#Greek ethnocentrism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

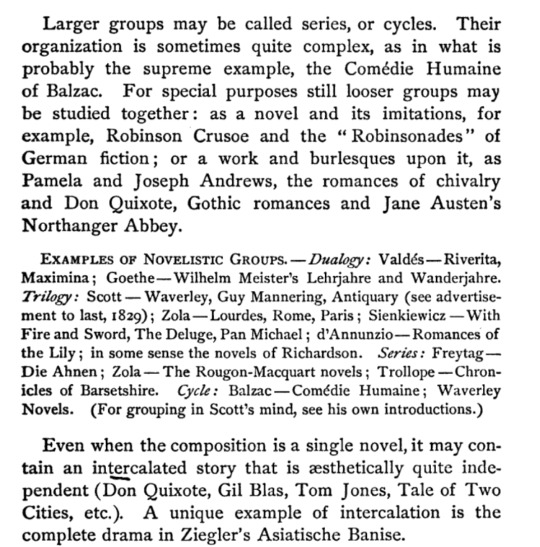

Writing References: World-Building

20 Questions ⚜ 100 Words for World-building

Basics: World-building ⚜ Places ⚜ Imagery ⚜ Setting

Exploring your Setting ⚜ Habitats ⚜ Kinds of Fantasy Worlds

Fantasy World-building ⚜ World-building Vocabulary

Worksheets: Magic & Rituals ⚜ Geography; World History; City; Fictional Plant ⚜ A General Template

Editing

Setting & Pacing Issues ⚜ Editing Your Own Novel

Writing Notes

Animal Culture ⚜ Autopsy ⚜ Alchemy ⚜ Ancient Wonders

Art: Elements ⚜ Principles ⚜ Photographs ⚜ Watercolour

Creating: Fictional Items ⚜ Fictional Poisons ⚜ Magic Systems

Cruise Ships ⚜ Dystopian World ⚜ Parts of a Castle

Culture ⚜ Culture Shock ⚜ Ethnocentrism & Cultural Relativism

Food: How to Describe ⚜ Lists ⚜ Cooking Basics ⚜ Herbs & Spices ⚜ Sauces ⚜ Wine-tasting ⚜ Aphrodisiacs ⚜ List of Aphrodisiacs ⚜ Food History ⚜ Cocktails ⚜ Literary Cocktails ⚜ Liqueurs ⚜ Uncommon Fruits & Vegetables

Greek Vases ⚜ Sapphire ⚜ Relics ⚜ Types of Castles

Hate ⚜ Love ⚜ Kinds of Love ⚜ The Physiology of Love

Mystical Objects ⚜ Talisman ⚜ Uncommon Magic Systems

Moon: Part 1 2 ⚜ Seasons: Autumn ⚜ Spring ⚜ Summer

Shapes of Symbols ⚜ Symbolism ⚜ Slang: 1930s

Symbolism: Of Colors Part 1 2 ⚜ Of Food ⚜ Of Storms

Topics List ⚜ Write Room Syndrome

Vocabulary

Agrostology ⚜ Allergy ⚜ Architecture ⚜ Baking ⚜ Biochemistry

Ecology ⚜ Esoteric ⚜ Gemology ⚜ Geology ⚜ Weather ⚜ Art

Editorial ⚜ Fashion ⚜ Latin Forensic ⚜ Law ⚜ Medieval

Psychology ⚜ Phylogenetics ⚜ Science ⚜ Zoology

More References: Plot ⚜ Character Development ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

#writing reference#worldbuilding#setting#writing tips#writing advice#writeblr#dark academia#spilled ink#literature#writing prompt#creative writing#fiction#writers on tumblr#story#novel#light academia#writing resources#compilation requested by anon#will update every few weeks/months

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

About "formal quality" in art

Oasis Nadrama, 24/11/2024

[Illustration: Wojciech Siudmak]

The idea that art is measurable, that there are ontologically "good" and "bad" creations, is one rooted in a search for performance in the capitalist system of domination (also rooted in pressure for productivity, superiority, and, most of all, competition, all tied to capitalism too).

It's also absolutely impossible to objectively measure the quality of art because everyone has different, generally untold criteria. What will make a good movie for me differs of what makes a good movie for you; I may (for example) favour large shot and contemplative scenes, while you would prefer closer shots and sharp editing.

This idea of formal quality is also tied to a formatted, ethnocentric vision of the world. AESTHETICS ARE NOT APOLITICAL OR ACULTURAL, the appreciation for some shapes, lines, values or palettes comes directly from an entire (generally western) history defining and redefining beauty. For example, in most European countries as well as the USA, monochromatic or almost monochromatic arrays of colours are favoured as "sober, more classical, more mastered and more elegant". But this perception comes from the way the Renaissance built our conception of "absolute beauty" as devoid of colours: in the 15th and 16th centuries, artists looked back at ancient art and misunderstood Greek or Roman statues and architectures as pure white. While in reality, such monuments were generally colorful, variegated, psychedelic even!

A lot of things changed in my perspective and appreciation of art when I managed to detach myself from the idea cultural products ought to be "rated", and when I came to understand there's a variety of definitions of "beauty". I encourage you to do the same, to open your mind.

There are worlds of different aesthetics out there, universes even.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotean Humor and Critique of Imperialism

"Another response to their historical situation and likewise an aspect of the competitiveness of both comedy and historiography is to showcase aggressive humour. One sure target of Aristophanes’ biting humour is those with intellectual pretentions, whether the sophists or others— whose familiarity to his audience made the humour all the more powerful. Herodotus likewise expects his audience to relish the humorous mockery of people who claim knowledge they don’t possess, whether Hecataeus in asserting divine ancestry at only sixteen generations’ remove (2.143), or the contemporary mapmakers who are deluded about the shape of the world (4.36). A picture emerges, then, of authors of both camps, historiographic and comedic, jousting and engaging with members of their intellectual community, a community either already familiar to their audiences, or soon made so by witty and stinging characterisations.

Aggressive, victimising humour involves outwitting and insulting one’s opponent. It shares targets across both genres, such as the tyrannical individual or group who abuses its power; and its serious monitory lessons are part of the educative tendency of both genres.40 Donald Lateiner focuses on premeditated insults, situating them in the context of the agonistic character of relations between Greek males in this period. Both genres reflect this aspect of Greek social relations, Aristophanes more intensively, the historians more rarely, and with the purpose of endowing certain characters and events with instructive vividness. Mark Mash in this volume analyses in detail a Herodotean staging of victimising humour and one-upmanship in the Ethiopian king’s response to the messengers from Cambyses. As Mash shows, the historian’s representation of this character’s use of competitive, victimising humour contributes to the Histories’ serious critique of imperialism.41 Humour serves to deflate intellectual presumptions or arrogant ethnocentrism or—even more arrogant—the drive to conquer others. For while Herodotus is in general terms a cultural relativist, there is a problem for him with the nomos of Persian imperialism (as with the drive for conquest that Herodotus reveals to be a key motivation of most human communities): in depriving others of political freedom, it negates their nomoi. The display of the Ethiopian king’s dexterous use of victimising humour is, then, a mise-en-abyme of the historian’s own use of a favourite tool of the Old Comedian.

A humorous trick can also be the means of provoking someone to reveal his character; and another historiographical narrative which exposes imperialism and greed, where the apparently weaker party triumphs, and a foreigner criticises the Persian king, is the humorous trick (ἀπάτην, 1.187.1) played by Herodotus’ Babylonian Queen Nitocris. To display—and memorialise (see next section)— the greed of some future conqueror of Babylon, and to take comeuppance on him, she sets her tomb high atop the main city gate, with an inscription inviting a future king to open it, should he need the money; but warning him otherwise to leave it alone. Undisturbed until Darius’ time, the tomb is opened, but Darius finds only a corpse and an inscription with the rebuke: ‘If you were not greedy of money and sordidly greedy of gain, you would not have opened the coffins of the dead’ (1.187.5). Triumph of the underdog—in this case, of a representative of victims of future imperialism—is a favourite scenario of comedy. Biting personal humour thus again becomes a serious means of resisting empire."

From the Introduction of Emily Baragwanath and Edith Foster (editors) to the collective volume Clio and Thalia. Attic Comedy and Historiography (2017), Histos Supplement 6, available on https://histos.org/documents/SV6.ComedyandHistoriography.pdf

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Great post OP! Thank you so much.

I would like to add: it discourages actual research on the demographic you're siding with.

For example, when people were claiming Achilles and other Ancient Greek heroes were black because [insert long pseudohistorical theory and lots of jumping to conclusions about Mediterranean peoples], lots of people were quickly content to add these black characters in the Iliad and...that's it. People realised they could get mad at people for representing Ancient Greek stories with white casts and pressured to add black people (with no thought about Greek/Mediterranean people) but at no point did they have to question 1) their rigid ethnocentric and present-centric views of race. They could continue to consider race universal to every time period and place on earth, without having to do the work to realise race is a social construct and its perception changes depending on culture. Many of the people involved in that discourse on the supposedly anti-racist side were treating race as a biological truth.

And 2) it only results in an extremely surface-level change. If they want "diverse stories", now they could just change the race of a few characters and that's it, no need to keep thinking about it. It stops the reflection on why did we lack black characters in the acclaimed mythology and literature that our society values. It's saying "hey, let's keep telling the same European stories, let's keep using the same Eurocentric measurements for what's valuable and good and what isn't" and it stops the consideration of, you know, if we want more black characters in mythology, there's a myriad of black cultures with hundreds and thousands years of stories, mythologies, literature (oral or otherwise) and other art forms that we aren't paying attention to. The problem of not knowing any black mythological characters (and what that means about the society we grew up in) isn't solved by saying "ah yes I do, because Achilles was actually black" without ever considering that African and African diaspora mythologies and literatures are just as fascinating, and why our society has historically considered Greco-Roman cultures superior and has developed systems of evaluating how """good""" something is based on them.

The same thing goes for many other arts. For example when people were claiming Beethoven was black because his death mask shows the symptoms of how your face changes after you die. I completely understand the relief in being able to tell White people "look! Black people have collaborated in your history! Black people have created these art pieces that you value so much!" and thus... Black people make art as good as White people and prove that Black people are equal and deserve the same rights and respect. And all of that is great and again I don't blame anyone for needing this validation from White people (or whatever their oppressor group is) because that's what society builds us to do, but I'm afraid that in Internet discourse this has often just ended there, it hasn't developed past "Beethoven was actually black" into other, deeper questions like "why is upper-class European music the one we value above others? Why is this one the symbol of elegance?" and it doesn't seem to have motivated many people involved in the discourse to go and research African and African diaspora music styles. When they're incredibly diverse and I'm sure many people would love them! The instruments and rhythms are different and it can be very cool to hear new stuff that you haven't been exposed to before. And also even if you don't like the ones you find (because our taste is developed according to what we've been exposed to) you will have gained a deeper understanding of human diversity and cultures and the possibilities of human creativity.

A note because this is the Internet and we all know people like to read things with the worst faith interpretation possible: if you're a fanfic writer who writes Greek/Hellene characters from Greek mythology as black characters, I don't care, you do you. Art is one thing and you can interpret it as you want. Though a certain amount of respect for the original story is important when you're telling a story that is as culturally-relevant as this, art is always understood to be subjective and a reflection of the author. If you're claiming it's an objective historical fact, that's where you're wrong.

Anti-racist, feminist, labour, etc organizations (almost always) do all these reflections very well. My criticisms are directed at the people who spread this pseudohistory and don't care that it's fake.

Lastly, I would like to add: if you don't look at facts, how do you know that what you feel is true is actually true? Do you think that conservatives don't feel that racialized people lesser, do you think they don't feel that women exist just to take care of men, do you think they don't feel that disabilities make you less worthy of rights? And does society not raise us all with such ideas all around us? If you don't care about facts, how do you know that what others feel is true is actually wrong, but what you feel is true is actually right?

I get variations on this comment on my post about history misinformation all the time: "why does it matter?" Why does it matter that people believe falsehoods about history? Why does it matter if people spread history misinformation? Why does it matter if people on tumblr believe that those bronze dodecahedra were used for knitting, or that Persephone had a daughter named Mespyrian? It's not the kind of misinformation that actually hurts people, like anti-vaxx propaganda or climate change denial. It doesn't hurt anyone to believe something false about the past.

Which, one, thanks for letting me know on my post that you think my job doesn't matter and what I do is pointless, if it doesn't really matter if we know the truth or make up lies about history because lies don't hurt anyone. But two, there are lots of reasons that it matters.

It encourages us to distrust historians when they talk about other aspects of history. You might think it's harmless to believe that Pharaoh Hatshepsut was trans. It's less harmless when you're espousing that the Holocaust wasn't really about Jews because the Nazis "came for trans people first." You might think it's harmless to believe that the French royalty of Versailles pooped and urinated on the floor of the palace all the time, because they were asshole rich people anyway, who cares, we hate the rich here; it's rather less harmless when you decide that the USSR was the communist ideal and Good, Actually, and that reports of its genocidal oppression are actually lies.

It encourages anti-intellectualism in other areas of scholarship. Deciding based on your own gut that the experts don't know what they're talking about and are either too stupid to realize the truth, or maliciously hiding the truth, is how you get to anti-vaxxers and climate change denial. It is also how you come to discount housing-first solutions for homelessness or the idea that long-term sustained weight loss is both biologically unlikely and health-wise unnecessary for the majority of fat people - because they conflict with what you feel should be true. Believing what you want to be true about history, because you want to believe it, and discounting fact-based corrections because you don't want them to be true, can then bleed over into how you approach other sociological and scientific topics.

How we think about history informs how we think about the present. A lot of people want certain things to be true - this famous person from history was gay or trans, this sexist story was actually feminist in its origin - because we want proof that gay people, trans people, and women deserve to be respected, and this gives evidence to prove we once were and deserve to be. But let me tell you a different story: on Thanksgiving of 2016, I was at a family friend's house and listening to their drunk conservative relative rant, and he told me, confidently, that the Roman Empire fell because they instituted universal healthcare, which was proof that Obama was destroying America. Of course that's nonsense. But projecting what we think is true about the world back onto history, and then using that as recursive proof that that is how the world is... is shoddy scholarship, and gets used for topics you don't agree with just as much as the ones you do. We should not be encouraging this, because our politics should be informed by the truth and material reality, not how we wish the past proved us right.

It frequently reinforces "Good vs. Bad" dichotomies that are at best unhelpful and at worst victim-blaming. A very common thread of historical misinformation on tumblr is about the innocence or benevolence of oppressed groups, slandered by oppressors who were far worse. This very frequently has truth to it - but makes the lies hard to separate out. It often simplifies the narrative, and implies that the reason that colonialism and oppression were bad was because the victims were Good and didn't deserve it... not because colonialism and oppression are bad. You see this sometimes with radical feminist mother goddess Neolithic feminist utopia stuff, but you also see it a lot regarding Native American and African history. I have seen people earnestly argue that Aztecs did not practice human sacrifice, that that was a lie made up by the Spanish to slander them. That is not true. Human sacrifice was part of Aztec, Maya, and many Central American war/religious practices. They are significantly more complex than often presented, and came from a captive-based system of warfare that significantly reduced the number of people who got killed in war compared to European styles of war that primarily killed people on the battlefield rather than taking them captive for sacrifice... but the human sacrifice was real and did happen. This can often come off with the implications of a 'noble savage' or an 'innocent victim' that implies that the bad things the Spanish conquistadors did were bad because the victims were innocent or good. This is a very easy trap to fall into; if the victims were good, they didn't deserve it. Right? This logic is dangerous when you are presented with a person or group who did something bad... you're caught in a bind. Did they deserve their injustice or oppression because they did something bad? This kind of logic drives a lot of transphobia, homophobia, racism, and defenses of Kyle Rittenhouse today. The answer to a colonialist logic of "The Aztecs deserved to be conquered because they did human sacrifice and that's bad" is not "The Aztecs didn't do human sacrifice actually, that's just Spanish propaganda" (which is a lie) it should be "We Americans do human sacrifice all the god damn time with our forever wars in the Middle East, we just don't call it that. We use bullets and bombs rather than obsidian knives but we kill way, way more people in the name of our country. What does that make us? Maybe genocide is not okay regardless of if you think the people are weird and scary." It becomes hard to square your ethics of the Innocent Victim and Lying Perpetrator when you see real, complicated, individual-level and group-level interactions, where no group is made up of members who are all completely pure and good, and they don't deserve to be oppressed anyway.

It makes you an unwitting tool of the oppressor. The favorite, favorite allegation transphobes level at trans people, and conservatives at queer people, is that we're lying to push the Gay Agenda. We're liars or deluded fools. If you say something about queer or trans history that's easy to debunk as false, you have permanently hurt your credibility - and the cause of queer history. It makes you easy to write off as a liar or a deluded fool who needs misinformation to make your case. If you say Louisa May Alcott was trans, that's easy to counter with "there is literally no evidence of that, and lots of evidence that she was fine being a woman," and instantly tanks your credibility going forward, so when you then say James Barry was trans and push back against a novel or biopic that treats James Barry as a woman, you get "you don't know what you're talking about, didn't you say Louisa May Alcott was trans too?" TERFs love to call trans people liars - do not hand them ammunition, not even a single bullet. Make sure you can back up what you say with facts and evidence. This is true of homophobes, of racists, of sexists. Be confident of your facts, and have facts to give to the hopeful and questioning learners who you are relating this story to, or the bigots who you are telling off, because misinformation can only hurt you and your cause.

It makes the queer, female, POC, or other marginalized listeners hurt, sad, and betrayed when something they thought was a reflection of their own experiences turns out not to be real. This is a good response to a performance art piece purporting to tell a real story of gay WWI soldiers, until the author revealed it as fiction. Why would you want to set yourself up for disappointment like that? Why would you want to risk inflicting that disappointment and betrayal on anyone else?

It makes it harder to learn the actual truth.

Historical misinformation has consequences, and those consequences are best avoided - by checking your facts, citing your sources, and taking the time and effort to make sure you are actually telling the truth.

15K notes

·

View notes

Text

Debunking Misconceptions: The Paris Olympics Opening Ceremony and Dionysus Celebration

I’m not sure who needs to hear this, but here we go. To whom it may concern, Careful now! Your ethnocentrism is showing, and it’s not a good look. No, Paris wasn’t mocking Christianity and y’all need to calm down. Stop making unfounded claims to stoke fear and anger to create attacks that aren’t happening like wars on Christmas. It was a celebration of Dionysus, the Greek God of wine,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

This is what it feels like whenever I see people judging myths with an ethnocentric opinion without regard for the history of where these myths came from, how they were shaped, or the historical value of what they mean. So this is what it reads like to me whenever I see someone judging a Greek myth based on their very limited understanding of it:

Ancient Greek person: This person in my ancestral bloodline was amazing! My grandfather told me he did so many incredible things no human thought was possible, like fighting monsters! My whole family assumes he was a child of Zeus because how else would he have been so blessed?! We're gonna make songs and stories praising his name so the people around us know he was a hero and a demigod! We're gonna venerate him as an ancestor and hope history never forgets his name or the place where he came from! We're gonna immortalize our family through him and let the world know lord Zeus still protects us because we are a part of him!

Modern people reading that same story after it survived thousands of years and is now a well known myth: Yet another demigod? Zeus puts his dick in everything doesn't he? What a POS!

Me:

#hellenic polytheism#hellenic deities#hellenic paganism#lord zeus#zeusdeity#zeusreligion#zeus worship#zeus positive

638 notes

·

View notes

Text

Molly Levine reviews and criticizes the “post-colonial” book of Phiroze Vasunia “The Gift of the Nile: Hellenizing Egypt from Aeschylus to Alexander”

The Gift of the Nile: Hellenizing Egypt from Aeschylus to Alexander. Classics and Contemporary Thought, 8

Phiroze Vasunia, The gift of the Nile : hellenizing Egypt from Aeschylus to Alexander. Classics and contemporary thought ; 8. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. xiv, 346 pages : illustrations ; 24 cm.. ISBN 0520228200 $45.00.

Review by

Molly Levine, Howard University.

In the past decade, considerable scholarly attention has focused on the evidence for ancient traditions regarding Greek indebtedness to Egypt. Attention has focused especially on the texts adduced by Martin Bernal’s Black Athena (= BA) texts which Bernal used to support his hypothesis of an “Ancient Model” of early, “massive” contacts between Egypt and Greece.1 Phiroze Vasunia’s The Gift of the Nile: Hellenizing Egypt from Aeschylus to Alexander, while not explicitly conceived as a response to Bernal, remains in a very real sense just that. Vasunia examines many of the same texts as Bernal, but from a different perspective. The avowed goal of his book is “to examine a particular case of ethnocentrism which is localized to the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E., to inquire into its methods and its grammar, and to investigate the factors that motivated it, the ideologies that sustained it, and the real and sometimes devastating uses to which it could be put by Greeks” (17).

In focusing only on what the ancient Greek texts on Egypt tell us about the Greeks, Vasunia heeds the advice of Edith Hall, who argued against Bernal that Greek traditions on contacts between Greece, Egypt, and the Levant cannot and should not be used as evidence for historical realities in the Bronze Age. Rather, Greek depictions of “Others”, including Egypt and Egyptians, should be read only for what they can tell us about the contemporary ethnic world view of the ancient Greeks themselves.2

Like Bernal, Vasunia insists that Greek discourse on Egypt is the source of many contemporary themes that can be traced back through the European Renaissance and the Enlightenment (17-18). But with the exception of a useful, though brief, summary of the historical relations between Greece and Egypt during the Egyptian Late Period from 664-332 B.C.E. (20-29), Vasunia uses historical materials primarily as a ‘reality check’ for his broader interpretation (19-20), and is “less concerned than Bernal with establishing historical facts” as such, and instead focuses on “representation, rhetoric, and the politics of literature” (17).

A few examples can illuminate some critical differences in the approaches of these two scholars to the question of how to read Greek texts on Egypt. For Vasunia, Isocrates’ Busiris, a text to which Bernal devoted several pages (BA I, 103-108) and Vasunia an entire chapter (“Reading Isocrates Busiris,” 183-215), rather than affirming a tradition of Greek cultural indebtedness to Egypt, “is largely orthodox in its reinscription of the other…[perpetuating] the cultural stereotype of Egyptians as xenophobic and inclined to human sacrifice” (200). Both Bernal and Vasunia read the speech against its contemporary fourth-century political and intellectual context and specifically link it to Isocrates’ rivalry with Plato. But Bernal, while admitting that the speech was on one level a rhetorical tour de force, insists that “to be convincing, the speech had to appeal to conventional wisdom” on the cultural indebtedness of Greece to Egypt (BA I, 103). Vasunia places much more emphasis on genre (an area that Bernal was criticized for slighting), arguing that one cannot read Busiris without taking into account the complex nature of its parody that “takes a fixed tradition and reasserts it, though in the guise reversing or altering it” (207). So, contra Bernal, Vasunia’s Isocrates emerges as no unqualified admirer of Busiris and/or Egyptian traditions.

Or, in another example, to Vasunia’s question “Why do both Plato and Isocrates appear so ready to say that Greek philosophers and wise men such as Solon and Pythagoras visited Egypt?” (229), Bernal would respond because they, in fact, visited Egypt (BA I, 108). Not so, says Vasunia, who eschews the historical question (229, 242; cf. 232, 234) and prefers to focus on what these stories say about the “cultural anxieties” of fourth-century Greeks for whom “to discover one’s wisdom along the shores of the Nile is not only to make Egypt a theatre where one may represent oneself to one’s own, but also to betray the anxious symptoms of a lack” (242).

But the difference between the treatments of many of the same texts by the two authors goes much deeper. As befits a book published in a series that “seeks to establish connections between specialized research on Greco-Roman antiquity and broader inquiry in the humanities, arts, and social sciences” (vii), Vasunia applies contemporary post-colonial criticism to ancient literature using a teleological scheme that posits “a relationship between knowledge and power” (11), the “claim of discourse driving Empire” (249). In this view, “European study of non-European cultures has led to colonial hegemony and political control … discourses that seem the most benign can come to have a crucial influence on mechanisms of authority and command” (12). This means that Vasunia reads fourth and fifth century Greek texts on Egypt not simply as reflections of contemporary concerns but as harbingers of future events. For Bernal, myth preserved the long-forgotten tracks of real historical events in the past. But in Vasunia’s post-colonial reading, cultural myths pave the way for real historical events in the future, in this case the fourth-century conquest and subjugation of Egypt by Alexander the Great in the name of Hellenism, an event that, for Vasunia, is “a tangible and material realization” of the politics that informed Greek representations of Egypt in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E. (248, cf. 248-49, 287). In this view, no matter how heterogenous these texts on Egypt are, they contain common elements that “recur and intersect across the works of authors,” much like British writings on India from 1600-1800 (9-10). According to Vasunia, “no Greek reference to Egypt in the years before Alexander is innocent of this gross fact…, however sentimental the reference may appear, however distant it may seem from Alexander’s invasion and the subsequent rule by the Ptolemies” (6). While acknowledging the possibility of anachronism and “genuine differences” between the classical Greek world and the age of modern imperialism, Vasunia claims that “taken together, Herodotus, Homer, Aristotle, and other Greeks were a defining part of the ideological background that shaped Alexander’s conquest of Egypt” (12, cf. 32).

The structure of Vasunia’s book parallels its “teleological” thesis. A series of chapters on major prooftexts for his argument — Aeschylus’ Suppliants; Euripides’ Helen; Herodotus Book II; Isocrates Busiris; and passages from Plato’s Phaedrus, Timaeus, and Critias — culminates in a final chapter on Alexander’s conquest and occupation of Egypt. The book also includes a useful appendix of translated fragments from Greek historians on Egypt from Hecataeus (ca. 500 B.C.E.) through 332 B.C.E. and a rich, well chosen bibliography.

Each chapter applies post-colonial theory to specific ancient texts, with varying degrees of success. For example, in Chapter One on “The Tragic Egyptian,” Vasunia argues that Aeschylus’ Suppliants and Euripides’ Helen configure “issues of erotics, desire, and race…in relation to death” (12), in anticipation of Edward Said’s characterization of the western view of the Orient as hypersexual and fecund ( Orientalism, epigraph 33, and discussion 35-36). Egyptian males in the Suppliants and Helen are portrayed as hypersexed suitors pursuing a deadly marriage with the Egyptian Danaids or the Greek Helen in two tragedies that stereotypically identify Egypt with death and depict the aggressive desire of male Egyptians as deadly. By Vasunia’s reading, in the discourse of Athenian tragedy, “the way to preserve the social polity and to prevent ethnic contamination is to make abhorrent the union between these men and women” (74).

There is little to quarrel with in Vasunia’s argument that Athenian drama uses Egyptian men as “vehicles for the exploration and realization of Greek men’s covert desires”(38), but his attempt to distinguish his two Egyptian tragedies from the entire corpus of Athenian tragedy is not entirely persuasive. Vasunia’s tragic Egyptian weddings may be a matter of the ethnic tail wagging the dog of gender, piggybacking on the more universal Greek idea of sex and marriage as fraught with mortal danger, especially for women. As for Egypt as a sign for alterity in tragedy, Vasunia himself points out that of the extant tragedies only the Helen has Egypt as its setting (59 n.68), and in the tragic theater one need look no farther abroad than Thebes for the “Other” city in which Athenian social conflicts and repressed psychosexual desires can be acted out.3 Although apparently sensitive to these problems, Vasunia’s suggested solutions are unsatisfying. For example, Aeschylus’ Suppliants is distinguished from some of the other plays which conflate marriage with death for the female “insofar as it dramatizes in detail the events that lead to a wedding and the married life rather than the experiences of individuals who are already married” (54). What of tragic brides such as Iphigenia and Antigone, to name but a few?

A major strength of Vasunia’s methodology lies in his practice of interrogating Greek texts from a cross-cultural perspective, introducing comparative Egyptian material to present illuminating contrasts between the historical reality of Egypt in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.E. and the Greek representations of Egypt from the same period. Vasunia does well to remind us again and again that the period of Persian rule that saw the most intense interaction of Greeks with Egypt is for various reasons remarkably absent in the Greek texts (e.g., 7, 244). In more specific examples, the author reminds us that although tragedy forecloses any possibility of a union between Greek and Egyptian, in fact mixed unions between Egyptians and Greeks were occurring in Egyptian towns such as Naucratis (34); a discussion of the political conceptualization of Greek space in Herodotus is offset by an illuminating treatment of the Egyptians’ conceptualization of their own space with the pharaoh’s architectural projects seen not as a Herodotean “transgression and violation” but as an “extension and replication” of natural boundaries (103-109); a section on Egyptian time argues for a more “complicated and interesting” ancient Egyptian approach to their own history than that suggested by Herodotus’ presentation of Egyptian temporality as “flat and static” in contrast to the dynamism of Greek time (126-127).

The same practice produces what is perhaps the most illuminating section of the book, an extended comparison between Greek (Platonic) and Egyptian conceptions of the written word in Chapter IV “Writing Egyptian Writing” (151-182). Here Vasunia shows that although Plato uses the Egyptian story of Theuth ( Phaedrus 274c-275b) to express his own anxieties about writing, in reality, Egyptian notions of orality and writing were radically different from the Platonic view. The Platonic view of language and meaning as distinct entities with the consequent danger of distortions between words and ideas contrasts with the Egyptian notion of “‘direct signification’ where the congruence between signs and things was maintained” (174-75). Subverting another Platonic distinction, he argues, is the Egyptian belief that the spoken word is often an extension of the written word, coterminous with writing, rather than an alternative to it (171). Furthermore, the nature of Egyptian monumental inscriptions subvert the Herodotean identification of writing and autocracy by often co-opting the reader into enacting the role of king and identifying with him. “Thus, where Greek sources point to tyrannical power, the Egyptian inscriptions do not quite correspond to the Greek implications of tyranny… The subjectivity enacted here is neither fully democratic, nor fully autocratic, but it indicates a self-identification on the part of the reader that the Greek sources fail adequately to grasp” (172).

Vasunia’s two chapters on Herodotus’ representation of Egyptian space and time impressively demonstrate this author’s deftness in laying bare the political implications of seemingly neutral abstractions and going beyond the “simple binarism” implicit in notions of self and other. In Vasunia’s fascinating discussion, Herodotus’ narrative with its series of Egyptian rulers who alter the country’s landscape framing space “to a geometrical design” and investing it “with the power of kings” (81) and thereby enslaving its inhabitants is read against the “larger ethnographic differentiation where the despotism and tyranny of barbarian lands stands in contrast to the freedom and openness of many Greek city-states” (77). In a subsequent chapter he argues that Herodotus represents Egyptian temporality as ancient and static so as to offer a contrast to his Athenian readers with the “present-oriented temporality of the Athenian democracy” and thus to construct an implicit contrast between two political systems: democracy and autocracy (112).

Vasunia’s book is brilliant and exciting, but his fidelity to the post-colonial mantra that “Empire follows Art” (11) too often seems excessive. So, for example, Herodotus sets Egypt under a masterful “all-encompassing panoptic gaze” presented in a discourse that serves “to naturalize the space of Egypt by flattening and denuding it” in a landscape “measured, packaged, quantified, stripped of its inhabitants, and lacking any aesthetic flavor” (101-103). Measuring the length and breadth of its space, the authoritative voice of Herodotus dominates the space and time of the country while putting it on display, winning the trust of his reader by quoting Egyptian archives, referring to interviews, invoking sources in a variety of ways, using a “rhetoric of mastery” that sets the author as the authoritative translator and observer of a non-Greek culture for his Greek reader (100-101; cf. 13) and which parallels the mastery over space and time that he ascribes to the pharaohs in his narrative (103, 13). By these stringent standards, almost every act of writing is an act of imperialism and even the most innocent Baedeker, not to speak of Vasunia’s own text, commits a “rhetoric of domination” over its subject. Perhaps the only difference is that most authors will not have an Alexander or Napoleon as yet unborn waiting in the wings to actualize their rhetoric, if indeed writing has as much power as post-colonial critics would impute.

Although Vasunia promises “not to reduce all my observations to the charge of ethnocentrism” (9) of which all ancient texts are guilty, his bottom line can be just that. For example, Isocrates’ Busiris is “a text that seldom troubles to grasp the realities of contemporary Egypt, that treats and handles ethnocentrism as if it were anti-ethnocentrism, that reeks of both condescension and arrogance, that retards rather than advances ethnic understanding, and that ultimately takes for granted the most pernicious of cultural stereotypes” (215). Plato’s use of Egypt as a vehicle for his own beliefs about language is tendentious and ethnocentric (181). Furthermore, Plato, like Hegel, is Eurocentric and his philosophical use of Egypt is a “strategy” for the containment of the older civilization (246). More generally, the Greek texts are faulted for “their failure to arrive at a sympathetic understanding of the otherness of Egyptian culture on its own terms,” as symptomized by “the neglect of Greek intellectuals to learn foreign languages” (182).4 In short, “the Greek treatment of Egypt is both deceptive and self-serving” (244).

Pronouncements such as these leave the reader wondering if Vasunia is perhaps asking too much of these ancient texts, judging them by modern sensibilities. We are not helped by the fact that Vasunia never explicitly lays out how an alternative text could or should read, while writing as if such an alternative were possible in antiquity. Was there a better, more ‘moral’ way for a writer like Herodotus to tell his readers about the Egyptians than to measure, count, and interview Egyptian priests? And if so what was it? Vasunia’s ancient Greeks are imperialists, his ancient Egyptian colonized subjects, long before Alexander set foot on the shores of Egypt.

Indeed, Vasunia’s own account of the motives and actions of Alexander in Egypt seems to undercut his thesis to some extent. It is asking a lot of a reader to accept an argument in which a historical event is anticipated by two hundred years of disparate texts without worrying about the “post hoc propter hoc” fallacy: Alexander conquered many peoples other than the Egyptians. Pace Vasunia, it is extraordinarily difficult to make a persuasive case for the extent to which Alexander’s invasion of Egypt was driven by his exposure to the Greek discourse on Egypt. In Alexander’s case, in fact, western Asia, the site of his hero Achilles’ exploits and of the more recent Persian Wars, seems, if anywhere, a more likely site for the intersection of literature and empire. Alexander’s detour to the South in the midst of his Persian campaign can be explained either by strategic reasons (Peter Green) or ideological motives (Vasunia) or both. His conquest of the country is a fact. But even Vasunia’s account of Alexander’s actions in Egypt ranges over the familiar terrain of the sensitivity and respect shown by Alexander to native Egyptian traditions (266), his foundation of a heterogeneous Alexandria, and his intellectual curiosity engendered by centuries of Greek speculation about the source of the Nile and the causes of its annual flooding. Surely, if the impetus for this conquest was Greek discourse on Egypt, this same discourse must be given its due in the conqueror’s remarkably sympathetic brand of imperialism in Egypt and his respectful treatment of the Egyptians. And so we are left with the question of how “pernicious” or “devastating” Greek discourse on Egypt actually was.

As for style, again recalling Bernal, Vasunia’s closely argued book goes down like a dense chocolate cake: so rich in ideas as to cause indigestion unless taken in small monitored portions, but certainly tempting. On occasion, the author gets carried away by his own rhetoric to the detriment of his argument and to the distress of his reader.5 In summary, Vasunia’s post-colonial theoretical engine drives a book that is at the same time exciting, brilliant, ideologically determined, and (sometimes) just plain wrongheaded.

Notes

1. Martin Bernal, Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization. Vol. I: The Fabrication of Ancient Greece 1785-1985 (New Brunswick, New Jersey 1987).

2. Edith Hall, “When is a Myth not a Myth? Bernal’s Ancient Model,” Arethusa 25.1 (1992) 181-201.

3. Froma I. Zeitlin, “Thebes: Theater of Self and Society in Athenian Drama,” 130-167 in Nothing to Do with Dionysus? Athenian Drama in Its Social Context, edited by J. J. Winkler and F. I. Zeitlin (Princeton 1990).

4. On one exception, see Ken Mayer, “Themistocles, Plutarch, and the Voice of the Other,” 297-304 in Plutarch y la Historia. Actas del V. Simposio Espangnol sobre Plutarch (Zaragoza 1997).

5. For example, in a discussion of Herodotus’ use of symmetry and inversion Vasunia writes: “While this approach [‘global binarism’] has some explanatory power, it is not enough to say that Herodotus’ spatializing discourse works to principles of symmetry and inversion. Interpreting Herodotus’ text in this way is useful to the degree that it lets us see some of his structuring technique but such an interpretation would inevitably lead us to a totalizing reading that would subsume all of the text within a dyad and would contravene an analysis the purpose of which is to examine the constitutive elements of a spatializing discourse. Without entering into the intentional fallacy, we can also state that in attributing this system to Herodotus’ text, we are coming close to repeating a rhetorical and thematic signification constructed by the author himself, and hence that we are subject to the manipulation of the text. Our notion that Herodotus uses a system of symmetry and inversion may be itself the mechanical elaboration of a controlling Herodotean trope. If the text does not begin to deconstruct at this point, at least the complications associated with these statements can easily be multiplied, and impel us into deep aporia” (98).

Source: https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2002/2002.08.32/

Molly Myerowitz Levine, Professor, Department of Classics, Howard University

I have not read Vasunia’s book, but from what I read in this review I agree with the criticisms of Pr. Levine.

It seems that Vasunia goes too far with his post-colonial agenda and his interpretation of the ancient Greek texts is anachronistic and unsympathetic, as he sees the Greeks and their literature just as the ancestors of modern Western colonialism and imperialism.

I remind here that the Greco-Egyptian interactions before Alexander were far more complex that a relation of progressive colonization of Egypt by the Greeks: the Saite Egypt was an imperial state which used Greeks mercenaries and merchants for the pursuit of its interests, Greeks already conquered by the Persians played a role in the Persian conquest of Egypt, Egyptian navy and troops participated in Xerxes’ invasion of Greece, Egyptian and Greeks fought together as allies during the Egyptian anti-Persian revolt of 460-454 BCE, Greek mercenaries and alliances played an important role in the defense of Egypt from the Persians during the period of the 30th- 28th dynasties (404-343 BCE). This is the historical and political context of most of the Greek literary production on Egypt in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, not anything similar to the first phases of the British colonialism in India. I remind also that Alexander’s victories and conquests were surprising events and it would be totally wrong to see all the Greek relations to Egypt during the different phases of Late Period as simple preliminaries of Alexander’s conquest of Egypt.

More particularly concerning Herodotus, not only Herodotean Classicists, but also Egyptologists specialized in Late Period Egypt have showed that Herodotus’ engagement and interaction with Egypt and Egyptian culture are genuine and serious, not ethnocentric distortions and exercises in intellectual colonization of a foreign people.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

What did Alexander’s soldiers think of him and the campaigns, towards the end? How do you think they felt about his death?

I think it varied a lot. There are several factors, depending on WHO, and when they joined the campaign.

By the time of his death, Alexander’s army consisted of veterans from his father’s army, younger soldiers who’d signed up when he left or joined as reinforcement at various points during his campaigns, Greek mercenaries hired at various points, as well as non-Macedonian/non-Greek soldiers from Asia, especially Persian contingents such as the 30,000 Epigoni, who stirred up such resentment among Macedonians. (Also, keep in mind that about half the Macedonian army remained in Macedonia to support Antipatros as regent, so they were not “Alexander’s men” to nearly the same degree.)

Alexander’s Persianizing presented a problem for traditional Macedonians (and Greeks). Whether he adopted some Persian court customs out of necessity, or ideology (or both), that didn’t sit well with many of his non-Asian followers.

We can’t forget that traditional Macedonians viewed themselves as superior, not only to the Persians and other “Asiatics,” but even to the Greeks, who they viewed as weak and divided. They were under the impression that they’d go over there, beat the crap out of the Persians, loot everything, and come home rich. They were nativists, and if there had been “Make Macedonia Great Again” red hats for them to wear, as Alexander increasingly added Persian-esque elements to the court, they’d have been marching around in them. Those who want to bitch about Alexander ignoring the wishes of his soldiers need to remember that. The wishes of his soldiers was either to take all the wealth and go home, or to rule Persia with an iron fist and milk everything they could, ala the Assyrians. Look how that ended for the Sargonids.

We’re told that on his deathbed, Alexander had a hole knocked in one wall so men could parade past, allowing him to say goodbye. (They came in through the door and out through the hole in the wall, it seems.) And the men came. He greeted and nodded to them, recognizing them. These were apparently the Macedonian troops who’d been with him for years. If they had mixed feelings about the Persianizing, they came to see him. Similarly, one reason not to call the Indian incident or Opis a “mutiny” is that mutinies end with the leader dead. They wanted him to turn around; they didn’t want to get rid of him. Beth Carney’s “indiscipline” is a better term. (I’ve also seen “insurrection” used, but like “mutiny,” I think it too strong.)

After his death, factions immediately developed and a lot of the Persian aspects of Alexander’s reign were jettisoned, including the Persian wives, with a couple notable exceptiosn: Seleukos and Peukestis, who kept them for obvious reasons (they were ruling over areas with large Persian populations). Most of the rulers in Asia Minor, Egypt, and Greece/Macedonia/Thrace returned to Greek/Macedonian wives, and their methods of rule were, at most, “Asian tinged,” rather than heavily influenced.

My sense is that most of his soldiers liked Alexander’s victories, and their new enormous wealth, but they didn’t like the Persians or Persianizing.

This is not especially surprising in the ancient world. Again, remember the VERY STRONG “anti-mixing” sentiment among Greeks.

Plato (et al.) argued the Athenians were MOST pure not only for being autochthonous (native to Attica/always there), but by not mixing with other Greeks due to Perikles’ citizenship law (had to have BOTH parents Athenian to be a citizen). That’s “double-purity,” ha. They didn’t have “barbarian blood,” and they weren’t immigrants to Attica, either! That gave them a leg up over even the Spartans, who could argue no-mixing, but were still immigrants, however far back.

(Whether ANY of that is true is completely irrelevant to what they believed. The Dorian invasion may be a myth, but it was one they accepted, just like they believed in the autochthonous origin of the Athenians.)

That demonstrates how concerned Greeks were with “mixing.” Even immigrants (metics, in Athens) were suspect; couldn’t be trusted to defend the homeland like a native-born son. A lot of those attitudes have transferred down through time (via Rome, then the Enlightenment) to fuel modern anti-immigrant and Purity ideologies.

And it’s not just Greeks. The Persians were the same. A glass ceiling existed in Persia. The king might marry women from everywhere…but only a pure Persian could be mother to the heir. Satraps might be concessions to keep the local peace, but only Persians could occupy the highest offices at court, including regional governors, etc. And don’t get me started on Egyptians, especially in the Bronze Age. Or the Romans later. LOL.

Ethnocentrism was simply How We See the World.

If we can’t make Alexander into Tarn’s “One World” advocate, he did stand against the Platonic-Aristotelian ideas that “mixing” was bad. In his case, it was driven by practicality—he had to rule a mixed empire and avoid constant rebellion (like the Assyrians had experienced with their hard-line Assyrianizing of provinces)—but also a little based on his experiences, which called into question the philosophical ideas of Plato, Aristotle, and Isokrates. I’m reminded of Caesar’s ideas about the Gauls, which diverged from the ideological philosophic notions of Seneca. Caesar avoided geographical determinism, preferring notions of diet and custom instead. Like Alexander, Caesar had pragmatic, boots-on-the-ground experience with the people he was writing about, not second- and third-hand ethnographic accounts that were more about stereotypes and literary topoi than actual reports.

Anyway, a lot of Alexander’s soldiers liked “the winning” (to sound Trumpesque), but not his attitudes towards “them furriners.” They were happy to jettison the more radical changes he’d made after his death.

#Alexander the Great#ancient Macedonia#ancient Greece#Greek ethnographic ideas#Greek ethnocentrism#Plato#Aristotle#ancient proto-racism#Macedonian soldiers#racism in the ancient world#asks

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not Freytag's pyramid~~.

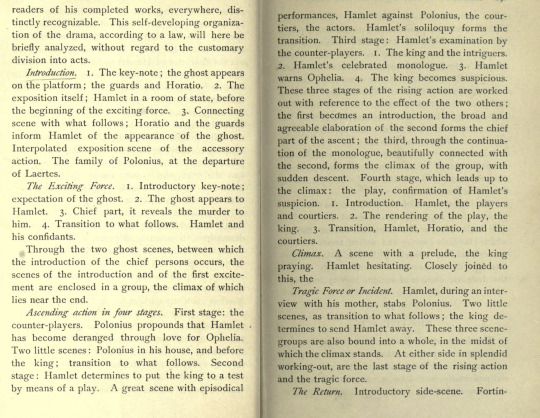

That's stolen from a corrupted version of Antigone's diagram.

Why do I know this one to be correct and it's on Wikipedia? Because I read the whole of and tortured myself for a week reading Freytag's book Dies Tecniks Des Dramas, which for the record, is terrible, terrible on women, racism, ethnocentricism and is pretty much a mind trip into reading pre-facist propaganda as it worships Wagner's Opera.

Freytag, much like Aristotle before him is basically worshipping and justfying Wagner's Opera which was pro-German propaganda. He said EVERYONE was inferior to German drama. He went on about this at length, going so far as saying English suck ass (in a lot, lot more words whole entire diatribes of this) and the ONLY decent English ever had in his estimation was Shakespeare.

In summary, he's what you call a grade A asshole. He thought women couldn't write for shit, which is why he chose Aristotle, and he got EVERYTHING about Greek plays wrong.

And then he called Christianity the greatest religion in the world... which is how he came up with that diagram, with wrong and assumed facts about Wagner's opera, Aristotle and Shakepeare.

He also didn't promote conflict.

BTW, that's also not Hero's Journey.

You're missing the misogynistic original version of it. C'mon, put in the part where Joseph Campbell was too lazy to look up Xiqu, and thought women were either there to sleep with the hero or support him, nothing else, and then got into an argument with one of his students that the female student created her own version, even though that too, is ethnocentric media imperialism.

Don't be lazy and just take the first diagram you can find on google, because those diagrams are WRONG. Read the original work and then reel like I did at how terrible these people are, and then QUESTION the foundation of if we should be adhering to thee story structures which were extensibly invented in the 20th century (because no one follows Aristotle, the 5-act which is NOT Shakespeare in origin and is kinda lost to history, honestly, and Freytag.). Or you could just read my long, long research into the origin here: https://kimyoonmiauthor.com/post/641948278831874048/worldwide-story-structures

I've spent what? 4-5 years trying to back trace this awful thing and getting pummeled by loads of racism, sexism, while the industry worships white cis (mostly het) abled men, while ignoring the contributions of women, People of color and other minorities about story structure and I, personally, don't think that's right. We need to restore the *toehr* people and their thoughts to their rightful places and say things like, "Discovery is a valid story driver." And qichengzhuanhe is super awesome and at least 10 times older than the supposed corrupted three act story structure, which isn't really any one person these days but the worst version of telephone game ever.

Does this mean the final diagram made up of all of these different people acting like authorities without citations is "useless" no, but knowing the history of stry structure itself, I think it empowering so you know you hae a *choice* and that choice is important.

Reading the original works gives you a sense of time and plae and how things can change over time, such as where did the development part come into play into story structure, who was arguing what, and should we question it? Give yourself empowerment.

Maybe the Conflict-filled three act story structure is far better for say... horror and thrillers since it gives everyone anxiety when done right, which as I point out is great for a capitalist society. But maybe realization, discovery, self discovery, etc are better for things like romance. OMG, he actually reads Natsume Soseki, I think I'm in love.

Maybe a morality tale needs to be in Sci-fi as it looks at political issues--how do you pull that off? Silas Mariner could help. Knowing that other story drivers and story structures exist is empowering to the average writer.

Plot structure btw, I found much later is also ethnocentric and probably a after-19th century idea.

Culture need not be static. And often culture lies to you. And in this case it's a big fat lie because it's mostly holding up men who hate women and other minorities and the question for everyone is... should we stand for that when the majority of the industry are women who don't hate everyone else? Do you want to go around saying how horrible Gertrude Stein is, or rag on Black people as being "savage" or just go full on racist and religiously intolerant by saying other story structures are not valid?

There's Chaistic, for example, which is used in Jewish lore. Why not have some fun and PLAY? Isn't that what creativity is for? And if by chance people feel threatened by this and goes all Highlander on you, "There can be only one." I have to point out oppressing and saying only white men are right about everything is a terrible way to conduct business. Also, for the love of what's Holy, and for the sake of artists DO CITATIONS. I know it's tradition to not do citations on writing advice, but damn, those white men gave me a headache. And people should get credit for their ideas and work.

I bother with citations and tell when I have a new idea and where my ideas come from because I have a ense of legacy, which, BTW, doubled after I did this project and all of the white men didn't do citations and everyone else did. The more privileged you are, the less you think you have to cite say, Octavia Butler? Screw you, white uncitation men. BTW, It's a trip to read Freytag back to back with Polti. I do cite Freytag for being an asshole in full, BTW.

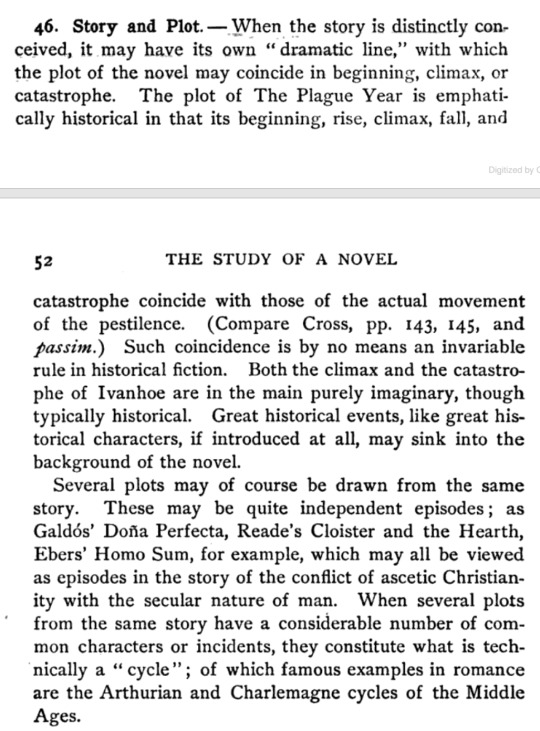

Let's talk about story structure.

Fabricating the narrative structure of your story can be difficult, and it can be helpful to use already known and well-established story structures as a sort of blueprint to guide you along the way. Before we delve into a few of the more popular ones, however, what exactly does this term entail?

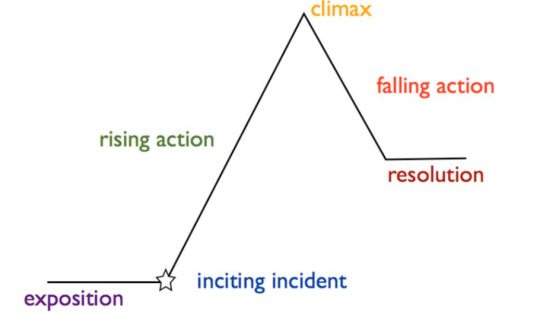

Story structure refers to the framework or organization of a narrative. It is typically divided into key elements such as exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, and serves as the skeleton upon which the plot, characters, and themes are built. It provides a roadmap of sorts for the progression of events and emotional arcs within a story.

Freytag's Pyramid:

Also known as a five-act structure, this is pretty much your standard story structure that you likely learned in English class at some point. It looks something like this:

Exposition: Introduces the characters, setting, and basic situation of the story.

Inciting Incident: The event that sets the main conflict of the story in motion, often disrupting the status quo for the protagonist.

Rising Action: Series of events that build tension and escalate the conflict, leading toward the story's climax.

Climax: The highest point of tension or the turning point in the story, where the conflict reaches its peak and the outcome is decided.

Falling Action: Events that occur as a result of the climax, leading towards the resolution and tying up loose ends.

Resolution (or Denouement): The final outcome of the story, where the conflict is resolved, and any remaining questions or conflicts are addressed, providing closure for the audience.

Though the overuse of this story structure may be seen as a downside, it's used so much for a reason. Its intuitive structure provides a reliable framework for writers to build upon, ensuring clear progression and emotional resonance in their stories and drawing everything to a resolution that is satisfactory for the readers.

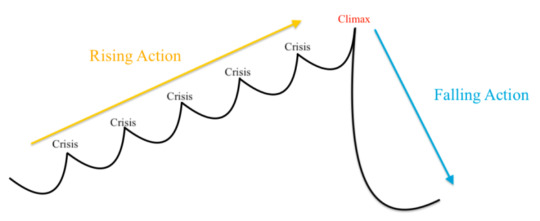

The Fichtean Curve:

The Fichtean Curve is characterised by a gradual rise in tension and conflict, leading to a climactic peak, followed by a swift resolution. It emphasises the building of suspense and intensity throughout the narrative, following a pattern of escalating crises leading to a climax representing the peak of the protagonist's struggle, then a swift resolution.

Initial Crisis: The story begins with a significant event or problem that immediately grabs the audience's attention, setting the plot in motion.

Escalating Crises: Additional challenges or complications arise, intensifying the protagonist's struggles and increasing the stakes.

Climax: The tension reaches its peak as the protagonist confronts the central obstacle or makes a crucial decision.

Swift Resolution: Following the climax, conflicts are rapidly resolved, often with a sudden shift or revelation, bringing closure to the narrative. Note that all loose ends may not be tied by the end, and that's completely fine as long as it works in your story—leaving some room for speculation or suspense can be intriguing.

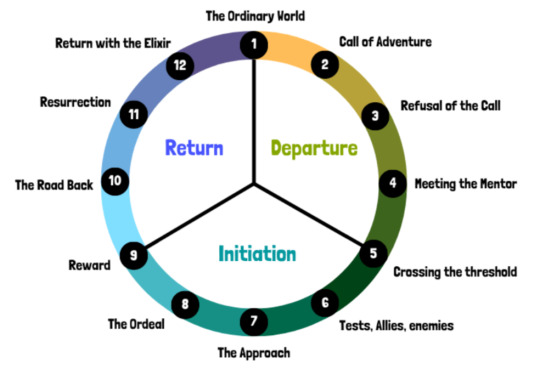

The Hero’s Journey:

The Hero's Journey follows a protagonist through a transformative adventure. It outlines their journey from ordinary life into the unknown, encountering challenges, allies, and adversaries along the way, ultimately leading to personal growth and a return to the familiar world with newfound wisdom or treasures.

Call to Adventure: The hero receives a summons or challenge that disrupts their ordinary life.

Refusal of the Call: Initially, the hero may resist or hesitate in accepting the adventure.

Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a wise mentor who provides guidance and assistance.

Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their familiar world and enters the unknown, facing the challenges of the journey.

Trials and Tests: Along the journey, the hero faces various obstacles and adversaries that test their skills and resolve.

Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero approaches the central conflict or their deepest fears.

The Ordeal: The hero faces their greatest challenge, often confronting the main antagonist or undergoing a significant transformation.

Reward: After overcoming the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, such as treasure, knowledge, or inner growth.

The Road Back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, encountering final obstacles or confrontations.

Resurrection: The hero faces one final test or ordeal that solidifies their transformation.

Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to the ordinary world, bringing back the lessons learned or treasures gained to benefit themselves or others.

Exploring these different story structures reveals the intricate paths characters traverse in their journeys. Each framework provides a blueprint for crafting engaging narratives that captivate audiences. Understanding these underlying structures can help gain an array of tools to create unforgettable tales that resonate with audiences of all kind.

Happy writing! Hope this was helpful ❤

#story structure#Freytag was an asshole#Freytag was a pre-Nazi fascist#Don't forget Fretyag was super racist#Campbell was racist and sexist. c'mon#Do citations

397 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greek myths: POC in the Legends

It's typical to find some ethnocentric Hellenic pagans insistent on the general lack of colour in their religion. The stories take place across the Greek islands and Italy, so obviously there can only be white heroes and gods in the myths, right? Perhaps it's time for these folks to have a history lesson.

The vague boundaries of Ancient Greece stretched, at the very least, from Macedonia to Rhodes, and housed hundreds of states, towns, cities and villages. Many of these settlements were close to continents such as Africa, where the Egyptians and Carthaginians (a Punic nation) lived. Apart from them, the Greeks and Romans also knew of and traded with the "Ethiopians" (Αἰθίοπες), which was a general term referring to Black people (from Αἴθω + Ὤψ, "Dark Face"). This closeness of different ethnicities meant that there would be some diversity of religious figures by virtue of cultural exchange.

Memnon (Μέμνων) was the demigod son of Tithonus and the goddess Eos, and was the king of Ethiopia. There was also his brother Emathion (Ἠμαθίων) who fought Heracles. Eurybates (Εὐρυβάτης) was Odysseus' "dark-skinned" (μελανόχροος) companion, and was honoured by him above his other comrades (Odyssey 19, Lines 246-249).

And to use a more well-known example: Andromeda (Ἀνδρομέδα), wife of Perseus, was the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, king and queen of Ethiopia. The legendary woman more beautiful than Aphrodite was Black. She and Perseus may also be one of the earliest examples of an interracial union in the Greek stories.

And to those who would object and say these figures are represented as white in sculptures and wall paintings, the divergence from the original textual sources is a simple result of interpretatio graeca. People will often render foreign persons or deities through the appearance and mannerisms of their own nation (e.g. old paintings of Jesus in Ethiopia and China showing him to be Ethiopian or Chinese), and in this case Black characters were filtered through a Greek and Roman lens.

The ancient Greeks and Romans saw skin colour as a designation of one's national origin, but not as a racial identifier. If you approached a Roman and told him the vikings were of the same "race" as him, he would be deeply offended. "Race" was formulated by European pseudoscientists in the 15th to 16th centuries to justify the barbaric things that were done to enslaved Africans, Indigenous peoples in the Americas, and later South Asians.

I as a white person am wholly comfortable, and also appreciative, of the presence of people of colour in my religion. They serve as a reminder of the universality of attributes such as heroism, strength, kindness, courage and valour. Virtue is not bound to one skin colour, and we are all fundamentally one race: the Human Race.

So don't let these pseudadelphoi (false siblings) stir discord and disunity in our communities. All are welcome in the Faith and to the graces of the gods, regardless of colour, sexuality, or gender identity.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

Austria is discount Germany, Azerbaijan is discount Turkey. "One nation, Two states." Both have a strongly mythologized history & nationalistic identity where their intellectuals and political leaders are (or were) placed on a pedestal. Both are (or were) committing war crimes/genocides (Herero, Namaqua, Jewish, & Roma people) & (Armenians, Assyrians, Pontics/Greeks). both have ripples that carry over today (Fascism, massacres, ethnocentrism, denialism). Azerbaijan is wilding Nagomo-Karbakh RN.

hey theres a lot to criticise germans over BUT theyre like among the best when it comes to acknowledging their horrific history and crimes at least during nazi germany 😩 not at all comparable to turkey for example, which afaik completely denies the genocide even happening

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perfect, no notes!

OP hit a grand slam with this one. I just want to point out some observations on why people seem to have a hard time understanding the themes of Greek mythology that I have personally encountered:

1) Greek words: As OP mentioned, a lot of times ancient mythology was an allegory and some names of the Greek gods are the literal personification of those concepts. Zeus isn't always kind because lightning isn't always kind. He can seem ruthless because lightning can be ruthless. In the Prometheus myth he is the one who decides if humans have fire or not because lightning causes fires and Zeus was probably believed to have given the first humans fire.

2) Local myths that have been re-organized: Sometimes the confusion stems from the fact that different city states and towns in the ancient world had their own local government running it and so myths varied from polis to polis like the death of Adonis being caused by Ares, Artemis or Apollo depending on the location or Hercules being an Olympian depending on the location. A lot of these locations also had tourism and depended on tourism as a valid source of income so they depended on their myth being different enough and hero focused to bring in tourists or people on a religious pilgrimage. Unfortunately as the Hellenistic and Roman periods had empires that blended all those cultures together but selected the favorite version among all of them (often Athenians but not always) I find that modern people have a hard time wrapping their heads around the concept that myths are wobbly, but I agree with OP that Zeus represents order in most ancient cultures that worshipped the Greek gods.

3) Evolution of the Gods: I also find that people have a hard time with the myths because they are older than writing, were originally oral (anyone who has ever played the game Telephone will get that variety will happen over time) and may have started in the Mycenaean period or even older but changed over time. For example in the Iliad Zeus mentions his war with Poseidon and that's because in the Mycenaean religion Poseidon was the original king of the gods, not Zeus. Artemis and Apollo were not twins and Artemis and Dionysus were originally the children of Demeter, this is why they both have ties to the wilderness and mother nature because they were originally rustic gods like Pan. So I find people often mix the gods and myths because they have changed over time.

4) Ancient culture vs Modern progress: The biggest misunderstanding is the ethnocentric way modern people view the ancient world. In anthropology ethnocentricity is the act of judging a culture based on your own culture's standards which ruins the understanding. Anthropologists try to judge the cultures based on the culture's own rules and standards to better understand why they do what they do. In the ancient world women were seen as property and didn't have the same rights modern women have. Kings were also oftentimes seen as directly connected to the gods and thus given "Divine birth" to rule. People see Zeus cheating and judge it based on today's standards whereas the ancient world saw it as a connection to Zeus and Zeus granting this king the right to lead because either he's a direct descendant or an ancestor was and praised their mother's beauty in the process because beauty was very important to the ancient Greeks and if a person was so beautiful to drive a god to procreate with them, then it was seen as high praise. So if they're being praised, why is it described as "rape?" That's because of the purity culture of the ancient world which discouraged women from seeming willing in order to give them a modest appearance. We don't know the true feelings of the women because they were not the main topic of the myth, their children were. Also, even if they seemed like they were consenting like the myth of Semele who is excited about being with Zeus but gets tricked by Hera, they couldn't be seen as actually consenting because they were viewed as property and thus the consent needed to come from their husband or father and most of the time the gods bypassed that consent. Any sexual act towards a woman by a god was seen as a violation of her father or husband but never her because she never had a say in her own life. They were captured by the god and the old word for captured would often be translated as raped. In the modern world this is thankfully different with sexual liberation helping women untangle from purity culture but the ancient world had its own rules and in order to better understand the myths, one must understand the ancient culture, rules and laws or else big misunderstandings will happen. For example, often times when humans in ancient history were seen as very exceptional, beautiful or brilliant to the point of seeming inhuman it was believed they were the secret love child of a god. This can be observed with Alexander the Great who was often seen as being the son of Zeus. Sidenote: Consent of a woman also didn't matter to the ancient Greeks because marriage was seen as a political union. This is also why Aphrodite is seen more as a type of madness that opposes Zeus/order instead of love in the way we understand it today. Love was not the priority in marriages and Aphrodite was seen more as a goddess of lust and then later Greeks and Romans started to explore her more and look at love differently but in the ancient oral myth world she was definitely seen as a menace that ruined arranged marriages and thus got in the way of order.

5) Allegories vs local legends and tragedy: As OP stated, the gods were a way for the ancient Greeks to understand the world around them. These myths were Mnemonics (named after Mnemosyne: goddess of memory) to tell the story of how something came to be or to remember when to water the crops or remember when the seasons change, etc. There is a myth of Orion lusting after and chasing the Pleiades because he's literally following them in the sky. The ancient Greeks were also comforted with the thought that if a person died young it probably meant they were loved by a god and taken. Local legends like the Spartan Prince Hyacinth who was said to have been tragically loved by Apollo, were said to have been chosen by the gods and so we have the "brides of Hades." These were young girls of marriageable age dying and being buried in their wedding dress and said to be marrying Hades. So there is a lot happening allegorically but when modern people encounter an ancient myth without the historical context they judge them in the same way they would judge full humans and forget the allegory.

6) Missing myths and cultural references: There are so many vases that reference mythos that were either never written or have yet to be found but well known or specific to their region. There are also a lot of ancient tragedies and comedies we have references to that have yet to be found or are incomplete or were purposefully disposed of like some of Sappho's work. Even if you know the information, you can't judge a culture based on small samples and echoes of preserved fragments. We are missing so many cultural, religious and historical references that it's hard to make a confident assessment on so much that is missing, but we try and might still get it wrong so some people who have done research might be using older resources that are now invalid due to new discoveries or old biases from researchers that are now contested, this is especially prevalent with 19th and 20th century research of the ancient world. So it's important to keep in mind that we might be getting information about the gods that might be outdated or littered in 19th/20th century biases which tended to see the gods in a more negative and human light.

Conclusion: The ancient myths are fascinating and fun but it's important to remember they are older than the Bible with concepts we have lost the meaning of due to various reasons but even in their own context the stories follow the pattern OP listed. I graduated studying this and will be going to a Master's program to study the archaeology of it, and I can tell you they are way more fascinating in their original culture and context than ethnocentric modern interpretation.

Another reminder that Greek mythology is always somehow symbolic, metaphorical, allegorical, since we are dealing with anthropomorphic personifications and other embodiments of cosmic powers.

For example: Demeter has sex with both Zeus and Poseidon. Something-something about the relationship of the Earth with the Sky and the Sea (or the celestial and chthonian powers). ESPECIALLY since these relationships are said to happen at the beginning of the world, in the primordial times during which the world settled itself for what it is now.

Herakles' wedding with Hebe, the personification of youth, checks in with when he becomes an immortal god (aka, an eternally young entity). What better way to symbolize a hero escaping the clutches of death than by him becoming the husband of the spirit of eternal youth?

Why is Hestia never leaving Olympus? Something-something about her being the literal personification of the hearth, which is at the center of the house/community and does not move.

Why is Ares getting his ass kicked by Athena? Because Athena is civilization, and Ares savagery, and in the Ancient Greek mindset intelligence, wisdom and craft will always be above brutality, bloodlust and random cruelty.

Do I need to spell it out that the myth of Persephone-Hades-Demeter is about the cycle of the seasons, and how the earth renews itself and brings back life after a time of death?

And I wonder why Ares' companions during his mass-slaughters are called Phobos, Deimos and Eris - Fear, Panic and Discord... Why would the goddess that breaks harmony and sows feuds and chaos be depicted as the close sister of the god of the ravages of war and of the brutality of conflicts, what a strange mystery!

And I can go on, and on, and on. Remember, the Greek gods aren't just super-heroes or wizards (that's more in line with more "humanized" mythologies, like the Irish or Nordic ones). They are embodiments of concepts and ideas, personifications of natural forces and cosmic powers, they are living allegories and fleshed metaphors. Zeus wields the lightning because he IS the lightning and thunder. Dionysos is both the bringer of joy and madness because he IS alcohol. Hades is both the name of the god of the dead, and of the realm of the dead. Hestia's name is literaly "hearth" in Greek, Hebe "youth", Nyx "night", Gaia "earth", Eros "desire". You can write "Eris met Helios at Okeanos' palace" or you can write "Strife encountered the Sun at the palace of Ocean" and that is the EXACT SAME THING!

[Mind you to limit the gods to being JUST allegories is also a mistake not to make. Greek deities are much more than just X concept or X idea... But one part of the myths will always be, down the line, some weather metaphor or some natural cycle motif]

#greek gods#hellenic polytheism#greek mythology#greek myths#ancient history#archaeology#scholars#drama in the research department

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Real History of the European 5-Act