#Jarmila

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Video

Jarmila Novotna by Truus, Bob & Jan too! Via Flickr: German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 6837/1, 1931-1932. Photo: Walter Firner, Berlin. Czech soprano Jarmila Novotná (1907-1994) was one of the world-renowned opera luminaries of the 20th Century. Her film appearances were unfortunately few and far between. Jarmila Novotná was born in in Prague, Czech Republic in 1907. She studied singing with Emmy Destinn. In 1925, the 17-years-old Novotná made her operatic debut at the Prague Opera House as Marenka in Bedřich Smetana's Prodaná nevěsta (The Bartered Bride). Six days later, the lyric soprano sang there as Violetta in Giuseppe Verdi's La traviata. The following year, she made her film debut in the silent film Vyznavaci slunce/The Sun Disciples (Václav Binovec, 1926), starring Luigi Serventi. In 1928 she starred in Verona as Gilda opposite Giacomo Lauri-Volpi in Verdi's Rigoletto and at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples as Adina opposite Tito Schipa in Gaetano Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore. In 1929 she joined the Kroll Opera in Berlin, where she sang Violetta as well as the title roles of Giacomo Puccini's Manon Lescaut and Madama Butterfly. When talking pictures arrived, she headlined in German films like Brand in Der Oper/Fire in the Opera House (Carl Froelich, 1930), with Gustaf Gründgens, Der Bettelstudent/The Beggar Student (Victor Janson, 1931), and the film version of The Bartered Bride, Die Verkaufte Braut (Max Ophüls, 1932). Hal Erickson at AllMovie on Die Verkaufte Braut (1930): “The original libretto, involving the comic misadventures of two mismatched couples, is given a respectable amount of attention, but the film's biggest selling card is the photographic dexterity of Max Ophuls, who never met a camera crane he didn't like. Since filmed opera was seldom big box-office in 1932, Ophuls concentrates on the farcical elements of the story; especially worth noting are comic contributions by Paul Kemp and Otto Wernicke, who seldom let their German film fans down. Curiously, star Jarmila Novotna, whose ‘live’ appearances in The Bartered Bride were much prized by contemporary critics, doesn't come off all that well in this film version.” Other films followed such as Nacht Der Grossen Liebe/Night of the Great Love (Geza von Bolvary, 1933) with Gustav Fröhlich. In January 1933 she created the female lead in Jaromir Weinberger's new operetta Frühlingsstürme (Spring Storms), opposite Richard Tauber at the Theater im Admiralspalast, Berlin. This was the last new operetta produced in the Weimar Republic, and she and Tauber were both soon forced to leave Germany by the new Nazi regime. Jarmila Novotnà returned to Czechoslovakia to star in the film Skrivanci pisen/Lark's Songs (Svatopluk Innemann, 1933). In 1934, she left for Vienna, where she created the title role in Franz Lehár's operetta Giuditta opposite Richard Tauber. Her immense success in that role led to a contract with the Vienna State Opera, where she was named Kammersängerin. She also appeared there with Tauber in The Bartered Bride and Madama Butterfly. In the cinema, she starred in the Austrian operetta film Frasquita (Karel Lamac, 1934) with Heinz Ruhmann, the Austrian romantic thriller Der Kosak und die Nachtigall/The Cossack and the Nightingale (Phil Jutzi, 1935) with Iván Petrovich, and in the French-British operetta film La dernière valse/The Last Waltz (Leo Mittler, 1935), which was made in two language versions. She then left the film industry to concentrate on her stage work with the Viennese State Opera. After the Anschluss of Austria, she had to leave Vienna. In January 1940 she made her debut with the Metropolitan Opera in New York, as Mimí in Puccini's La bohème. From 1940 to 1956, Novotná performed regularly at the Met. In 1946 she returned before the cameras in a straight dramatic role in the Hollywood production The Search (Fred Zinnemann, 1946), starring Montgomery Clift. The Search is a semi-documentary film on the plight of WWII orphans. Novotná played a Czech mother who has lost contact with her young son when they were in Auschwitz and she now travels from one refugee camp to another in search of him. Novotna's then played turn of the century diva Maria Selka in the biopic The Great Caruso (Richard Thorpe, 1951), featuring Mario Lanza. The film traces legendary tenor Enrico Caruso's ascension from adolescent choir singer in Naples to the uppermost ranks of the opera world. Mario Lanza's tenor voice made this film one of the top box-office draws of 1951, and this helped to popularize opera among the general public. On TV she appeared in The Great Waltz (Max Liebman, 1955), which charts the life and times of composer Johann Strauss, Jr. She also played Hans’ mother in the TV musical Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates (Sidney Lumet, 1958), starring Tab Hunter. Her last screen appearance was as an interviewee in the documentary Toscanini: The Maestro (Peter Rosen, 1985). At 85, Jarmila Novotná passed away in 1994 in New York. Sources: Hal Erickson (AllMovie), Wikipedia, and IMDb.

#Jarmila Novotna#Jarmila#Novotna#Actress#Actrice#European#Film Star#Cinema#Cine#Kino#Film#Picture#Screen#Movie#Movies#Filmster#Star#Vintage#Postcard#Carte#Postale#Cartolina#Tarjet#Postal#Postkarte#Postkaart#Briefkarte#Briefkaart#Ansichtskarte#Ansichtkaart

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Valentine's Day from Jarmila!

#oc#original character#genshin impact#genshin impact oc#jarmila#art#digital art#artwork#artist on tumblr#tumblr artist

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

June 5, 2023:

Red Primary, Fae, Sludge.

Jarmila of Vacrana’s clan!

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Explore Bolgheri Cypress Way by © Jarmila

#©#jarmila#bolgheri#cypress#way#nature#italy#tuscany#castagneto#carducci#viale#dei#cipressi#canon#boulevard#cypresses#strada#provinciale#16d#sp#39bolgheri#oratorio#di#san#guido#via#aurelia#provincia#livorno#toscana

0 notes

Text

Jarmila Čihánková Painting No. 35 1965 Olej na plátne 140 × 107 cm

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

#The Search#Montgomery Clift#Aline MacMahon#Jarmila Novotná#Wendell Corey#Ivan Jandl#Fred Zinnemann#1948

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jarmila Gerlová and unidentified man in I Killed Einstein, Getlemen (Zabil jsem Einsteina, pánové) 1970, dir. Oldřich Lipský IMDB

#Czech#čumblr#Czech cinema#Czech film#I Killed Einstein Gentlemen#Zabil jsem Einsteina pánové#Jarmila Gerlová#Oldřich Lipský#Miloš Macourek#Josef Nesvadba#film#film edit#classicfilmedit#comedy#science fiction#romance#campy#psychotronic film#1970s#actor#actress#Czechia#Czech Republic#Czech pop culture#gif#dailyworldcinema#lgbtq

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Jael Jarmila

#studyblr#books and writing#booklover#books & libraries#student life#book blog#study blog#studygram#bookblr#author#my poem#student#poetry#poem#poets on tumblr#poetsandwriters#original poem#writers and poets#first home by Jael Jarmila

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maryša - 26.10.1956 Jarmila Krulišová (Maryša). Foto: Jaromír Svoboda

#maryša#jarmila krulišová#1922-2006#czech actresses#czech republic#actress#actresses#photographic portraiture#portraits of women#women#actors

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

I didn't expect to get emotionally involved in almost hundred years old psychological novel about a tragic romance, written by actively communist writer, but here I am, I guess...

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

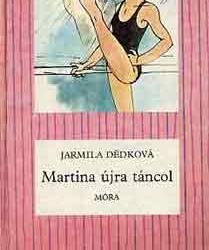

Jarmila Dědková: Martina újra táncol - a 244. epizód

Robog tovább a pöttyös-csíkos vonat: legújabb választásunk egy valószínűleg kevésbé ismert szerzőre/regényre esett, ugyanis Jarmila Dědková cseh írónő Martina újra táncol című könyvét olvastuk. (Ezzel el is értünk sorozatunk első külföldi szerzőjéhez!) Ahogy a cím is sejteni engedi, Dědková könyve a balett világába enged betekintést, bár abban mindketten egyetértettünk a végén, hogy a kedvünket…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

What a points race by Jarmila Machacova. None of the other girls tried to follow her when she first attacked. She spent 10+ laps in the front and it looked like she was doing it for nothing. But then she accelerated in the last lap and won the last sprint, earning herself the bronze medal. Nice done!

0 notes

Text

The Czech state threatened to institutionalize my children if I didn't have an abortion, later I learned they also sterilized me

Jarmila Adiová is one of many forcibly sterilized women who are fighting with the lifelong repercussions of that traumatic experience in the Czech Republic. In an interview for ROMEA TV, she reveals how pressure from physicians and social workers led to more than one irreversible intervention in her life.

Adiová has applied for the compensation of CZK 300,000 [EUR 12,000] currently being offered by the Czech state and is still waiting to see whether it will be awarded to her. For the time being the official deadline for filing requests for such compensation is 2 January 2025.

Some politicians are now proposing to extend that deadline by another two years, though. Adiová was living a contented family life with her husband and five sons before the intervention.

The entire family was looking forward to their next child, whom they all hoped would be a little girl. “My husband and I had been preparing for it to be a little girl. He actually looked forward to that, he was glad and kept saying ‘I hope it will be a girl and not another boy’, because we already had five sons. I was also looking forward to it very much,” Adiová told ROMEA TV.

“We were a normal, functional family, the children were doing well and everything was fine,” she recalls their life before the intervention. However, their plans were thwarted by pressure from social workers threatening to institutionalize her children unless she aborted her pregnancy.

“The social workers started coming to our home and they were always looking for something wrong, they deliberately invented stories to see whether our household lacked something it shouldn’t. Back then it was the case that if they saw you had more children, they immediately told me that I was ‘giving birth like a cat’ and that they would not keep disbursing me welfare benefits all the time. They proposed that I get rid of the child I was expecting. They said that if I didn’t, they would take my other children and put them in an institution. I was out of my mind with fear, my husband was, too. We didn’t want to do it at all, but ultimately they forced me to do it so I could keep my five children at home,” Adiová told ROMEA TV.

After the abortion, Adiová found out that she would never conceive again. Without fully understanding the repercussions, she had been forced to undergo sterilization as well as an abortion.

“I had no idea that I would no longer be able to have children. It was not until the operation was over that my husband and family told me it was irreversible. That shock marked me for life,” Adiová described.

To this day Adiová is being treated for the longstanding mental problems resulting from that experience. Suspicions that Romani women were being subjected to forced sterilizations in the Czech Republic were raised in 2004 by the European Roma Rights Centre.

The illegal sterilizations were undertaken in the former Czechoslovakia and in the Czech Republic for decades and were most often performed on Romani women. They were subjected to pressure and to threats that their children would be institutionalized unless they underwent the surgery and were not properly informed about the nature of the surgery being recommended to them.

Dozens of women contacted the ombudsman about their treatment and several have also sued in court. According to the compensation law now in effect in the Czech Republic, victims have been able to request compensation since 2022, but the opportunity to apply ends on 2 January 2025.

Politicians in the Czech Republic agree it is necessary to extend this opportunity by another two years. Just like other victims of forced sterilizations, Adiová has applied for the CZK 300,000 [EUR 12,000] in compensation being offered.

Adiová does not yet know whether she will be awarded the compensation. “The money will not heal these wounds. I wanted my sons to have a sister. They took that chance away from me, though,” she told news server ROMEA TV.

She hopes her story will support other women who are fighting for justice: “This is not just about me, but about all the women who went through this. All we wanted was to have families and children, but they denied us that.”

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Autor:

Jarmila Čihánková

Názov diela:

Protismery

Rok:

1967

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

!!!! Sharing a deeply and dearly important post and article about the years of mistreatment and forced sterilization many Romani women have and still face around the world !!!

!!! Information initially shared by Khamorri on Twitter !!!

Jarmila Adiová, a Czech Roma woman, speaks openly regarding her experiences with being forcibly sterilized after being pressured to terminate a pregnancy by social workers.

“..They proposed that I get rid of the child I was expecting. They said that if I didn't, they would take my other children and put them in an institution … We didn't want to do it at all, but ultimately they forced me to do it so I could keep my five children at home.” recalls Jarmila.

Article and interview below, article hosted by romea.cz

#Romani resources#romani representation#important Romani informations#Romani rights#Romani News#important

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lassú Haladás a Törvényes Határokon Belül

1905 végén ismerte meg későbbi feleségét, Jarmila Mayerovát. Mivel a lány szülei nem tartották megfelelő férjnek az anarchista írót, a szerelmes író megpróbált visszalépni az anarchizmustól, és inkább állásba lépett. Amikor az írót ismét letartóztatták, a lányt szülei vidékre vitték, remélve, hogy ezzel kapcsolatuknak vége szakad. Ez ugyan nem történt meg, de végleg szakított az anarchizmussal, és kizárólag az írásnak szentelte magát. 1910-ben a Svět zvířat (Állatok Világa) című lap szerkesztője lett. Az Állatok Világá-tól azonban rövidesen elbocsátották az általa kitalált állatokról írott cikkei miatt. Az első világháború alatt, 1915 februárjában belépett a hadseregbe. A fronton töltött rövid idő után szeptemberben megadta magát az oroszoknak. Fő művének második változatát már Kijevben írta 1916–1917-ben, ahol – mint korábban is – bohém életet élt, kocsmákban tisztekkel verekedett, és ha a kávéházban vagy máshol régi cseh katonatársakkal találkoztak, arra a kérdésre: „Mit csinálsz te itt?” azt a választ adták: „Elárultam a császár őfelségét!”. Még korábban Prágában megtanult magyarul, és több, jórészt kétnyelvű hadifogolylapot is szerkesztett. A helyi pártszervezet gyanakvással fogadta, így hamarosan visszatért korábbi, bohém életmódjához. Az író nem volt túl népszerű, mivel árulónak és bigámistának tekintették. Megalapította a Lassú Haladás a Törvényes Határokon Belül pártot, és az így összegyűjtött pénzt kocsmázásra fordította. 1921 márciusában kezdett fő műve végleges változatának megírásához. Részvénytársaságot alapított a forgalmazására, kiadótársaival a mű első részét füzetenként árusították kávéházakban, vendéglőkben, mivel az író bigámiapere miatt nem akadt olyan kereskedő, aki vállalni merte volna a mű megjelentetését. Az első rész közönségsikert aratott, így a második rész kiadására már jelentkezett vállalkozó. Ekkor már súlyos beteg volt, szervezete nem bírta tovább a bohém élet terheit. A regény utolsó fejezeteit betegsége miatt már csak diktálni tudta. 1923-ban, tüdőtágulás és szívbénulás következtében, nem egészen 40 évesen meghalt. A fő mű tehát befejezetlenül maradt, a hiányzó harmadik rész újságíró barátjának, Karel Vaneknak a munkája. Utolsó szavai a következők voltak: „Sohasem hittem, hogy ilyen nehéz meghalni.”

Rendkívüli memóriája, hosszú európai vándorlásai valóságos poliglottá tették. Jól beszélt magyarul, németül, lengyelül, szerbül, szlovákul és oroszul. Franciául és egy cigány nyelvjárásban is ki tudta fejezni magát, oroszországi tartózkodása alatt pedig tatárul és baskírul is megtanult, emellett foglalkozott a kínai és a koreai nyelvvel is. In és in. Jaroslav Hašek: Hogyan kereskedtem kutyákkal? részlet, V. fejezet

Közeledett a karácsony. Időközben a fekete spiccet hidrogénperoxid segítségével megszőkítettük, a fehér spiccet pedig ezüstnitrát-oldattal feketére festettük. Operáció közben mindkét kutya szörnyűségesen vonított, ami igen hatásos reklám volt, mert a környező házak lakóiban azt a hitet ébresztette, hogy a Kynológiai Intézetben nem két kutya van, hanem legalább hatvan.

Kutyánk tehát nem sok került, annál inkább bővelkedtünk kutyakölkökben. Csizseken (alkalmazottja) teljesen eluralkodott az a kóros nézet, hogy a jólét alapja a kutyakölyök, így aztán karácsony előtt télikabátja zsebében tömegesen hordta haza a kiskutyákat. Elküldtem, hogy szerezzen egy bulldogot - hazahozott egy féltucat borzeb-kölyköt. Szálkás szőrű pincsit venni indult - kis foxikkal tért vissza. Összesen harminc kutyakölykünk volt, és vagy százhúsz koronát fizettünk ki különféle foglalók címén. Az az ötletem támadt, hogy a prágai Ferdinánd utcán ünnepek előtt kibérelek egy bolthelyiséget, a kirakatba karácsonyfát állítok, alája szalaggal díszített kölyökkutyákat, s cégér helyett a következő szöveget helyezném el a bejárat fölött: "Boldoggá teszi gyermeke karácsonyát, ha egészséges kiskutyát ajándékoz neki." A helyiséget kibéreltem. Vagy egy héttel az ünnepek előtt.

- Csizsek - mondom -, elviszi a kiskutyákat a prágai boltba, vásárol egy szép nagy karácsonyfát, felállítja a kirakatban, alája mohát rak, és ügyesen elrendezi a kiskutyákat. Megértette?

- Megbízhat bennem a főnök úr. Öröme lesz bennük.

A kiskutyákat ládába rakta, a ládát kézikocsira, és felkerekedett. Délután magam is elmentem a Ferdinánd utcára, hadd teljék örömem bennük.

Már messziről láttam, hogy a kirakat előtt nagy tömegben állnak az emberek, kölyökkutyáim iránt tehát jelentős érdeklődés nyilvánult meg. Amikor közelebb mentem, dühös kiáltásokat hallok:

- Hallatlan állatkínzás! Hol a rendőrség? Miért tűri ezt a bitangságot?

Nagy nehezen keresztülnyomakodtam a tömegen. A kirakat előtt egyszerre megroggyant a térdem.

Csizsek, hogy örömet szerezzen nekem, vagy két tucatnyi kutyakölyköt fölaggatott a karácsonyfa ágaira, úgy, ahogyan a szaloncukrot szokták. Ott lógtak szegény kis ártatlankák, kifittyedt nyelvvel, mint a felmagasztalt középkori haramiák. A karácsonyfa tövében pedig ott díszelgett a tábla:

"Boldoggá teszi gyermeke karácsonyát, ha egészséges kiskutyát ajándékoz neki."

Ezzel a karácsonyi kutyavásárral ért véget a "Kynológiai Intézet" története.

8 notes

·

View notes