#Indigenous Epistemologies

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cognition Enclosed: Agency, Attention, and the Architecture of Thought in the Age of Algorithmic Capture

We often think of our thoughts as ours. Photo by Google DeepMind on Pexels.com As private, sovereign, and untouched. But what if that’s no longer true? What if, without realising it, the architecture of our minds has been quietly reshaped by the apps we open first thing in the morning, the feeds that anticipate our desires, the notifications that punctuate our days? I wrote this piece not just…

View On WordPress

#algorithmic governance#Algorithmic Manipulation#anattā#Attention Economy#autonomy#Behavioral Design#Bernard Stiegler#Biopolitics#Buddhist philosophy#capitalism#cognition#Cognitive Capitalism#Cognitive Enclosure#Consciousness Studies#critical theory#Digital Culture#Digital Sociology#epistemology#fight capitalism#Foucault#Human-Computer Interaction#Indigenous Epistemologies#Memory and Technology#Mind and Technology#Neuroplasticity#nirvāṇa#Philosophy#philosophy of mind#Political Philosophy#Raffaello Palandri

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Philosophy of Shinto

Shinto, often referred to as "the way of the gods," is the indigenous spirituality of Japan. Unlike many Western religions, Shinto does not have a single founder, sacred texts, or a formalized set of doctrines. Instead, it is characterized by a reverence for nature, the worship of kami (spirits or deities), and practices that emphasize purification and rituals. Here’s an exploration of the key principles and ideas within the philosophy of Shinto:

1. Reverence for Nature

Nature as Sacred: In Shinto, nature is considered sacred and imbued with spiritual significance. Mountains, rivers, trees, rocks, and other natural features are often seen as manifestations of kami.

Harmony with Nature: Living in harmony with nature is a central tenet. This involves respecting and protecting the natural environment, recognizing it as the dwelling place of the kami.

2. Kami (Spirits or Deities)

Multiplicity of Kami: Shinto recognizes a vast number of kami, which can be spirits of natural objects, ancestors, or deified historical figures. Kami are not all-powerful gods but rather spirits with specific roles and localities.

Interconnection with Kami: The relationship between humans and kami is one of mutual respect and care. People perform rituals and offer prayers to kami to seek their blessings, protection, and guidance.

3. Ritual Purification

Purification Practices: Purification, or misogi, is a fundamental aspect of Shinto. It involves cleansing oneself of impurities and pollutants to maintain spiritual and physical purity. This can be done through washing, rituals, or even symbolic acts.

Rituals and Festivals: Shinto rituals and festivals (matsuri) are numerous and diverse, often held at shrines dedicated to various kami. These ceremonies reinforce the connection between the community and the kami, celebrating seasonal changes, agricultural cycles, and significant life events.

4. Shrines and Sacred Spaces

Shinto Shrines: Shrines, or jinja, are the focal points of Shinto worship. They are considered the homes of the kami and are places where people can go to offer prayers, perform rituals, and seek blessings.

Torii Gates: The iconic torii gates mark the entrance to sacred spaces, symbolizing the transition from the mundane to the sacred. Passing through a torii gate signifies entering a space where the kami dwell.

5. Ancestral Worship

Respect for Ancestors: Ancestral worship is an important component of Shinto. Families honor their ancestors through rituals and offerings, believing that deceased family members continue to influence and protect the living.

Continuity and Connection: This practice underscores the continuity of life and the interconnectedness of generations. Ancestors are seen as integral to the family's ongoing spiritual wellbeing.

6. Syncretism with Other Beliefs

Integration with Buddhism: Shinto has historically coexisted and intertwined with Buddhism in Japan. Many Japanese people practice both religions, incorporating elements of each into their daily lives and rituals.

Adaptability: Shinto’s flexibility and lack of rigid doctrines allow it to integrate other spiritual and philosophical traditions, adapting to the evolving cultural landscape.

The philosophy of Shinto offers a unique perspective on spirituality that is deeply intertwined with nature, community, and the reverence for life’s sacred aspects. It emphasizes living in harmony with the natural world, maintaining purity through rituals, honoring the kami and ancestors, and celebrating the cyclical nature of life. Shinto’s adaptability and integration with other traditions highlight its enduring relevance in contemporary Japanese culture.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#education#chatgpt#Shinto#Philosophy Of Shinto#Kami#Nature Worship#Ritual Purification#Shinto Shrines#Ancestral Worship#Japanese Spirituality#Torii Gates#Misogi#Matsuri#Spiritual Traditions#Indigenous Beliefs#Syncretism#Cultural Heritage

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Robert E. Bartholomew

Published: Apr 30, 2025

“It is fundamental in science that no knowledge is protected from challenge. … Knowledge that requires protection is belief, not science.” —Peter Winsley

There is growing international concern over erosion of objectivity in both education and research. When political and social agendas enter the scientific domain there is a danger that they may override evidence-based inquiry and compromise the core principles of science. A key component of the scientific process is an inherent skeptical willingness to challenge assumptions. When that foundation is replaced by a fear of causing offense or conforming to popular trends, what was science becomes mere pseudoscientific propaganda employed for the purpose of reinforcing ideology.

When Europeans formally colonized New Zealand in 1840 with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the culture of the indigenous Māori people was widely disparaged and their being viewed an inferior race. One year earlier historian John Ward described Māori as having “the intellect of children” who were living in an immature society that called out for the guiding hand of British civilization.1 The recognition of Māori as fully human, with rights, dignity, and a rich culture worthy of respect, represents a seismic shift from the 19th century attitudes that permeated New Zealand and much of the Western world, and that were used to justify the European subjugation of indigenous peoples.

Since the 1970s, Māori society has experienced a cultural Renaissance with a renewed appreciation of the language, art, and literature of the first people to settle Aotearoa—“the land of the long white cloud.” While speaking Māori was once banned in public schools, it is now thriving and is an official language of the country. Learning about Māori culture is an integral part of the education system that emphasizes that it is a treasure (taonga) that must be treated with reverence. Māori knowledge often holds great spiritual significance and should be respected. Like all indigenous knowledge, it contains valuable wisdom obtained over millennia, and while it contains some ideas that can be tested and replicated, it is not the same as science.

For example, Māori knowledge encompasses traditional methods for rendering poisonous karaka berries safe for consumption. Science, on the other hand, focuses on how and why things happen, like why karaka berries are poisonous and how the poison can be removed.2 The job of science is to describe the workings of the natural world in ways that are testable and repeatable, so that claims can be checked against empirical evidence—data gathered from experiments or observations. That does not mean we should discount the significance of indigenous knowledge—but these two systems of looking at the world operate in different domains. As much as indigenous knowledge deserves our respect, we should not become so enamoured with it that we give it the same weight as scientific knowledge.

The Māori Knowledge Debate

In recent years the government of New Zealand has given special treatment to indigenous knowledge. The issue came to a head in 2021, when a group of prominent academics published a letter expressing concern that giving indigenous knowledge parity with science could undermine the integrity of the country’s science education. The seven professors who signed the letter were subjected to a national inquisition. There were public attacks by their own colleagues and an investigation by the New Zealand Royal Society on whether to expel members who had signed the letter.3

Ironically, part of the reason for the Society’s existence is to promote science. At its core is the issue of whether “Māori ancient wisdom” should be given equal status in the curriculum with science, which is the official government position.4 This situation has resulted in tension in the halls of academia, where many believe that the pendulum has now swung to another extreme. Frustration and unease permeate university campuses as professors and students alike walk on eggshells, afraid to broach the subject for fear of being branded racist and anti-Māori, or subjected to personal attacks or harassment campaigns.

The Lunar Calendar

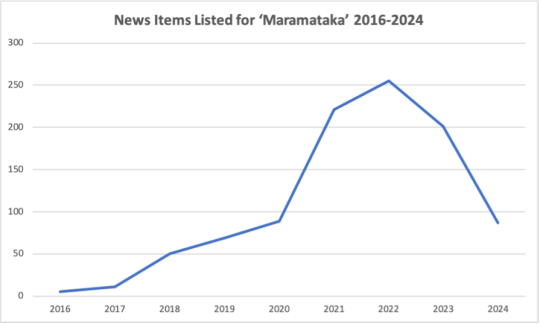

Infatuation with indigenous knowledge and the fear of criticising claims surrounding it has infiltrated many of the country’s key institutions, from the health and education systems to the mainstream media. The result has been a proliferation of pseudoscience. There is no better example of just how extreme the situation has become than the craze over the Māori Lunar Calendar. Its rise is a direct result of what can happen when political activism enters the scientific arena and affects policymaking. Interest in the Calendar began to gain traction in late 2017.

[ An example of the Maramataka Māori lunar calendar ]

Since then, many Kiwis have been led to believe that it can impact everything from horticulture to health to human behavior. The problem is that the science is lacking, but because of the ugly history of the mistreatment of the Māori people, public institutions are afraid to criticize or even take issue anything to do with Māori culture. Consider, for example, media coverage. Between 2020 and 2024, there were no less than 853 articles that mention “maramataka”—the Māori word for the Calendar which translates to “the turning of the moon.” After reading through each text, I was unable to identify a single skeptical article.5 Many openly gush about the wonders of the Calendar, and gave no hint that it has little scientific backing.

[ Based on the Dow Jones Factiva Database ]

The Calendar once played an important role in Māori life, tracking the seasons. Its main purpose was to inform fishing, hunting, and horticultural activities. There is some truth in the use of specific phases or cycles to time harvesting practices. For instance, some fish are more active or abundant during certain fluctuations of the tides, which in turn are influenced by the moon’s gravitational pull. Two studies have shown a slight increase in fish catch using the Calendar.6 However, there is no support for the belief that lunar phases influence human health and behavior, plant growth, or the weather. Despite this, government ministries began providing online materials that feature an array of claims about the moon’s impact on human affairs. Fearful of causing offense by publicly criticizing Māori knowledge, the scientific position was usually nowhere to be found.

Soon primary and secondary schools began holding workshops to familiarize staff with the Calendar and how to teach it. These materials were confusing for students and teachers alike because most were breathtakingly uncritical and there was an implication that it was all backed by science. Before long, teachers began consulting the maramataka to determine which days were best to conduct assessments, which days were optimal for sporting activities, and which days were aligned with “calmer activities at times of lower energy phases.” Others used it to predict days when problem students were more likely to misbehave.7

As one primary teacher observed: “If it’s a low energy day, I might not test that week. We’ll do meditation, mirimiri (massage). I slowly build their learning up, and by the time of high energy days we know the kids will be energetic. You’re not fighting with the children, it’s a win-win, for both the children and myself. Your outcomes are better.”8 The link between the Calendar and human behavior was even promoted by one of the country’s largest education unions.9 Some teachers and government officials began scheduling meetings on days deemed less likely to trigger conflict,10 while some media outlets began publishing what were essentially horoscopes under the guise of ‘ancient Māori knowledge.’11

The Calendar also gained widespread popularity among the public as many Kiwis began using online apps and visiting the homepages of maramataka enthusiasts to guide their daily activities. In 2022, a Māori psychiatrist published a popular book on how to navigate the fluctuating energy levels of Hina—the moon goddess. In Wawata Moon Dreaming, Dr. Hinemoa Elder advises that during the Tamatea Kai-ariki phase people should: “Be wary of destructive energies,”12 while the Māwharu phase is said to be a time of “female sexual energy … and great sex.”13 Elder is one of many “maramataka whisperers” who have popped up across the country.

By early 2025, the Facebook page “Maramataka Māori” had 58,000 followers,14 while another, “Living by the Stars” on Māori Astronomy had 103,000 admirers.15 Another popular book, Living by the Moon, also asserts that lunar phases can affect a person’s energy levels and behavior. We are told that the Whiro phase (new moon) is associated with troublemaking. It even won awards for best educational book and best Māori language resource.16 In 2023, Māori politician Hana Maipi-Clarke, who has written her own book on the Calendar, stood up in Parliament and declared that the maramataka could foretell the weather.17

A Public Health Menace

Several public health clinics have encouraged their staff to use the Calendar to navigate “high energy” and “low energy” days and help clients apply it to their lives. As a result of the positive portrayal of the Calendar in the Kiwi media and government websites, there are cases of people discontinuing their medication for bipolar disorder and managing contraception with the Calendar.18 In February 2025, the government-funded Māori health organization, Te Rau Ora, released an app that allows people to enhance their physical and mental health by following the maramataka to track their mauri (vital life force).

While Te Rau Ora claims that it uses “evidence-based resources,” there is no evidence that mauri exists, or that following the phases of the moon directly affects health and well-being. Mauri is the Māori concept of a life force—or vital energy—that is believed to exist in all living beings and inanimate objects. The existence of a “life force” was once the subject of debate in the scientific community and was known as “vitalism,” but no longer has any scientific standing.19 Despite this, one of app developers, clinical psychologist Dr. Andre McLachlan, has called for widespread use of the app.20 Some people are adamant that following the Calendar has transformed their lives, and this is certainly possible given the belief in its spiritual significance. However, the impact would not be from the influence of the Moon, but through the power of expectation and the placebo effect.

No Science Allowed

While researching my book, The Science of the Māori Lunar Calendar, I was repeatedly told by Māori scholars that it was inappropriate to write on this topic without first obtaining permission from the Māori community. They also raised the issue of “Māori data sovereignty”—the right of Māori to have control over their own data, including who has access to it and what it can be used for. They expressed disgust that I was using “Western colonial science” to validate (or invalidate) the Calendar.

This is a reminder of just how extreme attempts to protect indigenous knowledge have become in New Zealand. It is a dangerous world where subjective truths are given equal standing with science under the guise of relativism, blurring the line between fact and fiction. It is a world where group identity and indigenous rights are often given priority over empirical evidence. The assertion that forms of “ancient knowledge” such as the Calendar, cannot be subjected to scientific scrutiny as it has protected cultural status, undermines the very foundations of scientific inquiry. The expectation that indigenous representatives must serve as gatekeepers who must give their consent before someone can engage in research on certain topics is troubling. The notion that only indigenous people can decide which topics are acceptable to research undermines intellectual freedom and stifles academic inquiry.

While indigenous knowledge deserves our respect, its uncritical introduction into New Zealand schools and health institutions is worrisome and should serve as a warning to other countries. When cultural beliefs are given parity with science, it jeopardizes public trust in scientific institutions and can foster misinformation, especially in areas such as public health, where the stakes are especially high.

#Maramataka Māori#Maramataka#indigenous knowledge#Māori lunar calendar#pseudoscience#what science is#science#indigenous wisdom#other ways of knowing#epistemology#ways of knowing#mauri#objective reality#objectivity#Western colonial science#religion is a mental illness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love working in the science library because I'll be writing my silly little anthropology chapter about how the ontological turn is kind of doing structural-functionalism again but with more self-righteousness and I'll glance at the person working next to me and they're comprehending some kind of grotesque cylinder with a billion writhing equations attached to it. Sorry that's happening to you. Would you like to hear about my personal dislike for Martin Holbraad

#uni adventures#fyi: i like his analysis of the way anthropological theory works wrt conceptualisation. i just think 'solving epistemological problems' is#stupid way to put it#and in any case nothing he does is half as radical as he seems to think it is#'thinks suggesting that we need to respect indigenous thought makes you a revolutionary' is the no.1 most annoying trait#for an anthropologist to have

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Braiding Sweetgrass" by Robin Wall Kimmerer (p. 345 - 347)

#philosophy#political philosophy#indigenous#native american#environmentalism#philosophy of science#science#epistemology#braiding sweetgrass#robin wall kimmerer

0 notes

Text

youtube

#Youtube#documentary#cosmology#lgbtqia#native american#anthropology#epistemology#2 spirit#indigenous#culture

0 notes

Note

genq what are the actual reasons that plagiarism is bad apart from profit and prestige?

so there are two main angles i usually think of here, which ultimately converge into some related issues in public discourse and knowledge production.

firstly, plagiarism should not just be understood as a violation one individual perpetuates against another; it has a larger role in processes of epistemological violence and suppression of certain people's arguments, ideas, and labour. consider the following three examples of plagiarism that is not at all counter to current structures of knowledge production, but rather undergirds them:

in colonial expeditions and encounters from roughly the 14th century onward, a repeated and common practice among european explorer-naturalists was to rely on indigenous people's knowledge of botany, geography, natural history, and so forth, but to then go on to publish this knowledge in their own native tongues (meaning most of the indigenous people they had learned from could not access, read, or respond to such publications), with little, vague, or no attribution to their correspondents, guides, hosts, &c. (many many examples; allison bigelow's 'mining language' discusses this in 16th and 17th century american mining, with a linguistic analysis foregrounded)

throughout the renaissance and early modern period, in contexts where european women were generally not welcome to seek university education, it was nonetheless common practice for men of science to rely on their wives, sisters, and other family members not just to keep house, but also to contribute to their scientific work as research assistants, translators, fund-raisers, &c. attribution practices varied but it is very commonly the case that when (if ever) historians revisit the biographies of famous men of science, they discover women around these men who were actively contributing to their intellectual work, to an extent previously unknown or downplayed (off the top of my head, marie-anne lavoisier; emma darwin; caroline herschel; rosalie lamarck; mileva marić-einstein...)

it is standard practice today for university professors to run labs where their research assistants are grad students and postdocs; to rely on grad students, undergrads, and postdocs to contribute to book projects and papers; and so forth. again, attribution varies, but generally speaking the credit for academic work goes to the faculty member at the head of the project, maybe with a few research assistants credited secondarily, and the rest of the lab / department / project uncredited or vaguely thanked in the acknowledgments.

in all of these cases, you can see how plagiarism is perpetuated by pre-existing inequities and structures of exploitation, and in turn helps perpetuate those structures by continuing to discursively erase the existence of people made socially marginal in the process of knowledge production. so, what's at stake here is more than just the specific individuals whose work has been presented as someone else's discovery (though of course this is unjust already!); it's also the structural factors that make academic and intellectual discourse an élite, exclusive activity that most people are barred from participating in. a critique of plagiarism therefore needs to move beyond the idea that a number of wronged individuals ought to be credited for their ideas (though again, they should be) and instead turn to the structures that create positions of epistemological authority under the aegis of capitalist entities: universities, legacy as well as new media outlets, and so forth. the issue here is the positions of prestige themselves, regardless of who holds them; they are, definitionally, not instruments of justice or open discourse.

secondly, there's the effect plagiarism has on public discourse and the dissemination of knowledge. this is an issue because plagiarism by definition obscures the circulation and origin of ideas, as well as a full understanding of the labour process that produces knowledge. you can see in the above examples how the attribution of other people's ideas as your own works to turn you into a mythologised sort of lone genius figure, whose role is now to spread your brilliance unidirectionally to the masses. as a result, the vast majority of people are now doubly shut out of any public discourse or debate, except as passive recipients of articles, posts, &c. you can't trace claims easily, you don't see the vast number of people who actually contribute to any given idea, and this all works to protect the class and professional interests of the select few who do manage to attain élite intellectual status, by reinforcing and widening the created gap between expert and layperson (a distinction that, again, tracks heavily along lines of race, gender, and so forth).

so you can see how these two issues really are part of one and the same structural problem, which is knowledge production as a tool of power, and one that both follows from and reinforces existing class hierarchies. in truth, knowledge is usually a collaborative affair (who among us has ever had a truly original idea...) and attributions should be a way of both acknowledging our debts to other people, and creating transparency in our efforts to stake claims and develop ideas. but, as long as there are benefits, both economic and social, to be gained from presenting yourself as an originator of knowledge, people will continue to be incentivised to do this. plagiarism is not an exception or an aberration; it's at best a very predictable outcome of the operating logics of this 'knowledge economy', and at worst��as in the examples above—a normal part of how expert knowledge is produced, and its value protected, in a system that is by design inequitable and exclusive.

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The tropical arid lands of Australia have been the continual home to Indigenous people possibly longer than anywhere on Earth today. Far from being one of the Earth’s remaining wilderness areas, the Western Deserts of Australia are the ancestral home of a number of Aboriginal peoples, who have managed these landscapes for millennia. Indeed, the effects of removing Indigenous peoples from the landscape in the 1960s was catastrophic, resulting in uncontrolled wildfires and a degradation of the ecological qualities for which this landscape was originally valued. Unsurprisingly, the return of these lands to Indigenous traditional owners over the past two decades has seen improvements in the socioecological dynamics of the region. Indeed, some Aboriginal peoples in Australia view “wild country” (wilderness) as “sick country’”: land that has been degraded through a lack of care through use. Thus, Aboriginal notions of wilderness are antithetical to the technocratic and romantic notions of wilderness representing “pristine” and healthy ecosystems that underpin many modern-day conservation efforts. The outcome continues to be a clash of worldviews in a globalizing society where the Western epistemologies governing dominant conservation practices operate in an echo-chamber that continues to erase other ways of knowing from conservation dialogue.

Indigenous knowledge and the shackles of wilderness

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

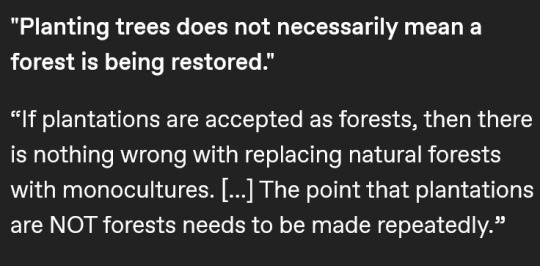

Despite its green image, Ireland has surprisingly little forest. [...] [M]ore than 80% of the island of Ireland was [once] covered in trees. [...] [O]f that 11% of the Republic of Ireland that is [now] forested, the vast majority (9% of the country) is planted with [non-native] spruces like the Sitka spruce [in commercial plantations], a fast growing conifer originally from Alaska which can be harvested after just 15 years. Just 2% of Ireland is covered with native broadleaf trees.

Text by: Martha O’Hagan Luff. “Ireland has lost almost all of its native forests - here’s how to bring them back.” The Conversation. 24 February 2023. [Emphasis added.]

---

[I]ndustrial [...] oil palm plantations [...] have proliferated in tropical regions in many parts of the world, often built at the expense of mangrove and humid forest lands, with the aim to transform them from 'worthless swamp' to agro-industrial complexes [...]. Another clear case [...] comes from the southernmost area in the Colombian Pacific [...]. Here, since the early 1980s, the forest has been destroyed and communities displaced to give way to oil palm plantations. Inexistent in the 1970s, by the mid-1990s they had expanded to over 30,000 hectares. The monotony of the plantation - row after row of palm as far as you can see, a green desert of sorts - replaced the diverse, heterogenous and entangled world of forest and communities.

Text by: Arturo Escobar. "Thinking-Feeling with the Earth: Territorial Struggles and the Ontological Dimension of the Epistemologies of the South." Revista de Antropologia Iberoamericana Volume 11 Issue 1. 2016. [Emphasis added.]

---

But efforts to increase global tree cover to limit climate change have skewed towards erecting plantations of fast-growing trees [...] [because] planting trees can demonstrate results a lot quicker than natural forest restoration. [...] [But] ill-advised tree planting can unleash invasive species [...]. [In India] [t]o maximize how much timber these forests yielded, British foresters planted pines from Europe and North America in extensive plantations in the Himalayan region [...] and introduced acacia trees from Australia [...]. One of these species, wattle (Acacia mearnsii) [...] was planted in [...] the Western Ghats. This area is what scientists all a biodiversity hotspot – a globally rare ecosystem replete with species. Wattle has since become invasive and taken over much of the region’s mountainous grasslands. Similarly, pine has spread over much of the Himalayas and displaced native oak trees while teak has replaced sal, a native hardwood, in central India. Both oak and sal are valued for [...] fertiliser, medicine and oil. Their loss [...] impoverished many [local and Indigenous people]. [...]

India’s national forest policy [...] aims for trees on 33% of the country’s area. Schemes under this policy include plantations consisting of a single species such as eucalyptus or bamboo which grow fast and can increase tree cover quickly, demonstrating success according to this dubious measure. Sometimes these trees are planted in grasslands and other ecosystems where tree cover is naturally low. [...] The success of forest restoration efforts cannot be measured by tree cover alone. The Indian government’s definition of “forest” still encompasses plantations of a single tree species, orchards and even bamboo, which actually belongs to the grass family. This means that biennial forest surveys cannot quantify how much natural forest has been restored, or convey the consequences of displacing native trees with competitive plantation species or identify if these exotic trees have invaded natural grasslands which have then been falsely recorded as restored forests. [...] Planting trees does not necessarily mean a forest is being restored. And reviving ecosystems in which trees are scarce is important too.

Text by: Dhanapal Govindarajulu. "India was a tree planting laboratory for 200 years - here are the results." The Conversation. 10 August 2023. [Emphasis added.]

---

Nations and companies are competing to appropriate the last piece of available “untapped” forest that can provide the most amount of “environmental services.” [...] When British Empire forestry was first established as a disciplinary practice in India, [...] it proscribed private interests and initiated a new system of forest management based on a logic of utilitarian [extraction] [...]. Rather than the actual survival of plants or animals, the goal of this forestry was focused on preventing the exhaustion of resource extraction. [...]

Text by: Daniel Fernandez and Alon Schwabe. "The Offsetted." e-flux Architecture (Positions). November 2013. [Emphasis added.]

---

At first glance, the statistics tell a hopeful story: Chile’s forests are expanding. […] On the ground, however, a different scene plays out: monocultures have replaced diverse natural forests [...]. At the crux of these [...] narratives is the definition of a single word: “forest.” [...] Pinochet’s wave of [...] [laws] included Forest Ordinance 701, passed in 1974, which subsidized the expansion of tree plantations [...] and gave the National Forestry Corporation control of Mapuche lands. This law set in motion an enormous expansion in fiber-farms, which are vast expanses of monoculture plantations Pinus radiata and Eucalyptus species grown for paper manufacturing and timber. [T]hese new plantations replaced native forests […]. According to a recent study in Landscape and Urban Planning, timber plantations expanded by a factor of ten from 1975 to 2007, and now occupy 43 percent of the South-central Chilean landscape. [...] While the confusion surrounding the definition of “forest” may appear to be an issue of semantics, Dr. Francis Putz [...] warns otherwise in a recent review published in Biotropica. […] Monoculture plantations are optimized for a single product, whereas native forests offer [...] water regulation, hosting biodiversity, and building soil fertility. [...][A]ccording to Putz, the distinction between plantations and native forests needs to be made clear. “[...] [A]nd the point that plantations are NOT forests needs to be made repeatedly [...]."

Text by: Julian Moll-Rocek. “When forests aren’t really forests: the high cost of Chile’s tree plantations.” Mongabay. 18 August 2014. [Emphasis added.]

#abolition#ecology#imperial#colonial#landscape#haunted#indigenous#multispecies#interspecies#temporality#carceral geography#plantations#ecologies#tidalectics#intimacies of four continents#archipelagic thinking#caribbean

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

[“When I asked Janelle, “Would you be hesitant to introduce a trans woman partner to your friends or coworkers,” she responded:

Janelle: Friends or coworkers, no. I mean when I like people, I have to show them off, so like, I mean, if I like her, Ima show her off, but [pause] you can still like show people off [pause] and be brave but still be scared. You know?

alithia: Would you be scared about being a woman with another woman or scared for how they’d react to her being a trans woman or?

Janelle: Her being a trans woman, because you know people [pause] like people are trained to discriminate people based [pause] I don’t, they’re like doing a lot of things in law that has to do with like if you like [pause] depending on your sexuality, you can be fired from a job or things like that, so like that’s very scary or and also the family like just so many factors. It’s just like anxiety-driven for me. So yeah, I, I, I feel like [pause] being scared or timid is [pause] justified in this sense. In this world that we live in.

Janelle was not afraid of how others would perceive her for being with a trans woman. Instead, she worried about them both living in a society that punishes individuals who deviate from cisgender, heterosexual norms of dating and relationships. Such fears of being harmed were perhaps more pronounced for her, with her and a hypothetical partner being two women vulnerable to the harms of cis-heteropatriarchy. These fears, though, were not simply about whether they would be accepted by others, but whether they would be able to survive and thrive, as LGBT people, particularly trans people, do not have workplace discrimination protections in many states across the United States.

Peaches connected such fears to race. I asked Peaches, “If you were with a woman and knew she was trans, and y’all had been together for awhile, would you be hesitant at all to introduce her to your family?” Peaches responded:

Peaches: No. That’s a lie yes. Like my family are, they, they can be ignorant and like my mom especially, love her to death, but she says like a lot of insensitive things. My mom’s White. She doesn’t think before she talks a lot. So, if anything, I would just be like a little bit hesitant to like take her around my family, because I wouldn’t want them to say anything in front of her um that could make her feel uncomfortable.

alithia: Okay would they do that whether it was a cis woman or a trans woman?

Peaches: Um I think it, they wouldn’t do it as much with a cis woman, yeah.

Peaches was raised by a White, Portuguese mother and a Black father, and she noted her mother’s whiteness as integral as to why she microaggressed others. Peaches was referring to gender and racial ignorance and highlighted a fear of how her mother would treat a trans woman partner. Her connection of this ignorance, cissexism, and racism is part of a larger epistemology of White ignorance that functions to protect “those who for “racial” [and gendered] reasons have needed not to know” how their understandings of the world deny the lived experiences of Black, Indigenous, and other cisgender/transgender people of color and other transgender people. This White ignorance produces a misunderstanding of reality as inherently binary vis-à-vis sex and gender and an inculcated “alexithymia,” or a socialized inability to feel empathy for racialized Others. Thus, Peaches’ mother’s repetitive “[saying of] a lot of insensitive things” is not so much about a hatred of trans people/of color but the result of an actively developed ignorance.”]

alithia zamantakis, from thinking cis: cisgender heterosexual men, and queer women’s roles in anti-trans violence, 2023

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Pursuit of Knowledge Without Wisdom or Virtue: An Intellectual Tragedy

Today’s topic is one of those that more often comes out during Sangha meetings or in lay discussions: knowledge, when isolated from wisdom (sophia / σοφία) and virtue (aretḗ / ἀρετή), is no longer a guarantor of human flourishing but may become a tool of hubris (hybris — ὕβρις) and ruin. Photo by Magda Ehlers on Pexels.com Knowledge (epistēmē / ἐπιστήμη) here must be distinguished from wisdom:…

View On WordPress

#Al-Ghazālī#ancient Greek philosophy#Aristotle#Buddhist ethics#Buddhist philosophy#cognitive science and ethics#cross-cultural ethics#educational philosophy#environmental ethics#epistemic justice#epistemology#ethical knowledge#ethical responsibility#Ethics#existentialism#Foucault#future ethics#Hans Jonas#historical philosophy#indigenous knowledge systems#intellectual humility#intellectual responsibility#justice#Kant#knowledge and compassion#knowledge and domination#knowledge and justice#knowledge and power#knowledge ethics#moral anthropology

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Philosophy of the Rights of Nature

The philosophy of the rights of nature represents a paradigm shift in how we view and interact with the natural world. Traditionally, nature has been seen as a resource for human use, but this perspective advocates for recognizing the intrinsic value and legal rights of natural entities. This philosophy challenges anthropocentric worldviews and seeks to establish a more harmonious relationship between humans and the environment by recognizing the rights of ecosystems, species, and natural processes.

Key Themes in the Philosophy of the Rights of Nature

Intrinsic Value of Nature:

Central to this philosophy is the idea that nature has value beyond its utility to humans. Natural entities have their own right to exist, thrive, and evolve.

This perspective emphasizes the moral duty to respect and protect nature for its own sake.

Legal Personhood for Nature:

One of the most revolutionary aspects of this philosophy is the proposal to grant legal personhood to natural entities such as rivers, forests, and ecosystems.

Legal personhood would allow nature to have rights that can be defended in court, similar to corporations or individuals.

Interconnectedness of Life:

This philosophy highlights the interconnectedness of all life forms. Human well-being is deeply linked to the health of the natural environment.

By protecting the rights of nature, we also ensure the long-term sustainability and health of human communities.

Ecocentrism vs. Anthropocentrism:

The rights of nature philosophy advocates for an ecocentric approach, which places ecological well-being at the center of decision-making.

This contrasts with anthropocentric approaches that prioritize human interests over ecological health.

Ethical Responsibility:

This philosophy asserts that humans have an ethical responsibility to protect and preserve nature.

It calls for a shift from exploitation and domination to stewardship and respect.

Indigenous Perspectives:

Many Indigenous cultures have long recognized the rights of nature and the deep connection between humans and the environment.

The philosophy of the rights of nature often draws on these Indigenous worldviews and knowledge systems.

Environmental Justice:

The rights of nature philosophy is closely linked to environmental justice, which seeks to address the disproportionate impact of environmental degradation on marginalized communities.

Recognizing the rights of nature can help ensure that environmental protections are applied equitably and justly.

Global Movement:

The movement for the rights of nature is gaining traction worldwide, with several countries and localities recognizing legal rights for natural entities.

Notable examples include Ecuador, which enshrined the rights of nature in its constitution, and New Zealand, which granted legal personhood to the Whanganui River.

Challenges and Criticisms:

Critics of the rights of nature argue that granting legal rights to nature could lead to legal and practical complications.

There are also debates about how to balance the rights of nature with human development needs.

Future Implications:

Recognizing the rights of nature has profound implications for law, governance, and ethics.

It could lead to new forms of environmental governance that prioritize ecological sustainability and the well-being of all life forms.

The philosophy of the rights of nature represents a transformative approach to our relationship with the environment. By recognizing the intrinsic value and legal rights of natural entities, this philosophy seeks to create a more just, sustainable, and respectful coexistence between humans and the natural world. It challenges us to rethink our ethical responsibilities and to develop legal frameworks that honor and protect the rights of nature.

#philosophy#epistemology#knowledge#learning#chatgpt#education#ethics#nature#Rights of Nature#Environmental Philosophy#Legal Personhood for Nature#Ecocentrism#Environmental Ethics#Indigenous Perspectives#Environmental Justice#Intrinsic Value of Nature#Sustainability#Global Environmental Movement

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

although obviously i understand why it is used and that it can have a great deal of pragmatic use when applied towards the goal of extracting concessions from settler-colonial governments i v. v. strongly disagree with the rhetoric of calling US/Canadian tribal treaties 'illegitimate', or arguing that tribal land was never 'legally ceded', simply because it implicitly accepts the framing that there is some sort of theoretical 'legitimate' way in which settler colonialism and the appropriation of indigenous land could have been conducted, or that there is some specific legal formulation which had it been mutually agreed upon would have justified colonialism. i feel v. similarly about people calling the iraq war 'illegal', emphasizing that the US 'violates international law', or calling sanctions 'criminal'. bourgeois law exists to justify & legitimize the economic domination of the bourgeoisie--it's not a useful framework to buy into--it is unstable and hostile epistemological ground to work from.

501 notes

·

View notes

Text

Professor Eric Cheyfitz of Cornell University will be teaching a course in spring 2025 with the title of "Gaza, Indigeneity, Resistance." Professor Cheyfitz is an activist in the anti-Israel BDS (boycott, divestment, and sanctions) movement - he first came to my attention in the spring of 2014, when he was invited to speak at Ithaca College in favor of the academic boycott of Israel.

This is the course description as published in the Cornell online catalog:

AIIS 3500 Gaza, Indigeneity, Resistance Course information provided by the Courses of Study 2024-2025. The first half of the course will be devoted to situating Indigenous peoples, of which there are 476,000,000 globally, in an international context, where we will examine the proposition that Indigenous people are involved historically in a global resistance against an ongoing colonialism. The second half will present a specific case of this war: settler colonialism in Palestine/Israel with a particular emphasis on the International Court of Justice (ICJ) finding "plausible" the South African assertion of "genocide" in Gaza. Outcomes

Identify and analyze key components of Indigenous perspectives on political, social, and environmental systems(this can be observed/assessed through written reflections and discussions).

Define and differentiate key terms such as "Indigeneity," "Resistance," "Settler Colonialism," and "Genocide" in both international law and Indigenous contexts(this can be observed/assessed through writing assignments and presentations).

Conduct a historical analysis of Indigenous peoples' current situations(this can be observed/assessed by researching and presenting findings in a paper).

Conceptualize your idea of a just society through the comparison of Western and Indigenous epistemologies (this can be observed/assessed through argumentative essays and class debates based on insights gained from the previous outcomes).

Apply these outcomes to an understanding of the history of Israel/Palestine with a focus on the history of Gaza and the current Gaza war (this can be observed/assessed by researching and presenting findings in a paper).

Professor Cheyfitz is not only anti-Israel - he thinks Israel is as bad as Nazi Germany. From the JTA article about the course:

Cheyfitz has written repeatedly that he considers Israel’s war against Hamas to be a genocide, that Israel is a “close fit” with Nazi Germany and, in 2014, that “Gaza has become an extermination camp, run by Jews.”

#antisemitism#israel#jumblr#leftist antisemitism#cornelluniversity#cheyfitz#gaza#genocide accusation#settler colonialism

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

What, then, are the cultural criteria of Indianness à la the law of the white? As has been a typical feature of the discourses of dominance throughout the Western Hemisphere, Indians are imagined as ‘‘primitive/traditional’’ in the sense of being outside of and in binary opposition to ‘‘civilization/modernity.’’ It is a representational order ‘‘predicated upon a structure of opposites’’ in which ‘‘the ‘savage’ [is] defined against what the perceiving’’ non-Indian Brazilians ‘‘[understand] themselves to be.’’ If Indians participate in professions, use technology, wear clothes, and inhabit urban geographies (which denote modernity), then they are not considered Indian [...] As Eliane Potiguara, a Potiguara Indian who resides in Rio de Janeiro, notes,

Many people in Brazil were once torn away from their communities, and they later suffered much discrimination trying to recover their loss. For example, we spend most of our lives trying to reaffirm that we are Indians, and then we encounter statements like, ‘But if you wear jeans, a watch, sneakers, and speak Portuguese…’ Society either understands Indians all made-up and naked inside the forest or consigns them to the border of big cities.

Indians, then, are not imagined as catching the subway, drinking soda, piloting airplanes, using credit cards, watching television, and so on. They are also not thought of as being doctors, college students, janitors, maids, factory workers, or lawyers. Indians are not considered to be residents of urban shantytowns, beachfront resorts, suburban homes, or plantation estates. To live in these so-called civilized spaces, to be in these allegedly modern occupations, to possess the latest consumer goods of the global economy, renders someone non-Indian. […] To be an authentic Indian, one must live like a primitive in a traditional manner. One must embody the antiself of civilization, which in Brazil means living in a hut in the middle of the forest, naked, and with no contemporary technological conveniences.

[...]

Posttraditional Indians live in the rubble of tradition. Many, if not most, of their tribal traditions, epistemologies, languages, religions, stories, and philosophies have been crushed by conquest rather than water. José, a forty-four-year-old subsistence farmer and Xacriabá leader I interviewed in 1995, quantified the degree of this fragmentation as having ‘‘lost 90 percent of what we were.’’ Thus, the traditions of posttraditional Indians are not complete languages but sometimes only sets of words, not intact religions but only the memory of a sole trickster figure or ceremonial dance, not a comprehensive knowledge of all the vegetation in an area but the understanding of the medicinal use of a few local plants, not a family heirloom but a pottery shard found in an abandoned field or the story of a battle lost.

Salvinho Pataxó, a subsistence farmer and community leader, described the posttraditional condition in the following manner:

The Indian from the east and northeast is an Indian who has always endured massacres. […] But still the people say that we’re not real Indians because we wear shorts, sneakers, put a watch on our arms. But in reality, all of this is meaningless. What matters is the root that comes from there [he points to the ground], underneath our community, the root that comes from our ancestors.

[…] Posttraditionality is not simply a question of living in the ruins of tradition, for such an individual might be nontraditional or antitraditional. There is instead another component to posttraditionalism: the meanings that one ascribes to these ruins. To be a posttraditional Indian is to regard these fragments and shadows of tradition as relevant or important, to embrace, privilege, and value them. It is to define one’s indigenous ancestral roots as essential to one’s identity, to make them the anchor of one’s dreams and future, and to work toward their recovery. In Salvinho Pataxó’s words:

Our dream is always to fight to defend our parente [kin], to unite our community. To try and recover my language, my culture, and my history, this is the future that I’m working toward. This is the future of my dreams.

My use of tradition, then, is not meant to invoke this notion of static, timeless, primordial Indians positioned in opposition to the most current constructions of modernity. Nor do I wish to imply that posttraditional Indians are inauthentic or less authentic Indians. In other words, I am not suggesting a view of traditional that implies an underlying schema in which real Indians are only those who have putatively remained ‘‘securely located outside modern societal boundaries’’ and as such, are able to be considered biologically and culturally ‘‘pure.’’

Racial Revolutions, Jonathan Warren.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous genocide and removal from land and enslavement are prerequisites for power becoming operationalized in premodernity, a way in which subjects get (what Wynter names) “selected” or “dysselected” from geography and coded into colonial possession through dispossession. The color line of the colonized was not merely a consequence of these structures of colonial power or a marginal effect of those structures; it was/is a means to operationalize extraction (therefore race should be considered as foundational rather than as periphery to the production of those structures and of global space). Richard Eden, in the popular 1555 publication Decades of the New World, compares the people of the “New World” to a blank piece of “white paper” on which you can “paynte and wryte” whatever you wish. “The Preface to the Reader” describes the people of these lands as inanimate objects, blank slates [...]. [Basically, "Man" is white, while non-white people are reduced to an aspect of the landscape, a resource.] Wynter suggests that we [...] consider 1452 as the beginning of the New World, as African slaves are put to work on the first plantations on the Portuguese island of Madeira, initiating the “sugar-slave” complex - a massive replantation of ecologies and forced relocation of people [...]. Wynter argues that the invention of the figure of Man in 1492 as the Portuguese [and Spanish] travel to the Americas instigates at the same time “a refiguring of humanness” in the idea of race. This refiguring of slaves trafficked to gold mines is borne into the language of the inhuman [...].

---

The natal moment of the 1800 Industrial Revolution, [...] [apparently] locates Anthropocene origination in [...] the "new" metabolisms of technology and matter enabled by the combination of fossil fuels, new engines, and the world as market. [...] The racialization of epistemologies of life and nonlife is important to note here [...]. While [this industrialization] [...] undoubtedly transformed the atmosphere with [...] coal [in the nineteenth century], the creation of another kind of weather had already established its salient forms in the mine and on the plantation. Paying attention to the prehistory of capital and its bodily labor, both within coal cultures and on plantations that literally put “sugar in the bowl” (as Nina Simone sings) [...]. The new modes of material accumulation and production in the Industrial Revolution are relational to and dependent on their preproductive forms in slavery [...].

---

Catherine Hall’s project Legacies of British Slave-Ownership makes visible the complicity in terms of structures of slavery and industrialization that organized in advance the categories of dispossession that are already in play and historically constitute the terms of racialized encounter of the Anthropocene. In 1833, Parliament finally abolished slavery in the British Caribbean, and the taxpayer payout of £20 million in “compensation” [paid by the government to slave owners for their lost "property"] built the material, geophysical (railways, mines, factories), and imperial infrastructures of Britain and its colonial enterprises and empire. As the project empirically demonstrates, these legacies of colonial slavery continue to shape contemporary Britain. A significant proportion of funds were invested in the railway system connecting London and Birmingham (home of cotton production and [...] manufacturing for plantations), Cambridge and Oxford, and Wales and the Midlands (for coal). Insurance companies flourished and investments were made in the Great Western Cotton Company, for example, and in cotton brokers, as well as in big colonial land companies in Canada (Canada Land Company) and Australia (Van Diemen’s Land Company) and a number of colonial brokers. Investments were made in the development of metal and mineralogical technologies [...].

The slave-sugar-coal nexus both substantially enriched Britain and made it possible for it to transition into a colonial industrialized power [...]. The slave trade [...] fashioned the economic conditions (and institutions, such as the insurance and finance industries) for industrialization. Slavery and industrialization were tied by the various afterlives of slavery in the form of indentured and carceral labor that continued to enrich new emergent industrial powers from both the Caribbean plantations and the antebellum South. Enslaved “free” African Americans predominately mined coal in the corporate use of black power or the new “industrial slavery,” [...].

---

The labor of the coffee - the carceral penance of the rock pile, “breaking rocks out here and keeping on the chain gang” (Nina Simone, Work Song, 1966), laying iron on the railroads - is the carceral future mobilized at plantation’s end (or the “nonevent” of emancipation). [...] [T]he racial circumscription of slavery predates and prepares the material ground for Europe and the Americas in terms of both nation and empire building - and continues to sustain it.

---

All text above by: Kathryn Yusoff. "White Utopia/Black Inferno: Life on a Geologic Spike". e-flux Journal Issue #97. February 2019. At: e-flux dot com slash journal/97/252226/white-utopia-black-inferno-life-on-a-geologic-spike/ [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me. Text within brackets added by me for clarity and context. Presented here for commentary, teaching, criticism.]

#ecology#multispecies#tidalectics#indigenous#carceral geography#abolition#kathryn yusoff#katherine mckittrick#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies

159 notes

·

View notes