#Hans Burgkmair the Elder woodcuts

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Renaissance Impressions, Chiaroscuro Woodcuts at the Royal Academy of Arts, London

Exhibition title: Renaissance Impressions Chiaroscuro woodcuts from the collections of Georg Baselitz and the Albertina, Vienna Dates: 15 March-8 June 2014 Venue: Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BD Admission price: £10.00 for an adult ticket, free to Friends of the Royal Academy This is an exhibition of sixteenth-century chiaroscuro woodcuts from Germany,…

View On WordPress

#chiaroscuro woodcuts exhibition#Hans Burgkmair the Elder woodcuts#making a two tone woodcut#Renaissance woodcut technique#Royal Academy of Arts exhibitions#turning paintings into woodcuts#Ugo da Carpi woodcuts#what is chiaroscuro

0 notes

Text

A Schlachtschwert, early XVIth century.

Spring steel blade of flat hexagonal section for most its length, mild steel fittings with hollow brass ball finials on the cross. Leather over thread over wooden core for the grip, and leather over wood for the sleeve (more about that below). This is a tentative reconstruction of what a "proper" Landsknecht Greatsword could look like, such a they appear on period artwork, be it paintings like the Siege of Alesia by Melchior Feselen (1533) or the Battle of Pavia kept at the Royal Armouries (or the tapestries depicting that same battle, now at the Museo Capodimonte, made after sketches by Bernard van Orley), the Victory of Charlemagne over the Avars near Regensburg by Albrecht Altdorfer (1518), or the many drawings, prints and woodcuts by artists such as Reinhart von Solms, Jörg Breu, the great Hans Burgkmair, Niklas Stör, Hans Holbein (both Elder and Younger), Virgil Solis, Hans Sebald Beham, the legendary Urs Graf, Daniel Hopfer, Erhard Schön, Hans Schäufelein and others...All of them combined to give this result.

Such swords would be seen not only in the hands of a Doppelsoldner, but also carried by your Feldwaybel or an Edelman. And it would be called a Schlachtschwert in the very captions of the illustrations I mentioned earlier (see Erhard Schön). *Not* a "two-handed Katzbalger", though the cross obviously echoes the S/8-shaped guard of the latter. We clear on that ? Good.

Very few of such swords are kept in museums out there, with a lot of them leaving me dubious regarding their authenticity. The one in Berlin seems to me to be the most genuine of all, and it is on its proportions that I based this piece, though the Berlin sword shows a fancy, diamond-pattern decoration on the quillions very much recalling the Katzbalger kept in the Museum of London. Most if not all period illustration do not show such fancy details on the crossguards though ; they are actually rather plain, without even the ribbing/threading/filework you can find on Katzbalger crosses. Hence I kept this one rather plain, with a square cross section with rounded corners, and some light filework at the center. I also bent the quillions into an offset 8-shape rather than a symmetrical one, to be more consistant with the earlier examples visible in period artwork.

The main questioning was that sleeve at the base of the blade, present on a lot of the period artwork; its obvious function was to provide a spot on which to put the other hand - as can be deduced from Marozzo's teachings for fighting against polearms - but the main issue was how was it made/what was it made of. Elaborating on my previous experience and studies of such things on later Schlachtschwerter, I went for a basic construction of leather glued/stitched over a wood core made of two flat slabs, and force-slid down the blade. There is more than enough friction to keep it well in place, but it is still possible to take it off albeit with some effort. The end of the leather is cut according to period artwork, and flares out to accommodate the mouth of a scabbard if needed. A simple decoration of plain lines on one side, and checkered on the other makes it also consistant with the artwork.

It is 139 cm long, the blade is 1083 mm long, 45 mm wide with a thickness of about 7 mm at its base, tapering down to 3.4 mm near the point. The span of the crossguard is about 21 cm, though from one ball end to the other there's about 73 cm of steel. Weight is 2547 grams, point of balance 13.5 cm from the cross.

Twenty-eight hundred EuroUnits and it's yours.

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

The double-headed eagle with coats of arms of individual states, the symbol of the Holy Roman Empire. Woodcut by Jost de Negker in 1510, after the monochrome version by Hans Burgkmair the Elder.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

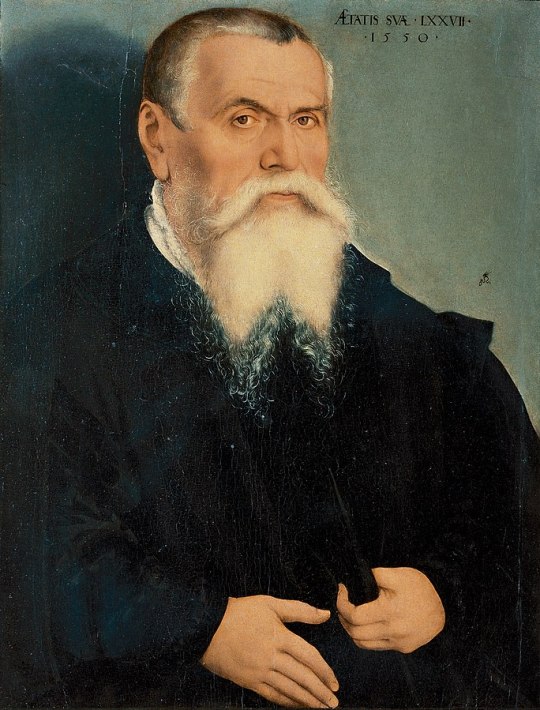

Lucas Cranach the Younger - Portrait of the artist's father, Lucas Cranach the Elder - 1550

Lucas Cranach the Younger (Lucas Cranach der Jüngere; October 4, 1515 – January 25, 1586) was a German Renaissance painter and portraitist, the son of Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Lucas Cranach the Elder (German: Lucas Cranach der Ältere German, c. 1472 – 16 October 1553) was a German Renaissance painter and printmaker in woodcut and engraving. He was court painter to the Electors of Saxony for most of his career, and is known for his portraits, both of German princes and those of the leaders of the Protestant Reformation, whose cause he embraced with enthusiasm. He was a close friend of Martin Luther. Cranach also painted religious subjects, first in the Catholic tradition, and later trying to find new ways of conveying Lutheran religious concerns in art. He continued throughout his career to paint nude subjects drawn from mythology and religion.

Cranach had a large workshop and many of his works exist in different versions; his son Lucas Cranach the Younger and others continued to create versions of his father's works for decades after his death. He has been considered the most successful German artist of his time.

He was born at Kronach in upper Franconia (now central Germany), probably in 1472. His exact date of birth is unknown. He learned the art of drawing from his father Hans Maler (his surname meaning "painter" and denoting his profession, not his ancestry, after the manner of the time and class). His mother, with surname Hübner, died in 1491. Later, the name of his birthplace was used for his surname, another custom of the times. How Cranach was trained is not known, but it was probably with local south German masters, as with his contemporary Matthias Grünewald, who worked at Bamberg and Aschaffenburg (Bamberg is the capital of the diocese in which Kronach lies). There are also suggestions that Cranach spent some time in Vienna around 1500.

From 1504 to 1520 he lived in a house on the south west corner of the marketplace in Wittenberg.

According to Gunderam (the tutor of Cranach's children), Cranach demonstrated his talents as a painter before the close of the 15th century. His work then drew the attention of Duke Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, known as Frederick the Wise, who attached Cranach to his court in 1504. The records of Wittenberg confirm Gunderam's statement to this extent: that Cranach's name appears for the first time in the public accounts on the 24 June 1504, when he drew 50 gulden for the salary of half a year, as pictor ducalis ("the duke's painter"). Cranach was to remain in the service of the Elector and his successors for the rest of his life, although he was able to undertake other work.

Cranach married Barbara Brengbier, the daughter of a burgher of Gotha and also born there; she died at Wittenberg on 26 December 1540. Cranach later owned a house at Gotha, but most likely he got to know Barbara near Wittenberg, where her family also owned a house, which later also belonged to Cranach.

The first evidence of Cranach's skill as an artist comes in a picture dated 1504. Early in his career he was active in several branches of his profession: sometimes a decorative painter, more frequently producing portraits and altarpieces, woodcuts, engravings, and designing the coins for the electorate.

Early in the days of his official employment he startled his master's courtiers by the realism with which he painted still life, game and antlers on the walls of the country palaces at Coburg and Locha; his pictures of deer and wild boar were considered striking, and the duke fostered his passion for this form of art by taking him out to the hunting field, where he sketched "his grace" running the stag, or Duke John sticking a boar.

Before 1508 he had painted several altar-pieces for the Castle Church at Wittenberg in competition with Albrecht Dürer, Hans Burgkmair and others; the duke and his brother John were portrayed in various attitudes and a number of his best woodcuts and copper-plates were published.

In 1509 Cranach went to the Netherlands, and painted the Emperor Maximilian and the boy who afterwards became Emperor Charles V. Until 1508 Cranach signed his works with his initials. In that year the elector gave him the winged snake as an emblem, or Kleinod, which superseded the initials on his pictures after that date.

Cranach was the court painter to the electors of Saxony in Wittenberg, an area in the heart of the emerging Protestant faith. His patrons were powerful supporters of Martin Luther, and Cranach used his art as a symbol of the new faith. Cranach made numerous portraits of Luther, and provided woodcut illustrations for Luther's German translation of the Bible. Somewhat later the duke conferred on him the monopoly of the sale of medicines at Wittenberg, and a printer's patent with exclusive privileges as to copyright in Bibles. Cranach's presses were used by Martin Luther. His apothecary shop was open for centuries, and was only lost by fire in 1871.

Cranach, like his patron, was friendly with the Protestant Reformers at a very early stage; yet it is difficult to fix the time of his first meeting with Martin Luther. The oldest reference to Cranach in Luther's correspondence dates from 1520. In a letter written from Worms in 1521, Luther calls him his "gossip", warmly alluding to his "Gevatterin", the artist's wife. Cranach first made an engraving of Luther in 1520, when Luther was an Augustinian friar; five years later, Luther renounced his religious vows, and Cranach was present as a witness at the betrothal festival of Luther and Katharina von Bora. He was also godfather to their first child, Johannes "Hans" Luther, born 1526. In 1530 Luther lived at the citadel of Veste Coburg under the protection of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and his room is preserved there along with a painting of him. The Dukes became noted collectors of Cranach's work, some of which remains in the family collection at Callenberg Castle.

The death in 1525 of the Elector Frederick the Wise and Elector John's in 1532 brought no change in Cranach's position; he remained a favourite with John Frederick I, under whom he twice (1531 and 1540) filled the office of burgomaster of Wittenberg. In 1547, John Frederick was taken prisoner at the Battle of Mühlberg, and Wittenberg was besieged. As Cranach wrote from his house to the grand-master Albert, Duke of Prussia at Königsberg to tell him of John Frederick's capture, he showed his attachment by saying,

I cannot conceal from your Grace that we have been robbed of our dear prince, who from his youth upwards has been a true prince to us, but God will help him out of prison, for the Kaiser is bold enough to revive the Papacy, which God will certainly not allow.

During the siege Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, remembered Cranach from his childhood and summoned him to his camp at Pistritz. Cranach came, and begged on his knees for kind treatment for Elector John Frederick.

Three years afterward, when all the dignitaries of the Empire met at Augsburg to receive commands from the emperor, and Titian came at Charles's bidding to paint King Philip II of Spain, John Frederick asked Cranach to visit the city; and here for a few months he stayed in the household of the captive elector, whom he afterward accompanied home in 1552.

He died at age 81 on October 16, 1553, at Weimar, where the house in which he lived still stands in the marketplace. He was buried in the Jacobsfriedhof in Weimar.

Cranach had two sons, both artists: Hans Cranach, whose life is obscure and who died at Bologna in 1537; and Lucas Cranach the Younger, born in 1515, who died in 1586. He also had three daughters. One of them was Barbara Cranach, who died in 1569, married Christian Brück (Pontanus), and was an ancestor of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

His granddaughter married Polykarp Leyser the Elder, thus making him an ancestor of the Polykarp Leyser family of theologians.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

KAISER MAXIMILIAN I

THE TWELFTH OF JANUARY 2019 was the 500th snniversary of the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilan I (1457/1519).

The son of Emperor Frederick III assumed the imperial throne in 1493, but never went to Rome to be crowned. He was married three times, all advantageously. His first wife, Mary of Burgundy, was the richest woman in Europe and her massive dowry included the manuscript collection of the Dukes of Burgundy. Maximilian never met his second wife, Anne de Bretagne, who was forced to repudiate him and marry his archenemy, Charles VIII (upon the death of Charles, Anne married Louis XII, making her the only woman to be Queen of France twice). Maximilian abandoned his third wife, the wealthy, yet vapid, Bianca Maria Sforza, through whom gained suzerainty over Milan. Upon her death, he renounced women as part of a program of religious austerity.

Throughout his reign, and despite the wealth of his wives, Maximilian lacked the financial means to fund his many wars and projects and resorted to loans from German bankers. Some of the loans were put to questionable use: one million gulden were borrowed from the Fugger bank for the purposes of bribing the German electors to secure the election of Maximilian’s grandson, Charles V, as the next emperor. At the time of his death, Maximilian owed German banks over 6 million gulden—the quivalent of 10 years of the annual revenues from the Hapsburg lands. These debts were not paid off until the end of the 16th century.

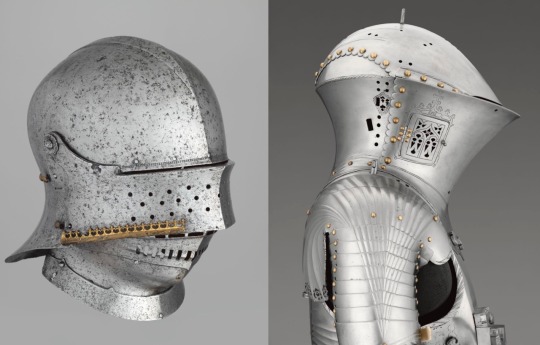

The notable areas of Maximilian’s artistic patronage were portraits, prints, and armor. Portraiture occupied a central role in the dissemination of official ideology in the early modern period. Maximilian’s court artist, Bernhard Strigel turned out dozens of portraits illustrating the various virtues and capacities of the emperor. Imperial patronage of Albrecht Dürer, Joos van Cleve and Giovanni Antonio di Predis reflected the artistic diversity of the far-flung Hapsburg dominions.

Throughout his early life, Maximilian closely identified with the culture of chivalry. This interest in knights in shining armor and tournements was probably greatly enriched by his 8-year sojourn in the Burgundian lands. Lucas Cranach the Elder portrayed Maximilian in the guise of Saint George, his hero as a youth, displaying his bravery and plumage, while rescuing the lady in distress. The emperor was also the author of Weißkunig (1506) and Theuerdank (1517), thinly-disguised autobiographical accounts of his early reign cast as chivalric romances. The printed books were illustrated with woodcuts by Hand Burgkmair and set in a stylish, blackletter typeface designed by Vinzenz Rockner. Maximilian circulated copies of these works to his allies and vassals as a means of controlling his public image.

The love of chivalry is most evident in the collection of suits of armor commissioned by Maximilian. Working closely with their patron throughout the design process, master armoirers turned out spectcular steel visions of knightly grace and strength. The style of armor favored by the emperor featured fluting, pleating, bird’s beak visors and other sculptural manipulations, with allusions to contemporary clothing. This stylem, which differed from the superficial engraving and gilding of the Milanese style, is known today as Maximilian armour.

As the nominal descendant of the western Roman emperors, Maximilian alluded to the ancient Romans in his arts patronage. The assertions of continuity with classical antiquity were often made using the most modern technologies available at the time. Die Triumphzug, an ambitious project depicting Maximilian celebrating a Roman triumph, was executed entirely in the new medium of print.

The artists including Hans Burgkmair, Dürer, and Dürer’s student, Albrecht Altdorfer, provided drawings of the various components of a Roman triumph, including a triumphal arch and chariot, which were transferred to woodblocks. The triumphal arch, by Dürer and his students, is composed of 195 woodcut images printed on 36 large sheets of paper. The triumpal procession, largely by Burgkmair, commemorates the expansion of Hapsburg territory under Maximilian. In all, 136 blocks were required to create an image 177 m long. Maximilian intended to send printed sets of these images to German princes, electors, and bishops, who were expcted to assemble and display the vast, composite images in palaces and public buildings. At the time of his death, the Triumphzug was unfinished. A truncated version was published in 1526. Several early copies were hand-colored.

Maximilian’s use of the new print technologies for his literary and artistic projects has often been described as a low budget choice forced by necessity on a financially-strapped ruler. While it is certain that Maximilian would have chosen more expensive and prestigious materials for some of his commissions (as evidenced by the Golden Roof in Innsbück), his choice of woodcut prints had an ideological value. By promoting a medium in which German artists excelled, he demonstrated the advanced cultural achievements of his Empire and the flourishing of the arts guided by his innovative patronage.

#holy roman empire#maximilian i#woodcut#albrecht dürer#german art - 16thc.#mary of burgundy#anne de bretagne#charles viii#charles v#hapsburg

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1.

Hans Burgkmair the Elder

Equestrian Portrait of the Emperor Maximilian I

1508, woodcut from two blocks in black and gold on vellum, Clarence Buckingham Collection

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473–1531) was a German painter and woodcut printmaker.

He was an important innovator of the chiaroscuro woodcut, and seems to have been the first to use a tone block, in a print of 1508. His Lovers Surprised by Death (1510) is the first chiaroscuro print to use three blocks, and also the first print that was designed to be printed only in colour, as the line block by itself would not make a satisfactory image.

Lovers Surprised by Death

Hans Burgkmair

1510

75 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Epitaph of CONRAD CELTIS, ‘Protucius’ (1459 - 1508) [German Humanist, scholar and poet]

woodcut by HANS BURGKMAIR the Elder, 1507

#conrad celtis#celtis#celtus#hans burgkmair#art#illustration#print#1507#augsburg#protucius#poet#artist#woodcut#erudite

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hans Burgkmair the Elder, Lovers Surprised by Death, 1510, chiaroscuro woodcut in three shades of brown on ivory laid paper, 21.7 × 15.7 cm, Art Institute of Chicago.

“Themes derived from the Dance of Death, a medieval allegory in which Death overcomes people of all ages and levels of society, pervaded German art in the late medieval and Renaissance periods. As the first true chiaroscuro woodcut, Hans Burgkmair’s compelling depiction of lovers torn apart by death is a work of pivotal importance. It represents a major cognitive leap on the part of the artist, who was the first to compose an organic three-dimensional composition by juxtaposing and overprinting three tones added by three different wood blocks.”

0 notes

Text

[:en]Hans Burgkmair[:zh]大汉斯·伯格马尔[:es]Hans Burgkmair[:ar]هانز بورغماير[:]

[:en]Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473–1531) was a German painter and woodcut printmaker

Burgkmair was born in Augsburg, the son of painter Thomas Burgkmair and his son, Hans the Younger, became one too From 1488, he was a pupil of Martin Schongauer in Colmar, who died during his two years there, before Burgkmair completed the normal period of training He may have visited Italy at this time, and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Lukas Furtenagel - The painter Hans Burgkmair and his wife Anna, born Allerlai - 1529

Lukas Furtenagel (1505–1546) was a German painter.

Lukas (Laux) Furtenagel was born in Augsburg in 1505 to a family of artists. He began studying art at a young age and was a protégé of painter Hans Burgkmair.

Furtenagel began his apprenticeship in 1515 at the age of 10. After leaving Augsburg, he briefly joined the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder in Wittenberg. Furtenagel was active in Halle from 1542 to 1546. In 1546, he was called to Eisleben to portray Martin Luther after the latter’s death. In the fall of 1546, after returning to Augsburg, Furtenagel was awarded the title of master.

Hans Burgkmair the Elder (1473–1531) was a German painter and woodcut printmaker.

Hans Burgkmair was born in Augsburg, the son of painter Thomas Burgkmair. His own son, Hans the Younger, later became a painter as well. From 1488, Burgkmair was a pupil of Martin Schongauer in Colmar. Schongauer died in 1491, before Burgkmair was able to complete the normal period of training. He may have visited Italy at this time, and certainly did so in 1507, which greatly influenced his style. From 1491, he worked in Augsburg, where he became a master and eventually opened his own workshop in 1498.

German art historian Friedrich Wilhelm Hollstein ascribes 834 woodcuts to Burgkmair, the majority of which were intended for book illustrations. Slightly more than a hundred are “single-leaf” prints which were not intended for books. His work shows a talent for striking compositions which blend Italian Renaissance forms with the established German style.

From about 1508, Burgkmair spent much of his time working on the woodcut projects of Maximilian I until the Emperor's death in 1519. He was responsible for nearly half of the 135 prints in the Triumphs of Maximilian, which are large and full of character. He also did most of the illustrations for Weiss Kunig and much of Theurdank. He worked closely with the leading blockcutter Jost de Negker, who became in effect his publisher.

He was an important innovator of the chiaroscuro woodcut, and seems to have been the first to use a tone block, in a print of 1508. His Lovers Surprised by Death (1510) is the first chiaroscuro print to use three blocks, and also the first print that was designed to be printed only in colour, as the line block by itself would not make a satisfactory image. Other chiaroscuro prints from around this date by Baldung and Cranach had line blocks that could be and were printed by themselves. He produced one etching, Venus and Mercury (c1520), etched on a steel plate, but never tried engraving, despite his training with Schongauer.

Burgkmair was also a successful painter, mainly of religious scenes, portraits of Augsburg citizens, and members of the Emperor's court. Many examples of his work are in the galleries of Munich, Vienna and elsewhere.

Burgkmair died at Augsburg in 1531.

20 notes

·

View notes