#John Coltrane at the Village Vanguard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Capturing History in Sound: "Duke Ellington at Fargo, 1940 Live"

Introduction: “Duke Ellington at Fargo, 1940 Live” is more than just a live recording—it’s a piece of jazz history, capturing the unique spirit of Duke Ellington’s orchestra during a pivotal moment in their journey. Recorded on November 7, 1940, at the Crystal Ballroom in Fargo, North Dakota, this album provides listeners with a rare window into Ellington’s live performances, away from the…

#Ben Webster#Benny Goodman#Benny Goodman at Carnegie Hall#Classic Albums#Cootie Williams#Duke Ellington#Duke Ellington at Fargo 1940 Live#Duke Ellington Orchestra#Jack Towers#Jazz History#John Coltrane at the Village Vanguard#Johnny Hodges#Ray Nance#Rex Stewart#Richard Burris#Tricky Sam Nanton

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

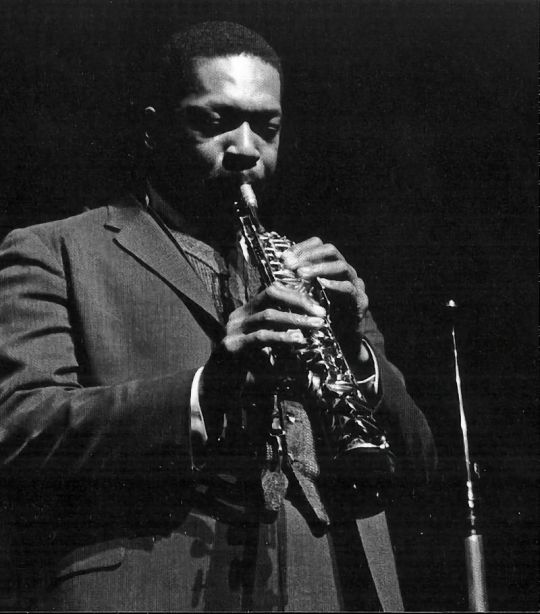

John Coltrane, Village Vanguard, November, 1961

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

We're diving into the iconic world of jazz albums, and we want to hear from YOU! 💬 Whether you’re a seasoned jazz enthusiast or just getting started, these albums are legends in the genre. But we’re curious—which one resonates with you the most? 🤔

Your chance to VOTE and be heard! And if we missed your favorite, let us know in the comments. 🎶

#Jazz#KindofBlue#ALoveSupreme#HerbieHancock#MingusAhUm#BillEvans#JazzLegends#JazzCommunity#MusicPoll#Jazz music#John Coltrane#Head Hunters#Miles Davis#Charles Mingus#Bill Evans#Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz#Jazz Art#Some place it's always Monday...#Best Jazz Album Ever#Sunday at the village vanguard#Music Monday#tumblr tuesday#Music on tumblr

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

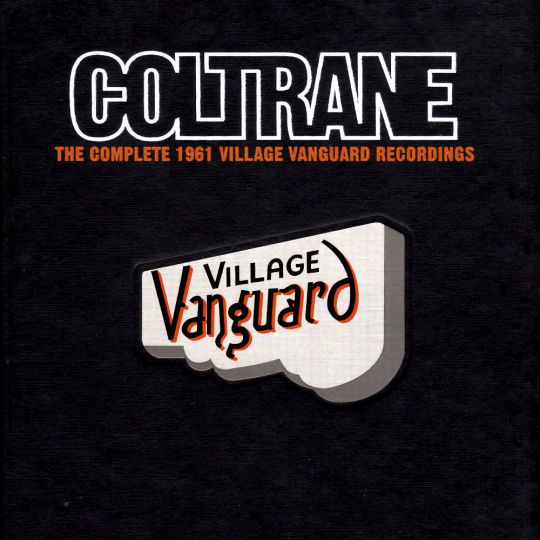

#john coltrane#village vanguard recordings#impressions#mccoy tyner#elvin jones#reggie workman#eric dolphy

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back home.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Awesome

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

(Left to Right) Pharoah Sanders, John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane, Jimmy Garrison and Rashied Ali outside the Village Vanguard, New York, May 28, 1966. Photo cover of the album "Live at the Village Vanguard Again" 1966. Photo © Chuck Stewart

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

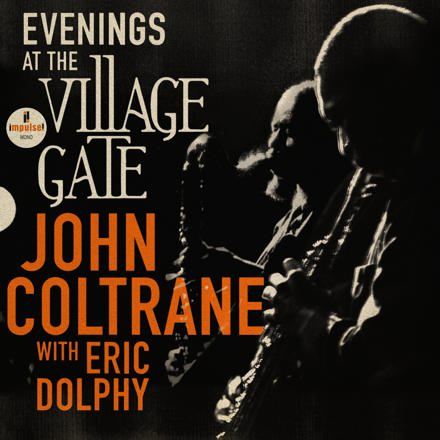

John Coltrane Reissue Review: Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy

(Impulse!/UMe)

BY JORDAN MAINZER

Not even two years after A Love Supreme: Live in Seattle saw the light from Joe Brazil's private collection, a new John Coltrane treasure has been given to us, unearthed this time by accident. A Bob Dylan archivist, scouring through the archives of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, found an August 1961 recording of John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy at Greenwich Village's long-shuttered Village Gate. While Coltrane's November performances from the same year at the Village Vanguard have long been available, either as part of his 1962 live album or a 1997 box set, this collection shows some familiar players a bit rougher around the edges. Future Nina Simone and Dylan engineer Richard Alderson, who wanted to test a newly found single ribbon microphone, decided to record the set, and everything from McCoy Tyner's restrained piano to, well, the overall sound quality, has the vibe of a group of geniuses still figuring things out, a fascinating snapshot in an ever-changing time in jazz.

In an era where our most revered artists take seemingly forever to release new albums, it's hard to fathom just what luminaries like Coltrane did back then, and the rapid pace of change they faced in a burgeoning music industry. In March, he released My Favorite Things on Atlantic, which yielded surprising hits in adaptations of George Gershwin's "Summertime" and Rodgers and Hammerstein's "My Favorite Things", the latter of which received significant radio airplay. Two months later, his Atlantic contract was bought by Impulse! While he kept Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones in his band, he replaced bassist Steve Davis with a young Reggie Workman and brought on multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy, forming the basis of a live quintet. His studio ensemble grew even larger on the first album he recorded for Impulse!, Africa/Brass, also one of his first to employ two bass players. Eventually, though, he'd settle into the Classic Quartet, Jimmy Garrison replacing Workman for the next several years, the four producing stone cold classics like, yes, A Love Supreme. It's impossible to separate this context when listening to Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy in all of its rawness.

Really, Evenings at the Village Gate is a true moment in time and one of arguable significance, though listening to it is a fascinating exercise. You constantly find yourself wishing you were there to witness it, watching an audience in real time react to where you know jazz would end up. As Jones' pattering drums and Workman and Tyner's steady bass and piano introduce "My Favorite Things", Dolphy subtly flutters his clarinet. Six minutes in, Coltrane announces himself with a brawny saxophone line before blasting streaks of notes above the band. When he very occasionally returns to the song's main refrain, it's like a sigh of relief before he embarks on another freeform journey. Sometimes, you can hear an audience member clapping, thinking his solo has finished, but he keeps going. Dolphy offers a similarly tattered solo on Benny Carter's "When Lights Are Low", while the rest of the band lurches. Tyner's solo, for example, is sprinkled but so low in the mix you can almost clearly hear background chatter in the club, and you can definitely decipher Workman's plucks. The band is risky and adventurous, unafraid to fail.

The final three tracks performed would eventually be recorded, including "Impressions", a Coltrane composition first set to tape in 1962. The version on Evenings at the Village Gate is an early run-through the way a lot of jazz instrumentalists do today. On one hand, hearing him breathlessly and immediately whittle away at schemas of jazz must have been thrilling. On the other, compared to the live versions of the song from months later, on this one, Coltrane embraces true chaos rather than controlled chaos. Only Jones and Tyner are truly honed in here, the former shining with his dexterousness throughout and underrated dynamism in his be-bop duet with the latter. If you've always thought Coltrane's recording of "Greensleeves", meanwhile, sounds a little bit like "My Favorite Things", Tyner somewhat interpolates the latter song as Jones' drum fills pervade the performance. Tyner's two-handed solo mid-way through simultaneously showcases the song's theme and his own phrasing, while Coltrane and Dolphy enter much later, as if they've been stockpiling on reserves before gradually taking the tune to dizzying new heights.

If there's a true highlight on Evenings at the Village Gate, it's of course the only known recorded version of Africa/Brass' "Africa". Art Davis fills in on additional bass drones, with Coltrane on tenor saxophone, and the song feels like the most the band had been in sync all night. Perhaps that's because there's nothing else to compare it to, but the performance is still thrilling taken on its own, from Jones' raindrop pitter patters to Tyner's unshakeable refrain. Coltrane and Dolphy give way to the rest of the band for a while, and the tune slowly ascends as they tease a return, first giving Jones his due with a rolling solo and then actually returning to rapturous applause, skronking and squeaking away. You have to think that some members of the audience had no conception for what they just saw. You also have to think the set made them want to dive in further.

youtube

#album review#john coltrane#new york public library for the performing arts#Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy#eric dolphy#impulse!#ume#a love supreme: live in seattle#joe brazil#bob dylan#village gate#village vanguard#nina simone#richard alderson#mccoy tyner#my favorite things#george gershwin#atlantic#elvin jones#steve davis#reggie workman#africa/brass#jimmy garrison#a love supreme#benny carter#art davis#richard rodgers#rodgers and hammerstein#oscar hammerstein#evenings at the village gate

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pharoah Sanders, John Coltrane, Alice Coltrane, Jimmy Garrison & Rashied Ali outside the Village Vanguard, New York, May 28, 1966, photographed by by Ch. Stewart.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joe Lovano's "Quartets: Live at the Village Vanguard" — A Masterpiece of Jazz Improvisation

Introduction: Jazz has always been about pushing boundaries, reinventing tradition, and creating moments of pure spontaneity. Few live recordings encapsulate this spirit better than Joe Lovano’s “Quartets: Live at the Village Vanguard.” Released in 1995, the double CD stands as a testament to Lovano’s artistic prowess and his ability to thrive in diverse musical settings. Featuring two…

#Anthony Cox#Bill Evans#Billy Hart#Charles Mingus#Christian McBride#Classic Albums#Eddie Boyd#Gerry Mulligan#Gordon Jenkins#Jazz History#Joe Lovano#John Coltrane#Lewis Nash#Miles Davis#Mulgrew Miller#Ornette Coleman#Quartets: Live at the Village Vanguard#Sonny Rollins#Thelonious Monk#Tom Harrell

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Storia Di Musica #347 - Sonny Rollins, Tenor Madness, 1956

Le Storie Di Musica toccheranno il traguardo delle 350 puntate questo mese. Come ormai da prassi, il numero tondo è dedicato ad un disco di Miles Davis. E questa volta, in ossequio al filo rosso degli album legati tra loro, ho deciso di raccontare il rapporto tra Davis e una grande etichetta discografica, la Prestige Records. La Prestige fu fondata da Bob Weinstock nel 1949: appassionato di musica jazz, vendeva dei dischi per corrispondenza in maniera così incisiva che ben presto affittò un locale e lo trasformò in un grande negozio di dischi, il Jazz Record Center, sulla quarantasettesima strada di New York. Frequentando i locali jazz che lì vicino iniziavano a diventare famosi, legò con molti musicisti fino a fondare prima la New Jazz Records che dopo pochi mesi diventa la Prestige Records. Weinstock è stato un personaggio leggendario, dalle mille manie, alcune delle quali racconterò in questi appuntamenti novembrini, ed è stato negli anni '50 uno dei fari della musica jazz mondiale con la sua etichetta indipendente, insieme alla Blue Note, alla Riverside, alla Impulse! prima che anche i grandi gruppi discografici entrassero nel jazz in maniera decisa.

Weinstock era oltre che un appassionato un grande uomo d'affari, capace di intuire le potenzialità degli artisti e di essere per loro trampolino di lancio e di ottimizzare tempi e costi delle produzioni: pochissime prove per le registrazioni, e leggenda vuole che si registrasse due volte sui nastri di alcune take per risparmiare, leggenda nata dal fatto che per quanto la produzione Prestige fosse numericamente grandiosa, esistono pochissime alternative takes dei loro lavori. Nonostante come ingegnere del suono ci fosse una leggenda: Rudy Van Gelder, che non lavorava solo per lui ma anche per la Blue Note, famoso per la sua accuratezza e maniacalità. Le prime registrazioni avvenivano nel garage della casa di famiglia di Hackensack, nel New Jersey, luogo che divenne mitico tanto che Thelonious Monk dedicò al grande ingegnere un brano, Hackensack, per poi spostarsi di qualche km a Englewood Cliffs, sempre nel New Jersey.

In quello studio a Hackensack Sonny Rollins registra il 24 Maggio del 1956 il disco di oggi. Rollins all'epoca è già riconosciuto un gigante del sassofono, tanto che è famosa il commento di Max Gordon, leggendario proprietario del jazz club più famoso del mondo, Il Village Vanguard, che sosteneva: I critici e gli appassionati hanno pareri molto discordi sulla bravura di alcuni musicisti jazz, ma non su Sonny Rollins. Lui è il più grande, il più grande sax della sua generazione. Theodore Walter Rollins nasce a New York nel 1930 da una famiglia di origini caraibiche, i cui "suoni" influenzeranno la sua carriera futura. Fa un apprendistato breve ma intensissimo, suonando con i più grandi: J.J Johnson, Monk, Bud Powell, Max Roach e soprattutto Miles Davis e Charlie Parker. È il primo che trasporta la rivoluzione del bop sul sax tenore. Con Davis dimostra anche le sue già ottime capacità compositive scrivendo pezzi diventati famosi, come Airgin e Oleo. Però ha un difetto: ad un certo punto sparisce, per i motivi più strani. Nel 1954 si ritira a Chicago, per non cadere in tentazione tra soldi e droga, per continuare a studiare facendo lavori manuali. Quando ritorna a New York, suona per la Prestige in uno dei primi 33 giri del jazz, Dig. Nel 1955, tornato nel gruppo di Davis, poco prima di un'importante serie di concerti al Teatro Bohemia, sparisce di nuovo, stavolta per disintossicarsi. Ritorna nel 1956, quando sempre l'amico Roach lo scrittura per un disco portentoso: Sonny Rollins Plus 4 è all'apice della creatività, tanto che ancora come innovatore impone nel jazz il tempo in tre quarti (la storica Valse Hot). Nel frattempo però il suo posto nel gruppo di Davis è preso da un giovane che di lì a poco diventerà un gigante, John Coltrane, ma Davis gli vuole bene e per delle registrazioni del 1956 per la Prestige gli offre la sua sezione ritmica, che nel jazz è ricordata come "The rhythm section" per quanto iconica e grande è stata, e con questa registra il disco di oggi. Rollins è insieme a Red Garland al pianoforte, Paul Chambers al contrabbasso e Philly Joe Jones alla batteria quando inizia a suonare Tenor Madness, che contiene nella title track un incontro unico ed eccezionale. Essendo lì per una sessione con il quintetto di Davis, in quello che diventerà il più famoso chase della storia del jazz, John Coltrane si unisce a Rollins in quel brano, da allora uno dei capisaldi del jazz. Cos'è però un chase? è un incontro dove due strumentisti colloquiano con lo stesso strumento su un dato canovaccio, una sorta di dialogo musicale dove si fronteggiano a suon di assoli. Tenor Madness è un piccolo blues, che si rifà a Royal Roost di Kenny Clarke and His 52nd Street Boys, registrato nel 1946, ma qui diviene il brano che mette insieme i due più grandi e influenti sassofonisti della storia del jazz, con il timbro squillante e luminoso del primo Coltrane (che debutterà come solista solo l'anno successivo nel 1957) e il suono più cupo e leggero di Rollins, che all'epoca aveva già più esperienza. Il resto di Tenor Madness è altrettanto iconico: When Your Lover Has Gone, classico di Einar Aaron Swan, divenuto famosissimo per la sua apparizione nel film La Bionda E L'Avventuriero del 1931 di Roy Del Ruth e interpretato da James Cagney e Joan Blondell, che solo nel 1956 ebbe una ventina di incisioni; Paul's Pal è un omaggio di Rollins a Paul Chambers, uno dei più geniali bassisti di tutti tempi, uno che ha suonato in almeno 100 capolavori del jazz; My Reverie è la ripresa dell'arrangiamento che nel 1938 Larry Clinton fece si un brano di Claude Debussy, Rêverie, del 1890; chiude il disco una cover spettacolare di The Most Beautiful Girl In The World, opera del magico duo Rodgers and Hart e presente nel musical Jumbo, che trasformava un teatro di Broadway in un mega circo con acrobati, trapezisti e giocolieri durante lo spettacolo. Il disco, un capolavoro, ne anticipa un altro, Saxophone Colossus, dello stesso anno, uno degli apici creativi di quegli anni incredibili e altro gioiello della collezione Prestige.

Rollins fu attivo per la lotta dei diritti civili e politici degli afroamericani, tanco che nel 1958 firma in trio con Oscar Pettiford e Max Roach, il disco The Freedom Suite, uno dei primi album-manifesto sulle discriminazioni razziali del jazz, e continuò ad avere costanti le sparizioni dalle scene. Sempre dovute alle sue dipendenze dalle droghe, la più famosa riguarda un suo disco, il suo maggior successo commerciale, The Bridge del 1962: ancora insoddisfatto della sua musica, decide si andare a suonare sotto il ponte Williamsburg, quello che divide Manhattan da Brooklyn, provando per 12-13 ore al giorno, in tutte le stagioni.

Scontroso (si dice che abbia licenziato il maggior numero di colleghi, più di Mingus), dalla personalità labirintica, non seguì le rivoluzioni degli anni '60 e '70, scriverà ancora grandi album (What's New con Jim Hall, un altro gioiello) e parteciperà con attenzione anche a contaminazioni con altri generi, e famosissimo è il suo assolo per i Rolling Stones in Waitin' On a Friend, da Tattoo You del 1981. È l'ultimo dei grandi a sopravvivere, ritiratosi nel 2012 dalle scene, un gigante che ha segnato un periodo irripetibile della musica.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bootleg of John Coltrane 4tet + Eric Dolphy in Copenhagen 1961

youtube

(English / Español)

Without a doubt, saxophonist John Coltrane's band after he left trumpeter Miles Davis in 1960 is one of the defining groups of jazz, and for the year or so during which multi- instrumentalist Eric Dolphy joined Coltrane on reeds, the band became a phrenic and frenetic powerhouse that shook jazz to its core. Between Dolphy's piercingly distinct sound and Coltrane's newly developed interest in Eastern modalities, as well as the driving force of one of the all-time great rhythm sections—pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones, and bassists Jimmy Garrison or Reggie Workman—this was a band to reckon with.

Recorded on November 20, 1961, mere weeks after the legendary Village Vanguard sessions that got critics' dander up, this album finds the quintet at the Falkonercenter in Copenhagen, playing the first part of a sold-out two act bill (the second act was trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie's band: what a concert!). Here, Workman is still holding down the bass chair, though Jimmy Garrison had likely won himself the spot for future iterations of the Coltrane band with his performance on "Chasin' The Trane" back in New York. Previously made available on vinyl, but only just released in a complete CD form with announcements by presenter Norman Granz, this is a must-have for Coltrane or Dolphy completists.

The album boasts two curiosities that distinguish it from all the other Coltrane recordings available in the marketplace. The first, a pair of rare false starts on "My Favorite Things," prompting an apology from the ever mild-mannered Coltrane to the audience, will likely only interest the true die-hard fan. But a version of Victor Young's beautiful "Delilah," purported to be the only version of the song that Coltrane or Dolphy ever recorded, is a deluxe addition to any fan's collection.

Without a doubt, this would have been an astonishing performance to witness. While Coltrane, Dolphy and McCoy are fantastic as always, part of the pleasure of hearing this band is in the seemingly telepathic give and take between all players. Hearing Coltrane's fire with only hints of the sparks that Elvin Jones is lighting behind him isn't the complete experience. That being said, it's still a lot better than most of what's out there.

Tracks: Announcement by Norman Granz; Delilah; Every Time We Say Goodbye; Impressions; Naima; My Favorite Things (false starts); Announcement by John Coltrane; My Favorite Things.

Personnel: John Coltrane: tenor and soprano saxophones; Eric Dolphy: alto saxophone, flute, bass clarinet; McCoy Tyner: piano; Reggie Workman: bass; Elvin Jones: drums.

Extract text from: allaboutjazz.com / By Warren Allen

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sin lugar a dudas, la banda del saxofonista John Coltrane tras su marcha del trompetista Miles Davis en 1960 es uno de los grupos que definen el jazz, y durante el año en que el multiinstrumentista Eric Dolphy se unió a Coltrane en las cañas, la banda se convirtió en una potencia frenética que sacudió el jazz hasta sus cimientos. Entre el sonido penetrantemente distintivo de Dolphy y el nuevo interés de Coltrane por las modalidades orientales, así como la fuerza motriz de una de las mejores secciones rítmicas de todos los tiempos -el pianista McCoy Tyner, el batería Elvin Jones y los bajistas Jimmy Garrison o Reggie Workman-, ésta era una banda a tener en cuenta.

Grabado el 20 de noviembre de 1961, pocas semanas después de las legendarias sesiones del Village Vanguard que levantaron la polvareda de la crítica, este álbum presenta al quinteto en el Falkonercenter de Copenhague, tocando la primera parte de un programa de dos actos con las entradas agotadas (el segundo acto fue la banda del trompetista Dizzy Gillespie: ¡menudo concierto!). Aquí, Workman sigue ocupando la silla del bajo, aunque Jimmy Garrison probablemente se había ganado el puesto para futuras iteraciones de la banda de Coltrane con su actuación en "Chasin' The Trane" en Nueva York. Anteriormente disponible en vinilo, pero recién editado en CD completo con anuncios del presentador Norman Granz, es un disco imprescindible para los completistas de Coltrane o Dolphy.

El álbum cuenta con dos curiosidades que lo distinguen de todas las demás grabaciones de Coltrane disponibles en el mercado. La primera, un par de raras salidas en falso en "My Favorite Things", que provocaron una disculpa del siempre apacible Coltrane al público, probablemente sólo interesará a los verdaderos fans acérrimos. Pero una versión de la hermosa "Delilah" de Victor Young, que se supone que es la única versión de la canción que Coltrane o Dolphy grabaron jamás, es una adición de lujo a la colección de cualquier fan.

Sin duda, habría sido una actuación asombrosa. Aunque Coltrane, Dolphy y McCoy están fantásticos como siempre, parte del placer de escuchar a esta banda está en el toma y daca aparentemente telepático entre todos los músicos. Escuchar el fuego de Coltrane con sólo indicios de las chispas que Elvin Jones enciende tras él no es la experiencia completa. Dicho esto, sigue siendo mucho mejor que la mayoría de lo que hay en el mercado.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The new weekly Jazz Club section.

Present by mod

Today in New York: the Village Vanguard

The Village has been the birthplace of many renowned jazz artists, and it continues to be a destination of choice for those seeking to experience great jazz music.The Village Vanguard is one of the most renowned and oldest jazz clubs in the city, offering exceptional live music in a intimate atmosphere since 1935.

History that you can beat around the ears of the bartender, maybe not. Better to just order a good whisky .

mod

The Village Vanguard opened its doors on 22 February 1935. Founder Max Gordon opened the club in the basement of a wedge-shaped building on the corner of Seventh Avenue and Waverly Place. It initially provided a stage for a wide range of artists, including folk musician Pete Seeger, whose band The Weavers were the Vanguard's first employees, and the then-unknown singer Harry Belafonte. In August 1949, Mary Lou Williams played the first jazz concert there; her group shared the stage with J. C. Heard's band. From 1957, the Vanguard became a pure jazz club. The Vanguard's artists soon included musicians such as Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Art Blakey.

While the clubs on 52nd Street and Birdland on Broadway closed their doors from the mid-1960s onwards, the Vanguard remained a well-known jazz venue in New York. After Max Gordon's death in 1989, his wife Lorraine took over the business and ran it until her death in June 2018. Since then, her daughter Deborah has taken over the club.

Wikipedia more or less

More not needed insider knowledge:

Recordings from the Village Vanguard

For jazz labels, the words ‘at the Village Vanguard’ are now a guarantee of good sales. They now adorn several dozen covers of recordings by all the major jazz labels, from Blue Note and Riverside to Impulse and Verve, with a total of around 150 recordings to date.

Maxine Sullivan at the Village Vanguard (1947)

Dexter Gordon and Benny Bailey at the Village Vanguard (1977)

1957: Night at the Village Vanguard (Sonny Rollins, Blue Note)

1961: Waltz for Debby and Sunday at the Village Vanguard (Bill Evans, Riverside)

1961: Coltrane ‘Live’ at the Village Vanguard (John Coltrane, Impulse!)

1962: The Cannonball Adderley Sextett in New York, featuring Nat Adderley and Yusef Lateef Recorded ‘Live’ at the Village Vanguard (Riverside)

1963: Impressions (John Coltrane, Impulse!)

1966: All My Yesterdays: The Debut 1966 Recordings at the Village Vanguard (Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, Resonance, 2016)

1967: Live at the Village Vanguard Again! (John Coltrane, Impulse!)

1970: Betty Carter at the Village Vanguard (Betty Carter, Verve)

1976: Homecoming: Live at the Village Vanguard (Dexter Gordon, Sony)

1979: Nude Ants (Keith Jarrett, Jan Garbarek, Palle Danielsson, Jon Christensen, ECM 1986)

1980: Turn out the Stars (Bill Evans, Nonesuch)

1984: Live at the Village Vanguard (Michel Petrucciani, Blue Note)

1988: Just Friends: Live at the Village Vanguard (Eddie Daniels/Roger Kellaway, Resonance, 2017)

1999: Live at the Village Vanguard (Wynton Marsalis, Sony)

2006: Live – At the Village Vanguard (Brad Mehldau, Nonesuch)

2007: Live at the Village Vanguard (Bill Charlap, Blue Note)

2014: Live at the Village Vanguard (Marc Ribot Trio, Pi Recordings)

#newyork#new york#jazz#jazz music#galelry mod#mod studio#village vanguard#nice to be here#you are welcome#club Tipp#The new weekly Jazz Club section#wikipedia#Thelonious Monk#dizzy gillespie#miles davis#Art Blakey.#Max Gordon#jazz club#pic from Wikipedia#travel time

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Coltrane Quintet with Eric Dolphy - Kulttuuritalo, Helsinki, Finland, November 22, 1961

A day after this performance, DownBeat's John Tynan wrote: "At Hollywood’s Renaissance Club recently, I listened to a horrifying demonstration of what appears to be a growing anti-jazz trend exemplified by these foremost proponents [Coltrane and Dolphy] of what is termed avant-garde music. I heard a good rhythm section… go to waste behind the nihilistic exercises of the two horns.… Coltrane and Dolphy seem intent on deliberately destroying [swing].… They seem bent on pursuing an anarchistic course in their music that can but be termed anti-jazz."

Time has proven Tynan 100% right, of course — this stuff sucks! Just kidding ... the team-up of Coltrane and Dolphy is one the high water marks of modern music as we know it. At least in my opinion. The four-disc Village Vanguard collection offers one of the most incredible listening experiences you'll find anywhere in any genre. And amazingly, we're going to get more Coltrane / Dolphy (and Jones and Tyner and Workman) in about a month. The previously unreleased Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy features 80 minutes of music recorded a couple months prior to the Village Vanguard stand. Unreal! You can check out a sample over on NPR now and although the recording was made with a single mic (by future Dylan engineer Richard Alderson), it sounds well-nigh miraculous.

While we wait for the rest, let's enjoy this wondrous 40+ minutes of the Coltrane Quintet in Finland. Compared to the Village Vanguard tapes from just a few weeks before, the performance is relatively smooth — nothing too outward bound like "India" or "Chasin' Another Trane." Coltrane had already tested the European audience's stamina on his final tour with Miles in 1960, so maybe he was hedging his bets slightly. But that's not meant as a criticism. This is spectacular music from start to finish. And if this group is deliberately destroying swing on the long and luminous "My Favorite Things" here ... well, then destroy away, dudes! Dolphy's incredible flute solo here is a total showstopper.

"At home [in California] I used to play, and the birds always used to whistle with me," Dolphy said. "I would stop what I was working on and play with the birds ... Birds have notes in between our notes—you try to imitate something they do and, like, maybe it’s between F and F-sharp, and you’ll have to go up or come down on the pitch. It’s really something! And so, when you get playing, this comes. You try to do some things on it. Indian music has something of the same quality— different scales and quarter tones. I don’t know how you label it, but it’s pretty."

Photo: Herb Snitzer/Impulse! Records

32 notes

·

View notes