#Graveur

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Drink more! Feel less!

Linoleum engraving - 2024

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Un des plus grand de l'art moderne

Hans Bellmer, 1959.

421 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forever young and famous - Aubrey Beardsley 1898-1972

burried in Menton (France) where he was staying, hoping to cure his tuberculosis - this collage is made by me and published on my Flickr gallery at the name of Kay Harpa.

1 note

·

View note

Text

#Soulas#Louis-Joseph Soulas#artiste#français#peintre#graveur#burineur#Les Amis de SOULAS#Hommage à Soulas

0 notes

Text

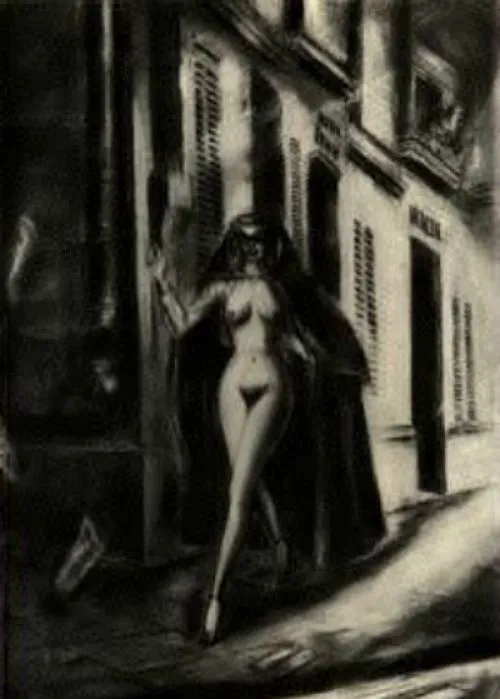

Premier illustrateur de Madame Edwarda, Kuniyoshi Kaneko

First illustrator of Madame Edwarda, Kuniyoshi Kaneko

1 note

·

View note

Text

Basílica (prueba de artista)

Linoleum engraving -2024

0 notes

Photo

21 graveurs japonais contemporains. Avec des biographies d'artistes et des exemples de travaux de Junji Amano, Yoshisuke Funasaka, Kiyoshi Hamada, Shoichi Ida, Shigeyuki Kawachi, Hideki Kimura, Kiyoko Kobayashi, Shigeki Kuroda, Ahira Matsumoto, Mayumi Morino, Kansuke Morioka, Tadyoshi Nakabayashi, Masako Nakayama, Fumihiko Nishioka, Tetsuya Noda, Kazuhiko Sanmonji, Harumi Sonoyama, Shigeru Tanaguchi, Yoko Yamamoto, Hodaka Yoshida et Hiroyasu Yoshike. Editeur : Cleveland, The Cleveland Museum of Art : 1979

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plaque en hommage à : Louis-Joseph Soulas

Type : Lieu de naissance

Adresse : 74 rue Saint-Marceau, 45100 Orléans, France

Date de pose : 25 novembre 2005 [source]

Texte : Ici est né le 1er septembre 1905 le Peintre-Graveur Louis-Joseph SOULAS, 1905-1954

Quelques précisions : Louis-Joseph Soulas (1906-1954) est un peintre-graveur français. Il étude les arts dès son enfance, se tournant vers la peinture et la gravure et contribue notamment à la fondation de l'association La Jeune Gravure contemporaine. Il est nommé directeur des Beaux-Arts d'Orléans peu avant le début de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, durant laquelle il est fait prisonnier par les Allemands. Rapatrié, il survit à la guerre et produit de nombreuses œuvres, en particulier illustrant en particulier des scènes de la Beauce et du Loiret.

#individuel#hommes#naissance#artistes#peintres#graveurs#france#loiret#orleans#datee#louis joseph soulas

0 notes

Text

BLOIS (Charles Paul Renouard, né à Cour-Cheverny le 5 novembre 1845 et mort à Paris le 2 janvier 1924, est un peintre, graveur et illustrateur français)

#BLOIS (Charles Paul Renouard#né à Cour-Cheverny le 5 novembre 1845 et mort à Paris le 2 janvier 1924#est un peintre#graveur et illustrateur français) (2)

0 notes

Text

It’s more fun when you see it in context at my local 7-11

WEEKLY SHONEN JUMP MAGAZINE ISSUE #39 FRONT COVER FEATURING RYOMEN SUKUNA AND ITADORI YUUJI IN HIGH QUALITY ⭐

#yes Shonen jump sits betwixt graveur magazines#I always chuckle when I see it#jujutsu kaisen#jjk#ryomen sukuna#itadori yuuji#weekly shonen jump magazine#wsj

213 notes

·

View notes

Text

Renaissance Fashion

I wrote this studying for my fashion history test next week, the information is from the books Costume and Fashion by James Laver and Back in Fashion by Giorgio Riello. If I have gotten any of the information wrong please comment.

The Renaissance, a period marked by the revival of Classical learning and wisdom. During this era, research, education, art, and philosophical thinking experienced a revival. The Renaissance celebrated the richness of human nature and creative abilities. A number of thinkers started seeking truth through facts and observations instead of relying on constructed religious speculations. The Renaissance started in Florence, Italy. The movement first expanded to other Italian cities, such as Venice, Milan, Ferrara, Bologna and Rome. Later spread to France during the fifteenth century and throughout western and northern Europe.

Italy vs Europe

Picture 1: Giovanna Tornabuoni, Domenico Ghirlando, 1488. Picture 2: Portrait of a lady, Roger van Der Weyden, c. 1455.

During the Renaissance, fashion varied significantly between different European regions. Italy contrasted sharply with the northern regions of Europe, which favored more elaborate and structured garments.

In the North, hairstyles often incorporated padded and stuffed hairstyles draped with veils. Italy, however, leaned towards more natural and relaxed hairstyles, avoiding the overly formal looks popular in the North. A universal trend was the plucking of the hairline, creating a higher forehead, considered a mark of beauty at the time. Women's headdresses went from looking like Gothic pinnacles into more angular shapes resembling Tudor windows. Sleeves were another distinguishing feature between Italian and Northern Renaissance fashion. In the North, close-fitting sleeves dominated. By contrast, Italian fashion favored sleeves that swelled out and featured decorative slashes, revealing the white chemise underneath. These sleeves were often detachable and intricately embellished. Renaissance footwear transitioned from the pointed toes of the medieval period to broader shapes.

Female vs male fashion early renaissance

picture 3: German landsknecht. Monogrammist IW (graveur), after Hand Rudolph Manuel Deutsch, 1547. An example in their extreme form of the slashings worn by the German mercenaries, but influencing male costume all over Europe.

During the 1500s, the trend of slashing—cutting slits into garments and pulling the lining through—became universal across Europe, though it was more restrained in women’s fashion compared to men’s.

Picture 4: Francis I of France, early sixteenth century Picture 5 & 6: Portrait of Anna Jacob Lösch Nothafft, Hans Schöpfer, 1568 (LEFT) and Jane Seymour, c. 1566-7, Holbein (RIGHT) . These two picture shows the contrast between the German and English modes.

Women’s dress adhered to a more modest and reserved aesthetic than their male counterpart. Renaissance skirts were more decorated than in previous reigns, showcasing intricate embroidery, appliqué, and other forms of ornamentation. Over the kirtle which consisted of a skirt and bodice sewn together. Over the kirtle, women wore the gown, a structured yet elegant piece that fell in graceful folds to the ground. The bodice was fitted tightly at the waist, emphasizing the wearer’s figure, while the arms, once closely tailored, grew larger and more voluminous as the century progressed. The neckline of women’s dresses was typically square and low, accentuating the shoulders and collarbone while remaining relatively modest compared to male styles of the time. The use of fur—particularly favorable was lynx, wolf, and sable—further emphasized the luxurious nature of these garments.

In early Renaissance fashion, the primary male garment was the doublet, which extended to the knee and featured a front opening that displayed the codpiece. The sleeves grew wider and were often paned or slashed, with some styles including double sleeves. The double was made from materials like velvet, satin, and cloth of gold. Footwear transitioned to a broad shape known as "duck bill" shoes, with flat heels and leather or cork soles. These shoes were made from leather, velvet, or silk, further emphasizing the rich textures of the time. Hats, both indoors and outdoors, were soft low bonnets that complemented the overall attire. Men typically wore their hair long, and during Henry VII’s reign, clean-shaven faces were in vogue. Middle-class fashion was less extravagant than what was worn at court. A common garment was the schaube, a sleeveless overcoat similar to a cassock, which was popular among scholars and intellectuals, including Martin Luther.

Values

During the early Renaissance, there was a shift away from the abundance and profusion of colors and materials. Ostentation and modesty were not necessarily opposites but acted as opposing forces within a broader struggle—between the desire to stand out and the wish to blend in. In sixteenth-century Italy, both of these concepts underwent significant transformation. Modesty began to be viewed more positively, seen as a form of restraint and self-discipline. The value of a gentleman no longer hinged on wearing luxurious fabrics or possessing expensive objects, but on education and personal conduct. Dark colors, especially black, became the preferred choice, symbolizing dignity and decorum. Black emerged as both the color of the court and a symbol of Protestant reform.

Dress and accessories were essential for demonstrating manners and propriety, and it was expected that everyone dress according to their age and social status. Culture and education became fundamental markers of refinement. A gentleman should open the door for a lady, speak politely, and exercise moderation with food and drink. Dress was therefore only one aspect of a broader set of behaviors that we now call etiquette. For instance, a man needed to know when to wear his hat as a sign of social standing and when to remove it. According to the German sociologist Norbert Elias, this marked a pivotal social change over the last few centuries, leading to the creation of a society that was not entirely natural but socially constructed.

Black vs Colors

In the 16th century, upper-class fashion was initially dominated by vibrant colors, with German influence leading the trend. However, by the mid-century, the personal taste of Emperor Charles V ushered in a shift toward Spanish fashion, characterized by tight-fitting, dark-colored garments, especially black. Even during conflicts between England and Spain, Spanish influence persisted, impacting both color and style. This was evident in the trend of bombas, which was used to stuff doublets and hose, which naturally made waists appear smaller, and the effect was increased by the use of tight lacing. Knitting, introduced during this period, allowed for tighter-fitting leg coverings, adding to the stiff, structured look of men’s fashion. The short breaches exposed a lot of legs.

Black also became the preferred color of the deeply Catholic Spanish court. Between the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, Italy set fashion trends for the rest of Europe. Emperor Charles V admired all things Italian, a trend that continued into the second half of the sixteenth century under Catherine de’ Medici. During her reign, it was said that men dressed in Italian fashion. Italy was already a model for European fashion long before. When Mary Tudor married the Spanish king Philip II, some Spanish elements seeped into English fashion. However, after Mary’s death, Elizabeth I displayed a strong aversion to anything Spanish. While the Spanish court favored black, the Virgin Queen preferred pastels.

Ruff and Cleanliness

One of the most iconic fashion elements of this era was the ruff—a highly structured collar worn by both men and women as a symbol of aristocratic privilege. Initially introduced in France and popularized by Catherine de’ Medici, the ruff quickly evolved into a statement of wealth and status, becoming larger and more elaborate over time. The ruff was not just a fashion accessory; it was a marker of hierarchy. For women, the Elizabethan compromise involved leaving the front of the ruff open to reveal the bosom, while gauze wings at the back of the head enhanced their feminine allure.

The intricate design of large ruffs and equally ornate cuffs served another purpose: to restrict movement. This sent a clear message that the wearer was above manual labor and could afford to employ servants. Maintaining these garments required extensive labor, and the pristine whiteness of the linen became a sign of both personal hygiene and moral virtue. Up until the mid-eighteenth century, personal cleanliness was judged not by the cleanliness of one’s body but by the state of one’s attire. It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that handwashing became common, with widespread practice only emerging in the nineteenth century.

Late Renaissance Fashion

The rigidity in men’s fashion was even more pronounced in women’s clothing. The stomacher, a stiffened panel in the front of the bodice, was reinforced with buckram or pasteboard and secured with a busk. The skirt was enlarged with a farthingale, a hoop skirt that created a structured, conical shape. The Spanish farthingale (1545) featured hoops of wire, wood whalebone, growing larger toward the bottom, and was soon worn by all women except the working class. The French farthingale (1580) was more of a court garment, rather similar to the Italian made of whalebone farthingale worn tilted back with cushions, achieving widths of up to 48 inches. Aside from the farthingale, the principal garment for women was the gown, which fell in folds from fitted shoulders and exposed the dress underneath through a gap in the front. Sleeves were puffed and ended at the elbows to reveal decorative undersleeves. Women also wore coats, frocks, cassocks, as well as cloaks and a garment known as "safeguard" for traveling.

Men’s fashion continued to be centered around the doublet, often paired with a jerkin or sleeveless jacket. The cloak was a necessary garment and was shorter than previous generations, it was originally a riding cloak but became a key wardrobe item, worn both indoors and outdoors. It was made from rich materials, the fashionable man required tree cloaks, one for the morning, one for the afternoon and one for evening. Men also wore a cassock, a hip-length jacket, a gabardine, a long overcoat, and the mandilion, a loose jacket with hanging “coat” sleeves.

Footwear included rounded shoes that began to adopt heels by the end of the century, with pumps and slippers for indoor wear. Boots, initially designed for riding, became popular for everyday use, even indoors. Hats also played a significant role in Renaissance fashion. Men adopted the copotain, a high-crowned conical hat, and Elizabethan gallants typically wore their hats at an angle or on the back of the head. Women began wearing smaller hats initially for riding and travel but gradually integrated them into everyday wear. Queen Elizabeth set the trend of dyeing hair red, prompting many women to use false hairpieces to achieve the desired look.

Gender

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, clothing was heavily gendered. During the Renaissance, clothing was believed to have the power to shape and transform gender. Gender was seen as a fluid category, and it was thought that a man could be transformed into a woman and vice versa by wearing the other gender's clothing. This concept was particularly evident in theater, where male actors played female roles. Fashion was not only a means of differentiating the genders but also of defining their relationship. Clothing is and was used as a tool of seduction, whether to reveal or conceal body parts and emphasize curves to attract the opposite sex (or sometimes one’s own). Today, legs are considered one of the most attractive parts of the female body. Yet, just a few centuries ago, legs were not viewed as an erogenous area for either gender. Instead, they symbolized power, not sexual prowess.

#history#fashion#fashion history#renaissance#16th century#15th century#renaissance fashion#historical fashion

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Triple portrait du cardinal de Richelieu.

Philippe de Champaigne, peintre et graveur, 1602-1674

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

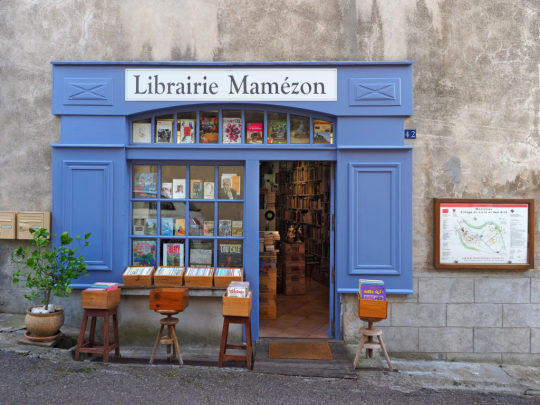

Montolieu est l’étape idéale pour les amoureux du livre

Montolieu (Aude) constitue une agréable escapade à quelques kilomètres de Carcassonne. Ce « Village du Livre & des Arts » rassemble 17 librairies et a séduit de nombreux écrivains par son charme. L’occasion d’une belle balade littéraire dans les rues du bourg.

C'est l'un des 8 villages du livre recensés en France. On y trouve des libraires de livres anciens et d'occasion mais aussi des professionnels des arts et des métiers du livre : relieurs, doreurs, graveurs, calligraphes, enlumineurs, fabricants de papier, imprimeries artisanales, éditeurs.

Dans les 17 librairies du village, on trouve principalement des livres d'occasion, avec du vécu… une histoire. Certaines sont spécialisées en livres jeunesses ou encore en littérature anglaise : il y en a pour tous les goûts.

Après avoir visité Carcassonne et sa fameuse Cité médiévale, une étape par Montolieu (Aude), charmante commune située à une quinzaine de kilomètres, s’impose. Il s’agit d’un « Village du Livre & des Arts », autrement dit un bourg rural où sont installés des librairies et des commerces d’artisanat autour du livre.

Riche d’une longue histoire, puisque occupé depuis la Préhistoire, Montolieu est devenu un village du livre en 1990, à l’initiative de Michel Braibant, relieur belge installé à Carcassonne, explique l’office du tourisme du Grand Carcassonne. Son rapport avec les écrivains est toutefois plus ancien encore : le village en a inspiré beaucoup, comme l’autrice Anna Gavalda, qui a vécu à Montolieu quelques années.

Au total, aujourd’hui, cette commune de 800 habitants compte 17 librairies de livres anciens, neufs ou d’occasion. « Certaines librairies ont justement des spécialités (BD, jeunesse, art, revues, journaux anciens…) », détaille l’office du tourisme. Les visiteurs peuvent aussi arpenter les 15 galeries ou ateliers d’art du village. Le bourg dispose par ailleurs d’un Musée des Arts & Métiers du Livre, où il est notamment possible de s’initier aux arts graphiques.

Mais plus généralement, ce bourg pittoresque est l’occasion d’une agréable balade. Au détour de ses ruelles fleuries et de ses maisons anciennes, il est possible de découvrir l’église Saint-André, un édifice du XIVe siècle classé aux monuments historiques, l’ancienne manufacture royale de draps, ou encore la chapelle Saint-Roch, qui offre un magnifique panorama sur les environs.

Situé sur les contreforts de la Montagne noire, au beau milieu des vignes, Montolieu ouvre sur de nombreux itinéraires de randonnée dans les gorges de l’Alzeau et de la Dure, avec ses ponts et ses moulins. « Oliviers, cyprès, variétés de cactus et arbustes fleuris mettent sublimement en beauté le paysage », assure l’office de tourisme.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonyme, graveur

Creative Commons Zero, Public Domain Dedication

Le Roi de Deniers, GDUT10889.jpg Copy

[[File:Le Roi de Deniers, GDUT10889.jpg|Le_Roi_de_Deniers,_GDUT10889]]Copy

between 1650 and 1700

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Portrait du Graveur Emile Laboureur" sculpture de Chana Orloff en bois (1921) au sein de “La Piscine” de Roubaix - Musée d'Art et d'Industrie André Diligent - de l'architecte Albert Baert (1927-32), octobre 2024.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Couverture du magazine Judge, 3 janvier 1925 par John Held Jr. (1899-1958) dessinateur, illustrateur, graveur, sculpteur et auteur américain. - source Cristina Ardelean.

6 notes

·

View notes