#Inscription: The Journal of Material Text

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Books On Books Collection - Carolyn Thompson

View On WordPress

#Carolyn Thompson#D. H. Lawrence#Giovanni Boccaccio#Inscription: The Journal of Material Text#Laurence Sterne Trust#Søren Kierkegaard#Truman Capote

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[...] things are never innocent beings, they are never just there as simple means towards our ends. [...] We constantly enroll things and charge them with our values and meaning [...]. These inscriptions are successful because things outlive us [...]. Things should, therefore, rather be thought of as ‘political locations’ (Introna, 2009), charged with values, that may be negotiated or even ignored, but are also, because of their [...] durability, somewhat involuntarily re-membered into ever new presents and ever new contexts. We need to be aware of this power of things. That is, we should not rule out the possibility that sometimes ‘... we find what was meant to be found ...’ (Gonzalez-Ruibal, 2011), that Stonehenge isn’t simply any collection of rocks [...].

---

Many people I’ve met [at] the [abandoned early-20th-century Icelandic] herring factories have told me they visit the sites regularly [...] because, they claim, they admire their unruly and ever changing appearance. But what is it that has this effect? [...] Notwithstanding the sites’ historical significance, the ruins left in these northern fjords also become potential agents of disruption and ‘actualization’, triggering a particular kind of involuntary memory [...].

Their presence, an anomaly within the contemporary geopolitical order, bears witness to alternative geographies, other cultural and economic landscapes, to past presences in strange places. A material mnemonic, thus, of a less retrospective and more contemporary social significance; one that calls attention to the fragile dialectics between nature and culture, between [...] centres and peripheries, and, importantly, between heritage and waste. [...] [P]ersisting in this remote and sparsely populated landscape, these untimely ruins silently, but effectively, divert our attention to the perhaps unreconciled tension between the ‘authentic’ Viking and Saga dominated past that roots the nation’s identity and strongly affects its heritage conceptions [...], and the later period of industrialization [...] that provided [...] modernity. [...]

---

Valuing ruination and decay -- how is that heritage management? [...] [T]he answer is simple: it [isn’t]. The traditional idea is that as things or sites become heritage they should, by means of management and conservation, be [...] turned into frozen facts, into stable points of departure [...]. In other words, things are made manageable [...]. But maybe there is room for a different kind of heritage conception, one that is open to the life of things, materiality as dynamic [...].

And is it not possible that valuing ruins as ruins [...] might add to our understanding of things, their temporality and being [...]? The ‘modern’ regime has the tendency to tidily organize our messy being into sealed [...] ontological compartments [...].

What is reassuring of well-managed heritage and properly curated museums is that they provide visitors with an epistemological security by constraining the possibilities of interpreting or encountering things [...]. In ruination that safety net is lost [...].

The undisciplined ruin confronts our customized habit of dealing with things as tame domesticated possessions -- as conventional heritage. The ruin presents itself partly as mystery; things are allowed to be themselves, making their presence more manifest, disquieting [...]. The forms of things are foregrounded: their texture, their smell and their utter silence [...].

---

Text by: Þo ́ra Petursdottir. “Concrete matters: Ruins of modernity and the things called heritage.” Journal of Social Archaeology Volume 13 Issue 1. 2013. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

#ruins#narrative#nations and states controlling interpretations via knowledge institutions and selective curation#today someone resurrected an older post where i shared most of these same excerpts#and i was reminded of how much i like some of these turns of phrases#temporality#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies#debt and debt colonies#debris and ruination#haunting#tim edensor#avery gordon

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

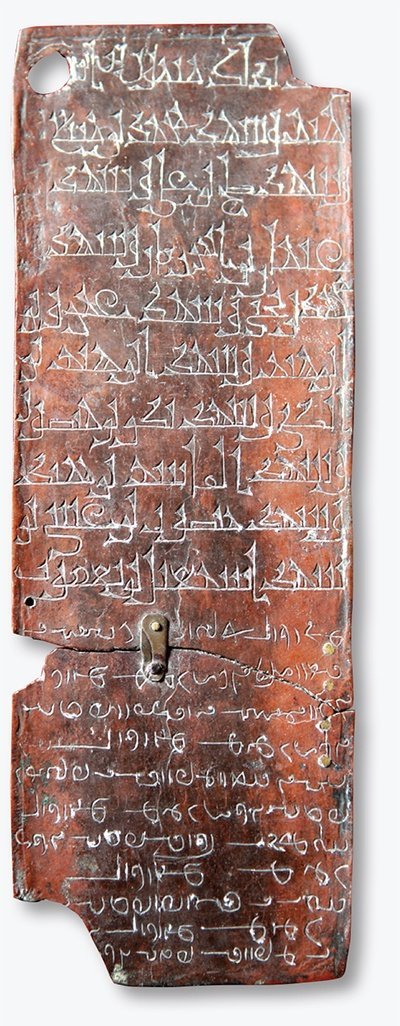

An early Hebrew inscription from Mount Ebal near Nablus that was found on a folded lead tablet during an excavation in the 1980s recently underwent x-ray tomographic measurements to reveal hidden text.

Epigraphic analysis of the data revealed a formulaic curse written in a proto-alphabetic script likely dating to Late Bronze Age that predates any previously known Hebrew inscription in Israel by at least 200 years.

The finding has just been published in the journal Heritage Science by Prof. Gershon Galil, a researcher at in Jewish history and biblical studies at the University of Haifa; Scott Stripling of the Archaeological Studies Institute in Katy, Texas; Ivana Kumpova, Daniel Vavrik and Jaroslav Valach of the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics the Czech Academy of Sciences; and Pieter Gert van der Veen at the Department of Old Testament and Biblical Archaeology at the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz in Germany.

The inscription was: “You are cursed by the God YHW.”

(L-R) XCT reconstruction of the tablet. Optical reconstruction by digital photogrammetry. (credit: DANIEL VAVRIK, JAROSLAV VALACH)

In December 2019, an expedition on Mount Ebal to wet sift the discarded material from excavations led by Adam Zertal – a prominent but controversial University of Haifa archaeologist who died at the age of 79 in 2015 – from decades earlier, yielded a small, folded lead tablet.

The east dump pile from which the object emerged contained the discarded matrix from two structures that he interpreted as altars dated to the Late Bronze Age II and Iron Age I. The earlier and smaller round altar lay underneath the geometric center of the later and larger rectangular altar.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

How do you know so much about runes? I’ve always admired your blog because of that! And what is your advice on getting to study them?

I studied runology at the University of Copenhagen for a semester which gave me the research skills to keep learning on my own, informed by the linguistics training I got at the University of Iceland. I was given a private lesson by a professional runologist on how to use the Rundata program. I lived in rural Denmark for half a year and could get on my bike and go look at monuments and inscriptions whenever I wanted. I had access to academic journals, university libraries, and actual manuscript collections for years.

So, you know, just do that.

Seriously though, I don’t know how I would have done it without the privileges I’ve had and that is a real problem for anyone who (like me) wants to generalize this knowledge and make it accessible to everyone. I do know a couple of people who have managed to acquire similar skills without academic training so it is possible but difficult. Part of the reason I blog is the fact that I have experiences that others don’t and therefore it’s my responsibility to share the wealth. I don’t think that this blog is the best way to do that but it’s the way that I have time and knowledge for. I’ve tried poking around at people who follow this blog to see what kinds of interests people have in runes to try to figure out how to help develop those interests into skills but that has mostly been a failure, except for a couple of followers who would be doing that with or without me. So I am not really the person to ask. Maybe @obligate-rebel has some advice.

What advice I do have it this:

I’ve said this a lot and I’ll keep saying it. EVERY SINGLE THING WITHOUT EXCEPTION that we know about runes is traceable to something that EXISTS PHYSICALLY in the world and could theoretically be touched with your hands. Learn how to figure out what that object is. If someone says “the Icelandic rune poem says that...” you need to hold them to providing you with the tools to lead you to, e.g., AM 687 d 4to. If the evidence for a statement was burned in the Copenhagen fire and there’s only a drawing of it now then the evidence is the drawing. If a folklorist collected a galdrastafur then the evidence is the folklorist’s field notes, and if not that then the published book, and knowing the difference between a symbol carved on a doorframe, a symbol copied into field notes, and a symbol in a published book is non-trivial, vital information. UNTIL YOU UNDERSTAND THE LANGUAGE THE EVIDENCE IS THE EDITION OF THE TRANSLATION YOU’RE READING FROM, not some abstract “it says this.” And understanding the language also STILL requires physical evidence which is why when I do deep dives into Old Norse language stuff I either do or could (or should be made to) provide references in the Dictionary of Old Norse Prose, the Cleasby-Vigfússon dictionary, the Scandinavian Rune-text Database, etc.

This doesn’t mean speculation isn’t useful, it means the “source” of that speculation is the person speculating and wherever the published it and that is different from “our ancient ancestors believed _____”

Study the language. I know it sounds gatekeepy when I say it, and yeah, again, I had actual professional help in a country where I could take the lessons I learned in Old Norse class and then go to the grocery store and use it and it isn’t fair that I get that and others don’t. I don’t know what to tell you.

what exactly this means depends on your goals and I don’t mean learning to produce old Germanic language on the spot so much as like “can use a dictionary effectively.” See https://thorraborinn.tumblr.com/post/617681366444916736/germanic-lexicon-project-an-icelandic-english

If you’re going to go all-in and study Old Norse (which if your interest is runes then you should study Norse because the vast vast vast majority of runic material is in Norse) then I do recommend studying Modern Icelandic (i.e. with Icelandic Online) since there are much better learning tools available and then learning the relatively few differences between Old and Modern Icelandic.

but also, a lot of the stuff that you can find on my blog, that qualifies me as knowing more about runes than other people, is because I can read things that have never been translated from Icelandic. Until there are translations there is no way around the fact that if you can’t read Icelandic you can’t read those manuscripts and have to ask people like me to be a mediator. This is also true of material in German which is inaccessible to me, because I don’t know German.

I’m not saying “study Icelandic and then Old Norse and then Proto-Germanic and then you can learn runes,” you can and should do these things concurrently because they give each other context, but if you’re reading a runic inscription with transliteration and translation, take the time to dissect it and figure out which words are which and stuff like that

Learn about what reference material is available to you. I don’t know that much off the top of my head. When I give complicated answers to things here I am using reference material to look stuff up. That includes but is not limited to The Dictionary of Old Norse Prose, Rundata, Arild Hauges Runer, the Cleasby-Vigfússon dictionary, the Skaldic Poetry Project, and others that I’m not thinking of right now.

Don’t read Edred Thorsson, Diana Paxson, Freya Aswynn, Paul Rhys Mountfort, anything related to the Rune Gild, etc. until after you are able to look at a runestone and evaluate the interpretations that are already proposed for yourself. Then pirate some Thorsson stuff so you can understand why heathens who know absolutely nothing about runes declare themselves to be “vitkar.”

Do read this stuff: https://thorraborinn.tumblr.com/runes

Make habits that will last you for years instead of trying to do anything instantly. It took me two years of structured academic study to start to approach competence and now I can’t read anything I wrote from then because I have continued to learn since then.

(edit) oh yeah and pirate books. Steal the fuck out of them. Most Norse studies scholars will secretly agree in private. Just fuckin steal everything.

Ask me or someone else when you get stuck. Seriously. Like I said I got a private lesson during office hours in how to use the most powerful but clunky and annoying tool for researching runes, I didn’t do this by myself. But hold them to the first point.

Also fwiw I’m ADHD and for some reason I fixate on runes and certain specific linguistics topics that everyone else finds mind-numbingly boring. Like, “nothing else exists” fixate (especially during the years when I smoked shitloads of weed while studying).

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Priapus of the sailors

About two weeks ago I wrote about Aphrodite and her role as a sea goddess. Finding the epigrams about this aspect of hers led me to a rabbit hole of extracting dedicatory epigrams from the Palatine Anthology. Sixteen of them mentionned Priapus, of those, eleven epigrams present Priapus under a different aspect than the one we are used to: as a god of sailing and patron to fishermen.

Priapus is a complex and foreign god. Myth makes Aphrodite abandon him in the city of Lampsacus in Asia Minor (now in Turkey), which is, in fact where his cult is attested as soon as the 4th century BC. Mainland Greece wouldn't adopt him until a century later at least.

The Palatine Antholology epigrams

I won't be listing all eleven, as some are very similar. So I chose three of them as example:

Maecius Quintus “Priapus, who does delight in the sea-worn rocks of this island near the coast, and in its rugged peak, to you does Paris the fisherman dedicate this hardshelled lobster which he overcame by his lucky rod. Its flesh he roasted and enjoyed munching with his half-decayed teeth, but this its shell he gave to you. Therefore give him no great gift, kind god, but enough catch from his nets to still his barking belly.”

Anonymous “You fishermen who pulled your little boat ashore here (Go, hang out your nets to dry) having had a haul of many sea-swimming gurnard (?) and scarus, not without thrissa, honour me with slender first- fruits of a copious catch, the little Priapus under the lentisc bush, the sea-blue god, the revealer of the fish your prey, established in this grove.”

Theaetetus Scholasticus “Already the fair-foliaged field, at her fruitful birth-tide, is aflower with roses bursting from their buds ; already on the branches of the alleyed cypresses the cicada, mad for music, soothes the sheaf-binder, and the swallow, loving parent, has made her house under the eaves and shelters her brood in the mud-plastered chamber. The sea sleeps, the calm dear to the Zephyrs spreads tranquilly over the expanse that bears the ships. No longer do the waters rage against the high-built poops, or belch forth spray on the shore. Mariner, roast first by his altar to Priapus, the lord of the deep and the giver of good havens, a slice of a cuttle-fish or of lustred red mullet, or a vocal scarus, and then go fearlessly on your voyage to the bounds of the Ionian Sea.”

The Palatine Anthology is a difficult source, as it is a late Byzantine text that gathers epigrams from different periods of Antiquity and attributed to various authors. The epigrams alone do not constitute a solid foundation to come to conclusion, but we can clearly see a trend of associating the god with humble fishermen and other mariners.

Archaeological evidence

Thankfully, there are archaeological elements that seem to back up the importance of Priapus as a sailing deity.

Let's start with this 3rd century BC Greek inscription:

"I, Priapus, the Lampsacan, am at hand to help the city in any way, I who embark and return bringing wealth"

What is especially interesting with this inscription is that it predates a lot of the roman material we have for Priapus and gives us a more accurate idea of his role as a deity. However, his function has a wealth and luck bringer stayed the same over the centuries, whether that is through a bountiful harvest or fishing.

Findings of a terracotta phallus in the Pisa Ship E has been used a suggestion that Priapic images were carried aboard of Roman ships as a protective device. However, the problem with this particular phallus is that nothing else nearby where it was found indicated a religious context. Another find, coming from another wreck, the Planier A, found near Marseilles (France) is more explicit. The ship, dating back to the 1st century AD, contained a wooden figurine which hs been identified as Priapus: the figurine shows him lifting his tunic to show his member. The phallus is now absent. The figurine has a socket where the phallus would be, indicating that the phallus was a seperate piece that would be attached to the figurine.

In the same wreck has been found another wooden figure, which depicts a man in a toga. Taken as a pair, they would indicate the presence of an onboard shrine (lararium) directly on the ship. The other figurine could represent the captain or the ship’s genius. Either way, the shrine's role was probably linked to guaranteeing the safety of the ship, the crew and the cargo.

One last example before wrapping up this post: underwater survey on the coasts of Caesarea (Israel) brought up a bronze figurine portraying Aphrodite with her son, Priapus. The statuette was found at a depth where other Roman artefacts were found, which places it around the second half of the 1st century AD. This statuette is also thought to be part of objects brought by mariners aboard to bring them luck and protection.

Aphrodite and Priapus being honored together is a very interesting contrast with myth, where Aphrodite is portrayed as too disgusted by her son's ugliness to accept him. Yet, Priapus has inherited of his mother's role as a protector to seafarers.

Further reading:

Neilson III R. H., A terracotta phallus from Pisa Ship E: more evidence for the Priapus deity as protector of Greek and Roman navigators, in: The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 2002 Galili E., Rosen B., Protecting the ancient mariners, cultic artifacts from the holy land seas, in: Archaeologia Maritima Mediterranea, 2015 Paton R. W., The Greek Anthology, Volumes 1 and 4, 1927

#priapusdeity#aphroditedeity#hellenic polytheism#hellenic paganism#hellenic pagan#hellenic polytheist#hellenismos

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Love and Humility are the sweet bonds of our marriage:” A Book of Hours owned by the wife of a French Catholic propagandist of the 16th century, and the Governor of Pennsylvania!

Fifty-two discoveries from the BiblioPhilly project, No. 7/52

Book of Hours, Use of Paris, Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1924‑19‑1, fol. 24r (miniature of the Annunciation from the Hours of the Virgin)

Books of Hours are highly mobile objects that can often accrue fascinating later histories. Because of their deeply personal nature, they can become associated with historical persons either through legend or fact (or a combination of the two). Only relatively rarely, however, does one later owner purchase a book on account of its earlier ownership history. One such example is a fairly modest Parisian Book of Hours acquired by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1924 (accession number 1924‑19‑1). Unlike the later ensembles of illuminated manuscripts donated to the museum by Samuel and Vera White or Philip S. Collins, this manuscript was not published or described upon its entry into the collection.[1] Its only existing description comes from Seymour de Ricci’s Census of Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts in the United States and Canada and its later Supplement, produced by C.U. Faye and W.H. Bond.

In both Census volumes, the manuscript’s early provenance with the Duderé family in France is briefly recorded, as is its later ownership in the United States by Samuel W. Pennypacker, 23rd Governor of Pennsylvania (1843–1916), who served from 1903 to 1907 (and to whom we shall return). The Duderé provenance is evident through two unequivocal inscriptions within the manuscript. The first, on folio 1r, reads:

1924‑19‑1, fol. 1r, with ownership inscription of Michelle Duderé dated to 1577

Ces heures apartiennent a damoyselle Michelle du Deré femme de Me Loys Dorleans aduocat en la court de Parlement et lesquelles luy sont echeues par la succession de feu son pere Me Jehan Duderé conseiller du roy & auditeur en sa chambre des comptes, 1577; Amour & Humilité sont les doux liens de nostre mariage.

(“This Book of Hours belongs to Lady Michelle du Deré wife of Mr. Louis d’Orléans advocate in the court of Parliament and it descended from her deceased father Mr. Jean Duderé counsellor of the King and auditor in his chamber of accounts. 1577. Love and Humility are the sweet bonds of our marriage.”)

It thus transpires that the book was in the possession of Michelle Duderé, wife of the noted French Catholic League pamphleteer Louis Dorléans (1542–1629).[2] In addition to being known for authoring numerous religious tracts, Dorléans was also an occasional poet, and wrote some bucolic verses replete with thinly-veiled references to his beloved wife, but also to his former mistress Catherine de la Sale![3] Interestingly, some of his writings also show an unusual knowledge of Middle French poetry; he even donated a fourteenth-century French translation of the Golden Legend to a Minim convent in Paris in 1561 (Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine, ms. 1279). Michelle Duderé, as she herself tells us in the inscription, had inherited the Book of Hours from her father, Jean Duderé, notary and secretary to the French king, whose principal historical importance seems to have been his invocation in a seventeenth-century lawsuit concerning the inheritance of such royal appointments. It appears that the manuscript was then gifted by Michelle Duderé’s blind son to a cousin once-removed, a certain G. Duderé, for on the verso of the first folio we read another French inscription, written some seventy-three years later:

1924‑19‑1, fol. 1r, with ownership inscription of G. Duderé dated to 1650

Ce présent livre m’a esté donné par feu monsieur d’Orléans, fils de mademoiselle d’Orléans nomée Michelle Duderé lequel estoit aveugle et qui estoit digne de cette affliction, mon cousin germain, G. Dudere 1650… les figures qui sont à genoux dans les ymages de ce livre sont de feu damoiselle Michelle de Sauslai [?] mère de deffunct mon frère.

(“This present book was given to me by the late Monsieur D’Orleans son of Madame D’Orleans named Michelle Dudere. He was blind and worthily bore this affliction, my cousin once removed. G. Dudere 1650… the figures which are on their knees in the pictures of this book are portraits of the deceased demoiselle Michelle de Sauslai [?], mother of my deceased father.”)

1924‑19‑1, fols. 124r and 130r (miniature of the Virgin and Child with Angel with a female donor; miniature of the Trinity with an Angel holding the Crown of Thorns with a female donor)

The supposition that the two donor portraits (on folios 124r and 130r; illustrated above) contained in the book depict a certain “Michelle de Sauslai” (?), grandmother of the owner alive in 1650 is manifestly incorrect, since the book dates from the fifteenth century. But there is no reason to doubt the other pieces of evidence situating the book with the Duderé family early in its history.

Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker (1843–1916)

This is all fine and well, but how did the manuscript come to be owned by the Governor of Pennsylvania, Samuel Pennypacker? Pennypacker was a noted jurist, trustee of the University of Pennsylvania, president of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and local history enthusiast who collected a large amount of material related to the early German and Dutch settlement of South-Eastern Pennsylvania, most of which is today preserved at the Pennypacker Mills house museum. Other manuscripts once owned by Pennypacker that are still in Philadelphia include another Book of Hours (Lewis E 116) and a series of astronomical tables followed by a short text concerning astrology and planetary movements (Lewis E 3), both of which are today in the Free Library. These manuscripts were all auctioned off in the Pennypacker sale in 1906, together with a small number of other manuscripts. Additionally, for the present manuscript, the Faye and Bond supplement to de Ricci’s Census includes the name of an additional owner, the noted Chestnut Hill philanthropist, John Story Jenks (1839–1923). Jenks was a great supporter of the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (the precursor of the Philadelphia Museum of Art), as a short obituary confirms.[4] It was he who left the manuscript to the museum upon his death.

Portrait of John Story Jenks (1839–1923) by Alice Mumford Roberts

So why did Governor Pennypacker purchase this particular French Book of Hours, prior to its acquisition and donation by Jenks? The answer is provided in an all-but-forgotten issue of a regional historical journal, The Perkiomen Region, Past and Present, published in March of 1901 by Henry S. Dotterer (1841–1903). The short article, entitled “A Sumptuous Devotional Book,” vividly describes the book and asserts that the Governor:

…purchased it because he felt convinced that the family of Duderé mentioned in the inscription was identical with an old Pennsylvanian family—that of Doderer, Dotterer, Dudderer, Duttera, Dudderow. This conviction induced him to pay the large sum quoted for it by the foreign bookseller [i.e. James Tregaskis of London], and to bring it, after a service of more than three centuries, from its native France to the New World.

To find the connecting links from the Duderés of the Sixteenth century to the Dotterers of the Twentieth century would be a great genealogical achievement. Doderers and Dotterers appear in various parts of Europe prior to the date of the arrival, about 1722, of George Philip Dodderer, or Dotterer, in Pennsylvania. Tradition, in some instances, asserts that the Pennsylvania immigrants were of French origin; but not uniformly so, for Alsace, Baden, Wurtemberg and Austria are also named as the place of their nativity. We have unbounded respect for Judge Pennypacker’s insight into genealogy, ethnology, and the kindred sciences, and it will therefore not be a surprise to us if research shall ultimately prove that his intuitions are correct.[5]

The prominent Dotterer family of Pennsylvania was established by George Phillip Dotterer (ca. 1676–1741), who was born in Baden-Württemberg and died in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, in 1741. George’s father Hans is thought to have been born in the same region of Germany as his son around 1650. However, this family’s link to the prominent Catholic Duderés of France remains tenuous. As such, Governor Pennypacker’s assumption remains unlikely; perhaps his doubts led him to sell the book on in his 1906 sale. In any case, both G. Duderé’s misattribution of the portraits in the book and the dubious linkage to the Dotterer dynasty made by Governor Pennypacker demonstrate the extent to which an unsuspecting manuscript can become the subject of historical wishful thinking.

[1] Henry G. Gardiner, “The Samuel S. White, 3rd, and Vera White Collection,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 63, no. 296/297 (1968): 71–150, http://bit.ly/2Hc3lI4; Carl Zigrosser, “The Philip S. Collins Collection of Mediaeval Illuminated Manuscripts,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 58, no. 275 (1962): 3–34, http://bit.ly/2Vt3u3u.

[2] See the entry by Christophe Bernard in Dictionnaire des lettres françaises: le XVIe siècle, ed. Michel Simonin (Paris: Fayard-La Pochothèque, 2001), 370–71.

[3] Anne-Bérangère Rothenburger, “L’Eglogue de la naissance de Jésus-Christ pas Louis Dorléans: datation et filiation poétiques,” in Le poète et son œuvre: de la composition à la publication, ed. Jean-Eudes Girot (Geneva: Droz, 2004), 259–87.

[4] Pennsylvania Museum Bulletin 18, no. 77 (May 1923): 16.

[5] Henry S. Dotterer, “A Sumptuous Devotional Book,” The Perkiomen Region, Past and Present 3, no. 2 (March 1901): 166–7.

from WordPress http://bibliophilly.pacscl.org/love-and-humility-are-the-sweet-bonds-of-our-marriage-a-book-of-hours-owned-by-the-wife-of-a-french-catholic-propagandist-of-the-16th-century-and-the-governor-of-pennsylvania/

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

When We Meet Again Ch. 1

AO3 Link / FF.net Link

Summary: Rachel Gardner, a brilliant archaeologist, goes deep into the jungle to research an ancient civilization. Finding a tomb deep underground, she accidentally awakens a serial killer who was cursed to sleep for eternity. But after he awakens, Rachel discovers she's the reincarnation of someone he knew and swore to protect. She must hide his existence from everyone to ensure his own safety, and maybe learn something about him and her past life.

Rachel Gardner ignored the pleas of her fellow researchers as she ventured further into the Melica Jungle. It was said to be a vast well of knowledge for archaeological research, inhabited thousands of years ago by an intelligent civilization known as the Himates. However, exploring such uncharted territory proved to be quite the feat. Rachel had narrowly avoided snake pits and quicksand. She expertly avoided very well-made traps on her journey. These facts led her to believe she was close to her destination. From her notes, the Himates liked to be an isolated and independent civilization, deterring any foreign presence whenever possible.

She didn't mind going into the unexplored terrain alone. Her many journeys, from the deep slopes of the Grand Canyon to the scorching heat of the Sahara, had toughened her up enough to withstand the harshest conditions and most treacherous threats. Add that to the fact that she didn't exactly fear death. Even stuck in her musings, Rachel managed to tiptoe around a handful of spike falls that were cleverly hidden. She was well-versed in setting traps, for reasons she never discussed with anyone.

The archaeologist treading through the trees carefully, looking back to only see thick foliage. She had gone far off the trail, and her colleagues were nowhere in view. She couldn't hear them, even if she strained her ears. Huffing a quiet sigh, Rachel continued her journey, using the hunting knife she had equipped to cut through extra thick bushes and clearing the way for her. At the end of the tree line, a same cave came into view. Her blue eyes were transfixed on the structure as she climbed her way out of the forest and to open space.

Brushing a strand of blonde hair that had fallen out of her ponytail behind her ear, the young woman reached inside the bag at her hip to pull out her journal and pen. She noticed the multitude of symbols etched onto the outer lips on the cave. They seemed to give off a hostile aura, warning newcomers of the impending danger ahead. The shapes swirled and curved in waves that seemed to ask the reader of the texts to turn back and never return. They even depicted deadly mythical monsters, with horns and giant claws, and a sort of fire. However, Rachel already made her way past the ancient jungle traps, so she proved to have the intellect necessary to outsmart the ancient Himates. She jotted the symbols down to translate later, then swiftly closed her book and tucked it back in its proper place.

With a firm resolve, the blonde woman walked forward, her dirty brown hiking books stepping from soft dirt to hardened stone upon passing the cave's entrance. She kept silent to listen to the occurrences surrounding her. The breeze from the outside whistled softly as it blew through the entrance, moving tiny pebbles and speckles of dirt around gently. When Rachel made her way a few yards into the cave, she stopped and closed her eyes. In her mind, she could see events that took place thousands of years ago, in this very cave. It was one of her talents; to close her eyes and let the locations and artifacts speak to her with images of their ancient history in her mind's eye.

She envisioned the ghosts of ancient people with slightly darker skin tones than her passing her by as they went about their unknown routines. She noticed the thin white clothing, showing just enough skin to remain unbothered by the elements. A majority of their clothing was white, to reflect the light of the scorching sun. Most of them wore silver accessories, armlets and usekh collars. Only the occasional man or woman had their accessories in gold. They were dressed a little more elegantly than others, symbolizing their possible higher status. It seemed menial labor fell on the lower class; the ones in silver carrying baskets and heavy bowls packed with food, spices, or anything valuable to their cultures. The ones in golden carried incense jars and feather fans; much lighter but equally valuable objects. Rachel deduced the cave held an altar somewhere inside, dedicated to one of their gods.

The archaeologist opened her eyes, the figures gently wisping away with the breeze. She took out her journal again, jotting down images from her visions. She focused further ahead afterward. The cave appeared to go much further. Rachel carefully made her way into the depths, flickering on her flashlight once natural light no longer shone where she was heading. She observed the cave's walls, studying the symbols and artwork that lined that stone. Whoever drew them must have had excellent precision to make sure perfect art. The air around her slowly became colder, the draft nipping at her arms. She nonchalantly rubbed her skin to generate heat and bring down the rising goosebumps.

Rachel reached what she believed was finally the back on the cave. A dusty and deteriorated altar stood atop a small set of natural stone steps. The Himates were intelligent, using the cave's pre-existing curves and slopes to build their place of worship. She studied the room, taking in the exquisite detail. She could vividly picture the room in its original state; flames flicking from candles on the golden candelabras and a white stone decorated in fine cloth with expensive materials sitting atop.

The young woman was entranced by the structure, the technology, the history. She was captivated by the history of these people. She loved getting lost in the past; a much simpler time with everyone doing their part to survive and thrive. She wished the modern world could be more like that. Unfortunately, Rachel was stuck in her musings. She unknowingly backed up as she pored over the drawings and writing on the walls of the cave, trying to decipher the god that was worshiped at this specific altar, possibly learned why it was isolated to this cave. Her elbow knocked into the wall behind her. Oceanic eyes widened as she felt her appendage sink into the wall.

A trap?!

Rachel jumped slightly as the cave began to quake, taken mildly by surprise. The tremors knocked her off balance, causing her to yelp softly when her rear hit the cold stone ground. The vibrations slowly calmed, and the woman blinked, carefully rising to her feet. An opening in the floor revealed a long staircase leading into pitch black. She weighed her options; go further to either make a great discovery or meet her end, or she could turn back and never mention the hidden stairwell in her reports. One foot forward and her flashlight pointed towards the stairs was enough to let anyone know she had chosen the former.

The journey down was quite a trek, her knees weakening the farther she descended. But she wasn't one to give up so easily. Without a proper perception of time, the time it took until her feet finally touched flat land fell like hours. The blonde's eyes widened to see a small room at the bottom, dimly lit by a strange light that seemed to come from within the stone walls. But she couldn't take the time to meticulously explore everything. But she didn't want anyone to find the cave's hidden room and cover the entrance back up without realizing her whereabouts, leaving her trapped.

The walls were covered in dust and vines that seemed to thrive under the conditions the underground room provided. So she couldn't appropriate see what lay underneath. However, one thing in the room caught her eye, and for good reason. A rusty sarcophagus lay flat on a slightly raised platform. It was nowhere near as elegant or sophisticated as one from the Egyptians, for example. It looked as if it was purposefully neglected, as a sign of disrespect to whomever laid within. There were no decorations or symbols to tell of who exactly was inside. There was only a single line of Himatean inscription. Unfortunately, she hadn't translated those specific words yet.

A silver lock rested on the sarcophagus, seemingly untouched. It wasn't rusted like the rest of the piece but appeared fairly new. A beautiful ruby rested in the center, its gleam beckoning her forward. Rachel slowly reached out, hypnotized by the lock's glow, as if something was resonating in her soul and pleaded with her to touch it. Her pale fingertips barely grazed the surface, but a single touch was enough to completely shatter the lock. It fell to the ground with a loud clunk. The archaeologist instinctively backed away as the lid popped open a crack, a thick cloud of dust pouring out.

Rachel coughed as she inhaled the musky hair, using her arm to cover her mouth and nose. The dust cloud, which reminded her of a fog, slowly cleared. The tomb was wide open, a heavily bandaged arm holding it steady. A figure slowly sat up inside the sarcophagus, heavily bandaged from head to toe. She wasn't one to believe in the dead being resurrected, but as she rose to her feet with unconsciously trembled legs, the impossible was seemingly more and more possible.

Rachel attempted to calm her rapidly beating heart down with observations, facts. Anything to ground her. The figure was definitely male, his frame still perfectly outlined depicted the many layers of wrappings. His ebony hair looked fluffy and silky smooth, as if he handed been risen from the dead. Finally, his eyes opened, revealing they were heterochromatic. One was a hazel brown and extremely dilated; the other was a piercing gold, illuminated even in the low light.

She watched at the...creature turned his head towards her. She slowly calmed herself down, curiosity overshadowing any sense of fear. She looked into his eyes, which bore confusion. Then she watched as his eyes widened the longer their eyes were locked. Beneath those layers of bandages, Rachel could hear a single word escape his foreign tongue.

"Rasella…?"

Who?

To be continued...

Also, HUGE shout out to @galacticpotatoes for sketching some beautiful art of this AU! Which you can find here!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Run Boy Run (This World Is Not Made For You) 1/2

Pairing: None here, platonic Logince in the next chapter.

Word Count: 2.012

Trigger warnings: Implied character death, nothing else that I can think of??

Notes: Here is the second part of my Atlantis AU, in which Logan is nothing like the original Milo Tatch and the museum's board of directors barely avoids getting murdered by an angry researcher, probably. (Also, I hurt myself writing the first part of this chapter. You're welcome.)

Read it On AO3! Previous Part Next part

“Dad?”

Startled, William looks up from his desk, eyes rimmed red with fatigue behind his glasses. He’s been working almost nonstop since morning, analyzing and translating photos of mysterious artefacts and old manuscripts over and over again. But the only thing he seems to have gotten out of it are a sore back and a mess of papers and documents that’ll be a pain in the arse to put back in order.

William immediately spots his son, his head peeking from behind the studio’s door. Smiling, he motions him closer, stretching his arms out to try and remove some of the muscle pain. Silently, Logan enters the room and shuts the door, before padding across the thick carpet covering the floor to his father’s side.

“Hey Lo,” his father murmurs, picking him up and gently placing him on his lap, “what’re you doing still up? I thought you had gone to bed a while ago.”

Still silent, Logan quietly scoots closer to his father’s chest, holding his teddy bear –Mr Crofters, a gift from his mother before she passed away- in his arms. “Couldn’t sleep,” he mumbles sleepily, barely biting back a yawn, “felt lonely.”

William sighs, leaning back into his chair. “Sorry kid,” he apologizes, idly combing a hand though his son’s hair, “I lost track of time. Papa’s got a lot of work to do.”

“It’s late though. Papa needs to sleep.” Logan protests, yawning. “You can do work tomorrow.”

“Just five more minutes.” Tries his father, thinking about all the material he still has to study and that old Norwegian shield with those strange inscription that might just be the final piece he needs to complete the puzzle –he’s so close, William knows it. He can’t stop now, not after all the sacrifices and closed doors he has had to endure in his life. He’ll show them, shove the proof right onto their faces if he needs to, he’ll prove that he had been right all along even if it kills him-

Logan grabs onto his arm, shaking his head. “That’s five minutes too long!” he complains, his face scrunched up into that stubborn pout that reminds William so much of Sherry- Logan’s mother, his partner, the one that had believed in him even when everybody else had decided to turn their back on him. “Sleep is important, you taught me that.”

Sighing, William throws one last, longing look at his papers, scattered messily on his desk. He knows his son and he’s aware that, at this point, the kid won’t give up until they’re both in bed, sleeping.

“Alright, alright you little rascal.” He finally concedes, shaking his head with a defeated smile on his face, “I swear you act so much like your mother it scares me sometimes.”

“What do you mean?”

Picking him up, William chuckles. “She had to barge into my studio almost every night, because I never paid attention to how late it was,” he explains, ruffling his son’s hair, “and if I tried to protest, she would literally pester me or even start dragging me out by force until I caved and agreed to go to sleep.”

“Really?!” Logan giggles, sleepiness momentarily forgotten, “can you tell me more about her?” he asks, almost tentatively.

William smiles, kissing his son’s head. “Of course, kiddo.” He murmurs, closing the studio’s door behind them.

(Later, when Logan is finally asleep in his bed with Mr Crofters firmly clutched in his hold, William finds himself staring at his son with a melancholic smile on his face. Sitting on the edge of the bed, he gingerly picks up an old frame from the nightstand. From the photo, his wife smiles at him, as beautiful as he remembers her to be.

“I’ll prove them all wrong, Sherry,” he promises, “just you wait.”)

“-and that is why I firmly believe it is our duty as men of science to do everything in our power to retrieve the Shepherd’s Journal and, finally, uncover the secret behind the myth of Atlantis and his mysterious power source.”

Silence falls, and Logan finally lets out a breath he hasn’t even realized he’s been holding. His stance relaxes, his shoulder slumping slightly, and he nods to himself. With a speech like this, only a fool would refuse his proposal.

Sadly, he’s very much aware of just how many fools are part of the museum’s board of directors.

Logan sighs, shaking his head in an attempt to clear it from those foolish thoughts –it doesn’t work, not completely, but he decides to ignore it. He has a presentation to give, an expedition to organize and a long lost civilisation to –hopefully- bring back to the light of day for everyone to see.

This time, Logan knows he’ll be able to convince the board. They asked for proof, for something that could really justify an expedition tasked with finding a place, until now, named only in legends and fairy tales. And he got it, the result of long nights spent researching facts, traducing old texts, and consulting his father’s notes and discoveries for new, interesting leads.

The only missing piece is the Shepherd’s Journal, buried somewhere on the southern coast of Iceland –not Ireland, as a very superficial translation had formerly stated. He often wonders how utterly stupid whoever originally deciphered it had had to be, to be able to confuse two letters so different like that.

However, that won’t be a problem for long. Once they finally manage to retrieve the Journal, it will be only a matter of time until they find Atlantis for good.

The phone suddenly rings, abruptly snapping Logan out of his thoughts. Groaning, he leans over the blackboard to grab the receiver, trying –and failing- to not get chalk on his shirt. “Cartography and Linguistics, Logan Sanders speaking. How may I be of help?”

On the other side of the line, an angry voice starts ranting –in a very crude and unnecessary manner, Logan notes while barely holding back an irritated sigh- about the absence of warm water and properly-working heating.

“Please remain in line for a few moments.” He answers, voice carefully neutral. Silently, Logan walks towards the boiler on the other side of the room and quickly turns a few valves, before hitting it with a nearby spanner.

“Is this more adequate?” he asks, grabbing the receiver once again. Logan listens quietly as whoever called yells at him some more, biting back a few choice words he would really like to share with them –he can’t get himself thrown out of the museum, not now that he’s so close to reaching his goal.

When they finally hang up, Logan puts back the receiver, barely containing his irritation. He’s a linguist, a researcher, probably one of the most intelligent and resourceful men this museum has to offer –and he’s not saying it out of vanity or narcissism. It’s a fact, a certainty, something as obvious as the colour of the sky or the presence of oxygen in the atmosphere.

He should not be stuck in a little office –if it could even be called one- in the basement of the museum, forced to spend all day answering angry calls about the absence of warm water in the rest of the building and taking care of an old and battered boiler. He deserves to do more, he wants to do more.

Hopefully, today he’ll finally be able to get out of there for good. One way or another.

Glancing at the clock on the wall, Logan starts picking up all the papers and documents piled up on his desk, mentally listing off what he needs as he goes. Once he’s sure he has everything necessary for his presentation –he checks everything twice, just to be sure- he nods, takes a steadying breath and turns around, ready to climb the stairs that will take him out of the basement.

However, before he can get out his eyes land on an old frame on his desk, his parents smiling widely at him from the photo. Logan’s gaze softens, and he finds himself picking up the frame with a little, sad smile on his face.

“Mom, dad,” he murmurs, bittersweet melancholy swimming in his voice, “I’ll make it this time, just you wait.”

Suddenly, a strange “whoosh” sound attracts his attention, his gaze snapping to the pneumatic tube in the corner. Logan grabs the capsule, a little irritated at whoever thought it was a good idea to send him a communication now that he has a presentation to give. Then, he reads the notice, and his blood immediately runs cold.

Dear Mr Sanders, this is to inform you that your meeting today has been moved up form 4:30 pm to 3:30 pm.

“What?”

He has barely managed to read the first notice, that another “whoosh” echoes in the otherwise silent basement. Logan is starting to have some idea of where this whole thing is going, and he doesn’t like it one bit. Slowly, he picks up the second capsule, hoping against hope to be wrong. But apparently, he’s not so lucky.

Dear Mr Sanders, due to your absence the board has voted to reject your proposal. Have a nice weekend, Mr Harcourt’s office.

Logan stares at the notice, eyes wide in disbelief. Then, surprise is replaced by anger, boiling in his veins like liquid fire.

“This is enough!”

“Mr Harcourt!” Logan calls, marching down the halls of the museum. The few people in the area are quick to step aside and let him pass, intimidated by the downright murderous expression on the young man’s face.

On the other side of the hall, Mr Harcourt visibly startles, eyes wide in surprise –it’s obvious he and the other members of the board thought they could get out of the museum before Logan could find any of them. He quickly pulls himself out of his shock tough, and doesn’t waste any time in bolting down the corridor towards the exit.

But Logan is a man on a mission, and he quickly reaches the man at the entrance of the museum, where a carriage is waiting for him –the fact that Mr Harcourt is actually quite short, and his quick pace is nothing compared to Logan’s long and rage-driven strides, helps quite a lot.

“Mr Harcourt!” Logan repeats, grabbing the door of the carriage to stop him from closing it, “I demand an explanation!”

Mr Harcourt sighs, clearly irritated. “Look Mr Sanders, this museum funds scientific expeditions based on facts, not legends and folklore.”

“Atlantis is not a legend!” Logan bristles, barely containing himself from grabbing the collar of the other man’s coat, “There is more than enough evidence to prove it! and if you would just listen to me-”

“Enough!” Mr Harcourt suddenly exclaims, interrupting Logan’s rant, “You have a lot of potential, Logan. Don’t throw it all away chasing fairy tales like your father did.”

At that Logan freezes, body completely still. Then, he suddenly relaxes, and when he looks at the other man once again his expression is unreadable, completely devoid of any emotion.

“If this is really what you think, then I won’t waste anymore of your time.” He says, reaching into his pocket and slapping an envelope on Mr Harcourt’s face.

“W-What is this?!” the man stammers.

“My letter of resignation.” Logan explains, voice neutral. “Since it appears none of you idiots have enough common sense to listen to a proposal sustained by facts and a meticulous research, there is no reason for me to stay here and continue to be your little slave down in the basement. If you won’t fund this expedition, I will find another way to retrieve the Journal.”

“You can’t be serious! You’ll flush your career down the toilet!” argues Mr Harcourt, clearly outraged. But Logan ignores him, slamming the carriage’s door shut.

“We’ll see who’ll have the last laugh, Mr Harcourt.” He replies, before turning around and leaving the museum once and for all.

He’ll find another way to get to Atlantis, come hell or high water.

Taglist: @keithkhoegane @ekkye @teacupfulofstarshine @tis-i-squid @i-really-dig-the-purple @shippernaturalsanderspjoandscifi @certifiedfangirlluna @rememberfateau-nowoffical @crownswriter123 @egg-achechris @noodlesforlife13

#sanders sides#atlantis au#royality#analogical#thomas sanders#logan sanders#roman sanders#the dragon witch#next chapter: Roman#our favourite Dramatic Boi#maxiswriting

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

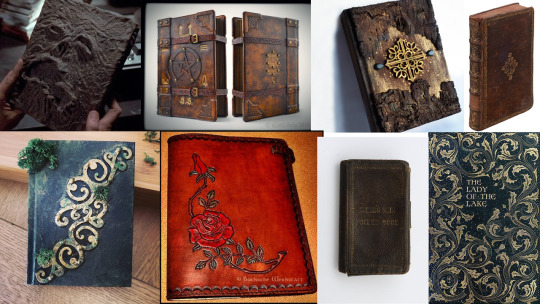

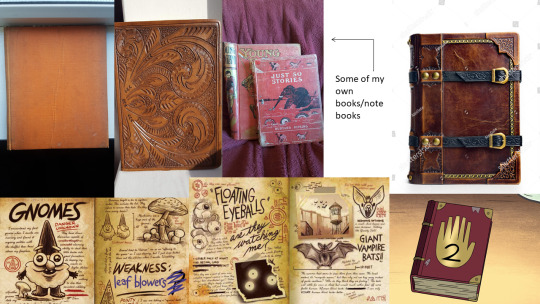

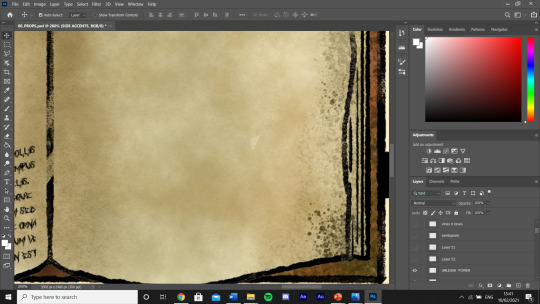

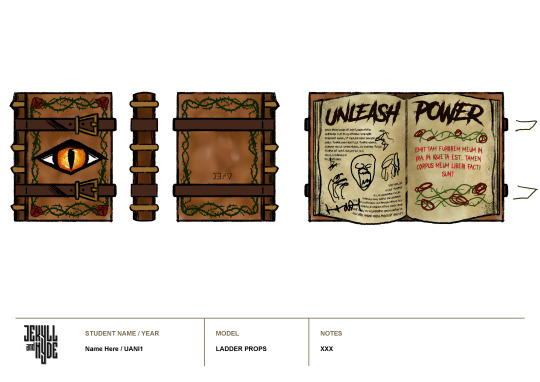

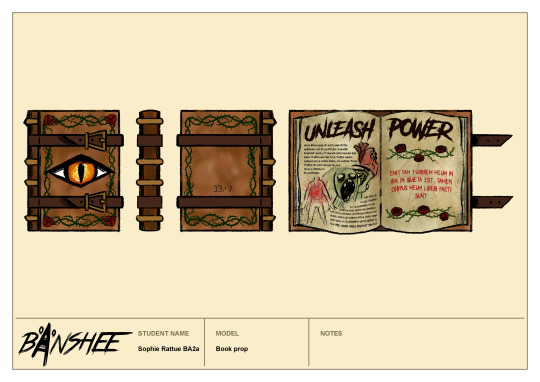

Creating the Book

Before sketching ideas, I did some research on books that could inspire the look of my design. This included the Necronomicon from The Evil Dead (1981), the journals from Gravity Falls (2012) and a pocketbook made from the skin of William Burke, an 1820′s murderer who sold corpses to surgeons for study (bottom right image in the first moodboard, next to The Lady of the Lake).

I’m really drawn to the examples bound with aged, brown leather; there is something that feels so historical and significant about the material compared to paper or cloth covers.

I also really like the idea of including buckles on the book- suggesting there is something inside you are forbidden to see, or something trying to get out.

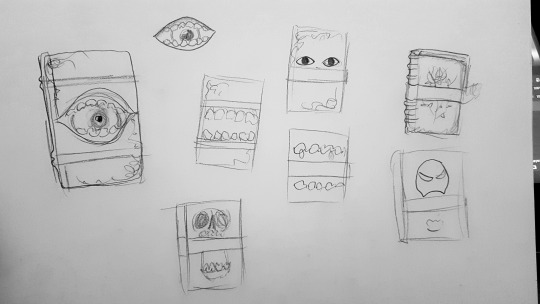

In my scriptwriting work, the book does something that alerts Mary’s attention, like flash with light or move slightly, so I need to include something on the cover that I could use to signal her with.

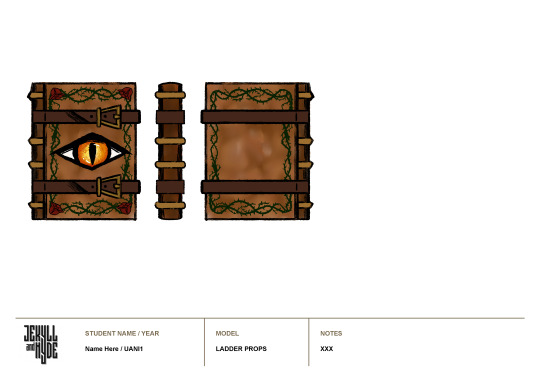

So, in these thumbnails I experimented with different covers- thinking maybe the moving jaw of a skull, gnashing mouth or a blinking eye would work well. I also played with the placement of the buckle, which was a little awkward because it needs to be either one in the middle (obscuring the cover art) or two at the top and bottom (forcing the cover art to take up a smaller amount of space. So, I decided 2 buckles would be my best option.

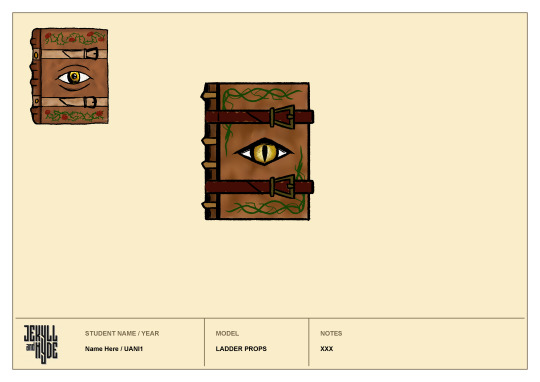

A blinking eye would have a real supernatural feel to it- like the book is living, almost like it is a character in of itself. Plus, it is such a subtle movement that I can believe not many other people would notice it. So, I decided to push this idea further:

As cool as the eyeball in a mouth looks, I don’t know if closing the mouth would read to the viewer as a blink. Plus, I think this is just one too many elements to try and fit on the cover, so I switched to a simple eye that looks like it has been embedded in the leather. Then I experimented with the placement of the vines- and decided it would work better around the edges of the book than surrounding the eye.

I liked the overall look of the top right iteration, but still felt like there was more I could do to refine the design. It didn’t feel ‘evil’ enough; the lines are too rounded and the colouring too light & cheerful. So, I began by re-drawing it in my chosen art style, with textured back lines. For the colouring, I used a mix of browns blended together with the smudge tool in Photoshop (eye-dropped from my moodboards) and followed this tutorial:

(by CGCookie (2012) Gold Step by Step tutorial, available at https://www.deviantart.com/cgcookie/art/Gold-Step-by-Step-tutorial-327175040 [acessed 10/01/21])

to give the eye a golden colour. Then, I darkened the spine to differentiate it from the cover and tried a deep red for the buckles. I think the darker buckles were a step in the right direction, but with the addition of red, I thought everything was starting too look too warm & saturated, and it was losing the ‘edge’ of my original idea.

I tried to remedy this by giving the eye a sharper form and recolouring the vines in black and the straps in brown. This did help in making it feel darker & more evil, but it still looked quite bland.

Then, I added a red hue to the eye and I feel like this immediately improved the design- giving it a more malicious feel. After that I added green vines again to try and alleviate the blandness, this time as a border. To me this looks much better, it frames the eye really nicely and I used a darker shade of green so that it doesn’t look too natural or comforting. Next, I added the roses, also in quite a dark shade and I think this was the finishing touch the book needed; they compliment the red of the eye and red undertones of the leather nicely and they mark out the corners of the cover, creating additional framing for the eye.

So, next I made the back & side views easily enough by copying and flipping what I’ve already drawn, and using guidelines to match up the bumps on the spine.

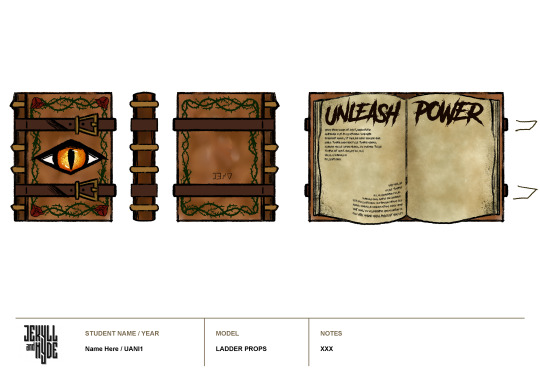

For the open position, I was heavily inspired by the journals from Gravity Falls- with their scrawling text and sketchy drawings. I began by referencing an open book, to see how the pages lie:

Then, I used a variety of textured brushes to fill in the page colour, blending them with the smudge tool and adding random speckles to the edge of the page to indicate fading or mould or water damage.

Once I had the blank pages, I then went back to the horror fonts I downloaded for making the logo and picked one called ‘Another Danger’ by The Branded Quotes on https://www.dafont.com/theme.php?cat=110. With this I added the ‘unleash power’ title and used lorem ipsum to fill out some small areas, leaving room for illustrations.

I think this font works really well, the title looks almost hand-drawn and it makes the smaller text look so much more complex- almost as if the letters are from a different alphabet.

Once again taking inspiration from Gravity falls, I then planned out some illustrations and added the inscription to the other side- framed by the rose and thorn vines in order to to carry the motif through the book.

Then, I cleaned up the vines, doodled a few scratchy drawings to fill the space between text and added a faded pentagram behind the inscription. And coloured the now unfastened straps.

Overall I am so pleased with my final result. I think gathering all of that research and iterating until I was completely satisfied has made this design feel really polished. I especially love the colour palette I ended up using- it has a warmth that I can see Mary finding enticing but it also has deep, blood reds and blacks, indicating its sinister power. I’m not sure where I would improve this, maybe the leather of the book looks a little bit blurry but I don’t think this is too much of an issue. I’ll be really interested to see what critique I receive in the next tutorial.

Next, I want to try and achieve this same level of polish with the pub sign- so I’ll gather loads of images for reference to start with.

0 notes

Text

Inscription: The Journal of Material Text - Theory, Practice, History

Contributor, with The Roland Barthes Reading Group, to issue 1 of Inscription, a new academic journal of the study of material texts.

The Roland Barthes Reading Group has been parsing Roland Barthes’s The Preparation of the Novel [Trans. Kate Briggs] for four years. His text repeatedly lays out the conditions for beginning without ever quite starting his novel project.

The Roland Barthes group include: Emma Bolland, Julia Calver, Helen Clarke, Louise Finney, Suzannah Gent, Sharon Kivland, Debbie Michaels, Hestia Peppé, and Rachel Smith.

Issue 1 features Rebecca Bullard, Catherine Clover, Michael Durrant, John T. Hamilton, Alexandra Franklin, Kathryn James, The Roland Barthes Reading Group, Serena Smith, Alice Wickenden, Jérémie Bennequin, Craig Saper with Ian Truelove, Erica Baum, Craig Dworkin, Sean Ashton.

0 notes

Text

Books On Books Collection - Inscription: The Journal of Material Text, Issue 5 (Containers)

View On WordPress

#Adam Smyth#Arnaud Esquerre#Aspen#Étienne Anheim#Beth Driscoll#Christian Bök#Claire Squires#Claude Closky#Daniel Buren#Daniel Jackson#Dennis Duncan#Elizabeth Haines#Erica Baum#Felicity Brown#Felipe Cussen#Gill Partington#Harold Offeh#James Misson#Jérémie Bennequin#Jean-Phillippe Échard#Jeremy Deller#Joanna Kavenna#Joel Swanson#Julie Park#Kiff Bamford#Kimsooja#Lora Angelova#Luc Boltanski#Lucy Razzall#Marie Radepont

0 notes

Text

In reality, the Atlantic coastal forest is a garden [...]. It is absurd. It is as if a glass divider separated, on one side, the experience of the fruition of life, and on the other, the place from which we originate. This division reveals another, more profound divorce: the idea that humans are different from everything that exists on earth. [...] The Amazon rainforest is a monument. A monument built over thousands of years. The ecology of that place in motion creates shapes, volumes -- disperses all that beauty. The Amazon rainforest, the Atlantic coastal forest, the Serra do Mar, the Takrukkrak are monuments that have, for us, the power to open a portal that accesses other visions of the world. The forest provides this. And yet, despite its materiality -- its body that can be felled, uprooted as wood -- the forest is not seen. In Brazil, there are cities that UNESCO has declared the cultural patrimony of humanity. Meanwhile, we destroy the Atlantic coastal forest, the Amazon rainforest. It’s a game of illusion. The fact that we live in the region of the world where it is still possible to sprout people from within the forest is magic. There are people who look at this as a type of delay in relation to the globalized world: “We should already have civilized everyone.” But it is not a delay, it is a magic possibility! [...]

In the spring, a season they loved, the Botocudos ascended along the Doce River to the steep slopes of the Espinhaço Mountains [...]. The culmination of the period is September 22, when the sky is very high and the seasons pass from winter into spring. The mountains bloom, it’s beautiful. The Botocudo families, having come from different hillsides, from the Serra da Piedade, traveled to the Espinhaço to experience this cycle deeply. There is a lot of inscription about this engraved on rocks throughout that entire region. Have you ever noticed, on the slopes of Conceição do Mato Dentro, how wonderful the Tabuleiro waterfall is? The slopes of the Tabuleiro are a tremendous library! Once I stopped there to watch the sunset, until it grew dark. I stayed looking at the different stories on those slopes. It is the history of the passage of our ancestors through those sites some thousands of years ago, as archeological studies have already confirmed. [...] Our history is interlaced with the history of the world. But the country throws away this history. People who travel to these places drive pickaxes into the boulders [...]. Each fragment, each piece that they pull up from those rocks is as if they ripped out a page or stole a book from the library.

---

All text above are the words of: Ailton Krenak. As published by Ailton Krenak and Mauricio Meirelles. “Our Worlds Are at War.” e-flux Journal Issue #110. June 2020. As described by e-flux: “The following testimony by Ailton Krenak, a longtime Indigenous activist and intellectual in Brazil, was originally published in the December 2019 issue of the Brazilian magazine Olympia: Literatura e Arte. The testimony was related orally to Jose Eduardo Goncalves and Mauricio Meirelles, and then transcribed.”

#ecologies#multispecies#indigenous#indigenous pedagogies#tidalectics#ecology#black methodologies#abolition

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

#7 Research Proposal

Objects of Desire Research Proposal

My object of desire is the Replica Islamic Astrolabe, accession number: DUROM.2017.323

Initial Description of Object

It is a replica Astrolabe created by ‘Hemisferium’, a specialist manufacturer in antique scientific instruments. It is based on an original piece by Diya’al Din Muhammad, who was part of a predominant family of astronomical instrument makers from Lahore.[1] The original piece was created in Lahore, Pakistan in 1647 whilst the replica was made in Madrid, Spain around 2016/17. The replica astrolabe is 180 mm (height) X 6mm (depth) X 120mm (width).

The astrolabe is an astronomical instrument made from cast metal which was originally used to measure angles, the altitude from the horizon to the celestial space, and for navigation purposes by helping to identify constellations to determine your location and the direction you were heading. Although, some Astrolabe specialists argue it has hundreds of uses.

Context

This concept was integrated into the Islamic faith when they inherited texts and technology from the Greeks, as they were going to be destroyed by the Christians who saw the technology as heathen. The navigational concept of astrolabes was adopted into the Islamic faith to help Muslims find the Qibla, the direction of Mecca, especially whilst they were travelling.

This piece isn’t simply a scientific instrument, but also a masterpiece of art and design with intricate carvings on the ‘rete’, the decorative netting overlay, which is designed with Arabic and Latin script and numbers which encapsulates the Greek and Islamic cultures its evolved from.

Rationale for Choice

I wanted to choose an object which stood out to me, or ‘spoke’ to me in a way. I have always had a fascination with celestial space – galaxies, nebulas, the solar system. One of my Art & Design A Level projects centred on this topic and I have always been curious of how outer space has been used for scientific purposes through the decades and in different cultures. As an English Literature student, I have not had the opportunity to learn about such scientific objects and their historical importance, and I thought this project would be a great opportunity to explore that intrigue. Equally, the Islamic culture and region of the Islamic Republic, where the original Astrolabe originates from, is an area I have not investigated in great depth and I feel this project will help open up a dominate area of worldly culture which is missing from my knowledge.

Contact with the Oriental Museum & Review of Existing Information:

I contacted Gillian Ramsay following our trip to the Oriental museum as she was the curator who originally purchased the replica astrolabe for the collection. We met in mid November and she was very helpful in sharing her knowledge of the object and subject area. She provided me with the museum’s material on the specific object which consisted of the dimensions, a brief description of the piece, details of its production, and materials used and how much it cost. As it is a replica it does not have a large paper trail of former owners or donors, but I believe it provides a unique opportunity to explore how and why it has remained an ‘object of desire’ for so many centuries and why are replicas still being produced.

The lack of direct material on the object I feel opens up a world of opportunity to explore the development of the astrolabe from its original concept in the Greek world and then to its use in the Islamic world. I also feel there is a great area for exploration amongst the original craftsman, Diya’al Din Muhammad, and his family and the seminal pieces they created that are still being replicated.

Research Questions:

I feel a central debate for my project is whether a replica can still hold the same value as an object of desire compared to an original piece?

Equally, whether the astrolabe has lost value when it is now being mostly used as an aesthetic piece rather than one of a functional purpose as a scientific instrument?

Questions surrounding the Astrolabe as a reference piece into the ancient Greek world, where it was first created, and whether it can shine light on to this culture and the importance they place on exploring the universe?

Exploration into how the Islamic culture utilised scientific objects to support their religion when Christian based religions rejected them.

Questions surrounding the evolution of pieces due to transferring cultures could be posed. The astrolabe was originally a scientific instrument developed by the Greeks and was adopted by the Islamic world who expanded its potential use through further scientific research. I feel it would be insightful to explore into this adoption of objects into other cultures and what implications does this have for the development of the object and the cultures?

Reflective Analysis

I think the first natural obstacle is that it is a replica, not an original piece. This means it does not have a personal story attached to it or a donor. I hope to counter this issue by contacting the replica manufacturer ‘Hemisferium’ to understand why they feel there is a demand for replicas of these pieces and to explore the questions of replica vs original and whether they hold equal value.

I hope to also explore the original manufacturing company from Lahore to see where the original piece is located and if it had an intended owner. Equally if the manufactures have any personal anecdotes and explore what their production line meant to their family as it remained as a generational business.

It is an intricate piece of science and I feel the first hurdle will be understanding how it works. I hope to consult scientific material and the Astrolabe specialist at the Oxford museum to understand how it actually functions.

Although, there is not a great deal of information on my specific item, there is an abundance of material on Astrolabes in general which makes the topic quite broad. I will tackle this challenge by being highly selective of what is explicitly relevant to my object of desire and the questions I want to answer, as outlined above.

Literature Review

Durham’s physical library came up short but their ‘discover’ link to online documents was highly fruitful.

- I have explored the general descriptions of Astrolabes and their evolution and purpose from: The Oxford History of Science Museum, The British Museum, The University of Hawaii’s, Institute for Astronomy, and the Smithsonian magazine, Oxford Art online.

Constanze Hampp & Stephan Schwan (2015) The Role of Authentic Objects in Museums of the History of Science and Technology: Findings from a visitor study, International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 5:2, 161-181.

Eagleton, C. (2019). What Were Portable Astronomical Instruments Used for in Late-Medieval England, and How Much Were They Actually Carried Around? In J. Nall, L. Taub, & F. Willmoth (Eds.), The Whipple Museum of the History of Science: Objects and Investigations, to Celebrate the 75th Anniversary of R. S. Whipple's Gift to the University of Cambridge (pp. 33-54). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108633628.003 https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/whipple-museum-of-the-history-of-science/72EAE4248EBCB8CA20DFFA3D1264557D

F., J. The Astrolabes of the World: based upon the Series of Instruments in the Lewis Evans Collection in the Old Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, with Notes on Astrolabes in the Collections of the British Museum, Science Museum, Sir J Findlay, Mr S V Hoffman, the Mensing Collection, and in other Public and Private Collections . Nature 131 https://www.nature.com/articles/131819a0#citeas

Falk, Seb. “Sacred Astronomy? Beyond the Stars on a Whipple Astrolabe.” The Whipple Museum of the History of Science: Objects and Investigations, to Celebrate the 75th Anniversary of R. S. Whipple's Gift to the University of Cambridge, edited by Joshua Nall et al., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2019, pp. 11–32.

Hoskin, Michael, ‘Astronomy in the Middle Ages’, The History of Astronomy: A Very short introduction, Oxford University Press, 2003. https://www.veryshortintroductions.com/view/10.1093/actrade/9780192803061.001.0001/actrade-9780192803061-chapter-3

Huggins, M. L., ‘The astrolabe. II. History’, Popular Astronomy, Vol. 2, pp.261-266 http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu//full/1895PA......2..261H/0000261.000.html

Jeffs, P. Science in culture: A culture of knowledge. Nature 439, 536 (2006) https://www-nature-com.ezphost.dur.ac.uk/articles/439536b

Latham, Marcia. “The Astrolabe.” The American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 24, no. 4, 1917, pp. 162–168. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2973089.

M.R. Brett‐Crowther (2010) ‘Science & Islam: A History’, International Journal of Environmental Studies, 67:1, 111-114. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00207230903208407

Rodríguez-Arribas, Josefina, ‘Astrolabes in Medieval Encounters’, Medieval Encounters, September 2017, Vol.23(1-5) https://brill.com/view/journals/me/23/1-5/article-p1_1.xml?lang=en

Safiai, Mohd Hafiz, ‘Astrolabe As Portal To The Universe, Inventions Across Civilizations’, International Journal of Civil Engineering and Technology (IJCIET), Volume 8, Issue 11, November 2017, pp. 609–619 https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3f06/c9eab107851daaef4f5ac6c371c807fe94b4.pdf

Sarma, Sreeramula Rajeswara, “The Lahore Family Of Astrolabists And Their Ouvrage.” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, vol. 55, 1994, pp. 287–302., www.jstor.org/stable/44143367. (To investigation into the original designer, Diya’al Din Muhammad, and his family is essential as they highly regarded astrolabe makers.)

Vafea, Flora. "From the Celestial Globe to the Astrolabe Transferring Celestial Motion onto the Plane of the Astrolabe". Medieval Encounters 23.1-5: 124-148. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700674-12342245

Ward, Rachel, “The Inscription on the Astrolabe by ʿAbd Al-Karim in the British Museum.” Muqarnas, vol. 21, 2004 - (To analyse how Astrolabes are depicted and investigated)

Further Sources:

Gillian Ramsay alerted me to the Oxford History of Science Museum collection. On investigation I found they have the ‘world’s largest collection of astrolabes’ and another astrolabe by Diya’al Din Muhammad. I also discovered that there is an incredible colossal astrolabe in the Albukhary Gallery in the British Museum. I have consulted both of their collections and online material, and I will be in contact with their curators for more in-depth questions I have on the topic such as: Why the curators feel such objects hold importance in the education of Islam and scientific development.

I also hope to visit both collections in Epiphany term if possible so I can compare their specific details to my Astrolabe as the designs, notably on the rete, are typically different on each which provides a personal and beautiful aesthetic quality to the object.

11/12/2019

0 notes

Photo

Final day of exploring started with sharing some Fika with a feathered friend. I journaled for a bit, enjoyed a coffee and planned my last day in Stockholm.

Then I met up with Peace who TWO BOOKS out this year. Check it out!

Peace and I went for to the Nobel Prize Museum. The museum features, no surprise, information about those who are previous Nobel Prize winners. During our visit there was an exhibit on Martin Luther King Jr. in addition to the permanent exhibits.

In the gift shop they also had these buttons to support ican, Nobel Peace Prize winner from 2017. Upon receiving the award Beatrice Finn stated:

"Nuclear weapons, like chemical weapons, biological weapons, cluster munitions and land mines before them, are now illegal. Their existence is immoral. Their abolishment is in our hands.

The end is inevitable. But will that end be the end of nuclear weapons or the end of us? We must choose one.

We are a movement for rationality. For democracy. For freedom from fear.

We are campaigners from 468 organisations who are working to safeguard the future, and we are representative of the moral majority: the billions of people who choose life over death, who together will see the end of nuclear weapons."

Switching gears, after visiting the museum with Peace it was lunch time.

We decided to find something to eat at Mariatorget square, a lovely park with a massive water fountain. While I definitely enjoyed very fancy vegan food (see previous post) I’m not above grabbing a slice of fast food vegan pizza from a 7-Eleven which is what I decided to do. I didn’t end up trying it but check out the cute little ice cream shop StikkiNikki’s! The have a bunch of vegan options.

And one more bit of site-seeing! Have you ever heard of a rune stone? I hadn’t.

About the rune stone:

THE VIKING RUNESTONE EMBEDDED ON a street corner in Gamla stan, the old town of Stockholm, is believed to be older than the city itself. Though its origin is unknown, it’s estimated to date back nearly a millennia, to the 11th century.

Officially called “Uppland Runic Inscription 53,” the Gamla stan stone is prominently located at the intersection of Prästgatan and Kåkbrinken streets, but can be hard to spot without a guide as there are no signs or plaques pointing out its significance. It’s about waist height behind the street corner post.

The stone depicts a serpent body in decorative winding loops, and an inscription that has been partially translated as “Torsten and Frögunn had the stone erected after their son.” The name of the son is sadly lost. The female name, Frögunn, is a known pagan name, which lent a clue as to the origin of the text. It’s believed the stone was brought into Gamla stan from a neighboring area to be used as construction material.

0 notes

Text

Rolf Loeber & Magda Loeber, with Anne Mullin Burnham, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006), cxv, 1,489pp., ill.

During much of the nineteenth century the majority of the population was Irish-speaking and illiterate. The production of new works of fiction (in contrast to poetry) in the Irish language was virtually nonexistent, and remained so through much of the nineteenth century. As Denvir states, ‘Most of the prose written [in Irish] in the nineteenth century is a continuation of the scribal activity of copying [our emphasis] earlier texts.’ [36] John Bernard Trotter complained in 1812 that ‘Books in Irish are not to be had.’ [37] Chronicling the history of earlier literature, Leerssen remarked that ‘Until the end of the nineteenth century, literary dissemination [of Irish literature] had been either oral, or else in scribal manuscripts only.’ [38] Thus, despite the majority status of Irish speakers, prose fiction in the Irish literary tradition remained frozen outside of print culture, its manuscripts were in private hands and not represented in publicly-accessible libraries. [39] Only in the public sphere of social gatherings of the peasantry were manuscripts read aloud. Their contents also remained disconnected from English literature because, as Cronin remarked, of the striking ‘paucity of printed translations [from the English or other languages] into Irish. [40]