#E-OMNE

Text

Little Rock FD Truck 9

#larryshapiro.tumblr.com#shapirophotography.net#fire truck#firetruck#larryshapiro#larryshapiroblog.com#larry shapiro#EONE#EONEStrength#E-OMNE#Cyclone#HR100#LittleRockFD#Little Rock Fire Department#Little Rock AR#state capitol

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ohhhhh oh how about "One talking to the other when they think they're asleep" for Maria and Fenris pretty please?

Thank you for the prompt! <3 I had to ponder this a bit, but I am happy with the results c:

("Sharing a bed" prompts here; I am still open c:)

(Also, please forgive my rusty Latin; it's been eight years since I've had to actually use it for anything more than a party trick. I've also fiddled with the translation below for flow. Apologies to the memory of Catullus)

Tevene/Latin:

Tuus sum: I am yours

Corpus animaque: Body and soul

Placideque quiescas: Rest well and peacefully

Fenris/Maria Hawke | 1,138 Words | No warnings

Corpus Animaque

"Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love,

and the rumors of rather stern old men

let us value all at just one penny!

Suns may set and rise again;

for us, when once the brief light has set,

an eternal night must be slept.

Give me a thousand kisses, then a hundred,

then another thousand, then a second hundred,

then yet another thousand, then a hundred;

then, when we have performed many thousands,

we shall stir them into confusion, so that we might not know,

and in order not to let any wicked person envy us,

when he knows that our kisses number so many."

---Catullus 5*

“Say something in Tevene,” Hawke had murmured to him perhaps half an hour ago.

Fenris, who was now well versed in what Hawke sounded like when she was trying to force herself to stay awake, had obliged. He’d taught her hello and goodbye, then described the room at length in disinterested tones, all the while allowing his voice to grow ever quieter. Maria slept deeply now, her cheek pillowed on her arm atop the pillow, and Fenris let his head rest on its side so he could watch her.

It had been strange to speak the tongue of his birth with her—odd, like two halves of his life twining when he’d expected them to be forever as water and oil. There was something, though, in speaking to Maria when he knew she could not understand him. Fenris pondered this for a time, listening to the crackle of the fire at her hearth and the soft whistle of her sleeping breath.

“Cor mea,” Fenris murmured after a moment: my heart, a simple enough endearment.

Hawke did not stir. She’d rested her hand near his shoulder, as she often did, and he’d obligingly twined his fingers with hers. Fenris set his other hand over both now, cradling her hand between his.

There were things he ought to say to her. He knew that. But even now, when he was certain there would be no leaving her, words of love refused to slip easily from his lips. Not in the common tongue; not even in the one he’d spoken for most of his life.

Not his own words; perhaps the words of others would come to him more easily.

“Vivamus, mea Maria, atque amemus,” he murmured, feeling the pulse at her wrist where it pressed against his, “rumoresque senum severiorum onmes unius aestemimemus assis.”

Maria pulled her hair back in a red silk scarf when she slept. It prevented her hair from tangling too badly in the night and kept either of them from rolling onto her bounty of curls while they slept. Now, a small curl had snuck from its confines just below her ear, threatening to tickle the sensitive skin and wake her. Fenris lifted one hand and tucked it back with the rest, moving slowly and carefully. Hawke did not stir, for which he was grateful. There was more yet to say.

“Soles occidere et redire possunt;” Fenris went on, “nobis, cum semel occidit brevis lux, nox est perpetua una dormienda.”

An eternal night indeed; they had, both of them, seen enough of death to last several lifetimes. Her pulse thrummed steadily against his own, as if in sweet answer to the unspoken undertone to the words. They were alive now, the two of them; whatever rest they might share tonight was not that long rest, but the blink of an eye in the span of their days.

There will be other nights, she’d told him once. He dwelled too heavily on dreadful possibilities now. While she still slept…let him finish this, at least.

Fenris spoke the rest of the words—give me a thousand kisses, then a hundred, then another thousand—meaning each of them as he spoke. They were not his words; they were borrowed from someone he’d never met. Even so, they seemed intended for something like this: a room that held only the two of them, an unusually clear night in Kirkwall which showed the stars clearly through her bedroom window, and the gradually softening light from the fire that kept them warm. Such words should be exchanged in whispers and the touches of hands, intended only for a lover’s ears.

It felt wrong to end with the poem, but Fenris didn’t have to cast about for something to end with. There were other words he’d told her before, words he’d conveyed in a dozen different ways if not a hundred. He’d seen her concern when he’d said them the first time—I am yours—as if she was worried about why he might say that. As if she thought he’d somehow conflated her with those who would have owned him once.

The whole of it was too much to explain, too strange to say aloud: if I may at last choose what to do with my life, I choose to give it to you. I would give all of myself to you if I could, because you would never ask me to, because you have insisted on seeing me as a person from the first moment we met.

Too formal.

Too many possible hidden meanings, when he’d first said the words to her in those bruised days after that disastrous night together. Fenris had chosen the easiest ones instead of the explanation, willing to risk her concern in exchange for some level of understanding.

It was easier now; he could say them with more affection, and she’d returned the words more than once. They meant something different when Hawke said them, but that had never bothered him.

“Tuus sum,” Fenris told her now, the words feeling firmer in this language, more binding—though the weight of them was a comfortable one, words and bonds he’d chosen rather than ones that had been chosen for him.

“Corpus animaque,” Fenris finished, his voice hardly more than a whisper, “placideque quiescas, cor mea.”

It seemed fitting, somehow, to dip his head and kiss her hand then. If he were less tired, he may have considered why such an implicit vow had felt necessary. Matters had passed tense in Kirkwall weeks ago and slid unstoppably toward some imminent danger. Fenris could not smooth her way; he could not fight her battles for her.

But he could hold her hand in the night, and whisper to her of kisses and days to come. He could stay by her side as long as she would allow him.

As long as there was strength in his arms, as long as he could stand with her, he believed he would see her safe. He had never been an optimist; if pressed, he would not wager on their odds.

But Hawke—he believed in her. If anyone could navigate them out of this disaster, it was her.

“Mea cor,” he said one more time, setting her hand back over his chest with exquisite care.

The time for words had passed. It was past time for rest. Fenris looked at Hawke once more before he closed his eyes, tracing the shadows of her face, the softness of her eyelids, the unfading smile lines on either side of her mouth. When he’d looked his fill for now (only for now; it could never be enough for forever, as he knew well), Fenris closed his eyes at last.

It was much longer before his focus slipped from the steady pulse in her wrist and Fenris fell asleep at last.

*Base source for translation: Wikipedia

(I know, there are prettier versions elsewhere, but it's nearly one am and i don't want to look)

#maria hawke#fenris#fenhawke#my writing#da2#hawke#i do love the idea of fenris finding it easier to be outwardly affectionate in tevene vs the common tongue#something about her not being able to understand him allowing him to say more than he otherwise would#i am going to keep thinking about this i can tell#is it crimes that i swapped lesbia with maria? maybe. but it still scans so#filed under: choices that would have made my latin professor shake her head in gentle confusion#now i know what you're thinking#and you're right: many of ovid's poems would fit them better#but i take exception with corinna being like the personification of poetry or w/e#at least catullus was writing his poems to a real woman even if she was married to someone else#(i know i know; you weren't thinking that but it's okay. ovid is an exceptional poet and i can non sum desultor amoris#or militat omnes amans with the best of them)#do you ever write a series of sentences and wonder if they come off as pretentious? hmm#not my intent; i just miss latin and the class i took that was just ovid translation#upon reflection i am deleting none of it; you will all just have to live with my opinions about the amores#thanks again for the prompt lol!! i hope it wasn't too much latin c:#shivunin scrivening

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was tagged by @marimayscarlett to post my 5 favourite songs at the moment 🎶 Thank you dear!

Tagging @samshinechester @meinewellemeinstrand @vulnerant-omnes @morgana-lefay @franwikema @frampk @naomullen @itconsumesyou @gabibbo06 💚

318 notes

·

View notes

Text

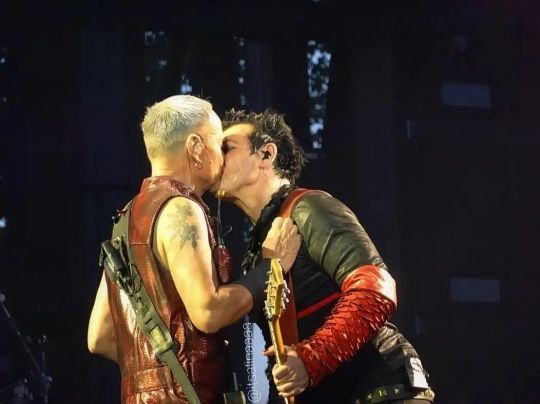

Little recap of the last concert in Gelsenkirchen // some of the most memorable things for me 🤍

First of all, spending the day and/or concert with @m---e---l, @vulnerant-omnes @tinnike and @iinchicore - laughed, cried, had a great time with you all, thank you a lot ladies 🤍

Hug in the elevator - I saw no feet in the elevator, panicked (❗), then saw the group hug and bawled so hard my contact lenses got out of place 🤙🏻

Richard's growling. I will not elaborate, but rest assured, I did have several thoughts about it:

Puppe cam: Till abandoning the band to play the same melody for about 4 minutes and his appreciation of backstage staff 🤲🏼

Butcher Till with sparkly hat, apron and dick out. A summer look 🌞

"Mit Maggi macht das Kochen Spaß" - Till getting passed a bottle of Maggi instead of a flamethrower for the Flake-soup 🍲

hallucinatory corner™: my delusional ass thinking that Richard nodded in acknowledgement when he saw my hand-heart 🫶🏻 (he most likely absolutely didn't)

Paulchard Polonaise - no kiss, but party dance 🪩 -> but then later: Pussy Paulchard kiss - blink and you get foam in your eyes and miss it 💋

Fan cam time partly used for some Rammstein crew appreciation 🙏🏻

Richard's boat ride with Maxime (dad being 😬😵💫, daughter being 😃👐🏻)

Sleeveless Richard + stripping his coat very enthusiastically (no, I have not recovered from this, my phone almost slipped out of my hand during this)

Richard holding on to Till's sleeve and pulling him into a hug and Till hugging him just as tight 🫂

Paul crying, Schneider being on the verge of tears, Richard barely holding on while Olli dances in the elevator 🕺🏻

little sweet moments after the concert: meeting a lady from the Frankfurt concert a few weeks back, random lady checking in on me while I bawled my eyes out after the concert, and random guy complimenting my red dress, telling me he loves the DRSG mv and later screaming 'Du riechst so gut!' at me from his car window and waving 👋🏻

Couldn't have wished for a better last concert or nicer people to spend it with. It was magical 💗

(thank you @vulnerant-omnes for taking this picture 🤍)

#rammstein#maria rambles once again#so kinners. keine ahnung was ich mit meinem leben jetzt anfangen soll#mit nem stein um den hals in den rhein oder was i don't know#sinn des lebens komm raus

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

frases cristãs em latim para bio.

solus Christus (somente Cristo);

omnes enim Christus (tudo por Cristo);

de fideli (com fidelidade);

Deus est Deus (Deus é Deus);

Dei gratia (pela graça de Deus);

Deo gratias (graça à Deus);

Deo ac veritati (por Deus e pela verdade);

Deo confidimus (em Deus confio);

Deo juvante (com a ajuda de Deus);

Deo, non fortuna (com a ajuda de Deus, não de sorte);

Deus caritas est (Deus é amor);

nobiscum Deus (Deus conosco);

Deus spes nostra (Deus é nossa esperança).

#bio ideas#bios ideas#random bios#short bios#twitter bios#simple bios#random bio#twitter bio#short bio#simple bio#bio aesthetic#bio messy#messy bio#aesthetic bio#aesthetic bios#bio#bios#latim#latin#quotes#latin quotes#jesus bio#jesus bios#christianity#bios cristas#bio cristã#bio inspo

369 notes

·

View notes

Text

Did the ancient Celts really paint themselves blue?

Part 1: Brittonic Body Paint

Clockwise from top left: participants in the Picts Vs Romans 5k, a 16th c. painting of painted and tattooed ancient Britons, Boudica: Queen of War (2023), Brave (2012).

The idea that the ancient and medieval Insular Celts painted themselves blue or tattooed themselves with woad is common in modern culture. But where did this idea come from, and is there any evidence for it? In this post, I will examine the evidence for the use of body paint among the ancient peoples of the British Isles, including both written sources and archaeology.

For this post, I am looking at sources pertaining to any ethnic group that lived in the British Isles from the late Iron Age through the early Roman Era. (Later Roman and Medieval sources will be discussed in part 2.) The relevant text sources for Brittonic body paint date from approximately 50 BCE to 100 CE. I am including all British Isles cultures, because a) determining exactly which Insular culture various writers mean by terms like ‘Briton’ is sometimes impossible and b) I don’t want to risk excluding any relevant evidence.

Written Sources:

The earliest source for our notion of blue Celts is Julius Cesar's Gallic War book 5, written circa 50 BCE. In it he says, "Omnes vero se Britanni vitro inficiunt, quod caeruleum efficit colorem, atque hoc horridiores sunt in pugna aspectu," which translates as something like, "All the Britons stain themselves with woad, which produces a bluish colouring, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible" (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). Hollywood sometimes interprets this passage as meaning that the Celts used war paint, but Cesar says that all Britons colored themselves, not just the warriors. The blue coloring just had the effect (on the Romans at least) of making the Briton warriors look scary. The verb inficiunt (infinitive inficio) is sometimes translated as 'paint', but it actually means dye or stain. The Latin verb for paint is pingo (MacQuarrie 1997).

The interpretation of vitro as woad is supported by Vitruvius' statements in De Architectura (7.14.2) that vitrum is called isatis by the Greeks and can be used as a substitute for indigo. Isatis is the Greek word for woad; this is where we get its modern scientific name Isatis tinctoria. Woad and indigo both contain the same blue dye pigment, hence woad can be used as a substitute for indigo (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016). The word vitro can also mean 'glass' in Latin, but as staining yourself with glass doesn't make much sense, it's more commonly interpreted here as woad (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997). I will revisit this interpretation during my discussion of the archaeological evidence.

Almost a century later in De situ orbis, Pomponius Mela says that the Britons "whether for beauty or for some other reason — they have their bodies dyed blue," (translation by Frank E. Romer) using virtually identical language to Cesar, "vitro corpora infecti" (Lib. III Cap. VI p. 63). Pomponius Mela may have copied his information from Cesar (Hoecherl 2016).

Then in 79 CE, Pliny the Elder writes in Natural History book 22 ch 2, "There is a plant in Gaul, similar to the plantago in appearance, and known there by the name of "glastum:" with it both matrons and girls among the people of Britain are in the habit of staining the body all over, when taking part in the performance of certain sacred rites; rivalling hereby the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians, they go in a state of nature." In spite of the fact that glastum means woad in the Gaulish and Celtic languages, Pliny seems to think glastum is not woad. In Natural History book 20 ch 25, he describes different plant which is almost certainly woad, a “wild lettuce” called "isatis" which is "used by dyers of wool." (Woad is a well-known source of fabric dye (Speranza et al 2020)).

Of course, "rivaling the swarthy hue of the Æthiopians" doesn't necessarily mean blue. Pliny seems to think Ethiopians literally have coal-black skin (Latin ater). Additionally, Pliny is taking about a ritual done by women, where Cesar was talking about a practice done by everyone. Are they talking about 2 different cultural practices, or is one of them reporting misinformation? Or are both wrong? Unfortunately, there is no way to know.

The Roman poets Ovid, Propertius, and Marcus Valerius Martialis all make references to blue-colored Britons (Carr 2005), but these are literary allusions, not ethnographic reports. As such, they don't really provide additional evidence that the Britons were actually dyeing or painting themselves blue (Hoecherl 2016). These poetic references merely demonstrate that the Romans believed that the Britons were.

In the sources that come after Pliny the Elder, starting in the 3rd century, there is a shift in the terms used. Instead of inficio which means to dye or stain (Hoecherl 2016), probably a temporary application of color to the surface of the skin, later sources use words like cicatrices (scars) and stigma/stigmata (brand, scar, or tattoo) (Hoecherl 2016, MacQuarrie 1997, Carr 2005) which suggest a permanent placement of pigment under the skin, i.e. a tattoo. This evidence for tattooing will be discussed in a second post.

Discussion:

Although the Romans clearly believed that the Britons were coloring themselves with blue pigment, that doesn't necessarily mean that Julius Cesar, Pomponius Mela, or Pliny the Elder are reliable sources.

In the sentence before he claims that all Britons color themselves blue, Julius Cesar says that most inland Britons "do not sow corn [aka grain], but live on milk and flesh and clothe themselves in skins." (translation from MacQuarrie 1997). This is demonstrably false. Grains like wheat and barley and storage pits for grain have been found at multiple late Iron Age sites in inland Britain (van der Veen and Jones 2006, Lightfood and Stevens 2012, Lodwick et al 2021). This false characterization of Insular Celts as uncivilized savages would continue to show up more than a millennium later in English descriptions of the Irish.

Pomponius Mela, in addition to believing in blue-dyed Britons, also believed that there was an island off the coast of Scythia inhabited by a race called the Panotii "who for clothing have big ears broad enough to go around their whole body (they are otherwise naked)" (Chorographia Bk II 3.56 translation from Romer 1998). Pliny the Elder also believed in Panotii.

15th-century depiction of a Panotii from the Nuremberg Chronicle. Was Celtic body paint as real as these guys?

The Roman historians Tacitus and Cassius Dio make no mention of body paint in their coverage of Iron Age British history (Hoecherl 2016). Their silence on the subject suggests that, in spite of Cesar's claim that all Britons colored themselves blue, the custom of body staining or painting was not actually widespread.

Considering all of these issues, is any of this information trustworthy? Based on my experience studying 16th c. Irish dress, even bigoted sources based on second-hand information often have a grain of truth somewhere in them. Unfortunately, exactly which bit is true is hard to identify without other sources of evidence, and this far in the past we don't have much.

Archaeological Evidence:

There are no known artistic depictions of face paint or body art from Great Britain during this time period. There are some Iron Age continental European coins that show what may be face painting or tattoos, but no such images have been found on British coins (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

In order for the Britons to have dyed themselves blue, they needed to have had blue pigment. Woad is not native to Great Britain (Speranza et al 2020), but Woad seeds have been found in a pit at the late Iron Age site of Dragonby in England, so the Britons had access to woad as a potential pigment source in Julius Cesar's time (Van der Veen et al 1993). Egyptian blue is another possible source of blue pigment. A bead made of Egyptian blue was found at a late Bronze Age site in Runnymede, England. Pieces of Egyptian blue could have been powdered to produce a pigment for body paint. (Hoecherl 2016). Egyptian blue was also used by the Romans to make blue-colored glass (Fleming 1999). Perhaps this is what Cesar meant by 'vitro'.

Potential sources of blue: Isatis tinctoria (woad) leaves and a lump of Egyptian blue from New Kingdom Egypt

Modern experiments have found that reasonably effective body paint can be made by mixing indigo powder either with water, forming a runny paint which dries on the skin, or with beef drippings, forming a grease paint which needs soap to be removed (Carr 2005, reenactor description). The second recipe is very similar to one used by modern east African argo-pastoralists which consists of ground red ocher mixed with cow fat (unpublished interview*).

Finding blue pigment on the skin of a bog body might confirm Julius Cesar's claim, but unfortunately, the results here are far from conclusive. To my knowledge, Lindow II is the only British bog body that has been tested for indigotin, the dye pigment in woad and indigo. No indigotin was found (Taylor 1986).

The late Iron Age-early Roman era bog bodies Lindown II and Lindown III show some evidence of mineral-based body paint (Joy 2009, Giles 2020). Both of them have elevated levels of calcium, aluminum, silicon, iron, and copper in their skin. Lindow III also has elevated levels of titanium. The calcium levels may simply be the result the of the bog leeching calcium from their bones. Some researchers have suggested that the other elements may be from mineral-based paints applied to the skin. The aluminum and silicon may be from clay minerals. The iron and titanium could be from red ocher. The copper could be from malachite, azurite, or Egyptian blue (CuCaSiO4), pigments that would give a green or blue color (Pyatt et al 1995, Pyatt et al 1991). These elements may have other sources however, and are not present in large enough amounts to provide definitive proof of body paint (Cowell and Craddock 1995, Giles 2020). Testing done on the early Roman Era (80-220 CE) Worsley Man has found no evidence of mineral-based paint (Giles 2020).

One final type of artifact that provides some support for Julius Cesar's claim is a group of small cosmetic grinders from late Iron Age-Roman Era Britain. These mortar and pestle sets are found almost exclusively in Great Britain and are of a style which appears to be an indigenous British development. They are distinctly different from the stone palettes used by the Romans for grinding cosmetics which suggests that these British grinders were used for a different purpose than making Roman-style makeup (Carr 2005). Archaeologist Gillian Carr has suggested that these British grinders might have been used by the Britons for grinding, mixing, and applying a woad-based body paint (Carr 2005).

Left and center: Cosmetic grinder set from Kent. Right: Cosmetic mortar from Staffordshire. images from Portable Antiquities Scheme under CC attribution license

The mortars have a variety of styles of decoration, but the pestles (top left and top center) typically feature a pointed end which could be used for applying paint to the skin (Carr 2005). The grinders are quite small, (most are less than 11 cm (4.5 in) long), making them better suited to preparing paint for drawing small designs rather than for dyeing large areas of skin (Carr 2005, Hoecherl 2016).

Conclusions:

Admittedly, this post is a bit off-topic, since the Irish are not mentioned, but dress history is also about what people did not wear. Hollywood has a tendency to overgeneralize and expropriate, so I want to be clear: There is no known evidence that the ancient Irish used body paint.

So, who did? For the reasons I have already discussed, I don't consider any of the Roman writers particularly trustworthy, but I think the following conclusions are plausible:

A least a few people in Great Britain dyed/stained or painted their bodies between circa 50 BCE and perhaps 100 CE, after which mentions of it end. Written sources from c. 200 CE on talk about tattoos rather than painting or staining. The custom of body dyeing/painting may have started as something practiced by everyone and later changed to something practiced by just women.

None of the writers mention any designs being painted, but Julius Cesar's description could encompass designs or solid area of color. Pliny, on the other hand, states that women were coloring their entire bodies a solid color. The dye was probably blue, although Pliny implies it was black. (I know of no plants in northern Europe that resemble plantago and produce a black dye. I think Pliny was reporting misinformation.)

Archaeological evidence and experimental recreations support the possibility that woad was the source of the pigment, but they cannot confirm it. Data from bog bodies indicate that a mineral pigment like azurite or Egyptian blue is more likely, but these samples are too small to be conclusive.

The small cosmetic grinders are suitable for making designs which might match Cesar and Mela's descriptions, but not Pliny's description of all-over body dyeing.

*Interview with a Daasanach woman I participated in while doing field school in Kenya in 2015.

Leave me a tip?

Bibliography:

Carr, Gillian. (2005). Woad, Tattooing and Identity in Later Iron Age and Early Roman Britain. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00236.x

Cowell, M., and Craddock, P. (1995). Addendum: Copper in the Skin of Lindow Man. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 74-75). British Museum Press.

Fleming, S. J. (1999). Roman Glass; reflections on cultural change. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Roman_Glass/ONUFZfcEkBgC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Giles, Melanie. (2020). Bog Bodies Face to face with the past. Manchester University Press, Manchester. https://library.oapen.org/viewer/web/viewer.html?file=/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/46717/9781526150196_fullhl.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Joy, J. (2009). Lindow Man. British Museum Press, London. https://archive.org/details/lindowman0000joyj/mode/2up

Lightfoot, E., and Stevens, R. E. (2012). Stable Isotope Investigations of Charred Barley (Hordeum vulgare) and Wheat (Triticum spelta) Grains from Danebury Hillfort: Implications for Palaeodietary Reconstructions. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(3), 656–662. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2011.10.026

Lodwick, L., Campbell, G., Crosby, V., Müldner, G. (2021). Isotopic Evidence for Changes in Cereal Production Strategies in Iron Age and Roman Britain. Environmental Archaeology, 26(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14614103.2020.1718852

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

Pomponius Mela. (1998). De situ orbis libri III (F. Romer, Trans.). University of Michigan Press. (Original work published ca. 43 CE) https://topostext.org/work/145

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Buckland, P.C., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Storey, D.M. (1995). Mobilization of Elements from the Bog Bodies Lindow II and III and Some Observations on Body Painting. In R. C. Turner and R. G. Scaife (eds) Bog Bodies: New Discoveries and New Perspectives (p. 62-73). British Museum Press.

Pyatt, F.B., Beaumont, E.H., Lacy, D., Magilton, J.R., and Buckland, P.C. (1991) Non isatis sed vitrum or, the colour of Lindow Man. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 10(1), 61–73. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227808912_Non_Isatis_sed_Vitrum_or_the_colour_of_Lindow_Man

Speranza, J., Miceli, N., Taviano, M.F., Ragusa, S., Kwiecień, I., Szopa, A., Ekiert, H. (2020). Isatis Tinctoria L. (Woad): A Review of Its Botany, Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Biotechnical Studies. Plants, 9(3): 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9030298

Taylor, G. W. (1986). Tests for Dyes. In I. Stead, J. B. Bourke and D. Brothwell (eds) Lindow Man: the Body in the Bog (p. 41). British Museum Publications Ltd.

Van der Veen, M., and Jones, G. (2006). A Re-analysis of Agricultural Production and Consumption: Implications for Understanding the British Iron Age. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 15 (3), 217–228. doi:10.1007/s00334-006-0040-3 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/27247136

Van der Veen, M., Hall, A., and May, J. (1993). Woad and the Britons painted blue. Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 12(3), 367-371. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249394983

#cw anti-black racism#romano-british#period typical bigotry#iron age#bog bodies#no photographs of bog bodies though#roman era#ancient celts#celtic#woad#insular celts#anecdotes and observations#body paint#brittonic#archaeology

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

DA RECITARE IL SABATO

INDULGENZE CONCESSE ALL’ANTICA ORAZIONE “PIETATE TUA”

DA RECITARE PER QUATTRO SABATI CONSECUTIVI_

Papa Leone XII, il 9 Luglio 1828, concesse quaranta giorni di Indulgenza a tutti coloro che reciteranno la seguente Orazione.

Concesse inoltre CENTO ANNI (non giorni!) o cento quarantene, quando si recita tutti i sabati del mese.

PREMESSA:

Che meraviglioso tesoro che la Santa Chiesa ci dona, e con la quale possiamo liberare tantissime Anime dal Purgatorio dalle dolorose sofferenze che patiscono anche per lunghissimi anni!

Un di’ in punto di morte capiremo quali enormi vantaggi avremo ottenuto per la nostra anima, con l’applicazione di tali indulgenze alle Anime Purganti.

ORAZIONE:

Ti preghiamo, o Signore, che Tu voglia nella tua infinita misericordia scioglierci dai nostri peccati, e per l’intercessione della Beatissima Vergine Madre di Dio Maria, degli Apostoli Pietro e Paolo e di tutti i Santi, degnati conservare noi tuoi servi, i nostri paesi e le nostre abitazioni in perfetta santita’; purificare tutti i nostri parenti, amici e conoscenti da ogni peccato, e glorificarli con ogni virtu’; darci la salute e la pace; allontanar da noi tutti i nostri nemici visibili ed invisibili; frenare i desideri della carne, conservare la sanita’ dell’aria, accordare la santa carita’ tanto ai nostri amici, quanto ai nemici; difendere la nostra citta’ ( o paese ); conservare il nostro Sommo Pastore il Papa N.N., tutti i nostri superiori spirituali, i Principi, e difendere da ogni disgrazia tutto il popolo cristiano.

La tua santa benedizione riposi sempre sopra di noi, e a tutti i fedeli defunti concedi la pace perpetua, per Gesù Cristo Nostro Signore.

Così sia.

CONSIDERAZIONI:

Per molti aspetti questa antica Orazione sembra attualissima, ma quello che colpisce in modo particolare sono i CENTO ANNI di Indulgenza concessi a tutti coloro che la reciteranno tutti i sabati del mese.

Se pensiamo che talune anime giacciono da centinaia di anni tra le fiamme del Purgatorio e che puo’ bastare una preghiera come questa, recitata ovviamente nelle condizioni di animo previste dalla Chiesa, a liberarle finalmente da quel luogo di tormento, dovrebbe spronarci a recitarla tutti i sabati ( due minuti appena), ben sapendo poi dell’immenso dono che potremo fare a queste anime cosi’ sofferenti da lunghissimo tempo, e ai benefici che ne ricaveremo per le nostre anime soprattutto nel giorno del giudizio!

PER CHI VOLESSE PREGARLA IN LATINO:

PIETATE tua, quaesumus, Domine, nostrorum solve vincula peccatorum, et intercedente beata semperque Virgine Dei Genetrice Maria cum beato Ioseph ac beatis Apostolis tuis Petro et Paulo et omnibus Sanctis, nos famulos tuos et loca nostra in omni sanctitate custodi; omnes consanguinitate, affinitate ac familiaritate nobis coniunctos a vitiis purga, virtutibus illustra; pacem et salutem nobis tribue; hostes visibiles et invisibiles remove; carnalia desideria repelle: aerem salubrem indulge; amicis et inimicis nostris caritatem largire; Urbem tuam custodi; Pontificem nostrum N. conserva; omnes Praelatos, Principes cunctumque populum christianum ab omni adversitate defende. Benedictio tua sit super nos semper, et omnibus fidelibus defunctis requiem aeternam concede.

Amen

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE JOHNNT CADE SPAM THING IS AWAKENING ME

I N EED HIM. SXO BAD GUYS PELASE

IF HES NOT OILED UP AND TIEDC DOWN TO MY BED IN THE NEXT 5 SECONDS IM GONNA DCO SOMETHIN G IM GONNA EGRET.

PLEAZSXEE\

OMNE C HAN CE

ON E CHAN C E JOHNNN Y PELASDE

ON E V HANCE 😭😭😭😭😭😭😭😭

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tutti volano via

Non ad nos stat nec unus dies. Nec unus dies ad nos stat: fugiunt omnes. Antequam venit, abscedit. De hoc ergo die, ex quo loquimur, quantum iam fugit! Nec horam, in qua sumus, tenemus. Fugit et ipsa, venit et alia, nec ipsa statura sed fugitura.

Cioè, all'incirca:

Con noi non sta fermo neppure un solo giorno. Con noi non si ferma neanche un solo giorno: tutti fuggono via. Prima di arrivare già se n'è andato. Dunque di questo giorno in cui parlo, quanta parte già se n'è andata! Non possiamo neppure trattenere l'ora in cui siamo. Fugge anch'essa e ne arriva un'altra, e neanche questa starà ferma ma se ne fuggirà via.

Nota: Un copiaincolla senza annotazioni, ma dai Sermoni [397-398] di S. Agostino.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Omneic

Omneic : a term for nonhuman system members (or extranthropes [1]) who are attracted to multiple/all nonhuman identities.

Etymology : Omne - Omni with an e | Omni means all

pt: omneic

this term is under the Echidiaen umbrella [link] || original post [link]

similar terms: gleichaeus [2] || medusan [3]

#omneic#echidiaen#plural gang#pluralgang#plurality#plural terms#system coining#liom coining#system terms#liom term#liom

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Requiem per l’Occidente

Verso la fine del XIX secolo, Moritz Steinschneider, uno dei fondatori della scienza del giudaismo, dichiarò, non senza scandalo di molti benpensanti, che la sola cosa che si poteva fare per il giudaismo era assicurargli un degno funerale. È possibile che da allora il suo giudizio si applichi anche alla Chiesa e alla cultura occidentale nel suo complesso. Quel che di fatto è, tuttavia, avvenuto è che il degno funerale di cui parlava Steinschneider non è stato celebrato, né allora per il giudaismo né ora per l’Occidente.

Parte essenziale del funerale nella tradizione della chiesa cattolica è la messa detta di Requiem, che nell’Introito si apre appunto con le parole: Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat eis. Fino al 1970, il missale romano prescriveva inoltre per la messa di requiem la recitazione nella sequenza del dies irae. Questa scelta era perfettamente conseguente col fatto che il termine stesso che definiva la messa per i defunti proveniva da un testo apocalittico, l’Apocalisse di Esdra, che evocava insieme la pace e la fine del mondo: requiem aeternitatis dabit vobis, quoniam in proximo est ille, qui in finem saeculi adveniet, «vi darà la pace eterna, perché è vicino colui che viene alla fine del tempo». L’abolizione del dies irae nel 1970 va insieme all’abbandono di ogni istanza escatologica da parte della Chiesa, che si è in questo modo del tutto conformata all’idea di un progresso infinito che definisce la modernità. Ciò che viene lasciato cadere senza il coraggio di esplicitarne le ragioni – il giorno dell’ira, l’ultimo giorno – può essere raccolto come u’arma da usare contro le viltà e le contraddizioni del potere al momento della sua fine. È quanto intendiamo qui fare, provandoci a celebrare senza intenzione parodica, ma al di fuori della Chiesa, che appartiene al numero dei defunti, una sorta di funerale abbreviato per l’occidente.

Dies irae, dies illa

solvet saeclum in favilla,

teste David cum Sybilla.

Giorno d'ira, quel giorno

distruggerà il mondo nella cenere,

come testimoniano Davide e la Sibilla.

Di che giorno si tratta? Certamente del presente, del tempo che stiamo vivendo. Ogni giorno è il giorno dell’ira, l’ultimo giorno. Oggi il secolo, il mondo sta bruciando, e con esso anche la nostra casa. Di questo dobbiamo essere testimoni, come Davide e come la Sibilla. Chi tace e non testimonia, non avrà pace né ora né domani, perché è appunto la pace che l’occidente non può né vuole vedere né pensare.

Quantus tremor est futurus

quando iudex est venturus

cuncta stricte discussurus.

Quanto terrore ci sarà,

quando verrà il giudice,

per giudicare rigorosamente ogni cosa.

Il terrore non è futuro, è qui e ora. E quel giudice siamo noi, chiamati a pronunciare il giudizio, la krisis sul nostro tempo. Alla parola «crisi», di cui non si fa che parlare per giustificare lo stato d’eccezione, noi restituiamo il suo significato originale di giudizio. Nel vocabolario della medicina ippocratica, krisis designava il momento in cui il medico deve giudicare se il paziente morirà o sopravviverà. Allo stesso modo noi discerniamo ciò che dell’occidente muore e ciò che è ancora vivo. E il giudizio sarà severo, non si lascerà sfuggire nulla.

Tuba mirum spargens sonum

per sepulchra regionum,

coget omnes ante thronum.

Mors stupebit et natura,

cum resurget creatura,

iudicanti responsura.

Una tromba che diffonde un suono meraviglioso

nei sepolcri di tutto il mondo,

chiamerà tutti davanti al trono.

La morte e la natura stupiranno,

quando la creatura risorgerà,

per rispondere al giudice.

Non possiamo far risorgere i morti, ma possiamo almeno preparare con ogni cura lo strumento meraviglioso del nostro pensiero e del nostro giudizio e, facendolo poi risuonare senza timore, liberare la natura e la morte dalle mani del potere che con esse ci governa. Sentire stupire in noi la natura e la morte, presagire qui e ora un’altra vita possibile e un’altra morte, è la sola resurrezione che c’interessa.

Liber scriptus proferetur,

in quo totum continetur,

unde mundus iudicetur.

Iudex ergo cum sedebit,

quidquid latet apparebit,

nil inultum remanebit.

Verrà aperto il libro,

nel quale tutto è contenuto,

e da quello il mondo sarà giudicato.

Non appena il giudice sarà seduto,

apparirà ciò che è nascosto,

nulla resterà invendicato.

Il libro scritto è la storia, che è sempre storia della menzogna e dell’ingiustizia. Della verità e della giustizia non vi è storia, ma apparizione istantanea nella krisis decisiva di ogni menzogna e ogni ingiustizia. In quel punto la menzogna non potrà più coprire la realtà. La giustizia e la verità manifestano infatti se stesse, manifestando la falsità e l’ingiustizia. E nulla sfuggirà alla forza alla loro vendetta, a condizione di restituire al questa parola il significato etimologico che ha nel processo romano, in cui il vindex è colui che vim dicit, che mostra al giudice la violenza che è stata fatta a colui che solo in questo senso egli “vendica”.

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus,

quem patronum rogaturus,

cum vix iustus sit securus.

E io che sono misero che dirò,

chi chiamerò in mia difesa,

se a mala pena il giusto è sicuro?

Il giusto che presta la sua voce al giudizio è in qualche modo coinvolto nel giudizio e non può chiamare altri in sua difesa. Nessuno può testimoniare per il testimone, egli è solo con la sua testimonianza -in questo senso non è sicuro, è dentro la crisi del suo tempo -e nondimeno pronuncia la sua testimonianza.

Confutatis maledictis,

flammis acribus addictis,

voca me cum benedictis…

Lacrimosa dies illa,

qua resurget ex favilla

iudicandus homo reus

Condannati i maledetti,

gettati nelle vive fiamme,

chiama me tra i benedetti…

Giorno di lacrime quel giorno,

quando risorgerà dalla cenere

l'uomo reo per essere giudicato.

Benché l’inno sul giorno dell’ira faccia parte di una messa che chiede pace e pietà per i morti, il discrimine fra i maledetti e i benedetti, fra i carnefici e le vittime è mantenuto. Nell’ultimo giorno, i carnefici, come stanno ora facendo senza forse avvedersene, si confutano infatti da soli, lasciano cadere le maschere che coprivano la loro ingiustizia e la loro menzogna e si gettano nelle fiamme che hanno essi stessi acceso. L’ultimo giorno, il giorno dell’ira, ogni giorno è per essi un giorno di lacrime, ed è forse proprio perché ne sono consapevoli che si fingono così sorridenti. Solo il consenso e la paura dei molti tiene in sospeso quel giorno. Per questo, anche se ci sappiamo senza potere di fronte al potere, tanto più implacabile deve essere il nostro giudizio, che non possiamo separare dal requiem che stiamo celebrando. Signore, non dare loro la pace, perché essi non sanno che cosa essa sia.

Giorgio Agamben, 11 luglio 2024

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

on pinterest, search [your name + core] and post 6 pictures and tag 6 people.

tagged by @m---e---l @uniquefartreview @ramm-ramm @vulnerant-omnes thanks all 🍀🍀🍀🍀

i did a little variation, 5 pics with my blogname and 5 with my real name 😊

blogname

(i sense pinterest has a specific search algorhythm 😊

real name

tagging... some people who recently reblogged stuff 😊 but ofcourse only if you feel like it, no pressure 🌺 @hikamarina @nyarisu @fyeahrammstein @anastilzchen-lindemann @entermyhcreativename @samshinechester

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

tag game: put your music library on shuffle, then list the first five songs that come up in a poll to let people vote for which one they like the most

Thank you for the tag @frampk ! =ටᆼට=)

Tagging @meinewellemeinstrand @samshinechester @marimayscarlett @m---e---l @vulnerant-omnes @helinyetille @naomullen @itconsumesyou @cursedbotwbird 💚

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wasn't tagged, but I remember that some years ago, something similar went around on Tumblr - and since this year comes to a close, I thought it would be fitting 😌 So welcome to the

Big mood 2023

Rules: Create a mood board for your 2023, using 9 pictures to reflect on the year. You don't have to elaborate or use any personal pictures (you can if you want) - you can create your board using pictures of your blorbos/screen caps/memes/aesthetics/etc. to show your vibes, thoughts, memories and moods throughout the year.

This year sure was... something. Hoping that the next one will be half as stressful (or even less) and will contain double the fun to make up for this one 🤞

No pressure tags for my lovely mutuals @wizzardclown @gothtoast @dandysnob @ms-nerd @gloomy-blonde @m---e---l @meinewellemeinstrand @samshinechester @morgana-lefay @keingesprach-allebeissen @musically--declined @vulnerant-omnes @namelessrammgirl @buuucky-barnes

#This year was the worst™ no need to repeat this#STORNO ich beende das Abo der letzten drei Jahre hiermit thanks#i have three wishes for next year: a good year for rammstein a good year for us fans and a fucking good year for my family#Because we all damn well deserve it#mood board#Mood board 2023#rammstein#friends tv#Aesthetic#Paulchard#Richard kruspe#Alice in wonderland#The office#Btw Schnuffels ihr wisst genau dass ihr mit dem kuchen repräsentiert seid 😌 ihr glaubt gar nicht wie ihr mir dieses jahr versüßt habt#Kussis an euch beide

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

🎃Halloween Spotify Random Game 🎃

Shuffle your “on repeat” playlist & then post the first 10 tracks, then tag people!

balah ih fogoh - vandal, djonga & baianasystem (i literally had already put this song in a different tag game not long ago, but i guess i just listen to it THAT MUCH, also it goes hard as fuck, also watch cangaço novo, also when djonga said "essa festa tem preta com a bunda no chão e a alta estima lá no teto"? i felt that)

sulamericano - baianasystem (HELP another song i just put on that tag game 💀💀💀💀 [hearing this song live has kinda ruined life for me tho, nothing will ever compare])

twice your size - declan mckenna (finally smth different)

..... bola de cristal - baianasystem .....

never taking me alive - miles kane

sympathy - declan mckenna

yo viviré (i will survive) - celia cruz

call me - blondie

crackerbox palace - george harrison

cabeça de papel - baianasystem

half this list is repeats from the other tag game, but it is what it is, skipping them felt like cheating idk, also i just felt like tagging some people (no pressure to do the thing tho, as per uszh)

@angels-a-goth-kid @punk-ravioli @young-aspiring @bennygesserit @extra-omnes @gael-garcia @skylarbee @perfectly-clear-from-here @kinghazycrazies @onlyformywriting

oh yeah and thanks @andithil for tagging me 😁

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi. Could you provide the sources for your statement? I'd like to read them.

Yeah, I can do that.

Basically, the first known instance of the name Baphomet was in 1098, in a letter written by a French Crusader named Anselm of Ribemont detailing the siege of Antioch, Turkey (nowadays known as Antakya).

The relevant section (page 475 if the link doesn't work properly) reads "Sequenti die aurora apparente, altis vocibus Baphometh invocaverunt; et nos Deum nostrum in cordibus nostris deprecantes, impetum facientes in eos, de muris civitatis omnes expulimus." ("As the next day dawned, they [i.e. the inhabitants of Antioch] called loudly upon Baphometh; and we prayed silently in our hearts to God, then we attacked and forced all of them outside the city walls.")

Raymond of Aguilers, a man who chronicled the First Crusade, claims that troubadours (Medieval French lyrical poets) used the term "Bafomet" to refer to the Islamic prophet Muhammad (footnote of page 497 if the link doesn't work properly). This is corroborated by the early 12th-Century lyrical poem Senhors, per los nostres peccatz (Gentlemen, it is because of our sins) by the troubadour Gavaudan, which repeatedly localizes "Muhammad" as "Bafometz", the most obvious being the closing stanza:

"Profeta sera.n Gavaudas qu.el dig er faitz, e mortz als cas! e Dieus er honratz e servitz on Bafometz era grazitz." ("Gavaudan shall be a prophet for his words shall become a fact. Death to those dogs! God shall be honoured and worshipped where Muhammad is now served.") (It's worth noting that Medieval Christians thought Muslims were idolatrous, and worshipped Muhammad as a god, which is obviously not true.)

As for the latter claim, a lot of Templars were arrested under the rule of King Phillip IV of France, who suppressed the order via charges of heresy, spitting on crosses, idolatry, and sodomy, among other things (page 71 if the link doesn't work properly). Many Templars were tortured into confessing, claiming that they worshipped a deity named Baphomet, who they described as resembling either a three-faced head or a cat (note the lack of goats). Of course, these charges are of dubious validity, especially considering the forced confessions, but that's not important.

Fast forward to to the mid-1850s, and Éliphas Lévi publishes a two-volume occult treatise known as Dogme et Rituel de la Haute Magie(Dogma and Ritual of High Magic). The second volume's frontispiece (and even the cover of various republished versions) depicts an androgynous goat-headed entity that Lévi identifies as Baphomet (also known as the Sabbatic Goat). This depiction of Baphomet is clearly inspired by (or at least, uncannily resembles) The Devil, the fifteenth Major Arcana card found in tarot decks (which in turn is based on various depictions of Satan in Medieval artwork).

So yeah, to quote the meme, that word isn't in the Bible (though it is technically in the Quran).

Hope this helps ^_^

4 notes

·

View notes