#Edward Steichen The Flatiron 1905

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Edward Steichen (American, 1879–1973)

The Flatiron - Evening, 1905

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Steichen The Flatiron

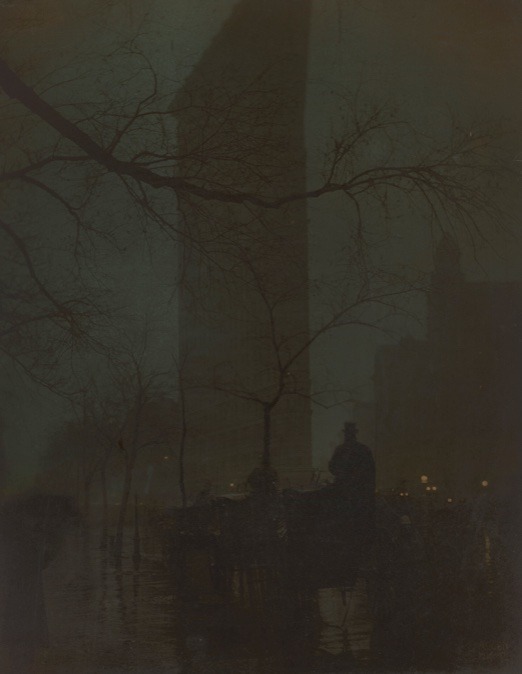

Signed and dated 'Steichen MDCCCCV' (lower right). Gum-bichromate over platinum print. Sheet: 19 x 14 3/4 in. (48.3 x 37.5 cm.). 1904, printed 1905.

#Edward Steichen#Edward Steichen The Flatiron 1905#american photographer#print#art#artist#art work#art world#art news

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward Steichen. The Flatiron (taken in 1904 and printed in 1905) an iconic photo of New York, has sold for $11.8 million, making it the second-most expensive photograph ever sold.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Flatiron Building, New York, 1905 - by Edward Steichen (1879 - 1973), American

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Steichen, “The Flatiron” (1904, printed 1905),

Signed and dated 'Steichen MDCCCCV' (lower right),

Gum-bichromate over platinum print,

Sheet: 19 x 14 3/4 in. (48.3 x 37.5 cm.)

The Paul G. Allen Collection Part I / Christie’s

#art#vintage photography#Street Photography#still life photography#edward steichen#latiron#1904#platinium print#paul G. Allen#chritie's#iconic

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Flatiron (1905) - Edward Steichen

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Steichen – The Flatiron Building, New York (1905).

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Steichen The Flatiron Building, New York City-Evening 1905

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Steichen The Flatiron - Evening, 1905 Three-color halftone print from Camera Work on the original double-mount leaf 8 2/5 × 6 2/5 in

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Photographic Art. From LIFE’s “100 Photographs That Changed The World”. 1) Eugene Atget - Organ Player and Singing Girl. A frustrated actor, Atget considered turning to painting. But he took up the camera instead and quickly showed himself to be a genius of composition. For 30 years, Atget’s grail was to capture all that was picturesque in the city he loved, Paris. 2) Edward Steichen - The Flatiron, Evening 1905. He did portraits, landscapes, fashion photography, even advertising work, all of it marked by a strong sense of design. #history #photograph #colorphotography #blackandwhitephoto #camerahistory https://www.instagram.com/p/CV3P7jULUh-/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

Edward Steichen, The Flatiron, New York, 1905

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edward Steichen. The Flatiron Building, 1905.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Flatiron building, New York, 1905 - photo by Edward Steichen.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Photograph That Launched Edward Steichen’s Career

Moonlight: The Pond, 1904. Edward Steichen Phillips

In 1895, Éduard J. Steichen was a 16-year-old living in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who’d just bought his first camera and had taken to kicking his tripod to give his images an evocative blur. The notion that he’d create a picture deemed a masterwork—or the encapsulation of a photographic movement, at that—was far-flung. But The Pond—Moonrise (1904), his tranquil photograph of woods gently reflected in a lustrous moonlit pond, shot less than a decade later, became just that: an exemplary vision of Pictorialism, and a symbol of photography’s quest for legitimacy as an art form.

How he arrived at this outcome, surprisingly, was via a relatively unbending path. “We occasionally find ourselves in darker parts of the world, and, as a rule, feel more easy there,” he reflected in 1901, three years prior to the creation of the famous nocturne. “What a beautiful hour of the day is that of the twilight when things disappear and seem to melt into each other, and a great beautiful feeling of peace overshadows all. Why not, if we feel this, have this feeling reflect itself in our work?”

Éduard, who later changed the spelling of his name to Edward, was, by all accounts, an early adopter of the arts. At age 15, he began a four-year apprenticeship at a lithography firm, and in addition to taking up photography the following year, he had already sketched and painted in his free time. He read Camera Notes, a quarterly photography publication run by Alfred Stieglitz, and in his own work eschewed straight, mundane images, which were gaining widespread popularity with the advent of point-and-shoot Kodak cameras. At age 21, in 1900, he left home for Paris to study painting at Académie Julian, but stopped over in New York, where he introduced himself to Stieglitz, and sold him three soft-focus platinum prints (two were pictures of the woods) for the highest price the young artist had ever garnered: five dollars per image (around $140 each at the time). In Paris, he discontinued his painting studies in favor of photographing portraits, establishing relationships with artists such as Auguste Rodin and Pablo Picasso.

M. Auguste Rodin, 1911. Edward Steichen Brooklyn Museum

The Maypole, Empire State Building, New York, 1932. Edward Steichen Etherton Gallery

The year 1902, during which Steichen returned to New York, was a formative time in both his career and in photographic history. He was one of a dozen photographers, including Stieglitz, Gertrude Käsebier, and Clarence H. White, who joined together to establish the Photo-Secession movement. Together, these photographers advocated for photography’s worth as a fine art, and often used laborious printing processes to express its potential beyond its everyday, mechanical use.

As curator Dennis Longwell noted in the Museum of Modern Art catalog Steichen: The Master Prints 1895–1914, at that moment, “the criteria for judging the aesthetic worth of a photograph were borrowed in large part from the standards, the critical mechanisms, used to evaluate other works of art,” such as painting; and that Symbolist ideology, “in both its literary and its pictorial manifestations, dominated the progressive critical thought of the day.”

In turn, the Photo-Secessionists also embraced Pictorialism, favoring its painterly aesthetic, atmospheric tone, and redolent potential. They dismissed photography’s claim to objectivity, and in the inaugural issue of Camera Work—Stieglitz’s follow-up to Camera Notes, first published in January 1903—Steichen insisted that “every photograph is a fake from start to finish, a purely impersonal, unmanipulated photograph being practically impossible.”

Dana Steichen's Hands, 1923. Edward Steichen Boca Raton Museum of Art

Anna May Wong, NY, 1930. Edward Steichen Gallery 270

Steichen had already made use of various innovative printing techniques over the years, and embraced the evocative ambiguity of murky images. But Moonrise is perhaps the moment that he most seamlessly blended a romantic subject and experimental process. It was shot in the summer of 1904 when Steichen, his wife, and newborn daughter took a break from New York City. They visited Steichen’s friend, the English art critic Charles Henry Caffin, at his home in the woodsy town of Mamaroneck in Westchester County, New York.

Where the image was taken, however, matters little to the final product. As curator Russell Lord observed in Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop, the photograph is located in a more figurative place, and is “meant to hover like a distant memory, somewhere between the familiar and the uncanny.” Moonrise is at once realistic and dreamlike, and has the effect of seeming to slow down one’s surroundings.

The profundity of the ordinary natural scene is a credit to the manner in which its three iterations—all of which are platinum prints, measuring approximately 16 by 19 inches—were created. Using the same negative, Steichen alternately employed the technique of multiple printing with applied coloring; a ferroprussiate, or cyanotype, treatment lending a twilight hue; and a gum-bichromate process, resulting in a greenish tint. While the results vary, they all possess a quality that Anthony Lane pinpointed in The New Yorker in 1998: “Only Steichen had the skill, and the wit, to redefine the photograph as a kind of miniature monument, a repository of pensive peace.”

The Flatiron - Evening, 1905. Edward Steichen Phillips

Vogue June 1 1928, . Edward Steichen Isabella Garrucho Fine Art

The following year, Steichen would notably photograph New York’s Flatiron Building (The Flatiron—Evening, 1904)—a new skyscraper completed only three years prior—with a similarly rich, moody treatment. The great outdoors and the city were both subject to his Pictorialist approach, but Steichen would not define himself by this style in the ensuing years. After Moonrise, he gradually moved toward Modernism, at a time when practitioners of photography no longer had to defend its validity as forcefully.

In the coming decades, Steichen would find new uses for his photographic skills—from serving in the military as an aerial photographer in World War I, to his subsequent work in advertising, to being hired as Condé Nast’s chief photographer (focusing on celebrity and fashion), only to land at the Museum of Modern Art as the director of photography in 1947. One characteristic that remained constant throughout Steichen’s mutations was lack of aesthetic complacency. As Caffin aptly observed in the April 1910 issue of Camera Work, Steichen was “somewhat arrogantly intolerant of the commonplace; rapturously devout toward that which is choicely beautiful.”

from Artsy News

0 notes

Photo

The Flatiron building, New York, 1905 - photo by Edward Steichen. #melancholy #apathy #sonder #saudade #noir #neonoir #b&w #karachi #karachidiaries http://ift.tt/2niLXGL

0 notes

Photo

The Flatiron building, New York, 1905 – photo by Edward Steichen. #melancholy #apathy #sonder #saudade #noir #neonoir #b&w #karachi #karachidiaries from Instagram:

0 notes