#I love art that implicates the viewer in the narrative

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

What do you think of the theme “we’re all adults here” starz is using

Dear Theme Anon,

That is a beautiful question and I think this is your lucky day: with a tropical night ahead (35C/ 95F - nope, that is not a bra size 😱🤣), we simply live at night, like Superman. So, while I am slowly cooking my famed (but tedious) Circassian chicken recipe for tomorrow night's semiformal dinner, it is with great pleasure that I am answering it.

Please excuse the length. I know what I am able to do when I really like a question and yours got me immediately interested. Thank you for that.

Funnily enough, I was just having a very enriching conversation this afternoon, with a very, very good friend, who is way more intelligent than I, so she has no desire to write any blogs on Tumblr. On the very same topic you raised, Anon. With her permission, I am going to sum up the gist of it (et merci encore à toi 😘😘).

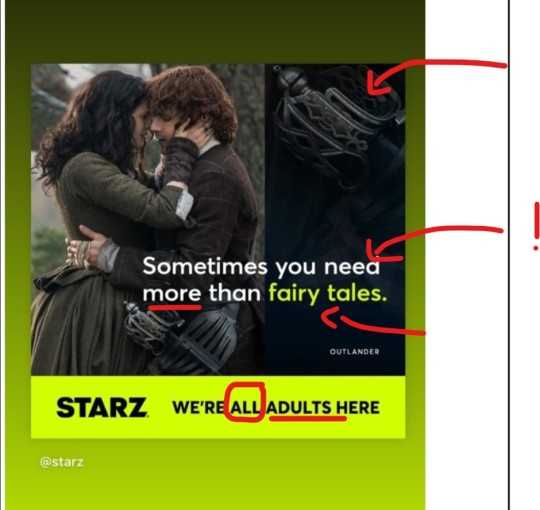

Let's look at that pic again:

The Craigh Na Dun Fateful Dance of Love and Death is one of the most moving pivotal moments of the entire series. Tens of thousands of women have shamelessly cried all around the world, while watching this (haven't you? I know I have and did it with no grace whatsoever, but pinky promise: don't tell anyone else, please). And then watched and rewatched and rewatched to oblivion, with or without that Kleenex box and that Ben and Jerry icecream at the ready.

You know, it's exactly like Shakespeare writes in Romeo and Juliet's Prologue ( I hope I still remember it...): ' A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life'. Love and Death blended together is one of the most powerful narrative tropes that ever existed. So much so, that a guy named Denis de Rougemont even famously noticed that in French, a single letter separates l'Amour (Love) and la Mort (Death), with seminal implications for our Western World mentality, ever since the Middle Ages. For some mysterious reason, we seem to always be caught completely unguarded when exposed to such ultimate injustice.

Tragic magic. This is exactly what also made OL a cult series, irrespective of its (many) unjustified lengths, its (many) moments of uneven acting and its (many, way too many) bullshit pills thrown at an increasingly jaded and bitterly divided fandom. Life imitating Art was just an unexpected blessing and a curse, that much we shippers know, and I am not planning to dwell on it.

But how long can you continue to sell this product almost exclusively to women, all around the world, especially when you are faced with the prospect of a dragging/delayed merger & acquisition (never a good sign) and an increasingly dwindling number of subscribers (never a good sign, either)? I'd think not for too long, really, even if OL still is one of ***'s biggest success stories ever. How long can you pretend to sell a high-end content to 'premium women viewers', when you know very well that you chose to discard that famed 'female gaze', which turned the series' first season into an instant media phenomenon?

Riddle me that: how to sell this product for a profit and expand that fan base while, at the same time, trying not to lose your loyal hardcore viewership?

This is ***'s first answer - I bet this will be followed by some more things, but let's see what it might mean.

On that poster, the focus is still on The Mythical Couple. Selling that good old famed, surreal chemistry - remind those old fans of that moment they felt all those feels (awww....). At the same time, try and create a need out of thin air - 'you need more'. More of what? Sex? Violence? Sexual Violence? Intrigue? Politics? Political intrigue? Ethics? Dilemmas? Ethical dilemmas? All of the above? None of the above? Stupid poster won't tell, but hey: buy me and I'll speak. Buy. Subscribe. We'll think of a way to keep you hooked - at least for the next season and a half. After all, Season Eight is a study in freestyle. After all, we conveniently leaked the info that 'Erself wrote the finale's script (why risk GoT's epic #shitshow?), so all is fine and dandy.

On par with our Mythical Couple, we have that sword. Oversized. Symmetrically featured. Action, with an intelligent twist - that is a finely wrought blade, after all. Uh-oh: that spells a new, more inclusive target. Male audience. 25 to 75, to be more exact , because the only promise the poster makes is a sobering one: 'more than fairy tales'- color me surprised.

After all, 'we're all adults, here'. Key operating words: 'all' (more inclusivity) and 'adults' (not like in X-rated, but more like in 'serious shite').

Well, then. That would require narrative chutzpah and bold choices. That would require a faster paced script, less of those never-ending side stories and borderline neurodiverse focus on irrelevant details (I am still not done with that Fiery Cross and not even ashamed of it, at this point in time) that do plague The Books. And throw rotten tomatoes at me if you wish (I don't care), that would require the end of that horribly robotic directing - we all know what the hell that means.

Will they be able to keep that high-maintenance standard? One thing I am sure of: when you treat your fandom like shite and drag along endless spells of Droughtlander without as little as a bone thrown in for diversion for months in a row, you'd better hone that blade, darlings and go for a kill. Bring it on. Bring that addictive spice back, stat.

It is my humble understanding *** wishes to create an OL universe. Wanna bet the farm that somewhere in their cartons they do entertain the possibility of (at least) a second season of BOMB? S and C cameos could be a breeze to arrange, after all ( we consider this in theory - I happen to think it could be more complicated than that). The story could be duplicated to oblivion - is it way too outlandish to imagine a season devoted to Mandy and Jem's story through several timelines?

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

today's hot take; the general reason people giving for paying more attention to Zuko's character arc and presence in the fandom is usually something like 'its hard to relate to Aang because most people aren't monks, genocide survivors or fundamentally alone, while Zuko's history of family abuse and trying to appeal to a father that never cared for him is much more relatable', and that's honestly NOT a good thing to be saying as if it was a fact

the first point being is that this involves some really broad paint to look relatable at all. Zuko has suffered neglect, physical abuse and mutilation, and a great deal of emotional woes in his family. That is something many people share. However, the SPECIFICS of his life aren't particularly broad for a lot of people; not many people are princes, or heirs to dynastic power that informs their responsibility to the world, or have a complicated sibling relationship because they are competing for royal position, or were specifically in an honor duel that ended with them getting half their faces burned off with spiritual pyrokinetic martial arts powers.

This is, of course, splitting hairs. But that's sort of the thing; the metaphor and idea of Zuko being relatable breaks down if you analyze it too much, because all the details that define him as a character make him dramatically different from most real life people. it informs everything about him, and it seems that in order to take the really broad look that he's used ("Zuko is more relatable because abuse, family obligation and feelings of self-worth and shame are a big part of his character") honestly come off making his character feel... kind of nebulous. You have to focus to actually make his character significant, and removing any aspect of it loses a big part of his character. And that focus also makes him different from most viewers past the whole concept of them projecting onto him making any real sense.

And that's what it comes down to, projecting. And the thing about it is, people aren't any more like Zuko than they are like Aang. They're not royal children (presumably), they don't have firebending powers (again, also presumably), they're not heirs to a throne of dynasty power, and they're also not heirs to a throne of dynastic power in a setting where their destiny and obligation to a world scarred by their ancestors is not abstract at all. Projecting onto Zuko because you can feel some similarity to your own past of abuse is, when you get down to it, a matter of just emphasizing specific aspects of his character.

Aang is not really hard to identity with. He's a fun-loving trickster who wants to shake things up and save the world from itself, suffering under a great deal of loss, isolation and grief; these are many things that can be identified with, every bit as much as identifying with Zuko because of family situations or history of physical and emotional abuse or neglect.

Yes, he's a monk, and yes, he is an incarnation of the spirit of the world itself, with the power over all the spiritual elements and destined to right the wrongs of a world out of balance. This is not something most viewers have; a good majority of viewers are probably not Buddhist either, or schooled in it, and won't understand the attitudes that are important to understand Aang.

But the same thing also applies to Zuko; much as the principles of Buddhist morality and theology underpin Aang's character and the setting itself, Zuko's own situation is also laid out in the story, tied to it in the same way as Aang's character. Relating to either of them is perhaps not a good idea, so much as it is understanding their perspective, character arcs, and cognitive understanding of their feelings and role as characters for the narrative of the series.

I think relating to a character is honestly not the best thing; at its worst, it basically demands that characters conform to you, and ONLY you, with the implication that anyone else is unworthy to have any kind of perspective like that. It's better to understand a character on their own terms.

And in all honesty? Zuko's whole character is not really some pan-universal exemplar of suffering from duty and ancestral crimes. It's laid out through the story very clearly, and the same thing is true for Aang. His story and why it is significant is laid out through the series, its just a matter of listening to it and letting yourself resonate with it, even if its different.

30 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! My name is Grim, and I fancy myself a bit of a researcher. Now, this is not for anything important or extremely serious. Instead, this is mostly for my own pure enjoyment and something I have in the works that is to be posted on Tumblr. You are not obligated to answer any or all of these questions I have posed. I know it’s a bit much. Take your time, but don’t feel obligated to do anything. Feel free to add any additional input! Thanks for your consideration!

1. How different do you think your work would be, in terms of getting across a point, in a different medium thats not Audio RP?

2. How do you think your work would be different if it more reflected main stream industry forms of storytelling where you as a creator would be more separate? (ex. movies, tv shows, games, etc.)

3. How important do you find the voice acting in your work?

4. You are the primary voice of your works. Would you consider taking a step back from voice acting in your work to focus on narrative work?

5. Do you believe your own individual ability to voice characters enhances the story overall?

6. Do you enjoy the idea of a “Listener character” or would you better prefer to not have one?

7. As a writer, how does the writing of the Listener take you out of your comfort zone? (ie their effect in relationships, plot movements, etc.)

8. Is Audio RP your favored form of art?

9. How do you believe Audio RP differs from main stream forms of art/entertainment?

10. Do you believe that your work has over arching themes that relate to you personally? (very optional)

Hello, and thank you for the questions!

How different do you think your work would be, in terms of getting across a point, in a different medium that's not Audio RP?

If I were to create similar storylines in another medium, I think my work would be very different. The major element that all my stories are based around is the Listener. Everything is crafted from their perspective, so I need to always keep this in mind when scripting and editing. The best ways to handle the narrative and dialogue are through implications with other characters and SFX; to keep audios sounding as authentic as possible, this must always be considered when I work. Much of it is filled with the Listener's imagination, but to convey a point with only audio cues can be a difficult task.

2. How do you think your work would be different if it more reflected main stream industry forms of storytelling where you as a creator would be more separate? (ex. movies, tv shows, games, etc.)

I'd allow the story to breathe and marinate due to the platform it's on and the medium the story is told in.

The genre of audio RP, especially on YouTube is already limited because creators are told that in order to keep an audience, we must hook them within the first 10-30 seconds. Due to this, we develop our audios with that in mind; it can come as a detriment to our creativity and desire to show a story in a particular way. We're confined by parameters that value immediate views and responses in order for our creations to be deemed successful, and when many use YouTube as their primary source of income, this manner of thinking can become the norm. In order to stay relevant, we must research what's trendy, what tropes are no longer popular, and though it's not necessary, online demand can change on a dime. Exploring different topics and themes are also limited due to this; creators must work within the platform's restrictions, and that has impeded many stories with how deep I can dive and what it could've become.

As a visual medium—particularly movies and TV shows—my stories would be far better. Viewers can perceive them the way I want them to and with far more understanding. Although SFX and a wonderful soundscape can teleport consumers to another place, the nuances that I love and appreciate slip through the cracks. On a larger scale, visualising the settings, fashions, and people can elevate a story as it gives a plainer context everyone can draw from. On a smaller scale, facial expressions and body language are paramount for communication, something that audio RP cannot do.

An example of this would be my newest series, The Noble Trials. It's a high fantasy world which, in itself, is difficult to show because in that kind of setting, anything goes. I want the audience to experience the extravagant events, the opulent locations, the embellished fashion. Of course, as I depend heavily on sound design, I have faith in the listeners to imagine that for themselves, but they'll never imagine it the way I do. The only option is to write it through dialogue, and sometimes, this can feel unnatural. I'm one to sprinkle in details, so if I decide to create a new fantasy creature, I must show it through SFX and characters describing it. That's not to say it can't be done, but that requires more time and effort; it depends on if a creator is willing to go the extra mile for a little more immersion.

3. How important do you find the voice acting in your work?

I find it extremely important! If I want my audience to be transported, then all elements of the story must be convincing, and the character I voice is no exception. Voice acting is the primary driver of it all; though dialogue can certainly tell the audience something, the way it's expressed is vital to adding a layer of realism. As I can't rely on faces and movement to show a particular feeling, it must be emoted through speech, and that can elevate a story to the next level.

4. You are the primary voice of your works. Would you consider taking a step back from voice acting in your work to focus on narrative work?

I've thought about it but I don't believe it to be a possibility. Most of my community listen to my works because I'm voicing the characters, so it's something I must continue doing. However, writing is my strength and passion. It gives me true joy, so if I was guaranteed my career would be retained and someone else voiced the main character, I would consider it. At this point however, it's not an option.

5. Do you believe your own individual ability to voice characters enhances the story overall?

Though I'd say I'm okay at what I do in terms of voice acting, I know there are others that are far better than I am, and I believe they could take my stories much further. My projects are made with audio dramas in mind, so I think that someone more skilled in voice acting could easily transform a character of mine.

Also, my vocal range is pretty good, but voicing all characters (I've created 18 so far with many more to come) is very difficult. Although the audience know it's one man behind all these characters, as a creator I'm compelled to separate everyone so they don't sound similar. Of course, it's impossible to take note of every modulation the voice makes and consistently use certain intonations where necessary, but there will always be similarities between the characters which, to me, hurts the story if the voice is comparable to another and the audience notice. It makes me want to develop my acting more, but it's quite saddening despite what I must do to make characters sound different (pitch, accent, tone, etc). In this case, I am my own limitation.

6. Do you enjoy the idea of a “Listener character” or would you better prefer to not have one?

The short answer is no, I do not enjoy the idea of a Listener character. As a writer, it limits what a story can convey.

In the beginning, it was a great challenge because I could experiment with how to tell stories through the perspective of someone who doesn't talk. It allowed me to develop different means of showing a narrative through SFX and one-sided dialogue, and to understand the limitations and liberties I could make. However, there's a massive downside: everyone is different. Some creators like the Listener being a blank slate for the audience to fill, and that's absolutely fine; I started out like this too!

But as I sank deeper into adding dimension and story to my characters, I realised that I needed to do the same for the Listeners. They need personality, and desires, and struggles that will inevitably clash with other characters. A blank slate cannot drive a story, nor can they transform it in any way because there's nothing to challenge or change. For my stories, the Listener's personality and interests must have something of substance in order to interact with characters.

However, this also proves to be inconvenient because the audience may not be able to relate. Some listeners like to insert themselves into an audio while others enjoy it from a third-person perspective. Those who listen in the former way can have difficulties with what the Listeners do because it's a stark contrast to who they are, and that can break immersion. Additionally, they can develop characteristics about the Listener depending on their own beliefs of them—by their own reflection or other means.

The most recent example would be Alex's series. Tl;dr of the story: Alex and Gremlin (the Listener's petname) have been together for four years. One day, Gremlin accused Alex of cheating, they were wrong, tensions arose, both were stupid, they broke up, and Gremlin left to who knows where. The latest episode is a dream sequence that explores Gremlin's thoughts about what happened, what they think of themselves, and it reveals other questionable things they've done. As a character, Gremlin suffers from trauma, and this drives them to act in unfavourable ways similarly to Alex. The purpose of this audio was to show that Gremlin is not as good as they seem. Everyone is flawed, and I make sure my characters are no different. But many listeners likely can't imagine themselves screaming accusations at their long-time partner, stalking them, and living with crippling trust issues and anxiety; therefore, in their mind, that doesn't happen in the audio.

If the Listener character was voiced, I think their views would be different, but this is the main factor: No matter how detailed I am, the audience will never see the Listener the way I do. And as I want to write narratives in a specific way to convey a specific idea, that can get lost in translation. That means a Listener character must be predetermined in order to write a compelling story and explore themes and situations I can't do with a blank slate.

7. As a writer, how does the writing of the Listener take you out of your comfort zone? (ie their effect in relationships, plot movements, etc.)

Having been doing this for a few years, I think I have a comfortable grasp on how to write Listener characters. The main challenge is natural dialogue between them and other characters, as well as staying true to the personality I've given them. Different Listener characters would notice or mention certain things depending on who they are, and I must always keep that in mind. But for the most part, it's pretty enjoyable!

8. Is Audio RP your favored form of art?

Absolutely not. My favoured form of art has always been audio-visual in nature because that's what I respond best to. Films and TV shows are where my heart truly lies, but expressing myself through this medium is a privilege I cannot take for granted. It can evoke just as much emotion as other arts, and I find that amazing. Although I love watching things, storytelling keeps me sane, and I always have something to share or create. Audio RP gives me the opportunity to challenge my ideas, expand my knowledge, experiment with characters, and develop other skills such as audio engineering (which I love). But most of all, it lets me offer my stories to the world, and I'm so happy I'm able to do so.

9. How do you believe Audio RP differs from main stream forms of art/entertainment?

It's an interesting art form in its own right because although there are certain elements of story set in stone, for the most part it's personalised. Drawing from the way I create audios, the audience—even if they aren't projecting themselves onto them—is experiencing a story through the Listener. It's a limited perspective, and the only things that belong to the consumer are their thoughts, though it might not necessarily be canon to the plot. Most narratives are told through a camera, and what the viewer sees is carefully crafted for the purpose of the story. However, as Audio RP is told from a second-person POV, curating an experience is far more immersive, and I think there is still room to innovate with this medium!

10. Do you believe that your work has over arching themes that relate to you personally?

Without a doubt! Many characters share parts of me, whether that be likes, dislikes, ideologies, experiences, or even direct memories. It's easy to use yourself or people you know as a basis for characters, then build upon that to make them their own individual with their own journey.

Niall is the best example of this. At school, he was closeted but was outed against his will and bullied for being gay, and his crush (the Listener) at the time stood by and watched it happen. In the present timeline, Niall is a creative with a job that keeps him occupied, but those traumas shaped him into who he is: a socially awkward and wary man without love for the part of him he refuses to show. His fears of trust and making friends governed him, but above it all, he was afraid to accept who he is. His story explores that deep fracture: navigating what it means to forgive, changing a once rigid and cold outlook on the world, and in the end, permitting a chance for healing and closure, and realising that living without love is no way to live.

Though I didn't experience most of what he did, writing Niall was a way for me to also have hope in similar thoughts that I carry. It was somewhat therapeutic—more-so knowing that his story resonated with other people and helped them find some form of catharsis.

Thank you so much for these questions! I'm so sorry I wrote so much omg

41 notes

·

View notes

Note

Having watched Amphibia and thought it over, I guess I can understand why some viewers interpret Marcy's arc as having unfortunate implications regarding her parents, even if I personally don't see her parents as abusive.

Judging by Braly's statements regarding Marcy's father, the job he took that required his family to move out of state was a big 'opportunity' for him. From the way Braly worded it, Mr. Wu took the job not out of necessity, but because he wanted to, which can easily come across as selfish and uncaring, especially since Marcy's house in L.A. already looked pretty well-off.

With that in mind, I can understand why some would object to Amphibia answering this situation with 'Well, things change and it's healthier to accept it, for good or ill, rather than fight it.' In response, some people are like 'Hold up, why are you just ignoring the way Marcy's dad is acting? Surely the right thing to do is have Marcy's dad realize he never needed this job, appreciate what he already has, and start putting what his daughter wants ahead of his own wants.'

Now, a route like that would obviously clash with a story that desires to end with Marcy accepting the move. But looking back on things, I think one of the biggest reasons it's a shame we don't see Sasha or Marcy's parents is that we never get to see how Marcy's dad viewed his own choices. We see Marcy's reaction to it, but we never get to see his side of things.

I mean, what if Mr. Wu thought he was doing a good thing for his family by taking a job he didn't necessarily need? What if he understood he already lived a pretty good life, but believed that, if there was a chance for him to provide an even better life for his wife and daughter, he should take it?

I think there were ways to explore this that didn't make a villain out of the man and still end with Marcy moving. For example; Mr. Wu could learn it's not inherently wrong to desire more for yourself; what's wrong is ignoring/forgetting the feelings of those you love. Meanwhile, Marcy could learn the same lesson as in canon, with the added understanding that her dad, while making mistakes, genuinely thought he was doing good by her by taking the job. Knowing that, as well as her father apologizing, combined with her accepting that distance and time won't mean she loses Anne or Sasha's friendship, makes her more comfortable going ahead with the move. Mr. Wu could still take the job with Marcy's blessing, while promising to do better by her and make a greater effort to understand her better.

Think there was a missed opportunity for a more nuanced story here, or am I looking too deeply into things?

Sorry for the late reply! I think you're very much onto something here.

As someone whose parents decided to move just like so, this specific aspect of Marcy's story bothered me.

With enough time and perspective, as an adult living on my own, I grew to understand why they decided to do so. Despite that, moving as a neurodivergent child was a really traumatic experience for me. I had great friends in my first school, I had a group of peers who had the same hobbies as me and understood me. After the move, it took me many years (until high school) to get something similar again.

My parents also realized how much this hurt me, and while they couldn't undo the move, they did everything to help me through this time and after a few years apologized to me for their decision.

Showing what Marcy's relationship with their parents looked like, would've helped with actually fleshing out the emotional impact of the story.

(Same with Sasha but that is a whole another can of worms)

In the show, the narrative fails at making its points. It's both pro and anti authoritarian. It's trying to play the "respect your culture, respect your parents, be a good child" card and then calls it all off with adding Andrias and his backstory into the mix. It's not thematically coherent. I love children's media but it requires a delicate balance. It's an art of its own, to make a story that's both thematically cohesive and engaging without being overly scholastic.

Marcy does what she does for a good and valid reason. Sasha and Anne are her support network, people who tolerate her quirks and often indulge her even if they aren't even half as invested in her hobbies as she is. Tearing her out of her safe environment is cruel and hinted to be unnecessary. It's a "Parents know what's best for you so don't fight their decisions" moment. Showing something that would balance it out would have made it less harsh and seemingly cruel.

#amphibia critical#long post#ask#we dont even get to see a lot of her perspective at all but shes a character that many relate to for a good reason#her story feels lackluster because they never added the necessary dimensions to it that would make it pop more

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Also 🖊️ any variation on Sounder I miss sier

ARIEL-SOUNDER-ECHO-ARIEL THE OUROBOROS EATS ITS OWN TAIL. If you've been on my blog for a while you probably know sier by name I tag sier Constantly. I love talking about Sounder. Here's some Sounder.

Sounder's a PC from a sleepaway campaign that I was gonna play with some friends but never really ended up happening (scheduling issues etc) but we just kind of. ended up writing the entire story of these characters anyway. Including multiple pieces of writing and Significant amounts of art. Ariel is Sounder before sie became human and also a camp counselor. Echo is Sounder after he dies of love. Ariel is Echo after it becomes fucking normal again. If that doesn't make sense I'm about to explain it in detail aldkjfalkjdf

ARIEL was a wind spirit who served at the pleasure of the Underhill King (fae Old World entity that represents the Old Ways etc. big ass bone stag man). Pronouns... uh. Didn't really need them. It/they is close enough. Its job was to rustle the bone charms and bells that the Underhill King wears on His antlers and that was it.

They found Wallace (another PC, goes by Laevis by the time the campaign would have begun) bleeding out and almost dying in the woods, and made a Deal with the Underhill King for the power to heal his wounds and take care of him as he recovered. Laevis wakes up in the forest to see Sounder over him, hands pressing against the shrapnel wounds in his neck.

[Image ID in alt text; the Underhill King's dialogue is written in small caps and His pronouns are written with a capital H.]

Our Crafter for the campaign decided they wanted the magic for this campaign to work via thread crafts, especially friendship bracelets, so Sounder's humanity being granted via friendship bracelet is pretty significant! The bone pendant and bracelet thread make up the necklace that Sounder wears in pretty much all the art I draw of sier, which is the visible symbol of the deal sie made with the Underhill King. Sie never takes it off. The implication in the passage above is that if Sounder ever finds a true home, sier life will end, as sier life and curse are inextricably bound together. I feel like this may be a good point to mention that Sleepaway is a horror-tragedy ttrpg. btw.

That gets us to Sounder (sie/sier and he/him)! ^^ awesome art above is an art fight attack from @klqdraws !!!!! [Image ID: a waist-up portrait of a tan-skinned, blue-eyed man in a white tank top and yellow skirt. Sie has waist-length black hair with a blue tint, part of which is pulled into a short braid over sier right shoulder. Sie has stubble and multiple ear piercings, and sie is singing and holding out a hand to the viewer. End ID]

SOUNDER is a Songleader (one of the character archetypes from the Sleepaway TTRPG.] Gender: Blowing in the Wind, Name: A Name Used Only Here (the character sheets for sleepaway are hella good). Sie is a cryptid of a camp-counselor -- not on the payroll, never heads home on the buses with the rest of the group; sie just seems to show up to help out when camp begins and everyone's just sort of accepted this. Sounder is a camp nickname given to sier; Laevis (who'd lost his voice in the accident that left him bleeding out in the forest) only refers to sier with a handsign of a fluttering bird. Sie's got a playlist here if you want to check it out.

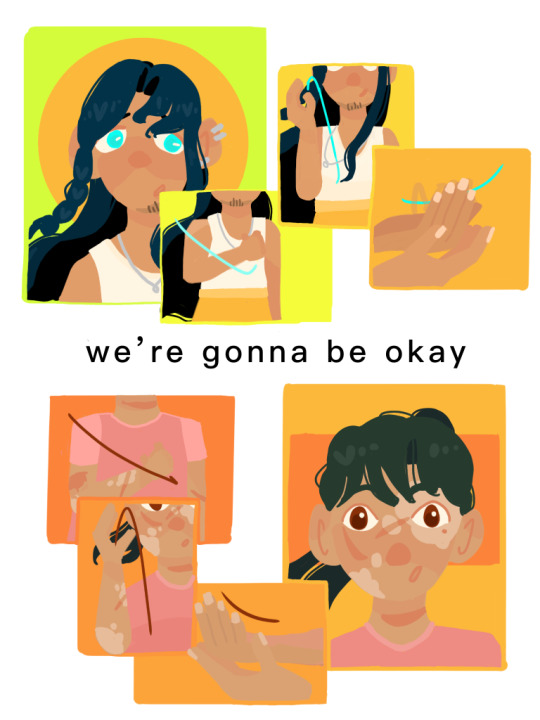

[Image ID: a collection of panels depicting Sounder signing "we're gonna be okay" in ASL, and Laevis, a young man with dark green hair, vitiligo, and small scars all over his body, who echoes the hand signs after them. This is in reference to a mechanic from the TTRPG, the Songleader's hook, which gives characters a mechanical bonus for repeating Sounder's words in a narratively significant way. End ID]

Due to the nature of sier's existence and curse, sie can't stay in human form year-round -- they can only hold human form for so long, turning back into the Wind when they've run out of time to spend with the other campers and counselors. In the off-season, they exist primarily as the wind that rustles through the trees. Laevis, who grew up in the woods with Sounder, has developed a habit of climbing to the top of trees to feel the Wind on his face. He talks to it.

Sie's in a poly love triangle of sorts (souvisel) with two other PCs, Laevis (you've met Laevis) and Joel (or Jay, his camp name). Sounder and Laevis grew up together; Laevis and Joel were childhood sweethearts who never met again after their childhood days at camp together. There's lots of shenanigans here -- Laevis throws Joel into the lake, Laevis falls asleep on Sounder and Joel carries him back to his cabin, Laevis disappears into the woods and Joel searches for him every night because he refuses to believe that Laevis could have died, despite the mounting evidence that he did. Normal polycule things.

Won't spent too much time on Sounder's death since I wrote an entire piece about it; feel free to read it if you're interested (3.5k, about 6 pages)! TLDR; Sounder willingly walks to sier death because sie can't choose to give up the home that sie's found with Laevis and Joel even though it kills sier and Joel wakes up alone in a bed with a discarded flower crown, Sounder's broken pendant, and a wolf who is also his dead boyfriend Laevis. A very bad day to be joel jay sleepaway.

[ID in alt text.]

So. aha. That takes us to ECHO, it/its. It will eventually go by sie/he as well as it/its once it makes its peace with being what's left of Sounder, but that's a ways off. It's got a playlist here also.

[Image ID: Joel, a young man with longer black hair and a short jacket with a broken heart emblem, stares forward with a shocked expression. A white moth has landed on his left eye, covering it. Curled around him is Echo, a translucent white ghostly figure with long hair and a hole where its heart should be. Handwritten text at the top of the image reads "Haunt Me Then." End ID]

Echo is angry. Echo is a spirit of vengeance. Echo is something like the shed skin that Sounder left behind when sie died. Echo's character archetype is Moth Maiden, and it was brought back unwillingly by the moon and is making it everyone else's problem. One of the very first things it does once it begins to exist is kill Joel (somewhat accidentally -- it intended to hurt him, certainly, but Joel was on a journey to the underworld at the time under the condition that touching the water would kill him; its a long story)(you can read the story at the link, credit to @courfeyracs-swordcane , joel's creator, who wrote the story in question).

[Image ID in alt text].

This post is getting pretty long so I won't get too into the Echo relationship dynamics with the rest of the cast (we call them Theseus collectively/as a ship name because they're all dead and different people now. Ship of Theseus kinda blorbos). CJ (Joel after he becomes the Cataract Squire) becomes the Underhill King and Echo is not remotely normal about this. Laevis (who is split into two pieces at the time, Mori and Wolf; it's another Long Story) ascends to a kind of godhood as Hati.

[Image ID: another gorgeous art piece by @lovelandfrogman i received as an artfight attack!!!! The image displays three panels in a descending diagonal from left to right. The first is an image of Sounder and Joel against a backdrop of trees, holding hands and singing together. The second is an image of Echo and Joel against a foggy background. Echo is behind Joel and holding his shoulders; they both seem visibly distressed. Joel is wearing Sounder's necklace. In the final image, Echo, following by moths, holds CJ from behind against a backdrop of the lake. They look tired but somewhat hopeful, and CJ is wearing Sounder's necklace. End ID]

I'm currently working on writing a piece about how Echo becomes Ariel (pt2)(the ouroboros eats its own tail), so I'll probably yell about that later when I get to it, and this post has gotten long enough. If you've gotten this far into the post I love you thank you for reading about my little guy Sounder sleepaway. sie's so important to me <3

I'll leave you with the art Teddy @courfeyracs-swordcane drew me for my birthday of Echo and CJ because it's stunning and I want to put it in here even though I didn't really properly get into the Echo/CJ dynamic (they have a deeply complicated relationship where CJ is wracked with guilt over technically causing Sounder's death and Echo's entire Existence, and Echo hates him for taking the throne of the fae king that cursed Sounder and for the aforementioned Causing Sounder's death, and is fiercely in denial about wanted to be close to them again. They have sex about it. They're almost okay after a few hundred years of this.)(<- from echo's art fight page).

[Image ID: hella good art by @courfeyracs-swordcane of Echo and CJ. Echo is seated side-saddle on a horse and is wearing a flowing white dress and a pink flower crown. It is leaning down towards CJ, who is looking up at it with a scared and hopeful expression on his face. CJ is wearing a jacket over a white binder and ripped jeans, as well as greaves, wrist armor, and a gorget. He has a sword tied to his belt. The background is a forest scene filled with small pink flowers with mountains visible in the background. End ID.]

#pallas post its#long post#yeah i had a lot to say alskdjfalskf im sorry gang#sounder sleepaway#camp azalea sleepaway#sleepaway ttrpg#pallas presents#tagged and credited everyone whose art i put in the post but lemme know if any of yall would rather i take it out

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

2/23 Blog

I’ve seen many of Hayao Miyazaki’s films, but I had not seen “The Wind Rises” so this was an interesting watch for me. Even though the film is set during World War II, it doesn’t show warfare or showcase a narrative of the victims of the war. I honestly appreciated this aspect of the movie because we’ve been watching a lot of films that only focus on the atrocities and violence of war. At its core, the film serves as a profound exploration of love, ambition, and the human spirit, inviting viewers to reflect on the complexities of life and the pursuit of one's dreams. One of the central themes of "The Wind Rises" is the power of imagination and creativity in the face of adversity. Through the character of Jiro Horikoshi, Miyazaki portrays a passionate visionary whose love for aviation fuels his relentless pursuit of excellence. Despite facing numerous obstacles and setbacks, Jiro remains unwavering in his dedication to designing the perfect airplane. His unwavering commitment serves as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the transformative power of creativity in shaping the world around us. However, beneath its surface beauty lies a deeper exploration of the human condition. Jiro's passion for aviation is juxtaposed with the harsh realities of war, forcing him to confront the moral implications of his creations. As he grapples with his conscience, Jiro learns that true greatness comes not from the pursuit of glory, but from the ability to find beauty and meaning in the face of adversity. Another theme illustrated in "The Wind Rises" is the theme of love and its capacity to inspire and sustain us in the face of adversity. Jiro's romance with Naoko, a young woman battling a life-threatening illness, serves as a reminder of the fleeting nature of life and the importance of cherishing every moment. Their love story unfolds against the backdrop of a turbulent world, offering a beacon of hope amidst the chaos and uncertainty. Finally, a nice touch to the movie was the art style and animation which is always present in Hayao Miyazaki's films. There is a lot of attention to detail and I like that there is a sense of realism in the background even though it's animated.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

To Boldly Go: A Camilla Noceda Character Analysis

I am of the opinion that Vee Noceda might hold a record for how fast a fandom changed their opinion on a character that they once considered untrustworthy and suspicious (and I’m sure the very intentional casting of the 2010s’ most sympathetic voice for a shapeshifter helped with that) but in terms of characters we already knew, very few other shows handled the reveal of a character’s true depth better than Thanks to Them did with Camilla Noceda. And a significant portion of that-at least from what I’m interpreting-is inherently linked to another major reveal of the episode: that Camilla and Manny Noceda were both involved in the early generation of what basically amounts to Star Trek fandom.

Bear with me here, and let me explain. (Info/theory dump under break)

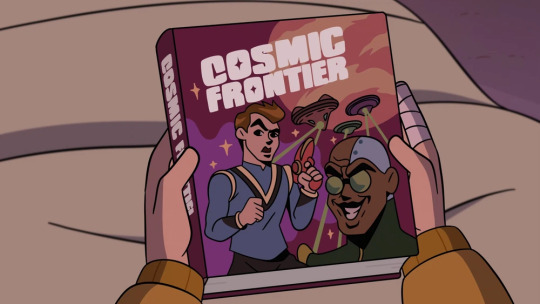

When Cosmic Frontier is first mentioned in the episode, it’s in the context of Gus pointing out the similarities to their current situation. When he lists names like Captain Avery and Chief Engineer O’Bailey, the Trek fans watching (particularly those familiar with DS9) have a little chuckle about the reference and how Gus and Hunter will definitely identify with the characters, assuming that will be the extent of this amusing copyright-friendly shout out.

And then Gus reveals the closet, and we learn so much about Luz’s parents in this one brief shot (though I’m sure the TOH crew would’ve preferred a full episode):

The sheer amount of merchandise, years upon years of ‘Galaxy Con’ loot and collectables and homemade props The amount of guest lanyards, each from a different summer of memories.

The subtle but important suggestion that Manny had worked hard to update and improve his Circuit cosplay, countless hours of research and studying paused frames and crafting the fine details.

The implication of Camilla getting prepared in a hotel bathroom, making sure her turquoise body paint was properly sealed and Manny’s mask was comfortably positioned before heading out to the familiar sanctuary of the convention hall.

The realization that some viewers might have, a link between Star Trek’s real-life impact on how many people who watched the show would later pursue scientific and medical careers and Camilla’s current job as a veterinarian.

How narratively fitting, that a girl who engages so passionately in modern fandom traditions like AMVs and commissioned fan art would be the child of two people who shared a love of the fandom that started it all, and quite possibly was how they met in the first place.

But then we wonder, why is this all hidden? What would cause Camilla to hide these clearly still important relics of her past down in the basement?

We get part of the answer soon enough: She grew up, became a parent, and became far more conscious of how other people perceived and judged both herself and Luz. She tries being supportive of her daughter’s enthusiastic interests and strange habits, but social and societal pressure, along with the weight of her own past regrets, causes her to try to steer Luz away from making the same “mistakes” that she once did.

Though, maybe when Luz was younger, she had a bit of time to go back to old habits. Manny’s enthusiasm would’ve been infectious, helping her remember the good times instead of dwelling on the bad. Perhaps one night they hired a babysitter for Luz and managed to watch a movie that, despite its unfortunate choice of lead actor, was an affectionate parody of Cosmic Frontier that showed its appreciation for what the series meant for its actors and fans.

But without Manny, that spark of enthusiasm and nostalgia wouldn’t last long. Every record and reminder of what Camilla used to share with him would be boxed up, hidden, and left behind as another childish pursuit that she couldn’t afford to waste time on as a single mother.That plan to bury that part of herself deep and never let it grow too much within Luz might have continued as she expected, but Manny, fortunately, had other ideas. He must’ve recognized that spark of creativity and passion within Luz, he surely knew what would be left behind once he was gone.

So he leaves Luz a gift, a memento, something that she would identify with and obsess over and create social bonds through like he and Camilla once did with Cosmic Frontier.

And wouldn’t you know it, ol’ Circuit’s calculations were correct. Luz becomes hooked, enamored, she sees herself within Azura like her parents must have identified with their favorite show’s characters.

Her love of the series is a constant theme throughout The Owl House, it inspired her to express herself, face challenges, make friends, defend the people she loves, and find someone who enjoys the fandom enough to understand her like nobody else could.

What does Camilla do in response to her daughter’s newfound hyper-fixation?

She supports Luz, as much as she can, despite the weight of expectation on both of them. Helping her buy the next books, the new merchandise, even costume parts. One year, not long after they move to Gravesfield, they manage to have enough money to buy convention tickets. Entirely for Luz’s sake, of course, Camilla is too old for this sort of thing, and hardly recognizes most of the characters kids are dressing up as nowadays. But if her eyes linger on some familiar faces at the autograph tables, or she starts absentmindedly humming along to a certain show’s theme song being played over the loudspeakers, well, that’s her business. Old habits are hard to shake.

Speaking of which, I only noticed this after a rewatch, but Camilla’s fandom experience arguably makes an appearance earlier in the series:

When Jacob’s doing his whole ���delusional defeated villain trying to claim he’s the hero” bit, Mrs. Noceda’s response before delivering the righteous justice of La Chancla is “Yeah...a lot of bad guys say that.” On first watch I thought this was simply calling out IRL examples of scumbags with a self-centered ego, but later I realized she’s commenting on it in terms of its use as a somewhat cliche trope. As if she’s watched and read this kind of speech dozens of times before.

For a long time, possibly almost a decade, Camilla manages to avoid directly confronting her past. She works as much as she can to support Luz, the forbidden relics are locked away downstairs, everything’s fine. But then the Hexside Kids show up at her doorstep, bringing with them a bit of the same Boiling Isles culture that allowed her daughter to express herself freely.

She tries to keep it quiet, awkwardly denying any knowledge of the merchandise in her basement, but these new kids are her kids too, for now, and she supports their interests as much as she did with Luz. So if Hunter needs help stitching together an Engineer O’Bailey cosplay, or Gus needs some show-accurate props for his own outfit, well. She’s just being supportive, in a neutral and parental way, that’s all.

Once the portal is open and Luz starts to say something she’ll regret, however, Camilla can’t maintain the facade of a responsible, respectful, socially acceptable parent any longer. That old spark within her, the part that never really left, shows itself more than it has in years.

She offers an alternative, something Luz would’ve never expected, defiantly and proudly stating that she’d be going into the portal to the Isles alongside them. It’s the specific wording that gets me, though, “It is our DUTY to help your friends get back to their families!” Seems to invoke the sort of “I’ll be your fearless champion” type speeches that Luz sometimes makes. However, we recall from Yesterday’s Lie that Camilla knows she isn’t great with on-the-fly improvised roleplay scenarios. She’s “not imaginative enough”. So it’s entirely possible that Camilla’s taking inspiration from lines that she hasn’t heard in a while but still knows by heart, after hearing it recited at the beginning of hundreds of episodes. A socially acceptable single mother and hard-working veterinarian would never consider something like this, it’s too risky, too dangerous, too many unknown variables on the other side of that portal.

But Camilla Noceda grew up watching others face the unknown, for the safety of others, because it was their duty. Their “ongoing mission”.

She might not understand anime yet, but for Luz’s sake and Manny’s legacy, she’s willing to learn.

#Camilla skyrocketed to the top of the Best Disney Moms list for a lot of people and for me personally this is why#camilla noceda#toh spoilers#toh speculation#the owl house spoilers#the owl house season 3#character analysis#manny noceda#luz noceda#hunter noceda#gus porter#the owl house#star trek#cosmic frontier#star trek deep space nine#star trek the original series#fan theory#disney channel#Cartoons#thanks to them#toh thanks to them#long post.

123 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’m sorry if this sounds rude but why should eris’s message have been to so someone other than drifter? Did ikora go camping with eris in the disciple’s bog? Did mara wield stasis with elsie on europa? I’m not trying to sound like a dreris shipper by any means but drifter is the one to talk to about this situation. He helped her make the nightmare harvester and is the one she would follow up with about its application. I agree with the rest of the take but I really don’t get this part at all

If she thanked him for his help studying the darkness/egregore & friendship I wouldn't have an issue with it. That would have made perfect sense within the narrative and been a nice piece of development for their friendship dynamic.

The implication that Drifter was a catalyst for a major positive change in her outlook on life is the part that frustrates me, given we have seven years of lore involving Ikora (mainly) and Mara helping Eris along on her path of recovery. "For so long I believed peace was beyond my reach. No more. I have found it in guiding others down the same path that saved me" would have been a stellar emotional payoff to Ikora's years-long mission to help Eris regain some sense of peace and happiness in her life. It would have made more sense for Mara to be the one Eris invited to the Pyramid with her, given their system-spanning journeys to track down and study them.

So why didn't it?

It's a rhetorical question, but I would offer that art doesn't occur in a vacuum, and while I definitely don't think, or want to suggest, sexism is at play, there's a compulsion in every level of media (executives to fans) toward prioritizing relationships between men & women over women & women. It's another reminder that even generally progressive fandom spaces will never be easy ground for people who want to explore women's relationships, and we'll always have to fight heavy headwinds.

There's also something ... not great? about the idea of a man providing emotional closure to a woman struggling with trauma & mental illness when hitched to a fan interpretation of romantic subtext. None of the interpretations are good: that what a woman needs is a guy to get her back on track, that men and women can't have emotionally gratifying friendships, and that friendship alone can't be a catalyst for positive change. This one is especially tricky because men and women's interactions will overwhelmingly be read as romantic even when explicitly platonic in the text, while anything short of an onscreen kiss will leave viewers debating whether two close women are in love or just good friends. I want more men's and women's friendships, but can't have them because they're always read as romances, which makes me wary of women's and men's friendships in media . . . ad infinitum.

For my part, I like Eris' and Drifter's friendship, but want to see it explored in a way that doesn't make it The Definitive Eris Friendship And Raison D'être which it's kind of been for the last two years. (Identical statement, in reverse, for Drifter.) I want to see Ikora and Eris get more than scraps of meaningful lore. I would like to see Mara and Eris get screentime together. If I could wave a magic wand there would be balance, equal exploration of all of these relationships but . . . it doesn't happen for whatever reason.

Maybe this is a long standing Bungie writing issue, because I'm certain if I was in the fandom back in the TTK days I'd be penning an essay about "so random xD" blue robot eating up most of the expansion dialog and playing Eris' foil. But I can't help but think the quality of women's interactions have kind of gone downhill since like ... Shadowkeep. It's demoralizing.

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

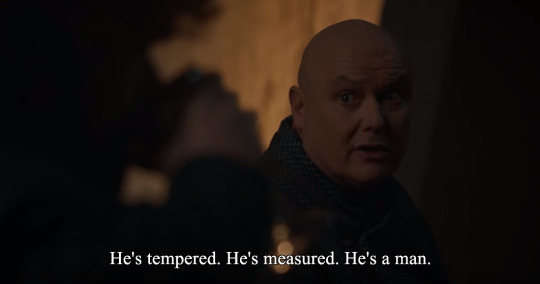

Listen, I might be playing the devils advocate, but I don't think Dany's fate in the GoT finale was due to D&D being sexist.I think it was just because D&D can't write for crap.

It’s not about intent.

Allow me to begin by saying that I completely understand the knee-jerk reaction that people have to the term ‘sexism’. It’s very polarizing, and when men read the term, they immediately go on the offensive. That’s not what I want at all. I don’t use the term to alienate or exclude men, I use it because it’s the dictionary definition of what I’m trying to convey:

sex·ism (noun): "prejudice, stereotyping, or discrimination, typically against women, on the basis of sex.“

That said, allow me to play devil’s advocate here and say that I do not believe the writers intended to have an underlying sexist message. They are more oblivious than they are malicious. It is born of sheer ignorance (lack of knowledge or information) and the privilege to ignore it because, as males, it doesn’t affect them.

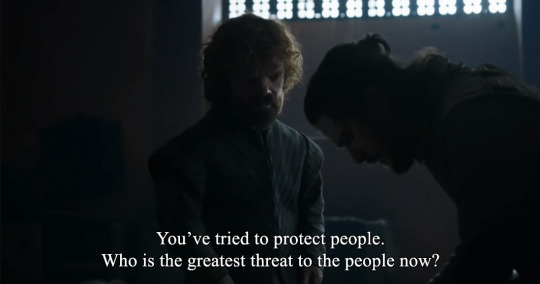

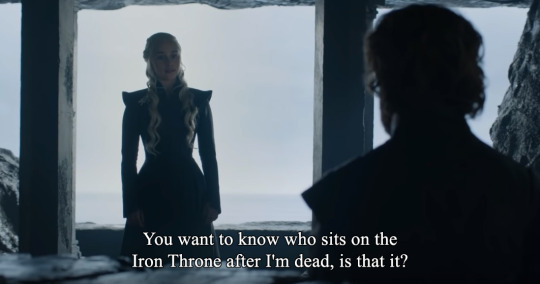

Let’s put aside the dozens of articles that came out after the finale calling out the sexism. You guys know me, I like to pull receipts, cite my sources, and throw in some visuals to help aid my point.

For most of the 70+ hours of Game of Thrones, Daenerys actually does not fall victim to these sexist tropes. Honestly, that is what subverted my expectations for seven seasons. That Dany always teetered on the edge of these tired, overused tropes about women, yet she remained steadfast in her ruthless yet good nature, her moral compass was always aligned even if it didn’t match the viewers, and she was a gods-damned hero, straight through to episode four of season eight.

But the demoralizing reality is that Daenerys was hit with trope after trope in the last three episodes. In the final hours of the show, the writers pulled a bait-and-switch, giving us a ‘shocking’ heel-tern whose only foreshadowing was a very bad retcon job full of double standards. And so many fans, such as yourself, justify it. Not because the show foreshadowed it, but because these tropes are so, so ingrained in our brains from decades of media feeding us these narratives that we now expect them.

In the end, Daenerys succumbs to numerous sexist tropes:

'God Save Us From the Queen’ trope

“The Good Kingdom: A lovely, wealthy country ruled by a benevolent king, a wise prince, and a fair princess loved by the populace. But what’s that? There’s a queen? Oh, brother, we’re in trouble.”

Disposable Woman trope

“This character has a familial or romantic relationship with a protagonist, which allows creators to derive heart-wrenching sorrow from her death.”

Evil Infertile Woman trope

“Women are often divided into "breeders” and “the barren,” with the latter coming off as cool and distant at best, and malicious and desperate at worst.“

The Double-Standard Trope

"A double standard occurs when members of two or more groups are treated differently regarding the same thing. Gender is one of the most common causes of double standards.”

Hysterical Woman trope

“This trope characterizes women as less rational, disciplined, and emotionally stable than men, and thus more prone to mood swings, irrational overreactions, and mental illness.”

Woman Scorned trope

“What’s the only type of woman more dangerous than a Mama Bear? A woman who’s been dumped or otherwise done wrong by her significant other. Especially if she’s been hiding some sanity problems.”

Women Are Delicate trope

“Even if women have toughness, competence, strength or stability, it’s less than what their male peers are capable of.”

The Woman Wearing the Queenly Mask trope

“They don’t want a young woman, or they don’t want any woman, or they just don’t want this particular woman on the throne.”

Tropes in and of themselves are not bad, but very outdated tropes that are associated with the emotional or mental ‘fragility’ of women are. Why? Because they reinforce deep-seated and subconscious stereotypes of women that audiences hold.

“It’s just a show/book! Who cares!”

People have been turning to art (including literature) for years for meaning, for philosophical guidance. Most people in my own country turn to one book to both find and justify their morality (the bible).

“Literature offers not just a window into the culture of diverse regions, but also the society, the politics; it’s the only place where we can keep track of ideas.”―Reza Aslan

It’s not just a show. The art and media we consume helps shape who we are, for better or worse. When men refuse to consider the consequence of their sexist narratives simply because it doesn’t affect their own lives, it inadvertently causes harm for others who don’t share their privilege.

And it’s not just Daenerys. She’s just the figurehead.

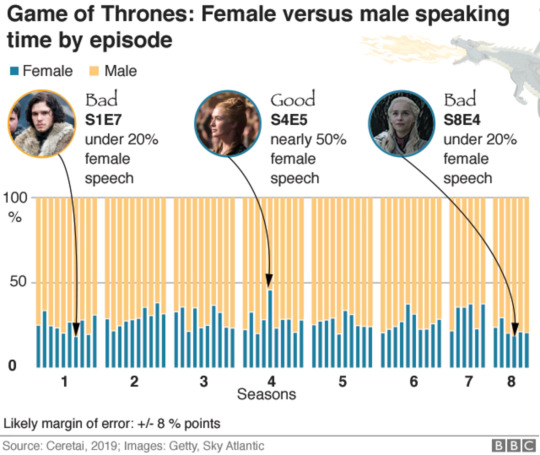

There was a great article from BBC about how much women actually speak on Game of Thrones:

I can already hear the counter-argument brewing…

“So what? There are more male characters!”

Yeah. There are. And that’s a problem, too.

Of the top-grossing 1,200 films from 2007 to 2018, 28% of films were led or co-led by women. Meanwhile, around 49.6 percent of the world’s population is female.

By featuring so few women and by giving women who are featured 20% of the airtime to speak their minds, the writers are unintentionally devaluing the speech and opinions of women. This inspires the audience to devalue women in a subconscious way.

Whether or not it intended to, Game of Thrones and its shocking 'heel-turn’ has very troubling sexist and political implications (amongst other things).

Go ahead, tell me I’m wrong. Tell me I’m blowing this way out of proportion.

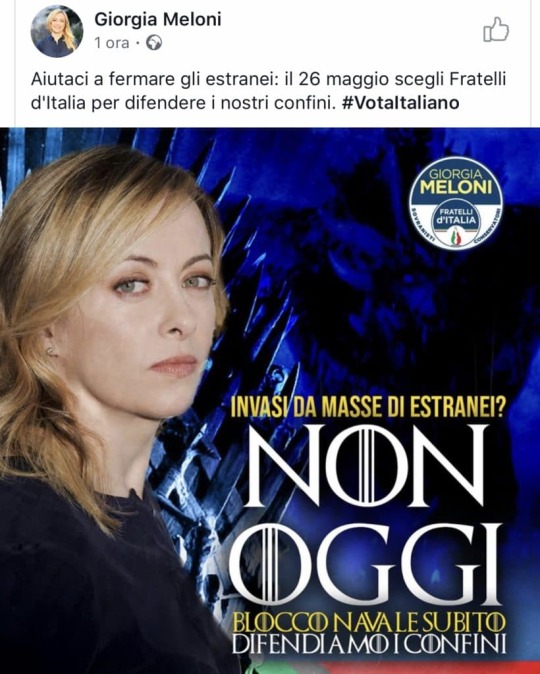

Tell me it’s just a show or a book and every single fan knows how to separate fiction from reality (they don’t, go look at Maisie William’s Instagram comments following her season eight sex scene for proof of that). Meanwhile, here in actual reality, we see things like this:

@thescarletgarden1990 informs me that over in Italy, political figures are using Game of Thrones advertising in their campaigns, too:

Translation: “Invaded by masses of Others? Not Today. Immediate naval block, let’s defend our borders.”

What makes it worse is that, at least Donald Trump, identifies with House Stark. Or, those who rule the northerners. The people who showed their blatant racism toward the only two black named characters. And the writers never bothered to critique the problematic behavior, instead, rewarding their people with independence and driving those pesky evil foreigners ’back where they belong’.

I’ve barely had time to scroll my dash and I’ve already seen a troubling amount of harassment towards Dany fans via anon asks (including myself, though I just block the IP and delete but I wish I’d saved them for proof).

Why? Because the ending justifies their personal narrative, this bad writing confirms their worldview. Meanwhile, on the other side of the spectrum, the same thing is happening in reverse in response to the takedown of a figure like Daenerys Targaryen:

“Khaleesi’s heel turn is particularly troubling for fans who might have felt a true sense of connection to her character following her epic story arc, which has seen Dany escape some awful circumstances to literally walk through fire, free the slaves, bring Dragons to the north and help rally the troops to defeat the Night King. She has basically been Abraham Lincoln, Hercules and Winston Churchill combined into one person riding a dragon.” (x)

The point here is that the show is doing its audience of 19,300,000 viewers a great disservice by succumbing to very outdated tropes and double standards, and sending troubling messages as a result. For instance, a woman can do countless heroic or selfless things, but you should never trust her! She needs to be tempered. Women cannot wield power responsibly. There are endless messages you can take away from this ending and the dialogue that led us to the show’s conclusion (my personal favorite being ‘Cocks are important’).

And the fans who want to say 'you’re overreacting’ to everyone who speaks up against it are only aiding in this ongoing legacy of 85% male writers who get to tell our stories, poorly, and reap all the rewards.

Sure, all of this could be solely the result of ‘just bad writing’…

Nevertheless, it is what it is.

#answered#anti got#anti d&d#daenerys targaryen#daenerys defense squad#game of thrones#got#season 8#sexism#i have a boatload of asks i will get to later eep!

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ophelia By the Yard

Cobwebbed passages and wax-encrusted candelabra, dungeons festooned with wrist manacles, an iron maiden in every niche, carpets of dry ice fog, dead twig forests, painted hilltop castles, secret doorways through fireplaces or behind beds (both portals of hot passion), crypts, gloomy servants, cracking thunder and flashes of lightning, inexplicably tinted light sources, candles impossibly casting their own shadows, rubber bats on wires, grand staircases, long dining tables, huge doors with prodigiously pendulous knockers to rival anything in Hollywood.

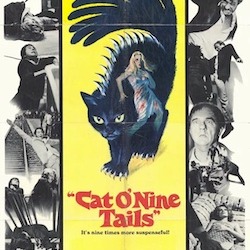

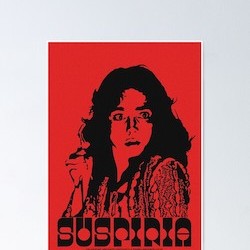

Here was the precise moment — and it was nothing if not inevitable — when the darkness of horror film, both visible and inherent, leapt from the gothic toy box now joined by a no less disconcerting array of color. The best, brightest, sweetest, and most dazzling red-blooded palette that journeyman Italian cinematographers could coax from those tired cameras. Color, both its commercial necessity as well as all it promised the eye, would hereafter re-imagine the genre’s possibilities, in Italy and, gradually, everywhere else.

When color hit the Italian Gothic cycle, a truly new vision was born. In Hammer films and other UK horror productions, the cheapness of Eastmancolor made it possible for blood to be red. Indeed, very red. And, while we shouldn't underestimate the startling impact this had, it was a fairly literal use of the medium. In the Italian movies, and to a large extent in Roger Corman's Poe cycle, color was an unlikely vehicle to further dismantle realism rather than to assert it. Overrun with tinted lights and filters, none of which added to the film’s realistic qualities, the movies became delirious. In Corman's Masque of the Red Death, we learn of an experiment that uses color to drive a man insane; it seems that filmmakers like Corman and Mario Bava were attempting the very same trick on their audiences.

The application of candy-wrapper hues to a haunted castle flick like The Whip and the Body adds a pop art vibe at odds with the genre, and when you get to something like Kill, Baby...Kill! the Gothic trappings are barely able to mask a distinctly modern sensibility, so much so that Fellini could plunder its phantasmal elements for Toby Dammit, fitting them perfectly into his sixties Roman nightmare.

Blood and Black Lace brings the saturated lighting and Gothic fillips into the twentieth century -- a sign creaking in a gale is the first image, translated from Frankensteinland to the exterior of a contemporary fashion house. A literal faceless killer disposes of six women in diabolical ways. The sour-faced detective remains several deaths back on the killer’s trail because the movie knows its audience, knows that it has zero interest in detection, character, motivation — though it’s all inertly there as a pretext for sadism, set-pieces of partially-clad women being hacked up, dot the film like musical numbers or action sequences might appear in a different genre.

Since the 19th-century audience for literary Gothic Horror was comprised of far fewer men than women, would it be fair to ask whether Giallo’s advent might be an instrument of brutal violence, even revenge against “feminine” preoccupations? Consider 1964’s Danza Macabra, the film’s amorous vibes finding their ultimate source in that deathless screen goddess named Barbara Steele, whose marble white flesh photographs like some monument to classicism startled into unwanted Keatsian fever. Her presence practically demands that we ask ourselves: “Who is this wraith howling at a paper moon?” In other words, is it a coincidence that Steele’s “Elizabeth Blackwood” — a revenant temptress and undead sex symbol — hits screens the very same year as Giallo, which would transform Italian cinema into a decades-long death mill for women?

The name “giallo”, meaning yellow, derives from the crime paperbacks issued by Italian publisher Mondadori. The eye-catching covers, featuring a circular illustration of some act of infamy embedded in a yellow panel, became utterly associated with the genre of literature. These books were likely to be by Edgar Wallace, the most popular author in the western world, or Agatha Christie: cardboard characters sliding through the most mechanical of plots; or classier local equivalents, like Francesco Mastriani or Carolina Invernizio. The founding principles laid down concerned the elaborate deceptions concealed by their authors, traps for the unwary reader, and the use of a distinctive design motif. The tendency of the characterisation to lapse into sub-comic-book cliché, the figures incapable of expressing or inspiring real sympathy, was, perhaps, an unintended side-effect of the focus on narrative sleight-of-hand.

When Italian filmmakers sought to translate sensational literature to the screen, they looked to other filmic influences: American film noir, influenced by German expressionism and often made by German emigrés (Lang, Siodmak, Dieterle, Ulmer); and the popular krimi cycle being produced in West Germany, mostly based on Edgar Wallace's leaden "shockers." These deployed stock characters, bizarre methods of murder, deceptive plotting, and exuberant use of chiaroscuro, the stylistic palette of noir intensified by more fog, more shafts of light, more inky shadows. A certain amount of fun, but different from the coming bloodbath because Wallace, despite somewhat fascistic tendencies, is anodyne and anaemic by comparison. No open misogyny, a sadism sublimated in story, a touching faith in Scotland Yard and the class system. In the Giallo, Wallace's more sensational aspects are adopted but made to serve a sensibility quite alien to the stodgy Englander: people are generally rotten, the system stinks, and crime becomes a lurid spectator sport served up to a viewer both thrilled and appalled.

The Giallo fetishizes murder. But then, it fetishizes everything in sight. Every object, every half-filled wine glass and pastel-colored telephone, is photographed with obsessive, product-shot enthusiasm. Here, it must be emphasized that design implicates the viewer as the Italian camera-eye gawps like some unabashed tourist. Knife, wallpaper, onyx pinky ring — each detail transforms into an object made eerily subject: a sentient and glowering fragment of our own conscience, staring back at us in the darkened theater and pronouncing ineluctable guilt. And yet, for the directors who rode most dexterously the Giallo wave, homicide was something one did to women. Indulging in equal-opportunity lechery was merely an excuse to find other, more violent outlets for their misogyny. Please enter into evidence the demented enthusiasm for woman-killing evinced by Dario Argento, Mario Bava, Lucio Fulci, et al. — whatever trifling token massacres of men one might exhume from their respective oeuvres are inconsequential. Argento’s defense, “I love women, so I would rather see a beautiful woman killed than an ugly man,” should not satisfy us, and hardly seems designed to (also bear in mind Poe’s assertion that the death of a beautiful young woman was the most poetic of all subjects).

Filmmakers like Argento have no interest in sex per se. Suffering seems inessential, but terror and death are key, photographed with the same clinical absorption and aesthetic gloss as Giallo-maestros habitually apply to their interior design. Here, it must be emphasized that design implicates the viewer as the Italian camera-eye gawps like some unabashed tourist. Knife, wallpaper, onyx pinky ring – each detail transforms into an object made eerily subject: a sentient and glowering fragment of our own conscience, staring back at us in the darkened theater and pronouncing ineluctable guilt. That’s one important subtlety often lost amid Giallo’s vast antisocial hemorrhage.

Like a river of blood, homophobia, in the literal meaning of fear rather than hatred, runs through the genre. Lesbians are sinister and gay men barely exist. As we try to work out what in hell the Giallo is really up to, little dabs of dime-store Freudianism seem sufficient.

The filmmakers’ misogyny could be suspect, a sign of compromised masculinity, so they need fictional avatars to cloak their own feverish woman-hating. The subterfuge is clumsy at best, the desultory deceit embarrassingly macho. Giallo’s visual force, powerful enough to divorce eye from mind, is another matter, leaving us demoralized and ethically destitute; our hearts beating with all the righteous indignation of three dead shrubs (and maybe a half-eaten sandwich).

The Giallo is founded on an unstated assumption: the modern world brings forth monsters. Jack the Ripper was an aberration in his day, but now there's a Jack around every corner, behind every piece of modular furniture, every diving helmet lamp. Previously, disturbing events arose from what Ambrose Bierce called The Suitable Surroundings, or what the mad architect in Fritz Lang's The Secret Beyond the Door termed, with sly and sinister euphemism, "propitious rooms." There's the glorious line in Withnail and I: "That's the sort of window faces appear at." But now, in the modern world, evil occurs in the nicest of places, and tonal consistency died in a welter of cheerful stage blood. One needn’t enter an especially Bad Place to meet one’s worst nightmare, or perhaps better to say: the whole bright world qualified as a properly bad place. Imagine the pages of an interior design magazine invaded by anonymous psychopaths intent on painting the gleaming walls red.

Though the victims are overwhelmingly female and their killers male (Argento typically photographed his own leather-gloved hands to stand in for his assassin’s), when the violence becomes over-the-top in its sexualized woman-hating (like the crotch-stabbing in What Have You Done to Solange?), it’s usually a clue that the movie’s murderer will turn out to be female: a simple case of projection. Only Lucio Fulci, the most twisted of the bunch, trained as a doctor and experienced as an art critic, not only assigns misogyny to a straight male killer (The New York Ripper) but plays the killer himself in A Cat in the Brain. Though, in another self-protecting twist of narrative, all psychological explanations in Gialli are bullshit, always. Criminology and clinical psychology are largely ignored, and Argento has a clear preference for outdated theories like the extra chromosome signaling psychopathy (Cat O’Nine Tails). Did anybody use phrenology, or Lombroso’s crackpot physiognomic theories, as plot device?

A tradition of the Giallo is that the characters all tend to be dislikable, something Argento at least resisted in Cat O’ Nine Tails and Deep Red. With disposable characters, each of whom might be the killer and each of whose violent demise is served up as a set-piece, this distancing and contempt might just be a byproduct of the form rather than a principle or ethos, but it’s of some interest, perhaps mitigating the misogyny with a wash of misanthropy. A Unified Field Theory of Gialli would find a more deep-seated reason for the obnoxious characters as well as the stylized snuff and the glamorous presentation. What urge is being satisfied, and why here, now, like this?

Class war? Though prostitute-ripping is encouraged in the Giallo, most victims are wealthy, slashed to ribbons amid opulent interiors. Urbane characters who might previously have graced the sleek “white telephone” films of forties Italian cinema were briefly edged out by neo-realism’s concentration on the working class. Now these exquisite mannequins are trundled back onscreen to be ritually slaughtered for our viewing pleasure.

Victims must always be enviable: either beautiful and sexy or rich and swellegant, or all of the above, so the average moviegoer can rejoice in their dismemberment with a clear conscience. Mario Bava bloodily birthed the genre in Blood and Black Lace (1964), brutally offing fashion models in a variety of Sade-approved ways, the killer a literally faceless assassin into whom the (presumed male) audience could pour their own animosities without ever admitting it, with the female killer finally unmasked to provide exculpatory relief.

If narrative formulas absolve the straight male viewer, compositions have a way of ensnaring him. Beyond that omnivorous indulgence of sensation for its own lurid sake one finds in Giallo, there is a more gilded emphasis placed on Beauty (in the Catholic sense), and it is only the women who are mounted upon its pedestal. That these avatars of beauty are to be savored, ravaged, and brutalized — in that order — is what concerns us. But the sex and the suffering that captivates most sadists is never what registers; no, it is the instance of death, the terror that afflicts the dying woman’s face that resonates. Once again, physical interiors become a negative form of emotional interiority, rooms amplified for the sole purpose of grisly annihilations; a kind of heretical, strictly anti-Catholic transcendence through amoral delight in what otherwise falls under trivial headings, either “the visuals” or “color palette” – neither of which touch the essential nerve endings of Giallo.

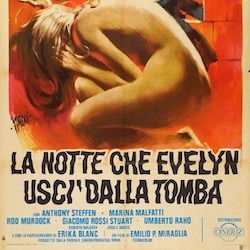

Swaddled inside an otherwise hyper-masculine castle lies a windowless chamber with feminine, if not psychotic, decor. Before he tortures and stabs her to death, “Lord Alan Cunningham” (fresh from his sojourn in the asylum) brings his first victim to this pageant of off-gassing plastic furniture, the single most obnoxious vision ever imposed on gothic environs. Risibly overblown ’70s chic rules The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave with nods to Edgar Allan Poe, as the modish Lord juggles sports cars and medieval persecution. Laughs escape the viewer’s throat in dry heaves when each new MacGuffin devours itself without warning. Take “Aunt Agatha” (easily two decades younger than her middle-aged nephews) suddenly rising from her motorized wheelchair, clobbered from behind seconds later, her body dragged into a cage where foxes promptly munch her entrails. Nothing comes of this. The phony paralysis, the aunt’s role in a half-dozen mysteries, which include a battalion of sexy maids in miniskirts and blonde Harpo Marx wigs – all gulped, swallowed.

About the only thing we know for certain is that “Aunt Agatha” is gorgeous. Though, in the end, she’s another casualty of the same nihilism that crashes Giallo aesthetics headlong into Poe country. That is into “Lord Alan” and his gaudy room crowded with designer goods to be catalogued in a horror vacui of visual intrusiveness – a trashy shrine to his late wife, the titular Evelyn. If lapses of good taste define The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave, they also reflect Giallo’s abiding obsession with real estate. After all, this Mod hypnagogia has to fill the eye somewhere. Why not bang in the middle of a castle? Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher features a wealthy aristocrat burying his twin sister alive, thereby entombing his own femininity.

Evelyn represents both Usher’s primary theme of the divided self and the obdurate refusal to learn from it. “Alan,” who emerges a moral hero in the end (after his shrink aids and abets his murder spree), remains just as ornery, alienated, and vainglorious as Giallo itself. We’re never told precisely what the film’s fetish objects are supposed to mean. And since the camera seizes upon each one with existential grimness, we’re left with a visual style that begs its own questions.

Function follows form into the abyss. One Ophelia after another dies to satisfy our cruel delectation, even as will-o’-the-wisp light, taken from the bogs and neglected cemeteries of Gothic Horror, finds itself transformed into a crimson-dripping stiletto. Evelyn stands in for all Gialli, a genre which redefines film itself on the narrow front of visual impact: stainless steel cutlery and candy-colored light enact a sentient agenda as color becomes an instrument of hyperbolic misogyny that fills the eye and then some.