#Dusty Mancinelli

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Violation directed by Dusty Mancinelli and Madeleine Sims-Fewer

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Violation (2020)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

now presenting Kristenswig’s Most Anticipated Major Motion Pictures of 2025

Jupiter (Andrey Zvyangintsev)

Sentimental Value (Joachim Trier)

Miroirs No. 3 (Christian Petzold)

Die, My Love (Lynne Ramsay)

The Secret Agent (Kleber Mendonca Filho)

Butterfly Jam (Kantemir Balagov) (idgaf)

On Land and Sea (Hlynur Palmason)

Alpha (Julia Ducournau)

Untitled (Kathryn Bigelow)

The Mastermind (Kelly Reichardt)

A Big Bold Beautiful Journey (Kogonada)

Orphan (Laszlo Nemes)

Private Life (Rebecca Zlotowski)

The History of Sound (Oliver Hermanus)

Resurrection (Bi Gan)

Rebuilding (Max Walker-Silverman)

After the Hunt (Luca Guadagnino)

M3GAN 2.0 (Gerard Johnstone)

Honey Bunch (Madeline Sims-Fewer & Dusty Mancinelli)

The Bride (Maggie Gyllenhaal)

Rose of Nevada (Mark Jenkin)

The Ice Tower (Lucile Hadzihalilovic)

Dreams (Michel Franco)

Drop (Christopher Landon)

Hope (Na Hong-jin)

The Perfumed H-[gunshots]

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

“You've created a reality that is completely different from everyone else's, where you're the saint who gets tricked into doing bad things."

Violation (Madeleine Sims-Fewer & Dusty Mancinelli, 2020)

#my reivew - a lot of cool/interesting things in this one#i think it could've been tighter in a few places plotwise but also i very much enjoyed it :)#madeleine sims-fewer#dusty mancinelli#anna maguire#violation#violationedit#violation 2020#horroredit#filmedit#notes from the chills#horror in film

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Violation will be released on Blu-ray and Digital on September 21 via RLJE Films. The 2020 Canadian horror-revenge film is streaming exclusively on Shudder.

Dusty Mancinelli and Madeleine Sims-Fewer write and direct, marking their feature debut. Sims-Fewer also stars with Anna Maguire, Jesse LaVercombe, Obi Abili, Jasmin Geljo, and Cynthia Ashperger.

Extras are listed below, where you can also watch the trailer.

Special features:

Meet the Filmmakers

Toronto International Film Festival Introduction

youtube

With her marriage about to implode, Miriam returns to her hometown to seek solace in the comfort of her younger sister and brother-in-law. But one evening a tiny slip in judgement leads to a catastrophic betrayal, leaving Miriam shocked, reeling, and furious. Believing her only recourse is to exact revenge Miriam takes extreme action, but the price of retribution is high, and she is not prepared for the toll it takes as she begins to emotionally and psychologically unravel.

Pre-order Violation from Amazon.

#violation#shudder#horror#revenge film#revenge movie#horror movies#horror film#rlje films#dvd#gift#madeleine sims-fewer#dusty mancinelli#anna maguire#canadian film#canadian horror

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE PERMANENT RAIN PRESS INTERVIEW WITH MADELEINE SIMS-FEWER AND DUSTY MANCINELLI

Violation is one of the most stirring films we’ve seen over the past year. Since making its world premiere at Toronto International Film Festival last year, the Canadian flick has been busy on the film festival circuit; now available through digital-cinema on TIFF Bell Lightbox, with Vancouver International Film Festival (VIFF) Connect to follow beginning March 26th.

What inspired the story behind Violation?

We were both dealing with our own personal experiences of trauma at the time, and wanted to make an anti-revenge film that deals with female rage, and emotional and psychological unravelling that trauma gives rise to.

We really wanted to make a revenge film that pushed the boundaries of the genre, challenging the tropes of the scantily clad woman becoming empowered by violent revenge against a menacing stranger, and that revenge is the cathartic climax we are all seeking at the end of the movie. Yes, it is a film about seeking retribution, but also about the cost of that retribution. It is a film about violation, but also about lack of empathy and selfishness, and how both can erode your morality and the relationships around you.

It’s been described as “twisted,” “feminist-minded,” and a “hypnotic horror.” At its core, how would you describe the film’s genre(s)?

Those three descriptors fit perfectly, actually! We weren’t thinking too much about genre when we wrote the script, mostly about the story and about how we portrayed Miriam’s journey. We were inspired by films that don’t sit comfortably in a genre box, like Caché, Fat Girl, Don’t Look Now. Films that are dramas with elements of horror.

When you were writing the script, can you elaborate on the dynamics between the two couples that you wanted to portray – Miriam and Caleb, and Greta and Dylan?

Miriam and Caleb are very much at an impasse in their relationship. The spark has gone out and they don’t know how to reignite it. Instead of doing the work it might take to get through a rough patch Miriam is very much running away. There is a real transience to modern relationships that we wanted to capture in their dynamic - this idea that when the romance is gone the relationship has run its course. Miriam wants to fix it, but doesn’t know how - she clumsily tries to fix it with sex (on her sister’s advice), and this echoes how she tries to fix her trauma too.

Greta and Dylan have a seemingly healthy relationship. But when you look a little deeper their outward affection and codependence masks a deep distrust. Dylan is having his ‘grass is greener’ moment, and he’s totally selfish to the impact this has on those around him. Greta can sense this, but she’s too enamoured by him to risk rocking the boat. It’s all a recipe for tragedy really.

Miriam and Greta have a complex relationship, to say the least. It’s natural to have distance between siblings as they grow older, did you always intend to have a sibling relationship be a centre of your story?

Yes, we always wanted to make a film about a person who suffers sexual assault and is not believed by their sibling. That was one of the first parts of the story that came together. There is so much to unpack in a sibling relationship like theirs. A rich history of mutual failures and resentments as well as so much camaraderie and love. The more painful betrayal in the story comes from Greta, not Dylan.

We wanted to explore the idea of trauma within families, and how abuse and violence affects everyone in the family, not just the person who suffers it. Everything else orbits around these two sisters — Miriam and Greta — as Violation mines the little resentments, commonalities, shared joys and sorrows that weave together a truthful portrait of these women.

A lot of the horror and dread in Violation comes from the way the sisters interact, and in the ways they react to each other from a place of fear. There is no filter in these close sibling relationships (we know this as we both come from big families!) which can be wonderful, but can also lead you to hurt and be hurt in ways that leave permanent emotional scars.

The non-linear editing engages viewers into the story, as do the jarring intercuts with imagery of nature, animals and insects. Tell us about the editing and post-production phase, and what you hoped to accomplish with the progression and symbolism.

The way we have edited Violation is very deliberate. We are forcing you to experience things you might not want to in a very specific way, guiding you through this post traumatic landscape where the past and present are constantly speaking to each other.

We chose to weave two timelines together — the 48 hours leading up to the betrayal and the 48 hours surrounding the act of revenge. This forces the audience to re-contextualize what they have seen, challenging their own opinions of the characters based on what information we choose to reveal and when.

Violation is told completely from Miriam’s perspective — we watch her emotional and psychological unravelling as she struggles desperately to do the right thing. There is a sequence in the middle of the film where we see this act of revenge. There is no dialogue for a long time, we just follow Miriam as she goes through these meticulous actions. And what we realize is that her plan, though well thought-out, is unbelievably emotionally and physically taxing. She’s not prepared, and we watch the real horror of her actions play out through her visceral emotional responses. It was important for us to really force the audience to experience things as Miriam does. The editing is focused and relentless; never letting you stray from her experiences and emotions.

Madeleine, for you, getting to play Miriam and connect with her pain and turbulent emotions through the course of the film, can you share your thoughts on that experience. How did committing to this character challenge you as an actor?

It was the most challenging role I have ever played, and in many ways was absolutely terrifying. I wanted to push myself as far as I could go as an actor and challenge myself to really find the truth of who this woman is, and reveal that to the audience. There are so many quiet moments where Miriam’s journey is so internal, so the challenge there was in truly living each moment as if I was her — getting lost in the role — so that I was not indicating what she was feeling, but living it.

What was it like having Anna, Jesse and Obi as screen partners?

Very liberating. They are all extremely dedicated, layered, engaging performers. They elevated me and challenged me every step of the way. Jesse and I have worked together before, and we have an ease that makes scenes with him very fun. The comfort level we share allows us to really experiment. It was my first time working with Anna and Obi, but it won’t be the last. They are both so open and sensitive that I felt our work was incredibly nuanced.

An overarching question is whether revenge is ever justified. Tell me about Miriam’s mindset, and the struggle between morals, motives and her actions. For you as individuals, is this something that you have had conflict with in your own lives?

In a way we wanted to make a sort of revenge fairy-tale. Fairy tales provide ways for children to think through moral problems, and to wrestle with life’s complexities. They aren’t depictions of reality, but reflect ideas about morality and humanity. We wanted the audience to think about consent, the rippling effects of trauma, how we judge women vs how we judge men, and perhaps consider those things more deeply.

In the end Miriam’s desire to punish those who have wronged her hopefully leaves the audience with a compelling ambiguity to be unpacked as they scrutinize her actions.

Tell us about the trust built between the cast and crew on-set, especially during the more intimate and grim scenes and tense conversations. How do you build that comfort level?

It’s really just about having open, honest conversations. We spent a lot of time with the actors during prep and rehearsals just talking, and building friendships. We are dedicated to creating a comfort level where actors can be completely transparent and open with us, so that when we ask them to go somewhere they know we are there guiding the process and aren’t afraid to take big risks.

To survivors of trauma, what do you hope this movie provides in its story?

We hope to provide a new take on the revenge genre - one that explores rape from a different angle and context - with the focus of the narrative much more on the psychological ramifications of trauma. We aren’t looking to tell anyone what to take away from the film, and we made Violation as much for people with no experience with trauma as for people who understand these murky waters. Really we hope the film sparks thought, discussion, and empathy.

You met at the 2015 TIFF Talent Lab; what drew you together as a filmmaking team? What advice do you have for artists/filmmakers looking for their own collaborators?

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what drew us together - it’s sort of an intangible thing. We developed a very candid friendship that we thought might translate well to a working relationship. Luckily it did!

Shortly after the Talent Lab we decided to work together on two short films, Slap Happy and Woman in Stall. Until directing these shorts neither of us had really had ‘fun ’making a film. Filmmaking was a drive, but it wasn’t a joy. These shorts gave us a totally new perspective, where we actually had a good time workshopping the script, creating a visual style, and just challenging each other. By the time we were making our third short, Chubby, we had decided to officially form a creative partnership.

We definitely approach filmmaking from different perspectives and with complementary strengths, but we don’t say ‘this is your thing and this is mine.’ We work collaboratively on every part of the process, and we built this unique way of working through our shorts, so that when we got the funding to make Violation (through Telefilm’s Talent to Watch program) we already had a solid method that works for us.

In terms of advice it really helps to know how you like to work before looking for a collaborator. Then it’s just about experimenting. It is very much trial and error. Don’t try to force a collaboration that isn’t working for you. There is no shame in a creative relationship not working out. But also it is important to be flexible and open to compromise - that’s how ideas flourish and grow. If you are too rigid then maybe collaboration is not right for you.

Going from short films to your debut feature with Violation, what new challenges did you face and how did you overcome them?

The endurance required to make a feature was something we weren’t prepared for. At about day 3 we turned to each other, totally exhausted, and were like: “there’s 30 more days of this.” It was brutally draining. Honestly every day brought its own unique challenges and problems to overcome, but we had such a strong, supportive team that it made each mountain a little easier to climb.

Aside from yourselves, who are some other up and coming Canadian filmmakers viewers should keep their eyes on?

Grace Glowicki and Ben Petrie are both doing really interesting work. Grace’s film Tito is a disturbingly good character study that builds a terrifying sense of dread. Ben’s short Her Friend Adam is one of our favourites, and he’s about to make his first feature.

Is there anything further you’d like to add or share, perhaps what you are currently working on?

Right now we are writing a slow burning mystery thriller and a twisted dark comedy. That’s about all we can reveal at the moment!

Thank you to Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli for providing us with further insight into Violation! Visit their official website for more information on their projects.

#entertainment#Interview#feature#Violation#Madeleine Sims-Fewer#Dusty Mancinelli#Movie#film#Canadian Film#horror movie#thriller movie#VIFF#GAT PR#Canadian Movie#Jesse LaVercombe#Anna Maguire#Obi Abili#Pacific Northwest Pictures#TIFF#Toronto International Film Festival#TIFF Talent Lab

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Violation (2020) Dusty Mancinelli, Madeleine Sims-Fewer.

0 notes

Text

Victoria Film Fest Interview: Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli on their film 'Violation'

Victoria Film Fest Interview: Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli on their film 'Violation' @VicFilmFestival #VicFilmFestival #VFF21 @@DustyMancinelli

Violation is the first feature film by Canadian filmmakers Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli. A take on the rape-revenge genre, it is a tense and uncomfortable film, but in the best way possible. I had the distinct pleasure of sitting down with the pair via Zoom during the Victoria Film Festival. Continue reading

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Violation directed by Dusty Mancinelli and Madeleine Sims-Fewer

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Violation (dirs. Madeleine Sims-Fewer & Dusty Mancinelli) x VIFF 2020.

This cabin in the woods rape-revenge thriller is a nasty, divisive piece of work. Unflinching in its deliberately constructed reversal of the male gaze, the co-directors revel in twisting horror conventions by expressing the brutally of sexual violence and assault from a familiar source.

It’s more than a provocative reversal of archetypical gender roles in genre cinema told through the explicit imagery yet its depictions are just as disturbing. Words can only partially describe how truly nasty and twisted the material really is regardless of how smart or clever it’s often executed. All said, Violation really does commit to showing us the full cost of its revenge fantasy narrative for better and worse.

Screened virtually at the 2020 Vancouver International Film Festival online as part of the Altered States stream.

#reviews#violation#violation movie#violation film#movie#movies#movie review#features#film#film review#viff#viff 2020#indie film#indie movie#canadian film#cinema#tiff 2020#tiff#madeline sims-fewer#dusty mancinelli#madeline sims fewer#horror#revenge

0 notes

Photo

Best Horror Films of 2021

The Night House (David Bruckner)

Saint Maud (Rose Glass)

Titane (Julia Ducournau)

Malignant (James Wan)

Coming Home in the Dark (James Ashcroft)

The Feast (Lee Haven Jones)

Sator (Jordan Graham)

Censor (Prano Bailey-Bond)

Oxygen (Alexandre Aja)

Violation (Madeleine Sims-Fewer & Dusty Mancinelli)

#the night house#saint maud#titane#malignant#coming home in the dark#the feast#sator#censor#oxygen#violation#awards 2021#horror

270 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My Top Films of 2021:

Pandemic disruptions made for slim pickings this year, but these were the movies that made an impact on me. (If you want a list of the all-around best entertainment of 2021, TV was where it’s at.)

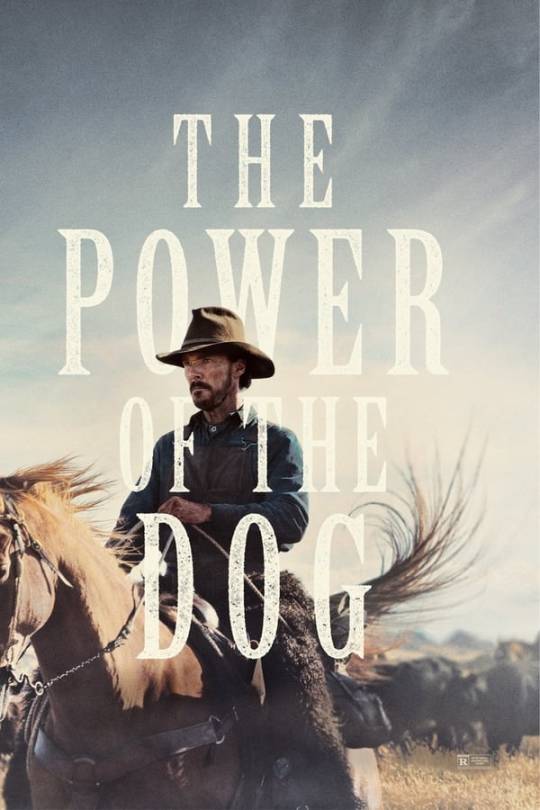

The Power of the Dog (2021) dir. Jane Campion

Together Together (2021) dir. Nicole Beckwith

The Green Knight (2021) dir. David Lowry

Passing (2021) dir. Rebecca Hall

Violation (2020) dir. Madeleine Sims-Fewer & Dusty Mancinelli

Black Widow (2021) dir. Cate Shortland

Dune (2021) dir. Denis Villeneuve

The Electrical Life of Louis Wain (2021) dir. Will Sharpe

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021) dir. Destin Daniel Cretton

Kate (2021) dir. Cedric Nicolas-Troyan

Honorable mention: Zack Snyder’s Justice League – Ok, is it a *good* movie? Not really, but it is 100x better than the original and very enjoyable for Wonder Woman fans. And if you had the misfortune of seeing the Wh*don cut, you understand why this gets a mention for simply existing, to retcon that piece of racist/misogynist trash from the DCEU.

#year end lists#movies#2021#the power of the dog#together together#the green knight#passing#violation#black widow#dune#the electrical life of louis wain#shang-chi and the legend of the ten rings#kate#zack snyder's justice league#orig

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watch The Intense Trailer For Feminist Revenge Horror Violation

Watch The Intense Trailer For Feminist Revenge Horror Violation

Shudder have released the Official Trailer for their feminist revenge horror Violation, due for releasing on the channel next month. The bold and unflinching thriller is feature debut for Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli. The film made it’s world premiere at last years Toronto Film Festival which saw the film win the audience along with critical appraise. The film played Sundance…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Sum More Summaries

There were so many incredible films I saw at the Sundance Film Festival after my last review.

During the second half of the Sundance Film Festival I saw the following:

R#J *****

Coming Home in the Dark *****

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair ****

First Date ****

The World to Come *****

Violation *****

Marvelous and the Black Hole *****

The Blazing World *****

Mayday *****

Night of the Kings ****

Life in a Day 2020 *****

Flee *****

Coming Home in the Dark by James Ashcroft was a massive suckerpunch. Within the first ten minutes, the horror begins and rings through your bones for the entirety of the film. The light continually becomes lesser and starts to go from very crisp to murky visually. For the majority of the film, you ride with two parents forcefully being driven in their own car by a vengeful pair of ex convicts. Bad things (worse than being held captive) happen, but throughout there is an overhanging sense of dread of what will happen next. I quite enjoyed this film and found the quiet ending to be somewhat perfect in it’s subtlety. There were a few moments I was uncertain with, like one of the men's seemingly ritualistic practices which was never explained, but I feel like this leaves it with some ambiguity which I don’t mind; I enjoyed having to ponder it a bit. This film really took my by surprise.

We’re All Going to the World’s Fair by Jane Schoewbrun was very strange and somewhat amateur, but in a way which gave it a certain… creepy charm? It’s a movie which you shouldn’t judge too harshly throughout or immediately after. Let it sit with you for a moment. It is a fantastic portrayal in some ways of loneliness and desperation, as the main character engages in a strange online role play game which is supposed to cause one to act strangely over time.. But is it this game or is it a placebo effect? This movie leaves you uncomfortable with it’s drawn out scenes and overarching feeling of being alone through scenes in her attic bedroom in front of the glow of the computer screen. It’s not what I expected going into it, but the concept holds valid feelings which it explores and shows in disconcerting ways.

Violation by Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli was... Well… I don’t know where to begin with this one. “Wow” should do it. The symbols and motifs were stunning to start with, predator and prey seeming to be the most notable one with the spider and fly and the wolf and rabbit (which could have gone cliche, but didn’t). This story has a somewhat mind bending quality in form (reminiscent of Christopher Nolan’s film Memento) and plays through the indulgently graphic sequence of events which leads to the end. She sits on the steps, observing everyone at a family gathering as they eat ice cream she made (which may not be your run of the mill vanilla… I don’t want to give away too much) including her sister...

The Blazing World by Carlsen Young was like walking into a colourful candy store where each treat is trauma and horror ridden. This film to me had a subtle essence of Alice in Wonderland, and the music video for the song “Black Hole Sun” by Soundgarden (though clearly very different in storyline) as she walks through a half conscious realm searching to bring her sister back to life. She must conquer her traumatic memories (and give some away) to finally come to terms with what is. This was Young’s first feature film and was based off a short film she made which was part of the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.

Mayday by Karen Cinorre was a little bit lost boys of Neverland meets Lord of the Flies, only with women. A young woman after a traumatic experience at work, falls into another dimension through an oven after flipping a faulty switch during a power outage. She resurfaces through the water into a war ridden land made up of rocky coast and dominating young female soldiers who siren in men, sending them to their death. This is a brilliant story of the war on women, engrained trauma & feminism, coupled with dark synthy music and a spontaneous Liberace backed dance sequence.

These are only a few of the final half I saw, but they were all very fresh and entertaining in their variety.

Mae McCloskey

1 note

·

View note

Text

Victoria Film Fest Review: 'Violation' is a tense, uncomfortable twist on the rape-revenge genre

Victoria Film Fest Review: 'Violation' is a tense, uncomfortable twist on the rape-revenge genre @VicFilmFestival #VicFilmFestival #VFF21 @dustymancinelli

There are few things that one person can do to another that is more violating than rape. It is an act of power, an act of selfishness, and an act of degradation. Violation is a film about such an act—a moment when a man sees a woman and takes what he wants. The result is a visceral and uncomfortable watch that sees a woman go to extremes to take her revenge. Continue reading

View On WordPress

#Anna Maguire#Dusty Mancinelli#Jesse LaVercombe#Madeleine Sims-Fewer#Obi Abili#VFF 2021#Victoria Film Festival#Violation

0 notes