#Edmund Pettis Bridge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

James Karales’ photograph of the Selma to Montgomery march for voting rights, Alabama, 1965 (via here)

* * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

March 6, 2024

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

MAR 7, 2024

Black Americans outnumbered white Americans among the 29,500 people who lived in Selma, Alabama, in the 1960s, but the city’s voting rolls were 99% white. So, in 1963, Black organizers in the Dallas County Voters League launched a drive to get Black voters in Selma registered. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a prominent civil rights organization, joined them.

In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, but the measure did not adequately address the problem of voter suppression. In Selma a judge had stopped the voter registration protests by issuing an injunction prohibiting public gatherings of more than two people.

To call attention to the crisis in her city, Amelia Boynton, who was a part of the Dallas County Voters League but who, in this case, was acting with a group of local activists, traveled to Birmingham to invite Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., to the city. King had become a household name after the 1963 March on Washington where he delivered the “I Have a Dream” speech, and his presence would bring national attention to Selma’s struggle.

King and other prominent members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference arrived in January to push the voter registration drive. For seven weeks, Black residents tried to register to vote. County Sheriff James Clark arrested almost 2,000 of them for a variety of charges, including contempt of court and parading without a permit. A federal court ordered Clark not to interfere with orderly registration, so he forced Black applicants to stand in line for hours before taking a “literacy” test. Not a single person passed.

Then on February 18, white police officers, including local police, sheriff’s deputies, and Alabama state troopers, beat and shot an unarmed 26-year-old, Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was marching for voting rights at a demonstration in his hometown of Marion, Alabama, about 25 miles northwest of Selma. Jackson had run into a restaurant for shelter along with his mother when the police started rioting, but they chased him and shot him in the restaurant’s kitchen.

Jackson died eight days later, on February 26.

The leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Selma decided to defuse the community’s anger by planning a long march—54 miles—from Selma to the state capitol at Montgomery to draw attention to the murder and voter suppression. Expecting violence, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee voted not to participate, but its chair, John Lewis, asked their permission to go along on his own. They agreed.

On March 7, 1965, the marchers set out. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Confederate brigadier general, Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan, and U.S. senator who stood against Black rights, state troopers and other law enforcement officers met the unarmed marchers with billy clubs, bullwhips, and tear gas. They fractured John Lewis’s skull and beat Amelia Boynton unconscious. A newspaper photograph of the 54-year-old Boynton, seemingly dead in the arms of another marcher, illustrated the depravity of those determined to stop Black voting.

Images of “Bloody Sunday” on the national news mesmerized the nation, and supporters began to converge on Selma. King, who had been in Atlanta when the marchers first set off, returned to the fray.

Two days later, the marchers set out again. Once again, the troopers and police met them at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, but this time, King led the marchers in prayer and then took them back to Selma. That night, a white mob beat to death a Unitarian Universalist minister, James Reeb, who had come from Massachusetts to join the marchers.

On March 15, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed a nationally televised joint session of Congress to ask for the passage of a national voting rights act. “Their cause must be our cause too,” he said. “[A]ll of us…must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.” Two days later, he submitted to Congress proposed voting rights legislation.

The marchers remained determined to complete their trip to Montgomery, and when Alabama’s governor, George Wallace, refused to protect them, President Johnson stepped in. When the marchers set off for a third time on March 21, 1,900 members of the nationalized Alabama National Guard, FBI agents, and federal marshals protected them. Covering about ten miles a day, they camped in the yards of well-wishers until they arrived at the Alabama State Capitol on March 25. Their ranks had grown as they walked until they numbered about 25,000 people.

On the steps of the capitol, speaking under a Confederate flag, Dr. King said: “The end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.”

That night, Viola Liuzzo, a 39-year-old mother of five who had arrived from Michigan to help after Bloody Sunday, was murdered by four Ku Klux Klan members who tailed her as she ferried demonstrators out of the city.

On August 6, Dr. King and Mrs. Boynton were guests of honor as President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Recalling “the outrage of Selma,” Johnson said: "This right to vote is the basic right without which all others are meaningless. It gives people, people as individuals, control over their own destinies."

The Voting Rights Act authorized federal supervision of voter registration in districts where African Americans were historically underrepresented. Johnson promised that the government would strike down “regulations, or laws, or tests to deny the right to vote.” He called the right to vote “the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice and destroying the terrible walls which imprison men because they are different from other men,” and pledged that “we will not delay, or we will not hesitate, or we will not turn aside until Americans of every race and color and origin in this country have the same right as all others to share in the process of democracy.”

As recently as 2006, Congress reauthorized the Voting Rights Act by a bipartisan vote. By 2008 there was very little difference in voter participation between white Americans and Americans of color. But then, in 2013, the Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder decision got rid of the part of the Voting Rights Act that required jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination in voting to get approval from the federal government before changing their voting rules. This requirement was known as “preclearance.”

The Shelby County v. Holder decision opened the door, once again, for voter suppression. Since then, states have made it harder to vote; in 2023, at least 14 states enacted 17 restrictive voting laws. A recent study by the Brennan Center of nearly a billion vote records over 14 years shows that the racial voting gap is growing almost twice as fast in places that used to be covered by the preclearance requirement.

Democrats have tried since 2021 to pass a voting rights act but have been stymied by Republicans, who oppose such protections. Last September, on National Voter Registration Day, House Democrats reintroduced a voting rights act, now named the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act after the man who went on from his days in the Civil Rights Movement to serve 17 terms as a representative from Georgia, bearing the scars of March 7, 1965, until he died on July 17, 2020.

On March 1, 2024, 51 Democratic senators introduced the measure in the Senate.

Speaking in Selma last Sunday at the commemoration of the 59th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, Vice President Kamala Harris shared that the first thing she sees on walking into her office is a “large framed photograph taken on Bloody Sunday depicting an injured Amelia Boynton receiving care at the foot of [the Edmund Pettus] bridge.”

“[F]or me,” she said, “it is a daily reminder of the struggle, of the sacrifice, and of how much we owe to those who gave so much before us.”

“History is a relay race,” she said. “Generations before us carried the baton. And now, they have passed it to us.”

—

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#Bloody Sunday#Selma To Montgomery#history#Letters from an American#Heather Cox Richardson#voting#voting rights#voting rights act#Edmund Pettis Bridge#Civil Rights Act

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

AMERICAN HISTORY NOTES 11/9

9 black students going to class at Little Rock high on September 5, 1927

They were met with violence

Mayor of Little Rock had personally contacted Eisenhower (president) and said he wanted military help because the governor asked for the national guard to prevent any black people into entering

The army trumps the national guard

Orville declares he will fight segregation anywhere he goes and will not allow for racism in any state (against his power)

George C Wallace, governor of Alabama, awful man

Doctors did not need to tell women what was wrong with them, but would tell the men

Irene Wallace had cancer, but George didn't tell her. She ended up figuring out herself and was upset at him, which confused him. DUMBASS

George C Wallace stood on the balcony of Alabama and that balcony is a famous location

He declared a speech of segregation now and forever!!!!!!

He said the same thing over and over again

That's all he said for the 1960's

Later in life, he came to Jesus moment, and apologized publicly towards the end of life for being racist and tried to make amends with African Americans in Alabama. Some even forgave him.

In the end he tried to make things right, but the consequences remained

Emmett Till, 1941-1955 (only 14 years old), he was beaten and then killed by two men after apparently 'whistling' at someone's wife. Everyone knew who it was. The FBI knew who did it.

The two men were arrested and were found not guilty from an all white court. They laughed and joked as they left about doing that to a fourteen black boy.

He paid the price for white supremacy and his mother insisted on an open casket for the world to see

White America finally went what is going down on the South: What is this, why is this happening?

FUCK THE KILLERS RAHHHHHHHHHHH

This dumb bitch admitted he never whistled and was respectful. Fucking dumb whore THAT DONT CHANGE SHIT

Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, 1929-1968

Rosa Parks, 1913-1992

Started the bus boycott

Refused to give up her seat and was arrested

This wasn't a spontaneous thing, she had volunteered to do this and worked with the leadership of the Civil Rights movement to do this

Bus boycott continued for 1 year and 10 days and not one person got on the Montgomery bus and amazingly, a lot of white people too

Bomb in church on Sunday (hoping to hurt or kill people)

According to MLK, one of the most vicious crimes that's happened in the Civil Rights Era

Once again, everyone knew who did it, but this time they did nothing

No one was arrested even till 1977

The bomb killed 4 girls under the age of 12 and injured 22 more

Edmund Pettis Bridge, Selma, AL

By 1965, the right to vote was something the South didn't like and the bridge was used to get to the polls by African Americans

Selma had a 35% black population

By '83 of that year, people started a confirmation to 400 unarmed black people

Black man was even shot in the gut and died

MLK and others planned a peaceful march and had to crossed this bridge

Bloody Sunday, March 7 on 1965

Armed troopers attacked peaceful demonstrators who were walking across the bridge in numbers. Started in the sidewalks, then moved to the street when there were no cars, but they couldn't see what was waiting for them till they reached the top of the bridge. They saw the police and upon seeing them, were terrified.

Asked one if they knew how to swim

They continued and then were beat and shot by the police

Major networks were there too, therefore leading to televised footage of this

The marchers were bloodied and were severely injured

Worked against the plan of George C. Wallace and the troopers

17 marchers were hospitalized

April 1968, Lorraine Hotel, Memphis, TN

One of MLK most impressive speech, the Temple of the Mountain, and he was in Memphis when he gave the speech

He concluded he knew he was going to die (many death threats and most were credible)

He knew his time was limited

Its the poor white people

Some of the why us and not you?

If you're poor, you're constantly attacked and made to feel less human. But it doesn't excuse shit bitch

Two of the worst schools in Boston because they were the poorest

Football season got canceled because parents were throwing rocks due to black students

Black and white students had to enter through different entrances

Restore Our Alienated Rights (ROAR), this didn't include black people

0 notes

Photo

The second time Amelia Boynton Robinson crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, she was holding hands with Barack Obama, the first Black president of the United States. She was 103. That’s in stark contrast to the way the world met Amelia. As one of the original architects of the Voting Rights movement, she headed up the march from Selma when state troopers descended on protesters on the bridge with tear gas and clubs. A photograph of Amelia brutally beaten and unconscious in the arms of a fellow protestor cemented the nation’s need for civil rights. We lost Amelia in August of 2015. She lived long enough to see the great strides America made toward integration and equality. But the work that Amelia and countless others have started is not yet finished. Everyday, we must continue the fight toward equality.

Amelia Boynton Robinson believed that progress was possible within her lifetime. Let knowledge of her life and bravery propel us to make our own great changes.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

John Lewis' death sparks support to rename Edmund Pettus Bridge https://www.cbsnews.com/news/john-lewis-death-sparks-surge-in-support-to-rename-edmund-pettus-bridge-the-site-of-bloody-sunday-in-his-honor/

You can sign the petition here!

0 notes

Text

"The Sacred Right To Vote": "WE HAVE COME TO REGISTER TO VOTE" - DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR, ADDRESS AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE SELMA TO MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA MARCH FOR VOTING RIGHTS

“The Sacred Right To Vote”: “WE HAVE COME TO REGISTER TO VOTE” – DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR, ADDRESS AT THE CONCLUSION OF THE SELMA TO MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA MARCH FOR VOTING RIGHTS

Source: Stanford University, The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute

Address at the Conclusion of the Selma to Montgomery March

Author: King, Martin Luther, Jr. Date: March 25, 1965

Location: Montgomery, Ala.

Genre: Speech

Topic: Birmingham, 1963

Montgomery Bus Boycott Nonviolence…

View On WordPress

#Alabama#Bloody Sunday#Dr. Martin Luther King#Edmund Pettis Bridge#Jim Crow#Right to vote#Selma#Voting Rights Act#white supremacy

0 notes

Photo

Though not a real quote, the sentence manages to convey the sentiment of this passage from a sermon given in Selma, Alabama the day after “Bloody Sunday” at the Edmund Pettis Bridge: “Deep down in our non-violent creed is the conviction there are some things so dear, some things so precious, some things so eternally true, that they’re worth dying for. And if a man happens to be 36 years old, as I happen to be, some great truth stands before the door of his life — some great opportunity to stand up for that which is right. A man might be afraid his home will get bombed, or he’s afraid that he will lose his job, or he’s afraid that he will get shot, or beat down by state troopers, and he may go on and live until he’s 80. He’s just as dead at 36 as he would be at 80. The cessation of breathing in his life is merely the belated announcement of an earlier death of the spirit. “A man dies when he refuses to stand up for that which is right. A man dies when he refuses to stand up for justice. A man dies when he refuses to take a stand for that which is true. “So we’re going to stand up amid horses. We’re going to stand up right here in Alabama, amid the billy-clubs. We’re going to stand up right here in Alabama amid police dogs, if they have them. We’re going to stand up amid tear gas! We’re going to stand up amid anything they can muster up, letting the world know that we are determined to be free!”

--Martin Luther King, Jr. March 8, 1965 in Selma, Alabama

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Narnia Week, Day 2

Prince Caspian

Prompt questions here!

Favorite character(s) from this book?

... Aslan.

But also, I do love Peter in this book, I think. I love when he shows up as High King and the way he kinda steps in and helps Caspian. I love his humility when he sees Aslan, greets him, and immediately confesses to having led everyone wrong the entire time.

I love Lucy, and how she is SO relatable in being scared to follow Aslan even if the others won’t, and scared to wake them up, and scared to lead them when they think she’s crazy.

If there is a screen adaptation of this book, what do you like most about said adaptation? Does it do the book justice? What would you change?

Oh goodness. Overall? I still feel like the movie managed to capture the atmosphere of Narnia. It still feels like Narnia. It feels a little darker and wilder than the Narnia we saw last time, and the Old Narnians in the woods is something I feel like they were spot-on with.

I DO have to say I love the scene with the bridge, when the music quiets down and Lucy steps out, and then Aslan steps out and roars. That moment is magical. Also the casting was perfect, again. Ben is a treasure (and I wish he’d have kept his accent!). Also tbh, the tree twisting open to reveal a door at the end is kinda cooler than the doorway in the book, ngl. The music? As good as the soundtrack for LWW. Epic. Beautiful.

But now for what I’d change. Ok, so I GET that they had to smoosh the timelines a bit to make this storyline fit the arc of a movie. But some of their other changes I felt were unwarranted. Angry!Peter, for one. In the books, Peter is mostly a humble king and leader, even if he goes wrong a few times. He mostly DOES trust Aslan--he at least doesn’t have this whole idea of “well if Aslan won’t come through for us I guess I’ll do it myself.” The scene with the gorge and Aslan leading all the Pevensies and the DLF down it at night is beautiful in the books. The scene where Aslan greets all of them is deeply moving, and I desperately wish we’d have gotten that scene. He commends Edmund, greets Peter’s confession with warmth and grace, comforts and strengthens and restores Susan, and even shows HUMOR when scaring the DLF into thinking he doesn’t like him. I really wish we’d have gotten that scene. AND the scene at the end where Aslan goes and frees a bunch of oppressed Narnians--kids in school, etc. It just feels like a party and celebration and I love it.

Another complaint: maybe this is me being petty, but in the scene where Lucy meets up with Aslan in the woods, Aslan says “if you were any braver, you’d be a lioness.” In the book, Lucy is scared and she buries her head in Aslan’s mane, and Aslan gives her strength. THEN he says “Now you are a lioness.”

See the difference? In the movie, Aslan is commending the bravery Lucy already has. In the book, Lucy is afraid, Aslan strengthens her, and MAKES her into a lioness. I feel like a huge message that was missing in the PC movie is that without Aslan, they’re all hopeless--he’s the one winning their victories and saving them (which parallels wonderfully with the Bible). And this was just one instance of that.

What about this book stands out most in your memory? Are there specific scenes, feelings, themes, or ideas that have stuck with you the most?

The scene where Lucy finds Aslan in the woods at night is one I have read over and over and over. One of my favorite scenes of all. These books allowed me to see God as warm and loving and affectionate, and this scene probably helped a lot with that.

Same with the scene at the end with Aslan freeing all the oppressed Narnians. The lady who wants to go with Aslan but has a class to teach? He frees her from that obligation and she can come. Same with the little girl. I can relate to that feeling so much because of my history with school and stress. With Aslan is freedom, in the Narnia books and in our world. <3

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw your post about Cardinal Beaufort but didn't have the chance to respond and now it's gone :( But anyway, he is very petty and his relationship with his nephews is fascinating too and I get to write (some) of that when I get around to writing the Eleanor Conham novel. :D

Oh, I thought it was tumblr being tumblr again and not sending you the notification! But yes, I think there are so many layers to that relationship, and of course, it shifts depending on the nephew. I’ve been fascinated for a time now about his, almost sort of partnership with Bedford?

Like on that infamous episode of the London Bridge barricade, Gloucester and (then bishop) Beaufort raising their own armies etc, and Bishop Beaufort goes on to write to Bedford for help — ‘my right noble and after one, levest lord, I recommend me unto you with all my harte’, appealing to Bedford’s desire of good governance and perhaps a shared opinion regarding his brother — ‘suche a brother you have here, God make him a good man’ — which denotes a certain type of closeness, at least, to be talking so openly about his brother (his political superior) with such frankness. The fact that Bedford personally gave him his cardinal hat, or that the cardinal sought to appease the Duke of Burgundy when Bedford and the duke were on bad terms, although politically motivated actions, I think they don’t exclude the fact that they had a partnership of sorts. I don’t know, I think it’s easier to think about the cardinal being close to his nephew Edmund Beaufort (who probably lived with him in his episcopal palace for a time), but there’s this relationship with Bedford and also the fact that apparently he didn’t resent Henry V for denying him his cardinalate at the end of his life but obstinately left Clarence and Gloucester out of his will. It’s so multifaceted, it’s fascinating. I’m sure it will be a very fun thing to write! ❤︎x

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

John Lewis crossing the Edmund Pettis bridge for the last time... 💔😢 #RestinPower #RegistertoVote https://www.instagram.com/p/CDHHnLEAtx8/?igshid=14ego9rfuo5s

4 notes

·

View notes

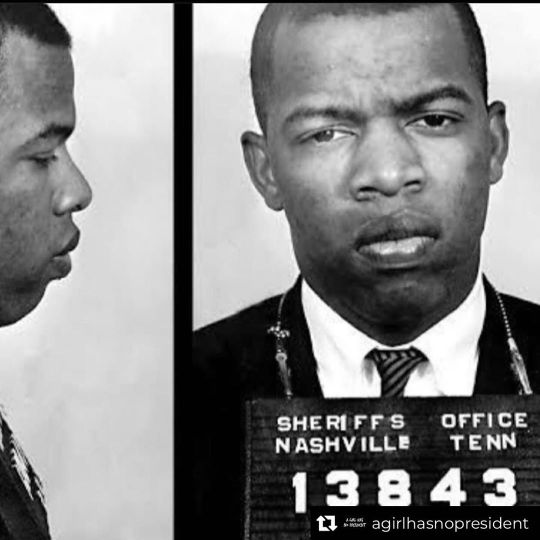

Photo

Repost from @agirlhasnopresident • “My parents told me in the very beginning as a young child when I raised the question about segregation and racial discrimination, they told me not to get in the way, not to get in trouble, not to make any noise.” John Lewis was 21 years old in 1961 when he became one of the original 13 Freedom Riders, who fought to integrate buses in the south. He was the first Freedom Rider to be assaulted. He was 23 years old when he was the 4th (and youngest) speaker at the March on Washington in 1963, for jobs and freedom. He was the only listed speaker who lived to see a black man inaugurated as President. He was 25 when he walked Across the Edmund Pettis bridge, in Selma Alabama in 1965, and received a skull fracture as payment for wanting voting rights for black folks. Imagine where we would be if these things had never happened. He got in the way. Get in the way. If you haven’t been to these places, I suggest that you go. And take your babies with you. #TeachThem #Courage #JohnLewis https://www.instagram.com/p/CCzNFcjllROcx2rd7P09aTfNK_XyDZLy0xciJ40/?igshid=1sq0k9zlyhfe9

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Aided by Father James Robinson, Mrs. Coretta Scott King, widow of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., center, and John Lewis of the Voter Education Project, a crowd estimated by police at 5,000, march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge from Selma, Ala., on March 8, 1975. :: [Scott Horton]

* * * * *

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

March 5, 2023 (Sunday)

Heather Cox Richardson

President Joe Biden spoke this afternoon in Selma, Alabama, to commemorate the 58th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, when law enforcement officers tried to beat into silence Black Americans marching for their right to have a say in the government under which they lived. Standing at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which had been named for a Confederate brigadier general, Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan, and U.S. senator who stood against Black rights, Biden said: “On this bridge, blood was given to help ‘redeem the soul of America.’”

The story of March 7, 1965, commemorated today in Selma, is the story of Americans determined to bring to life the principle articulated in the Declaration of Independence that a government’s claim to authority comes from the consent of the governed. It is also a story of how hard local authorities, entrenched in power and backed by angry white voters, worked to make the hurdles of that process insurmountable.

In the 1960s, despite the fact Black Americans outnumbered white Americans among the 29,500 people who lived in Selma, Alabama, the city’s voting rolls were 99% white. So, in 1963, local Black organizers launched a voter registration drive.

It was hard going. White Selma residents had no intention of permitting their Black neighbors to have a say in their government. Indeed, white southerners in general were taking a stand against the equal right of Black Americans to vote. During the 1964 Freedom Summer voter registration drive in neighboring Mississippi, Ku Klux Klan members worked with local law enforcement officers to murder three voting rights organizers and dispose of their bodies.

To try to hold back the white supremacists, Congress passed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, designed in part to make it possible for Black Americans to register to vote. In Selma, a judge stopped voter registration meetings by prohibiting public gatherings of more than two people.

To call attention to the crisis in her city, voting rights activist Amelia Boynton traveled to Birmingham to invite the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to the city. King had become a household name after the 1963 March on Washington where he delivered the “I Have a Dream” speech, and his presence would bring national attention to Selma’s struggle.

King and other prominent Black leaders arrived in January 1965, and for seven weeks, Black residents made a new push to register to vote. County Sheriff James Clark arrested almost 2,000 of them on a variety of charges, including contempt of court and parading without a permit. A federal court ordered Clark not to interfere with orderly registration, so he forced Black applicants to stand in line for hours before taking a “literacy” test. Not a single person passed.

Then, on February 18, white police officers, including local police, sheriff’s deputies, and Alabama state troopers, beat and shot an unarmed man, 26-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was marching for voting rights at a demonstration in his hometown of Marion, Alabama, about 25 miles northwest of Selma. Jackson had run into a restaurant for shelter along with his mother when the police started rioting, but they chased him and shot him in the restaurant’s kitchen.

Jackson died eight days later, on February 26. Black leaders in Selma decided to defuse the community’s anger by planning a long march���54 miles—from Selma to the state capitol at Montgomery to draw attention to the murder and voter suppression.

On March 7, 1965, the marchers set out. As they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, state troopers and other law enforcement officers met the unarmed marchers with billy clubs, bullwhips, and tear gas. They fractured the skull of young activist John Lewis and beat Amelia Boynton unconscious. A newspaper photograph of the 54-year-old Boynton, seemingly dead in the arms of another marcher, illustrated the depravity of those determined to stop Black voting.

Images of “Bloody Sunday” on the national news mesmerized the nation, and supporters began to converge on Selma. King, who had been in Atlanta when the marchers first set off, returned to the fray.

Two days later, the marchers set out again. Once again, the troopers and police met them at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, but this time, King led the marchers in prayer and then took them back to Selma. That night, a white mob beat to death a Unitarian Universalist minister, James Reeb, who had come from Massachusetts to join the marchers.

On March 15, President Lyndon B. Johnson addressed a nationally televised joint session of Congress to ask for the passage of a national voting rights act. “Their cause must be our cause too,” he said. “[A]ll of us…must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.” Two days later, he submitted to Congress proposed voting rights legislation.

The marchers were determined to complete their trip to Montgomery, and when Alabama’s governor, George Wallace, refused to protect them, President Johnson stepped in. When the marchers set off for a third time on March 21, 1,900 members of the nationalized Alabama National Guard, FBI agents, and federal marshals protected them. Covering about ten miles a day, they camped in the yards of well-wishers until they arrived at the Alabama state capitol on March 25. Their ranks had grown as they walked until they numbered about 25,000 people.

On the steps of the capitol, speaking under a Confederate flag, Dr. King said: “The end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience. And that will be a day not of the white man, not of the black man. That will be the day of man as man.”

That night, Viola Liuzzo, a 39-year-old mother of five who had arrived from Michigan to help after Bloody Sunday, was murdered by four Ku Klux Klan members who tailed her as she ferried demonstrators out of the city.

On August 6, Dr. King and Mrs. Boynton were guests of honor as President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Johnson recalled “the outrage of Selma” when he said, "This right to vote is the basic right without which all others are meaningless. It gives people, people as individuals, control over their own destinies."

The Voting Rights Act authorized federal supervision of voter registration in districts where African Americans were historically underrepresented. Johnson promised that the government would strike down “regulations, or laws, or tests to deny the right to vote.” He called the right to vote “the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice and destroying the terrible walls which imprison men because they are different from other men,” and pledged that “we will not delay, or we will not hesitate, or we will not turn aside until Americans of every race and color and origin in this country have the same right as all others to share in the process of democracy.”

But less than 50 years later, in 2013, the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act. The Shelby County v. Holder decision opened the door, once again, for voter suppression. Since then, states have made it harder to vote. In the wake of the 2020 election, in which voters handed control of the government to Democrats, Republican-dominated legislatures in at least 19 states passed 34 laws restricting access to voting. In July 2021, in the Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee decision, the Supreme Court ruled that election laws that disproportionately affected minority voters were not unconstitutional so long as they were not intended to be racially discriminatory.

When the Democrats took power in 2021, they vowed to strengthen voting rights. They immediately introduced the For the People Act, which expanded voting rights, limited the influence of money in politics, banned partisan gerrymandering, and created new ethics rules for federal officeholders. Republicans in the Senate blocked the measure with a filibuster. Democrats then introduced the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, which would have restored portions of the Voting Rights Act, and the Freedom to Vote Act, a lighter version of the For the People Act. Republicans blocked both of those acts, too.

And so, in 2023, the right to vote is increasingly precarious.

As Biden told marchers today, “The right to vote—the right to vote and to have your vote counted is the threshold of democracy and liberty. With it, anything is possible. Without it—without that right, nothing is possible. And this fundamental right remains under assault.”

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

#racism#Heather Cox Richardson#Letters From an American#history#Edmund Pettis Bridge#Selma Alabama#Voting Rights Act#Corrupt SCOTUS#voting rights#human rights#civil rights movement#Civil Rights

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

All our kids know the classic Civil Rights heroes who are in the curriculum - Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks. But their stories are too often simplified for easier consumption, eulogized as heroes who changed everything single-handedly. But perhaps the true heroism of leaders who fight for civil rights lies not only in what they do, but also in how they work with others, and inspire others to continue the battle. That is the kind of leader John Lewis was, and this book shows it so clearly. From renowned author Andrea Davis Pinkney comes this true story, told in powerful verse, of John Lewis and the boy, ten-year-old Tybre Faw, who he inspired. As a teen, Lewis himself was galvanized by the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, and led many student activism efforts. He coined the concept of "good trouble," working with others to use civil disobedience to create change. At 23, he led a historic protest across the Edmund Pettis Bridge to demonstrate for voting rights - where he, along with many other protestors, was permanently injured when state troopers attacked the peaceful marchers. He continued his justice work throughout his life, in Congress and out, fighting for Black and LGBTQ rights, and the rights of all marginalized by white supremacy. Every year, he marched across the Edmund Pettis Bridge again to remember Bloody Sunday and show the importance of continued work for justice. And just as Lewis looked up to MLK, Lewis in turn inspired young activists. Tybre Faw learned about Lewis during a research project in third grade (yay research!) and deeply admired his life and activist commitment. On one anniversary of Bloody Sunday, when Tybre traveled 7 hours with his grandmother to shake John Lewis' hand. John Lewis embraced him and invited him to walk by his side. Since then, the two became close friends, and Tybre kept marching - for Black rights, immigrant rights, school safety, and more. When Lewis died in 2020, Tybre spoke at his funeral, and exhorted his followers to follow John Lewis' example, and keep getting in good trouble. This book is a standout addition to our civil rights collection! https://www.instagram.com/p/CktmDciP3co/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

WIP. March 7, 1965, John Lewis at 25years old led 600 marchers across Edmund Pettis bridge in Selma Alabama and was attacked by state troopers. #injustice #march #marchforlife #marchforrights #discrimination #selma #selmaalabama #police #policebrutality #neverforget #artisticconjurations #artbyreed #edmunds #edmundpettusbridge #rightsforall #justice #johnlewis #protest https://www.instagram.com/p/CRO247eoOSB/?utm_medium=tumblr

#injustice#march#marchforlife#marchforrights#discrimination#selma#selmaalabama#police#policebrutality#neverforget#artisticconjurations#artbyreed#edmunds#edmundpettusbridge#rightsforall#justice#johnlewis#protest

0 notes

Link

September 25, 2017 -- Later this week, the March for Racial Justice will—I hope—choke the streets of our nation’s capital. If the current momentum against President Trump can be channeled to full potency, I believe it could be the most significant display of public fury on issues of race and inequality since Martin Luther King’s march on Washington in 1963.

Sadly, I won’t be there. I can’t be there.

I’ve attended a handful of rallies since Trump ascended in January. The largest was the Women’s’ March in D.C. the day after inauguration. As empowered as I felt that weekend, I knew I was there as a supporting actor: That day belonged to women. I had my own existential fears about the incoming administration, but I was there to support others—and did so consciously, so as not to coopt their stage.

The Racial Justice March, however, would be unreservedly a day for me to express my experience—mine and the millions of people of color like me. The time to wear out my shoes and lose my voice, to stand with the like-minded on a national and world stage and tell the current administration exactly why and how its values—to the extent that it even has any—are anathema to me.

It wouldn’t have been my first foray into demonstration. My Jewish progressive mother and my Black working-class father had me attending events before I could walk. My childhood was filled with Civil Rights-era hymns and folk songs, learned both at my Brooklyn daycare center and my Yiddish leftist summer camp. I spent many weekends on buses down to Washington attending peace and human rights rallies that I mostly didn’t understand.

As I was growing up, the names Amadou Diallou, Abner Louima and Sean Bell rang in my ears. The only time I remember seeing my father scared was when he spoke about the murder of Patrick Dorismond and how easily it could have happened to him. My father had a set number of emotions he would display regularly: Fear—until that moment—had not been one of them.

And then it happened to me. I and others in my generation witnessed the murders of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Eric Garner. I felt the same fear, the same terror—and the same need to make my voice heard.

But in a cruel twist of intersectional fate, the march has been scheduled to coincide with Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish Calendar—which means I and many of my racially conscious Jewish Comrades will be unable to take part.

***

In the summer of 2016, Trump was running for president—but at that point it seemed unlikely that he’d win. I was walking home after taking part in an anti-police brutality protest when I stumbled into my own terrifying interaction with the NYPD. As I neared my home, I saw three officers outside my door. I asked them if anything was wrong. One of the officers moved for his holster. I remember how his hand lingered there, neither removing his service weapon nor dropping to his side. I remember how unapologetic he was. Turns out they were standing there for no reason at all. But I remember fumbling with my keys as I struggled to get inside, and the feeling of relief when I was safely in my own apartment.

At that point, I was already pretty scared of Trump; his racist rhetoric a harbinger of dark times for Black Americans, but the incident flipped a switch. This was less than a month after the snuff videos of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling shocked the country. My fear and anger were refined by the terror of my own encounter. So the election felt like more than a mere quadrennial civic exercise. To me, it seemed like a referendum on the validity of the African-American existence. I was not only angry at Trump voters, but third-party voters, non-voters—anybody who didn’t utilize the full force of their electoral might to thwart him.

...The post-election protests enabled me to realign with my leftist roots. My mother’s father was a member of the Communist party. Through the various other leftist organizations, I became more committed to progressive causes. So when a racial justice group organizer sent me an invitation for the march in September, I clicked “attending” without even looking at the date: Whenever it was, I thought, I will be there.

Then I saw the date—maybe the one and only day of the year I COULDN’T be there.

The nature of the commemoration added a subtle irony in the otherwise divisive incident is that it stems from a point of cultural similarity. Jews have a long tradition of observing occasions of sadness well as occasions of joy. Half the dates on the Jewish Calendar are in some part anniversaries of sorrow. We commemorate the dead not on the day they were born, but on the day that they left us. The fast of Yom Kippur, one of pure spirituality, is equaled by only one other day, The Ninth of Av, when a litany of tragedies and massacres befell the Jewish people.

In response to the furor, March organizers released a moving and compassionate explanation and apology. In the statement, organizers noted that they chose to use the event to commemorate an atrocity that often eludes the collective American memory: September 30th is the anniversary of the Elaine Massacre, when as many as 237 blacks were killed. It makes sense that the march be should against the most conspicuous expressions of racism. They also noted “[that] mistake highlights the need for our communities to form stronger relationships.”

...It’s a trying moment for me. Confrontations on race, language and politics have often put me at odds with the Orthodox Jewish community. That lack of ideological solidarity was eventually filled by social justice organizing. So, being sidelined on the left at such a defining moment is gutting. The unfortunate scheduling of the Racial Justice March only exacerbated some of the anxiety I felt as a Jew on the Left. The oversight was not as aggressive as some harsh language BDS resolution or the confrontations that pro-Israel Jews have experienced at various pride marches, but it was another point in a growing constellation of Jewish discomfort in the progressive spectrum. Yes, many of us will be marching the next day, but separately and with diminished sense of solidarity with the movement at large.

Every black Jew will tell you that maintaining both identities is a constant battle; internally and externally. The Jewish community has an innate thread of solidarity built in it’s always there even when philosophical differences lead to animosity, the bonds of a commonality exist; sometimes adding fuel to the fire. The Jewish calendar is sprinkled with festivals and holidays that are observed collectively. To not adhere is to be excised from the people; one of the worst consequences in Jewish Law, even worse than death.

On the other hand solidarity is crucial to civil rights. If MLK had walked alone on the Edmund Pettis bridge, where would we be? Would his speech at the March on Washington have resonated if it was given to the empty reflecting pool? For the disenfranchised to challenge the powerful, they must access their own power. This power lies not in arms or in capital, but in numbers. To stand apart from comrades at such a moment is to withhold my individual power from the collective.

So, which does one choose?

Thankfully in the end, there’s a compromise; and perhaps, in a way, this is as it should be. Even though it wasn’t the organizer’s first choice, I’ve come to think that their choice of day is ultimately the correct one—a feeling I was able to realize because, their own expressions of hope for solidarity with and engagement with Jews and the Jewish experience felt real and forthcoming and honest, and devoid of the noxious if subtle dogwhistling and worse going on inside some pockets of the left these days. The white-knuckled indignation I had felt at the organizers exclusion intersectional oversight has been replaced by begrudging acceptance that there’s something beneficial to the FOMO I and other Jews will feel. So we’ll take to the streets the next day; not in Washington, at the seat of Trump’s empire, but in New York, on our shared home turf, doing what Jews have always been commanded to do and speaking truth to power.

Read Ben Faulding’s full piece at Tablet.

#Black Jews#Ben Faulding#jewish identity#African American Jews#March for Racial Justice#anti black racism#white supremacy

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rename the Edmund Pettis bridge. Name it the John Lewis Bridge.

10K notes

·

View notes