#East Asia’s Tarim Basin

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Who Were The Tarim Basin Mummies? Even Scientists Were Surprised. The Enigmatic, Extremely Well-preserved Mummies Still Defy Explanation—and Draw Controversy.

— By Erin Blakemore | September 15, 2023

Hundreds of bodies have been excavated from cemeteries like this one around the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang, a region of Western China. Known as the Tarim Basin mummies, these people lived some 4,000 years ago—and their ancient DNA has yielded surprising insights. Photograph By Wenying LI, XinJiang Institute of Cultural Relics And Archaeology

Though they died thousands of years ago, hundreds of bodies excavated in East Asia’s Tarim Basin look remarkably alive. They retain the hairstyles, clothing, and accoutrements of a long-past culture—one that once seemed to suggest they were migrant Indo-Europeans who settled in what is now China thousands of years ago.

But the mummies’ seemingly perfect state of preservation wasn’t their only surprise. When modern DNA research revealed the preserved bodies were people indigenous to the Tarim Basin—yet genetically distinct from other nearby populations—the Tarim Basin mummies became even more enigmatic. Today, researchers still ask questions about their cultural practices, their daily lives, and their role in the spread of modern humanity across the globe.

How Were The Tarim Basin Mummies Found?

Buried in a variety of cemeteries around the basin as long as 4,000 years ago, the naturally mummified corpses were first unearthed by European explorers in the early 20th century. Over time, more and more of the Tarim bodies were unearthed, along with their spectacular cultural relics. To date, hundreds have been found. The earliest of the mummies are about 2,100 years old, while more recent mummies have been dated to about 500 B.C.

One of the most famous mummies found in the Tarim Basin is the Princess of Xiaohe, also known as the Beauty of Xiaohe. Named for the cemetery where her body was found, she is remarkably well-preserved even down to her eyelashes. Photograph By Wenying LI, XinJiang Institute of Cultural Relics And Archaeology

Who Really Were The Tarim Basin Mummies?

At first, the mummies’ Western-like attire and European-like appearance prompted hypotheses that they were the remains of an Indo-European group of migrant people with roots in Europe, perhaps related to Bronze-Age herders from Siberia or farmers in what is now Iran.

They had blond, brown, and red hair, large noses, and wore bright, sometimes elaborate clothing fashioned from wool, furs, or cowhide. Some wore pointed, witch-like hats and some of the clothing was made of felted or woven cloth, suggesting ties to Western European culture.

Still others wore plaid reminiscent of the Celts—perhaps most notably one of the mummies known as Chärchän Man, who stood over six feet tall, had red hair and a full beard, and was buried over a thousand years ago in a tartan skirt.

Another of the most famous of the bodies is that of the so-called “Princess” or “Beauty” of Xiaohe, a 3,800-year-old woman with light hair, high cheekbones, and long, still-preserved eyelashes who seems to be smiling in death. Though she wore a large felt hat and fine clothing and even jewelry in death, it is unclear what position she may have occupied in her society.

But the 2021 study of 13 of the mummies’ ancient DNA led to the current consensus that they belonged to an isolated group that lived throughout the now desert-like region during the Bronze Age, adopting their neighbors’ farming practices but remaining distinct in culture and genetics.

Scientists concluded that the mummies were descendants of Ancient North Eurasians, a relatively small group of ancient hunter-gatherers who migrated to Central Asia from West Asia and who have genetic links to modern Europeans and Native Americans.

How Were They Mummified?

These bodies were not mummified intentionally as part of any burial ritual. Rather, the dry, salty environment of the Tarim Basin—which contains the Taklimakan Desert, one of the world’s largest—allowed the bodies to decay slowly, and sometimes minimally. The extreme winter cold of the area is also thought to have helped along their preservation.

How Were They Buried?

Many bodies were interred in “boat-shaped wooden coffins covered with cattle hides and marked by timber poles or oars,” according to researchers. The discovery of the herb ephedra in the burial sites suggests it had either a medical or religious significance—but what that religion might have been, or why some burials involve concentric rings of wooden stakes, is still unclear.

Mummified corpses were first unearthed in the Tarim Basin by European explorers in the early 20th century. Their Western-like appearance and clothing originally led researchers to believe these ancient people were migrants from Europe—but DNA later debunked that theory. Photograph By Wenying LI, XinJiang Institute of Cultural Relics And Archaeology

What Did They Eat?

Masks, twigs, possibly phallic objects, and animal bones found at the mummies’ cemeteries provide a tantalizing view of their daily lives and rituals. Though most questions about their culture remain unanswered, the burials did point to their diets and the fact that they were farmers. The mummies were interred with barley, millet, and wheat, even necklaces featuring the oldest cheese ever found. This indicates that they not only farmed, but raised ruminant animals.

What Were Their Daily Lives Like?

The Tarim Basin dwellers were genetically distinct. But their practices, from burial to cheesemaking, and their clothing, which reflects techniques and artistry practiced in far-off places at the time, seem to show they mixed with, and learned from, other cultures, adopting their practices over time and incorporating them into a distinct civilization.

Researchers now believe their daily lives involved everything from farming ruminant animals to metalworking and basketmaking—helped along by the fact that the now-desolate desert of the Tarim Basin region was once much greener and had abundant freshwater.

Researchers also believe that the Tarim Basin residents traded and interacted with other people in what would eventually become a critical corridor on the Silk Road, linking East and West in the arid desert.

But archaeologists still have much to learn about what daily life was like for these ancient humans, including who they traded with, what religious beliefs they adopted, and whether their society was socially stratified.

Most of the bodies were found buried in boat-shaped coffins like this one, with the site typically marked by oars. This coffin is covered with a cattle hide, suggesting that the Tarim Basin people raised cattle and other ruminant animals. Photograph By Wenying LI, XinJiang Institute of Cultural Relics And Archaeology

Why Are The Tarim Basin Mummies Controversial?

The amazingly preserved mummies have long fascinated archaeologists. But the Tarim Basin mummies have also become political flashpoints. The Tarim Basin is located in the modern-day Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, land claimed by China’s Uyghur minority. Uyghur nationalists claim the mummies are their forbears, but the Chinese government refutes this and has been reluctant to allow scientists to study the mummies or look at their ancient DNA.

In 2011, China withdrew a group of the mummies from a traveling exhibition, claiming they were too fragile to transport. Some research about the mummies’ DNA has been criticized as downplaying the region’s distinctness in support of China’s attempts to assimilate Uyghur people. Just as more remains to be learned about the enigmatic mummies, their future as political and national symbols remains disputed too.

#History & Culture#Tarim Basin | Mummies#Scientists#Enigmatic | Extremely Well-Preserved Mummies | Defy Explanation#Draw Controversy#Xinjiang | China 🇨🇳#East Asia’s Tarim Basin#Western China 🇨🇳#Buried | 4000-Year-Old#Naturally Mummified Corpses | 20th Century | European Explorers#Mummies | Western-Like Attire | European-Like Appearance#Bronze-Age Herders | Siberia Russia 🇷🇺 | Farners in Iran 🇮🇷#Western European Culture#Celts#Chärchän Man#Princess | Beauty | Xiaohe#Central Asia | West Asia#Modern Europeans | Native Americans#Boat-Shaped Wooden Coffins | Covered | Cattle Hides | Marked | Timber Poles or Oars#Barley | Millet | Wheat 🌾 | Necklaces | Oldest Cheese 🧀#Silk Road | Linked | East and West | Arid Desert 🌵#Tarim Basin | Modern-Day Xinjiang | Uyghur Autonomous Region

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Princess of Xiaohe (Chinese: 小河公主) or Little River Princess was found in 2003 at Xiaohe Cemetery in Lop Nur, Xinjiang. She is also known as M11 for the tomb she was found in. She was buried around 3,800 years ago. Furthermore, she was named the Princess of Xiaohe due to her state of preservation and beauty, not her social status; there is no reason to believe she was any more important than the other mummies buried in the complex.

The Princess has blonde hair and long eyelashes, with some facial features more similar to Indo-Europeans, such as high cheekbones and pale skin. She seems to be smiling slightly. She was 152 centimetres tall. Chunks of cheese were found on her neck and chest, possibly as food for the afterlife. Her body was not embalmed before death, but mummified naturally due to the climate and burial method.

“Despite being genetically isolated, the Bronze Age peoples of the Tarim Basin were remarkably culturally cosmopolitan – they built their cuisine around wheat and dairy from West Asia, millet from East Asia and medicinal plants like Ephedra from Central Asia,” said senior author Christina Warinner, an associate professor of anthropology at Harvard University.

The Tarim Basin mummies in what is now southern Xinjiang were once thought to be Indo-European-speaking migrants from the West. Some thought that their ancestors migrated from what became southern Siberia, northern Afghanistan or the Central Asian mountains.

“The identity of the earliest inhabitants of Xinjiang, in the heart of inner Asia, and the languages that they spoke have long been debated and remain contentious,” wrote the team of 34 researchers from China, Germany, South Korea and the United States in peer-reviewed journal Nature on Wednesday.

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

HONG KONG — When the 3,600-year-old coffin of a young woman was excavated in northwestern China two decades ago, archeologists discovered a mysterious substance laid out along her neck like a piece of jewelry.

It was made of cheese, and scientists now say it’s the oldest cheese ever found.

“Regular cheese is soft. This is not. It has now become really dry, dense and hard dust,” said Fu Qiaomei, a paleogeneticist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing and the co-author of a study published Tuesday in the journal Cell.

A DNA analysis of the cheese samples, she told NBC News in a phone interview Thursday, tells the story of how the Xiaohe people — from what’s now known as Xinjiang — lived and the mammals they interacted with. It also shows how animal husbandry evolved throughout East Asia.

The Bronze Age coffin was discovered during the excavation of the Xiaohe Cemetery in 2003.

Since the woman’s coffin was covered and buried in the dry climate of the Tarim Basin desert, Fu said, it was well preserved, as were her boots, hat and the cheese that laced her body.

Ancient burial practices often included items of significance to the person buried alongside them. The fact that those items included chunks of kefir cheese alongside the body showed that “cheese was important for their life,” she added.

A fondness for cheese dates back thousands of years.

Its production was depicted on wall murals in ancient Egyptian tombs in 2000 BC, and traces of the practice in Europe date back almost 7,000 years, but scientists say the Tarim Basin samples are the oldest samples of cheese actually found.

Fu and her team took samples from three tombs in the cemetery, and the team then processed the DNA to trace the evolution of the bacteria across thousands of years.

They identified the cheese as kefir cheese, which is made by fermenting milk using kefir grains. Fu said they also found evidence of goat and cow milk being used.

The journey of the cheese took them to tracing the journey of the kefir culture, which is used to make the final cheese.

The study also shows how Xiaohe people, who were known to be genetically lactose intolerant, consumed dairy before the era of pasteurization and refrigeration, as cheese production lowers lactose content.

While previous research has suggested kefir spread from the northern Caucasus in modern Russia to Europe and beyond, the study shows the spread also took another route toward inland Asia: from present-day Xinjiang via Tibet, giving crucial evidence of how the Bronze Age populations interacted.

The DNA analyzed by Fu’s team also suggested that the bacteria strains gained resistance to antibiotics as they became more prevalent throughout the years. “Today they’re actually very resistant to medicine,” Fu said.

But it also showed how the bacteria, which would have earlier triggered immune system responses in humans, also adapted. “They are also good for the immune system and for producing antibodies. We can see at some point it adapted to humans.”

The evolution of human activities spanning thousands of years also affected microbial evolution, the study found, citing the divergence of a bacterial subspecies that was found to have been facilitated by the spread of kefir across different populations.

Asked if the kefir cheese was still edible and if she would try it, Fu was less enthusiastic. “No way,” she said. _______________

Coward, eat the cheese

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tattooing in the Far East and Oceania

Since preserving skin takes mummification, without direct effort, a dry climate, whether hot or cold, is needed to create them, so we don't have a complete history of tattooing in many cultures, or even back as far in history as we have evidence of humans. But, there are locations that have preserved skin or customs for us to learn about ancient practices.

Source courtesy Victor Mair, Culture: Unknown, Location: Tarim Basin, China, Date: 1000-600 B.C.

One of those deserts is in China, the Taklamakan Desert, which shows that tattoos were used around 1200 BCE, but during the Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 BCE), tattoos were used to mark criminals. These mummies were discovered in the Tarim Basin (which contains the Taklamakan Desert) from what are thought to be the ancestors of Uyghur people today, looking more Caucasian than Asian, were decorated with several motifs, such as crescent moons, suns, and other intricate designs, which may show their primary god and indicate they were a shaman. This interpretation is based on the evidence from near-by cultures. They also tattooed their face at times, which indicated pride in and the importance of the tattoos.

By anonymus - Mann und Weib.III. page 458, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15174677

In Japan, men started wearing elaborate tattoos in the late 3rd century CE, though there is also evidence for tattooing going back to the Joumon (or paleolithic) period given that there are figurines with cord patterns on them. In the Yayoi period (300 BCE - 300 CE) tattoo designs on Chinese visitors in Kyushu were documented on, with speculation about them being spiritual or for status. In the 8th century CE "Records of Ancient Matters", tattooed people were considered outsiders, denying a history of tattooing in Japan. The Ainu people, the indigenous group of northern Japan, however, have a tradition of tattooing for decoration or status, or as protection against disease.

Te Ara The movement of peoples around the Pacific and from Asia into the Pacific over the last 6,000 years.

The Polynesian cultures of Oceania have a very long history of tattooing, developing over thousands of years and through the cultures that developed on the various islands they inhabited. The word 'tattoo' comes from the Tahitian islander's term 'tatatau' or 'tattau', as reported by James Cook's expedition in 1769.

By Louis John Steele - bwEy48meVL_AzQ at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21871113 and By Louis John Steele - bwEy48meVL_AzQ at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21871113

One of the most well known Polynesian cultures is the Māori of what is now New Zealand. Their tattoos, called 'tā moko' (the art of tattooing), are marks of high status and survived European attempts to eliminate them. Each moko is designed specifically for the person since it conveys much about who that person in, from their family to their accomplishments. On women, these tattoos are centered around the mouth and chin, while men often have tattoos around their whole faces and bodies. To receive a moku, generally certain milestones or accomplishments need to be reached and the recipient needs to have the right social status.

By Thomas Andrew (1855 - 1939) - National Library of New Zealand, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10113865 and By RunningToddler - Bits & Bytes, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3148860

Another well-known Polynesian culture with a rich tattoo history are the Samoa. In Samoa, men receive a 'pe'a' tatto, which covers their lower back and legs, and women receive a 'malu' which covers the legs from below the buttocks to below the knee. Malu tend to be more delicate and less covering than the pe'a, and are focused around a particular motif (called the malu) which is tattooed in the popliteal fossa (back of the knee), and has suggestions of shelter and protection. Sometimes, women are tattooed on their hands and lower abdomen as well. These tattoos are a sign of cultural pride, status, such that when a man completes his tattoo, he is called a saga'imitti and respected because he underwent the painful ordeal. A man without a tattoo is called telefua or telenao, meaning 'naked', and a man who hasn't completed the tattoo process because of the pain (or not being able to pay) is called pe'a mutu, a mark of shame. The tattooists (called a tufuga ta tatau) are revered as well. Modern Samoan tattoo artists continue to practice their art in the same way as they did prior to European contact, with serrated bone combs tied to tortoise shell fragments, tied to a short wooden handle and then tapped with a mallet. The ink is made from candlenut soot and stored in coconut shell cups. A length of tapa cloth (a barkcloth) is used to wipe blood from the skin and tools.

By Thomas Andrew (1855-1939) - http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/Search.aspx?page=8&imagesonly=true&term=Thomas+Andrew, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10113825

Previous post

Resources:

The Beauty of Loulan and the Tattooed Mummies of the Tarim Basin

Pacific voyaging and discovery

Tāmoko | Māori tattoos: history, practice, and meanings

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mummified heads from Xiaohe cemetery 2000 BCE

"Readers of Language Log will certainly be aware of Tocharian, but when I began my international research project on the Tarim Basin mummies in 1991, very few people — only a tiny handful of esoteric researchers — had ever heard of the Tocharians and their language since they went extinct more than a millennium ago, until fragmentary manuscripts were discovered in the early part of the 20th century and were deciphered by Sieg und Siegling (I always love the sound of their surnames linked together by "und"), two German Indologists / philologists — Emil Sieg (1866-1951) and Wilhelm Siegling (1880-1946), in the first decade of the last century.

It wasn't long after the decipherment of Tocharian by Sieg und Siegling that historical linguists began to realize the monumental importance of this hitherto completely unknown language. First of all, it is the second oldest — after Hittite — Indo-European language to branch off from PIE. Second, even though its historical seat was on the back doorstep of Sinitic and it loaned many significant words (e.g., "honey", "lion") to the latter, it is a centum (Hellenic, Celtic, Italic and Germanic) language lying to the east of the satem (Indo-Iranian and Balto-Slavic) IE languages. (PROVISO: some sophists will undoubtedly argue that the centum-satem split in Indo-European is meaningless; it has happened before on Language Log and elsewhere, but I think it does matter for the history of IE languages and the people who spoke them.) Third, Tocharian has grammatical features that resemble Italic, Celtic, and Germanic (i.e., northwest European languages) more than they do the other branches of IE. (STIPULATION: certain casuists will surely argue that such differences are meaningless, but I believe they are crucial for comprehending the nature of the spread of IE in time and space.) Etc.

Because their physical, textual, and cultural remains were indisputably found in the Tarim Basin, the Tocharians naturally became a primary focus of my investigations in Eastern Central Asia during the more than two decades from the nineties through 2012."

-Victor Mair, Language Log: The sound and sense of Tocharian. University of Pennsylvania.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

Witches all over the world respect what Beltane means to us. Even with our boldest enemies in foreign parts, there has always been a cease fire during the holiday. Beltane is sacred.

Sarah Alder, 1x4

I wonder, is there reciprocation for other witch cultures? Does the US military respect what non-pagan witch holidays mean to other witch militaries? Is there a ceasefire during days sacred to other nations?

And how is the sacred-ness of holidays established? Can new holidays be created with sufficient community participation and repetition? Is this an aspect of Hague Canon regulations?

And what of nations where the witches' base religion was never marginalized and is still the country and peoples' mainstream, like in parts of Asia? Which is erased for the Asians in the US military, on top of the former slaves having never reconnected with their African heritage. How do those soldiers feel when deployed and perhaps have to observe ceasefires for enemies sharing their ethnicity having their own holidays?

Not to mention where Islam falls here. In the Middle East, where you have Muslim Hegemony, is pre-Islam Persian culture the equivalent of European pagan witch practice? And if we reaaaaally want to get real thorny, how does Judaism play into this world?

Does the US witch military still respect Freedom of Religion (and if the Independence War happened 50 years earlier so James Madison wasn't a Founding Father, does this US even still have a Bill of Rights), and so allow witches to practice traditions from outside of European pagan culture?

It's still eyebrow-raising that the Marshal set them up to celebrate Yule, and obviously not as a one-off thing, but as something he himself observes, with the same for Adil. Am I to really believe that Native Americans/Tarim Basin didn't have their own winter solstice practice, or are the Marshal's actions proof that cultural authenticity has no bearing on the energies that can be drawn from a holiday? That is, is doing a cultural-mishmash swirl of traditions into a more inclusive sythesis actually more effective, as it increases the community-participation multiplier? Is that "COEXIST" sticker witch military goals?

#motherland fort salem#category: tv#do japan's witches get a boost by proxy out of anime expo#what holidays did the Mexicans of the US-Mexican War celebrate#indigenous or spanish#why can't a coven genuinely derive power from christian practice if they sincerely believe it; christo-without-the-pagan#call it systematized prophetic miracle

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Greco-Buddhist Art: A Fusion of Eastern and Hellenistic Traditions

BY DIMOSTHENIS VASILOUDIS

Greco-Buddhist art stands as a remarkable testament to the intermingling of classical Greek culture with Buddhism, marking a significant chapter in the annals of art history. This unique artistic tradition, known as Greco-Buddhism, emerged from a fascinating blend of Eastern and Western cultural elements, flourishing over a span of nearly a millennium. From the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE to the Islamic conquests of the 7th century CE, Greco-Buddhist art developed across Central Asia, showcasing the depth and breadth of cultural syncretism.

The inception of Greco-Buddhist art can be traced back to the Hellenistic Greco-Bactrian kingdom, established in what is now Afghanistan between 250 BC and 130 BC. The establishment of the Indo-Greek kingdom from 180 BC to 10 BC further accelerated the spread of Hellenistic culture into the Indian subcontinent during this time period. It was in the Gandhara region of today's northern Pakistan that the melding of Greek and Buddhist cultures reached its zenith, under the auspices of the Indo-Greeks and later the Kushans. Gandhara became the cradle of Greco-Buddhist art, from which its influence radiated into India, impacting the art of Mathura and subsequently the Hindu art of the Gupta empire. This latter influence extended throughout Southeast Asia, while Greco-Buddhist art also made its way northward, leaving its mark on the Tarim Basin and ultimately influencing the arts of China, Korea, and Japan.

Characterized by the strong idealistic realism and sensuous depiction inherent to Hellenistic art, Greco-Buddhist art is renowned for introducing the first human representations of the Buddha. This pivotal development not only helped define the artistic and sculptural canon of Buddhist art across Asia but also served as a bridge between the aesthetic ideals of the East and the West. The portrayal of the Buddha in human form, imbued with the grace and precision of Greek sculpture, lent a new dimension to Buddhist iconography, enriching its symbolic and emotional depth. ...

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Europe:

Iberia

Pamplona and the Kingdom of Navarre: Trifecta of Strife and Unity

Toledo and Medieval Iberia: Abode of Three Faiths

Santiago de Compostela and the Kingdom of Galicia: Jerusalem of Iberia

Oviedo and the Kingdom of Asturias, Raging Embers of Christendom

Leon:

Zaragoza:

Lisbon:

Granada: Final Bastion of the Moors

Cordoba and the Umayyad Dynasty: Throne of the Rightful Caliph

Seville and Medieval Iberia: Pearl of Andalusia

Celtic Isles

London and the

Scone and Medieval Scotland, Throne of Ascension and Sovereignty

Scandinavia

Lund and Medieval Denmark: Heart of Scandinavian Christendom

Roskilde and Medieval Denmark: Throne of Sacred Springs

Hedeby and Viking Age Denmark: Hearth at the World’s Edge

Uppakra and Viking Age Sweden: Grand Norse Metropolis

Gamla Uppsala and Viking Age Sweden: Hall of the Aesir

Nidaros (Trondheim) and Medieval Norway: Royal Harbor of the North

Sigtuna

Variscia

Paris:

Cologne:

Luxembourg:

Lubeck:

Regensburg

Aachen & Frankfurt = Imperial elections and coronations.

Nuremberg & Regensburg = Political centers and imperial diets.

Cologne & Lübeck = Commercial powerhouses.

Prague & Vienna = Royal capitals at different times.

Augsburg = Banking dominance.

Visegrad

Krakow and the Kingdom of Poland, Majesty Ascent in the Plains

Esztergom and the Kingdom of Hungary, Equestrian Valor imbued with Catholic Glory

Prague

Sarmatia

Kernave and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: Pagan Might of the Balts

Vilnius and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: Mountain of the Iron Wolf

Kiev:

Novgorod: Cradle of all the Russ

Trebizond:

Principality of Chernigov

Principality of Pereyaslavl

Vladimir-Suzdal

Principality of Volhynia

Principality of Galicia

Principality of Polotsk

Principality of Smolensk

Principality of Ryazan

Balkania

Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire: Crown of the Ecumene

Thessaloniki

Pliska

Preslav: Cradle of Orthodox Slavdom

Turnovo: The Third Rome

Italia

Palermo:

Venice: Serenity afloat in Opulence

Genoa:

Ravenna

Pavia:

Caucuses

Ani: Where the Angels Nest

Tbilisi:

West Asia

Arabian Peninsula:

Medina and the Rashidun Caliphate, Bastion of the Holy Prophet

Mecca

Levant:

Mesopotamia:

Baghdad and the Abbasid Caliphate, Beating Heart of the Ummah

Anatolia:

Iranian Plateau:

Ghazni

Central Asia

Orkhon valley

Otuken: Where all power and authority derives

Karakorum

Test

Merv and the Medieval MiddleEast, Rendezvous of Great and Small

Tarim Basin:

Loulan

Qocho

Beshbalik

South Asia

Test

East Asia

Tibetan Plateau:

Lhasa and the Tibetan Empire, Heart of the Supine Demoness

Korean Peninsula:

Gyeongju

Kaesong

Manchuria:

Japanese Archipelago:

Kyoto and Medieval Japan, Tranquility adorned in Flora

Kamakura and Medieval Japan, Will of the Shogun

Coastal River Basin:

Chang'an and the Tang Dynasty, City of One Hundred and One Cities

Southeast Asia

Test

Thang Long and the Dai Viet, Where the Dragon Rises

Angkor Wat and the Khmer Empire, The Divine Temple City

Vijaya

Muang Sua

Oceania

Micronesia

Nan Madol and the Saudeleur dynasty, Reef of Heaven

Polynesia

Mua

Australasia

Melanesia

Africa

Maghreb:

Kairouan

Fez

Tunis

Tlemcen: Nexus of the Sahara and Mediterranean

Sijilmasa: Fortune at the desert’s frontier

Nekor: Synthesis of Arab-Berber Unity

Nile Valley:

Seats of Power: Soba and the Kingdom of Alodia, Verdant Grail of Treasures

Horn of Africa:

Seats of Power: Cairo and the Fatimid Caliphate, Babylon on the Nile

Axum:

Sahel:

Guinea Rainforest:

Ile Ife and the Medieval Yoruba State, Origin of Mankind and All Creation

Benin:

Congo River Basin:

Swahili Coast:

Kilwa

Mogadishu

North America

Northeast Woodlands:

Cahokia and the Mississippian Culture, Spiritual Nucleus of the Great River

Tenochtitlan and the Aztec Empire, Prickled Crown Sprout from Blood

Tikal

South America

Andes mountains

Chan Chan and the Kingdom of Chimor, Solar Glory of the Moche Valley

Cusco

0 notes

Photo

One of the first representations of the Buddha, 1st-2nd century CE, Gandhara, Pakistan: Standing Buddha (Tokyo National Museum).

“Under the Indo-Greeks and then the Kushans, the interaction of Greek and Buddhist culture flourished in the area of Gandhara, in today’s northern Pakistan, before spreading further into India, influencing the art of Mathura, and then the Hindu art of the Gupta empire, which was to extend to the rest of South-East Asia. The influence of Greco-Buddhist art also spread northward towards Central Asia, strongly affecting the art of the Tarim Basin, and ultimately the arts of China, Korea, and Japan.”

#Buddha#buddhism#Occult#white stone#white lotus#hinduism#gandhara#egyptian mysticism#babylonian esotericism#Christos#Chrisos

63 notes

·

View notes

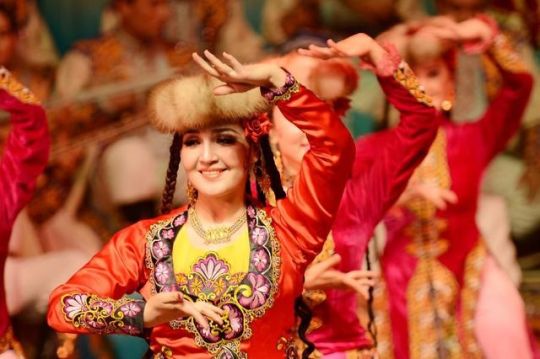

Photo

Uyghur dancers

The Uyghurs (/ˈwiːɡʊərz/, /uːiˈɡʊərz/; Uyghur: ئۇيغۇرلار, уйғурлар, IPA: [ujɣurˈlɑr]; Chinese: 維吾爾; pinyin: Wéiwú'ěr, [wěiǔàɚ]), alternately Uygurs, Uighurs or Uigurs, are a minority Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central and East Asia.

The Uyghurs have traditionally inhabited a series of oases scattered across the Taklamakan Desert comprising the Tarim Basin, a territory which has historically been controlled by many civilizations including China, the Mongols, the Tibetans and the Turkic world. The Uyghurs started to become Islamised in the tenth century and became largely Muslim by the 16th century, and Islam has since played an important role in Uyghur culture and identity.

Sanam is a popular folk dance among the Uyghur people. It is commonly danced by people at weddings, festive occasions, and parties. The dance may be performed with singing and musical accompaniment. Sama is a form of group dance for Newruz (New Year) and other festivals. Other dances include the Dolan dances, Shadiyane, and Nazirkom. Some dances may be alternate between singing and dancing, and Uyghur hand-drums called dap are commonly used as accompaniment for Uyghur dances.

651 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rock Art in the Upper ~Indus Region

Harald Hauptmann Rock Art in the Upper ~Indus Region

The majestic peaks of the Himalayas with their I4 eight-thousanders towering above the scenery, separate the Tibetan Plateau and the South Asian subcontinent on a length of 2,500 km. They do not. though. form an impassable barrier to man, as evident from its western part comprising the Hindu Kush, the Western Himalayas. and the Karakoram in the north of Pakistan. From the Tarim Basin, several paths lead over passes more than 4,000 metres high over the glaciers of the mountain chains of the The Karakoram down to the deeply cut canyons of the Indus river and its tributaries. This network of routes that connects the northern steppe regions with Kashmir and the Indo-Pakistani lowlands has been frequented by hunters and nomads since the end of the Ice Age as well as during historical times by merchants with their caravans, by Buddhist pilgrims, Chinese emissaries. and foreign conquerors. The high mountain range that today encompasses the Northern Areas of Pakistan formed, on the one hand, the shortest connection to the trading posts in the Tarim Basin for Indian caravans, but on the other hand, it was also, in the opposite direction, at least temporarily the gate to India for Sogdian merchants from Samarkand. A southern section of the legendary Silk Route led through the Indus Valley. It consisted of a network of trading routes that started in the ancient Chinese imperial cib of Changan and led to the Mediterranean Sea via the oasis cities in the Tarim Basin, such as Khotan, Yarkand and Kashgar as well as Turfan and Kucha. The first description of the passages leading from the Tarim Basin via the Hindu Kush and Karakoram to the kingdoms ofJibin (Chi-pin) and Nandou - kingdoms that are located in the regions around Kapisa-Peshawar and Gilgit - is provided by the chronicle Han Shu (25-221 B.c.E.) from the time of the Han dynasty. The difficult route continues until it reaches the "Hanging Passages", spanning deep chasms, which are described as life-threatening challenges for man and beast. This toponym might either refer to the paths running in vertiginous heights along the scarps above the Hunza and the Indus rivers or, more probable, to the shaky rope bridges stretching over mountain torrents. The adventurous itineraries of Chinese pilgrims vividly narrate the arduous journeys across the snowcovered peaks of the "Onion Mountains" down to the Indus Valley. The earliest among these pilgrims, according to the tradition, was the monk Faxian (317-~zo), who started his 15-years-long pilgrimage in the imperial city of Changan. After having scaled the Karakoram Faxian reached the kingdom Jiecha (Kie-cha), probably modern Baltistan, and the small kingdom of To-lieh or ~uoliin the year 400. This place was of supraregional religious importance, as its sanctuary was most prominent for a gilded wooden statue of Maitreya, the future Buddha, which was over 20 metres high. Only afterwards, Faxian crossed the "Route of the Hanging Passages", i.e. the Indus river, to arrive at his destination, the kingdom of UddiyHna, in Swat. In the report of the most famous pilgrim, Xuanzang (629-645), a Chinese Marco Polo, who had also chosen the southern route over the "Onion Mountains" to Gandhara. the miraculous Maitreya statue and an adjunct monastery is described again at a place that he calls Ta-li-lo. This location is probably to be identified with a religious centre such as the one in the Chilas Basin. Apart from these reports and some later chronicles, there exist no other historical sources on this region. Yet, there is another group of monuments giving a deeper insight into the history of this high mountain region: A collection of rock art images ~~niiqn ~the~ire diversity and ex Fig. 2 Hodur-West. Stupa-Buddha group traordinary in their quantity. Carved into the rock faces and boulders of the Indus gorge, reaching from Indus-Kohistan to Baltistan, and, even beyond, to Ladakh and Tibet, expands one of the worldwide largest and most impressive rock art provinces. These monuments can also be found on the important pass routes and subsidiary valleys of the Indus river be it along with the Gilgit, at Yasin, in Hunza up to the Kilik pass. along the Shigar or the Shyok in Baltistan. They concentrate along the Fully developed routes to both sides of the Indus river. having their richest clusters within a stretch of more than 100 kilometres between Shatial in Indus-Kohistan and the bridge of Raikot. In these rock art galleries, which are centred around Chilas and Thalpan in the district of Diamer at the foot of the 8,125 meter high Nanga Parbat, over 50,000 rock drawings and more than 5,000 inscriptions represent a period lasting from the late Stone Age to the Islamisation of the mountain region that took place in the l6th century. The remarkable diversity of these engravings, also known as the "guest book of the Silk Route", mirrors the history, the cultural and social traditions and the religious ideas of local as well as immigrated peoples. The existence of this rock art as well as that of the two monumental Buddha reliefs of Kargah near Gilgit (fig. 7) and Manthal near Skardu in Baltistan (fig. 8) has already been known since the 19'~c' century. But only after the completion of the 751 km long Karakorarn Highway - the direct connection between China and Pakistan - Karl Jettmar. Heidelberg, and Ahmad Hasan Dani, Islamabad, could commence systematic research of the rock art province. The work started as a joint German-Pakistani project in 1980 and in 1984 the project was taken over by the Heidelberg Academy of the Sciences and has continued with the approval of the Pakistani Department of Archaeology and Museums in Islamabad to date.* With the onset of the ~olocene(9,500-6,200 B.C.E.),the milder climate in this region went along with heavier precipitation that also favoured a lush vegetation in the valleys and thus permitted the expansion of diverse fauna. Tllese propitious environmental conditions. starting with the melting of the large glacersa, ttracted groups of hunters who created the earliest rock images ofwild animals: depictions of ibex, markhor, and bharal (~imalayanb lue sheep), but also hunting scenes that occasionally even feature depictions of humans (line drawings 1.1-2). The artist's symbolic presence seems to be expressed by representations of hand and foot prints. The pictures of animals. usually engraved in silhouettes and showing a subnaturalistic style, find their counterparts in the rock art provinces of Western Asia and Siberia, ranging from the late Stone Age to Neolithic times. Impressive images of large, naked figures of men can be ascribed to the Bronze Age, the late 3d millennium B.C.E. Depicted in frontal view, with arms outstretched (line drawing 1,3), these "giants", found as single figures or in pairs, are attested in more than 60 examples from prominent places in the lndus Valley to Ladakh and might represent images of ghosts, demons, or local deities. Alternatively they might just depict shamans. In isolated cases the faceless giants are connected with images of masks (line drawing 1,4), that, if compared with the Siberian Okunev culture, could be explained as relating to shamanistic actions. We can only assign some rare rock art examples of wild animals or hunting scenes, and some depictions of chariots, to the 2"hillennium B.C.E. The earliest megalithic round tombs in lshkoman and Yasin can be ascribed to this era as well. With the beginning of the first millennium B.C.E.. a new population appears in the Upper lndus region, which can be traced back to invasions of Scytho-Sakian tribes. These steppe nomads that entered from Central Asia and are known as Saka from the inscriptions of the Persian Great King Darius 1 (522-485 B.c.E.) contr~bute numerous pictures of ibexes. deer, and predators featuring the Eurasian animal style (line drawings 15-7). They correspond to animal bronzes discovered in ~cythimku rgans from Kazakhstan and Siberia. With the eastern expansion of the ~chaernenid-Persian kingdom in the 61h century B.C.E. and the establishL~ neD rawrng 1 1 Dadam Das, 2 Barlo Das, 3 Thor.4 Z~yarat5, Kalat Doduk,Bo 6Turr1l Nala. 7 Dong Nala Llne Drawlng 2 1-3 Thalpan.4-5 Chllas 11.6 Barlo Das, 7Thalpan.B Shat~al ment of the Indian provinces of Gandhara and Hindu5 (Sind), also Iranian influence reaches the Upper lndus Valley. This is reflected in perfectly rendered images of stylized horses, mythical creatures in the characteristic bent-arm, bent-leg posture that indicates flying, and particularly, in warrior figures dressed in Western Iranian costumes (line drawings 2,l-3, fig. 1). Under the reign of the Kushan dynasty (1" century C.E.). Buddhism started to spread as a new belief system in the Upper lndus region. With the beginning of the earlier Buddhist era, lasting from the 1'' to the 3rd century, the region enters the stage of history, as engravings of stupas worshipped by pilgrims (line drawings 2,4-5), scenes abundant with figures and enthroned rulers (line drawing 2.6), and in particular, the first inscriptions in Kharosthi show. In the area concerned, the Buddhism reached its peak between the 51h and 8'l' centuries. Small principalities were founded in the high mountain areas, such as the powerful Great Palur of the Palola %hi dynasty in the east (called Bolor in Tibetan sources), with its centre in Baltistan as well as Little Palur (Tibetan Bruia) on the high plateau ofGilgit with Yasin that borders in the west. Starting from the 7'l' century, those principalities fell under the alternating rule of twogreat powers: the Chinese rang dynasty and the Tibetan kingdom. The third political power were the Daradas or Dards living in the southern part of the Upper lndus Valley. The kingdomfs centre was located in the Nilum-Kishaganga area and from its outpost chilas, situated at one of the main crossings of the lndus (possibly the seat of a regional ruler), it controlled the route across the Babusar pass leading to Kashmir and Taxila, an old centre of the Gandharan kingdom, The imagery is dominated by numerous remarkable depictions of ,t,pas and images of the Buddha (fig. 4) that were engraved on both sides of the lndus river along the developed traffic routes secured by sentry posts and fortresses, at places of smaller sanctuaries, at river crossings. and at central locations such as Shatial. Thor, Hodur and Chilas-~hal~an, and Shing Nala. From the numerous religious buildings, particularly the ~tupaso, nly one monument has been preserved in an aln~ostc omplete state, the "Minar of the Taj Moghal" ofJutial above Gilgit. Very sporadi-, rui ns of these monuments can be observed in the Gilgit valley, in Baltistan in the Buddhist hill settlement of Shigar, or at Surmo in the shyok valley. Due to their high artistic quality and vibrancy, several scenic depictions, showing Jritaka scenes, that is episodes narrating previous existences of the Buddha, are outstanding among the rock art. Three of them. the Vyiighri or Tiger Jdtaka (line drawing 3.1), the &ipaticaka litaka or Jitaka of the Greatest Evils (line drawing 3. 2), and the Sibi jdtoko (line drawing 3,3), which adorn rocks at Chilas and Thalpan, were apparently created by one and the same artist and can be dated to the 6Ih century. An older depiction of the SibiJdtaka in Shatial is comparatively crude and compared to theJdtakos of Chilas-Thalpan, shows more Gandharan influence. (fig. 3). The magnificent composition consisting of two pagoda-like stupas hints at the close connections between the Upper lndus region and the Buddhist world laying beyond the "snowy mountains", namely Kashmir and Gandhara. The temptation of the Buddha by the beautihl daughters of the demon king MHra, a popular motif in Gandharan art, is depicted on a rock in Thalpan (line drawing 3.4). With the gesture of touching the earth with his right hand (bhirnispariarnudri). the earth opens, the earth goddess testi- Fig 3 Shatlal $~bJi atako,Stupas and lnscrlprtons in Kharosthi,Brahm~.andS ogd~an Fig. 4 Thalpan. Sitting Bllddha Fig. 5 Chilas III.Late Buddhist stupa worshipping scene and warriors with battleaxes F1g.6 Chilar X.Post-Buddhist battle are symbols 356 Fig 7 Standlng Buddha In the Kargah Valley near Gllg~t Fig.8 Buddha rock of Manthal near Skardu In Balt~stan fies to the ~uddha'sv ictory over MLra (rndravgaya), and the temptresses away quickly. He overcame this obstacle, and was subsequently enlighted under the Bodhi tree near Urubilva, where Gautama became the Buddha in a night of the full moon of the year 528 B.C.E. The first sermon he gave as the Buddha in the Deer Park of Sarnath near varanasi (Benares) is one of the most important events of the Buddha legend. ~t is at Thalpan in an impressive engraving (line drawing 3,5). This scene, very popular in Buddhist art, shows the Buddha in the company of his first five disciples, who were companions of SiddhHrtha during his phase of asceticism. The deer park is represented by two gazelles at the bottom, and the wheel symbolizes the act of teaching. Among the most beautiful images at Thalpan is the enthroned Buddha with his companion ~odhisattvaV ajrapPni portrayed in the background (line drawing 3.6). Due to its highly artistic execution and its distinctive importance for Buddhist imagery, an image found in Hodur-West has to be put in line with the most impressive examples of this art genre represented along the Upper lndus (fig. 2). It shows two Buddhas both seated on a single pedestal with a stupa between them. Apparently, this depiction hints at chapter 11 of the famous Lotos Sitra; one figure represents Sakyamuni, the historical Buddha, the other Prabhijtaratna, a Buddha of the past. The motif of the two sitting Buddhas with Prabhijtaratna's "Stupaof the seven precious materials" is very popular in the Buddhist art of Central Asia and China, as its numerous examples in paintings in the cave temples of Dunhuang, Lung Men, and Yungang as well as on relief steles show. The historical background of the Buddhist era in this region is particularly apparent in inscriptions. In the earlier phase, they are written in Kharosthi, whereas in the later phase of the 3rd to ath century, they use, in large numbers, the BrPhmTscript (cf. Falk, p. 14). The inscriptions are often added to images and render personal names and consecration formulas. Over 700 Sogdian, but also Bactrian, Parthian, and Middle Persian inscriptions that predominantly concentrate at Shatial, which is now interpreted as a former market place, attest the presence of Parthian and particularly Sogdian merchants from Samarkand. We can trace drawings of Iranian fire altars (line drawing 2.8), tamgas interpreted as heraldic family signs or emblems of cities such as Samarkand, and even Nestorian crosses. These images not only mirror the special importance of the Sogdians as merchants on the Silk Route, but also as mediators between the great religions such as Buddhism. Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism. Among the most beautiful creations are the saddled but riderless horses, that are, in Central Asian fashion, depicted in the pace gait (line drawing 2.7). Hephthalithic, i.e. Hunnic, as well as Turkish names appear in the inscriptions, too. Thirteen Chinese inscriptions, probably applied by merchants or pilgrims, and even one composed in Hebrew testify to the ethnic diversity of the region. A Chinese graffito on the rock formation of Haldeikish in the Hunza valley, through which the path up to the important pass leading to Kashgar in Xinjiang runs, mentions even an envoy of the dynasty of the "Great Wei". This site represents the most important epigraphic monument so far discovered in the The Karakorum, with 131 inscriptions in Kharosthi, Brahmi. Sogdian. Chinese, and Tibetan. From the 4th century onwards. anti-Buddhist influences appear on the scene, which indicates the arrival of foreign horse-riding peoples from the surrounding high mountain ranges of the Indus Valley. This new ethnic element is represented by crude depictions of battle axes, round disks which could be understood as reminiscent of sun symbols, and pictures of riders and warriors (figs. 5 and 6). Images of attacking war axe people evidently besieging Buddhists practically seem to defend stupas inform about the political and religious changes taking place in the area. In the northern regions, for instance, Gilgit and Baltistan. Buddhist traditions seem to have kept flourishing. though. The approximately three-metre high relief of a standing Buddha at Naupur in the Kargah Valley near Gilgit depicts him with the right arm held aloft in the gesture of fearlessness and indicates growing influence of Tibetan style in the century as does the relief on a six-metre-high rock in Manthal near Skardu in Baltistan (fig. 8). b here, together with 20 smaller Buddhas the meditating Buddha is seated in a Mandala-shaped assembly. This exceptional composition is flanked by two standing ~odhisattvasP; a dmapani with the lotus to the left, Maitreya to the right. Below, a ptimaghaka, the Vase of Plenty. is depicted (fig. 8). The only large-sized rock painting of ~haghdon ear Skardu. showing a magnificent stupa worshipping scene with the Raja of Shigar, attests to the final significant period of prosperity of Buddhism during the 12th century. Islamisation started from Kashmir in the 16th century and has its most impressive monuments in the first characteristic mosques with rich wood carving decoration in Khaplu. Shigar, and Skardu in Baltistan.

#gandahar#silkroad#silk route#gilgitbaltistan#gilgitbaltistan❤️#river_indus#rockart#mighty karakoram#himalayas#hindu kush#history

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Religion Through the Silk Road

by Hriday

The silk road has acted as a steering stick for a significant amount of culture, ideas, goods, technology, and philosophies to mix in with the fluid of human civilizations. Some of the most influential ideas that travelled through the silk road was religion and how present-day India received and distributed some of these ideas.

First, we can look at Islam as said in the book Exploration by Land: The Silk and Spice Routes by Paul Strathern in page 32 “Islam was founded in Arabia by the Prophet Muhammad in 622 CE. following his flight from the city of Mecca to Medina. It was the last of the world religions to pass along the Silk Route”. The religion is still one of the most influential religions along the silk route today. The present-day India was introduced to Islam quite early on mostly through the silk route and later through the ocean. People from India used to embark on the holy journey, hajj ither through the silk route or via the ocean. The oceans were obviously more popular due to the journey being less treacherous while that was the case later it became harder to go via the ocean due to colonial powers controlling the sea. The silk road being extremely dangerous and scattered with hostile powers, due to this the hajj was made non-mandatory for Hindu-Muslims.

Secondly, we have Buddhism which is still incredibly popular throughout present-day China. As stated in Exploration by Land: The Silk and Spice Routes by Paul Strathern in page 26

“The Buddhist religion originated in India in the 6th Century BCE. However, it seems it was not until the 1st Century CE with the trade routes fully open, that the religion spread up through Kushan and Sogdian territory into the Tarim Basin, and later into China itself.”

The religion travelled mainly through the silk road. The religion was not completely accepted in China until the Han dynasty. It may have been through the sea or the silk road that the missionaries entered China. The dates of the opening of the silk road and the rapid spread of Buddhism through the country have far too much correlation to believe that it did not have anything to do with the spread of the religion. China also sent a traveler Hiuen Tsiang as a pilgrim. It is some of the only account for the silk road east of India. The pilgrim travelled all over the northern part of the country and explored the culture and the monasteries of the land. A few centuries later another pilgrim was sent by China to recollect the holy books which may have been mistranslated in China.

As the book THE SILK ROAD by Gyan Prakash shoes. While Jainism and Buddhism were making waves through southeast Asia the Vedic traditions were going through reform within India and focused on the rural life. This is due to most of the Buddhist and Jains were trades and belonged to merchants who took the faiths to the rest of the world through the silk road and maritime routes. This new religion borrowed a lot of its traditions form Buddhism and Jainism, animal sacrifices were stopped, and meat eating was made taboo. They tried to separate from the tribble rituals and became a more so-called agrarian society. This is the most popular religion in India today. The reforms gave the religion a trinity of sorts of Brahma, Vishnu, and Mahesh. these gods split their roles as the creator, the maintainer, and the destroyer respectively. The most popular was Vishnu as the world was not ending any time soon. While shiva is popular with the people who fear the end of the world. It is said that Vishnu comes to earth to maintain dharma. Dharma is the work one was meant to do. For example, in the epic Mahabharat Krishna said to be an avatar of Vishnu guided him to kill the enemy even though they were family as that was his dharma. Due to the Brahmans focusing on the rural class of India this religion did not spread through the silk road as much. The religion did spread through the world much later due to the practice of indentured labor during the British rain which was due to people with the beliefs being moved.

Finlay no conversation about religion and the silk road is complete without the mention of Zoroastrianism a monotheistic religion from Persia which is a culmination of some Brahmanical practices and some stories resembling the ones found in India. Such as the cleansing nature of fire and struggle between the light and the dark powers. There have been accounts of fire temples on and around the silk road dating back to the 12th century. This shows that the chines wanted to attract the Persian trades to their country for trade.

This shows how the silk road has been an important factor for the spread of religion throughout the world especially through to the east. This also shows how religion changed within India seeing the effects of Buddhism on the world.

0 notes

Text

The Setting

Geographical Inspirations for "The Demon of the Well,"

by James B. Hendricks

Like Tolkien’s Middle Earth, the landscape that is the setting for The Demon of the Well may only be found within the confines of a story. But the dramatic landscapes of central Asia, north of Tibet gave me plenty of inspiration for the land that the trader and his companions inhabit. Back in 1979, when China opened Xinjiang – its western province – to the outside world, I learned a lot about this region. The great Tarim Basin, hemmed in by high mountains on three sides holds an ocean of shifting sand dunes called the Taklamakan Desert. Those mountains keep out the rain clouds, so only rivers of ice-melt from the bordering ranges reach its thirsty sands. Nearly all the rivers emerging from the Kunlun Mountains on the Tibetan plateau ultimately disappear into the dunes. Only one of these, the Hotan, is great enough to find its way 250 miles north through the sand dunes to join the waters of the Tarim River, which draws its origins from the Celestial Mountains north of the Taklamakan. The Yarkand River on the eastern fringe of the desert, also joins them there. The desert around which these rivers braid has such a fearsome reputation that few ventured far into it back in the old days. By tradition, it was a place where ‘You can go in, but you can never come out’.

And yet, there are ancient trade routes tracing its edges to the north and south, dotted with equally ancient oasis towns where rivers enter the desolation. These are a few of the myriad trails of the Old Silk Road. For many centuries, traders plied this network of trade routes with loads of silk and nephrite jade, providing inspiration for my protagonist’s occupation. East of the Taklamakan, by the expansive salt flats of Lop Nur, travelers on the southern route would have to make a perilous crossing – the trail there marked by the bones of camels who had perished on the trek. I have read that, according to local tradition, the endless gravel plains of this region are haunted by the ghosts of lost travelers, and that these spirits could be treacherous – finding stragglers in a caravan traveling by night and leading them off to their doom with the spectral sounds of camel bells. Details like this found their way into the pages of The Demon of the Well.

But for the geology of the story’s central focus, we must explore other parts of the world. The eerie wind-carved sandstone ‘goblins’ at the heart of the desert that I depict bear a strong resemblance to the hoodoos of Utah’s Bryce Canyon. Among those weird, sandstone pinnacles are a labyrinth of seemingly dry canyons. In my story at least, drinkable water may be found in these narrow canyon passages, if you know where to dig. But beyond the goblins and their bewildering network of canyons, you reach the strangest place of all.

In Ethiopia’s Afar Triangle region, cradled in a hot, dry desert called the Danakil Depression, is a network of boiling hot springs called Dallol by the Afar people. These saline and sulfur springs are heated by molten magma that long ago rose to the Earth’s surface through layers of salt and other strata laid down by an ancient sea. Its colorful springs and gaseous fumaroles look much like those found in the volcanic caldera of Yellowstone Park, in the western United States. Weird sulfur and salt formations, like those of the Dallol Springs, also surround the Devil’s Springs of my story, and similar gas fumaroles rise in the skies around it. The bright yellow of the sulfurous landscape even informs the appearance of the demon himself, when he is in his conversant aspect. It is fitting that such a powerfully destructive demon would have his home in a desert-bound volcanic caldera, waiting patiently to make his bargain with some passing fool. #demonofthewell

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dravidians of India & Egyptians

The Dravidian speakers originated in Africa, in modern day Sudan [11-12]. They expanded into Iran, on into the Indus Valley, across Central Asia into the Tarim Basin and China [8-10]. Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin ...

Some people claim that the Dravadians originally inhabited the Northern part of India and were later pushed to the southern part of the country by the Aryans. Hence about 28% of Indians are Dravidians and reside in South India with one of the Dravadian languages as their main language, which includes, Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada and Tulu. The Dravidian language has three subgroups, namely North Dravidian, Central Dravidian and South Dravidian. In present day India, the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu are the significant regions with a Dravidian population, the rest 72% are Aryans, residing in North India.The difference in the origin of these languages is the reason of the different South and North Indian accents. We know very little about the Dravidian people in India, who used to reside in the country before the Aryans invaded Northern India from Iran and Southern Russia.

https://www.mapsofindia.com/my-india/history/who-were-dravidians-in-india

1 note

·

View note

Text

Naturally mummified woman from Xiaohe cemetery. (Wenying Li/Xinjiang Institute)

Humans

We May Finally Know The Enigmatic Origins of Ancient Mummies Discovered in China

— Tessa Koumoundouros | October 27, 2021 | Science Aler

There's a a desert land in the very heart of Eurasia, dry enough to naturally mummify human remains. A Bronze Age discovery has now revealed the secret origins of the people who once called this region of China home.

The Xiaohe people's cattle-focused economy and difference in appearance have long posed questions about their origins. This led to speculation that they may have been the ancestors of migrants.

Researchers have proposed they originated from early dairy farmers of southern Russia (Afanasievo) or central Asian oasis farmers with Iranian plateau links.

A fragment of Tocharian B from a Buddhist kingdom at Tarim Basin edge. (Public Domain)

But a new genomic study that included analysis of the earliest discovered human remains of the region, has found that Xiaohe originated from an ancient Pleistocene population of hunter-gatherer humans that had largely disappeared by the end of the last ice age.

"Archaeogeneticists have long searched for Holocene Ancient North Eurasian populations in order to better understand the genetic history of Inner Eurasia. We have found one in the most unexpected place," said Seoul National University population geneticist Choongwon Jeong.

The Tarim basin, in what's now China's Xinjiang Region, is a dry inland sea with small oases and riverine corridors, fed by runoff from the isolating high mountains that surround it. Human activity here can be dated back to at least 40,000 years ago, and it's long been an intersection between the East and West – as a place along the renowned Silk Road.

Hundreds of human remains, naturally mummified by arid, cold, and salty soils, have been discovered in this basin since the 1990s. These brown-haired and long-nosed people were buried within unique coffins, like upside-down boats, in cemeteries.

Aerial view of the Xiaohe cemetery. (Wenying Li/Xinjiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology)

They were accompanied by felted and woven woolen clothing, bronze artifacts, cattle, sheep, goats, wheat, barley, millet, and even cheese.

Their farming and irrigation techniques suggested a link to the desert people with ties to the Iranian plateau. Others suspected they came through the Eurasian steppe from Russia, like their northern Dzungarian Basin neighbors.

They have even been associated with the movement east of Indo-European group of languages (from which English eventually emerged), as Buddhist texts from the Tarim Basin hold records of Tocharian, a now extinct branch of this family of languages.

However, after analyzing the genomes of 13 individuals of the Tarim Basin (from 2100 to 1700 BCE) along with five Dzungarian individuals (from 3000 to 2800 BCE), Jilin University geneticist Fan Zhang and team found none of these proposed origins were correct.

The Tarim mummies belong to an isolated gene pool of ancient Asian origins that can be traced all the way back to the early Holocene 9,000 years ago, well before Bronze Age farming communities emerged. This group of once hunter-gathers were likely to have had a much wider distribution previously, as their genetic traces are found through to Siberia.

"Despite being genetically isolated, the Bronze Age peoples of the Tarim Basin were remarkably culturally cosmopolitan, '' explained Harvard University anthropologist Christina Warinner. "They built their cuisine around wheat and dairy from West Asia, millet from East Asia, and medicinal plants like Ephedra from Central Asia."

The Xiaohe people look to be the most direct ancestors of pre-farming Asian populations that we know of, the researchers said. Their northern neighbors from the Dzungarian Basin also seem to be a mix of this ancient population as well as the Siberian migrants.

"The Tarim mummies' so-called Western physical features are probably due to their connection to the Pleistocene Ancient North Eurasian gene pool," the researchers wrote in their paper, explaining that the extreme genetic isolation kept them different from neighboring groups. This points "towards a role of extreme environments as a barrier to human migration."

— This research was published in Nature.

1 note

·

View note

Text

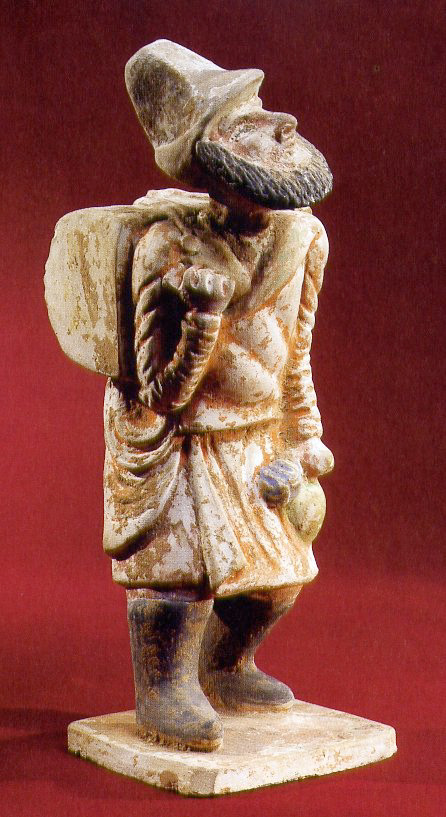

Foreign merchant (with Sogdian appearance) in China 618-907 CE

By the time the Hephthalites (White Huns) were destroyed the Sogdians had such a widespread influence that they were able to continue to enjoy their prosperity for another century. However, the crippling of the Hun's power by the Turks and Persians also eliminated Sogdiana's safety net and made them vulnerable. The chaos created to the east by the Turkic An Lushan rebellion in China and the chaos created to the west by the Sassanid's blundered aggression closed the doors on the Sogdian era of prosperity that had begun under Hunnic rule. Even after the An Lushan rebellion ended, China [one of the Sogdian's most important trading partners] was in ruins and vulnerable to other threats. Trade routes were choked off by hostile armies. Instability meant more danger for travelers. Sassanid rule had become so dysfunctional that the primitive Arab Muslims were able to conquer Persia, afterward pushing on into Sogdiana. The Hephthalites were no longer there to stabilize the Persian government as they had done in the time of Peroz and Khuvad. The Sassanids had gained their financial freedom from the Hephthalites and then, less than a century later, used that freedom to destroy themselves.

"In July of 751, a Tang army was defeated at the battle of Talas at the hands of a Turgesh-Arab alliance. The defeat effectively ended the Tang’s ability to intervene in Asia beyond the Tarim Basin. This defeat and the Tang’s subsequent inability to project force beyond the Tarim Basin played as important role in the downfall of the Sogdians as the Arab invasions themselves. With the Tang military held behind the Pamirs, the Tibetans moved to occupy the passes leading into China and into Kashmir, creating a chokehold on valuable trade networks the Sogdian merchants depended on for their livelihoods. Campaigns in 747 CE and 753 CE served to ease these Tibetan holds on the passes, but relief was only temporary. The Tang loss at Talas freed the invading Arabic forces to take control of Central Asia as well as weakening the Tang’s ability to cope with longstanding enemies closer to home. The situation for both the Sogdians and the Tang was only going to worsen. Taking advantage of the inner turmoil caused by An Lushan’s rebellion, Tibetan troops marched on and captured Chang’an in 763 CE. Rather than attempting to hold the city the Tibetans gradually withdrew along the Gansu corridor. Movement up this major trade artery by a hostile army could only have disrupted the Sogdian’s trade network, which was already likely in poor condition due to rebellions and the depredations of preceding armies. As the Tibetans withdrew they occupied the cities they encountered along the way, taking first Liangzhou (764) in the east and eventually Hami (781–782) in the west. At least two key Sogdian colonies at Hami and Chang’an, would have been seriously damaged by the rampaging Tibetans.

It is also quite likely that throughout their operations in China, Sogdian wealth would have proved a tempting target for looting by invading armies such as the Tibetans or rebelling generals. The Tibetan occupation of the passes restricted any influx of Sogdian immigrants into China to bolster the reeling Sogdian communities. With China wracked by invasions and rebellions, their Chinese colonies in ruins, the mistrust of the Sogdian people by the Tang due to the rebellion of An Lushan, and their homeland occupied by invading armies, the Sogdian trade network and nation could not but have suffered grievously. Previously the Sogdians had shown a remarkable ability to escape destruction, but the combination of forces besieging them eventually proved too great.

The Sogdians embodied the spirit of the Silk Road perhaps better than any other people. The Silk Road functioned as a conduit for exchange of both ideas and goods. The Sogdians for hundreds of years served as an invaluable vehicle for that exchange."

-The "Silk Roads" in Time and Space: Migrations, Motifs, and Materials. Edited by Victor H. Mair. Sino-Platonic Paper 228.

#sogdiana#tang dynasty#chinese art#ancient history#silk road#history#antiquities#art#sculpture#statue#ancient art

16 notes

·

View notes