#Indian paradox

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The Great Indian Paradox: When Sixes Outscore Sacrifices

**Introduction:**In the grand Indian theater, where cricket bats swing mightier than the swords of justice, and the glitz of Bollywood overshadows the grit of the border, we find ourselves in a saga of ironic contrasts. Welcome to the land where celluloid heroes are worshipped, and real heroes often forgotten, where a sixer can fetch millions, but a soldier’s sacrifice struggles for a headline.…

View On WordPress

#2023#Bollywood#celebrities vs heroes#Cricket#economic disparity#entertainment industry#farmers&039; struggles#humor#India#Indian Army#Indian culture#Indian paradox#irony#national priorities#real vs reel heroes#Satire#societal contrasts#societal values#soldiers&039; sacrifice#teachers in India#wage gap#witty commentary

0 notes

Text

Aunt Selvi Writes the Maverick's Manifesto.

A quiet living room with books, filter coffee, and the distant sound of a koel intercepted with cacophony of horns “just what are you doing? Siri’ ‘branding the blogger ParwatiSingari” siri replied. “should not be difficult, one quarter wool gathering, one quarter filter coffee, and rest of ancestral candor” Hello Selvi Ma’am. Based on algorithmic analysis and keyword ranking, would you like…

0 notes

Text

The Paradox of Public Space

It was a blistering afternoon in Varanasi, the kind of heat that made the air shimmer in waves and the asphalt buckle beneath the weight of the sun. Vikram stepped off the crowded bus, wiped his brow with the sleeve of his shirt, and set out toward the Ganges, hoping for a breath of cool air by the riverbanks. The streets were thick with the scent of curry, incense, and the occasional cloud of diesel exhaust.

As he walked, he couldn’t help but notice the familiar scene: a group of men casually urinating against a wall near the market. They didn’t look up, didn’t seem to care. No one bothered them. A few women avoided the alley with a polite turn of their heads, but most people pretended not to see. The men’s backs were to the world, their faces turned toward an invisible horizon, lost in their own private moment of release....read more

#India societal norms#public space paradox#public urination in India#public affection in India#kissing in public#social contradictions#Indian culture#public decorum#Insightful take on Indian paradoxes#modernity vs tradition#India relationships

1 note

·

View note

Text

Apparently Paradox, Yoyo Honey Singh and Nora Fatehi are shooting something DAMN !!! Are they shooting the Payal soundtrack finally?

#yo yo honey singh#paradox live#art#indian#india#tumblr blog#blogger#blog post#music blog#music videos#tumblr fyp#foryou#fypage#dhhscene#dhh#desi hip hop#desi#Spotify

0 notes

Text

My love,

You ask "where do I go with all this rage?"

And I say, you come to me. You come home.

Because I see it, every wave of fire in you,

and still I see the ocean beneath in you vast, deep, healing.

Remember the story I once told you of the saint who kept saving the scorpion, even as it stung him again and again. When asked why, he said "Stinging is its nature, but saving is mine."

And you, my love,

you are the saint.

Gentleness is not your defeat, it is your defiance.

Softness is not your weakness, it is your sword.

Its you who taught me once that

Be yourself in a world that demanded otherwise.

So rage if you must.

Cry, scream, write, burn, breathe.

But know that your power lies not in losing yourself to the world —

but in remaining YOU despite it.

Be patient, love.

You are not lost. You are light,

and the good will find its way back to you.

I’ll remind you every time you forget.

Because this is us. This is home.

Where do I go with all this rage?

They hurt me and still expect my kindness and empathy,

while I carry the wounds they gave.

Where do I put this hate?

What do I do with all these questions in my head?

How do I stay soft in a world that’s so cruel?

I don’t want to be this angry.

I want peace but not the kind that silences me.

I want peace that feels free.

So I ask again

where do I go with all this rage?

#i hate it here#why#rant post#whyyyy#feminine rage#female rage#indian#desiblr#desi#where do i go from here#where#dark academia#poetic#painful#paradox live

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Werewolf: the Apocalypse 5th Edition and the Anti-Indigeneity in the Gaming Industry

reosted with permission from J.F. Sambrano

Dagot’ee!

Shii J.F. Sambrano gonsēē. My nations are Chiricahua Apache (Ndeh) through my maternal grandmother and Cora Indian (Náayarite) through my maternal grandfather. I am a mixed race Indigenous person, and through my father my heritage is English and Scottish. I am currently residing and doing work in my community on the lands of Lummi Nation. I use both gender non-binary and masculine pronouns, but prefer the former. I have several published works in the TTRPG industry, and am probably most known for my contributions to Mage: the Ascension 20th Edition, Werewolf: the Apocalypse 20th Edition, and the Transformers Roleplaying Game, as well as being part of the Essence 20 development team. Further, I also work in higher education at an Indian college, both advising and teaching Indigenous students across the United States. My passion is education, and I believe that we all learn through play, and that TTRPGs are a valuable source of learning, especially on personal, cultural, and social levels. This has always been what has drawn me to TTRPGs since I started playing M.E.R.P. with my brother in 1996 (and before that HeroQuest), through to my “graduation” into more story-driven games such as those presented in the Storyteller System, until now, where I author and produce my own roleplaying games.

I was also part of the First Team (in-joke intentional) hired by White Wolf Studios/Paradox Interactive via Hunters Entertainment to develop and author Werewolf: the Apocalypse 5th Edition. After several months of work, Paradox Interactive chose to go in another direction in early 2021 (I believe it was either March or April) and in fall of that year, it was announced that Werewolf would instead be taken in house, with Justin Achilli as the Brand Creative Lead and primary author of the book. Going forward I will be describing my experience while I worked with Paradox Interactive, primarily through Karim Muammar, White Wolf’s Brand Editor, as well as the developmental editor for Werewolf. Although I worked in a team, both with hired authors and in-house representatives at Hunters Entertainment, I will not be speaking for the experience of others, except when specifically noting unanimous consensuses, and specific interactions (which will go unnamed) that are particularly relevant. My hope is that by highlighting some of the anti-Indigenous attitudes that are central to the foundational members and leaders of the White Wolf brand, that I can provide opportunities for growth and healing within the World of Darkness TTRPG community, but also in the broader gaming community, where these behaviors and attitudes are rampant. I also want the community to have a better understanding of what this experience is like internally, and the challenges that Indigenous creators, as well as other marginalized creators, are met with when they try to make positive change within nerd and geek communities clinging to inherited white supremacist values, even if they don’t realize they are doing so.

What I do not want to be doing in this article is creating fuel for edition wars. I believe that both legacy and Werewolf 5th are rife with anti-Indigenous attitudes, and appalling amounts of appropriation. Both versions deserve criticism, I am not defending one over the other, I am only sharing what my experience was like working on the 5th edition of the book. Further, please understand that I was originally going to wait until I had read the final copy of the book, because I wanted to know how much of my work was used (based on previews I already know some was, just not the extent) and whether or not they decided to credit me for that work, and how I was going to be credited. My belief is that I likely will not be, but I am genuinely uncertain. Knowing how they handled that would have reframed how I addressed this. But more importantly, I want it to be very clear that even before Paradox ultimately pulled the plug on the Hunters team, I was preparing to exit working on the project based on the experience I will describe below. Not only did I find it frustrating, and personally disparaging, but I ultimately decided I was uncomfortable with my name being attached to the product based on the direction they wanted to go. So while I wanted to know whether or not I would be credited, because it would teach me something about their internal practices, I do not want or need the credit.

Finally, the reason that I decided to speak about this now instead of after having a chance to inspect the final product, was because my personal experience dealing with anti-Indigeneity coming from Paradox was just that: personal. But since then I have witnessed a throughline of hateful and xenophobic attitudes wielded against Indigenous people across the globe, and we do not deserve this treatment. I was outraged over the events that led to the segregation of the Latin American fanbase, which culminated from bottom-up criticism about how poorly their people and countries were being defined through World of Darkness products, and ended up with the firing of their Latin American Brand Ambassador, Alessa Torres, because she chose to stand with her community in those criticisms. I was further appalled when the likeness of Tāme Wairere Iti was shoehorned into the Werewolf book, a blatant example of cultural theft: not only in stealing the literal physical identity of an Indigenous person, but also his sacred tā moko. When Paradox Interactive issued an apology for this, it felt incredibly hollow to me in the wake of these events, the hateful attitudes I had personally witnessed coming from the top.

Whether from North America, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, or Peru, or across the globe in New Zealand, not only do Indigenous people deserve better treatment from such a major company, but their Indigenous and Latino fanbases, who have twisted and worked themselves through difficult representation for decades at this point, deserve better. Apologies are not enough, especially when they come with next to no real change.

Werewolf: the Apocalypse in Context

At the time that White Wolf Publishing began to produce its World of Darkness line, the TTRPG industry was dominated by white men, both as producers, developers, and authors, as well as the main characters in their settings. White Wolf's World of Darkness made an impact at the time, by defying these Eurocentric, patriarchal presentations, first by defaulting to feminine pronouns throughout Vampire: the Masquerade, and then by focusing on Indigenous representation and values in Werewolf: the Apocalypse, and as a young Indigenous nerd, it had a positive impact on me, as I know it has on some other Indigenous people who became fans of the World of Darkness at the time. This was because before opening the pages of Werewolf: the Apocalypse, I had never seen heroes that I could play who looked like me and my culture. It was off, and often offensive, but it was my first experience in which I could directly play a hero who shared my heritage--and I also had more than one option through two different Tribes to do so. This might sound a little like I was cheering for table scraps, but again, at the time, table scraps was more than I had ever seen before.

Werewolf: the Apocalypse 1st Edition was originally published in 1992 via then White Wolf Publishing (not to be confused with Paradox Interactive's White Wolf). From its inception, the premise was interwoven with what its then-authors believed to be Indigenous praxis and representation. Like many pop-culture presentations of Indigeneity from this time period (see Fern Gully, Dances With Wolves, Disney’s Pocahontas, or in TTRPGs, the NAN from Shadowrun) it was rife with problematic and even offensive stereotyping. The most obvious examples thereof are within the two "Pure Tribes" Uktena, and W****** who I will henceforth refer to as Older and Younger Brother. However, Indigenous inspiration was at the core of the game's spiritual premise as well, where animism and "Totems" are central to the setting and gameplay. The way these concepts are presented is trivializing and dehumanizing, but it is important to acknowledge that the appropriation present in Werewolf: the Apocalypse goes a lot deeper than the two Brother Tribes (even the term "Tribe" was meant to invoke a vision of Indigeneity compared to the previous setting in the line's use of "Clan"). Additionally, there is art throughout every generation of these gaming books that represents humans, wolves, and human-wolf hybrid forms wearing Indigenous regalia, including sacred items such as headdresses, or engaged in sacred rituals such as the Sun Dance. The list of problematic representations goes deep, and my examples only scratch the surface, but it is also important for me to note the positive impact that this had, particularly in the 90's.

Even though the primary contributors to these narratives were non-Indigenous authors, or in one case, a Pretendian, and another, a culturally disconnected author, by the time the Revised (or Third Edition) era of the books came around, White Wolf Publishing was actively engaged in cultural consultation. While I do not believe cultural consultation makes a big difference on its own, it matters that the attempt was made, to a degree: while these efforts fall short of what needs to be seen in cultural representation, this was still ahead of most other gaming companies at this time.

Hired by Hunters Entertainment

In February of 2020 I was approached by one of the co-owners of Hunters Entertainment to be one of the primary authors for Werewolf: 5th Edition due to my work on other World of Darkness projects, and let's be honest, because I was capable of bringing a much needed Indigenous perspective to a gameline that was rooted in Indigeneity and rotting with appropriation and racist stereotypes. I was overall receptive to the invitation, largely because I was very passionate about the World of Darkness setting overall, and Werewolf in particular, due to the impact that 90's representation had on me when I was a younger gamer. I also felt hopeful that with a really hard rewrite of Indigenous aspects of the game that I could shift a lot of really painful aspects of the game into something that was a net positive for Indigenous representation. I will tell you now, more than anything, I was excited to rewrite the Younger Brother Tribe, because when separated from racist authors, their message is very empowering and real to my lived experience.

That said, I did not agree to join the project without first asking for reassurances. I said that I was not willing to write negative Native stereotypes. I would not use appropriative language, or generally engage in appropriative writing (which meant at minimum that the names of the Pure Tribes would need to change), and most importantly, that I would not not engage in writing that contributed to erasure. While the person who recruited me to work on the project was eager to work with me, he acknowledged that he was not sure he could get everything I wanted to see approved, but also promised to fight for everything I suggested as hard as he could. Additionally, he shared with me that the original setting pitch for W5 involved all of Younger Brother being slaughtered en masse in a massacre. I made it clear that this was exactly the kind of thing that I would not write. I cannot remember if this was something he suggested to be changed before or after I was invited onto the project, but with some pushback it was changed. However, I point this out because I want you, the reader, to understand how eager Paradox Interactive was to start with mass genocide and erasure as a foundation to the setting. All that said, I cannot stress enough that I have had nothing but positive experiences with Hunters Entertainment, and none of the following concerns fall upon them.

The Sword of Heimdall

The first encounter the Hunters Entertainment team as a whole had with problematic guidelines for the W5 draft was the direction that Paradox Interactive wanted to go with the Sword of Heimdall. At the time, the suggestions from Paradox and Karim Muammar were that the Sword of Heimdall was going to represent the new major villain of the Werewolf setting, and that they were to also represent the far-right, fascist direction that Werewolf society so often turned toward. They were meant to be representative of how far the new concept of Hauglosk could take entire communities. However, the Sword of Heimdall was discussed interchangeably with the Get of Fenris as a whole, and more than once Muammar seemed to suggest that every member of this Tribe was guilty of the same attitudes espoused in previous editions from the Sword of Heimdall. Now let's not beat around the bush: the Sword of Heimdall are literal Nazis. They believe directly in white supremacy and don't shy from it. They wanted to cleanse impure elements from the Get of Fenris, including BIPOC people, other non-white ethnicities, women, neurodivergent Garou, and other disabled Garou.

The writing team found this approach problematic for several reasons. The first, and most obvious, was that the direction seemed to want to turn one of the most popular Tribes into a horrific stereotype of its most abhorrent faction. Whether or not Muammar’s goal was to turn them into villains, we could not imagine a world where fans of previous editions would get their hands on this book, and not look for a way to play one of their previous favorite groups, thus creating the issue of making a guide to playing Nazi. Even beyond that, it’s not as if historically there were not players who used the tools of the setting to play Black Spiral Dancers, why wouldn’t this draw people who actually wanted to role-play through these toxic, harmful politics? Further, and while this is less important, it left a bad taste in my mouth, the justification for this major shift in Werewolf lore seemed to change over each pass. At first, Muammar suggested that all Fenrir were Nazis/SoH. Then, when he was provided with evidence that it was a small faction that was eliminated in the early 2000’s, he started to shift toward the idea that we should not follow the lore. Finally, when every single member of the writer’s team flatly refused to provide what would essentially be “a player’s guide to being a Nazi werewolf” the writing was on the wall about the end of our involvement with this product. More than once, he suggested that we were cowardly social justice warriors for being unwilling to work with this concept, even though there were several attempts to write a heroic version of the Fenrir that were focused on undoing these ills of the past.

Indigenous Erasure in Werewolf: 5th Edition

While the entire Hunters Entertainment writing team was handling the major, glaring issue of Paradox’s fervor to include a major Nazi element in Werewolf, I was personally dealing with the problematic approach to the Indigenous issues in the setting. The largest problem, for me, was in addressing Younger Brother’s issues, the history of non-Indigenous writers creating horrifically racist stereotypes, and what was valuable in the Tribal identity that should be saved and recentered. However, my attempts to do so were thwarted with every approach. I rewrote this Tribe four times, and offered three different versions of it to try to earn approval for a final write-up, but each time there was a lot of negativity directed towards my attempts and all them boiled down to this: Muammar felt that having two Tribes (both Younger and Older Brother) representing the “Indigenous population” was too many, and wanted them to only be focused on Older Brother, and that Younger Brother’s connection to a central, Indigenous identity, was undesirable because “other sources wrote them as having Siberian and European connections” and that future writing on this Tribe would require a lot of sensitivity…suggesting that one, Muammar wasn’t interested in doing the work to handle that level of sensitivity, and further, that he wasn’t interested in including me in future work, since I was involved with doing that at the time.

I want to take a moment to remind you that the work that was put into recovering Younger Brother started with “Let’s Kill Them Off” and at this point, through a combination of convincing and pleading, had been walked back to “They can live, but now they’re not connected to being Indigenous anymore” which is just representative genocide of a different variety. “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” It was also explicitly something I said I would not write about going into this project. Ultimately, my efforts did not get much further than this, with some specific exceptions I will cite below.

Karim Muammar’s Anti-Indigenous Positions

Muammar consistently and repeatedly communicated to the team in ways that were condescending and dismissive of our collective accomplishments and capabilities, but from my perspective, no one suffered as much significant derision as I did while discussing the changes I wanted to make to Younger and Older Brother in order to make their representation empowering and exciting.

In the pulled quote from the previous paragraph, I want to point out to you that Muammar, who had the title of Lead Editor on this project, refused to capitalize Native American. Further, he would often redline my work with edits to decapitalize my own uses of Native American, as well as the word Indigenous when referring to Indigenous peoples. While there are plenty of people who might want to argue about this, I will point out that both the AP style guide as well as the Chicago style guide (the one which I am most familiar with in my academic historical work) both call for Indigenous to be capitalized when referring to a people. Further, I challenge anyone to defend the consistent decapitalization of Native American. More importantly, the reason that these are standards in respected style guides, is because the English language has been used historically to oppress and erase ethnic identities, including Indigenous identities. By transforming adjectives into proper nouns, we are declaring that Indigenous and Native aren’t descriptors that can be applied to animals, plants, and soil, but real lived identities and culture groups.

When I was explaining to the Paradox team (which was mostly just Muammar) why it was important to change the names of these two Tribes from the appropriative (and offensive) ones used in the past, Muammar pushed back by defending the previously used Younger Brother name, even after reading my extensive research and explanation about how this would harm Indigenous communities and fans.

While doing so, he also decided that it was appropriate to refer to this entirely Native American tribe by the word “savages” a slur that has been specifically used to dehumanize Native Americans, and then mocked my rewrite that focused on presenting them as stewards of the land using Indigenous methodologies and praxes, instead of the “savage” racist stereotypes they were presented as in previous editions. Further, as in the above quote, even after it was communicated that the use of this term was problematic, he kept doubling-down to use it to refer to the Tribe.

Even though I worked hard to redefine Younger Brother through Indigenous theory, such as place-based theory, relational theory, and communal theory, Muammar either refused to recognize this work, dismissing it as simple, or else simply could not understand the importance of these changes. Either way, the choice is that he didn’t want them to change, or couldn’t comprehend why the change was important because of how entrenched in white supremacist thinking he is. Further, after the massive effort that I put forward to attempt to educate him and the rest of the Paradox team on these issues, the insistence on using offensive terms and belittling my work felt intentional. So let’s talk about the work I did that was above and beyond my job description: free cultural consulting work.

“Sensitivity” and Consultation

I have seen several misunderstandings of my role working on this project going around, so I want to make something very clear. I was hired to work on this project as an author, and nothing else. I was not ever hired to be a cultural consultant. I do not do cultural consulting work. While I feel that there are many creators and companies who hire cultural consultants with the best intentions in mind, their responses often fall short of what is needed, as no one is ever obligated to actually follow the advice of cultural consultants. Further, I think there are also many companies who choose to hire cultural consultants only to say “we did this minimal step, and that is enough” in order to ward off naysayers.

However, anyone who hires me gets some level of cultural consulting for free, because it comes out in my writing–in both what I won’t write and what I choose to center my writing around. In the case of Werewolf 5th Edition, however, it was far more involved than this. I came with a plethora of “I will not write X” because I knew the setting was so problematic. A short list of my demands besides not being willing to write Indigenous erasure, was that we needed to change the names of the Pure Tribes (and the term Pure Tribe itself), we needed to change the word Totem to Patron, and also the Patrons of the Pure Tribes. We needed to move away from the term Metis for obvious reasons, and we needed to move away from the term Skin Dancers. I also specifically noted that there was a lot of cultural theft happening from the beginning of Werewolf until now that I wanted to address. The only way these issues were going to be addressed was to convince Paradox they were actual issues on the level of PR concerns, because nothing else was likely going to be considered. So in order to achieve this, I put in weeks worth of research, writing, and meetings with top level administrators with Hunters Entertainment so that they could bring this information to Paradox. I never documented my hours, but I would guess that I did approximately 80-100 hours of what I could only describe as cultural consultation work for free that was outside the contract work I was hired for. Let’s be clear: I did this willingly because I was passionate about the positive changes I wanted to see in this product, because I believed that Werewolf’s historic ills could be turned toward non-toxic representation.

Besides my actual words, such as naming the Ghost Council, and arguably the name Gale Stalkers came from a combination of names I pitched to Paradox after Winter’s Teeth was denied, and several sentences and paragraphs that I have seen so far that appear so close to what I originally wrote that you could imagine they were just edited versions, my largest contribution toward the final version of Werewolf: 5th Edition was this work. The only reason the offensive, appropriated names were changed were because of hours of my work to convince them it needed to happen. The reason that the Gale Stalkers aren’t just dead and gone: again, I pushed against this. The reason that Skin Dancers, Totem, and Metis will not appear as canonical titles? I pushed against their unwillingness to alter these things (see Karim’s defense of Wen**** Tribe name above).

Further, and this is the biggest reason I decided to write this article before seeing the final version of the book, I want to mention that I was also included in discussions with Hunters Entertainment to potentially be part of the art direction team, especially to oversee depictions of Indigenous characters, regalia, and art, to ensure that it would be represented either respectfully or not at all. I decided I needed to speak as soon as possible after the artistic portrayal of Tāme Iti appeared in the Glass Walkers preview without his permission. There are many arguments surrounding this issue and I am not going to address everything, but ultimately, I can tell you that had I remained as part of the art direction team, and saw that, I would have questioned it immediately. Even if I didn’t recognize Tāme Iti immediately, I would have asked what the source was on the depiction of moko in that piece, because I am aware that this is a sacred form of art–and I had already discussed wanting to make sure things like Crinos in headdresses didn’t appear in the book (as had often happened in previous editions, particularly on a certain white-skinned character whose name rhymes with Steals-the-Past).

As time working on this project went on, and I went through rounds and rounds of trying to convince Muammar and Paradox that it was important to not steal Indigenous identities, art, and stories, and that a greater effort needed to be put in powerful and empowering Indigenous representation, and I constantly ran into refusals and criticisms that were clearly hateful toward Indigenous identities and peoples, not to mention the push to represent Nazism as a major part of the game setting, I grew increasingly frustrated and restless with feeling like I was trying to work on a challenging project while also defending my right to exist as the person I am at every turn. Eventually I turned to another Indigenous TTRPG and game creator to ask for advice, and after a long and difficult discussion, I came to the conclusion that I was going to talk to the Hunters administration team and tell them that if Muammar kept using slurs and other anti-Indigenous language and attitudes, I was going to need to step off of this project, because it was harmful to me on a personal level. In furtherance of this point, I have been avoiding doing any contract work at all where I can tell that I am wanted for my specific cultural perspective ever since, because this situation was so harrowing for me.

Unfortunately, before I could have this conversation, after one final draft of Younger Brother and Bone Gnawers (which had its own issues, but that is not the point of this discussion), before we received any other specific feedback, the Hunters Entertainment administrators announced to the writing team that Paradox had decided to take the book in-house, and would no longer need our services.

The main point I would like to leave you with, besides these few specific quotes (out of dozens and dozens) that Muammar made that were anti-Indigenous, is that there is often a big call to have more BIPOC voices in various entertainment industries, so that both our stories, perspectives, and unique views on how the universe and life works, can be included; so that an industry that is historically, harmfully Eurocentric, might turn toward new, healthier, and inclusive directions. And I agree with this call for change, but I implore you to consider the conditions that BIPOC creators often have to work under: doing cultural/identity work and consultation for free as part of being present, being subject to vicious refusals of our experiences and perspectives, and straight-up having slurs lodged against our work. I want to see these changes in the industries we love, including the gaming industry, but currently the people who are in charge, who have the most power, are severely hostile to our work and our perspectives. This is why, for example, works like Coyote & Crow were done with an almost entirely Indigenous group of creators, and led by Indigenous creators, because trying to work for and with this ugly, hateful, and xenophobic group of people is so often exhausting, both mentally and spiritually, and because no good changes end up being made.

I am glad the harmful, appropriative terms were removed from the setting. I am glad I was part of the fight to make that real. I am not so glad that I was treated with hostility and racism by Muammar for the effort and love I put into this work, and I am not so glad that I will certainly be reviled by one of the two communities I did this work for–the gaming community, and certainly the people in power in this industry–and I am also not so glad that I didn’t have the opportunity to properly acknowledge how much of Werewolf’s base themes and setting are twisted and tied-up in Indigenous appropriation without giving the proper acknowledgments.

More than anything, I hope that this story will help you, the fans, realize that there is a lot of darkness in these communities, and they won’t change unless you hold their feet to the fire.

Ánaagodzįįhł

J.F. Sambrano

#decolonization#ttrpg#werewolves#writing#world of darkness#werewolf: the apocalypse#werewolf the apocalypse#mage: the ascension#vampire: the masquerade#changeling: the dreaming

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

This is going to make everyone mad and I've explained this before but latinas are the same as white girls even though latinos are not the same as white guys. Latinos are the same as indian guys and white guys are the same as black guys. And black girls are the same as asian girls and asian guys are the same as. Hmm. Now this is a paradox...

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paradox

A month or so ago I was on a train from Bangalore to Mangalore to attend the wedding of a good friend’s daughter.

I’m easily bored on of train journeys so brought along a book and some music settled into my seat by the window and began to read the book, The Power of paradox. Side note: if you have not read it I suggest it a a good read on how the spiritual meets the scientific.

I was so engrossed in the book I hardly noticed when someone came in to occupy the seat next to me. I realized it when I smelt the perfume of jasmine in her hair then I looked and was presently intrigued

A dusky beauty in a floweey long skirt and short top which barely held a pair of cute boobs, was the pretty young thing. Who from the look of it was a Mallu girl in her late 20’s to my 40’s Western Indian man.

We exchanged smiles and I returned to my book, she to arranging herself in the seat next to me.

I’m basically a bashful introvert, don’t talk to much , I was engrossed in my reading when I heard a soft voice, ,"I love the book you are reading I love how it describes the flow of power and how we can used it to help others . Out politician should all read it”

I laughed and the last comment. So far reading the book id never thought about it in this manner. Interesting take I thought to myself .

“Hi I’m Amaya” She said, we exchanged names and went on to talk about the weather. All the while I couldn’t help staring at her she had the warmest smoothest bronze skin Iv ever seen .

My gaze shifted from her face to her neck and then travelling all the way down to rest between a smoother cleavage . ‘Oh, I’d love some of that’ I thought to myself. She caught my stare smiled and I felt a tad embarrassed.

I returned to my book only to be jolted a while later as the train stopped as it does sometimes in the middle of nowhere.

Amaya arose from the seat, but the train jolted again, and she swung in my direction. I held her midway to prevent her from falling but as I did I felt some soft skin of her midriff

Electricity went thru me travelling all the way down to my balls. Have you felt that happen to you OMG ihorney insta horney, I thought to myself, did she feel it too?

Yes, she did cos as she left she winked at me in a way only a woman can wink at a man. She returned a couple of minutes later and this time I was checking me out staring at her ass and boobs

Tight hard full rack she had and a yum round ass that was accented by her skirt I was growing hard now. Again, she winked and this time she smiled too.

Oh, she sure knew I was checking her out and how. I now noticed she was enjoying it cos she adjusted her bra in front of me showing off a little more cleavage as I was watching her as if to say, ok oldie go ahead feast on me

When I saw that, I got really hot, and she smiled back sexily looking into my eyes as she did . Nothing was said yet everything was spoken

A few minutes later, hot and hard under my pants I I got up to go to the washroom as I passed her, she lifted her knees to get out of my way but actually dug them against my crotch and for a moment I froze and she only smiled coyly.

I walked off to the washroom area and moments later she followed me. Was this seduction? Yes, it was or so I thought

I stood at the end of the corridor at the door feeling the cold air. The next moment, I felt something touching my ass from behind.

It was her hand squeezing some ass. Then it slid around to hold my dick! I was rock hard now. My heart pounding, I was able to feel her body as she held it firmly against mine. I reached out to squeeze some boob when she fell away from me saying , “somebody will see us here Uncle.”

With that She disappeared into the loo leaving the door open behind. I read that as a signal to enter after her

As I entered, she grabbed my cock. I immediately kissed her lips forcefully. It was all so arousing and happened in a moment raw and animal .

She bit my lower lips and then I got wild. I sucked her lips and tongue, sucking and drinking up her nectar. All this while pressing her boobs really hard, I loved it.

Suddenly without warning she went down on her knees and opened me up and began to devour me. I had some precum which she sucked. Soon my whole dick was inside her mouth, then onto licking my balls. Sweet heaven to me.

I couldn’t wait any more, I was on fire. I turned her around Lifting her dress exposing the sexy smooth skin of her muscled thighs. I dropped her undies to her ankles only to expose a yummy bush that hid a delicious very wet puss from me.

Time for me to go down and kiss and lick her pussy, hairy is always a scent I love. She was dripping wet and white with cum and quivering too. I held her hand as I began to eat and she let out a soft long moan as if to welcome me into the perfumed heaven of her womanness.

There was no stopping me now, rising up I split her thighs placing my dick between my legs and started to stroke. Soon my dick was fully covered in her pussy juices she was delicious and tight, and she too began to move to my rhythm I could feel my cock rubbing her pussy walls and thighs.

We were moving in a frenzy now suddenly I realized we were being aided in this by the rocking movement of the train

Have you ever made out on a train. You must it’s the sexiest vehicle to make out on it adds a magical rhythmic fuel to the fire within.

Looking back I now know that this pretty young hot Mallu girl really wanted to be violated in that moving train by a stranger. Her fantasy too ?

Back to the story I bent her a little more exposing her sexy dripping pussy. And thrust my cock deep into her pussy. She was like, “Haaaaaaaaaaa”.

Encouraged I sunk cock into her throbbing hot rod inside pussy. Her young pussy was quivering with pleasure as she handled a stranger’s cock. This young pussy was getting fucked hard by a co-passenger’s wild hard cock. She was moaning now. I bit her shoulder and kneeded her boobs and squeezed her hard erect nipples. It was heaven!

I drilled her for 5 minutes growing from a slow deep thrust to shallower faster thrusts, her pussy was dripping wet and quivering with pleasure she came with a loud moan and waves of pleasure over took her.

I suddenly pulled out of her and came on her panties below. Ecstatic in the moment we were both drained and I slowly zipped up

As we left the loo she whispered into my ear, “Im gonna keep these panties as a trophy” and she smiled and then laughed and walked away

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

All my dead boy detectives ideas for rps or fanfics

(If they already exist as fanfics, please let me know so I can read them.)

If you are interested in any of these, just text me

Boarding school au

Essentially just Edwin and Charles as humans suffering in a very strict boarding school with cruel punishments. Also including this torture device from Esther and the chokey (this shelf punishment from Matilda) Edwin has been trough it all and tries to protect Charles from it as good as he can. And Charles manages to let them sneak out to the nearest city, which is London.

Gender swap au (modern au or like the show)

A story about the daughter of Charle’s sister (the comic Charles had a sister so this part would be canon) and the great great grandniece of Edwin. That go to the same school and start to help each other against bullies. And maybe even accidentally find a way to the dead boy detective agency.

Crystal x Niko

Anything about them really. Like give them the romance they deserve. Maybe they solve a case together. Or Crystal find Niko after she is believed dead (this one would be after season one I haven’t read the comics and this is I think a story line which is different then in the original material so all just headcanon) Crystal finding a shrink Niko who is with the dandelion gods and they get rescued by Crystal.

Just Charles and Edwin solving a case after season 1 and Charles discovers his feelings for Edwin. Also them being this funny old married couple

Charles rescuing Edwin from hell but more romantic and more adventurous with a thigh room (I just love the scene too much)

Charles teaching Edwin how to kiss properly, plot twist Edwin is already a natural talented good kisser (as ghost or as humans, setting before season 1 or before Edwin’s trip back to hell)

Baby and or toddler Edwin (set after season 1) (I will probably write this as a fanfic myself) taken

During a case Charles gets infected by something and gets set in a trance. While Edwin and Crystal try everything to find out how to help him, Charles’ mind gets send back in time to the Edwardian age. Somehow he is the new servant for the Payne family that is explicitly hired to take care of Edwin. Edwin is a fussy baby and shows strange behaviours due to his autism. His parents of course just want him to behave like a grown up already and are overwhelmed with how to take care of him. Luckily Charles isn’t from this time, that’s why he knows that first of all cocaine isn’t medicine that you can give a baby and he generally knows Edwin’s needs. (Disclaimer he doesn’t fall in love with little Edwin that would be weird, but he has the opportunity to give Edwin memories of at least a nice childhood before the horrible boarding school, and he to paradoxically time reasons, Edwin in the normal time can only remember a blurry version of this memory and having a very nice servant who was half Indian)

Charles and Edwin at the beach taken

Body swap (a classic but always fun)

Niko season 2 (Niko X Crystal)

A story in which Niko is old like in the end of dbd. She has been trough a lot of time troubles and needs to manage a lot to help the agency. Sadly she has no chance to tell them, she is not allowed to reveal her identity. But that might change once Crystal notices her feelings for the Niko she lost. Will she find out?

For reference to my rp rules and character preferences and how to contact, click here

Those are all I got for now. This list will be updated frequently depending if I come up with other ideas.

#dead boy detective agency#dead boy detective#dead boy detective netflix#dbd#dbd fanfic#dbd rp#dbd roleplay#dead boy detective rp#edwin payne#payneland#niko sasaki#niko x crystal#charles rowland#charles x edwin#crystal#ideas

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Great Indian Box Office Riddle: Muscle Mayhem vs. Martyrs' Valor

In the ever-bewildering world of the Indian box office, a new enigma emerges. The war hero epic “Sam Bahadur” stands with quiet dignity, yet it’s the rip-roaring “Animal” that gallops ahead, leaving a shimmering trail of muscled bravado and shattered records. What’s behind this phenomenon? Is it just our hunger for escape, or something more profound at play?**The Seduction of Escapism:**Life’s…

View On WordPress

#2023#action thrillers#Animal movie#audience preferences#blockbuster films#Bollywood paradox#box office trends#cinematic contrasts#cinematic escapades#entertainment vs reality#escapism in film#film industry analysis#genre loyalty#hero worship#Indian box office dynamics#Indian cinema#Indian cultural commentary#marketing in Bollywood#movie choices#Ranbir Kapoor#real-life heroes#Sam Bahadur#societal reflections in cinema#war biopics

0 notes

Text

The Maverick's Manifesto

A Proud Indian’s Satirical Cry for Bharat A Dream of Freedom: Tagore’s Call to Awake Where the mind is without fear and the head is held highWhere knowledge is freeWhere the world has not been broken up into fragmentsBy narrow domestic walls…Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.—Rabindranath Tagore, Gitanjali (1910) (Tagore, 1910) Rabindranath Tagore dreamed of a nation…

0 notes

Note

Hi miss Terra! I am attempting to go vegan for the first time and ngl its kinda intimidating. Lol any tips for a beginner/low budget ideas?

omg congrats 🎉 I went vegan in a cult when I was 2 (weaned off goats milk), went vegetarian the end of my teens, and back to vegan as a lactose intolerant young adult with little to no grocery money, tried meat shortly back but went back to vegan. so my diets have changed often but vegan is the most reliable and cheapest and healthiest. & best for the planet. The "meat paradox" is one of those things that really does weigh veryyyy hard on the psyche. + we are adapters and not natural omnivores like dogs are (flat teeth, little jaws, no claws, mild stomach acid), we have to disguise meat with plants like breads and spices to make it taste good to our herbivore brains for survival.

Anyways FIRSTLY! its much easier to socially do this in the west. Not just the freshness and cheapness of organic food in LA but even inner city Oakland and across the desert. Las Vegan restaurants were literally all over the city. But in the east coast, people in hospitality/restaurants in 2025 still believe vegans and vegetarians are the same. So it's a very easily modifiable diet. but you might have to have a discussion with the waiters like "no egg, please sub avocado & hummus" if you live here (I have ordered several vegan dishes that came with eggs or were cooked in tallow here).

Secondly, replacements aren't necessary, but they are healthier than animal products! If you are avoiding those new meaty lab foods, then try tofu, soy milk, bean cheese, ancient Chinese fake meats, black bean burgers, etc. those are my dailies. being vegan is just playing with food processors to manipulate proteins and a huge variety of plants to make textures and flavors and colors do different things. If you had kitchen science kits as a kid, you will have a lot of fun being vegan. But of course you can be lazy vegan too, nothing wrong with a yummy frozen burrito.

Thirdly! experiment with your grocery list. I have all my fave staples that I know will be eaten on a weekly auto-delivery but this took years to figure out: black beans, red lentils, tofu, basmati rice, stone ground tortilla, tomato sauce, pasta, sweet potatoes, normal potatoes, dino kale, plain soy milk, baby carrots, fruit, beyond sausage, any nondairy ice cream, any butter popcorn, miyoko cheese and butter. This would set you back $60 per haul (including delivery + tip at whole foods) but you can maximize fillers. making potatoes and rice and pasta and lentils your ~main entree stars~ will be much cheaper and better than eating a whole fried tofu lb in a day. I have eaten daily variations on these for over 6 years and still haven't run out of recipes to try :)

If you need ideas, these are my all time fave blogs and vlogs:

youtube

youtube

Ngl it is hard to find content creator vegans that aren't crunchy stinky hippies and stoners and anorexics and other people with health ocd who give themselves stress hives after touching bread lol. but you will find some really good food out there if you look :) gl and don't give up!

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Although repressed through a strict linguistic proscription, the institution of slavery proves to be a pervasive presence in the American Constitution. It is not even absent from the Declaration of Independence, where the accusation against George III of having appealed to black slaves takes the already noted form of having ‘excited domestic insurrections amongst us.' ... The Declaration of Independence ... included among George III’s most heinous crimes the fact that he had incited the ‘merciless Indian savages’ against the rebel colonists. In all three liberal revolutions the demand for liberty and justification of the enslavement, as well as the decimation (or destruction), of barbarians, were closely intertwined.

In conclusion, the countries that were the protagonists of three major liberal revolutions were simultaneously the authors of two tragic chapters in modern (and contemporary) history. If that is so, however, can the habitual representation of the liberal tradition — namely, that it is characterized by the love of liberty as such — be regarded as valid? Let us return to our initial question: What is liberalism?

... To render it explicable, the paradox must first be expounded in all its radicalism. Slavery is not something that persisted despite the success of the three liberal revolutions. On the contrary, it experienced its maximum development following that success: ‘The total slave population in the Americas reached around 330,000 in 1700, nearly three million by 1800, and finally peaked at over six million in the 1850s’. Contributing decisively to the rise of an institution synonymous with the absolute power of man over man was the liberal world. ... Correctly stated, in all its radicalism, the paradox we face consists in this: the rise of liberalism and the spread of racial chattel slavery are the product of a twin birth."

Domenico Losurdo, Liberalism: A Counter-History, trans. Gregory Elliot (2011)

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Author here. Meaning the real author, the living human holding the pencil, not some abstract narrative persona. Granted, there sometimes is such a persona in The Pale King, but that’s mainly a pro forma statutory construct, an entity that exists just for legal and commercial purposes, rather like a corporation; it has no direct, provable connection to me as a person. But this right here is me as a real person, David Wallace, age forty, SS no. 975-04-2012,1 addressing you from my Form 8829–deductible home office at 725 Indian Hill Blvd., Claremont 91711 CA, on this fifth day of spring, 2005, to inform you of the following:

All of this is true. This book is really true.

I obviously need to explain. First, please flip back and look at the book’s legal disclaimer, which is on the copyright page, verso side, four leaves in from the rather unfortunate and misleading front cover. The disclaimer is the unindented chunk that starts: ‘The characters and events in this book are fictitious.’ I’m aware that ordinary citizens almost never read disclaimers like this, the same way we don’t bother to look at copyright claims or Library of Congress specs or any of the dull pro forma boilerplate on sales contracts and ads that everyone knows is there just for legal reasons. But now I need you to read it, the disclaimer, and to understand that its initial ‘The characters and events in this book…’ includes this very Author’s Foreword. In other words, this Foreword is defined by the disclaimer as itself fictional, meaning that it lies within the area of special legal protection established by that disclaimer. I need this legal protection in order to inform you that what follows2 is, in reality, not fiction at all, but substantially true and accurate. That —The Pale King is, in point of fact, more like a memoir than any kind of made-up story.

This might appear to set up an irksome paradox. The book’s legal disclaimer defines everything that follows it as fiction, including this Foreword, but now here in this Foreword I’m saying that the whole thing is really nonfiction; so if you believe one you can’t believe the other, & c., & c. Please know that I find these sorts of cute, self-referential paradoxes irksome, too—at least now that I’m over thirty I do—and that the very last thing this book is is some kind of clever metafictional titty-pincher. That’s why I’m making it a point to violate protocol and address you here directly, as my real self; that’s why all the specific identifying data about me as a real person got laid out at the start of this Foreword. So that I could inform you of the truth: The only bona fide ‘fiction’ here is the copyright page’s disclaimer—which, again, is a legal device: The disclaimer’s whole and only purpose is to protect me, the book’s publisher, and the publisher’s assigned distributors from legal liability. The reason why such protections are especially required here—why, in fact, the publisher3 has insisted upon them as a precondition for acceptance of the manuscript and payment of the advance—is the same reason the disclaimer is, when you come right down to it, a lie.4

– David Foster Wallace, The Pale King

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Death Of A Horse

Les Mis Letters reading club explores one chapter of Les Misérables every day. Join us on Discord, Substack - or share your thoughts right here on tumblr - today's tag is #lm 1.3.8

“The dinners are better at Édon’s than at Bombarda’s,” exclaimed Zéphine.

“I prefer Bombarda to Édon,” declared Blachevelle. “There is more luxury. It is more Asiatic. Look at the room downstairs; there are mirrors [<i>glaces</i>] on the walls.”

“I prefer them [<i>glaces</i>, ices] on my plate,” said Favourite.

Blachevelle persisted:—

“Look at the knives. The handles are of silver at Bombarda’s and of bone at Édon’s. Now, silver is more valuable than bone.”

“Except for those who have a silver chin,” observed Tholomyès.

He was looking at the dome of the Invalides, which was visible from Bombarda’s windows.

A pause ensued.

“Tholomyès,” exclaimed Fameuil, “Listolier and I were having a discussion just now.”

“A discussion is a good thing,” replied Tholomyès; “a quarrel is better.”

“We were disputing about philosophy.”

“Well?”

“Which do you prefer, Descartes or Spinoza?”

“Désaugiers,” said Tholomyès.

This decree pronounced, he took a drink, and went on:—

“I consent to live. All is not at an end on earth since we can still talk nonsense. For that I return thanks to the immortal gods. We lie. One lies, but one laughs. One affirms, but one doubts. The unexpected bursts forth from the syllogism. That is fine. There are still human beings here below who know how to open and close the surprise box of the paradox merrily. This, ladies, which you are drinking with so tranquil an air is Madeira wine, you must know, from the vineyard of Coural das Freiras, which is three hundred and seventeen fathoms above the level of the sea. Attention while you drink! three hundred and seventeen fathoms! and Monsieur Bombarda, the magnificent eating-house keeper, gives you those three hundred and seventeen fathoms for four francs and fifty centimes.”

Again Fameuil interrupted him:—

“Tholomyès, your opinions fix the law. Who is your favorite author?”

“Ber—”

“Quin?”

“No; Choux.”

And Tholomyès continued:—

“Honor to Bombarda! He would equal Munophis of Elephanta if he could but get me an Indian dancing-girl, and Thygelion of Chæronea if he could bring me a Greek courtesan; for, oh, ladies! there were Bombardas in Greece and in Egypt. Apuleius tells us of them. Alas! always the same, and nothing new; nothing more unpublished by the creator in creation! <i>Nil sub sole novum</i>, says Solomon; <i>amor omnibus idem</i>, says Virgil; and Carabine mounts with Carabin into the bark at Saint-Cloud, as Aspasia embarked with Pericles upon the fleet at Samos. One last word. Do you know what Aspasia was, ladies? Although she lived at an epoch when women had, as yet, no soul, she was a soul; a soul of a rosy and purple hue, more ardent hued than fire, fresher than the dawn. Aspasia was a creature in whom two extremes of womanhood met; she was the goddess prostitute; Socrates plus Manon Lescaut. Aspasia was created in case a mistress should be needed for Prometheus.”

Tholomyès, once started, would have found some difficulty in stopping, had not a horse fallen down upon the quay just at that moment. The shock caused the cart and the orator to come to a dead halt. It was a Beauceron mare, old and thin, and one fit for the knacker, which was dragging a very heavy cart. On arriving in front of Bombarda’s, the worn-out, exhausted beast had refused to proceed any further. This incident attracted a crowd. Hardly had the cursing and indignant carter had time to utter with proper energy the sacramental word, <i>Mâtin</i> (the jade), backed up with a pitiless cut of the whip, when the jade fell, never to rise again. On hearing the hubbub made by the passers-by, Tholomyès’ merry auditors turned their heads, and Tholomyès took advantage of the opportunity to bring his allocution to a close with this melancholy strophe:—

“Elle était de ce monde ou coucous et carrosses

Ont le même destin;

Et, rosse, elle a vécu ce que vivant les rosses,

L’espace d’un mâtin!”

“Poor horse!” sighed Fantine.

And Dahlia exclaimed:—

“There is Fantine on the point of crying over horses. How can one be such a pitiful fool as that!”

At that moment Favourite, folding her arms and throwing her head back, looked resolutely at Tholomyès and said:—

“Come, now! the surprise?”

“Exactly. The moment has arrived,” replied Tholomyès. “Gentlemen, the hour for giving these ladies a surprise has struck. Wait for us a moment, ladies.”

“It begins with a kiss,” said Blachevelle.

“On the brow,” added Tholomyès.

Each gravely bestowed a kiss on his mistress’s brow; then all four filed out through the door, with their fingers on their lips.

Favourite clapped her hands on their departure.

“It is beginning to be amusing already,” said she.

“Don’t be too long,” murmured Fantine; “we are waiting for you.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

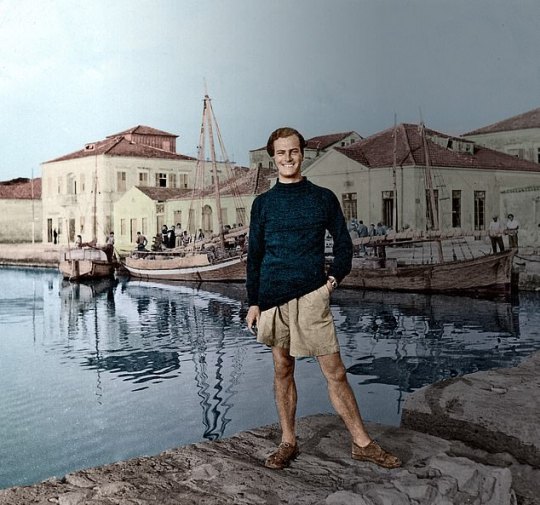

‘Pimpernel of the Hellenes’, ‘Major Paddy’, ‘Enchanted maniac’: Will the real Paddy Leigh Fermor please stand up?

Paradox reconciles all contradictions. - Patrick Leigh Fermor

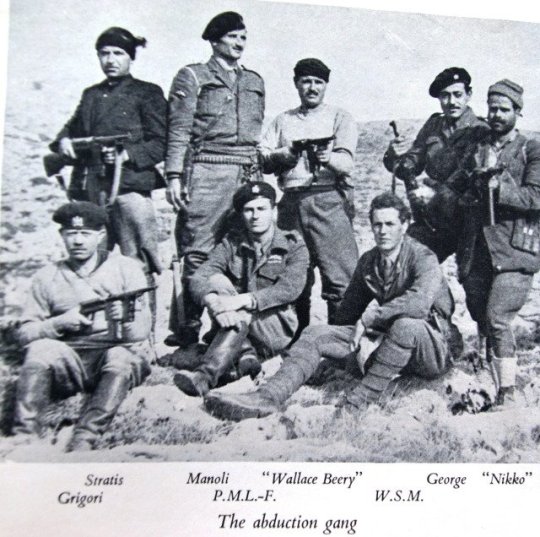

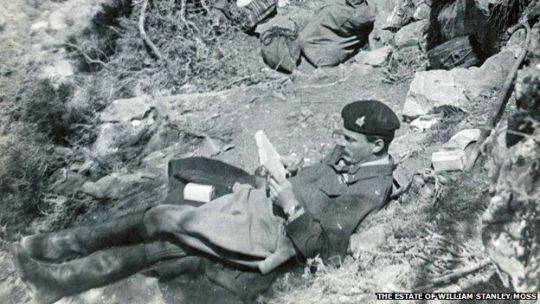

So one evening I was baby sitting my nephews and nieces here in our family chalet in Verbier, high up in the Swiss Alps. It was my turn to baby sit as the rest of my family enjoyed the fantastic classical music concerts and events showcased at the two week long Verbier 30th Festival. The little scamps had gone to bed and my father and I watched an old British war movie on DVD, ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ (1957). It was filmed by the legendary team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger based on the 1950 book ‘Ill Met by Moonlight: The Abduction of General Kreipe’ by W. Stanley Moss.

I’ve seen the film a couple of times before, but until now never really paid attention to where the title came from. My father said it was from Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream’ And so it was. In the play, Oberon, the king of the fairies and the Queen are having a fairly bitter drawn-out fight over custody of a changeling Indian child, and this is how the pissed off king greets the queen when they run into each other, “Ill met by moonlight, proud Titania”. Oberon is basically saying "Oh Lord, it's you..." and Titania's response is basically a flippant middle finger. One of the best modern reasons to read Shakespeare: to throw playful erudite shade at others.

Anyway, the historical background of the film is the German invasion of Crete in May 1941. After an intense ten-day battle, Allied troops were driven back across the island, and many were evacuated from beaches along the southern coast. Some Cretans and British officers took to the mountains to organise resistance against the occupying forces. The German occupation that followed was especially brutal. Dreadful reprisals followed every act of resistance. The German commander, General Müller, insisted on taking 50 Cretan lives for every German soldier killed; he became known as ‘The Butcher of Crete’.

As a Classicist side note, there had been a close association between Britain and Crete since the early 20th century, when archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans had uncovered the sensational remains of a Minoan palace at Knossos. The headquarters of the British archaeological school in Crete was a large villa alongside the site, known as Villa Ariadne. Several archaeologists, who knew the island and its people well, went underground after the German occupation to aid the Cretan resistance. Continuing in this tradition, scholar and travel-writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, who had got to know Greece in the 1930s, joined the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

During the German occupation, Major Paddy Leigh Fermor travelled to Crete three times to help organise local resistance against the hated German occupation. On the third occasion, in February 1944, he was parachuted in with a specific mission to kidnap German commander General Müller, to boost morale on Crete along with his erstwhile SOE comrade Capt. W. Stanley Moss MC (aka Billy Moss) of the Coldstream Guards. However, just after they parachute in, General Müller was replaced by General Heinrich Kreipe, who transferred from the Russian Front. Thinking that capturing one general was as good as another, Fermor merrily go ahead with the daring kidnap operation.

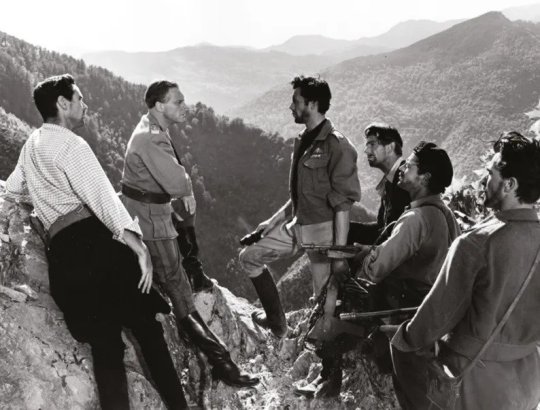

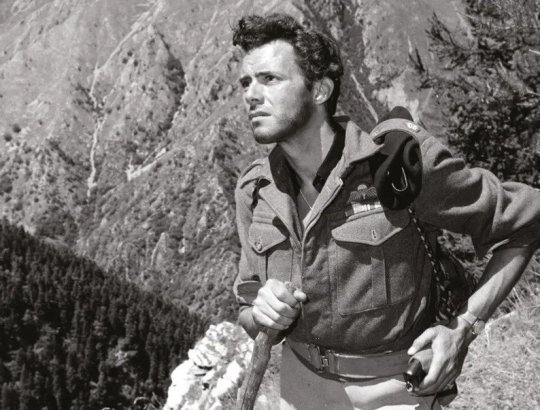

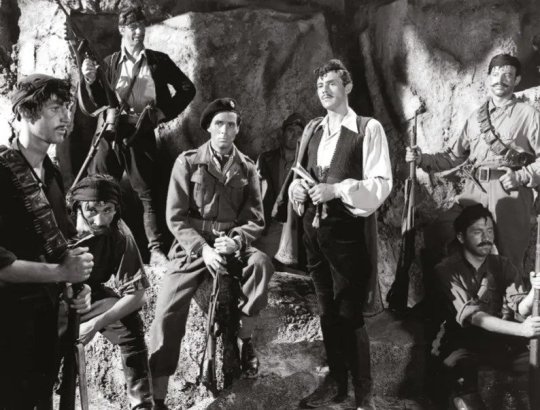

It’s at this point that the narrative of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ (1957) picks up. Dirk Bogarde plays Paddy Leigh Fermor, David Oxley plays Moss, and Marius Goring plays the taciturn German paratroop general. Blink and you’ll miss the late great Christopher Lee making a cameo appearance as a German officer in the dentist’s room scene.

The film naturally takes some liberty with the facts but it’s a cracking yarn of high adventure and drama. Xan Fielding, a close friend of Leigh Fermor from the SOE in Cairo, was taken on as technical adviser. The fact the film was shot in in the Alpes-Maritimes in France and Italy, and on the Côte d'Azur in France, far away from the craggy valleys and mountains of Crete itself. The director Michael Powell spent some time walking in Crete to get to know the island, but decided that, with the confused and volatile state of Greek politics, it was not suitable to film there.

Looking back years after he had directed it Powell didn’t think much of his own film. By contrast, Paddy Leigh Fermor, who was on set throughout the film shoot, was very happy with Bogarde’s portrayal of him with Byronic glamour. Watching the movie again ‘Ill Met by Moonlight’ remains a classic and stands out from many British war films of the 1950s because of its realism. The British SOE men and the Cretan guerrillas look absolutely right for their parts. It is dramatic and full of suspense while filled with much boyish humour.

I was disappointed with one notable omission in the film that did happen in real life. According to Patrick Leigh Fermor, at dawn one day during the journey across the mountains, General Kreipe was looking at the mist rising from Mount Ida and began to recite, in Latin, the opening lines of Horace’s ninth ode:

Vides ut alta stet nive candidum Soracte nec iam sustineant onus silvae laborantes geluque flumina constiterint acuto?

Behold yon Mountains hoary height, Made higher with new Mounts of Snow; Again behold the Winters weight Oppress the lab’ring Woods below: And Streams, with Icy fetters bound, Benum’d and crampt to solid Ground

(John Dryden 1685)

Leigh Fermor picked up on the General, and recited the remaining stanzas of the Ode. ‘Ach so, Herr Major,’ said Kreipe when Leigh Fermor had finished. Both men were amazed to realise they shared a classical education and a love of ancient Latin poetry.

Leigh Fermor later wrote that it was as though the war had ceased to exist for a moment, as ‘We had both drunk from the same fountains before.’ It brought captor and captive together with a strange bond. The scene was not reproduced in the film, as Powell and Pressburger probably thought it would make the men sound too academic for a popular cinema audience.

Leigh Fermor and Kreipe met again in the early 1970s, on a Greek television show, and got on famously together. The General said Leigh Fermor had treated him chivalrously as a captive. They remained friends until Kreipe’s death.

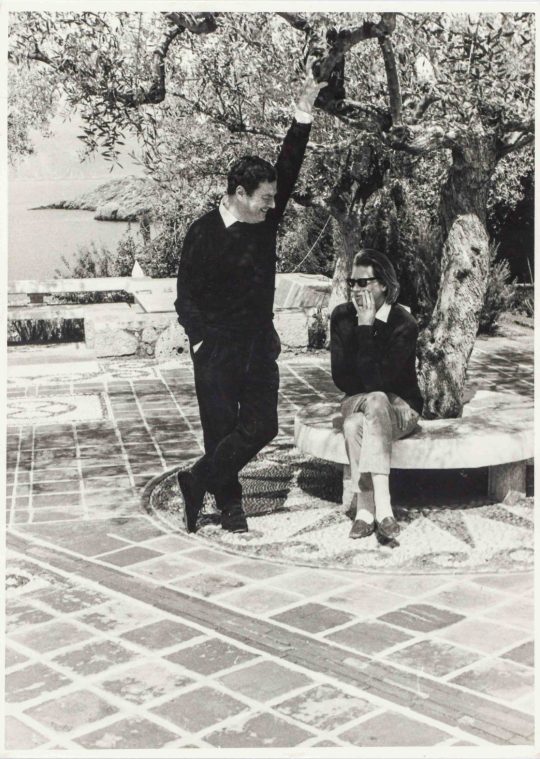

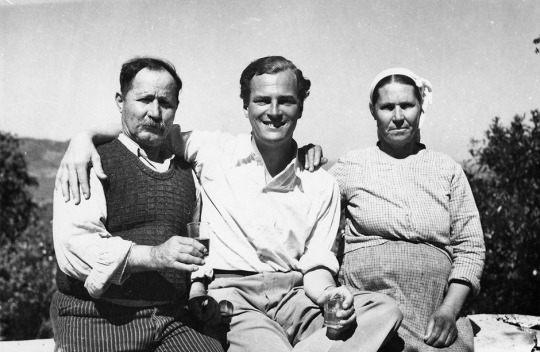

After sharing a late night drink with my father after the film, I began to muse on the figure of Paddy Leigh Fermor, a family friend and someone I met along with his wife, Joan, as a little girl. My grandparents, and especially my grandmother, knew Paddy briefly from their days during and after the Second World War.

My father shared a few stories about him when he and my mother visited his beautiful home in Greece, where even at his advanced age he remained the most generous of hosts and the most outrageous flirt.

One of my memories was getting into his battered old Peugeot in the drive way and trying to drive it when my feet could barely touch the pedals. It wouldn’t have mattered in any case as the brakes didn’t work as he cheerfully said later as we careened around a dirt road to go around the mountains for a drive.

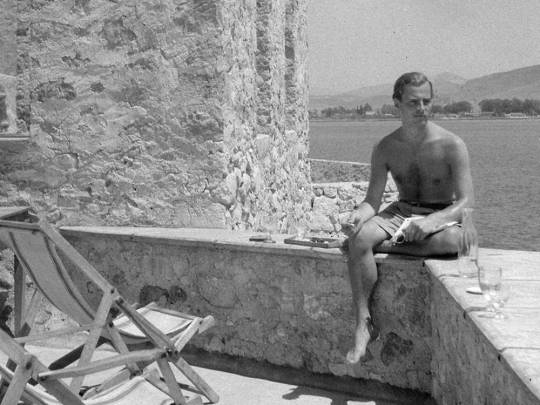

Many years later in April 2022, I tried to visit the home of the late Patrick and Joan Leigh Fermor - a sort of pristine shrine to their memory that one can also stay in any of the rooms as a vacation rental - in the coastal fishing village of Kadarmyli in the Peloponnese, as part of a hiking and mountaineering sojourn around Greece with ex-Army friends. We couldn’t stay there as it was already rented out to other guests, and so we stayed higher up the mountain in a villa, but we swam in front of the Fermor’s home which was on the water’s edge.

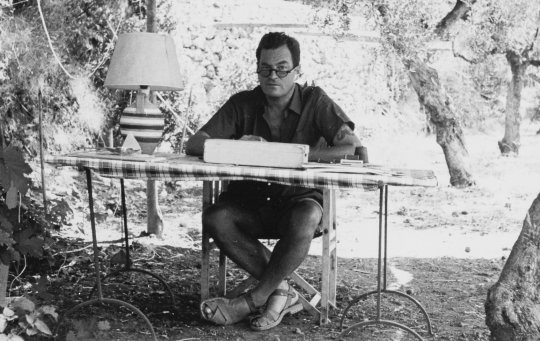

You could never put your finger on Paddy Leigh Fermor. He hid behind his gift for telling yarns, and pulling Ancient Greek verses out of the thin air, as well as boisterously singing local Greek songs with a drink in his hand.

Even after his death in 2011, the question keeps nagging as to who was Paddy Leigh Fermor?

The Dirk Bogarde film too seems to ask, who exactly is the ‘real’ Patrick Leigh Fermor - or the real anyone? Taking its title from a Shakespearian play concerned with dreams and disguises, magic and power, ‘Ill Met By Moonlight’ is all about questions of identity.

Under the film credits, we see Dirk Bogarde in uniform; then, unexpectedly, we see him in the flamboyant outfit of a Cretan hill-bandit. A title informs us that Major Leigh Fermor was also known by the Greek code-name “Philidem.” In other words, there are two of him (at least), and on one level the adventure the film is about to unfold reflects a conflict in his personality. It’s a conflict shared, unknowingly, by his Nazi opposite number, the fierce, arrogant General Kreipe (an unlikely “proud Titania,” but it’s true that he “with a monster is in love” – the monster of Nazism). Kreipe’s human side is so rigorously repressed by the demands of war and “glory” that he is genuinely unaware of it; ironically, this humanness, which constitutes the true manhood of this Teuton warrior, is revealed by a boy (equivalent to Shakespeare’s Indian Prince?) - who, in turn, is the most grown up person in the movie.

If “Philidem” appears under the credits, caped and open-shirted, a romantic dream-figure out of an operetta or a storybook, he is first seen in the film proper as a coarser, more down-to-earth version of the same thing – an ordinary Cretan peasant in a shabby suit, waiting for a bus. When he makes contact with the Resistance, his personality fragments further.

To some, he is the mystical Philidem, Pimpernel of the Hellenes and righter of wrongs. To others he is “Major Paddy,” the happy-go-lucky Englishman of popular movie myth conducting war as if it were a branch of amateur theatricals, a gentleman adventurer relying on breeding to get him through and making fun of the whole business. To Bill Moss (David Oxley), the newly arrived junior officer sent to assist him, he is the cool, fast-thinking professional soldier. And to himself? In his quietly passionate defence of Cretan life and culture, he seems someone else again: a scholar and aesthete outraged by the barbarism and folly of war, and by the moronic arrogance shown by his captive toward the Cretan people.

Whatever his persona, Leigh Fermor is a chameleon who never seems to change very radically in himself. Perhaps because he has this quality of seeming all things to all men – and being those things - he remains unfazed by the monolithic might of the German military machine. Fluent in Greek, he can also speak German like a German and is easily able to assume another disguise, that of a faceless Nazi officer. Although he and Moss make fun of themselves - “If only I had a monocle!” muses Moss when Leigh Fermor tells him he “looks like an Englishman dressed like a German, leaning against the Ritz bar” - they are able to effect the kidnapping with an ease that seems appropriately Puckish. General Kreipe is ignominiously thrust onto the floor of his own limousine, gagged, and sat upon by a couple of the peasants he so despises. Kreipe’s rage is compounded by his firm conviction that he has been snatched by “amateurs” - a belief Leigh Fermor and Moss slyly make no objection to, knowing how it will gnaw at his already shaky Master Race self-confidence.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, aka Major Paddy, aka Philidem, in the film’s closing moments, is far from being self-assured intellectual or dashing amateur adventurer or legendary outlaw of the hills. He’s just a tired man who wants to go home and rest up. “How do you feel?” asks Moss. “Flat” is the reply. “You look flat!” says Moss. “I know how I’d like to look …” murmurs Leigh-Fermor wistfully. Moss knows what he’s going to say, and joins in the litany: “Like an Englishman dressed like an Englishman – and leaning against the Ritz bar!” It’s easy to imagine them ordering drinks at that renowned watering-hole with all the suavity required by this little fantasy.

Still, the film’s last images of Crete receding in the distance, until all we can see is the sea, suggests that maybe Major Paddy’s heart is really back in those hills in the “fair and fertile” land that has become as much a Powellian landscape of the mind for us as the studio-built Himalayan convent of ‘Black Narcissus’ or the monochrome Heaven of ‘A Matter of Life and Death’. And, as the film POV closing shots departs both Crete and this film, I began to think that being “dressed like an Englishman and leaning against the Ritz bar” would, for Patrick Leigh Fermor constitute yet another disguise. After all, he said he was of Irish aristocratic stock.

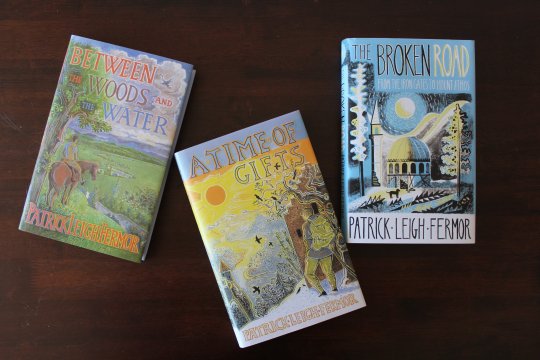

Traveller and writer Paddy Leigh Fermor is best known for two events. He’s known for leading the commando group in occupied Crete to kidnap General Kreipe. But he is also known for the boy who, at a mere 18 years old, set off with little money and a lot of nerve in 1933 to walk from the Hook of Holland to Constantinople.

Patrick Leigh Fermor was, in the words of one of his obituaries, a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene. Self-reliance and derring-do were lessons learnt from the cradle. When Fermor’s geologist father was posted to India, he and his wife left the infant with family in Northamptonshire and did not return until his fourth birthday. In retrospect, he took great delight in being sent to a school for difficult children and getting himself expelled from the King’s School, Canterbury, when he was caught holding hands with a greengrocer’s daughter eight years his senior. His school report infamously judged him ‘a dangerous mix of sophistication and recklessness’.

Sharing a flat in Shepherd’s Market, one of Mayfair’s seedier corners, Leigh Fermor schooled himself in literature, history, Latin and Greek.

He honed his character with the company of extraordinary people and the words of great writers - he had a prodigious memory for prose as well as poetry. He befriended literary lions such as Sacheverell Sitwell, Evelyn Waugh and Nancy Mitford. His travels began aged ‘eighteen-and-three-quarters’ when he rejected Sandhurst Royal Military College in order to walk the length of Europe from Hook of Holland to Constantinople. He took with him Horace’s Odes and the Oxford Book of Verse though Leigh Fermor could recite Shakespeare soliloquies, Marlowe speeches, Keats’s Odes and as he modestly put it ‘the usual pieces of Tennyson, Browning and Coleridge’ from memory.

Leigh Fermor was then a self-made man in the most literal sense.

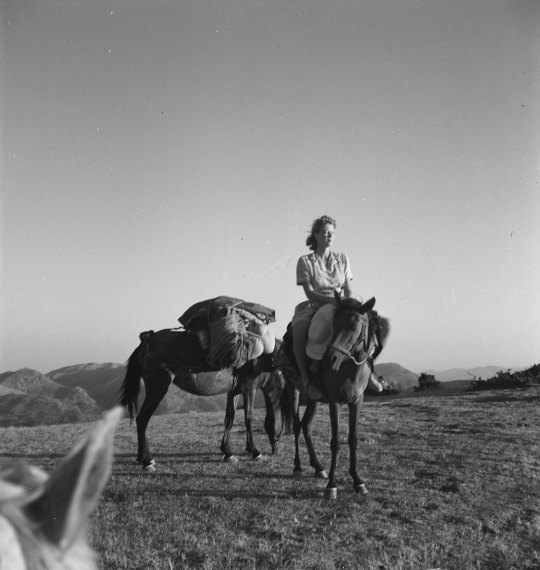

Setting off from England in 1933, Fermor resolved to traverse Europe living like a hermit; sleeping in bars and begging for food. But his manly charms and boyish good looks found him being passed like a favourite godson from Schloss to palace by European nobility and he developed a lifelong penchant for aristocratic company. I his own words, ‘In Hungary, I borrowed a horse, then plunged into Transylvania; from Romania on into Bulgaria’. Having reached Constantinople in January 1935, Fermor continued to explore Greece where he fought on the royalist side in Macedonia quelling a republican revolution. In Athens Leigh Fermor met Balasha Cantacuzene, a Romanian countess with whom he fell in love. They were living together in a Moldovan castle when World War Two was declared.

Fluent in Greek, Leigh Fermor was posted as a liaison officer in Albania. Recruited as a Special Operations Executive (SOE), he was shipped from Cairo to German-occupied Crete where he lived disguised as a shepherd in the mountains for two years. On his third expedition to Crete in 1944, Leigh Fermor was parachuted alone onto the island and made connections in the Cretan resistance movement. While waiting for his compatriot Captain Bill Stanley Moss to land by water from Cairo, Leigh Fermor hatched a plot to kidnap German Commander General Heinrich Krieple. He liaised comfortably with Cretan partisans and bandits to pull off one of the war’s greatest coups de théâtre.

Disguised as German soldiers, Leigh Fermor and Moss stopped Krieple’s car at an improvised check point en route back to Nazi HQ in Knossos. Abandoning the General’s car after a two-hour drive, Leigh Fermor left a note indicating that the kidnappers were British so that there wouldn’t be reprisals against Cretan nationals. When the abduction of the unpopular commander was discovered, a German officer in Heraklion allegedly said ‘well, gentlemen, I think this calls for champagne’. It turns out that General Kreipe was despised by his own soldiers because, amongst other things, he objected to the stopping of his own vehicle for checking in compliance with his commands concerning approved travel orders. It’s why for instance the German troops, both in the film and in real life, dare not stop the General’s car as it drove through the check points at Heraklion.

Krieple was evacuated and taken to Cairo and Leigh Fermor entered the annals of World War Two’s most devil-may-care heroes. With characteristic panache, when he was demobbed Leigh Fermor moved into an attic room at the Ritz paying half a guinea a night. But his first travel book, ‘The Traveller’s Tree’, was not about the European odyssey or the Cretan escapades and centred on Leigh Fermor’s adventures in the Carribbean. Published in 1950, ‘The Traveller’s Tree’ was an inspiration for Ian Fleming’s second James Bond novel ‘Live and Let Die’ (1954).

As a host and house guest, Paddy Leigh Fermor was much sought-after. At one of his parties in Cairo, he counted nine crowned heads. He was a confirmed two-gin-and-tonics before lunch man and smoked eighty to 100 cigarettes a day. His party pieces included singing ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ in Hindustani and reciting ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ backwards. In Cyprus while staying with Laurence Durrell, Leigh Fermor apparently stunned crowds in Bella Pais into silence by singing folk songs in perfect Cretan dialect. As Durrell wrote in ‘Bitter Lemons’ (1957), ‘it is as if they want to embrace Paddy wherever he goes’.

He struck up a partiuclar friendship with the famous Mitford sisters, especially Deborah Mitford, later ‘Debo’, the Duchess of Devonshire. It was at the Devonshires’ Irish estate Lismore Castle that ‘Darling Debo’ and ‘Darling Pad’ met and began to correspond. A characteristic letter from the Duchess in 1962 reads ‘The dear old President (JFK) phoned the other day. First question was ‘Who’ve you got with you, Paddy?” He’s got you on the brain’ to which Fermor replies of a broken wrist ‘Balinese dancing’s out, for a start; so, should I ever succeed to a throne, is holding an orb. The other drawbacks will surface with time’.

After the war he travelled widely but was always drawn back to Greece. He built a house on the Mani peninsula - which had been, significantly, the only part of Magna Graecia to resist Ottoman colonisation since the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Before his death in 2011 at the age of 96, he wrote some of the most acclaimed travel books of the 20th century.

His books contain some of the finest prose writing of the past century and disprove Wilde's maxim that "it is better to have a permanent income than to be fascinating".

Charm, self-taught knowledge and enthusiasm made up for the lack of a university degree or a private income. His teenage walk across Europe and subsequent romantic sojourn in Baleni, Romania, with Princess Balasha Cantacuzene are proof enough of that. But the difficulty of capturing such an unconventional and glamorous life is made harder by the certainty that Fermor was an unreliable narrator.

He was also an infuriatingly slow writer. Driven by a life-long passion for words yet hampered by anxiety about his abilities, Leigh Fermor published eight books over 41 years.