#Goldman Environmental Prize

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Excerpt from this story from Yale Environment 360:

For nearly a decade, Nonhle Mbuthuma has traveled with a bodyguard. The founder of the Amadiba Crisis Committee — a local group formed to fight a proposed titanium mine along South Africa’s Wild Coast — Mbuthuma has long had the support of many in rural Pondoland’s Xolobeni community. But opponents have demonized her as an arch enemy of all economic development, and some have been encouraged to believe that if Mbuthuma “disappeared,” they would get rich.

Eight years ago, Mbuthuma’s activist colleague Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe, who opposed the mine, was shot dead outside his home by two men dressed as police officers. (Neither assailant has been caught.) Mbuthuma was also a target that day. Amadiba succeeded in halting construction of the mine, and Mbuthuma, 46, has continued working to protect this highly biodiverse region and the traditional culture of the Mpondo people.

This week, Mbuthuma, and her colleague Sinegugu Zukulu, won a Goldman Environmental Prize for their recent efforts to prevent Shell Oil from prospecting along the Wild Coast. As the activist headed to San Francisco to pick up her award, she spoke via Zoom with Yale Environment 360 about Pondoland, plans for its future development, and continuing threats to her life.

Yale Environment 360: Tell me about your struggle with Shell Oil.

Nonhle Mbuthuma: When we heard in late 2021 that Shell wanted to do seismic blasting off the coast, it was like someone put a bomb to our chest. These waters are precious, with rich ocean currents and reefs feeding whale calving grounds and fisheries. That water is part of us. We have cooperatives that do environmental fishing, using rods rather than nets that wipe out everything. But the ocean is also a sacred place. According to our traditions, our ancestors reside in the ocean. We have a right under our country’s constitution to practice our culture, and that requires protecting our waters. So we decided to fight in the courts.

The government had already given Shell permission to start seismic blasting. Shell is a big company with a lot of money, but we said that they are not bigger than our livelihoods and culture. We mobilized our communities to collect information to explain why the ocean is so important to us. We were backed by protests all over the country.

Even as the surveying began, the high court ruled in our favor. The judges said the permit to do the surveys had been granted unlawfully because the government had not considered the impact on our livelihoods and culture and because Shell did not consult the community, which is a requirement of our constitution. But Shell and the government have decided to appeal the judgment.

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Winning what’s been called the ‘Green Nobel’ an Indian environmental activist has been recognized for saving a 657 square-mile forest from 21 coal mines.

From the New Delhi train station to high-end hotels to the poorest communities, virtually no one in India is free from periodic blackouts. As part of the Modi regime’s push for a developed and economically dominant India, power generation of every sort is being installed in huge quantities.

GNN has reported this drive has included some of the world’s largest solar energy projects, but it also involves coal. India is one of the largest consumers of coal for electricity generation, and Hasdeo Aranya forests, known as the “Lungs of Chhattisgarh,” are known to harbor large deposits.

The state government had been investigating 21 proposed coal mining blocks across 445,000 acres of biodiverse forests that provide crucial natural resources to the area’s 15,000 indigenous Adivasi people.

Along with the Adivasi, tigers, elephants, sloth bears, leopards, and wolves, along with dozens of endemic bird and reptile species call this forest home. It’s one of India’s largest intact arboreal habitats, but 5.6 billion metric tons of mineable coal threatened to destroy it all.

Enter Alok Shukla, founder of the Save Hasdeo Aranya Resistance Committee, which began a decade ago advocating for the protection of Hasdeo through a variety of media and protest campaigns, including sit-ins, tree-hugging campaigns, advocating for couples to write #savehasdeo on their wedding invitations, and publishing a variety of other social media content.

Shukla also took his message directly to the legislature, reminding them through news media coverage of their obligations to India’s constitution which enshrines protection for tribal people and the environments they require to continue their traditional livelihoods.

Beginning with a proposal to create a single protected area called Lemru elephant reserve within Hasdeo that would protect elephant migration corridors and cancel three of the 21 mining proposals, Shukla and the Adivasi began a 160-mile protest march down a national highway towards the Chhattisgarh state capital of Raipur.

They hadn’t even crossed the halfway mark when news reached them that not only was the elephant reserve idea unanimously agreed upon, but every existing coal mining proposal had been rejected by the state legislature, and all existing licenses would be canceled.

“We had no expectations, but the legislative assembly voted unanimously that all of the coal mines of Hasdeo should be canceled, and the forest should be saved,” Shukla says in recollection to the Goldman Prize media channel.

“That was a very important moment and happy moment for all of us.”

Shukla shares the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize with 5 other winners, from Brazil, the US, South Africa, Australia, and Spain."

youtube

-via Good News Network, May 20, 2024. Video via Goldman Environmental Prize, April 29, 2024.

#forests#india#conservation#deforestation#conservation news#goldman prize#biodiversity#coal mining#coal#climate action#climate hope#fossil fuels#environmental issues#indigenous#human rights#adivasi#nature reserve#hasdeo#good news#hope#hope posting#Youtube

290 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meet the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize Winners

Alok Shukla from India, Andrea Vidaurre from the U.S., Marcel Gomes from Brazil, Murrawah Maroochy Johnson from Australia, Teresa Vicente from Spain, and Nonhle Mbuthuma and Sinegugu Zukulu from South Africa.

This year’s winners include two Indigenous activists who stopped destructive seismic testing for oil and gas off the Eastern Cape in Africa, an activist who protected a forest in India from coal mining, an organizer who changed California’s transportation regulations, a journalist who exposed links between beef and deforestation in Brazil, an activist who blocked development of a coal mine in Australia, a professor of philosophy of law who led a campaign that resulted in legal rights to an ecosystem in Spain.

“There is no shortage of those who are doing the hard work, selflessly. These seven leaders refused to be complacent amidst adversity, or to be cowed by powerful corporations and governments,” John Goldman, president of the Goldman Environmental Foundation, said in a statement. “Alone, their achievements across the world are impressive. Together, they are a collective force—and a growing global movement—that is breathtaking and full of hope.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

---

For the Maya, the honey bee is more than an insect. For millennia, the tiny, stingless species Melipona beecheii -- much smaller than Apis mellifera, the European honey bee -- has been revered in the Maya homeland in what is now Central America. Honey made by the animal the Maya call Xunan kab has long been used in a sacred drink, and as medicine to treat a whole host of ailments, from fevers to animal bites. The god of bees appears in relief on the walls of the imposing seacliff fortress of Tulum, the sprawling inland complex of Cobá, and at other ancient sites.

Today, in small, open-sided, thatched-roof structures deep in the tropical forests of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, traditional beekeepers still tend to Xunan kab colonies. The bees emerge from narrow openings in their hollow log homes each morning to forage for pollen and nectar among the lush forest flowers and, increasingly, the cultivated crops beyond the forests’ shrinking borders. And that is where the sacred bee of the Maya gets into trouble.

---

In 2012, the Mexican government granted permission to Monsanto to plant genetically modified soybeans in Campeche and other states on the peninsula without first consulting local communities. The soybeans are engineered to withstand high doses of the controversial weedkiller Roundup; multiple studies have shown exposure to its main ingredient, glyphosate, negatively impacts bees, including by impairing behavior and changing the composition of the animals’ gut microbiome. Though soy is self-pollinating and doesn’t rely on insects, bees do visit the plants while foraging, collecting nectar and pollen as they go. Soon, Maya beekeepers found their bees disoriented and dying in high numbers. And Leydy Pech found her voice.

A traditional Maya beekeeper from the small Campeche city of Hopelchén, Pech had long advocated for sustainable agriculture and the integration of Indigenous knowledge into modern practice. But the new threat to her Xunan kab stirred her to action as never before. She led an assault on the Monsanto program on multiple fronts: legal, academic, and public outrage, including staging protests at ancient Maya sites. The crux of the legal argument by Pech and her allies was that the government had violated its own law by failing to consult with Indigenous communities before granting the permit to Monsanto. In 2015, Mexico’s Supreme Court unanimously agreed. Two years later, the government revoked the permit to plant the crops.

---

As Pech saw it, the fight was not simply about protecting the sacred bee. The campaign was to protect entire ecosystems, the communities that rely on them, and a way of life increasingly threatened by the rise of industrial agriculture, climate change, and deforestation.

“Bees depend on the plants in the forest to produce honey,” she told the public radio program Living on Earth in 2021. “So, less forest means less honey [...]. Struggles like these are long and generational. [...] ”

---

Headline, images, captions, and all text by: Gemma Tarlach. “The Keeper of Sacred Bees Who Took on a Giant.” Atlas Obscura. 23 March 2022. [The first image in this post was not included with Atlas Obscura’s article, but was added by me. Photo by The Goldman Environmental Prize, from “The Ladies of Honey: Protecting Bees and Preserving Tradition,” published online in May 2021. With caption added by me.]

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Colombia Day 1- Prince Harry and Meghan, The Duke and Duchess of Sussex have commenced their visit to Colombia with a memorable and heartfelt welcome from Vice President Francia Márquez and her partner, Rafael Yerney Pinillos.

Known for her fierce advocacy for environmental justice and human rights, Vice President Márquez is a champion for marginalized communities and a defender of Colombia’s natural heritage. Her work has garnered international acclaim, including the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, a testament to her dedication and impact.

In her official residence, Vice President Márquez hosted the couple for a formal audience. Over coffee, tea, and delicious pan de bono—a traditional Colombian cheese bread—the Vice President shared her vision and love for Colombia, passion for mental health and devotion to preventing online harms. (via sussex.com) (8/15/24)

#harry and meghan#meghan and harry#the sussexes#meghan markle#duchess of sussex#prince harry#duke of sussex#duchess meghan#duke and duchess of sussex#princess meghan#meghan the duchess of sussex#meghan duchess of sussex#royal family#british royals#colombia

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Friday is Indigenous Peoples Day in Brazil, and tribal leaders and activists used the occasion to criticize the left-wing government of Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva for falling short on promises to safeguard native land rights.

On Thursday, the Brazilian government announced the demarcation of Aldeia Velha, land of the Pataxó people, in the northeastern state of Bahia, as well as the territory of the Karajá people in Cacique Fontoura, Mato Grosso.

"Since the beginning of the current government, 10 areas have been regularized out of a total of 14 routed for approval," the government said in a statement. "The act reaffirms the focus of the federal government on the protection and respect of Indigenous peoples."

However, Indigenous peoples were anticipating the demarcation of six new territories. Lula acknowledged their disappointment.

"I know you are apprehensive and expected the demarcation of six Indigenous lands. But now we only announce two. And I'm being real with you," he said.

"Some of this missing land is occupied either by farmers or peasants," the president explained. "We cannot arrive without giving these people an alternative. Some governors asked for time to resolve, in a negotiated manner, the eviction of these territories so that we can demarcate them."

"The definition of these lands is already ready. What we do not want is to promise you today, and tomorrow you read in the newspaper, that a contrary decision was made," Lula added. "The frustration would be greater."

But the frustration was already there—and growing.

"This is revolting for us Indigenous peoples to have had so much faith in the government's commitments to our rights and the demarcation of our territories," Alessandra Korap Munduruku, a member of the Munduruku people and a 2023 winner of the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, told Amazon Watch in a statement published Friday.

"We hear all of these discussions about environmental and climate protection, but without support for Indigenous peoples on the front lines, suffering serious attacks and threats. Lula cannot speak about fighting climate change without fulfilling his duty to demarcate our lands," she added.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Most of these multinational corporations that come to the South, to the Global South, are coming from the Global North. The majority of the shareholders are in the Global North. You see, the best scenario I can paint to you is that it's like people in the North are letting their dogs out to go and cause chaos out there in the Global South. And we are supposed to fend for ourselves, trying to keep these dogs that are coming and are disrupting our lives and our livelihood. But the real beneficiaries of these oil giants are the shareholders in the North. It should not be like that. We should all be working together to protect and to ensure that this planet remains livable, not just for us, but for the future generations as well.

— Sinegugu Zukulu, recipient along with Nonhle Mbuthuma of the 2024 Goldman Environmental Prize for Africa

#sinegugu zukulu#Nonhle Mbuthuma#south africa#climate change#shell oil#thought the dogs were an apt metaphor#i work in climate#fuck shell

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

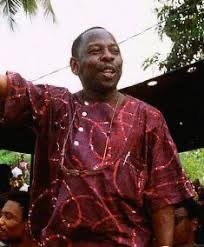

Kenule Beeson “Ken” Saro-Wiwa (October 10, 1941 – November 10, 1995) was a Nigerian writer, television producer, environmental activist, and winner of the Right Livelihood Award for “exemplary courage in striving non-violently for civil, economic, and environmental rights” and the Goldman Environmental Prize. He was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority in Nigeria whose homeland, Ogoniland, in the Niger Delta, has been targeted for crude oil extraction since the 1950s and which has suffered extreme environmental damage from decades of indiscriminate petroleum waste dumping. Initially as spokesperson, and then as president, of the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People led a nonviolent campaign against environmental degradation of the land and waters of Ogoniland by the operations of the multinational petroleum industry, especially the Royal Dutch Shell company. He was an outspoken critic of the Nigerian government, which he viewed as reluctant to enforce environmental regulations on the foreign petroleum companies operating in the area.

At the peak of his non-violent campaign, he was tried by a special military tribunal for allegedly masterminding the gruesome murder of Ogoni chiefs at a pro-government meeting, and hanged by the military dictatorship of General Sani Abacha. His execution provoked international outrage and resulted in Nigeria’s suspension from the Commonwealth of Nations for over three years. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“We have a duty to our grandparents, our parents, who gave us this work to do,” says Alexandra Narváez, 33, the first woman to lead the A’i Cofán Indigenous guard and winner of the 2022 Goldman environmental prize.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indigenous Amazon Activist Among Prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize Winners

When Alessandra Korap was born in the mid-1980s, her Indigenous village nestled in the Amazon rainforest in Brazil was a haven of seclusion. But as she grew up, the nearby city of Itaituba, with its bustling streets and commercial activity, crept closer and closer.

It wasn’t just her village feeling the encroachment of non-Indigenous outsiders. Two major federal highways paved the way for tens of thousands of settlers, illegal gold miners and loggers into the region’s vast Indigenous territories, which cover a forested area roughly the size of Belgium.

The influx posed a grave threat to Korap’s Munduruku people, 14,000-strong and spread throughout the Tapajos River Basin, in Para and Mato Grosso states. Soon illegal mining, hydroelectric dams, a major railway and river ports for soybean exports choked their lands — lands they were still struggling to have recognized.

Korap and other Munduruku women took up the responsibility of defending their people, overturning the traditionally all-male leadership. Organizing in their communities, they orchestrated demonstrations, presented compelling evidence of environmental crime to the Federal Attorney General and Federal Police, and vehemently opposed illicit agreements and incentives offered to the Munduruku by unscrupulous miners, loggers, corporations, and politicians seeking access to their land.

Korap’s defense of her ancestral territory was recognized with the Goldman Environmental Prize on Monday. The award honors grassroots activists around the world who are dedicated to protecting the environment and promoting sustainability.

Continue reading.

#brazil#brazilian politics#politics#environmentalism#environmental justice#indigenous rights#activism#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just stop oil?

In Ecuador we have the opportunity to do just that. My country could be the first to limit fossil fuel extraction through direct democracy. Can you imagine a world where people peacefully choose not to destroy the world? Can you imagine a future where people decide to protect the future? Can you imagine a present where we decide to leave the oil in the ground? Such a decision would not only allow life to continue to flourish in Yasuní, it would also create a precedent and an inspiration for others to make similar choices: to leave the gold dust inside the mountain, to leave the trees standing, to leave the rain in the aquifers and the rivers.

Courtesy: the Guardian Newspaper: Nemonte Nenquimo is a Waorani leader and winner of the Goldman environmental prize #juststopoil

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

“M100 - Leydy Pech”

2024 - Painted intervention & illustration design

Leydy Pech "the guardian of the bees" (Hopelchén, Campeche, 1965) is a Mexican beekeeper and activist of Mayan origin. In 2020 she was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize for her work against the planting of genetically modified soybeans in the Yucatan Peninsula.

This intervention was part of the call for M100 (a hundred women artists depicting a hundred women who changed history in Mexico). The painting is exhibited in the Alameda in Qro. Mx.

#illustration#illustrators on tumblr#artists on tumblr#women in history#international women's day#women in art#save the bees#bees#intervention

0 notes

Text

Murrawah Maroochy Johnson

Murrawah Maroochy Johnson è l’attivista ambientalista aborigena che ha vinto il Goldman Environmental Prize 2024, per la storica vittoria ottenuta contro la miniera di carbone di Waratah nel Queensland, in Australia.

Con determinazione e grazie alla profonda connessione con la sua eredità culturale, la giovane attivista ha guidato, nel 2021, una causa che ha portato, l’anno successivo, alla negazione del permesso della miniera che avrebbe devastato una riserva naturale.

L’accusa ha utilizzato con successo la nuova legge sui diritti umani del Queensland per argomentare che le emissioni di gas serra della miniera avrebbero danneggiato le tradizioni culturali e la salute dei popoli indigeni.

Uno scontro proverbiale che ha visto intentare una causa contro Waratah coal, società che fa capo al miliardario australiano Clive Palmer che, nel 2019, aveva ricevuto l’autorizzazione dal governo per scavare la miniera per estrarre 40 milioni di tonnellate di carbone all’anno, per 35 anni. Devastando la riserva naturale di Bimblebox e riversando nell’atmosfera 1,58 miliardi di tonnellate di CO2.

Con l’assistenza dello studio legale Environmental defenders office (Edo), Murrawah Maroochy Johnson si è rivolta a un tribunale del Queensland per opporsi alla richiesta di estrazione mineraria. La Corte ha acconsentito a raccogliere le testimonianze dirette dalle persone indigene che abitano quei territori che erano state sensibilizzate sui pericoli che avrebbero corso.

Alla fine il tribunale ha dato loro ragione e stabilito un precedente di portata storica: i tribunali devono ora ascoltare le testimonianze dirette delle popolazioni indigene.

Murrawah Maroochy Johnson, 29 anni, è una esponente Wirdi della nazione Birri Gubba. Cresciuta in una famiglia di resistenti, tutti i componenti della sua famiglia fino al bisnonno, sono stati attivi nella lotta per i diritti delle popolazioni indigene.

La sua militanza è incominciata quando, a 19 anni, il Wangan and Jagalingou Traditional Owners Family Council, organizzazione governativa indigena, l’ha invitata a portare la voce e il contributo delle giovani generazioni, insieme a suo zio, l’artista e custode culturale, Adrian Burragubba, nella campagna contro la miniera di carbone di Adani Carmichael.

Successivamente è diventata co-direttrice della ONG Youth Verdict, che sensibilizza le giovani generazioni sul cambiamento climatico nella regione.

La sua lotta contro la miniera di Waratah è solo una delle tante battaglie che ha affrontato per proteggere la sua terra e la sua cultura e le ha permesso di vincere il Goldman Environmental Prize 2024 prestigioso premio, considerato il Nobel Verde, riservato a chi combatte per l’ambiente contro gli interessi economici e politici.

Il cambiamento climatico è una crisi coloniale.

Per una giustizia ambientale rivendica il ritorno ai principi tradizionali di gestione della terra, che sono in armonia con natura e ambiente. Questo significa che la leadership indigena è essenziale per affrontare il problema e creare un futuro sostenibile.

Nonostante le sfide e le battute d’arresto, come la miniera di Carmichael che ha continuato a funzionare nonostante la sua opposizione, continua a lottare per la sua gente e la sua terra.

Il suo consiglio agli altri attivisti e attiviste è di andare avanti, di prendere una pausa quando necessario e di mantenere viva la resistenza e l’identità culturale.

0 notes

Text

He Saved One of the Largest Forests in India from Coal Mining–and Was Honored With 2024 Goldman Prize

👏

1 note

·

View note

Text

https://www.newsmax.com/us/rfk-jr-tea-party-confederacy/2024/05/16/id/1164984/

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is running as an independent for president, once called the Tea Party movement "the resurgence of the Confederacy."

Kennedy made the remarks as keynote speaker at the 2014 Goldman Environmental Prize award dinner, according to The Washington Free Beacon.

"Big Government is a threat, but that's not what the Tea Party cares about," Kennedy said. "They just don't want to pay their taxes.

"And they don't want a Black person to be president of the United States."

Kennedy said the Tea Party movement came out of nostalgia for a plantation economy, according to the report.

"Why is it that they — they all came out of those, you know, those dozen southern states that were part of the Confederacy?" Kennedy said. "This is the resurgence of the Confederacy."

1 note

·

View note