#El Paso chihuahuas

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

1 note

·

View note

Text

full moon setting over Juárez, El Paso, Texas / 6.22.24

#photography#fujifilm#full moon#sunrise#mountains#desert#landscape#el paso#texas#ciudad juarez#chihuahua#mexico

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

What did Fort Bliss soldier Saul Luna do to Aylin Valenzuela in Juarez, Mexico?

Aylin Marina Becerril Valenzuela of Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico died at age 19. She lived in El Paso, Texas, United States with her former husband but they separated after having two children together. After the separation, Valenzuela returned to Ciudad Juarez with her two children. They lived with her mother Ysabel Valenzuela. In 2019, Aylin started dating Saul Luna Villa, an American…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

U.S.-Mexico Border Congestion Is Screwing Up The Automotive Industry

Increased border security means crossings have slowed to a crawl. A new wave of migrants from Central and South America looking to escape grave issues in their home countries are reportedly leading to logistical tangles for the automotive industry at the U.S.-Mexico border. At least 19,000 trucks hauling $1.9 billion in goods are currently idling in Mexico, according to Automotive News.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

would it be silly if I write new Lupe lore for this fic and move her farther West bc I wanna talk about desert. I know that it's all headcanon and also that I'm writing an alternate timeline to my other fics but I did establish pretty clearly in the absurdcapybara body of work that Lupe is from Dallas. But the thing is Dallas is so far east of the desert and I think that Jess would like desert. these aren't really genuine questions I just like the desert I wanna write about the desert

#me: Lupe is def a big city kid. dallas is the third largest city in texas and so incredibly urban okay done#me now: but Jess and the desert tho#should I set it in marfa. haha just kidding I still haven't watched i love dick#I've never been to Texas but I have been to the far west side of the Chihuahua and I think it is so beautiful and I like the idea of#geographical shock being a part of Jess' experience in following Lupe home. but Northern/Eastern Texas is like tornado alley similar#in some ways to places Jess would've been bc of the prairieland and humidity#not a bad thing. but less beautiful than describing desert thru a newbie's eyes#I've seen some people place Lupe in western border towns like maybe El Paso. but I still think she's a BIG city kid. San Antonio maybe#close enough to the desert that I could maybe make it work. if we ignore the dallas thing (dallas is lovely tho??!??!!)

1 note

·

View note

Note

Where did he come from and where did he go?

Naturally you are referring to the hero of a popular American folk song about a man named "Ambrose Bierce."

Ambrose Bierce came from Ohio and wrote many books such as "The Devil's Dictionary" (a compilation of silly made up facts) and "Incident At Owl Creek Bridge," in which he invented the twist ending (the Lincoln Memorial turns out to be an ape).

"Where did he go?" is a far more complicated question, and is literally, and this part isn't made up because the reality is so unfathomably absurd, the silliest missing persons case in the history of the world.

In 1913, Bierce did the following things. Again, this isn't made up:

Wrote a letter to his best friend saying "I am going to fight in the Mexican Revolution with Pancho Villa."

Traveled through El Paso into Mexico.

Told numerous people he was headed to the state of Chihuahua to join Pancho Villa in the revolution.

Told numerous people he would likely be executed by firing squad for joining Pancho Villa in the Mexican revolution.

Became the subject of a US Consular investigation that interviewed Pancho Villa's soldiers, who all said Bierce joined the Mexican Revolution and got executed by firing squad in Chihuahua.

Was spoken of by priests near Chihuahua who said that he joined Pancho Villa and was executed by firing squad.

The ludicrous part is that his disappearance is seriously still considered one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of our time.

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

¿Por qué se llaman burritos los tacos de tortilla de harina?

En aquellos años, cuando el Paso del Norte estaba creciendo hasta convertirse en lo que hoy es Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, llegó gente de todas partes a trabajar en las grandes construcciones de la ciudad. Vivía en las montañas un señor llamado Don Juan Méndez, quien comenzó a vender ricos tacos de harina de huevo con frijoles y carne deshebrada (carne de liebre). Se hizo tan popular que toda su familia empezó a trabajar en la preparación de muchos tacos de harina. A tal grado que tuvo que llevar su burra para poder cargar los canastos. La burra y sus crías llevaban dos canastos cada una.

Don Juan llegaba a vender su comida, y la gente gritaba: "¡Llegó el señor de los burritos!", refiriéndose a que los burros o asnos eran su medio de transporte para llegar a su destino con la comida. "¡Llegaron los burritos!", gritaba la gente. Así nació el nombre de esos tacos de harina que todos conocemos como burritos, en el Paso del Norte.

Fuente:

https://es.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burrito_(comida)....

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Se cuenta que durante la Revolución Mexicana, un vendedor llamado Juan Méndez recorría en burro las calles de Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, vendía una peculiar preparación: tacos con enormes tortillas de harinas envueltas y rellenas de frijoles y diversos ingredientes, los tacos se hicieron rápidamente populares, al punto que toda la familia empezó a trabajar en preparar muchos tacos de harina, tantos que se tuvo que llevar a su burrita y sus crías, llevando dos canastos cada una.

Llegaba Don Juan a vender sus tacos y la raza gritaba “llegó el señor de los burritos” refiriéndose a sus animalitos, y así se dice que fue como nació el nombre de esos tacos de harina que todos conocemos hoy como burritos allá en el paso del norte actualmente Ciudad Juárez chihuahua y el señor se llamaba Juan Mendez.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mescalero Apaches were a semi-nomadic people who once roamed the area of New Mexico, West Texas, and Chihuahua. The word "Apache" means "enemy" in the Zuñi language, as they were feared by the pueblo tribes of northern New Mexico as well by the Spanish. The Gila and Chiricahua Apaches were to the west and the Lipan Apaches to the east, but the Mescaleros were once the largest and most powerful Apache nation among them. The Mescaleros are documented archeologically in our region as early as the thirteenth century. They began raiding local Spanish settlements and traveling caravans starting in the 1680s. Between 1778 and 1825 there was a large band of Mescaleros encamped on the future site of Duranguito and Downtown El Paso, peaking at about one thousand men, women and children in the 1790s. The Spanish, Mexicans and Americans all waged wars of extermination against this proud and fierce people. Today the remaining Mescaleros possess a small reservation in southern New Mexico.

TWO YOUNG MESCALERO APACHE MEN, 1888

Photo by A. Frank Randall, Smithsonian, NAA: 2491-a

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 MiLB RBI leaders: week 26 (end of regular season)

10: Andre Lipcius, Oklahoma City (89) 9: Tirso Ornelas, El Paso (89) 8: Jesús Bastidas, Sugar Land (89) 7: Pedro León, Sugar Land (90) 6: Shay Whitcomb, Sugar Land (91) 5: Luke Ritter, Syracuse (93) 4: Johnathan Rodríguez, Columbus (94) 3: Ryan Ward, Oklahoma City (101) 2: Kyle Garlick, Reno (105) 1: Jason Vosler, Tacoma (110)

#Top 10#Sports#Baseball#MiLB#Tacoma Rainiers#Reno Aces#Oklahoma City Dodgers#Columbus Clippers#Syracuse Mets#Sugar Land Space Cowboys#El Paso Chihuahuas#Awesome

0 notes

Text

crossing the international bridge, El Paso-Juárez / 6.20.24

1 note

·

View note

Note

How about Texas' City headcanons?

OOOOO FUN

I actually do have some hc’s for them lol

(btw I hc them to be Texas’s kids so that I have an excuse to include mama bear Texas /silly)

The cities I have hc’s for are mainly the big ones, like El Paso (He/Him), San Antonio (He/Him), Fort Worth (He/Him), Dallas (He/They), Houston (He/Him), Austin (He/They/It, FTM), and Corpus Christi (She/Her, MTF), BUT (hehe butt—), I also have stuff for Nacogdoches (They/Them, AFAB)!!

Nacogdoches is the oldest, and Austin is the youngest! Dallas and Houston are twins cuz they give that vibe for some reason. Corpus Christi is the third oldest, and San Antonio is the second oldest.

When Austin was starting to transition, he was TERRIFIED of telling Texas. Little did he know, Texas is also trans and gave him tips on how to safely transition and was very comforting. Austin ended up crying into his dad’s shoulder for several hours. No Texas did not cry with him. Definitely.

Texas was also plenty supportive when Christi transitioned! He didn’t know much about transitioning from male to female, but he was there to make sure that Christi did so safely.

^if anyone in his government said anything transphobic, they would be silenced very quickly.

San Antonio tries SO HARD to be exactly like Texas. Except he sometimes forgets that Texas isn’t gruff tough and scary 24/7. Also he’s short. So what you have there is an angry chihuahua.

^He’s the shortest of his siblings (5’4). Which is confusing seeing as Texas is 6’5.

Christi is one badass scary woman. All her siblings fear her just a lil bit. So does Texas.

Like Texas, both Austin and San Antonio have bat features! (Ears, tail, and wings)

^Both cities have REALLY large bat populations/colonies, and I’m pretty sure that San Antonio has the largest bat colony in the world! (15,000,000+ bats!)

Austin LOVES animals, just like his dad (fun fact! the largest no-kill animal shelter in the country is located in Austin!)

Nacogdoches was a young native personification when they were found

^Texas was patrolling with a few soldiers, and they found young Nacogdoches hiding. They were going to just kill them, since they obviously weren’t human and it wasn’t clear what they were.

^But Texas interfered and took the child as his own, despite also being really young. He did get punished for doing so, but that doesn’t matter. That is his baby and no one shall harm a single hair on their head lest they want to die.

Anyways. Corpus Christi is the tallest of her siblings, being around 6’4 (since tall women,,,) El Paso is a very close second, being around 6’2.

^SOMEONE (*cough* Houston *cough cough*) complains that he should be the tallest, seeing as he’s the biggest city. (bro Houston is still tall, he’s like- 5’11 😭)

Austin, Fort Worth, Dallas, and Nacogdoches are all 6ft.

There are a ton of comments at the statehouse about how Texas’s kids are all giants (except for San Antonio’s 5’4 angry chihuahua lookin’ ass 💀)

No matter their ages or heights, Texas still holds their hands when crossing the street. ("Mama please I’m 30 years old-" "Shut the fuck up 🥰")

Btw I think that Nacogdoches is just some silly lil fae-like creature cuz they just give that quaint lil forest creature vibe

ANYWAYS

I think I’ll end my rambling here for now, hope you like these hc’s!!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The First Light of Trinity

— By Alex Wellerstein | July 16, 2015 | Annals of Technology

Seventy years ago, the flash of a nuclear bomb illuminated the skies over Alamogordo, New Mexico. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

The light of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. This is because the heat of a nuclear explosion is unlike anything else on Earth. Seventy years ago today, when the first atomic weapon was tested, they called its light cosmic. Where else, except in the interiors of stars, do the temperatures reach into the tens of millions of degrees? It is that blistering radiation, released in a reaction that takes about a millionth of a second to complete, that makes the light so unearthly, that gives it the strength to burn through photographic paper and wound human eyes. The heat is such that the air around it becomes luminous and incandescent and then opaque; for a moment, the brightness hides itself. Then the air expands outward, shedding its energy at the speed of sound—the blast wave that destroys houses, hospitals, schools, cities.

The test was given the evocative code name of Trinity, although no one seems to know precisely why. One theory is that J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of the U.S. government’s laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and the director of science for the Manhattan Project, which designed and built the bomb, chose the name as an allusion to the poetry of John Donne. Oppenheimer’s former mistress, Jean Tatlock, a student at the University of California, Berkeley, when he was a professor there, had introduced him to Donne’s work before she committed suicide, in early 1944. But Oppenheimer later claimed not to recall where the name came from.

The operation was designated as top secret, which was a problem, since the whole point was to create an explosion that could be heard for a hundred miles around and seen for two hundred. How to keep such a spectacle under wraps? Oppenheimer and his colleagues considered several sites, including a patch of desert around two hundred miles east of Los Angeles, an island eighty miles southwest of Santa Monica, and a series of sand bars ten miles off the Texas coast. Eventually, they chose a place much closer to home, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on an Army Air Forces bombing range in a valley called the Jornada del Muerto (“Journey of the Dead Man,” an indication of its unforgiving landscape). Freshwater had to be driven in, seven hundred gallons at a time, from a town forty miles away. To wire the site for a telephone connection required laying four miles of cable. The most expensive single line item in the budget was for the construction of bomb-proof shelters, which would protect some of the more than two hundred and fifty observers of the test.

The area immediately around the bombing range was sparsely populated but not by any means barren. It was within two hundred miles of Albuquerque, Santa Fe, and El Paso. The nearest town of more than fifty people was fewer than thirty miles away, and the nearest occupied ranch was only twelve miles away—long distances for a person, but not for light or a radioactive cloud. (One of Trinity’s more unusual financial appropriations, later on, was for the acquisition of several dozen head of cattle that had had their hair discolored by the explosion.) The Army made preparations to impose martial law after the test if necessary, keeping a military force of a hundred and sixty men on hand to manage any evacuations. Photographic film, sensitive to radioactivity, was stowed in nearby towns, to provide “medical legal” evidence of contamination in the future. Seismographs in Tucson, Denver, and Chihuahua, Mexico, would reveal how far away the explosion could be detected.

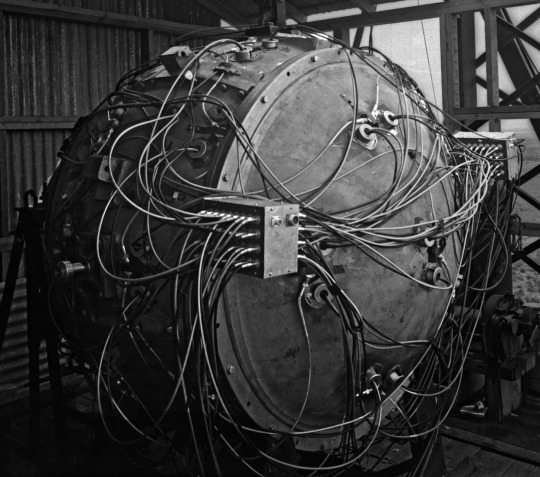

The Trinity test weapon. Courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory

On July 16, 1945, the planned date of the test, the weather was poor. Thunderstorms were moving through the area, raising the twin hazards of electricity and rain. The test weapon, known euphemistically as the gadget, was mounted inside a shack atop a hundred-foot steel tower. It was a Frankenstein’s monster of wires, screws, switches, high explosives, radioactive materials, and diagnostic devices, and was crude enough that it could be tripped by a passing storm. (This had already happened once, with a model of the bomb’s electrical system.) Rain, or even too many clouds, could cause other problems—a spontaneous radioactive thunderstorm after detonation, unpredictable magnifications of the blast wave off a layer of warm air. It was later calculated that, even without the possibility of mechanical or electrical failure, there was still more than a one-in-ten chance of the gadget failing to perform optimally.

The scientists were prepared to cancel the test and wait for better weather when, at five in the morning, conditions began to improve. At five-ten, they announced that the test was going forward. At five-twenty-five, a rocket near the tower was shot into the sky—the five-minute warning. Another went up at five-twenty-nine. Forty-five seconds before zero hour, a switch was thrown in the control bunker, starting an automated timer. Just before five-thirty, an electrical pulse ran the five and a half miles across the desert from the bunker to the tower, up into the firing unit of the bomb. Within a hundred millionths of a second, a series of thirty-two charges went off around the device’s core, compressing the sphere of plutonium inside from about the size of an orange to that of a lime. Then the gadget exploded.

General Thomas Farrell, the deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, was in the control bunker with Oppenheimer when the blast went off. “The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun,” he wrote immediately afterward. “It was golden, purple, violet, gray, and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse, and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.” Twenty-seven miles away from the tower, the Berkeley physicist and Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence was stepping out of a car. “Just as I put my foot on the ground I was enveloped with a warm brilliant yellow white light—from darkness to brilliant sunshine in an instant,” he wrote. James Conant, the president of Harvard University, was watching from the V.I.P. viewing spot, ten miles from the tower. “The enormity of the light and its length quite stunned me,” he wrote. “The whole sky suddenly full of white light like the end of the world.”

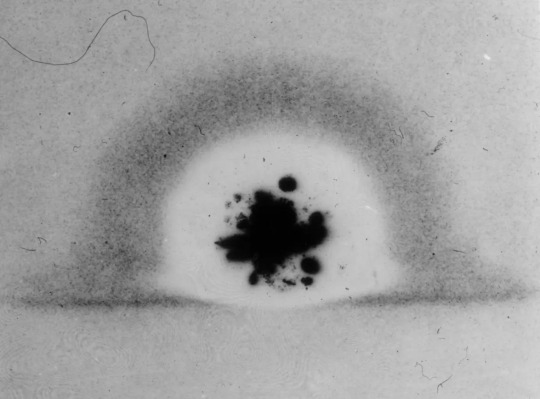

In its first milliseconds, the Trinity fireball burned through photographic film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

Trinity was filmed exclusively in black and white and without audio. In the main footage of the explosion, the fireball rises out of the frame before the cameraman, dazed by the sight, pans upward to follow it. The written accounts of the test, of which there are many, grapple with how to describe an experience for which no terminology had yet been invented. Some eventually settle on what would become the standard lexicon. Luis Alvarez, a physicist and future participant in the Hiroshima bombing, viewed Trinity from the air. He likened the debris cloud, which rose to a height of some thirty thousand feet in ten minutes, to “a parachute which was being blown up by a large electric fan,” noting that it “had very much the appearance of a large mushroom.” Charles Thomas, the vice-president of Monsanto, a major Manhattan Project contractor, observed the same. “It looked like a giant mushroom; the stalk was the thousands of tons of sand being sucked up by the explosion; the top of the mushroom was a flowering ball of fire,” he wrote. “It resembled a giant brain the convolutions of which were constantly changing.”

In the months before the test, the Manhattan Project scientists had estimated that their bomb would yield the equivalent of between seven hundred and five thousand tons of TNT. As it turned out, the detonation force was equal to about twenty thousand tons of TNT—four times larger than the expected maximum. The light was visible as far away as Amarillo, Texas, more than two hundred and eighty miles to the east, on the other side of a mountain range. Windows were reported broken in Silver City, New Mexico, some hundred and eighty miles to the southwest. Here, again, the written accounts converge. Thomas: “It is safe to say that nothing as terrible has been made by man before.” Lawrence: “There was restrained applause, but more a hushed murmuring bordering on reverence.” Farrell: “The strong, sustained, awesome roar … warned of doomsday and made us feel that we puny things were blasphemous.” Nevertheless, the plainclothes military police who were stationed in nearby towns reported that those who saw the light seemed to accept the government’s explanation, which was that an ammunition dump had exploded.

Trinity was only the first nuclear detonation of the summer of 1945. Two more followed, in early August, over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing as many as a quarter of a million people. By October, Norris Bradbury, the new director of Los Alamos, had proposed that the United States conduct “subsequent Trinity’s.” There was more to learn about the bomb, he argued, in a memo to the new coördinating council for the lab, and without the immediate pressure of making a weapon for war, “another TR might even be FUN.” A year after the test at Alamogordo, new ones began, at Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands. They were not given literary names. Able, Baker, and Charlie were slated for 1946; X-ray, Yoke, and Zebra were slated for 1948. These were letters in the military radio alphabet—a clarification of who was really the master of the bomb.

Irradiated Kodak X-ray film. Courtesy National Archives and Records Administration

By 1992, the U.S. government had conducted more than a thousand nuclear tests, and other nations—China, France, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union—had joined in the frenzy. The last aboveground detonation took place over Lop Nur, a dried-up salt lake in northwestern China, in 1980. We are some years away, in other words, from the day when no living person will have seen that unearthly light firsthand. But Trinity left secondhand signs behind. Because the gadget exploded so close to the ground, the fireball sucked up dirt and debris. Some of it melted and settled back down, cooling into a radioactive green glass that was dubbed Trinitite, and some of it floated away. A minute quantity of the dust ended up in a river about a thousand miles east of Alamogordo, where, in early August, 1945, it was taken up into a paper mill that manufactured strawboard for Eastman Kodak. The strawboard was used to pack some of the company’s industrial X-ray film, which, when it was developed, was mottled with dark blotches and pinpoint stars—the final exposure of the first light of the nuclear age.

#Hiroshima | Japan 🇯🇵 | John Donne | Manhattan Project | Monsanto#Nagasaki | Japan 🇯🇵 | Nuclear Weapons | Second World War | World War II#The New Yorker#Alex Wellerstein#Los Alamos National Laboratory#New Mexico#J. Robert Oppenheimer#John Donne#Jean Tatlock#University of California Berkeley#Jornada del Muerto | Journey of the Dead Man#General Thomas Farrell#Nobel Prize Winner Physicist Ernest O. Lawrence#Luis Alvarez#US 🇺🇸#China 🇨🇳#France 🇫🇷#Soviet Union (Now Russia 🇷🇺)#Alamogordo | New Mexico#Eastman Kodak#Nuclear Age

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sepultan al Héroe del Carrizal……… Hoy 25 de junio es sepultado en el panteón Del Refugio del pueblo de Gómez Farías Coahuila, el general Félix U. Gómez, en el año de 1916 a sus 29 años de edad, el general cambio su nombre, ya que se llamaba Félix Gómez Uresti, pero se cree que hace el cambio luego que su madre Celsa Uresti se casa de nuevo y su tío, Marcos Uresti, se lo lleva a Zacatecas y en agradecimiento antepone el apellido materno, este saltillense carrancista, era un hombre corpulento de dos metros de estatura. al invadir E.U. a México, en la llamada Expedición Punitiva, 10000 soldados y 8 aeroplanos, buscando inútilmente a Villa, por lo que les hizo en Columbus Nuevo México, el general Félix Uresti Gómez tenía órdenes de no permitir el paso de tropas americanas más allá del poblado del Carrizal, municipio de Villa Ahumada Chihuahua a 140 kilómetros al sur de Ciudad Juárez. El comandaba la brigada Canales, del ejército federal carrancista, por lo que detiene la marcha de dos escuadrones norteamericanos comandados por los capitanes, Lewis S. Morey, y Charles T. Boyd, a quienes convida regresar, señalándoles que no podrán pasar más allá del Carrizal a lo que el capitán Boyd responde de cualquier modo pasare, pues si no le da paso él se lo abrirá para ello tengo mi tropa, a lo que el general mexicano contesto tendrá que pasar por sobre el cadáver del último de mis soldados. Acto seguido ambos jefes se retiran para iniciar la batalla, la cual se llevó a cabo el 21 de junio de 1916, el oficial extranjero dispuso la orden de batalla, el general Félix regreso donde lo esperaba su tropa y se dispuso a la defensa, enseguida se escuchó una descarga de fusilería que derribo a los jinetes mexicanos entre ellos el propio general Félix U. Gómez, el teniente coronel Genovevo Rivas Guillen, asumió el mando de las acciones ordeno un envolvimiento por el flanco izquierdo conducido por el mismo, en tanto la única ametralladora que poseían los mexicanos detenían el avance enemigo el cual cobro la vida del capitán Boyd, el combate duro 2 horas, las brigadas de E.U. se rindieron. Las acciones de guerra cobraron la vida del general Félix U. Gómez, el capitán Fco. Rodríguez, el teniente Daniel García, el teniente Evaristo Martínez y el subteniente Juan Lerdo y 26 soldados más, por parte de los gringos cayeron el capitán Boyd y el teniente Adair y más de 50 muertos y 17 prisioneros el resto huyo además de un buen número de pertrechos de guerra. Al día siguiente se dispuso trasladar el cadáver del general Félix U. Gómez a Coahuila, de Chihuahua sale un convoy de trenes llevando el cadáver del general al modesto pueblo de Gómez Farías, municipio de Saltillo Coahuila, donde lo esperaba su esposa Magdalena Hernández y su pequeño hijo de 2 años de edad. Fue velado y sepultado el 25 de junio de 1916. En nuestra entidad existe un busto en honor al general Félix Uresti Gómez, la primera piedra del monumento de cantera, fue colocada el 16 de septiembre de 1918 -estando todavía frescos en la memoria los sucesos-, siendo gobernador del estado el general brigadier Ignacio C. Enríquez, y fue terminado el 21 de diciembre de ese mismo año. El monumento quedó frente al antiguo local de la Sociedad Chihuahuense de Estudios Históricos, justo atrás de la Quinta Touché y enfrente de la Preparatoria Allende. Este monumento fue gracias a miembros de la Unión de Tipógrafos Chihuahuenses que rindieron homenaje con la erección de una columna triunfal que pagaron por suscripción popular.

2 notes

·

View notes