#Danish Shipyard

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

A little film to celebrate that Burmeister and Waine had the jubilee of having produced 7 million CV. Sorry; Danish speak, but great pictures :)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Reffen#københavn#copenhagen#copenhill#simon#denmark#danish#shipyards#industrial zone#amager#harbor#🇩🇰#my photos#photography#summertime#summer

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rare Ancient Stamps Found in Denmark

In the center of Falster, southeast of Denmark, a man with a metal detector has made an important discovery. The discovery is so important that it could help write a few chapters for Danish history or at least the local history of Falster.

While Lennart Larsen was out on a rainy day and searching for anything of historical value, he suddenly heard a faint beep in his equipment, and when he checked the ground, he discovered small, interesting objects, unlike anything he had seen before.

A faint beep has indeed revealed a special stamp in the ground – a so-called Patrice – that was used to make gold images, which are believed to be gifted to the gods.

The Museum Lolland-Falster has been informed. The only two-centimeter-long object in Falster’s soil may be a trace of a former royal power on Falster, the museum said.

“This indicates that we are standing in a place that has meant some trade and probably also had some form of cultic activity. And although it’s a bit wild to say, it could also indicate that it was once a center of power on Falster,” museum inspector and archaeologist Marie Brinch from the Lolland-Falster Museum said.

She emphasizes that the discovery was made in an area with names dating back to the Viking Age or even earlier and that the marshland was discovered in an area that had been sacrificed to the gods in the century preceding the stamp’s creation.

Archaeologists have before come across several signs of activity from the Iron Age and the Viking Age have been found, including an enormous shipyard and a large castle from the Viking Age at Falster. However, only a small number of discoveries have been made that can demonstrate where the island’s wealthy elite resided in the years prior to the beginning of the Viking Age. The new find may help to shed light on that.

Researchers have determined the tiny objects are stamps from the era just before the Viking Age. They were created between the years 500 and 700.

According to Margrethe Watt of the National Museum, who collects and researches ancient gold coins and stamps, these are extremely rare. There have only been 28 stamps discovered in the entire Nordic region, including the one from Falster, and it is a very unique stamp. South of the Baltic Sea, no stamps or gold coins have been discovered.

“The stamps are all very special. We only find them in the most important places of residence – those that we call the central places in the technical language. These are the places that we associate with the greatest magnates or kings. That’s the league we’re in here. And this stamp is at the same time very much for itself in its style,” she says.

“On the stamp from Falster, you can see a person in fine clothes, standing with their hands at a very special angle. The hands are down, and the palms are visible. It is something that we know in both Christian and pre-Christian cultures as either a sign of submission or a revelation. It is also a symbol that we see in many churches today, Watt explains.

Neither the god nor the king were shown as weak or flawed in any way. And you don’t see that on the stamp from Falster either. “This means that it is either a royal figure who submits to a god – or that it is a god who reveals himself to a human being,” she says.

“It is actually difficult to see if it is a man or a woman who is depicted. You would see that by the fact that there is a tuft of hair on the back of the piston. But it may well appear that there is, she says, and emphasizes that it requires further investigations to determine whether this is the case.

As there may be more finds in the ground at the site, Museum Lolland-Falster does not yet want to publish where the find was made – but states that it was made in central Falster.

By Leman Altuntaş.

#Rare Ancient Stamps Found in Denmark#Falster Denmark#patrice stamp#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#Iron Age#viking age

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

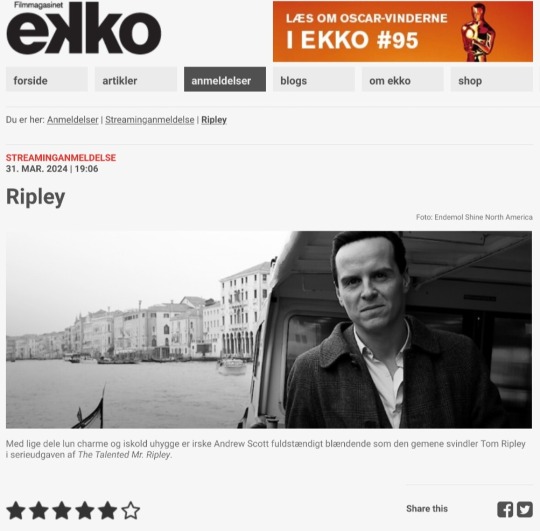

I'm pretty sure there's meant to be an embargo on press discussing Ripley until the 4th, but this Danish reviewer appears to have jumped the gun a bit.

Aesthetically pleasing series with chilling Andrew Scott is a welcome alternative to the summer vacation-ready movie adaptation of Highsmith's thriller.

(English translation below the cut)

By Kristian Ditlev Jensen

Ripley is the title of Steven Zaillian's adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's recurring character Tom Ripley, who is the protagonist in five of her psychological thrillers.

The first book is the magnum opus The Talented Mr. Ripley, which has been adapted into several films. Most famously, the 1999 version starred Matt Damon and Jude Law.

The story is about a young conman, Tom Ripley, who hustles his way through life, but one day gets mistaken for someone else. He seizes the opportunity and gets the offer of a lifetime from Mr. Greenleaf, an elderly shipyard owner.

"Go to the stunning Amalfi Coast in Italy and find my son Richard Greenleaf. Persuade him to come home!"

In Italy, Tom quickly finds Dickie, as he is simply called. But instead of bringing him home, he murders the man and assumes his identity.

In a formidable double-cross, he fools everyone by pretending to be both Tom and Dickie when it suits him. All goes well until a police inspector from Rome starts to smell a rat. And soon the hunt is on for the perpetrator.

The journey takes them via Sanremo, Palermo in Sicily, Rome and Venice. But the the criminal is always gone, even though the policeman is actually sitting and talking to him!

Anthony Minghella's feature film is good, but it's also a legitimately summer-holiday-ready, box office-targeted take on the story of a con artist and low-life con man. Now this version finally gets competition from a far more uncompromising, over-aestheticized and visually astonishingly harmonious work, starring Andrew Scott (All of Us Strangers) with warm charm and icy creepiness.

It's not every day you see such a well-designed series, where everything from the dramatic choice to shoot in black and white, to the typography, to the production design of interiors and costumes is thought out down to the last detail.

"The light. Always the light."

The line comes from a Catholic priest standing just behind Tom Ripley, who is looking at a Caravaggio painting.

Michelangelo Merisi, as the Italian painter was originally known, took his artist name from the village of Caravaggio near Bergamo. And it was he who coined the art term chiaroscuro - or clairobscur in French - in the years around 1600.

The term refers to a painting technique where dark and light are contrasted so that the images almost appear as black and white paintings.

Steven Zaillan - who wrote the screenplays for Schindler's List, Awakenings and Gangs of New York - has just modeled Ripley on the painter Caravaggio, who lived a dramatic life to say the least.

In 1606, Caravaggio stabbed pimp Ranuccio Tomassoni in the thigh with a small sword, causing him to die from the blood loss. The painter lived on the run for years before being pardoned by the Pope, but died immediately afterwards of a fever at the age of 38.

This story is on every level behind the series.

Ripley is shot in black and white, i.e. modern clairobscur, just like Caravaggio's own works. It's also about a criminal on the run and a murderer.

The story goes on and on.

In a key scene, there is a cross-cut between the historical Caravaggio sitting at a table with the murder weapon, a short dagger, and Tom Ripley sitting with a fountain pen in front of him.

In the twentieth century, you could kill with a pen. Today, you'd probably do it over the internet.

The whole analog universe that Steven Zaillian revels in - the series is set in the 1960s, while the novel was published in 1955 - is a stroke of genius. It allows him to work sensually with a wide range of things that seem to have disappeared today.

There are phone booths and people write notes to each other with pens. The typography is almost a tribute to the printed media in the form of newspapers, books, writings, signs, stamps, letterheads, patches of text, forms, checks and so on.

Similarly, shoes are a little story in themselves. And drinks. And ashtrays. At the same time, the declaration of love for the Amalfi Coast is so authentic it makes you dizzy.

The fact that the series is shot as something of an homage to the black-and-white king of them all, director Orson Welles, doesn't make it any less impressive. With a wealth of indirect and direct quotes from, for example, The Third Man, where the play of light and shadows on the walls of the stairwells play a major role.

Ripley is a rare true work of art on Netflix.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

When turbine blades for the United States’ first offshore wind project left port in September 2023, headed for the Vineyard Wind 1 project off Massachusetts, they were traveling on a barge instead of a wind turbine installation vessel, or WTIV. These purpose-built vessels are common in other parts of the world and make the job much, much easier. A WTIV is a transportation and construction rig in one. Frequently equipped with a big crane, deployable legs, and a dynamic positioning system, WTIVs can support the installation of several humongous turbines per trip.

There are dozens of WTIVs plying the world’s waters. So, why were the Vineyard Wind 1 blades delivered on a barge? This expensive, inefficient workaround was necessary because of a century-old law known as the Jones Act.

Also known as the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, the Jones Act requires anyone transporting goods from one point in the United States to another to use an American ship. And by a modern interpretation of the old law, an offshore turbine counts as a point in the United States. The trouble is, the United States doesn’t have any WTIVs. And without the appropriate equipment, the country’s offshore wind efforts are being plagued by the need for repeated, smaller-capacity barge trips that have added costs to projects already beset by financial difficulties. Danish energy company Ørsted, for example, cited vessel delays when it canceled two planned projects off the New Jersey coast: Ocean Wind 1 and 2.

The country’s first Jones Act–compliant WTIV, the Charybdis, is currently under construction in Texas. While originally planned for completion in 2023, labor constraints have pushed the Charybdis’s launch back at least a year, possibly into 2025, says Dominion Energy, the vessel’s owner.

The Biden administration’s goal is to deploy offshore wind turbines capable of generating 30 gigawatts of power by 2030. That’s more than 2,000 turbines. To meet this target, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), part of the US Department of Energy, says there’s a need for four to six WTIVs. But as 2030 draws ever closer, the incomplete Charybdis remains the only one.

The Jones Act is tricky to navigate. For a vessel to be compliant, it must not only be built in the United States and running the country’s flag but also be owned and crewed by Americans. Consequently, US shipyards enjoy a monopoly, which allows them to demand massively inflated prices.

When finished, the 144-meter-long Charybdis will boast over 5,000 square meters of main deck area and accommodate up to 119 people, supported by on-board cabins, mess rooms, and shops, as well as a cinema, gym, and hospital. But the WTIV’s cost has climbed from US $500 million to $625 million. Meanwhile, the major shipyards in South Korea could have built a similar vessel in less time, for less money, and with a more powerful crane.

The reason for the Jones Act’s longevity, says Colin Grabow, a research fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, is that while it tends to benefit only a few people and businesses, the act goes unnoticed because there are many payers sharing the increased costs.

The Jones Act is one in a string of protectionist laws—dating back to the Tariff Act of 1789—designed to bolster US marine industries. The Jones Act’s existence was meant to ensure a ready supply of ships and mariners in case of war. Its authors reasoned that protection from foreign competition would foster that.

“Your average American has no idea that the Jones Act even exists,” Grabow says. “It’s not life-changing for very many people,” he adds. But “all Americans are hurt by the Jones Act.” In this case, that’s by slowing down the United States’ ability to hit its own wind power targets.

Grabow says those most vocal about the law—the people who build, operate, or serve on compliant ships—usually want to keep it in place.

Of course, there’s more going on with the country’s slow rollout of offshore wind power than just a century-old shipping law. It took a slew of factors to sink New Jersey’s planned Ocean Wind installations, says Abraham Silverman, an expert on renewable energy at Columbia University in New York.

Ultimately, says Silverman, rising interest rates, inflation, and other macroeconomic factors caught New Jersey’s projects at their most vulnerable stage, inflating the construction costs after Ørsted had already locked in its financing.

Despite the setbacks, the potential for offshore wind power generation in the United States is massive. The NREL estimates that fixed-bottom offshore wind farms in the country could theoretically generate some 1,500 gigawatts of power—more than the United States is capable of generating today.

There’s a lot the United States can do to make its expansion into offshore wind more efficient. And that’s where the focus needs to be right now, says Matthew Shields, an engineer at NREL specializing in the economics and technology of wind energy.

“Whether we build 15 or 20 or 25 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030, that probably doesn’t move the needle that much from a climate perspective,” says Shields. But if building those first few turbines sets the country up to then build 100 or 200 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2050, he says, then that makes a difference. “If we have ironed out all these issues and we feel good about our sustainable development moving forward, to me, I think that’s a real win.”

But today, some of the offshore wind industry’s issues stem, inescapably, from the Jones Act. Those inefficiencies mean lost dollars and, perhaps more importantly in the rush toward carbon neutrality, lost time.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

When I was in the Navy, the littoral combat ship (LCS) was The Next Big Thing. It was going to be advanced, agile, and versatile. Twenty years later, it's a jobs program, a graveyard for sailors' careers, and how good ideas can come to a dead stop when they hit an organization.

In 2002, Admiral Clark saw a Danish warship swapping out weapons in dock. As I'm writing this blog, I'm googling it because I am suddenly curious about that. "What class of Danish ship was that?" In the wake of reading about the United States LCS system, the answer hurts. I'm putting it at the end.

Anyway, he wanted one. He wanted a small, cost-effective ship that could perform multiple duties like coastal interdiction, minesweeping, and submarine hunting.

If you've ever seen Pentagon Wars, it's basically that. You can stop reading now. I don't get paid for this.

youtube

Construction

The idea behind making something--anything--is to plan it, create a prototype, test the prototype, and then make corrections before you invest several million dollars (or in this case, several billion dollars) into making it.

But who to build it? The government sought bids to design and build the ship. Lockheed Martin put in a bid including a shipyard in Wisconsin, and General Dynamics put in one including an Alabama shipyard.

And having corporations bid for contracts is good. Each wants the contract because one is going home with a billion dollar contract (and commensurate profits) and the other is going to swallow the bitter pill of failure and go home to cry on their bed.

That is, if one gets their bitter pill. In the case of the littoral combat ship, both went home with billion dollar contracts. For two different LCS designs. A platform intended to have modular weapons.

We ordered 20.

Costs

The intention was for something cheap, $200,000,000 apiece. For 20, that's $4,000,000,000 total. But, even ignoring the performance costs I'll get into below, they ended up costing 2.5x what was expected, $500,000,000, for an estimate of $20,000,000,000 total.

I wrote out the figures above because it's easy to kind of not wrap your head around the meanings of "billions" and "millons" when they're just words. It's a good idea to put those zeroes out there so we all can compare it to our bank accounts.

That's approximately 1/13th of an Elon Musk. Or half a Twitter.

It's stupid amounts of money and it was being spent on 20 ships which had not performed a single mission.

Little Crappy Ship

And it would barely do that afterwards. I mentioned that they created prototypes and did testing. They did this concurrently with laying down the hulls. They were building the ships while they were testing if that ship design was good.

This may shock some of you, but you cannot create a warship on paper correctly the first time. Tony Stark is a cartoon genius and he still built 85 versions of the Iron Man suit. And he tested each one in his basement.

Their hulls cracked, their submarine hunting equipment (sensors, torpedoes, and helicopters) could not share data, the minehunting equipment was "too difficult" for crew to use.

Ugh. Crews. I'll get to that.

The worst part were the combining gears. I don't know what combining gears are; I was in the nuclear program so I only know about reduction gears, which turn fast, light roundy-roundy into slow, heavy roundy-roundy.

But I assume combining gears serve a similar purpose; a ship transmission turning the raw power created by the engine into power by the propellers to drive the ship.

That's all too much to say that the LCS combining gears sucked. They failed all of the time on a number of the ships. So frequently that ships could leave port on a mission, have their combining gears fail, and then immediately need a tow back to port. They'd stay there for months.

The article goes into detail about the USS Freedom (The LCS classes were the Freedom-Class and the Independence-Class, because you can say a lot of things about post-9/11 America, but it wasn't that our tone was inconsistent).

Hot on the heels of two other LCS failures, the Freedom was supposed to fly the flag for the then-flagging LCS program at Pacific Ocean naval exercises.

It had seawater in its engine oil. Obviously, water and oil do not mix and you can extrapolate from that that you do not want water where your oil goes or oil where your water goes. You don't want seawater anywhere but a beach. Fuck seawater.

They tried and failed to get the seawater out of the engine oil. They knew there was still water in the engine oil. They left port. They took that engine out of service. They completed the exercise. Three days later they were put into port for two years for the resultant repairs from seawater corrosion.

Careers Made and Ended

Oh, right. Crew training. Each ship was state of the art and used a lot of new technologies, they were demanding on crews to learn and hard to maintain. The ships were were too small to carry all of the parts they needed. Some components were NUSPI, "No User-Serviceable Parts Inside." Onboard technicians were not trained--or in the case of proprietary technologies--legally allowed to repair some of their systems. Some of the manuals weren't even in English.

How did the Freedom get seawater in her engine oil? An incorrect patch procedure. How did they crew fail to get the seawater out of the engine oil. Incorrect flushing procedure. The LCSes just weren't like any other class of ship.

And remember, there were two different classes of LCS. That meant that crews couldn't transfer their experience to a different ship and ships couldn't share parts with each other. Crews trained on LCSes had to completely relearn operations when they returned to the fleet and sailors coming from the fleet had to learn a whole new way of doing things when they were assigned to LCSes.

The answer was to silo the LCS program; sailors were transferred into the LCS program and kept in it as they advanced through the ranks. For new sailors, they'd be assigned to the LCS as their first command and spend their entire careers in it. No transfer, no problem.

To deal with the LCSes problems, crackerjack commanding officers were brought in to get results as the previous commanding officers were removed or decided to quit.

You see, a ship that's fundamentally broken and unfixable cannot be put to sea, and sailors that don't go to sea don't get promoted. It became a place where careers went to die.

In the military, they tend to say "up or out" to foster a culture of progression up the ranks. For the LCS program, there was no "up," only "out."

The Navy, realizing that parking $50 million in a port at a shipyard for two years was bonkers, tried to stop the program.

Jobs for the Jobs God

But they couldn't. They don't even need all the LCSes they have. They're retiring some, but we're still making more. Why? Why are we making more ships that can't get the mission done?!

Because we didn't burn those billions of dollars. We spent them. A lot of them did vanish into the pockets of Lockheed and General Dynamics executives, but some crumbs were sent to workers in shipyards in Wisconsin and Alabama.

Congressional representatives from those states think the LCS is a great asset in our national defense strategy. That Upton Sinclair quote is apposite:

"It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it."

The article's biggest proponent of the LCS is Ray Mabus, Secretary of the Navy under President Obama. Senator Tammy Baldwin (WI) wrote to then-President Trump to say that saving the LCS program was a way to foster bipartisan cooperation.

Despite being a huge turkey that can't do what we made it to do and wastes the all-too-rare staffing power of the US Armed Forces, it moves money from the federal government to enough American pockets that we keep making them.

Other resources:

A blog that weighs in on some of these things:

An article that includes underfunded innovation in the USN:

So, which Danish warship inspired the LCS?

It's hard to say. Danish warships have used interchangeable StanFlex modules since the 1980's.

The technology was there the whole time. All we had to do was buy it from the Danes.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

En Route to Germany (No. 13)

Construction of the Great Belt Bridge in Denmark (completed 1997) and the Øresund Bridge-Tunnel (completed 1999), linking Denmark with Sweden, provided a highway and railroad connection between Sweden and the Danish mainland (the Jutland Peninsula, precisely the Zealand). The undersea tunnel of the Øresund Bridge-Tunnel provides for navigation of large ships into and out of the Baltic Sea. The Baltic Sea is the main trade route for the export of Russian petroleum. Many of the countries neighboring the Baltic Sea have been concerned about this since a major oil leak in a seagoing tanker would be disastrous for the Baltic—given the slow exchange of water. The tourism industry surrounding the Baltic Sea is naturally concerned about oil pollution.

Much shipbuilding is carried out in the shipyards around the Baltic Sea. The largest shipyards are at Gdańsk, Gdynia, and Szczecin, Poland; Kiel, Germany; Karlskrona and Malmö, Sweden; Rauma, Turku, and Helsinki, Finland; Riga, Ventspils, and Liepāja, Latvia; Klaipėda, Lithuania; and Saint Petersburg, Russia.

There are several cargo and passenger ferries that operate on the Baltic Sea, such as Scandlines, Silja Line, Polferries, the Viking Line, Tallink, and Superfast Ferries.

Construction of the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link between Denmark and Germany is due to finish in 2029. It will be a three-bore tunnel carrying four motorway lanes and two rail tracks.

Source: Wikipedia

#MS Huckleberry Finn#TT-Line#on board a ferry#last pics from Sweden#travel#summer 2020#vacation#Baltic Sea#Ostsee#seascape#ship#car#technology#engineering#Atlantic Ocean#original photography#blue sky#smoke#tourist attraction#en route to Germany#sky#morning light#chimney#calm sea#Northern Europe#Scandinavia#Sweden#Sverige

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kraken Robotics Minehunting Systems Operational with Royal Danish Navy

Kraken Robotics Inc. is pleased to announce the completion of all deliveries and the successful sea acceptance of all systems for its mine-hunting sonar equipment under the Royal Danish Navy Minehunting sonar upgrade program. This contract was signed in September 2020, following a competitive bidding process. Under the contract with the Danish Ministry of Defence Acquisition and Logistics Organization (DALO), Kraken has delivered four complete turnkey mine-hunting systems, with each system consisting of a KATFISH™ towed Synthetic Aperture Sonar, Tentacle® Winch and Autonomous Launch and Recovery System (ALARS), topside command and control equipment, and remote operation and monitoring capability for standoff mine-hunting operations. Starting in 2022, the KATFISH mine-hunting systems were integrated onboard the Royal Danish Navy’s optionally uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), the MSF-class. Kraken worked closely with MCM Denmark operators and workshop technicians as well as skilled local Danish shipyard, JOBI, to install Kraken’s DNV design approved Autonomous Launch and Recovery System (ALARS) onto the MSF-class in parallel with the MSF-class planned mid-life refit. Kraken also integrated the KATFISH system with Saab’s Command and Control (C2) software, providing operators with a seamless experience for mission planning and mission monitoring. The inclusion of Kongsberg’s Maritime Broadband Radio (MBR) enables the complete system to operate remotely, streaming full resolution sonar imagery in real-time at ranges exceeding line of sight.

Kraken Robotics Inc. is pleased to announce the completion of all deliveries and the successful sea acceptance of all systems for its mine-hunting sonar equipment under the Royal Danish Navy Minehunting sonar upgrade program. This contract was signed in September 2020, following a competitive bidding process. Under the contract with the Danish Ministry of Defence Acquisition and Logistics…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

P.S. Krøyer - From Fra Burmeister og Wain's Iron Foundry, 1885, oil on canvas Peder Severin Krøyer (1851 – 1909) was a Norweigian painter who was masterful at capturing natural light. He liked to paint romantic landscapes and figurative paintings. Krøyer also made sculptures and engravings. Krøyer was born in Stavanger, Norway, but was raised by his uncle and auntie in Copenhagen. Krøyer was only nine years old when he began formal painting lessons. He graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen at the young age of 19 years. Krøyer started his career by painting portraits for commision. Krøyer travelled abroad frequently, often to Paris. Krøyer loved visiting an artists' colony in the remote fishing village of Skagen, Denmark.

#P.S. Krøyer#Peder Severin Krøyer#ps kroyer#iron foundry#denmark#shipyard#danish shipyard#Norweigian painter#interior painting#oil on canvas oil painting#Copenhagen#Burmeister & Wain#burmeister wain#impressionism#naturalism#realism#workers#foundry#foundry workers#1885#1880s#nineteenth century#industrial#insutrial painting#historical painting

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

yours to tame

ship: captain hook | killian jones / peter pan rating: explicit a/n: this is set in a very specific au featuring peter and killian in the first curse, but i don’t want to give too much away in case i wind up doing more with this au

+ + + + + + + + + + + + + +

Chapped hands cup the cardboard sleeve around his caramel mocha as Peter gets up from his darkened location in the back of Storybrooke Coffee Co. Boot laces caked with salt and sand, he steps over to his target. Killian sits with his back to him — either he’s feeling brave or he hasn’t seen him. More likely the latter.

After texting him this morning, he’d half expected to have to go down to the shipyard to drag Killian out of the Jolly Roger himself. But he’d finally gotten a begrudging one-word response, and he knew where he’d find him. Peter knows Storybrooke Coffee Co. the only place that Killian will voluntarily go for coffee, since Granny’s Diner is all but guaranteed to be swimming with local government, school teachers, sheriffs, and a whole manner of people he doesn’t want to interact with. Peter also happens to score cheaper coffee here, as a few of his friends work as baristas.

He sets an artificially warm hand at the back of Killian’s neck, feeling the chilled chains of his many necklaces which adorn his throat. It’s a bold gesture for them in public, but Peter doesn’t care. He never did – it was Killian who made up these rules, protecting them from nosy PTA moms and their even nosier kids.

“Good morning to you,” he murmurs, sliding around to take a seat across from Killian, hand still on his neck until the last possible moment. Bottle-green eyes assess the hungover man, taking in the haggard look in his gaze, the way he seems half-torn, ripped a little before someone could fully commit to it. Peter clicks his tongue and tilts his head, bottom lip slightly pushed out. “Someone’s had a rough night.”

Killian shifts, working his jaw as icy blue eyes follow Peter into his seat.

“Every night is a rough night,” he responds quietly. He nudges a plate forward with his knuckles, passing it across the table to Peter. “Raspberry and cream cheese danish.” He punctuates the sentence with a swig of his own coffee. There’s little doubt in Peter’s mind that Killian wishes it were Irish coffee at this moment.

“You should really see someone about that,” he murmurs with no intention of stopping Killian’s self-destructive habits. If he truly wanted to, he’d take himself out of the sailor’s life. He’s not benevolent.

“And you’re generous, offering me your – what day is it? Thursday? – Thursday morning treat.” He accepts it, hardly one to turn down something free and sugary. The danish is the tiniest bit stale, but enough mocha in his mouth has it literally melting, and that’s good enough for him. “Someone wake up on the right side of the hammock this morning?”

As he speaks, he stretches out his legs beneath the table, until their booted ankles brush. He leans his legs against Killian’s, as if daring him to pull away.

Killian hesitates, freezes, and Peter grins around his next sip. He watches the conflict spill across his features, winter sunlight sharpening the hard edges of his face, and feels the warm slide of denim against cotton as Killian pulls his legs back.

“Just hungover,” Killian clarifies, eyeing Peter as he enjoys his morning treat. “Why did you text me this morning? Shouldn’t you be out spray-painting buildings and getting into trouble, since you’re clearly not in school.”

Peter raises a tawny brow. “I’m bored. And I haven’t been in school for weeks, you know this.” So the story goes, having decided college was too much of a bore for him, he quietly dropped out and landed in Storybrooke, away from his parents and anyone who knew him. Then he proceeded to lay out his own network, re-establishing himself

( not that Killian would know, not that Killian would remember )

until he found someone who would rent to him, thus securing his own place.

He stretches out his leg a little bit further, brushing the toe of his boot against Killian’s shin, green eyes cold and hard all of a sudden. He doesn’t mind causing a bit of a scene here – Killian took the bait and withdrew, and now he has to show him the consequences to those actions.

“Peter…” But the helplessness is clear in Killian’s tone, and Peter preens, even as the sailor softly commands, “Stop.”

He pulls back further, tucking his legs beneath his chair as he takes another swig from his coffee. “You can’t do that here. When we’re alone, fine, but not in public.”

“And why is that?” Peter asks, brows furrowed. He tilts his head, side swept hair barely visible beneath a black beanie – stolen from Killian about two weeks ago and not yet given back, if it ever would be. “Tell me, Killian. Why is that? you let me into your boat, into your bed, and yet —”

“Because those places are private, Peter,” Killian interrupts, and oh how Peter tires of this man’s blind confidence. “I barely want people knowing I exist, much less that I’m fooling around with a 19-year-old college drop out.” His next words are softer, almost pleading, and it helps to assuage Peter’s raised hackles.

“I can’t have you doing this in public, mate.”

“You run from the truth as if it will save you, but you’re so blinded by it you have no idea where you’re going, nor what it is, exactly, that you’re running from.” The words, spoken in a low murmur, carry across the table, punctuated with a sip of his drink. Killian truthfully does have no idea, not that Peter is going to be the one to break it to him. He’s not got his ducks quite in a row yet – but once the flock returns to roost, he’ll be ready and waiting.

For now, he crosses one leg over the other, staring into kohl lined eyes, waiting for Killian to dig himself deeper.

“…You’re awfully cryptic this morning,” he murmurs back, watching Peter. “Just…drink your sugar water and let’s get out of here.”

Defiantly, he stands with the mocha still mostly full, with the other half of the danish in his other hand. “Follow me,” he says, and proceeds to weave through the coffee shop goers, heading towards the door. Freezing cold air greets him as he steps outside, frozen kisses against his cheeks and nose, and he buries them into the scarf he’s wearing – another thing stolen from Killian.

Read the rest here!

#ouat#once upon a time#killian jones#peter pan#captain pan#which i always miswrite as captain pain and ykw that's not entirely wrong#anyway trying a new format with advertising my fics on here#a partial crossposting sounds good enough#the crownless king

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apr 27 in WWI

April 27 1918 A French official photographer takes this photo, IWM Q 93250, of a British officer examining a French St. Etienne Mle 1907 machine gun at the School of Machine Gunners at Fere-en-Tardenois.

Apr 27 1918 A US official photographer takes this photo, IWM Q 93185, of black American soldiers, cooks of the hospital train No. 54, at Horreville.

27 April 1918-04-27

New-York Tribune Apr 27 1919

Twin Debutants; Made in U.S.A. John C Jahansen (Danish Artist, November 25, 1876 – May 23, 1964)

The artist, who painted more than a score of pictures in Government-owned shipyards during the war, has depicted here two excellent reasons for the further development of our merchant marine. These ships will presently go, figuratively if not literally, "rolling down to Rio, Singapore, Antofagasta or Port Said – far ports from which our merchant flag has been too long absent.

.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

#københavn#reffen#simon#danish#denmark#Refshaleøen#visit copenhagen#amager#shipyard#harbor#industrial zone#copenhell

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

• KMS Bismarck

Bismarck was the first of two Bismarck-class battleships built for Nazi Germany's Kriegsmarine. Named after Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the ship was laid down at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg in July 1936 and launched in February 1939.

The two Bismarck-class battleships were designed in the mid-1930s by the German Kriegsmarine as a counter to French naval expansion, specifically the two Richelieu-class battleships France had started in 1935. Laid down after the signing of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, Bismarck and her sister Tirpitz were nominally within the 35,000-long-ton (36,000 t) limit imposed by the Washington regime that governed battleship construction in the interwar period. The ships secretly exceeded the figure by a wide margin, though before either vessel was completed, the international treaty system had fallen apart following Japan's withdrawal in 1937, allowing signatories to invoke an "escalator clause" that permitted displacements.

Bismarck displaced 41,700 t (41,000 long tons) as built and 50,300 t (49,500 long tons) fully loaded, with an overall length of 251 m (823 ft 6 in), a beam of 36 m (118 ft 1 in) and a maximum draft of 9.9 m (32 ft 6 in). The battleship was Germany's largest warship, and displaced more than any other European battleship, with the exception of HMS Vanguard, commissioned after the end of the war. Bismarck was powered by three Blohm & Voss geared steam turbines and twelve oil-fired Wagner superheated boilers, which developed a total of 148,116 shp (110,450 kW) and yielded a maximum speed of 30.01 knots (55.58 km/h; 34.53 mph) on speed trials. Bismarck was equipped with three FuMO 23 search radar sets, mounted on the forward and stern rangefinders and foretop. The standard crew numbered 103 officers and 1,962 enlisted men.[7] The crew was divided into twelve divisions of between 180 and 220 men. The first six divisions were assigned to the ship's armament, divisions one to four for the main and secondary batteries and five and six manning anti-aircraft guns. The seventh division consisted of specialists, including cooks and carpenters, and the eighth division consisted of ammunition handlers. The radio operators, signalmen, and quartermasters were assigned to the ninth division. The last three divisions were the engine room personnel. When Bismarck left port, fleet staff, prize crews, and war correspondents increased the crew complement to over 2,200 men.

Bismarck was armed with eight 38 cm (15 in) SK C/34 guns arranged in four twin gun turrets: two super-firing turrets forward "Anton" and "Bruno" and two aft "Caesar" and "Dora". Secondary armament consisted of twelve 15 cm (5.9 in) L/55 guns, sixteen 10.5 cm (4.1 in) L/65 and sixteen 3.7 cm (1.5 in) L/83, and twelve 2 cm (0.79 in) anti-aircraft guns. Bismarck also carried four Arado Ar 196 reconnaissance floatplanes in a double hangar amidships and two single hangars abreast the funnel, with a double-ended thwartship catapult. The ship's main belt was 320 mm (12.6 in) thick and was covered by a pair of upper and main armoured decks that were 50 mm (2 in) and 100 to 120 mm (3.9 to 4.7 in) thick, respectively. The 38 cm (15 in) turrets were protected by 360 mm (14.2 in) thick faces and 220 mm (8.7 in) thick sides.

Bismarck was ordered under the name Ersatz Hannover ("Hannover replacement"), a replacement for the old pre-dreadnought SMS Hannover. The contract was awarded to the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg, where the keel was laid on July 1st, 1936 at Helgen IX. The ship was launched on February 14th, 1939 and during the elaborate ceremonies was christened by Dorothee von Löwenfeld, granddaughter of Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the ship's namesake. Adolf Hitler made the christening speech. Bismarck was commissioned into the fleet on August 24th, 1940 for sea trials, which were conducted in the Baltic. Kapitän zur See Ernst Lindemann took command of the ship at the time of commissioning. On September 15th, 1940, three weeks after commissioning, Bismarck left Hamburg to begin sea trials in Kiel Bay. Sperrbrecher 13 escorted the ship to Arcona on September 28th, and then on to Gotenhafen for trials in the Gulf of Danzig. The ship's power-plant was given a thorough workout; Bismarck made measured-mile and high speed runs. As the ship's stability and manoeuvrability were being tested, a flaw in her design was discovered. When attempting to steer the ship solely through altering propeller revolutions, the crew learned that Bismarck could be kept on course only with great difficulty. Even with the outboard screws running at full power in opposite directions, they generated only a slight turning ability. Bismarck's main battery guns were first test-fired in late November. The tests proved she was a very stable gun platform. Trials lasted until December; Bismarck returned to Hamburg, arriving on the 9th, for minor alterations and the completion of the fitting-out process.

The ship was scheduled to return to Kiel on January 24th, 1941, but a merchant vessel had been sunk in the Kiel Canal and prevented use of the waterway. Severe weather hampered efforts to remove the wreck, and Bismarck was not able to reach Kiel until March. While waiting to reach Kiel, Bismarck hosted Captain Anders Forshell, the Swedish naval attaché to Berlin. He returned to Sweden with a detailed description of the ship, which was subsequently leaked to Britain by pro-British elements in the Swedish Navy. The information provided the Royal Navy with its first full description of the vessel, although it lacked important facts, including top speed, radius of action, and displacement. At 08:45 on March 8th, Bismarck briefly ran aground on the southern shore of the Kiel Canal; she was freed within an hour. The ship reached Kiel the following day, where her crew stocked ammunition, fuel, and other supplies and applied a coat of dazzle paint to camouflage her. British bombers attacked the harbour without success on the 12th.

The Naval High Command (Oberkommando der Marine or OKM), commanded by Admiral Erich Raeder, intended to continue the practice of using heavy ships as surface raiders against Allied merchant traffic in the Atlantic Ocean. The two Scharnhorst-class battleships were based in Brest, France, at the time, having just completed Operation Berlin, a major raid into the Atlantic. Bismarck's sister ship Tirpitz rapidly approached completion. Bismarck and Tirpitz were to sortie from the Baltic and rendezvous with the two Scharnhorst-class ships in the Atlantic; the operation was initially scheduled for around April 25th, 1941. Admiral Günther Lütjens, Flottenchef (Fleet Chief) of the Kriegsmarine, chosen to lead the operation, wished to delay the operation at least until either Scharnhorst or Tirpitz became available, but the OKM decided to proceed with the operation, codenamed Operation Rheinübung, with a force consisting of only Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. At a final meeting with Raeder in Paris on April 26th, Lütjens was encouraged by his commander-in-chief to proceed and he eventually decided that an operation should begin as soon as possible.

On May 5th, 1941, Hitler and Wilhelm Keitel, with a large entourage, arrived to view Bismarck and Tirpitz in Gotenhafen. The men were given an extensive tour of the ships, after which Hitler met with Lütjens to discuss the upcoming mission. On May 16th, Lütjens reported that Bismarck and Prinz Eugen were fully prepared for Operation Rheinübung; he was therefore ordered to proceed with the mission on the evening of the 19th. As part of the operational plans, a group of eighteen supply ships would be positioned to support Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. Four U-boats would be placed along the convoy routes between Halifax and Britain to scout for the raiders. By the start of the operation, Bismarck's crew had increased to 2,221 officers and enlisted men. This included an admiral's staff of nearly 65 and a prize crew of 80 sailors, who could be used to crew transports captured during the mission. At 02:00 on May 19th, Bismarck departed Gotenhafen and made for the Danish straits. The Luftwaffe provided air cover during the voyage out of German waters. At around noon on May 20th, Lindemann informed the ship's crew via loudspeaker of the ship's mission. At approximately the same time, a group of ten or twelve Swedish aircraft flying reconnaissance encountered the German force and reported its composition and heading, though the Germans did not see the Swedes. Code-breakers at Bletchley Park had confirmed that an Atlantic raid was imminent, as they had decrypted reports that Bismarck and Prinz Eugen had taken on prize crews and requested additional navigational charts from headquarters. A pair of Supermarine Spitfires was ordered to search the Norwegian coast for the flotilla.

German aerial reconnaissance confirmed that one aircraft carrier, three battleships, and four cruisers remained at anchor in the main British naval base at Scapa Flow, which confirmed to Lütjens that the British were unaware of his operation. On the evening of May 20th, Bismarck and the rest of the flotilla reached the Norwegian coast. The following morning, radio-intercept officers on board Prinz Eugen picked up a signal ordering British reconnaissance aircraft to search for two battleships and three destroyers northbound off the Norwegian coast. At 7:00 on the 21st, the Germans spotted four unidentified aircraft, which quickly departed. When Bismarck was in Norway, a pair of Bf 109 fighters circled overhead to protect her from British air attacks, but a Spitfire was able to fly directly over the German flotilla at a height of 8,000 m (26,000 ft) and take photos of Bismarck and her escorts. Upon receipt of the information, Admiral John Tovey ordered the battlecruiser HMS Hood, the newly commissioned battleship HMS Prince of Wales, and six destroyers to reinforce the pair of cruisers patrolling the Denmark Strait. The rest of the Home Fleet was placed on high alert in Scapa Flow. Bismarck did not replenish her fuel stores in Norway, as her operational orders did not require her to do so. She had left port 200 t (200 long tons) short of a full load, and had since expended another 1,000 t (980 long tons) on the voyage. At midnight, when the force was in the open sea, heading towards the Arctic Ocean, Raeder disclosed the operation to Hitler, who reluctantly consented to the raid. The three escorting destroyers were detached at 04:14 on May 22nd, while the force steamed off Trondheim. At around 12:00, Lütjens ordered his two ships to turn toward the Denmark Strait to attempt the break-out into the open Atlantic. Upon entering the Strait, both ships activated their FuMO radar detection equipment sets. Around 12:00, the pair had reached a point north of Iceland. Prinz Eugen's radio-intercept team decrypted the radio signals being sent by Suffolk and learned that their location had been reported.

Lütjens gave permission for Prinz Eugen to engage Suffolk, but the captain of the German cruiser could not clearly make out his target and so held fire. Suffolk quickly retreated to a safe distance and shadowed the German ships. At 20:30, the heavy cruiser HMS Norfolk joined Suffolk, but approached the German raiders too closely. Lütjens ordered his ships to engage the British cruiser; Bismarck fired five salvoes, three of which straddled Norfolk and rained shell splinters on her decks. The cruiser laid a smoke screen and fled into a fog bank, ending the brief engagement. At 05:07, hydrophone operators aboard Prinz Eugen detected a pair of unidentified vessels approaching the German formation at a range of 20 nmi (37 km; 23 mi). At 05:45 on May 24th, German lookouts spotted smoke on the horizon; this turned out to be from Hood and Prince of Wales, under the command of Vice Admiral Lancelot Holland. Lütjens ordered his ships' crews to battle stations. By 05:52, the range had fallen to 26,000 m (28,000 yd) and Hood opened fire, followed by Prince of Wales a minute later. Hood engaged Prinz Eugen, which the British thought to be Bismarck, while Prince of Wales fired on Bismarck.

The British ships approached the German ships head on, which permitted them to use only their forward guns; Bismarck and Prinz Eugen could fire full broadsides. Several minutes after opening fire, Holland ordered a 20° turn to port, which would allow his ships to engage with their rear gun turrets. Both German ships concentrated their fire on Hood. Prinz Eugen scored a hit with a high-explosive 20.3 cm (8.0 in) shell; the explosion detonated unrotated projectile ammunition and started a large fire, which was quickly extinguished. Lütjens ordered Prinz Eugen to shift fire and target Prince of Wales, to keep both of his opponents under fire. Within a few minutes, Prinz Eugen scored a pair of hits on the battleship that started a small fire. Lütjens then ordered Prinz Eugen to drop behind Bismarck, so she could continue to monitor the location of Norfolk and Suffolk, which were still 10 to 12 nmi (19 to 22 km; 12 to 14 mi) to the east. At 06:00, Hood was completing the second turn to port when Bismarck's fifth salvo hit. Two of the shells landed short, striking the water close to the ship, but at least one of the 38 cm armour-piercing shells struck Hood and penetrated her thin deck armour. The shell reached Hood's rear ammunition magazine and detonated 112 t (110 long tons) of cordite propellant. The massive explosion broke the back of the ship between the main mast and the rear funnel; the forward section continued to move forward briefly before the in-rushing water caused the bow to rise into the air at a steep angle. The stern also rose as water rushed into the ripped-open compartments. In only eight minutes of firing, Hood had disappeared, taking all but three of her crew of 1,419 men with her. Bismarck then shifted fire to Prince of Wales. The British battleship scored a hit on Bismarck with her sixth salvo, but the German ship found her mark with her first salvo. One of the shells struck the bridge on Prince of Wales, though it did not explode and instead exited the other side, killing everyone in the ship's command centre, save Captain John Leach, the ship's commanding officer, and one other. The two German ships continued to fire upon Prince of Wales, causing serious damage. Guns malfunctioned on the recently commissioned British ship, which still had civilian technicians aboard. Prince of Wales scored three hits on Bismarck in the engagement. The first struck her in the forecastle above the waterline but low enough to allow the crashing waves to enter the hull. The second shell struck below the armoured belt and exploded on contact with the torpedo bulkhead, completely flooding a turbo-generator room and partially flooding an adjacent boiler room. The third shell passed through one of the boats carried aboard the ship and then went through the floatplane catapult without exploding.

At 06:13, Prince of Wales made a 160° turn and laid a smoke screen to cover her withdrawal. The Germans ceased fire as the range widened. Lütjens obeyed operational orders to shun any avoidable engagement with enemy forces that were not protecting a convoy, and the Bismarck and Prinz Eugen headed for the North Atlantic. In the engagement, Bismarck had fired 93 armour-piercing shells and had been hit by three shells in return. After the engagement, Lütjens reported, "Battlecruiser, probably Hood, sunk. Another battleship, King George V or Renown, turned away damaged. Two heavy cruisers maintain contact." At 08:01, he transmitted a damage report and his intentions to OKM, which were to detach Prinz Eugen for commerce raiding and to make for Saint-Nazaire for repairs. Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered all warships in the area to join the pursuit of Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. Tovey's Home Fleet was steaming to intercept the German raiders, but on the morning of May 24th was still over 350 nmi (650 km; 400 mi) away. The Admiralty ordered the light cruisers Manchester, Birmingham, and Arethusa to patrol the Denmark Strait in the event that Lütjens attempted to retrace his route. In all, six battleships and battlecruisers, two aircraft carriers, thirteen cruisers, and twenty-one destroyers were committed to the chase. With the weather worsening, Lütjens attempted to detach Prinz Eugen at 16:40. The cruiser was successfully detached at 18:14. Seeing Bismarck, Prince of Wales fired twelve salvos at Bismarck, which responded with nine salvos, none of which hit. The action diverted British attention and permitted Prinz Eugen to slip away. Although Bismarck had been damaged in the engagement and forced to reduce speed, she was still capable of reaching 27 to 28 knots (50 to 52 km/h; 31 to 32 mph), the maximum speed of Tovey's King George V. Unless Bismarck could be slowed, the British would be unable to prevent her from reaching Saint-Nazaire. Shortly before 16:00 on May 25th, Tovey detached the aircraft carrier Victorious and four light cruisers to shape a course. At 22:00, Victorious launched the strike, which comprised six Fairey Fulmar fighters and nine Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers. Bismarck also used her main and secondary batteries to fire at maximum depression to create giant splashes in the paths of the incoming torpedo bombers. None of the attacking aircraft were shot down. Bismarck evaded eight of the torpedoes launched at her, but the ninth struck amidships on the main armoured belt, throwing one man into a bulkhead and killing him and injuring five others. The explosion also caused minor damage to electrical equipment. The ship suffered more serious damage from manoeuvres to evade the torpedoes: rapid shifts in speed and course loosened collision mats, which increased the flooding from the forward shell hole and eventually forced abandonment of the port number 2 boiler room. This loss of a second boiler, combined with fuel losses and increasing bow trim, forced the ship to slow to 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph).

Shortly after the Swordfish departed from the scene, Bismarck and Prince of Wales engaged in a brief artillery duel. Neither scored a hit. Bismarck's damage control teams resumed work after the short engagement. The sea water that had flooded the number 2 port side boiler threatened to enter the number 4 turbo-generator feedwater system, which would have permitted saltwater to reach the turbines. The saltwater would have damaged the turbine blades and thus greatly reduced the ship's speed. By morning, the danger had passed. As the chase entered open waters, British ships were compelled to zig-zag to avoid German U-boats that might be in the area. At 03:00 on May 25th, Lütjens ordered an increase to maximum speed, which at this point was 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). He then ordered the ship to circle away to the west and then north. This manoeuvre coincided with the period during which his ship was out of radar range; Bismarck successfully broke radar contact and circled back behind her pursuers. The Royal Navy search became frantic, as many of the British ships were low on fuel. Victorious and her escorting cruisers were sent west, other British ships continued to the south and west, and Tovey continued to steam toward the mid-Atlantic. British code-breakers were able to decrypt some of the German signals, including an order to the Luftwaffe to provide support for Bismarck making for Brest. Tovey could now turn his forces toward France to converge in areas through which Bismarck would have to pass. Victorious, Prince of Wales, Suffolk and Repulse were forced to break off the search due to fuel shortage; the only heavy ships remaining apart from Force H were King George V and Rodney, but they were too distant.

HMS Ark Royal's Swordfish were already searching nearby when the Bismarck was found. Several torpedo bombers also located the battleship, about 60 nmi (110 km; 69 mi) away from Ark Royal. Somerville ordered an attack as soon as the Swordfish returned and were rearmed with torpedoes. As a result, the Swordfish, which were armed with torpedoes equipped with new magnetic detonators. Upon returning to Ark Royal, the Swordfish loaded torpedoes equipped with contact detonators. The attack comprised fifteen aircraft and was launched at 19:10. At 20:47, the torpedo bombers began their attack descent through the clouds. The Swordfish then attacked; Bismarck began to turn violently as her anti-aircraft batteries engaged the bombers. One torpedo hit amidships on the port side, just below the bottom edge of the main armour belt. The force of the explosion was largely contained by the underwater protection system and the belt armour but some structural damage caused minor flooding. The second torpedo struck Bismarck in her stern on the port side, near the port rudder shaft. The coupling on the port rudder assembly was badly damaged and the rudder became locked in a 12° turn to port. The explosion also caused much shock damage. The crew eventually managed to repair the starboard rudder but the port rudder remained jammed. With the port rudder jammed, Bismarck was now steaming in a large circle, unable to escape from Tovey's forces. Though fuel shortages had reduced the number of ships available to the British, the battleships King George V and Rodney were still available, along with the heavy cruisers Dorsetshire and Norfolk. Lütjens signalled headquarters at 21:40 on the 26th: "Ship unmanoeuvrable. We will fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer." As darkness fell, Bismarck briefly fired on Sheffield, though the cruiser quickly fled. Sheffield lost contact in the low visibility and Captain Philip Vian's group of five destroyers was ordered to keep contact with Bismarck through the night. The ships encountered Bismarck at 22:38; the battleship quickly engaged them with her main battery. After firing three salvos, she straddled the Polish destroyer ORP Piorun. The destroyer continued to close the range until a near miss at around 12,000 m (39,000 ft) forced her to turn away. Between 05:00 and 06:00, Bismarck's crew attempted to launch one of the Arado 196 float planes to carry away the ship's war diary, footage of the engagement with Hood, and other important documents. As it was not possible to launch the aircraft, it had become a fire hazard, and was pushed overboard.

After daybreak on May 27th, King George V led the attack. Rodney followed off her port quarter; Tovey intended to steam directly at Bismarck until he was about 8 nmi (15 km; 9.2 mi) away. At 08:43, lookouts on King George V spotted her, some 23,000 m (25,000 yd) away. Four minutes later, Rodney's two forward turrets, comprising six 16 in (406 mm) guns, opened fire, then King George V's 14 in (356 mm) guns began firing. Bismarck returned fire at 08:50 with her forward guns; with her second salvo, she straddled Rodney. Thereafter, Bismarck's ability to aim her guns deteriorated as the ship, unable to steer, moved erratically in the heavy seas. As the range fell, the ships' secondary batteries joined the battle. Norfolk and Dorsetshire closed and began firing with their 8 in (203 mm) guns. At 09:02, a 16-inch shell from Rodney struck Bismarck's forward superstructure, killing hundreds of men and severely damaging the two forward turrets. According to survivors, this salvo probably killed Lütjens and the rest of the bridge staff. A second shell from this salvo struck the forward main battery, which was disabled, though it would manage to fire one last salvo at 09:27. Lieutenant von Müllenheim-Rechberg, in the rear control station, took over firing control for the rear turrets. He managed to fire three salvos before a shell destroyed the gun director, disabling his equipment. He gave the order for the guns to fire independently, but by 09:31, all four main battery turrets had been put out of action. One of Bismarck's shells exploded 20 feet off Rodney's bow and damaged her starboard torpedo tube—the closest Bismarck came to a direct hit on her opponents. With the bridge personnel no longer responding, the executive officer CDR Hans Oels took command of the ship from his station at the Damage Control Central. He decided at around 09:30 to abandon and scuttle the ship to prevent Bismarck being boarded by the British, and to allow the crew to abandon ship so as to reduce casualties. Gerhard Junack, the chief engineering officer, ordered his men to set the demolition charges with a 9-minute fuse but the intercom system broke down and he sent a messenger to confirm the order to scuttle the ship. The messenger never returned, so Junack primed the charges and ordered his men to abandon ship. By 10:00, Tovey's two battleships had fired over 700 main battery shells, many at very close range. Overall the four British ships fired more than 2,800 shells at Bismarck, and scored more than 400 hits, but were unable to sink Bismarck by gunfire. The heavy gunfire at virtually point-blank range devastated the superstructure and the sections of the hull that were above the waterline, causing very heavy casualties, but it contributed little to the eventual sinking of the ship.

The scuttling charges detonated around 10:20. By 10:35, the ship had assumed a heavy port list, capsizing slowly and sinking by the stern. At around 10:20, running low on fuel, Tovey ordered the cruiser Dorsetshire to sink Bismarck with torpedoes and ordered his battleships back to port. Dorsetshire fired a pair of torpedoes into Bismarck's starboard side, one of which hit. Dorsetshire then moved around to her port side and fired another torpedo, which also hit. By the time these torpedo attacks took place, the ship was already listing so badly that the deck was partly awash. Bismarck had been reduced to a shambles, aflame from stem to stern. She was slowly settling by the stern from uncontrolled flooding with a 20 degree list to port. Bismarck disappeared beneath the surface at 10:40. Around 400 men were now in the water; Dorsetshire and the destroyer Maori moved in and lowered ropes to pull the survivors aboard. At 11:40, Dorsetshire's captain ordered the rescue effort abandoned after lookouts spotted what they thought was a U-boat. Dorsetshire had rescued 85 men and Maori had picked up 25 by the time they left the scene. A U-boat later reached the survivors and found three men, and a German trawler rescued another two. One of the men picked up by the British died of his wounds the following day. Out of a crew of over 2,200 men, only 114 survived. The wreck of Bismarck was discovered on June 8th, 1989 by Dr. Robert Ballard, the oceanographer responsible for finding RMS Titanic. Bismarck was found to be resting on its keel at a depth of approximately 4,791 m (15,719 ft), about 650 km (400 mi) west of Brest.

#second world war#world war ii#world war 2#military history#wwii#history#german history#british history#bismarck#long post#kriegsmarine#naval history#naval warfare#battleship

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

"One of the rare glimmers of humanity and reason in the detailed history of Eichmann's patient labors to exterminate the Jews, as recorded by Hannah Arendt's recent series of articles in The New Yorker, was the nonviolent resistance offered by the entire nation of Denmark against Nazi power mobilized for genocide.

Denmark was not the only European nation that disagreed with Hitler on this point. But it was one of the only nations which offered explicit, formal and successful nonviolent resistance to Nazi power. The adjectives are important. The resistance was successful because it was explicit and formal, and because it was practically speaking unanimous. The entire Danish nation simply refused to cooperate with the Nazis, and resisted every move of the Nazis against the Jews with nonviolent protest of the highest and most effective caliber, yet without any need for organization, training, or specialized activism: simply by unanimously and effectively expressing in word and action the force of their deeply held moral convictions. These moral convictions were nothing heroic or sublime. They were merely ordinary.

There had of course been subtle and covert refusals on the part of other nations. Italians in particular, while outwardly complying with Hitler's policy, often arranged to help the Jews evade capture or escape from unlocked freight cars. The Danish nation, from the King on down, formally and publically rejected the policy and opposed it with an open, calm, convinced resistance which shook the morale of the German troops and SS men occupying the country and changed their whole outlook on the Jewish question.

When the Germans first approached the Danes about the segregation of Jews, proposing the introduction of the yellow badge, the government officials replied that the King of Denmark would be the first to wear the badge, and that the introduction of any anti-Jewish measures would lead immediately to their own resignation.

At the same time, the Danes refused to make any distinction between Danish and non-Danish Jews. That is to say, they took the German Jewish refugees under their protection and refused to deport them back to Germany — an act which considerably disrupted the efficiency of Eichmann's organization and delayed anti-Jewish operations in Denmark until 1943 when Hitler personally ordered that the 'final solution' go into effect without further postponement.

The Danes replied by strikes, by refusals to repair German ships in their shipyards, and by demonstrations of protest. The Germans then imposed martial law. But now it was realized that the German officials in Denmark were changed men. They could 'no longer be trusted.' They refused to cooperate in the liquidation of the Jews, not of course by open protest, but by delays, evasions, covert refusals and the raising of bureaucratic obstacles. Hence Eichmann was forced to send a 'specialist' to Denmark, at the same time making a concession of monumental proportions: all the Jews from Denmark would go only to Theresienstadt, a 'soft' camp for privileged Jews. Finally, the special police sent direct from Germany to round up the Jews were warned by the SS officers in Denmark that Danish police would probably forcibly resist attempts to take the Jews away by force, and that there was to be no fighting between Germans and Danes.

Meanwhile the Jews themselves had been warned and most of them had gone into hiding, helped, of course, by friendly Danes: then wealthy Danes put up money to pay for transportation of nearly six thousand Jews to Sweden, which offered them asylum, protection and the right to work. Hundreds of Danes cooperated in ferrying Jews to Sweden in small boats. Half the Danish Jews remained safely in hiding in Denmark during the rest of the war. About five hundred Jews who were actually arrested in Denmark went to Theresienstadt and lived under comparatively good conditions: only forty-eight of them died, mostly of natural causes.

Denmark was certainly not the only European nation that disapproved more or less of the 'solution' which Hitler had devised for the Judenfrage. But it was the only nation which, as a whole, expressed a forthright moral objection to this policy. Other nations kept their disapproval to themselves. They felt it was enough to offer the Jews 'heartfelt sympathy,' and, in many individual cases, tangible aid. But let us not forget that generally speaking the practice was to help the Jew at considerable profit to oneself. How many Jews in France, Holland, Hungary, etc., paid fortunes for official permits, bribes, transportation, protection, and still did not escape!

The whole Eichmann story, as told by Hannah Arendt (indeed as told by anybody) acquires a quality of hallucinatory awfulness from the way in which we see how people in many ways exactly like ourselves, claiming as we do to be Christians or at least to live by humanistic standards which approximate, in theory, to the Christian ethic, were able to rationalize a conscious, uninterrupted and complete cooperation in activities which we now see to have been not only criminal but diabolical. Most of the rationalizing probably boiled down to the usual half-truths: 'What can you do? There is no other way out, it is a necessary evil. True, we recognize this kind of action to be in many ways unpleasant. We hate to have to take measures like these: but then those at the top know best. It is for the common good. The individual conscience has to be overruled when the common good is at stake. Our duty is to obey. The responsibility for these measures rests on others. . . and so on.'

Curiously, the Danish exception, while relieving the otherwise unmitigated horror of the story, actually adds to the nightmarish and hallucinated effect of incredulousness one gets while reading it. After all, the Danes were not even running a special kind of nonviolent movement. They were simply acting according to ordinary beliefs which everybody in Europe theoretically possessed, but which, for some reason, nobody acted on. Quite the contrary! Why did a course of action which worked so simply and so well in Denmark not occur to all the other so-called Christian nations of the West just as simply and just as spontaneously?

Obviously there is no simple answer. It does not even necessarily follow that the Danes are men of greater faith or deeper piety than other western Europeans. But perhaps it is true that these people had been less perverted and secularized by the emptiness and cynicism, the thoughtlessness, the crude egoism and the rank amorality which have become characteristic of our world, even where we still see an apparent surface of Christianity. It is not so much that the Danes were Christians, as that they were human. How many others were even that?

The Danes were able to do what they did because they were able to make decisions that were based on clear convictions about which they all agreed and which were in accord with the inner truth of man's own rational nature, as well as in accordance with the fundamental law of God in the Old Testament as well as in the Gospel: thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself. The Danes were able to resist the cruel stupidity of Nazi anti-Semitism because this fundamental truth was important to them. And because they were willing, in unanimous and concerted action, to stake their lives on this truth. In a word, such action becomes possible where fundamental truths are taken seriously."

- Thomas Merton, "Danish Nonviolent Resistance to Hitler." The Nonviolent Alternative, 1971.

#thomas merton#quote#quotations#denmark#nonviolence#resistance#shoah#holocaust#genocide#ethics#morality#christian theology#truth#collective action#anti-semitism

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scottish Sailors and Commanders

Although some may wonder but there was actually a Scottish Navy which was founded in the 11th century and peaked at the end of the 15th at the beginning of the 16th century. The troop not only grew to 38 ships, but the ships themselves were also successfully deployed in Scottish waters by English, Danish and Portuguese buccaneers.

James IV also added new shipyards and under his rule the first Lord High Admiral position was established. Most importantly, the Scots built the largest warship in the world at the time. The 240 foot long, 1,000 tonne Great Michael had a crew of 1,000 men and carried the famous Mons Meg cannon, a 22 inch giant of a weapon that is distinguished as the largest cannon in history. Founded in 1512, the Scots found Michael far too expensive to maintain. Within two years it was sold to France. Its new owners renamed it The Big Ship of Scotland and released it to the English. Later she fought in the Battle of Solent in 1545 and sunk an English ship.

Scotland relied largely on buccaneers in subsequent wars with England, but during the 19th century Scottish ships fought alongside English ships in various wars against France and Spain. In the 18th century the Scottish naval forces were united to those of Great Britain.

Perhaps this merger is also an explanation for the fact that there are very few representations and images of Scottish sailors or Commanders.

A scotish sailor wearing a kilt- Sailor’s farewell by John Hodges Benwell 1746-1800

Now it may be maybe only my impression but most of the time when i works my way through the history of the Royal Navy. Scottish personalities are mentioned only marginally unless they are really such an outstanding personality that you simply can't ignore them. like e.g. my all time favorite Lord badass Cochrane

But there were some and from the Commanders there were some really successful ones.

There we have a few:

Alexander Selkirk (1676-1721)

Born in Lower Largo, Fife, Alexander Selkirk spent a number of years as a buccaneer on the South Seas, but it was his actions on dry land that lent him notoriety. In 1703, on a privateering expedition, Selkirk argued with the commander about the vessel’s seaworthiness and chose to be put ashore on an uninhabited island rather than sail any further. Selkirk was rescued four years later, by which time he had developed his hunting and wood crafting skills. Many believe that Daniel Defoe based his fictional character, Robinson Crusoe, on Selkirk.

Samuel Greig (1736-1788)

Greig was born in Inverkeithing, Fife, and entered the Royal Navy early. He soon became renowned for his skill, zeal and attention to detail, and quickly rose to Lieutenant. He joined the Russian navy after the Russian Court asked the British to send skilled naval officers to help them and he soon rose to Captain. Greig distinguished himself first at the Battle of Chesma in 1770, where he bore down with fire ships and destroyed the entire Turkish fleet, and the Battle of Hogland against the Swedes in 1788. It was in the latter that Greig, or Count Orlov as he was then, contracted fever and died. He received a full Russian state funeral in Talinn.

Lord Thomas Cochrane the Seawolf (1775-1860)

Born near Hamilton, South Lanarkshire, on 14 December 1775, Thomas Cochrane became the model for Hornblower and Jack Aubrey. During the Napoleonic Wars, Lord Thomas Cochrane’s ship, Speedy, captured 53 French ships and £75,000 in prize money in 13 months, but in 1814 he was dismissed when imprisoned for stock exchange fraud. A daring buccaneer, Cochrane successfully led the rebel navies in Chile, Brazil and Greece before being reinstated as a Rear-Admiral in 1832.

Admiral Andrew Wood (1450-1538)

‘Scotland’s Nelson’ was born in Upper Largo in Fife and owned two ships trading from Leith. Wood was also a privateer who preyed on English ships, and was the personal sea captain to James III. In 1488, Wood captured five English privateers and became an admiral in the Royal Scots Navy. In 1511, he took command of the Navy’s flagship, Great Michael, then the largest ship in Europe, and commanded the Scottish fleet against the English in 1513.

Charles John Napier (1786-1860)

Napier’s distinguished 60-year naval career included service in the Napoleonic Wars, Syrian War, Crimean War and the Anglo-American War of 1812-15. An innovator concerned with the development of iron ships, he was also a Liberal MP. During the Syrian War, Napier negotiated peace with Egyptian ruler Muhammad Ali. ‘I do not know if I have done right in settling the eastern question,’ he wrote to Lord Minto. Napier was knighted in 1840 and became aide-de-camp to Queen Victoria in 1841. He had three nicknames: Black Charlie, because he was 14 stone and walked with limp; Mad Charlie, because of his eccentric behaviour; and Dirty Charlie, for his unsuitable clothing.

Aleksey Greig (1775-1845)

Son of Samuel Greig, Aleksey Greig studied at the Royal High School of Edinburgh and on HMS Culloden under Admiral Trowbridge. After serving in the Royal Navy from 1785-1796 he returned to Russia to take part in expeditions against revolutionary France. In 1801 he was banished to Siberia for arguing with Emperor Paul about the treatment of British prisoners, but distinguished himself in 1807 during the Battle of Athos and Battle of the Dardanelles. In 1816 he was put in command of the Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol.

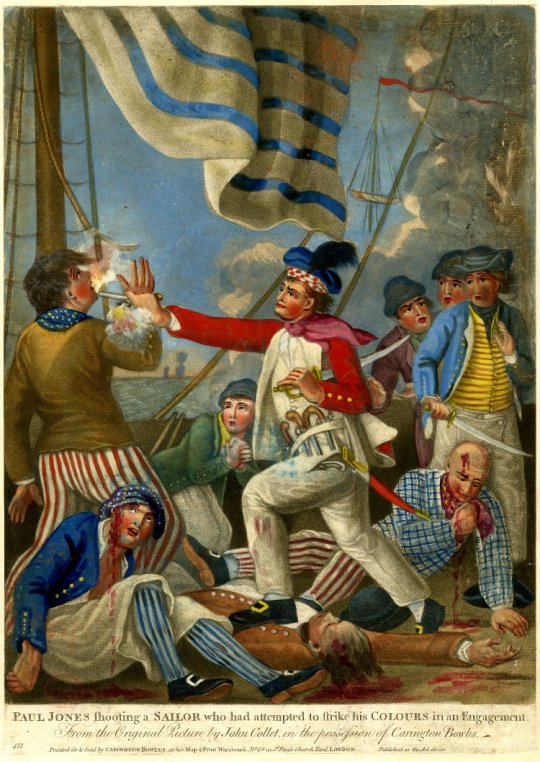

John Paul Jones (1747-1792)

The son of a gardener, Jones was born in Kirkcudbright, began his naval career aged 13 as an apprentice, and sailed aboard a number of British merchant and slave ships. The vicious flogging of one of his sailors and the killing of a member of his crew over a dispute over wages tarnished Jones’ reputation, but it was this ruthless streak that led to his triumph fighting for the American navy against the British during the Revolutionary War. In that conflict he distinguished himself in American and British waters, becoming a hero of the American revolution. Jones later served in the Russian Imperial Navy and retired to Paris in 1790, where he died two years later.

@bantarleton i told you i do it ;) and to all others, the list may of course be extended

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iconic Capitals & Towns of the Baltic

Helsinki - Copenhagen

DATES:

7/24/2023 to 8/2/2023 10 days 9 nights onboard

At the heart of the Baltic Sea, discover the emblematic towns and capitals of the region, a blend of History and sumptuous landscapes. During this brand-new 10-day cruise aboard Le Champlain, fall under the spell of the majestic panoramas of northern Europe.

Your cruise will sart at Helsinki. Located on a peninsula surrounded by almost 300 islands, the verdant capital of Finland will charm you with its Art Nouveau architecture.

You will visit Tallinn, emblematic city of the Hanseatic League, the large trading network that dominated the Baltic Sea for several centuries. Listed as UNESCO Heritage Site, this once opulent city still have remarkably well-preserved public buildings, merchant houses and warehouses.

Le Champlain will then chart a course for Stockholm. Built on water, the Swedish capital embraces nature, which is omnipresent there. Its blend of medieval architecture, colourful houses and trendy neighbourhoods makes it a particularly enjoyable city to visit.

Le Champlain will then sail to the Swedish island of Gotland and call at Visby, a site that was important for the Hanseatic League in the Baltic Sea around the 13th century. UNESCO Heritage Site, this once opulent city still has remarkably well-preserved ramparts, public buildings, merchant houses and warehouses.