#Empress Komyo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

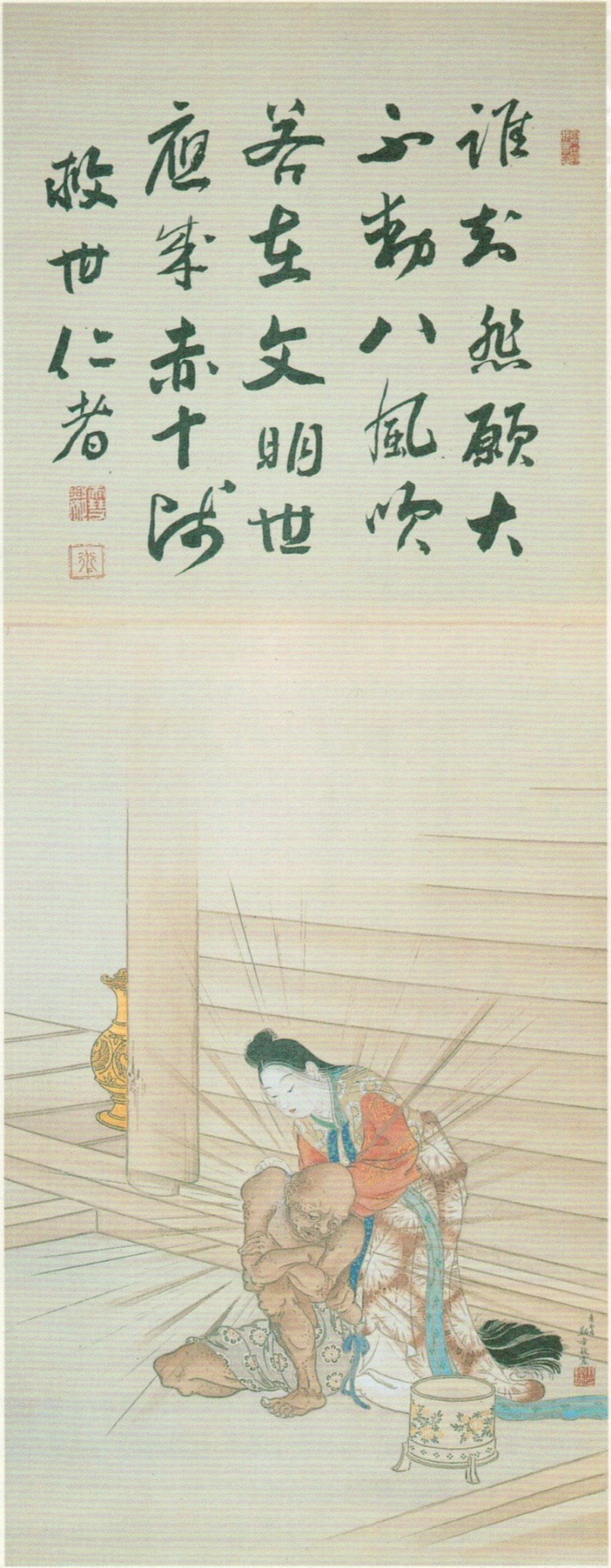

"Portrait of Empress Kōmyō" (光明皇后像) by Kobori Tomoto (小堀鞆音), 1920's, illustrating the scene in which the Empress (701-760) administers a medicinal bath to a leper (actually a divine bodhisattva in disguise) according to her vow at the temple bathhouse she established.

"Retrato de la emperatriz Kōmyō" (光明皇后像) de Kobori Tomoto (小堀鞆音), años 20, que ilustra la escena en la que la emperatriz (701-760) administra un baño medicinal a un leproso (en realidad un bodhisattva divino disfrazado) según su voto en la casa de baños del templo que ella estableció

Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk from the collection of Hokkeji Temple (法華寺) in Nara

Image from "Amamonzeki: A Hidden Heritage: Treasures of the Japanese Imperial Convents" published by the Sankei Shimbun, 2009, page 52

#japanese art#arte japonés#小堀鞆音#kobori tomoto#光明皇后#komyo kogo#empress komyo#奈良市#nara#法華寺#hokkeji#crazyfoxarchives

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Goma-do (護摩堂) and Bell Tower (鐘楼) in the precincts of Hokke-ji (法華寺) in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Empress Komyo#Fujiwara no Fuhito#Hokke-ji Temple#Japan#Karakuen#Nara#travel#国史跡名勝庭園#法華寺#華楽園#藤原 不比等

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

国宝興福寺五重塔 室町時代 高さ五◯、一m

天平二年(七三◯)に光明皇后が創建。現在の塔は応永三十三年(一四二六)に再建。 初層の須弥壇に 薬師三尊像(東) 釈迦三尊像(南) 阿弥陀三尊像(西) 弥勒三尊像(北) を安置(いずれも室町時代作)。

文化財を大切にしましょう。 木柵の中には入らないでください。

The Five Storied Pagoda (National Treasures) This pagoda was constructed by the Empress Komyo in 730. The current building is a restoration completed in 1426, and is the second highest pagoda in Japan, rising 50.1 meters. Inside the structure on the first level, enshrined around the central pillar are a Yakushi triad (to the east), a Shaka triad (to the south), an Amida triad (to the west), and a Miroku triad (to the north).

Vocab 室町時代 (むろまちじだい) Muromachi period (1336-1573) 天平 (てんぴょう) Tenpyo era (8.5.729-4.14.749) 光明皇后 (こうみょうこうごう) Empress Komyo 創建 (そうけん) establishment, foundation 応永 (おうえい) Oei era (7.5.1394-4.27-1428) 須弥壇 (しゅみだん) dais for a Buddhist image 薬師 (やくし) Bhaisajagyuru, Yakushi, the Healing Buddha 三尊 (さんぞん) a Buddhist triad; a Buddha attended by two boddhisatvas 尊像 (そんぞう) statue of a noble character 釈迦(しゃか) Shakyamuni, Gautama Buddha 阿弥陀 (あみだ) Amitabha, Amida 弥勒 (みろく) Maitreya (boddhisatva), Miroku 安置 (あんち) enshrinement, installation (of an image) いずれも all, every 木柵 (もくさく) wooden fence

#日本語#japanese language#japanese vocabulary#japanese langblr#日本#japan#奈良#Nara#仏教#日本歴史#Buddhism#Japanese history

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Empresses of Edo: Exploring the Imperial Palaces of Tokyo

Tokyo, a vibrant metropolis pulsating with neon lights and technological marvels, also holds within its heart a window into Japan's ancient past. Nestled amidst towering skyscrapers lie the Imperial Palaces, a captivating testament to the history and legacy of the Japanese imperial family. While the Emperor remains a significant figure in Japan today, this article delves specifically into the fascinating stories of the empresses who resided within these hallowed halls during the Edo period (1603-1868), with insights provided by a tokyo tour guide.

A Glimpse into the Edo Period:

The Edo period, also known as the Tokugawa period, marked a long era of relative peace and prosperity in Japan. The Tokugawa shoguns wielded immense power, yet the imperial family in Kyoto maintained a symbolic position as the lineage of divine emperors. While the political influence of the empresses during this period was limited, their lives within the secluded Imperial Palace walls were far from ordinary. They played a crucial role in maintaining court traditions, supporting their husbands, and securing the imperial lineage.

The Enigmatic Empresses:

Unfortunately, due to the nature of historical records, details about the lives of individual empresses during the Edo period are often scarce. However, some notable figures emerge from the mists of time, offering a glimpse into the lives of these women shrouded in tradition.

Empress Meisho (1623-1696): One of the few empresses to reign during the Edo period, Meisho ascended the throne at the tender age of seven after her father's unexpected death. Despite the limitations placed upon her due to her gender and age, Meisho is remembered for her artistic pursuits and patronage of court culture.

Empress Kan'ei (1610-1685): Consort to Emperor Go-Mizunoo and mother to Empress Meisho, Kan'ei was the daughter of the second Tokugawa shogun, solidifying the political alliance between the imperial family and the shogunate.

Empress Fujiwara no Kishi (1629-1683): Consort to Emperor Go-Komyo, the father of Emperor Go-Mizunoo, it was Fujiwara no Kishi's lineage connection to the powerful Fujiwara clan that secured her position as empress. Her story highlights the importance of lineage and political alliances within the imperial court.

Beyond the Forbidden Walls:

The Imperial Palaces themselves are an architectural and historical marvel. The current Tokyo Imperial Palace, completed in 1968, stands on the grounds of the Edo Castle, the former seat of power of the Tokugawa shoguns. Within the palace walls lie meticulously maintained gardens, serene courtyards, and traditional buildings that evoke a sense of timelessness. The East Garden, open to the public, offers a glimpse into the tranquil oasis enjoyed by the imperial family.

A Journey Through Time:

Visiting the Imperial Palaces is more than just a sightseeing expedition. It's a journey through time, allowing you to connect with the stories of the empresses who resided within. Here's how to enrich your visit:

Guided Tours: Tours led by knowledgeable English-speaking guides are available on specific days, offering insights into the history and daily life within the palace walls. These tours often include glimpses of the opulent interiors, usually unseen by the public.

Seasonal Events: The Imperial Palace grounds host several seasonal events throughout the year, such as the New Year's greeting by the Emperor and Empress on the balcony, offering a unique opportunity to witness a piece of modern imperial tradition.

The Sannomaru Shogakukan Museum: Located within the palace grounds, this museum houses a collection of artifacts and treasures related to the imperial family, including items that might have been used by the empresses of the Edo period.

The Legacy of the Empresses:

While the Edo period empresses may not have wielded political power, their lives played a crucial role in maintaining the imperial lineage and court traditions. By understanding their stories and exploring the Imperial Palaces, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rich history and cultural tapestry of Japan.

A Final Note:

Visiting the Imperial Palaces in Tokyo is a chance to step back in time, to connect with the stories of the empresses of Edo, and to witness the enduring legacy of the Japanese imperial family. So, on your next visit to Tokyo, don't miss this opportunity to delve into the heart of Japan's fascinating history.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

‘Kingin Denso no Karatachi’

Decorated with crystal, glass and gold lacquer with metal arabesque designs

99.9 centimeters long

(Photos courtesy of Nara National Museum)

“Kokka Chinpo Cho,” a list of Shoso-in items treasured by Emperor Shomu that, upon his death, were dedicated to the Great Buddha statue at Todaiji temple by Empress Komyo (701-760), suggests Kingin Denso no Karatachi came from China’s Tang dynasty (618-907).

https://heritageofjapan.wordpress.com/2011/09/22/shoso-in-exhibition-treasures/

#japan#history#japanese history#sword#artefact#tang#silk road#shosoin treasure#shosoin#nara#nara history#art history#Kingin Denso no Karatachi

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Empress Komyo (Komyoko), from the series "Three Beautiful Women (San bijin)", Ryuryukyo Shinsai, 1815, Art Institute of Chicago: Asian Art

Gift of Helen C. Gunsaulus Size: 21.0 x 18.5 cm Medium: Color woodblock print; shikishiban, surimono

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/81349/

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A painting on hemp which shows Kichijoten, a Buddhist deity of fertility and good fortune, but thought to be modelled on Empress Komyo (l. 701-760 CE). Yakushiji temple, Nara, Japan.

#nara#japan#kichijoten#lakshmi#buddhism#buddha#buddhist#religion#religious#art#archaeology#painting#tang

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Female Oppression within Buddhism in Pre-Modern Japan

Prehistorically, Japanese women have always been viewed as an emblem of fertility and priesthood. Buddhism, introduced to Japan in the Nara Period (710-784), slowly changed how women were portrayed and transformed the former matrilineal society to a patrilineal one. The oppression of women then progressively became very prevalent throughout Japan until the Postwar era (WWII). Expressions of certain myths and ideas contributed to the belief of women’s spiritual inferiority to men. Gender inequality within Buddhist teachings lead to the formation of social gender norms that deny women the chance to make their own decisions. Therefore, Buddhism can be seen as an instrument of patriarchy, used to exclude women and to restrict them of their freedom of thought and action.

Prior to the Nara Period, Japan mainly had a matriarchal social system. Women were seen as a symbol of priesthood and fertility. A woman’s reproductive capability represented strength and power. Spirituality was equal among men and women; both genders were able to reach their peak of spirituality in the same ways and with the same results. Some women were powerful political leaders. For example, Himiko, the Queen of Wa, ruled prehistoric Japan with her brother (189-248). She was in charge of the state’s inner government while her brother was in charge of relations with the outside world. Her leadership confirmed Japan’s earlier matrilineal system and proved the success of a woman’s ability to command. Japanese mythology also played a huge role in the empowerment of women in prehistoric Japan. According to popular tales, Amaterasu was the Japanese goddess of the sun. She was said to have created ancient Japan with her brothers, Susanoo (god of the sea) and Tsukuyomi (god of the moon), and is the direct ancestor of the royal family. Based on her story, Amaterasu showed how influential and self-reliant a woman can be.

Buddhism was introduced to the Japanese state in the Nara Period. Women played a huge part in the spread of this new religious movement. In fact, the first followers to be ordained in Japan were three women, one of which as young as 12 years old (Zenshin). Still in a matrilineal system, Japan produced six female monarchs within the first 200 years after its introduction of the Buddhist institution. These monarchs further expanded the movement by serving as patrons. Empress Komyo became head of the state in 729. As a passionate Buddhist patron, she founded the nunneries, Temples of the Lotus Atonement for Sin, in 741. The name of these nunneries was the first subtle hint at the spiritual inferiority women had to men in Buddhist teachings. It demonstrated the sinful state that women needed to atone for, with attribution to their gender. Nevertheless, during this time period, Buddhism exemplified inclusivity toward women. They were able to follow the institution by becoming, nuns, patrons, laywomen, or devotees. Nihon Ryoiki was a text composed by Kyokai, a monk at Yakushiji (temple in Nara). This written work consisted of tales associated with Buddhist elements, one-third of it being about women within the religious organization. It expresses that women were a representation of compassion and devotion. Stories in the text were of both good and bad women; however, it does not convey women to be impure or sinful. Reproductive women were especially praised since “boundless compassion and motherly love was idealized” (Ambros, Chapter 3).

The Heian Period brought the decline of Buddhist convents and the governmental support for nunneries. Many scholars attribute this phenomenon to the absence of a female monarch as head of the state. Tendai Buddhism was introduced during this era. This new movement did not believe in the training of nuns, excluding them from their corresponding mountain centers (i.e. Mount Hiei). Polygamy was prevalent in the marriage system, allowing men to marry as many concubines as he wanted after his primary wife. Among the elite, women were given various benefits and rights. As a primary wife, the woman and her husband shared an uxorilocal marriage. It meant that the couple resided with her natal family, strengthening her relationship with her parents. The people, during this time period, believed that “women were daughters and sisters before they were wives, mothers, and widows” (Ambros, Chapter 4). Daughters were able to inherit property from their parents and wives from their husbands. Allowance was given out to the mothers and sisters of the male heir of the family.

Although elite women received numerous advantages, a rising negative perception of women occurred in the nobility. At times, women were compared to demons because of their personal thought. Due to social etiquette within the nobility, romantic communication was forbidden in public. Therefore, women tend to restrain their sexuality and feelings of jealousy or lust (demonic emotions). Female oppressive beliefs like the 3 Obediences, the 5 Hindrances, and blood pollution were established in the Heian Period. The 3 Obediences is the idea that women should obey their father in childhood, their husband in marriage, and their son in old age. The 5 Hindrances are five obstacles that prevent a woman from attaining enlightenment: desire, ill-will, dull mind, restlessness, and doubt. Blood pollution is the idea that women are defiled because of their production of blood during childbirth or menstruation. Elite women used their religious commitment to Buddhism to combat the obstructive reputation brought upon them. Ordination marked the end of a woman’s sexual activity, resolving their impure state. Becoming nuns was a way for widows to prove their faithfulness to their husband’s family, since it prevented any future marriages.

During the Kamakura Period, the marriage system transformed from uxorilocal to virilocal. In a virilocal marriage, the couple resides with the husband’s natal family and the wife will eventually integrate into their household. The role of the primary wife strengthened and the relationship between husband and wife grew increasingly significant. The concept of the 3 Obediences gained traction, resulting in women living in the shadows of their male counterparts (father, husband, son). The virilocal marriage system and the rising popularity of the 3 Obediences disempowered women, leading to their ineligibility of inheritance rights. Another ideology introduced was the 7 Sins in females: (1) awakening of sexual lust in men, (2) jealousy and selfishness, (3) deceit and envy, (4) negligence of religious practice, (5) dishonesty, (6) shamelessness, (7) blood pollution. Zen and Pure Land Buddhism were eventually introduced to the Japanese people. Both forms of the Buddhist institution had contradictory attitudes towards the Japanese female population. The Zen priesthood acknowledges the significance and necessity of their female followers to progress the spread of Buddhism. As a result, they supported the ordination of women and the training that follows it. Howbeit, female inferiority was still prevalent in the monastic order; nuns were strictly supervised and managed by clergymen. The Pure Land priesthood welcomed female patrons and laywomen. They disagreed with the exclusion of women at sacred rituals and advocated for female salvation. However, the belief of the 7 Sins was widely accepted as an accurate characterization of women.

In the Edo Period, the patriarchal system began to take root and the oppression of women was at its peak. Privilege deprivation of women in nobility occurs when their inheritance rights are restricted. In a patrilineal household, there is an emphasis on the authority of the male head of the house; women tend to have little to no influence. The interests of each individual family member is subordinate to the interests of the family as a whole. Divorce can only be acquired if the husband commences it. Some women turn to the sanctuary of a Buddhist monastery in hopes that the convent will aid them in negotiating a divorce. Prostitution was viewed as an opposition towards the idea of the patrilineal household. Initially, people saw female sex workers as dutiful daughters who sacrificed themselves for the needs of their family. As the period progressed and prostitution became more widespread, women working in the sex industry were considered as selfish people who rejected the patriarchal system because they desired to gain profit outside of their family. Howbeit, in reality, most prostitutes did not have a say in their chosen line of work. They were usually forced into sex work by the male head of their family. In a sense, these women believed and followed a system that failed them. Although impractical, prostitutes try to join a household through a customer. Becoming a wife was ideal for them because it ensured their survival and the end of their sexual exploitation.

A patriarchal system still existed in the Meiji Period, along with its patrilineal household. The marriage system turned monogamous, terminating the practice of keeping concubines. “Good Wife, Wise Mother” was an ideal devised by Nakamura Masanao, with great influence from the West. The wife in a household was perceived as the “better half” of her husband. It advocated for women’s education, so that they could efficiently support their husbands and teach their kids moral and religious values. This concept emphasized the domestication of women, pushing for them to become exceptional homemakers and mothers. The female population resisted the unfair gender norms that society had put upon them and identified themselves as the “New Woman.” “New Woman” is a term describing an independent woman seeking change in a society that oppresses and domesticates her. Although nuns don’t participate in the institution of marriage or motherhood, educational opportunities for them were also provided for them. Married women’s associations are organizations of laywomen who want to make their mark in certain religious movements. They mainly focus on children and young women, establishing daycares, orphanages, and girls’ schools. These organizations strengthened the idea of femininity and gave women a chance to be publicly active while also assuming the role of a wife and mother.

In conclusion, Buddhism played a major role in the evolution of pre-modern Japan from a matriarchal society to a patriarchal one. From prehistoric times to the end of the Nara Period, women were seen as powerful leaders. Through the portrayal of Amaterasu and Empress Komyo, women were signified as independent and self-reliant and can successfully govern as head of the state. The Heian and Kamakura Periods emphasized the decline in a woman’s social status. Negative perceptions of women started to arise due to the establishment of three disempowering Buddhist ideals: 3 Obediences, 5 Hindrances, and blood pollution. These concepts painted women to be inherently sinful and impure. In Edo and Meiji Periods, the patriarchal system rose to become a state fundamental. The patrilineal household shifts all the power to the male head of the house (generally the husband or the male heir), fully oppressing the female population. Although the “Good Wife, Wise Mother” concept provided educational opportunities for wives and nuns, it aimed for the domestication of women. Through the breakdown of the matriarchy in pre-modern Japan, it is evident that religion was used as an implement to execute the oppression of women and successfully endorse the patriarchy.

Bibliography

Ambros, Barbara R. Women in Japanese Religions. NYU Press, 2015. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt15r3zhw.

Ford, James L. Journal of Japanese Studies, vol. 30, no. 2, 2004, pp. 449–453. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/25064499.

Kawahashi Noriko. “Introduction: Gendering Religious Practices in Japan Multiple Voices,

Multiple Strategies.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 44, no. 1, 2017, pp.

1–13. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/90017628.

Nakamura, Kyōko. “Women and Religion in Japan: Introductory Remarks.” Japanese

Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 10, no. 2/3, 1983, pp. 115–121. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/30233299.

Noriko, Kawahashi. “Feminist Buddhism as Praxis: Women in Traditional Buddhism.”

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, vol. 30, no. 3/4, 2003, pp. 291–313. JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/30234052.

Wacker, Monika. “Research on Buddhist Nuns in Japan, Past and Present.” Asian Folklore

Studies, vol. 64, no. 2, 2005, pp. 287–298., www.jstor.org/stable/30030425.

0 notes

Text

A few protofeminists everyone should know about

This is just a few protofemininists (women who did actions to support the welfare of other women or wrote works that were pro women’s equality in some aspect)

Empress Komyo (701-60) - Japan- established a Buddhist temple that was a shelter for women escaping abusive marriages. This was in a Japan that was changing from a matrifocal egalitarian culture to a patriarchal culture. It’s the first known example of a women’s shelter in the world. (She also established hospitals for the poor in Buddhist temples). Her daughter Empress Koken Shotoku (718-770) last powerful Empress of Japan who ruled in her own right-fought against the court pressures to marry one of her Fujiwara family cousins. (the Fujiwara family was gradually gaining complete control of the court, and would succeed in doing so after her death. They also changed the law after her death, making it almost impossible for a woman to rule in her own right.)

There is a 5 volume manga biography by feminist manga creator Machiko Satonaka about Empress Koken Shotoku called Jotei no Shuki (Notes of an Empress) - sorry, in Japanese only (first published in 1998, republished in 2015, so yes in print)

Helen of Anjou- (1236-1314) France/Serbia- Queen who established women’s schools

Dame Julian of Norwich (1342-1416) -England- Wrote about God as Mother, and that women and men are equal spiritually.

Christine de Pizan (1364-c.1431)-Italy/France- Not only her famous work City of Ladies, and a companion book Treasure of the City of Ladies, but her letters arguing against the misogyny of “Romance of the Rose” and other literary works, letters about the misogyny of priests, and an elegy to Joan of Arc

Anne Askew (1521-1546)-England- protestant martyr who spoke out against the silencing of women and misogynist laws.

Isabella Whitney (c.1545-c.1578)- England- poet and essayist who wrote about the misogyny in relationships and also pioneered using gender neutral pronouns.

Modesta Pozzo/Moderata Fonte (1555-1592)- Italy- poet and essayist. Her works tore down the misogynist images of women in the culture and defended women

Marie de Gournay (1565-1645)- France- Novelist and essayist, wrote in support of women’s equality and against the misogyny in the culture.

Aemilia Lanyer (1569-1645)- England- poet who wrote poems defending women, speaking out against the misogyny in the culture.

Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643)- England/America- female preacher who spoke and believed that women were equal to men spiritually, she was also a believer in free will and that rather than the harsh judgemental authoritarian God of the Puritans she believed in a compassionate God. For this the Puritans put her on trial and exiled her and her followers from the colony.

Aphra Behn (1640-1689)- England- playwrite, poet and spy- wrote in support of women’s equality and also early antislavery writer.

Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz (1651-1695)-Mexico- poet, philosopher nun, who wrote about the misogyny in the culture

Mary Astell (1666-1731)- England- wrote in support of equal education of women.

Abigail Adams (1744-1818)- America- letter writer- her most famous defense of women’s rights the “Remember the Ladies” exchange with her husband John Adams in 1776 and letter to her friend (and future first American historian) Mercy Otis Warren speaking about her disgust at her husband’s dismissal of her strong concerns about how they must include laws giving equal rights to women and laws to protect women from men’s abuses. Stating a wish to create a group devoted to women’s rights. The first known call for women’s rights activism. (Abigail and John preserved their letters to be published after their deaths as historical documents. They have the largest collection of preserved letters of any Revolutionary period people, so large that only recently was a near complete version published of their letters to each other. John, despite his dismissal of her call for women’s equality to be stated in law, otherwise considered her his most trusted advisor and frequently told her she was far more intelligent than him, she also was in charge of all the family finances- and managed them quite well. Upon her death she willed some money to two unmarried nieces to start their own businesses if they wished to. One is known to have definitely done so.)

Olympe de Gouges (1748-1793)- France- playwright and essayist, wrote on both women’s equality and abolition of slavery

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797)- England- Her 1792 book Vindication of the Rights of Women would profoundly influence the first wave feminists in America. (It also known to have encouraged Abigail Adams in her later years. John Adams even addresses her in an 1790′s letter as “his Wollstonecraft”)

Frances Wright (1795- 1852)- Scotland/America- writer and public speaker, spoke on women’s equality, abolition of slavery, birth control, against the social control organized religion had on the culture. The first know female public speaker on these issues in America (1820′s)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

RT ahencyclopedia A painting on hemp which shows Kichijoten, a #Buddhist deity of fertility and good fortune, but thought to be modelled on Empress Komyo (l. 701-760 CE). Yakushiji temple, Nara, #Japan. https://t.co/Tq18lANzW5 https://t.co/jsexbBmDnT

RT ahencyclopedia A painting on hemp which shows Kichijoten, a #Buddhist deity of fertility and good fortune, but thought to be modelled on Empress Komyo (l. 701-760 CE). Yakushiji temple, Nara, #Japan.https://t.co/Tq18lANzW5 pic.twitter.com/jsexbBmDnT

— Ancient History Guy (@ancient_guy) February 15, 2020

from Twitter https://twitter.com/ancient_guy

0 notes

Photo

The Bell Tower (鐘楼) and Goma-do (護摩堂) in the precincts of Hokke-ji (法華寺) in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Empress Komyo#Fujiwara no Fuhito#Hokke-ji Temple#Japan#Karakuen#Nara#travel#国史跡名勝庭園#法華寺#華楽園#藤原 不比等

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese Iris (花しょうぶ) in the Karakuen Garden (華楽園) in the precincts of Hokke-ji (法華寺) in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Empress Komyo#Fujiwara no Fuhito#Hanashōbu#Hokke-ji Temple#Iris ensata#Japan#Japanese Iris#Karakuen#Nara#Nara Prefecture#flowering iris#hanashobu#travel#国史跡名勝庭園#法華寺#花しょうぶ#華楽園#藤原 不比等

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese Iris (花しょうぶ) in the Karakuen Garden (華楽園) in the precincts of Hokke-ji (法華寺) in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Empress Komyo#Fujiwara no Fuhito#Hanashōbu#Hokke-ji Temple#Iris ensata#Japan#Japanese Iris#Karakuen#Nara#Nara Prefecture#flowering iris#hanashobu#travel#国史跡名勝庭園#法華寺#花しょうぶ#華楽園#藤原 不比等

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese Iris (花しょうぶ) in the Karakuen Garden (華楽園) in the precincts of Hokke-ji (法華寺) in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Empress Komyo#Fujiwara no Fuhito#Hanashōbu#Hokke-ji Temple#Iris ensata#Japan#Japanese Iris#Karakuen#Nara#Nara Prefecture#flowering iris#hanashobu#travel#国史跡名勝庭園#法華寺#花しょうぶ#華楽園#藤原 不比等

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Red gate (赤門) and entrance to Hokke-ji (法華寺) in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Empress Komyo#Fujiwara no Fuhito#Hokke-ji Temple#Japan#Karakuen#Nara#travel#国史跡名勝庭園#法華寺#華楽園#藤原 不比等

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Japanese Iris (花しょうぶ) in the Karakuen Garden (華楽園) in the precincts of Hokke-ji (法華寺) in Nara City, Japan.

#Buddhism#Empress Komyo#Fujiwara no Fuhito#Hanashōbu#Hokke-ji Temple#Iris ensata#Japan#Japanese Iris#Karakuen#Nara#Nara Prefecture#flowering iris#hanashobu#travel#国史跡名勝庭園#法華寺#花しょうぶ#華楽園#藤原 不比等

6 notes

·

View notes