#Jewish War Veteran

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

He admitted he "was just a schmuck", a regular guy, who worked at his brother's liquor store in Southern California. He lived quietly and died on December 5, 2015 at the age of 86.

Not many knew that this same humble man, an immigrant, had "the remarkable courage and forbearance of a . . . American hero, a man who joined the United States Army to thank the nation and the troops that rescued him from the concentration camp where he had been imprisoned as a teenager, and for whom recognition was delayed for decades because he happened to be Jewish," according to the New York Times.

He said his mom taught him that "There is one God, and we are all brothers and sisters. You have to take care of your brothers, and save them."

"To her, to save somebody’s life is the greatest honor," he added. "And I did that.”

You probably never heard of him. His name was Tibor Rubin. He had to wait 55 years to receive the Medal of Honor he deserved. He was the only Holocaust survivor to receive the Medal of Honor.

He was born in 1929 in Hungary.

At the age of 14, "Tibor Rubin was . . . was deported in 1944 to Mauthausen, the Nazi concentration camp complex in Austria," according to the Washington Post. He never saw his parents nor his younger sister again.

A commandant told him that he would never get out alive.

After 14 months, according to writer Adam Bernstein, Rubin had become "a disease-ridden skeleton."

American troops liberated Mauthausen on May 5, 1945. He was so grateful that accoording to a 2013 documentary film, “Finnigan’s War,” about veterans of the Korean War, Corporal Rubin said in broken English, “I promised the good Lord that if I get out of here alive, I’d become a G.I. Joe, to give back something.”

It took him a while to get to America, but when he finally came to the United States in 1948, he kept his promise and tried to enlist. But, because his English wasn't good enough, he had to wait until 1950, when he literally "cheated his way into the Army, he said, by cribbing the entrance exam, according to the Washington Post.

Because he was not a citizen, he was told he didn't have to fight, but somehow made his way to the Korean front lines, when he said, remembering his mother's words - "Well, what about the others? I cannot leave my fellow brothers.”

His sergeant, according to Bernstein, was "a sadist and anti-Semite" who repeatedly "volunteered" Rubin "on seemingly certain-death assignments."

One of those missions had him "single-handedly [hold] off a wave of North Korean soldiers for 24 hours, securing for his own troops a safe route of retreat." That in itself should have earned him the Medal of Honor.

Corporal Rubin would also "spend 30 months as a prisoner of war in North Korea, where testimony from his fellow prisoners detailed his willingness to sacrifice for the good of others," according to the New York Times.

Because he was not a citizen, his captors offered to return him to Hungary, but he refused, deciding to stay in the isolated camp that the Americans called “Death Valley.” He would not forget his mother's words.

He would risk his life sneaking out of the camp, only to return after he foraged for food and and stole enemy supplies, to bring back "what he could to help nourish his comrades."

“Some of them gave up, and some of them prayed to be taken,” Mr. Rubin later told Soldiers magazine. He did his best to rally them, reminding them of relatives praying for their safe return home.

“He shared the food evenly among the G.I.’s,” Sgt. Leo A. Cormier Jr., a fellow prisoner, wrote in a statement, according to The Jewish Journal. “He also took care of us, nursed us, carried us to the latrine.” He added, “Helping his fellow men was the most important thing to him.”

The prison camp survivors remembered Rubin, crediting him with keeping them alive and saving at least 40 American soldiers.

Rubin received the Purple Heart with 1 bronze oak leaf cluster, but not the Medal of Honor.

He returned home, to the United States, where he would lead a quiet life, rarely talking of his war experience.

When he did talk of his war experience, he said he felt guilty, seeing the countless maimed and lifeless bodies and hearing the agonized screams in Korean from the wounded.

“I had the guilt feeling what I did here,” he later told an interviewer with the Holocaust Awareness Museum and Education Center in Philadelphia. “I killed even the enemy but I killed somebody’s father, brother, and all that. . . . But then again, the truth is that if I don’t kill him, he kill me and vice versa. It’s war. War is hell.”

In the 1980s, he attended a reunion of veterans, where he learned that he had been nominated four times for the Medal of Honor by his grateful comrades, but the sergeant, who hated him for his religion, deliberately ignored the orders from his own superiors to prepare the appropriate paperwork.

In 2002, after Congress passed the Leonard Kravitz Jewish War Veterans Act, Rubin's records were reviewed and the affidavits recommending Rubin for the Medal of Honor were found.

He finally received his Medal of Honor at a 2005 White House ceremony.

“I waited 55 years,” he said. “Yesterday I was just a schmuck. Today, they call me, ‘Sir.’ . . . How I made it, the Lord don’t even know. I don’t even know because I was so many times supposed to die over there, but I’m still here.”

Rubin kept his promise to give back something to the country who saved him, and, in doing so, he also remembered his mother's words to consider everyone a brother and take care of them.

The Jon S. Randal Peace Page ·

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

#jewish veterans#world war ii#world war 2#american jews#jewish americans#jewish american heritage month#JAHM#american jewish history#jumblr#jewish history#world war 2 veterans

0 notes

Text

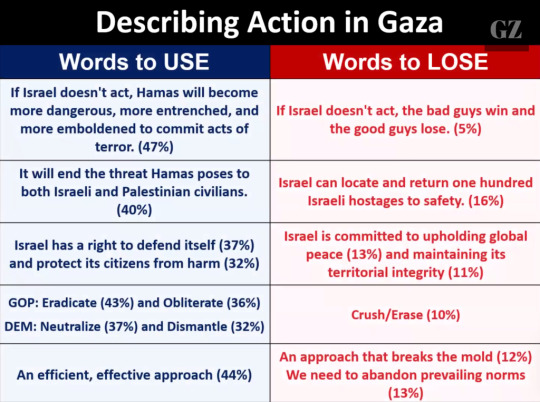

The Grayzone has obtained slides from a confidential Israel lobby presentation based on data from Republican pollster Frank Luntz. They contain talking points for politicians and public figures seeking to justify Israel’s assault on the Gaza Strip. Two prominent pro-Israel lobby groups are holding private briefings in New York City to coach elected officials and well-known figures on how to influence public opinion in favor of the Israeli military’s rampage in Gaza, The Grayzone can reveal. These PR sessions, convened by the UJA-Federation and Jewish Community Relations Council, rely on data collected by Frank Luntz, a veteran Republican pollster and pundit. [...] The Luntz-tested presentations on the war in Gaza urge politicians to avoid trumpeting America’s supposedly shared democratic values with Israel, and focus instead on deploying “The Language of War with Hamas.” According to this framing, they must deploy incendiary language painting Hamas as a “brutal and savage…organization of hate” which has “raped women,” while insisting Israel is engaged in “a war for humanity.” [...] Luntz’s Gaza war presentation puts his poll-tested tactics back in the Israel lobby’s hands, urging pro-Israel public figures to stay on the attack with incendiary language and shocking allegations against their enemies. In one focus group, Luntz asked participants to state which alleged act by Hamas on October 7 “bothers you more.” After being presented with a laundry list of alleged atrocities, a majority declared that they were most upset by the claim that Hamas “raped civilians” – 19 percent more than those who expressed outrage that Hamas supposedly “exterminated civilians.” Data like this apparently influenced the Israeli government to launch an obsessive but still unsuccessful campaign to prove that Hamas carried out sexual assault on a systematic basis on October 7. Initiated at Israel’s United Nations mission in December 2023 with speeches by neoliberal tech oligarch Sheryl Sandberg and former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, a recipient of hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations and speaking fees from Israel lobby organizations, Tel Aviv’s propaganda blitz has yet to produce a single self-identified victim of sexual assault by Hamas. A March 5 report by UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence Pramila Patten did not contain one direct testimony of sexual assault on October 7. What’s more, Patten’s team said they found “no digital evidence specifically depicting acts of sexual violence.”

They also advice to use different language for Democrat and Republican voters, which inadvertently provides one of the most succinct explanation of the difference between the two genocidal parties that I've ever come across:

To make their arguments stick, Luntz recommends pro-Israel forces avoid the exterminationist language favored by Israeli officials who have called, for example, to “erase” the population of Gaza, and to instead advocate for “an efficient, effective approach” to eliminating Hamas. At the same time, veteran pollster acknowledges that Republican voters prefer phrases which imply maximalist violence, like “eradicate” and “obliterate,” while sanitized terms like “neutralize” appeal more to Democrats. Republican presidential candidates Nikki Haley and Donald Trump have showcased similar focus-grouped rhetoric with their calls to “finish them” and “finish the problem” in Gaza.

One of the slides, illustrating what language to use:

There are several more slides in the article. I recommend reading the whole thing, start to finish. One more thing I'd like to highlight though:

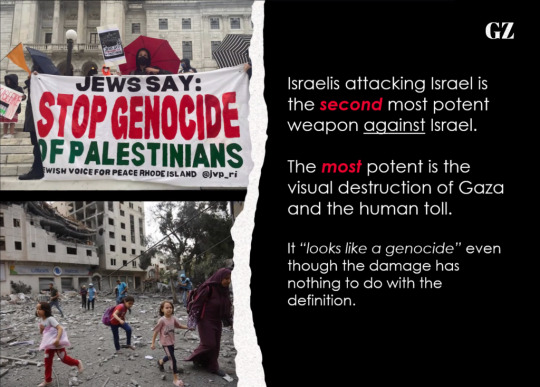

Luntz acknowledges Israel’s mounting PR problems in a slide identifying the most powerful tactics employed by Palestine solidarity activists. “Israelis attacking Israel is the second most potent weapon against Israel,” the visual display reads beside a photo of a protest by Jewish Voices for Peace, a US-based Jewish organization dedicated to ending Israel’s occupation of Palestine. “The most potent” tactic in mobilizing opposition to Israel’s assault on Gaza, according to Luntz, “is the visual destruction of Gaza and the human toll.” The slide inadvertently acknowledges the cruelty of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, displaying a bombed out apartment building with clearly anguished women and children fleeing in the foreground. But Luntz assures his audience, “It ‘looks like a genocide’ even though the damage has nothing to do with the definition.” According to this logic, the American public can become more tolerant of copiously documented crimes against humanity if they are simply told not to believe their lying eyes.

. . . full article on GZ (6 Mar 2024)

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

researching stuff for a post about misinformation regarding girl scout cookies and man this article (10/28/23) about this palestinian-american girl scout nearly made me burst into tears

In her short 17 years on earth, Amira Ismail had never been called a baby killer.

That’s what happened one Friday this month, Amira said, on New York City’s Q58 bus, which runs through central Queens.

“This lady looked at me, and she was like: ‘You’re disgusting. You’re a baby killer. You’re an antisemite,’” Amira told me. When she talked about this incident, her signature spunk faded. “I just kept saying, ‘That’s not true,’” she said. “I was just on my way to school. I was just wearing my hijab.”

Amira was born in Queens in the years after the Sept. 11 attacks. She remembers participating as a child in demonstrations at City Hall as part of a successful movement to make Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha school holidays in New York City.

But since the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas, in which an estimated 1,400 Israelis were killed and some 200 others were kidnapped, Amira, who is Palestinian American, said she has experienced for the first time the full fury of Islamophobia and racism that her older relatives and friends have told stories about all her life. Throughout the city, in fact, there has been an increase in both anti-Muslim and antisemitic attacks.

In heavily Muslim parts of Queens, she said, police officers are suddenly everywhere, asking for identification and stopping and frisking Muslim men. (New York City has stepped up its police presence around both Muslim and Jewish neighborhoods and sites within the five boroughs.) Most painful though, she said, is the sense that she and her peers are getting that Palestinian lives do not matter, as they watch the United States staunchly back Israel as it heads into war.

“It can’t go unrecognized, the thousands of Palestinians that have been murdered in the past two weeks and even more the past 75 years,” Amira said. “There’s no way you can erase that.” That does not mean she is antisemitic, she said. “How can I denounce one system of oppression without denouncing another?” she asked me. The pain in her usually buoyant voice cut through me. I had no answer for her.

Many New York City kids have a worldliness about them, a certain telltale moxie. Amira, a joyful, sneaker-wearing, self-described “Queens kid,” can seem unstoppable.

When she was just 15, Amira helped topple a major mayoral campaign in America’s largest city, writing a letter accusing the ultraprogressive candidate Dianne Morales of having violated child labor laws while purporting to champion the working class in New York.

“My life and my extremely bright future as a 15-year-old activist will not be defined by the failures and harm enabled by Dianne Morales,” Amira wrote in the 2021 letter, which went viral and helped end Ms. Morales’s campaign. “I wrote my college essay about that,” Amira told me with a slightly mischievous smile.

In the past two years, Amira has become a veteran organizer. Last weekend, she joined an antiwar protest. First, though, she’ll have to work on earning her latest Girl Scout badge, this one for photography. That will mean satisfying her mother, Abier Rayan, who happens to be Troop 4179’s leader. “She’s tough,” Amira assured me.

At a meeting of the Muslim Girl Scouts of Astoria last week, a young woman bounded into the room, asking whether her fellow scouts had secured tickets to an Olivia Rodrigo concert. “She’s the Taylor Swift of our generation,” the scout turned to me to explain.

A group of younger girls recited the Girl Scout Law:

“I will do my best to be honest and fair, friendly and helpful, considerate and caring, courageous and strong, and responsible for what I say and do, and to respect myself and others, respect authority, use resources wisely, make the world a better place and be a sister to every Girl Scout.”

Amira’s mother carefully inspected the work of some of the younger scouts; she wore a blue Girl Scouts U.S.A. vest, filled with colorful badges, and a hot-pink hijab. “It’s no conflict at all,” Ms. Rayan told me of Islam and the Girl Scouts. “You want a strong Muslim American girl.”

At the Girl Scouts meeting, Amira and her friends discussed their plans to protest the war in Gaza. “Protests are where you let go of your anger,” Amira told me.

Amira’s mother was born in Egypt. In 1948, Ms. Rayan told me, her grandfather lost his home and land in Jaffa to the state of Israel. At the Girl Scout meeting, Ms. Rayan was still waiting for word that relatives in Gaza were safe.

“There’s been no communication,” she said. When I asked about Amira, Ms. Rayan’s eyes brightened. “I’m really proud of her,” she said. “You have to be strong. You don’t know where you’re going to be tomorrow.”

By Monday, word had reached Ms. Rayan that her relatives had been killed as Israel bombed Gaza City. When I asked whom she had lost, Ms. Rayan replied: “All of them. There’s no one left.” Thousands of Palestinians are estimated to have been killed by Israeli airstrikes in Gaza in recent weeks. ... Ms. Rayan said those killed in her family included six cousins and their children, who were as young as 2. Other relatives living abroad told her the cousins died beneath the rubble of their home.

As Ms. Rayan spoke, I saw Amira’s young face. I wondered how long this bright, spirited Queens kid could keep her fire for what I believe John Lewis would have called “good trouble” in a world that seems hellbent on snuffing it out. I worried about how she would finish her college applications.

“I have a lot of angry emotions at the ones in charge,” Amira told me days ago, speaking for so many human beings around the world in this dark time.

I thought about what I had seen over that weekend in Brooklyn, where thousands gathered in the Bay Ridge neighborhood, the home of many Arab Americans, to protest the war. In this part of the city, people of many backgrounds carried Palestinian flags through the street. Large groups of police officers gathered on every corner, watching them go by.

The crowd was large but quiet when Amira waded in, picked up her megaphone and called for Palestinian liberation. In an instant, thousands of New Yorkers repeated after her, filling the Brooklyn street with their voices. My prayer is that Amira’s generation of leaders will leave a better world than the one it has been given.

i believe she recently got her gold award (which, if youve never been in girl scouts, is really difficult - way more difficult than eagle scout awards), or is almost done with it. i hope she's doing okay.

this article (no paywall) about muslim and palestinian girl scout troops in socal also almost made me cry (it's like 2am). i really really hope all these kids are doing alright. god. they and their families all deserve so much better

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Uncredited Photographer Members of the Italian Anti-fascist Movement "Giustizia e Libertà" (Justice and Liberty). In the Middle, Founders Carlo Rosselli, Giovanni Bassanesi and Ferruccio Parri, Paris c.1930

Italian Jewish brothers Carlo and Nello Rosseli were among the founders of the "Giustizia e Libertà" Italian anti-fascist movement, founded in exile in Paris and active underground in Italy. The Rosselis were veterans of the anti-fascist International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War, during which they organized and served in the Matteotti Battalion. While serving in Spain, Carlo Roselli originated the slogan of the Italian anti-fascists, "Oggi in Spagna, domani in Italia" ("Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy"). The Rosseli brothers were murdered by French fascists in 1937.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

by POTKIN AZARMEHR

‘Pro-Palestine’ protests have become a near-weekly occurrence across Britain. Since Hamas’s 7 October massacre, regular marches have been drawing in a growing number of young people, marked by passionate advocacy and fervent slogans. Yet despite their zeal, many of these protesters lack a fundamental understanding of the conflict they are so vociferously decrying.

In the past six months, I have attended many of these marches. Having engaged with numerous protesters, I have noticed a startling disconnect between their strong opinions on the Gaza conflict and their shaky grasp of basic facts about it. Among the most perplexing are the LGBT and feminist groups (the ‘Queers for Palestine’ types) who flirt with justifying Hamas’s atrocities. This is a bewildering alliance, given that Hamas’s Islamist ideology is clearly antithetical to the rights and values these groups claim to champion. Its reactionary agenda is profoundly hostile to women’s rights and LGBT individuals.

Protesters seem eager to make excuses for Hamas, but are conspicuously uninformed about exactly what or who this terrorist group represents. On 18 May, during a protest at Piccadilly Circus in London, I spoke to demonstrators who firmly believed that Hamas represents all Palestinians. When I questioned a well-educated participant about the last Palestinian election, she was unaware that none had occurred since 2006, when Hamas gained power in Gaza.

It wasn’t just young people who were uninformed. An older woman with an American accent, seemingly a veteran protester, admitted she knew that Hamas was linked to the Muslim Brotherhood, but had no deeper knowledge of its ideology or history. Others, such as members of revolutionary socialist groups, displayed similar gaps in understanding, unaware of critical events like the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

That revolution gave birth to the Islamic Republic of Iran, a theocratic regime that brutally oppresses its own citizens. It also sponsors Islamist groups like Hamas. I left Iran for the UK not long after that regime began and have spent years resisting its religious extremism and ruthless political intolerance. Protesters were not only unaware of these facts about the Iranian regime, but also ill-informed about the struggle against it, such as the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ protests against the government that began in 2022.

One particularly telling conversation involved a man advocating for a ‘Global Intifada’ to replace capitalism with socialism. When asked about successful socialist models, he was unfamiliar with the Israeli kibbutzim, one of history’s few successful egalitarian experiments. His ignorance of these communal settlements in Israel, built by socialist Jewish immigrants, was all too typical.

Perhaps the most telling moment was captured by commentator Konstantin Kisin earlier this year, when he encountered a young man holding a ‘Socialist Intifada’ placard. The protester admitted he had no idea what this meant and that he had taken the sign simply because it was handed to him.

Reflecting on past movements, such as the American anti-Vietnam War protests of the 1960s and the British Anti-Apartheid Movement of the 1980s, one can’t help but note a stark contrast. Protesters then were generally well-informed about their causes. Today’s pro-Palestine protests, however, seem to be driven more by unthinking fervour than by an understanding of the issues at hand.

Throughout all these protests, I am yet to encounter a single participant who condemns Hamas or carries a placard denouncing its terrorism. This not only undermines the protesters’ cause, but also risks aligning them with groups whose values fundamentally oppose the very rights and freedoms they claim to support. It appears that today’s young protesters are high on ideology, but woefully thin on facts.

Potkin Azarmehr is an Iranian activist and journalist who left Iran for the UK after the revolution of 1979.

305 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book recs: angels

Want some cool fictional angels? Good news! Whether you prefer traditional winged angels, scary eldritch angels, possibly-human-angels, incredibly creative in-name-only-angels, angels separated from or exploring concepts of faith and religion, romance, horror, fantasy, or sci-fi; this list is sure to offer something to chew on!

For more details on the books, continue under the readmore. Titles marked with * are my personal favorites. And as always, feel free to share your own recs in the notes!

If you want more book recs, check out my masterpost of rec lists!

Historical fantasy angels

When the Angels Left the Old Country by Sacha Lamb*

The angel Uriel and the demon Little Ash have been friends for centuries, living and studying together in a small jewish community in Europe. But times are changing, and many of the community have left for a new life across the sea. When one of these emigrants go missing, Uriel and Little Ash decide to leave their peaceful life and go find and, if needed, save her.

A Master of Djinn by P. Djèli Clark

Set in an alternate 1910’s steampunk Cairo, where djinn and other creatures (among other things, creepy steampunk angels) live alongside humans. We get to follow an investigator as she races to catch a criminal using a powerful object to control djinn and stir unrest. Fantastically creative and fresh, and also features a buddy cop dynamic between two female leads as well as a sapphic romance.

The Angel of the Crows by Katherine Addison*

Sherlock Holmes retelling. After having been injured fighting a war against fallen angels, Doyle returns to London to survive on only a veteran's pension. To afford a place to live in the city, Doyle finds a housemate in Crow, and eccentric angel with a great curiosity for humans and a knack for solving crime. And London needs its protector - supernatural beings walk the streets, and a someone going by the name Jack the Ripper terrifies the citizens at night.

Modern day fantasy angels

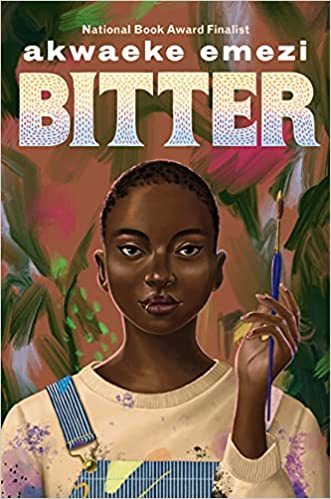

Bitter by Akwaeke Emezi

Novella, young adult. Bitter is an art student in Lucille, a city on the brink. Injustice plagues the citizens and protests shake the streets, and Bitter doesn't know where her place his - whether to fight or stay safe. When her art calls upon a creature of bloody justice, she must ask herself just how far she’s prepared to go and what price she’s ready to pay for justice.

Daughter of Smoke and Bone by Laini Taylor

Young adult portal fantasy. Young Karou is a student in Prague, but she’s also a mystery. She fills sketchbooks with drawings of monsters, trades in wishes, speaks languages that aren't all human, and has hair that grows out blue. When strange signs start appearing around the world - handprints scorched into doorways by winged strangers - will Karou finally find out who she really is?

Angelfall by Susan Ee*

Young adult post apocalypse. Six months ago, the angels descended on the Earth - and brought the apocalypse with them. Between ruling street gangs and vicious angels, Penryn is just trying to keep her family alive. When angels fly away with her little sister, Penryn does the unthinkable: strikes a deal with an injured and outcast angel to rescue her.

A Madness of Angels by Kate Griffin*

Urban fantasy. Two years ago, sorcerer Matthew Swift was killed. Today, he woke back up. And he isn't alone in his body, but rather in the company of the blue electric angels, who lived in the telephone lines and are now experiencing the world for the first time through him. Now, he seeks vengeance not only against the one who killed him, but also against the one who brought him back.

The Fall that Saved Us by Tamara Jerée*

Cassiel is of angelic heritage, raised to fight and kill demons alongside her family. But Cassiel has left the hunt and her family behind, wanting a normal life. For three years she's built a life for herself, cut off from her family, but now a demon has found her, sent to collect her soul. Except, the demon isn't any more interested in following the orders of her family than Cassiel is. Can they work together to free themselves from the expectations placed on them? Sapphic romance.

Out of the Blue by Sophie Cameron*

Young adult, sapphic main character. When angels started falling from the sky, the world went mad. So far not a single angel has survived the fall, but that doesn't stop teenage Jaya's father from growing an obsession with catching one, going as far as uprooting the entire family to Edinburgh in hopes of finding one. Jaya, busy mourning the recent loss of her mother, finds his obsession pointless - until an angel crashes right at her feet. What’s more, it's alive...

Full on fantasy angels

Tread of Angels by Rebecca Roanhorse

Novella. During Heaven's War, the rebel Abaddon died and fell. Now, long after, what remains of his body is a valuable element called divinity, which is mined by Fallen, descendants of those who fell and the only ones capable of perceiving divinity. Celeste, a Fallen raised among the privileged Elect, is deeply protective of her little sister Mariel. When Mariel is accused of having murdered an Elect, it’s up to Celeste to find out what really happened and save her sister.

The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman

Middle grade. In Lyra's world, every person has a daemon: an animal companion who follows them throughout life. When children begins being stolen off the street, among them Lyra's friend, she must embark on a great journey to save him, taking her to the furthest north - and beyond. A note: the angels do not appear until the second book, however this trilogy is very much worth a read from the start.

Gunmetal Gods by Zamil Akhtar

Dark fantasy inspired by the crusades. Seeking revenge, Micah the Metal leads an army of men baptized i angel's blood against the kingdom that stole his daughter. It’s up to Kevah, legendary fighter, to stop him and save his people. But ever since losing his wife a decade ago, Kevah has lost his fighting spirit. To defeat Micah, he must find it within himself a will to live again. While featuring (scary eldritch) angels, they serve more as a driving background/world-building force than as actual characters.

Horror angels

The Unnoticeables by Robert Brockway

Angels watch over humans, but not to protect us but to solve us, seeking to make the universe more efficient and clean away the undesirable. Carey, a 70s punk, doesn't like the idea of being solved. Watching fellow punks disappear off the streets, he becomes embroiled in a dangerous conspiracy. Decades later, stunt woman Kaitlyn has her own encounter with the angels and their creations - as well an older punk who might have the answers she needs.

Hell Followed With Us by Andrew Joseph White

Young adult post apocalypse. The world has ended, and sixteen-year-old trans boy Benji is on the run from the cult that caused armageddon. Infected with the bioweapon they released to bring about the end, Benji is slowly transforming into something not quite human and desperate to find someplace safe. When coming across a group of surviving teens, Benji finds something new to fight for. No traditional angels, but it does play with the concept.

Angel Radio by A.M. Blaushild

Young adult post apocalypse. A week after strange and terrifying angels appeared, humanity is dead. Sole survivor of her town, teenage Erika is left wandering on her own. That is, until she catches an odd broadcast on the radio which lures her into the newly emptied world. There she encounters dangerous creatures, but also fellow survivor Midori, who has a cryptic connection to the angels.

Sci-fi angels

Archangel Protocol (LINK Angel series) by Lyda Morehouse

Cyberpunk. In a future where religion has become the law of the land and people spend as much time in cyberspace as in reality, ex-cop Deirdre has lost everything after having been accused of a crime she didn't commit. When approached by a man calling himself Michael and asked to solve the mystery behind the so called link angels - supposed angels who show themselves in cyberspace - Deirdre is given a chance at redemption and answers.

Archangel by Sharon Shinn

For twenty years, archangel Raphael has ruled over the lands, leading to corruption among both angels and mortals. Now the time has come for the angel Gabriel to become archangel, but first he must find his Angelica, a mortal woman chosen by Jehovah to be by his side. But his chosen partner, Rachel, has lived under oppression and fear, and she has her own ideas of what she wants - ideas that don't include Gabriel.

Terminal World by Alastair Reynolds

On a dying earth, society is separated by zones in which the laws of reality shift, allowing for different levels of technology and life. At the top of Spearpoint, the only surviving city, lies the Celestial zone, in which only angels can survive. Quillon, former angel who's had his wings removed and body changed so he can survive and infiltrate the lower zones, has been in hiding for years when he receives a warning that his former people are hunting him. Forced on the run, Quillon must leave Spearpoint for the dangerous wastes beyond, where he will discover ancient secrets of his world.

Space angels

Dust by Elizabeth Bear

In a dying spaceship, orbiting an equally dying sun, noblewoman Perceval waits for her own gruesome death. Having been captured by an opposing house, her wings severed and life forfeit, Perceval’s execution is imminent - until a young servant charged with her care proves to be Perceval’s long lost sister. To stop a war between houses likely to doom them all, the two flee together across a crumbling, dangerous spaceship. At its core waits Jacob Dust, god and angel, all that remains of what the ship once was. And he wants Perceval. Sapphic and asexual characters, however be prepared for kinda fucked up relationships.

The Outside by Ada Hoffman*

AKA the book the put me in an existential crisis. Souls are real, and they are used to feed AI gods in this lovecraftian inspired sci-fi where reality is warped and artificial gods stand against real, unfathomable ones. Autistic scientist Yasira is accused of heresy and, to save her eternal soul, is recruited by cybernetic ‘angels’ to help hunt down her own former mentor, who is threatening to tear reality itself apart. Sapphic main character.

The Genesis of Misery by Neon Yang

Space opera inspired by Joan of Arc. Misery Nomaki possesses rare stone-working abilities usually found among only saints and the voidmad. Not believing herself the be former and desperately not wanting to become the latter, Misery is trying to keep a low profile. Her attempt fails when the voice of an angel - or a very convincing delusion - leads her to become the centerpiece of a dangerous battle between two warring factions hoping to use her. Very unique and cool conceptually, but a little all over the place in how it handles its plot.

Bonus AKA I haven’t read these yet but they seem really cool

Dusk in Kalevia by Emily Compton

Toivo Valonen is a secret agent in more ways than one. An angel masquerading as human, he's acted as a source of hope for humanity in wartime throughout history. In 1960, he embarks on an undercover mission to Kalevia, allied with a rebellion against the government. In his way is fellow angel and rival agent Demyan Chernyshev, who’s working for the KGB.

The House of Shattered Wings by Aliette de Bodard

Having just barely survived the Great Houses War, much of Paris lies in ruins. Morningstar, founder of the House Silverspires, has gone missing, and something is stalking the people within the House's walls. Three people, a Fallen, an alchemist, and a man wielding spells from the far east, may be prove to be Silverspire's salvation.

The Worst Perfect Moment by Shivaun Plozza

Young adult. Sixteen-year-old Tegan is dead and i heaven. There, she's supposed to be reliving her happiest memory. Except the moment Tegan has been placed in isn't very happy at all. Guided by an angel, Tegan is brought through her past to understand what most matters to her. If she fails to see the happiness in her assigned memory, the consequences would be dire for both her and the angel.

Honorary mentions AKA these didn't really work for me but maybe you guys will like them: The Library of the Unwritten by A.J. Hackwith, City of Bones by Cassandra Clare, Hush, Hush by Becca Fitzpatrick, Sandman Slim by Richard Kadrey

#nella talks books#when the angels left the old country#a master of djinn#the angel of the crows#bitter#daughter of smoke and bone#angelfall#a madness of angels#the fall that saved us#out of the blue#tread of angels#the golden compass#gunmetal gods#the unnoticeables#hell followed with us#angel radio#archangel protocol#archangel#terminal world#jacobs ladder#the outside#the genesis of misery#angels

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heavenbound AU

Masterpost

Husk

Design notes and headcanons under the cut

Husk always struck me as the type that should be more stocky and broad. And he should have a beer belly, since alcoholism is a significant character trait of his. He's a fat cat. He has a few grey streaks in his hair to hint at his age. His clothes are more tattered to represent both his loss of power and his deal with Alastor. And his colors are duller after he lost his overlord status.

Older versions of his character portrayed him as a magician, and I really liked the idea of him using his magician skills to cheat at cards, which is why he got into gambling.

Generally speaking, his canon design is too busy and I simplified it. I didn't really understand why he had wings. Thematically, there's no reason for it and they overcomplicate the design. Instead, I gave him a magician's cape to reference his magician background. His hands are white to resemble the gloves magicians wear. The shirt helps to separate his dark fur from his pants, so they don't blend together too much.

He has card suit symbols integrated into his design. I didn't think to add a shirtless version here(if I get around to it, I'll update this with one), but he does have a spade pattern on his chest. You can see the tip of it around his collar. His nose is shaped like a heart, his tail has a diamond shape, and the paw pads on his hands and feet are clubs.

Human-

He was born in 1907 and died in 1975 at age 68 from liver failure. It's popular for people to design him as black, but I headcanon him with either Slavic or Jewish Russian ancestry. He's lived in the US his whole life though. The chipped tooth sorta just happened and I liked it. It kind of resembles his demon form's cat teeth.

He became a magician and used his skills in sleight of hand to cheat at cards. He became involved with a gambling syndicate in Las Vegas. And he was a heavy drinker(hence his eventual liver failure).

Is he a war veteran? Lots of people headcanon Husk as a Vietnam War veteran. But I'm not sure that works very well. At least, not with my headcanons. The draft for Vietnam went on between 1964-1973. Husk would have been 57 in 1964, and the number of Baby Boomers meant the draft could make more exceptions than in previous wars. So Husk was not involved with Vietnam.

But the draft for WW2 required all men 18-64 to register between 1940 and 1946. There are a few nuances, such as the required ages being narrower at the beginning of that time, but they ultimately don't matter here. Husk was in his 30s through the entire draft period. So unless he had a reason to be exempted, or he dodged the draft, he was probably going. But Husk doesn't actually strike me as a shell shocked veteran. So I'm leaning toward him being a draft dodger.

Syndicat the Gambling Overlord-

While doing Mafia research for Angel Dust, I came across a mention of gambling syndicates in Las Vegas. I realized it fit Husk's background, and decided his name before Husk could be Syndicat. I thought the cheesiness of it wasn't out of place. So here we are.

His magician life led him to gaining magician(mostly cards) related powers. He gambled for souls and won his way to Overlord and ran a gambling syndicate. But he got cocky and others started to catch on. They did different types of gambling that didn't involve things he could easily cheat in. He started losing bets, and he was too proud and addicted to cut his losses. Plus, he was the Gambling Overlord, he couldn't stop gambling!

Eventually Alastor showed up and challenged him to Syndicat's specialty: poker. The offer was practically too good to be true. They were gambling all the souls they owned(their own souls were implied to be included). If Syndicat won, he'd have the collective power of Alastor's souls. If Alastor won, Syndicat would still be allowed to keep his existing power in exchange for servitude.

Alastor was a top tier Overlord, and owning the Radio Demon would surely catapult Syndicat to the top! He thought he had this in the bag. But Alastor has an inscrutable poker face, magic of his own, and his soul isn't even available to be put on the table. Syndicat predictably lost, and his overlord status was officially gone.

It hadn't really mattered either way. The whole thing was rigged. Alastor's soul was never going to be Syndicat's, and Alastor had clawed his way to Overlord in record time(He took less than a week to orient himself, killed his first overlord, and that was it). So even if he lost, it wouldn't take long for the Radio Demon to be back in full force. He could have just destroyed Syndicat and gotten everything back anyway.

The Husk:

Alastor dubbed him a husk of his former self and kept calling him either Husk or Husker. Husk felt too sorry for himself to care, and decided the name fit. (He doesn't hate "Husker" any more than he does "Husk". In the pilot, he was just annoyed at being magicked away from his poker game)

As far as Overlords go, Alastor wasn't actually all that bad to work for. Husk had actually been a crueler overlord to his underlings. For the most part, Alastor let him carry on as before. Husk gambles for cash and drowns himself with more booze than ever before, but he can't gain or lose power while Alastor owns him. Alastor could bother Husk at any given moment without warning and drag him to do whatever, but it would sometimes be months or years between his summons(seven years was significantly longer than normal, but Husk never thought much of it until after). Alastor is mostly just manipulative, confusing, and condescending. He didn't try to hurt Husk, and rarely even threatened to. Husk was still going to be grumpy about it though.

(update notes will go here if needed)

#hazbin hotel#hellaverse#husk#husker#heavenbound au#hazbin hotel redesign#a3 art#fan art#digital art#character sheet#human husk

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

im guessing israel hasnt thought far enough ahead to what theyre going to do after every palestinian is murdered and israel is left with, im guessing, 80% of their reproductive aged able bodied citizens having been turned into an unbiddable, unhirable, and rapacious soldier class. ancient norse stories and my vietnam veteran father tell us these people weren't good for much other than consuming massive amounts of veteran's benefits and occasionally freaking out and causing mass civilian casualties after the "war" is over. i suspect they will throw everything into cranking up Birthright tourism to get American-Jewish (and, as a backup, evangelical and probably mormon) teenagers without ptsd (ptsd is the wrong term but we dont currently differentiate between victim and perpetrator trauma in the diagnosis, which is bad) to emigrate and have babies

167 notes

·

View notes

Text

THURSDAY HERO: Giorgio Perlasca

Giorgio Perlasca was an Italian fascist and emissary of Benito Mussolini who had a change of heart and used his diplomatic status to save 5,218 Hungarian Jews from the Nazis.

Born in Como, Italy in 1910, as a young man Georgio became a fervent believer in fascism, believing it was the best system for achieving societal safety and prosperity. Dedicated to fascist ideology, he joined the Italian army to fight prime minister Benito Mussollini’s war of aggression against Ethoipia (the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935-37). Italy invaded Ethiopia and sent leader Haile Selassie into exile in 1937. Still a committed fascist, Giorgio pivoted straight from Ethiopia to Spain, where he fought on the side of Franco’s Nationalists against the defenders of the Spanish Republic.

Giorgio went back to Italy in 1938, and that’s when his world was rocked and his personal belief system made a 180 degree turn. Just as he was returning to his native land, the Nazi-allied fascist government adopted the Italian Racial Laws, which persecuted and segregated Italian Jews and African immigrants from the Italian colonial empire. The first law banned Jews from working with the public or attending college. Books by Jewish authors were burned. The next set of laws confiscated Jewish property, prohibited them from traveling, and finally arrested and imprisoned them. Italian newspapers were filled with vicious anti-Jewish propaganda and hideous caricatures.

Giorgio Perlasca, the man who’d spent the last decade fighting for fascism, was horrified. Perhaps he’d been in north Africa and Spain for so long, he wasn’t aware of the extent of Nazi persecution of the Jews. He’d joined the fascists because, young and naive, he thought they had answers to societal problems. But he never signed up for the Nazis’ “final solution.” He believed in human rights, freedom and tolerance and therefore realized he had to reject fascism.

Ironically, just as he was rejecting Mussolini’s ideology, he was rewarded for his service by being granted diplomatic status and sent to Budapest to represent the interests of the Italian government. As an emissary, Giorgio’s most urgent mission was traveling throughout Eastern Europe to purchase large quantities of meat for Italian army soldiers fighting on the Russian front. Despite his political shift, he remained committed to what he felt was honorable work procuring food for Italians who’d been drafted into the army.

On September 8, 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allied forces. Diplomats like Giorgio had a choice to make: pledge allegiance to Mussolini, or join the Allies. Giorgio switched sides and instead of returning to Italy he was arrested and detained with other diplomats sympathetic to the Allies. After several months in captivity, he used a medical pass to leave the facility. He went straight to the Spanish embassy, which was being run by Angel Sanz Briz*, a diplomat who was secretly saving Hungarian Jews. Sanz Briz enabled Giorgio to claim asylum as a veteran of the Spanish war. Giorgio called himself “Jorge” (the Spanish version of Giorgio) and as a nominal Spaniard, was untouchable by the Nazi-allied Hungarian authorities since Spain was officially a neutral country.

Giorgio Perlasca during the war.

Giorgio immediately teamed up with Sanz Briz to save Jews from the Nazi death machine, which was systematically massacring the Jews of Hungary at shocking speed. He later said, “I couldn’t stand the sight of people being branded like animals… I couldn’t stand seeing children being killed. I did what I had to do.” Giorgio convinced diplomats from neutral countries to shelter Jews in their embassies and homes. He created “protection cards” that identified Jews as being under diplomatic guardianship and therefore impossible to arrest. In November 1944, Sanz Briz was transferred from Hungary to Switzerland, and he urged Giorgio to go with him. However, instead of traveling to a safe country, Giorgio put his own life at risk by staying in Hungary so he could continue saving Jews from the Nazis.

The Hungarian authorities got wind of what Giorgio was doing, and they used Sanz Briz’ departure from the country as an excuse to order the Spanish embassy building and residences to be emptied and shuttered. In response, Giorgio made a bold move. He announced that Sanz Briz would be returning shortly, and he’d been appointed consul-general in the meantime. This bought him enough time to continue saving Jews, providing them with sanctuary and vital supplies. He also issued fake transit visas based on a 1924 law giving Jews of Sephardic heritage Spanish citizenship. The law had expired in 1930 but Giorgio managed to keep that part secret.

In December 1944, Giorgio stood up to high-ranking Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann – architect of the genocidal “Final Solution” – who was about to force two Jewish children onto a freight train headed to a death camp. Swedish rescuer Raoul Wallenberg later described watching Giorgio boldly defy the vicious Eichmann and rescue the Jewish boys.

Around this time the Nazi-aligned Hungarian government known as the Arrow Cross set up a squalid ghetto in Budapest for the city’s 60,000 Jews. As “acting Spanish consul-general” was privy to top-secret information, and he learned that the Arrow Cross was going to liquidate the ghetto – which meant murdering the men, women and children who lived there. Giorgio demanded – and got – a private hearing with the Hungarian interior minister Gabor Vajna. He threatened the high-ranking government official with severe repercussions against the “3,000 Hungarians” currently living in Spain. Unless the government backed down on destroying the ghetto, those Hungarian expats would be harshly punished financially, legally and professionally. The fact was, there were nowhere near 3000 Hungarians in Spain and the real number was a fraction of that. That bold threat, combined with a promise to help Vajna and his family escape the advancing Soviet army, prevented the Budapest ghetto from being liquidated, saving thousands of lives.

After the war, Giorgio Perlasca returned to Italy where he lived a quiet life as a businessman, married and raised a family. and didn’t tell a single soul about his heroic actions during the war. Meanwhile, a group of Hungarian Jews saved by Giorgio searched for him for decades. They knew their rescuer as a Spaniard named Jorge and it took 42 years for them to finally locate him. In 1987 Giorgio’s wife, children and community were utterly shocked to learn that this unassuming man had saved the lives of a documented 5,218 Jews and probably many more. The famous rescuer Oskar Schindler saved a quarter as many people as Giorgio Perlasca did.

Once Giorgio’s heroism was known, he became famous in Italy and a source of national pride. Giorgio Perlasca was the subject of a bestselling biography, “The Banality of Goodness,” which was made into a popular movie. He received many honors, including Righteous Among the Nations by Israeli Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem, the Wallenberg Medal, the Hungarian Star of Merit, the Spanish Knight Grand Cross, the Italian Gold Medal for Civil Bravery, and many others. Noted Israeli composer Moshe Zorman wrote an orchestral piece, “His Finest Hour,” about Giorgio. There is a statue of Giorgio Perlasca in Budapest and a high school named for him, and he was featured on an Italian and an Israeli stamp.

Giorgio died in Padua, Italy in 1992.

For saving thousands of lives, and proving that people can change, we honor Giorgio Perlasca as this week’s Thursday Hero.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's the Khazarian Mafia who stole the Jewish name.

This is who the war is with, NOT each other.

You don't have to belittle others because they have a difference of opinion about certain things. So what if they see differently than you, you see my posts and you know what side I'm on yet I see comments about me that are totally untrue. The fact that people have formed an opinion about someone they don't even know is what's wrong with the world and it's also why I only follow less than 50 on here. They don't judge me because I have the balls to post things no one else will.

I am on my 5th account and the ones who stuck by me are amazing patriots and they helped me get my accounts rolling again 🤔

@usmcfe

@rem64

@surprising-world-we-live-in

@towerofhealthsix

@twinflamedreams

And since then I have many others who would do the exact same thing. It's been about a year and 8 months since starting this blog to make people think outside of the box and as of today I have nearly 15,000 following. I'm a disabled veteran and I spend in excess of 10 hours a day since Trump got in office doing research, NOT for me but for you and I would never ask anyone for a penny. So all you judges, critics and patriot haters who call me names... Do whatever you want. I don't give a rats-ass what people think of me. 🖕

#pay attention#educate yourselves#educate yourself#knowledge is power#reeducate yourself#reeducate yourselves#think about it#think for yourselves#think for yourself#do your homework#do your research#do some research#do your own research#ask yourself questions#question everything#khazarian mafia#government corruption#evil#good vs evil#fight for freedom#fight fight fight#war#the storm#brainwashed#wake up

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Bite of Rope: Part I

Kink fiction. An ex-soldier who can’t sleep one night follows a coworker to somewhere unexpected.

Rated E. Cis M/M. Set in 1950s London.

An ex-soldier, Arthur “Kuhn” Conrad, now a debt collector of sorts for a corrupt company, can’t sleep one night, and as he’s walking the streets, sees a coworker — on a whim, he follows, and ends up in an underground club. The older man, Ignatius Kasovitz, likes to tie people up, it seems, and Kuhn finds he wants to try being tied up, if it’s Kasovitz doing the tying.

CWs for continuous references to World War II and the Shoah — Kuhn is a veteran, Kasovitz is Jewish; various homophobic & transphobic language, particularly from Kuhn; trauma; violence. This one will be kink-focused over sex itself, with Kuhn being somewhere on the ace spectrum.

This won't be a long serial, only two or three parts. Please remember to comment and let me know what you think!

Read on Patreon / / Read on Medium / / Read on Ao3.

---

It’s a dry, hot night, and Kuhn can’t sleep. It’s past ten at night and there’s no work for him to be getting on with, and being as it’s a Friday, most of the quieter pubs around him are not so quiet tonight, so he walks. No one fucking bothers him – he’s recognised here and there, by the sort of scum who’d recognise like for like, but it’s mostly not recognition that keeps people from coming near him.

He's told he has a dangerous air, no matter that he’s on the small side. He’s not scrawny, after all, not anymore – he’s square, and he’s got hard angles, but at the shoulders and the jaw, not at the elbows or the show of bone – and he has a fierce, rapid pace when he moves.

Doctor Lark, who heads up the office, says that any man who knows dogs can often see from afar the sort of dog that will bite at the drop of a hat, the sort of dog that won’t stop short at a nick but will savage you deeply. Kuhn doesn’t know anything about dogs at all – he likes cats, personally – but Lark says you can see a dog that will rip your guts out based on how its eyes cast about, how it draws back its lips and shows its teeth, how it lunges, how it ducks or lifts its head as it runs toward you.

“You look like a feral fucking dog, Kuhn,” Lark had said, and patted him very hard on the back, sending a percussive thump through his ribcage. Kuhn doesn’t like to be touched much, but the way Lark does it has never bothered him, short and abortive as it is, and always very hard instead of feigning softness. “You look fucking rabid, from afar, and worse, up close. Too much white in your eyes.”

Kuhn turns a corner and stares straight forward, knowing his eyes look dead even before a few young women on a night out blanch at facing him and hurriedly cross the road. That fills him with no especial pleasure, but a pleased hum settles low in his gut when a minute later a big man in a duffle coat, drunk and a little unstable on his feet, does the exact same thing, albeit more subtly.

He's not walking anywhere in particular. He’s just walking – stalking, but stalking the way a man does it, moving forward all angry, not like an animal does it. He’s not hunting for anything…

Until he is.

Kuhn recognises Ignatius Kasovitz from damn near two streets away, even though he’s nothing more than a tall blur in the distance. Kuhn recognises his gait as much as he does his height, the smooth and long-legged stride that sets Kasovitz well-aside from all the girls in the secretarial pool, and all the other men, too.

He doesn’t like Kasovitz, but that’s what makes him an easy target to tail, Kuhn thinks. He’s not following the old man because he’s really interested in where he lives, because he wants to sit and talk with him, or even because he wants to use any information against him, blackmail him with where he’s been at night, or where he’s going.

It’s none of that. He just follows Kasovitz because he recognises him, and he’s someone that doesn’t matter.

He follows Kasovitz out of Soho proper, and he wonders at first if Kasovitz is going to go as far as one of the popular cottages, one of the greens where inverts like him pay a shilling or two to the ex-soldiers selling themselves as gigolos, but instead, Kasovitz trails down one street and then another, then descends a set of steps behind an iron railing.

Kuhn comes to the edge of the railing and looks down the steps, then trails in pursuit. Down here, out of the view of the main street, he can see people milling about – more queers like Kasowitz, queers and sapphics and that sort, different people done up for a night out, smoking cigarettes, laughing with each other. It’s just a bit too crowded for enough people to notice Kuhn and part around him, and he’s glad he’s wearing his hat – he blends in well enough with the shorter faggots and the littler dykes.

All these fucking freaks lined up in their dresses and suits and jewellery, trading cigarettes and compacts of coke – is this what they fought a fucking war for?

He can’t hear the music from inside whatever club this is from out here in this draughty corridor underneath the eaves of the shops upstairs, but the noise around him is still digging under his skin like splinters, like gritted sand in a hard wind, like sparks off the fire. Three mincing cunts done up like girls – two of them are in wigs, the other one, that might be his own fucking curls – are giggling and laughing with each other; he can hear the wet, messy sound of two women necking even though they’re in a shadow and he can’t actually see them; two men are playing a game of slapsies, and whenever one of them gets a hit in, the other one grabs at his arse or his thigh.

He’s irritable from not having slept yet, but at the same time, it’s the irritability that’s not letting him sleep. There’s a burn and prickle under his skin – it’s the dry heat of the night, he thinks, and how it’s making him sweat, how it feels uncomfortably light whilst still being nasty in its temperature. His skin, slicked with sweat, doesn’t feel as though it fits him. It hasn’t felt as if it fits him for a long, long time.

“You alright, love?” asks a skinny homo who must be eighty or ninety, walking past Kuhn with a stick. He’s wearing a silk scarf around his neck. “You want to get some water down you – you do look a bit peaked, if I do say so myself.”

“Yessir,” Kuhn mutters, because no matter that the man is decades too old to be hobbling out to some degenerate club like this, he had it beaten into him very young to respect his elders, and he can’t spit out any insult that comes to mind.

Kuhn is a criminal himself, no matter that he has a fucking office and a desk and a lot of bullshit paperwork to get on with in the course of the day. Doctor Lark is bent; the office is bent; all his coworkers are bent, and when Kuhn isn’t doing paperwork and bribes and occasionally being impressed at the new ways their engineers come up with to smuggle guns or blow or cash, he’s roughing up whoever doesn’t pay them.

He's not this sort of criminal, no, but—

Still.

Kuhn follows after the old man, trying to look around him into the club – the big door is closed, and a hulking bulldyke stands in front of it, her arms crossed over her big, square chest that her suit barely fucking contains. When she draws back a slightly hairy upper lip in a snarl, Kuhn doesn’t have it in him not to draw his own teeth back.

Bad dogs, both of them.

“Christine,” says Kasovitz suddenly a second later – the door is open, the old man is hobbling through where Kasovitz is holding the door open for him, and Kasovitz is standing at the big lesbian’s shoulder. She’s holding Kuhn half a foot off the fucking ground, pinned up against the wall, but at Kasovitz’ gentle scolding, she sets him down again. “Let him through, dear. I’ll vouch for him.”

“Behave,” Christine growls down at him, and Kuhn scoffs at her – she raises her hand as if to smack him one, but before she can land the blow, Kasovitz has tugged Kuhn forward by one of the open bits of his looser coat pockets, moved him whilst making barely any contact with him at all.

Kasovitz used to be a clown.

Kuhn doesn’t know how long he’d been a clerk at Croft & Co. before they merged with Werner & Associates, but he knows he was never a fucking soldier, not in the Great War or the one after, no matter that he’s fifty-six or something like it. The fuck sort of exemption is that, being a fucking clown? The fuck was he doing, when men like Kuhn were getting shot at, raked over wire, bombed to smithereens – juggling? Dancing on a wire, jumping off the trapeze, riding fucking elephants?

It’s an open secret, what he is, that he’s a pansy, an invert, at work. It’s illegal, sure, but that doesn’t mean anything at WC – and Hell, isn’t it fucking right, that a homo like him should work at a company now named after a fucking lavatory? – and that it’s disgusting doesn’t mean much more. It grates on Kuhn, that people at work joke about it and that the old prick takes it in his stride, laughs along, even makes his own jokes about being a Wilde type.

He’s not in one of the pastel suits he wears to work, with old-fashioned tailoring and uncomfortably modern cloth, and not in his circus get-up either – there’s pictures of him on his desk at work, of him with his family in the circus – but in a set of trousers, a jumper, a tie. He looks naked, in a way, dressed down. As big a man as he is, heavy in the chest and shoulders with long, loping legs, it feels to Kuhn for a moment that a jumper almost shouldn’t fit him.

As Kuhn follows after Kasovitz, he steels himself for the coming touch, for Kasovitz to touch him properly this time – his shoulder, the back of his neck, his waist, get ready to lunge back at him, no matter that he’s a big, heavy prick. The touch doesn’t come.

Coiled energy prickles under Kuhn’s skin, built up with nowhere to go, awaiting the provocation of Kasovitz perving on him.

“Gonna ask me to buy you a drink, are you, pansy?” Kuhn asks in a sharp undertone, provoking the provocation so that he doesn’t have to have it swinging over his head.

“I don’t drink,” Kasovitz says. “But cheers for the offer.”

Kuhn blinks, and he realises in the moment that he isn’t talking the way he does at the office, that he sounds a lot less like Kuhn himself, all of a sudden – he doesn’t sound like a Londoner at all, but a Manc, a Scouser, maybe.

Before Kuhn can snap that it wasn’t an offer, he doesn’t swing that way and even if he did, he’s pretty sure he could get a younger, prettier model than a fucking has-been cunt in his fifties – respect for one’s elders does not extend to clowns – Kasovitz has picked up a length of coiled rope from a nearby table and stepped away from him.

This speakeasy used to be a public bomb shelter, Kuhn thinks – it’s a sort of tunnel, long and windowless, with rounded walls, but it makes a more than decent basement establishment. There’s a long bar, tables and booths about, small stages throughout. The music travels well here inside the place, but there’s no live band – it’s just a battered old gramophone in the corner, some antique thing instead of a newer record player.

Kuhn suddenly finds himself rooted to the spot as if he’s stepped in tar, his shoes sticking to the word boards beneath him as he follows Kasovitz with his eyes up onto the small stage, and his breath gets stuck somewhere inside him too. Ascending two steps up onto the platform, Kasovitz has gone from uncoiling the rope to trussing up a pretty girl.

No.

No, not a girl – she’s Kuhn’s age or a bit younger, forty, at the eldest. She’s got her eyes closed and her lips are faintly smiling, and she’s stripped down to just a slip and her stockings, her dress and cardigan folded on the edge of the stage, as she leans forward and into Kasovitz’ hands. His long fingers make the rope move fast, make it look alive, serpentine, as it coils around her body. She’s the same height as Kuhn, maybe even taller than he is in her little kitten heels, and Kasovitz is like a giant in front of her, leaning forward to press the rope between her little tits.

Kuhn still isn’t breathing. His chest is aching a bit, distantly, from his lungs not inflating or letting out – he’s held his breath in the bath before, tempted himself with oblivion, but this pain isn’t quite like that. It has softer edges, somehow, and a sweeter taste.

“Lean back,” Kasovitz instructs.

Kuhn was hypnotised once, before the war, before anything. He was fourteen and at a birthday party – Haverford Grey’s, he’s dead, now, was gutted and left hanging from a tree by a grey and dismal battlefield, and Kuhn can still hear the wind whistling and the branch creaking as he swings one way and the other – was a hypnotist.

Harmless stuff.

Keep an eye on the watch, watch it swing, watch the pendulum go one way and then the other, and then he was sweet and easy and standing on a cloud, and all his friends were laughing because apparently he’d done a good ballerina’s twirl, and he’d laughed too, because he’d just felt so relaxed. He hasn’t thought of that birthday party since he saw Have’s corpse swinging and thought of the pendulum swing of the hypnotist’s watch – he hasn’t thought of the calm and the sweet buzz and ease he’d felt for much, much longer. He feels a ghost of that calm down, his head tipping back slightly. Kuhn’s chin raises, his centre of gravity easing a few degrees backwards in response to an order that isn’t meant for him – he’s starting to feel the slightest bit dizzy, but luckily, Kasovitz tells his girl, “Breathe in,” and Kuhn does at the same time she does, feels blessed relief.

He stares, mystified, in a waking dream, as Kasovitz supports his trussed-up girl under her belly and lifts her up like he might his fucking briefcase, tied up like a handbag, her arms and legs behind her, above her, and she’s swinging too. She looks so… peaceful.

She laughs softly as Kasovitz pulls the rope through another one of the rings of a sort of hangman’s frame over the stage, one Kuhn hadn’t noticed a moment ago, and Kuhn watches as she’s eased out of his hold – and fucking Hell, he was holding her in one hand, balancing her in one hand – and made to purely suspend from the frame. Her legs are back, ankles and wrists together, but she’s not hanging from the coiled rope around those.

Kasovitz has made a sort of harness for her, around her chest, her waist and belly, and her weight rests in the cradle of it, and Kuhn wonders when the last time was that he ever, ever felt as strangely relaxed as he does right now, watching this woman tied up in a degenerate hub like this one – he’s tipping slightly forward on his feet, rocking in rhythm with her swinging in the suspension.

Kuhn realises, all at once, that it’s happening all around him.

A fat man with a balding head is leaning back in a chair and two girls – and these are girls, if they’re not boys in dresses, might be at the end of their teens if not their early twenties – are tying him tighter and tighter. Between binding him to the legs and arms of the chair, they’re laughing at him, pinching his cheeks, slapping parts of his flesh, kissing him on the cheeks and the top of his head. Another woman is in suspension at the far end of the hall, hanging from the frame with her legs down and her arms straight out, a mirror of Christ. An older woman has a younger one over her knee and is smacking her across her arse, making the pale cheeks of her flat arse wobble with each blow, and they’re aglow with the heat and redness of it.

“You can have fifteen minutes,” Kasovitz says, checking his pocket watch and gently touching the young woman’s cheek. “And then I’ll bring you down.”

“Can it be twenty?” she asks, her voice husky, but it doesn’t sound seductive, not that Kuhn’s any real judge or expert – it just sounds sleepy to him.

“Seventeen.”

“Eighteen.”

“Seventeen and a half,” says Kasovitz, with a stern movement of one index finger, and when the woman laughs, she gently sways in her bonds, and Kuhn follows after Kasovitz as he goes toward the bar. “Two barley waters, please,” he says, and Kuhn stands there, his hands at his sides, as he watches the young man behind the bar pour from a jug.

He's incredibly grateful, all of a sudden, to hear the clink of ice against the glass – it’s warm outside, and it’s even hotter here inside, and more humid, too. When the glass is pushed toward him, he drinks from it greedily.

“You live in Battersea, don’t you?” Kasovitz asks. “Did you walk all the way here?”

“Couldn’t sleep,” says Kuhn. “Never been one for counting sheep. Came here to count fairies instead.”

Kasovitz’ lips twitch, and he takes a sip from his own drink, gesturing for the man behind the bar to replenish Kuhn’s glass, which he does. It occurs to him to complain, to ask why the fuck he’s drinking barley water instead of beer or ale, whether Kasovitz drinks or not, but he doesn’t want to drink anyway, not tonight. Kuhn hops up onto the stool – Kasovitz doesn’t have to do that, just leans back into the one beside him, and Kuhn slowly scans the hall up and down, at the play these people are all having with each other.

“There once was a queer from Khartoum…” says Kasovitz in an undertone, narrating the view for him, and Kuhn’s lips twitch despite himself, and he looks up at the older man’s face. He has round features – big, round eyes with heavy lids, a crescent to his lips, an oval-shaped face. He has thick, dark hair, and he usually has it pomaded at work – he has it washed of pomade, neatly parted, and now they’re not flattened down, the usual waves are made up of bouncing curls instead.

“I saw you walking,” says Kuhn. He doesn’t know why he says it, doesn’t know why it occurs to him to share it – why the fuck should he? But he does. He still feels a bit tense under his clothes, but Kasovitz isn’t touching him, isn’t reaching for him, and Kuhn isn’t entirely relaxed – he doesn’t know if he’s been entirely relaxed in the last twenty fucking years – but he trusts, somehow, that Kasovitz isn’t going to reach and touch him. “I’ve been walking around for an hour or two, and I saw you, recognised you. Thought you’d be out on one of the greens or playing house at this time of night, not coming into a fucking place like this.”

“Playing house?” Kasovitz repeats, raising his thick eyebrows. “What were you hoping, young man, that you’d find me in a cottage waiting for you?”

“Not my thing,” Kuhn mutters.

The old man, the one that spoke to him on the way in, has another older man on his knee – he’s plump, has a sort of prettiness despite his age and his weight, has long eyelashes and very pink lips. The one with the cane is slowly winding ribbon around him with quavering, frail fingers, tying bows about his neck, around his belly, making a sort of harness of the violet silk, laying it down flat against Lippett’s smooth, hairless skin.

“Mr Salford, he’s a haberdasher,” Kasovitz supplies. “Always brings his own ribbons, has more of a care for those than rope. Mr Lippett was a painter’s model as a young man – he still enjoys to be made into something fancy, into something pretty.”

“They’re both so fucking old,” Kuhn says.

“Yes, well,” Kasovitz murmurs, taking another little sip of his drink, “We’re all getting fucking old, at the end of the day.”

Kuhn watches as Salford ties little bows through the rings piercing Lippett’s plump tits – they’re bigger than the ones on the woman Kasovitz has set to dangle, look plush and soft. They wobble a bit when Salford tickles Lippett’s side, making him laugh.

“I didn’t know you were a Scouser,” Kuhn says. “Why’d you do that accent at work?”

“You know what you Londoners are like,” Kasovitz retorts, shrugging his shoulders. “People are liable to think I can’t read and write at all, realising I learned my English in Liverpool. I do the posher accent in the office, and it keeps people on task. Don’t think I don’t know you don’t go a little Cockney now and then, when you think it will have more of an impact.”

“Learned your English?” Kuhn repeats. “Thought you might be a Kraut, with a name like Kasovitz.”

“My family left our troupe to join another when attitudes toward Jews in Germany, in the rest of Europe, became more dangerous, and then we came to England to perform here. Circuses are made for outcasts – Gypsies, Jews, cripples, dwarves, freaks and untouchables of all kinds.” Kasovitz’ voice is quiet and even – he has a nice voice, and Kuhn finds he actually finds his Scouser’s lilt more appealing than the more neutral, posher voice he’s heard here and there from him. “That’s always been true, and always will be. But it was harder here in England, as an invert, a homosexual – and apart from that, the magic was lost for me, I think. I stayed in Liverpool as the circus moved on, enrolled in a secretarial course – I’d learned to do our books, had managed our travelling papers, different ownership papers, contracts. People are always accusing circuses of thievery, so one learns to keep these things in good order.”

“So you’re not actually a Scouser, then,” is what Kuhn takes from this.

“I was born outside of Szeged, actually.”

“Where’s that?”

“Hungary.”

“And you all just… travelled around? The circus you were in, it was all Jews?”

“Not all, no, but a few of us.”

“You all survived?”

Kasovitz’ expression doesn’t change, but he gazes at Kuhn’s face, looks across at him unblinkingly for a few moments. “Most of us,” he says quietly. “My family, for the most part, except for an aunt and uncle I had who were entertainers in Berlin – they were brought to a camp. My uncle died there – my aunt was kept alive, made to perform for the guards, you see. She was a broken woman, after. My mother went to look after her for a little while, but she died not long after the end of the war – typhoid fever. There was another Jewish family with us, half of them went to America, the other half evaded capture for a while, and then two of them, fellow clowns…” He trails off, slowly shaking his head, and exhales. “The rest did survive, they’re in Israel now. All told, those in my closest circle were far luckier than most Jews. Traveling life gave us means of egress, ways to hide, that others didn’t have – and in the circus, we look after our own. We weren’t disposable or undesirable for our Jewishness, as we were and would be elsewhere.”

“I didn’t really know many Jews, before the war,” Kuhn says. He doesn’t know why he says this, either. He doesn’t talk to anybody, really – he has pints with the lads after a job sometimes, but mostly he doesn’t talk, just listens, laughs at a good joke, though there’s never many of those. “My family had some refugees as servants, and then we were deployed, I did meet some Jews – in Stalags, mostly. Some Poles helped us out, once, Polish Jews, that was in France.”

“What are your family, Catholic?”

“C of E.”

“You’re not religious?”

“No, never.”

“Nor am I.”

“You use to be?”

“Before the Shoah? No, not really. I used to think as a young man I’d have time and interest in religion when I was old, that I’d get more interested in spending time with God. And then He let that happen. And I thought… fuck Him. Let Him burn for all I care.”

“One of our priests was the touchy-feely type,” Kuhn says. “He slid his hand down my back once when I was in the church library, and I ripped his dog collar off, knocked my head into his nose. Didn’t break it, just bloodied his lip.”

Kasovitz looks at him with what seems to Kuhn to be a very keen interest, resting his rounded chin on the palm of one of his big, strong, long-fingered hands. In deliberate tones, he asks – sort of snidely – “And a priest stroking your back, young man, you think that’s roughly equivalent to my seeing millions of my people slaughtered?”

“No,” says Kuhn plainly. “But I headbutted a priest. Thought you’d like the point against God. ‘Scuse me for breathing.”

Kasovitz laughs. It seems to take him by surprise – he covers his mouth with his hand, his eyes very wide and almost watering, and it’s a good laugh, very loud. It’s not like the politer, snider thing he keeps in the office, all superior and quiet – this is a clown’s laugh, Kuhn thinks. He likes it.

“I suppose you’re right,” he says, a bit breathlessly, when the laugh passes. “Thank you for that, Mr Conrad. I appreciate the effort.”

“Kuhn,” says Kuhn.

Kasovitz blinks his big brown eyes. “Beg pardon?”

“That’s what they called me, the POWs. They said Conrad was too grand for a little fella like me, and when I told them my name was Arthur, they said that was too English. So, Kuhn.”

Kasovitz sips from his drink, and then asks, “Is that what you did in the war, liberate camps? Doctor Lark, he mentioned to me once that you weren’t in the trenches, seemed to imply that was why you were so…”

“Fucked up?”

“Brittle.”

“Brittle,” Kuhn repeats, and he laughs a bit, although it comes out kind of staccato and scattershot, like gunfire, and his ribs feel like they’re rattling, his chest aching. There’s a kind of acrid taste in the back of his throat, the threat of vomiting – he gets that threat a lot, but he doesn’t actually throw up much these days. It’s composure, except that composure’s not all it is.

Better out than in, his nanny used to say. You’re meant to vomit when you’re ill. It’s getting the poison out, throwing it up. The poison that’s in him now is in too deep to throw it up. Vomiting doesn’t make any difference.

“I didn’t really liberate anything,” Kuhn says. “I was little, and fast, and nasty. I just went and killed a lot of people – Krauts, mostly, officers and soldiers. Like a fox or a weasel, I went into the coop sometimes alone, more times with the squad I was with, never more than six of us. Poisoned beer, or food. Slit throats. Sometimes it wasn’t them, sometimes it was collaborators – never liked that word. Too much choice in it.”

“Not much choice in that war, was there?”

“No.”

Kasovitz is looking at him. Kuhn can feel it before he looks up and observes it, feels the way that Kasovitz’ gaze is flickering over Kuhn’s face, down the length of his nose, into the shadows of his eye sockets, down his jaw, up to his ears, to his hair, then down his neck, down to his chest, the clothes he’s wearing – just a vest under a battered, very light summer jersey.

“What?” Kuhn asks, finally.

“The other men in that squad you mentioned,” Kasovitz murmurs. “Were they— men like you?”

“Men like me?”

“Men born so close to Clapham Common. Or Battersea, for that matter.”

“Not really,” Kuhn mutters. “Doctor Lark made the same guess you did. A lot of them were burglars, criminals. A few intelligence officers, sometimes, but we weren’t intelligence, we weren’t spies.”