing Lenin and the Russian Revolution / Lenin for Beginners (1977) + Sebastian Haffner, Failure of a Revolution: Germany 1918–19 (1968) + Tariq Ali and Phil Evans, Introducing Trotsky and Marxism / Trotsky for Beginners (1980) + James Joll, The Second International 1889–1914 (1966) + Carl Schorske, The SPD 1905-17: The Development of the Great Schism (1955) + J.P. Nettl, Rosa Luxemburg (1966) [Vol. 1] [Vol. 2] + Edmund Wilson, To the Finland Station: A Study in the Writing and Acting of History (1940), Part II. Ch. (1–4,) 5–10, 12–16; Part III. Ch. 1–6

Week 8. Nov. 25, 2021 U.S. Thanksgiving break

Week 7. What is Marxism? V. Reification | Dec. 2, 2021

• Georg Lukács, “The phenomenon of reification” (Part I of “Reification and the consciousness of the proletariat,” History and Class Consciousness, 1923) + Commodity form chart of terms + Reification chart of terms + Capitalist contradiction chart of terms + Organic composition of capital chart of terms + Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) / immanent dialectical critique chart of terms

Week 9. What is Marxism? VI. Class consciousness | Dec. 9, 2021

• Lukács, “Class Consciousness” (1920), Original Preface (1922), “What is Orthodox Marxism?” (1919), History and Class Consciousness (1923) + Capitalist contradiction chart of terms + Reification chart of terms + Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) / immanent dialectical critique chart of terms + Herbert Marcuse, "Note on dialectic" (1960) + Marx, Preface to the First German Edition and Afterword to the Second German Edition (1873) of Capital (1867), pp. 294–298, 299–302

Week 10. What is Marxism? VII. Ends of philosophy | Dec. 16, 2021

• Korsch, “Marxism and philosophy” (1923)

+ Capitalist contradiction chart of terms

+ Being and becoming (freedom in transformation) / immanent dialectical critique chart of terms

+ Herbert Marcuse, "Note on dialectic" (1960) + Marx, To make the world philosophical (from Marx's dissertation, 1839–41), pp. 9–11

+ Marx, For the ruthless criticism of everything existing (letter to Arnold Ruge, September 1843), pp. 12–15

+ Marx, "Theses on Feuerbach" (1845), pp. 143–145

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

America’s Gay Men in WW2

World War Two was a “National Coming Out” for queer Americans.

I don’t think any other event in history changed the lives of so many of us since Rome became Christian.

For European queers the war brought tragedy.

The queer movement began in Germany in the 1860s when trans activist Karl Ulrichs spoke before the courts to repeal Anti-Sodomy laws. From his first act of bravery the movement grew and by the 1920s Berlin had more gay bars than Manhattan did in the 1980s. Magnus Hirschfeld’s “Scientific Humanitarian Committee” fought valiantly in politics for LGBT rights and performed the first gender affirmation surgeries. They were a century ahead of the rest of the world.

The Nazis made Hirschfeld - Socialist, Homosexual and Jew - public enemy number one.

The famous image of the Nazis burning books? Those were the books of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee. Case studies of the first openly queer Europeans, histories, diaries - the first treasure trove of our history was destroyed that day.

100,000 of us were charged with felonies. As many as 15,000 were sent to the camps, about 60% were murdered.

But in America the war brought liberation.

In a country where most people never even heard the word “homosexual” , historian John D’emilio wrote the war was “conducive both to the articulation of a homosexual identity and to the more rapid evolution of a gay subculture. (24)” The war years were “a Watershed (Eaklor 68)”

Now before we begin I need to give a caveat. The focus of this first post is not lesbians, transfolk or others in our community. Those stories have additional complexity the story of cisgender homosexual men does not. Starting with gay men lets me begin in the simplest way I can, in subsequent posts I’ll look at the rest of our community.

Twilight Aristocracy: Being Queer Before the War

I want us to go back in time and imagine the life of the typical queer American before the war. Odds are you lived on a farm and simply accepted the basic fact that you would marry and raise children as surely as you were born or would die. You would have never seen someone Out or Proud. If you did see your sexuality or gender in contrary ways you had no words to express it, odds are even your doctor had never heard the term “Homosexual. In your mind it was just a quirk, without a name or possible expression.

In the city the “Twilight Aristocracy” lived hidden, on the margins and exposed their queerness only in the most coded ways. Gay men “Dropping pins” with a handkerchief in a specific pocket. Butch women with key chains heavy enough to show she didn’t need a man to carry anything for her. A secret language of “Jockers” and “Nances” “Playing Checkers” during a night out. There is a really good article on the queer vernacular here

And these were “Lovers in a Dangerous Time.”

In public one must act as straight as possible. Two people of the same gender dancing could be prosecuted. Cross dressing, even with something as trivial as a woman wearing pants, would run afoul of obscenity laws.

The only spaces we had for ourselves were dive bars, run by organized crime. But even then one must be sure to be circumspect, and act straight. Anyone could be an undercover cop. If a gaze was held to long, or lovers kissed in a corner the bar would be raided. Police saw us as worthy candidates for abuse so beatings were common and the judge would do all he could to humiliate you.

Now Michael Foucault, the big swinging french dick of queer theory, laid out this whole theory about how the real policing in a society happens inside our heads. Ideas about sin, shame, normalcy, mental illness can all be made to control people, and the Twilight Aristocracy was no different.

While cruising a park at night, or settled on the sofa with a lifelong lover, the thoughts of Priests and Doctors haunted them. “Am I living in Sin? Am I someone God could love?” “Is this healthy? Have I gone mad? Is this a true love or a medical condition which requires cure?”

There was no voice in America yet healing our self doubt, or demanding the world accept us as we are. And that voice, the socialist Harry Hay, did not come during the war, but it would come shortly after directly because of it.

Johnny Get Your Gun… And are you now or ever been a Homosexual?

For the first time in their lives millions of young men crossed thousands of miles from their home to the front.

But before they made that brave journey they had another, unexpected and often torturous journey. The one across the doctor’s office at a recruiting station.

In the nineteenth century queerness moved from an act, “Forgive me Father I have sinned, I kissed another man” to something you are, “The homosexual subspecies can be identified by certain physical and psychological signs.”

These were the glory days of patriarchy and white supremacy, those who transgressed the line between masculine and feminine called the whole culture into question. So doctors obsessed themselves with queerness, its origins, its signs, its so called catastrophic racial consequences and its cure.

“Are you a homosexual?” doctors asked stunned recruits.

If you were closeted but patriotic, you would of course deny the accusation. But the doctor would continue his examination by checking if you were a “Real Man.”

“Do you have a girlfriend? Did you like playing sports as a kid?”

If you passed that, the doctor would often try and trip you up by asking about your culture.

“Do you ever go basketeering?” he would ask, remembering to check if there was any lisp or effeminacy in your voice.

Finally if the doctor felt like it he could examine your body to see if you were a member of the homosexual subspecies.

Your gag reflex would be tested with a tongue depressor. Another hole could be carefully examined as well.

Humiliating enough for a straight man. But for a gay recruit the consequences could be life threatening.

Medical authorities knew homosexuals were weak, criminal and mad. To place them among the troops would weaken unit cohesion at the very least, result in treachery at the worst. In civilian life doctors had much the same thing to say.

The recruit needed a cure. And a doctor was always ready. With talk therapy, hypnosis, drugs, electroshock and forced surgeries of the worst kinds there was always a cure ready at hand.

Thankfully the doctors were not successful in their task, one doctor wrote “for every homosexual who was referred or came to the Medical Department, there were five or ten who never were detected. (d’Emilio 25)”

Here’s the irony though, by asking such pointed and direct questions to people closeted to themselves it forced them to confront their sexuality for the first time.

Hegarty writes, “As a result of the screening policies, homosexuality became part of wartime discourse. Questions about homosexual desire and behavior ensured that every man inducted into the armed forces had to confront the possibility of homosexual feelings or experiences. This was a kind of massive public education about homosexuality. Despite—and be-cause of—the attempts to eliminate homosexuals from the military, men with same-sex desires learned that there were many people like themselves (Hegarty 180)”

And then it gave them a golden opportunity to have fun.

The 101st Airborn - Homosocial and Homosexual

“Homosocial” refers to a gender segregated space. And they were often havens for gay men. The YMCA for example really was a place for young gay men to meet.

Now the government was already aware of the kind of scandalous sexual behaviour young men can get up to when left to themselves. Two major government programs before the war, the Federal Transient Program and the Civilian Conservation Corps focused on unattached young men, but over time these spaces became highly suspect and the focus shifted to helping family men so as to avoid giving government aid to ‘sexual perversion’ in these homosocial spaces.

But with the war on there was no choice but to put hundreds of thousands of young men in their own world. All male boot camps, all male bases, all male front lines.

The emotional intensity broke down the barriers between men and the strict enforcement of gendered norms.

On the front the men had no girlfriend, wife or mother to confide in. The soldier’s body was strong and heroic but also fragile. Straight men held each other in foxholes and shared their emotional vulnerability to each other. Gender lines began to blur as straight men danced together in bars an action that would result in arrest in many American cities.

Bronski writes, “Men were now more able to be emotional, express their feelings, and even cry. The stereotypical “strong, silent type,” quintessentially heterosexual, that had characterized the American Man had been replaced with a new, sensitive man who had many of the qualities of the homosexual male. (Bronski 152)”

Homosexual men discovered in this environment new freedoms to get close to one another without arousing suspicion.

“Though the military officially maintained an anti-homosexual stance, wartime conditions nonetheless offered a protective covering that facilitated interaction among gay men (d’Emilio 26)”

Bob Ruffing, a chief petty officer in the Navy described this freedom as follows, ‘When I first got into the navy—in the recreation hall, for instance— there’d be eye contact, and pretty soon you’d get to know one or two people and kept branching out. All of a sudden you had a vast network of friends, usually through this eye contact thing, some through outright cruising. They could get away with it in that atmosphere. (d’Emilio 26) ”

Another wrote about their experience serving in the navy in San Diego, “‘Oh, these are more my kind of people.’ We became very chummy, quite close, very fraternal, very protective of each other. (Hegarty 180)”

Some spaces within the army became queer as well. The USO put on shows for soldiers, and since they could not find women to play parts, the men often dressed in drag. “impersonation. For actors and audiences, these performances were a needed relief from the stress of war. For men who identified as homosexual, these shows were a place where they could, in coded terms, express their sexual desires, be visible, and build a community. (Bronski 148)”

“Here you see three lovely “girls”

With their plastic shapes and curls.

Isn’t it campy? Isn’t it campy?

We’ve got glamour and that’s no lie;

Can’t you tell when we swish by?

Isn’t it campy? Isn’t it campy?”

The words camp and swish being used in the gay subculture and connected to effeminate gay men.

I would have to assume, more than a few transwomen gravitated to these spaces as well.

Even the battlefield itself provided opportunities for gay fraternization. A beach in Guam for example became a secret just for the gay troops, they called it Purple Beach Number 2, after a perfume brand.

This homoerotic space was not confined to the military, but spilled out into civilian life as well.

Donald Vining was a pacifist who stated bluntly his homosexuality to the recruitment board as his mother needed his work earnings, and if you wanted be a conscientious objector you had to apply to go to an objector’s camp. He became something of a soldier chaser, working in the local YMCA and volunteering at the soldier’s canteen in New York he hooked up with soldiers still closeted for a night of passion but many more who were open about who they were.

After the war he was left with a network of gay friends and a strong sense of belonging to a community. It was dangerous tho, he was victim of robberies he could not report because they happened during hook ups, but police were always ready to raid gay bars when they were bored. “It was obvious that [the police] just had to make a few arrests to look busy,” he protested in his diary. “It was a travesty of justice and the workings of the police department (d’Emilio 30).״

Now it might seem odd he was able to plug into a community like that, but over the war underground gay bars appeared across the country for their new clientele. Even the isolated Worcester Mass got a gay bar.

African American men, barred from combat on the front lines, were not entirely barred from the gay subculture in the cities. For example in Harlem the jazz bar Lucky Rendevous was reported in Ebony as whites and blacks “steeped in the swish jargon of its many lavender costumers. (Bronski 149)”

The Other War: Facing Homophobia

“For homosexual soldiers, induction into the military forced a sudden confrontation with their sexuality that highlighted the stigma attached to it and kept it a matter of special concern (d’Emilio 25)”

“They were fighting two wars: one for America, democracy, and freedom; the other for their own survival as homosexuals within the military organization. (Eaklor 68)”

Once they were in, they fell under Article 125 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice: “Any person subject to this chapter who engages in unnatural carnal copulation with another person of the same or opposite sex or with an animal is guilty of sodomy. Penetration, however slight, is sufficient to complete the offense.”

Penalties could include five years hard labour, forced institutionalization or fall under the dreaded Section 8 discharge, a stamp of mental instability that would prevent you from finding meaningful employment in civilian life.

Even if one wanted nothing to do with fulfilling their desires it was still essential to become hyper aware of your presentation and behaviour in order to avoid suspicion.

Coming Home to Gay Ghettos

“The veterans of World War II were the first generation of gay men and women to experience such rapid, dramatic, and widespread changes in their lives as homosexuals. Bronski 154”

After the war many queer servicemen went on to live conventionally heterosexual lives. But many more returned to a much queerer life stateside.

Bob Ruffing would settle down in San Francisco. The city has always been a safe harbour for queer Americans, made more so as ex servicemen gravitated to its liberated atmosphere. The port cities of New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles became the prime destinations to settle. Vining’s partner joined him in New York, where they both immersed themselves in the gay culture.

Other soldiers moved to specific neighborhoods known for having small gay communities. San Francisco’s North Beach, the west side of Boston’s Beacon Hill, or New York’s Greenwich Village. Following the war the gay populations of these cities increased dramatically.

The cities offered parks, coffee houses and bars which became queer spaces. And drag performance, music and comedy became features of this culture.

These veterans also founded organizations just for the queer soldiers. In Los Angeles the Knights of the Clock provided a space for same sex inter racial couples. In New York the Veterans Benevolent Association would often see 400-500 homosexuals appear at its events.

A number of books bluntly explored homosexuality following the war, such as The Invisible Glass which tells the story of an inter racial couple in Italy,

“With a slight moan Chick rolled onto his left side, toward the Lieutenant. His finger sought those of the officer’s as they entwined their legs. Their faces met. The breaths, smelling sweet from wine, came in heavy drawn sighs. La Cava grasped the soldier by his waist and drew him tightly to his body. His mouth pressed down until he felt Chick’s lips part. For a moment they lay quietly, holding one another with strained arms.”

Others like Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar (1948), Fritz Peters’s The World Next Door (1949), and James Barr’s Quatrefoil (1950) explored similar themes.

In 1948 the Kinsey Report would create a public firestorm by arguing that homosexuality is shockingly common. In 1950 The Mattachine Society, a secretive group of homosexual Stalinists launched America’s LGBT movement.

References:

Michael Bronski “A Queer History of the United States”

John D’emilio “Coming Out Under Fire”

Vivki L Eaklor “Queer America: A GLBT History of America”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Lesbians

In 1947 General Eisenhower told a purple heart winning Sargeant Johhnie Phelps, “It's come to my attention that there are lesbians in the WACs, we need to ferret them out”.

Phelps replied, “"If the General pleases, sir, I'll be happy to do that, but the first name on the list will be mine."

Eisenhower’s secretary added “"If the General pleases, sir, my name will be first and hers will be second."

Join me again May 17 to hear the story of America’s Lesbians during the war.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

john d’emilio, capitalism and the gay identity. we can’t turn the clock back to some mythic age of the happy family; we have to create our own.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

october wrap-up

stuff I read in october 2020, for fun and for school, even if I didn't finish it. too bad I didn’t do any of the spooky halloween reading I was planning to!

entire books:

housekeeping, marilynne robinson

daisy jones & the six, taylor jenkins reid

the seven husbands of evelyn hugo, taylor jenkins reid

the prince, machiavelli

the crying of lot 49, thomas pynchon

selections from:

zami: a new spelling of my name, audre lorde (hope I can read the rest of this over thanksgiving break!)

dr. faustus, marlowe

institutes, calvin

the lavender scare, david johnson

coming out under fire: the history of gay men and women in the second world war, allan bérubé

sexual politics, sexual communities: the making of a homosexual minority, 1945-1970, john d’emilio

I cannot remember anything else so I guess I might come back and add more later on!

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

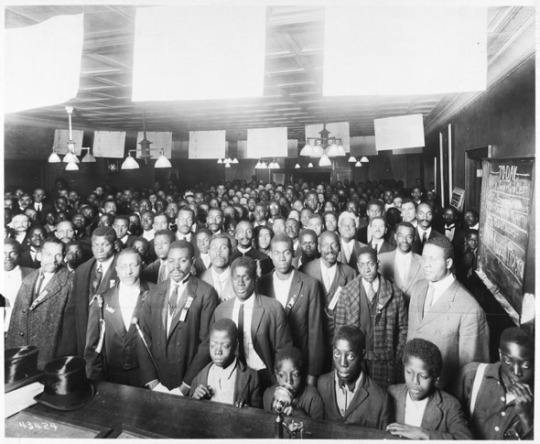

Origins of the ballroom culture that are seen today can be traced back to the 1920s. A seminal reading by Eric Garber wrote that ‘at the beginning of the twentieth century, a homosexual subculture uniquely Afro-American in substance, began to take shape in New York's Harlem. Throughout the so-called Harlem Renaissance period, roughly 1920 to 1935, black lesbians and gay men were meeting each other on street corners, socializing in cabarets and rent parties and worshipping in church on Sundays. Creating a language, a social structure, and a complex network of institutions’ (1990:318). One of these institutions also being, ‘balls’.

Garber goes on to explain that ‘the key historical factor in the development of the lesbian and gay subculture in Harlem was the massive migration of thousands of Afro-Americans to northern urban areas after the turn of the century’ (1990:319). With the large majority of Afro-Americans living in rural southern states at the end of American slavery, one of the most significant shifts in population occurred when many moved to developed northern urban areas with the prospects of factory work, creating large communities of black Americans, also now known as the ‘Great Migration’ (figure one). One of the largest communities formed was in Harlem. With a celebration of progress and possibilities and described as ‘spiritual emancipation’ by Rhodes scholar, Alain Locke, Harlem soon became a centre of black music and art.

Self-named as ‘The New Negros’ (figure two), Garber goes on to explain that ‘[the] movement created a new kind of art. Harlem, as the New Negro Capital, became a worldwide centre for Afro-American jazz, literature, and the fine arts. Many black musicians, artists, writers, and entertainers were drawn to the vibrant black uptown neighbourhood’ (1990:319). And with this art also came a growing homosexual community.

Esther Newton, American cultural anthropologist, argues that ‘homosexual communities are entirely urban and suburban phenomena. They depend on the anonymity and segmentation of metropolitan life’ (1972:21). It could be said that this creation of an urban settlement for black Americans allowed for the anonymous growth of the black homosexual community and for ‘homosexual behaviour’ to become ‘homosexual identity’. This new, young urban artistic setting ‘[..] made possible the formation of urban communities of lesbian and gay men and [..] of a politics based on a sexual identity’ (D’Emilio 1993:470).

D’Emilio, John (1993) Capitalism and Gay Identity. In The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, ed. Henry Abelove, Michèle Aine Barale and David M. Halperin. New York: Routledge, pp. 467-476.

Garber, Eric (1990) A Spectacle in Colour: The Lesbian and Gay Subculture of Jazz Age Harlem. In Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past. New York: Penguin, pp. 318 – 331.

King Howes, Kelly (2001) ‘Yes! It Captured Them ....': The Performing Arts. In Harlem Renaissance, ed. by Christine Slovey and Kelly King Howes. Detroit: Gale, pp. 69-103.

Locke, Alain (1925) Enter the New Negro. In Survey Graphic, vol lll.

Newton, Esther (1972) Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Photo 1: Woodward (1921) Union Terminal Railroad Depot Concourse, black & white photoprint, 8x10 in. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory.

Photo 2: Unknown (1920) UNIA Parade, organized in Harlem, 1920. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library.

Photo 3: Unknown n.d. Webster Hall hosting a drag ball during the 1920s. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay here’s my post about my research so far, under the cut bc I think this might get long:

-after WWII, there was this huge conservative movement as men returned to the workforce and women went back to the home, gender roles had a bit of a whiplash and got much more rigid again

-at the same time, America shifted from a fear of nazi germany to a fear of communist russia (i’m sure you’ve all heard of the red and lavender scares)

-in the earlier days of rooting out communist spies and those of poor moral character in the government, there was a testimony from an Under Secretary (who’s name I forget) that said most of the near 100 employees recently fired for “moral turgitude” were homosexual

-republicans jumped on this, and made it a big partisan issue as part of their critique of the Truman administration (he’s not doing enough to rid our government of these “deviants”)

-I have a few examples of republicans being bitches but I won’t get into it, the point is eventually the senate gave in to the pressure and issued an investigation

-i’m not going to go into detail on the lavender scare because it’s not actually very important to my thesis, basically what you need to know is the government and the press ramped up this issue 1000% (it was a good way to get people out of the way too and ruin their careers forever too)

-police harassment of homosexuals began in earnest in the early 50s, and even petty criminals would target them because what are they gonna do, go to the police?

-basically this is part of my intro: establishing the attitude towards homosexuals of the time (early 50s) and how they felt about themselves as well (bad. everything society was saying, internalized. most gay people felt as if this was their personal issue, a disease or just a sin)

-my first advocacy group I’ll bring in is the Mattachine Society: formed int he early 50s by Harry Hay and some of his communist gay friends, haven’t gotten very far on them yet but around the mid-50s Hay was kicked out of his own group, the post-Hay Mattachine society will be very important later on as a clear turning point after Stonewall

-the Mattachine Society recognized something very important: most gay people didn’t believe they were a minority group. They either were too terrified to or didn’t want to fight for their rights, they barely even recognized themselves. We’re still in one of the most dangerous times to be gay in America, I didn’t go into it in great detail but it’s extraordinarily depressing. Like I was just sitting in the library trying not to cry.

-very first steps were just reflecting on the homosexual experience, figuring out what united people, figuring out why they faced oppression, the early years was just lots of small group discussion in apartments

-i’m skipping ahead a bit to One, INC, I know even less about them than Mattachine but they are important as one of the Big Three (as i’m calling them) of the early homophile movement. They were a group who split off from Mattachine because they wanted to publish a newspaper, and eventually they formed their own group as well. Mattachine also eventually began to publish a newspaper in response. The two were on uneasy terms at the best of times, as far as I can tell, and had ideological differences that to be completely frank I don’t remember, best guess it was about how they felt about homosexuality and internalization of society’s prejudices (self-hatred vs self-worth type thing, but a lot more complex)

-the last group is the Daughters of Bilitis: formed by middle class white women who didn’t want to have to be a part of the bar scene to be in a safe space (note: they fucking hated the working class, femmes, and butches, and tried to distance themselves as much as possible from them, secondary marginalization and all that jazz)

-they were big on “politics of respectability”, which meant basically changing yourself to make society like you, they also encouraged members to participate in scientific studies to further the understanding of homosexuality

-they too had a newspaper: The Ladder. Most of these newspapers were filled with about what you’d expect: stories, poetry, opinion pieces, advice, news, etc

-DOB was interesting because they were for lesbians, and while the other two groups were technically for all homosexuals, they were majority men. The DOB had some changes over the years, I believe it was the mid or maybe later 50s that they worked together with Mattachine, but they eventually would become more women’s rights based as that movement took off in the 60s. They were not a group for lesbians, but rather a group interested in lesbian rights. Mattachine would also distance themselves from homosexuality like this, trying to get on society’s good side

-have yet to research the 60s, but I shall leave you with an interesting fact about Stonewall, or at least it’s very interesting to my thesis that it marked a difference in gay rights advocacy: The New York Chapter of the Mattachine Society wanted to hold a candle light vigil in the park, but the younger generation deemed it not enough after 3 days of rioting. Soon after Stonewall we would see the formation of groups like the Gay Liberation Front, composed of the “new guard” who were, to boil it down to the basics, more out and proud, and one year later there would be the first pride

I didn’t have my notes with me for any of this, all just off the top of my head, and I tried to cut it down to the basics so you wouldn’t have to read what basically is going to be the first five pages of my essay

Sources:

Law and the Gay Rights Story by Walter Frank (if you’re interested in this stuff read this book, super great and covers a lot of the subjects I only touch on in my essay)

Political Advocacy and Its Interested Citizens: Neoliberalism, Postpluralism, and LGBT Organizations by Matthew Dean Hindman

From Accommodation to Liberation: A Social Movement Analysis of Lesbians in the Homophile Movement by Kristin Esterberg

Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970 by John D’Emilio

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unessay Project (Janis Troeung)

A Blog About My Learning Journey While Crafting My Working Theory of Family

Preface:

The purpose of this blog is to explain my thought processes as I developed my working theory of family. Although I describe this blog as “my learning journey while crafting my working theory of family”, it is by no means an exhaustive account of everything that I have learned throughout this course.

Organization of Blog:

I will first begin by explaining my initial thoughts on family (prior to taking the course), my current working theory (as of week 5), my thought processes of how I went from my initial understanding of family to my current understanding of family, my lived experience of family in relation to my working theory, and conclude with my final notes on the hesitations and confusions that remain with me.

My Initial Thoughts on Family:

Prior to taking this course, this is what I had understood as a ‘standard’ family:

“Family is a concept that many Westerners have grown up to understand as a nuclear family that consists of cisgendered heterosexual parents with one or more biological children. Typically, the dad is considered the ‘breadwinner’ (a person who provides the main source of income for their family) while the mom is a housewife. Although the mom may have a job, the mom is still considered responsible for taking care of household responsibilities such as washing dishes, doing laundry, and taking care of the children (because their income is typically lower than their husband’s). In some cases, people can call other people who are not biologically related to them as ‘family’. This act of calling non-biological kin “family” is usually done when the individual feels a sense of closeness, care, and/or trust with the person(s) they are calling family.”

My Current Working Theory of Family (Week 5):

Family is a non-static concept, and peoples’ perception of family will change throughout time as they are continually learning about what are now currently understood as “alternative” or “non-normative” families. For the purposes of clarification, I am describing “alternative” or “non-normative” families as families that do not adhere to the stereotypical understanding of family which many westerners have come to understand as a family that consists of cisgendered, heteronormative parents with one or more biological children. I believe that as time progresses, this concept of a nuclear family will no longer be understood as the absolute norm and that “alternative/other” families (i.e. families that have LGBTQ parents and/or adoptive or surrogate children) will become more normalized and understood than they currently are.

How Did I Get To My Current Working Theory of Family?:

During the first week of the course, James Baldwin’s “Letter to My Nephew” (1962) reinforced what I had initially understood about family. In his letter, he forewarned his nephew about the harshness of the world and the systemic racism that his nephew will face as a Black American (p. 2). Although it is not explicitly mentioned within the article, the reader of the letter can sense the care and compassion Baldwin holds for his nephew. In fact, by simply understanding the context that this is a letter written by an uncle addressing his nephew, the reader can feel a heightened sense of positive connotations that are associated with family in the weight of Baldwin’s words. After reading this article, the reader can see that Baldwin is a source of wisdom, knowledge, comfort, protection, and love for his nephew. Despite that this letter was written over fifty years ago, Baldwin’s words are still held true in today’s context as Black Americans are still marginalized and are facing apparent systemic racism today. This article shows how many institutions within America are marginalizing and discriminating against people of color, especially Black Americans, (and later I learned how this affects Black American families in terms of policy and culture in week two). From this article, I learned that care and compassion are two traits that I heavily associate with the concept of “family”.

In addition to the Baldwin reading in week one, we read Patricia Hill Collins’s article titled “Intersections of Race, Class, Gender, and Nation: Some Implications for Black Family Studies” (1998). From this article, I began to gain a better understanding of how to analyze and understand family from a sociological perspective. This reading helped me realize that there are many depths and layers to understanding families and how they function within societies. In Collins’s (1998) article, I began to better understand intersectionalities and that factors such as race, gender, and social class should all be taken into consideration when analyzing families, family policies, and familial organization (p. 33). There is not one particular form of family that is considered “normal” and each family is unique in their own sense. Collins (1998) believes that scholars should dismantle the hegemonic idea that the nuclear family is considered the “norm“ and that anything besides that is abnormal (p. 30). In fact, this is the rhetoric that I found many of the assigned readings were trying to convey, and I believe that if scholars continue to support the dismantling of this hegemonic ideal, that other forms of family can become more recognized, understood, and normalized. To think that there is one dominant or ‘correct’ form of family is narrow-minded and minimizes the lived experiences of other types of family.

During week two, we read Brittany Pearl Battle’s article titled, “Deservingness, Deadbeat Dads, and Responsible Fatherhood: Child Support Policy and Rhetorical Conceptualizations of Poverty, Welfare, and the Family” (2018). From this article, I began to understand how culture and policy are interrelated and how they are constantly influencing one other (p. 444). This helped me better understand Baldwin’s letter to his nephew and why Black Americans are still facing oppression today. Many government officials and politicians have been white, middle to upper class men, who have reinforced the notion that families should consist of a dad who is the primary source of income for his family, a mom who takes care of the children, and the children who will grow old and take care of their parents one day. Throughout different presidencies, Battle has analyzed these different presidents’ rhetoric and how that has shaped gender roles within the family which has consequently affected family culture. Many institutions within the U.S. have perpetuated hegemonic ideals which has led to the oppression of Black Americans who are constantly racially profiled, and has thus led to the marginalization of Black Americans. In my opinion, a lot of the rhetoric surrounding around the idea that ‘dads should be the primary source of income for the family’ while the mom should be the caretaker is outdated and seeks to place blame on fathers instead of holding the government reliable for seeking better ways to support fathers and their families. Due to the constant racial profiling that Black Americans face, many Black men are incarcerated and put into jail which thus perpetuates the idea that Black men are put into jail because they “commit more crimes”, which echoes the false sentiment that Black fathers are bad because they cannot provide for their children due to their incarceration. Of course, this is an oversimplification of how intersectionalities work and how culture and policy influence each other which has led to the marginalization of Black Americans, but I hope that I have illustrated a comprehensible image of how policy has affected and continues to marginalize and oppress those who are considered different from those in power (i.e. officials in government who are typically white, middle to upper class men), whether it be through race, gender, or social class. From this reading, I also realized that hegemonic structures have stayed in place, because people with power and influence perpetuate this hegemony as the norm or something that is desired. However, if more people in power spoke up against it or supported those who do not conform to the hegemonic standards, other forms of structures can become more normalized, regulated, and/or accepted.

Lastly, during week four, we read Katie L. Acosta’s “We Are Family” (2014) which provides a contrast from Baldwin’s letter to his nephew. Although families are thought of as a resource for care and love, sometimes family may reject one another based on individual family members’ contrasting ideologies. From Acosta’s interviews, we learn how Latinx women who are considered ‘sexually non-conforming’ are shunned for not following hegemonic ideals of partnership. Despite the disapproval that they receive from their parents, many of these women are still hoping that their parents will one day show more approval/acceptance for their romantic partners and their relationships (p. 45). This illustrates how dominant ideas can influence how family members perceive and treat other members of their family and how dominant ideologies can be internalized as ‘the ultimate good’ or ‘correct way of living’. Although capitalism has created an opportunity for those who identify as LGBTQ, gay, queer, trans, and non-binary to come out and identify with their preferred pronouns (as explained by John D’Emilio in his article “Capitalism and Gay Identity” (1983)), many people today are still prejudiced against non-hegemonic forms of family. Based on my theory, I do believe (and wishfully hope) that as time passes, these hegemonic standards will slowly become whittled down and that people will understand that they do not necessarily need to conform to hegemonic standards of family to have a happy, fulfilling life. Nuclear families may have been necessary for survival in the past, but that is no longer the case, and people around the world are creating different types of families that could not have been imagined of in the past.

My Lived Experience of Family:

I come from an Asian household where my dad is Cambodian and my mom is Chinese. My parents had three children - two sons and one daughter (me). I would consider my family situation to be understood as “normal” by the standards of public perception, but a part of me has always wondered if my parents would have gone through a different path of creating a family if they had lived under different circumstances (i.e. conditions where hegemonic understandings of families were not reinforced as standard or a necessity for a purposeful life). My parents are first generation immigrants, and they came to America so that they could start a family in better conditions than their home countries. Since my parents were first generation immigrants, it meant that they had spent a lot of time away from home and were working so that they could provide adequate financial support for their children. Therefore, there were many times where I felt like I did not feel the same warmth and comfort of family that I felt many peers around me felt, because my peers’ parents appeared to be more involved in their lives. There were many times when I would go to the homes of my friends and their parents would welcome me and feed me. In some cases, they treated me as if I were their own daughter and called me “family”. This was when I realized that family does not necessarily have to consist of people who you share the same blood with, and that actions and words of people can make you feel like “family” more than your own biological kin.

From my personal experiences I believe that, as time progresses, people will not immediately think of biological kin as the primary source of familial care and love. There are instances when people who are not related to you can feel more like “family” to you than your own biological family based on how they treat and care for you. In that sense, I do believe that there will be a shift in perception on what it means to be “family” with one another, and that other families that are currently understood as “non-traditional” will become more apparent, recognized, and accepted. In fact, there is research that shows that companies are trying to create a culture of “work families” to provide a sense of comfort and joy for their employees. Work families, which are another byproduct of capitalism, could provide familial comfort for employees who may or may not have familial support from their biological kin.

Remaining Confusions and Hesitations:

Although I feel that I have learned a lot through the lectures and readings I have by no means fully understood all the concepts that were presented. Many of the articles that we have read in this course have addressed how there is a greater need for diversification in family studies that do not focus on white, middle-class, hegemonic ideals of family. However, there are so many depths and layers to understanding how institutions within societies are influencing families and family structure. I do not think that it is possible to conduct proper, well-done studies on every single possible family structure in this world; therefore, I am confused about how scholars can continue to shed light on the multitude of different family types without overgeneralizing the experiences of current marginalized families. I am also hesitant about how we can truly learn from these studies when each individual’s understanding of their family and the world is a unique experience in of itself and outsiders can never truly understand their experiences and perspective.

Works Cited:

Acosta, K. L. (2014). We are family. Contexts, 13(1), 44-49.

Baldwin, J. (1962). A letter to my nephew. The Progressive, 1.

Battle, B. P. (2018). Deservingness, Deadbeat Dads, and Responsible Fatherhood: Child Support Policy and Rhetorical Conceptualizations of Poverty, Welfare, and the Family. Symbolic Interaction, 41(4), 443-464.

Collins, P. H. (1998). Intersections of race, class, gender, and nation: Some implications for Black family studies. Journal of comparative family studies, 29(1), 27-36.

D’Emilio, J. (1983). Capitalism and gay identity. Families in the US: Kinship and domestic politics, 131-41.

1 note

·

View note