#Indian Treaties

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Treaty Between the United States and the Quapaw Indians Signed at St. Louis, August 24, 1818.

Record Group 11: General Records of the United States Government

Series: Indian Treaties

File Unit: Ratified Indian Treaty 96: Quapaw - St. Louis, August 24, 1818

Image description: Detailed map of the area of Arkansas River and Mississippi River, with boundaries of red and blue; with an eagle on top left carrying olive branch in its beak; a Native American with a peace pipe on the left, presumably of the Quapaw tribe, pointing to the inscription:

Map of the Territorial Limits of the Quapaw cession

Compiled & Laid down by Rene Paul

August. 1818

Transcription:

[image: Detailed map of the area of Arkansas River and Mississippi River, with boundaries of red and blue; with an eagle on top left carrying olive branch in its beak; a Native American with a peace pipe on the left, presumably of the Quapaw tribe, pointing to the inscription:

Map of the Territorial Limits of the Quapaw cession

Compiled & Laid down by Rene Paul

August. 1818]

A treaty of Friendship, Cession and Limits made and entered into this twenty fourth day of August Eighteen hundred & Eighteen, by and be-

tween [between] William Clark and Auguste Chouteau, Commissioners on the part and behalf of the United States of the one part, and the Undersigned Chiefs,

and Warriors of the Quawpaw Tribe or Nation, on the part and behalf of this said Tribe or Nation of the other part. -

Art: I: The Undersigned Chiefs and Warriors for themselves and their s'd [said] Tribe or Nation do hereby acknowledge themselves to be under the protection of the United States, and

of no other State, Power, or Sovereignty whatsoever.

Art: II: The Undersigned chiefs and Warriors, for themselves and their said Tribe or Nation do hereby, for an in consideration of the promises and stipulations herein after named, Cede

and relinquish to the United States forever, all the Lands within the following boundaries, viz: Beginning at the mouth of the Arkansas River, thence extending up the Arkan-

saw [Arkansaw] to the Canadian fork and up the Canadian fork [to its source, thence south to Big Red river and down] that river to the Big raft, Thence a direct line so as

to strike the Mississippi River, thirty Leagues in a straight line below the mouth of Arkansaw, together with all their claims to land East of the Mississippi, and north of the Ar-

kansaw river, included within the couloured lines, 1, 2, and 3 on the above map: - with the exception and reservation following: that is to say, the tract of country bounded as follows;

Beginning at a point on the Arkansaw river opposite the present post of Arkansaw, and running thence a due South West course to the Washita river, thence up that river to the

[in pencil, faint] mouth of the Saline [/] Saline fork, and up the Saline fork to a point from whence a due North East course would strike the Arkansaw river [insert] at the little rock [/] and thence down the right bank of the Arkan-

[in margin, circled] 2-9 [/] saw to the place of beginning, which S'd [said] tract of land, last above designated and reserved, shall be surveyed and marked off, at the Expense of the United States, as

any State or Nation, without the approbation of the United States, first had and obtained.

Art III; It is agreed between the United States, and the said Tribe, or Nation, that the individuals of the S'd [said]Tribe or Nation shall be at liberty to hunt within the Territory by them

ceded to the United States, without hindrance or molestation so long as they demean themselves peacefully and offer no injury or annoyance to any of the citizens of the United

States, and until the S'd [said] United States may think proper to assign the Same, or any same or any portion thereof, as hunting grounds to other friendly indians.

Art IV; No Citizen of the United States, or any other person shall be permitted to settle on any of the lands hereby allotted to and reserved for the S'd [said] Quawpaw Tribe, or Nation, to live and

hunt on; Yet, it is expressly understood and agreed on by and between the parties aforesaid, that at all times the citizens of the United States, shall have the right to travel

and pass freely without toll or exaction through the Quawpaw reservation, by such roads or routes as now are, or hereafter may be, established.

Art V; In consideration of the cession and stipulations aforesaid the United States do hereby promise, and bind themselves to pay and deliver to the s'd [said] Quawpaw Tribe, or Nation, immediately

upon the execution of this Treaty, Goods and Merchandise to the value of Four Thousand Dollars, and to deliver, or cause to be delivered to them yearly, and every year, Goods and Mer-

chandise [merchandise] to the value of One Thousand Dollars to be estimated in the city, or place in the United States, where the same are procured, or purchased.

Art VI; Least the friendship which now exists between the United States, and the Said Tribe, or Nation should be interrupted by the misconduct of individuals, it is hereby agreed, that

for injuries done by individuals, no private revenge, or retaliation shall take place, but instead thereof, complaints shall be made by the party injured to the other. - By the Tribe, or

nation aforesaid, to the Governor, Superintendant of Indian Affairs, or some other person, authorized or appointed for that purpose, and by the Governor, Superintendent, or other person authorized

to the [crossed out] said [/] Chiefs of the S'd [said] Tribe, or Nation. And it shall be the duty of the Said Tribe or Nation, upon complaint being made as aforesaid, to deliver up the person or persons against whom the complaint is made, to the end that he or they may be punished agreeably to the Laws of the State or Territory where thee offence may have been committed; And in like manner, if any robbery,

violence, or murder, shall be committed on any indian, or Indians belonging to the Said Tribe, or Nation, the person, or persons so offending shall be tried, and if found guilty,

punished in like manner as if the injury had been done to a white man._ And it is further agreed that the chiefs of the said Tribe or Nation shall to the utmost of their power

exert themselves to recover horses or other property which may be Stolen from any citizen or citizens of the United States, by any individual or individuals of the Said Tribe, or

Nation, and the property so recovered shall be forthwith delivered to the Governor, Superintendent, or other person authorized to receive the same, that it may be restored

to the proper owner. And in cases where the exertions of the Chiefs shall be ineffectual in recovering the property stolen, as aforesaid, if sufficient proof can be obtain-

ed [obtained], that such property was actually stolen by an indian, or indians belonging to the Said Tribe, or Nation, a sum equal to the value of the property which has been stolen, may

be deducted by the United States from the Annuity of S'd [said] Tribe or Nation. And the United States hereby guarantee to the individuals of the Said Tribe, or Nation

a full indemnification for any horse, or horses, or other property which may be taken from [insert] them [/] by any of their citizens; Provided, the property so stolen cannot be recovered, and

that sufficient proof is produced that it may actually stolen by a citizen or citizens of the United States.

Art VII; This Treaty shall take effect and be obligatory on the contracting parties, as soon as the same shall have been ratified by the President of the United States,

by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.

[left column]

Done at St Louis in the presence of

[signed] R. Wash Secretary to the Commission

[signed] R. Paul Col. M. M.

C. I.

[signed] Jn Ruland Sub Agent & c

[signed] R Graham Ind Agt

[signed] M Lewis Clark

[signed] J. T. Honore Ind Intpr

[signed] Joseph Bonne Interpreter

[signed] Julius Pescay

[signed] Stephen Julian, U.S. indn interpt.

[signed] James Loper

[signed] William P Clark

[middle column]

[signed] Wm Clark

[signed] Aug. Chouteau [seal]

Kra-ka-ton, or }

the dry man } his + mark [seal]

Hra-da-paa, or }

the Eagles Bill } his + mark [seal]

Ma-hra-ka, }

or Buck Wheat } his + mark [seal]

Hon-ka-daq-ni his + mark [seal]

Wa-gon-ka-datton his + mark [seal]

Hra-das-ka-mon-mini, }

or the Pipe Bird } his + mark [seal]

Pa tonq di, or the }

approaching Summer } his + mark [seal]

Te hon ka, or the }

Tame Buffaloe } his + mark [seal]

[right column]

Ha-mon-mini }

or the night walker } his + mark [seal]

Washing-tete-ton }

or mocking bird bill } his + mark [seal]

Hon-te-ka-ni his + mark [seal]

Ta-ta-on-sa or }

the whistling wind } his + mark [seal]

Mozate te } his + mark [seal]

#archivesgov#August 24#1818#1800s#Native American history#American Indian history#Indigenous American history#Quapaw#Indian treaties

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝗥𝗲𝘃𝗶𝗲𝘄: "𝗪𝗵𝗲𝗿𝗲𝗮𝘀" 𝗯𝘆 𝗟𝗮𝘆𝗹𝗶 𝗟𝗼𝗻𝗴 𝗦𝗼𝗹𝗱𝗶𝗲𝗿 -

For me, Soldier's plea "How can I convince you?" has a futility to it after this passage of time, the ignorance of sacrifice, this othering, this falseness of language, this phenomenon of justification. This poetry may not always be beautiful; it is always profound.

#literature#bookworm#read read read#books#book reviews#poetry#whereas#layli long soldier#indigenous literature#indian treaties#lakota poetry#lakota

1 note

·

View note

Text

i heard recently that most people in my tribe are eligible for Indian status in Canada, which doesn't give you citizenship automatically but gives you most of the rights of being a citizen like living and working there so looking at the next 4 years i think that might be the move...

#i'm not 100% sure if i qualify personally i need to read up more on the indian act#theres also the jay treaty i've sorta heard about that too but mostly from canadians#not sure how/if it works for americans ?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

My mom saw this White looking lady selling stuff like beadwork I think on facebook & when my mom asked her if she was Native, this lady was like "I'm a status Indian under treaty 13!"

#re: there basically is no treaty 13. the numbered treaties go up to 11 not 13#there WAS a treaty 13 as the Toronto purchase but you cant be a status Indian under this treaty & afaik its mostly defunct

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

French and Indian War: The Treaty of Paris ended the war and France ceded Quebec to Great Britain on February 10, 1763.

#French and Indian War#Treaty of Paris#10 February 1763#anniversary#Canadian history#Quebec City#Québec#original photography#vacation#summer 2018#architecture#landscape#St. Lawrence River#countryside#Trois-Rivières#Château Ramezay#Halte de Sainte-Geneviève-de-Berthier#Notre-Dame Cathedral Basilica#Montréal#Halte des Piliers#Saint-Grégoire-le-Grand#Lake Pohénégamook#travel#tourist attraction#landmark#cityscape#Canada

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Chagos Islands to Mauritius represents a pivotal moment in a long-standing dispute, it also raises essential questions about justice, identity, and the role of affected communities in determining their own futures.

Know more 👆🏻

#British Indian Ocean Territory#Chagos Islands#Chagos Islands treaty#Chagossian identity#Chagossian Voices community#breaking news#ireland

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

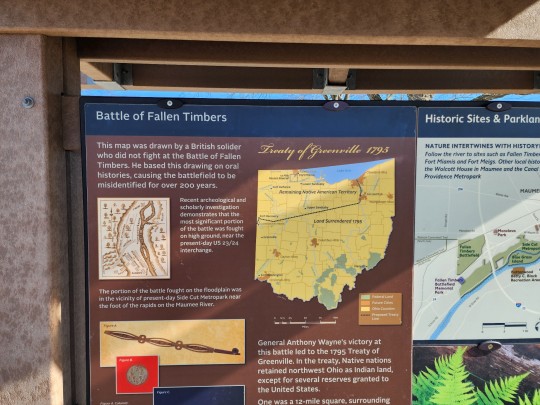

After a lot of driving back and forth on Anthony Wayne Trail—named for General "Mad" Anthony Wayne himself, Revolutionary War hero and apparently a Founding Father—we made it to the Fallen Timbers Battlefield and monument.

Our first stop (by accident) was the actual battlefield site, which has a plaque, a few nature trails, and a visitor's center that wasn't open.

I know this is the battlefield site, because it's right next to a mall called "The Shops at Fallen Timbers." Yeah, they built a shopping center adjacent to/basically on top of one of the most important sites commemorating the Northwest Indian War (1785-1795), which saw the United States defeating a confederacy of Indigenous peoples and their British allies, opening a huge territory to US settlers.

It prefigures the War of 1812, which involved the same Chippewa, Lenape, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Miami, Shawnee, Wyandot, United States, and British belligerents. The 1795 Treaty of Greenville, which followed Fallen Timbers, set aside large tracts of northwest Ohio for Indigenous use.

It was edifying to read the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, which names the Indigenous nations I've included from a list on a monument at the site as well as "Eel Rivers, Weas, Kickapoos, Piankeshaws, and Kaskaskias." (Make of the spelling what you will, because the Treaty even spells European names wrong e.g. Fort Lawrence instead of Fort Laurens). The Treaty carves out a number of exceptions for land in the territory ceded to U.S. forts, and a guarantee of free passage between the forts.

Obviously this is very significant in the War of 1812, which mostly took place in a region of Ohio that was granted to Indigenous people not even a generation earlier. William Henry Harrison, military leader and politician, was known for his manipulative and deceptive agreements that kept putting lands into U.S. hands without honoring past treaties. It's a lot of interconnected conflicts between opponents who are already familiar with each other (Harrison, Tecumseh, and Procter come to mind, but it goes even deeper).

I feel a lot of sympathy for the settlers and even the U.S. military personnel engaged in these conflicts; but this park is a rather one-sided presentation of a complicated history. There is an attempt at including more of the Indigenous perspectives, which is something that I think needs a lot more attention in Western War of 1812 history. They wouldn't make a monument like the 1929 Anthony Wayne memorial again.

Fallen Timbers Battlefield is confusing to locate because the historic site with the 1929 monument is also in the wrong place. Only in 1995 did researchers uncover the real location of the battle (near the present-day shopping center).

The GPS took me on some unnecessary adventures, but as you can see, people have been getting this wrong for over 200 years.

We didn't go walking on the trails (at either park), although it was a warm sunny day. I would like to do that in the future. I think you can still see some of the actual fallen timbers (trees knocked over by a tornado) on the real battlefield 230 years later!

#us history#ohio#military history#northwest indian war#settler colonialism#indigenous#war of 1812#anthony wayne#battle of fallen timbers#treaty of greenville#it was also a wild day to be driving in maumee#i did get to go on a cool bridge over the river#old northwest#1790s#shaun talks#i love living in this history-rich area altho it can be a little dark#described

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"... the discourse of criminalization fails to capture the complexity of the relationship between the First Nations and the criminal law, because it directs our gaze only to the criminalized and away from others. As with Peaychew, many forms of engagement with the criminal law are described in this book. I have found cases in which First Nations individuals laid Informations against white men as well as men from their own communities, alleging different types of offences, such as theft and assault; cases in which Aboriginal women and girls appeared as informants and witnesses and charged white and Métis men, as well as men from their own communities, with forms of sexual interference with, or “carnal knowledge” of, them or their daughters; cases in which only a handful of First Nations women and girls appeared as accused persons, charged with or implicated in the theft of small items, such as a tea kettle from an empty house, a silver spoon from an empty schoolhouse, the clothes that First Nations children were wearing when they ran away from the industrial school, or, in the case of Betsy Horsefall and Benjamin Gordon, in the theft of a horse that Betsy said was hers.

Perhaps the strongest argument of this book concerns the form and content of law and reflects my long-standing commitment to the importance of attending to the specificity of different legal forms and the relationship between them. The book represents a sustained call for a more precise definition and use of the concept of criminalization, one in which distinctions between criminal law as a legal form and other forms of law are recognized, and that seeks to apprehend the contexts, circumstances, and sites in which actions and practices of Aboriginal peoples were prosecuted – as crimes or as regulatory or other statutory offences.

Some of the historical literature reveals a certain imprecision with respect to the definition and scope of criminal law. Many scholars adopt a wide approach to criminal law, in which all legal forms that have an air of compulsion, coercion, or sanction are coloured with a criminal law brush. Recent work examining the efforts of the Canadian state to restrict and curtail traditional forms of Aboriginal expression and activity, including dances and ceremonies, hunting, and fishing, uses the language of criminalization to characterize them. For instance, a now iconic exemplar of criminalization is said to be found in amendments to Indian Act in 1884 that prohibited particular kinds of dances and celebrations (such as the potlatch in British Columbia). For the Plains First Nations, the most expansive and relevant Indian Act restrictions were introduced in an 1895 amendment to s. 114 that prohibited dances involving giveaways and wounding or mutilation. Although historical evidence implicates the police as well as Indian Department officials in efforts to enforce the prohibitions and prosecute these offences, the historical evidence also indicates that these prohibitions were resented, resisted, and ignored as well as only occasionally and unevenly enforced (indeed, they were almost unenforceable) on the ground. In any event, these provisions fell outside the ambit of criminal law.

Admittedly, caution is in order here. Interdisciplinary scholarship in socio-legal studies argues for a broader notion of crime – one that challenges the historical preoccupation with crimes of individual wrongdoers and the historical neglect of crimes of the powerful, including the state and corporate actors and institutions, as well as the historical neglect of the experience of the environment, culture, and entire communities as victims of forms of seldom criminalized violence. If one proceeds with criminal law narrowly construed (excluding some of the coercive provisions of the Indian Act, for instance), one may risk proceeding with too narrow an understanding of crime. The importance of critical engagement with a self-referential notion of true “criminal law” cannot be denied. The content of criminal law is neither universal nor transhistorical; and, importantly, criminalization is not self-evident.

The process of criminalization occurs when people are criminally prosecuted and convicted for forms of conduct that have become defined by the state as crimes. It may encompass the extension of criminal law over formerly non-criminal behaviour, or it may involve the systemic targeting, overpolicing, and criminal prosecution of particular groups and communities for particular kinds of offences. Inevitably, it is intended to express and enforce social denunciation for socially injurious conduct. In legal scholarship, it is important to be attentive to the analytic distinction between legal and extra-legal forms of compulsion and legal coercion, between prohibition and regulation, and between committal and conviction, in order to precisely identify the nature of the law under discussion.

To insist upon specificity in the scope and definition of criminal law need not lead one to an uncritical acceptance of the legitimacy of its norms. It is important, however, to be attentive to questions of form, content, and diversity of legal instruments deployed by the state, many of which contain offences but which do not involve the denunciation and sanction normally associated with criminal law.

An important and related line of inquiry concerns the way in which legal historians have or have not addressed the specificity of the two legal regimes of the Indian Act and the criminal law, and the sites of intersection between the Canadian government’s “Indian policy” and the criminal law component of its national policy. The Indian policy of the Canadian government intensified over the last two decades of the nineteenth century with the introduction of increasingly oppressive amendments to the Indian Act.

In recent work examining the efforts of the Canadian state to restrict and curtail traditional forms of Aboriginal expression and activity, the language of criminalization has been invoked. For some scholars, the prohibition of some forms of religious ceremonies and dances, together with special practices and policies, such as the pass system, offer evidence of the nature of the Canadian state’s treatment of Aboriginal peoples. For the most part, these initiatives occurred under the legislative auspices of the Indian Act or the administrative initiatives of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs and his Indian Agents in the field. It has become commonplace in some of the literature to refer to the criminalization of Indians and Indian religious celebrations.

There are other voices in the historical literature that offer different emphases. It is significant, in my view, that one recent study expressly devoted to law, colonialism, and First Nations addresses the struggle over the right to fish and the regulatory framework, including offences, of the Fisheries Act. Nowhere in Douglas Harris’s careful study of the restriction and regulation of the Aboriginal fishers of British Columbia does he characterize the process as one of criminalization. Similarly, Katherine Pettipas’s equally rigorous study of the interference with and prosecution of First Nations ceremonies on the Prairies characterizes government policy as one of regulation.

We can also, however, find instances and forms of NWMP resistance to federal Indian policy. Pettipas’s carefully researched study of the regulation and repression of indigenous religious ceremonies on the Prairies provides irrefutable evidence of the legalized campaign of repression of forms of religious celebrations. Nevertheless, although her work demonstrates the lengths to which the government went to circumscribe and curtail these forms of religious expression, including the prosecution and imprisonment of a number of Aboriginal celebrants, she also notes that some members of the NWMP actually ignored orders to prevent dances and instead facilitated the events. Both Pettipas and John Jennings cite Stipendiary Magistrate Macleod’s refusal to convict Indians who had been arrested for performing a sun dance. Macleod, a former commissioner of the NWMP, is said to have delivered “a scathing rebuff” to the police who had made the arrests, likening their conduct to having made an arrest in a church.

In sum, Pettipas’s study of the regulation of Plains Indian religious ceremonies evinces a nuanced analysis, showing the uneven and contradictory tensions that accompanied this damaging legislative initiative. She reminds her readers that only some forms of dances and celebrations (those involving “giveaways”’ and “piercings”) were prohibited by the Indian Act; that because of its vagueness, the police often declined to enforce the infamous s. 114 of the Indian Act; and that even Indian officials were of the view that a prosecution should be undertaken only as a last resort. It is also clear that some First Nations people were prepared to “test” the strength and limits of the law.

In conclusion, the “self-evidence” of criminalization is a trap for the unwary. Criminal law becomes all law; criminalization becomes an umbrella that covers all manner of legal forms (from liquor violations, to hunting and fishing offences, to the Indian Act, and sometimes even criminal law). In critical legal historical work on criminal law, criminal law is depicted “in one dimensional terms” – criminal law “acts against” subordinate people (women, indigenous peoples, workers, and so on). This is the dominant account in the critical literature – inequalities of class, race, and gender are reinforced as the criminal law bears down on those brought before it. And yet some of the literature may also be read to offer a more relational notion of criminal law, even in a colonial context."

- Shelley A. M. Gavigan, Hunger, Horses, and Government Men: Criminal Law on the Aboriginal Plains, 1870-1905. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press for the Osgoode Society, 2012. p. 19-22

#criminal law#criminalization#legal history#historiography#settler colonialism in canada#canadian criminal justice system#first nations#indigenous people#indigenous history#treaty 4#treaty 6#plains first nations#canadian prairies#reading 2024#academic quote#history of crime and punishment in canada#canadian history#indian act

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

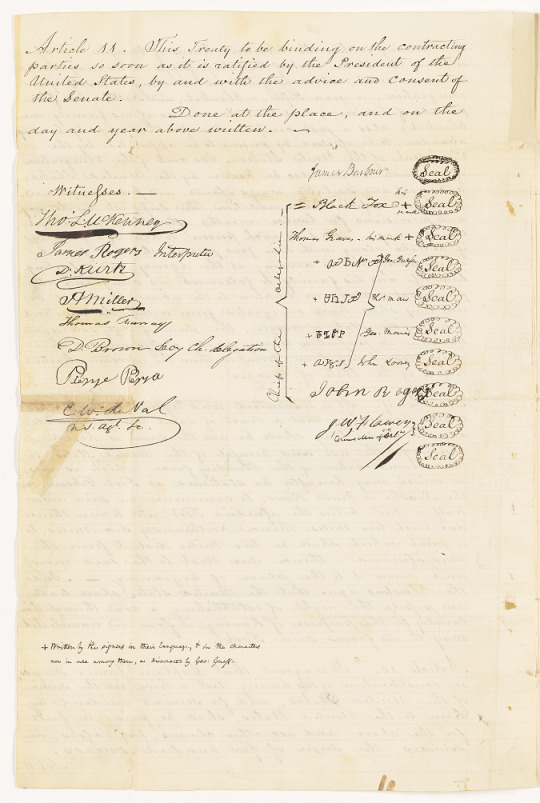

Treaty Between the United States and the Western Cherokee Indians Signed at Washington, DC on May 6, 1828 (page 1, signature page).

Record Group 11: General Records of the United States Government

Series: Indian Treaties

File Unit: Ratified Indian Treaty 152: Western Cherokee - Washington, DC, May 6, 1828

Transcription:

[blue /red ribbon down left side]

19-2

Articles of a Convention concluded at the City of

Washington this Sixth day of May in the year of our Lord one

thousand eight hundred and twenty eight, between James Barbour

Secretary of War, being specially authorized therefor by the

President of the United States, and the undersigned Chiefs

and head men of the Cherokee nation of Indians, west of

the Mississippi, they being duly authorized and empowered

by their Nation.

Whereas it being the anxious desire of the Government

of the United States to secure to the Cherokee Nation of Indians,

as well those now living within the limits of the Territory of

Arkansas, as those of their friends and Brothers who reside

in States east of the Mississippi, and who may wish to join

their Brothers of the West, [underlined] a permanent [/underlined home, and which

shall, under the most solemn guarantee of the United States,

be, and remain theirs forever - a home that shall never, in

all future time be embarrassed by having extended around

it the lines, or placed over it the jurisdiction of a Territory

or State, nor be pressed upon by the extension, in any way,

of any of the limits of any existing Territory or State; and

Whereas the present location of the Cherokees in Arkansas, being

unfavorable to their present repose, and tending, as the past

demonstrates, to their future degradation and misery; and

the Cherokees being anxious to avoid such consequences, and

yet not questioning their right to their lands in Arkansas,

as secured to them by Treaty, and resting also upon the

pledges given them by the President of the United States,

and the Secretary of War, of March 1818, and 8th October

1821, in regard to the outlet to the West, and as may be

seen on referring to the records of the War Department,

Still, being anxious to secure a permanent home, and

to free themselves, and their posterity from an embarrassing

connexion with the Territory of Arkansas, and guard

themselves from such connexions in future; and

whereas it being important, not to the Cherokees only,

but also to the Choctaws, and in regard also to the

question which may be agitated, in the future, respect

-ing the location of the latter, as well as the former,

within the limits of the Territory or States of Arkansas,

as the case may be, and their removal therefrom; and

to avoid the cost which may attend negotiations to rid

the Territory or State of Arkansas whenever it may

become a State, of either, or both of those Tribes, the

parties hereto, do hereby conclude the following articles:

Viz:

[page 2]

[left page]

Article 11. This Treaty to be binding on the contracting

parties so soon as it is ratified by the President of the

United States, by and with the advice and consent of

the Senate.

Done at the place, and on the

day of year above written. ~

[signed] James Barbour [SEAL]

[right column]

Black Fox, his x mark [SEAL]

Thomas Graves, his x mark [SEAL]

+ [signature in characters] Geo: Guess [SEAL]

+ [signature in characters] Thos. Maw [SEAL]

+ [signature in characters] Geo: Marvis [SEAL]

+ [signature in characters] John Looney [SEAL]

[signed] JJohn Rogers [SEAL]

[signed] JJ. W. Flawey [SEAL]

Counsel Men of Del.

[/right column]

[left column]

Witnesses. -

[signed] Thos. L. McKenney

[signed] James Rogers Interpreter

[signed] D. Kurtz

[signed] H. Miller

[signed] Thomas Murray

[signed] D. Brown Secy Ch. Delegation

[signed] Pierye Pierya,

[signed] E.W. Duval

U. S. Agt. &c.

[/left column]

+ Written by the signers in their language, & in the characters

now in use among them, as discovered by Geo: Guess.

#archivesgov#May 6#1828#1800s#Native American history#Indigenous American history#Cherokee#Western Cherokee Nation#Indian treaties

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

in case you were worried about being out of touch or uninformed, dw, you're doing better than the lady who asked me at work today with no awareness whatsoever where all the native americans went when the colonies became states

#i work at a museum btw it wasnt out of nowhere#but when i said 'oh the trail of tears' SHE STILL DIDNT KNOW WHAT I WAS TALKING ABOUT. MA'AM.#she also fully used Indians instead of native American so like. sighs#was a real fun tour#would also like to say this was specifically about my state violating treaties in order to push the border of the state

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

On August 15, 1824...

The first HBC Governor west of the Rockies made his first tour of the forts with a note to himself in mind: the potential profit in Christian conversion of his newly acquired, autonomous Indigenous trading partners. On August 15, 1824, George Simpson, Governor of Hudson’s Bay Company “North” (mostly west), left Ottawa for the Oregon Territory. His mission was to make the newly acquired…

#Christian mission#Colony of British Columbia#Fort Simpson#HBC Governor Simpson#Indian Residential School#Oregon Treaty#Origin of BC#Sovereignty

0 notes

Text

Discovering Bhutan: The Last Shangri-La

Nestled in the Eastern Himalayas, Bhutan, known as the “Land of the Thunder Dragon,” is a country that beckons travelers with its pristine landscapes, vibrant culture, and profound spirituality. As one of the world’s last remaining Buddhist kingdoms, Bhutan offers a unique blend of ancient traditions and modern sensibilities. In this travel guide, we’ll explore Bhutan’s history, political…

View On WordPress

#" is a country that beckons travelers with its pristine landscapes#adventure#africa#all international tourists (excluding Indian#all international tourists need a visa arranged through a licensed tour operator#and a guide#and a guide. This policy helps manage tourism sustainably and preserves the country&039;s unique culture. Currency and Bank Cards The offic#and archery. Safety Bhutan is one of the safest countries for travelers. Violent crime is rare#and Buddha Dordenma statue. Punakha: Known for the majestic Punakha Dzong#and cultural insights to help you plan an unforgettable journey. Brief History of Bhutan Bhutan&039;s history is deeply intertwined with Bu#and Culture Religion: Buddhism is the predominant religion#and experiencing a traditional Bhutanese meal are top cultural activities. Is it safe to travel alone in Bhutan? Bhutan is very safe for sol#and Kathmandu. Infrastructure and Roads Bhutan&039;s infrastructure is developing#and Maldivian passport holders) must obtain a visa through a licensed Bhutanese tour operator. A daily tariff is imposed#and red rice. Meals are typically spicy and incorporate locally sourced ingredients. Culture: Bhutanese culture is characterized by its emph#and respectful clothing for visiting religious sites. Bhutan remains a land of mystery and magic#and stupas are common sights. Food: Bhutanese cuisine features dishes like Ema Datshi (chili cheese)#and the locals are known for their hospitality. However#and vibrant festivals. Handicrafts#Bangladeshi#Bhutan#Bhutan offers a unique blend of ancient traditions and modern sensibilities. In this travel guide#Bhutan promises an experience unlike any other. Plan your journey carefully#Bhutan was never colonized. The country signed the Treaty of Sinchula with British India in 1865#but English is widely spoken and used in education and government. What should I pack for a trip to Bhutan? Pack layers for varying temperat#but it covers most expenses#but it&039;s advisable to carry cash when traveling to remote regions. Top Places to Visit in Bhutan Paro Valley: Home to the iconic Paro T#but it&039;s advisable to carry cash when traveling to rural regions. What are the top cultural experiences in Bhutan? Attending a Tshechu#but they offer stunning views. Religion#comfortable walking shoes

0 notes

Text

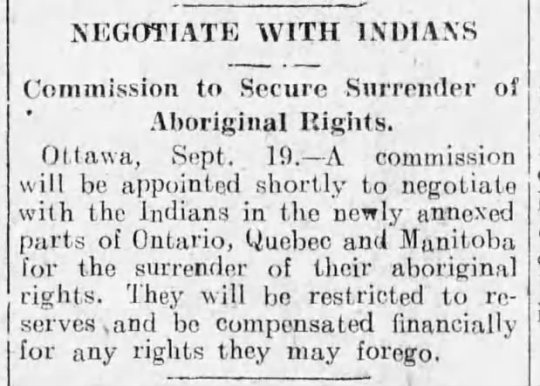

"NEGOTIATE WITH INDIANS," Weekly British Whig (Kingston, Ont.) September 23, 1912. Page 1. ---- Commission to Secure Surrender of Aboriginal Rights. ---- Ottawa, Sept. 19. - A commission will be appointed shortly to negotiate with the Indians in the newly annexed parts of Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba for the surrender of their aboriginal rights. They will be restricted to reserves and be compensated financially for any rights they may forego.

#indian act#parliament of canada#department of indian affairs#settler colonialism in canada#first nations#land expropriation#first nations reserve#indigenous history#indigenous rights#indigenous people#northern ontario#treaty system#northern manitoba#northern quebec#canadian history

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Native American Reservations, Explained.

youtube

I and all my neighbors here in western Hamilton County, Ohio, live on land taken from the Shawnee.

#Youtube#american indian#native american#first nations#treaties#indian#indian reservation#indian reservations#bureau of indian affairs

0 notes

Text

Treaty Between the United States and the Pawnee Republic signed at St. Louis, June 20, 1818.

Record Group 11: General Records of the United States Government

Series: Indian Treaties

File Unit: Ratified Indian Treaty 94: Pawnee Republic - St. Louis, June 20, 1818

Transcription:

A Treaty of Peace and Friendship made and concluded by and between William Clark, and

Auguste Chouteau, Commissioners of the United States of America, on the part and behalf of Said

States of the one part; And the Undersigned Chiefs and Warriors of the Pawnee Republic on the part

and behalf of their tribe; of the other part.

The parties being desirous of Establishing Peace and Friendship between the United States and the

said Tribe, have agreed to the following Articles. -

Art: 1st; Every injury or act of hostility by one or either of the contracting Parties, against the other, shall be mutually forgiven and forgot.

Art: 2nd; There shall be perpetual Peace and Friendship between all the citizens of the United States of America, and all

the individuals composing the said Pawnee Tribe.

Art: 3rd; The undersigned Chiefs and Warriors for themselves and their said Tribe, do hereby acknowledge themselves to be

under the protection of the United States of America and of no other nation, Power, or Sovereign whatsoever.

Art: 4th; The undersigned Chiefs and Warriors for themselves and the tribe they represent, do moreover promise and oblige them-

selves to deliver up, or to cause to be delivered up to the authority of the United States (to be punished according to law)

each and every individual of the said tribe who shall at any time hereafter, violate the stipulations of the Treaty,

this day concluded between the said Pawnee Republic, and the said States.

In Witness Whereof; the said William Clark, and Auguste Chouteau Commissioners as aforesaid and the

Chiefs and Warriors aforesaid have hereunto subscribed their names and affixed their seals, this Twentieth day of

June, in the year of our Lord, one thousand Eight hundred and Eighteen, and of the independence of the United States the forty second.

[left column]

Done at Saint Louis}

in the presence of }

[signed] R. Wash Sectry of the Commission

[signed] T. Paul Col. M. M.

C. Interpreter

[signed] R. Graham I. A. Ill. Ter.

[signed] John O'Fallon Capt R. Regt

[signed] John Ruland Sub. Agt. Translator

[signed] A. L. Papin interpreter

[signed] J. T. Honore Id. Iptr.

[signed] S. Julian U. S. indn. interpr

[signed] Wm. Grayson

[signed] Josiah Ramsey

[signed] John Robedout

[right column]

William Clark [seal w/ red ribbon]

Aug. Chouteau [seal w/ red ribbon]

Pe-ta-he-ick } x [seal w/ red ribbon]

the Good Chief}

Ra-rn-le-share } x [seal w/ red ribbon]

the Chief Man }

She-rn-a-ki-tare } x [seal w/ red ribbon]

the First in the War Party }

She-te-ra-hiate } x [seal w/ red ribbon]

the Partisan Discoverer }

Te-a-re-ka-ta-caush x [seal w/ red ribbon]

the Brave }

Pa, or the Elk x [seal w/ red ribbon]

Te-ta-wi-ouche } x [seal w/ red ribbon]

Wearer of Shoes }

#archivesgov#June 20#1818#1800s#treaties#Indian Treaties#Pawnee#Native American history#American Indian history#Indigenous American history

22 notes

·

View notes