#Derrida

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"A poem always runs the risk of being meaningless, and would be nothing without this risk of being meaningless, and would be nothing without this risk."

- Jacques Derrida, 'Writing and Difference'

#poetry#poems#risk#meaningless#nothing without risk#nothing ventured nothing gained#nothing#Jacques Derrida#Derrida#modernism#postmodernism

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

930 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Incessantly, what a word.”

—Derrida

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

ever since I was a little girl I knew I wanted to embrace the instability and multiplicity of signifiers and their signifieds

23 notes

·

View notes

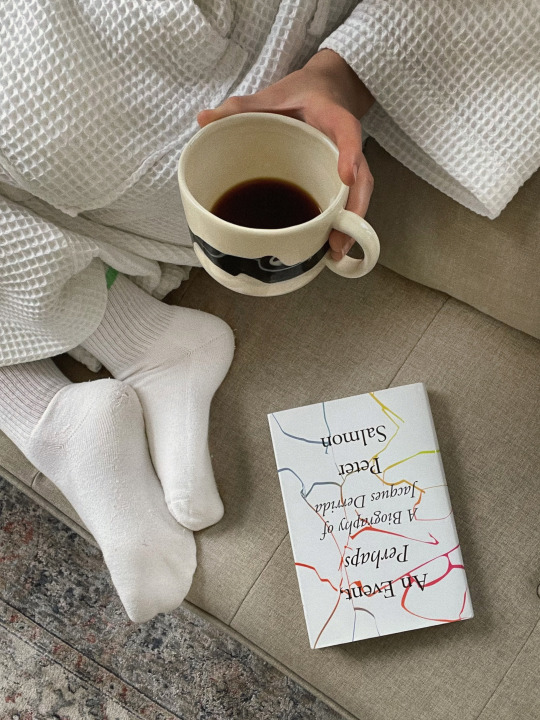

Photo

Lazy start to a rainy Sunday morning. Last night was games night with some friends, we stayed up till the early hours so we're still wearing sleepiness. Outside, the marathon has closed all the streets surrounding our flat and crowds have gathered to cheer on athletes, friends, loved ones. All a perfect excuse to open all the windows, have one more cup of coffee and do a little reading

#studyblr#studygram#studyspo#books#bookblr#booklr#reading#currently reading#read#jacques derrida#derrida#philosophy#literature#litblr#lit#sunday#weekend#london

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The wound can have (should only have) one proper name. I recognize that I love—you—by this: you leave in me a wound that I do not want to replace.” —Jacques Derrida.

6 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Derrida suggests that a religion comes into being when the experience of responsibility extracts itself from some interplay of the animal, the human, and the divine. (That is to say, the wings of the angels and the horns, hooves, and tail of the devil may just have a good deal more to do with marking Christianity as a religion than do the wounds of Christ.) Without the extraction or the divine, however, what is produced is the monstrous. The monstrous thus may just be a presupposition for the religious.

Samuel R. Delany, "The Thomas L. Long Interview"

#language#symbols#myths#mythology#monsters#religion#Derrida#quotes#Delany#Samuel R. Delany#The Thomas L. Long Interview

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

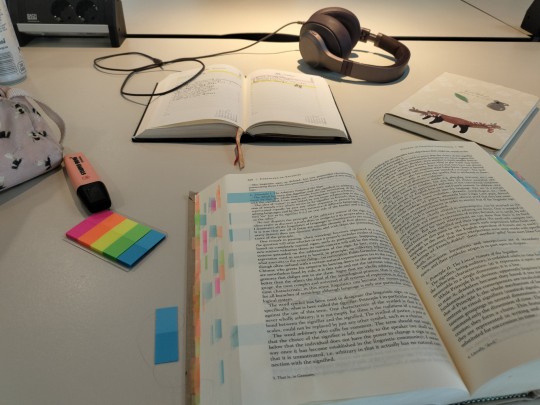

The last few days I have shifted over to a study of language and deconstruction, I have finally finished my readings of Derrida as well. From there I moved to postcolonial theory, which is one of my huge special interests.

If anyone would be interested in talking about literary theory, feel free to contact me!

#studyblr#study notes#dark academia#latin student#study tips#studying#studyspo#comparative literature#literary history#university studyspo#autistic#actually autistic#actually adhd#actually audhd#audhd studyblr#derrida#foucault#franz fanon#gilles deleuze#comparative lit student#university student#uniblr#university#student life#study motivation#study space#study hard#summer study

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

spending most of my time in the library designing the cover instead of actually doing the presentation? It's more likely than you think...

#literature#margaret atwood#jacques derrida#derrida#philosophy memes#women's literature#literature memes#handmaid's tale#gradblr#stu(dying)#history#history memes#archive

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Should one save oneself by abstraction or save oneself from abstraction? Where is salvation, safety?"

- Jacques Derrida, 'Faith and Knowledge: The Two Sources of 'Religion' At the Limits of Reason Alone

#abstraction#knowledge#faith#reason#limits#certainty#being#source#spirit#spirituality#mysticism#revelation#jacques derrida#derrida#modernism#postmodernism

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Insofar as we always live with presence and non-presence, [Derrida] suggests, there are spirits. We see this clearly in fiction: all stories are ghost stories, in which reading invokes a return to the present of specters — say, a dead writer, or an idea from the past. Derrida, for his part, focused on the examples of Marx's 'specter of communism' and Shakespeare's principal tragedy. Tenses are muddled; 'The time is out of joint,' says Hamlet. These hauntings occupy an ambiguous ontology between life and death, presence and absence. 'They are always there, specters, even if they do not exist, even if they are no longer, even if they are not yet,' Derrida wrote. 'Haunting is the state of proper being as such.'

Though 'to be or not to be' remains Hamlet's most quoted phrase, in the play's broader context, life or death is not the question at all. The dichotomy is undone from the beginning. For the play begins with a ghost, the king who is and is not — both gone and present, both rightful king and no-longer king. Hamlet fails to understand the hauntological universe in which he lives, where 'to be or not to be' fails to exhaust the logical space.

I like the thought, but Derrida's intervention in ideological totality seems to posit an ossified world of haunting itself. It reminds me of Henrik Ibsen's play Ghosts, and his tormented Mrs. Alving, who says,

I am half inclined to think we are all ghosts... It is not only what we have inherited from our fathers and mothers that exists again in us, but all sorts of old dead ideas and all kinds of old dead beliefs and things of that kind. They are not actually alive in us; but there they are dormant all the same, and we can never be rid of them.

For Derrida, the possibility of something dead-and-alive, so neither dead nor alive, ruptures notions of a world ordered into presence and absence. We would do well, unlike Hamlet, to notice it."

- Natasha Lennard, from Being Numerous: Essays on Non-Fascist Life, 2019.

#natasha lennard#quote#quotations#nondualism#ghost stories#hauntology#derrida#shakespeare#hamlet#storytelling#fiction#ontology

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jino-chan times~

#戦国TURB#sengoku turb#fanart#jino-chan#molina#hitsuji#KG#nietzsche#kuma#usagi#gertrude#failure#bombo#gelsomina#soldier#nanoray#derrida#patra#doppa#alice b#blowout#sonorous face#tur#all these hashtags i went insane

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

in the club googling Of Grammatology 1967 full text pdf download

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I made a post earlier talking about how bashing fics are the result of the disconnect between the level of suspension of disbelief expected from an author vs from their immature audience.

Most authors expect a level of shared disbelief. "People will get this is just some handwave-y nonsense for the story. They will suspend their disbelief." They do not realize that kids won't know this automatically. Kids don't need to 'suspend their disbelief' because they will simply believe the nonsense.

And then the kiddos grow up and feel betrayed because they realize that they've thought about this way more than the author ever did.

But what if the authors DID think about it? What if they planned for that? What if they realized that the preteen to young adult demographic is PRIMED for this kind of relationship to their media?

Introducing the DECONSTRUCTION (and Madoka Magica)

Now, this term is a bit controversial. It's a mode of analysis that, from what I can tell, exclusively comes from the Anime Analysis/Tv Tropes side of the internet, and nowhere else.

Because of those hazy origins, it's a little hazy what it even means. When I use it, I mean it's a media that subverts tropes by applying a lens of realism to it, specifically to "expose" the shocking truth behind a functioning cliche/genre. Usually in reference to genre fiction like superhero shows, mecha shows, fantasy shows, etc.

It became a coined term with its application to Neon Genesis Evangelion, but people would be more familiar with it for shows like Game of Thrones or Watchmen or Madoka Magica.

You think this is just your average high fantasy? THINK AGAIN! The main character DIES because that's REAL life in the hard medieval dark ages.

You think this is just your average superhero comic? THINK AGAIN! These superheroes use their powers for selfish reasons instead of selfless ones because THAT'S MORE REAL.

You think this is just your average show about sparkly girls fighting monsters? THINK AGAIN! These girls have been conned into their supernatural powers and fighting is dangerous and depressing because THAT'S MORE REAL. GRIMDARK is MORE REAL.

Now this can be mundane realism ala Vermeer, or the grimdark realism you see with all those Watchman superhero comic knock-offs in the 90's or all those Madoka Magica magical girl knock-offs or all those Game Of Thrones knock-offs in the late aughts. Choose any realism you like because Realism is subjective!

check out here for a breakdown of why "grimdark" does not make "realistic" and here for why realism is subjective/unnecessary for writing. I'm not going to be getting into that here.

HATING the term """DECONSTRUCTION"""

Now, opponents of the term DECONSTRUCTION point to this very subjectivity as the reason why it's functionally meaningless as a term.

"Madoka Magica isn't 'more realistic' compared to other magical girl shows. Other magical girl shows like Princess Tutu show ALSO portray depressing, deep, and dangerous situations happening to magical girls. How is what Madoka does any more 'realistic' than what Tutu does, especially when both of them ultimately reaffirm the Magical Girl Genre?"

I think this, at its core, misunderstands why people call something a deconstruction. This is an understandable mistake because the anime people who coined the term didn't even understand why they felt the need to call something a deconstruction.

The original term Deconstruction analysis, from before the anime/TV Tropes side of the internet appropriated it, comes from philosopher Jacques Derrida. Derrida, in simplified terms, explained the infinite gap between thought and communicating that thought. The infinite gap between concepts and the language trying to describe those concepts.

So it's pretty ironic the way we've completely butchered his term into this anime "genre deconstruction" mode of analysis and then completely butchered this "genre deconstruction" mode of analysis into "making something more realistic."

But while this "genre deconstruction" is not real deconstruction, I'm going to analyze it on its own terms anyways because I do find it meaningful, if not the way we define it now.

In my opinion, deconstruction has nothing to do with "realism" and everything to do with the "exposing the shocking truth behind a functioning cliche" part of its definition. It doesn't matter if Princess Tutu is 'realistic' because it doesn't portray itself as 'in conversation with' the magical girl genre.

CLICHE and the Generation Cycle of Growing Up

You ever notice how deconstruction's most famous examples are from genres made for adolescents? Magical Girls, High Fantasy, Superheroes. Hmmm?

That has everything to do with the way the cycles of cliches work. Overly Sarcastic Productions has some really great videos breaking down how writing is all about tropes.

And how there's a cycle where a trope begins FRESH AND EXCITING where authors all remix each other. Then all the good stuff gets said a million times until the trope becomes a shorthand for a specific function. Then people get sick and tired of it and actively fight against its usage.

This often also coincides with the generation that was young when the trope was popular growing up and looking back on the trope.

Ex: You love Disney Romances as a kid, grow up and realize no prince is coming to get you, and get tired of "love at first sight" stories because the love often feels like a shorthand plot device instead of genuine romance, leading to parodies and then a new generation of Disney movies with no romance at all.

Ex: The cowboy Western Genre has gone through this. Multiple times now. First with traditional westerns that are now dead. Then with Space Westerns in Japanese animation. Also dead, though we do get reboots from time to time.

Ex: Joss Whedon/Marvel Humor.

Ex: The isekai/transmigration genre is currently going through this. The West has no conception of transmigration and barely any understanding of isekai—likening them to portal fantasy with nary a thought to how its become its own niche genre. But it IS a niche genre now, resplendent with bizarrely specific tropes and cliches that have a functional logic underneath inscrutable to new viewers.

I watched a C-Drama recently where they didn't even bother to explain transmigration beyond a shot of a girl's ghost hovering another girl's sleeping body. And like, if I was a Westerner, I would have NO CLUE what that was supposed to mean.

Of course, as a Scum Villain fan, I know that it was a visual shorthand meant to imply Transmigration, where the girl was transported into another dimension via the body of another girl, but this implication is reliant on the understanding that you've already seen this trope a thousand times now.

("We don't need to show this again, you get the drill." NO, we don't! Not here in the West. Please explain. At this rate, we'll be getting to parodies of transmigration and then no transmigration at all—all before the West even gets a whiff of what "transmigration" means. Beyond like, niche anime/webtoon fans.)

The point is, you get to a point where you don't even notice how terminally cliche your genre has gotten unless you get confronted by someone out of the loop. And that acts as a neat metaphor for the way childhood works.

A lot of the "truths" of the world, like that 'adults are to be trusted' or that stories are 'simple retellings of events,' are actually just thought-terminating cliches you've been taught as a shorthand to make things simpler to understand/easier to control.

That's why adolescent media, rather than say speculative Sci-Fi for philosophical thought experiments or literary fiction, is at the core of "deconstruction genre analysis."

This ""form of analysis"" is just the result of artists noticing the happy intersection between the form/function of adolescence and adolescent media, making for the perfect metaphor. A marriage of literary convention and human psychology. "Medium is the message"? Make it "Genre is the message."

As such, actual realism is secondary to the the psychological aspect of "breaking down a thought terminating cliche."

Madoka Magica is not more realistic than Princess Tutu.

IT DOES, however, directly reference the magical girl genre as we know it within the show itself. Madoka, the main character, draws sparkly magical girl outfits in her notebook and imagines her Magical GirlTM hair styles when she finds out that she can become a magical girl. These are not just magical girls to her—these are Magical GirlsTM. She's as familiar with the cliches of the genre as we are.

This is in service to highlighting that we're meant to be engaging with the idea of the genre itself, not just the themes of selflessness and depression within it. Madoka Magica also has a lot of Brechtian techniques within the framing of the show, with the series' first shot even beginning with literally "opening the curtains" to break the fourth wall a little bit, highlighting that it's a bit self-aware/meta. That way, we can see the intentional "wider commentary on the genre" aspect to it.

(Like the way Spider-verse uses "canon event" and the multiverse as a clear reference to extended audience canon culture to signal that it's making a meta commentary on the wider discussion of Miles Morales and the extended universe, not just his personal struggles as a character.)

So, Princess Tutu is NOT less realistic or less depressing than Madoka Magica. In fact, it even "deconstructs" fairytale cliches. It isn't a Magical Girl genre deconstruction as we think of it, though, because it isn't making those overt commentaries on the Magical Girl Genre thought-terminating cliches, the way Madoka Magica is (tutu is moreso about fairytale ones). Tutu isn't winking and nodding at us the way Madoka does when she doodles magical girl outfits, or when episode 3 happens, or with Kyubei's whole deal.

CONCLUSION: Magic Children Fighting the Genre

So yeah, a lot of these deconstructions have nothing to do with "realism" or being "darker" and everything to do with the "exposing the shocking truth behind a functioning cliche" part of its definition, usually for cliches that are in that late life cycle, oversaturated stage, matching the way its audience has also grown more cynical in life. The stereotypical grimdark aspects come from that same teenage impulse to bash, to be edgey to be "more real."

In my previous post, I also liken "bashing" to the way victims of religious indoctrination finally escape and start spitefully "bashing" the religion out of a sense of betrayal. This comparison especially rings true for this post about deconstruction, as the term for the American Evangelical movement in which "Christians rethink their faith and jettison previously held beliefs, sometimes to the point of no longer identifying as Christians" is-- quite literally -- Faith Deconstruction or just Deconstruction for short. Isn't that fascinating? I think it proves my point.

Anyways, to even "expose the shocking truth" in the first place, you need faith or just some sort of idealistic jumping off point, which is why "Magic Children Fighting--The Genre" is so prevalent in genre deconstruction.

You can't just subvert and "deconstruct" forever, because at some point, you're just going to run out of meaningful things to say and end up having twists for no reason, as the Game-Of-Thrones-"Themes are for eighth-grade book reports"-writers ended up doing for season 8 lol. That's its own thought-terminating cliche. Thus, some sort of idealistic genre is necessary.

And "Magic Children Fighting: The Genre" is so rich in idealism. Whether it be shonen anime "You can do it!" or magical girl "Friendship is Magic" or high fantasy's underdog chosen one narrative or... whatever mecha shows are about.

Whichever "Magic Children Fighting: The Genre" archetype you choose, you can easily turn it into "Magic children fighting the genre!"

And I think that that's meaningful!

It's beautiful when adolescent media writers do manage to go that extra mile to think about how to make it so that their audience is able to enjoy the show as adults. It's cool when they refuse to handwave explanations or cliches and put genuine thought into work that kiddos might not appreciate at first.

In my next few posts, I'll probably go into works that manage to succeed at Deconstruction (Madoka Magica, Rebellious Girl Utena), works that people do not traditionally think of Deconstruction because they failed in some way (Steven Universe), and the darker implications of works that fail to do this (Harry Potter and The Christian Bible (ha ha jk on the bible. or am I?))

in the meantime, you can read this funny post and this funny post about how svsss kind of deconstructs masculine isekai narratives

#magic children fighting—the genre#analysis#A marriage of literary convention and real human psychology#metas#deconstruction#derrida#literary analysis#jacques derrida#madoka magica#puella magi madoka magica#pmmm#tropes#cliches#thought terminating cliches#cliche#trope talk#watchmen#game of thrones#across the spiderverse#into the spider verse#writeblr#comparative analysis#fandom#self awareness#fourth wall breaks#xtian hegemony

14 notes

·

View notes