#Depicting: Famicom cartridge

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Microgame$ - part 2

#Depicting: WarioWare Inc Mega Microgames#Depicted by: Game Boy Advance#Depicting: Famicom with Famicom Disk System attached#Depicting: Super Famicom#Depicting: Virtual Boy Controller#Depicting: Virtual Boy#Depicting: Game Boy#Depicting: Super Scope#Depicting: Nintendo 64#Depicting: Super Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Game Boy Advance#Depicting: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy)#Depicting: R.O.B. blocks#Depicting: Famicom#Depicting: Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Famicom Gun#Depicting: Family BASIC Keyboard#Depicting: Game Boy Game Pak#Depicting: Game Boy Advance SP

0 notes

Text

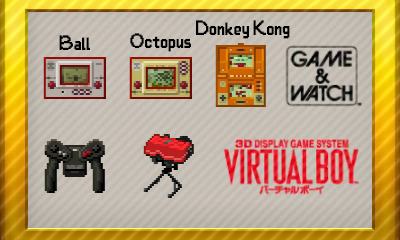

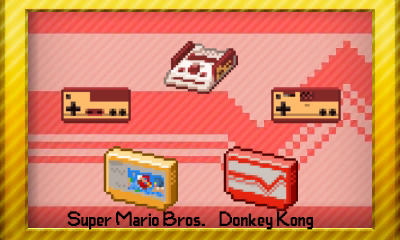

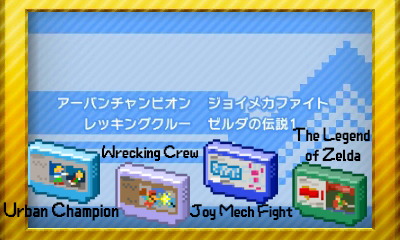

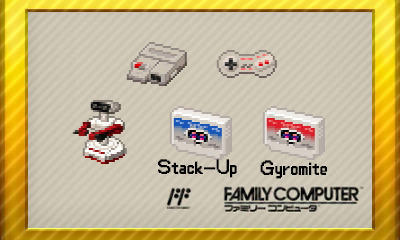

Nintendo Badge Arcade - part 3

So I spent three hours working on this exact project and when I asked a discord to try and see if anyone knew any of the last ones that would be tedious to find, I got sent this link xD

Wariofan63 - Absolutely amazing work, as someone who knows what it's like! Thank you so much for documenting this stuff! You're incredible :D

Nintendo Games in the Badge Arcade

Now if you know me, you know that I absolutely love Nintendo games and the one thing I love more than that is a Nintendo game about Nintendo games! Today I’m going to talk about Nintendo Badge Arcade, the free-to-play app you can download for your 3DS. The main draw of the game is that you play crane games to win badges that you can use to decorate your 3DS Home Menu with.

A good chuck of these badges are legacy Nintendo platforms and tagging along with them are tiny pixelated game cartridges. It can be hard to make out, but every single one of them is based on legitimate cartridge art (cart art)!

A couple years ago, I spent some time tracking down what each badge is a minituarized verison of and had a lot of fun doing it, so I made a guide of which games you can adorn your 3DS with.

Oh yeah, one thing to note here is that everything in this set of badges is based on the Japanese designs of the cartridges, so most might not look familiar to how you remember them.

Alright, are you ready? Let’s begin with some easy stuff, the Game & Watch games!

Now you’re playing with power! It’s the Famicom (NES) games! You’ll notice we got some cameos from R.O.B. as well as the controller with the bone-shaped controller.

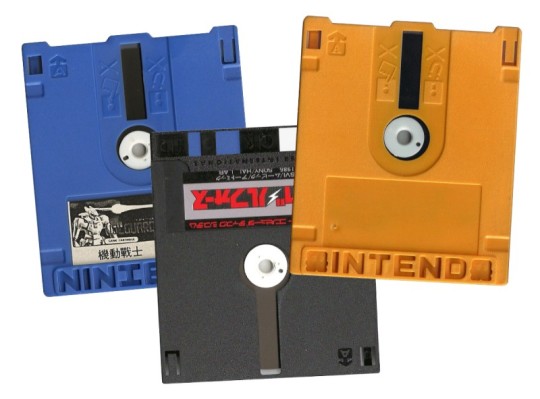

Now for what was the most difficult part for me, the Famicom Disk System games! Unfortunately all of these are Japan-only, so if you were hoping to decorate your 3DS with Zelda 2, I got some bad news or you.

This is going to get a little long so I’ll put the rest under the cut.

Keep reading

#Nintendo Badge Arcade#Depicted by: Nintendo 3DS#Depicting: Game & Watch Ball#Depicting: Game & Watch Octopus#Depicting: Game & Watch Donkey Kong#Depicting: Virtual Boy controller#Depicting: Famicom Controller I#Depicting: Famicom Controller II#Depicting: Famicom#Depicting: Super Mario Bros. Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Donkey Kong Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Clu Clu Land Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Balloon Fight Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Ice Climber Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Devil World Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Urban Champion Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Wrecking Crew Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Joy Mech Fight Famicom cartridge#Depicting: The Legend of Zelda Famicom cartridge

72 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Test image used during a graphics test in a Super Famicom service cartridge used internally at Nintendo of Japan to diagnose problems with the hardware, depicting unique Super Mario World-styled artwork of Mario with animal ears (presumably Raccoon Mario, though no tail is visible).

Main Blog | Twitter | Patreon | Small Findings | Source

443 notes

·

View notes

Text

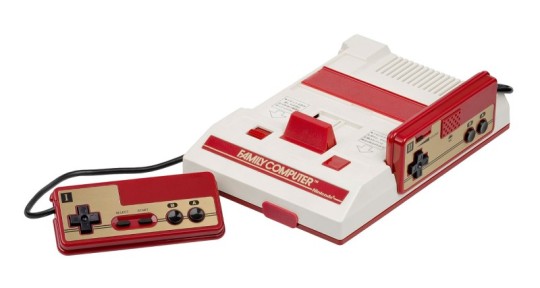

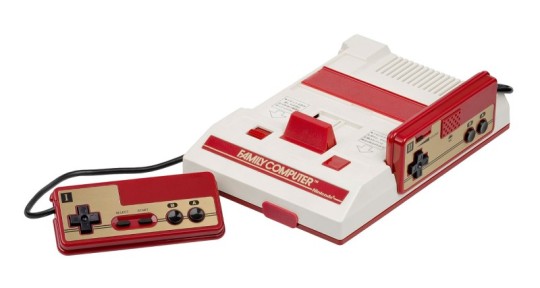

40 Years Later, Nintendo's Famicom Is Still Ahead Of Its Time

New Post has been published on https://thedigitalinsider.com/40-years-later-nintendos-famicom-is-still-ahead-of-its-time/

40 Years Later, Nintendo's Famicom Is Still Ahead Of Its Time

Introduction

As 1983 came into focus, the future of video games in North America looked bleak. Store shelves were crowded with poorly made games, and consumer interest waned substantially. Developers that ushered in the “golden age” of arcades and the first two generations of home consoles began to crash and burn at an alarming pace. In no time, the once billion-dollar industry was reduced to rubble.

In the summer of that same year, in Japan, gaming giant Nintendo released its first-ever home console with swappable cartridges. With its striking red and gold design, the Family Computer, better known as the Famicom, brought arcade hits like Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. into Japanese homes.

While the Famicom would go on to revitalize the North American gaming market as the VHS-inspired Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, many of Nintendo’s quirky games and accessories were forever locked in its home country. With the Famicom’s 40th anniversary at hand, there’s never been a better time to look back on the bizarre and surprisingly innovative experiments Nintendo unleashed on Japanese players throughout the console’s celebrated run.

Famicommunication

Famicommunication

Unlike the NES, the Famicom came with its two blocky controllers wired directly to the console. While one might think this tethered design was to keep players from losing controllers, it was actually a simple cost-cutting measure – one Nintendo would soon regret as more and more players sought out replacements. Aptly anticipating a future filled with wacky accessories, Nintendo also included a 15-pin connector on the front of the Famicom, ready for anything the future might hold.

The most surprising addition to the Famicom’s original design was on the console’s second controller – a minuscule microphone, complete with a volume slider. The microphone’s inclusion was spearheaded by Nintendo Research and Development lead architect Masayuki Uemura, who felt younger players would enjoy hearing their own voices crackling out of TV speakers. Though his prediction wasn’t exactly wrong, the Famicom microphone was notoriously underutilized by developers, mostly lending itself to a handful of iconic Easter eggs in single-player games.

While a few early titles did make use of the microphone, most Japanese players wouldn’t be hollering into their second controller until 1986’s The Legend of Zelda. The 8-bit masterpiece featured a slew of unique enemies for protagonist Link to defeat on his quest, but few so wily as Pols Voice. Depicted as blobby rodents with enormous ears, the instruction manual explained that the monsters “hate loud noises.” With a deafening roar into the Famicom’s microphone, which could only be found on the second player controller, all Pols Voice on screen would be thoroughly eradicated. This was a far superior method to attacking with normal weapons, as the enemies’ nimble movements and high health made them especially annoying.

Strangely, the description of the Pols Voice hatred of loud noises was included in the manual for the English release, despite the fact developers had retooled the dungeon-dwelling baddies to now be weak to arrows. Zelda fans outside Japan wouldn’t feel the thrill of shouting an enemy to death until 2007’s Phantom Hourglass for the Nintendo DS, which allowed players to once again obliterate Pols Voice with a well-placed shriek.

Other notable examples of the Famicom microphone include Kid Icarus and the infamously difficult Takeshi’s Challenge. The former allowed players to verbally haggle down the price of items with shopkeepers by yammering on about whatever they liked, while the latter, starring comedian, actor, and director “Beat” Takeshi Kitano (Battle Royale, Violent Cop), had players using the microphone for a variety of tasks, such as bringing up a map and singing karaoke.

Famicomputing

Famicomputing

When Uemura and his team were first tasked with designing the Famicom, they envisioned a gaming device with a 16-bit CPU, a keyboard, a modem, and a floppy disk drive. With costs considered, none of these superfluous features made it far into the planning stage, each launching as their own separate accessory in the years to come. The first to resurface, released in the summer of 1984, was the boxy Family BASIC Keyboard bundle, a collaboration between Nintendo, Sharp Corporation, and Hudson Soft.

Included with a taller-than-average black cartridge and a hefty user manual, the Family BASIC Keyboard and its accompanying software were intended for the blossoming home computer crowd. At the time, BASIC (short for Beginners’ All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) was seen as the ideal programming language for novice developers and casual players alike. Family BASIC tried to make things even easier by including extra support for character sprites (including preset Mario and Donkey Kong models), backgrounds, controls, and music. Famed Mario composer Koji Kondo even got in on the action, penning a section in the user manual on how best to program chiptune melodies.

Though the bundle cost a hefty ¥14,800 at launch (the same price as the Famicom itself), the kit didn’t come with a way for players to save their creations or share them with others. For this top-of-the-line feature, Nintendo suggested purchasing the Famicom Data Recorder, a device that saved one’s game directly to a standard cassette tape – for an additional ¥9,800. Ironically, sharing games and rampant piracy of Famicom titles had become a huge issue for Nintendo by this time. The problem got so out of hand that various media associations across Japan lobbied to update the Japanese Copyright Act, essentially banning all video game rentals countrywide. The ban, which does give individual developers the ability to allow rentals of their games (though they rarely do), still exists to this day. Despite its price point, the Family BASIC bundle sold well enough to warrant an updated sequel – Family Basic V3.

Nintendo even toyed with the idea of a keyboard for the NES, to be included in a never-released collection called the Nintendo Advanced Video System. Shown off at the 1984 Consumer Electronics Show, the NES keyboard was featured alongside prototype controllers, a joystick, a cassette recorder, and a zapper that looked more like a robotic wand than a gun. Amazingly, every accessory in the Advanced Video System was wireless, connecting via infrared technology.

Famicompatible

Famicompatible

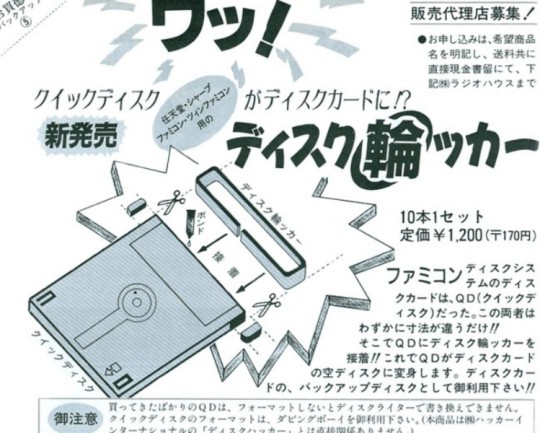

With the rental ban in full effect and piracy levels dipping, Japan’s general gaming public was feeling the sting of video game pricing. Nintendo, hearing the grumbles of its audience, researched ways of producing a cheaper option than its colorful cartridges. Enter the Famicom Disk System – a floppy disk add-on that both plugged into the top of the Famicom and sat below it. Though introducing an expensive new accessory (one that cost more than the console itself) to promote cheaper games might seem counterintuitive, Nintendo did just that in 1986.

Similar to floppy disks of the time, the games for Famicom Disk System were housed in a hard plastic shell and dubbed “Disk Cards.” Commonly produced in a brilliant yellow casing, the double-sided Disk Cards were impressed with a large NINTENDO logo at the bottom. This impression allowed Nintendo a form of physical lockout it hoped would help quell piracy. This wasn’t the case, as many clever bootleggers produced their own case molds with the proper inlays, often springing for misspellings like NINFENDO and NINIENDO to trick the Disk Drive. Regardless of their manufacturer, Disk Cards were considered too fragile by most players and poorly designed, with many prone to errors due to dust buildup.

Though games for the Disk System were cheaper, the true appeal was the ability to download new titles to endlessly-reusable Disk Cards via one of the 10,000 Famicom Disk Writer kiosks found at toy, game, and hobby shops across Japan. The process cost a paltry ¥500 (¥100 extra for an instruction sheet), or roughly a sixth the price of purchasing a new cartridge-based title. Not only could players download new games, but they could use each store’s dedicated “Disk Fax” machine to submit high scores directly to Nintendo for various tournaments. With player data in hand, Nintendo awarded tournament prizes ranging from Famicom branded stationary to gold Punch-Out!! cartridges, predating Mike Tyson’s $50,000 deal to lend his likeness to the series.

Nintendo’s hardware team was hard at work developing a different kind of add-on, one that would only work with the Disk System – 1987’s Famicom 3D System. Unlike the well-known glasses-free 3D of the 3DS, the 3D System used shutter glasses and alternate frame sequencing to create an illusion of depth. While the effect worked, the system was a substantial failure, with only six games ever produced. The most notable was Famicom Grand Prix II: 3D Hot Rally, considered by many to be the first Mario racing game and precursor to the Mario Kart series.

With Nintendo pushing all its newest first-party games to the Disk System to boost sales, the peripheral soon became the only way to play era-defining hits such as The Legend of Zelda, Castlevania, and Metroid, as well as Japan-only cult favorites like The Mysterious Murasame Castle and the Famicom Detective series. Despite their longer load times and flimsy housing, many consider Disk Card games a step above their cartridge counterparts, as the Disk System allowed for save features and a much richer audio experience. Though Nintendo would eventually return to cartridges with the Super Famicom, the Disk System was still a respectable success, with 4.4 million units sold in its four years on the market.

Famicommerce

Famicommerce

In North America, many think of the Sega Dreamcast as the first home console with online connectivity. But in Japan, every single Nintendo home console, from Famicom to Switch, had some form of internet compatibility. It all started in 1988 with the release of the infamous Famicom Modem, another clunky add-on, brimming with potential, that struggled to find a long-term audience.

The idea for the Famicom Modem came not from a desire to let players connect and play games together, but rather from something more dull – the stock market. As Famicom flourished, financial service company Nomura Securities approached Nintendo about using the system for people to check on stock prices in real-time and possibly even buy, sell, and trade stocks at home. Working closely with Nomura Securities, Uemura and his team developed a modem that worked with an online service dubbed the Famicom Network. Like the Famicom Disk System before, the Famicom Modem was plugged into the top of the console, allowing players to insert credit-card-sized cartridges for different types of transmissions. Lacking a dedicated keyboard, a special controller with a full number pad was included to help users navigate the number-centric software.

In July 1988, a test run of 1,500 prototypes produced outstanding results. With the Japanese stock bubble growing larger by the day, more and more investors were obsessed with checking market prices and making trades on the fly, an ideal situation for Nintendo. Unfortunately, this success soon evaporated when the Famicom Modem hit store shelves two months later. Nintendo was shocked to find its circuit system was unstable, leading to widespread circuit failure, and many users were less than thrilled with the modem’s cord-heavy set-up. Coupled with the inevitable burst of Japan’s stock market bubble in 1989, most were left uninterested in the add-on’s specific services – even those who owned it.

While the Famicom Modem flailed, Uemura and his team still tested the system’s gaming capabilities. Five prototype games were developed, the most prominent based on the ancient board game Go, but all were deemed failures in the end. “We were unable to realize our dream of using the modem to augment Famicom games,” Uemura told Nikkei Electronics magazine (via Glitterberri blog) in 1995. “The game would require players to be connected to the phone line for an extended period of time. If the problem of data transmission fees wasn’t enough, we were also faced with the risk of users monopolizing the phone line.”

The modem’s saving grace, outside of providing horse racing bets and results to diehard fans, was its ability to let toy and game stores share an online database. By inserting the Super Mario Club cartridge, stores could post reviews and communicate sales to one another, sharing what games were top sellers. Nintendo could also peek at this database, allowing the company to better understand the market consumer demand.

As with most of its promising technology, Nintendo toyed with releasing the Famicom Modem in the United States with a slight twist. If Japanese users could place bets on horses through the Famicom, Minneapolis-based company Control Data Corporation was confident American users could use an NES Modem to play the lottery. In 1991, with Nintendo on board, Control Data announced its plans to test a subscription model, wherein users could pay $10 a month to play all Minnesota-based lottery games via their NES. Unsurprisingly, it wasn’t long until the concept of adding unsupervised gambling to a home console aimed at children raised a few eyebrows in parent groups and the political sector – squashing dreams of an NES Modem before its initial tests ever began.

It’s easy to look back on the Famicom and focus solely on its iconic games, but looking deeper into the hardware and accessories that give it personality helps bring its influence and legacy into perspective. Like today, the Nintendo of the 1980s was willing to aim its resources towards innovative and silly concepts, striving to find the next niche in the gaming market. It stumbled from time to time, but there’s no doubt that even its failures brought a sense of wonder and joy to thousands of players along the way.

This article originally appeared in Issue 358 of Game Informer

#000#1980s#3d#add-on#America#anniversary#Article#audio#billion#Blog#board#bundle#challenge#Children#code#Collaboration#computer#connectivity#connector#consumer electronics#copyright#cpu#crash#cutting#data#Database#deal#Design#developers#development

1 note

·

View note

Text

Muneki Ebinuma’s commentary on various Technos projects

The following is a translation of various bulletin board posts that were allegedly posted by Technos Japan designer (and motion capture actor) Muneki Ebinuma on the now-defunct 喫茶ダブドラ/Kissa Dabudora (Double Dragon Teahouse) fansite back in the early 2000′s. Some of the inside stories he brought up he would later bring up in his Super Double Dragon and Double Dragon Advance commentaries he later wrote for the site Game Kommander, so these posts seem pretty legitimate.

Source: http://web.archive.org/web/20010305081410/http://www2.tkcity.net/~kissa/itadakimo.htm

Anecdote #1

When Kunio-kun no Jidaigeki Dayo Zen’in Shūgō! [a 1991 Famicom game. The title loosely translates to ”It’s Kunio-kun’s Historical Drama Play, Gather Everyone!”] was reaching the end of its development, I wrote a plan starring the Double Dragon brothers. It was basically the same gameplay system as Jidaigeki, but it took place in a kung-fu movie setting. It was supposed to be a Kunio-kun game, but it probably deviated a bit too much from the rest of the series. Development ended up being abandoned due to the strong popularity of the Kunio-kun sports game in our surveys, but I really wanted to make it. The Double Dragons were supposed to appear alongside Ryuichi and Ryuji [a pair of characters from the Downtown Nekketsu series modeled after Billy and Jimmy. In River City Ransom they were renamed Randy and Andy], since the project was intended to be a “festival of Technos” (of course, other guest characters would have also appeared). I was even planning to have Kunio perform the “shadowless kick” technique using a wire.

Anecdote #2

There’s quite many inside stories, so feel free to ask any questions you might have. Me nor Mr. Mitsuhiro Yoshida [co-director of Downtown Nekketsu Monogatari and many of the Downtown Nekketsu games alongside Mr. Hiroyuki Sekimoto] won’t mind.

The arcade version of Double Dragon started development as a sequel to Nekkketsu Kōha Kunio-kun and since we were aiming for the U.S. market this time, we started development using the graphic image of Renegade as a basis[the export version of the original Kunio-kun]. I heard that Kunio and Riki were supposed to be the Twin Dragons themselves, since they wore gakurans [a type of Japanese school uniform] with dragon embroidery within their jackets. The Kunio-kun series afterward then became console-centric [after the first two arcade games].

The arcade version of Double Dragon 3: The Rosetta Stone was not developed in-house by Technos, it was outsourced. However, the NES version [titled Double Dragon III: The Sacred Stones outside Japan] was made in-house. Personally the first two games were my favorite. Double Dragon II in particular was perfect for me. The story was pretty good too.

The Super NES version [Super Double Dragon, released in Japan as Return of Double Dragon in a slightly revised version] was supposed to be a port of the arcade game using an 8-Megabit cartridge, which was the largest ROM size at the time, but we were not familiar with the hardware and we didn’t know how to compress the size of the sprites, so it was impossible to match the character sizes of the arcade version. The Technos Arcade Team were responsible for the graphics and programming, so they had a peculiar roughness to it.

There were many ideas that ended up being cut since I was young and inexperienced at the time. There were texts and images that were being made for cutscenes that were inserted into the game’s ROM, but ended up being unused. The ending and sibling confrontation were even programmed into the game, but I was forced to patch it out due to fears that it would end up bugging the game. We were given priority to meet the announced release date given by the company. Thinking about it now, I believe I was disqualified as a provider. Shodai Nekketsu Kōha Kunio-kun [a 1992 Super Famicom game that came out only in Japan. The title translates to “The Original Hot-Blooded Tough Guy Kunio”] also had a troublesome development as well, since that game was also being made by people with no prior experience working on the Super Famicom. It was a very brief development period of around six months. I ended up learning things the hard way and that earned me a reputation of sorts within Technos. The sound test [in the Japanese version] has music tracks that isn’t played anywhere else in the game, like the boss theme. Actually, the boss theme was supposed to start playing during the unused conversation sequences with the bosses. Marian, the game’s heroine, doesn’t even appear in the game at all [despite being depicted in the Japanese version’s manual].

During the development of Hybrid Wrestler [a 1994 wrestling for the Super Famitsu endorsed by actual wrestler Masakatsu Funaki], I asked one of the designers to draw Billy and Jimmy Lee in the same size as the Street Fighter II characters. He also drew Abobo lifting a large rock. However, we ended abandoning that plan to assist in the development of Popeye on the Super Famicom and the arcade game Shadow Force. There were also plans to port Shadow Force to the Super NES, but they were canceled. If American Technos hasn’t asked us to prioritize the development of Popeye, then maybe Shadow Force and Double Dragon fmight had been made. [Other Double Dragon fighting games were later made, but the project Ebinuma is talking about here seems to be unrelated to either of those].

Personally I want to make a perfect port of the arcade game with some additional content. [Ebinuma would later get his wish with Double Dragon Advance]. If it wasn’t for that particular programmer and designer, that sense of roughness would had never been born. I was blessed to have such a staff. A good team is capable of creating a masterpiece. I think a game can be even more interesting if you know the joy of bringing out one’s imagination and creativity. I hope new game creators will be born out of the people who are familiar with Technos games. I’m looking forward to such a game that will entertain me.

Actually there are some larger-than-life people making games. Everyone has great potential. Please do your best in your various fields. Make an effort and realize your dreams.

Anecdote #3

If I remember correctly, I was taken to the vacation home owned by Mr. Yoshihisa Kishimoto [director of the original Nekketsu Kōha Kunio-kun and the Double Dragon trilogy] and his family around the time the scenario [screenplay] for Kunio-tachi no Banka [a 1994 beat-’em-up for the Super Famicom. The title translates to “The Eulogy of Kunio and Friends] was being finalized, where he told me various stories. The screenplay was bulky like a movie screenplay, in which every character and line was thoroughly described on every scene.

He told me he wanted to take the image of the original Kunio-kun arcade and upgrade it for consoles. Unfortunately, Mr. Kōji Ogata, the character designer of the original Kunio-kun, was unavailable due to another project he was assigned to, so the character designs ended up being very different from the conceptual stages. I though the characters looked on paper, but when they appeared on-screen within the game, they were not well-received within the company. It was neither, realistic nor comical, but somewhere in-between. It was really regrettable. But I remember being really happy when I was shown the animation of Kunio doing the Bruce Lee backfist. There was also a stage that was drafted that ended up being cut, as well as a scene that was planned out that didn’t make it, as well as a scene that was impossible to realize due to technical difficulties. Other than, Kishimoto-san was pretty satisfied with the final product.

Instead of Mr. Kazuo Sawa, the usual composer for the Kunio-kun series, the music was instead composed by Mr. Kazunaka Yamane, who did the music for the first two Double Dragon games.

The pixel art for the backgrounds were exceedingly good too. And punching sound effects sounded painful too. It was pretty interesting that familiar characters from the original arcade game appeared too. The enemy’s A.I. programming was a bit different though. There were some aspects of a fighting game that could be seen there, but it was also different.

The TV commercial, which was shot in live-action, featured weapons that was brought in by the company’s staff. The nunchaku there was mine! Mr. Kishimoto was once again really proud of that work. I really another Nekketsu Kōha to be made.

An illustration from a 1991 pamphlet featuring various Technos Japan characters.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The RPGs of the Super NES Classic #3: Secret of Mana

Original Release Date: August 6, 1993

Original Hardware: Nintendo Super Famicom

Developer/Publisher: Square Enix

Nintendo's 16-bit hardware had a lot of great action-RPGs, but perhaps none were as significant as Square's Secret of Mana. This was particularly the case in the West, where Japanese action-RPGs hadn't caught on quite as they had in Japan. The action-RPG label has always been a fuzzy one, with most of the games in the genre leaning pretty hard on one part of the label or the other. For many a player in the West, however, Secret of Mana was one of the first such games out of Japan that felt like it could satisfy both RPG fans and action game fans in equal measures. It also got considerable promotional support from Nintendo, which surely helped the game find its way into the hands of many young players. Adding to its legend is the fact that Square was never really able to make another game in the series that had the same appeal. With no rights issues holding it back, it's easy to see why Secret of Mana was chosen to carry the action-RPG flag for the Super NES Classic.

This is the first follow-up to Seiken Densetsu, otherwise known as Final Fantasy Adventure, Mystic Quest, Sword of Mana, and Adventures of Mana in its various forms. Secret of Mana is somewhat infamous for its tumultuous development, most notably its late shift from being a Super NES CD-ROM game to having to fit on just a regular cartridge. Apparently, a great deal had to be cut from the game and as a result, the final product feels a bit disjointed and buggy at times. Of course, this shift was only necessary due to Nintendo deciding not to pursue their plans for a CD-ROM add-on. While you obviously won't hear any official word about it, I've heard rumors to the effect that the debacle around Secret of Mana was one of the reasons why Square jumped ship from their previous Nintendo-exclusive status. Still, in spite of all that, Secret of Mana is a really enjoyable game, with a unique feel all of its own.

Or perhaps I should say "because of all of that"? I think I've mentioned before on this site that I believe the reason why Secret of Mana is the crowd-pleaser that it is comes down to those required cuts. Series creator Koichi Ishii is a developer along the lines of his former co-worker Akitoshi Kawazu. He favors ambitious ideas and doesn't seem all that interested in being tied down by the conventions of the genres he works in. Like with Kawazu, this has resulted in most of Ishii's works being love-or-hate affairs. He's even had his name attached to some genuine clunkers. His most widely-appreciated game is Secret of Mana. I can't imagine it's a coincidence that it's also the game where he had the least amount of freedom to pursue his ambitions.

Thanks to those restrictions, Secret of Mana ended up being not much more complicated than the Game Boy game that spawned the series. It's a much bigger game, and the presentation obviously blows its Game Boy predecessor away, but the weird and woolly sub-systems that would come to characterize the Mana brand are in short supply here. You can move around and attack with your weapon, charge up for a stronger attack, and cast magic or use items from a menu. Most of the weapons have a secondary use for navigating the world, and each weapon levels up individually as you vanquish foes with it. Magic similarly becomes more powerful the more times you use it. This probably sounds a lot like the much-maligned Final Fantasy 2, but the system isn't quite as broken here. Unfortunately, you'll probably still want to sink some time into grinding levels, particularly for magic spells. One nice point is that the weapons actually change form as you level them up. You only need to get each weapon type once.

One big change is that rather than playing as one character with a rotating guest controlled by the computer, you'll end up with a permanent three-character party. You can only control one of them at a time, of course, while a fairly stupid AI controls the other two. If you happen to have a couple of friends, a couple of extra controllers, and a SNES multitap, you can swap out that silly AI for some real humans. Square did this sort of thing from time to time in the 16-bit era, and while I'm not sure they really thought of it as more than a fun extra, it ended up being a major point in Secret of Mana's favor. People with multitaps were few and far between, but you could at least enjoy the two-player mode even if you didn't have one or know someone who had one. For its time, Secret of Mana was one of the best multiplayer RPGs you could find. The Super NES Classic unfortunately preserves that "missing third player" experience, but it's still a good time.

Truth be told, though, I think the game is a little too long and leisurely to play through completely with other players. Pulling your friend in for a boss fight is a good time, but it's not quite the same joyride when you're just parking yourself outside of a town, casting magic to raise levels. If you were a kid with a brother or sister who maintained a similar schedule to yours and liked playing this kind of game, then you were set. Otherwise, it's a fun thing to do now and then but you'll be thankful that it's basically drop in and drop out. I remember the first time I beat the game, I did it with a friend controlling the Sprite. In hindsight, that was definitely the easiest way to tackle that tricky situation. The computer AI really isn't up to doing what needs to be done in that particular fight.

There are a lot of weird moments in Secret of Mana that help lend it its flavor. I've written elsewhere before about the bizarre out-of-nowhere appearance of Santa Claus partway through the game, and while that's about as strange as the game gets, there's nevertheless a lot of instances of similarly unexpected gags and references. I remember finding out from a magazine that the possessed books that populated one dungeon had a small chance of flipping open to a naked woman and being shocked that Nintendo didn't force that to be removed from the English version. There are a couple of mysterious faces carved into the world map that don't have any explanation. Then there's the Ancient City, which flips your whole image of the game's setting upside-down. You go to the Moon, you travel by cannons, and you visit an island that sits on the back of a giant turtle. It's all very quirky, if a little scatter-shot in its tone.

The game on the whole is just as patchy as its eccentricities. It does a lot of things well. The variety of locales lends the game the feeling of a true adventure. The selection of weapons gives you some interesting combat options, and it's really satisfying when you land a solid blow on an enemy and thwack them into oblivion. The story may not flow well but it's interesting enough in the moment. At the same time, there are definitely areas that feel like they needed more thought. Having the player charge up an attack only serves to lengthen combat artificially, and when that attack misses because of the dubious collision detection, it's quite frustrating. The translation was done in a hurry and it shows. The game is very terse, and there's little room for proper characterization. The computer AI isn't up to snuff in many situations, which can be frustrating. There are bugs a-plenty, and there are plenty of places where you can feel the editing scissors in action.

Happily, the good parts of the game handily outweigh the minor annoyances. I don't find Secret of Mana nearly as interesting as some of Koichi Ishii's other games, but it's probably the easiest game of his to enjoy. I keep hoping to find another layer to the game whenever I come back to it, but it genuinely just is what it is. I thought I might find a new angle this time, having finally played Legend of Mana. All the context which that really provides, however, is to underline the rather obvious fact that Secret of Mana wasn't so much finished as it was buttoned up. Frankly, it's something of a miracle the game turned out as well as it did. Almost as unlikely as Square's seeming inability to satisfy players in the same way again, I suppose.

This was a game that I actually picked up around its original release date. I can't remember what exactly pushed me into it beyond being a general fan of Square by that point. I remember enjoying the Nintendo Power coverage of the game, and I recall that one issue came with a poster of the gorgeous cover art depicting the Mana Tree. That poster was hanging on the wall of my bedroom for quite a while, and I still think it's a great piece of art. The game's art design is excellent overall. The sprites are extremely expressive, with great attention paid to the enemies especially. The backgrounds are nicely detailed and always fit the intended atmosphere nicely. It's lush and verdant when it wants to be, cold and mechanical when it needs to be, and just all-around nice to look at.

The music is also superb. You have to believe this was one of the areas that took the biggest hit from the shift from CD to cartridge, but I can scarcely imagine how it could have been better aside from being played back at a higher quality. Composer Hiroki Kikuta's soundtrack has a very different feel from other Square games of the period, with a certain organic quality to it that almost perfectly matches the game. Even small things like the whale sound that plays when you power on the game help make this game sound different. The tunes shift from breezy to oppressive depending on the situation, but all of them are good at doing what they need to.

Above all, I think it's fascinating that Secret of Mana has been able to hang on to its legendary status over the years. Unlike contemporaries like Final Fantasy 6, Chrono Trigger, or Earthbound, Secret of Mana doesn't transcend its genre in any meaningful way. It's just a really fun game, one that Square has been decent about keeping in circulation for old fans to enjoy again and new players to discover for the first time. While none of Square's follow-ups have managed to capture a similar level of success, the company seems to understand that this game in particular is a favorite classic. The game has been re-released on the Wii Virtual Console, smartphones, as part of a Japan-only collection on the Nintendo Switch, and of course as part of the Super NES Classic Edition line-up. Secret of Mana is also getting a full remake that is due early in 2018.

As the sole representative of its genre on the Super NES Classic, Secret of Mana serves its purpose quite well. It's also one of the better multiplayer games in the package, albeit one that requires a fair bit of patience. It's unfortunate that Nintendo couldn't find a way to include the three-player mode, but I suppose it would be a lot of trouble to implement for just one game. Whether you go solo or with a friend, Secret of Mana is certainly worth playing again. Square hasn't managed to top its wide appeal with another Mana game in nearly 25 years, and it may well be another quarter of a century before they do.

Previous: Super Mario RPG

Next: Earthbound

If you enjoyed reading this article and can’t wait to get more, consider subscribing to the Post Game Content Patreon. Just $1/month gets you early access to articles like this one, exclusive extra posts, and my undying thanks.

#retro#gaming#super nes classic edition#secret of mana#super nes#snes#nintendo#square#seiken densetsu

1 note

·

View note

Text

Video Games

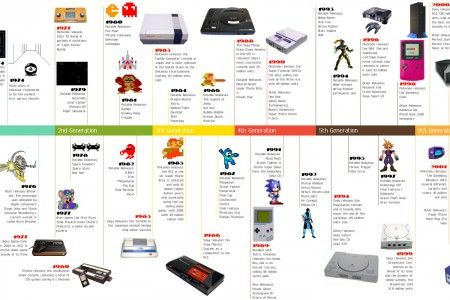

Today, video games make up a $100 billion global industry, and nearly two-thirds of American homes have household members who play video games regularly. And it’s really no wonder: Video games have been around for decades and span the gamut of platforms, from arcade systems, to home consoles, to handheld consoles and mobile devices. They’re also often at the forefront of computer technology.

The Early Days

Though video games are found today in homes worldwide, they actually got their start in the research labs of scientists.

In 1952, for instance, British professor A.S. Douglas created OXO, also known as noughts and crosses or a tic-tac-toe, as part of his doctoral dissertation at the University of Cambridge. And in 1958, William Higinbotham created Tennis for Two on a large analog computer and connected oscilloscope screen for the annual visitor’s day at the Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, New York.

In 1962, Steve Russell at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology invented Spacewar!, a computer-based space combat video game for the PDP-1 (Programmed Data Processor-1), then a cutting-edge computer mostly found at universities. It was the first video game that could be played on multiple computer installations.

In 1967, developers at Sanders Associates, Inc., led by Ralph Baer, invented a prototype multiplayer, multi-program video game system that could be played on a television. It was known as “The Brown Box.”

Baer, who’s sometimes referred to as Father of Video Games, licensed his device to Magnavox, which sold the system to consumers as the Odyssey, the first video game home console, in 1972. Over the next few years, the primitive Odyssey console would commercially fizzle and die out.

Yet, one of the Odyssey’s 28 games was the inspiration for Atari’s Pong, the first arcade video game, which the company released in 1972. In 1975, Atari released a home version of Pong, which was as successful as its arcade counterpart.

Magnavox, along with Sanders Associates, would eventually sue Atari for copyright infringement. Atari settled and became an Odyssey licensee; over the next 20 years, Magnavox went on to win more than $100 million in copyright lawsuits related to the Odyssey and its video game patents.

In 1977, Atari released the Atari 2600 (also known as the Video Computer System), a home console that featured joysticks and interchangeable game cartridges that played multi-colored games, effectively kicking off the second generation of the video game consoles.

The video game industry had a few notable milestones in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The Video Game Crash

In 1983, the North American video game industry experienced a major “crash” due to a number of factors, including an oversaturated game console market, competition from computer gaming, and a surplus of over-hyped, low-quality games, such as the infamous E.T., an Atari game based on the eponymous movie and often considered the worst game ever created.

The video game home industry began to recover in 1985 when the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), called Famicom in Japan, came to the United States. The NES had improved 8-bit graphics, colors, sound and gameplay over previous consoles.

Nintendo, a Japanese company that began as a playing card manufacturer in 1889, released a number of important video game franchises still around today, such as Super Mario Bros., The Legend of Zelda, and Metroid.

Also in 1989, Sega released its 16-bit Genesis console in North America as a successor to its 1986 Sega Master System, which failed to adequately compete against the NES.

With its technological superiority to the NES, clever marketing, and the 1991 release of the Sonic the Hedgehog game, the Genesis made significant headway against its older rival. In 1991, Nintendo released its 16-bit Super NES console in North America, launching the first real “console war.”

The early- to mid-1990s saw the release of a wealth of popular games on both consoles, including new franchises such as Street Fighter II and Mortal Kombat, a fighting game that depicted blood and gore on the Genesis version of the game.

The Rise of 3D Gaming

With a leap in computer technology, the fifth generation of video games ushered in the three-dimensional era of gaming.

In 1995, Sega released in North America its Saturn system, the first 32-bit console that played games on CDs rather than cartridges, five months ahead of schedule. This move was to beat Sony’s first foray into video games, the Playstation, which sold for $100 less than the Saturn when it launched later that year. The following year, Nintendo released its cartridge-based 64-bit system, the Nintendo 64.

Though Sega and Nintendo each released their fair share of highly-rated, on-brand 3D titles, such as Virtua Fighter on the Saturn and Super Mario 64 on the Nintendo 64, the established video game companies couldn’t compete with Sony’s strong third-party support, which helped the Playstation secure numerous exclusive titles.

Modern Gaming

The 8th and current generation of video games began with the release of Nintendo’s Wii U in 2012, followed by the Playstation 4 and Xbox One in 2013. Despite featuring a touch screen remote control that allowed off-TV gaming and being able to play Wii games, the Wii U was a commercial failure—the opposite of its competition—and was discontinued in 2017.

In 2016, Sony released a more powerful version of its console, called the Playstation 4 Pro, the first console capable of 4K video output. In early 2017, Nintendo released its Wii U successor, the Nintendo Switch, the only system to allow both television-based and handheld gaming. Microsoft will release its 4K-ready console, the Xbox One X, in late 2017.

With their new revamped consoles, both Sony and Microsoft currently have their sights set on virtual reality gaming, a technology that has the potential to change the way players experience video games.

0 notes

Text

Smol Yume Nikki theory: It takes place in the 80′s

�� I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one who has thought about this, and it’s probably not as unpopular. Maybe it’s just not talked about much, or people don’t really give it much thought. Which is cool, honestly. More fun for me here!

For starters, let’s look in the most obvious pace of interest here in the game: Madotsuki’s bedroom:

AND NO FOR ONCE WE’RE NOT GONNA TALK ABOUT THAT LOVABLY TACKY CARPET WITH WHAT ALL YN FANS CLAIM TO BE INSPIRED BY EITHER AZTEC OR PARACAS ART, LMAO. Let’s point out to something even more obvious but at the same time more shunned into a corner:

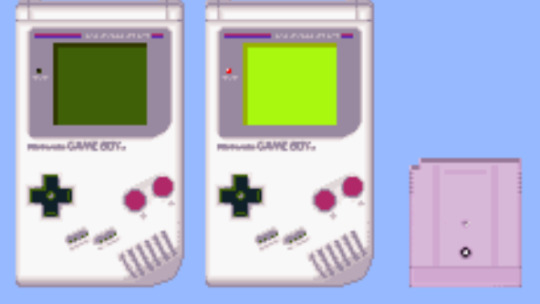

Her gaming console.

The Yume Nikki Wikia site says her console happens to be a Famicom, the Japanese counterpart to the NES. I’m no gaming history expert and for me video games were quite absent from childhood with cable TV with shows like Cartoon Network (Back when it was good...), Nicklodeon, Fox Kids (Does anyone else remember Fox Kids before they became Jetix today? Any of you out there???), and so on. I did and do still have a CCE Turbo Game old console packed away somewhere but it was always more played by my dad than me. So my first firmer dive into gaming was the Nintendo64, when my family recovered contact with some relatives, mostly cousins, and when we visited them, for the first time ever I saw them playing Mario Party 1 and Mario Kart 64. I think I was like 13?

ANYWAY, I’m no gaming history expert, but that in Madotsuki’s room... doesn’t really resemble a Famicom, especially the controller. It’s depicted as being round, while the Famicom’s were more rectangular... And I’m pretty sure it wasn’t in such a bright, vibrant pink color (Although that wouldv’e been pretty cool!) Or at least that’s what I would tell myself at first when I looked more into the console.

Yes, it is technically the NES many know, though Famicom was how it was more known in Japan. And yes it did have a more rectangular-shaped controller (Specifically, an oblong brick-like design) initially.

The original model Famicom featured two game controllers, both of which were hardwired to the back of the console. The second controller lacked the START and SELECT buttons, but featured a small microphone. Relatively few games made use of this feature. The earliest produced Famicom units initially had square A and B buttons. This was changed to the circular designs because of the square buttons being caught in the controller casing when pressed down and glitches within the hardware causing the system to freeze occasionally while playing a game (Probably the 80′s version of that dreaded noise when you have a BSOD.)

Two game controllers, both of which were hardwired to the back of the console. That is obviously not what we see in Madotsuki’s console. For once there is only one controller in view implying they can be unplugged, and it’s linked to the console at the front, which quite rules out the original model Famicom.

I mean, it is very difficult to accurately point out what console that bunch of simple pixels is supposed to be. But aside from the Wiki itself claiming it’s a Famicom, let’s look at another detail in Yume Nikki that points to that: The parts of Madotsuki’s dream-world where everything (Including the frickin’ menu!) take a retro 8-bit design and aesthetic.

In RPG Maker, many files of the game that are responsible for these parts of the dreamscape share something in their filename. Annnnnd yeah, since they’re names in Japanese, extracting or whatever you do to them has a big chance of turning their names into that bunch of random gibberish. BUT! They tend to share two letters actually in English, which also lead to fans’ names to these respective dream-worlds: FC. FC World (Yeah some of the dream-worlds have pretty on-the-nose names but honestly that’s actually fitting for Yume Nikki somehow.) Most likely dreams that Madotsuki has, influenced by her gaming experience.

FC, is a shortening of “Famicom”. And these dreams are both sonorous and graphically similar to the only game you can play on Madotsuki’s console (Yep, a game inside a game, bro.): NASU.

The graphics and sound highly resemble authentic Famicom/NES hardware capabilities, although the game itself is fictional.

And according to the wiki, there is a Famicom menu in the game, which could indicate that maybe there were more games supposed to be included along with NASU for Madotsuki/the player to play.

So yeah that bunch of pixels might not exactly resemble a Famicom much, but I guess Kikiyama just wanted to make it simplistic and generic-looking to a certain degree instead of pixelating it exactly into an existing console model, despite apparently there being hints within the game files that it’s in fact a Famicom. And yeah the vibrant pinkish hue is kind out of place for this console in reality, especially back in a time where video-games were more seen as a boy-thing, so why would it be pink of all colors? I’m not sure if it happened to this console in particular, but there has been several cases of different-looking versions of a same game console usually as limited editions. Usually they were like colored differently, or like I remember in the N64 case, even had its shell semi-transparent so you could actually see its inner mechanics! Not to mention I have a yellow N64 controller as well. So a pink limited edition Famicom maybe isn’t too far-fetched. Especially if this ties with another theory that Madotsuki lives in Japan. If it was there it probably would be kind of exclusive to there, or at the very least be nearly impossible to see traces of those limited editions here, especially in a time like the 80′s (No EBay or anything like that, man.)

Since the Famicom being the Japanese NES isn’t completely untrue, and considering it did have a couple redesigns since its first release on 1983, while I still say Madotsuki’s controller looks round and smooth, almost like a Super NES controller.

BUT HOLD ON A SECOND. Look at her console again, look closely. It does look like it has two slots, doesn’t it? Well, what other game console was known for having two slots (So it could take cartridges of two different sizes) AND round controllers that were linked by the front and could be unplugged?

The CCE Turbo Game.

BOOM. Well, not really boom, it was just really interesting to point out. There most likely have been other consoles with this double-slot feature. But like I said before, it’s hard to determine what console it is merely by looking at its pixels, so I’d say take the clues in Yume Nikki’s gamefiles, and NASU’s similarity to Famicom/NES games.

So, taking into account of it being a Famicom, but with still a round controller, I can’t say it was one of the first released models, square-like, much less hardwired to its back. But since I’m not here to cover whether Madotsuki lives in Japan or in America (Like, the creator is Japanese yeah, but Madotsuki’s room is very western-like too) which would be important to help definite which set of time she’s at, I will have to fluctuate that Yume Nikki takes places around from 1985 to maybe 1988, where this console was very popular.

BUT. Moving on from her console, whew. Let’s look at another thing in her room: Her TV used to play her Famicom game in the first place.

That is obviously not one of those thin HD TVs, ohohohoh oh no sir. That is quite clearly a box-like, heavy bastard of a retro tube TV (And you probably there thinking that your 2 pound laptop’s a deal, try working on a moving company back in a time where nearly every moving family at least had one of these heavy turds.) And believe me, I STILL HAVE THOSE IN MY HOUSE, AND THE MOST MODERN MODEL OF THEM HERE ACTUALLY COMES WITH A GAME OF TETRIS TO PLAY WITH THE REMOTE.

Now I’m not gonna try to point out the TV’s side or model because that would be even more impossible than trying to determine what’s Madotsuki’s console, as the TV looks even more generic and simplistic than the former.

But, it’s clearly not thin like those plasma or LED or HD or whatever the heck the cool kids have of latest model nowadays, and aside from being obviously a tube TV, look how it seems kind of rounded, slightly “inflated” like, rather than sharply square-like. While yes, there were sharp-looking square/rectangular tube TVs, these rounder, smoother models were more common in the 70′s and 80′s than they were in the 90′s, as even as still tube TVs they were slowly evolving to the sharp straight ones we have currently.

And obviously point out how there’s no visible modern item in Madotsuki’s room. No computers, mobile phones, her desk apparently has only a diary that she writes on (Which is how you save your game progress) even though you don’t see it there because it’s probably too small to even bother pixeling, or she keeps it inside that little drawer and only takes it out when she’s gonna write on it.

Next, I’m going to move to some aspects of Madotsuki’s dream.

I’ll start with the one place called The Pink Sea (Or Charcoal Sea, or Pastel Sea, or Pastel Shoal, or Pink Lemonade Ocean because that’s literally what it is and you know it’s true,) more specifically, Poniko’s room.

Aside from it lacking any sort of visible modern-looking item just like Madotsuki’s room, just look at the colors used there. Pastels but still “firm” colors (In fact all the Pink Sea is colored in that aesthetic.)

Know what these hues remind me of? 80′s Saturday morning cartoons.

I get reminded of cartoons like My Little Poney (The old version, not the modern one you all know), The CareBears, the 80′s TMNT series, just to name a few. Their palettes often seemed soft, almost pastel-like, not to mention, the place does give a sort of 80′s aesthetic vibe too.

Sure, Poniko’s room, and the Pink Sea altogether are only seen in Madotsuki’s dream in the game, like around 99% of everything else there, which maybe could discredit it being any clue to the time of the events of the game. But the room, despite being a dream, looks so well-shaped and un-abstract, Madotsuki must have seen it in real life, and recently, too. Otherwise her memory of it would have been a little fuzzy in the dream.

Though, the Neon World also reminds me of the Neon 90′s which was like between 1990-1994 I think? Take Adventures of Sonic the Hedgehog cartoon as an example of a Neon 90′s cartoon.

Lastly, a small touch to Madotsuki’s behavior (This might get triggering a bit, but if you’re a Yume Nikki fan, you likely know very well where this is going.)

She doesn’t seem willing to leave her room, or to even as much open her door. The closest she lets herself gain from the outside is going to her balcony, and yet we don’t see any other sign of civilization in the background, not to mention there seems to have some fog, which points out she’s in a tall apartment complex.

That, isn’t as uncommon as we think, especially in Japan (Though again I’m not going to point out where she lives, so I’ll keep my view on that non-biased.) These people, are known there as hikkikomori, or shut-ins, people who withdraw themselves away from society, confining themselves to only inside their house or even more so only inside their room. While people have been trying to be more understanding of those shut-ins and trying to help them, back then, these people were a lot more seen as a shame to their families and rather than seek out help, they would simply not speak of their shut-in’s situation because it would embarrass their family. And as to help cover up that, they supply their shut-in with food and whatnot without seeing how that sheltering would affect them in the future rather than help them face and overcome the issue and encourage them to try being part of society again. I’m sure it may still happen nowadays but most likely not as much as back then. That may explain why nobody seems to come check on Madotsuki during the game (Unless they do while she’s sleeping, who knows?) and probably only come in to supply her with breakfast/lunch/dinner etc. This could imply that her family is ashamed of her choices, and probably see her and are snarky about her being a “failure” to their family name. This could have fed onto Madotsuki’s negative behaviors even furthers, striking her with feelings of guilt and depressions for being a shame to her family, but at the same time feeling even more unable to come out of her shut-in tendencies and choices. Like she was cornered with both hands tied. That, alongside her rather gloomy dreams, may have led her to her tragic end at the game’s ending (Which breaks my heart to this day, man.) She would have had bigger chances of getting help than getting to that point in a more current time, than a time like the 80′s, as people have been trying to improve life quality in many aspects at such a strong pace since around the 90′s to today.

Sure, there are many other theories to why Madotsuki won’t leave her room, but most of them does involve her being a shut-in, while fewer ones with other reasons like she being grounded by her caretakers, kidnapped then locked, actually trying to keep herself safe from something right outside her door, etc.

And not only her behavior, Madotsuki’s fashion does resemble that of like a 80′s little girl, or perhaps early 90′s. Aside from the braids, her clothes are very up to speculation only by these sprites. That’s why fans depict her with all sorts of red shoes. Maryjanes, sneakers, converses, slippers, or even just red socks.

So my final guess: Yume Nikki takes place somewhere between 1985 and 1989.

However, it’s not uncommon for people to still own and enjoy a Famicom today despite being considered an outdated console now, though the old tube TV is a bit of odd nowadays (Unless you’re in my family, we only have those lol) but hey, it’s just a theory, A GAME TH-- Uh. Yeah I’ve been watching a lot of The Game Theorists video yesterday and today, whoops.

#yume nikki#game theory#outofpillows#not really a headcanon but if you wanna take it as one just make yourself at home darlin'#headcanon#it's past 9am and instead of sleep i wrote this#dont be like me guys

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Attract Mode’s One & Only Recommendation For Cyber Monday 2017

… was the Sega Saturn prototype that you see above, which one could find on eBay, according to videogamesdensetsu. Yet it was absent when I checked, meaning the auction was either yanked or it had already found a new home. Sorry folks.

Which is why I must refer to my second choice, that being this shirt featuring Sonic laughing, courtesy of RageOn…

Though miki800 is the place to go for serious Christmas gift recommendations. Like these Super Mario Odyssey santa hat ornaments…

Then you have this Kirby shirt (among others), and this coming from someone who isn’t a particularly big fan of the franchise; sorry, but I find the games simply “okay” and am even more indifferent about all related merch, except for this one…

Meanwhile a franchise that I do most certainly dig is R-Type. And given how I’m also fairly stocked up when it comes to shirts, but could definitely use a sweatshirt or sweater now that it’s getting colder, I most certainly wouldn’t mind one of these...

Now, Xmas is mostly for the kids, as are toys. Yet I’m pretty sure you need be around my age (I’m 40 btw/fyi) to want this WinBee toy (to match the recently release TwinBee toy, naturally)...

Speaking of toys that aren’t necessarily for kids, a heads up: Tokyo Otaku Mode has a MegaTen: Devil Survivor 2 figure at a fairly deep discount [UPDATE: and it’s sold out, sorry about that]...

Though if the membership price of $79 is still too much, or if you’re just mostly looking for a stocking stuffer, then how about this tiny cartridge, spotted by Tiny Cartridge!

Speaking of the Super Nintendo, here’s one stuck inside a wall for whatever reason, as spotted on Reddit…

Though let's bring it back to Tumblr, shall we, and on a semi related note is this gorgeous assortment of assorted game controllers, plus a few carts (via dinobot711)...

But if all black is more your thing (via theodorexnicholson)...

Does anyone know what the is being said here? Am assuming it might have something to do with transformation (via hlfat)...

Deep in woods, resting and waiting, is the mighty Dreamcast (via posthumanwanderings)...

Back to videogamesdensetsu, here we have a promotional leaflet to help promote the just launched PC Engine…

And another beneath the hood look, this time for a fictional piece of hardware, is courtesy of Pequeño Capitan (via it8bit)...

Sticking with art, which tribute to Galaga do you prefer? This one from Ben Tolman...

Or this other one from Allie, aka WatermelonAcups…

And here we have JoJo, aka MossMeldoy’s depiction of Fox McCloud, one that is not quite as calm, cool, and collected as Nintendo’s...

Moving from Star Fox to Phantasy Star; here’s Wayne Kubiak , aka wanyo’s slightly more pixelated view of part 4...

crashcarnival observes: “The three essential elements of Shaolin Kung Fu according to Shaolin Campus King”...

From the same source comes snippets from the Sega CD version of Time Gal; I’ve long been a fan of its unique combo of pixels and cel animation (especially its take on depth)...

And time for a complete and total shift in tone, courtesy of the PS2 title Rule of Rose (via asobi-station)...

From geographyofrobots comes something that… I’m not entirely sure is a game or not...

Then you have something else that seems almost too crazy to be an actual game, yet that’s what Hate Punishment! 2, Honwaka Soft is (via mendelpalace)...

My goal in 2018 is to track down a copy of Germs, If only to visit “Long Island Delicatessen” (via fmtownsmarty)...

Hey, speaking of food, behold my fave thread on Tumblr in recent memory (via capcomvssnk)...

And speaking of Pokemon (is something you may have seen ages ago, on Twitter, but it’s my first time seeing it on Tumblr, so there’s that; via lunaticobscurity)...

And speaking of cats (is something I believe I might have shared around here, also ages ago, but once again the function on Tumblr sucks, so; via hiyoushouldcheckmyblog)...

I wonder what sure came first; Game GIrl Advance, a fictional handheld that was clearly inspired by the Game Boy Advance (SP, the Famicom edition to be exact), as seen in the anime Arcade Gamer Fubuki, or Game Girl Advance, the blog belonging to Jane Pinckard from back in the day (via daftpunkyoshi)...

Behold what an arcade looks like in the world of Gundam (via bubblegumcrash)...

Plus what an arcade looks like the world of Archie Comics (via atomic-chronoscaph)...

Apparently building Cuphead arcade cabinets is a thing? Here’s one spotted by drowsypal...

And another made by someone on Reddit...

... may as well share the accompanying video…

youtube

I love a good mash-up, and King of Fighters X Fresh Prince hits the spot on numerous levels (via derekstronk)...

Prokopetz’s reaction to this decorated skeleton from Germany is pretty on the money: “This guy is definitely the final boss of something.”

As is werkhvnty’s: “Honey I appreciate you uploading a torrent of Elm Street 4 but I’m not gonna befriend you on WoW”

oomles states: “I work at a GameStop. Someone tried to trade in a contoller with rocks glued to the thumbsticks and got angry when we wouldn’t take it.

I’m so tired.”

Now, as most of you know, the plug was recently pulled on Nintendo’s Miiverse. So here’s a modest reminder of why it was never really long for this world in the first place (via paulthebukkit)...

Finally, and for no particular reason, am going to end things with some Burning Rangers cosplay. Enjoy…

Don’t forget: Attract Mode is now on Medium! There you can subscribe to keep up to date, as well as enjoy some “best of” content you might have missed the first time around, plus be spared of the technical issues that’s starting to overtake Tumblr.

0 notes

Text

Animal Crossing - Part 4

All from https://nookipedia.com/

#Animal Crossing#Depicted by: Nintendo 64#Depicted by: GameCube#Depicting: Donkey Kong 2 NES game box#Depicting: Donkey Kong 3 Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Donkey Kong Jr. NES game box#Depicting: Donkey Kong Jr. Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Golf NES game box#Depicting: Golf Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Pinball NES game box#Depicting: Pinball Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Punch-Out!! NES game box#Depicting: Punch-Out!! Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Soccer NES game box#Depicting: Tennis NES game box#Depicting: Tennis Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Wario's Woods NES game box#Depicting: Wario's Woods Famicom cartridge#Depicting: NES game box (derivative)#Depicting: Excitebike NES game box

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Super Smash Bros. Melee - Part 2

From https://tcrf.net/Super_Smash_Bros._Melee/Version_Differences

From https://www.ssbwiki.com/Flat_Zone

From https://www.ssbwiki.com/List_of_SSBM_trophies_(Others)

#Super Smash Bros. Melee#Depicting: Super Famicom Game Cartridge (derivative)#Depicting: Game & Watch Helmet#Depicting: Super Nintendo Entertainment System Super Scope#Depicting: Disk-kun shaped game case#Depicting: Nintendo GameCube

0 notes

Text

Super Smash Bros. Melee - Part 1

FDrom https://www.spriters-resource.com/gamecube/ssbm/

From https://tcrf.net/Super_Smash_Bros._Melee/Version_Differences

#Super Smash Bros. Melee#Depicted by: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Nintendo GameCube Controller#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Game Boy#Depicting: Super Smash Bros. Nintendo 64 Game Box#Depicting: Nintendo 64#Depicting: Super Smash Bros. Nintendo 64 Game Pak#Depicting: Nintendo 64 Controller#Depicting: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Game Boy Advance#Depicting: Game Boy Pocket#Depicting: Super Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Virtual Boy#Depicting: Famicom#Depicting: Golf Famicom Cartridge#Depicting: Dai Rantō Smash Brothers Nintendo 64 Game Box#Depicting: Dai Rantō Smash Brothers Nintendo 64 Game Pak#Depicting: Super Famicom#Depicting: Super Famicom Controller

1 note

·

View note

Text

WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Microgame$ - part 1

All from https://www.spriters-resource.com/game_boy_advance/wariowareincmegamicrogames/

#WarioWare Inc Mega Microgames#Depicted by: Game Boy Advance#Depicting: Famicom Gun#Depicting: Game Boy#Depicting: Game Boy Game Pak#Depicting: Game Boy Advance#Depicting: Game & Watch Helmet#Depicting: R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy)#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System Controller#Depicting: R.O.B. blocks#Depicting: Famicom#Depicting: Stack-Up Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Game Boy Game Pak (generic)#Depicting: Game Boy Advance Game Box (derivative)

0 notes

Text

Animal Crossing - Part 3

#Animal Crossing#Depicted by: Nintendo 64#Depicted by: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Mario Bros NES game box#Depicting: Mario Bros Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Ice Climber NES game box#Depicting: Ice Climber Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Balloon Fight NES game box#Depicting: Balloon Fight Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Baseball NES game box#Depicting: Baseball Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Clu Clu Land NES game box#Depicting: Clu Clu Land Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Donkey Kong Jr. Math NES game box#Depicting: Donkey Kong Jr. Math Famicom cartridge#Depicting: Donkey Kong NES game box#Depicting: Donkey Kong Famicom cartridge

1 note

·

View note

Text

Animal Crossing - Part 2

From https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/13sRAcj9YbP9_i-u0Kg6S7ycHbaOQx1jFG4lYLm2DJ4c/edit

from https://nookipedia.com/wiki/Item:IQueGBA_(D%C3%B2ngw%C3%B9_S%C4%93nl%C3%ADn)

All from https://nookipedia.com/

from https://www.spriters-resource.com/fullview/23441/

from https://www.spriters-resource.com/fullview/109190/

from https://nookipedia.com/wiki/Item:Game_console_shirt_(D%C3%B2ngw%C3%B9_S%C4%93nl%C3%ADn)

#Animal Crossing#Depicted by: Nintendo 64#Depicted by: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Famicom#Depicting: Famicom Cartridge (generic)#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System controller#Depicting: iQueGBA#Depicting: Mahjong Famicom Cartridge#Depicting: The Legend of Zelda NES Game Box#Depicting: Famicom Disk System#Depicting: Gomoku Narabe Famicom Cartridge#Depicting: Super Mario Bros NES Box#Depicting: Super Mario Bros Famicom Cartridge#Depicting: Derivative#Derivative: Nintendo GameCube#Depicting: Nintendo Entertainment System Game Pak (generic)#Depicting: Pokémon Pikachu 2 GS#Depicting: Game Boy Color#Depicting: iQue Player

0 notes