#Featuring short Rathbone :)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Comedy Playhouse: Elementary, My Dear Watson

I'm not sure how this blog post is going to turn out and think it might be rather different to my usual style because the TV programme I'm writing about is radically different from most of the TV shows I have ever watched.

Don't be taken in by the fact this play was broadcast in 1973 under the Comedy Playhouse title. This show is of course a national institution, initially being started in 1961 largely as a vehicle for Galton and Simpson before ending 128 episodes later in 1975. It's unusual for a show of the time because you can see many of its episodes: there are some on the internet but they're also found scattered across the boxed sets of the shows it spawned as independent productions: Steptoe and Son, Meet the Wife, Till Death us do Part, All Gas aqnd Gaiters, Up Pompeii, Not in Front of the Children, The Liver Birds, Are You Being Served and Last of the Summer Wine. This show has spun off an incredible amount of television for one series.

Clearly we're in legendary TV territory already but what elevates Elementary, My Dear Watson above the already great stable it came from was that it was written by NF Simpson. He was a playwright who identified with the Theatre of the Absurd, which built on Albert Camus's idea that human existence is essentially abusrd, and devoid of purpose (britannica.com). The way this came out in their theatre was that they tended to get rid of plot, they abandoned the traditional structures of theatre. You will readily see that once again I am punching well above my weight, writing about this show. There isn't much of Simpson's work available to be seen because he was writing right in the middle of key TV junking time, although apparently he wrote the scripts for two episodes of The Dick Emery Show, which may or may not available. Possibly the other most available of his work is One Way Pendulum (1964) in which amongst other things, one character builds a reproduction of the Old Bailey in his front room and Jonathan Miller conducts a choir of Speak Your Weight Machines. You can tell that Elementary My Dear Watson is incredibly highbrow because of its being prominently featured by the British Film Institute.

The way Simpson's approach comes out in Elementary My Dear Watson is that you will be hard pressed to follow the plot, if indeed there is one. His style requires around short scenes, and non-sequiturs: if you haven't seen any of his work I think you would probably like this if you like Monty Python. It's a show which requires careful attention, because you easily miss some small twist and find yourself wondering what is going on. There are two main plots going on at once. There is a further theme where Jack the Ripper keeps ringing up Scotland Yard to confess but they've never heard of him. Fu Man Chu wants the main exhibit, a dead solicitor. In the middle another dead solicitor appears as the object in a spoof object of Call My Bluff. There is a further theme involving a piano tuner in drag, which is stated to be used because otherwise the show wouldn't fill the time. To cut a long story short: the ingredients of a Sherlock Holmes adventure and other Victorian adventures are mixed up a bit, moved to 1973, and given a coat of surrealism.

As you can tell, I love this show, could watch it over and over and think it's absolutely marvellous. There is another aspect which is wonderful, though, and that was casting John Cleese as Sherlock Holmes. Basil Rathbone and Benedict Crumblysnatch can just give up now because I have to say that Cleese is the Holmes we have been waiting for. Imagine the energy of Basil Fawlty applied to Sherlock Holmes, perfectly foiled by Willy Rushton as Watson, and you have the idea. There's another opportunity to watch Cleese as Holmes (or rather a descendant) in the similarly absurd The Strange Case of the End of Civilisation as We Know It (1979), which I think is also best understood as a series of sketches.

I'm not going to beat about the bush, reading the commentary online it is apparent that a small amount of Simpson's work goes a long way for a lot of people. If you want me to criticise this show I would have to say that the main problem as far as I can see is to wonder what this masterpiece of absurd theatre is doing in a comedy slot, because it's way above being a simple comedy.

I think, though, that if you watch it as what it is and don't expect a simple comedy, it had layers of absurdity which are incredibly enjoyable.

This blog is mirrored at

culttvblog.tumblr.com/archive (from September 2023) and culttvblog.substack.com (from January 2023 and where you can subscribe by email)

Archives from 2013 to September 2023 may be found at culttvblog.blogspot.com and there is an index to the tags used on the Tumblr version at https://www.tumblr.com/culttvblog/729194158177370112/this-blog

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

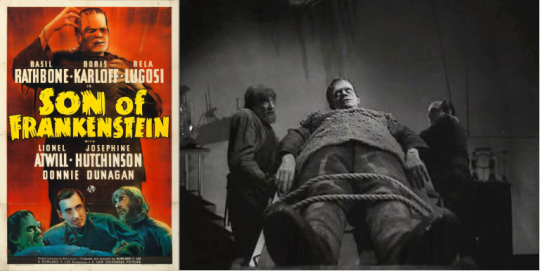

13 Decades of Halloween - 1940s

Superman: The Mechanical Monsters - 1941

A mad scientist creates an army of robots to rob banks for him, but when reporter Lois Lane tracks him to his lair it's up to Superman to save her and shut the inventor's operation down.

youtube

Super heroes have always blended the genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror together.

Once again one might argue that my scope for this marathon is a little too broad, but I would argue back that mad scientists have always been a staple of horror since it's inception. And as we move further into the 20th century we leave the fantasy of the supernatural and the myths of the old world behind and move towards the fear of the new and the undiscovered as technology progresses faster than ever before.

The Mechanical Monsters is the second Superman short to be released by Fleischer studios. The series of 16 shorts by the struggling animation studio were ahead of their time.

Using film noir as inspiration, the shorts feature dynamic camera angles and layouts that were revolutionary for the field of animation. And much like with Basil Rathbone and Sherlock Holmes, the series defined not only Superman for decades to come, but the entire Super Hero genre.

In fact this short features the first time Superman is seen changing in a phone booth, cementing the trope in America's minds for all time.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fifteen Days of Disney Magic - Number 14

Welcome to Fifteen Days of Disney Magic! In honor of the company’s 100th Anniversary, I am counting down my Top 15 Favorite Movies from Walt Disney Animation Studios! Our newest entry is a film that gives us two fabulous characters for the price of one! Number 14 is…The Adventures of Ichabod & Mr. Toad.

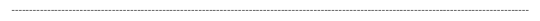

This movie may or may not be a less surprising entry than my previous choice, but it’s nonetheless worthy of placement. Just like “Fun & Fancy Free,” this was one of Disney’s 1940s “package features,” which acted as anthology films featuring two or more cartoon shorts combined into one picture. Most people agree that, of all the package films Disney released during this time, “The Adventures of Ichabod & Mr. Toad” is arguably the best one. As you can probably guess, I agree wholeheartedly. “Fun & Fancy Free” I love primarily because it’s such a nostalgic movie for me; it’s just a film that influenced me a lot and which I still have a massive soft spot for. “Ichabod & Mr. Toad” has that distinction, too, but it’s also a bit different. The movie combines a short version of “Wind in the Willows” with another cartoon based on “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” The framing device is a mysterious library, where two unseen narrators – one voiced by Basil Rathbone, and one voiced by Bing Crosby – declare they want to showcase two of their favorite “fabulous characters” from literature. One chooses Mr. Toad as his subject, while the other chooses Ichabod Crane. It’s pretty basic, but it’s effective: it ties the stories together both thematically and in terms of mood without getting in the way of the focus of each portion. It's honestly kind of bizarre how complete the film feels, because not only are Kenneth Graham’s and Washington Irving’s undisputed masterpieces INCREDIBLY different, on many levels, but the way the shorts treat them is “coincironically” quite different, too. “Sleepy Hollow” is actually REMARKABLY close to its source material. Disney doesn’t soften up the characters, nor even remove all traces of the strange ambiguity that makes this ghostly tale such a great work of art. Indeed, even the language is mostly taken straight from Irving’s pages, and very little from the story is lost. “Wind in the Willows” is the opposite: it actually changes quite a few things from the story, and – being only about a half hour in length – it also has to cut out a lot of the book. The original story was essentially a two-part piece, with the first half of the novel focused on Mole and Rat, and the second half focused on Toad. The short focuses pretty much entirely on Toad’s half of the tale…which, to be fair, is generally considered to be the best part of the book.

What manages to make this film feel more whole, in my opinion, is that for as radically different as the two stories are in a lot of ways, not to mention the ways they are handled separately…not only are both tales presented as representations of literature, which helps in terms of the framing setup, but they also do have sort of an interesting comparison in tone. Both are stories that combine darkness and light: “Wind in the Willows,” on the one hand, features talking animals and zany antics abounding, but it also features characters being thrown in the tower of London, being shot at on steam trains, nearly drowning to death…the list goes on. There’s this dark edge that runs underneath the silly surface. “Sleepy Hollow” is exactly the same: underneath Bing Crosby’s showstopping tunes and the cartoonish shenanigans Ichabod gets up to, there’s an ominous undercurrent, which foreshadows the climactic and frightening final confrontation with the fabled Headless Horseman. This movie introduced me to both these stories, and when I think of either one, I tend to think of the Disney version(s) above all the rest. “Sleepy Hollow,” in particular, has become one of my favorite stories of all time, and I still say the Disney version is one of the best interpretations of the tale, as well as one of my favorites. I’ve already written a play based on that story, and I actually do have thoughts about writing a stage adaptation of Mr. Toad’s story, too, if I can ever figure it out. That, alone, should give you an idea of how influential the movie was on me as a person, and it’s telling that I make a point of watching not just the latter half but the whole picture at least once every year…in fact, I usually watch it around this VERY time of year…

…In fact, after posting this…I think I will watch it today. I do so love this movie. The countdown continues tomorrow with my 13th Favorite Disney Movie! HINT: It Is the Source of Disney’s Anthem.

#disney#disney 100#disney 100 special#list#countdown#top 15 disney animated movies#fifteen days of disney magic#number 14#the adventures of ichabod and mr. toad#wind in the willows#the legend of sleepy hollow

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conan Doyle, Sherlock Holmes and his depictions, detective fiction genre

Conan Doyle is a British writer and a physician. He was born in 1859 and died in 1930, so he grew up in the victorian era. He was born in Scotland, but he was sent to England at a young age to attend Jesuit preparatory school Holder Place in Lancashire and attended Stonyhurst College until 1875. from 1875 to 1876 he attended a school in Austria at the decision of his parents to perfect his German and broad his academics. Doyle moved around a lot when he was young, and also had a lot of careers. He didn’t stay in one place for too long. He had a career in the medical field, and began writing short stories whilst studying practical botany. His earliest work is “The Haunted Grange of Goeesthorpe” which was unsuccessfully submitted to Blackwood’s Magazine. He continued writing fiction and non fiction, writing academic articles in the British Medical Journal.

Doyle’s first work featuring the character Sherlock Holes along with Dr. Watson was “A Study in Scarlet”. This story gained little public interest when it first released in 1887 for the Beeton’s Christmas Annual. The title is derived from a quote from Sherlock, where he describes their investigation in the novel as his “study in scarlet”. this comes from “There’s the scarlet thread of murder running through the colourless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it, and isolate it, and expose every inch of it.” This shows that Sherlock as a character is an analytical character. using these kinds of metaphors shows that he has a genuine interest and motivation for detection. "A Study in Scarlet", scarlet is a colour associated with blood, passion and devotion. Sherlock is described to be excitable during an investigation, and his use of more emotive language written by Doyle shows that he has a passion for his career. "A Study in Scarlet" was also the first detective novel to have a magnifying glass shown as a tool for detective work, and the influence of this today is that stereotypical detective characters always have a magnifying glass on hand.

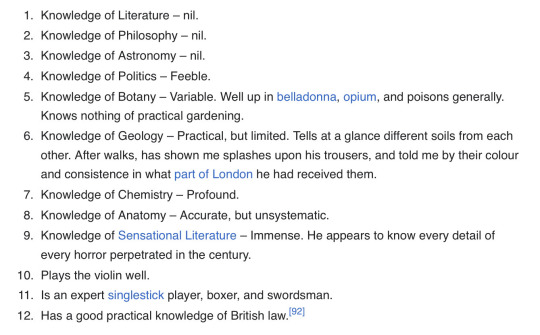

Sherlock Holmes is known for his intelligence in forensics and is very perceptive. he has a great understanding of chemistry, and uses it to his advantage. Forensic science wasn’t as developed as it is today, so he used methods such as analysing handwriting, gunpowder residue, and his general knowledge in chemistry to analyse blood.

Holmes is "disspationate and cold", yet still an eccentric man. he often tried to impress the observers of his investigations by leaving the reveal of his evidence until the end. he had a humour that was sarcastic, ironic and joked incessantly. he seemed to have a very diverse personality, being unemotional, using his head and not his heart, rarely laughed, had narrow habits and was cold. but was also known for having odd habits, such as weird scientific experiments and was considered excitable during investigation. This makes his character quite flexible, and i believe this could have been done on purpose, considering that 56 different short stories were written with Sherlock as the main character, having him being the exactly the same character each time with little depth and interest in hobbies and habits would do very little to attract readers. he had a lot of light moments and had “half humorous and half imp” manners kept his character interesting and unique.

because of this, Sherlock has been interpreted in many different ways along the years.

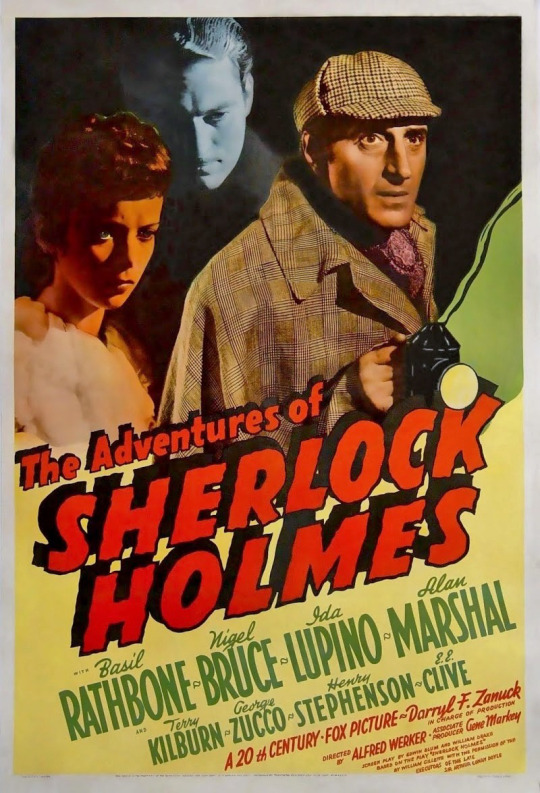

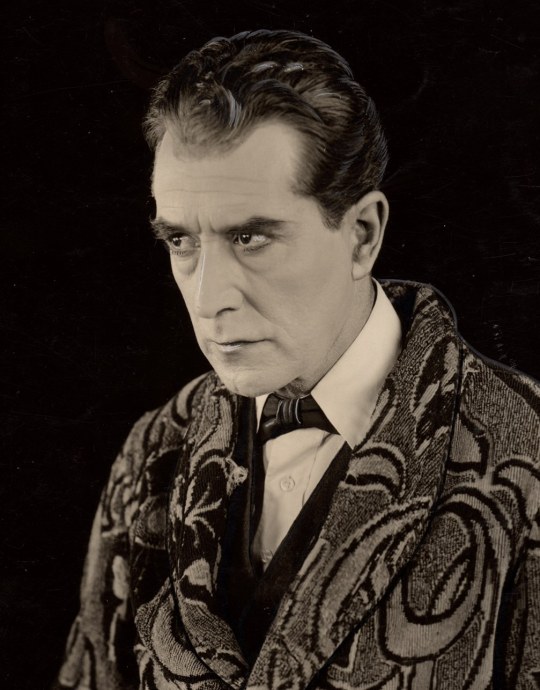

In “Sherlock Holmes” (1939-1946) Basil Rathbone portrays Sherlock accurately to the original portrayals of him. It is one of the only portrayals that stays accurate to the original portrayal and Rathbone’s performance is what gained the adaptation the highest rating, as it serves as a source of nostalgia for fans. Alan Barnes (a writer and editor) says that “Rathbone WAS Sherlock” and many other people such as the writer David Stuart Davies saying “the actor who had come closest to creating the definite Sherlock Holmes on screen”. telling us that this interpretation is as accurate to the original we have seen thus far. Although it is also argued Jeremy Brett is also one of the most definitive portrayals.

Although, there are portrayals that are different to this that stray from the original, such as "Elementary" (2012-2019). In Elementary, Sherlock is played by Johnny Lee Miller as a Sherlock of New York City. In this version, Sherlock is a recovering drug addict. Whilst in Sherlock Holmes Sherlock was using multiple different drugs, such as cocaine, it wasn't described he had any kind of recovery from drugs. This depiction creates a very different mood for the series, and the attitudes of Sherlock because of his recovery are very different to the original personality of Sherlock. The scenery being in the bustling modern NYC an Sherlock recovering from drugs create a dark and serious tone for the series to come and is different from the short stories portrayed by Conan Doyle. Conan Doyle's originals are set in 19h century Victorian England, whilst Elementary is set in 21st century America. These different time periods and locations contrast one another a lot and having the character belong in their time period means that Sherlock in this series can be quite problematic, with relapses, health problems and family murders. Johnny Lee Miller has the most portrayals of Sherlock done by a singular actor for the 7 season Elementary.

There are also depictions of Sherlock in the past and in the present, such as 'Young Sherlock Holmes' where the scenery falls back in time to Sherlock and Watson being teenagers. This creates a more light hearted tone as Nicholas Rowe shows a more charming take on Sherlock's character. This is different from Ian McKellen's "Mr. Holmes"(2015), where he plays Sherlock as a 93 year old with dementia. these two parallels show the flexibility of the Sherlock series and how his character can be interpreted in many different ways from Conan Doyle's writing. These two show Sherlock at the very start and at he very end of his detective career giving us many more interpretations of Sherlock's character.

0 notes

Text

ID: Digitally drawn lineart of Rathbone and Ramsey Singh based on the meme image of a woman staring at a man's big chest. They're both alive. Ramsey is looking off into the distance. Rathbone is standing next to him and side-eyeing his chest. End ID.

#sea of thieves#Shitpost#There I did it#I haven't drawn in forever my hand hurts😂#Ramsey Singh#Sot pirate lord#Sot Rathbone#Rubens art#Featuring short Rathbone :)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherlock Holmes: The Winding Sheet Part 1

Summary: Amelia Bainbridge is urgently seeking the assistance of Mr. Sherlock Holmes, so that she might finally understand what caused her brothers mysterious death six months ago. At first the facts are scant and Mr. Holmes dismisses the case as unworthy of his time. But then Amelia mentions a curious detail and suddenly, the game is afoot…

Characters: Sherlock Holmes (I envisioned Henry’s version but the story could apply to Rathbone right through to Cumberbatch), OC!Amelia Bainbridge, Mrs. Hudson, OC characters.

Warnings: adult/dark themes such as murder, occasional threat of violence/danger, some period misogyny, angsty, mentions of sickness and death, lightly beta’d.

WC: 2190

My work must not be copied, reposted, or translated elsewhere. Likes, follows, reblogs and comments are thoroughly welcome and appreciated! No copyright infringement intended, gifs/pics not my own. I hope you all enjoy and thanks for visiting!

Links to next parts: Part 2, Part 3

Part 1

Amelia Bainbridge hesitated as she stood on the edge of the pavement. Across the street was the infamous black door, its lunette window revealing a soft orange light. Although the street was mostly bare this early in the morning, the market sellers and other tradesmen not yet filling the road, Amelia knew she couldn't simply keep standing there. She slowly made her way across, dodging the piles of uncleared horse manure and potholes, and dashed up the steps. The knocker was stiff in its hanger but she gave a couple of extra knocks, just to be on the safe side. A short, elderly woman with snow white hair answered the door. "Yes? May I help you?" She eyed Amelia carefully, though she didn't seem entirely surprised by her presence.

"Yes... good morning, I have an appointment with Mr. Sherlock Holmes. My name is Miss Bainbridge. I was supposed to meet him later this morning... but, circumstances dictated I come earlier." Amelia swallowed and smiled hopefully. The elderly woman just turned and invited her into the hallway. She motioned for Amelia's wrap and cane, then asked her to wait. She hobbled up the hallway stairs and out of sight. Amelia looked around her. Considering this was meant to be the abode of a world famous detective, the walls were rather old and nondescript, the tobacco stains and faded pictures being the most notable features.

Eventually, she heard a voice from the top of the staircase. "Mr. Holmes will see you now..." the old woman didn't descend the stairs nor stoop to make sure she was properly seen and heard. But she followed her voice up onto the first floor landing and into a largeish morning room. "A Miss Bainbridge for you sir..." the old woman then stepped to the side, nodded her head, and departed. He was seated in a wingback armchair by the biggest window in the room. Smoke curled out from his pipe as he held up a large newspaper. He eventually glanced over to her and nodded for her to take a seat in front of him. Amelia crossed the room slowly, taking in the large, intimidating form in front of her. Even seated, he was obviously well over six feet. His long brown curls framed an angular jaw and piercing dark eyes. He would most certainly be described as handsome, even if his reputation for having a brusque and ungentlemanly manner preceded him.

"Good morning Miss Bainbridge, please, won't you be seated." He glanced at her quickly before placing his newspaper and pipe to one side. Amelia perched on the edge of the smaller chair opposite him, curling back the veil of her hat but refusing to take off either it or her gloves. Instead, she kept her trembling hands in her lap and avoided all urges to fidget with the seams of her gloves as was her custom. "I see you have arrived earlier than expected, do I take it then, that you visit me on a most urgent matter?" She could barely look into his probing eyes. She certainly felt attracted to him, though at that moment she would say she felt more frightened than anything else.

"That's correct Mr. Holmes... I... in truth, I hardly know where to begin." He smiled tightly and clasped his hands on the edge of his knee.

"One can only start at the beginning, and I would say that as you have hurried here so quickly your gloves are inside out and your hat and waistcoat improperly fastened, you have more than enough time to tell me your story. When you are ready, Miss Bainbridge." Amelia was waiting to be summarily exposed, she'd heard the accounts of his other clients and though she hardly felt put at ease, she supposed the sooner she told her tale the better.

"Well... it all started some six months back. My older brother, Jack, had returned from Europe and was about to start work at an accounting firm. Perhaps I should go back a little further..." her voice trailed off and she didn't dare look back up at him. "My brother and I were born and raised on a small estate on the edges of Hertfordshire. Our father died young and our mother remarried some years later to an importer named Edwin Thomas. He's a cold, calculating man. Though he made sure my poor mother signed over the deeds to the estate, she also stipulated that once my brother married, it was to be returned to him. Then, just months after he became engaged, he was struck down by a mysterious illness and died in the night. The autopsy was inconclusive but found no evidence of foul play. However, I don't believe for a minute that my stepfather wasn't somehow involved..." Amelia took a deep breath, it was the most she'd ever spoken in recent years. Mr. Thomas wasn't a fan of female frivolity.

"And why do you suppose this? Were you present at the time of his death?" Amelia tried to swallow back tears, she had to stay calm and focused. And she hardly believed Mr. Holmes would be any more tolerant of female weakness than her stepfather.

"My stepfather allowed me to see him one last time before his body was collected later the same morning. As far as I could see, his bedroom was undisturbed. The windows were all locked shut, his clothes were hung over the chair by his desk as normal..." Amelia had to stop for a few moments to collect herself. "He always slept with the door locked, it was only when our maid couldn't wake him the next morning that they used the spare key. It was an otherwise normal scene..." She stopped for a moment, wondering perhaps if there had been any other details she’d missed. If there were, they'd been extremely subtle. Mr. Holmes simply sat with his lips pursed, a look of deep concentration on his face. Finally, he spoke.

"And you're sure your stepfather would not have had another key? Such copies are easily made." Amelia couldn't answer this specific question, though she was certain no one else had been in his room overnight.

"I'm afraid I wouldn't know what keys are in my stepfather's possession, but my brother's room is directly across from my own. I'm a light sleeper and would have heard someone creeping across the landing. I don't believe anyone visited him in the night." She could have sworn something flashed across Mr. Holme's eyes.

"Then what do you supposed happened Miss. Bainbridge... young men rarely just die. I assume he was in normal health? What about the possibility of a gas leak? Such an event kills quickly and quietly..." Amelia shook her head vigorously.

"All the pipes leading to and from the room were checked... besides, I imagine I too would have been affected being so close..." Mr. Holmes nodded in approval, glad to see she had at least some reasoning ability.

"What were his habits in the evening, did he drink heavily? Read a lot perhaps?" Amelia thought for a moment.

"No, my brother despised drink... he also never smoked or even played cards. He did read at his desk, though not for too long, he had a deathly fear of falling asleep and the candles catching fire..." an idea then entered his mind but he put it aside for one moment.

"Then why assume his death had anything to do with your stepfather? Did he show any particular animosity towards your brother?" Amelia began fiddling with her gloves now, she didn't understand why she was being cross examined if she'd done nothing wrong.

"I know he didn't want the estate to return to my brother... why else would he have stuck around after my Mother's death?" She hoped this would satisfy him but instead, the questioning continued.

"Perhaps he felt a familial responsibility... tell me, did he receive any money upon your mother's death?" Amelia was happy to be able to answer this question definitively.

"He was given a small stipend, on the condition that he continued to look after the state in my brother's absence. The rest goes towards our allowances... my allowance, I mean." Mr. Holmes screwed up his eyes.

"Well then there you have it Miss Bainbridge... he was hardly in a position to leave the estate if he had been instructed to manage it." He sniffed and picked up his newspaper again, their meeting seemingly over.

"Oh Mr. Holmes, you don't understand, my brother returned early, so my stepfather did not need to stay. He also tried to dissuade him from marriage... we even found an article in the local paper several weeks later that besmirched his fiance's good name. Who else could have arranged for such a thing? I know the evidence is scant Mr. Holmes, but you haven't met the man... I'm sure you would feel differently if you did." He sighed and folded up his newspaper for good, clearly, he wasn't going to be permitted the chance to read it.

"Miss Bainbridge... a feeling is simply not enough to determine the merits of a case. From the facts you have presented to me... it seems your brother likely died of natural causes, as unfortunate as that outcome may be." But Amelia wasn't prepared to back down.

"Please listen, Mr. Holmes, my stepfather has requested I now sleep in the same room. I was away with friends for several weeks, I refuse to spend much time in that house anymore. But upon my return, I was told the entire left hand side of the top floor had flooded due to a leak in the roof. He's locked my bedroom and all other rooms on that side so I can't even check for myself. I requested to sleep downstairs but there's been a spate of burglaries in the area recently and my stepfather has forbidden it. I won't even be able to defend myself in such a room, the windows are permanently locked, a fault that my stepfather has also neglected to fix though they didn't have such a fault when we were younger. I believe he purposefully tampered with the windows as well." She looked at him seriously and for once, his expression seemed concerned.

"And you're sure you have no other means of ventilating the room?" Amelia shook her head and hoped he would now agree to take on her case.

"Well Miss Bainbridge, I admit your circumstances are unusual and if your stepfather's intent is indeed murderous, it matters not whether his first attempt is unsuccessful, especially if you say there was no evidence of his room being entered in the night. Perhaps a visit might behoove us... am I free to attend later today?" Amelia grinned from ear to ear.

"Yes... he's away on business until this evening, we'll be undisturbed, of that I'm sure." Mr. Holmes nodded and rose quickly to his feet.

"Very well... head back now and I shall follow shortly, I still have some business in town I must attend to first. Good morning Miss Bainbridge." He nodded politely and waved towards the door. It was an abrupt end to one of the more strange meetings of her life, but Amelia felt great anticipation at finally being able to put the matter to rest. She hurried out of the house and into a waiting cab, ostensibly on her way back to the train station. Mr. Holmes observed her casually from the window. She couldn't have been more than five and twenty but she had an easy if slightly nervous manner. She was also delightful on the eye. He refilled his pipe and returned to his chair. The truth was he had little business that morning. Mrs. Hudson took care of most of his affairs and with Dr. Watson away on sabbatical, he had more time on his hands than usual. Though the facts were scant, he had to admit the brother's death was strange if no obvious cause had been found at the autopsy and there was also no evidence of foul play. The most alarming point in his mind was the locked windows... why would these need to be permanently sealed? If the brother needed to escape, he would have been unlikely to jump or climb down the facade from the first floor anyway. At that moment Mrs. Hudson disturbed his train of thought.

"Some tea for you sir... I see you already have the morning paper but I've also bought you the financial times and a letter from Dr. Watson." She placed everything down on a small console beside him and stood to straighten her dress. She was getting on in years and couldn't keep climbing the stairs so often. "Would you like your breakfast now or later?" Mr. Holmes got to his feet, ignoring both the tea and paper, and shoved Dr. Watson's letter quickly into his jacket pocket.

"No breakfast for me Mrs. Hudson... I have an errand to run." He pecked her on the cheek briefly before striding out of the room and down the stairs.

A/N: Hi guys, as a huge Sherlock Holmes fan of both the original stories and the many series/films, it’s my pleasure to present this new short series. Any feedback is appreciated and Part 2 will be out next Wednesday at 6pm EST - so I hope you’ll continue to stick around and enjoy more to come!

To be updated on when I post please follow @resowrites and turn on post notifications.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Christmas Carol Holiday Season: "Tales from Dickens: A Christmas Carol" (1959 TV series episode)

Yes, this is yet another 1950s TV Christmas Carol featuring Basil Rathbone, and with Fredric March reappearing too! Unlike the 1954 and '56 versions, however, this 25-minute adaptation isn't a musical. It aired as part of a short-lived British anthology series, Fredric March presents Tales from Dickens. Apparently, most episodes of this series adapted excerpts from Dickens novels, chiefly David Copperfield and The Pickwick Papers: this Christmas Carol was one of the series' few adaptations of a complete story. All the episodes, including this one, were hosted and narrated by Fredric March in the library of Dickens's house.

As an adaptation, this short Carol is straightforward and faithful to the book. While it naturally needs to be condensed, the condensing is done more by abridging and streamlining scenes than by cutting any important episodes or characters. Bob Cratchit (Toke Townley) and his family do their traditional business; nephew Fred (Brian McDermott) does his. The Ghost of Christmas Past (Walter Hudd) is portrayed as a bearded old man in a long robe, while Jacob Marley (Wilfred Fletcher), the Ghost of Christmas Present (Alexander Gauge), and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come (Michael McCarthy) are all their traditional selves. The production's most inventive aspect is the way it portrays the scenes shown to Scrooge by the ghosts; while the "real world" scenes at the beginning and the end are performed on realistic sets, the visions of the past, present, and future take place in abstract, minimalist sets, with free-standing windows, doors, and furniture to suggest houses (or trees to suggest outdoor settings). All these scenes are shrouded in white mist, enhancing the ethereal atmosphere.

Basil Rathbone gives basically the same performance as Scrooge that he did in The Stingiest Man in Town in 1956, just with much longer hair and (fortunately) without singing. Ever-so-slightly larger than life, but still convincing and engaging both as a crotchety miser and in his redemption. The supporting cast is solid and compliments him well, and March's narration moves the story along nicely.

I wouldn't call this an essential Christmas Carol by any means. But for fans both of the story and of the famous actors involved, it's still very much worth seeing.

@ariel-seagull-wings. @reds-revenge, @faintingheroine, @thealmightyemprex, @thatscarletflycatcher

#a christmas carol holiday season#tales from dickens: a christmas carol#1959#television#live action#basil rathbone#fredric march

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Top 10 chubby actors in the 1940s

I’ve compiled a list of fat actors from the 1940’s, rated by the number of times and tier (lead or supporting player) their names appeared on the posters promoting their movies and number of credits.

I have excluded some actors which might be considered “Hollywood” fat or they got fat after the 1940s. Some of the actors I excluded are Thomas Mitchell, Orson Welles, Akim Tamiroff, Broderick Crawford, Alan Hale Sr., Cecil Kellaway.

The first list is of actors who got top billing or co-starred in many of their films.

1. Short excitable chubby comedian Lou Costello. Bud Abbott and Lou Costello became the number one comedy duo in the 1940s, replacing Laurel and Hardy from the 1930s. There were 24 Abbott and Costello feature films in the 1940s.

2. Raspy-voiced homespun comedian Andy Devine was popular with audiences in the 1930s. And the studio always found roles for him. In the late 30s and early 40s he co-starred with Richard Arlen in action/adventure B-movies. He started his career, big and athletic, often playing college football players. By the late 30s, he put on a lot of weight. After Arlen departed the studio, he was teamed with Leo Carrillo in the same movie genre. By the late 40s he was teamed with Roy Rogers as Roy’s sidekick Cookie Bullfincher.

3. Charles Coburn was a respected Broadway actor when he started his film career at the age of 60 in the late 30s. He was in demand, gaining 15 starring or co-starring roles of 32 featured roles. He won an Oscar for The More the Merrier in 1943. He was also nominated for Oscars for The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) and The Green Years (1946).

4. Charles Laughton was a well-respected actor and considered one of the best of his generation. Charles was often the lead actor in his films. Among his best films in the 40s were Captain Kidd, The Canterville Ghost, The Big Clock and This Land Is Mine.

5. Nigel Bruce, best known as the often befuddled Dr. Watson in the Sherlock Holmes films of the 40s. Nigel co-starred with Basil Rathbone in 14 Sherlock Holmes mysteries in the 40s after the first two in 1939. He was also featured in Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941).

6. Edward Arnold was a fine actor, often playing imposing figures, businessmen, politicians and corporate villains. He started his career in the teens, in the silents, but quit to do real acting in the theater. He came back to film heavier and accomplished. He had more lead roles in the 30s, but gave up dieting and gained weight in the 40s and played more character roles.

7. Jack Oakie often co-starred in light-hearted romcoms of the time. While in the 30s, he could play either the love interest or the smart aleck best friend, in the 40s he was either the smart aleck friend or anther role as he gained weight in the 40s. His most memorable role in the 40s was as Napolini in Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator.

8. Sydney Greenstreet was an accomplished stage actor when he started his film career at the age of 61 in his most memorable debut as the sinister Kasper Gutman in The Maltese Falcon (1941). Greenstreet’s on-screen rapport with Bogart and Peter Lorre led to more matchups in Casablanca, Passage to Marseilles, Across the Pacific, Conflict, The Verdict, Three Strangers, Background to Danger, The Mask of Dimitrios. Greenstreet was also featured in Christmas in Connecticut and The Woman in White.

9. Jerry ‘Curly’ Howard was the fat member of The Three Stooges comedy team and co-starred in 55 short films in the 40s with his brother Moe Howard and Larry Fine. Columbia was the only film producer still making Short Comedy Films thoughout the 40s.

10. Guy Kibbee. On the strength of six B movies, playing Scattergood Baines does Guy Kibbee make the list. Finishing with 10 starring or co-starring roles and 18 more featured roles in the 40s. He totaled 38 films altogether in the 1940s.

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE GARDEN OF ALLAH is a 1904 romance drama literary work written by British novelist, Robert Smythe Hichens, who set the story's action in the North African desert. It was adapted into three American-made films, two silent flickers and later, an excellent sound film starring Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, C. Aubrey Smith, John Carradine, Alan Marshall, Joseph Schildkraut, and Lucile Watson. The screenplay was written by William P. Lipscomb and Lynn Riggs; indeed, their script was based on Hichens' novel. This Technicolor movie was produced by the famed Hollywood producer, David O. Selznick, in the mid-1930's.

The Garden of Allah is a 1936 American adventure drama romance film directed by Richard Boleslawski, produced by David O. Selznick, and starring Marlene Dietrich and Charles Boyer. The screenplay was written by William P. Lipscomb and Lynn Riggs, who based it on the 1904 novel of the same title by Robert Smythe Hichens.

Robert Hichens's novel had been filmed twice before, as silent films made in 1916 and 1927. The supporting cast of the sound version features Basil Rathbone, C. Aubrey Smith, Joseph Schildkraut, John Carradine, Alan Marshal, and Lucile Watson. The music score is by Max Steiner.

In short order format introductory synopsis, Boleslawski's film tells the story of a trappist monk, Boris Androvski (Charles Boyer), who feels enormous pressure at having to keep his vows as a monk, so he flees his monastery. Yet he is the only one who knows the secret recipe of "Lagarnine", the monastery's famous liqueur, a recipe passed down from one generation of monks to another.

Meanwhile, the beautiful heiress, Domini Enfilden (Marlene Dietrich), is newly freed from her own prison of caring for her just-deceased father and also seeks the exotic open spaces of the North African desert to nurture her soul. @George David Maynard

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad at 34

A review by Adam D. Jaspering

The 1940s were a troubled time for Disney Studios, financially. Through deal-making, patience, and budgeting, Disney Studios endured a dark age and righted themselves. By 1949, they were free to return to the path established at the decade’s beginning.

Abandoned interpretations of Cinderella, Peter Pan, and Alice in Wonderland started up again. Production began on Disney’s first completely live-action film, Treasure Island. True-Life Adventures, a series of documentary shorts, were a surprise hit. The 1950s were going to be very kind to Walt Disney and his company. But they weren't there yet. There was one final task before Disney could shut the door on the 1940s.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad was to be the final package film from Disney, closing out this era. The movie is comprised of two shorts: The Wind In the Willows, and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The two shorts have no thematic link besides being literary adaptations. For much of its development, it had the working title Two Fabulous Characters.

The Wind In the Willows is an adaptation of the 1908 children’s book by Kenneth Grahame. The story centers around a quartet of animals living in Edwardian England. The sensible MacBadger, Ratty, and Moley try their best to help their outlandish and boisterous friend, Mr. Toad. Basil Rathbone narrates the short.

At various points of its production, Disney Studios intended to adapt the book into a full-length movie. The troubles at Disney Studios and a string of creative blocks impeded its completion. At the insistence of Walt Disney himself, it was finally scaled back to a half hour short.

The Wind In the Willows has a level of appreciation in its native Britain, but in the United States, it’s a somewhat obscure novel. Much of its substance relies on a knowledge of British customs and sensibilities. This cultural disconnect makes it relatively inaccessible to American children. For a book featuring talking animals, a runaway locomotive, and a prison break, there is a large focus on manners and dignity.

Being an American production company, Disney Studios had an uphill battle. They not only had to produce the ostensibly British work, they needed to deconstruct it. They couldn't just deliver the story, they needed to present it in a way that could be understood by children internationally. A comedy of manners doesn't work if one doesn't understand the setting and society. Disney does not deliver in this regard. Everything comes across as British for British sake.

The character MacBadger is voiced by animator Campbell Grant. Grant had been working with Disney since the Hyperion Studio days. He was born in Berkley, California, and never lived in Scotland. His talents as a voice actor reflect the fact. He provides an incredibly forced and painful Scottish brogue.

On the other hand, Ratty has such a perfect English accent, it’s almost a parody. Ratty is voiced by Claud Allister, an actual British actor. Allister seems determined to perform the most stereotypical British character ever witnessed by an American audience. Ratty has a stuffy London accent, smokes a pipe, wears a deerstalker cap and wool suit, has a bushy mustache, aristocratic mannerisms, and regularly hosts tea. Is English his nationality, or his personality?

The other characters (minus the Scottish MacBadger) are English as well, but allowed other traits. Is Ratty a joke? Is he meant as an object of ridicule? Is this Disney's attempt at societal farce? His characterization is confusing and doesn't help the story.

The main character, touted as ‘fabulous’ by the film’s working title, is Mr. Toad. Mr. Toad is an individual of great wealth. Old family money, to be specific. He has no work ethic, no discipline, and is intent on spending his fortune and his days as recklessly as possible. MacBadger, Ratty, and Moley spend their days cleaning up Mr. Toad’s messes and curtailing future mistakes.

The relationship between these four is something of a mystery. Ratty and Moley appear to be roommates. MacBadger operates as accountant of Mr. Toad’s estate, apparently a long-time employee. But how all four came to meet is never fully explained or implied. For the purposes of the film, they are burdened with Mr. Toad and his antics. This is their lot in life.

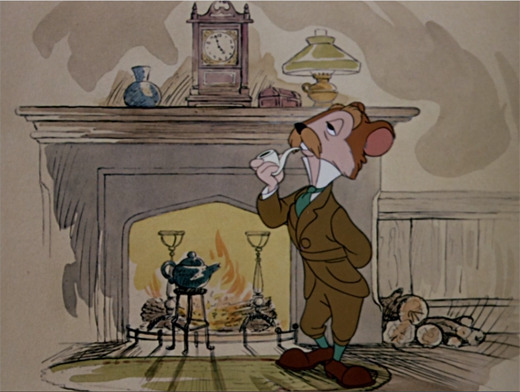

Mr. Toad is a vivacious individual who’s quick to jump on frivolous trends, indulging his whims at a moment’s notice. He spends way too much money on ostentatious displays of conspicuous consumption. We’re introduced to him, rampaging down the road on a horse-drawn carriage. Ratty and Moley beg and plead for him to stop, as he is causing an alarming amount of property damage. Mr. Toad scoffs at their request.

But Mr. Toad's interest in his wagon is halted by another method. Seeing an automobile, his appreciation for wagons disappears. He becomes maniacally obsessing over owning a car. Ratty and Moley intervene again, locking Mr. Toad in his bedroom as though he were an addict detoxing. Mr. Toad's fits are a nice piece of visual humor, but don't endear the viewer to his selfish behavior.

Mr. Toad escapes out his window, finding a tavern full of literal weasels ready to sell him the stolen car. The weasels are stock criminals. Their purpose is to distract the viewer. To trick them into not suspecting the true villain of the feature. The deceit is ineffective, not from a narrative standpoint, but an animation standpoint.

The bartender is one of the most on-the-nose designed characters in the history of animation. His treachery is supposed to be a surprising plot twist, as though we could not see it coming from miles away. The man practically has "villain" tattooed on his forehead. With his squinty eyes, malicious grin, hunched posture and arched eyebrows, the animators did not give their audience any credit. Anyone who could not come to the independent conclusion that he is a con man deserves to be ripped off.

Mr. Toad's friends are forced to intervene again, testifying on his behalf. To no avail. Mr. Toad is arrested, but escapes from prison in an effort to prove his wrongful conviction. MacBadger, Ratty and Moley are tasked one final time to reverse Mr. Toad's fortune and prove his innocence. It is a very one-sided friendship.

Mr. Toad eventually clears his name. He doesn’t learn any lesson, immediately returning to his old imprudent lifestyle. Mr. Toad experiences no consequences, and suffers no losses. His friends don’t think any less of him. They receive no reward for their faithfulness. Our heroes end up exactly where they had started.

The Wind In the Willows is an adventure where somehow nothing happens. There’s no moral, no journey, no change, no growth. It’s a chapter from the characters’ lives. It feels immaterial.

Perhaps Disney Studios expected to reuse the characters in the future. Only a portion of Grahame's book is represented in the cartoon. The Wind In the Willows could conceivably be a franchise. Story elements cut from the original feature-length script could be repurposed into one or two additional shorts.

If this was the plan, of course the writers needed to hit the reset button. Viewers wouldn't understand a follow-up cartoon if they hadn't seen the predecessor. The shorts would need to operate independently as well as part of a series. The characters end here unaffected, consequence free, but primed for another outing later.

If this was the plan, nothing came to fruition. As Disney presents it, The Wind In the Willows is an abandoned pilot. It's the pointless story of an unlikable amphibian and his overburdened friends. A good story makes you glad you went on the journey. The Wind in the Willows is the equivalent of walking into a room and forgetting why.

The production of The Wind In the Willows continued off and on beginning in 1938. Walt Disney himself was rather indifferent to the source material. He only optioned the film rights for financial opportunity. Ironic, as the production was a complicated, eight-year boondoggle.

At various times, it was intended to be paired with Mickey and the Beanstalk or Pecos Bill, and released as early as 1946. For varying reasons, it wasn’t released until 1949, when it was paired with another short entirely.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow had a much simpler production history. There was no logical way to adapt the 24-page short story to a full-length feature. From the beginning, it was intended to be a short. Production began in 1946. In 1947, Disney decided it would accompany The Wind In the Willows to the big screen.

Why pair these two unrelated shorts together? There’s no official justification, but one can deduce their intention. Disney Studios was sick and tired of package films. They wanted to move on. They didn't want to spend a single extra minute supporting them. They had two shorts completed, ready for distribution. It didn't matter how disconnected they were in subject. Sometimes art is a labor of love. Sometimes you want to end the creative process as fast as possible.

Referred to as Ichabod Crane by the film, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is based on the 1820 short story by Washington Irving. The story centers around a superstitious schoolteacher, Ichabod Crane. New in town, he vies for the romantic attention of a wealthy heiress, Katrina van Tassel. Crane is impeded by local townsman Brom Bones, also courting Katrina. As the contest grows to a head, a mix of animosity and local legend decides the fate of Crane.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is one of the earliest pieces of American literature to be regarded as a classic. It remains a staple of the gothic horror genre. The featured monster, The Headless Horseman, remains a chilling figure in the horror pantheon. What's more, the Disney version is considered the definitive adaptation and a Halloween staple.

With such an established holiday association, it’s easy to forget that all mentions of Halloween don’t occur until halfway through. More than that, the iconic ride of the Headless Horseman lasts seven minutes. The first half of the story is nothing more than a typical love-triangle. Just set during the Washington administration.

It’s a testament to great storytelling and memorable characters. Half the picture is establishment and foreshadowing, but never feels plodding or pointless. It all builds, shapes the world, and pays off spectacularly at the end.

The physical appearance of Ichabod Crane is a master stroke of design. Crane is tall, rail thin, with long legs, and a large nose. He looks every bit like the bird he shares a name with. He looks odd, comical even, but not out of place among the other citizens of Sleepy Hollow.

It’s part of his charm that such a gangly, awkward fellow is depicted as a classy, desirable man. Him being voiced by Bing Crosby is a large element of this attraction. It’s not stunt-casting. The disconnect between a major celebrity’s charisma coming from the mouth of a laughably ungainly character is fantastic. It’s just one great element of an intricate character.

Every time we think we understand who Crane is, we learn something new to smash those conceptions. He’s a man of letters, but also superstitious. He’s a romantic, but also deviously wants to marry Katrina for her money. He’s a disciplinarian, but easily swayed by his own interests. A running gag demonstrates he values food over everything. Crane is an enigma.

In contrast, Brom Bones is an archetype. There’s not much to comment on. He’s a burly man, popular with the townsfolk, prone to violence when challenged. He's singularly focused on a specific woman who barely gives him attention. We’ve seen this archetype already with Lumpjaw in Fun and Fancy Free, and we’ll see it again in Beauty and the Beast.

And yet, Brom Bones surprises us by transcending his himbo personality. He displays a precisely-executed bit of cunning. Brom takes advantage of Crane’s superstitions, reciting the story of the Headless Horseman at a Halloween party. With perfect delivery and cadence. He captivates the townsfolk with his tale, but leaves Crane paralyzed by fear.

The final climax features a sense of ambiguity outshining Irving's original story. It’s strongly implied that the Headless Horseman is truly a myth. That Crane experiences no supernatural entities. Instead, it's Brom Bones in disguise who terrorizes Crane on his way home. It's the second half of his scheme, causing Crane to flee town, leaving Brom alone to marry Katrina.

It's strongly implied, but not definite. One may also choose to believe the Headless Horseman is real. That Crane did indeed meet his doom on Halloween night. It’s open for interpretation, and both are viable. Even if one is slightly more credible than the other.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is a fantastic short. Ichabod Crane is interesting and complex. The environments are lush and evocative of a New England autumn. The story is fun and engaging. Its final act is atmospheric and chilling. It's the perfect introduction for children to the horror genre, and holds up to adult sensibilities. It deserves to be watched once a year. But just like with Disney’s other package films, a great short is better enjoyed separated from a crudely assembled movie. And The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is as crude as they come.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad was the last in a long march of frugal package films. Mandated by financial constraints, everyone knew they were low-effort affairs. Thankfully, Disney Studios could pursue ambitious productions once again. Disney would not produce another package film until 1977, when the studio encountered similar financial problems. But in 1949, the era was finally behind them. The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad wasn��t meticulous, wasn’t neat, and wasn’t even coherent as a feature. But it was a film. Disney shut the door on the era with a resounding slam.

Fantasia Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Pinocchio Bambi The Three Caballeros Dumbo Melody Time Saludos Amigos The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Fun and Fancy Free Make Mine Music

#The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad#The Wind in the Willows#The Legend of Sleepy Hollow#Disney#walt disney#Walt Disney Animation Studios#disney studios#Film Criticism#film analysis#movie review#Disney Canon

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Movie Odyssey Retrospective

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949)

Walt Disney seemed to have been mentally drifting in the 1940s, producing a scattershot of films without the artistic discipline he displayed prior to Bambi (1942). His attention wavered between the package animated features, his forays into live-action features and nature documentaries, and taking mental notes about the new medium of television. As Walt approached his 50s, the strain of the work he had thrust upon his studio and himself was beginning to show. In his nurse, Hazel George, he found a rare confidant (it was a friendship, nothing more). He noted his personal need to move forward on projects, rather than tolerate any stalling. “I’m going to move on to something else because I’m wasting my time if I mess around with that any longer,” he told George about his projects stuck in development hell. That was the difficult reality facing The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad – directed by Jack Kinney, Clyde Geronimi, and James Algar – as it became the final animated feature of the package era of Disney animation.

Walt was dividing his time between this film, building a personal miniature railroad in his backyard (the genesis of the idea that would become Disneyland), a nostalgic and personal dramedy of rural turn-of-the-century America in So Dear to My Heart (1948), the start of his True-Life Adventures series of nature documentaries with Seal Island (1948), and restarting the studio’s line of non-package animated features. Of all these things, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad probably consumed the least of his attention. A feature-length adaptation of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows had been in the works at the studio in the months before the United States’ entry into World War II, but was halted due various factors: the war, the Disney animators’ strike, and Walt’s belief that Grahame’s book did not justify a feature-length treatment. Work on an adaptation of Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow began in 1946. But unlike The Wind in the Willows (which also resumed production in 1946), the adaptation of Irving’s story was always envisioned as a segment to a package film – not a standalone feature. Itching to return to animated features and still not convinced in the potential of a feature film surrounding Mr. Toad and friends, Walt announced the merging of the two projects in 1947.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad uses a live-action library as a framing device. The Wind in the Willows makes up the film’s first half; The Legend of Sleepy Hollow closes it out. Each half has a narrator that, at the time, was at their career’s peak. The opening half is narrated by Basil Rathbone (1938’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and as Sherlock Holmes in fourteen movies from 1939-1946); the concluding half by Bing Crosby (best known for his musical career, but was also an enormous box office draw with the Road to… series among other films). Both Rathbone and Crosby hold up Mr. Toad and Ichabod Crane, respectively, as exemplary characters of their home nation’s literature.

The Wind in the Willows begins in 1908 as J. Thaddeus Toad, Esq. harbors an insatiable appetite for adventure, rather than being shut in his elegant Toad Hall estate all day. His friends Rat, Mole, and Angus MacBadger (also his accountant) mostly tolerate Toad’s newest crazes. When, for the first time, Toad spots a motor car, his eyes widen and he is enamored with this newfangled contraption. Toad’s obsession turns into recklessness – leading him to some fraudulent dealings with weasels and legal trouble.

On the surface on Walt Disney’s concerns with The Wind in the Willows, I disagree that Grahame’s novel could never be a feature film.* As presented, the segment runs a neat and all-too-brief half-hour. In an era of communal moviegoing and when a single movie ticket often bought the purchaser a double feature (a B-picture followed by an A-picture, with film trailers, short films, serials, or newsreels in between), The Wind in the Willows is presented as the film’s B-segment. That should not be taken as a swipe on the segment’s quality, however. The Wind in the Willows is a marvel of narrative compactness and situational madness that tees up Alice in Wonderland (1951). Whenever necessary, the narration and newspaper headline montages accelerate the plot. The pace is breakneck, but that never threatens to make The Wind in the Willows incomprehensible. It is filled with dry English wit, benefitting from wonderful voice acting from Eric Blore (a regular supporting actor in Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers musicals for RKO) as Toad and J. Pat O’Malley (Tweedledum and Tweedledee in Alice in Wonderland, 1954’s Dial M for Murder) as Toad’s horse, Cyril Proudbottom. When both Toad and Cyril are introduced in the short song “Merrily on Our Way (to Nowhere in Particular)” – music by Frank Churchill and Charles Wolcott, lyrics by Larry Morey and Ray Gilbert – it is a perfect overture to the madcap misadventure that is about to occur.

Animator Frank Thomas’ (the dwarfs from 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Captain Hook for 1953’s Peter Pan) character designs for Toad, Rat, and Mole are simple, fluid, without too much definition (think Winnie the Pooh). As such, all three are highly expressive figures easily adaptable to the comic scenarios that stumble onto. So much is related to the audience with a crazed grin from Toad, an exasperated sigh from Rat, and Mole’s concerned face. Similar praise must also be dedicated for a side character – namely, the Crown Prosecutor designed by Ollie Johnston (the three animated principal characters in 1946’s Song of the South, the fairy godmothers of 1959’s Sleeping Beauty). The Crown Prosecutor does not appear in the film for long, but his elastic limbs and body – outside Johnston’s wheelhouse – provide a simultaneously comic and menacing contrast to the anthropomorphized animals he towers over. Like all of Disney’s package film segments before it, The Wind in the Willows has numerous instances where the backgrounds and character animations compare unfavorably to the studio’s Golden Age works. But does the lack of painterly backgrounds or character design definition mean much when the piece in question is aiming purely for laughs? Not really. This is some of the best comic filmmaking made by the Disney studios in its history, even though it seems to have been overshadowed by what happens next.

youtube

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow takes place in Colonial-era Sleepy Hollow, New York. Ichabod Crane, the town’s new schoolteacher, is a thin dandy (“lean and lanky, skin and bone / with clothes a scarecrow would hate to own”) possessing an enormous appetite. The man looks nothing like a ladies’ man, but he is exactly that – to the annoyance of town rogue and proto-Gaston, Brom Bones. Brom and Ichabod vie for the attention of Katrina van Tassel, the daughter of wealthy farmer Baltus van Tassel. Noting Ichabod’s superstitious ways, one night Brom tells the story of the Headless Horseman – a stratagem that succeeds in spooking the schoolteacher.

Mary Blair’s midcentury modernist design and coloration for Sleepy Hollow reflects the folksiness of the village, Ichabod’s occasional naïveté. Her curved lines for the surrounding countryside – notice how her trees curve in improbable ways – make it an inviting, down-home place to live. Putting the segment’s climax aside, the backgrounds lend an atmosphere similar to early autumn, as the calendar year begins to wither away.

This, of course, is turned on its head when Ichabod encounters the Headless Horseman. Blair’s backgrounds are blanketed in black, blue, and purple – emphasizing Ichabod’s physical isolation in these moments. The trees blend into an abstract tapestry, as if one cannot see only a few feet outside of the road. Outside of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’s uninteresting romantic wooing scenes, the segment is an exemplar of atmosphere and how to successfully change a film’s tone with animation. Wolfgang Reitherman’s (an animator who later became a prominent director with the Walt Disney Studios in the 1960s) smooth character animation specific to the Headless Horseman chase contrasts Ichabod’s flexibility with the sharpness of the Headless Horseman and his horse. Reitherman’s approach to the characters, combined with Blair’s style for the backgrounds, heightens Ichabod’s full-bodied terror against the Horseman’s frightening presence.

The segment’s pedestrian character animation is unfortunate and is the film’s most visible example of cost-cutting. Yet Ichabod and Brom’s designs – by Ollie Johnston and Milt Kahl (Prince Philip in 1959’s Sleeping Beauty, Tigger in the Winnie the Pooh short films) respectively – are excellent. Ichabod’s outwardly-angled, high-footed gait proclaims immediately his peculiarity in behavior and temperament. His impossibly thin body is bendable to achieve tremendous comic effect while still resembling something like a human. When providing three village women singing lessons, Ichabod (voiced, like Brom, by Bing Crosby), assumes many of Bing Crosby’s affectations while singing himself – those raised eyebrows, that jowl movement. This scene is much funnier if one is familiar with Bing Crosby’s film (and to a lesser extent, television) appearances. For Brom, his muscular frame is a first for a Disney animated feature, providing a somewhat threatening feel for the song, “The Headless Horseman” (which introduces the idea of the segment’s villain). On paper, Brom should be the segment’s antagonist, but things are not clear cut – especially because Ichabod himself has questionable motives in his pursuit for Katrina. Decades later, Kahl’s character design for Brom heavily influenced Andreas Deja’s design for Gaston in Beauty and the Beast (1991). Deja would take some of Brom’s features, add more details and exaggerations, and provide his antagonist a more sneering disposition for Gaston.

The Legend of Sleepy Hollow also has the benefit of songs sung by Bing Crosby and composed by Don Raye (known for various Andrews Sisters songs) and Gene de Paul (1954’s Seven Brides for Seven Brothers). The first, “Ichabod”, is the one number I always find stuck in my head and singing to myself throughout a given day (I also notice, while singing, I’m trying to imitate Crosby’s suave delivery, to little avail). It also serves as an ideal introduction to the character – outlining his personality in less than two minutes. Midway through the segment is “Katrina”, which is as musically uninteresting as the character herself. “The Headless Horseman”, also an earworm, plays on Ichabod’s fears and is a wonderful transition into this film’s most famous sequence.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is the best animated feature from the Disney package era. Its two halves – so distinct in style and narrative approach – are incongruent, some may say an unnatural pairing. But moviegoing audiences in 1949 so used to the B- and A-picture format of film exhibition were also accustomed to feature film pairings with little rhyme or reason. A flighty musical comedy might lead into a war movie; a romantic melodrama before a fast-paced swashbuckler; a seedy film noir giving way to a grand historical epic. Many decades removed from the moviegoing attitudes of this era, the pairing of The Wind in the Willows with The Legend of Sleepy Hollow pays off due to the stylistic distinctions between these two segments. Compared to its package era predecessors, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad has taken the time to shape its characters. For Toad, his motor car mania is a mostly innocent obsession that has endured; Ichabod Crane is forever associated with a harrowing chase through a gnarled wood. Their characterizations come through despite the limitations put upon the studio’s animation staff.

A modest success for Walt Disney, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is now mostly described as a transitional film. The film sees the Disney animators flex their artistry before the resumption of the studio’s traditionally-structure animated features. Sometime during the final stages of this film’s development, Walt and his brother Roy E. Disney fought over the former’s desire to return to features, to recapture the thrill that he felt when he produced Snow White. Under protest, Roy relented and approved a budget for Cinderella (1950) – the first film of Walt Disney Productions’ “Silver Age” films. While Ichabod and Mr. Toad wound down, more resources were being pooled into Cinderella.

This was the effective end to a creatively restrictive period in the studio’s history, but also to some of the most unique offerings in the Disney filmography. Audiences have seldom seen the concise characterizations, Warner Bros.-influenced outlandish humor, romanticized American folk storytelling and propaganda, and experimental animation in a Disney animated feature to the present day. Each of these aspects could be found throughout Disney’s package films – which, for any serious fan of animated film, cannot be dismissed offhand. In a decade of war and global reconstruction, the studio stood mostly alone in the realm of feature animation. But not for much longer. In Europe, animation studio Soyuzmultfilm was beginning to distribute its films beyond the Soviet Union’s borders. And with Walt Disney’s attention straying from his animated films, his animation studio’s record of sterling creativity – already hobbled by the animators’ strike and wartime budget cuts – would be further challenged.

My rating: 7.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

This is the eighteenth Movie Odyssey Retrospective. Movie Odyssey Retrospectives are reviews on films I had seen in their entirety before this blog’s creation or films I failed to give a full-length write-up to following the blog’s creation. Previous Retrospectives include Dracula (1931), Godzilla (1954, Japan), and Oliver! (1968).

* A “feature film” – as defined by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), the American Film Institute (AFI), and the British Film Institute (BFI) – is a film lasting forty minutes or longer.

#The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad#Jack Kinney#Clyde Geronimi#James Algar#Walt Disney#The Wind in the Willows#The Legend of Sleepy Hollow#Basil Rathbone#Bing Crosby#Oliver Wallace#Mary Blair#Frank Thomas#Ollie Johnston#Wolfgang Reitherman#Milt Kahl#Disney#My Movie Odyssey

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ele-May-ntary - Number 27

Welcome to Ele-May-ntary! All throughout the month of May, I’m counting down my Top 31 Favorite Portrayals of Sherlock Holmes, from movies, television, radio, and even video games! Last time, we discussed John Barrymore, who played Sherlock Holmes in the 1922 silent feature of the same name. This time, we’ll be talking about another silent era Holmes, and one who much more accurately captures the aura of the World’s Greatest Detective. Number 27 is…Eille Norwood.

Many people agree that Eille Norwood – an actor I should immediately point out I know nothing about, beyond his take on Holmes – was the first truly iconic Holmes onscreen. He was to the silent era what actors like Basil Rathbone, Jeremy Brett, Peter Cushing, and Benedict Cumberbatch would become for later generations. Between 1921 and 1923, Norwood starred as Holmes in a series of forty-five short films, as well as two feature length productions, all created by the now-defunct studio Stoll Pictures. Yes, you did, in fact, read that correctly: FORTY-FIVE short films, and two feature films, meaning Norwood played Holmes onscreen FORTY-SEVEN TIMES. At least in terms of cinema, specifically, this makes Norwood the single most recurring, long-running Holmes of all time. HOWEVER, very sadly, only FIVE of these early screen treatments have survived to the modern day; the remaining forty-two are all considered lost films. I must confess that, of these five, I’ve only seen four, myself: the three surviving shorts (“The Man With the Twisted Lip,” “The Devil’s Foot,” and “The Dying Detective”), and one of the two feature-length pieces, “The Sign of Four.” (The one I haven’t seen is the other feature-length piece, “The Hound of the Baskervilles,” perhaps ironically, given my love of that story.) Norwood was a trifle older than the literary character, or even most takes on Holmes that would come in the following years. It’s also worth noting that, primarily due to budgetary reasons, the Stoll series was set in then-modern times, with Holmes getting about in motorcars rather than hansom cabs, and wearing a modern suit when he wasn’t in his elegant, luxurious robe while around Baker Street. Despite this, in terms of the actual characterization of Holmes, Norwood was the first actor to truly try and bring the character concocted by Conan Doyle to life. This may be in part due to the fact that Doyle, himself, supervised the making of these pictures, and – by all accounts – Norwood was his favorite Holmes of the silent era. This makes Norwood the first (and possibly only) Holmes to have the official stamp of approval from the author. Much credit must be given to Norwood’s performance, because, especially for the silent era, it really is a marvel. His disguises are excellent; you often don’t realize it’s Holmes in the costumes until after he remove the makeup. It’s also a surprisingly subtle and layered performance, especially for the time, capturing the mysterious, frosty character Doyle describes, while still giving him necessary moments of warmth and humor. Norwood was a meticulous performer, and kept an annotated volume of the Holmes stories on hand for reference on the set at all times. It really is a portrayal that still holds up today…BUT, unfortunately, Norwood’s work is the ONLY thing that honestly still holds up today. He’s great if you want to see an early awesome Holmes, but of the four movies I’ve seen, he’s really the only part I truly adore in any of them. As a result, I don’t think it’s fair to give him higher marks on the list. He’s a great Holmes, but – just for a start – the silent treatment of the character hasn’t really stood the test of time, in my opinion: Holmes works best when you can actually hear him, and don’t have to stall for title cards every thirty seconds. That’s my personal opinion, at least.

The countdown continues tomorrow! Who will be next? Check in and find out!

#ele-may-ntary#top 31 sherlock holmes portrayals#sherlock holmes#eille norwood#silent films#stoll series#number 27

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Philip Purser-Hallard Q&A

Our final Q&A is with Forgotten Lives’ editor Philip Purser-Hallard. His story for the book, ‘House of Images’, features the Robert Banks Stewart Doctor, and opens like this:

‘The usual dreadful creaking and bellowing from the rooms above the dusty office informed me that the Doctor would soon be coming down to check on my progress. I really don’t know what he does up there to make that racket. If you asked me, I’d have to guess that he’s trying to invent a mechanical walrus, and enjoying some success.

‘Honestly, Auntie, I wouldn’t put it past him. My employer is a strange man, with obsessive interests and a deeply peculiar sense of humour.’

FL: Tell us a little about yourself.

PPH: I’m a middle-aged writer, editor and Doctor Who fan; also a husband, father, vegetarian, cat-lover, beer-drinker and board games geek.

A couple of decades ago I wrote stories for some of the earliest Doctor Who charity ‘fanthologies’, Perfect Timing 2 and Walking in Eternity (whose co-editor, Jay Eales, has contributed to Forgotten Lives). These led directly to my published work in multiple Doctor Who spinoff and tie-in series, starting with Faction Paradox.

Since then, among other things, I’ve written a trilogy of urban fantasy political thrillers for Snowbooks, and two Sherlock Holmes novels for Titan Books. I’ve also edited six volumes of fiction for Obverse Books, in the City of the Saved and Iris Wildthyme series. And I founded, coedit, and have written two-and-a-half books for, The Black Archive, Obverse’s series of critical monographs on individual Doctor Who stories. (Mine are on Battlefield, Human Nature / The Family of Blood and Dark Water / Death in Heaven.)

But those two anthologies are where it all started.

FL: How did you conceive this project?

PPH: I’m fascinated by unconventional approaches to Doctor Who, an interest fostered by three decades spent reading the Virgin New Adventures, the BBC Eighth Doctor Adventures and such experimental spinoffs as Faction Paradox and Iris Wildthyme. (Again, I’m glad to have worked with alumni of those series, including Simon Bucher-Jones and Lance Parkin, on Forgotten Lives.) I love the Doctor Who extended universe when it’s at its most radical, questioning, deconstructive and subversive. The Morbius Doctors, standing outside the canon with a foot in the door, are a great vehicle for exploring that.

Once I had the idea for the anthology, the charitable cause followed naturally. These are the lives that the later Doctors have forgotten, and that loss of identity and memory could only put me in mind of the experience of my grandmother, who lived with Alzheimer’s for many years before her death. Gran was a shrewd, intelligent woman, and it was deeply upsetting to see her faculties steadily deserting her. All charities are going through straitened times at the moment, of course, and all of them are in need of extra support, but I felt Alzheimer’s Research UK was particularly worth my time and effort.

FL: Each story in the book features a different incarnation of the Doctor. Tell us about yours.

PPH: As I’ve written him, the Robert Banks Stewart Doctor is a grumpy, ebullient name-dropper with quietly brilliant detective skills and a penchant for deniable meddling. So far, so quintessentially Doctorish, but this incarnation also has an unusual interest in magic and alchemy, a long-term mission on Earth, and an old nemesis demanding his attention.

FL: These Doctors only exist in a couple of photos. How did you approach the characterisation of your incarnation?

PPH: The photo of scriptwriter Robert Banks Stewart that appears onscreen in The Brain of Morbius has a grim look on his face, but there’s another where he seems to be having a lot more fun in the costume. I played with that contrast by making his Doctor a man of excessive, rather theatrical moods, curmudgeonly and charming by turns. With his fur collar, there’s something rather bearlike about him, which made me envisage as quite physically large.

I also love Paul Hanley’s artwork for the character, where he elaborates on the costume to portray this Doctor as a kind of renaissance alchemist – Paul says ‘I like the idea that this is the Doctor who was most interested in “magic”, psychic phenomena, etc.,’ and I certainly leaned into that.

Banks Stewart’s own persona comes through in the Doctor’s Scottish accent and in some of the story choices. Both the Doctor Who scripts he wrote are set in contemporary Britain, so this Doctor’s story is a ‘contemporary’ one – though the timeframe I was envisaging for these forgotten Doctors means that works out as the 1940s. Banks Stewart created the TV detective series Bergerac and Shoestring, and so this Doctor fancies himself as a detective. And he also wrote for The Avengers (and for the Doctor and Sarah rather as if they were appearing in The Avengers), so there’s a flavour of that in the action, the whimsy, and the relationship between the Doctor and his secretary, Miss Weston.

FL: What's your story about?