#I did this to practice with my new toy/image editor

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Stitch from the elevator scene in episode 48 of G Gundam

The camera did not pan far enough to completely include Bolt Gundam, sadly.

#G Gundam#Shuffle Alliance#I did this to practice with my new toy/image editor#It uh. did NOT save me time because I figured out how to keep the full height of the frames#despite the pan not being perfectly horizontal#it's a pain in the ass to have to remember to switch back and forth between the move and select tools now that I have a real ass program#but that's the price of not wielding a piece of shit I guess#there might still be some seam fuckery because I had to figure out which brushes were which too.#poor Argo keeps getting the shaft XD#he's cropped half out of this shot#Everyone gets a theme song! Argo and Sai have to share though.#gotta share that final fight with Domon with Allenby as well too champ#and he is *never* the one Shuffle member that gets into any of the video games#(If SunBandai just axed ONE of the two sets of designs that the WHOLE ASS WING TEAM GETS we could have all the shuffles fuck you wing)#my edits

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

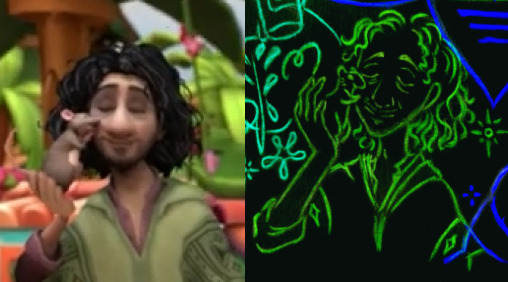

Happy second anniversary of Encanto movie!

I had (then and year ago) more ambitious idea of mock poster, but again, to execute it properly, decided to put it aside until skills and tools for it gained. So I opted for the piece reflecting on my personal take from the story.

The drawing is an experiment, drawn traditionally in complementary colors and put through color inversion in an editor.

I’m not a fandom person, admittedly. What piques my interest in exploring of piece of fiction is, usually, is its origins, history of creation, cultural background and, in some cases, impact it leaves on the art coming after it, rarely anything beyond. With all things I’ve had getting into recently, it was like that, generally observatory things. When I’ve got into MLP, it was a phenomenon of its large fandom, sheer variety of art forms it produced (from the music and games to automata toys), people of different upbringing and cultures being all inspired by it – fascinating to witness such a movement in present time. With The Simpsons, it was its legacy, its large influence in modern media – seeing the roots, the blueprint of it, getting understanding of why it was such a powerful piece of storytelling and visual direction to raise the cult around it. With Encanto, it got me curious at first to see aesthetic of magical realism being translated in form of animation, and I was surprised Disney decided to dip their toes into attempt of it. Generally, I’m more enticed by potential of the story and its artistic presentation, most of it is left in concept studies rather than in finished work, as often in mainstream production, possibilities and imagination and artistic talent poured into it is much more stunning than the product released to the public. I may feel reasonably cynical about modern Disney as company, but I can’t deny the imagination and immense genius of professionals who are still at work in it. I wish we’ll see the true Renaissance of what always was its major power - traditional animation.

So, what’s the outcome of it: while any piece of fiction that wins my full attention does make my creative juices flowing, nothing of it got to see the light of day until I felt the urge to express what was brewing in my mind affected by that new and hot thing, not to a lesser extent getting inspired by other people’s concurrent creative works, it did kick off renewal of drawing practice I had abandoned years ago and continued postponing for indefinite period. It still induces me to work toward my own progress, for it provides me with backlog of ideas to make into drawings when I really need motivation. It’s going to keeping up, hopefully, until some other thing sweeps me away or something makes my enthusiasm fade. And so, the movie in question is what had the most productive impact on me so far, it helps me keep going, and I’m grateful for that.

On the different note, Bruno in this image is based on Disney Magic Kingdoms's Encanto event video:

#encanto#encanto fanart#disney fanart#bruno madrigal#julieta madrigal#agustín madrigal#isabela madrigal#luisa madrigal#mirabel madrigal#la familia madrigal#madrigal family#phantieart

157 notes

·

View notes

Text

❝𝕀𝕟 𝕋𝕙𝕖 𝕊𝕠𝕠𝕡❞

𝚗𝚘𝚝𝚎𝚜:

⇢ Episodes 3-4

𝚛𝚎𝚖𝚒𝚗𝚍𝚎𝚛𝚜:

⇢ conversations written in italics are spoken in english. requests and feedback are highly appreciated!

⇢ script form (name: lines) are the interviews

EPISODE 3

she was shown tucked under her purple blanket still sleeping while the others were starting to wake up

while jin makes his way to the upper house’s kitchen, she slowly gets up and checks her phone

“11? already?”

the next cut you see is of her in lounge shorts and a big shirt instead of her pajama set waddling her way to yoongi and attaching herself to his side

“oppas,” she wrapped her arms around his waist, tucking herself under his arm, “how do you guys have so much energy right now”

“aigoo, our makdungie just woke up,” seokjin cooed while hoseok just squished her cheeks in an attempt to help her regain her senses

“wake yourself up, princess, then come help me with ingredients” “okay”

she helps yoongi with the vegetables, him making sure to take the onions away from her

she was giggling with hoseok at yoongi’s face when he was cutting up onions

hoseok had her in a back hug with his chin on her head while yoongi stirred the ingredients together. her job, despite being the best cook in bangtan, was adding the cheese

miya: i’m actually pretty good with meals, but if i don’t cook alone, the oppas usually make me do the minimum. something about it being dangerous?

the older members passed her off to jungkook as soon as he got there

aaaaand the two maknaes disappeared

a clip of them talking while walking towards everyone else played. their conversation was hushed, though, and the background music just played over it. the subtitles read “maknaes are quiet in the morning”

she headed over to the grass in front of the main house where she started doing stretches. she did basic stretches then went on to a few more advanced ones

namjoon saw her from a distance

“yoon-ah, are you okay over there?” “i’m okay!”

after her stretches she just ended up lying on the grass and scrolling through her phone

eventually she just plays music and puts her phone in a safe spot then entered the trampoline

she shook her head amusedly when she saw jungkook, taehyung, and hoseok jogging past her

she starts hopping around the trampoline to build up momentum and, next thing you know, she’s practicing different gymnastics tricks

you don’t see her for a while

she’s next shown in the main house sitting next to yoongi, excitedly bouncing in place while opening a box

“i can make makeup! oppa, look!”

the editors replayed the clip, emphasizing on how all four boys in the room turned to her

she excitedly took stuff out and started setting up while animatedly telling the boys about everything she could grab a hold of

yoongi was just nodding and humming in response every now and then while the other three did the same but while doing their own activities

until she eventually became way too focused to talk

around the time jungkook and taehyung are boxing each other, she turned to jimin

“oppa, sit still!”

and she places something on his lips with a grin. it was lip gloss with pink glitters

“ooooh it looks nice” jimin poked at his lips while checking his face in his phone

“i should sell these,” she laughed and closed the containers

then she heads off somewhere with the box holding all the cosmetics

the next clip of her is when it’s raining. she’s sitting on the roofed area of the deck on the boathouse with her guitar and a notebook. she’s just mindlessly playing the guitar while watching the rain

miya: there was something calming about watching the rain hit the water… i guess i just don’t see it too often nowadays. not much in the past few years, actually

she’s next seen when yoongi stops by to bring her with him over to come with him to get his recording equipment

“we’re making a theme song?” “looks like it.”

she just laughs and follows him after setting her guitar and notebook down in her room

she’s in giggles when namjoon’s recording “in the soop” and hoseok’s kinda just coddling her and laughing with her

she’s lying down on the floor while jungkook was building toys. hoseok comes in and tosses them both a pair of sweatpants and calls them for food. she could smell the food when she opened the door.

“pajeoooooooooon!”

she comes running to the tarp and shouting excitedly. the older members laugh fondly

you can see her and jungkook cheers makgeolli a few times on the side

she smiles at taehyung when they’re telling him he can flip the pajeon next “oppa fighting!”

the steam from the soup goes towards her face and she scrunches up her nose “it’s so humid wait”

she applauds when taehyung successfully flipped the pajeon and when jungkook did the same

“can i cook beef tomorrow?” and yoongi just looks at her “you and me in the kitchen tomorrow” and she just sits back with a satisfied smile

they’re all singing and she’s giggling on the side “you guys sound like drunk ahjussis”

somehow she’s curled up on hoseok’s lap all giggly and he looks at her “our makdungie is tipsy from the looks of it”

EPISODE 4

at the start of the episode you can see her curled up in yoongi’s side and playing a game on her phone

“how much makgeolli did hobi sneak you to make you tipsy?” “honestly, oppa, i don’t know”

the next you see her, she and jungkook are in his room, a bottle of soju between them, and just talking

“you know, i didn’t expect that we’d be this close at first”

yoonmi laughed at his statement “neither did i. you came and were kinda scary”

“it was completely new to me having a girl around,” he defended himself while pouring them another shot each, “but i found my best friend that way”

they clinked their shot glasses together and downed their current shots

“it’s a little funny, isn’t it?” she asked him

“what is?” “the fact that we became best friends. most guys your age at the time would have found it weird hanging out with a little girl”

he scoffed “i’m different! besides, i think it’s because the hyungs said it takes a while to get close to you, and i wanted to be the fastest”

she poured them their next shots “your competitive streak never died down”

they took their shots and sat in silence for a little bit just letting their music play from jungkook’s phone

the captions read “the two maknaes are communicating through the silence” while they just sat there and drank their soju

“hey, have i ever thanked you?” she asked all of a sudden

he raised an eyebrow at her, “for what?”

“everything,” she laughed, “taking care of me, being on my side, being someone i can talk to”

“many times, yeah,” he chuckled “you do the same thing for me, anyway. that’s why we’re best friends, remember?”

“then why do you always toss me around like a doll” “you look like a doll, face it”

she laughed while pouring them the last of the soju

“cheers to best friends and being bangtan’s maknaes,” she held her shot glass up “sleepover today?”

he laughed and clinked their glasses again “sleepover any time”

miya: ggukoo oppa, we’ve been friends since we were kids. we grew up together, so i guess we understand each other a lot? sometimes we have deep talks, sometimes we sit in silence. sometimes we fight, and sometimes we team up against the other oppas.

jungkook: i think people don’t understand that mimi and i have a deeper kind of dynamic rather than just the childish image we usually have together on screen. us talking like this is something we do a lot, and it brings us both a lot of comfort. clarity, too

then there’s a mini montage of them talking, but their words are muted and music played over them. there are bits of them laughing, drinking, and maybe letting out a tear or two before they just got into jungkook’s bed to go to sleep

when taehyung goes to the boathouse to sail his rc boat, he checks on them. the editors put a clip of jungkook and yoonmi sleeping with the caption “maknae siblings are tired from talking until 4am”

a while passes, and there’s a clip of jungkook sitting up in bed, yawning and rubbing the back of his head. he looks around the room a little before shaking yoonmi awake

“hmm?” “come with me to the main house” “okay”

the scene cuts and you next see them in the main house, jungkook working on his glider with yoonmi lying down next to him, her head on his lap and still half-asleep while namjoon and jungkook talk

“sleep late, yoon-ah?” “ggukoo oppa and i stayed up until four i think”

her mumbling was slightly incoherent, though and namjoon just laughed and patted her head

when he gives up on the glider, his hand rests on yoonmi’s head, lightly massaging for a bit before transferring her head to namjoon’s lap and heading to cook

“joonie oppa?” “hmm?” “are you reading?” “yeah, why?” “could you read out loud?”

namjoon’s just reading stuff out loud while she’s listening intently to every word

namjoon and taehyung headed up to the upper house first while she sat by the kitchen and waited for jungkook to finish what he was cooking

she opened her mouth as he turned around, just in time for him to pop a piece into her mouth “let’s go”

she settled into taehyung’s side and slowly began to eat after thanking the older members for the food. yoongi chuckled at her sleepy demeanor

“you’re taking a while to wake up today, princess” “ggukoo oppa and i had soju before sleeping”

“i like the melon,” she noted, making taehyung grin at her and nuzzle his forehead against the top of her head

she took over drying the dishes for namjoon and kissed him on the cheek “stay safe on the way back, oppa” “you, too”

she ended up cleaning up with jimin, humming a little song. she was telling him about the dream she had where they all performed live again. once they finished, she went off to sit with hoseok and read while he customized his shoes

“oppa, if it turns out good, you’re going to have to make one for me, too!” “ooooh matching shoes? you’ve got it”

jimin came and started customizing his shoes as well after briefly petting her hair

she went inside so jimin could use her chair and sat next to taehyung who pulled her into his lap. he rested his chin on her shoulder while she read

when it came to packing up, she was muttering to herself while folding things into her carrier “should i have done more? i feel like i was too boring… oh well”

jimin walked into her room and leaned against the door frame

“need help, aegi?” “... yes, please” he helped her carry the bag with her clothes and the bag with her recording and producing equipment while she carried her guitar out

she ended up playing a vr game with jungkook where they had to break boxes to the rhythm of songs

there was a lot of giggling and laughter while they tried to distract each other with jimin on her side and taehyung on jungkook’s side

“ggukoo oppa’s cheating!” “uh huh, get your revenge later, let’s eat first”

she pouted at seokjin’s words but took of the vr goggles and skipped outside

“thank you for the food!” and she digs into her jjapaguri

she laughed at the reactions part until hoseok turned to her “why are you laughing? you can’t hide it the most!”

“only to you guys! but to everyone else, i can fake it”

she put her bags and guitar into the car yoongi drove and was surprised when yoongi told her to her to get in shotgun. she did and saw seokjin walking towards them and the car in front driving off

“pretend you’re asleep, princess”

she quickly closed her eyes and faced yoongi, struggling to hold in her laughter when she hear seokjin trying to open the door

she just lost it when yoongi drove off

80 notes

·

View notes

Note

jess what about the sex toy fic

From the “Send me an ask with the title of one of my WIPs and I’ll post a snippet or tell you something about it” meme thing.

Mar.... I’m so glad you asked. XD So the sex toy fic is about Ginny trying out different sex toys so she can write reviews of them for other people to try out. Originally it was going to be a Draco/Ginny fic, because that’s my default, with Draco owning or working at a sex shop. But I stopped writing the fic because I just couldn’t make it make sense. So in putting this post together, I realized it’s not a Draco/Ginny fic at all.... It has to be a Pansy/Ginny fic!!! I got way inspired, but smut is really hard to write so I don’t know if this will go anywhere still. BUT I made some notes in my phone so that if I do decide to come back to this, I’ll know where to go. :)

Also, I’m really sorry, y’all, but my funniest work is all in WIPs that no one will get the chance to read.

Here’s a potentially NSFW snippet??

~*~

Ginny startled when a copy of the Daily Prophet flopped down on top of her desk, smearing the ink of the article she’d been struggling to write all morning. An outraged remark died on her tongue as she looked up to find Lavender Brown standing on the other side of the desk, her expression a mixture of anxiety and anger. Tears sparkled in her eyes, threatening to fall and ruin what was left of Ginny’s writing.

“Look at this!” Lavender said, her voice pitched high enough to burst eardrums.

Ginny peered down at the paper, scanning the headlines and column titles facing her for the trigger of Lavender’s distress. Nothing seemed amiss. Dominating the page were a continuation of an article from page A2 about a garden gnome that had saved a woman’s life, a letter to the editor concerning the Prophet’s lack of Oxford commas, and the relationship advice column, Dear Madam Lovegood.

“What is it?” Ginny asked, stupefied and growing more impatient by the second. She had been on the verge of a breakthrough with her article—she just knew it!—until Lavender’s interruption had scattered her thoughts.

Lavender bent over the desk and jabbed her finger at the advertisement in the middle of the page. “This, Ginny! Look at this wretched thing!”

The ad featured a photo of a desktop fan. Every few seconds, the image would pause, revealing exposed blades that lay flat and faced upward instead of laying vertically and facing outward. The design was strange and it didn’t look very practical.

Before Ginny could ask what was wrong with the ad, words in a swirly font emerged amidst a cloud of sparkles over the photo of the fan.

The Fanny Flicker

For the unhitched witch with an itch!

Ginny’s cheeks heated as she realized the advertisement did not depict a fan at all but a toy intended to simulate oral sex.

“There, you see!” Lavender’s voice strained with emotion. “Do you see my dilemma now?”

“Er….”

“That advertisement is ruining my column! How dare Barnabas approve for this monstrosity to be featured in the very middle of Madam Lovegood’s sage, wholesome advice!”

Ginny would have laughed at Lavender’s theatrics if her deadline hadn’t loomed quite so closely. Instead, irritation prickled just under her skin. While moving the newspaper to check how badly her article had smeared, she asked, “Didn’t you tell someone to castrate her boyfriend just last week?”

“Nooooo, if you read my column at all, you’d know I told Cheated And Defeated that had I been in his shoes, I would have castrated my boyfriend.”

“I hope Ron didn’t read your column either, then,” Ginny muttered under her breath as she siphoned up some spilled ink with her wand.

Lavender had once sent a letter in to Ask Adaline, the defunct relationship advice column that Lavender’s column had replaced. Adaline’s response to her letter had been generic and pale, much to Lavender’s dissatisfaction. After doing the complete opposite of what Adaline had advised in order to win Ron’s affection back, she had sent another letter in to the column, this time critiquing the advice given to other submitters in the previous week’s issue of the Prophet. Lavender’s weekly rebuttals had grown so popular, the Daily Prophet’s editor, Barnabas Cuffe, had had no choice but to let Adaline go and hire Lavender on to run the column instead. She’d taken up the name Madam Lovegood as her pseudonym, purposely overlooking the fact that the name belonged to a former classmate and her magazine-owning father (“What do I care if it’s Luna Lovegood’s name! That name is perfect for an advice column about love and relationships! What name should I use instead, Ginny? Madam Lovebad? I don’t think so.”).

The new column had been a big hit, mostly due to Madam Lovegood’s wild and colorful opinions. As silly as the whole column was, Lavender took her work very seriously.

Maybe a little too seriously.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Au delá des étoiles translation practice!

a practice translation from french to english and portuguese!

i reaalllyyy loved the songs from Belle specially the french versions! Louane sings so well and the lyrics are so simple and powerful! and since i talked about translations in my last post it gave me an immense desire to make a translation of some songs to learn more french or just to have fun and post here!

as a disclosure, i'm still a begginer in french! so if you have any corrections or suggestions pls share! this is just for practice and learning new words! (specially that there were 2 lines i had no clue how to translate!)

ps: i know there r formatting mistakes but im tired of fighting against the editor for a post thats way too big for it to handle from the start, he's innocent and did it's best

Titre

Au delá¹ des etoiles

To beyond the stars

Á além das estrelas

¹ i'm going to be honest, this "delá" was new to me so i had to do some researching but that too was hard, all i found was "de la". so i resorted to deepL, so if you have any more info about this please tell me, i'd love to learn more about this

Paroles

Lalalaï, lalalaï

Au delà des étoiles

To beyond the stars

Á além das estrelas

Quand nos coeurs se dévoilent

When our hearts are revealed

Quando nossos corações são revelados

Et battent à l'unisson

And beat in unison

E batem em sincronia²

je t'enmène la oú tu n'est jamais allé

I take you where you've never been before

Eu te levo aonde jamais foi

Lalalaï lalalaï

J’irai chercher ton âme

I will search for your soul

Procurarei por sua alma

Au delà de la lune

To beyond the moon

Á além da lua

Si tu l’as abandonnée

If you have abandoned it

Se você a abandonou Ne détournes pas, dis-moi ton nom

Don't turn away, tell me your name

Não vire de costas, me diga seu nome Lalalaï, lalalaï Lalalaï, lalalaï

Tu voudrais fuir le monde

You want to run away from the world Você gostaria de fugir do mundo

Effacer chaque seconde

Erase every second Apagar cada segundo

T'échapper de la ronde³

Escape from the crowd Escapar da multidão

Où plus personne ne te vois

To where no one can see you

Aonde ninguém pode te ver

fermer les yeux, remonte les images, change les mots

Close your eyes, recreate the images, change the words Feche seus olhos, recrie as imagems, troque as palavras

et tourne la page

And turn the page E vire a página

tout au fond de ton cœur tu peux trouver le passage

From the bottom of your heart you can find the passage

Do fundo do seu coração você pode encontrar a passagem

C'est comme un jeu,

It's like a game É como um jogo

entre dans la danse

Participate in the dance Entre na dança

saute dans le feu avec moi

Jump in the fire with me Pule no fogo comigo

Où tu le veux, si tu deviens toi (??) ^4

Wherever you want, if you become yourself Onde você quiser, se você ser você mesmo

Allez debout rejoins la danse

Get up and join the dance Levante-se e se junte a dança

c'est ici passe de l'autre coté

It's here that we cross to the other side

É aqui que se cruza ao outro lado

la magie et la chance vont pouvoir opérer

The magic and luck will be able to work A mágica e a sorte vão ser capazes de operar

Lalalaï, lalalaï

jour et nuit je m'égare dans la galaxie

Day and night i go astray in the galaxy

Dia e noite eu me perco na galáxia

où est la clé d'un amour infini

Where's the key to an eternal love Onde esta a chave de um amor infinito?

Lalalaï, lalalaï je vais suivre les ombres

I'm going to follow the shadows Vou seguir as sombras

dans une autre vie

To another life

Para uma outra vida

où s'emmêle nos vie

Where our lives get tangled up

Onde nossas vidas se embaraçam

ne perd pas de temps

Don't waste any time Não perca tempo

c'est maintenant ou jamais

It's now or never É agora ou nunca

c'est le début du voyage

It's the start of the journey

É o começo da jornada

c'était écris dans les nuages

It was written on the clouds

Estava escrito nas nuvens

sens tu la force nouvelle

Feel your new strength

Sinta sua nova força

d'un nouveau monde qui nous appelle

Of a new world that calls us

De um novo mundo que nos chama

dans cet univers ou tout est né

In this universe where everything is born Neste universo em que tudo nasce

je t'en supplie reste a mes coté

I beg you to stay by my side Eu te suplico para ficar ao meu lado

on sauveras tout le monde

We'll save everyone Nós salvaramos todo mundo

oh ne me quitte pas

Oh don't give up on me

Oh não desista de mim

C'est comme un jeu,

It's like a game,

É como um jogo,

entre dans la danse

Participate in the dance Entre na dança

saute dans le feu avec moi

Jump in the fire witrh me Pule no fogo comigo

rejoins la fête sois fière

Join the party, be proud of yourself Junte-se a festa, tenha orgulho de si mesmo

et dans le cercle regarde comme on danse

And inside the circle watch how we dance E dentro do cìrculo assista como dançamos

ca commence a tourner la tête

Your head starts spinning Sua cabeça começa a girar

tout tourne autour de toi

Everything spins around you Tudo gira em torno de você

avec moi où tu le veux si tu deviens toi ^5

With me we can go wherever you want, if you become yourself Comigo iremos aonde você quiser, se você ser você mesmo

Allez debout rejoins la danse

Get up and join the dance Levante-se e se junte a dança

Danse ton futur

Dance away your future Dance o seu futuro

Oublie les voix du passé

Forget the voices of the past

Esqueça as vozes do passado

Nous avons l'aventure

We have the adventure Temos a aventura

Un nouveau monde à inventer

A new world to invent Um mundo novo para inventar

Verse 1 repetition Verse 2 repetition

je crois que c'est le moment c'est maintenant ou jamais

I believe that's now or never Eu acredito que é agora ou nunca --------------------------------------------------------------------------- ² i know theres the word "uníssono" in portuguese, but i personally don't see it ever used compared to english where ive seen unison being used a few times, i decided to use another word that meant the same but wasn't too alien to the point of being distracting. ³ i used routine cause from what i searched "ronde" means something circular or a type of dance where people make a circle, so i interpreted it as being the crowd, taking the meaning of the dance where there's a bunch of people around you and you get uncomfortable like being in a crowd, but it could also be repetitiveness/routine cause circles also relate to that, but considering the next line, unlikely.

4 this phrase makes no sense to me, i tried the most literal translation i could but still makes me so confused 5 still got no clue how to translate this and this time got even worse

#gosh this was a long LONG song#but it didnt repeat itself in long chunks for me to just be lazy enough#langbr#french#french langblr#french learning#portuguese#langbr portuguese#this was an editing hell#a formatting hell even#langblr

0 notes

Text

OK, I'LL TELL YOU YOU ABOUT CHANGE

The path it has discovered is the most popular online store builder, with about 14,000 users. Indeed, almost pathologically so. There is a parallel here with the first microcomputers. Com, which their friends at Parse took. If Microsoft and AOL get into a client war, the only way to deliver software, but for Web-based applications can be used for constructive purposes too: just as you can trick yourself into looking like a freak, you can write a spreadsheet that several people can use simultaneously from different locations without special client software, or that can page you when certain conditions are triggered. And not only did everyone get the same thing the river does: backtrack. They don't have time to work.

They felt a two-party system ensured sufficient competition in politics. With the rise of new kind of company. But in retrospect you're probably better off studying something moderately interesting with someone who isn't. An essay you publish ought to tell the reader something he didn't already know. And increasing economic inequality means the spread between rich and poor is growing too. Web-based applications, these two kinds of stress get combined. At $300 a month, we couldn't afford to tell them. At the time IBM completely dominated the computer industry. The test drive was the way we work: a normal job may be as bad for us, like a dangerous toy would be for a toy maker, or a car in the street playing thump-thump music. The form of fragmentation people worry most about lately is economic inequality, and if you do something to the software that users hate, you'll know right away.

The effect was rather as if we were visited by beings from another solar system. If users can get through a test drive successfully, they'll like the product. I've discovered a handy test for figuring out what you're addicted to. And since the customer is always right, but different customers are right about different things; the least sophisticated users show you what you need to sell it to them. But not the specific conclusions I want to examine its internal structure. It happened to one industry after another. Up till a few years do seem better than the ones straight out of college, but only one step. You needed to take care of you. Originally the editor put button bars across the page, for example. For me, interesting means surprise.

That is a fundamental change. Back button. I'd much rather read an essay that went off in an unexpected but interesting direction than one that plodded dutifully along a prescribed course. Their search also turned up parse. Also, you've never been to this house before, so you must. Today a lot of them wrote software for them. On the surface it feels like the kind of people who are good at writing software tend to be running Linux or FreeBSD now.

Plus there aren't the same forces driving startups to spread. Patch releases. Among other things, they had no way around the statelessness of CGI scripts. When Rockefeller said individualism was gone, he was often in doubt. Whether or not computers were a precondition, they have certainly accelerated it. When finally completed twelve years later, the book would be a 900-page pastiche of existing popular novels—roughly Gone with the Wind plus Roots. But we could tell the founders were earnest, energetic, independent-minded people. He has assistants do the work for him. There's nothing intrinsically great about your current name. The eminent feel like everyone wants to take a bite out of them, and after that you don't have to be. And the second reason is that if you want to pay attention not just to things that seem wrong in a humorous way.

Magazines published few of them, and they're worried about some nit like not having proper business cards. By the time we were bought by Yahoo, I suddenly found myself working for a big company. With the centripetal forces of total war and 20th century oligopoly mostly gone, what will you miss about being young and obscure? Industrialization didn't spread much beyond those regions for a while. They might even be better off if they paid half a million dollars for a custom-made online store on their own servers so they can focus on growth, many of the big national corporations were willing to pay a premium for labor. Indeed, helps is far too weak a word. Programmers and system administrators have to worry about the servers, and in practice the medium steers you. And a program that attacked the servers themselves should find them very well defended. This worked for bigger features as well. Don't be intimidated. In another conversation he told me that what he really liked was solving problems.

I also spent some time trying to eliminate fragmentation, when we'd be better off thinking about how to mitigate its consequences. You can see every click made by every user. An essayist needs the resistance of the medium. In his autobiography, Robert MacNeil talks of seeing gruesome images that had just come in from Vietnam and thinking, we can't show these to families while they're having dinner. I was about as observant as a lump of rock. And so in the late 19th century continued for most of what happened in finance too. This doesn't always work. I suspect the best we'll be able to coordinate their efforts, and you want to work in groups of several hundred. And if you manage to write something balanced. Certainly schools should teach students how to write. When a company loses their data for them, they'll get a lot madder. You can also be in closer touch with your code.

When I grew up there were only 2 or 3 of most things, and since there was nothing we could do to decrease the size of group that can work together, the only thing sure to work on. And the models of how to look and act varied little between companies. And then there was the mystery of why the perennial favorite Pralines 'n' Cream was so appealing. And in retrospect, it was a team of eight to ten people wearing jeans to the office and typing into vt100s. In life, as in books, action is underrated. Web-based software will be good this time around, because startups will write it. I spend most of my time writing essays lately. To some extent, yes. By the time we could find at least one good name in a 20 minute office hour slot.

#automatically generated text#Markov chains#Paul Graham#Python#Patrick Mooney#century#thing#vt100s#conversation#Robert#nit#kind#drive#store#conclusions#time#retrospect#toy#computers#servers#test#dollars#administrators#Microsoft#corporations#hour#madder#features

0 notes

Text

Mother Said, Nobody Becomes An Artist Unless They Have To

By Claire Rudy Foster

My mother said she’d kill me if I wrote about her. She laughed, because it was a joke, because of course she’d never actually kill me. She’d just make me wish I was dead.

As an adult, I have written about many kinds of mothers; I have become a mother, myself. But I have left the place in my heart where my real mother lives wild, unexplored, and dark.

I believe that she wants it that way.

My mother, for better or worse, finds her way into my stories. I’ll start a new story and there she is, looking at me over her glasses. She’s a great reader, my mother, perceptive and sharp. She misses Michiko Kakutani’s column in the New York Times and hasn’t bonded to the new book review editor yet. My mother is a critic, like me: she’s impossible to impress.

She doesn’t read my writing. It upsets her too much.

Yet, when I write, she is often the reader I’m envisioning. I practiced my first stories on her, after all. I keep offering her things when I know she won’t take them. I can only make one thing, sentences, and I bring them to her like dead birds, watch her step over them, watch her carefully bury them in the rubbish heap.

I revisited the unidirectional relationship between mother and child when I picked up a battered copy of White Oleander from a free library box this summer. I read the novel in 1999, right before it got selected for Oprah’s Book Club and became a #1 national bestseller. It represented everything that I wanted: everything I wanted to experience, everything I wanted to be as a writer and a person. Janet Fitch and I were alumni of the same college: she graduated in the same class as my father, when he went there. Her prose was fiery, floral, packed with images that dripped like LSD trails. Astrid, the main character in White Oleander was the same age I was when I first picked it up, and as I read it, I felt myself maturing, hardening.

At night, I prayed for a life worth writing about. I didn’t know what I was asking for.

Yes, I got what I wanted.

What I didn’t get was a mother like Ingrid Magnussen: the white haired Viking poet whose bond to Astrid prevails through a decade-long separation. Serving a life sentence for poisoning a lover who jilts her, Ingrid sends Astrid letters from prison. Her sections of the novel, I remember, felt flat to me, and when I first read White Oleander I admit that I skimmed those scenes, flipping through Astrid’s visits to the prison and the strange notes she received from her mother at her many addresses. I didn’t realize it at the time, but those letters were missives from my future.

She writes, “Remember, there’s only one virtue, Astrid. The Romans were right. One can bear anything. The pain we cannot bear will kill us outright.”

When I revisited this novel, I realized that Ingrid was the mother I wanted, back then. She was also the mother I had become.

My teens and twenties were the kind of miserable that breeds artists or suicides. I overdosed on heroin at 18, lost my virginity to a rapist in a Mediterranean hotel, saw a few gunfights, learned how to take a punch. I survived myself, as Astrid did, and those experiences became a patchwork of scar tissue that covered my heart. Like Astrid, my pain protected me from the way the world continued to batter me, the way the first slap will numb your whole face, overstimulate your nerves, so that the next one and the next one feel like nothing, not even when his ring catches your lip, it’s nothing, just impact, and you’re used to that, you know the feeling, you’re tired of it before it even gets going.

When I was 19 years old, I came home from college and went to a party, where someone put a roofie in my drink. Drinks. I remember standing near the bonfire on the beach, surrounded by people I used to know, and then the next thing the whumph of my body hitting the sand, rough hands hauling me up, touching under my arms, my breasts. I remember trying to find my feet as they pulled me down an alley; who did this to me? I stumbled, and then everything was grey, and then everything was black.

I came to with my friend Scott on top of me. It was dark, early morning.

“Scott, are you fucking me?” I said.

He didn’t answer. He hauled me on top of him and continued, although I pushed him back and turned my face away from his kisses. He put his mouth on my breasts. He smelled like leather that has been soaked in speed and salt, dried in the sun. I knew he was injecting---I tried to think about HIV transmission, Hep C, how the barriers of my body had been breached without my knowledge. I could be dying, right now. This could be the thing that killed me.

My voice shrank in my throat. This is my friend, Scott, I said to myself. What had I done to deserve this?

When he was finished, he said, “Be grateful I didn’t cum.”

He hadn’t used a rubber. My physical self woke up one limb at a time. There was the nightmare feeling of panic, and being trapped in a body that is not responsive and can’t run when you need to get away. I eased myself out of bed, onto the floor. It took a few minutes to stand up, and although I was ashamed and wished I could wrap myself in the sheet at least so that he could not see my nakedness, I felt a terrible, tearing heat between my legs and it was more important to get away so I did, and there was some blood on the toilet paper and on my lip where it had split, how did that happen, what did I do? What was done to me?

I put my hands on the bathroom sink for balance and tried to wash my face without looking in the mirror. I didn’t want to see myself as a sick animal. Next to my right hand were the dozen hairpins I’d used when I got dressed up for the party. They were laid out in a perfect line, each one square and symmetrical to the others. Who did that? I scooped them into my palm and held them. More than anything, I wanted my mother.

Scott walked me home, as though we’d just been on a date, and when I staggered into the house my mother saw me and asked me and I told her. It was not my first rape, or my last one, but it is the only one she helped me with. She called the police, and she rode with me in the squad car to the place where they scrape cells from the inside of your body to see if they can find any incriminating DNA. My mother, who said nothing, sat by me and held my hand while the person collecting evidence from me - me, I was a crime scene - slipped a tiny speculum into my ass to swab for semen.

“Wow, yours is so easy,” the person said. “Most people, it takes more than one try.”

I was ashamed. Because my ass opened easily, maybe I was easy, maybe I was built for all kinds of violation. My mother passed me a piece of candy and I put it in my mouth, trying not to cry. We never talked about what happened. I blamed her, of course. I thought of all the things I wished she’d said or done. When I hear other people’s stories about their supportive mothers, I quivered with jealousy. My mother was not like other people’s mothers.

I didn’t understand that, in my moment of pain, she was as vulnerable and scared as I was.

Probably, she wanted her mother.

Nobody came with me to give my statement to the police. I brought a stuffed toy my mother had given me, a pudgy wad with string bean arms and legs and a Muppet nose. There was an advocate sent by some nonprofit, who sat next to me making faces of disgust when I described what I’d experienced.

“Did you say ���no’?” the detective asked. She was young and pretty, with a high curly ponytail. She looked like she was going to coach a cheerleading practice after this. She made notes on her clipboard.

“I couldn’t speak,” I said.

She put the pen down. “In the state of California, it’s not ‘no’ unless you say ‘no.’”

“It was rape,” I said. “I’ve been raped before, I know what it feels like.”

The detective shook her head and closed the book of mugshots. Scott’s was in there: I’d pointed to him, identified him, and repeated my story into the detective’s tape recorder. I said things I couldn’t say in my mother’s presence, about my drug use and the other people who were there. Exactly the positions. Exactly the feelings. Yet, I resented her for not leaving work to be with me. The detective stood up.

“Are we done?” I asked. “That’s it? You’ll arrest him?” “You didn’t say ‘no,’” she repeated, and left the room. I was numb. I sat outside the police building for a long time, crying and holding this silly, stuffed animal. The advocate stayed for a few minutes. I tried to put my head on her shoulder and she scooted away, until she was sitting a good three feet away from me on the concrete bench. Then, she also got up and left me alone. I was 19. A child. I needed my mother; where was she?

Ingrid said, “Loneliness is the human condition. Cultivate it. The way it tunnels into you allows your soul room to grow. Never expect to outgrow loneliness. If you expect to find people who will understand you, you will grow murderous with disappointment.”

I cried until the bus came, and then I went home and lay down in my bed. When the winter break ended, I went back to college. I have never talked about this, or any of my sexual assaults, with my family. I believed that their silence meant that they did not care what happened to me. I treated myself accordingly. It was not the last time I woke up with someone raping me, or the last time institutional justice failed me. Like Astrid, I was hardening, losing faith. Every time I was hurt, my armor got thicker. I drank more. I was never not ready to die.

But now, when I revisit that memory, all I can think about is how my mother silently watched me bear the pain and humiliation of that exam. It never occurred to me that she was suffering too. I didn’t think about this until I had a child of my own. Loving him introduced me to real vulnerability. I couldn’t be weak anymore: I had someone to protect. For the first time, I understood how my mother felt about me, when I was new. It was an animal feeling. I loved him so much, I could have committed terrible crimes.

The first words I said to him, into his new, perfect ears, were, “If anyone ever hurts you, I will fucking bury them.”

My son has a ferocious mother. Before he existed, I was a victim: at best, someone who would survive. Six rapes, heroin addiction, overdoses. It was the kind of life that pounds you into the ground like a wooden stake. Then, I got pregnant, and my entire outlook on life changed. I had someone to stand up for, so I had to learn to defend myself.

Imagine my discomfort at opening White Oleander again, and seeing Astrid not as a reflection of myself, but as her ferocious, unforgiving mother. I saw her monstrousness and her total disdain for human weakness, but this time, I wondered what she’d experienced that made her so hard. I was learning how to be a single mother, an easy target for unscrupulous men. I knew what it meant to walk around in a woman’s body - the price the world exacted from us from being beautiful. I wondered where Ingrid’s mother was.

Part of being a good mother is letting your child learn to bear their own trouble. I couldn’t be with my son every moment: I couldn’t stand between him and the bully at school. I had to let go of him in small ways, at the right times, and it burned me like coals. I felt like my one hand reached for him and the other restrained it.

At the same time, I went through my own processes. My son saw me messy, tired, crying, out of money, scared. He saw me asleep and awake, laughing and mourning. He witnesses my vulnerability. I think that is the fear of all mothers: that we will raise a child who sees our weaknesses and shares them with the world. We trust them to keep our shortcomings to themselves. Yet, always, they see us and they hear us and our failings make indelible marks on them.

By the time Astrid reaches adulthood, she’s covered in scars, inside and out. She’s been chewed up by the foster system. She’s had many mothers. As I finished White Oleander this time around, I wanted to hug her. Pass her a piece of candy.

“You poor thing,” I’d say. As though she hadn’t just given birth to herself. As though she hadn’t studied, her entire life, how to be a survivor.

Claire Rudy Foster's essays on addiction, queer issues, and writing are featured in The Huffington Post, The Rumpus, and Racked, among others. Twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize, her fiction can be found in McSweeney's, Thrice Fiction, and many other rad journals. She is a book reviewer and very gentle rabble-rouser. Claire lives in Portland, Oregon.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Secrets To Raising Your Money Savvy Family

Secrets To Raising Your Money Savvy Family

[Editor’s note: Today’s guest post comes from Doug Nordman. He retired from the U.S. Navy’s submarine force in 2002 at the age of 41. He and his spouse, a retired Navy Reservist, reached their financial independence on a high savings rate. Doug wrote the book “The Military Guide To Financial Independence And Retirement.” He and their daughter Carol Pittner wrote “Raising Your Money-Savvy Family For Next Generation Financial Independence” and published it with ChooseFI Media.]

Take it away Doug….

*********************************************************

Financial Independence

“How did you raise your daughter to reach her own financial independence (FI)?”

I started hearing that question from my audience over three years ago.

I speak about financial independence at conferences and meetups, both in person and online. I’m not a financial advisor, and our daughter can confirm that I’m certainly not an expert on child development or parenting.

However Carol has been hearing about FI for her entire life, and she was nine years old when I stopped working for paychecks. She’s keenly aware of the benefits of the FI lifestyle.

Today, the Internet is full of advice about paying off debt and saving for financial independence. Instead of being asked about savings rates or investing, I’ve heard from hundreds of parents who are concerned about motivating their kids to reach their own FI.

The problem is that their kids aren’t interested in saving or investing. They want to spend their money!

It turns out that kids have to learn to manage money before they’ll develop any motivation to save or invest it. They achieve this skill mostly by making mistakes with money. The bad news is that there are lots of mistakes.

The good news is that you can help them work through those mistakes with small amounts of money at home, instead of with thousands of dollars in their first 401(k)… or with tens of thousands of dollars of consumer debt.

You’re spending your hard-earned dollars to raise your kids anyway, and you can give them a tiny portion of it to manage on their own. The money wasted by a kid is a lot cheaper than letting them grow up to be financially ignorant adults.

David Owen says it best in his book “The First National Bank Of Dad”: kids think that parents are crazy about money.

Kids grow up watching their parents spend money, and they want to practice this adult skill too. Yet whenever a kid gets birthday money from Grandma, their parents try to convince them to “save it for college.” To a six-year-old, college is two lifetimes away– and who wants to save money for more school?!?

When kids encounter this ludicrous attitude, the only way they can control their money is to spend it as quickly as possible– before it’s confiscated by the parental authorities. Ha!

Money Conversation

In our family, we struggled to change that money conversation.

Two years ago, my spouse and I attended a CampFI meetup and then visited our daughter and son-in-law for a couple weeks. Over dinner (they’re excellent cooks), I mentioned that we’d had the questions (again!) about next-generation FI. We asked Carol about her money memories, and she lit up with stories.

Carol had plenty of kid memories about money. More interestingly, as a young adult she had a new perspective on those experiences and what they taught her.

By the end of dinner I was taking notes. By the end of dessert we had a book outline. A week later Carol had written most of three chapters and I was scrambling to hold up my end of the co-author deal. Six months later at another CampFI, the founders of ChooseFI asked us to sign up for their editing and publishing. You can find that book at your local public library, or ask your librarian to order it

Carol’s first clear money memory was her preschooler play with a toy cash register and its stacks of plastic coins. We found that toy at a garage sale because Carol was intensely interested in how we spent money at the grocery store. That’s probably because she wanted all the candy in the store, and our perpetual debate led to a few meltdowns.

Eventually (out of parental desperation) we negotiated an agreement for the grocery trips. We’d give her four quarters, and if she behaved then she could buy One Special Thing. (Even today we still pronounce it with capital letters.) If she didn’t behave, though, then she had to put away the money and try again on our next grocery trip.

Her behavior immediately improved, and that money talk changed our family relationship. Instead of fighting with us (exhausted) parents over spending money, she was full of questions about spending her money.

Grocery trips turned into teachable moments. We started giving Carol an allowance so that she could carry her own money to the grocery store for One Special Thing.

David Owen writes that parents have to brace themselves with a mental image of their kids waving flaming $20 bills like 4th of July sparklers.

While kids are wasting money by lighting it on fire (as if it grew on trees), they’re also learning what wasting it feels like.

It’s an opportunity for parents to guide the discussions about money feelings and choices and what the kid could do differently with the next flammable $20 bill.

We can help our kids understand those money feelings by sharing their joy at everything they could buy, and discussing their choices with an abundance mindset, and helping them with the transactions. We can also share their sad feelings when they’ve learned that the candy or toy didn’t live up to their expectations. How did they make that choice? What else could they try next time?

No lectures, and no judging. Parents can help their kids develop their internal money dialogue by talking them through the issues and brainstorming new ways to recover from the inevitable financial disappointments.

Our money conversations with Carol spread from the grocery store to garage sales and thrift stores. Instead of pushing for saving, though, we talked about what things cost and what she could buy. Carol got an allowance “for being a good member of the family”, although we parents really gave her the allowance for her chances to make choices.

In her mind, she had enough money to afford anything. As parents, we kept her allowance small enough that she couldn’t afford everything and had to make good choices. She had enough for One Special Thing but she had to save for the awesome stuff, and that led to more discussions about deferred gratification.

Putting Kids To Work

American consumerism runs rampant, and in our family it led to many teachable moments. Carol developed proficiency at her spending choices, and she was ready to learn to manage more money.

As she grew older, we parents finally had the opportunity to sneak in a few financial incentives to earn and save. How do you get more money for the awesome stuff? Why, you work for it.

There’s plenty of jobs to help with around the house, and we parents were always happy to pay a few dollars for good effort under our training and supervision. Before Carol could earn money at jobs, though, she had to finish her homework and do her chores. Neglecting chores meant losing privileges (because you’re not helping the family), but– even worse– it meant you couldn’t earn money at jobs.

The positive incentive of job money turned out to be much more powerful than the negative consequences of avoiding your chores.

Compound Interest

When Carol learned elementary-school math, we taught the miracle of compound interest. Kids struggle with percentages, but they understand “free money” very well.

Carol’s money was hers to spend or save however she wanted, but if she deposited her money with the Bank Of Carol then every dollar earned a penny of interest per month.

She could withdraw her money from the bank any time she wanted it, but the catch was that it only paid out at the end of the month.

She tested the bank’s policies and financial strength many times. Eventually she decided that she had outstanding customer service and she trusted our custody of her cash. We followed up with glowing monthly reports on her earnings and many more happy discussions about what she could do with her growing wealth.

Raising Your Money Savvy Family

By then a lot of it was wasted on toys. Wow, there were a lot of teachable moments from those years.

Behind the toy frenzy, though, we parents were establishing new financial incentives.

Every time Carol found a coupon for (healthy) food that we bought at the grocery store, she got half the savings. (Or she could find coupons to use for her One Special Thing.) If she packed a (healthy) lunch from home, then she could keep half of the money that we saved from school lunches. If she rode her bicycle to school then she kept half of the bus money. (But if she dawdled on school mornings and missed the bus, then she had to pay us to drive her to school.)

She could help us with menial jobs for the minimum wage– but if she agreed to let us train her to do those jobs on her own then she earned a higher wage.

For her ninth birthday, Carol got a real checking account from her local credit union. (She even got an ATM card– although today we’d use a debit card.) Balancing that checkbook led to many tears until we showed her how to track her spending in Quicken. The Bank Of Carol moved to online transfers and Quicken reports, too. By age 13 she was an authorized user on one of my credit cards (I never used it), and that was a powerful lesson on corporate financial marketing tactics.

We parents made our share of mistakes. In 2006 (the year before the iPhone) we didn’t see the point of “letting” her buy a cell phone, but later that year she turned 14 years old. She got her state work permit and a part-time job, and she bought her own darn cell phone with her own darn money. As we now know, that made it much easier for her to stay in the loop on her school group projects and study sessions.

Our parental financial incentives continue through her teen years and even college. If she was a good steward of the college fund, then after graduation there was profit-sharing. Her campus was full of entrepreneurs, and she learned from them.

Today Carol’s launched from the nest and she’s achieved orbital parameters. She and her spouse are on the cusp of their own financial independence. (They have a high savings rate!) Better yet, all of her money-savvy family skills are paying off for a very personal reason: they’re raising our baby granddaughter.

We can’t wait to see how they raise their money-savvy family for next-generation financial independence!

Want To Learn More?

[You can read more about the book at childFIRE.com. You can reach Carol through [email protected], and Doug at [email protected].

The post Secrets To Raising Your Money Savvy Family appeared first on Debt Free Dr..

from Debt Free Dr. https://ift.tt/2EWl0WQ via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

February Alban Lake Spotlight

Mike Morgan, Author

For our very first interview, we have Mr. Mike Morgan, a prolific and excellent author. He was kind enough to take time to answer our questions; but first, a quick bio for Mike:

Mike Morgan lives in Iowa with his wife, two children, and increasingly infirm cat. After careers in the UK, Japan, and Texas involving accountancy, freelance illustration, non-fiction writing, and teaching, Mike now does improbably complex things on computers for a living. When he's not worrying about the cat or tidying up his kids' toys, Mike gets overwrought about politics and attempts to write short stories. It's possible his two hobbies get muddled up from time to time. He has written for several publishers in the UK and the USA, with pieces in anthologies, comics, and magazines. Follow him on Twitter as @CultTVMike, where he posts about all things sci-fi. Oh, OK, it's mostly Doctor Who.

My website is: https://perpetualstateofmildpanic.wordpress.com/

My latest project is this month's Outposts of Beyond.

And on to the interview . . .

Q: When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

A: I've wanted to be a writer for as long as I can remember. I looked at book covers as a young child, maybe five or six, and thought, "I want my name on a book." When I got into comics with 2000AD and then Star Wars Weekly, this would be when I was 7, that desire spread to wanting to be in the credits boxes in comic books, too. Unfortunately, as I got older, it became apparent that selling work wasn't going to be as easy as I'd initially thought.

I tried for a sustained period in my twenties to break into comics, but never got anywhere. At one comics convention in Bristol, while hauling my portfolio around, I got chatting with Matt Brooker, who was brutally honest with me. "Look," he said, "There's nothing particularly wrong with the way you draw, but there just aren't any openings. We hire on maybe one or two new freelancers a year and they have some quirk. You draw well, but there's nothing unique. To develop that style, you need to put in thousands of hours of practice, and you're not going to get paid for that. You don't strike me as independently wealthy, so I doubt you can afford to do it for free. So..."

He was right. I was dirt poor. I got a job in accountancy, which I hated. But at least I could go back to affording food.

Later, after years of doing things I loathed, and then teaching for several years in Japan, I immigrated here to the U.S. Starting a new career in Texas, I worked for seven years as a technical writer and editor, which helped me fine-tune my knowledge of English grammar and punctuation and gave me first-hand insight into how hard it is to express complex ideas in plain, no-nonsense sentences. I got enough feedback to sink a fleet of Titanics and developed a tough skin to criticism. I also learned how important it was not to treat my fellow writers the way I was treated, and I became a mentor to some of the newer team members. Although the working environment was hostile, I did love the act of writing and I found joy in helping others improve their written work.

While all that was going on, I was continuing to put out one or two pieces of my own writing. Teaching in Japan gives you a lot of spare time, so I'd started floating a few things past publishers. Moving to Texas, I was determined to keep that up, but stuck in a car for three or four hours a day on a hellish commute, working tons of extra, unpaid hours, and starting a family didn't leave a lot of spare time. It was only with our move to Iowa, where I still am now, that I found a better work-life balance and was able to kick the writing into high gear. To my inordinate surprise, I discovered that publishers wanted to print my short stories. Not only that, but readers showed every sign of liking them. I was flabbergasted.

I look back now and I see my name on a book cover and my name in a comic book credits box and I'm glad I never completely gave in. One of my best friends, Kath, said this to me years ago and it stuck with me: "What I like about you, Mike, is that you keep on trying." I'm sure she's forgotten ever saying that to me, but I remembered, and I've tried to stay that way.

Q: What would you say is your interesting writing quirk?

A: Oh, a 'quirk'! I have yet to develop one with my drawing, but with my writing...? Editors have often told me, in withering tones, that I over-write. You only have to glance at the length of this interview...

Also, as part of over-egging a box full of puddings in every story, I tend toward the proliferation of pleonasms. And uncalled-for alliteration.

If you catch me doing it, slap me.

Q: What do you like to do when you're not writing?

A: I watch lots of science fiction and read comics. I really enjoy reading stories to my two kids at bedtime, too. Honestly, with two young kids in the house, I spend a lot of time taking endless delight in everything they say and do. I try to carve out a few moments every day to remind my wife how much I appreciate her.

Q: How many books have you written? Which is your favorite?

A: I've had 10 short stories published professionally, with two more coming out in the next couple of months. A couple of those were my Titanville stories, which were published together in an e-book by Nomadic Delirium Press, getting me my first solo front-cover credit. I have a dozen more stories in slush piles as we speak, so one or two more will probably work their ways through to acceptance this year – that seems to be the typical ratio of stories sent to stories accepted.

I've also had a few stories in charity anthologies, and a couple of poems (one was about Star Trek and was printed by Iron Press in a collection sold throughout a major high-street chain of bookshops in the UK), a few non-fiction articles about the long-running BBC TV series Doctor Who in various tomes, and a comic strip script in the British small press comic Futurequake. Another comic script is being drawn now, as it happens, for Futurequake. We're hoping it'll be included in the Spring issue, but we'll see how that goes.

Oh, and I worked for a short while at an online word mill, putting out articles about sci-fi. You can find them at WhatCulture.com. They accumulated about three million page-views, I think.

Q: What inspires you to write?

A: I am drawn to the act of wrenching something into existence through the blunt application of imagination and willpower. I am compelled to create. For better or worse, you guys are on the receiving end of that compulsion.

When it comes down to deciding what I'm going to write about, I think there are some themes I keep returning to: the beauty in the world, the triumph of love and kindness over indifference and cruelty, the eternal fight against injustice, how any attempt to simplify the complexity of the real world down into stark black-and-white concepts will lead to hate and death...

Also, I love writing characters who are flat-out wrong. There's nothing more fun and more human than someone who is utterly convinced about the rightness of a cause, and that cause is based on an utter misunderstanding. Really, that type of thinking characterizes most of our species' history. People who are wrong deserve our sympathy, our help, our love, not our derision. Anyway, that's some entertaining stuff to write about.

One final thought – I don't want to be a downer but I do feel time pressing on me. Nothing like worrying I'll be dead in a few years to spur me to get some writing done.

Q: Do you set a plot or prefer going wherever an idea takes you?

A: I try to have a clear idea of what the story's about before I get too far down the rabbit hole of writing. Preferably, I have an end worked out as well, even if that ending changes by the time I get to it. Sometimes, I'll start the story with the end and work my way backward to the beginning. But there should always be a purpose to a story, even if that purpose is to have fun.

Every time I carve a tale out of the disorganized mess of my thoughts, the process seems different. One time, the whole story will spill out of me in a rush. Other times, I have to sit down and think through what I'm trying to express.

Every now and then, a neat idea will occur to me, but I can't find a way to get a coherent plot out of it. Then, a second, entirely different idea will come to me, and I find mashing the two disparate strands together into the same reality brings the whole thing into focus.

For example, someone having giant spiders in her home and not being bothered by them because they're not in any way dangerous is a neat mental image, but it's not a story in itself. But, add a second strand: imagine there's a neighbor whose job is to twist facts to meet political dogma and that neighbor comes into contact with those spiders... what happens? Does she believe the objective truth that they're completely safe to be around, or does she react with emotion and twist reality to meet that baseless viewpoint? After all, that's her job.

Boom – you have conflict. The wrong-headed, fact-denying neighbor suddenly at war with nice, harmless giant-sized arachnids. For no other reason than she can't see the truth in front of her face, which is a very common and very plausible failing. What's more, the story takes on a greater message: we shouldn't twist facts to meet our prejudices, no matter how tempted we'd be to do that if we were in the neighbor's shoes.

That's where A Spider Queen in Every Home came from, the mingling of two ideas that, on the face of it, can't coexist in a single narrative; but, they can, and that story was picked up and published in More Alternative Truths by B-Cubed Press.

Lastly, some publishers require that you pitch ideas. There, you have to submit a complete plot, along with character notes, up front. If a pitch is accepted, there's no scope for changing details along the way as you write the actual story. For all you know, by altering the agreed-upon tale without consultation, you might be encroaching upon territory occupied by another story in the same collection.

When fleshing out a pitch, it can feel like you're working while wearing a straightjacket. But it's an opportunity to find ways of making the piece as entertaining as possible without venturing beyond the plan you gave your word on. I've written a couple of stories based on pitches. Unto His Final Breath in Uffda Press's King of Ages: A King Arthur Anthology was created that way, and it garnered some nice reviews. I really like the world building I got to do in that short story.

Q: What types and forms of writing do you do? If you're also an editor, what is your niche?

A: I mostly write short stories these days, but I toy with novels. I do have a novel I'm working on (doesn't every writer?) - but, it's the short stories that sell. I am sneakily putting together various stories that work as elements within a greater whole, so that by the time they're all published you'll find they're a novel-length narrative printed in discrete parts across multiple publishers, books, and media. That's the idea, anyway.

For example, the Titanville stories stand alone as individual tales, but the intent is to have themes and sub-plots that build as time goes on, without requiring the reader to be familiar with every installment. The Age of Asmodeus stories have a similar approach; there's a history to that world, and each story explores a different sliver of it. As those stories go on, readers will see various characters moving in and out of segments of the series or they'll be referred to. Again, the readers won't need to read every story, but there'll be a sense of events moving forward for those who do.

With the tales featuring Professor Lazarus, the cumulative narrative will unfold using text-based stories and comic strips. Again, that's the hope. Futurequake, a British comic, has printed one story so far and has another one being drawn at the moment. With the short stories, I've had some luck; Flame Tree Publishing printed Fishing Expedition a while ago. I've written a couple more Lazarus stories since then that I'm waiting to hear back on, so we'll see how that goes.

But you were asking about types of writing. Occasionally, I have a poem published. More often, I'll get non-fiction pieces accepted. I contribute on a semi-regular basis to the range on media and culture put out by Watching Books. This year, they're printing a volume called You on Target about the Target series of Doctor Who novelizations, and I have two essays in that.

With editing, I offer my services to small presses who print my stories, with regards to proofreading or checking formatting. I'm always willing to help put out the best publication possible.

Q: What is your area(s) of subject matter expertise? How did you discover this niche? What intrigues you about it?

A: With living in Japan for several years, I found writing stories set there pretty easy. Not much research required! There's a story of mine being printed soon by you fine people at Alban Lake Press set in Japan. Kuro no Ken (The Back Sword) is slated for the next issue of Outposts of Beyond. The scenes in Ise City take place twenty minutes down the road from where I lived for three years, and the part in the vast cemetery—I've visited that cemetery and it really is that creepy. I love Japan. Those were some of the happiest years of my life.

Having said that, I lived for longer in Stoke-on-Trent in the UK, and that was the setting for Reverse Horror Story. Your fine company published that piece in Bloodbond just last year. I had way too much fun putting Stoke-themed jokes into that monster-mash-up. I guess, to answer your question, I'm an expert at shoe-horning places I've lived into my stories. I find having a deep knowledge of the settings makes them feel more authentic.

But, to be clear, I've never lived on the enormous asteroid Ceres, the setting of The Library of Ice in this month's Outposts of Beyond. I'd be willing to give it a try, though.

Being serious for a moment, I keep writing about people who are struggling because I've been through that. Want to be an expert on the poor? Try being unemployed for years on end, not having enough to eat and worrying about losing the room you're renting. That'll give you an understanding of what that life is like. Newsflash – it's really stressful and depressing.

Q: How do you balance your creative and work time?

A: I have yet to find any balance, but live in hope. I get the kids to bed in the evening and then try to write. Sometimes, I even succeed.

Q: Where have you been published? Upcoming publications? Awards and other accolades?

A: Other than the things I've already talked about, I'd like to mention Nomadic Delirium's Divided States series, which explores a post-USA North America. My contribution to this excellent range was The Wall Is Beautiful. I hope to finish a second story in this shared universe. I was also fortunate enough to have submissions accepted in their Martian Wave and Disharmony of the Spheres collections.

One other project I'm very proud to have participated in was Metasaga's Futuristica anthology. I had Something to Watch Over Us included in that amazing collection. I can't heap enough praise on that spectacular book; if you like science fiction, you need to own it.

As far as upcoming releases go, that I haven't already called attention to, I have a story called Buddy System accepted in Myriad Paradigm's upcoming Mind Candy anthology. The intent is for that book to be released in the next few months. I also have something in the editing pile with Red Ted Books, which should be advancing toward publication this year.

And, yes, it's a fanzine, but I like fanzines, I'm working with the wonderful people who put out the Doctor Who-themed Fannuals to see what they might want from me for their next volume. I'm so in love with the Fannual project; it's incredible fun. It's actually what I'm starting work on after finishing this interview.

Q: What are you working on now?

A: Well, Alban Lake announced they were going to do something with ghost stories, so, you know, I thought I'd try to submit to that. *Grins*

In the pipeline are more Age of Asmodeus tales, more Titanville, more Lazarus, more space opera antics, more of everything I'm obsessed with.

Q: Who are your favorite characters to write? How did they come into being, and what do you love - or loathe - about them?

A: I love writing about Professor Lazarus. She gives her life in every story, usually to save the world from some terrible fate. Then, next story, she's alive again, in a world that's transformed. It forces me to reinvent her and her milieu every time. And there's a point to all her deaths; it's leading to something.

She came into being because I thought, "Hah – killing the lead character every time would be funny." Then I thought, "What if it's the same lead character every time, and there's a reason she keeps coming back?" How does knowledge of her deaths affect her? Where, at a character level, does that propel the over-arching storyline?

Another fun character was Silas Smith in The Man Who Killed Computers (published in Disharmony of the Spheres). He's able to lie to computers and have them believe what he's saying. Once you realize how he's doing that, it's less amusing, because you also realize that he can manipulate the humans in the story. I love the ambiguity of his character. He tries so hard to convince everyone he's a hero—the story revolves around how others respond to his claims.

Q: Any advice you would like to give to aspiring writers?

A: If someone says you need to improve, he or she is probably right. Every writer needs to improve, every day. It's a process that never ends.

Don't take rejection personally. It's the work that sucks, not you.

Keep trying. Stories are only published if they're written and then submitted.

Realize that even after you've had a pile of stories published there will still be more defeats than victories. And that it's OK.

Anything else you’d like to add that I haven’t asked? For example, what would you like to see more of in your specific genre? In the publishing field?

We all like to get things for free. But—! Readers: try to pay for that fiction you're consuming. The more the publishers earn, the more they can pay the writers. The more the writers earn, the more they can write. It's a virtuous feedback loop. If you can't find good fiction out there, it's because you won't pay for it.

Or, you know, you haven't been to Alban Lake's store. There's lots of good writing there.

Once again, we’d like to thank Mr. Mike Morgan for his time and to thank all of you for supporting Alban Lake and all of these awesome authors and artists.

0 notes

Text

Issue #8: Lars Lerup

** **

Peter Koval: You said we tame objects by giving them names. It sounds like a little death.