#Japanese grammar

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#japanese#learning japanese#langblog#japan#langblr#japanese vocab#manga#anime#tumblr language#japanese vocabulary#japanese grammar#japanese langblr#japanese language#japan travel#asian#Asia

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

[grammar] うちに入らない

Upon reading Murakami’s 1Q84, I came across the following sentence:

鍵はかかっていたが、鍵のうちには入らないようなものだった。

I couldn’t make sense of the second part of the sentence, so I asked my Japanese friend for help.

Apparently, Nのうちに入らない means something like “can’t be regarded as N” or “not really a N”. So, you might translate the sentence as, “It was locked, but it wasn’t much of a lock.”

This phrase seems to be more often used with verbs, as in Vたうちに入らない, rather than with nouns.

My friend also mentioned that Japanese teachers often use this phrase when students haven’t done something properly, e.g., cleaning the classroom:

こんなのやったうちに入らないだろ! You can’t seriously think this counts as cleaning, right?!

When I thanked my friend for the help, he replied with:

こんなの助けたうちにも入らねーぜ。 This doesn’t even count as helpin��, man.

After some further research, I discovered that this is actually considered an N1-level grammar point.

Has anyone else encountered this phrase before? If so, let me know the context in which you’ve seen it!

#japanese language#learning japanese#japanese langblr#japanese grammar#jlpt#jlpt n1#japanese#haruki murakami#1q84#日本語#日本語能力試験#n1

168 notes

·

View notes

Text

The difference between あのー and えーっと

As I touched on in my japanese goncharov post, it’s amazing how much novel research, entertainment, and art are locked behind a language barrier. Even though as english speakers, we are privileged to have many things translated into our language, it’s a simple fact that most things will not be translated into most languages.

I am a huge fan of ゆる言語学ラジオ, a japanese podcast about linguistics. The hosts recently released a book, 言語沼, which goes into detail about some of the subconscious rules native japanese speakers follow but aren’t consciously aware of (an english equivalent might be that adjective-ordering rule we follow e.g. big brown cow, not brown big cow). I’m finding it fascinating, and I wanted to discuss some of it here in english, because I think people learning japanese would find some of these things really useful. It’d be a shame if this knowledge stayed stuck behind the japanese language barrier when the people who would find it the most useful can’t speak japanese fluently enough to read it!

The book talks about how most Japanese people will think of 「あのー」 and 「えーっと」 as having the exact same meaning - they’re both “meaningless” filler words. Despite their belief that they’re the same, those same native speakers will subconsciously only use あのー in one particular type of situation and 「えーっと」 in another, and even feel confused or annoyed if they hear another speaker use one in the wrong context.

So what’s the actual difference? 「えーっと」 is used when the speaker is taking time to remember or solve something. For example, the following exchange is very natural:

Person A: 7 x 5は? Person B: えーっと、35だ

This makes it a pretty versatile filler word! You can use it pretty much anywhere. Another example would be when you’re talking to yourself, trying to remember where you left your keys.

えーっと、鍵どこ置いたっけ?

On the other hand, あのー is much more specific. It can only be used when you’re taking time to figure out the best way to phrase something. For example, when you’re trying to get a stranger’s attention.

あのー、ちょっといいですか?

In contrast, if Person A was addressed with 「えーっと、ちょっといいですか?」by Person B, they’d feel it was rude because instead of considering how to say something, B is considering what to say, which gives the impression that they hadn’t even figured out what they needed to ask before addressing Person A.

This gives 「あのー」 a more ”polite” feeling than 「えーっと」, even though neither is actually more polite than the other. They’re just used in different circumstances.

Let’s quickly look at the example with the lost keys again. If you replace the filler word:

あのー、鍵どこ置いたっけ?

It is very unnatural. The authors of the book jokingly say that it sounds like you’re talking to a ghost, because 「あのー」 is only used when you’re figuring out how to phrase something, and you wouldn’t worry about that if you’re talking to yourself.

Also, did you know even japanese children properly use each filler word in the correct situation? Despite almost all japanese people (even as adults) being unaware of this rule, they’re subconsciously abiding by it even as children - just from listening to their parents follow the same rules!

It really is amazing how good your subconscious mind is at acquiring language, and how terrible your conscious mind is at it. If you’re not already, I highly recommend integrating a lot of simple language content (e.g. youtube, kids shows, etc) into your study routine - listening to people talk is simply the fastest way to become fluent in your target language.

#langblr#japanese#language learning#language acquisition#japanese language#language#linguistics#learning japanese#japanese grammar#jimmy blogthong#official blog post

506 notes

·

View notes

Text

接続詞(せつぞくし)

conjunctions - words that are used to link phrases together

情報を加える // Adding information:

しかも besides そのうえ moreover, on top of that さらに moreover, on top of that そればかりか not only that, but also... そればかりでなく not only that, but also...

情報を対比する // Putting into contrast:

それに対して in contrast 一方 whereas

他の可能性・選択肢を言う // Giving alternatives:

あるいは or perhaps (presenting another possibility) それとも or (presenting another option within a question)

結論を出す// Drawing a conclusion:

そのため for that reason したがって therefore そこで for that reason (I went ahead and did...) すると thereupon (having done that triggered sth. to happen) このように with this (adjusting a conclusion to the arguments given beforehand) こうして in this way

理由を言う // Giving a reason:

なぜなら...からだ the reason is というのは...からだ the reason is

逆説を表現する // Expressing a contradiction:

だが however, yet, nevertheless (contradicting what one would have expected) ところが even so (spilling a surprising truth) それなのに despite this, still それでも but still (despite a certain fact, nothing changes)

説明を補う // Amending one's explanation:

つまり that is, in other words (saying the same thing using different words) いわば so to speak (making a comparison) 要するに to sum up, in short

説明を修正する // Revising one's explanation:

ただし however (adding an exception to the information stated beforehand) ただ only, however もっとも however (obviating any expectations that might arise through the previous statement) なお in addition, note that (adding supplementary information)

話題を変える // Changing the subject:

さて well, now, then (common in business letters after the introductory sentence; is often ignored in tranlations) ところで by the way

#文法#grammar#conjunctions#japanese grammar#jlpt n2#japanese langblr#japanese language#language#japan#japanese#japanese vocabulary#langblr#linguistics#studyblr#study blog#studyspo#study motivation#study aesthetic#study notes#learning japanese#nihongo#日本語#日本語の勉強#light academia#light acadamia aesthetic

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N5 - している [Part 2]

Hey everyone, welcome to Part 2 of talking about している. This N5 grammar point is very basic but also very important. Let’s get into it shall we!

But first, here is your vocabulary:

【English Helping Verbs】

As I mentioned in Part 1, the “して“ in している can stand for any verb in て form. Sometimes it is actually する, but most times it will be some other verb.

Ok great, but what is the いる part?? Take a look at the following English sentences:

① Traffic accidents often occur here.

② I am eating.

③ The window is open.

Two of these sentences have both a helping verb and a main verb. In #1, there is only a main verb, which is “occur”. In #2 the main verb is “eating” and the helping verb is “am”. In #3 the main verb is “open” and the helping verb is “is”. Notice that one of the main verbs has the -ing suffix while the other two don’t. Make a mental note of this for later. 😉

【The いる in している】

Japanese also has helping verbs. Allow me to introduce you to one of the most common ones: いる!

The いる helping verb* adds nuance to the main verb. But here’s the thing - there are different versions of いる!In the している Part 1 article, you actually saw what I call the いる of Repetition. This いる does not translate to the -ing form of our verbs in English. If you see よく起きている for example, you should think “often occur(s)”. This is similar to example #1 above.

Examples #2 and 3 are not actions of repetition. For them, we need the other いる, which I call the いる of State or Condition. This いる sometimes makes us use that -ing suffix in our English translations. So if you just see 食べている, by default it would mean “started eating and then stayed in that state for some period of time”. Instead of all that, in English we would simply say “is eating”. This is similar to example #2 above.

開く is a different type of verb than 食べる**. Because of this, the いる of State or Condition does not lead to us using the -ing form. In this case, something is open and stays in that state for some period of time. We don’t say “is opening”. Instead we just say “is open”. For verbs like 開く, their English translations won’t use that -ing form. Instead they will be like example #3 above.

The key to the している grammar point is understanding what kind of main verb you have, and then which helping verb いる you are reading/hearing!

【いる of State or Condition】

Here are some examples where the helping verb いる expresses a state or condition.

This is how you say example #3 in Japanese.

= Tom is currently in the Philippines.

Interestingly, you could also say the following:

⑥ トムはフィリピンに来ています。***

⑦ トムはフィリピンにいます。

#5, 6 and 7 all say that Tom is in the Philippines but the nuance is different in each of them!

#5 says that Tom went to the Philippines and stayed there. This means that the speaker is NOT in the Philippines. On the other hand, #6 says that Tom came to the Philippines and then stayed there, meaning that the speaker is also there. #7 simply says that Tom is in the Philippines. We don’t have any information about where the speaker is located.

= Mizuki is wearing a white skirt and hat.

#8 has several things that I want to point out: First is that the て form of a verb can mark the end of a comment. Example 8 has two comments of equal value. This is one version of a Japanese compound sentence.

The second thing is that the ending helping verb can actually apply to TWO DIFFERENT main verbs! Native speakers hear #8 and understand the verbs to be both はいています as well as かぶっています.

The last thing is that verbs connected to clothes are very interesting. When you attach the helping verb いる, they can sometimes express the state of wearing something. However, in some contexts they can instead express the action of putting something on. For the N5 level luckily you won’t have to distinguish between wearing and putting on clothing so no worries. It is good to keep this tidbit in the back of your mind for the future though.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it. Now you know that the している grammar point can express several situations. You could have:

・Repetition - there will be a word/phrase that indicates that the action happens repeatedly. The English translation won’t use the -ing form of a verb

・State or a Condition - there MAY or may not be a word/phrase indicating repetition. The main thing to focus on is whether the verb is an action verb or not. This will help you decide if you need -ing or not.

As always, keep your eyes and ears open for different kinds of examples and try to notice patterns. You can do it!

Rice & Peace,

– AL

👋🏾

*I purposely say “the helping verb いる“because there is also the regular いる verb. It’s the same with the “be”, “do” and “have” verbs in English. “Am” in “I am a teacher” plays a different role than the one in “I am eating.”

** 食べる is a transitive verb while 開く is an intransitive verb. Usually transitive verbs will translate to -ing and intransitive verbs won’t. Of course there are exceptions so keep an open mind.

*** When choosing between 来ている���行っている、and いる think about where the speaker is located as well as if you want to stress the movement of the subject.

#japanese#japanese studyblr#japanese language#japanese grammar#日本語#isshonihongo#jlpt n5#jlptn5#jlpt#nihongo#japanese langblr#learn japanese#japanese lesson#japanese study#studying japanese#japaneselessons#learnjapanese#language#languages#language study#language studyblr#language blr#日本語の勉強#にほんご

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grammar: Aとのことだ

Meaning: Presents information/results

---

Construction: A とのことだ 会長さんは今日いらっしゃらないとのことだ(the boss apparently won't be coming in today) AとのS 来(こ)られないとの連絡(れんらく)がありました ((he) left a message saying (he) couldn't come)

---

クラスの種類は初期イメージから増えているとのことでしたが、そのバリエーションはどのように増えていったのでしょう。

クラスの しゅるいは しょきイメージから ふえているとのことでしたが、そのバリエーションは どのように ふえていったのでしょう。

You mentioned that the variety of classes has increased since the initial conception. How did they increase?

---

Notes: Although not technically 敬語 (けいご), this is usually used in formal situations, like in the workplace. The example sentence is from an interview with game developers about the game.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N2 Grammar げ

Meaning: looks like, seems like, appears to be

Note: ~げ becomes a な-adjective

な-adjective → remove な

入学式の朝、息子はとても不安げだったが、学校から帰ってくると、明るい表情だった。

にゅうがくしき の あさ、むすこ は とても ふあんげ だった が、がっこう から かえって くる と、あかるい ひょうじょう だった。

On the morning of the school entrance ceremony, my son looked nervous, but when he returned home from school, he had a cheerful expression.

い-adjective → remove い (irregular: いい/よい → よさ)

あの人は寂しげな目をしている。

あの ひと は さびしげ な め を して いる。

That person has a lonely look in their eyes.

Verb → (stem form) remove ます

ずいぶん、自信ありげだね。

ずいぶん、じしん ありげ だね。

You seem very confident.

Verb → (tai form) remove い

あの子はケーキを食べたげな顔をしている。

あの こ は ケーキ を たべたげ な かお を して いる。

That child has a look on their face like they want to eat the cake.

Noun (very limited)

お客さんに大人げない態度をとってしまった。

おきゃくさん に おとなげ ない たいど を とって しまった。

I took an immature attitude with the customer.

#日本語#japanese#japanese language#japanese langblr#japanese studyblr#langblr#studyblr#japanese grammar#文法#jlpt n2#げ#tokidokitokyo#tdtstudy

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

・Vocabularies of the day:

枝 (えだ) - branch

株 (かぶ) - (tree) stump, stock (financial). This one is fun because it's the same pronunciation as turnip, which is why in animal crossing you buy and sell turnips like stocks.

拾う (ひろう) - to pick up (e.g. off the ground)

・Grammar points studied:

1. である: written Japanese

This lesson was about the だ/である. It's a formal style of writing that has an authoritative tone. It's often used for things like academic papers, legal documents, and sometimes newspaper articles. In this style, verbs at the end of sentences will be in casual form, and where you might hear です in spoken Japanese, you might see である or だ.

2. ~が欲しい・~てほしい

This two-part lesson explains how to say you 'want' something (a noun that can be possesed) with ~が欲しい.

For example: パソコンが欲しい。

With ~てほしい, you can say that you want someone else to do something. For example,

田中さんに事務所に来てほしいです。(I want Tanaka to come to the office)

・Kanji practice (anki's kanji damage deck) Current percent mature: 98.95%

・Current grammar progress (using marumori.io):

N5 - 82/82

N4 - 57/110

N3 - 0/180

N2 - 0/200

N1 - 0/250

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

日本語ブログ ようこぞ!/ Welcome to my Japanese language blog!

日本語で:初めまして! フライともうす。 5年くらい前に日本語が勉強している。日本へ行ったことがないんだけど、ぜひ行きたいやねん。いつか日本で勉強したいも。今自分で習っている。趣味は 漫画を読むとか、犬と散歩に行くとか、カンピンやねん。

漢字が少し難しいんだけど、おもろいと思う。そして関西弁がめっちゃおもろいやねん。

私は スペイン語とか、英語とか、日本語が はなせる。イタリア語少しんだけど。

英語:Hi! My name is Fry. I''ve been studying Japanese for 5 years or so. I've never been to Japan but I definitely want to go. I'd like to study in Japan someday as well. Right now I'm studying on my own. I like to read manga, walk my dogs and go camping.

Although kanji is a bit hard, I think it's pretty cool. Also Kansaiben (Kansai's dialect) is very cool too.

I can speak Spanish, English and Japanese. And just a little bit of Italian.

Like/Reblog if you're another langblr, or studyblr in general or post any of the following, so I can follow you!

haikyuu, jujutsu kaisen, demon slayer, fullmetal alchemist, one piece

anything japan related

nature or plants

art, literature

any variety of academia blog

#langblr#language#language learning#language blog#language lover#japanese#japanese grammar#japanese learning#japanese langblr#japanese language#Japanese language blog#studyblr#study blog#study motivation#studyspo#study aesthetic#language study#dark academia#light academia#chaotic academia#romantic academia#academia aesthetic#classic academia#nature#plants#haikyuu#jujutsu kaisen#fullmetal alchemist#fma#one piece

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

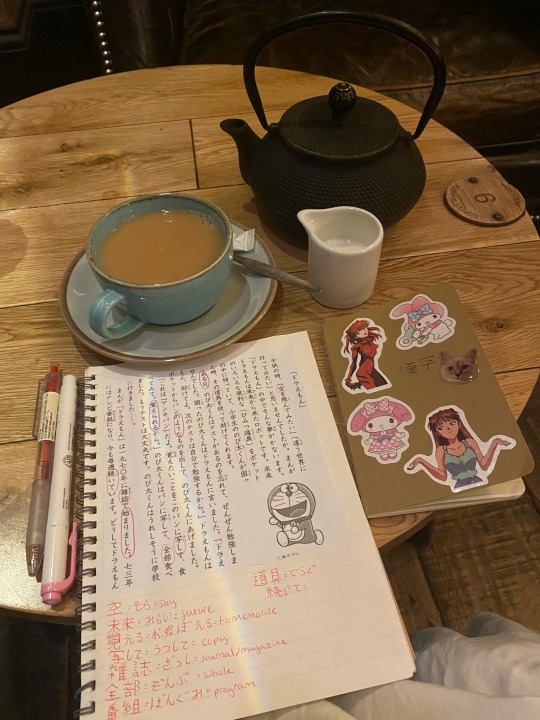

カフェで日本語を勉強している૮꒰ྀི >⸝⸝⸝< ꒱ྀིა これはげんき2の練習だ。皆、日本語が頑張ってね!

#japanese#language learning#studyblr#日本語#japan#langblr#japanese grammar#nihongo#learn japanese#study kanji

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

#japanese#learning japanese#langblog#japan#langblr#anime#japanese vocab#japanese vocabulary#manga#tumblr language#japanese grammar#japanese language#japanese langblr#japan travel#asia#shonen#shonen jump#shojo#hiragana#katakata

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

N5 Grammar Review: Vない

The ない form of the verb is used to mean "not" or "don't". I'm going to make some posts about grammar that uses this form soon, but first I thought it'd be good to go over how exactly we get the ない form.

To make the ない form:

Group 1: change the last 'u' in the dictionary form to 'a', then add ない:

書く(かく)→ 書かない [to write -> not write]

話す(はなす)→ 話さない [to speak -> not speak]

立つ(たつ)→ 立たない [to stand -> not stand]

遊ぶ(あそぶ)→ 遊ばない [to play -> not play]

読む(よむ)→ 読まない [to read -> not read]

知る(しる)→ 知らない [to know -> not know]

Be careful! If the verb ends in う, it becomes わ:

歌う(うたう)→ 歌わない [to sing -> not sing]

買う(かう)→ 買わない [to buy -> not buy]

Group 2: add ない to the stem:

食べる(たべる)→ 食べない [to eat -> not eat]

寝る(ねる)→ 寝ない [to sleep -> not sleep]

見る(みる)→ 見ない [to see -> not see]

教える(おしえる)→ 教えない [to teach -> not teach]

Group 3 of course is a bit different:

する → しない [to do -> not do]

来る(くる)→ こない [to come -> not come]

The ない form is used in casual speech to mean "don't/doesn't do":

Particles in brackets because you can drop them in casual speech.

魚(は)食べない さかな(は)たべない = I don't eat fish

父(は)雑誌(を)読まない ちち(は)ざっし(を)よまない = My dad doesn't read magazines

コーヒー(を)全然飲まない コーヒー(を)ぜんぜん のまない = I don't drink coffee at all

Other than that, the ない form is used a lot as a base for more complex grammar. It's important to get to grips with it early on.

I'm still a beginner myself (I'm only N4 level!) so please let me know if I've made any mistakes!

#japanese langblr#learning japanese#japanese grammar#japanese for beginners#beginner japanese#n5#n5 grammar

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

I will warn you: this post gets pretty deep into the weeds talking about the copula and how it is constructed; if you don’t need to understand something in extreme depth to feel satisfied, this post probably won’t be for you. But if you’re like me and feel things click and become more intuitive when you really deeply understand how it all goes together like a puzzle, hopefully this will help you! If you’re interested in super technical linguistic-y stuff, you’ll probably enjoy this.

#japanese#japanese grammar#japanese lesson#japanese linguistics#japanese parts of speech#japanese study#langblr#language#language learning#learn japanese#linguistics#original post#studying

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

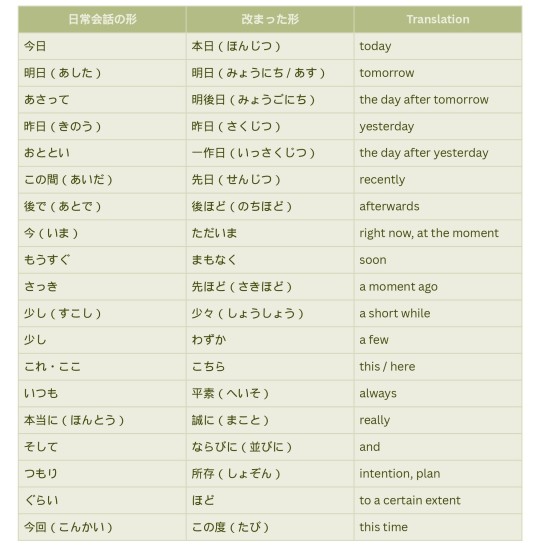

改まった形|Polite Forms

In formal settings like in a business meeting or at a public gathering some words are switched with politer forms. You often hear them when somebody is giving a speech, holding a presentation or on TV. But they appear in written form as well, especially in business context. Basically, everywhere where keigo is used, it is also expected to apply politer forms.

#文法#敬語#japanese langblr#langblr#studyblr#study movitation#learning japanese#japanese vocabulary#japan#japanese#study blog#study notes#language blog#keigo#japanese studyblr#japanese grammar#japanese language#日本語#日本語の勉強#nihongo

380 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why are anime translations so bad?

Disclaimer: I have never done any professional translation, and I don’t watch dubbed/subbed anime very often. But recently I watched a few episodes of subbed Demon Slayer at a friend’s place, and I noticed how bad some of the translations were. It reminded me of my childhood, watching subbed Ghibli movies and thinking “that english sounds weird”. As a kid I thought it was an unavoidable part of translation, but now that I can speak Japanese, I realise that we can do so much better with translations!

This post is my attempt to identify what a “bad” translation is, and hazard some guesses at what mistakes translators make that lead to these bad translations.

Examples are from Ranking of Kings, episodes 10 and 11. Screenshots taken from Crunchyroll.

What do I mean by bad?

Reason 1: They don’t sound like natural English.

If a character in an english cartoon said some of the stuff that characters in anime say in translations, it would sound very unnatural. Anime-translation english is unnatural and awkward sounding.

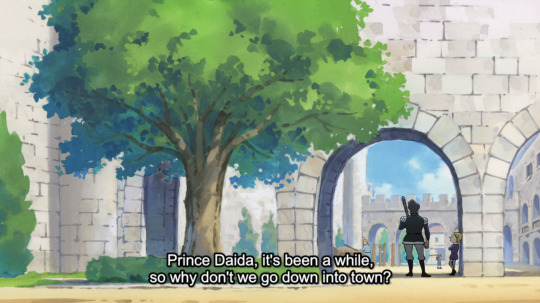

ダイダ様、久しぶりに街に出てみますか? Price Daida, it’s been a while, so why don’t we go down into town?

This example sounds awkward. What’s with the random “so” in the middle of the sentence? No one in English media talks like that. If you just remove the “so” and replace it with a full stop, we get a much more natural sounding sentence.

Price Daida, it’s been a while. Why don’t we go down into town?

Or even something like this:

Price Daida, why don’t we go into town? It’s been a while since you’ve been down there.

Reason 2: They don’t fit the character.

This screenshot shows the character Kage speaking (the black blob). He has a character trait of being kind of immature and almost never using polite Japanese, even to royalty, which is very disrespectful. The original translation makes him sound so formal! Kage is supposed to sound like a 15 year old who tries way too hard to be rough and intimidating. Can you imagine someone like that saying “You may say those things”?

いやいやいや、なんかいい感じなこと言ってるけど、違うからね! No, no, no! You may say those feel-good things, but reality is different!

It doesn’t preserve his characterisation at all. Way too formal and not juvenile enough! A better translation would be:

No, no, no! Nice motivational speech, but they’re just words!

The devil’s advocate & descriptivism

Now, I’ll preface this by saying I am a hardcore descriptivist. I’m not saying that these translations are wrong, or that the resulting English is incorrect English. What I’m saying is that they do not achieve the goals of a good translation, those goals being preserving what is being said and how it’s being said.

It could be argued that by now, anime translations have become a new dialect of English. Anime fans have come to expect the awkward-sounding phrasing, and instead might see natural English as unexpected. This is a fine rebuttal of my first point (it sounds awkward) but not of my second point (speech-pattern-based characterisation is often lost). Even then, anime translations are not exclusively for established anime fans. First time viewers may be put off by the unnatural language choices and strange turns of phrase. “Anime is cringe” they might say, and they wouldn’t be wrong. A good translation should be understandable to the entire target audience, and first time or casual viewers certainly make up a large portion of that target audience.

Why do the translations end up so bad?

They err on the side of direct translation over meaning-based translation

Often, it seems like the main nouns and verbs in the sentence get translated verbatim, and the rest of the translation is forced to bend around those. In addition, they do not consider how a similar sentiment might be phrased in english. Even if it’s a japanese way of saying something, they preserve the individual words instead of changing the whole sentence. Let’s look at the Kage example from before:

いやいやいや、なんかいい感じなこと言ってるけど、違うからね! No, no, no! You may say those feel-good things, but reality is different!

I’ve coloured the text so you can see which pieces got translated separately. In this example, basically every word is being translated separately. Now let’s look at my example:

いやいやいや、なんかいい感じなこと言ってるけど、違うからね! No, no, no! Nice motivational speech, but they’re just words!

I’m translating the entire middle verb phrase as one atomic piece of meaning. It’s not individually important that, for example, the specific word 言ってる was used, so it’s not important that I translate it directly to the word “say”. What is important is that Kage is saying that Despa is saying some nice stuff, but it doesn’t change the facts. I have a feeling that the more you can group words together and translate them as a whole phrase, the more natural the translation ends up sounding (and the more characterisation you can preserve).

They use weird words, due to dictionary translation

Let’s look at another example:

兄上は弱者だと、どこか甘えていないか? Aren’t they sort of spoiling Brother, just because he’s a weakling?

In this example, the word 弱者 is translated as “weakling”. “Weakling” is a pretty rare word to hear outside of anime. That’s probably the best direct translation if we’re looking at the word 弱者 out of context. However, words always appear in context. Both times the word 弱者 is used to refer to a person in this episode, it’s used to refer to disabled people (Bojji, who is deaf, and a citizen, who is both blind and deaf). The citizen is actually not physically weak, in fact he looks pretty chunky and strong, so 弱者 is not being used to refer to his physical strength, only his disability. The English word “weakling” strongly suggests physical weakness, so I don’t feel like it’s appropriate here. Instead, I feel like a more appropriate translation would be:

Do you think Brother gets special treatment, just because he’s so pathetic?

Daida is immature and heartless at this point in his character. He has contempt for both Bojji and the citizen, and sees them as weak, but he also feels pity for them. I think the word “pathetic” sums up his emotions for them much better than the word “weakling”, as well as not coming loaded with the incorrect “physical weakness” connotation.

As a side note, you may have noticed I translated the first part of the sentence differently too. That’s another example of how (in my opinion) grouping words together to translate a phrase as a whole results in a much more natural phrasing.

They try to preserve the original grammar

An important skill to have when translating is knowing which aspects of the phrase are important to preserve in translation, and which parts are not important. Word order and grammar are almost never important enough to preserve.

ダイダ様こそ、選ばれた人間。 Prince Daida, you are one who is chosen.

In this example, the past tense verb 「選ばれた/chosen」modifying the noun 「人間/person」 seems to have been determined to be important to preserve by the translator, which leads to the awkward phrasing “one who is chosen”. In reality, the minutia of the original grammar is not important to preserve - we can translate 選ばれた人間 as a set phrase rather than translating the words individually:

Prince Daida, you are one of the chosen few.

Again, we can see that the translation is improved by grouping words together and translating the phrase as a piece of atomic meaning!

Anime translation is a naturally restrictive medium

For dubs, the characters’ mouth movements need to match up. This really narrows down the possibilities of translation options. It means that sub-optimal word choices may be used, and the rhythm of speech may be forced into an odd speed in places.

For subs, although the syllables and mouth movements don’t need to match up as perfectly as they do in dubs, the subtitles still end up needing to be applied over the same moments of speech. However, often, if the given situation in the anime was to be completely reframed in English, maybe no one would have said anything at that moment. There are times when someone would say something in Japanese that you would expect someone to not say anything in english.

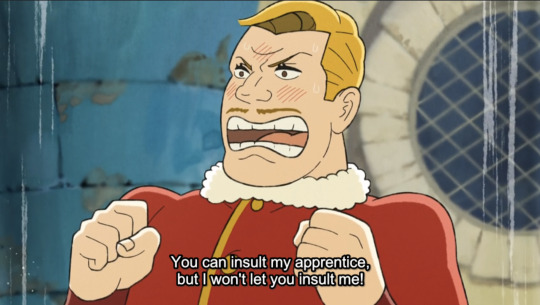

デスパー:弟子の悪口は許しますけど、私の悪口は許しませんよ!! カゲ:逆でしょ!!!! Despa: You can insult my apprentice, but I won’t let you insult me! Kage: You’ve got it backwards!

In Japanese comedy, the role of ツッコミ (best translation is “the straight man”) is ubiquitous and plays the part of a laugh track - telling audiences when to laugh. In this case, Kage is playing the part of ツッコミ by pointing out that what Despa has said is the opposite of what you’d expect him to say. In this example, I feel like if this was an English cartoon, Kage wouldn’t have said anything. English speaking comedies generally expect/trust audiences to get the jokes without them being explicitly pointed out. I feel like this shows how attempting to fit subtitles to every spoken phrase can lead to slightly unnatural turns of phrase, since the translator is attempting to fit some speech into a place where there wouldn’t have been any in the first place. In my opinion, the best “translation” for the above would have been to cut the 1 second clip where Kage butts in with his line altogether.

———

Again, I should reiterate that I’m not a translator. I’m very keen to hear counter-arguments if you disagree with what I’ve said! Translations have got me really interested recently and I’m hungry for more opinions.

#langblr#japanese language#japanese#japanese grammar#learning japanese#linguistics#translation#language acquisition#language learning#language#anime#ranking of kings#official blog post

368 notes

·

View notes

Text

JLPT N5 - している [Part 1]

している is a grammar point that is very very important in Japanese. The “して” part represents a verb in the て form. The “いる” part is the verb いる, which will change to different forms (for example います、る or ます).

している actually appears in several levels of the JLPTs - from N5 all the way to N2! As for the N5 level, there are 2 main ways that you will see it used. In this post let’s look at one of them!

First, here is your vocabulary.

【Repeated Actions】

First let’s look at how している is used with repeated actions. These actions are mostly physical.

= I climb Mt. Fuji every year.

Notice the two highlighted words, 毎年 and 登って. If 毎年 weren’t there you would almost always translate 登っています as “am climbing”. However, because 毎年 expresses repetition, it forces us to translate 登っています as “climb”.

= Traffic accidents happen on this street often.

起きる is a verb that can mean “to wake up” or “to occur”. If sentence #2 didn’t have the word よく it would be understandable to translate 起きています as “are occurring”. However because of the よくwe understand that there is repetition and so we go with the “occur” translation instead.

= Well you see, Dad has been going to China for work once a month since last year.

This time the word / phrase that expresses repetition is 毎月1回 meaning “once a month”. This tells us that 行ってる is “goes” instead of “is going”. Also, the い in the helping verb いる can be dropped, making 行ってる a more casual way of saying 行っている. It also works for います so that 行ってます is more casual than saying 行っています。

Finally, take a look at the nuance section. This んです is actually a different JLPT grammar point. The gist is that it’s used when you want to answer a question with extra details that you think the listener/reader wants to know. The ん is a shortened version of the particle の.

【Occupation or Social Position】

している is also used to talk about someone’s occupation or social position.

= Taiki teaches Japanese at a Thai university.

There is no period of repetition stated outright, but we understand that teaching is a job that you do over and over. Thus, you should use 教えています instead of 教えます。

= Aya is a trading company manager.

In this case, the しています simply means “is” or “has the position of”.

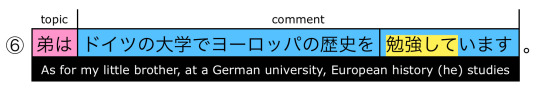

= My little brother studies European history at a German university.

This last example is a good one to remember. Most times, if you say 勉強してい���す it will mean “currently studying”. However when it comes to being a student, the translation shifts to “studies (for an extended period of time)”. Actions that can be interpreted either way (like studying) will sometimes have time words / phrases like 今 (now) or 2、3時間 (for a few hours). That tells you that it is an action in progress. Other than those kinds of phrases, usually the meaning will be repetitive.

【Conclusion】

So there you have it! The first している is associated with repeated actions, occupations, or positions in society or work. It’s fairly easy to figure out if the sentence is talking about an occupation or a position. For repeated actions, the key is to look for words / phrases that express repetition and remember that they cause you to use the している version of your verb. With that, you should be fine!

Rice & Peace,

– AL

👋🏾

#japanese#japanese studyblr#japanese grammar#japanese language#日本語#isshonihongo#jlpt#jlpt n5#一緒日本語#している

54 notes

·

View notes