#Herne the Hunter

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

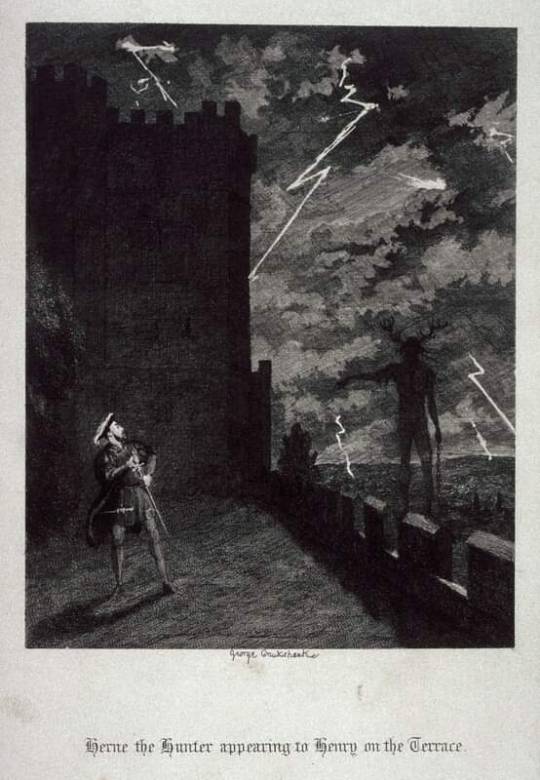

'Herne the Hunter' English folklore ghost who haunts Windsor with his hounds and an owl by George Cruikshank, 1843.

708 notes

·

View notes

Text

Keith Robinson, for the Robin of Sherwood Annual 1987.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

This winter solstice, the darkest day of the year, I wish you all peace, love and hope. As the days grow brighter, so may our troubled world. * Also, a heartfelt thank you to everyone who cheered me on through a year of personal struggle with likes and shares and encouraging comments. Your support for my art means the world to me ❤️ I didn’t have time to make a new and more appropriate card to go with this more-serious-than-normal message, so we’ll have to make do with season’s greetings from thirst trap Santa *ahem* I mean pagan fertility god. Hope he brings you a smile 🎅🏻❄️ (Somebody find him a sweater, it’s chilly out)

235 notes

·

View notes

Text

Robin of Sherwood - The Enchantment. Herne and Marian.

568 notes

·

View notes

Text

herne the hunter - some work from my current uni project! i’ve been in and out of hospital for a few months and being able to draw again has felt so good :-) looking forward to having more time for personal work too!

#art#digital art#fantasy#folklore#herne the hunter#british folklore#wild hunt#artists on tumblr#uni work

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cernunnos - A Confusion of Aspects

Introduction

This was supposed to be a simple bit of research that I was going to do as a devotional act to Cernunnos, but over the course of the night I kept encountering the same dead ends that pointed to the same singular source of misinformation. So do not expect this to be entirely objective.

Let's begin with a simple question: Who is Cernunnos?

A Gallic deity, with difficult to trace roots. Depicted sparingly, there is debate on whether or not various depictions can actually be attributed to him. Particularly, one of the most famous supposed depictions – the Gundestrup Cauldron – has been theorized by Celtic scholar John Matthews to depict a Shaman and not the god himself, according to his book The Celtic Shaman. Depiction variation and debate is not uncommon in discussion of older religions and cultures, particularly when Romanization and Christian censorship were at play. Not to mention Wiccan appropriation and repurposing of beliefs without regard for earlier context.

Others have made fantastic deep dives into potential depictions and discussed them at length, and I am no historical scholar, so I have little to add in this case. I highly recommend the essay The gods of Gaul: Cernunnos by @mask131 [1] for a piece regarding depictions through history.

Upon reading the previous essay, I was inspired to dig deeper into Cernunnos, from historical contexts to meditating on my own UPG via my connection with him. My own connection with him was something that happened casually over time, ranging from dreamlike interactions to conversing directly through divination. I am an incarnate Fae, and worship him as the King of the Fae, in addition to other aspects and epithets such as:

Cernunnos

King of the Fae

Master of the Sacrificial Hunt, The Horned God, and other Wiccan Concepts

Master of the Wild Hunt

Pan

The Green Man

Herne the Hunter

This list is influenced by a resource post of druidry.org[2], but I will be researching each of these titles for further insights into their sources and how they do or do not connect to my own practice ahead.

[1] mask131, Tumblr

[2] https://druidry.org/resources/cernnunos - this is not a reliable resource

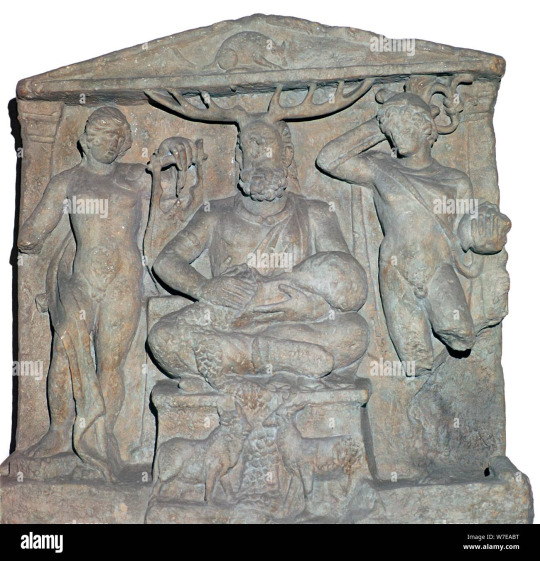

^ Cernunnos depiction on the Gundestrup Cauldron

Cernunnos

As learned in the previously linked essay, the name “Cernunnos” originates from the “Pillar of the Nautes” or the “Pillar of the Boatmen”, where the name is placed directly above a depiction of an antlered figure on the Block of Four Divinities[3] alongside the deity Smertrios. Many Gaul artifacts can be found in French museums. The Pillar of the Boatmen is attributed as a Roman-era inscription[4], so that gives us only enough information to hypothesize.

My takeaway from this is that the name Cernunnos is a modern approximation because of lacking, provable historical records, but rather serves a purpose as a modern placeholder. I came across information claiming that worship of Cernunnos as a deity was brought into modern belief by neo-pagans and popularized by Wiccans, particularly through Margaret Murray’s writings. During her studies of folklore in the early 20th century she put together a Witch-cult hypothesis that stated how a variety of horned deities were aspects of a “proto-horned god”[5]. In addition, this belief was adopted by Gerald Gardner and formed the basis of the concept of the Horned God within Wicca.[6]

“Sometimes also known as Carnonos, his name has firm Proto-Indo-European origins. It stems from the PIE word *k̑r̥no-, and is thus cognate to Germanic *hurnaz and Latin cornu, all meaning “horn”. In the Celtic Gaulish language, this word was karnon, and the connection with the name of Cernunnos is clear - it reflects the deity’s stag antlers, growing from his head. Thus, Cernunnos literally means “the horned one”.”[7]

Gallic history is sparse and difficult to pin down due to a lack of written records or literature. Multitudes of visual depictions dating from the Roman era have been attributed to Cernunnos by Archaeologists, having been retrieved from northern Gaul. These depictions are hypothesized to be this deity or others of similar archetypes. In addition, sites tend to use the words “Gallic” and “Gaelic” semi-interchangeably, despite the regional difference. Gael meaning a Celtic tribe from modern Ireland-Scotland, and Gaul meaning a tribe located in modern France. There is speculation that Cernunnos was a proto-Celtic deity, and could have had roots in any or all Celtic practices and beyond, but that is speculation because there is a lack of evidence to support the theory in any substantial direction.

[3] Name sourced from Athena Review, Vol. 4, No. 2, which also sources Huchard, V. (ed) Archéologica. 2003. “Le Pilier des Nautes Retrouvé. Histoire d’une Métamorphose.” Dijon, France. Éditions Faton S.A

[4] An observation attributed to Hatt, Jean-Jacques who recorded that the artifact was originally erected in 1st century AD.

[5] Margaret Murray, The God of the Witches

[6] Kathleen Sheppard Forced into the Fringes: Margaret Murray’s Witch-cult Hypothesis 21 April 2017

[7] According to Aleksa Vučković via ancient-origins.net

^Cernunnos's face as depicted of the Pillar of the Boatmen

King of the Fae - UPG

This title is predominantly UPG and relates to my own existence as an incarnate fae.

I find him similar but above other more location-based wild gods, beings like boar lords, and other guardians and rulers of nature. There is a loose hierarchy within fae politics, for lack of a better word, that is predominantly power based. Not as in subjugation over other beings, but rather quantified by expanse of control or domains. Finding the words for this section proves difficult, but he is simply above all of us, with a connection to all Fae. Cernunnos does not view himself as better than any of his subjects, he is not preoccupied with anything like that.

Does this title equate him with the concept of Oberon? No, I don’t believe so. He also exists outside of the seasonal courts, as he goes through a physical shift with the seasons instead of remaining in one form.

Master of the Sacrificial Hunt & The Horned God

Many modern depictions and associations with Cernunnos took their form via Wicca, as previously mentioned. The now heavily discounted Witch-cult hypothesis led to the adopting of the name as a common main aspect of Wicca’s concept of the Divine Masculine or the Horned God that absorbed many horned deities into one being, losing their individual status and becoming “aspects” of a central pillar. This is a theme often seen within Wicca and expands to their depiction of a central Divine Feminine deity as well, the pair often referred to as The Lord and The Lady. This is a simplification that I do not agree with. The epithet “Master of the Sacrificial Hunt” is unable to be sourced beyond the previous essay on Druidry.com and a repost of the same write-up on witchesofthecraft.com, so this title isn’t possible to verify. Although, mentions of Cernunnos identify him as a being that has a seasonal cycle of death and rebirth, which this epithet may be indicating. This belief appears to also have its basis within Wicca and lacks historical evidence. To quote from Wikipedia, “Within the Wiccan tradition, the Horned God reflects the seasons of the year in an annual cycle of life, death and rebirth

and his imagery is a blend of the Gaulish god Cernunnos, the Greek god Pan, The Green Man motif, and various other horned spirit imagery.”[8][9]

While I am large proponent of UPG, I do not abide by stating such concepts as strict facts. I will explore this further in future sections.

[8] Farrar, Stewart & Janet Eight Sabbats for Witches

[9] Doreen Valiente The Rebirth of Witchcraft pg 52-53

^The plaque I'm sure we've all seen in our local metaphysical store

Master of the Wild Hunt

The Wild Hunt is a concept that permeates the history of many European cultures, including the Celts.[10] Myths of Wild Hunts would most often include a central figure flanked by hunters all in pursuit of some kind of special quarry. Within Germanic legend, the mythical figure is often Odin, but there were many other figures that have been featured across cultures and belief systems, sometimes historical and other times religious. The hunters were often depicted as fairies, the souls of the dead, or otherwise inhuman participants. Witnessing the spectacle as a mortal was thought to bring calamity[11], death, or abduction to magical realms. The concept and term were popularized by German author Jacob Grimm, originally as Wilde Jagd.[12]

This mythological concept existed in various aspects of Germanic and European folklore, across multiple cultures. Despite this, the lack of Gallic literature means that we are unable to directly connect Cernunnos to any historical uses. The prevalence of this type of myth, though, presents the obvious opportunity to incorporate our modern understanding of him into the framework to explore our own UPG. This is a topic I may meditate on further if I do further research into the concept of the Wild Hunt.

My own personal experiences with the concept are much more play oriented. If you’ve ever been to a Beltane festival, you probably know the heady feeling of being chased through the woods before being caught and celebrating the season. This interactive ritual-made-game is a fun staple you may find on the schedule of any fertility event these days meant to drive up sexually charged, excited energy. It’s a simple enough concept to incorporate into any individual practitioner’s holiday plan, if it suits your preference. Especially as a Fae, I find the concept of the Wild Hunt to be something fun to engage in with a special partner or community, and find no harm in inserting anyone into the role of Master of the Wild Hunt, as the prevalence of the format leaving the form of individual story to expand into a genre.

[10] Stith Thompson (1977) The Folktale University of California Press pg 257

[11] See, for example, Chambers's Encyclopaedia, 1901, s.v. "Wild Hunt": "[Gabriel's Hounds] ... portend death or calamity to the house over which they hang"; "the cry of the Seven Whistlers ... a death omen".

[12] Deutsche Mythologie (1835)

^Johann Wilhelm Cordes: Die Wilde Jagd (The Wild Hunt)1856/57

Pan

The conflation of Pan with Cernunnos appears to be predominantly based in the view of all male horned deities being simple aspects of a larger presence – the Wiccan Horned God. As previously stated, I do not support that concept and will use this section to study Pan as a separate entity and cover where in my UPG they overlap.

Pan is the Greek god of the wilds, music, and a guardian of shepherds and their flocks. He also was usually in the presence of nymphs.[13] Unlike the Stag depictions and associations of Cernunnos, Pan sported the legs and horns of a goat and appeared similar to a Satyr. His domain expanded to agricultural and wooded areas, as well as the realms of sex and fertility. The sum of those parts was to present him as a god of the season of Spring. He had a Roman equivalent in the god Faunus, and was also conflated with another known as Silvanus at times. Pan became a popular god during the 20th century neopagan revival[14].

Even before that, worship of him was brought back by a festival originating in Painswick, Gloucestershire by Benjamin Hyett, who also constructed various holy places in the god’s name.[15] Other popular occultists of the early 1900’s such as Aleister Crowley also crossed paths with Pan, as he built an altar to the god and wrote a ritual play about him.[16] After that point, his image and general description was absorbed into the Wiccan Horned God concept after Margaret Murray’s The God of the Witches posed the idea that he was simply one part of an overarching whole.

But who was Pan outside of this, particularly who was he before the Witch-god hypothesis altered how future generations would see him?

Pan is considered by some scholars to be a reconstruction of a Proto-Indo-European pastoral deity[17], as well as Pushan, a god originating from Rigvedic that also shared goat traits.[18]

Beyond these source hypotheses, there is evidence that Pan was first worshipped in the mountainous, isolated area of Arcadia. In that area, if a hunt wasn’t satisfactory, disgruntled hunters would scourge, or whip, the statue of Pan.[19] At this time, there were no formal temples to Pan, and worship was instead pursued in woodlands and other natural spaces. While exemptions from this rule did exist, they were few and far between.[20] He predates the Olympians, like many Grecian nature spirits. I won’t go too in depth regarding direct mythology, as its difficult to do that with the Greek pantheon without tangents.

Pan was viewed as a height of sexual prowess, and agricultural success. He had a history of dalliances with Nymphs, to put it lightly, often depicted as being controlled by his lust and anger. Such as in the myth of the Nymph Echo, whom he ordered killed when she denied any man. In some versions, the pair even have two children, or perhaps chose Narcissus over him, no matter the variation he is usually painted as rash and jealous. I’m sure we’ve all seen that statue of Pan and the goat that resides in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.

The word “panic” can trace its sources back to him, but I was surprised to find that “pandemonium” does not.[21]

In my personal view, Cernunnos ages with the seasons, being at his most virile in the Spring, then maturing into his form as a guardian of the dead come winter, appearing dead himself. This is relevant in that I find the depictions of the lustful, energetic Pan to be inspiring of how I see that Spring form. Beyond that, the agricultural and animal connections are similar, but seem to take very different forms upon closer inspection.

Within actual historical context, there doesn’t seem to be anything connecting Cernunnos and Pan in any way beyond neo-pagan labelling.

[13] Edwin L. Brown, "The Lycidas of Theocritus Idyll 7", Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, 1981:59–100.

[14] The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft, Hutton, Ronald, chapter 3

[15] Hutton, Ronald. The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft pp 161–162.

[16] Soar, Katy (2020). "The Great Pan in Albion". Hellebore. 2 (The Wild Gods Issue): 14–27.

[17] Mallory, J. P.; Adams, D. Q. (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 434

[18] H. Collitz, "Wodan, Hermes und Pushan," Festskrift tillägnad Hugo Pipping pȧ hans sextioȧrsdag den 5 November 1924 1924, pp 574–587.

[19] Theocritus. vii. 107

[20] Horbury, William (1992). Jewish Inscriptions of Graeco-Roman Egypt. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 208.

[21] Coined by John Milton in his poem “Paradise Lost” coming from the Greek pan- “all” and daemonium “evil spirit”

^Mask of the god Pan, detail from a bronze stamnoid situla, 340–320 BC, part of the Vassil Bojkov Collection, Sofia, Bulgaria (It is shockingly difficult to find art of Pan where he's not rock hard.)

The Green Man

Viewed as more of a motif or concept than a deity, the Green Man originated in England and was usually depicted as covered in leaves and sometimes armed with a club. One might encounter these visuals in parades, festivals, or painted on the signs of many pubs come the 17th century. This changed with the introduction of Julia Somerset, who claimed in the Folklore journal that the design often seen on church walls actually had pagan origins as some kind of fertility deity.[22] There is no evidence to support this claim, and it has been contested by many folklorists.[23] This assertion by Somerset was then absorbed into the Wiccan Horned God despite being described as distinctly “20th Century Folklore”.[24]

That’s pretty much the extent of this one and was honestly one of the most shocking to read about. The Green Man was at best a regional icon used in local festivities but was never any kind of deity. That title was misrepresented and incorporated without research.

My personal association would be the visuals of Winter, but Cernunnos’ Winter form appears very differently to me. More skeletal stag, less old man with a holly beard.

[22] Centerwall, Brandon S. (January 1997). "The Name of the Green Man". Folklore. 108 (1–2): 25–33.

[23] Livingstone, Josephine (2016-03-07). "The Remarkable Persistence of the Green Man". The New Yorker.

[24] Olmstead, Molly (2023-04-08). "Is the Green Man British Enough for the Royal Coronation?". Slate.

^A sign for the John Barras Pub Company

Herne the Hunter

After the last section, it is a relief to move on to something that has always been presented to me with its original fictional context intact. Herne the Hunter was a character originally depicted in The Merry Wive of Windsor written by Shakespeare in approximately 1597. Supposedly, Herne the Hunter is an antlered spirit that occupies the Royal Forest in England, occupying himself with tormenting cattle and rattling chains. While the character may have been based on local legends to some degree, it is unknown just how much verifiable connection has ever existed. Attempts to connection him to other deities or legends were made often after he was written.

There is an old tale goes, that Herne the Hunter

(sometime a keeper here in Windsor Forest)

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg'd horns;

And there he blasts the tree, and takes the cattle,

And makes milch-kine yield blood, and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner.

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Receiv'd, and did deliver to our age

This tale of Herne the Hunter for a truth.

— William Shakespeare, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Act 4, scene 4

Despite Herne being a location-based character appearing only in the areas Windsor Forest occupied, certain books published in 1929 and 1933[25] attempted to identify him with Cernunnos and other horned deities. This is again the connection through which Wiccans incorporated Herne into the Horned God.[26]

[25] The History of the Devil – The Horned God of the West by R. Lowe Thompson; The God of the Witches by Margaret Murray

[26] 'Simple Wicca: A simple wisdom book' by Michele Morgan, Conari, 2000

^Illustration of Herne the Hunter by George Cruikshank (1840s)

Romanizations

There are theories mentioned in mask131’s essay regarding attempts at identifying what Roman deity or deities was meant to be the equivalent of Cernunnos, but there is sadly only speculation on that front. Opinions vary from person to person, but parallels are often drawn to Dis Pater and Mercury for shared traits. I did find instances such as the Lyon Cup and an altar from Reims that feature Mercury and Cernunnos depicted side by side, so I believe it is safe to say that they were at least at some point considered fully separate beings.

^1st-century CE altar from Reims with Cernunnos, accompanied by Apollo and Mercury. Mercury has a cornucopia, while Cernunnos spills grain.

Aside – Misinformation is Rampant

This one book, this one fucking “hypothesis”, changed the entire face of what would eventually become modern neopaganism. The damage of the Witch-cult hypothesis is far reaching and permeates every resource I could find while writing this piece aside from the explicitly scholarly. It is extremely discouraging how quickly you can trace something that feels off back to this one woman’s massively disproven theory that was adopted by a man that wanted to make a religion based on occult foundations because he admired ceremonial magic. The frustration I feel as someone trying to do research now after this misinformation and pseudohistory has seeped into every aspect of the path has me constantly on edge and second guessing everything I read until I can find a source.

Stating UPG as undeniable fact that others must agree with isn’t great at the best of times, but the sheer level of ignorance to historical record seems to be running rampant within the modern Pagan community. I’m all for believing something unverifiable, something that’s only true for you, or for the world from your perspective, but there is and must be a difference between that and presenting easily disproven statements as unbreakable law, especially with they come hand in hand with any dressings like, “this is actually true because I was told so by this person, who learned from this other person.” And the process is traceable to the source they borrowed from and how it was completely disproven.

We must think critically within paganism, research beyond the books with flashy covers in Barnes & Noble and question the things we are told by others are just the way things are.

Your relationship with the gods is yours alone and can take any form you want it to. Don’t let yourself be trapped by ignorance. Learn about historical contexts, question sources, seeking mentoring from those who revel in your questions and help you find the answers.

Conclusion

Cernunnos is a deity that is beyond valuable to communicate with directly due to the lack of concrete historical and folkloric information, and the prevalence of blatant misinformation that uses his name. Context is important, and even if you choose to exist outside of it, which is a perfectly valid choice, it should be a conscious one.

In addition, while attempting to research this, I actually stumbled upon sites not just with AI generated cover images, but what fully appeared to be AI generated writing. Be vigilant against information that looks like someone just skimmed the surface and made an assumption, this page had a lot of almost correct or just flat out made up information that contradicts historical fact. Especially in this modern era where people use automatic programs to make summaries of summaries for a game of unverifiable internet telephone, be aware. No matter what your personal stance on AI is, I'm sure we can all stand against information atrophy.

To me, Cernunnos is a supportive, ever-present god that helps me through things in his own way, meaning that its usually something intense and then coming out the other side putting out a fire on the back of my head. He's hands-off, and wants me to admire the turning of the seasons from new angles. He's opened my eyes to a deeper respect for other belief systems, and encouraged me to do this research so that I could better understand him as well as our own connection. He wants me to be observant and always keep learning and questioning and growing in my faith, in my magic, in my role as a faery.

When it comes to the belief systems that you rely on in life, ignorance is not bliss. Seek knowledge deep in the forest and on the frozen boundaries of a lake or standing barefoot in a grassy meadow, but also in historical records. Anyone who wants the best for you will want you to research and learn more.

Genuinely as I was finishing this up last night, adding this section to the post version the next morning, I considered becoming a YouTube essay person. Maybe someday! Perhaps an actual blog. Researching and writing this kind of thing was actually very fun. I never even did something like this while I was in school, so maybe I'm just not traumatized by the concept. Anyways, I hope this was informative and you enjoyed a peek into the journey I took while putting this together.

Now I'm gonna go light up some green in dedication to Cernunnos ✌︎︎♡⃛

^The Lyon Cup, sometimes identified as Cernunnos

#witch#witchcraft#magic#witchblr#witchy#me#pagan#personal#cernunnos#celtic paganism#paganism#herne the hunter#pan#the green man#wild hunt#fae#fairy#faekin#fae kin#the horned god#wicca#margaret murray#witch-cult hypothesis#gerald gardner#wiccan#history#folklore#essay#advwitchblr#grownasswitches

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Oak and the Holly King, and their solstice showdown.

(Scroll down for the story)

The oak and holly king

The story of the Oak and Holly Kings is deeply rooted in ancient folklore, particularly within Celtic and Druidic traditions, although it’s important to note that the specific narrative as we know it today—of these two kings battling for dominion over the seasons—has been shaped and revived in more recent times by modern Pagan and Wiccan traditions. However, the roots of the story stretch far back to pre-Christian beliefs about the cycles of nature, the power of the solstices, and the worship of sacred trees.

Ancient Connections to Sacred Trees

The concept of sacred trees, particularly the oak, is central to many ancient traditions. The oak was highly revered by the Celts, who saw it as the King of the Forest. It symbolized strength, endurance, and the masculine principle. The oak’s deep roots in the earth and its towering presence in the forest made it a symbol of vitality and life, particularly associated with the sun and the summer months.

The holly, by contrast, had a more mystical and protective role. Its evergreen leaves and bright red berries made it stand out during the harsh winter months, when much of the landscape lay dormant. The Celts associated the holly with winter and the darker months, seeing it as a symbol of protection, fertility, and resilience. In Druidic lore, the holly tree was often seen as a guardian spirit of the underworld, which connects it to the realm of death and renewal.

These two trees represent opposites in the cycle of life—life and death, light and dark, and growth and decay—which is why they became symbolic of the eternal rhythm of the seasons.

The Battle of the Oak and Holly Kings in Celtic Mythology

The story of the Oak and Holly Kings doesn’t appear verbatim in ancient Celtic texts, but the thematic elements are strongly aligned with Celtic beliefs in seasonal cycles and the interplay between the forces of light and dark. The Celts understood time as cyclical, with the changing of the seasons seen as a battle between opposing forces. This is most evident in their mythologies, which often feature gods and goddesses who personified the seasons or the solar cycles.

While the Oak King is not a figure explicitly named in ancient Celtic myths, his association with the summer solstice and the sun aligns closely with deities like the Green Man, the Horned God, or the Sun God, such as Lugh or Belenus, who were central to Celtic religion and worshipped at the height of summer. The Oak King represents the rising power of the sun, growing in strength as the days lengthen.

The Holly King, on the other hand, is a figure whose influence is less direct in ancient mythology but who fits well within the framework of the Winter Solstice—a time when the light retreats and the darkness reigns. His connection with holly, a plant that thrives in winter, also connects him with ancient symbols of death, rebirth, and the protective, purifying powers of the dark. He can be seen as analogous to the Celtic figures of the Dark God or the Horned God in his aspect of winter, death, and renewal. The idea of a ruler of the dark half of the year is reflected in the figure of Cailleach, the Celtic winter goddess who reigns over the harsh cold months.

The Solstices as Turning Points

The idea of a battle for dominance between the Oak and Holly Kings aligns with the Winter Solstice and Summer Solstice, key turning points in the year when the sun is either at its lowest or highest point in the sky. The Solstices were of great importance to the Celts and other ancient peoples, as they marked the changing of the seasons and the movement between light and dark.

At the Winter Solstice, the Holly King’s reign over the dark half of the year reaches its peak, but as the Oak King slowly begins to take over, the days lengthen, and the sun begins its return. The reverse happens at the Summer Solstice, when the Oak King’s reign begins to wane, and the Holly King rises to claim dominion over the dark months again.

The Modern Revival

The modern retelling of the Oak and Holly Kings battle comes from a blending of old Celtic traditions with newer Pagan and Wiccan beliefs, particularly in the 20th century. Figures like Gerald Gardner, one of the founders of modern Wicca, and later Pagan writers like Doreen Valiente and Starhawk, helped to shape and popularize the idea of the Oak and Holly Kings as two mythical figures representing the seasonal battle between light and dark.

These contemporary adaptations often draw on the traditional symbolism of these trees, the changing seasons, and the Solstices, but the exact story as we know it today is largely a modern creation, inspired by the themes present in ancient Celtic myth, and perhaps even influenced by folklore surrounding the Green Man and the Cailleach, two figures whose stories embody similar cyclical changes in the natural world.

Summary: An Archetypal Tale of Balance

The Battle of the Oak and Holly Kings is less about a specific historical or mythological origin and more about a universal archetype: the dance of light and dark, life and death, summer and winter. It’s a story that, although not fully documented in ancient myths, resonates with ancient practices and beliefs tied to the natural world. It serves as a reminder that all things are in constant flux, and the forces of light and dark are not in opposition, but in balance—a relationship that sustains the very cycle of life.

So, while the Oak and Holly Kings may not have been named explicitly in ancient Celtic myth, the themes of their battle—of shifting power, of cyclical renewal, of the eternal dance between light and dark—are deeply embedded in the seasonal rhythms of the earth, making their story one that continues to inspire and resonate today.

Conclusion: The Blessing of the Oak and Holly Kings

As the Wheel of the Year turns once more, the Winter Solstice marks a sacred transition—when darkness reaches its peak and light begins its slow, steady return. The Oak King and the Holly King, locked in their eternal dance, remind us of the beautiful balance within all things: light and shadow, growth and rest, life and death. The Holly King, ruler of the waning year, gently steps aside, honouring his role in holding space for introspection, endurance, and the lessons of the dark. The Oak King, vibrant with potential, rises to bring light and renewal, promising growth and the slow awakening of the earth.

This ancient story is not just a tale of two kings—it’s a reflection of the cycles we all live through. In our own lives, there are moments to honour the Holly King within us, letting go, retreating, and seeking wisdom in stillness. And there are moments to welcome the Oak King, embracing light, action, and the promise of new beginnings. Together, they remind us that every end carries the seed of a beginning, and every winter holds the quiet promise of spring.

A Blessing for the Oak and Holly Kings

To the Holly King, Keeper of the Dark:

May your rest be peaceful, your wisdom honoured,

And your gift of stillness held in gratitude.

You who guard the night and protect the soul’s journey,

We thank you for your strength and patience.

May we carry your lessons of endurance and grace as we move forward.

To the Oak King, Bringer of the Light:

May your reign be bright, your energy abundant,

And your gift of renewal inspire growth within us.

You who awaken the earth and kindle the fires of hope,

We welcome your return with open hearts.

May we walk boldly into the light you bring,

Guided by courage, wisdom, and joy.

And to the Dance of the Year that unites them both:

Blessed be the turning of the Wheel,

Blessed be the balance of dark and light,

Blessed be the cycle of life everlasting.

So it is, and so it shall be.

Follow Tbe Lantern’s

Glow

#yuletide#yule#winter solstice#paganism#modern paganism#storytime#the wheel of the year#folklore#witchcraft#eclectic wicca#Spotify#cernunnos#herne the hunter#the green man#wildwood

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Phantoms of the Forest featuring Herne the Hunter from Spellbound No. 61, 19 November 1977. DC Thomson.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

George Cruikshank, Herne the Hunter appearing to Henry on the terrace; 1843

#george cruikshank#herne the hunter#art#artwork#dark art#dark artwork#esoteric#esoteric art#esoteric artwork

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

29th January

Herne the Hunter

Source: Herne the Hunter on Craiyon

On this day in 1906, the ancient tree, Herne’s Oak was replanted in Windsor Park, Berkshire. According to legend, Herne was a skilled hunter who saved the life of King Henry VIII by placing himself between the monarch and a charging stag. Herne was made Henry’s chief huntsman as a reward, but jealous gossip ultimately led to the hero’s dismissal from the king’s service. A distraught Herne then killed himself. But his story did not end there. In death, Herne transformed in a giant stag-masked hunting god, and has haunted the woods of Windsor Park ever since, leading phantom hounds in a never-ending pursuit of spectral stags. Herne was believed to be real enough, appearing in Shakespeare’s Merry Wives of Windsor to terrify a drink-addled Falstaff. The unwary are advised to flee at the sight of Herne, whose bow has been known to seek human victims as well as the creatures of the forest.

Herne is almost certainly a Tudor memory of the Celtic god of the Underworld, the winter deity, stag-headed Cernunnos. The god’s manifestation, like that of Herne, is best avoided by mortals.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holding my heart,

in your hand,

Horned head raised high,

proud and pristine.

O’ Herne,

Hunter of the Hills,

you protect my presence,

make home for my heart,

and guide my judgment.

For it is you

who roams the land

and doing so

holds my hand.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

why is my newest hyper fixation cernunnos and the wild hunt?? who knows. am I writing I planning out a 70k tomarry fanfic with celtic mythology because of it?? yes.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hail to the Horned One! The Stag of the Green Wood Grove! The Goat of the Dark Forest! God of the Fertile Earth! I Hail To You! Cernunnos, Pan, Herne! Hail to you, Ol’ Hornie! Hail to you, god of a thousand names!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lore | Horned God

[This one is a little longer]

Horned God may in fact be the horned GODDESS [hypothetically]

[Deer Goddess]

The Horned gods origins are a little tricky. There are sources that claim that the Horned god was originally the horned goddess. Cernunnos, originally derived from old pagan myths of a horned ‘Goddess’ , a story about how a deer would turn into a woman. In folklore society in 1930, a researcher put his theories on a matriarchal Hunter gatherer society ruling highlands of scotland as a pre-celtic deer cult. J.G. Mckay.

Modern Scottish Gaelic and modern Irish Gaelic dictionaries both give the word Fiadh having two meanings: “Deer,” “God.” The deer was some sort of god, as well as divine messenger, some type to the Goddess Artemis. How you had to ask permission to hunt.

In Faerie lore, deer are their cattle and a common form of Faire women, Witches can transform into mice, hares, cats or black sheep but never the sacred deer.

In many pagan animal-cults, the priest or priestess would often wear an ornamental headdress of the sacred animal. There are Scottish folktales of a deer woman that Mckay theories could be explained by this real practice. In these folktales, a hunter, who has been stalking deer, observes, when putting up his gun to take aim, that the animal changed into a woman. He falls in love with her. Adventures ensue and they are separated until he finds her again on a distant island and they finally marry and live happily ever after.

The Deer Cult and the deer-goddess cult date back from a remote matriarchal time. Diana as well as Artemis and her nymphs, would appear to be classical examples of a hint at this older heritage. No one in patripotestal times, it would seem, would dream of inventing a feminine hunting divinity.

Celtic Society developed and created a masculine Horned God from the deer goddess and keep the feminine character next to him as a reminder as his shadow. By the stage the Deer Goddess matriarchy would have been in decay and her worshippers have grown fewer. While worshippers of the male Cernunnos became ever more numerous.

Today, there are whispers of this old Deer Goddess Cult in traditional German and English stag dances that are performed by men who dress themselves in women’s clothes, thereby preserving a memory of a former time when stag-dances were perfect by women, and of a later time, when the religious functions of women were usurped by men.

Shakspearen roots.

Swiftly moving on a couple thousand years, we come to the iconic bard, Shakespeare. Elizabethan english comedy abounds with images of the cuckold- a man with horns on his head, symbolising his shame that his wife has taken up with another man-

Herne the Hunter- from Shakespeare to popular culture. So at least thats where the name came from.

Robin Hood Myth [Horned God]

[Authors note: This website is not secured so take care also- these types of websites were the ones I’ve seen and how I came to know about Wicca]

The Horned God is the father of Robin Hood? And it’s Pagan?

The Horned god is a central theme/character in many european pagan faiths. Generally seen as a deity of woods, wild animals, hunting and virility he is an elemental force of nature and commonly identified as a male deity often the consort of the female force or earth mother.

This is the case in the Wicca religion where the horned god is worshipped as both the child and the consort of the great Mother, Triple Goddess.

There are some evidence that the idea of the ‘Lord’ and ‘Lady’ in Wicca is part of ancient tribal rites but such evidence is limited.

For many modern Wiccans the ‘Horned God’ sometimes known as the Great God or Great Father is his own father.

Mating with the Goddess at Beltaine then dying at Summer Solstice only to be reborn as her child at the new year, or Winter Solstice, he is a key symbol in the birth/death/Rebirth cycle.

The Horned God is known as the ‘Hunter’ has strong links in Britain with the idea of ‘Wild Hunt’ he is the taker of life, a vengeful spirit, hunting evil with a pack of demonic hounds.

He is often portrayed as carrying a bow.

The british Herne the HUnter is rumoured to survive still as a powerful spirit.

Herne is linked to Robin Hood just as Robin provided for the needy, Herne provided food for the tribe.

In some legends he is listed as Robin Hoods father, although this adds greater status to Robin Hoods legends.

He is portrayed has either having horns or Antlers, as well as his image is full of Phallic symbols.

Locations: There have been representations of Fertility icons for thousands of years as in the Altars of Stag Horns which have been found in Temples of Apollo and Diana in ancient Greece.

He is sometimes depicted with hooves or Goat hindquarters, a link to the Greek God Pan. Which of course had christians mistaken this horned fello for Satan.

Stag God image can be found in a cave painting at Trosi-Freres in France. This painting is thought to date around 13,000 BC known as the “Sorcerer” and depicts a half human, half stag spirit. This image is often seen as a representation of a shaman dressed as a stag performing a rite to ensure good hunting.

The Horned God is not an exclusively Wiccan concept as one would expect as many Pagan faiths have similar roots, the Horned god concept can be seen in the Greek God Pan, the Celtic god of the underworld and animals cernunnos, the Roman Janys, Tammuz and Damuzi the consorts of Ishtar and Inanna, Osiris and Dionysus as well as the Green Man mythological figure in the Uk.

The link with Osiris and Cernunnos which were both gods which guarded the underworld or judged souls and Osiris was both brother and consort of Isis seen by many as the Egyptian mother goddess. Cernunnos was a fertility god of the pagan celts and Gauls and is thought by many to have been the basis for the christian concept of the horned devil being a half man half goat guardian of the underworld and certainly a rival faith for early christianity.

The link between the Horned God and the Green man in English folk lore is very strong and even today many pubs in UK villages bare the name “The Green Man” often with a very pagan image on the pub sign. The Green man also known as ‘Green Jack’ or ‘Jack in the Green’ is an English spirit of trees and plants with the power to make it rain and crops grow well. The Green man is thought to share his home in the forest with forest fairies sometimes called “Greencoates” or Greenies depending on the region of the UK. In popular imagery the Green man is shown as face peering out of foliage, his wood spirit companions and fertility imagery clearly links him to Pan and also as a sort of sanitised Hern the Hunter and Wild hunter.

For many modern Druids and Wicca the Horned god is a key part of the birth, death, rebirth cycle and mentioned in many rites and celebrations, his imagery is powerful and has a strong attraction to many as a symbol of almost suppressed power / violence and male sexuality. Some modern pagans reenact the ancient rite where the hunter who brought the most/ best meat to the table was dressed in stag horns and furs and was rewarded with the right to couple with the priestess representing the goddess sometimes in front of the whole tribe. The few pagan groups that reenact this mostly do so symbolically or with the hunter and goddess being intimate partners already with only a small part of this “Great Rite” being performed before the rest of the coven.

#horned#god#horned god#LORE#witch#witchtok#witch community#witchcraft#witchblr#wiccan#pagan#wicca#Pan#belief#wiccan religion#baby witch#baby#Herne the Hunter#herne#the#hunter

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 1/1

Fandom: Robin of Sherwood (TV 1984)

Rating: Teen and Up Audiences

Warning: Major Character Death

Relationships: Robert of Huntingdon & Marion of Leaford, Robert of Huntingdon & Will Scarlet, Robert of Huntingdon & Friar Tuck, Robert of Huntingdon & Merry Men, Robert of Huntingdon & Herne the Hunter

Characters: Robert of Huntingdon, Marion of Leaford, Will Scarlet, Friar Tuck, Little John, Much the Miller’s Son, Nasir (Robin of Sherwood), Herne the Hunter, Robin of Loxley (mentioned)

Additional Tags: Alternate Universe - Canon Divergence, 2x07/3x01 rewrite, Robert doesn’t reject the call, And accepts his destiny as Herne’s son, Introspection, Grief/Mourning, Developing Friendships, (though there’s still a way to go), Some of the Merries don’t really talk to him hence why they’re only in the character tags, No one actually dies in this fic but Robin’s death is mentioned so I’m just being cautious, Robert is also more aware of his privilege than in canon

Summary: Eighteen-year-old Robert of Huntingdon, despite his intial reservations, decides he'll remain and become Herne's son - but still worries about the reaction of the Merries, and whether he can truly take on the mantle.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#yea id probably abandon my throne to chase him through the forest for centuries. i can see myself doing that#but NOT for hunting. for a hug#animals(via@sashayed)

“Albino Deer” by Herve Balland

#Herve Balland#sashayed#Peer Review#Photography#Albino Deer#White Hind#White Stag#Mythology#Arthuriana#Gaelic Myth#Herne the Hunter#appreciative reblogs

33K notes

·

View notes