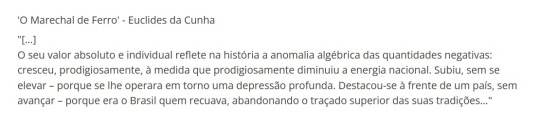

#Euclides da Cunha

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#sertão#história e teoria de uma lei inconstante e polar#euclides da cunha#krieg im sertão#os sertões#campanha de canudos

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A true story

"It is truly regrettable that in these times we do not have a Maudsley, who knew the difference between good sense and insanity, to prevent nations from committing acts of madness and crimes against humanity."

About the Book

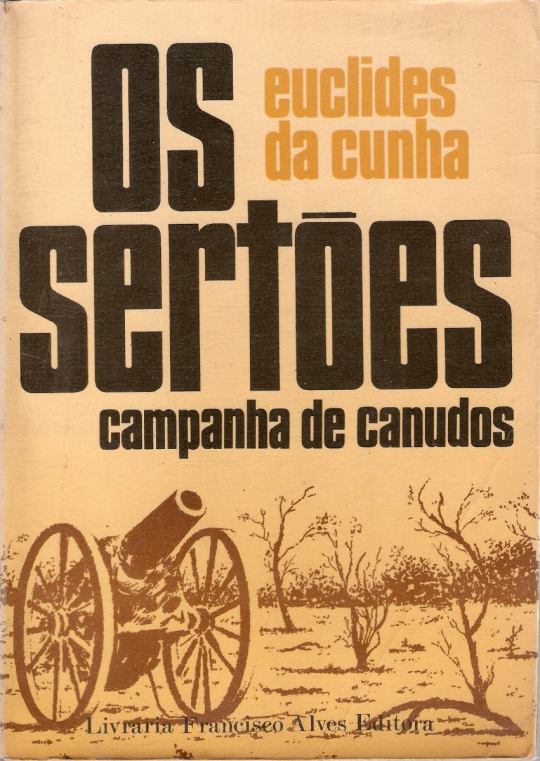

Title: Backlands: The Canudos Campaign or Rebellion in the Backlands Author: Euclides da Cunha Published: 1902 Original Title: Os Sertões

Summary

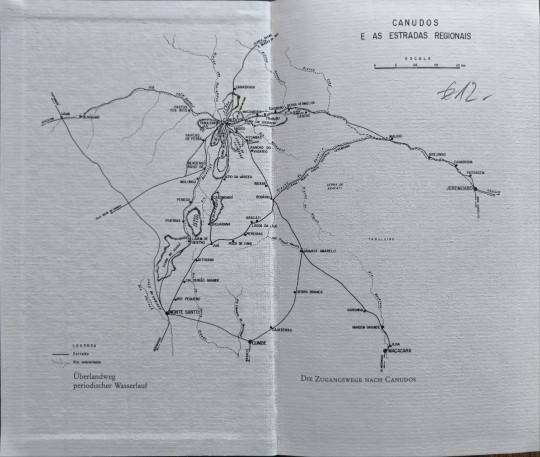

This book is a retelling of the War of Canudos (1896–1897), which took place in the state of Bahia. The writer, Euclides da Cunha, was a correspondent for the Brazilian newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo. It is considered the first livro-reportagem (reportage book) in Brazil. Mixing science and literature, the story narrates the war between the republican army and the sertanejos.

Key Themes

True story

Resistence

War

Brazilian backlands

0 notes

Text

#Euclides da Cunha#O Marechal de Ferro#leitura#citações#literatura#trecho#obras literárias#observação#amplitude#mood#🖤

0 notes

Text

The preface to Verdant Inferno goes hard as fuck

(Euclides da Cunha, Alberto Rangel, Verdant Inferno, pages 14-15)

0 notes

Text

“Canudos não se rendeu. Exemplo único em toda a história, resistiu até o esgotamento completo. Expugnado palmo a palmo, na precisão integral do termo, caiu no dia 5, ao entardecer, quando caíram os seus últimos defensores, que todos morreram. Eram quatro apenas: um velho, dous homens feitos e uma criança, na frente dos quais rugiam raivosamente cinco mil soldados”.⠀Os Sertões, Euclides da Cunha

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

9 Books for 2025!

Tagged by @cdyssey to share 9 books I plan to read in 2025! (thank you kindly <3)

(I have 67 books in my physical TBR and don't generally plan my reading because I never stick to reading plans so take these with a pile of salt)

Le Morte d'Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory - I've had the Norton Critical Edition sitting on my shelf for a little over a year now because it's in Middle English, a thousand pages, and I'm intimidated. But I'm totally gonna start it tomorrow. Hopefully.

Are You My Mother? by Alison Bechdel - Alison Bechdel's memoir about her dad was one of my absolute favorite reads last year and I just got my hands on this one, I'm super excited to read it.

A Ilíada (The Iliad) by Homer (tr. Leonardo Antunes) - Just got my hands on this and I've never read the Iliad, I really like a lot of this translator's work so I wanted this edition in particular.

"Caramba"/"A la vache!" by Getúlio Antero de Deus Júnior - this is a self-published bilingual (Portuguese/French) book of poetry that I did not win in a contest because I couldn't partake but the guy that won it didn't know what to do with it and I'm trying to get good at French, so I bemoaned not getting it and he gave it to me.

Une Femme m'Apparut (A Woman Appeared to Me) by Renée Vivien - I'm hoping to read this close to the end of the year and actually understand it.

Os Sertões (Rebellion in the Backlands) by Euclides da Cunha - it's a non-fiction book written by a reporter about the War of Canudos, it's best known internationally for having inspired The War at the End of the World, I believe. I think I'm gonna love it but I've also heard that it has a lot of uninteresting extraneous stuff so I've been putting it off.

William Shakespeare - I have the Wordsworth Complete Works edition that I'd love to finish this year, but if I read a play a month I'm happy with that (I've only read Macbeth so far and that was last year).

Les Fleurs du Mal by Charles Baudelarie - I was reading an edition in French and a translation in Portuguese in tandem and I need to finish that (I borrowed them from the library, didn't finish, accumulated a lot of fees I was thankfully able to pay by donating a book I hated, anyway I need to borrow it again). I'm gonna be so good at French by the end of this year. Please.

The Evening and the Morning by Ken Follet - Honestly this is a punishment for buying the whole Kingsbridge series before I read the first one (The Pillars of the Earth) because I was so sure I was gonna love it. I have to finish this, I can't take it anymore. At least it doesn't seem as bad as A Column of Fire and Ken Follet seems to have learned about fade to black if not that rape scenes are unneeded.

Tagging @lonely-night @elssbethtascioni @royalarmyofoz @sapphicstaring @aquila1nz

#I have also decided to start trying to read an epic from each country so if you have a public domain suggestion for that please help me#according to my current plans I'll finish when I'm sixty lol

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In 1897, a group of soldiers returned to their hometown of Rio de Janeiro after months in the battlefield. Poor, unemployed, and lacking any kind of government assistance, they settled in one of the city’s poorest areas, then called “Morro da Providência” (Providence Hill). Not long after, due to the overwhelming presence of those destitute soldiers who fought for the Republican Army, the area lost this name and earned a new epithet. Years later its name became a worldwide synonym for disenfranchised urban communities, which it retains until today: Morro da Favela (Favela Hill). Favela or faveleira is a plant common to Brazil’s semiarid regions. Its existence became nationally known as thousands of army personnel – together with cannons, machine guns, and other industrial weaponry – were sent to fight and destroy a backland town in Bahia between 1896 and 1897. Surrounded by these favela plants, the town of Canudos was the stage for one of the bloodiest episodes in Latin American history, which historians reckon left some thirty thousand dead. At the end of the war, newspapers celebrated the progressive forces of the Republic for ridding the country of an unwelcome community of thousands of backland free poor, indigenous people, and the so-called “May 13th” (a derogatory term for formerly enslaved persons who had become free when Brazil passed the emancipation law on May 13, 1888). However, unable to explain how the rebels were able to put up a formidable fight against the country’s official army, many – from contemporaries such as the journalist Euclides da Cunha to twentieth-century academic historians – chose to explain the rebels’ endurance and brave resistance as the effect of a messianic movement. Ignorant and gullible – so the story goes – the poor inhabitants of Bahia’s backlands had become blind followers of a charismatic leader, Antonio Conselheiro, who supposedly had promised them heaven on earth. Such a simplistic explanation, though, not only fails to account for the hazardous impacts of decades-long liberal policies – from land encroachment to criminalizing laws – but also for poor peoples’ ability to understand and resist them. Unwilling to conform, the Canudos rebels were labeled as fanatics and denied a place in modern society. Exclusion in this case, as in many others throughout Latin American history, literally meant demise. The violence of the War of Canudos extended beyond the slaughtering of Bahia’s rebel poor. The very soldiers who committed this massacre returned home to encounter nothing but poverty and exclusion: They became the inhabitants of the Morro da Favela. As it happened so many times in nineteenth-century Latin America, the poor killed one another to further the projects of visionaries who could not care less about the welfare of ordinary men and women. Those who survived the wars the elite had created encountered poverty and exclusion at every turn. But the elites were more than satisfied: Another obstacle – another alternative way of life – had been removed from the path to political and economic 'progress.''"

Monica Dantas; Roberto Saba. Contestations and Exclusions In: The Cambridge History of Latin American Law in Global Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2024.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Machado de Assis no boteco Unica fotografia conhecida de Machado de Assis usando chapéu, no “terrasse” da Confeitaria Castelões, na antiga Avenida Central (atual Avenida Rio Branco), no Rio de Janeiro, em 1907. Na mesa com Machado, Euclides da Cunha, José Veríssimo e Walfrido Ribeiro. Revista Fon-Fon, 1907.

Veja mais em: Semióticas – O Bruxo e a crítica internacional

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was reading this article about Grande Sertão Veredas and politics (Política e violência no grande sertão de Guimarães Rosa) and uh my mind somehow connected the jagunços in the book to the manosphere.

Anyway, if you look the definition of jagunço (and I'm working only with that as I do not know the story and social context of the sertão well), it says "violent man contracted as body guard by an influential man". But if you look the definition of cangaceiro you will find: "armed man who was part of the group ...".

So, there is this notion that to be a jagunço is more of an individual thing. According to the article I was reading, Euclides da Cunha defined jagunço as, for the lack of a better term, unemployed men who sold their bravery. It seems that this whole deal was very transactional. You pay me, I serve you and fight for you.

But in Grande Sertão Veredas this doesn't seem to be the exact case. Riobaldo does mentions how normally jagunços don't make friends with each other or get too close. But the whole deal of working for a politian/landowner wasn't written as that transactional.

As @yonluapple (sorry for tagging you without your permission) said in this post, there is a messianic aspect in the framing of the leaders of the jagunços. Riobaldo talks about how they were great men, basically above the other people who lived at the same time as them. And this is interisting because then being a jagunço becomes less of a job and more of a choice. This great man comes and gives you the opportuninty to join him on his quest of justice and you accept and go along.

And I don't really have the knowledge to talk about how this can be really connected to the manosphere, but besides the violence and misogyny, there is this cult like aspect of those guys. The "alphas" present themselves as better in knowledge, skills, etc. They tell and teach men how to behave, act and think which reminds me of how Riobaldo tells that the way the jagunços behaves depends on the chief. Medeiro Vaz is presented as a very fair and nice guy, so his jagunços treat the people well and are well liked. Hermógenes is basically a monster in Riobaldo's eyes, his men are said to be violent and agressive and do lots of horrible things.

The jagunços' leader is not only an employer but a master showing his devoted servers how to act.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reflections on a Year of Reading Brazilian Literature 🇧🇷

Books Read This Year; Backlands: The Canudos Campaign by Euclides da Cunha, Macunaíma: The Hero With No Character by Mario de Andrade, Hippie by Paulo Coelho and Captains of the Sands by Jorge Amado

All throughout the year, my piece of Brazilian literature mostly focused on the northeastern part of Brazil. In Backlands, I explored the northeastern part of Brazil. With its dry, arid and empty lands, I learned of the mountains and sertões surrounding areas like the Bahia, Alagoas, Pernambuco, Ceara, Piauí and Maranhão. During the summer, the sertão is known for being so dry that even rain is impossible to get. Macunaíma mostly takes place in Brazil's beautiful, lush and dense rainforests with its main character, Macunaíma growing up and living there. Before he became the Hero With No Character, he was thrown away by his mother in a spacious clearing within the beautiful forest. Captains of the Sands takes place in the Bahia, specifically the capital, Salvador. Based on the fact that the Captains lived on a warehouse along the docks of Salvador, I learned that it was somewhat of a coastal city, with beautiful beaches and a lot of vendors surrounding it.

While reading these books, I learned a good amount of Brazilian history. For example, In Backlands, I learned about Antonio Conselheiro, a rebel that led one of the bloodiest uprisings in Brazil. Before this, his family was known as a dangerous family, killing several rich people and pillaging their fortunes. Conselheiro changed that when he decided to become a leader and try to help the northeast be free of southern rule. Macunaíma, however is slightly different. It is neither fully history nor truth, rather a mixture of both. Since almost all of the characters in the book are fake, the events that happen throughout the book are real and always tie in with Macunaíma and his brothers' escapades. Hippie takes place in the 70s and the 70s was a strange time for the world. While reading that book, I learned more about the hippie movement, especially about magic buses, buses that would travel entire continents to get their inebriated passengers to spiritual places like Nepal, for instance. Coelho and his new friend travel from Amsterdam to Kathmandu and on the way, they stop in Constantinople which is now know as Istanbul. I also learned that many. "hippies" were not dedicated to the lifestyle. They merely saw it as a trend and rolled on with the times. Many gave up and returned home to get real jobs and start families after they were done "exploring."

Brazil's culture is very rich and while Hippie doesn't strictly talk about it, Macunaíma does. Many of the adventures Macunaíma and his brothers go on inadvertently cause some shift in Brazilian culture. When Macunaíma first met Ci, the amazon queen of the forest and married her, she later on died and became a star and gave Macunaíma a talisman that was then taken from him and he embarks on a journey to find it. Later on in the book, Macunaíma travels to São Paulo where he attends a festival and talks about the Cruzeiro do Sul and how it is a god, not just a cluster of stars. Mainly, the first few chapters take many things from indigenous culture in Brazil. For example, the author, Mario De Andrade made Macunaíma's catchphrase, "Aí, que preguiça!" which is a fusion of Portuguese and the Tupi language. "Aí," means sloth in Tupi, whereas "preguiça" is the Portuguese word for sloth. This book was also published during Brazil's famous modernism movement. Some say it was one of the founding pieces of literature for the movement. It was published six years after the "Semana de Arte Moderna," and symbolized the beginning of the movement.

From Backlands: The Canudos Campaign, I learned that despite facing difficult odds, in life you must over come that adversity and keep moving on. While reading Macunaíma: The Hero With No Character, I learned that in life, your identity is fluid and it can change many times, so don't try to suppress or change it. In Hippie, I learned that in order to live life, you must embrace the unknown and challenge yourself. Take risks and learn before its too late. Finally, I Captains of the Sands, I learned that I should not let my circumstances dictate who I am or what I am going to be. In life, there will be people who put pressure and doubt your abilities because of where you are from and you shouldn't let that shake your worth.

Some things I learned about myself while reading these books is that I love Brazilian literature. It is incredibly abstract and different than English or American literature. Although some literary works may be difficult to comprehend (mostly because of translation), I think that reading books from a different country can change your previous perspective on a country, it sure changed mine. It made me want to learn more about Brazil and ignited a new flame for Brazilian literature. While I am not done with Captains of the Sands, I will continue to read it because its a well-written book full of humor and societal commentary. This is my OFFICIAL final blog post. Acabou, and muito obrigado. victoriasbrazilianlitblog, out!

Word count: 834

#hippie#brazilian literature#paulocoelho#macunaima#mariodeandrade#jorge amado#brazil#captainsofthesands#bahia

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Euclides da cunha, Os sertões

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wheeling bike em Euclides da Cunha na Bahia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

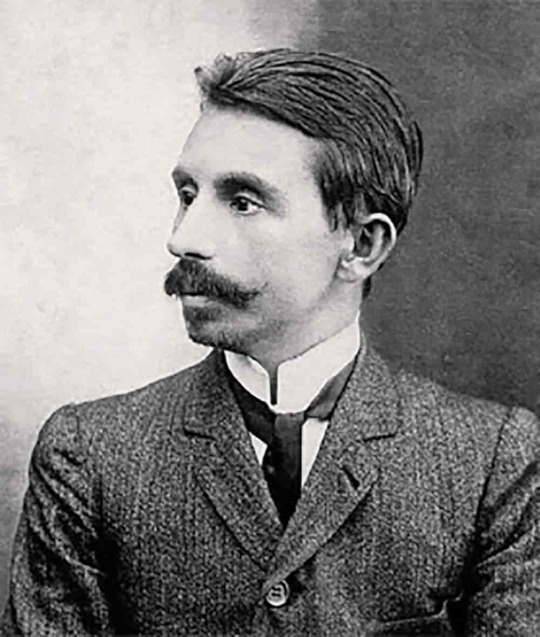

No Dia da Caatinga, 28 de abril, nossa homenagem àquela que é, na opinião de Euclides da Cunha, "a árvore sagrada do sertão": o umbu (Spondias tuberosa). https://bit.ly/spondias

Imagem: https://tinyurl.com/marcgrave

0 notes

Text

CURIOSIDADES LITERÁRIAS:

Você sabia que:

-Aluísio de Azevedo tinha o hábito de, antes de escrever seus romances, desenhar e pintar, sobre papelão, as personagens principais mantendo-as em sua mesa de trabalho, enquanto escrevia.

-Aos dezessete anos, Carlos Drummond de Andrade foi expulso do Colégio Anchieta, em Nova Friburgo (RJ), depois de um desentendimento com o professor de português. Imitava com perfeição a assinatura dos outros. Falsificou a do chefe durante anos para lhe poupar trabalho. Ninguém notou. Tinha a mania de picotar papel e tecidos. "Se não fizer isso, saio matando gente pela rua". Estraçalhou uma camisa nova em folha do neto. "Experimentei, ficou apertada, achei que tinha comprado o número errado. Mas não se impressione, amanhã lhe dou outra igualzinha."

-Numa das viagens a Portugal, Cecília Meireles marcou um encontro com o poeta Fernando Pessoa no café A Brasileira, em Lisboa. Sentou-se ao meio-dia e esperou em vão até as duas horas da tarde. Decepcionada, voltou para o hotel, onde recebeu um livro autografado pelo autor lusitano. Junto com o exemplar, a explicação para o "furo": Fernando Pessoa tinha lido seu horóscopo pela manhã e concluído que não era um bom dia para o encontro.

-Euclides da Cunha, Superintendente de Obras Públicas de São Paulo, foi engenheiro responsável pela construção de uma ponte em São José do Rio Pardo, SP. A obra demorou três anos para ficar pronta e, alguns meses depois de inaugurada, a ponte simplesmente ruiu. Ele não se deu por vencido e a reconstruiu. Mas, por via das dúvidas, abandonou a carreira de engenheiro.

-Gilberto Freyre nunca manuseou aparelhos eletrônicos. Não sabia ligar sequer uma televisão. Todas as obras foram escritas a bico-de-pena, como o mais extenso de seus livros, Ordem e Progresso, de 703 páginas.

-Graciliano Ramos era ateu convicto, mas tinha uma Bíblia na cabeceira só para apreciar os ensinamentos e os elementos de retórica.

Entre outras...

0 notes

Text

PRF apreende 34 celulares sem nota fiscal em ônibus na BR-381

A Polícia Rodoviária Federal (PRF) apreendeu 34 celulares sem nota fiscal, na manhã de quinta-feira (06/03/25), durante fiscalização no km 871 da BR-381, em Pouso Alegre (MG). A apreensão ocorreu por volta das 10h, quando os policiais abordaram um ônibus que fazia a linha São Paulo/SP – Euclides da Cunha/BA. Durante a inspeção no compartimento de bagagens, os PRFs encontraram duas caixas…

0 notes