#Japanese Battleship Shinano

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

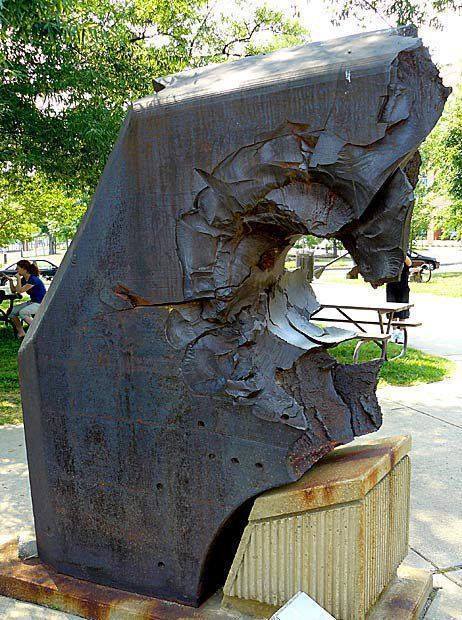

The broken armor plate intended for the third Yamato Class Battleship, the Shinano (信濃, Shinano Province) on display at the U.S. Navy Memorial Museum at the Washington Navy Yard, Washington, DC. This plate would have gone on the turret face and is 25" thick!

It was captured by the American Forces after war and sent the U.S. Naval Proving Ground, Dahlgren, Virginia for testing. This particular plate was tested on October 16, 1946 and was penetrated by a US Navy 2700-lb 16" Mark 8 Mod 6 AP with inert filler.

"Complete penetration and plate snapped in two through impact between side edge and upper end of curved gun port hollow. Hole more-or-less cylindrical, with little difference between front and back of plate. Numerous small cracks also put in plate around impact. No damage to projectile indicated, though projectile had considerable remaining velocity and ended up in the Potomac River, never being recovered. Considerable amount of lamination noted in hole (layering effect parallel to face, much like pages in a book glued together)."

Information from NavWeaps.com

If you wish to read more about the tests, click here, link and link. There's too much information for me to condense into a post.

U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command: NH 82599, NH 82597, NH 82596, NH 82598

#Japanese Battleship Shinano#Shinano#Yamato Class#Japanese Battleship#Battleship#Warship#Ship#Washington Navy Yard#Washington#DC#east coast#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#United States Navy#U.S. Navy#US Navy#USN#Navy#October#1946#postwar#post war#my post

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

#revell 1/1200 #imperialjapanesenavy #battleship #yamato #musashi #aircraftcarrier #shinano #worldwarii #worldwar2 #ww2 #wwii #revellmodels #modelships

instagram

#original content#revell#imperial japanese navy#battleship#yamato#musashi#aircraft carrier#shinano#world war 2#world war ii#ww2#wwii#revell models#model ships#Instagram

0 notes

Note

Sorry, maybe because i just came from kancolle fanfic reading, but why are the Yamato sisters useless in the Azur lane world? Arent the Yamatos among the most heavily armed and reinforced units in the Japanese side? Or arethe jokes about hotel yamato on point for the ship girls?

Yeah, Kancolle will definitely skew your perspective even before the fanfic, lol.

The Yamato-class were on paper the greatest battleships ever, with the biggest guns and heaviest armor.

That was debatable already, but really didn't matter when the reality for most of the war was that battleships were nigh obsolete for ship to ship combat and completely ineffective to the Japanese war effort. The Yamato-class in particular were too expensive to deploy long-range due to dwindling supplies. For the most part they were kept close to the mainland out of submarine range.

Then things got worse.

Shinano was set to be converted into an aircraft carrier after Midway, but was too far along to become a full fleet carrier, so they settled on something close to a support carrier. She was sent out in desperation for a full fitting too early, and was sank en route by Archerfish.

Musashi was caught out on patrol by Intrepid and sank rather quickly, and Yamato - who was basically just a glorified propaganda piece - was ordered to beach herself on Okinawa and be a stationary artillery battery until she was destroyed completely, but didn't even make it that far before she was sank by aircraft.

All three of them utterly and completely useless paper tigers.

For AL specifically, they're shaping up to be the same in lore while being pretty good in gameplay.

As far as lore goes they're strong alright but Shinano's power is her dreams and she spends hardly any time awake and aware of where and when she is.

Musashi is majestic and imposing but indolent and pretty much latches onto Akagi because it gives her someone to support without her having to make the decisions. Her use begins and ends as Akagi's rubber stamp convincing people to follow her. When something comes to her specifically and threatens someone she cares for, she can be plenty menacing - but that doesn't really matter, especially not when Akagi's been granted god-tier power and has a plan already.

We know very little of Yamato, but what we do know is that she's as imposing as Musashi but "calming" to be around, and has been completely and utterly absent from the story despite all of the utterly insane bad shit we've seen. Not a stretch to assume she'll be similar to Musashi.

Even if you want to look at their lore strength and even if you're going to compare them solely to battleships in gameplay, the Black Dragon is around.

Technically Shinano wins as the most useful Yamato because her dreams verify Akagi's mindset and she's also the strongest carrier in the game when Big E doesn't proc her skill.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka

The Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka (櫻花, Ōka, "cherry blossom") was a purpose-built, rocket-powered human-guided kamikaze attack aircraft employed by Japan against Allied ships towards the end of the Pacific War during World War II.

The MXY-7 Navy Suicide Attacker Ohka was a manned flying bomb that was usually carried underneath a Mitsubishi G4M2e Model 24J "Betty" bomber to within range of its target. On release, the pilot would first glide towards the target and when close enough he would fire the Ohka's three solid-fuel rockets, one at a time or in unison, and fly the missile towards the ship that he intended to destroy. The design was conceived by Ensign Mitsuo Ohta of the 405th Kōkūtai, aided by students of the Aeronautical Research Institute at the University of Tokyo. Ohta submitted his plans to the Yokosuka research facility. The Imperial Japanese Navy decided the idea had merit and Yokosuka engineers of the Yokosuka Naval Air Technical Arsenal created formal blueprints for what was to be the MXY7. The only variant which saw service was the Model 11, and it was powered by three Type 4 Mark 1 Model 20 rockets. 155 Ohka Model 11s were built at Yokosuka, and another 600 were built at the Kasumigaura Naval Air Arsenal.

The final approach was difficult for a defender to stop because the aircraft gained high speed (650 km/h (400 mph) in level flight and 930 km/h (580 mph) or even 1,000 km/h (620 mph) in a dive. Later versions were designed to be launched from coastal air bases and caves, and even from submarines equipped with aircraft catapults, although none were actually used in this way. The Allen M. Sumner-class destroyer USS Mannert L. Abele was the first Allied ship to be sunk by Ohka aircraft, near Okinawa on April 12th, 1945. Over the course of the war, Ohkas sank or damaged three ships beyond repair, significantly damaged three more ships, with a total of seven U.S. ships damaged or sunk by Ohkas. The only operational Ohka was the Model 11. Essentially a 1,200-kilogram (2,600 lb) bomb with wooden wings, powered by three Type 4 Model 1 Mark 20 solid-fuel rocket motors, the Model 11 achieved great speed, but with limited range. This was problematic, as it required the slow, heavily laden mother aircraft to approach within 37 km (20 nmi; 23 mi) of the target, making them very vulnerable to defending fighters. There was one experimental variant of the Model 11, the Model 21, which had thin steel wings manufactured by Nakajima. It had the engine of the Model 11 and the airframe of the Model 22.

The Ohka K-1 was an unpowered trainer version with water ballast instead of warhead and engines, that was used to provide pilots with handling experience. Unlike the combat aircraft, it was also fitted with flaps and a landing skid. The water ballast was dumped before landing but it remained a challenging aircraft to fly, with a landing speed of 130 mph (210 km/h). Forty-five were built by Dai-Ichi Kaigun Koku Gijitsusho. The Model 22 was designed to overcome the short standoff distance problem by using a Campini-type motorjet engine, the Ishikawajima Tsu-11. This engine was successfully tested, and 50 Model 22 Ohkas were built at Yokosuka to accept this engine. The Model 22 was to be launched by the more agile Yokosuka P1Y3 Ginga "Frances" bomber, necessitating a shorter wing span and much smaller 600-kilogram (1,300 lb) warhead. The first flight of a Model 22 Ohka took place in June 1945; none appear to have been used operationally, and only approximately 20 of the experimental Tsu-11 engines are known to have been produced. The Model 33 was a larger version of the Model 22 powered by an Ishikawajima Ne-20 turbojet with an 800-kilogram (1,800 lb) warhead. The mothership was to be the Nakajima G8N Renzan. The Model 33 was cancelled due to the likelihood that the Renzan would not be available.

The Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka was used mostly against U.S. ships invading Okinawa, and if launched from its mothership, could be effective because of its high speed in the dive. In the first two attempts to transport the Ohkas to Leyte Gulf using aircraft carriers, the carriers Shinano and Unryu were sunk by the U.S. submarines Archerfish and Redfish. Attacks intensified in April 1945. On April 1st, 1945, six "Bettys" attacked the U.S. fleet off Okinawa. At least one made a successful attack; its Ohka was thought to have hit one of the 406 mm (16 in) turrets on the battleship West Virginia, causing moderate damage. Postwar analysis indicated that no hits were recorded and that a near-miss took place. The transports Alpine, Achernar, and Tyrrell were also hit by kamikaze aircraft, but it is unclear whether any of these were Ohkas from the other "Bettys". None of the "Bettys" returned. The U.S. military quickly realized the danger and concentrated on extending their "defensive rings" outward to intercept the "Betty"/Ohka combination aircraft before the suicide mission could be launched.

On April 12th, 1945, nine "Bettys" attacked the U.S. fleet off Okinawa. The destroyer Mannert L. Abele was hit, broke in two, and sank, witnessed by LSMR-189 CO James M. Stewart. Jeffers destroyed an Ohka with AA fire 45 m (50 yd) from the ship, but the resulting explosion was still powerful enough to cause extensive damage, forcing Jeffers to withdraw. The destroyer Stanly was attacked by two Ohkas. One struck above the waterline just behind the ship's bow, its charge passing completely through the hull and splashing into the sea, where it detonated underwater, causing little damage to the ship. On April 14th, 1945, seven "Bettys" attacked the U.S. fleet off Okinawa. None returned. None of the Ohkas appeared to have been launched. Two days later, six "Bettys" attacked the U.S. fleet off Okinawa. Two returned, but no Ohkas had hit their targets. Later, on April 28th, 1945, four "Bettys" attacked the U.S. fleet off Okinawa at night. One returned. No hits were recorded. May 1945 saw another series of attacks. On 4 May 1945, seven "Bettys" attacked the U.S. fleet off Okinawa. One Ohka hit the bridge of a destroyer, Shea, causing extensive damage and casualties. Gayety was also damaged by an Ohka's near miss. One "Betty" returned. On May 11th, 1945, four "Bettys" attacked the U.S. fleet off Okinawa. The destroyer Hugh W. Hadley was hit and suffered extensive damage and flooding. The vessel was judged beyond repair. On May 25th, 1945, 11 "Bettys" attacked the fleet off Okinawa. Bad weather forced most of the aircraft to turn back, and none of the others hit targets. On June 22nd, 1945, six "Bettys" attacked the fleet. Two returned, but no hits were recorded. Postwar analysis concluded that the Ohka's impact was negligible, since no U.S. Navy capital ships had been hit during the attacks because of the effective defensive tactics that were employed.

In total, of the 300 Ohka available for the Okinawa campaign, 74 actually undertook operations, of which 56 were either destroyed with their parent aircraft or in making attacks. The Allied nickname for the aircraft was "Baka", a Japanese word meaning "foolish" or "idiotic". Several surviving examples of the Ohka still exist. A Model 11 on static display at Iruma Air Force Base in Iruma, Saitama. Model 11 on static display at the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton, Somerset. Model 11 on static display at the Imperial War Museum in London. Model 11 on static display at the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Triangle, Virginia. Model 11 on static display at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California. K-1 on static display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. K-1 on static display at the National Museum of the U.S. Navy in Washington, D.C.

#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#military history#wwii#history#aviation#kamikaze#imperial japan#japanese history#japanese#cherry blossom#pacific campaign#okinawa

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Yamato’s Vacuum Cleaning Robot: Musashi

This will be an analysis on why Yamato’s cleaning robot is called “Musashi.”

(under break)

“Musashi” is a historically significant name in Japan. Most Japanese people are familiar with this name, normally referring to one of the following:

Miyamoto Musashi - famous samurai and poet/writer

Battleship Musashi - a famous WWII battleship, sister ship to the Battleship Yamato.

Musashi Province - former province in the area of present-day Tokyo. There is still a city called “Musashino” inside Tokyo.

The name is popular as a place name as well as a name for numerous characters in various forms of media.

Battleship Musashi

I will begin with the name of the battleship, as it is the first association I naturally made with the cleaning robot. Musashi, the vacuum, traverses a room, much like a battleship at sea.

The Battleship Musashi, named after the aforementioned Musashi Province, is described as a Yamato-class battleship, as it is the sister ship to the Battleship Yamato (same kanji spelling as the character). These ships were specially designed to fend off air attacks. Yamato and Musashi are the only two Yamato-class battleships produced (although a third, Shinano, was converted to an aircraft carrier). It would makes sense that Yamato would have a little Musashi sailing around his room.

Both battleships gained cultural significance in the aftermath of WWII, as they represent Japan’s naval strength and dedication to engineering. Battleship Yamato, likewise, was named after the Yamato Province (present-day Nara Prefecture), which was the governmental center of Japan during the Yamato Period (250–710 CE). The name “Yamato” is also assigned as a historical name of Japan, due to this period.

Battleship Yamato furthermore is a significant reference for anime fans, because in the anime Space Battleship Yamato (1974), the historical battleship is reformed into a space ship. Many otaku and those working in anime-related fields will know about the Space Battleship Yamato, due to its significance in paving the way for sci-fi anime like Gundam, Evangelion, and Macross, as well as being successfully dubbed and released in the US in the 70′s.

Miyamoto Musashi

I first came across this reference, as an acquaintance of mine is a bit of a samurai otaku. In a group, we were talking about Skytree, and the question, “How tall is Skytree?” came up. He answered immediately, “634 meters.”

The reason being that there is a restaurant on the viewing deck of Skytree called Musashi, and due to the pronunciation, it became an easy mnemonic device to remember the height of Skytree.

Mu - 6

Sa - 3

Shi - 4

Upon thinking about this, I am immediately reminded of this scene, because it is the duty of an IDOLiSH7 fan to be sensitive to numbers. (It doesn’t help that Skytree showed up in a Vibrato episode and reminded me of this fact again.)

Of course, my acquaintance remembered both the restaurant name and the mnemonic because it shares a name with a famous samurai, Musashi, so here are some fun connections between Nikaido Yamato and the samurai Musashi.

Musashi was known for creating a two-sword technique called “Niten Ichi-ryuu ( 二天一流 ),” which is “two heavens as one” technique, two as in Nikaido, #2. (Yes, “heaven” is the same kanji in Tenn’s name.)

Musashi had two adopted sons who were also samurai, first Mikinosuke (三木之助), and then a second adopted son named Iori (伊織). The kanji for 3 is the same in both Mitsuki’s and Mikinosuke’s names. The character for “ori” is the same in both the son Iori and the i7 member. Take that as you will.

The next few connections are spoilers. Please only read beyond this point if you don’t mind spoilers for the game story Part 3, and the Re:member novels/manga for Yuki’s chapters.

Musashi’s father, Munisai, was also a famous samurai at the time. Although this is a debated topic, it is believed that Musashi’s mother was not the woman who was married to his father during most of Musashi’s life. This somewhat parallels Yamato as an illegitimate son of Chiba Shizuo. And then, Yamato ended up following in his father’s footsteps and became an actor.

Musashi lived with his uncle from the age of 7, so he lived most of his childhood and adolescence away from his father, until later returning to him to learn his sword technique at the age of 23, the same age at which Yamato would be attempting to reconnect with his father in Part 3. (I wonder where this will lead in Part 4...)

Chiba Shizuo is famous for his many samurai roles, and is shown acting as a swordsman in Re:member, in which Chiba is thinking about Yamato a lot and shares his family history with Yuki. It would be a small treat if it ends up he portrays either Musashi or Munisai at any point in his career.

I’m not sure how meta you want to take this, but if “Musashi” carries the same historical, anime-relevant, and samurai-historical weight in both real life and IDOLiSH7′s world, then what does that mean for Yamato, who named his own vacuum cleaner this? 💚

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lycoris Recoil

Azur Lane is back at it with that Event bullsh*t, man! This time, it’s a Sakura Empire focus and I'm only borderline interested. Like, the Japanese are my secondary Fleet. Obviously, KMS main, this blog is riddle with my love for the Krauts, but i do enjoy some of the ships from the Land of the Rising Sun. I had no real plans to make a serious run at this particular banner, roll whatever ships i get, but then i actually looked into it. There is another Ultra Rare available. That means, of the eight available URs, Sakura accounts for damn near half. I missed out on Shimakaze because, at the time, i just didn’t want to spend the Wisdom Cubes but i did get Shinano. Considering Musashi appears to be kin to the Silver Fox, i kind of changed my mind about the whole event. Plush, i mean, have you seen that art? Possessed Back Fox Battleship? Come on? How can i NOT make a run at this banner?

I have to say, I'm glad i did. It cost me eighty-two rolls but i finally popped Musashi. It was slightly more costly than i would have liked but well within the margin of error. Plus, while chasing that Ultra Rare dragon, i effectively unlocked the rest of the Banner ships. That’s right, i was able to get Haguro, Suzuki, Sakawa, and Wakatsuki; All before i popped my first Musashi. I say first because i ended rolling, like, two more on a “Let’s see what happens” roll. That last ten-roll attempt netted me a second Musashi, three Haguro, Sakawa, and, interestingly enough, f*cking Pola. That last one was a genuine surprise because i didn’t think she was in the general pool. I have a surprisingly robust Itai dock so adding another ship to it is always a boon. If i had to say, I'd probably call them my third or fourth favorite Fleet. It’s a coin toss between them and the Ruskies. No Zar,a though... All in all, I'm pretty content with this situation. I have all of the available Event ships, outside of Miyuki but that’s just a matter of time. I mean, she’s a Points reward and you know i gotta grind out for them Priority Five Blueprints anyway, so....

More than that, I'm kind of hyped i was able to enhance my Musashi so far on day one, with no grind. I got her to level 117 because of all the goddamn EXP packs i own. It took everything i had on hand, over six hundred of the blue ones and eight of the purple, but i think it’s money well spent because i didn’t have the time to actually play the Event while at work. Kind of bummed i couldn’t get her to 120 but I'm close. What i did get to achieve, was fully limit breaking her, thanks to my stockpile of UR Bulins. It also helps that i have around twenty-eight thousand of those Specialty Cores. They only cost four thousand in the Prototype Shop so purchasing the single one i needed was nothing. The others all came from the Seasonal Cruise rewards. Invest in that Fair Winds pass, man. It’s totally worth the ten bucks. I was able to immediately rank-up her Violent Lightning Storm to ten (Thank you, Classroom Speed-up) and am currently working on her Tempestuous Blade skill. That last skill, Musashi’s Guardianship, is going to be a grind, though. I get to do that straight and I'm kind of dreading it.

Ultimately, i went at this banner halfheartedly and the gacha gods decided to reward me. I started the day with 284 Wisdom Cubes and ended it with 100. Sure, i probably spent more than i would have liked, but considering i have several weeks to make up what i lost, and i didn’t have to actually buy more with my real loot, i am okay with the outcome. All of the Event ships. Musashi, twice. Another expansion of my Sakura dock. And a Pola for good measure. Now all that’s left is to actually beat the maps, which i a few weeks to do. Won’t even have to eat up more Oil than i am comfortable with, in order to beat them. I mean, i have twenty thousand of that sh*t so i think i can make a pretty solid dent into those maps before i feel like i need to pause. I mean, i only need ten thousand points for Miyuki. That’s a cake walk. My only concern is that i might have overreached in terms of my Inverted Orthant rerun cache. Listen, Musashi is dope but i have a might need for them Orthant boats, man!

0 notes

Text

Lycoris Recoil

Azur Lane is back at it with that Event bullsh*t, man! This time, it’s a Sakura Empire focus and I'm only borderline interested. Like, the Japanese are my secondary Fleet. Obviously, KMS main, this blog is riddle with my love for the Krauts, but i do enjoy some of the ships from the Land of the Rising Sun. I had no real plans to make a serious run at this particular banner, roll whatever ships i get, but then i actually looked into it. There is another Ultra Rare available. That means, of the eight available URs, Sakura accounts for damn near half. I missed out on Shimakaze because, at the time, i just didn’t want to spend the Wisdom Cubes but i did get Shinano. Considering Musashi appears to be kin to the Silver Fox, i kind of changed my mind about the whole event. Plush, i mean, have you seen that art? Possessed Back Fox Battleship? Come on? How can i NOT make a run at this banner?

I have to say, I'm glad i did. It cost me eighty-two rolls but i finally popped Musashi. It was slightly more costly than i would have liked but well within the margin of error. Plus, while chasing that Ultra Rare dragon, i effectively unlocked the rest of the Banner ships. That’s right, i was able to get Haguro, Suzuki, Sakawa, and Wakatsuki; All before i popped my first Musashi. I say first because i ended rolling, like, two more on a “Let’s see what happens” roll. That last ten-roll attempt netted me a second Musashi, three Haguro, Sakawa, and, interestingly enough, f*cking Pola. That last one was a genuine surprise because i didn’t think she was in the general pool. I have a surprisingly robust Itai dock so adding another ship to it is always a boon. If i had to say, I'd probably call them my third or fourth favorite Fleet. It’s a coin toss between them and the Ruskies. No Zar,a though... All in all, I'm pretty content with this situation. I have all of the available Event ships, outside of Miyuki but that’s just a matter of time. I mean, she’s a Points reward and you know i gotta grind out for them Priority Five Blueprints anyway, so....

More than that, I'm kind of hyped i was able to enhance my Musashi so far on day one, with no grind. I got her to level 117 because of all the goddamn EXP packs i own. It took everything i had on hand, over six hundred of the blue ones and eight of the purple, but i think it’s money well spent because i didn’t have the time to actually play the Event while at work. Kind of bummed i couldn’t get her to 120 but I'm close. What i did get to achieve, was fully limit breaking her, thanks to my stockpile of UR Bulins. It also helps that i have around twenty-eight thousand of those Specialty Cores. They only cost four thousand in the Prototype Shop so purchasing the single one i needed was nothing. The others all came from the Seasonal Cruise rewards. Invest in that Fair Winds pass, man. It’s totally worth the ten bucks. I was able to immediately rank-up her Violent Lightning Storm to ten (Thank you, Classroom Speed-up) and am currently working on her Tempestuous Blade skill. That last skill, Musashi’s Guardianship, is going to be a grind, though. I get to do that straight and I'm kind of dreading it.

Ultimately, i went at this banner halfheartedly and the gacha gods decided to reward me. I started the day with 284 Wisdom Cubes and ended it with 100. Sure, i probably spent more than i would have liked, but considering i have several weeks to make up what i lost, and i didn’t have to actually buy more with my real loot, i am okay with the outcome. All of the Event ships. Musashi, twice. Another expansion of my Sakura dock. And a Pola for good measure. Now all that’s left is to actually beat the maps, which i a few weeks to do. Won’t even have to eat up more Oil than i am comfortable with, in order to beat them. I mean, i have twenty thousand of that sh*t so i think i can make a pretty solid dent into those maps before i feel like i need to pause. I mean, i only need ten thousand points for Miyuki. That’s a cake walk. My only concern is that i might have overreached in terms of my Inverted Orthant rerun cache. Listen, Musashi is dope but i have a might need for them Orthant boats, man!

0 notes

Note

How many aircraft carriers were originally intended to be battleships or something else?

Royal Navy

HMS Argus (I49) was originally an ocean liner named Conte Rosso.

The Courageous-class (HMS Courageous, Furious and Glorious) were originally laid down as battlecruisers.

HMS Eagle was originally named Almirante Cochrane, until the Royal Navy purchased the half-complete super-dreadnaught from Chile in 1918.

There were also quite a lot of escort carriers converted from merchant vessels, oilers, etc.

US Navy

USS Langley (CV-1) was converted from the collier USS Jupiter (AC-3).

USS Lexington (CV-2) and Saratoga (CV-3) were originally laid down as battlecruisers. Redesigned as aircraft carriers in accordance with the Washington Naval Treaty.

The nine Independence-class light carriers were originally laid down as Cleveland-class light cruisers.

Again there were a lot of converted escort carriers.

Imperial Japanese Navy

Akagi and Kaga were converted from a battlecruiser and a battleship respectively, in accordance with the Washington Naval Treaty.

The two Chitose-class light carriers were converted from seaplane tenders.

Ryuho was originally a submarine tender named Taigei.

The two Zuiho-class light carriers were originally submarine tenders, designed to be converted into light carriers or oilers when needed.

Junyo was originally laid down as the passenger liner Kashiwara Maru, similarly Hiyo was originally passenger liner Izumo Maru. The Japanese Navy subsidized luxury liner construction projects (up to 60% of the building cost), and in exchange the ships were designed to be able to be converted into carriers should the need arise.

Ibuki, though not completed before the end of the war, was converted from a heavy cruiser.

Escort carrier Shinyo was converted from the German ocean liner SS Scharnhorst.

Shinano, the biggest vessel on this list, was converted from a Yamato-class battleship, but was sunk by USS Archerfish (SS-311) before she was commissioned.

Again, a number of escort carriers were converted from passenger or cargo vessels.

I’m not entirely sure this list is complete but it shouldn’t be too far off, I hope.

89 notes

·

View notes

Link

Yamato Class The Yamato-class battleships were two battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, Yamato and Musashi, laid down leading up to World War II and completed as designed. A third hull laid down in 1940 was converted to an aircraft carrier, Shinano, during construction. Credit to : Megaproje

0 notes

Photo

The Yamato-class battleships (大和型戦艦 Yamato-gata senkan) were battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) constructed and operated during World War II. Displacing 72,000 long tons (73,000 t) at full load, the vessels were the heaviest battleships ever constructed. The class carried the largest naval artillery ever fitted to a warship, nine 460-millimetre (18.1 in) naval guns, each capable of firing 1,460 kg (3,220 lb) shells over 42 km (26 mi). Two battleships of the class (Yamato and Musashi) were completed, while a third (Shinano) was converted to an aircraft carrier during construction. (source: Wikipedia)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano conducts sea trials in Tokyo Bay, sometime in mid 1944. Built on the hull of the third Yamato class battleship, she was the heaviest and most well protected aircraft carrier of the Second World War. She was not without her design flaws, however, which sealed her fate on November 29th, 1944. While sailing out of Tokyo Bay she was stalked by the American submarine USS Archerfish (SS-311), which hit her with four torpedoes. Though it was believed she could survive, leaky bulkheads and poor damage control caused Shinano to sink several hours later. She is the largest warship ever sunk by submarine to this day.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sketch of the Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carrier Shinano (信濃). Laid down in May 1940 as the third Yamato class battleship, her partially complete hull was ordered to be converted to an aircraft carrier following Japan's disastrous loss of four of its original six fleet carriers at the Battle of Midway in mid-1942.

Artwork by S. Fukui.

NARA: 221950332

#Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carrier Shinano#Shinano#信濃#Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carrier#Japanese Aircraft Carrier#Aircraft Carrier#Yamato Class#Warship#Ship#Imperial Japanese Navy#IJN#Japanese Aircraft Carrier Shinano#Artwork#undated#my post

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Japan's Super Aircraft Carrier Was the Biggest Warship Ever Sunk by a Submarine

Still, the Shinano's crew wasn't unduly worried. The ship was designed to absorb such damage, and in fact continued to try to sail at maximum speed. But water flooded through the holes in the ship's side, flowing into unsecured spaces and through what should have been watertight doors. Pumps and generators failed. Soon the carrier acquired a list to starboard that only got worse.If weight alone could determine victory, then the Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft carrier Shinano might still be afloat.At 69,000 tons when launched in 1944, the Shinano would have remained the world's largest aircraft until the 1960s. But that was not to be. Instead the Shinano earned a distinction of a different kind: the title of largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.(This first appeared several years ago.)And the submarine that accomplished—the 1,500-ton USS Archerfish—was one-forty-sixth the size of its victim.The story begins in May 1940, when the Shinano was laid down as the third of Japan's legendary Yamato-class battleships. These giants were the largest battleships in history, built as part of Japan's desperate attempt to counter U.S. naval quantity with a few—hopefully—qualitatively superior warships. If all went according to plan, the Shinano would join her sisters Yamato and Musashi as the three queens of Second World War battlewagons.RECOMMENDED: North Korea Has 200,000 Soldiers in Its Special Forces Yet by 1942, Japan began to realize that it needed aircraft carriers more than battleships. Naval warfare was now ruled by these floating airfields, and Japan had lost its four best at the Battle of Midway. The orders came down to convert Shinano into an aircraft carrier such as the world had never seen.At 69,000 tons, it was the double the tonnage of the Essex-class carriers that won the Pacific War for America, and would remain the largest until the advent of nuclear-powered carriers in the early 1960s. Its main deck, already sheathed in armor up to 7.5 inches thick, became the hangar deck where aircraft were serviced. On top was the flight deck to launch and recover planes, itself protected by 3.75 inches of armor.RECOMMENDED: How America Would Wage a War Against North Korea Instead of the devastating eighteen-inch cannon of her two sisters, the Shinano's main armament was supposed to be forty-seven aircraft, rather stingy compared to the 75–100 aircraft on large U.S. and Japanese carriers. But its weaponry was still impressive: sixteen five-inch antiaircraft guns, 145 25mm antiaircraft machine guns and twelve multiple rocket launchers with 4.7-inch unguided antiaircraft rockets.The Shinano's designers learned—or thought they had learned—the lessons from the sloppy damage control that had unnecessarily doomed several Japanese carriers. Flammable paint and wood were avoided. Care was taken to protect ventilation shafts so explosive gases couldn't seep through the ship as they had with other Japanese carriers.But the Shinano's impregnability was only skin deep. "Although he was outwardly serene, Captain Mikami felt pressing concern about the ship's watertight compartments," later wrote Joseph Enright, the Archerfish's captain. "The air pressure tests that would have confirmed his hope that the compartments were watertight had been canceled in the rush to move Shinano to the Inland Sea."Sailors can be a superstitious lot, and there was a bad omen when the ship was launched on October 8, 1944 from Yokusuka naval base. A drydock gate buckled, allowing a surge of water to smash the ship against the drydock wall three times. After repairs, it took to sea on November 28, the carrier took to sea with its three-destroyer escort, headed toward the Kure naval base. It carried some suicide boats and kamikaze flying bombs, but no aircraft to fly antisubmarine patrols through Japanese home waters, which were teeming with U.S. submarines.Unfortunately, the Shinano ran into the Archerfish that night, cruising on the surface and on the prowl. The sub was on its fifth war patrol, but it had yet to sink an enemy vessel. Captain Enright decided he needed to sail to a point ahead of his target, submerge so the destroyers wouldn't spot him and fire his torpedoes. That wasn't an easy prospect in World War II, when surface ships could steam faster than submarines.The Archerfish paralleled the Japanese task force. It also turned on its radar to track them, which was detected by receivers on the Shinano. The Japanese captain worried about a massed attack by an American sub wolfpack, but he didn't worry that much. Hadn't the Shinano's sister ship Musashi endured ten torpedo hits and sixteen bombs before succumbing at the Battle of the Philippine Sea? Despite the numerous U.S. subs infesting Japanese home waters, the carrier's watertight doors were opened to allow the crew access to the machinery.The Japanese force zigged and zagged to throw off any undersea pursuers. And then came that bit of luck that often tips every battle. The Japanese ships zigged one more time, straight into the path of the Archerfish. The sub took its chance. At 3:15 am on November 29, it fired six torpedoes. Four hit.Still, the Shinano's crew wasn't unduly worried. The ship was designed to absorb such damage, and in fact continued to try to sail at maximum speed. But water flooded through the holes in the ship's side, flowing into unsecured spaces and through what should have been watertight doors. Pumps and generators failed. Soon the carrier acquired a list to starboard that only got worse.The Shinano's escorting destroyers attempted to tow it, but to no avail. At 10:18 am, seven hours after the attack, the order was given to abandon ship. At 10:57 am the ship sank, along with 1,435 of its crew, including the captain.A postwar U.S. Navy analysis suggested the Yamato-class ships, including Shinano, suffered from design flaws. The joints between the main armored belt and the armored bulkheads below were vulnerable to leakage, and the Archerfish's torpedoes hit that joint. Some bulkheads were also prone to rupture. Then again, the Shinano was hardly the lone victim of subs. The United States lost the carrier Wasp to Japanese torpedo attack, and several British carriers fell victim to German U-boats.Perhaps there was also bad luck. Bad luck into running into the Archerfish, bad luck in zig-zagging straight into the path of a salvo of torpedoes, bad luck that the torpedoes hit a vulnerable spot.In the end, the Shinano would make history—and then sink into the cold, deep waters of the Pacific.Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook.For further reading: Shinano: The Sinking of Japan's Secret Supership by Joseph Enright and James Ryan.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines

Still, the Shinano's crew wasn't unduly worried. The ship was designed to absorb such damage, and in fact continued to try to sail at maximum speed. But water flooded through the holes in the ship's side, flowing into unsecured spaces and through what should have been watertight doors. Pumps and generators failed. Soon the carrier acquired a list to starboard that only got worse.If weight alone could determine victory, then the Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft carrier Shinano might still be afloat.At 69,000 tons when launched in 1944, the Shinano would have remained the world's largest aircraft until the 1960s. But that was not to be. Instead the Shinano earned a distinction of a different kind: the title of largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.(This first appeared several years ago.)And the submarine that accomplished—the 1,500-ton USS Archerfish—was one-forty-sixth the size of its victim.The story begins in May 1940, when the Shinano was laid down as the third of Japan's legendary Yamato-class battleships. These giants were the largest battleships in history, built as part of Japan's desperate attempt to counter U.S. naval quantity with a few—hopefully—qualitatively superior warships. If all went according to plan, the Shinano would join her sisters Yamato and Musashi as the three queens of Second World War battlewagons.RECOMMENDED: North Korea Has 200,000 Soldiers in Its Special Forces Yet by 1942, Japan began to realize that it needed aircraft carriers more than battleships. Naval warfare was now ruled by these floating airfields, and Japan had lost its four best at the Battle of Midway. The orders came down to convert Shinano into an aircraft carrier such as the world had never seen.At 69,000 tons, it was the double the tonnage of the Essex-class carriers that won the Pacific War for America, and would remain the largest until the advent of nuclear-powered carriers in the early 1960s. Its main deck, already sheathed in armor up to 7.5 inches thick, became the hangar deck where aircraft were serviced. On top was the flight deck to launch and recover planes, itself protected by 3.75 inches of armor.RECOMMENDED: How America Would Wage a War Against North Korea Instead of the devastating eighteen-inch cannon of her two sisters, the Shinano's main armament was supposed to be forty-seven aircraft, rather stingy compared to the 75–100 aircraft on large U.S. and Japanese carriers. But its weaponry was still impressive: sixteen five-inch antiaircraft guns, 145 25mm antiaircraft machine guns and twelve multiple rocket launchers with 4.7-inch unguided antiaircraft rockets.The Shinano's designers learned—or thought they had learned—the lessons from the sloppy damage control that had unnecessarily doomed several Japanese carriers. Flammable paint and wood were avoided. Care was taken to protect ventilation shafts so explosive gases couldn't seep through the ship as they had with other Japanese carriers.But the Shinano's impregnability was only skin deep. "Although he was outwardly serene, Captain Mikami felt pressing concern about the ship's watertight compartments," later wrote Joseph Enright, the Archerfish's captain. "The air pressure tests that would have confirmed his hope that the compartments were watertight had been canceled in the rush to move Shinano to the Inland Sea."Sailors can be a superstitious lot, and there was a bad omen when the ship was launched on October 8, 1944 from Yokusuka naval base. A drydock gate buckled, allowing a surge of water to smash the ship against the drydock wall three times. After repairs, it took to sea on November 28, the carrier took to sea with its three-destroyer escort, headed toward the Kure naval base. It carried some suicide boats and kamikaze flying bombs, but no aircraft to fly antisubmarine patrols through Japanese home waters, which were teeming with U.S. submarines.Unfortunately, the Shinano ran into the Archerfish that night, cruising on the surface and on the prowl. The sub was on its fifth war patrol, but it had yet to sink an enemy vessel. Captain Enright decided he needed to sail to a point ahead of his target, submerge so the destroyers wouldn't spot him and fire his torpedoes. That wasn't an easy prospect in World War II, when surface ships could steam faster than submarines.The Archerfish paralleled the Japanese task force. It also turned on its radar to track them, which was detected by receivers on the Shinano. The Japanese captain worried about a massed attack by an American sub wolfpack, but he didn't worry that much. Hadn't the Shinano's sister ship Musashi endured ten torpedo hits and sixteen bombs before succumbing at the Battle of the Philippine Sea? Despite the numerous U.S. subs infesting Japanese home waters, the carrier's watertight doors were opened to allow the crew access to the machinery.The Japanese force zigged and zagged to throw off any undersea pursuers. And then came that bit of luck that often tips every battle. The Japanese ships zigged one more time, straight into the path of the Archerfish. The sub took its chance. At 3:15 am on November 29, it fired six torpedoes. Four hit.Still, the Shinano's crew wasn't unduly worried. The ship was designed to absorb such damage, and in fact continued to try to sail at maximum speed. But water flooded through the holes in the ship's side, flowing into unsecured spaces and through what should have been watertight doors. Pumps and generators failed. Soon the carrier acquired a list to starboard that only got worse.The Shinano's escorting destroyers attempted to tow it, but to no avail. At 10:18 am, seven hours after the attack, the order was given to abandon ship. At 10:57 am the ship sank, along with 1,435 of its crew, including the captain.A postwar U.S. Navy analysis suggested the Yamato-class ships, including Shinano, suffered from design flaws. The joints between the main armored belt and the armored bulkheads below were vulnerable to leakage, and the Archerfish's torpedoes hit that joint. Some bulkheads were also prone to rupture. Then again, the Shinano was hardly the lone victim of subs. The United States lost the carrier Wasp to Japanese torpedo attack, and several British carriers fell victim to German U-boats.Perhaps there was also bad luck. Bad luck into running into the Archerfish, bad luck in zig-zagging straight into the path of a salvo of torpedoes, bad luck that the torpedoes hit a vulnerable spot.In the end, the Shinano would make history—and then sink into the cold, deep waters of the Pacific.Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook.For further reading: Shinano: The Sinking of Japan's Secret Supership by Joseph Enright and James Ryan.

September 02, 2019 at 01:30PM via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

• IJN Shinano

The Shinano was an aircraft carrier built by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during World War II, the largest such built up to that time.

One of two additional Yamato-class battleships ordered as part of the 4th Naval Armaments Supplement Program of 1939, Shinano was named after the old province of Shinano, following the Japanese ship- naming conventions for battleships. She was laid down on May 4th, 1940 at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal to a modified Yamato-class design. As with Shinano's half-sisters Yamato and Musashi, the new ship's existence was kept a closely guarded secret. A tall fence was erected on three sides of the graving dock, and those working on the conversion were confined to the yard compound. Serious punishment—up to and including death—awaited any worker who mentioned the new ship. As a result, Shinano was the only major warship built in the 20th century to have avoided being officially photographed during its construction.

In December 1941, construction on Shinano's hull was temporarily suspended to allow the IJN time to decide what to do with the ship. She was not expected to be completed until 1945, and the sinking of the British capital ships Prince of Wales and Repulse by IJN bombers had called into question the viability of battleships in the war. In the month following the disastrous loss of four fleet carriers at the June 1942 Battle of Midway, the IJN ordered the ship's unfinished hull converted into an aircraft carrier. Her hull was only 45 percent complete by that time, with structural work complete up to the lower deck and most of her machinery installed. The main deck, lower side armor, and upper side armor around the ship's magazines had been completely installed, and the forward barbettes for the main guns were also nearly finished. Shinano was designed to load and fuel her aircraft on deck where it was safer for the ship; experiences in the Battles of Midway and the Coral Sea had demonstrated that the existing doctrine of fueling and arming their aircraft below decks was a real danger to the carriers if they were attacked while doing so. Much of Shinano's hangar was left open for better ventilation, although steel shutters could close off most of the hangar sides if necessary.

The ship was originally scheduled for completion in April 1945, but construction was expedited after the defeat at the Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944 as the IJN anticipated that the United States would now be able to bomb Japan with long-range aircraft from bases in the Mariana Islands. The builder was unable to increase the number of workers on Shinano and could not meet the new deadline of October. Even so, the pressure to finish as quickly as possible led to poor workmanship by the workforce. Shinano's launch on October 8th, 1944, with Captain Toshio Abe in command, was marred by what some considered an ill-omened accident. During the floating-out procedure, one of the caissons at the end of the dock that had not been properly ballasted with seawater unexpectedly lifted as the water rose to the level of the harbor. The sudden inrush of water into the graving dock pushed the carrier into the forward end, damaging the bow structure below the waterline and requiring repairs in drydock.

On November 19th, 1944, Shinano was formally commissioned at Yokosuka, having spent the previous two weeks fitting out and performing sea trials. Worried about her safety after a U.S. reconnaissance bomber fly-over, the Navy General Staff ordered Shinano to depart for Kure by no later than November 28th, where the remainder of her fitting-out would take place. Shinano carried six Shinyo suicide boats, and 50 Ohka suicide flying bombs; her other aircraft were not planned to come aboard until later. Her orders were to go to Kure, where she would complete fitting out and then deliver the kamikaze craft to the Philippines and Okinawa.

On November 29th, American submarine Archerfish, commanded by Commander Joseph F. Enright, picked up Shinano and her escorts on her radar and pursued them on a parallel course. Over an hour and a half earlier, Shinano had detected the submarine's radar. Normally, Shinano would have been able to outrun Archerfish, but the zig-zagging movement of the carrier and her escorts—intended to evade any American subs in the area—inadvertently turned the task group back into the sub's path on several occasions. Assuming Archerfish was being used as a decoy to lure away one of the escorts to allow additional submarines a clear shot at Shinano. He ordered his ships to turn away from the submarine with the expectation of outrunning it. the carrier was forced to reduce speed to 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), the same speed as Archerfish, to prevent damage to the propeller shaft when a bearing overheated. At 02:56 on November 29th, Shinano turned to the southwest and headed straight for Archerfish. Eight minutes later, Archerfish turned east and submerged in preparation to attack. Enright ordered his torpedoes set for a depth of 10 feet (3.0 m) in case they ran deeper than set; he also intended to increase the chances of capsizing the ship by punching holes higher up in the hull. A few minutes later, Shinano turned south, exposing her entire side to Archerfish—a nearly ideal firing situation for a submarine.

Four torpedoes struck the Shinano. The first hit towards the stern, flooding refrigerated storage compartments and one of the empty aviation gasoline storage tanks, and killing many of the sleeping engineering personnel in the compartments above. The second hit the compartment where the starboard outboard propeller shaft entered the hull and flooded the outboard engine room. The third hit further forward, flooding the No. 3 boiler room and killing every man on watch. Structural failures caused the two adjacent boiler rooms to flood as well. The fourth flooded the starboard air compressor room, adjacent anti-aircraft gun magazines, and the No. 2 damage-control station, and ruptured the adjacent oil tank. Though severe, the damage to Shinano was at first judged to be manageable. This overconfidence pushed more water through the holes in the hull resulting in extensive flooding. Within a few minutes she was listing 10 degrees to starboard. At 10:57 Shinano finally capsized and sank stern-first. Over a thousand sailors and civilians were rescued and 1,435 were lost, including her captain. She remains the largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.

#history#imperial japan#japanese history#second world war#world war 2#world war ii#naval history#aircraft carrier#Japanese navy#military history

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Imperial Japan Wanted Battleships with Insane 20-Inch Guns. Here's Why It Never Set Sail

Had the war not come, Japan would have bankrupted itself spending on these massive ships. Japan lacked the industrial capacity to compete with the United States; indeed, even if it had managed to seize and keep wide swaths of East Asia, it could not have matched U.S. industrial production for decades. The United States would have responded to Japanese construction with even larger, more deadly ships, and of course eventually with submarines, aircraft and guided missiles.In January 1936 Japan announced its intention to withdraw from the London Naval Treaty, accusing both the United States and the United Kingdom of negotiating in bad faith. The Japanese sought formal equality in naval construction limits, something that the Western powers would not give. In the wake of this withdrawal, Japanese battleship architects threw themselves into the design of new vessels. The first class to emerge were the 18.1-inch-gun-carrying Yamatos, the largest battleships ever constructed. However, the Yamatos were by no means the end of Japanese ambitions. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) planned to build another, larger class of super battleships, and had vague plans for even larger ships to succeed that class. War interceded, but had Japan carried out its plans it might have deployed monster battleships nearly as large as supercarriers into the Pacific.(This first appeared in 2016.)“Super” YamatosThe A-150 class would have superseded the Yamatos, building on experience with that class to produce a more formidable, flexible fighting unit. Along with the Yamatos, these ships were expected to provide the IJN with an unbeatable battle line to protect its Pacific possessions, along with newly acquired territories in Southeast Asia and China.Recommended: Could the Battleship Make a Comeback? The A-150s would theoretically have carried six 510-millimeter (twenty-inch) guns in three twin turrets, although if problems had developed in the construction of that gun they could have carried the same main armament as the Yamatos. The 510-millimeter guns would have wreaked havoc on any existing (or planned) American or British battleships, but would also have caused substantial blast issues for the more delicate parts of the ship. The A-150s would have carried heavier armor than their smaller cousins, more than sufficient to protect from the heaviest weapons in the American or British arsenals. The secondary armament would have included a substantial number of 3.9-inch dual-purpose guns, a relatively small caliber suggesting that the A-150s may have relied on support vessels to protect them from enemy cruisers and destroyers.Recommended: America's Battleships Went to War Against North Korea Design compromises limited the effectiveness of the Yamatos by reducing their speed and range; they could not keep up with the fastest IJN carriers, and burned too much fuel for economic employment in campaigns such as Guadalcanal. The A-150s would likely have been somewhat faster (thirty knots) than the Yamatos, with a longer range more suitable for missions deep into the Pacific.Recommended: How the U.S. Navy Wanted to Merge Aircraft Carriers and BattleshipsThe construction of the Yamatos challenged the capacity of the Japanese steel and shipbuilding industries, and the A-150s would have strained them even more. For example, producing the armor plate necessary to protect a battleship against twenty-inch guns was simply beyond Japan’s industrial capacity, and would have required serious compromises. Moreover, the IJN would have struggled to surround the A150s with support units. While the USN committed to building an enormous number of heavy cruisers, light cruisers and aircraft carriers in addition to the battleship fleet, Japan completed only a small handful of these ships during the war.Little is known about the successors to the A-150 class, which would have been larger, faster and more heavily armed. Potentially displacing a hundred thousand tons, and carrying eight twenty-inch guns in four twin turrets, even the contemplation of such ships would have required a serious revision of economic realities in East Asia. In any case, the changes in naval technology that rendered the battleship obsolete likely would have become obvious before any of these monsters had entered service.Strategic and Economic FollyJapan ordered two A-150 battleships in the 1942 construction program. The first would have succeeded HIJMS Shinano on the dock; the second, the never named fourth sister of the Yamato class. However, wartime demands for smaller ships (and eventually for aircraft carriers) meant that neither ship was ever laid down.But the war only exposed underlying economic realities; it did not forge them. Japan barely had the industrial capacity to build the initial Yamatos, along with all of the support ships that the battlefleet would require. This is the dirty little secret of the entire Washington Naval Treaty system; the United Kingdom could outpace Japanese construction by a wide margin, and the United States could outpace both combined, if it decided to do so. The treaty system prevented an arms race that Japan could not possibly have won, whether in 1921 or in 1937. Japan’s GDP at the beginning of World War II was a bit over half that of Britain’s, and less than a quarter that of the United States.Japan’s naval success at the beginning of the Pacific War happened because of the treaties, not despite them. The IJN played a poor hand very well, but in any kind of extended naval competition against the United States, the UK, or a combination of the two, it could not win. Upon discovering the existence of these ships, the United States would have begun to construct even larger battleships, as well as other means of sinking large battleships. Indeed, in 1952 the United States laid down USS Forrestal, the first of a class of four aircraft carriers substantially larger than the A-150 class battleships.ConclusionHad the war not come, Japan would have bankrupted itself spending on these massive ships. Japan lacked the industrial capacity to compete with the United States; indeed, even if it had managed to seize and keep wide swaths of East Asia, it could not have matched U.S. industrial production for decades. The United States would have responded to Japanese construction with even larger, more deadly ships, and of course eventually with submarines, aircraft and guided missiles.Warships are (imperfect) reflections of existing economic realities. Timing, technology and grand strategy matter, but in raw competition involving mature technologies, superior economic strength will eventually prevail. The Japanese economy would eventually become competitive with that of the UK, and even the United States, but this would only happen in context of an open trading system with access to the European and American markets. No battleship could carry guns large enough to bring that outcome about.Robert Farley, a frequent contributor to TNI, is author of The Battleship Book. He serves as a Senior Lecturer at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky. His work includes military doctrine, national security, and maritime affairs. He blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money and Information Dissemination and The Diplomat.Image: Wikimedia Commons.(This article originally appeared in 2018.)

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines

Had the war not come, Japan would have bankrupted itself spending on these massive ships. Japan lacked the industrial capacity to compete with the United States; indeed, even if it had managed to seize and keep wide swaths of East Asia, it could not have matched U.S. industrial production for decades. The United States would have responded to Japanese construction with even larger, more deadly ships, and of course eventually with submarines, aircraft and guided missiles.In January 1936 Japan announced its intention to withdraw from the London Naval Treaty, accusing both the United States and the United Kingdom of negotiating in bad faith. The Japanese sought formal equality in naval construction limits, something that the Western powers would not give. In the wake of this withdrawal, Japanese battleship architects threw themselves into the design of new vessels. The first class to emerge were the 18.1-inch-gun-carrying Yamatos, the largest battleships ever constructed. However, the Yamatos were by no means the end of Japanese ambitions. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) planned to build another, larger class of super battleships, and had vague plans for even larger ships to succeed that class. War interceded, but had Japan carried out its plans it might have deployed monster battleships nearly as large as supercarriers into the Pacific.(This first appeared in 2016.)“Super” YamatosThe A-150 class would have superseded the Yamatos, building on experience with that class to produce a more formidable, flexible fighting unit. Along with the Yamatos, these ships were expected to provide the IJN with an unbeatable battle line to protect its Pacific possessions, along with newly acquired territories in Southeast Asia and China.Recommended: Could the Battleship Make a Comeback? The A-150s would theoretically have carried six 510-millimeter (twenty-inch) guns in three twin turrets, although if problems had developed in the construction of that gun they could have carried the same main armament as the Yamatos. The 510-millimeter guns would have wreaked havoc on any existing (or planned) American or British battleships, but would also have caused substantial blast issues for the more delicate parts of the ship. The A-150s would have carried heavier armor than their smaller cousins, more than sufficient to protect from the heaviest weapons in the American or British arsenals. The secondary armament would have included a substantial number of 3.9-inch dual-purpose guns, a relatively small caliber suggesting that the A-150s may have relied on support vessels to protect them from enemy cruisers and destroyers.Recommended: America's Battleships Went to War Against North Korea Design compromises limited the effectiveness of the Yamatos by reducing their speed and range; they could not keep up with the fastest IJN carriers, and burned too much fuel for economic employment in campaigns such as Guadalcanal. The A-150s would likely have been somewhat faster (thirty knots) than the Yamatos, with a longer range more suitable for missions deep into the Pacific.Recommended: How the U.S. Navy Wanted to Merge Aircraft Carriers and BattleshipsThe construction of the Yamatos challenged the capacity of the Japanese steel and shipbuilding industries, and the A-150s would have strained them even more. For example, producing the armor plate necessary to protect a battleship against twenty-inch guns was simply beyond Japan’s industrial capacity, and would have required serious compromises. Moreover, the IJN would have struggled to surround the A150s with support units. While the USN committed to building an enormous number of heavy cruisers, light cruisers and aircraft carriers in addition to the battleship fleet, Japan completed only a small handful of these ships during the war.Little is known about the successors to the A-150 class, which would have been larger, faster and more heavily armed. Potentially displacing a hundred thousand tons, and carrying eight twenty-inch guns in four twin turrets, even the contemplation of such ships would have required a serious revision of economic realities in East Asia. In any case, the changes in naval technology that rendered the battleship obsolete likely would have become obvious before any of these monsters had entered service.Strategic and Economic FollyJapan ordered two A-150 battleships in the 1942 construction program. The first would have succeeded HIJMS Shinano on the dock; the second, the never named fourth sister of the Yamato class. However, wartime demands for smaller ships (and eventually for aircraft carriers) meant that neither ship was ever laid down.But the war only exposed underlying economic realities; it did not forge them. Japan barely had the industrial capacity to build the initial Yamatos, along with all of the support ships that the battlefleet would require. This is the dirty little secret of the entire Washington Naval Treaty system; the United Kingdom could outpace Japanese construction by a wide margin, and the United States could outpace both combined, if it decided to do so. The treaty system prevented an arms race that Japan could not possibly have won, whether in 1921 or in 1937. Japan’s GDP at the beginning of World War II was a bit over half that of Britain’s, and less than a quarter that of the United States.Japan’s naval success at the beginning of the Pacific War happened because of the treaties, not despite them. The IJN played a poor hand very well, but in any kind of extended naval competition against the United States, the UK, or a combination of the two, it could not win. Upon discovering the existence of these ships, the United States would have begun to construct even larger battleships, as well as other means of sinking large battleships. Indeed, in 1952 the United States laid down USS Forrestal, the first of a class of four aircraft carriers substantially larger than the A-150 class battleships.ConclusionHad the war not come, Japan would have bankrupted itself spending on these massive ships. Japan lacked the industrial capacity to compete with the United States; indeed, even if it had managed to seize and keep wide swaths of East Asia, it could not have matched U.S. industrial production for decades. The United States would have responded to Japanese construction with even larger, more deadly ships, and of course eventually with submarines, aircraft and guided missiles.Warships are (imperfect) reflections of existing economic realities. Timing, technology and grand strategy matter, but in raw competition involving mature technologies, superior economic strength will eventually prevail. The Japanese economy would eventually become competitive with that of the UK, and even the United States, but this would only happen in context of an open trading system with access to the European and American markets. No battleship could carry guns large enough to bring that outcome about.Robert Farley, a frequent contributor to TNI, is author of The Battleship Book. He serves as a Senior Lecturer at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky. His work includes military doctrine, national security, and maritime affairs. He blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money and Information Dissemination and The Diplomat.Image: Wikimedia Commons.(This article originally appeared in 2018.)

August 23, 2019 at 11:00PM via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

How the U.S. Navy Sank Imperial Japan's Last Monster-Sized Aircraft Carrier

The Japanese force zigged and zagged to throw off any undersea pursuers. And then came that bit of luck that often tips every battle. The Japanese ships zigged one more time, straight into the path of the Archerfish. The sub took its chance. At 3:15 am on November 29, it fired six torpedoes. Four hit.If weight alone could determine victory, then the Imperial Japanese Navy aircraft carrier Shinano might still be afloat.At 69,000 tons when launched in 1944, the Shinano would have remained the world's largest aircraft until the 1960s. But that was not to be. Instead the Shinano earned a distinction of a different kind: the title of largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.And the submarine that accomplished—the 1,500-ton USS Archerfish—was one-forty-sixth the size of its victim.The story begins in May 1940, when the Shinano was laid down as the third of Japan's legendary Yamato-class battleships. These giants were the largest battleships in history, built as part of Japan's desperate attempt to counter U.S. naval quantity with a few—hopefully—qualitatively superior warships. If all went according to plan, the Shinano would join her sisters Yamato and Musashi as the three queens of Second World War battlewagons.RECOMMENDED: North Korea Has 200,000 Soldiers in Its Special Forces Yet by 1942, Japan began to realize that it needed aircraft carriers more than battleships. Naval warfare was now ruled by these floating airfields, and Japan had lost its four best at the Battle of Midway. The orders came down to convert Shinano into an aircraft carrier such as the world had never seen.At 69,000 tons, it was the double the tonnage of the Essex-class carriers that won the Pacific War for America, and would remain the largest until the advent of nuclear-powered carriers in the early 1960s. Its main deck, already sheathed in armor up to 7.5 inches thick, became the hangar deck where aircraft were serviced. On top was the flight deck to launch and recover planes, itself protected by 3.75 inches of armor.RECOMMENDED: How America Would Wage a War Against North Korea Instead of the devastating eighteen-inch cannon of her two sisters, the Shinano's main armament was supposed to be forty-seven aircraft, rather stingy compared to the 75–100 aircraft on large U.S. and Japanese carriers. But its weaponry was still impressive: sixteen five-inch antiaircraft guns, 145 25mm antiaircraft machine guns and twelve multiple rocket launchers with 4.7-inch unguided antiaircraft rockets.The Shinano's designers learned—or thought they had learned—the lessons from the sloppy damage control that had unnecessarily doomed several Japanese carriers. Flammable paint and wood were avoided. Care was taken to protect ventilation shafts so explosive gases couldn't seep through the ship as they had with other Japanese carriers.But the Shinano's impregnability was only skin deep. "Although he was outwardly serene, Captain Mikami felt pressing concern about the ship's watertight compartments," later wrote Joseph Enright, the Archerfish's captain. "The air pressure tests that would have confirmed his hope that the compartments were watertight had been canceled in the rush to move Shinano to the Inland Sea."Sailors can be a superstitious lot, and there was a bad omen when the ship was launched on October 8, 1944 from Yokusuka naval base. A drydock gate buckled, allowing a surge of water to smash the ship against the drydock wall three times. After repairs, it took to sea on November 28, the carrier took to sea with its three-destroyer escort, headed toward the Kure naval base. It carried some suicide boats and kamikaze flying bombs, but no aircraft to fly antisubmarine patrols through Japanese home waters, which were teeming with U.S. submarines.Unfortunately, the Shinano ran into the Archerfish that night, cruising on the surface and on the prowl. The sub was on its fifth war patrol, but it had yet to sink an enemy vessel. Captain Enright decided he needed to sail to a point ahead of his target, submerge so the destroyers wouldn't spot him and fire his torpedoes. That wasn't an easy prospect in World War II, when surface ships could steam faster than submarines.The Archerfish paralleled the Japanese task force. It also turned on its radar to track them, which was detected by receivers on the Shinano. The Japanese captain worried about a massed attack by an American sub wolfpack, but he didn't worry that much. Hadn't the Shinano's sister ship Musashi endured ten torpedo hits and sixteen bombs before succumbing at the Battle of the Philippine Sea? Despite the numerous U.S. subs infesting Japanese home waters, the carrier's watertight doors were opened to allow the crew access to the machinery.The Japanese force zigged and zagged to throw off any undersea pursuers. And then came that bit of luck that often tips every battle. The Japanese ships zigged one more time, straight into the path of the Archerfish. The sub took its chance. At 3:15 am on November 29, it fired six torpedoes. Four hit.Still, the Shinano's crew wasn't unduly worried. The ship was designed to absorb such damage, and in fact continued to try to sail at maximum speed. But water flooded through the holes in the ship's side, flowing into unsecured spaces and through what should have been watertight doors. Pumps and generators failed. Soon the carrier acquired a list to starboard that only got worse.The Shinano's escorting destroyers attempted to tow it, but to no avail. At 10:18 am, seven hours after the attack, the order was given to abandon ship. At 10:57 am the ship sank, along with 1,435 of its crew, including the captain.A postwar U.S. Navy analysis suggested the Yamato-class ships, including Shinano, suffered from design flaws. The joints between the main armored belt and the armored bulkheads below were vulnerable to leakage, and the Archerfish's torpedoes hit that joint. Some bulkheads were also prone to rupture. Then again, the Shinano was hardly the lone victim of subs. The United States lost the carrier Wasp to Japanese torpedo attack, and several British carriers fell victim to German U-boats.Perhaps there was also bad luck. Bad luck into running into the Archerfish, bad luck in zig-zagging straight into the path of a salvo of torpedoes, bad luck that the torpedoes hit a vulnerable spot.In the end, the Shinano would make history—and then sink into the cold, deep waters of the Pacific.Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook.For further reading: Shinano: The Sinking of Japan's Secret Supership by Joseph Enright and James Ryan.

from Yahoo News - Latest News & Headlines