#Harenchi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

chanmina - voice memo no. 5 // I just rage quit my homework tumblr hyd today

#im eepy. im also in the library and it sounds like the world is ending outside#i have been very tired this last week#i put on call this morning and then this song and i didn't even realize i guess chanmina dropped an album last year?#harenchi was great i have to listen to that and scandals new album ahh#i have no time to put on an album anymore#i need to eat something before my nighttime class#god its 430 its way past my bedtime#i have had some frustrations this week#song rec#chanmina#jpop#kpop#tbt#harenchi#shut up kaily#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

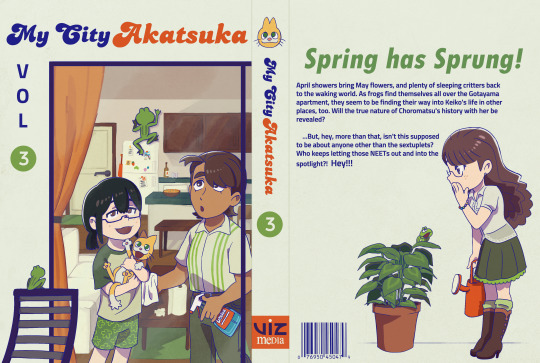

manga that will get cancelled after 26 chapters

#my art#osomatsu-san oc#ocs#kiru#keiko#ippei#this kabosu may be the cutest thing ive ever drawn i dont know. i know know#also the frogs are based on the frog on the cover of st. harenchi girls' school which is another akatsuka story#thats why they look a little weird. i tried my best#did you guys know green is my favorite color. have i made it obvious enough yet.

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shoujo Manga's Golden Decade (Part 3)

Shoujo manga, comics for girls, played a pivotal role in shaping Japanese girls’ culture, and its dynamic evolution mirrors the prevailing trends and aspirations of the era. For many, this genre peaked in the 1970s. But why?

Part 1

Part 2

Follow the Trend

Before we move on to the third movement of the '70s, let's take a quick look at an essential characteristic of shoujo manga: its sensitivity to trends.

The early '70s were a confusing time for the industry. There was extreme freedom in certain corners, with Yukari Ichijo, Machiko Satonaka, and other prominent artists drawing very adult-like drama in shoujo magazines for very young girls. In contrast, there was also a lot of moralism. The fact manga wasn't taken very seriously meant magazines could get away with a lot since adults considered them terrible influences anyway. But, at the same time, since manga wasn't a respected medium, they were also prone to hysteria. Nothing illustrates this scenario better than the controversies surrounding "Harenchi Gakuen," the first full-length series by Go Nagai, who went on to become one of the most celebrated manga artists of the '70s.

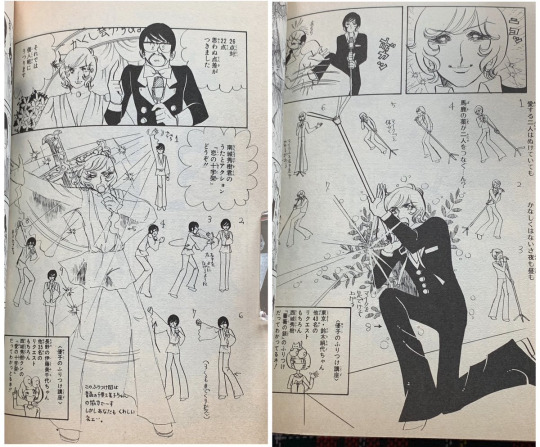

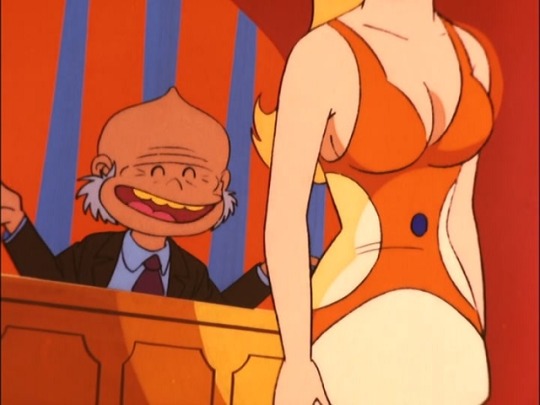

Shameless! The nudity and erotic jokes in Go Nagai''s "Harenchi Gakuen" were a hit with kids and teens, scandalized parents and teachers, and made the shoujo industry chase after their own erotic hits.

Nagai, already a respected yet fledgling name in the industry, was recruited by Shueisha to be part of Shonen Jump's inaugural team in the late '60s. Jump, as any manga fan knows, is by far the biggest success story in manga's editorial history. However, back then, it was just a newcomer in a field dominated by Kodansha's Weekly Shonen Magazine and Shogakukan's Shonen Sunday. Go Nagai's series, whose translated name meant "Shameless High School," is Jump's initial smash hit and one of the titles behind its extraordinary ascent.

But "Harenchi Gakuen," a gag manga with erotic jokes, scandalized adults across the nation. The Japanese Parents and Teachers Association successfully led a Shonen Jump boycott, getting the magazine banned in several shops across the country and triggering a media circus. At the time, agitated journalists often accosted Go Nagai at airports and public events, aggressively pointing their mics at him, a consequence of manga-kas celebrity-like notoriety during that era.

Meanwhile, the reaction around "Harenchi Gakuen" did not intimidate other manga magazines. In fact, all of them were pursuing their own "harenchi"-like phenomenon and publishing stories with erotic dirty jokes. And yes, that included the manga magazines for little girls. In Ribon, male manga-ka Hikaru Yuzuki was responsible for the "dirty" manga series. At Weekly Margaret, Yuzuki also had a considerable hit with the high school comedy "Elite Kyousoukyoku," which, while not precisely "ecchi," had a tone reminiscent of Nagai's work. At Nakayoshi, the artist in charge of this type of content was none other than a pre-"Candy Candy" Yumiko Igarashi.

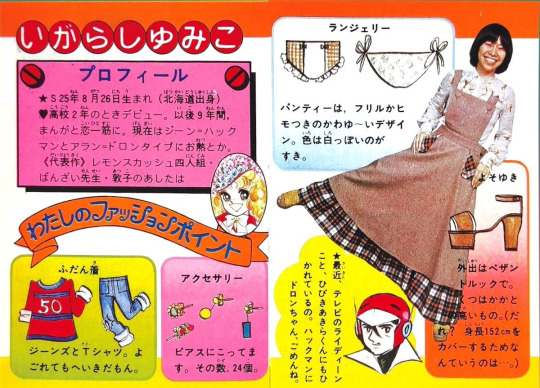

Before finding success with the smash hit "Candy Candy" manga, Yumiko Igarashi was the Nakayoshi artist in charge of recreating the "harenchi" phenomenon in the pages of the magazine. Above, in a good display of how public manga artists were in the '70s, Yumiko describes her panties as part of a Nakayoshi feature.

The "harenchi" phenomenon hinted at a shoujo field that wasn't yet wholly solidified and, therefore, was taking cues straight from the shonen segment, which would later become uncommon. But it also illustrates how the genre projects readers' dreams and preferences.

An example of this is one of Ribon's most popular series during the '70s, Yukko Yamamoto's "Miki to Apple Pie." Serialized between 1973 and 1976, this gag high school manga was full of absurd humor and nudity in the "Harenchi" vein. The twist is that it also had everything girls dreamed of.

The "apple pie" in the title was a reference to the lead character's favorite dessert during the time the American apple pie had just arrived in Japan and was considered the trendiest sweet. Miki Miyazawa, a popular and beautiful girl who served as the proxy for readers and was loosely modeled after talento Aki Aizawa, also loved astrology and the horoscope, and the romantic lead was a transfer student named Hideki Nanjo, who was a carbon copy of Hideki Saijo, the biggest popstar heartthrob of the '70s. Basically, "Miki to Apple Pie"'s central premise was "What if the popstars girls go crazy for was your silly gorgeous classmate?".

In fact, a testament to Saijo's popularity was how many shoujo manga romantic partners of the era used him as a model. Besides "Miki to Apple Pie," inserts of him were present in Satonaka Machiko's "Spotlight," Shigeko Maehara's "Kimi Iro no Hibi," Mayumi Yoshida's "Lemon Hakusho," among others.

With nudity, slapstick humor, and numerous references to trends and pop culture, "Miki to Apple Pie" became a sensation in the pages of '70s Ribon. The romantic lead, Hideki Nanjo, modeled after heartthrob Hideki Saiji, frequently performed impromptu renditions of popular hits from stars like Agnes Chan, Finger Five, Momoe Yamaguchi, Junko Sakurada, and, of course, Hideki Saiji himself. Full of shockingly offensive and scatological jokes, very little was considered off-limits, making "Miki to Apple Pie" a quintessential example of the distinctive '70s shoujo manga published during the peak of the "Harenchi" boom. It also serves as a perfect time capsule of its era, satirizing and commenting on everything popular at the time—from iconic products like the Panasonic Quintrix television and memorable TV commercials to celebrities, the toilet paper shortage during the Oil Shock, the Discover Japan campaign, and the widespread teenage girls' fascination with horoscopes. This manga elevated shoujo manga's trend obsession to unprecedented heights and mixed it with absurdity.

Saijo is a relic of the past, but shoujo echoing the trends of its time is a timeless characteristic of the genre. That's why most shoujo artists are women who are close in age to their readers: this sensibility to girls' desires is a vital component of the market. From the way the characters look to how they dress to even the shape of their eyebrows, everything is supposed to reflect its time. Therefore, to successfully create shoujo, one has to understand how girls perceive themselves and also how they want to be perceived. How they dress and look, but also how and what they dream of looking and wearing. What they aspire to and, above all, what they find attractive in the opposite sex.

It was precisely that sensitivity and this unique sense of what girls want and dream of that led to the creation of what is now the number 1 shoujo manga trope: the high school romance starring an unassuming, ordinary heroine. Leading the way was another group of artists that, while not as internationally celebrated as the Year 24 Group, are definitely equally as crucial to shoujo history.

The Otometique Fervor

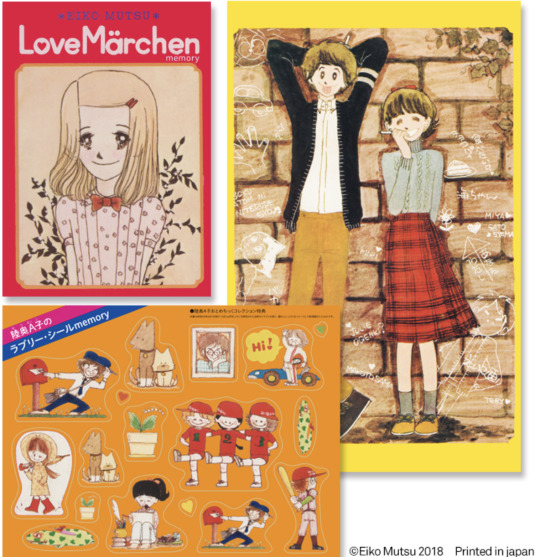

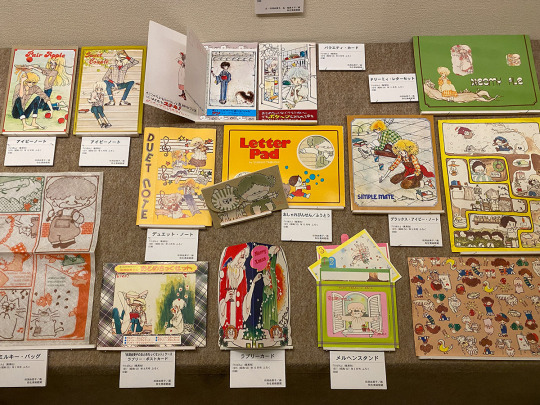

An "otometique" girl by Mutsu A-ko and some of the artist's popular furoku.

Yoshiko Nishitani, another of Shueisha's top shoujo artists of that era, is often credited as being the first to create a series around ordinary high school love. She did that in 1965's "Marie Lou," published in Weekly Margaret. "Marie Lou" was set in an American high school and had a very fashionable white girl as its lead. On her next manga, "Lemon to Sakuranbo" (Lemon and Cherries), she'd once again achieve immense success by bringing the teen romance closer to reality, using an ordinary Japanese high school as a backdrop.

While Nishitani pioneered this narrative style, the rise of more realistic, everyday stories gained momentum about a decade later. One catalyst for this was the "Otometique boom," a phenomenon that unfolded in the pages of Shueisha's Ribon magazine in the latter half of the '70s.

The term "Otometique" combines "otome," meaning "maiden" or a pure young girl, with the "-tique" (tikku in Japanese) suffix. A-ko Mutsu was the artist who spearheaded this movement.

A-ko made her debut in Ribon in 1971 at the age of 18. Her popularity skyrocketed four years later when her first short stories, led by "Tasogaredoki ni mitsuketa no" (What I Found at Twilight), were compiled into a tankobon that became a best-seller. This success elevated her status in Ribon, and soon her "otometique" style became the talk of the town.

Mutsu A-ko's art.

In contrast to the dramatic narratives of the "Satonaka-domain" faction, "otometique" stories adopted a more straightforward structure devoid of major plot twists and intense drama. Instead, they focused on modest love stories where the exhilarating moments were ordinary occurrences, like spotting a cute boy on the street or touching a crush's hand for the first time. While some stories included sad or supernatural elements, readers were captivated by the uncomplicated, heartwarming moments.

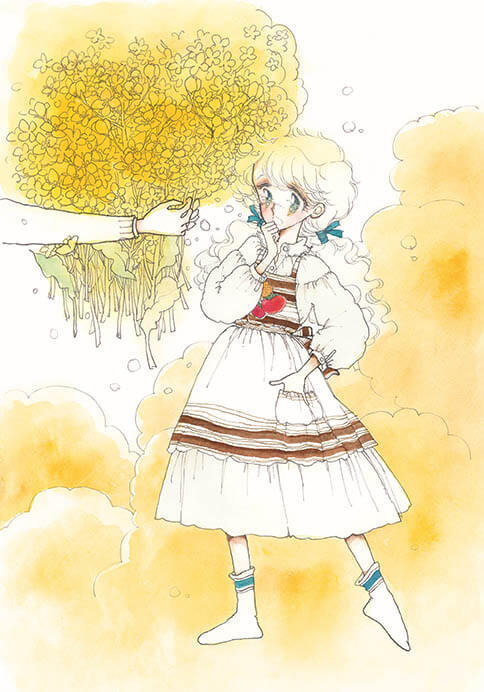

Ako's heroines were ordinary, unassuming schoolgirls, often characterized by shyness and insecurity. Different from extraordinary characters like Lady Oscar from "BeruBara" or the iconic Madame Butterfly tennis star in "Ace wo Nerae," Ako's protagonists were life-sized.

"Otometique" manga often incorporated romantic comedy tropes, such as chance encounters with cute guys on the way to school or the transformation into beauty after removing glasses. The happy endings typically featured a boy reciprocating the girl's love by accepting her as perfect and beautiful just as she was.

In otometique manga, girls were often in cute plaid and gingham check dresses and skirts, while boys were impeccably dressed in Ivy style, as seen in Mutsu Ako's art above.

While the stories may have seemed mundane, their distinctiveness lay in the meticulous attention to detail. As significant as the exploration of falling in love and discovering inner strength were all the visual details in "otometique" art. Girls had braids or long wavy hair and wore adorable clothes with plaids and gingham-check, as well as cute accessories. At a time when most Japanese girls still had Japanese-style rooms, "otometique" heroines had gorgeous Western-style rooms. They hung out in cozy cafes, made handmade goods, and ate tasty-looking sweets. Houses had French windows and balconies. Boys were tall, lean, with fluffy hair, and were always dressed impeccably in Ivy-style clothes. The "otometique" artists created an atmosphere that perfectly matched girls' aspirations at the time.

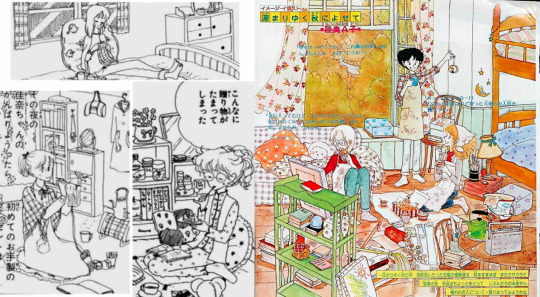

Girls often dreamed with having Western-style bedrooms like the ones in Otometique manga.

While Mutsu A-ko was the trailblazer, she was soon joined at the top by two other iconic artists, Yumiko Tabuchi, and Hideko Tachikake. Each of them had their quirks. Tabuchi, for example, often had college girls as her heroines, mirroring herself as a student at the elite, trendy Waseda University. While Tabuchi and A-ko preferred short stories, Tachikake had a penchant for longer series with a bit more drama. But they all had a similar aesthetic and relied on the charm of ordinary love.

The "otometique" phenomenon reflected the trends of the time and foreshadowed the emerging consumer culture that would swallow the country in the next decade. The sophisticated visuals attracted people of all ages, from elementary school-aged girls to highly educated women and men. Both the top public and private universities in Japan, Tokyo University and Waseda, respectively, had famous "otometique" clubs full of students who loved the genre and the style. The mangas were so trendy that they were often referred to as "Ivy mangas," in reference to the iconic Ivy style that was the catalyst of Japan's youth fashion, which was going through a second revival around that time.

While projecting an atmosphere that girls dreamed of, "otometique" also showcases '70s youth and girls' culture. Melancholic, simple love stories among young people were also the theme of the big folk hits of the time. Ivy or country fashion and long hair for men were the top fashion trends. Western-inspired ideals- in decoration, fashion, and musical taste- were pervasive. And creating subcultures and hobbies around consumption was the path society was taking. Simple life-sized stories as a narrative preference echoed the reality of Japan, which was stabilizing itself after decades of turbulence. These stories brought what the country was craving: comfort.

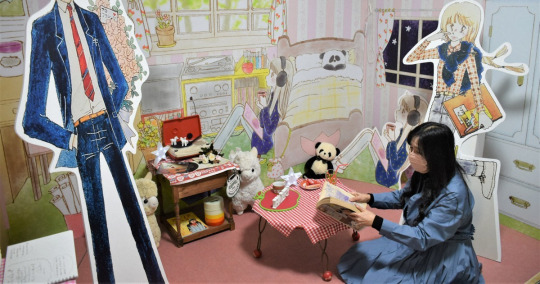

Above, a Mutsu A-ko's bedroom that lived in girls' imagination. Below, the room is recreated in a 2021 exhibition of Ako's art.

Meanwhile, the rise of consumer culture among young girls led to a "fancy goods" boom, with stores selling cute stationery, stickers, and small items popping up everywhere around the country. Illustrators and companies, eager to capitalize, spared no time in creating appealing mascots and drawings to adorn these goods, and it was in that period that Sanrio created Hello Kitty.

Ribon and Nakayoshi, which were "furoku" magazines, also benefitted. Furoku are extra gifts that come with the purchase of the magazines. And the "otometique" boom meant Ribon could include "fancy goods" -- like notebooks, stickers, letter sets, and small paper goods readers could assemble -- with the illustration of these highly sought-after artists. Most girls around Japan could only dream of Western-style rooms, a closet full of cute Ivy fashion, trips to trendy cafes, and homes with French windows. But they could recreate a bit of this sophisticated atmosphere by having letter sets, notebooks, stickers, and small accessories with A-ko Mutsu, Hideko Tachikake, and Yumiko Tabuchi's art. These popular furokus and the "otometique" stories were critical for Ribon magazine to surpass 1 million copies in circulation.

Girls admired A-ko, Tabuchi, and Tachikake not only as artists creating heartfelt stories with attractive atmospheres but as personalities. The trio, who were in their late teens and early 20s, closely resonated with their fans due to their proximity in age and shared interests. The readers were moved when Ribon featured an article in which A-ko Mutsu had the opportunity to meet and interview her favorite singer, the rock star Kenji Sawada, a prominent teen idol of that era. The positive response was so overwhelming that, a few issues later, Hideko Tachikake, an avid folk music enthusiast, also had the chance to interview her idol, Kosetsu Minami, the lead singer of Kaguyahime.

An otometique girl by Yumiko Tabuchi (left) and a collection of furoku illustrated by her as seen on a 2021 exhibition on her art.

The popularity of "otometique" peaked in 1977. By 1981, the boom had almost faded, and A-ko, Tabuchi, and Tachikake published their last works on Ribon in 1985. Tabuchi and Tachikake married and semi-retired, while A-ko successfully transitioned to manga for adult women.

Despite the end of the style, "otometique" permeated every corner of Japanese society. Its furoku and atmosphere were one of the bases for the almighty "kawaii" culture which now rules the country. The life-sized heroines and focus on mundane love stories and everyday emotions went on to become one of the main characteristics of the shoujo manga industry.

The Iwadate Domain

For years, the influence of "otometique" has been downplayed, one of the reasons why the movement is almost undiscussed in the West. However, in the last few years, best-selling books reminiscing the style were published, and exhibitions of A-ko Mutsu and Yumiko Tabuchi's works were big hits across Japan. A-ko, who moved back from Tokyo to her hometown in Fukuoka and never stopped creating manga, was recognized by the local prefecture as an honorary citizen and gained a permanent museum in the area, signaling her importance to the industry.

But while the "otometique" phenomenon happened on the pages of Ribon magazine, Mutsu, Tabuchi, and Tachikake weren't the only three attracting a massive audience to this type of real-life love story.

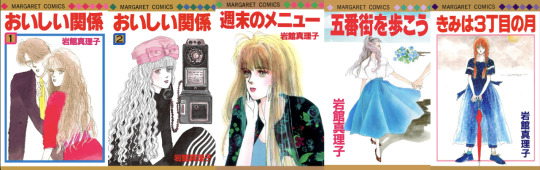

Mariko Iwadate's work was extremely popular from the late '70s to the mid-2000s. Above, a collection of her work from her Margaret era.

Going back to the research of sociologist Shinji Miyadai, three domains divided '70s shoujo. There was the "Moto Hagio domain," which included the Year 24 artists. The Hagio domain was more highbrow and intellectually challenging, and many considered it an equivalent to literature, attracting the intellectual elite that sniffed at manga in general. It is by far the most discussed and debated '70s shoujo movement, as well as the most famous in the West, but it was the least commercially successful at the time. Then there was the "Machiko Satonaka domain," with emotionally driven stories full of drama, plot twists, and larger-than-life heroines. Most of the '70s best-selling shoujo series fall under this category, which includes the work of Yukari Ichijo and Ryoko Ikeda and sports manga like "Ace wo Nerae," among others.

Finally, there's the domain in which the "otometique" stories were created. And Miyadai doesn't name it after any of the Ribon artists, calling it the "Mariko Iwadate domain" instead.

In the Satonaka domain, the heroine served as a proxy for the reader in a fantastical world, while in the Iwadate domain, the heroine represented the reader in the real world. But, after all, who is the influential Iwadate?

Mariko Iwadate, who made her debut in 1973 at the age of 16, rose to prominence by embracing the "otometique" style during its peak in the late '70s. Similar to Ribon artists, Iwadate, who mostly worked for Weekly Margaret, captivated readers with her elegant and stylish art, featuring cute clothes, accessories, and intricate details.

Miyadai's choice to name the category after Iwadate rather than the genre pioneer A-ko Mutsu may be attributed to Iwadate's sustained success. After leaving Ribon in 1985, A-ko remained prolific and had a dedicated audience, but she couldn't replicate her peak. Iwadate's popularity, on the other hand, continued unabated even after she transitioned to adult women's manga. Iwadate's work, recognized for its emotional depth, became a significant inspiration for trailblazers like best-selling novelist Banana Yoshimoto and avant-garde manga artist Kyoko Okazaki. In 1993, when Miyadai wrote his book, Iwadate's fame and respect probably made her a more recognizable figure for readers to associate with the category.

Iwadate's soft girly art and story-telling made her extremely popular and influential.

Mariko Iwadate's narrative, especially her post-80s work, has a more psychological and mature element to it when compared to Ribon's artists. She, as an artist, bridged the gap between "otometique" and another highly influential "Iwadate domain" artist, Fusako Kuramochi.

Fusako Kuramochi, debuting while still a teen in the early '70s at Bessatsu Margaret (Betsuma), initially emulated her favorite artists, Moto Hagio and Keiko Takemiya, before finding her style—a realistic portrayal of romance with a substantial psychological element. Her success contributed to shaping Betsuma, alongside Ribon, as arguably the most influential and commercially thriving shoujo title -- the go-to magazine for high school rom-com.

Like the otometique artists, Fusako Kuramochi first gained prominence with short stories and one-shots. In 1979, she wrote her first series, "Oshiaberi Kaidan," in which each chapter depicted the life of a young girl from junior high to her graduation day. In 1980, she published "Itsumo poketto ni Chopin," a classical music manga that also dealt with growing up as a teenager in the city. From then on, she'd publish about two hit series every year in Betsuma before graduating successfully to adult women's manga in 1994.

Kuramochi's success was due to her great skill in portraying girls going through crushes, heartbreaks, and jealousy. The psychological elements struck a chord with readers and helped her create male romantic leads that were extremely popular.

Another component of Kuramochi's work was her sophistication, a result of her upbringing. Her father was the chairman of one of Japan's biggest printing companies, and she was raised in Shibuya, in the center of Tokyo, while attending an exclusive all-female institution. The fact she spent her youth in the middle of Tokyo's hustle and bustle meant she knew the capital well, and her works were full of references to trendy cafes, restaurants, nightspots, and neighborhoods. Her Betsuma work was published right before and during Japan's ostentatious Bubble years, so many chasing an exciting city life referred to her work.

While her stories reflected the reality and aspirations of the Bubble years, Kuramochi's true gift lay in providing readers with a realistic depiction of growing up and falling in love, making her work immensely popular. In general, consumerism -- displayed through clothes, accessories, and decor -- isn't as crucial to her success as the three Ribon "otometique" artists.

While Fusako Kuramochi is part of the "Iwadate domain," you can argue that Kuramochi evolved into her own category, which was vital for the development of real-life love stories in shoujo in the '80s and '90s and the rise of other highly-influential artists like Ryo Ikuemi.

But going back to the three '70s movements, "otometique"/"Iwadate domain" was definitely the most influential one in steering shoujo manga in its current direction. On the other hand, all of these domains co-existed together and fed from each other. In 1977, during the "otometique" boom, Yukari Ichijo remained untouched as one of Ribon's most popular artists with her emotionally charged dramas. It was the success of Ichijo and other "Satonaka domain" artists that allowed the "Hagio domain" to debut and take risks. In turn, it was the "Hagio domain" that showed there were rewards for young risk-taking shoujo artists.

Yumiko Oshima, known for her girly art and sensitive story-telling, is the inspiration behind the otometique boom.

When asked which artist inspired them the most, both A-ko Mutsu and Mariko Iwadate gave the same answer: Yumiko Oshima. Oshima, known for her quirky love stories and girly art, is an artist who trained alongside Hagio and Takemiya at the Oizumi salon and rose as part of the "Year 24 group," publishing risk-taking manga in Shogakukan and Hakusensha's magazine after a brief stint in Weekly Margaret. In other words, despite the striking differences, the origin of the "Iwadate domain" is the "Hagio domain."

While the influence of the idealized real-life romance is the one we can better observe today, contemporary shoujo would not exist if not for all these three styles meshing together and creating something new. And from that, things kept evolving and changing and gaining new forms. Because, once again, manga, and especially shoujo manga, is about reflecting the girly ideals of its time.

#ribon#margaret#go nagai#miki to apple pie#yumiko tabuchi#otometique#otometique manga#mutsu a-ko#mutsu ako#hideko tabuchi#70s japan#fusako kuramochi#betsuma#shoujo manga#vintage shoujo#vintage manga#harenchi gakuen#yumiko igarashi#nakayoshi#yumiko oshima

46 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Double feature poster for Stray Cat Rock: Beat ‘71 (野良猫ロック 暴走集団’71) directed by Toshiya Fujita (藤田敏八) and starring Meiko Kaji (梶芽衣子) and Shin Harenchi Gakuen (新ハレンチ学園), directed by Isao Hayashi (林功) and starring Yayoi Watanabe (渡辺やよい).

#Meiko Kaji#梶芽衣子#Stray Cat Rock#Toshiya Fujita#Tatsuya Fuji#Stray Cat Rock: Beat '71#野良猫ロック 暴走集団’71#藤田敏八#藤竜也#Shin Harenchi Gakuen#新ハレンチ学園#Isao Hayashi#Yayoi Watanabe#渡辺やよい#林功#poster

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

recap episode thoughts: they should make collarbones illegal

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

bald adult men stop tagging your nudes with ‘devilman’ challenge!

#i’ve seen it too many fucking times i hate it here#same goes to all the girlies and the cutie honey tag#like this is more embarrassing than writing harenchi gakuen honestly#devilman#slava.txt

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

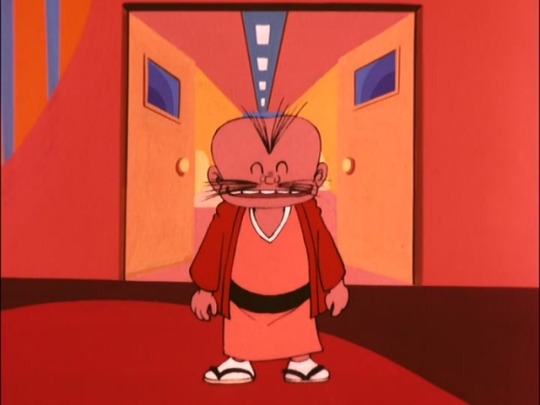

Familiar faces in Harenchi Gakuen

At this point, we should make a collection of every single 009 ref in other media

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

as a young person who didn't really know anything about anime and manga i remember having a very profound feeling about all of the female nudity in Ghost in the Shell (Mamoru Oshii's one). there was so much more nudity than i was used to, but it was also used in a way that i had never seen nudity used. i've been going back and reading some 60s/70s manga by Go Nagai and i think i'm starting to understand the setting of the stage for those uses of nudity; that, basically, female nudity is a motif which begins to be articulated in (let's say) Harenchi Gakuen in a way that is completely innocent—there is a pretty girl and the reader is invited to enjoy her body—but which repeats and returns over and over in so many forms that it is quickly made to accomodate other uses, until in something like Oshii's GitS female nudity can be made to express only something morbid, dissociative, melancholy (for some reason—Masamune's original manga is horny as fuck, click).

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Bambi” - The lost media of Yasuyuki Okamura

In honour of his 59th birthday - - -

youtube

This song has always been a topic that has interested me in Okamura’s works because it emerged during an awkward period in his career entering the 21st century. At this time in 1999, Okamura had partially returned from his brief hiatus where he produced songs for other artists, releasing The Forbidden Purpose of Life(禁じられた生きがい) album in the December of 1995 as well as the single Harenchi(ハレンチ) in 1996. But otherwise it was mostly radio silence and inactivity until the year of Bambi.

On the 14th of August, 25 years ago today, Bambi was released on the now discontinued music distribution site “Realrox.” The song was only aired once under the internet special program “Yasuyuki Okamura Summer Gift ‘99”

MP3 + lyrics under the cut ~

Because of this, only low quality rips of the song are available currently. These were taken from the website’s audio player, making it difficult to discern or transcribe the lyrics, but overall it’s pretty clear the song has a somber tone. Though it maintains the Okamura heavy funk style that he began to use around the early 2000s. Some fans compare the sound to “Sex (Old Version)” but personally it kinda reminds me of SOPHIA’s “Hard Worker” (which Okamura had also produced).

Either way, it’s really ‘distinctly Okamura’ in the way he uses SFX and sampling. There’s crow cawing throughout the entire track and engine sounds with reversed speaking weaving through the sections. What I like about Okamura’s music during this era was the very industrial and machine-like sound he produces, but it does feel incomplete here; especially when it transitions into an acoustic performance of “Ikenai Kotokai” … which sounds very different from its 1988 studio version. I don’t really know how to put it, but it feels so ominous and solemn. Though I guess it’s always been a sad song…

Looking into the actual lyrics for Bambi gives some insight, which were partially transcribed by an uploader on Nico Nico Douga (thank you!). Translations by me!

Bambi - Lyrics Translated

If I were Bambi,

Puppies and Pandas,

Rabbits and Ladybugs,

When they jump

They’ll smile and follow me around

But around us,

There are crows, crows

Crows surrounding us

They don’t even look aside, destroying only themselves

Their souls are corrupt

Hiding my hands, definitely a crow

[ Unintelligible ]

It’s my fault I can’t do live performances anymore

It’s my fault I can’t release records anymore

It’s my fault I’m pretentious

It’s because I’m brazen

It’s my fault I can’t do live performances anymore

It’s my fault I can’t release records anymore

It’s my fault I’m pretentious

It’s my brazenness

I’m brazen

—

Now this part is a bit speculative, but my reading of these lyrics is that they appear to be a personal reflection of Okamura’s struggles during the late 1990s. It’s expressed discreetly through the stark tonal contrast between the fairytale scene and the dark imagery of the crows, but then there’s the overt reference to his period of inactivity, where he blames himself. 1997-98 were pretty barren years, with no activity in the latter, so this must have been indicative of an intense struggle in Okamura’s life. From his debut he was able to release an album every year, as well as working on music for Misato Watanabe among other artists he had produced for. I’d hypothesise that during this period is when he would have started using stimulants, which he would later be arrested for. I can’t say for sure, however some fans attribute his significant weight gain to these drugs and excessive consumption of alcohol.

The song titled “Bambi” is perhaps an homage to Prince’s song sharing the name, as from the beginning of Okamura’s career he’s drawn heavy inspiration from the artist. Though the similarities are only surface level here as there’s no musical or lyrical similarities between the two.

—

25 years later, it all worked out. After his prison sentence was lifted, he returned to creating music and almost instantly returned to success. Since then, he’s announced his sobriety.

#lost media#Japanese lost media#japanese music#岡村靖幸#jpop icons#my translations#jpop artists#1999#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

tag game created by: @ibuprofen-exe

tagged by @lifesupreme-if and @thirtybythirty ^u^

Rules: Post a poll with three (or more) songs from one of your characters playlists, except there is a catch: one of the songs is not truly on their playlist. Have your followers guess, and when the poll is finished, reveal which song was the fake.

Doing another one of these for my dear darling catgirl Esme who endures all the scenarios I put her into with such fury <3

#done upon (enabling) request (ty tamber for letting me indulge lmao)#butterfly.esme#jinx thinks#tag meme#okay I *think* that's all my organisation tags. man i wanna write more esme stuff...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

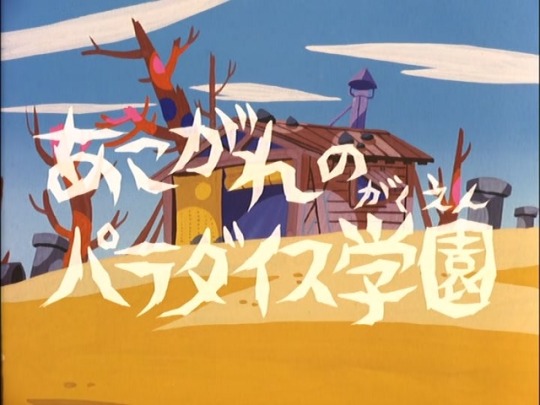

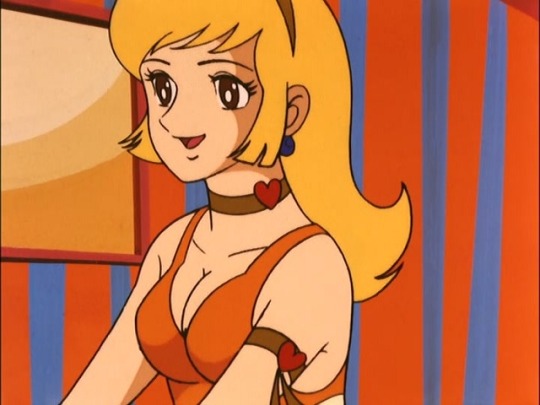

We got a lot of trivia for Cutie Honey episode 22: “My Beloved Paradise Academy.”

Screenwriter: Masaki Tsuji

Art Director: Iwamitsu Ito

Animation Director: Shinya Takahashi

Director: Kazukiyo Shigeno

The animation director for this episode, Shinya Takahashi, has a history of working on Toei Animation’s early majokko series. He previously did the character designs for Himitsu no Akko-chan, Mahou no Mako-chan, Sarutobi Ecchan, and Mahoutsukai Chappy.

Takahashi would later do animation work for the 1995 PC-FX video game, Cutey Honey FX.

The principal of Paradise Academy is based on the grandfather from Go Nagai’s Kikkai-kun manga, which is also where the characters Alphonne and Pochi originated from. Kikkai-kun’s grandfather also served as the basis for the janitor Kiyohiko Todoroki in the Devilman anime.

The principal was voiced by Isamu Tanonaka, who had filled in for Keiko Yamamoto as Pochi in the previous episode.

Goemon is based on Goemon Abashiri, the oldest son from the Abashiri Family manga. Goemon’s claim to fame is that he’s a “professional pervert.” Go Nagai’s assistant and good friend Ken Ishikawa was the model for Goemon. While he doesn’t appear in the original Cutie Honey manga, one of Honey’s (female) classmates is based on him. Goemon would make cameo appearances in New Cutey Honey, Re: Cutie Honey, and Cutie Honey Universe.

Shunji Yamada (later known as Keaton Yamada) voiced Goemon in this episode only, while Sanji Hase played him for the remainder of the series. Hase was previously the King of Manaco in episode 16 and the occasional nameless Panther subordinate.

The “Yoshitune” that Danbei sings about is probably Minamoto no Yoshitsune, a military commander from the late Heian and early Kamakura periods.

Danbei’s “adorable nephew” Naojiro is another character borrowed from Go Nagai’s Abashiri Family. In that series, Naojiro was the second oldest son of the Abashiri family. His unique feature was being a cyborg.

In the original Cutie Honey manga Naojiro does not appear as Danbei’s nephew but instead as a girl named Naoko. Naoko is the gang leader of St. Chapel Academy, much like how Naojiro is the gang leader of Paradise Academy in the anime. According to producer Toshio Katsuta, he wanted to introduce Naojiro as a good contrast to Honey, unlike Seiji who he said was “silly and weak.”

In this episode only, Naojiro was voiced by Hiroshi Masuoka, who previously voiced Demon General Zannin in Devilman and Hebitsubo in Dororon Enma-kun. For the remainder of the series Naojiro is voiced by an uncredited Shoji Nishizaki, who mostly did voice work in tokusatsu series.

Naojiro would later make a cameo appearance in the second episode of New Cutey Honey.

While Paradise Academy does not appear in the original Cutie Honey manga, it is very much inspired by Go Nagai’s infamous manga, Harenchi Gakuen. Before he was reinventing the concept of magical girls and giant robots, Go Nagai was stirring up controversy with this 1968 series. Harenchi Gakuen or “Shameless Academy” was one of the first manga to be featured in the popular Weekly Shonen Jump. It featured ridiculous Benny Hill-like antics, excessive nudity, lowbrow toilet humor, crucifixion scenes played for laughs and made a mockery of the Japanese school system. There was such outage towards Harenchi Gakuen, PTA groups actually performed public burnings of the manga. Despite the controversies, Harenchi was immensely popular, which led to live action TV series and films.

Paradise Academy’s name comes from the Abashiri Family manga. Originally, Paradise Academy was a prison-like middle school for aspiring young assassins and served as the setting for an early arc in the manga. A few of Naojiro’s classmates seen in this episode are taken directly from the Abashiri Family manga as well.

While attempting to evade Naojiro, Honey transforms into members of the baseball club, wrestling club and boxing club. As a boxer, she is only wearing shorts, shoes and boxing gloves. This is exactly how Kikunosuke dresses when she practices boxing in the Abashiri Family manga.

The self-proclaimed “Magician of Hell” was originally designed by Ken Ishikawa, who had her sporting more obvious magician motifs such as a giant top hat and bow tie. The “Great” in her name likely refers to a magician’s title.

Great Claw controlling Naojiro’s comrades with spider-like threads is possibly a reference to the Devilman manga. There are a couple of chapters involving a spider-like demon who controls the students of Nakado Academy and forces them to attack Akira and Miki. There is also an episode of the Devilman TV series which features a demon who controls human-like mannequins with spider threads.

This is also the only episode to not feature Panther Zora or Sister Jill.

That's all for episode 22!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

tagged by @dyke1 thank u 💋

🤍 top five songs rn 🤍

🖤 harenchi - chanmina

🖤 g.u.y - lady gaga

🖤 brand new house - the deep

🖤 hey girl - lee hyori

🖤 wiggle wiggle - hellovenus

i tag @girlsgenerati0n @whitechocolate @candiedsmokedsalmon and @emailclub luv u guyzzzz

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

When the windy night is over 風が強い夜が明けて And your scent is gone 君の匂いが消えて What will I do when I'm by myself 一人になったらどうしよう - Harenchi, Chanmina

say hello to one of my ffxiv kiddos, amai!! not a wol, but she's got the spirit, she can and will tear your gods from the heavens just to spite you. this piece here is a modern au version of her, where she gets to live a relatively peaceful life as a well-known singer. more info under the cut!!

the inspiration for her 'concept' is both avu-chan from queen bee and chanmina, who are both incredibly powerful singers with strong personas and very distinct visual styles. the actual outfit amai is wearing here is based on the outfit avu-chan wears in the song 'mysterious' which was the op for the anime 'raven of the inner palace'.

she's the type of idol/performer who has a very obscured past, but a sterling reputation in the industry, despite her devisive outfits and songs. before she became super famous she was dating my other xiv kiddo, nana (a wol), though they split up due to concerns regarding nana's safety.

#my art#ffxiv#final fantasy xiv#oc art#nana and amai split amicably but amai still burns a torch for her :(#nana misses her too but she doesn't want to tie amai down especially with her cultivated mystique so she let her go#(nana may or may not be dating haurche now too but that's a seperate thing)

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi! I'd like to ask a question about your Fire! post, because I got asked one when I reblogged it :) Can you elaborate a little bit on what you are referring to with the edgy stuff "Friends" did? I'd like check it out. Thank you, and have a nice February.

Hi! I was referring to Weekly Shoujo Friend, the other major weekly shoujo magazines in the 60s next to Weekly Margaret. These rival magazines followed different editorial directives and had different tones overall.

Initially Friends was considered to be the more conservative one. Even though many young female artists debuted in the magazine in the 60s (this was the decade when female artists became the main content providers of shoujo magazines), they weren’t really trusted to write their own stories, and most had to work based on narratives provided by separate writers. Kodansha continued this at least till the early 70s (I have to check further), and many artists hated it, for example, Aoike Yasuko (Eroica yori ai wo komete), who came into her own only after she left Kodansha and this practice. (There are exceptions, of course, Satonaka Machiko, who debuted at the same time as Aoike in 1964 (both were 16※), was mostly doing her own thing—with editorial guidance, of course.)

Conversely, Margaret recognized faster that young female readers would rather read what artists of their age group would create, and at the same time these young artists, many of whom debuted at 15-16, would know better how to approach readers hardly younger than themselves. This does not mean that there was no editorial guidance, and editors often suggested themes, literature, movies and such for young artists to use as a template for their stories, but Margaret was less rigid and reacted to the changes in demand faster. This is one of the reasons Weekly Margaret was the most popular shoujo magazine in the 60s, the first one to break a million copies in 1967, and even overall, the second manga related magazine to reach that number after Weekly Shounen Magazine.

While Friend hung on to family oriented dramas of young girls for quite long, Margaret switched to romantic comedies faster, first Hollywood-esque, then about foreign girls in foreign setting (mostly American), then about school girls in Japanese setting. Eventually Friend shifted too, but overall the magazine seems to be darker and more dramatic to me than Margaret, the art was also plainer, less decorative overall in Friend (huuuuuge exception is Hosokawa Chieko, who had the most amazing, most decorative, most unrestricted art in the 60s). This impression got only stronger in the late 60s/1970 when Friend had several serious coming-of-age dramas, like Mayuko no nikki by Yamato Waki and stories by Machiko&Kenji (all came with a writer, but it’s not always a bad thing). Especially Machiko&Kenji’s works have a touch of gekiga (this was the period when gekiga was widely popular, trickled into shounen manga and led to the birth of seinen manga magazines a few years before) and occasionally mixed with shounen manga line work. Mayuko on nikki is interesting too, it has some experimental artwork as well.

All in all, even though Margaret also had dramas, sometimes addressed societal issues, coming-of-age (the latter in foreign settings more in Bessatsu Margaret), and Friend also had its share of school girl love comedies, I feel Friend, that was more serious to begin with, gained an edgier, grittier tone as well by 1970. (Disclaimer: while I have read every issue of Weekly and Bessatsu Margaret from 1963 to 1970, I have only sampled Friend, a few issues per year, so far, so these are my impressions based on that.)

And since this came from the first bed scene, sexual revolution arrived in Japan as well, and by the late 60s it trickled down to manga magazines even for school boys and school girls. The infamous Harenchi Gakuen is a result of that, which caused the quite harmful trend of boys flipping girls' skirts in schools. These topics appeared in shoujo magazines in articles and manga as well, although often from a male perspective. Naughty (harenchi) behavior was kind of encouraged, and even regarding skirt-flipping girls were encouraged to “deal with it” as “boys will be boys” *rolls eyes* (Also never forget that one Friend issue in 1970 where teenage girl nude modeling was basically encouraged—photos included! *urgh*) Gradually articles about physical maturing of teenagers appeared, both about boys and girls, which were more serious, but in comedic shoujo manga “harenchi” elements (peeping toms, skirt-flippers) became frequent, and even more serious works featured shower scenes, underwear scene, nudity. Many of these were also from a male perspective (peeping toms not getting punished, girls being embarrassed, girls showing skin… in a shoujo manga), but many artists were more forward thinking and/or showed boys at the end of the female gaze as well.

Anyway, sexuality was kind of there at the end of the 60s, kissing became more frequent, and coming-of-age narratives featured sexuality, although mostly offscreen. I remember having seen panels of people in bed in at least one story I think in Bessatsu Margaret, but I can’t seem to find it among all my photos now.※※ An there are also the junior manga titles I mentioned, that featured more mature characters and relationship. Characters are obviously sleeping with each other, so at this point, when I haven’t read all the 60s shoujo and junior manga I would neither confirm nor deny that Fire! had the first bed scene ever (depends on the definition anyway.)

※By the way, it is often mentioned how Satonaka Machiko’s debut at 16 was a shock to young mangaka aspirant girls. However, her age is just one reason, several shoujo manga artists debuted that young or younger even before her. However, this was the start of manga awards for people aiming to be a manga artist, and with this (and also manga schools, a tradition started by Bessatsu Margaret not long after and immediately copied by almost every magazine) aspirants finally knew an exact way how they could become a manga artist. Before that it wasn’t clear at all, it involved sending or bringing manuscripts to publishers or older artists and so on.

※※Found it, it was in 1971 so it doesn't matter, Juliano no asa by Nishitani Yoshiko. Well, that was crazy stuff: the boy slept with the mother of his girlfriend thinking she might be his mother o_O

14 notes

·

View notes