#Immigration Appeals Tribunal

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

A Comprehensive Guide to NZ Visa Appeals

Applying for a visa to New Zealand is an exciting step toward experiencing the natural beauty, vibrant culture, and numerous opportunities the country has to offer. However, not all visa applications are approved, and when an application is declined, it can be disheartening. Fortunately, New Zealand provides avenues for appealing visa decisions. This guide will walk you through the process of appealing a visa decision in New Zealand, including key steps, important considerations, and what to expect during the process.

Understanding the Visa Appeal Process in New Zealand

When a New Zealand Visa Application is denied, the applicant may have the right to appeal the decision. The appeal process is overseen by the Immigration and Protection Tribunal (IPT), an independent body responsible for reviewing decisions made by Immigration New Zealand (INZ). The IPT can consider appeals on various grounds, including humanitarian reasons or if the applicant believes that the decision was made based on incorrect information.

Types of Visa Appeals

Residence Class Visa Appeals: If your residence visa is declined, you may appeal to the IPT on the grounds that the decision was incorrect or that you have special circumstances that warrant consideration. This could include family connections in New Zealand or unique personal circumstances.

Temporary Entry Class Visa Appeals: While there is generally no direct right to appeal for temporary visas (such as visitor or student visas), there may be exceptions under certain conditions. For example, if you believe that a mistake was made in the processing of your application or that your circumstances have changed, you may request a reconsideration by INZ.

Steps to Appeal a Visa Decision

1. Review the Decision

Before proceeding with an appeal, carefully review the decision letter from INZ. This document will outline the reasons for the visa denial and provide important information about your rights to appeal. Understanding the basis for the decision is crucial in preparing a strong appeal.

2. Determine Eligibility to Appeal

Not all visa decisions are eligible for appeal. For instance, certain temporary visas do not carry the right to appeal directly. It's essential to confirm your eligibility before proceeding. If your visa type does allow for an appeal, the decision letter will specify the timeframe within which you must lodge your appeal.

3. Prepare Your Appeal

Preparing an effective appeal involves gathering supporting documents, evidence, and arguments that address the reasons for your visa refusal. Key elements to include in your appeal may involve:

Documentation: Provide all relevant documents that support your case. This might include additional evidence that was not available during your initial application.

Personal Statement: Write a detailed personal statement explaining why you believe the decision was incorrect or why you should be granted the visa despite the initial refusal.

Legal Advice: It is highly advisable to seek legal advice or assistance from an immigration advisor. A professional can help you understand the legal grounds of your appeal and assist in presenting your case effectively.

Lodging the Appeal

Once your appeal is prepared, it needs to be lodged with the IPT. This must be done within the timeframe specified in your decision letter, typically within 42 days of receiving the decision. Appeals can be lodged online, by mail, or in person.

1. Filing the Appeal

Online: The IPT has an online submission system that allows you to lodge your appeal electronically.

Mail: You can send your appeal documents by mail to the IPT's address provided in the decision letter.

In Person: If you prefer, you can lodge your appeal in person at the IPT's office.

2. Pay the Appeal Fee

Lodging an appeal incurs a fee, which must be paid at the time of submission. The fee is non-refundable, regardless of the outcome of your appeal. It's important to include the correct payment information or method when filing your appeal to avoid any delays in processing.

After Lodging the Appeal

1. Tribunal Review

Once your appeal is lodged, the IPT will review your case. This process involves a thorough examination of your initial application, the reasons for the refusal, and the new evidence or arguments you have submitted. The IPT may request additional information from you or hold a hearing where you can present your case in person.

2. Hearing (If Applicable)

In some cases, the IPT may schedule a hearing to allow you to present your case in detail. During the hearing, you will have the opportunity to explain your situation, present your evidence, and respond to any questions from the Tribunal members. It's essential to be well-prepared for this hearing, as it could significantly impact the outcome of your appeal.

3. Decision

After reviewing your case, the IPT will make a decision on your appeal. The Tribunal will either:

Allow the Appeal: If the appeal is successful, the Tribunal will overturn the original decision, and your visa may be granted.

Dismiss the Appeal: If the appeal is unsuccessful, the original decision will stand, and you will need to consider other options, such as reapplying for the visa or exploring alternative visa categories.

Important Considerations

1. Legal Representation

Given the complexity of the appeal process, it is strongly recommended to seek professional advice or legal representation. An immigration advisor or lawyer can help you navigate the process, prepare your appeal, and represent you during the hearing.

2. Timeframes

The appeal process can take several months, depending on the complexity of your case and the IPT's workload. It's crucial to be patient and ensure that all documents and information are submitted on time.

3. Alternative Options

If your appeal is not successful, you may still have other options, such as reapplying for a different visa category or seeking a ministerial intervention under exceptional circumstances. Consulting with an immigration advisor can help you explore these alternatives.

Conclusion

Navigating the NZ visa appeal process can be challenging, but with careful preparation and understanding of the system, you can present a compelling case. Whether you are appealing a residence or temporary visa decision, following the proper procedures and seeking professional guidance can increase your chances of success.

Remember, when preparing for your visa application or appeal, it's vital to meet all NZ Visa Requirements and submit accurate and complete documentation. Whether you’re applying for the first time or appealing a decision, understanding the process is key to achieving your immigration goals.

By staying informed and proactive, you can better navigate the complexities of New Zealand's immigration system and work towards a successful outcome.

#NZ Visa Appeals#New Zealand Visa Appeal Process#Immigration New Zealand#Immigration and Protection Tribunal#Visa Application Rejection#NZ Visa Appeal Steps#New Zealand Immigration Law#Residence Visa Appeal NZ#Temporary Visa Appeal NZ#Visa Denial Appeal NZ#NZ Visa Requirements#NZ Visa Application Process#New Zealand Visa Advice#Visa Refusal New Zealand#Immigration Appeals NZ

0 notes

Text

#immigrants#immigration directive#australia#direction 110#visa cancellations#immigration minister andrew giles#appeal tribunals

0 notes

Text

Appealing a Decision at the First-Tier Tribunal

If your UK visa or immigration application has been denied, our expert immigration appeal lawyers can evaluate the viability of appealing to the First-tier Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber). We will assist in preparing your immigration appeal and provide representation at your appeal hearing. Understanding the First-Tier Tribunal Immigration and Asylum Chamber (FTTIAC) Navigating…

View On WordPress

#Appeal#Appeal Home Office decision#Appeal To First Tier Tribunal#Best Immigration Solicitors London#DJF Solicitors#First Tier Tribunal Appeal#Home Office#Home Office Updates#Immigration & Asylum First Tier Tribunal#Immigration Lawyers London#Immigration Policy#lexlaw solicitors & advocates#Lexvisa#London Immigration Solicitors#UK Immigration#UK Immigration Advice#UK Immigration Policy#UK Immigration Solicitors/ Lawyers

0 notes

Text

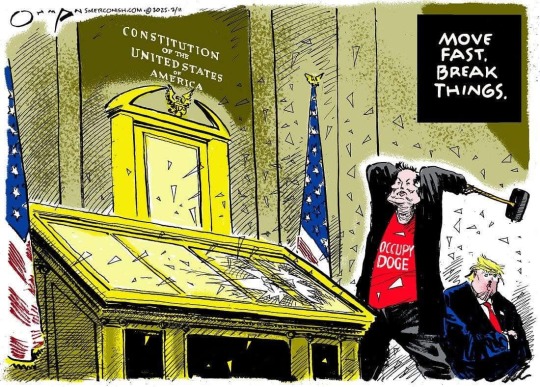

Jack Ohman, Tribune Content Agency

* * * *

The power of a single voice.

February 14, 2025

Robert B. Hubbell

We have all been in a situation where an audience sits in awkward silence as a loudmouth makes rude and offensive comments that disrupt the event. People look nervously at one another for social cues to confirm what everyone is thinking: “This guy is a jerk. Someone should tell him to shut up.”

And then a single voice says, “Be quiet. Sit down. You are ruining it for everyone.” And then a chorus arises, “Sit down! Boo! Hiss!” The power of a single voice can unleash the strength of collective action.

Being the first mover is risky and (depending on the situation) dangerous when the stakes are high. It takes courage and moral conviction. On Thursday, the acting US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Danielle R. Sassoon, demonstrated courage and moral conviction. She refused to dismiss the indictment against New York Mayor Eric Adams—as she had been ordered to do by Emil Bove, the acting US Deputy Attorney General.

Danielle Sassoon explained her decision not to dismiss the charges against Eric Adams in a carefully crafted, respectful, thoughtful letter, which is here: Letter from Danielle R. Sassoon to AG Pamela Bondi.

Everyone should read portions of her letter to appreciate her fine legal analysis and sincerity of her appeal to Pam Bondi. I urge lawyers to read Sassoon’s letter start to finish. It is an outstanding example of legal reasoning that expertly combines clear analysis and deft advocacy while upholding the best traditions of the legal profession.

We should all be proud of Danielle Sassoon. She has taken the first step to remediating the disgrace visited on the legal profession by dozens of Trump's legal sycophants.

Emil Bove accepted Sassoon’s politely tendered offer of resignation in her letter. Bove then went shopping for a lawyer cowardly enough to carry out the corrupt dismissal of the charges against Adams—which Sassoon argued “amounted to a quid pro quo” of dismissal in exchange for cooperating with Trump's lawless immigration raids.

Sassoon wrote in her letter:

I attended a meeting on January 31, 2025, with Mr. Bove, Adams’s counsel, and members of my office. Adams’s attorneys repeatedly urged what amounted to a quid pro quo, indicating that Adams would be in a position to assist with the Department’s enforcement priorities only if the indictment were dismissed. Mr. Bove admonished a member of my team who took notes during that meeting and directed the collection of those notes at the meeting’s conclusion.

Bove believed he could find corruptible lawyers in the DOJ’s Public Integrity unit, so he transferred oversight of the case to D.C. As I write, five lawyers from that unit have resigned rather than carry out Bove’s order to dismiss the well-founded charges of corruption against Eric Adams. See NYTimes, Order to Drop Adams Case Prompts Resignations in New York and Washington. (Accessible to all.)

As I write on Thursday evening, it is not clear when Emil Bove will find a corruptible lawyer to ask the court to enter a corrupt dismissal. Given the number of Trump-appointed prosecutors scattered throughout the nation, he will likely succeed in his quest for a coward. Whoever steps up to perform the corrupt bidding of Bove will go down in history as the Robert Bork of our time—the weakest link in the Department of Justice willing to do the president’s bidding.

The details of this story are much more complicated than I have explained above. For further details, I recommend the NYTimes article. Three important points deserve emphasis before addressing the lessons from this episode.

First, a memo circulated by Emil Bove lends support to Danielle Sassoon’s allegation that the dismissal was a corrupt quid pro quo. As reported by NBC, Emil Bove authored a memo stating that the prosecution against Adams should be dropped, in part, because it “limited Adams' ability to aid Trump's crackdown on immigrants and to fight crime.”

Quid = dismissal of charges; quo = “aiding Trump's crackdown on immigration.”

Second, in an apparent effort to deliver the “quo” for the “quid,” Eric Adams agreed to violate an ordinance passed by the New York City council by agreeing to give ICE agents access to the municipal jail at Rikers Island.

Third, New York Governor Kathleen Hochul has the authority to dismiss Eric Adams, but Hochul told Rachel Maddow on Thursday evening that she would not make a “knee-jerk” decision to do so. Instead, she said she would consider her options after consultation with leaders in New York. See Raw Story, NY gov defies calls to oust Adams despite 'extremely concerning' allegations' — for now

Replacing Eric Adams at this point might lead Emil Bove to withdraw the dismissal request—because as an ex-mayor, Eric Adams would not be able to continue delivering the “quo” for the “quid.” If Adams is no longer mayor, he has no value to Trump, who would no longer care if Adams was prosecuted.

Moreover, if the current request to dismiss the case is withdrawn, the judge presiding over the case will not have cause to investigate whether the request for dismissal is corrupt. But if the DOJ pursues the request for dismissal, US District Judge Dale Ho will likely make an inquiry into whether the request for dismissal promotes the interests of justice.

Such an inquiry could turn into a political embarrassment (or worse) for Emil Bove and others acting at the behest of Trump. Offering to drop a criminal case in exchange for a political benefit may qualify as a bribe, extortion, obstruction of justice, or other criminal conduct.

But the legal details are secondary to the fact that Danielle Sassoon has opened a new front in the resistance against Trump. She follows others who have resigned rather than carry out illegal orders by Trump and Musk, but her stand is the highest-profile act of resistance to date—and one that may have given others in the DOJ the courage to follow her example.

Her stand is the perfect example of why we must use every tool available to resist Trump. We will never know which spark will catch fire and inspire others to join the resistance. But if we create enough sparks, the odds increase that one will be the tipping point to unleash the flood. (Apologies for the mixed metaphors!)

The power of one voice is all it takes to start a wave of resistance. That voice could be yours. Take heart from the events of Thursday and use your voice to urge others to resist and act.

Hegseth tries to walk back comments suggesting that Ukraine must surrender

On Wednesday, Secretary of Defense Hegseth shocked everyone (including Trump, apparently) by saying that it was unrealistic to restore Ukraine’s borders to their pre-war status and that Ukraine would not be admitted to NATO as part of any settlement.

Hegseth was flamed by everyone, including the White House, for his reckless, shameful abandonment of Ukraine. On Thursday, he said that he “just talking” but that any negotiating decisions would be made by Trump. See The Hill, Hegseth clarifies NATO comments amid criticism and Mediate, Pete Hegseth Roasted Over 'Huge F*ck Up' on Ukraine Policy.

As noted in the Mediate article,

The Economist’s Shashank Joshi added, “Hegseth’s lack of experience is already showing. Publicly makes a series of pre-emptive concessions prior to the most important negotiations in many years, and then has to publicly explain that he had no authority to say any of those things.”

The problem with Hegseth’s comments is that once concessions are uttered in a negotiation, it is impossible to withdraw them—no matter how lame the excuse for making them in the first instance. Pete Hegseth is an amateur who is in over his head. He needs to keep his mouth shut to avoid inflicting more damage.

Judicial efforts to restrain Trump and Musk

A federal judge has extended the ban on Trump's effort to put the entire staff of USAID on leave—a move that would effectively shutter the agency. See The Hill, Federal judge extends block on Trump putting USAID workers on leave. The problem is that all work has ground to a halt at USAID as third party agencies and contractors are frozen by the chaos and indecision at USAID.

Staff are being held in a state of suspended animation, working “at home” in remote locations around the world, unsure of whether USAID will arrange for their return travel to the US. Food is rotting in warehouses and on docks. See The Independent, USAID inspector fired after revealing nearly $500m in food aid was about to spoil amid Trump funding freeze.

The judge who issued the temporary stay seemed skeptical of the union’s claims that workers are suffering irreparable injury, asking why they cannot simply sue for damages if they have been wrongfully terminated.

A lawyer for the union employees responded, “Once the agency is dissolved, it cannot be put back together again.”

And that is Trump's plan: inflict damage that cannot be repaired and worry about the consequences later. Meanwhile, people are dying of disease and starvation as Trump effectively shuts down the work of the agency by blocking “external communications.”

Per The Independent,

$489 million worth of food assistance was at risk of spoilage after the Trump administration issued an unclear aid freeze guidance, ordered staff to refrain from “external communications” and placed more than 90 percent of USAID workforce on paid administrative leave.

In a separate action, another federal judge ordered the Trump administration to restore funding to USAID to honor contracts with third party providers. See Reuters, Judge orders US to restore funds for foreign aid programs. But without staff to administer the contracts, restoring the funding may be a futile act.

On Wednesday, a federal judge lifted an order that restrained Trump from firing thousands of federal workers. On Thursday, the Office of Personnel Management authorized the firing of workers who were still within their probationary period. See Politico, Trump administration fires thousands of federal workers.

Per Politico,

Officials would not say how many layoff notices they plan to send, but acknowledged they expect to go well beyond the 77,000 employees who have already accepted offers to leave. The voluntary resignation program — ended after a judge’s ruling Wednesday — culled 3 percent of the workforce, well short of the administration’s 10 percent goal.

Although 77,000 sounds like a large number of employees accepting the “buyout” offer, it is less than the normal attrition that would take place during the eight months covered by the offer. Normal attrition is in the 5% to 6% range, while the buyout offer acceptance rate of 3% over eight months. See Federal News Network, Federal workforce attrition rises back up to pre-pandemic levels. (Attrition was “6.1% and 6% in 2019 and 2018, respectively.”)

The Trump / Musk hatchet job is affecting the judiciary

The judiciary is a co-equal, independent branch of government. Its budget is set by Congress directly and is not managed by the executive branch. The Treasury and GAO do serve as the bank and bookkeeper for the judiciary as a matter of convenience. But the president has no authority over the judiciary or its budget.

But the ham-fisted approach of Musk and Trump to federal cuts is sweeping the judiciary without regard to its independence. Josh Marshall of Talking Points Memo addresses the issue at length in an article entitled, Judicial Branch Scrambles To Limit Spillover From Trump’s Executive Branch Rampage.

For example, Musk and Trump have inadvertently terminated or frozen leases for judiciary offices and attempted to place executive branch staff in judiciary buildings as part of the forced “return to office” initiatives in the executive branch.

Chief Justice John Roberts plays a role in the budgeting process for the judiciary and must be aware that the Musk / Trump initiatives are impinging on the independence of the federal judiciary. Whether Roberts cares or will do anything is not clear.

Celebrities quit Kennedy Center Board after Trump appoints himself chair

Trump appointed himself chair of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in D.C. After announcing that he was appointing himself chair, Trump crowed that he was “unanimously” elected by the board to his self-appointed position.

Part of the reason Trump's election was unanimous was that celebrities began to resign from the board after Trump announced his intention to seize control of the center. See The Hill, Stars flee Kennedy Center groups after Donald Trump seizes chair. Shonda Rhimes, Ben Folds, and Renee Fleming resigned from the board of trustees after Trump’s announcement.

And then Trump dismissed the entire remaining board of trustees (in violation of their six year terms) and appointed his own board of trustees who—unsurprisingly—voted unanimously for Trump to serve as chair.

This is next level weird ****. Again, imagine if Joe Biden dismissed the board of trustees—which would have been heavily represented by Trump appointees—and installed himself as chair of the Kennedy Center. But so far as I can tell, no one in the legacy media is bothered by the fact that Trump is acting like an out-of-control narcissist in the manner of Mussolini, Hitler, Franco, Kim Jung Un, Putin, Stalin, etc.

Wall Street Journal’s comment on Trump's tariffs and inflation.

Trump announced on Thursday that more “reciprocal” sanctions would be coming next week. See Politico, Trump sets out process for imposing global reciprocal tariffs.

Given the reported spike in inflation in January, the Wall Street Journal Editorial Board headlined an editorial with the following, which says it all: ‘Does He Understand Money?’: Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal Slams Donald Trump’s Intellect | The Daily Beast.

Concluding Thoughts

I will host a Substack livestream on Saturday morning, February 15, at 9:00 am PST / 12:00 noon EST. There is no link. Just open the Substack app at the appointed time and you will see a notification that I have opened a livestream session. I will send a reminder email 30 minutes before I start the session.

The resistance within the DOJ is freighted with significance. Danielle Sassoon is a Republican appointee with sterling Republican credentials—a Scalia clerk who is a member of the Federalist Society. And yet she put her loyalty to the Constitution above her loyalty to Donald Trump.

Trump's kryptonite is disloyalty. He melts like the Wicked Witch of the West when people refuse to be bullied. Dannielle Sassoon has demonstrated that there is a path forward that does not involve breaching an oath to defend the Constitution.

The Eric Adams Affair has yet to see its denouement. But we know the outcome. Trump loses. Even if he manages to dismiss the charges against Adams, he has suffered a grievous blow to his air of invincibility. And if he backs down, the sharks will smell blood in the water.

Trump can be defeated. All it takes is a single person with courage and moral conviction to inspire others to action. Each of us should raise our voices—because we cannot know in advance which of those voices will be the spark that sets the resistance aflame.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#Robert B. Hubbell#Robert b. Hubbell Newsletter#DOJ#Danielle Sassoon#Rule of Law#The Constitution#the eric Adams Affair#loyalty#disloyalty#Jack Ohman

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Hague’s Hypocrisy,” roared the headline in one of Israel’s mass-circulation dailies. “The Hague’s Disgrace,” blared the competing paper.

Outrage was the most obvious public response in Israel when the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Karim Khan, announced that he’d seek arrest warrants against Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Yoav Gallant on charges of crimes against humanity. Khan’s parallel request to arrest three Hamas leaders didn’t quiet the fury.

Netanyahu, predictably, accused Khan of feeding “the fires of antisemitism.” But even Israeli legal experts who are deeply critical of the prime minister were disturbed that Khan seemed to put Israeli and Hamas commanders in the same category. “It’s unacceptable to create legal equivalence between the attacker (Hamas) and the attacked (Israel),” as one wrote.

I’m an ordinary enough Israeli to share some of that reflexive anger. The world does seem to pay outsized attention to Israeli actions, and to forget which side committed atrocities on Oct. 7, 2023, and ignited this war.

But outrage is a poor tool for judging whether Khan has a case against Netanyahu and Gallant. For me, the key to answering that question is in a name: Theodor Meron.

Before submitting his request, Khan submitted his evidence to a committee of leading experts on the laws of war. They agreed unanimously that “there are reasonable grounds to believe that the suspects he identifies have committed war crimes and crimes against humanity within the jurisdiction of the ICC.” Theodor Meron—a 94-year-old Holocaust survivor, jurist, and former Israeli diplomat—is by far the most prominent of those experts.

I first encountered the name “T. Meron” in the Israeli State Archives more than 20 years ago while researching The Accidental Empire, my book on the history of Israeli settlements in occupied territory. His signature appeared at the bottom of a page in a declassified file from the office of the late Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol. The top of the page was marked “Most Secret.” What appeared in between pushed me to find out more about him.

Meron was born in 1930 to what he would describe as a “middle-class Jewish family” in Kalisz, Poland. His “happy but, alas, short childhood” ended at age 9 with the German invasion. Somehow, he survived the Holocaust while living in Nazi ghettos and labor camps. Most of his family did not. Soon after the war, at age 15, he managed to immigrate to the city of Haifa in what was then British-ruled Palestine.

For six years, his only schooling had been suffering. The lost years of education “gave me a great hunger for learning,” he’d say later. He completed high school in a new language, then a law degree at the Hebrew University, then a doctorate at Harvard and post-doctoral studies in international law at Cambridge.

In 1957, with no academic position in the offing, he took an offer from the Israeli Foreign Ministry. Just after the Six-Day War in 1967, he was appointed as the ministry’s legal advisor—effectively, the Israeli government’s top authority on international law—as a 37-year-old wunderkind.

A decade and an ambassadorship later, he returned to academia. As for many Israeli scholars, this meant going abroad—in Meron’s case, to New York University’s law school. His legal writing has been described as having “helped build the legal foundations for international criminal tribunals”—starting with the one established by the United Nations in 1993 to deal with crimes committed in the wars following the breakup of Yugoslavia.

By then a U.S. citizen, Meron was appointed as a judge on that tribunal in 2001. He served for several years as its president and on its appeals court. In an interview, he said he found his position “poignant” and “daunting”: the onetime child prisoner of the Nazis now presiding in judgment on crimes including genocide. He has taken particular pride in a ruling that “defined rape and sexual slavery as crimes against humanity.”

Well into his 90s, Meron is again a law professor, this time at Oxford University—as well as an advisor to Khan, the ICC chief, most recently on the case against the Israeli and Hamas leaders.

It is crucial to recall that Khan’s request for warrants is not a conviction. What Meron and the other experts confirmed is that the evidence and the law provide a basis for trying Netanyahu and Gallant, as well as Hamas figures Yahya Sinwar, Mohammed Deif, and Ismail Haniyeh.

The experts’ report rejected any Israeli claim that the International Criminal Court lacks standing. “Palestine, including Gaza, is a State for the purpose of the ICC Statute,” they said. Unlike Israel, it has accepted the court’s jurisdiction. The court therefore can rule on actions in Gaza—and by Palestinians on Israeli territory, the report says.

In a joint opinion piece in the Financial Times, Meron and his colleagues also stressed that “the charges have nothing to do with the reasons for the conflict.” To unpack that: Israel may be fighting a justifiable war of defense—but certain Israelis, including the head of government, may have committed crimes in the way that they’ve conducted that war.

The proposed charges against Sinwar, Deif, and Haniyeh include the crime against humanity of extermination in the killing of civilians in the Oct. 7 attack on Israel, and the war crimes of taking hostages and of rape.

The central charge against Netanyahu and Gallant is that they engaged in “a common plan to use starvation and other acts of violence against the Gazan civilian population”—in order to eradicate Hamas, free the Israeli hostages, and punish the Gazan population. In other words, impeding humanitarian aid wasn’t a foul-up. It was allegedly an intentional means of waging war.

Khan lists the types of evidence that he gathered—interviews with survivors, video material, satellite images, and more. He did not release the evidence itself. For now, we’re left to rely on the unanimous view of the experts. And there is likely no one on earth more qualified than Meron to judge whether Khan has a solid case. To suggest that Meron is persecuting Israel seems laughable. To claim that he is antisemitic is obscene.

This isn’t a verdict. It’s a reason to take the charges seriously.

In fact, Israel would likely not be in this situation if its government had taken Theodor Meron seriously much sooner—in September 1967, when he wrote the memorandum that I found in the archives.

At the time, Prime Minister Eshkol was weighing whether Israel should create settlements in the territory it had conquered in the unexpected war three months earlier. Eshkol leaned toward reestablishing Kfar Etzion, a kibbutz that had been overrun by Arab forces in 1948. The site was between Hebron and Bethlehem in the West Bank, which had been ruled by Jordan in the intervening years. Eshkol was also interested in settlement in the Golan Heights, Syrian territory that had also recently been conquered by Israel.

In a cabinet meeting, though, the justice minister had warned that settling civilians in “administered” territory—the government’s term for occupied land—would violate international law. Eshkol’s bureau chief asked the Foreign Ministry’s legal advisor to weigh in.

Meron’s response was categorical: “My conclusion is that civilian settlement in the administered territories contravenes explicit provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention.” The 1949 convention on protection of civilians in time of war, he explained, barred an occupying power from moving part of its population into occupied land. The provision, he wrote, was “aimed at preventing colonization” by the conquering state.

Nine days later, a group of young Israelis settled at the Kfar Etzion site, with the government’s backing. At first, the settlement was identified publicly as a military outpost. As Meron himself had noted, it was legal to build temporary military bases in occupied territory. But this was a ruse, and it quickly wore thin as the civilian character of new settlements became obvious.

So the government soon depended instead on the argument of two prominent Israeli jurists, Yehuda Blum and Meir Shamgar. They argued that the Fourth Geneva Convention didn’t apply to the West Bank. Since Jordan’s sovereignty there had gone almost entirely unrecognized internationally—so their argument went—it wasn’t occupied territory.

As Meron himself wrote in 2017, 50 years after his original memorandum, this theory doesn’t hold water. The convention isn’t aimed at protecting states and claims of sovereignty. It protects people living under occupation from acts of the occupying power.

This raises the question: What would have happened if Eshkol’s government had gritted its teeth in 1967 and accepted its own lawyer’s opinion?

To start, there’d be no settlements in occupied territory. The entire network of large Israeli suburbs, smaller gated exurbs, and tiny outposts wouldn’t exist. The Israeli military would not need to guard these communities, and Israel would not have invested vast resources in tying itself to occupied territory.

We can’t know if there would now be a Palestinian state next to Israel, or perhaps peace in some other constellation. Settlements have not been the only obstacle to a peace agreement. But they are a major one. Moreover, a portion of the settlements—the ideological exurbs—have been a hothouse for the Israeli radical religious right, utterly opposed to giving up land. The two most extreme parties in Netanyahu’s government are led by settlers and count the settlements as their core constituency. Without the settlements, the odds of Israel avoiding its current predicament would have been better.

Accepting Meron’s opinion back then could also have established a different attitude toward international law among Israeli politicians and military leaders—namely, a position of stringent observance. Perhaps such an attitude would have led Netanyahu and Gallant to conduct the current war in a different way, avoiding the acts now alleged by the ICC prosecutor.

Yet the key word is alleged. A critical element of the crimes that Khan alleges is that they were intentional—that starvation and other causes of civilian death were a policy.

It is indeed possible that Israel’s leaders deliberately prevented food and other basic needs from reaching the people of Gaza—that aid was blocked as a means of pressuring Hamas to release hostages or even to give up rule of Gaza. Hamas has used Gazan civilians as human shields; perhaps Netanyahu sought to use their suffering as a weapon against Hamas.

It’s also possible that the failure to get food to Gazans is a result of multiple factors: of the chaos of battle, Egyptian mistakes, Hamas actions, Israeli soldiers mistakenly firing on aid workers just as they have sometimes mistakenly fired on other Israelis, and of the Israeli government’s incompetence—a continuation of the miserable ineptitude that left Israel unprepared on Oct. 7.

All too many people in the world seem to be certain already which of these possibilities is true, based largely on their prior assumptions or the tsunami of media reports. If Khan ever does manage to bring Netanyahu and Gallant to trial, though, he will need to establish intent with hard evidence.

There is another lesson that I took from finding Meron’s 1967 memo: The best evidence of government intent often lies in documents that stay secret for decades. This is even more true of decisions in war, and it adds to the reasons that Israel itself should be investigating what has happened in Gaza.

It’s unlikely that the International Criminal Court would have access to classified Israeli documents. On the other hand, an Israeli state commission of inquiry into the entire conduct of the war—from the disastrous intelligence failure of Oct. 7 onward—would be able to demand such access, and to call top officials and officers to testify.

An explicit point made in Khan’s announcement is that he would defer to Israel if it were conducting its own “independent and impartial” investigation of the alleged crimes. This is the principle of “complementarity”: The ICC’s jurisdiction applies only when national judicial systems fail to act.

A commission of inquiry isn’t a criminal proceeding. But if Israel were investigating itself, then Khan would have good reason to suspend or end his own investigation.

Within Israel, however, it’s a given that Netanyahu’s government will not instigate an inquiry commission with the necessary independence and wide mandate. That can come only if the country’s intense political crisis leads to the fall of the government and new elections.

Netanyahu would like to use the reflexive public anger against Khan’s request for arrest warrants to restore some of his lost support. But the rational reaction is the opposite: The potential ICC case is one more reason to end Netanyahu’s rule and investigate all facets of the war.

Or to put it differently: In 1967, at the start of the occupation, an Israeli government ignored a warning from a remarkably young advisor on international law. Today, Israel needs to heed a new warning from a remarkably old authority on the laws of the war—the same man.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Albanian burglar who claimed asylum to avoid deportation has taunted British taxpayers and the Home Office by filming himself cruising around London in a £300,000 Rolls-Royce Cullinan.

Gucci-wearing Dorian Puka, 28, has previously been jailed and deported twice for a string of burglaries in the UK.

Puka has now used his public TikTok account, followed by over 1500 people, to post a video of himself driving around London in a Rolls-Royce with Albanian music playing in the background.

In the brazen clip, he appears to park on a set of double yellow lines as he showed off the exterior of the flashy car as he carefully avoided showing the number plates.

And the criminal took to his Instagram account this morning to post a clip from the film American Gangster showing Denzel Washington's character Frank Lucas talking about the importance of 'honesty and integrity' in business.

He also shared a video shouting at his friends from the window of a Mercedes G-Wagon as they rode along side him swerving on a motorbike.

Despite being kicked out of the UK twice, Puka cannot be evicted from the country a third time until his latest asylum application is dealt with - and each one costs the taxpayer £12,000 on average.

Asylum seekers can also claim £49.18 a week of public cash in asylum support.

Puka was first jailed in 2016 for nine months and then deported the following year for attempting to break into a home in Twickenham when the owner caught him on a webcam whilst on holiday in France.

However, within a year Puka managed to dodge border control and wormed his way back into Britain where he continued to raid and rob homes in Greater London.

He was eventually apprehended, wearing an expensive stolen watch, by a plain clothes officer in Surbiton, south-west London.

Puka was jailed for three-and-a-half years but his offending did not stop once behind bars as he gained notoriety posting photos on a smuggled phone with prisoners associated with organised crime groups.

He was deported in March 2020, but was back by the following January. Social media posts showed he had travelled via Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Despite this, the Home Office said he cannot be deported until his asylum claim has been fully considered. This process could take months or even years due to the huge and ever-growing backlog of immigration tribunal appeals.

It's not the first time Puka has taunted the British public on his TikTok account.

At the start of the year, he posted a video of himself welcoming in 2025 while smoking a shisha pipe in front of a belly dancer.

The three minute video, which was posted to his Tik Tok, ended with a shot of the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, overlaid with the words: 'Happy New Year everyone!...Wish the best for all!'

And in October he posted another video of himself driving a £300,000 red Ferrari around the streets of the capital.

In the same month, Puka also trolled Nigel Farage after posting a picture of himself raising a toast and tucking into a meal next to a doctored photo of the Reform UK leader.

Mr Farage labelled him 'a proper wrong'un' and said we are 'literally being walked all over' by the convicted criminal.

Puka has also previously shown off other luxury cars including a £75,000 Porsche Cayenne, a £130,000 Mercedes G-Wagon, £155,000 Bentley Bentayga, a £55,000 BMW X5, a £46,000 Mercedes AMG, and a £35,000 Jaguar XF.

Other social media posts showed him enjoying evenings at local shisha bars, treating relatives to high-end meals, and unboxing a brand-new Patek Philippe watch.

Regarding Puka, a Home Office spokesperson previously said: 'Foreign nationals who commit crimes should be in no doubt that the law will be enforced.

'Mr Puka has been deported by the UK before. It is UK law that we cannot deport individuals where there are claims or representations still awaiting decision.

'We have already begun delivering a major surge in immigration enforcement and returns activity to remove people with no right to be in the UK, with 3,000 returned since the new government came into power.'

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Advocate for Social Justice: Back Daniel's Quest for Fairness

Hi Tumblr community!

I come to you today with a plea for support during a pivotal moment in my life's journey. My name is Daniel, and for nearly a decade, I've proudly contributed to the fabric of Australian society. As a former Federal Police officer in France, I arrived in Australia with dreams of furthering my service to the community and ultimately obtaining citizenship.

Yet, my path has been fraught with unforeseen challenges. Despite my unwavering determination, I've encountered obstacles that have led to the loss of my citizenship. Now, I find myself entangled in legal proceedings that threaten my ability to serve as a Federal Police officer here in Australia.

Last month, my application for a bridging visa—the lifeline I desperately need—was rejected. This decision has left me in a dire financial situation, with limited resources and no legal immigration status. I am currently unable to work, compounding my struggles.

To proceed with my case, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal demands an application fee of $1687—a sum beyond my reach.

In this time of uncertainty and despair, I turn to you, my community, for support. Your contributions will not only help cover the necessary legal fees but will also provide me with the hope and strength to navigate through this challenging chapter of my life.

Every donation, no matter how small, will make a significant difference. Your support will not only alleviate my immediate financial burdens but will also enable me to focus on resolving my legal issues and rebuilding a stable future in Australia.

I humbly ask for your generosity and support in sharing my GoFundMe (click on the picture). Together, we can make a difference and help me overcome this obstacle. Thank you for your kindness and compassion.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thank you Sir Peter Richard Lane. Not all heroes wear capes [Prince Harry vs RAVEC} by u/Negative_Difference4

Thank you Sir Peter Richard Lane. Not all heroes wear capes [Prince Harry vs RAVEC} https://ift.tt/os5RSGk Justice Lane was educated at state schools in Worcester, before studying law at Oxford and Berkeley, California. After 5 years in the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel, he became a solicitor and parliamentary agent in Westminster, drafting and promoting legislation on a wide range of subjects; in particular, infrastructure projects. His clients included public transport operators, local authorities and universities. In 2001, he was appointed as a salaried immigration adjudicator, in time becoming a judge of the Upper Tribunal. In 2014, he became President of the General Regulatory Chamber of the First-tier Tribunal, which decides appeals from a wide range of statutory regulators. He was appointed a deputy High Court judge in 2016 and, in 2017, a High Court judge in the Queen’s Bench Division. Since October 2017, he has also been President of the Upper Tribunal Immigration and Asylum Chamber. He was appointed as Deputy Chair of the BCE initially for a three year term from 23 June 2020, subsequently extended to 22 December 2023.He has now retired as a Judge of the High Court (King’s Bench) with effect from 1 February 2024. This was his last case post link: https://ift.tt/HtKALRV author: Negative_Difference4 submitted: February 29, 2024 at 12:27PM via SaintMeghanMarkle on Reddit

#SaintMeghanMarkle#harry and meghan#meghan markle#prince harry#fucking grifters#Worldwide Privacy Tour#Instagram loving bitch wife#Backgrid#voetsek meghan#walmart wallis#markled#archewell#archewell foundation#megxit#duke and duchess of sussex#duke of sussex#duchess of sussex#doria ragland#rent a royal#clevr#clevr blends#lemonada media#archetypes#archetypes with meghan#invictus#invictus games#Sussex#Negative_Difference4

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

From Temporary to Permanent Residency: How the Best Immigration Agents Make It Happen

For many migrants in Australia, the journey from temporary to permanent residency can be challenging. With complex visa requirements and ever-changing regulations, expert guidance from a Registered Migration Agent (RMA) can make all the difference. Here’s how the best immigration agents help migrants successfully transition to permanent residency in Australia.

1. Understanding the Pathways to Permanent Residency

There are several visa pathways to transition from temporary to permanent residency, including:

Skilled Migration Pathway – For temporary visa holders (e.g., subclass 482, 485) with in-demand skills.

Employer-Sponsored Pathway – For those with employer sponsorship, leading to visas like subclass 186 or 187.

Family and Partner Visas – For spouses, parents, or dependents of Australian citizens or permanent residents.

Business and Investor Visas – For entrepreneurs and investors looking to establish a business in Australia.

A skilled migration agent will assess your eligibility and recommend the most suitable pathway based on your qualifications and circumstances.

2. Navigating Complex Visa Requirements

Australia’s visa system is highly regulated, and small mistakes can lead to delays or refusals. The best immigration agents ensure:

Accurate and complete documentation

Timely submission of applications

Compliance with visa conditions to avoid cancellation risks

By working with a migration expert, applicants can avoid unnecessary setbacks and improve their chances of a smooth transition.

3. Strategic Planning for PR Eligibility

Not all temporary visa holders automatically qualify for permanent residency. A migration agent helps plan your journey by:

Advising on skill assessments and English language requirements

Recommending work experience and employer sponsorship options

Ensuring compliance with residency obligations

This strategic approach ensures that you meet the eligibility criteria when it’s time to apply for PR.

4. Overcoming Challenges and Visa Refusals

Visa applications can be complex, and some applicants face refusals due to missing documents, incorrect information, or eligibility issues. A Registered Migration Agent can assist with:

Reviewing refusal reasons and lodging appeals with the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT)

Preparing a stronger reapplication with improved documentation

Representing clients in complex cases involving health, character, or sponsorship issues

Their experience in handling complex cases can be crucial in turning around a previously rejected application.

5. Assisting with Permanent Residency Applications

Once you are eligible for PR, an immigration agent will guide you through the final steps, including:

Preparing and lodging the permanent residency application

Ensuring all supporting documents (e.g., police clearances, health checks) are in order

Tracking application progress and liaising with the Department of Home Affairs

Their expertise can help streamline the process and minimize delays.

6. Post-PR Support: Citizenship and Beyond

Many migrants aim to become Australian citizens after gaining permanent residency. The best migration agents provide ongoing support for:

Citizenship eligibility assessments

Application preparation and lodgment

Preparing for the citizenship test and interview

With expert guidance, the journey from temporary visa holder to Australian citizen becomes more seamless and stress-free.

Final Thoughts

Transitioning from a temporary visa to permanent residency in Australia requires careful planning, compliance with visa regulations, and expert guidance. The best immigration agents offer strategic advice, handle complex applications, and maximize your chances of success.

If you’re considering making Australia your permanent home, consulting with a Registered Migration Agent is the first step toward achieving your goal. Start planning your PR pathway today with expert assistance!

0 notes

Text

Protection Visa (Subclass 866): A Guide to Seeking Safety in Australia

Australia has long been a destination for individuals seeking safety and protection from persecution in their home countries. If you are in Australia and fear returning to your country due to threats of harm, you may be eligible to apply for a Protection Visa (Subclass 866). This visa provides permanent residency to those who meet the criteria for refugee or complementary protection status under Australian law.

In this guide, we will explain what the Protection Visa (Subclass 866) is, who is eligible, how to apply, and what benefits it offers.

What is a Protection Visa (Subclass 866)?

The Protection Visa (Subclass 866) is a permanent visa designed for people in Australia who meet the legal definition of a refugee or who qualify for complementary protection. This visa allows successful applicants to stay in Australia permanently, work, study, and access essential government services.

Who is Eligible for a Protection Visa?

To qualify for a Protection Visa (Subclass 866), you must meet the following criteria:

1. Be in Australia

You must be in Australia when applying for this visa. It cannot be lodged from outside the country.

2. Meet the Definition of a Refugee or Need Complementary Protection

To qualify, you must:

Fear persecution due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group; or

Be at risk of significant harm if returned to your home country, even if you do not meet the refugee definition.

3. Pass Health, Security, and Character Checks

Applicants must meet Australia’s health and character requirements, including background checks and medical assessments.

4. Lodge a Valid Application

You must apply within the required timeframe and provide all necessary supporting documents.

How to Apply for a Protection Visa (Subclass 866)

Applying for a Protection Visa involves several important steps:

Step 1: Gather Evidence

You need to provide detailed information about your situation, including:

Identity documents (passport, national ID, birth certificate, etc.)

Statements explaining why you fear persecution or harm

Supporting documents (e.g., police reports, medical records, news articles, or statements from witnesses)

Step 2: Complete the Application Form

You must fill out the Protection Visa (Subclass 866) application form online or on paper. Ensure all information is accurate and complete.

Step 3: Submit Your Application

You can submit your application online through ImmiAccount or by paper submission to the Department of Home Affairs.

Step 4: Attend an Interview

Most applicants will be required to attend an interview with an immigration officer. During this interview, you will be asked about your claims and supporting evidence.

Step 5: Await the Decision

Processing times vary based on individual circumstances and the complexity of the case. While waiting, you may be granted a Bridging Visa to remain lawfully in Australia.

What Happens If Your Protection Visa is Granted?

If your Protection Visa (Subclass 866) is approved, you will receive:

Permanent Residency: You can stay in Australia indefinitely.

Work and Study Rights: You are allowed to work and study in Australia.

Access to Government Benefits: You can access Medicare and Centrelink support services.

Pathway to Citizenship: After meeting residency requirements, you may apply for Australian citizenship.

Family Sponsorship: In some cases, you may be able to sponsor eligible family members for visas.

What If Your Application is Refused?

If your visa application is refused, you may have the right to appeal the decision through the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT). It is important to seek professional legal or migration advice if your application is denied.

Seeking Professional Assistance

Applying for a Protection Visa (Subclass 866) can be complex and emotionally challenging. Having the right support can improve your chances of a successful application. New Roots Migration specializes in protection visa applications, guiding individuals through the process with care and professionalism.

If you need help with your application or an appeal, contact New Roots Migration today for expert advice and assistance. Your safety and future in Australia matter, and you don’t have to go through this process alone.

0 notes

Text

Judicial Review: Pre-Action Protocol

Embarking on the journey of challenging a decision made by the Home Office can be a complex and daunting endeavour. Whether it’s about obtaining entry clearance, leave to remain, or settlement rights, individuals often find themselves entangled in legal intricacies. Understanding the Pre-Action Protocol is crucial in navigating this process smoothly. This protocol, enshrined within the Civil…

View On WordPress

#Administrative Review#Appeal#Best Immigration Solicitors London#civil procedure rules#David J Foster & Co#David J Foster & Co Solicitor#DJF Solicitors#Home Office#Home Office Updates#Immigration Judicial Review#Immigration Judicial Review Application#Immigration Lawyers London#Judicial Proceedings#Judicial Review#Judicial Review Application#Judicial Review Claim#Letter Before Claim#Lexvisa#London Immigration Solicitors#PAP#Permission for Judicial Review#Pre Action Protocol#UK Immigration#UK Immigration Advice#UK Immigration Solicitors/ Lawyers#Upper Tribunal#Upper Tribunal Appeal

0 notes

Text

The Supreme Court creates train wreck over Texas immigration law.

Over the last forty-eight hours, the Supreme Court has made a monumental mess of its review of a Texas law that seeks to assume control over the US border. If the consequences weren’t tragic, it would be comical.

The Texas law is plainly unconstitutional. It is not even a close question. But the Supreme Court created a situation in which enforcement of that law was stayed and then permitted to go back into effect multiple times in a forty-eighth hour period. It was like the Keystone Cops—all because the Supreme Court does not have the fortitude to control the rogue judges on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Here's the bottom line: As of late Tuesday evening, the Texas law cannot be enforced pending further order of the Fifth Circuit. See NBC News, Appeals court blocks Texas immigration law shortly after Supreme Court action. As explained by NBC,

A three-judge panel of the New Orleans-based 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals split 2-1 in saying in a brief order that the measure, known as SB4, should be blocked. The same court is hearing arguments Wednesday morning on the issue.

The appeals court appeared to be taking the hint from the Supreme Court, which in rejecting an emergency application filed by the Biden administration put the onus on the appeals court to act quickly.

I review the complicated procedural background below with a warning that it may change in the next five minutes. For additional detail, I recommend Ian Millhiser’s explainer in Vox, The Supreme Court’s confusing new border decision, explained.

Let’s start here: The federal government has exclusive authority to control international borders. The Constitution says so, and courts have ruled so for more than 150 years.

There are good reasons for the federal government to control international borders. If individual states impose contradictory regulations on international borders that abut the states, the federal government could not promulgate a single, coherent foreign policy—which is plainly the job of the federal government.

Texas passed a law that granted itself the right to police the southern border and enforce immigration laws, including permitting the arrest and deportation of immigrants in the US who do not have the legal authority to remain in the country.

Mexico immediately notified Texas that it would not accept any immigrants deported by Texas. (Mexico does accept immigrants deported by the US per international agreements.)

A federal district judge in Texas enjoined the enforcement of state law, ruling that it usurped the federal government's constitutional role. Texas appealed.

When a matter is appealed, the court of appeals generally attempts to “maintain the status quo” as it existed between the parties prior to the contested action. Here, maintaining the status quo meant not enforcing the Texas law that allowed Texas to strip the federal government of its constitutional authority over the border.

However, the Fifth Circuit used a bad-faith procedural ploy to suspend the district court’s injunction, thereby allowing Texas law to go into effect. In doing so, the Fifth Circuit did not “maintain the status quo” but instead permitted a radical restructuring of state-federal relations in a way that violated the Constitution and century-and-a-half of judicial precedent.

In a world where the rule of law prevails, the Supreme Court should have slapped down the Fifth Circuit's bad-faith gambit. It did not. Instead, the Supreme Court allowed the Fifth Circuit's bad-faith ploy to remain in effect—but warned the Fifth Circuit that the Supreme Court might, in the future, force the Fifth Circuit to stop playing games with the Constitution.

The debacle is an embarrassment to the Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit. The reason the Fifth Circuit acts like a lawless tribunal is because the Supreme Court has allowed the Fifth Circuit to engage in outrageous, extra-constitutional rulings without so much as a peep of protest from the reactionary majority on the Court.

John Roberts is “the Chief Justice of the United States.” He should start acting like it by reprimanding rogue judges in the Fifth Circuit by name—and referring them to the Judicial Conference for discipline. Until Roberts does that, the Fifth Circuit will do whatever it wants.

[Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter]

#robert b. hubbell#Robert B. Hubbell Newsletter#corrupt SCOTUS#Fifth Circuit#Chief Justice#legal precedent#Nick Anderson#immigration#Texas

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s what we know: Jews eat Chinese food. North American Jews did so in the early 20th century, when Ashkenazi immigrants lived near Chinese immigrants in New York’s Lower East Side. We do so today on Christmas. And some of those Chinese-food-eating Jews keep kosher. So, we have kosher Chinese restaurants. The most natural thing in the world.

What’s a little murkier is when the need for kosher Chinese restaurants announced itself, and who took the lead on bringing them to fruition.

Those Ashkenazim frequenting Manhattan’s Chinatown were participating in what University of Connecticut sociology professor Gaye Tuchman calls “safe treyf:” There was no mixing of meat and dairy, because Chinese food uses little to no dairy. Treyf ingredients such as pork and shellfish were often fine-chopped and hidden away inside dumplings or egg rolls, according to a piece Tuchman co-authored with Harry Levine, “New York Jews and Chinese Food: The Social Construction of an Ethnic Pattern,” an article in Volume 22 of Contemporary Ethnography.

“I went to Brandeis University,” Tuchman said during a recent phone call. “A whole bunch of us from my floor when I was a freshman… went into Waltham, to a Chinese restaurant. And two of us had a problem, because two of us kept kosher. And the solution was to pull the pork out of an eggroll if you saw it.”

Safe treyf isn’t just a cute phrase, in other words. It’s something Tuchman, a descendant of Ashkenazi immigrants, lived. She posits that even Jews who didn’t keep kosher were turned off by the mixing of dairy and meat because it simply wasn’t something they would have grown up with. But Chinese food quite quickly became something Ashkenazi immigrants and their children did grow up with.

“I think that the first or second kind of restaurant I ever ate out of that, that wasn’t a kosher deli, was probably a Chinese restaurant,” she said.

And so, throughout the 20th century, we see that Jews ate Chinese food whether it was kosher or not, which deepens the mystery of how and why kosher Chinese restaurants came about.

It seems that before there were kosher Chinese restaurants, there were kosher restaurants that served a bit of Chinese food, and some restaurants that served some kosher dishes, some Chinese and some other items as well — maybe casting a wide net to appeal to a variety of immigrant groups. For example, ads in several 1948 editions of the Detroit Tribune tout that a kosher luncheonette called Holiday Dinning [sic] Room serves Chinese and creole food, in addition to spaghetti. (The ad also brags that the restaurant is “specializing in shrimps,” so take its claims of kashrut with a grain of salt.)

A few 1954 editions of the Key West Citizen also proclaim that Einhorn’s Deli serves kosher, Chinese and Cuban food.

The restaurant largely credited as the first kosher Chinese — Bernstein-on-Essex, also known as Schmulka Bernstein’s — follows that model. It opened as a kosher deli in 1957 and began serving Chinese food in 1959. Its owner, Solomon Bernstein, was Jewish, and so were most of the clientele, at least judging by a 1970s ad, but many of the staff were Chinese. Roumanian pastrami made its way into some Chinese dishes. Lo mein Bernstein was made with chicken livers.

Schmulka Bernstein’s, named after Solomon’s father, who was a butcher, stayed open until the 1990s, inspiring at least some members of a new generation.

“I, like many others, went to Schmulka Bernstein’s growing up,” said Elie Katz, co-owner of Chopstix, a kosher Chinese restaurant in Teaneck, New Jersey. “Like many others, we got our car broken into. Part of the experience when you go there, when you’re that age.”

One of the more well-known Jewish-owned kosher Chinese restaurants to follow in Schmulka Bernstein’s footsteps was Moshe Peking, which opened in Manhattan’s Garment District in 1978. Its owner, Martin Soshtain, told the New York Times that he had hired a Shanghai-born chef who was working at a resort in the Catskills and so knew how to cook kosher. The Timesarticle says that sea bass stood in for shellfish, veal for pork and pastrami for ham.

Katz also hired a Chinese chef when he opened Chopstix in 1996. He says that, above all else, he wanted to open a great Chinese restaurant that would appeal to people of all backgrounds. He points out that keeping kosher and cooking everything to order made Chopstix especially well-suited to accommodate other dietary restrictions, from low-fat to gluten-free.

“We actually have people that give us bottles of their soy sauce that they buy,” Katz says. “We put their name on it, and then they place the order and they’re like, ‘Please use Mrs. Stein’s gluten-free soy sauce.��”

Chopstix also offers a few Korean menu items; many of the contemporary kosher Chinese restaurants do offer sushi and other dishes from East and Southeast Asia — menus at these places can resemble a pan-Asian, non-kosher restaurant. Like their predecessors, they’re trying to reach a broad audience.

It’s hard to get a count of how many kosher Chinese restaurants there are. Different kosher certifications will obviously list different restaurants, and often vegan Chinese restaurants get lumped in with the kosher on sites like Yelp. It’s even harder to get a handle on which ones have Jewish ownership, and whether any have Chinese owners, Jewish or otherwise.

What’s clear, though, is that these aren’t relics of the past, frozen in time. Katz says he has second and even third generations coming into the restaurant, in addition to a thriving catering business. The Cho-Sen local chain of kosher restaurants in New York City opened a new spot late last year. If I had to guess, I’d estimate a hundred or so kosher Chinese restaurants exist in the U.S., with the great majority in New York City and its suburbs. Los Angeles comes in second. It may not sound like a lot — a drop in the ocean of 45,000 Chinese restaurants nationwide — but it’s a lot more than we had a century ago.

As far as why they started cropping up when they did, that’s probably just down to someone needing to be first. And for that, we thank Sol Bernstein.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

UK Dependent Visa: Reunite With Your Loved Ones in the UK

Get Expert guidance for spouse, partner, and child visas.

Introduction to dependent visa UK-

Bringing your family to the UK is a significant step. The SmartMove2UK specialises in helping families navigate the dependent visa application process, ensuring a smooth and successful reunion with your loved ones.

Who Can Apply for UK Dependent Visa?

Spouse, Civil Partner, or Unmarried Partner: If you're married, in a civil partnership, or have lived together for at least 2 years, you may be eligible. Proof of a genuine relationship is essential.

Children Under 18: Your children can join you if they rely on you for financial and emotional support.

Requirements for a UK Dependent Visa

Relationship Requirements: Proof of relationship.

Financial Requirements: Sufficient funds to support your family without relying on public funds.

Accommodation Proof: Evidence of suitable accommodation.

Sponsor's Visa: The person in the UK must have a valid visa that allows dependents.

Intent to Live Together: You and your family must intend to live together in the UK.

Top 5 Reasons Why UK Visa Applications Are Refused

Incomplete or Incorrect Documentation

Insufficient Financial Evidence

Failure to Meet Eligibility Requirements

Previous Immigration History

Lack of Credibility in Supporting Evidence

UK Visa Refused? Don't Give Up – The Smartmove2UK Can Help!

You can go for any one of these 04 options!*: 1) Administrative Review 2) Appeal to First Tier Tribunal 3) Judicial Review OR 4) Re apply UK visa

How The SmartMove2UK can Help

Eligibility Assessments

Document Checklists

Application Drafting and Submission

Interview Preparation

Appeals and Reapplication

Common Visa Types We Assist With

Skilled Worker Dependent Visa

Innovator Visa Dependent Visa

Senior or specialist worker dependent visa

Health and care worker dependent visa

Graduate dependent visa

High potential individual dependent visa

UK expansion worker dependent visa

Student dependent visa

Graduate dependent visa

Important Updates regarding UK Dependent Visa

Student Visa Restrictions: Most students can no longer bring dependents, except for PhD students.

Health and Care Worker Visa Restrictions: Care workers can't bring dependents.

Testimonial:

"Thanks to The SmartMove2UK, my wife joined me in the UK without any complications. Their professionalism is unmatched.” - John M., London

Ready to reunite with your family?

Contact us today for your initial free consultation!

#uk dependent visa#dependent visa uk#uk visa application#uk immigration#uk immigration solicitors#smartmove2uk#uk visa

0 notes

Text

It seems there is some confusion in the notes about what this implies in practice, though I think the post's last paragraph offers enough to figure this out, I'll expand on it.

Let's continue with the example of immigration, and I am assuming the communist in the interaction is organized in a communist party, or at the very list a similar enough org. This is what Lenin called the popular tribune. Imagine a concerned coworker, friend, fellow student, or any acquaintance brings up the topic of immigration policy to you and asks you what should be done. The point of class conscious politics is to understand the various ways in which the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie governs with different policies in favor of the capitalist class. Would it be an appropriate course of action to get into the weeds of how many of the immigrant workers should be exploited and how harshly? Or would it be better to converse with the friend, coworker, fellow student or acquaintance about our perspective on immigration, explaining the arguments I laid out in the original post?

The goal of an agitator is not to discuss how capitalism should be managed, it's to advance the idea that it should be abolished, and that it should be abolished through the revolutionary organization of the working class. I share the concern and solidarity towards immigrant workers, and of course it would be preferable if, when they are forced to escape the violence exerted on them by our very own imperialists, they had a safe trip and decency in their stay. But what we can never campaign for in good conscience, is for the continuation of the system (ie. campaigning for this or that policy that will best maintain the system of immigrant reception) that at the same time impoverishes them and vacillates in lending them a hand. To do so would be akin to be the pallbearer while at the same time complaining about the high price charged to the deceased's family.

I'll also answer @estradiolivia's question:

First, an actual and total closing of the border so that no immigration enters is a very exceptional occurence, and even then, there is no real way to completely shut off immigration if there is enough pressure on the migrant, like there is placed on those to the south of the US and of the EU. When bourgeois politicians talk of shutting the border down, what almost always ends up happening is a hardening of the violence, in terms of requisites and violence, but never a complete shutoff.

But even then, let's assume a total closure of the border, nobody is coming into the country. For something this radical to happen, it must be justified to the public (by appeals to nationalism) and spurred on by an extraordinary situation. That extraordinary situation will most definitely be, in the case of immigration, either a sudden influx of migrants or a steady rise in the number of migrants to the point of seriously straining whichever systems are put in place to receive them. This, looked at through a Marxist lens, means that the reserve army of labor has gotten too massive too handle. There is such a thing as too much unemployment, and also too much cheap labor. A capitalist economy, as much as it benefits from and needs a pool of unemployed and cheap workers, also needs for enough work to be done to support that mass of unemployed workers, to the bare minimum of continuing to live, reproducing, and being able to do some kind of work. Not to even mention the discontent that is spread, either intentionally through propaganda or through the imperfect integration of these migrant workers, to both the local and migrant working classes. There is a sweet spot, so to say, for the capitalists, in unemployment, cheap labor, and racist sentiment. They need some to be present, but too much is also harmful to them.

Something I'd consider to be a big step in any communist's theoretical and practical development is the true adoption of class politics, as the main vehicle of your discourse. There is no shame in not having done this, and I'd wager almost any communist had a period of time between consciously adopting marxist politics and this "true adoption" I'm referring to. Some never take this step as well.

Especially if you were already into politics, rejecting the political discourse of bourgeois democracy and substituting it for class politics is something that takes conscious effort. Take immigration as an example, this is a relevant subject of debate in the EU. The two main positions in normal (read: bourgeois) debate is to either make legal immigration harder and murder more migrants, or to relax controls and allow easier legal integration into whichever country they're in. Your intuition as a newer communist is probably to side with the second position, and that's understandable. But a consistently class conscious position is to first understand that those two broad sets of policies (hardening or relaxing the borders) both serve different factions of the same capitalist class at the same time:

Immigration, particularly from global south countries sacked by Europe, serves to increase the reserve army of labor that exerts a downwards pressure on wages, especially from these immigrants whose precarious situations force them to take the harshest jobs for miserable pay. So these two alternating policies of opening or closing up the border (but never closing it) serve to control the size of this reserve army when it's convenient, and once they're in Europe, to utilize this mass of low-wage workers. This is what is at the crux of the bourgeois debate over immigration in Europe, it's just coated in different paints, one nationalistic and one more "humanitarian". And this is what informs the actually marxist position in this particular debate; the rejection of any and all instrumentilzation of our fellow workers for the benefit of the capitalist class. There is no immigration policy within a capitalist framework that does not utilize the cheap labor brought by immigration.

If our goal as communists is to guide the working class to power, then we should be consequent in this and not lose ourselves in debates about which policy the managers of capitalism should adopt, it's to educate workers in our actual positions and utilize these debates as a jumping off point. This is what differentiates communists and opportunists who use workerist rethoric

#seriousposting#I won't answer anything else on this post because it'll get too long. my askbox is open for any replies though :)

770 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tax Lawyer & Immigration Lawyer in Australia – Your Trusted Legal Partners

At IR Legal, we specialize in both Tax Lawyer and immigration lawyer Australia, providing expert legal solutions tailored to your unique needs.

Navigating the complexities of tax laws and immigration policies in Australia can be a challenging task. Whether you are an individual, a business owner, or a migrant looking to establish yourself in Australia, having the right legal support is crucial.

Why You Need a Tax Lawyer in Australia

Australian tax laws can be intricate, and compliance is essential to avoid penalties or legal complications. A Tax Lawyer Australia can assist you in various matters, including:

Tax Compliance & Disputes – Ensuring that individuals and businesses meet their tax obligations while resolving disputes with the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

Tax Planning & Structuring – Advising on tax-efficient structures for businesses, investments, and estate planning.

GST, Income Tax & Corporate Tax – Helping businesses understand and manage their tax liabilities effectively.

Audits & Investigations – Representing clients in audits, appeals, and disputes related to tax assessments.

Our experienced tax lawyers ensure that your financial interests are protected while keeping you compliant with Australian taxation laws.

Expert Immigration Lawyer Services in Australia

Migrating to Australia involves complex visa applications, legal requirements, and government regulations. A skilled Immigration Lawyer Australia can help simplify the process by providing legal guidance on:

Visa Applications & Appeals – Assistance with student visas, skilled migration visas, partner visas, business visas, and more.

Sponsorship & Employer-Sponsored Visas – Advising employers and skilled workers on visa sponsorship requirements.

Permanent Residency & Citizenship – Navigating the pathway from temporary residency to permanent residency and Australian citizenship.

Visa Cancellations & Refusals – Challenging visa refusals and cancellations through appeals and tribunal processes.

Our immigration lawyers stay updated with the latest immigration laws to offer strategic solutions for individuals and businesses seeking to move or work in Australia.

Why Choose IR Legal?

At IR Legal, we combine expertise in both tax law and immigration law to offer comprehensive legal services under one roof. Our team is committed to providing personalized legal advice, helping clients achieve their goals while ensuring compliance with Australian legal frameworks.

Whether you need assistance with tax planning, resolving disputes, or securing an Australian visa, our Tax Lawyer Australia and Immigration Lawyer Australia specialists are here to help. Contact us today:- Visit Us: https://www.irlegal.lawyer/ Call: +64 045661155

Get Professional Legal Assistance Today!

Navigating tax and immigration matters doesn’t have to be overwhelming. With IR Legal by your side, you can confidently move forward with expert legal guidance tailored to your needs.

0 notes