#Herbert Adkins

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

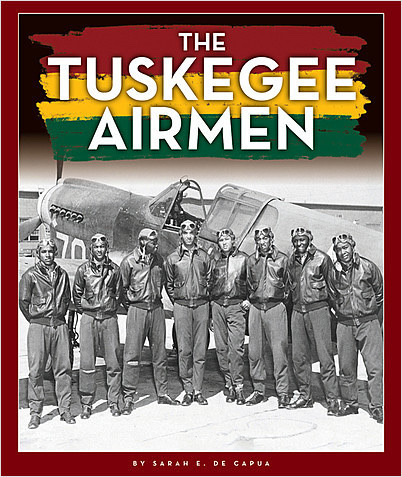

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of African-American and Caribbean-born military pilots who fought in WWII. They formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the Army Air Forces. The name applies to the navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs, nurses, cooks, and other support personnel.

All African American military pilots who trained in the US trained at Moton Field, the Tuskegee Army Air Field, and were educated at Tuskegee University. The group included five Haitians from the Haitian Air Force and one pilot from Trinidad. It included a Hispanic or Latino airman born in the Dominican Republic.

March 22, 1942 - The first five cadets graduate from the Tuskegee Flying School: Captain Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. and Second Lieutenants Mac Ross,

Charles DeBow, L.R. Curtis, and George S. Roberts. They will become part of my the famous 99th Pursuit Squadron. List of Tuskegge Airmen.

Paul Adams (pilot)

Rutherford H. Adkins

Halbert Alexander

William Armstrong

Lee Archer

Robert Ashby

William Bartley

Howard Baugh

Henry Cabot Lodge Bohler

George L. Brown

Harold Brown

Roscoe Brown

Victor W. Butler

William Burden

William A. Campbell

Herbert Carter

Raymond Cassagnol

Eugene Calvin Cheatham Jr.

Herbert V. Clark

Granville C. Coggs

Thomas T.J. Collins

Milton Crenchaw

Woodrow Crockett

Lemuel R. Custis

Floyd J. Crawthon Jr

Doodie Head

Clarence Dart

Alfonza W. Davis

Benjamin O. Davis Jr. (C/O)

Charles DeBow

Wilfred DeFour

Gene Derricotte

Lawrence Dickson

Charles W. Dryden

John Ellis Edwards

Leslie Edwards Jr.

Thomas Ellis

Joseph Elsberry

Leavie Farro Jr

James Clayton Flowers

Julius Freeman

Robert Friend (pilot)

William J. Faulkner Jr.

Joseph Gomer

Alfred Gorham

Oliver Goodall

Garry Fuller

James H. Harvey

Donald A. Hawkins

Kenneth R. Hawkins

Raymond V. Haysbert

Percy Heath

Maycie Herrington

Mitchell Higginbotham

William Lee Hill

Esteban Hotesse

George Hudson Jr.

Lincoln Hudson

George J. Iles

Eugene B. Jackson

Daniel "Chappie" James Jr.

Alexander Jefferson

Buford A. Johnson

Herman A. Johnson

Theodore Johnson

Celestus King III

James Johnson Kelly

James B. Knighten

Erwin B. Lawrence Jr.

Clarence D. Lester

Theodore Lumpkin Jr

John Lyle

Hiram Mann

Walter Manning

Robert L. Martin

Armour G. McDaniel

Charles McGee

Faythe A. McGinnis

John "Mule" Miles

John Mosley

Fitzroy Newsum

Norman L Northcross

Noel F. Parrish

Alix Pasquet

Wendell O. Pruitt

Louis R. Purnell Sr.

Wallace P. Reed

William E. Rice

Eugene J. Richardson, Jr.

George S. Roberts

Lawrence E. Roberts

Isaiah Edward Robinson Jr.

Willie Rogers

Mac Ross

Robert Searcy

David Showell

Wilmeth Sidat-Singh

Eugene Smith

Calvin J. Spann

Vernon Sport

Lowell Steward

Harry Stewart, Jr.

Charles "Chuck" Stone Jr.

Percy Sutton

Alva Temple

Roger Terry

Lucius Theus

Edward L. Toppins

Robert B. Tresville

Andrew D. Turner

Herbert Thorpe

Richard Thorpe

Thomas Franklin Vaughns

Virgil Richardson

William Harold Walker

Spann Watson

Luke J. Weathers, Jr.

Sherman W. White

Malvin "Mal" Whitfield

James T. Wiley

Oscar Lawton Wilkerson

Henry Wise Jr.

Kenneth Wofford

Coleman Young

Perry H. Young Jr.

#africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harts News 11.27.1925

An unnamed correspondent from Harts in Lincoln County, West Virginia, offered the following items, which the Logan Banner printed on November 27, 1925: Business seems to be improving at Harts now. Messrs. Herbert and Watson Adkins made a flying business trip to Ranger Tuesday. Mrs. F.B. Adkins and sister Miss Harriet Dingess was calling on Misses Pearl and Cora Adkins of this place. Mr. and…

View On WordPress

#Andrew Adkins#Appalachia#Beatrice Adkins#Bessie Adkins#Bill Adkins#Bob Powers#Catherine Adkins#Cora Adkins#Cora Dingess#Curt Dempsey#Delphia Dingess#Fisher B. Adkins#genealogy#Harriet Dingess#Harts#Hendricks Brumfield#Herbert Adkins#history#Hollena Ferguson#Inez Adkins#Jessie Brumfield#Lewis Dempsey#Lincoln County#Logan#Logan Banner#Luther Dempsey#Man#Ora Dingess#Pearl Adkins#Ranger

0 notes

Text

open to: m/f connection: any BGM: Feeling In The Dark

it wasn’t exactly a pleasant supper for them, especially for him. even though they had to eat, he had a nice 12oz steak sitting in front of all him, all for him too. the thought of that sick fuck still screwed with his head. “...i can’t eat this shit.” hank huffs almost frustratingly. ten years he spent in the fbi, working from the basement and up. thinking that maybe spending countless hours and overtime working in an office next to herbert-fucking-scott was awful, this took the cake. even after he took a shower, two to be specific back in the motel, he was still too afraid to touch his own hands, let alone bring his face close to them. hank wasn’t going to put the food anywhere near his mouth even if it looked good. the smell, even if it wasn’t there, still psychologically fucked him. “y’know, what i think about that son of a bitch? scat should be a federal. felonly-fucking-crime. guy is already rotting for thirty years for killing betty adkins, but if i was senior chief— i’d give that son of a bitch two life sentences without appeal or parole for liking shit. like, how the fuck does someone like the smell of shit.” hank swallowed hard in disgust and forced a piece of steak into his mouth. “you got any fancy words for freaks like him?”

#indie rp#open rp#open starters#indie starters#j → (starter)#j → hank hawkins (interactions)#i lost my appetite... LOL#i spent too much time watching plumber videos and i am thoroughly disgusted

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLACK LIVES MATTER. NO JUSTICE NO PEACE.

white silence is VIOLENCE..

they are more than just a hashtag.

George Floyd Breonna Taylor Tamir Rice Michael Lorenzo Dean Eric Reason Christopher McCorvey Steven Day Christopher Whitfield Atatiana Jefferson Maurice Holly Jordan Michael Griffin Nicholas Walker Bennie Branch Byron Williams Arthur Walton Jr. Channara Tom Pheap Patricia Spivey Stephan Murray Ryan Twyman Dominique Clayton Isaiah Lewis Kevin Leroy Beasley Jr. Julius Graves Marcus McVae Marzues Scott Bishar Hassan Kevin Bruce Mason Mario Clark Jimmy Atchison D’ettrick Griffin George Robinson Andre Horton William Matthew Holmes Jesse Jesus Quinton Anthony Antonio Ford Mahlon Edward Summerrour Charles D. Roundtree Jr. Chinedu Valentine Okobi Charles David Robinson Antone G. Black Jr. Darrell Richards Botham Shem Jean James Leatherwood Devin Howell Joshua Wayne Harvey Christopher Alexander Okamato Cynthia Fields Rashaun Washington Herbert Gilbert Anthony Marcell Green Antwon Michael Rose II Robert Lawrence White Thomas Williams Marcus-David L. Peters Terrance Carlton Aries Clark Juan Markee Jones Danny Ray Thomas Stephon Clark Trey Ta’Quan Pringle Sr. Ronell Foster Corey Mobley Arthur McAfee Jr. Geraldine Townsend Warren Ragudo Thomas Yatsko Dennis Plowden Jean Pedro Pierre Keita O’Neil Lawrence Hawkins Calvin Toney Dewboy Lister Armando Frank Stephen Gayle Antonio Garcia Jr. Brian Easley Euree Lee Martin DeJuan Guillory Aaron Bailey Joshua Terrell Crawford Marc Brandon Davis Adam Trammell Jimmie Montel Sanders DeRicco Devante Holdon Mark Roshawn Adkins Tashii S. Brown Jordan Edwards Roderick Ronall Taylor Kenneth Johnson Christopher Wade Alteria Woods Sherida Davis Lorenzo Antoine Cruz Chance David Baker Raynard Burton Quanice Derrick Hayes Chad Robertson Jerome Keith Allen Nana Adomako Marquez Warren Deaundre Phillips Sabin Marcus Jones Darrian M. Barnhill JR Williams Muhammad Abdul Muhaymin Jamal Robbins Marlon Lewis Ritchie Lee Harbison Lamont Perry Bill Jackson Julian Dawkins Terry Laffitte Jermaine Darden Marlon Brown Kendra Diggs Deion Fludd Clifton Armstrong Fred Bradford Jr. Craig Demps Dason Peters Dylan Samuel-Peters Russell Lydell Smith Willie Lee Bingham Jr. Clinton Roebexar Allen Charles A. Baker Jr. Anthony Dwayne Harris Donovan Thomas Jayvis Benjamin Quintine Barksdale Cedrick Chatman Darrell Banks Xavier Tyrell Johnson Yolanda Thomas Roy Lee Richards Alfred Olango Tawon Boyd Terrence Crutcher Tyre King Levonia Riggins Kendrick Brown Donnell Thompson Jr. Dalvin Hollins Delrawn Small Sherman Evans Deravis Rogers Antwun Shumpert Ollie Lee Brooks Michael Eugene Wilson Jr. Vernell Bing Jr. Jessica Williams Arthur R. Williams Jr. Lionel Gibson Charlin Charles Kevin Hicks Dominique Silva Robert Dentmond India M. Beaty Torrey Lamar Robinson Peter Wiliam Gaines Arteair Porter Kionte DeShaun Spencer Christopher J. Davis Thomas Lane Paul Gaston Calin Devante Roquemore Dyzhawn L. Perkins David Joseph Wendell Celestine Jr. Antronie Scott Peter John Keith Childress Bettie Jones Kevin Matthews Michael Noel Leroy Browning Miguel Espinal Nathaniel Pickett Cornelius Brown Tiara Thomas Richard Perkins Jamar Clark Alonzo Smith Anthony Ashford Dominic Hutchinson Lamontez Jones Rayshaun Cole Paterson Brown Jr. Junior Prosper Keith Harrison McLeod Wayne Wheeler Lavante Biggs India Kager James Carney III Felix Kumi Mansur Bell-Bey Asshams Manley Christian Taylor Troy Robinson Brian Day Samuel Dubose Darrius Stewart Albert Davis Salvado Ellswood George Mann Freddie Blue Johnathon Sanders Victo Lorosa III Spencer McCain Kevin Bajoie Kris Jacksons Kevin Higgenbotham Ross Anthony Richard Gregory Davis D’Angelo Reyes Stallworth Dajuan Graham Brendon Glenn Reginald L. Moore Sr. David Felix William Chapman Norman Cooper Darrell Lawrence Brown Walter Scott Eric Courtney Harris Donald Ivy Phillip White Jason Moland Denzel Brown Brandon Jones Askari Roberts Bobby Gross Terrance Moxley Anthony Hill Tony Terrell Robinson Naeschylus Vinzant Charly Leundeu Keunang DeOntre L. Dorsey Thomas Allen Jr. Calvin A. Reid Terry Price and countless of hundreds of others have lost their lives to systemic racism and police brutality in the united states. THIS MUST END. “normal” shouldn’t be citizens afraid of those charged to protect them. “normal” shouldn’t be weapons banned in wars used on peaceful civilians. “normal” shouldn’t include the continued abuse of those who are treated as less than by the system. WE HAVE THE POWER TO INACT CHANGE. MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD AGAINST RACISM AND POLICE BRUTALITY.

#whitesilenceisviolence#nojusticenopeace#theyaremorethanahastag#welcometotheshipwreck#letsgetwrecked#saytheirnames

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Together Alone’ - Heres my contribution to the 14th Annual Blab! show at Copro Gallery. Its a piece from my ongoing Dark Kingdom series that im working on via my Patreon page. ‘Together Alone’ is a 10x10″ hand embellished one off, mounted on board, varnished, framed and carries the Dark Kingdom Seal on the reverse. If youre interested in purchasing please contact the gallery via [email protected]

Heres the show info:

Copro Gallery Presents: THE 14TH ANNUAL BLAB SHOW CURATED BY: Monte Beauchamp

Exhibition Dates: September 07 – September 28, 2019

Opening Reception: Saturday, September 07, 2019 – 8:00-11:30pm

Copro Gallery Bergamot Arts Complex, 2525 Michigan Ave T5, Santa Monica, CA 90404 Tel: 310-829-2156

OVER 70 EXHIBITING ARTISTS: Ana Bagayan, Adrian Cox, Alex Graham, Andrew Hem, Annie Owens, Adam Wallacavage, Bennett Slater, Bill Mayer, Blair Dawson, Brandi Milne, Bruno Pontiroli, Buck Shanty, Cathie Bleck, Chris Mars, Christopher Buzelli, Clare Rosean, Craig LaRotonda, Danny Galieote, Deirdre Sulliavn-Beeman, Eduardo Samiento, Erik Mark Sandberg, Femke Hiemstra, Gabi de la Merced, Gary Guttman, George Hansen, Greg Clarke, Gregory Herbert, Horatio Quiroz, Jana Brike, Jill McVarish, Joe Vaux, John Brophy, John Kurtz, Jolene Lai, Jon Ching, Jon Jaylo, Jon MacNair, Julie Murphy, Leegan K, Lola Gil, Lucia Heffernan, Luke Cheuh, Mab Graves, Marc Burckhardt, Madeline von Foerster, Mari Shimizu, Matt Dangler, Matt Duffin, Matthew Schommer, Michael Glascott, Miranda Meeks, Miso, Naoto Hattori, Nouar, Olga Esther, Olivia De Berardinis, Owen Smith, Patricia Kirk, Rachel Bridge, Ray Caesar, Rich Adkins, Renee French, Ross Jaylo, Ryan Heshka, Scott Listfield, Scott Mills, Tim O'Brien, Tom Bagshaw, Tracy Black, Travis Lampe, and Victor Castillo.

PREVIEW LINK TO THE SHOW: http://www.copronason.com/blab19/

For purchase inquiries and more details about any of the works, contact Gary Pressman, Gallery Director, at [email protected] or call: 310-829-2156.

281 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Down the stretch they come! No, it’s not the Kentucky Derby — today, Kentuckians will vote for governor in their party primaries. Incumbent Gov. Matt Bevin will likely win renomination in the Republican contest despite being incredibly unpopular. But Democrats have a competitive three-way race between state House Minority Leader Rocky Adkins, state Attorney General Andy Beshear and former state auditor Adam Edelen. Beshear appears to be in the lead, but it’s unclear how big that lead really is and whether a Democrat can even still win a general election in a state that is now so deeply red.

Until Kentucky’s 2015 gubernatorial race, Democrats held most major statewide offices, and the GOP had won the governorship only once in the past 44 years. But Bevin won handily in 2015, and in 2016 Republicans captured the state house for the first time since the 1920s, giving them full control of state government.1 Thus, state politics now more closely align with Kentucky’s preferences in national races — the GOP presidential nominee has won Kentucky by at least 15 percentage points going back to 2000, and in 2016, President Trump won the state by 30 points.

All the same, Bevin (assuming he wins tonight) may still face a tough re-election fight next November. And that’s because he’s currently the most unpopular governor in the country, based on Morning Consult’s approval data for the first quarter of 2019.2 As you can see in the chart below, Bevin’s disapproval rating has been above 50 percent since the second quarter of 2018, which might have to do with his repeated run-ins with teachers, public sector unions and even his own party.

In April 2018, for example, Bevin vetoed legislation that raised taxes to expand public education spending only to have the Republican-controlled legislature override his veto while teachers rallied outside of the state capitol. He’s also made controversial comments, like when he said school closures allowing teachers to rally at the capitol may have caused children to be “sexually assaulted” or “physically harmed” because they couldn’t attend school.

Bevin’s approval numbers are even worse when you consider just how Republican-leaning Kentucky is. He had the worst approval rating of any governor relative to his state’s partisan lean,3 according to my colleague Nathaniel Rakich’s “Popularity Above Replacement Governor” rankings.

The latest ‘Popularity Above Replacement Governor’ scores

Governors’ net approval ratings for the first three months of 2019 relative to the partisan leans* of their states

Governor State Name Party Net Approval state Partisan Lean PARG KY Matt Bevin R -19 R+23 -42 RI Gina Raimondo D -11 D+26 -37 HI David Ige D +11 D+36 -25 WV Jim Justice R +14 R+30 -16 CT Ned Lamont D -4 D+11 -15 SD Kristi Noem R +18 R+31 -13 NY Andrew Cuomo D +9 D+22 -13 OR Kate Brown D -3 D+9 -12 CA Gavin Newsom D +12 D+24 -12 OK Kevin Stitt R +26 R+34 -8 UT Gary Herbert R +25 R+31 -6 NJ Phil Murphy D +8 D+13 -5 WY Mark Gordon R +43 R+47 -4 AK Mike Dunleavy R +12 R+15 -3 IL JB Pritzker D +11 D+13 -2 NE Pete Ricketts R +22 R+24 -2 IA Kim Reynolds R +6 R+6 0 ID Brad Little R +36 R+35 +1 NM Michelle Lujan Grisham D +8 D+7 +1 ND Doug Burgum R +34 R+33 +1 WA Jay Inslee D +15 D+12 +3 VA Ralph Northam D +5 EVEN +5 MO Mike Parson R +26 R+19 +7 IN Eric Holcomb R +27 R+18 +9 AR Asa Hutchinson R +34 R+24 +10 AZ Doug Ducey R +20 R+9 +11 OH Mike DeWine R +18 R+7 +11 DE John Carney D +26 D+14 +12 TN Bill Lee R +40 R+28 +12 MS Phil Bryant R +27 R+15 +12 GA Brian Kemp R +25 R+12 +13 ME Janet Mills D +20 D+5 +15 AL Kay Ivey R +44 R+27 +17 TX Greg Abbott R +34 R+17 +17 SC Henry McMaster R +34 R+17 +17 CO Jared Polis D +18 D+1 +17 MN Tim Walz D +21 D+2 +19 MI Gretchen Whitmer D +20 D+1 +19 NV Steve Sisolak D +19 R+1 +20 WI Tony Evers D +20 R+1 +21 PA Tom Wolf D +21 R+1 +22 NC Roy Cooper D +22 R+5 +27 FL Ron DeSantis R +34 R+5 +29 LA John Bel Edwards D +15 R+17 +32 NH Chris Sununu R +41 R+2 +39 MT Steve Bullock D +26 R+18 +44 KS Laura Kelly D +24 R+23 +47 VT Phil Scott R +32 D+24 +56 MD Larry Hogan R +57 D+23 +80 MA Charlie Baker R +59 D+29 +88

A Democratic governor with a net approval of +2 in an R+7 state has a PARG of +9 (2+7 = 9). If the same state had a Republican governor with the same approval rating, the PARG would be -5 (2-7= -5).

Shaded rows denote governors whose seats are up in 2019 or 2020, excluding those governors who are not seeking reelection.

* Partisan lean is the average difference between how a state votes and how the country votes overall, with 2016 presidential election results weighted at 50 percent, 2012 presidential election results weighted at 25 percent and results from elections for the state legislature weighted at 25 percent. The partisan leans here were calculated before the 2018 elections; we haven’t calculated FiveThirtyEight partisan leans that incorporate the midterm results yet.

Sources: Morning Consult, media reports

A big part of Bevin’s problem is that he’s struggling with his base. Morning Consult found in that poll that just 50 percent of Republicans approved of him while 37 percent disapproved. Compare that to the 86 percent of Kentucky Republicans who approved of Trump, and it’s understandable that Bevin is now trying to tie himself to the president, hoping to boost his numbers.

One bit of positive news for Bevin is that he avoided a high-profile primary challenge when U.S. Rep. James Comer — who Bevin beat by just 83 votes for the GOP nomination in 2015 — decided not to run. However, Bevin didn’t escape a primary challenger altogether. State Rep. Robert Goforth is running against him and even loaned his campaign $750,000 (as of early May, Bevin had raised a little over $1 million). But Goforth doesn’t seem to pose a serious risk to Bevin, at least not according to the scant polling we have: A survey from earlier in May from the GOP pollster Cygnal found Bevin leading Goforth 56 percent to 18 percent. Still, 32 percent of likely GOP primary voters said they had an unfavorable view of Bevin in that poll, so Goforth’s share of the primary vote on Tuesday could be an indicator of how strong or weak Bevin is among the Republican faithful.

But today’s main event is the Democratic race. The front-runner is Andy Beshear, the first-term attorney general and political scion whose father Steve preceded Bevin as governor. The younger Beshear squeaked out a narrow 0.2-point victory in 2015, with Bevin winning by 9 points at the top of the ballot. Since they took office, the two have been at loggerheads over many issues, including education, health care and pensions. These fights are one of Beshear’s main selling points in the Democratic primary, but Adam Edelen is running to Beshear’s left, hoping his support for abortion rights, decriminalizing marijuana and renewable energy will attract Democratic voters. And on Saturday, the state’s largest newspaper, the Courier-Journal, endorsed Edelen.

Edelen, the former state auditor, has also been on the offensive, attacking Beshear for his connection to a former aide who was convicted of bribery (however, there is no evidence Beshear knew about these activities). Edelen’s upstart campaign has also been aided by an influx of cash from his wealthy running mate, Gill Holland, and Better Future PAC, an outside group backing Edelen (primarily funded by Holland’s mother-in-law).

Meanwhile, state House Minority Leader Rocky Adkins is running to the right of Beshear and Edelen on social issues, claiming that his anti-abortion views and support for coal are more likely to appeal to the rural parts of the state where Democrats have been decimated in recent years.

Beshear currently seems to be ahead, but the only data we have are competing internal polls. Additionally, the two most recent surveys are from mid-April, so it’s hard to know if things have changed substantially in the past month. For what it’s worth, Edelen’s campaign found Beshear in first with 43 percent of the vote, Edelen in second with 23 percent and Adkins in third with 22 percent. Meanwhile, Beshear’s internal poll put him at 44 percent compared to 17 percent for Adkins and 16 percent for Edelen. So Beshear appears to be the polling front-runner, but a win by Edelen or Adkins shouldn’t be ruled out; internal polls are notoriously unreliable, the polling we do have is old and three-way races can be incredibly fluid.

Looking ahead to the general election in November, election handicappers view Kentucky as a toss-up or leaning in the GOP’s direction. Still, it’s possible a Democrat could take back the governor’s mansion. It’s early, but the pollster Mason-Dixon found Beshear up 48 percent to 40 percent in a Bevin-Beshear matchup in December. So if Bevin remains as unpopular as he is now, there could be an opening. Then again, the Bluegrass State’s politics are pretty darn red.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Earth Station One Podcast - Dune Part 1 Movie Review

New Post has been published on https://esonetwork.com/the-earth-station-one-podcast-dune-part-1-movie-review/

The Earth Station One Podcast - Dune Part 1 Movie Review

Mike and Mike celebrate 600 episodes of Earth Station One by doing what they do best – have a fun geeky discussion with some great folks. Alex, Ashley, and Chip Johnson take part in a spicy review of the third attempt to bring Frank Herbert’s 1965 epic story to life. Plus, Royce Adkins finds no safe harbor in the Geek Seat. All this, along with Angela’s A Geek Girl’s Take, Michelle’s Iconic Rock Moment, Creative Outlet with Gough from Beernuts Productions, and Shout Outs!

We want to hear from you! Feedback is always welcome. Please write to us at [email protected] and subscribe and rate the show on Apple Podcast, Stitcher Radio, Google Play, Spotify, Pandora, Amazo Music, or wherever fine podcasts are found.

Table of Contents 0:00:00 Show Open / Film Maker and Comic Creator Royce Adkins Takes on the Geek Seat 0:39:31 Michelle’s Iconic Rock Moment 0:41:26 Dune Part 1 Movie Review 1:34:38 Creative Outlet w/ Gough of Beer Nuts Productions 1:43:02 A Geek Girl’s Take 1:44:33 Show Close

Links Earth Station One on Apple Podcasts Earth Station One on Stitcher Radio Earth Station One on Spotify Past Episodes of The Earth Station One Podcast The ESO Network Patreon The New ESO Network TeePublic Store ESO Network Patreon Angela’s A Geek Girl’s Take Ashley’s Box Office Buzz Michelle’s Iconic Rock Talk Show The Earth Station One Website NSC Live TV Tifosi Optical Ashley Pauls’ Dune Movie Review Stone Harbor Comics Beernuts Productions Yeah We Went There

Promos Tifosi Optics Double Edge / Double Bill NSC Live TV The ESO Network Patreon

If you would like to leave feedback or a comment on the show please feel free to email us at [email protected]

#beer nuts productions#Dune#dune movie review#Earth Station One#Earth Station One Podcast#ESO Network#geek podcast#Geek Talk

0 notes

Link

The newest episode of Locust Radio is now live.

We have guests! Artists Omnia Sol (whose music you will recognize as a regular feature at Locust Radio) and Adam Ray Adkins (a.k.a. Dirt: Son of Earth and co-host of the Acid Left videocast) come on the show to talk their own work, the impact of acid communism, and what it means to build a 21st century psychedelic reason. Each of our guests shares some of their poetry and music, and we hear some more of Tish’s ongoing novel Sound. Plus, just in time for the holidays, we get to hear what actually happened to George Bailey that night in Pottersville, after the Angel of History intervened...

For the second half of our show, available to SUBSCRIBERS ONLY, Markley and Adkins share more of their work. We also talk a bit more about narrative conceptualism, and why the Peoria Cookie Monster mural is so much more interesting than those stupid fucking monoliths that have been appearing lately. If you want to hear this portion, and haven’t subscribed yet, do so now.

Check out more of Omnia Sol’s work on YouTube and Instagram and support their work on Patreon. Check out Adam Ray Adkins’ work at his YouTube, his Instagram, and listen to the Acid Left.

Some additional material we reference in this episode: “Acid Communism,” unfinished introduction to Mark Fisher’s book of the same name, as it appears in K-Punk; “An Essay On Liberation,” by Herbert Marcuse; Postcapitalist Desire, by Mark Fisher, with an introduction by Matt Colquhoun

Locust Radio is produced by Drew Franzblau. It is hosted by Alexander Billet, Tish Markley and Adam Turl. Music is by Omnia Sol.

Snow footstep sound effects by ("Footsteps, Snow, A.wav" and "Running, Snow, A.wav") by InspectorJ of Freesound.org

0 notes

Text

Calvert County Maryland Circuit Court

Contents

Requirements maryland title 2

Marriage. marriage license fees

Programs. family services

In Injury Suit Against Baltimore Hotel Corporation, BMA Lawyer Jeffrey Quinn Obtains $584,000 Jury Verdict Following a jury trial in the Circuit Court for Baltimore City against The Baltimore Hotel Corporation, Bekman, Marder & Adkins, LLC lawyer, Jeff…

UPDATE: The county announced Monday morning that government offices will be closed rather than delayed. See more details below. UPDATE: The Calvert County … a press release states. • Circuit and dis…

Calvert County Circuit Court Courthouse 175 Main Street Prince Frederick, MD 20678 e-mail: [email protected]. Do NOT send pleadings, papers or …

Bruce, a master for domestic and juvenile cases in Calvert County Circuit Court since 1995, to the District Court … Caroom, 45, a 1978 graduate of the University of Maryland School of Law, is a form…

The Court of Appeals of Maryland is the supreme court of the U.S. state of Maryland.The court, which is composed of one chief judge and six associate judges, meets in the Robert C. Murphy Courts of Appeal Building in the state capital, Annapolis.The term of the Court …

State of Maryland Marriage License requirements maryland title 2. marriage. marriage license fees: $35 – $85, varying by county Both parties must be over 18 years of age. Under age 18.

Calvert County Maryland Most Wanted Mechanicsville He was arrested on March 02, 2019 and processed into the calvert county detention … Savoy is wanted on numerous outstanding warrants, to include Handgun Calvert County Maryland Elections Dameron A pro-Trump billboard warning “liberals” to arm themselves if they attempt to impeach the president will be taken down from its roadside position in Calvert

About Sarah. Sarah F. Lacey was elected in November 2018 to represent District One on the County Council. Ms. Lacey grew up in several states across the country due …

Parks In Calvert County Maryland Morganza Search up-to-date mls listings of homes for sale in Southern Maryland – Charles County, Saint Mary’s County and Calvert County, MD. Search Maryland real estate,

175 Main Street Prince Frederick, MD 20678; Phone: 410-535-1600; Open: 8:30 AM — 4:30 PM. Clerk’s Office. Circuit Court for Calvert County, MD …

Calvert County Maryland Map Tall Timbers Search 7 homes for sale in Tall Timbers, MD at a median list price of $630K. View photos, open house info, and property details for

Larry Deffenbaugh, the former Calvert County cemetery owner accused of stealing burial funds from hundreds of county residents, is at least $10,000 behind on child support payments, according to filin…

A circuit court judge in Maryland is accused by a former staffer of sexual … all of the judges in the 7th Judicial Circuit–which includes Charles County, St. Mary’s County, Calvert County and Princ…

Maryland Law states that a personal representative “…is under general duty to settle and distribute the estate of the decedent in accordance with the terms of the will and the estates of decedents law as expeditiously and with little sacrifice of value as is reasonable under the circumstances.”

Calvert County Maryland Jobs Callaway Welcome to the Bureau of Land Management(BLM), General Land Office (GLO) Records Automation web site. We provide live access to Federal land conveyance records for

Family Services Programs & Self-Help Centers Family Services programs. family services Programs are in every Circuit Court. They offer services for families involved in family law cases.

to the Calvert County Courthouse and the Office of Clerk of the Circuit Court. Rich in the tradition and history of Maryland, the Office of the Clerk of the Circuit …

Calvert County Maryland School Closings Piney Point Piney Point had previously … Patuxent River. Maryland Gov. Herbert O’Conor, a Democrat, promised his cooperation in providing state infrastructure for the project. The base

More than a year after the pair filed their suit, retired Maryland Court of Special Appeals Judge James P. Salmon, sitting in Calvert County Circuit Court, handed down the decision Dec. 22 in response …

via Check This Out More Resources

0 notes

Text

Labor Day History – 82 Significant Years

Our Labor for Love

For many, Labor Day signifies the end of summer and a chance to unwind during a long weekend. From relaxing by the pool to hosting a family barbecue, this extra day off allows people to catch their breath before the busy weeks ahead. However, despite how we may spend this holiday, Labor Day stands for so much more than just having good times with amazing people.

The history of Labor Day began during the Industrial Revolution when oppressive working environments were prevalent across the nation. At the time, honest, hard-working people endured harsh work conditions like 16-hour workdays and incredibly low wages. Fortunately, since then, laws have been put in place to protect workers from similar mistreatment. Today, Labor Day stands as a symbol of that history and a reminder to honor genuine, hard-working people in our community.

Celebrating Labor Day means celebrating unconditional labors of love. Whether your labor of love is protecting your community or raising your children, there is no specific definition that controls what a labor of love looks like. That’s the beauty of it!

A labor of love could be as simple as helping your neighbor across the street or as thought-out as enlisting in the Army to serve your country. At the end of the day, it all comes back to helping out the people you love most.

Iowa Legendary Rye’s Labor for Love

In most part, this labor day signifies a re-count of what our grandmother Lorine Sextro went through during prohibition and her labor to keep her family afloat by producing our great tasting rye.

Although at that time it was illegal to produce those spirits she went above and beyond to keep and maintain her family, farm, and homestead while letting others stay with her keep those she loved and family healthy with food and a warm place to stay during a time when our great nation was building its infrastructure.

We cannot forget our history and the labors of love that paved the way for our future.

Play Video

The Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage this Labor Day and our Labor of Love.

Labor Day Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938:

When he felt the time was ripe, President Roosevelt asked Secretary of Labor Perkins, ‘What happened to that nice unconstitutional bill you had tucked away?’

On Saturday, June 25, 1938, to avoid pocket vetoes 9 days after Congress had adjourned, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed 121 bills. Among these bills was a landmark law in the Nation’s social and economic development — Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA). Against a history of judicial opposition, the depression-born FLSA had survived, not unscathed, more than a year of Congressional altercation. In its final form, the act applied to industries whose combined employment represented only about one-fifth of the labor force. In these industries, it banned oppressive child labor and set the minimum hourly wage at 25 cents, and the maximum workweek at 44 hours.1

Forty years later, a distinguished news commentator asked incredulously: “My God! 25 cents an hour! Why all the fuss?” President Roosevelt expressed a similar sentiment in a “fireside chat” the night before the signing. He warned: “Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day, …tell you…that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry.”2 In light of the social legislation of 1978, Americans today may be astonished that; a law, with such moderate standards, could have been thought so revolutionary.

Courting disaster

The Supreme Court had been one of the major obstacles to wage-hour and child-labor laws. Among notable cases is the 1918 case of Hammer v. Dagenhart in which the Court by one vote held unconstitutional a Federal child-labor law. Similarly in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital in 1923, the Court by a narrow margin voided the District of Columbia law that set minimum wages for women. During the 1930s, the Court’s action on social legislation was even more devastating.3

New Deal promise. In 1933, under the “New Deal” program, Roosevelt’s advisers developed a National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA).4 The act suspended antitrust laws so that industries could enforce fair-trade codes resulting in less competition and higher wages. On signing the bill, the President stated: “History will probably record the National Industrial Recovery Act as the most important and far-reaching legislation ever enacted by the American Congress.” The law was popular, and one family in Darby, Penn., christened a newborn daughter Nira to honor it.5

As an early step of the NRA, Roosevelt promulgated a President’s Reemployment Agreement “to raise wages, create employment, and thus restore business.” Employers signed more than 2.3 million agreements, covering 16.3 million employees. Signers agreed to a workweek between 35 and 40 hours and a minimum wage of $12 to $15 a week and undertook, with some exceptions, not to employ youths under 16 years of age. Employers who signed the agreement displayed a “badge of honor,” a blue eagle over the motto “We do our part.” Patriotic Americans were expected to buy only from “Blue Eagle” business concerns.6

In the meantime, various industries developed more complete codes. The Cotton Textile Code was the first of these and one of the most important. It provided for a 40-hour workweek, set a minimum weekly wage of $13 in the North and $12 in the South, and abolished child labor. The President said this code made him “happier than any other one thing…since I have come to Washington, for the code abolished child labor in the textile industry.” He added: “After years of fruitless effort and discussion, this ancient atrocity went out in a day.”7

A crushing blow. On “Black Monday,” May 27, 1935, the Supreme Court disarmed the NRA as the major depression-fighting weapon of the New Deal. The 1935 case of Schechter Corp. v. United States tested the constitutionality of the NRA by questioning a code to improve the sordid conditions under which chickens were slaughtered and sold to retail kosher butchers.8 All nine justices agreed that the act was an unconstitutional delegation of government power to private interests. Even the liberal Benjamin Cardozo thought it was “delegation running riot.” Though the “sick chicken” decision seems an absurd case upon which to decide the fate of so sweeping a policy, it invalidated not only the restrictive trade practices set by the NRA-authorized codes but the codes’ progressive labor provisions as well.9

As if to head off further attempts at labor reform, the Supreme Court, in a series of decisions, invalidated both State and Federal labor laws. Most notorious was the 1936 case of Joseph Tipaldo.10The manager of a Brooklyn, N.Y., laundry, Tipaldo had been paying nine laundry women only $10 a week, in violation of the New York State minimum wage law. When forced to pay his workers $14.88, Tipaldo coerced them to kick back the difference. When Tipaldo was jailed on charges of violating the State law, forgery, and conspiracy, his lawyers sought a writ of habeas corpus on grounds the New York law was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court, by a 5-to-4 majority, voided the law as a violation of the liberty of contract.11

The Tipaldo decision was among the most unpopular ever rendered by the Supreme Court. Even bitter foes of President Roosevelt and the New Deal criticized the Court. Ex-President Herbert Hoover said the Court had gone to extremes. Conservative Republican Congressman Hamilton Fish called it a “new Dred Scott decision” condemning 3 million women and children to economic slavery.12

A switch in time. Wage-hour legislation was a campaign issue in the 1936 Presidential race. The Democratic platform called for higher labor standards, and, in his campaign, Roosevelt promised to seek some constitutional way of protecting workers. He tried to pave the way for such legislation in his speeches and news conferences in which he spoke of the breakdown of child labor provisions, minimum wages, and maximum hour standards after the demise of the NRA codes.

When Roosevelt won the 1936 election by 523 electoral votes to 8, he interpreted his landslide victory as support for the New Deal and was determined to overcome the obstacle of Supreme Court opposition as soon as possible. In February 1937, he struck back at the “nine old men” of the Bench: He proposed to “pack” the Court by adding up to six extra judges, one for each judge who did not retire at age 70. Roosevelt further voiced his disappointment with the Court at the victory dinner for his second inauguration, saying if the “three-horse team [of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches] pulls as one, the field will be plowed,” but that the field will not be plowed if one horse lies down in the traces or plunges off in another direction.”13

However, Roosevelt’s metaphorical maverick fell in step. On “White Monday,” March 29, 1937, the Court reversed its course when it decided the case of West Coast Hotel Company v. Parrish.14 Elsie Parrish, a former chambermaid at the Cascadian Hotel in Wenatchee, Wash., sued for $216.19 in back wages, charging that the hotel had paid her less than the State minimum wage. In an unexpected turn-around, Justice Owen Roberts voted with the four-man liberal minority to uphold the Washington minimum wage law.

As other close decisions continued to validate social and economic legislation, support for Roosevelt’s Court “reorganization” faded. Meanwhile, Justice Roberts felt called upon to deny that he had switched sides to ward off Roosevelt’s court-packing plan. He claimed valid legal distinctions between the Tipaldo case and the Parrish case. Nevertheless, many historians subscribe to the contemporary view of Robert’s vote, that “a switch in time saved nine.”15

A young worker’s plea

While President Franklin Roosevelt was in Bedford, Mass., campaigning for reelection, a young girl tried to pass him an envelope. But a policeman threw her back into the crowd. Roosevelt told an aide, “Get the note from the girl.” Her note read,

I wish you could do something to help us, girls…We have been working in a sewing factory,… and up to a few months ago, we were getting our minimum pay of $11 a week… Today the 200 of us girls have been cut down to $4 and $5 and $6 a week.

To a reporter’s question, the President replied, “Something has to be done about the elimination of child labor and long hours and starvation wages.”

-FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT Public Papers and Addresses, Vol. V New York, Random House, 1936), pp. 624-25.

Back to the drawing board

Justice Roberts’ “Big Switch” is an important event in American legal history. It is also a turning point in American social history, for it marked a new legal attitude toward labor standards. To be sure, validating a single State law was a far cry from upholding general Federal legislation, but the Parrish decision encouraged advocates of fair labor standards to work all the harder to develop a bill that might be upheld by the Supreme Court.

An ardent advocate. No top government official worked more ardently to develop legislation to help underpaid workers and exploited child laborers than Secretary Frances Perkins. Almost all her working life, Perkins fought for pro-labor legislation. To avoid the sometime pitfall of judicial review, she consulted legal experts in forming the legislation. Her autobiographical account of her relations with President Roosevelt is filled with the names of lawyers with whom she discussed legislation: Felix Frankfurter, Thomas Corcoran, Gerard Reilly, Benjamin Cohen, Charles Wyzanski, and many others both within and outside Government.

When, in 1933, President Roosevelt asked Frances Perkins to become Secretary of Labor, she told him that she would accept if she could advocate a law to put a floor under wages and a ceiling over hours of work and to abolish abuses of child labor. When Roosevelt heartily agreed, Perkins asked him, “Have you considered that to launch such a program… might be considered unconstitutional?” Roosevelt retorted, “Well, we can work out something when the time comes.”16

During the constitutional crisis over the NRA, Secretary Perkins asked lawyers at the Department of Labor to draw up two wage-hour and child-labor bills which might survive the Supreme Court review. She then told Roosevelt, “I have something up my sleeve….I’ve got two bills …locked in the lower left-hand drawer of my desk against an emergency.” Roosevelt laughed and said, “There’s New England caution for you… You’re pretty unconstitutional, aren’t you?”17

Earlier Government groundwork. One of the bills that Perkins had “locked” in the bottom drawer of her desk was used before the 1937 “Big Switch.” The bill proposed using the purchasing power of the Government as an instrument for improving labor standards. Under the bill, Government contractors would have to agree to pay the “prevailing wage” and meet other labor standards. The idea had been tried in World War I to woo worker support for the war. Then, President Hoover reincarnated the “prevailing wage” and fair standards criteria as conditions for bidding for the construction of public buildings. This act — the Davis-Bacon Act — in expanded form stands as a bulwark of labor standards in the construction industry.

Roosevelt and Perkins tried to make model employers of government contractors in all fields, not just construction. They were dismayed to find that, except in public construction, the Federal Government encouraged employers to exploit labor because the Government had to award every contract to the lowest bidder. In 1935, approximately 40 percent of government contractors, employing 1.5 million workers, cut wages below and stretched hours above the standards developed under the NRA.

The Roosevelt-Perkins remedial initiative resulted in the Public Contracts Act of 1936 (Walsh-Healey). The act required most government contractors to adopt an 8-hour day and a 40-hour week, to employ only those over 16 years of age if they were boys or 18 years of age if they were girls, and to pay a “prevailing minimum wage” to be determined by the Secretary of Labor. The bill had been hotly contested and much diluted before it passed Congress on June 30, 1936. Though limited to government supply contracts and weakened by amendments and court interpretations, the Walsh-Healey Public Contracts Act was hailed as a token of good faith by the Federal Government — that it intended to lead the way to better pay and working conditions.18

A broader bill is born

President Roosevelt had postponed action on a fair labor standards law because of his fight to “pack” the Court. After the “switch in time,” when he felt the time was ripe, he asked Frances Perkins, “What happened to that nice unconstitutional bill you tucked away?”

The bill — the second that Perkins had “tucked” away — was a general fair labor standards act. To cope with the danger of judicial review, Perkins’ lawyers had taken several constitutional approaches so that, if one or two legal principles were invalidated, the bill might still be accepted. The bill provided for minimum-wage boards which would determine, after public hearing and consideration of cost-of-living figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, whether wages in particular industries were below subsistence levels.

Perkins sent her draft to the White House where Thomas Corcoran and Benjamin Cohen, two trusted legal advisers of the President, with the Supreme Court in mind, added new provisions to the already lengthy measure. “Ben Cohen and I worked on the bill and the political effort behind it for nearly 4 years with Senator Black and Sidney Hillman,” Corcoran noted.19

An early form of the bill being readied for Congress affected only wages and hours. To that version, Roosevelt added a child-labor provision based on the political judgment that adding a clause banning goods in interstate commerce produced by children under 16 years of age would increase the chance of getting a wage-hour measure through both Houses because child-labor limitations were popular in Congress.20

Congress-round I

On May 24, 1937, President Roosevelt sent the bill to Congress with a message that America should be able to give “all our able-bodied working men and women a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.” He continued: “A self-supporting and self-respecting democracy can plead no justification for the existence of child labor, no economic reason for chiseling worker’s wages or stretching workers’ hours.” Though States had the right to set standards within their borders, he said, goods produced under “conditions that do not meet rudimentary standards of decency should be regarded as contraband and ought not to be allowed to pollute the channels of interstate trade.” He asked Congress to pass applicable legislation” at this session.”21

Senator Hugo Black of Alabama, a champion of a 30-hour workweek, agreed to sponsor the Administration bill on this subject in the Senate, while Representative William P. Connery of Massachusetts introduced corresponding legislation in the House. The Black-Connery bill had wide Public support, and its path seemed smoothed by arrangements for a joint hearing by the labor committees of both Houses.

Generally, the bill provided for a 40-cent-an-hour minimum wage, a 40-hour maximum workweek, and a minimum working age of 16 except in certain industries outside of mining and manufacturing. The bill also proposed a five-member labor standards board that could authorize still higher wages and shorter hours after review of certain cases.

Proponents of the bill stressed the need to fulfill the President’s promise to correct conditions under which “one-third of the population” were “ill-nourished, ill-clad, and ill-housed.” They pointed out that, in industries that produced products for interstate commerce, the bill would end oppressive child labor and “unnecessarily long hours which wear out part of the working population while they keep the rest from having work to do.” Shortening hours, they argued, would “create new jobs…for millions of our unskilled unemployed,” and minimum wages would “underpin the whole wage structure…at a point from which collective bargaining could take over.”22

Advocates of higher labor standards described the conditions of sweated labor. For example, a survey by the Labor Department’s Children’s Bureau of a cross-section of 449 children in several States showed nearly one-fourth of them working 60 hours or longer a week and only one-third working 40 hours or less a week. The median wage was slightly over $4 a week.23

One advocate, Commissioner of Labor Statistics Isador Lubin, explained to the joint Senate-House committee that during depressions the ability to overwork employees, rather than efficiency, determining business success. The economy, he reported, had deteriorated to the chaotic stage where employers with high standards were forced by cut-throat competition to exploit labor to survive. “The outstanding feature of the proposed legislation,” Lubin said, is that “it aims to establish by law a plane of competition far above that which could be maintained in the absence of government edict.”24

Opponents of the bill charged that, although the President might damn them as “economic royalists and sweaters of labor,” the Black-Connery bill was “a bad bill badly drawn” which would lead the country to a “tyrannical industrial dictatorship.” They said New Deal rhetoric, like “the smokescreen of the cuttlefish,” diverted attention from what amounted to socialist planning. Prosperity, they insisted, depended on the “genius” of American business, but how could business “find any time left to provide jobs if we are to persist in loading upon it these everlastingly multiplying governmental mandates and delivering it to the mercies of multiplying and hampering Federal bureaucracy?”25

Organized labor supported the bill but was split on how strong it should be. Some leaders, such as Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers Union and David Dubinsky of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union, supported a strong bill. When Southern congressmen asked for the setting of lower pay for their region, Dubinsky’s union suggested lower pay for Southern congressmen. But William Green of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and John L. Lewis of the Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO), on one of the rare occasions when they agreed, both favored a bill which would limit labor standards to low-paid and essentially unorganized workers. Based on some past experiences, many union leaders feared that a minimum wage might become a maximum and that wage boards would intervene in areas that they wanted to be reserved for labor-management negotiations. They were satisfied when the bill was amended to exclude work covered by collective bargaining.

The weakened bill passed the Senate July 31, 1937, by a vote of 56 to 28 and would have easily passed the House if it had been put to a vote. But a coalition of Republicans and conservative Democrats bottled it up in the House Rules Committee. After a long hot summer, Congress adjourned without House action on fair labor standards.26

Congress-round II

An angry President Roosevelt decided to press again for passage of the Black-Connery bill. Having lost popularity and split the Democratic Party in his battle to “pack” the Supreme Court, Roosevelt felt that attacking abuses of child labor and sweatshop wages and hours was a popular cause that might reunite the party. A wage-hour, child-labor law promised to be a happy marriage of high idealism and practical politics.

On October 12, 1937, Roosevelt called a special session of Congress to convene on November 15. The public interest, he said, required immediate Congressional action: “The exploitation of child labor and the undercutting of wages and the stretching of the hours of the poorest paid workers in periods of a business recession has a serious effect on buying power”.27

Despite White House and business pressure, the conservative alliance of Republicans and Southern Democrats that controlled the House Rules Committee refused to discharge the bill as it stood. Congresswoman Mary Norton of New Jersey, now chairing the House Labor Committee, made a valiant attempt to shake the bill loose”.28 Many representatives had told her that they agreed with the principles of the bill but that they objected to a five-man wage board with broad powers. Therefore, Norton told the House of Representatives that the Labor Committee would offer an amendment to change the administration of the bill from a five-man board to an administrator under the Department of Labor. Urging representatives to sign a petition to jar the bill out of committee, Norton appealed:

I now hope and urge that these Members will keep faith with me, as I have kept faith with them, and sign the petition . . . we are approaching Thanksgiving Day, . . . I do not see how any Member of this House can enjoy his Thanksgiving dinner tomorrow if he fails to put his name to that petition this afternoon.

Though Norton missed her Thanksgiving Day dead-line, by December 2, the bill’s supporters had rounded up enough signers to give the petition the 218 signatures necessary to bring the bill to a vote on the House floor.29

With victory within grasp, the bill became a battle-ground in the war raging between the AFL and the CIO. The AFL accused the Roosevelt Administration of favoring industrial over craft unions and opposed the wage-board determination of labor standards for specific industries. Accordingly, the AFL fought for a substitute bill with a flat 40-cent-an-hour minimum wage and a maximum 40-hour week.

In the ensuing confusion, shortly, before the Christmas holiday of 1937, the House by a vote of 218 to 198 unexpectedly sent the bill back to the Labor Committee.30 In her memoir of President Roosevelt, Frances Perkins wrote:

This was the first time that a major administration bill had been defeated on the floor of the House. The press took the view that this was the death knell of wage-hour legislation as well as a decisive blow to the President’s prestige.31

Roosevelt tries again

Again, Roosevelt returned to the fray. In his annual message to Congress on January 3, 1938, he said he was seeking “legislation to end starvation wages and intolerable hours.” He paid deference to the South by saying that “no reasonable person seeks a complete uniformity in wages.” He also made peace overtures to business by pointing out that he was forgoing “drastic” change, and he appeased organized labor, saying that “more desirable wages are and should continue to be the product of collective bargaining.”32

The day following Roosevelt’s message, Representative Lister Hill, a strong Roosevelt supporter, won an Alabama election primary for the Senate by an almost 2-to-1 majority over an anti-New Deal congressman. The victory was significant because much of the opposition to wage-hour laws came from Southern congressmen. In February, a national public opinion poll showed that 67 percent of the populace favored the wage-hour law, with even the South showing a substantial plurality of support for higher standards.33

Reworking the bill. In the meantime, the Department of Labor lawyers worked on a new bill. Privately, Roosevelt had told Perkins that the length and complexity of the bill caused some of its difficulties. “Can’t it be boiled down to two pages?” he asked. Lawyers trying to simplify the bill faced the problem that, although legal language makes legislation difficult to understand, bills written in simple English are often difficult for the courts to enforce. And because the wage-hour, the child-labor bill had been drafted with the Supreme Court in mind, Solicitor Labor Gerard Reilly could not meet the President’s two-page goal; however, he succeeded in cutting the bill from 40 to 10 pages.

In late January 1938, Reilly and Perkins brought the revision to President Roosevelt. He approved it, and the new bill went to Congress.34

Roosevelt and Perkins prepared for rugged opposition. Roosevelt put pressure on Congressmen who had ridden his coattails to election victory in 1936 and who then knifed New Deal legislation. Perkins added to her staff Rufus Pole, a young lawyer, to follow the bill through Congress. Pole worked resourcefully pinpointed the issues that bothered some Congressmen and identified a large number of Senators and Representatives who could be counted on to vote favorably.

Norton appointed Representative Robert Ramspeck of Georgia to head a subcommittee to bridge the gap between various proposals. The subcommittee’s efforts resulted in the Ramspeck compromise which Perkins felt “contained the bare essentials she could support.”35 The compromise retained the 40-cent minimum hourly wage and the 40-hour maximum workweek. It did not provide for an administrator as had the previous bill which had been voted back to the committee by the House. Instead, the compromise allowed for a five-member wage board which would be less powerful than those proposed by the Black-Connery bill.

Congress-the final round

The House Labor Committee voted down the Ramspeck compromise, but, by a 10-to-4 vote, approved an even more “barebones” bill presented by Norton. Her bill following the AFL proposal, provided for a 40-cent hourly minimum wage, replaced the wage boards proposed by the Ramspeck compromise with an administrator and advising commission, and allowed for procedures for an investigation into certain cases.36

A message from the voters. Again, the House Rules Committee (under Rep. John J. O’Conner of New York, whom Roosevelt called an “obstructionist” who “pickled” New Deal programs) prevented discussion of the bill on the House floor by a vote of 8 to 6.37 The President then put his prestige on the line. On April 30, 1938, for the sixth time since taking office, he communicated with Congress over wages and hours through a letter to Mrs. Norton. He said he had no right whatsoever as President to criticize the rules but suggested as an ex-legislator and as a friend that “the whole membership of the legislative body should be given full and free opportunity to discuss [exceptional measures] which are of undoubted national importance because they relate to major policies of Government and affect the lives of millions of people.” He avoided judgment of the bill but noted that the Rules Committee, by a narrow vote, had prevented 435 members from “discussing, amending, recommitting, defeating, or passing some kind of a bill.” He concluded: “I still hope that the House as a whole can vote on a wage and hour bill. …I hope that the democratic processes of legislation will continue.”38

Three days later, May 3, 1938, Congressman Claude Pepper won a resounding victory over anti-New Dealer J. Mark Wilcox in the Florida Senate primary. Wilcox had made New Deal programs the major issue and had labeled Pepper “Roosevelt rubber stamp.”

Nothing impresses Congressmen more than election returns. The January and May victories of New Deal advocated in the South brought home to Southern Congressmen the message of how their constituents felt about fair labor standards. A petition to discharge the bill from the Rules Committee was placed on the desk of the Speaker of the House on May 6, at noon. In 2 hours and 20 minutes, 218 members have signed it, and additional members were waiting in the aisles.39

Braving the floor battle. Proponents of the wage-hour, child-labor bill pressed the attack. They continued to point to “horror stories.” One Congressman quoted a magazine article entitled “All Work and No Pay” which told how, in a company that paid wages in scrip for use in the company store, pay envelopes contained nothing for a full week’s work after the deduction of store fees

The most bitter controversy raged over labor standards in the South. “There are in the State of Georgia,” one Indiana Congressman declaimed, “canning factories working … women 10 hours a day for $4.50 a week. Can the canning factories of Indiana and Connecticut of New York continue to exist and meet such competitive labor costs?”40 Southern Congressmen, in turn, challenged the Northern “monopolists” who hypocritically “loll on their tongues” words like “slave labor” and “sweat-shops” and support bills that sentenced the Southern industry to death. Some Southern employers told the Department of Labor that they could not live with a 25-cent-an-hour minimum wage. They would have to fire all their people, they said. Adapting a biblical quotation, Representative John McClellan of Arkansas rhetorically asked, “What profiteth the laborer of the South if he gains the enactment of a wage and hour law — 40 cents per hour and 40 hours per week — if he then loses the opportunity to work?”41

Partly because of Southern protests, provisions of the act were altered so that the minimum wage was reduced to 25 cents an hour for the first year of the act. Southerners gained additional concessions, such as a requirement that wage administrators consider lower costs of living and higher freight rates in the South before recommending wages above the minimum.

Though the revised bill had reduced substantially the administrative machinery provided for in earlier drafts, several Congressmen singled out Secretary Perkins for personal attack. One Perkins detractor noted that, although Congress had “overwhelmingly rebelled” against delegation of power,

We delegate to Madam Perkins the authority and power to ‘issue an order declaring such an industry to be an industry affecting commerce.’ Now section 9 is …one of the ‘snooping’ sections of the bill. Imagine the feeling of the merchant or the industry up in your district when a ‘designated representative’…of Mme. Perkins’ enter and inspect such places and such records’…I know no previous law going quite so far.42

A resulting compromise modified the authority of the administrator in the Department of Labor.

The bill was voted upon May 24, 1938, with a 314-to-97 majority. After the House had passed the bill, the Senate-House Conference Committee made still more changes to reconcile differences. During the legislative battles over fair labor standards, members of Congress had proposed 72 amendments. Almost every change sought exemptions, narrowed coverage, lowered standards, weakened administration, limited investigation, or in some other way worked to weaken the bill.

The surviving proposal as approved by the conference committee finally passed the House on June 13, 1938, by a vote of 291 to 89. Shortly thereafter, the Senate approved it without a record of the votes. Congress then sent the bill to the President. On June 25, 1938, the President signed the Fair Labor Standards Act to become effective on October 24, 1938.43

Jonathan Grossman was the Historian for the U.S. Department of Labor. Henry Guzda assisted. This article originally appeared in the Monthly Labor Review of June 1978. The final section, titled “The act as law” and containing dated material, has been omitted in the electronic version.

NOTES

1. The New York Times, June 27, 28, 1938; Harry S. Kantor, “Two Decades of the Fair Labor Standards Act,” Monthly Labor Review, October 1958, pp. 1097-98.

2. Franklin Roosevelt, Public Papers and Address, Vol. VII (New York, Random House, 1937), p.392.

3. Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 251 (1918); Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, 262 U.S. 525 (1923).

4. The proper initials for the Law are NIRA. The initials for the National Recovery Administration were created by the act as NRA. Following common practice, the initials NRA are used here for both the law and the administration.

5. Roosevelt, Public Papers, II (June 16, 1933), p.246.

6. Roosevelt, Public Papers, II (July 24 and 27, 1933), pp. 301, 308-12.

7. Roosevelt, Public Papers, II (July 9 and 24, 1933), pp. 275, 99; Frances Perkins, The Roosevelt I Knew (New York, Viking Press, 1946); pp. 204-08.

8. Schechter Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495(1935).

9. Arthur M. Schlesinger, The Age of Roosevelt (Boston, Mass., Houghton-Mifflin Co., 1960), pp. 277-83; Roosevelt, Public Papers, IV (May 29, 1935), pp. 198-221; John W. Chambers, “The Big Switch: Justice Roberts and the Minimum-Wage Cases,” Labor History, Vol. X, Winter 1969, pp.49-52.

10. Morehead v. Tipaldo, 298 U.S. 587 (1936).

11. Ironically, like the four Schechter brothers in the NRA case who went broke, Tipaldo also suffered financially. “My customers wouldn’t give my drivers their wash,” he lamented. Columnist Heywood Broun quipped. “Those who live by the chisel will die under the hammer.” Chambers, “Big Switch,” p. 57.

12. Chambers, “Big Switch,” pp. 54-58.

13. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VI (Feb. 5, 1937), pp. 51-59; VI (Mar. 4, 1937), p. 116; George Martin, Madam Secretary Frances Perkins(Boston Mass., Houghton-Mifflin Co., 1976), pp. 388-90.

14. West Coast Hotel Company v. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379 (1937).

15. Chambers, “Big Switch,” pp. 44, 73; Robert P. Ingalls, “New York and the Minimum-Wage Movement, 1933-1937,” Labor History, Vol. XV, Spring 1974, pp. 191-97.

16. Perkins, Roosevelt, p. 152

17. Perkins, Roosevelt, pp. 248-49, 252-53; Roosevelt, Public Papers, V(Jan.` 3, 1936), p. 15; Jonathan Grossman with Gerard D. Reilly, Solicitor of Labor, Oct. 22, 1965.

18. 25th Annual Report, Fiscal Year 1937 (U.S. Department of Labor), pp. 34-35; Herbert C. Morton, Public Contracts and Private Wages: Experience Under the Walsh-Healey Act(Washington, D.C., The Brookings Institution, 1965), pp. 7-10; The Department of Labor (New York, Praeger Publishers, 1973), pp. 19-20, 211-13.

19. Letter from Thomas Corcoran to Jonathan Grossman, Ap. 10, 1978.

20. Perkins, Roosevelt, pp. 254-57; Roosevelt, Public Papers, V(Jan. 7, 1937); Jeremy P. Felt, “The Child Labor Provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act,” Labor History, Vol. XI, Fall 1970, pp. 474-75; Interview, Jonathan Grossman with Gerard D. Reilly, Solicitor of Labor, Oct. 22, 1965.

21. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VI(May 24, 1937), pp. 209-14.

22. Record of the Discussion before the U.S. Congress on the FLSA of 1938, I.(U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics)(Washington, GAO, 1938), pp.20-21.

23. Hearings to Provide for the Establishment of Fair Labor Standards in Employments in and Affecting Interstate Commerce and Other Purposes, Vol. V.(1937). (U.S. Congress, Joint Committee on Education and Labor, 75th Cong., 1st sess), pp. 383-84.

24. Isador Lubin, Testimony, Hearings to Provide Fair Labor Standards(1937), pp.309-10.

25. Record of Discussion of FLSA of 1938, I(U.S. Department of Labor), pp.38, 115, 124.

26. Perkins, Roosevelt, pp. 257-59; Paul Douglas and Joseph Hackman, “Fair Labor Standards Act, I,” “Political Science Quarterly Vol. LIII, December 1938, pp. 500-03, 508; The New York Times, Aug. 18, 1937.

27. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VI (Oct. 4, 1937, Oct. 12, 1937, Nov. 15, 1937), pp. 404, 428-29, 496

28. Mrs.Norton replaced Representative Connery as chair of the House Labor Committee after his death.

29. Record of Discussion of FLSA of 1938, (U.S. Department of Labor), (1937), p. 415.

30. The New York Times, Dec. 13, 1937; Douglas and Hackman, “FLSA,” pp.508-11.

31. Perkins, Roosevelt, p. 261.

32. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VII (Jan. 3, 1938),p.6.

33. The New York Times, Jan. 5, Feb. 16, May 9, 1938.

34. Perkins, Roosevelt, p. 261.

35. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VII (Aug. 16, 1938), pp. 488-89; Perking, Roosevelt, pp. 262-63.

36. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VI(May 24, 1937), pp. 215; Perking, Roosevelt pp. 262-63.

37. Perking, Roosevelt, p.263; Roosevelt, Public Papers, VII (Aug. 16, 1938), p.489.

38. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VII(Apr. 30, 1938), pp.333-34.

39. Article for the following historical article written by Jonathan Grossman of the U.S. DOL“Department of Labor”.

39. The New York Times, May 6, 7, 1938; Perking, Roosevelt, pp.263-64 (Perking makes an error in the date of Lister Hill’s primary victory); Jonathan Grossman and James Anderson, interview with Clara Beyer, Nov 5, 1965.

40. Record of Discussion of FLSA of 1938. V (U.S. Department of Labor), p. 873.

41. “Interview with Clara Beyer, No. 25, 1965; U.S. Record of Discussion of FLSA of 1938. V (U.S. Department of Labor), pp. 873, 915, 929.

42. Record of Discussion of FLSA of 1938. V (U.S. Department of Labor), p. 902.

43. Roosevelt, Public Papers, VI (May 24, 1937), pp. 214-16.

Labor Day History – 82 Significant Years published first on https://iowalegendaryrye.com/ Labor Day History – 82 Significant Years posted first on https://iowalegendaryrye.com/

0 notes

Text

Labor Day History – 82 Significant Years

Our Labor for Love

For many, Labor Day signifies the end of summer and a chance to unwind during a long weekend. From relaxing by the pool to hosting a family barbecue, this extra day off allows people to catch their breath before the busy weeks ahead. However, despite how we may spend this holiday, Labor Day stands for so much more than just having good times with amazing people.

The history of Labor Day began during the Industrial Revolution when oppressive working environments were prevalent across the nation. At the time, honest, hard-working people endured harsh work conditions like 16-hour workdays and incredibly low wages. Fortunately, since then, laws have been put in place to protect workers from similar mistreatment. Today, Labor Day stands as a symbol of that history and a reminder to honor genuine, hard-working people in our community.

Celebrating Labor Day means celebrating unconditional labors of love. Whether your labor of love is protecting your community or raising your children, there is no specific definition that controls what a labor of love looks like. That’s the beauty of it!

A labor of love could be as simple as helping your neighbor across the street or as thought-out as enlisting in the Army to serve your country. At the end of the day, it all comes back to helping out the people you love most.

Iowa Legendary Rye’s Labor for Love

In most part, this labor day signifies a re-count of what our grandmother Lorine Sextro went through during prohibition and her labor to keep her family afloat by producing our great tasting rye.

Although at that time it was illegal to produce those spirits she went above and beyond to keep and maintain her family, farm, and homestead while letting others stay with her keep those she loved and family healthy with food and a warm place to stay during a time when our great nation was building its infrastructure.

We cannot forget our history and the labors of love that paved the way for our future.

Play Video

The Maximum Struggle for a Minimum Wage this Labor Day and our Labor of Love.

Labor Day Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938:

When he felt the time was ripe, President Roosevelt asked Secretary of Labor Perkins, ‘What happened to that nice unconstitutional bill you had tucked away?’

On Saturday, June 25, 1938, to avoid pocket vetoes 9 days after Congress had adjourned, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed 121 bills. Among these bills was a landmark law in the Nation’s social and economic development — Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (FLSA). Against a history of judicial opposition, the depression-born FLSA had survived, not unscathed, more than a year of Congressional altercation. In its final form, the act applied to industries whose combined employment represented only about one-fifth of the labor force. In these industries, it banned oppressive child labor and set the minimum hourly wage at 25 cents, and the maximum workweek at 44 hours.1

Forty years later, a distinguished news commentator asked incredulously: “My God! 25 cents an hour! Why all the fuss?” President Roosevelt expressed a similar sentiment in a “fireside chat” the night before the signing. He warned: “Do not let any calamity-howling executive with an income of $1,000 a day, …tell you…that a wage of $11 a week is going to have a disastrous effect on all American industry.”2 In light of the social legislation of 1978, Americans today may be astonished that; a law, with such moderate standards, could have been thought so revolutionary.

Courting disaster

The Supreme Court had been one of the major obstacles to wage-hour and child-labor laws. Among notable cases is the 1918 case of Hammer v. Dagenhart in which the Court by one vote held unconstitutional a Federal child-labor law. Similarly in Adkins v. Children’s Hospital in 1923, the Court by a narrow margin voided the District of Columbia law that set minimum wages for women. During the 1930s, the Court’s action on social legislation was even more devastating.3

New Deal promise. In 1933, under the “New Deal” program, Roosevelt’s advisers developed a National Industrial Recovery Act (NRA).4 The act suspended antitrust laws so that industries could enforce fair-trade codes resulting in less competition and higher wages. On signing the bill, the President stated: “History will probably record the National Industrial Recovery Act as the most important and far-reaching legislation ever enacted by the American Congress.” The law was popular, and one family in Darby, Penn., christened a newborn daughter Nira to honor it.5

As an early step of the NRA, Roosevelt promulgated a President’s Reemployment Agreement “to raise wages, create employment, and thus restore business.” Employers signed more than 2.3 million agreements, covering 16.3 million employees. Signers agreed to a workweek between 35 and 40 hours and a minimum wage of $12 to $15 a week and undertook, with some exceptions, not to employ youths under 16 years of age. Employers who signed the agreement displayed a “badge of honor,” a blue eagle over the motto “We do our part.” Patriotic Americans were expected to buy only from “Blue Eagle” business concerns.6

In the meantime, various industries developed more complete codes. The Cotton Textile Code was the first of these and one of the most important. It provided for a 40-hour workweek, set a minimum weekly wage of $13 in the North and $12 in the South, and abolished child labor. The President said this code made him “happier than any other one thing…since I have come to Washington, for the code abolished child labor in the textile industry.” He added: “After years of fruitless effort and discussion, this ancient atrocity went out in a day.”7

A crushing blow. On “Black Monday,” May 27, 1935, the Supreme Court disarmed the NRA as the major depression-fighting weapon of the New Deal. The 1935 case of Schechter Corp. v. United States tested the constitutionality of the NRA by questioning a code to improve the sordid conditions under which chickens were slaughtered and sold to retail kosher butchers.8 All nine justices agreed that the act was an unconstitutional delegation of government power to private interests. Even the liberal Benjamin Cardozo thought it was “delegation running riot.” Though the “sick chicken” decision seems an absurd case upon which to decide the fate of so sweeping a policy, it invalidated not only the restrictive trade practices set by the NRA-authorized codes but the codes’ progressive labor provisions as well.9

As if to head off further attempts at labor reform, the Supreme Court, in a series of decisions, invalidated both State and Federal labor laws. Most notorious was the 1936 case of Joseph Tipaldo.10The manager of a Brooklyn, N.Y., laundry, Tipaldo had been paying nine laundry women only $10 a week, in violation of the New York State minimum wage law. When forced to pay his workers $14.88, Tipaldo coerced them to kick back the difference. When Tipaldo was jailed on charges of violating the State law, forgery, and conspiracy, his lawyers sought a writ of habeas corpus on grounds the New York law was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court, by a 5-to-4 majority, voided the law as a violation of the liberty of contract.11

The Tipaldo decision was among the most unpopular ever rendered by the Supreme Court. Even bitter foes of President Roosevelt and the New Deal criticized the Court. Ex-President Herbert Hoover said the Court had gone to extremes. Conservative Republican Congressman Hamilton Fish called it a “new Dred Scott decision” condemning 3 million women and children to economic slavery.12

A switch in time. Wage-hour legislation was a campaign issue in the 1936 Presidential race. The Democratic platform called for higher labor standards, and, in his campaign, Roosevelt promised to seek some constitutional way of protecting workers. He tried to pave the way for such legislation in his speeches and news conferences in which he spoke of the breakdown of child labor provisions, minimum wages, and maximum hour standards after the demise of the NRA codes.

When Roosevelt won the 1936 election by 523 electoral votes to 8, he interpreted his landslide victory as support for the New Deal and was determined to overcome the obstacle of Supreme Court opposition as soon as possible. In February 1937, he struck back at the “nine old men” of the Bench: He proposed to “pack” the Court by adding up to six extra judges, one for each judge who did not retire at age 70. Roosevelt further voiced his disappointment with the Court at the victory dinner for his second inauguration, saying if the “three-horse team [of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches] pulls as one, the field will be plowed,” but that the field will not be plowed if one horse lies down in the traces or plunges off in another direction.”13

However, Roosevelt’s metaphorical maverick fell in step. On “White Monday,” March 29, 1937, the Court reversed its course when it decided the case of West Coast Hotel Company v. Parrish.14 Elsie Parrish, a former chambermaid at the Cascadian Hotel in Wenatchee, Wash., sued for $216.19 in back wages, charging that the hotel had paid her less than the State minimum wage. In an unexpected turn-around, Justice Owen Roberts voted with the four-man liberal minority to uphold the Washington minimum wage law.