Text

Encanto at 35

A review by Adam D. Jaspering

Encanto is the story of Mirabel Madrigal. A young Colombian woman, she lives in an enchanted house, in an enchanted village, with her enchanted family. Unfortunately, Mirabel has the misfortune of being the only Madrigal without a magical gift. Unsure of her role or purpose within her family, she lives life one day at a time. One day, signs and omens appear, indicating something is not right with her family and her home. Her fate is apparent for the first time: Mirabel will be the one to save her family, or else, she'll be the one to destroy it.

“Encanto” is a Spanish word that doesn’t translate directly into English. A close approximation is “enchantingly beloved,” acting as a noun. Both enchanting as beautiful and enchanting as magical. In the context of the film, Encanto both describes the village setting, and serves as the village’s name.

It’s surely no coincidence that the word also ends in “Canto.” Alongside the family name “Madrigal,” the theme's primary focus is apparent. A musical affinity is deliberately interwoven into the film.

Lin-Manuel Miranda returns to helm the music and lyrics. This time, he brings more of his signature flair. With Moana’s soundtrack, Miranda was imitating a classical Disney showtune style. The songs were great, but they were formalist creations. He wrote songs for Disney the way he believed Disney songs were supposed to sound.

The music of Encanto is more representative of Miranda’s style. We hear his trademark wordplay, hip hop influences, boisterous appreciation of showtunes, and a blurring of genre lines.

Miranda went above and beyond experimenting with the various Latin music subgenres. The movie’s Colombian setting presents both traditional folk music and modern styles. All of it formed into a theatrical pop construct. To people unfamiliar with Colombia's musical styles, it sounds beautiful, exotic, and inviting. To those who are, it sounds like a cavalcade portrayal of an underrepresented land.

Just like everything else Lin-Manuel Miranda touches, the fan response and commercial success followed. Encanto’s soundtrack was at the top of the Billboard chart for nine weeks. Every song appeared on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, with five songs cracking the Top 50. “Dos Oruguitas” earned Miranda another Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song. The album went platinum in just four months.

But as popular as the soundtrack is, there is a film supporting it that needs to be discussed. Encanto is a movie about a multigenerational family. There are twelve people living under one roof. It’s plot requires a functional understanding of the Madrigal family tree, their history, and the interpersonal relations among them. The movie has an important duty. It needs to make all of its lore known, understood, and remembered before the movie can begin.

In the past, Disney films have had difficulty supporting large casts. It’s difficult to introduce a large number of people, while expecting the audience to remember their names and personalities. It’s also a challenge for the movie to find enough screentime and plot to justify all these characters. Would Mirabel’s large family serve a purpose onscreen? Or would it be like 101 Dalmatians, only important in terms of sheer quantity?

The movie uses two different methods to spit out its exposition. The first, in a prologue, a young Mirabel is told her family history by her grandmother. As a family elder is teaching her family history to an eager young child, we the audience are eavesdropping on the conversation. We learn the origins of the Madrigal family’s gifts, the nature of the magic, and the magic candle at the center of it all. informative and it feels natural. It’s an organic way to present details slowly and purposefully without relying on omniscient narration.

The second method is stranger, but just as effective. In the movie’s opening number, the now adult Mirabel introduces us to her family. In a fast-tempo patter song, not only do we learn the family’s names and relationships, we learn each of their associated magic gifts. “The Family Madrigal” is a silly and unconventional way to learn the character roster, but it’s effective.

Mirabel isn’t breaking the fourth wall by singing directly to us. Throughout the film, a small assortment of kids observe and comment on situations occurring. Much like a Shakespearean chorus, they frame and contextualize important plot points. Ideas that couldn’t otherwise be expressed visually or verbally are directed towards them, even if they’re off camera. They also ask rhetorical questions, keeping the plot threads moving in intended directions. It keeps the story of the Madrigal family from becoming cloistered. It reminds us of the stakes throughout. The movie doesn't concern just a privileged family, but an entire village. Their personal problems have municipal consequences.

For brevity’s sake, we won’t explore every member of the Madrigal family. Suffice to say, each member of the supporting cast has a role and function in the story. Nothing feels extraneous or redundant. Everyone has a unique design and characterization, differentiating them. Everyone contributes in someway, be it to move the plot along, to lighten the mood, or to visually depict changing circumstances. Everyone adds to the film, building on circumstances rather than distracting or overshadowing. Nobody is ever just their one gimmick.

Mirabel’s sisters get two major explorations of the film’s theme. As is tradition in musicals, both Luisa and Isabela reveal their inner secrets and frustrations through song. Long kept hidden from everyone, including themselves, simple words will not suffice.

Luisa’s gift is abnormal superhuman strength. Her song, "Surface Pressure,” is a revelation that her strength has made her incredibly insecure. Due to her gift, she can literally move, lift, or carry anything. Every chore, every duty, every task, she feels obligated to take on the burden. She obediently does so, feeling guilty about ever resting or declining a request. Doing anything less would be a waste of her gift.

Luisa knows full well nobody else can do what she does (or at least not as effortlessly). She also knows these duties must be done for the good of the Encanto. If she doesn't get the work done, she's unfairly placing a burden on others. She's an involuntary workaholic who's placed the world on her own shoulders.

Isabela’s gift is the ability to grow plants and flowers instantly. The beautiful botanical displays implore her to be an epitomized version of femininity. Her song, "What Else Can I Do?,” is a confession that despite her outward perfection, she’s deeply unhappy.

The image Isabela puts forth is one immaculately curated. Her horticultural gift has always been at the forefront of her entire image. She can create a wave of pink flowers instantaneously. So she dresses and behaves like a girl whose persona requires so many pink flowers.

So much so, Isabela has had to suppress any interest or affection that would betray such an image. She has spent so long trying to be a perfect beauty, it’s become effortless and boring. She’s never had the opportunity to pursue any latent interest. Such as a newly discovered thirst for creative expression.

Both of these are in contrast to Mirabel’s character arc. With no magic gift to call her own, Mirabel has always felt like an outsider in her family. She’s felt unimportant and insignificant. She has no immediately obvious and presentable talent in a family of superstars. She’s generic. With no gift, she has no purpose, and therefore no direction. Mirabel can do anything, but can’t do anything with that freedom. Her sisters have great talents, but are stuck doing one thing forever. Neither party is happy, but for opposite reasons.

But despite these suppressed miseries, all three remain loyal and faithful to their family and their Encanto. As unhappy as they are, leaving would be even worse. And they know this as a fact.

Throughout the film, we see the complete Madrigal family tree, but one member is conspicuously absent. Whenever his name is brought up, the topic is swiftly dismissed. We only get a ominous, uniform warning: ‘We don’t talk about Bruno.’

Early on, we have no frame of reference of Bruno’s fate or what he did to earn such a reputation. What heinous act did he perform to be disgrace by his home? What legendary crime has expelled him from his family? What grievous misdeed has made him such a pariah? With all the secrecy and displeasure, one is fully ready to accept Bruno as the film’s villain.

As Mirabel investigates her family’s secrets, all signs point to her long disappeared uncle. She can’t accept his status as an unperson any longer. She needs to know the truth. Again, the truth comes out in song form.

In a film full of hit songs, “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” is the biggest hit of Encanto. For months after the film’s release, the song dominated popular culture. It spent weeks atop the singles chart, and was a viral sensation. It’s difficult to compare mathematically due to the changing states of music consumption, but all indicators imply the same thing: “Circle of Life” was popular. “Let It Go” was big. “We Don’t Talk About Bruno” was a sensation.

The song details the ire, the fear, and the resentment everyone has towards Bruno Madrigal. We hear of Bruno’s many transgressions. We learn both why everyone dislikes him and why they’re glad he’s gone.

But as Mirabel learns, Bruno did nothing wrong. His so-called faults are severely hyperbolized. Everybody’s stories are sour grape justifications for their feelings. Bruno is gone. Rather than miss him or mourn him, everyone convinces themselves they're happy Bruno is gone.

It’s clear something is awry. Even if the rumors and reputation weren’t disingenuous, they don't answer Mirabel's questions. She needs to know why Bruno is gone and why he disappeared when he did. Everyone is making excuses, justifying their feelings towards Bruno’s absence. Whatever Bruno did, Mirabel will never know by asking. Everyone is lying to themselves. They'll of course lie to her.

Bruno’s gift is precognition. He’s an interpretation of the Cassandra myth. In Greek mythology, Cassandra was blessed with the gift of foresight. However, no matter what she saw, she could never convince anyone of the oncoming truth. She was doomed to witness tragic events she could not prevent.

The difference being, when Cassandra spoke the truth, no one would believe her. When Bruno spoke the truth, everyone blamed him. The various prophecies espoused by Bruno are impartial accounts of the future. Whatever happens, happens. Bruno is just the messenger. But he gets the blame all the same.

So what drove Bruno to exile? On the night Mirabel learned she had no magic gift, Bruno tried to discover what had happened. Such an anomaly surely meant something important. His ensuing vision was unlike any he’d seen before: a quantum flux of two possible futures. He saw Mirabel standing in front of the Madrigal home. In one state, the house was healthy, sturdy and strong. In the other, the house was in ruination.

Bruno couldn't blame his niece for the impending fate of his family. Nor could he present such bad news to his family. Rather than disappoint them, scare them, or lie to them, Bruno fled. His family thinks he abandoned them in a time of need. Instead, he's kept a dark secret to himself for years, scared to face the consequences. A self-imposed life of isolation is preferable to traumatizing his loved ones.

Knowing that she's possibly destined to doom the family, the burden is now on Mirabel. How can she avert a tragic fate? How can she prevent the fall of her Encanto? And what's causing the magic to fail in the first place?

The matriarch of the family is Mirabel’s grandmother, Alma. Like Mirabel, Alma has no magical gift herself. Instead, Alma is the one who is responsible for her family’s gifts. Many years ago, it was her who found the candle’s magic. In the 50+ years since, she presides over Encanto, making sure her family’s gifts are being used to the benefit of all. She has no gift herself, but considers herself responsible for the entire community.

In her desire to maintain a pleasant life for all, Alma has mandated perfection from her family. Not harshly, and not maliciously, but mandated all the same. Her words and actions have put forward an attitude of domineering control. As such, the Madrigals have internalized a need for perfection and obedience. Anything else would be sacrilege. But how can one function when the platitude “Respect your elders” determines everything in your life?

Encanto has a unique feeling to it, separating it from other Disney films. Mirabel doesn’t go on a grand adventure to learn something about herself. There’s no villain causing pain and suffering who needs to be toppled. There’s no MacGuffin that will fix every problem once acquired. There’s no quirky animal sidekick. There’s no battle between good and evil or right and wrong. It’s just a family and their long-seated problems which are coming to a head. This family just happens to have magic powers and live in a magic house.

In truth, Encanto feels more like a Pixar film than a Disney film. Pixar’s stories are more introspective and personal. They tend to center on relatable and enthusiastic characters whose comfortable lives are upended. They go on a journey to fix their status. They learn something essential about their lives and their self-worth. They find solace in others, helping solve their problems, too. Problems get solved, not in a way expected, but in a way needed. Disney heroes strive for something good. Pixar heroes find something better in themselves.

Mirabel has been an outsider in her own family. She hasn't realized how unhappy she’s been all these years, subjected to such a life. She hasn’t noticed how stressed and tense and stifled her family has been. She hasn’t realized how domineering and controlling her grandmother has been. It’s always seemed normal to her. She’s only known this as her life. She's never questioned it. But now, faced with her family's destruction, she begins seeing literal cracks in the façade.

Things need to change, but how? Everyone else is comfortable with their lives, convincing themselves they’re comfortable, or afraid of upsetting others. Mirabel's actions seem either inflammatory, disrespectful, or petty. How can she convince her family to talk about their feelings when they have a complex song and dance number about not talking about subjects that upset them?

The crux of the movie is generational trauma. Trauma experienced by a family elder has the ability to affect their children and grandchildren. Sometimes it's physical and abusive. Sometimes it's psychological and manipulative. In the case of the Madrigals, it’s a chronic need for perfection.

The movie never explicitly states when Encanto takes place. There’s a deliberate timeless quality to the picture. It could easily take place in the present, or at any point in the past hundred years. The only piece of technology seen throughout the film is a color film camera.

But there are strong indicators, assuming one is versed in South American history. In a flashback, we see Alma and her departed husband as a young married couple. Their happy life is upended when forced to flee their home. Soldiers move in on the city, violently ransacking the town. These enemy soldiers are only seen illuminated from behind. Those in the know would recognize them as soldiers from Colombia’s Thousand Days War.

Even without the historical context, it’s an easily sympathetic backstory. In a short span, she survived a war, became a refugee with newborn triplets, and saw her husband murdered by nationalists. It was a major traumatic experience. So much so, the mystic forces of the world bestowed Alma with a magic candle. It created a secluded valley where she and other refugees could live in peace, isolated from war and bloodshed.

The candle also awarded her family line with magic gifts to serve this new village. Alma was indeed blessed with great fortune, but has never forgotten it came at a dire price. She never wants anyone to live through a fraction of what she’s experienced. Anarchy cannot destroy any more lives. But there’s no point in saving everyone from misery if the process itself is causing misery. Her obsession with perfection is eating away at her family.

Bruno’s vision wasn’t Mirabel either fixing or destroying the family. It was both. She needed to destroy its dysfunctions to save them. Mirabel never received a gift because it was her destiny to fix this. Had she received magic powers, she’d only be another extension of the trouble. This the type of problem that can only be seen by an outsider.

Coincidentally, Pixar has explored the idea of generational trauma twice. The first in the 2017′s Coco, and again in 2022′s Turning Red. Both films center their conflict around fantasy. Both integrate the fantastic and the dramatic. Both agonize over the troubles and problems that have rippled through generations. And both are resolved in a satisfying way.

Released between these two pictures, Encanto seems like a natural companion piece. But while both Turning Red and Coco intertwine their protagonists’ personal journeys with their exploration of family troubles, Encanto falls short. Pixar’s offerings focus on the invisible conflict between children and elders throughout. Generational conflicts are explored from the start to the conclusion. Much of Encanto is spent recognizing whether there’s even a problem to begin with.

By the time Mirabel recognizes her family's issues stem from her grandmother's actions, the film is rapidly approaching the finale. The idea is dropped into our laps almost unceremoniously. The movie declares its theme like a mystery detective announcing the culprit.

In fairness, the plot thread isn’t pulled from thin air. The subtext was always there, just shoved into the periphery. The movie wanted us to focus on other things instead. Things like Bruno’s absence and Mirabel’s prophecy. The movie was dangling red herrings, trying to keep its fantasy elements in the forefront. It's as though the writers were ashamed of the conclusion. As though family drama and grief processing were too mundane for their fantasy world.

When Mirabel and her grandmother discuss their issues, the resolution arrives questionably fast. It’s emotional themes are localized to one scene, and that scene is handled in a very mature, low key, expedited way. It’s a sensible discussion between a grandmother and her granddaughter. It’s not a bad representation of an introductory therapy session, but it feels insubstantial for a movie. Its more of a forced resolution than an actual satisfying conclusion.

In both Turning Red and Coco, the cycle of generational trauma is broken with storytelling twists. Actions, revelations and discoveries overwhelmingly change their respective families. Everyone learns something they couldn’t have possibly understood before the adventure at the core of their movie. The trauma is broken because their entire worldview is now different.

But in Encanto’s case, the trauma is broken because the writers want it to be broken. Mirabel reaffirms her love for her family. Alma promises to be patient and understanding. And this solves their problems. It’s an easy, unearned path to resolution hiding behind sentimentality.

It’s also a major stylistic mismatch from the fantasy concepts we’ve seen so far. There’s no discovery of a long-held secret. There’s no radical upheaval in the family dynamic. There’s no sacrifice or loss or change in the family’s magic. Mirabel and Alma have a conversation, apologize, and that’s it.

It’s ironic that such a treatment befalls a film about the struggles of who you want to be conflicting with who you’re expected to be. Disney had an idea of what ending they wanted, and forced it to end in such a way.

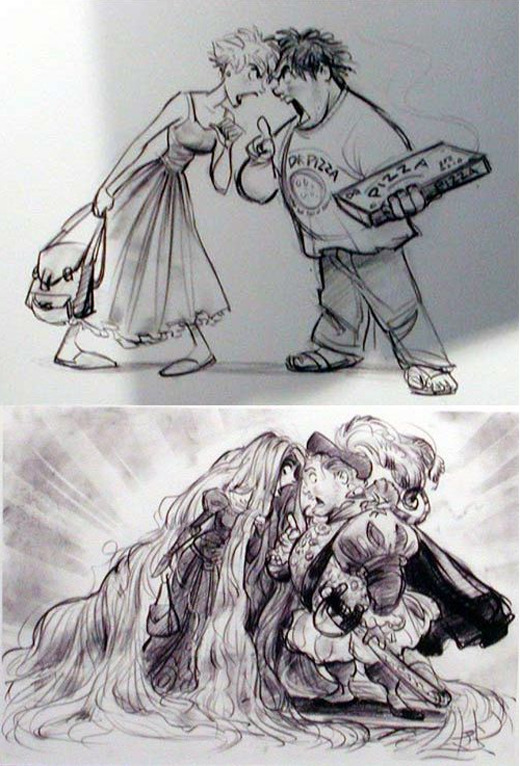

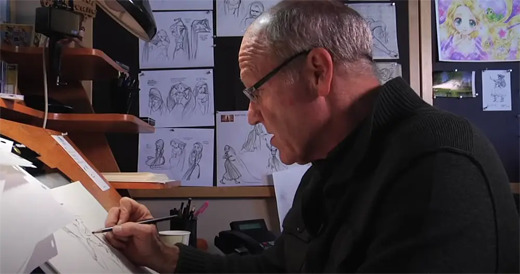

It’s even more ironic that this wasn’t the only time such an occurrence befell the film. It happened during the character design phase. Luisa is an ox of a character. She’s able to lift entire buildings without effort. Being such a strong person, Luisa is naturally drawn bulky with muscular limbs and torso.

One would think this would be a fairly straightforward portrayal of a strong character. But the animators had to emphatically fight the producers to keep this character design. From the producers’ perspective, the overly-muscular woman would be off-putting and intimidating. She’d look unappealing on merchandise, and kids would stray away from any product featuring her.

The opposite wound up happening. Girls in the coveted youth demographic absolutely loved Luisa and her design. She was the breakout star of the film. What little merchandise existed featuring Luisa sold out quick.

Meanwhile, Disney gambled on the stereotypically girly Isabela, whose products only sold average. Funny enough, Isabela’s character arc concerned her frustration towards her conventional femininity. She considered her curated, manicured ways confining and unsatisfying. But it was that artifice that was slapped on bedsheets and bookbags. It’s like the merchandising gurus were hoping kids didn’t pay attention to the film.

It’s not until Isabela abandoned this life that she found happiness. Such a departure is visually represented by fluorescent highlights in her hair and a splotched dress. Like Luisa, this design was also sought after, but not as readily available as other merchandise. Both wound up being available in greater quantities, but not until after the Christmas buying bonanza.

Even the casting process squared expectations against reality. Mirabel is voiced by actress Stephanie Beatriz. Except for a supporting role in the film adaptation of In the Heights, Beatriz didn’t have a history in music or musicals.

Beatriz is most famous for her role as Rosa Diaz, a hardened, intimidating police detective on the sitcom Brooklyn Nine-Nine. This is likely why the filmmakers first approached her for the role of Luisa. They assumed Beatriz was identical to her character in real life. In reality, Beatriz is a substantially upbeat, energetic, feminine person. Detective Diaz is almost an opposite of her actual personality. Aside from the family strife, she was uncannily similar to Mirabel. Beatriz was soon offered the film's lead role instead.

In all, Encanto had a problem defining its very definition. It was made in defiance of corporate expectations. Disney assumed they knew what audiences wanted, and what shortcuts would be acceptable. Those assumptions were not only wrong, but often backwards.

During production, Disney CEO Bob Iger stepped down from his position, replaced by Bob Chapek. This change in leadership combined with a misunderstanding of audience expectations is troubling. These are the necessary circumstances to bring about another dark age in Disney Animation. But since this blog’s exploration into Disney’s past has caught up with Disney’s present, we can’t tell for certain. We’ll have to wait and see.

In conclusion, Encanto is a very energetic and colorful film. It has a vibrant soundtrack, memorable characters, and a good sense of humor. But its trenchant themes are left unintegrated, leaving its message contrived and superficial. While the narrative itself is anemic, the film's strengths carry it ably. It’s a well-built house, but it’s on a lousy foundation that needs repairs.

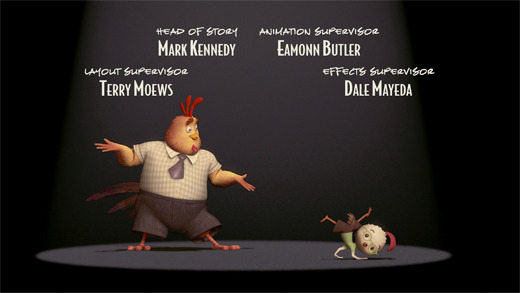

Beauty and the Beast Fantasia The Lion King Frozen Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Cinderella Alice in Wonderland Sleeping Beauty Mulan Zootopia Tangled The Little Mermaid Aladdin Lilo & Stitch The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh Pinocchio The Jungle Book Robin Hood The Sword in the Stone Bambi The Emperor’s New Groove Encanto The Hunchback of Notre Dame Moana The Princess and the Frog The Great Mouse Detective Big Hero 6 101 Dalmatians Bolt The Three Caballeros Lady and the Tramp Frozen II The Rescuers Down Under Atlantis: The Lost Empire Wreck-It Ralph The Fox and the Hound Fantasia 2000 Peter Pan Dumbo Hercules Meet the Robinsons Brother Bear The Black Cauldron Raya and the Last Dragon Melody Time Oliver & Company Treasure Planet Tarzan The Rescuers Pocahontas Saludos Amigos The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Winnie the Pooh The Aristocats Ralph Breaks the Internet Dinosaur Fun and Fancy Free Make Mine Music Home on the Range Chicken Little

#Encanto#Disney#walt disney#Walt Disney Animation Studios#disney studios#Disney Canon#movie review#Film Criticism#film analysis

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Raya and the Last Dragon at 35

A review by Adam D. Jaspering

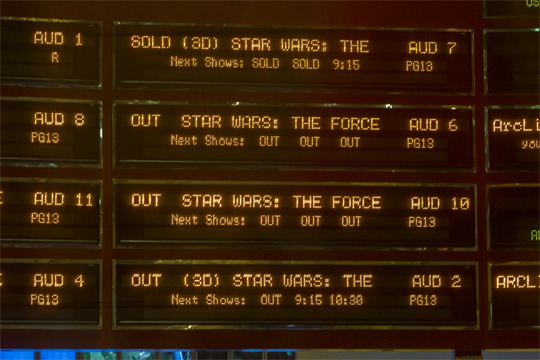

Imagine you owned a four-screen movie theater. Your four screens are in auditoriums of four different sizes: 400 seats, 300 seats, 200 seats, and 100 seats. You can show two different movies on any number of screens. Movie A is a much anticipated blockbuster from a widely respected studio. Movie B is a less auspicious film that has garnered only mild interest. You can safely assume for every 1000 customers wanting to see Movie A, only 50 will want to see Movie B.

On the surface, it would seem logical to put Movie A on all four screens. 1000 tickets sold is better than 950 tickets sold. But as counterintuitive as it seems, this would not be the best decision for a theater owner. Offering Movie B on the smallest screen, even filled to half capacity, will pay off better in the long run.

From a consumer perspective, you have already demonstrated a commitment to Movie A. Those unable to see Movie A due to sold out showings know there will be another opportunity. They can return at another time or another day. But if Movie B is never shown, you lose those potential customers outright. They won't return because they know they will not be served. By only showing Movie A, you serve 1000 customers. By catering to both markets, you combine both totals, serving 1050 over a longer range.

The reason is, it is in a business’s best interest to provide a variety of products or services. Economists routinely find evidence that consumers appreciate options. It allows businesses to reach a wider audience. It increases customer loyalty. It demonstrates growth potential. It improves visibility and credibility in a competitive market. It also provides for crossover demographics. In our hypothetical scenario, there is also an unaccounted for third group who will see both Movie A and Movie B.

This scenario is the basic booking strategy for a movie theater. Their main goal is to accommodate their customers. Variety benefits theaters and patrons. It does not represent the best interest of the movie studio who made Movie A. As Disney continued along their domination of pop culture in the late 2010s, they began exercising their power on the movie theater industry. Disney Animation, alongside Pixar, Star Wars, and Marvel, were consistently earning hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office. It wasn’t uncommon for their films to cross the one billion dollar threshold. Disney knew they had a viable product, a market presence, and a consumer base. But they needed to control the theaters themselves to maximize returns.

Because of an antitrust law from 1948, movie studios are unable to own their own movie theaters. All cinemas in the United States must be unaffiliated from film studios. Meaning, Disney was legally required to split all their grosses with any theater who played their films.

To put it another way, a movie’s potential is not just the responsibility of the studio. They can make the film, and they can market the film, but it's ultimately theaters who decide when and where you can see the film. Booking agents decide what films to book, what markets to focus on, and how long engagements last. Then individual theaters decide when the movies play, how often, and in how many theaters of what size.

In 2016, 30% of American box office sales were for Disney films. They were the cinematic titans, with the closest runner-up accounting for only 11% of sales. With this leverage, Disney forced theaters into more lopsided deals. Theaters favored variety. Disney pressured them to favor homogeny.

We'll use 2017′s The Last Jedi for an example. Under Disney's new contracts, theaters were required to play the film for four weeks on their largest screen. Released over the busy holiday season, every rival studio was automatically relegated to inferior auditoriums. Competing films would be smaller affairs by default, unable to impact Disney's revenue.

Disney also began taking larger percentages of the box office draw. Typically, studios and theaters split the revenue of a new release 60/40. Disney increased their take to 65%. Breeching any part of the contract authorized Disney to increase their take to 70%. Violators would also be blacklisted from future releases. It was Disney's ultimatum: show our movies the way we want them shown, or else you can’t show them at all.

Disney held all the cards. They were responsible for one third of a typical theater's annual income. Losing that income was a serious threat. These were authoritative demands, but theaters had no recourse. They were forced to accept.

How much longer until Disney forced their films onto every screen for months at a time? How much longer until they took 80% profits? 90%? Would they start demanding a percentage of concession sales as well? How long until Disney pressured congress to roll back antitrust laws, allowing Disney to own their own Disney-brand theaters, making them the only place to see Disney content?

Fortunately, these questions remain eternally hypothetical. Things changed in 2020. As powerful as Disney was as a corporation, they still had to buckle to the power of an international viral pandemic.

When the world entered governmentally mandated shutdowns, the film industry came to a screeching halt. For months, the vast majority of movie theaters were closed. Studios lost their primary revenue source.

Initially, studios attempted to wait out the Coronavirus pandemic. It was speculated the virus would run its course and be controlled after two weeks. When the pandemic reached its third month, studios realized they needed a long-term solution.

In the pandemic’s beginning, streaming sites were still operating on a library-based system. They offered a back catalogue of films. They showcased movies after their premieres and theatrical runs. With the exception of Netflix, which operated in defiance of the conventional studio/theatrical system, debuting films on streaming sites was a rare occurrence. It was usually reserved for documentaries, special interest films, or low-budget affairs.

Antitrust laws prevented Disney from owning their own theaters, but a streaming site is not a theater. Disney was well within their rights to debut films on Disney+, superseding movie theaters altogether. Being the only major studio with their own streaming service, they had an advantage available to no one else.

Perhaps this was always the intent. Perhaps Disney was frustrated by the limitations and boundaries of the theater system. Perhaps a move to online premieres was always an intended path for Disney+. If it was, the quarantine moved the timeline forward.

Debuting a film on streaming meant a staggering decrease in profits. The infrastructure was in place, but the market was not primed. Audiences were either hesitant, uninformed, or unmotivated to purchase new releases online. But Disney was currently earning nothing from new releases, and any number was better than zero.

But how should one price a film in this new market? Theaters had an obvious itemization metric. One body, one seat, one ticket. Was it fair to charge a price for a new release on top of already charging for the site’s membership? Or should they forego one fee for the other?

Disney tried various strategies in real time. Artemis Fowl, Soul, and The One and Only Ivan were released for free to Disney+ subscribers. A live-action adaptation of Mulan was also released on Disney+, but with a $30 surcharge.

Bypassing theaters was a major leap forward instead of a gradual rollout. The strategy wasn't expected to be a success, only a slowing of the financial hemorrhage. Mulan earned $261 million from streaming against a $200 million budget. Compare that to the previous year’s adaptations of Aladdin and The Lion King, which respectively earned $356.6 million and $543.6 million domestically.

The verdict was in: some people would willingly pay $30 for a new release on streaming. A good percent of patrons would not. This would not be a viable strategy for the future.

As the pandemic entered 2021 and society began reopening, a large percent of people were still hesitant to return to public spaces. Disney and other studios were impatient. They wanted their money, and theaters were still the best place to get it. But some people weren't going to theaters, just as some people weren’t buying premier streaming access.

Studios made the decision to offer simultaneous releases for the foreseeable future. Those who wanted to pay for convenience could watch at home. Those who wanted to pay for the experience could go to theaters. Either way was fine, just as long as they paid.

In 2021, many films from various studios were offered both in theaters and as premium video on demand. On Disney’s side, such films included Black Widow, Jungle Cruise, and the subject of today’s article, Raya and the Last Dragon.

Their releases delayed by months, Disney needed to recoup money somewhere. Marketing and merchandising for Raya and the Last Dragon were slashed. It's hard to hype up a soft, delayed, inauspicious premiere when you can't even attach a specific date.

The financial breakdown of the simultaneous release strategy is unknown. Here, Disney and other studios ceased the practice of officially reporting studio earnings and box office results in tandem with streaming numbers. As the saying goes, no news is good news. And the movie industry desperately wanted some good news.

Simultaneous releases were always intended to be a temporary measure. Disney and other studios discontinued the practice by the end of 2021. Disney is still reliant on theaters, for now. They can still arbitrate demands, but are no longer using theaters as their only option.

Most mid-budget films are debuting exclusively on Disney+. Large budget films are still playing in theaters first, but Disney has been more flexible with theatrical releases. Standard booking windows were once 90 days before Disney released on home media, streaming, and digital purchase. That range has been shortened to 45 days. In some cases, it’s even shorter. Their following film, Encanto, was in theaters for only 30 days before being offered on Disney+.

The point is, people and corporations are primarily driven by their own self-interests. But self-interests change in times of emergency. A draconian overlord of the box office one day could be struggling the next. One has to adapt and acclimate to a changing environment to survive. It's true whether you’re a movie studio trying to sell films in a pandemic, or a fantasy heroine trying to defeat the forces of darkness.

Raya and the Last Dragon is a fantasy adventure set in Kumandra, a land overrun by distrust and tribalism. The hostility of its five populations has awaken an ancient curse, The Druun. 500 years ago, The Druun was defeated by an army of dragons, of which none remain. Raya, princess and surviving heir to one of Kumandra's thrones, fights for her world's future. Following a legend, she discovers the world’s one remaining dragon. Together, they must stop Kumandra from being destroyed by The Druun, but also stop Kumandra from destroying itself.

Let’s address the elephant in the room straightaway. The Druun is a smoke monster. It travels through the air. Large swaths of the population perish after being exposed to it. The lucky survivors remain vigilant, taking many precautions to avoid exposure. They live disenfranchised, their lives upturned. The world has been thrown into upheaval because of The Druun. This is either the most unfortunate or ironically appropriate film for Disney to release during the Coronavirus.

Raya and the Last Dragon is Disney’s foray into dystopian fiction. We see the world as chaotic and struggling, but still surviving. The five Kumandran tribes begin the film as temperamental and isolationist. They're houses of cards; functional, but ready to collapse. The Druun is the catalyst.

The Druun, as monstrous and destructive as it is, is only one element of the world's negative state. The people are besieged by political turmoil, environmental disasters, and militaristic omnipresence. It's an essential element of dystopian fiction the film gets right: even if the big problem somehow vanishes, the million little problems still exist.

Kumandra is geographically centered on a large inland sea shaped like a dragon. Each of the five nations takes it name from the anatomical portion of the dragon it borders: Fang, Heart, Spine, Talon and Tail. Five lands, five populations, five biomes, and five cultures.

Having five separate lands makes for an interesting challenge. Five designs, five styles, five motifs, five interlocking sprockets of a single complex mechanism. These lands pride themselves on specific attributes and traits. They're all part of one collective whole, but not by choice. They more readily identify themselves by their individual distinctions. These conflicts define the world; a contrast between how each tribe identifies and what how it wishes to differentiate from the others. People from Fang very much wish not to be like people from Heart, for example.

Such a portrayal relies on the filmmakers immaculately constructing all five lands. There must be an emphatic and deliberate representation of these five nations and populations. We must be able to tell instantly, from any still, what land we are in.

Raya and the Last Dragon doesn’t accomplish this. In a film that’s only 100 minutes long, less than 20 minutes can be dedicated to each land. There just isn’t enough time to define a full national aesthetic while also telling a story of characters just passing through.

Early in the film, we’re given a brief montage providing a one-sentence identifier of each land. The issues are present early on, with the five nations being far too similar. The writers abused their thesaurus, finding every synonym for “combatant” to describe them. Maybe a commentary on the futility of their fighting. An indication that despite their insistence on differentiation they’re pretty much the same. Maybe.

When all five nations are represented in a room together, they all look the same and they all act the same. If they weren’t all wearing their specifically-assigned color scheme, there’d be no way of knowing who comes from where. Once the sun goes down and everyone is shrouded in shadows, that’s exactly what happens. Again, maybe a deliberate design choice. Maybe an oversight. It’s hard to say.

When it comes time to visit their lands, the distinctions are clarified marginally. Tail and Spine are completely ravaged by The Druun, leaving next to nothing of their world. What little we knew about them before, we now know even less. Their culture and their populace are left in ruination.

It’s hard to mourn the loss of an empire when we were never introduced to the empire. Tail is presented to us as a giant inhospitable desert, and that’s what it feels like. That anyone ever lived here, much less a thriving empire, we have to accept on rumor.

The same goes with Spine. In certain shots, it looks like a remote village in the woods where maybe a few dozen people lived. But on the scale we’re presented, it could also easily be an abandoned sentry post. Either way, it’s hard to imagine it as an entire empire.

These lands don’t feel like the ruins of newly fallen civilizations. They feel like waypoints for Raya to travel through. They feel like staged ghost towns or amusement park facades. Places bereft of any true identity beyond the first glance. Their only distinguishing features are their climate, used to break up the visual monotony. They don’t register as the lands of Tail and Spine. They’re the desert land and the icy forest land.

Talon gets a fair share of distinctive characterization. It’s floating markets have kept the hydrophobic Druun at bay. A majority of its populace remains alive, relocating to the waterfront. However, the desperate people have descended to a life of crime and con artistry. We see them as innovative, commercialized, treacherous and duplicitous.

Talon is the only one of the five lands that seems like a real world within this film. Our characters interact with the citizenry. We see their day-to-day life. We have adventures and situations and interactions that could happen only here. This is an empire. Everywhere else feels like a movie set.

Heart and Fang are where a majority of the film takes place, including both the prologue and climax. Ironically, so much of the story takes place in these two locations, we learn very little about them. There's too much story happening in the foreground. Characterization and exposition has to be forced out. There's no time to let us absorb the scenery because things are moving too fast and in such abundance. Details concerning setting are treated as unimportant, and therefore undefined.

We can understand base traits of Heart and Fang based on things like architecture and landscaping. For example, Heart features cobblestones and an integration of grass and plants. They’re reverent of the past and the surrounding natural world. Fang meanwhile features polished marble and golden accents. It’s a very structured and controlled environment. While these designs evoke ideas, we learn nothing about the societies or populace beyond each land's two named characters.

Heart is Raya’s homeland. It’s a peaceful land, steeped in its appreciation for ancient history. Except for the polished azure palace, it’s fully integrated with its surrounding jungle environment. So much so, one is quick to associate Heart as the token jungle land. Except every time Raya is traveling outside one of the five lands, she’s traveling through jungle landscapes. Heart doesn’t represent anything because its the default, standard empire. It's the jungle land in a world full of jungle lands. If not for the temples and palace, it would have nothing distinguishing about it.

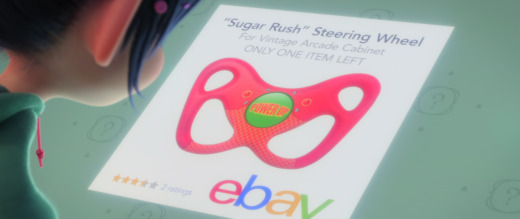

Prior to the Druun apocalypse, Heart was home to an artifact known as the Dragon Gem. An ancient relic full of magic, Heart kept the gem protected and safe for centuries. They were rather adept at protecting it. Which is why they trained a 12 year-old Raya to be a guardian, who on her first day of the job, opened the temple to show the gem off to her friend, who immediately tried to steal it. The land of Heart is one based in ancient customs, but not logic or critical thinking.

Fang is a stock empire in dystopian fiction, that of a false utopia. It’s a very urban environment (or as urban as one can get in this fantasy world). In a world where peril and uncertainty abound everywhere, Fang can guarantee security. This doesn't happen by chance or accident. The powerful and the influential promise safety in exchange for obedience.

There’s a dark irony of Disney portraying a paradise masking a nefarious secret. The Disney Corporation’s entire schtick is portraying itself as a utopia, trying to suppress its heinous exercises of power. The manicured beauty of Disneyland is maintained by underpaid wage slaves. The company’s colorful cartoons and movies hide the authoritative lawyers who enforce copyrights with an iron fist. Coveted merchandise is assembled and packaged in third-world sweatshops. Their library of intellectual property cheats creative minds and laborers out of residuals. Even the previously mentioned totalitarian standards against theater owners is a demonstration of their merciless drive for control and profit. All these crimes are hidden behind childlike smiles and family-friendly whimsy. The ends justify the means. Disney can’t rightfully depict a dystopia onscreen, as they themselves would never see the perpetrators as the bad guys.

Fang is the only one of the five lands that has not descended into anarchy or ruination. This puts them in a unique position of power and privilege. Fang’s leader knows full well that any return to normality is a dismissal of these entitlements. It's her full intention to possess the Dragon Gem which could otherwise undo her fortune.

If she can prolong the apocalypse, maintaining her position of power, she wins. If she can end the apocalypse herself, positioning Fang as the heroic savior of Kumandra, she wins. Either way, things work in her favor. But she needs the Dragon Gem before she decides. And as such, she needs Raya out of the way.

These orders are carried out by, Namaari, the film’s antagonist. Namaari is the daughter of Fang’s leader, just as Raya is the daughter of Heart’s. Both are versed in the history of their land. Both appreciate the legend of ancient dragons. Both are thoroughly trained in combat. There's a symmetry that makes them a memorable pair. They have very much in common, and in another life would have been strong allies. But one decision set these two on separate paths, turning the two into bitter enemies.

As a child, Namaari was instructed to befriend and betray Raya. All personal feelings aside, Namaari carried out her mission. Maybe Namaari was genuine in her affection towards her new friend, but saw an opening and took advantage. Maybe it was subterfuge all along, stringing Raya along until an exploitable opportunity presented itself. We don't know, and frankly, Namaari presents herself as not knowing either. Six years later, Namaari continues sparring with Raya, their rivalry only worsened with time.

The Dragon Gem is a magic artifact that has kept The Druun at bay for centuries. In a struggle to steal it, the gem shatters into five pieces, each fragment claimed by a different land. Once it shattered, The Druun returned.

The Dragon Gem is the last remnant of the dragon army who sacrificed themselves 500 years ago. One dragon remained behind, using the Dragon Gem to defeat the Druun before disappearing. If this dragon can be found, they can use the Dragon Gem to stop the Druun once again. With nowhere else to go and no better plan to try, Raya follows an old legend that the last dragon is dormant somewhere. This is Sisu, the Last Dragon of the film’s title.

It only takes a few moments of screen time to understand Sisu's schtick. She's directly influenced by Genie from Aladdin. The eccentric mannerisms. The manic energy. The upbeat and jovial personality. The insistence on telling jokes while everyone else is waiting patiently for her to be quiet so the movie can continue.

Sisu is a very commanding character, in that any scene she's in, she must be the center of attention. I’m sure there are some people out there who appreciate her and her sense of humor. Maybe in a different film, she’d contribute more than she contributes to Raya and the Last Dragon. As it is, Sisu has a bad habit of distracting the audience and ruining the film’s immersion. She doesn’t feel like she belongs in this world. She doesn’t act like she belongs. She doesn’t talk like she belongs. She feels like she got stuck in a wormhole and popped in from a different universe.

This problem isn’t Sisu’s exclusively. The movie has major tonal consistency problems throughout. It wants to be a serious film, trenched in warfare, with explorations of nobility and honor. It also features bugs that fart and explode. It wants to champion the tenet that in times of tragedy, people should put aside their differences and work together for the good of mankind. Then it features a sassy baby doing parkour. It wants to be an honorable depiction of southeast Asian culture and heritage. Then our hero and villain bond by finding out they are both, and I quote, “Dragon nerds.”

Genie was one of the best parts of Aladdin, and the reason was, despite him being unlike anything else in the film, he still fit into the film. He was a thematically clashing comic relief, but Aladdin was a comical movie. Every character had a humorous disposition or good natured quality to them. Even the stern and sour Jafar had a penchant for dressing up in costumes and verbally mocking the heroes.

When Genie did something that made no sense in the film's world, there was a foundation that supported it. He provided a unique style of comedy in a movie that was already explicitly comedic. Raya and the Last Dragon is not that type of movie. Raya and the Last Dragon feels like it should be an epic period drama crossed with a fantasy adventure. A boisterous comic presence doesn’t benefit it.

Half of the movie, Raya's half, is trying to be a serious, Wuxia-inspired adventure. Sisu’s half is trying to be a low comedy escape. These two halves are in competition throughout the film, and the comedic portions fail every time. Sisu and Raya don’t make a good pairing. Sisu’s jokes seem like an unwelcome intrusion, and make Raya’s brooding seem unnecessarily misanthropic.

All these critiques would still apply even if Sisu were actually funny. In reality, Sisu is a fairly obnoxious presence. Not only does her humor clash with the tone and setting of the world, they’re just not very good jokes. And because Raya is so concerned with her own affairs, the screenplay forces her to accept Sisu as a helpful ally. There's no time for her to argue or pass judgment. Raya can’t break her stride and tell Sisu she’s irritating. She just ignores Sisu until she’s quiet again. A skill I’m sure most of the audience wishes they possessed.

Sisu’s schtick is delivered in abundance. Sisu has the temperament of a seven year-old child crossed with a barking terrier. She’s in love with the sound of her own voice, and she’s desperate for others to hear her speak. The filmmakers definitely took the quantity over quality approach. She's the worst type of comic relief character: a poor comic and no relief.

Raya’s main character arc concerns her trust issues. Betrayed as a child, she’s grown into an extremely self-reliant but paranoid person. To grow, she needs to give people the benefit of the doubt, accept help when needed, and rely on the promises of others. Especially if she’s going to be a leader.

While this sounds like a noble message in a vacuum, it’s deeply flawed in practice. Even the film itself has trouble making the moral work. Time and again, Raya is told to trust people, mostly by Sisu. Throughout, trusting strangers leads to moments of vulnerability. Raya and Sisu are repeatedly subjected to deception, fraud, theft, or treachery, usually after Sisu insists Raya trust a total stranger. A movie can't espouse the importance of trust one minute only to use treachery to disenfranchise our heroes in the interest of drama. It's one or the other.

The knows what point its trying to make, but absolutely fails at demonstrating it. It wants to offer a perfect ideal of harmony, and not a gray, conditional reality. But trust is not something that can be doled out without consideration or caveats. Raya certainly has trust issues, but Sisu’s blind faith and optimism is just as big a problem. And yet, only Raya’s flaw is addressed as something that needs fixing.

The logical route would be to offer an interplay between the two extremes. Together, our two heroes learn the flaws of their respective viewpoints. Together, they find a happy medium between their polarized extremes.

But caution and forbearance doesn't fit into the Disney mold. “Everyone lived happily ever after” is the traditional ending. You can't achieve that by serving the unflappably happy character a reality check. "Everyone lived with a much more realistic understanding of the duality of human nature" doesn't have the same ring.

There’s a lot of story going on, and the movie wants us to understand it alongside the world, mythos, and people. A lot of exposition happens trying to establish it all. Not only do we get a flashback, we get a prologue within the flashback.

The plot isn’t really all that complicated: there’s a dragon, there’s a monster, and there’s a magic rock broke into five pieces. The dragon can use the rock to stop the monster, but she needs all five pieces.

It’s not an impressive story, but it’s serviceable. The focus is instead on the unique world and the unique characters. While there are plenty of unnecessary distractions, vacant areas, and a lot of painful humor, it’s a detailed and unique world. Despite the film's many flaws, it's at least pleasant to look at.

There’s lots of great animation. The Druun cloud effects. The flowing hair of Sisu as she flies and swims. One can practically smell the scent of a riverbed every time a moss-covered stone is shown. The animation detail is plentiful.

The water effects are also good, and I deliberately damn them with faint praise. Canonically, The Druun is repelled by water. As such, the people of Kumandra have adapted to living on or near the giant inland sea as a form of protection. There’s a justified reason in-story for three quarters of this movie to feature water effects. Behind the scenes, it was another opportunity for Disney’s animators to display their proficiency at animating water.

After both Moana and Frozen 2, I have zero doubts that Disney can animate water. Raya and the Last Dragon is the third film that demonstrates their marvelous ability to animate water in CGI. We’ve seen their abilities in great abundance, and we're seeing them again. Either Disney has lost their confidence to try anything new, relying on one skill they know they can do well, or they’re conceited, assuming everyone is pleased with this one specific trick. The water effects are good, but they’re rote and overdone.

What of the characters? There are better heroes in the Disney canon than Raya, and there are better villains than Namaari. But what makes them unique is that they make a great adversarial pair. Normally, Disney films don’t feature the hero actually sparring with the villain until the third act. Until then, they either don’t cross paths, or there’s a tense coexistence until the villain becomes irredeemable.

Raya and Namaari feud throughout the film. There are great choregraphed fights between the two, each skilled in close-quarters combat. It never gets violent or offensive to the young audience, but the thrill is still present. The outlandish stunt choreography keeps the combat rooted in the fantastic. Raya’s sword, which can transform into a whip, is ridiculous but also stunning.

Raya is the film’s main character, and as such, it’s her character arc that serves as the central crux of the story. But it’s not Raya’s growth and development that drives anything. When she was a kid, she trusted someone when she shouldn’t have. Then when she was a teenager, she didn’t trust anyone. Then at the film’s end, she trusts people again. That’s not growth. That’s getting back to normal.

As a kid, Namaari betrayed Raya. She did so based on the beliefs and values forced upon her. She was taught that manipulating others for the sake of her homeland was not a bad thing. Namaari continues to antagonize Raya to present day.

Raya was the one hurt. Raya is the one who’s carrying this baggage. Raya cannot rightfully be expected to be the one to grow and change. It’s Namaari who has to redeem herself and in turn save Raya. The film should instead be focusing on Namaari in terms of character growth and development. This would allow Raya to be static and drive the plot.

Namaari’s redemption arc is a slow burn, realizing she’s become a person she doesn’t want to be. Her patriotism to Fang, her loyalty to her mother, her command of an army... all hollow without her own self-respect. Throughout the film, she realizes how meaningless and destructive all her achievements have been. She's been a pawn in her mother's tyrannical game.

She knows she needs to change. She needs to fix things, many things, but doesn't know how. In the film's climax, The Druun's strength reaches critical mass. It forces her to take the necessary steps to redemption all at once.

The movie gets the roles of Namaari and Raya backwards in the climax. As it plays, Raya is sacrificing herself to save Kumandra. Namaari has to make a giant leap forward and join her, absolving herself and stopping The Druun.

Instead, it should be Namaari sacrificing herself first. Both to atone for her misdeeds against Kumandra, and to apologize for betraying Raya. Raya should be the one forced into a moral dilemma against a ticking clock. She needs to decide whether to stick to her toxic beliefs, or to abandon them and accept Namaari’s apology.

The relationship between Raya and Namaari is an adversarial one. These two are evenly matched in every confrontation. There are very few differences between them, and as such, they understand each other very well. Knowing their enemy is just as easy as knowing themselves. Their fights are tense and personal, whether they be verbal or physical.

Unfortunately, it all feels hollow. What should be a front and center character dynamic is left in the periphery of the film. Not by neglect or ineptitude, but forced out. There are too many superfluous elements crowding the film.

Again, the film’s focus is on the importance of trust. As Raya travels through Kumandra, she encounters strangers whom she needs to rely on to progress. In turn, Raya winds up acquiring a large travel party. With each land she visits, Raya acquires a new tagger-on. The film is called "Raya and the Last Dragon," but such a name is underselling the swollen cast.

At the film’s climax, there’s Raya and the last dragon. There's also Raya’s pet/steed Tuk-Tuk (a combination pillbug, armadillo, dog, bear amalgam), Boun the young restaurateur/boat captain, Noi the infant con artist, Tong the grieving warrior, and three thieving monkeys. Namaari may be the most important secondary character thematically and contextually. But she's forced to fight for screen time with a character eerily similar to The Boss Baby.

Each tagger-on has been negatively affected by The Druun, losing their family, loved ones, homes, and purpose in life. Each of them need both friends and hope, and Raya provides both. Just like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, they join her quest, turning a personal journey into a group endeavor.

The cast represents a message of unity and cooperation. Each comes from a different land of Kumandra, but each have the same wants and goals. Narratively, it makes sense. The problem is, since each has basically the same backstory, the same goal, and the same purpose in the story, they don’t have much to distinguish themselves. There’s too many characters and not enough story. It’s easy to forget Noi and Tong even have names. I keep calling them Baby and Eyepatch.

It's the same problem as Meet the Robinsons. The story requires a large cast, but that's an ambition, not a justification. There are too many characters, and the movie doesn’t provide enough for them to do. After everyone is introduced, they sit around, contributing nothing. They become set decoration.

Raya and the Last Dragon is a movie that has good ideas at its core, but buries them under unhelpful nonsense. The final result is an unrewarding slog drowned under superfluous ideas, bad humor, and a misguided moral. The film tries to build a world beyond its ability and the limits of the running time. Everything seems rushed, underdeveloped, synthetic, or redundant. What’s good is emaciated, and what’s left is irritating.

Maybe we should have watched Movie B.

Beauty and the Beast Fantasia The Lion King Frozen Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Cinderella Alice in Wonderland Sleeping Beauty Mulan Zootopia Tangled The Little Mermaid Aladdin Lilo & Stitch The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh Pinocchio The Jungle Book Robin Hood The Sword in the Stone Bambi The Emperor’s New Groove The Hunchback of Notre Dame Moana The Princess and the Frog The Great Mouse Detective Big Hero 6 101 Dalmatians Bolt The Three Caballeros Lady and the Tramp Frozen II The Rescuers Down Under Atlantis: The Lost Empire Wreck-It Ralph The Fox and the Hound Fantasia 2000 Peter Pan Dumbo Hercules Meet the Robinsons Brother Bear The Black Cauldron Raya and the Last Dragon Melody Time Oliver & Company Treasure Planet Tarzan The Rescuers Pocahontas Saludos Amigos The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad Winnie the Pooh The Aristocats Ralph Breaks the Internet Dinosaur Fun and Fancy Free Make Mine Music Home on the Range Chicken Little

#Raya and the Last Dragon#Disney#walt disney#Walt Disney Animation Studios#disney studios#Disney Canon#Film Criticism#film analysis#movie review

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Frozen II at 35

A review by Adam D. Jaspering

Frozen was meant to be a stand-alone work. Released in an era that prioritized sequels and remakes, Disney Animation valued innovation and new ideas. But Frozen was a special case. Frozen was not just a popular film, it was a phenomenon.

The original Frozen was successful, acclaimed, and popular by every metric. Ironically, it was almost too celebrated to make a sequel. Anything that follows up such a landmark production was sure to be a lesser effort by comparison.

Upon completion of the 2015 theatrical short Frozen Fever, Disney decided it was worth the risk. The characters of Frozen were still beloved. Their world was still engaging. The concepts were still fun. The audience was still eager. Disney wanted to return to the world of Frozen, and a sequel was greenlit.

In a show of eagerness, Disney gave themselves a standard four-year production window. Fans and investors alike were expecting Frozen II in theaters by November 2019. Surely, such optimism would in no way backfire.

Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, writers and directors of the original Frozen, returned to helm Frozen II. The duo branched out, onboarding other official writers. This included storyboard artist and animator Marc Smith. Also joining were Frozen’s soundtrack mavens Robert and Kristen Anderson-Lopez. The award-winning songwriters were no longer consulted just for musical needs. The husband and wife team were contributing story beats as well.

Perhaps five writers were needed to ensure quality. Perhaps it contributed to the increasingly layered and complex plot. Perhaps because the two initial writer/directors were detained with other duties. In 2018, partway through production, Lee was promoted to Chief Creative Officer of Disney Animation.

In the past, I’ve lauded the efforts and contributions of former CCO John Lasseter. I chose my words carefully, knowing full well how his tenure with the company ended. Lasseter, despite his achievements, left Disney on very unfortunate terms.

As CCO, Lasseter’s creative and artistic visions lifted Disney Animation out of a dark age. However, it was his personal behavior that resulted in his departure. Lasseter made frequent salacious remarks and unwanted physical advances towards Disney’s female staff. An ongoing problem, this behavior began when he was at Pixar, and continued well throughout his employment with Disney. He used his power, his authority, and his connections to silence any objection. But after many years and many victims, the secrets erupted. As the allegations went public, Disney removed Lasseter from his role.

Jennifer Lee was promoted to fill the void. This opportunity gave her the dual responsibility of overseeing all of Disney Animation while also continuing to finalize the production of Frozen II. A distracted and overworked director, even one of two co-directors, explains much of the final film.

It was decided early on, Frozen II would be centered on a hook. Elsa would hear a strange, ephemeral voice beckoning her. Four notes, sung across the wind, only she can hear. She’d go on an adventure, trying to find who is calling her and what they want.

Such a foundation should be great a jumping off point for a screenplay. Except nobody on staff knew at the time who this voice would belong to, or what their relation to Elsa would be. Nor did they decide on these factors in a timely manner. Production continued with the idea left ambiguous and undecided, under the assurance the details would be provided down the line. Without a central plot or direction, development of the story proceeded at an awkward, aimless pace.

Everybody had vague ideas about how the movie should look and how it should feel. Nobody knew what the movie should consist of. All they had were odd story bits and scenery. Songs sung about nothing in particular for no known reason. New characters who had no purpose and no reason for existence. And no central story to tie everything together.

In February 2019, the first teaser trailer was released online. It featured Elsa standing on a beach at night, staring down the crashing tides. She attempts to run across the water, daring to breech the ocean waves that crash on top of her. She’s alone, she’s determined, and she’s fighting nature’s might with all her strength.

The trailer garnered interest and buzz. Fans all speculated the same things. Why was Elsa alone? Where was she? Where was she trying to get to? Why was she so desperate to combat nature, not taking a boat, or waiting until the waters calmed?

The filmmakers had no answers because they themselves had the same exact questions. After three years of development, this scene, apart from a few isolated test scenes, was the only completed part of the film. The animators had nothing to animate because the story and storyboards were still changing. The filmmakers didn’t know what Elsa was doing, how she got there, or what it all meant. All they knew was that it looked cool. But they used it for the teaser trailer, so they were obligated to fit it in the film somewhere.

Test screenings of the movie were disasters. Child audiences were either bored or confused. The plot was too convoluted, exposition dumps were unhelpful, and scenes went on too long. The film’s tone was too dark and too dry, lacking the childish humor of its predecessor. Much of the film felt hopelessly bleak.

These test screenings forced rewrites all the way to May, 2019. The plot was simplified, humor was added, and the story moved at a more exciting pace. Frozen II was being rewritten six months before the release date.

There is a docuseries on the making of Frozen II available on Disney+. It was likely intended to be a marketing tool, giving audiences even more Frozen content. It unintentionally depicts the desperate path to completion. Disney higher-ups have edited the series to seem like Frozen II was a labor of love, but the stress bleeds through.

It’s clear everyone involved was deeply invested in the project. The problems weren’t an issue of incompetence, arrogance, or limitations. The film just couldn’t coalesce. At a certain point, the motivation was nothing more than “get it done.”

Frozen II is the end result of a marathon session of rewrites, reworks and re-edits. It’s a miracle a film of any regard came from such a Sisyphean effort. If a release date wasn’t already promised, Frozen II would have very likely languished in development hell for years.

Frozen II takes place three years after the events of the previous film. Life has gone on without significant drama or upheaval. Our heroes are happy. Their kingdom is prosperous. Everything seems fine. All until Elsa begins receiving omens. To find answers, she and her colleagues venture to a mythic land up north. There, they must confront their kingdom’s past, discover their family heritage, learn their destinies, and right a wrong generations in the making.

The first thing one notices about the film, setting it apart from its predecessor, is the color scheme. Frozen was set during an unseasonable winter curse. Its hibernal setting prompted landscapes of icy splendor, including snow-draped landscapes and motifs of white and blue.

The sequel is set in autumn. A variety of arboreal colors interact, focused on reds, violets and deep green. The only scenes featuring snow and ice feature Elsa specifically. The name ‘Frozen’ is doing its setting a disservice.

Once again, color theory is employed to great effect. The first film used its color scheme to reflect Elsa specifically. There was a delicate beauty representing Elsa’s fragile mental state, but also a chilling sense of danger, representing her despair and hostility. The autumnal colors of the sequel represents both Elsa and Anna together. Autumn is a time of transition. Before we know the stakes of the plot, we know the the film will be focusing on impermanence and change.

The first change is one of setting. The first movie took place in Arendelle and its surrounding forests and mountains. The sequel removes our heroes from these familiar areas. They move further north to a land called Northuldra.

Arendelle is a rather undefined place. Its unclear whether its a nation, a nation state, or the capital city within a nation. It’s not important. What is important is, Arendelle is set in a fictionalized version of Norway.

A Norwegian setting was chosen purely for aesthetic reasons in the first film. The sequel uses its real-world counterpart for a fuller narrative effect. Northuldra is an area in the taiga biome, sparsely populated, with only hearty flora and fauna surviving. Its sole human residents are foragers, lacking any permanent structures or colonies. The Northuldran people have a relatively small tribe (about 50 people), but a rich culture.

Northuldra is a stand-in for the Sápmi region and the resident Sámi people. Scandinavians and the Sámi live mostly detached lives to each other. Scandinavians prefer the southern portion of the peninsula for its arable farmland. The Sámi prefer the north, where great populations of reindeer live. This passive cohabitation has preserved the Sámi culture and lifestyle.

The plot of Frozen II uses this cultural relationship as fodder for its own plot. The Arendelle citizens represent Norway, while the Northuldrans represent the Sámi.

Acknowledging Disney’s poor history of depicting indigenous cultures onscreen, the Sámi insisted on a cultural ambassador opportunity. The filmmakers accepted, sending several representatives to Sápmi. They absorbed the culture, made diligent notes, and shared preliminary character models and story bits. This ensured what appeared onscreen was both respectable and accurate.

Also part of the contract, Disney would produce an officially dubbed version of Frozen II in the Sámi language. A genuine gesture of goodwill, and also a clever contract rider. An ignored international demographic now had a movie that would be uniquely theirs.

The Northuldran are depicted as an unknown culture to our heroes. They’re simple, but not primitive. They’re interesting, but not a sideshow. They’re seen as rustic and rural rather than uncivilized or savage.

There are many ways to read the differences between the two groups. Their clothing is one of the most interesting. Anna and Elsa wear dyed fabrics, embroidered with intricate designs. These outfits are clearly handmade and personalized for them. Even Kristoff, laden in fur and leather, is far departed from mere hunting and trapping. Rugged and durable, they’re manufactured all the same.

This contrasts against the Northuldran, all of whom wear a uniform, practical outfit. The prime focus of clothing is not of fashion, but functionality and unity. One type of outfit for one tribe with no extraneous details. If it rips, it can be mended. If it’s ruined, it can be replaced. If more are needed, more can be made.

But this uniformity is not depressing or stifling. In the simplicity, there is beauty. The dulled browns and grays emphasizes a tapestry-like focus to needlework. It’s admirable as a craft, not as couture. What’s more, the monotone appearance emboldens the scenery and the world around them. The people look clean, simple, and humble to emphasize instead the resplendent glory of their forest home. Again, the autumn setting working to the film’s advantage.

One of the most beautiful moments of the film isn’t visual, but musical. Upon Anna and Elsa learning their mother was Northuldran, the entire populace welcome their estranged sisters wholly into their ranks. They do so with a choral performance, strongly implied to be an honorable cultural tradition (Olaf steps on this tradition, but only for a second before the film cuts away).

Although Anna and Elsa are unfamiliar with it, we the audience recognize the song. This is the same choral chant that accompanied the title card of the first Frozen and the studio logos of the second.

But this isn’t a lazy bit of recycling. The filmmakers weren’t considering a canonical use when the number was first performed. They just needed something that sounded Norwegian and somewhat mystical to introduce the Frozen title card. They used a traditional folk song, and that was that.

In the sequel, the piece is given a new context, one inside the film world’s universe. This abstract orchestration has been given a definition and a purpose. It’s an amazing bit of retroactive connectivity that makes the world of Frozen and Frozen II seem like a cohesive, defined unit.

While the score and music are both grandiose accompaniments, nothing quite reaches the heights of its predecessor. The major problem is, Frozen II’s soundtrack is treated as a retread, not a continuation. Many of this film’s big numbers seem to mimic the first film, trying to replicate its success. “Some Things Never Change” is the follow-up to “For the First Time in Forever.” “When I am Older” is the partner of “In Summer.” “Reindeer are Better Than People” gets a reprisal before its spun into a much more bombastic original work.

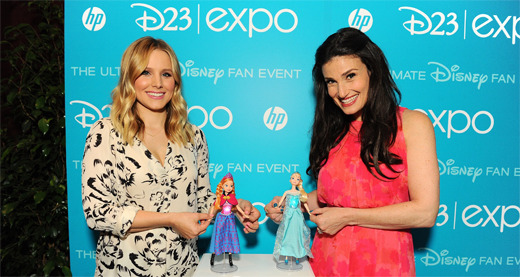

Elsa gets two numbers, both hoping to copy the success of “Let It Go.” “Into the Unknown” and “Show Yourself” both demonstrate the range and power of Idina Menzel’s voice. Both demonstrate Elsa’s magical abilities front and center. Both hit emotional high notes, highlighting Elsa’s psyche and confidence. Both feature grand demonstrations of animation, letting fantasy visuals of snow and ice accompany the music.

“Show Yourself” goes one step beyond emulation. Just like “Let It Go,” Elsa once again constructs a palace out of ice. Once again she lets her hair down and manifests a glamorous gown. Once again the lyrics serve dual purpose, reflecting both Elsa’s current place in the narrative and her subconscious feelings. They may have been eager to replicate the success of “Let It Go”, but this is desperate.

Frozen II establishes its themes early, the same way a musical puts its auditory motifs into an overture. It introduces everything blatantly, even awkwardly, all sequentially in the beginning. It’s not until later, after the story develops and these themes return, do we see their significance. Until then, it just seems as though everyone is speaking in cryptic platitudes.

Anna and Elsa’s mother sings a lullaby whose origins and significance are a secret. Their father tells a bedtime story from his past which he describes in great detail except for the portion regarding himself. Repeated talk about the comfort of familiarity portends a tragic irony. Anna adopts the tenet of doing the next right thing despite the suggestion not being given to her specifically. Olaf insists water has memory completely unprovoked. The apparitions from “Into the Unknown” are literal displays of what’s about to come. There’s foreshadowing, there’s preludes, and there’s whatever’s going on here.

After this prelude to a means, the movie begins in earnest. Arendelle is besieged by strange natural phenomena. Darkness, droughts, strong winds and earthquakes befall the city, forcing an evacuation. Elsa recognizes this as an ultimatum. She’s not only being beckoned to travel north, she’s being forced.

This is our first insistence that Frozen II is departing from its predecessor. The tonal theme shifts wildly. Our fantasy adventure is turning into a tense, atmospheric drama.

Up north, our heroes are tasked with passing through a mist that has isolated Northuldra for years. Not an ordinary fog, this is a magical forcefield. Only Elsa has the ability to pass through, bringing her companions with her.

The impenetrable boundaries. The feeling of imprisonment. The unfamiliar environment. The lack of sky. The strange colors. The impossible wind patterns. The rising panic. The threat of separation. The sense that everyone’s being watched… Don’t let the bright colors and animated characters distract you from the situation at hand. For five whole minutes, Frozen II is coded like a horror movie. This is a film with a singing snowman, but it feels like something made by Alex Garland.

The first film was a personal journey, focusing heavily on Elsa’s character arc. It was an allegorical tale, broaching topics such as mental illness, identity issues, and suppressed trauma. Frozen II keeps its characters mostly static, though the threat of Elsa backsliding into her old ways is on everyone’s mind.

Instead, the focus is on the family history of Arendelle’s royal family. Before, Elsa and Anna’s parents were just parts of a tragic backstory. They were basically stock characters, and didn’t even have names.

Through carefully placed discoveries, revelations and flashbacks, we learn about the life and death of King Agnarr and Queen Iduna. They met the day Northuldra disappeared. They died searching for the same answers Anna and Elsa are now searching for themselves. They don’t know what caused Northuldra to disappear; they don’t understand the magic involved. They suspected the same magic was responsible for Elsa’s powers, and they wanted answers.

But once again, all this was decided after the fact. No one during the production of the original Frozen considered Agnarr and Iduna’s death to have a significant purpose. These new plot details were considered years later, while the old ones were manipulated in order to establish a timeline. As the movie plays out, it’s easy to forget they didn’t die trying to save Northuldra. They were trying to cure Elsa’s magic, still considered a tragic curse at the time of their deaths.