#Colette Audry

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Criticism of Non-Intervention in Spain (1936): The Role of the Press.

In this post, I will base myself on the various criticisms of the policy of non-intervention in Spain, appearing in the press.

Without giving you a classic lesson, I will quote a lot from the various interventions of journalists and editorialists. This post is a bit long, but as long as I make myself clear, everything is fine...

From mid-July 1936, the editorialists of the newspaper L’Humanité (central organ of the French Communist Party since 1920) denounced the “interventionism” of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, that is to say the delivery of weapons to the rebels. The editorialists of L’Humanité rely on the information collected by Paul Vaillant-Couturier in August. This communist reporter witnessed the presence at Franco’s home of twenty Junker bombers, five planes displaying the swastika, and many German and Italian officers. The editorialists of L’Humanité rely on information gathered by Paul Vaillant-Couturier in August. This reporter (a member of the French Communist Party) witnesses the presence at Franco’s home of twenty Junker bombers, five planes displaying the swastika, and many German and Italian officers.

In the magazine Europe (founded by Romain Rolland), Jean-Richard Bloch shares his analysis of what is happening in Spain: “under our noses, with an impudence, a cynicism and almost a publicity that gave the measure of their contempt, Germans and Italians continued to supply the rebels”. Similarly, La Révolution espagnole also bears witness to the delivery of weapons for Franco’s militia.

La Révolution espagnole, as the weekly French edition of the POUM, was created on September 3, 1936. Colette Audry, an activist in the CGTU (the communist branch of the CGT from 1920 to 1936), editor at L’Ecole émancipée, member of the Comité de Vigilance des Intellectuels Antiascistes, was present in Spain throughout the summer of 1936.

She met Julian Gorkin and other POUM activists. Colette Audry was the main translator of La Révolution espagnole and the newspaper’s French correspondent. Responsible for distributing it, she played an important role in recruiting volunteers to fight. La Révolution espagnole, as a Franco-Spanish magazine, published only in the first months of the Spanish Civil War, was totally militant in its distribution. Its first page states: “Please reproduce” (in order to break a certain confidentiality, certainly…). The editorials of The Spanish Revolution are mostly anonymous, although the first issue is signed by Julian Gorkin. Gorkin denounces the moral and material support of the fascist military leaders by Hitler and Mussolini, going beyond international regulations.

On August 10, in The Proletarian Revolution (magazine of the "CGT - Syndicalist and Revolutionary"), Ida Mett comments on the situation: She mentions the lack of weapons, planes and gasoline for the Spanish antifascists (CNT, POUM), and specifies that "Every day of delay can cause disasters". The revolutionary syndicalists (CGT-SR) are the only ones to mention the idea of delivering weapons to the comrades in Spain.

At the end of August, in L’Humanité, Marcel Cachin proclaimed that if the Spanish Republicans, Socialists and Communists had received the same armed support “that Franco and Llano enjoyed” (the latter being a commander of the Carabinieri who took possession of Seville on July 18), “our friends would already be victorious and the murderous fascism of Franco and Llano would be on the ground! That is the truth! And that is why, while pursuing a prudent and resolutely peaceful policy, the French Popular Front has the duty to take the greatest account of the energetic wishes of the workers who have entrusted them with power.” (L’Humanité, August 23).

The term “blockade” is the first term that becomes recurrent in communist speeches strongly opposed to non-intervention. Paul Vaillant-Couturier denounces “the unbearable blockade” and calls for a demonstration to protest against the “blockade.” After Blum's speech at Luna-Park, Vaillant-Couturier published an editorial entitled "Down with the blockade!". The next day, Maurice Thorez published his editorial entitled "We must stop the blockade". On September 20, it was written in L'Humanité "The Spanish Republic must not be a victim of the blockade!". "Neutrality" is the second term that causes controversy. For example, the editorial of September 17 of La Révolution espagnole, is very critical of this neutrality advocated by Blum. "After having denied the existence of international law, Blum arrives at the logical consequence: while France helps the regular government of Spain, the fascist countries support the rebels.

The "neutrality" advocated by Léon Blum is the second controversial term. For example, the September 17 editorial of La Révolution espagnole is very critical of this neutrality advocated by Blum. "After denying the existence of international law, Blum arrives at the logical consequence: while France helps the regular government of Spain, the fascist countries support the rebels. This is the competition of armaments, and in Blum's thinking this competition would inevitably lead to a European war. One can be all the more surprised by this simplistic logic since, in another part of his speech, Blum affirms that war is possible when it is admitted as possible: fatal, when it is proclaimed fatal. Thus Blum himself inflicts a denial on his attitude in the Spanish revolution. Blum refuses aid to Madrid because he believes war to be fatal. However, nothing could be further from the truth. Despite tremendous heroism, it is the lack of high-powered weapons that forces the workers' militias to advance slowly. It is the lack of planes and cannons that prolongs the war and thus allows the fascists to receive German and Italian reinforcements, despite their poor geographical situation. Thousands of dead workers and peasants massacred in the provinces occupied by the rebels are the terrible price of false neutrality" (The Spanish Revolution, September 17, 1936).

On the side of the Human Rights League, Emile Kahn published three articles in La Lumière, a month after the Luna-Park speech: "This solemn declaration is sincere. This entire Luna-Park speech is of a pathetic and poignant sincerity. But Léon Blum is mistaken: the commitments made have been violated. These acts of interference, contrary to the commitments made, Blum ignored them when he spoke on September 6. But, at this date, was Yvon Delbos unaware of them? Did his agents in Spain fail to report them? The following week, Emile Kahn hammered home in anaphora that it was “morally impossible” to continue to practice this policy of “neutrality”, due to the “protests of interference that were multiplying”.

Even in Le Populaire (official journal of the SFIO), some articles questioned Blum’s policy of neutrality. Jean Zyromski, founder of the Bataille socialiste (left wing of the SFIO), appealed to the facts: “But can we maintain today, in the face of the obvious, tangible, concrete facts of continued supply of the rebels, in the face of the position taken by Portugal, that the position of the French government cannot be modified?” (Le Populaire, September 15, 1936). Then, Jean Zyromski left for the mission of the European Conference for Aid to the Spanish People with Jacques Duclos, Eugène Hénaff, and Georg Branting (Swedish MP). On his return, Zyromski said that he had no intention of attacking the Popular Front government, but he maintained that he had the right (and the duty, he said) to indicate the necessary corrections in the orientation of a policy. Even within the Socialist Battle, there were divergences. Zyromski had to distance himself from his comrades who had fully approved of Léon Blum’s position, and which according to him “compromises the existence of the Spanish Republic.”

It must be said that the term "neutrality" is well and truly emptied of its meaning... On August 15, 1936, Paul Nizan questions the term "neutrality" in the Correspondance internationale (journal of the Communist International), "So that everything is currently happening as if this "neutrality", which is moreover completely incontestable from the point of view of international law, since it is not at all a question of the conflict of two sovereign powers, but of the struggle of a legitimate government against factious people, was only a neutrality of facade". The editorial of October 14 of La Révolution espagnole returns to this "lexical degradation", associating it with the "equally false" exercise of diplomacy: "The diplomatic farce of neutrality is in the process of being denounced". In La Voix libertaire, Jules Goirand, alias Trencoserp, rails: "The diplomatic farce of neutrality is being denounced." In October, the journalist Gabriel Péri, who was in Spain in August 1936, also denounces the absurdity of "neutrality": "The impotent Non-intervention Committee, which holds a weekly session in London, refuses to examine Spanish grievances! When will this odious comedy end?" (Gabriel Péri, L'Humanité, October 7, 1936).

After the words "blockade", "neutrality", "comedy", another related term, that of "deception", appeared in the interventionist press. As early as mid-August, Georges Boris, in La Lumière, called for caution: "But this solution, which in so many respects hurts us painfully, is only one if the fascist countries quickly take and rigorously keep the commitment of neutrality. Otherwise it would be a terrible, deadly deception" (Georges Boris, La Lumière, August 15, 1936). In L'Humanité of September 3, Paul Nizan wonders: "Will the great deception stop? Each day that passes means more blood."

Julio Alvarez del Vayo, Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs, sent the Non-Intervention Committee a note of protest reporting the supply of weapons to the rebel camp. In October 1936, in the CVIA bulletin “Vigilance”, Pierre Bicquart once again described the non-intervention as “deception”.

Gabriel Péri reports, in La Correspondance internationale, on the USSR's denunciation of "the hypocrisy of the so-called non-intervention"; according to Gabriel, "the fascist rebellion bears the Hitlerian hallmark" (La Correspondance internationale, October 17).

On October 23, the USSR announced its break with the non-intervention pact. From then on, the USSR would intensify its aid to Spain. For communist activists, the USSR had shown courage. Gabriel Péri in L’Humanité and Jean-Richard Bloch in Europe were very enthusiastic. According to Gabriel Péri, “For the honor of Europe, the USSR broke the contract which, violated by some of the contracting parties, was nothing more than a scam.”

Paul Nizan, in La Correspondance internationale, emphasized that “it was in no way a conflict between two sovereign powers, but the struggle of a legitimate government against factious people,” establishing a dichotomy between legitimate government and rebellion.

André Marty considered the policy of non-intervention to be contrary to international law. He insisted on the importance of providing equipment necessary for defense. According to this PCF militant fighting for the International Brigades, the "appeasement" policy of the "European democracies" was ineffective. In August 1936, the Comintern appointed André Marty as a delegate to the "Frente Popular", "to consider the help that could be provided by the international communist movement" (cf. "André Marty", according to Jean Maitron and Claude Pennetier). He concluded with this sentence: "The Spanish people do not ask for help, they demand it". André Marty was appointed "inspector general of the International Brigades", based in Albacete.

On November 5, Gabriel Péri, in L’Humanité, refused to use the term “civil war.” In this, he contradicted Paul Nizan’s comments. In August 1936, in the journal Clarté (belonging to the World Committee Against War and Fascism) directed by Paul Langevin and Romain Rolland, Paul Nizan analyzed the situation in Spain as a “civil war pitting the working people and peasants against rebel troops and fascist bands,” with all the artillery, aviation, automatic weapons, and means of guerrilla warfare. François Delaisi (journalist, CGT activist, member of the LDH and the CVIA), in his work L’Homme réel, asserts that the Spanish conflict cannot be reduced to an internal conflict between two factions of the same people, but a conflict whose character goes beyond the narrow framework in which it initially arose.

In Le Libertaire, July 31, Sébastien Faure virulently condemns the inept expression of "fratricidal war", mentioned by both reactionaries and radicals! "Be quiet, hypocrites! Yesterday's was and tomorrow's will be a fratricidal war, since it will determine the most monstrous atrocities between humans condemned to kill each other, when (...) they should live as brothers. But the war which, on the other side of the Mediterranean, arms workers against the lazy, slaves against masters, those who aspire to break their chains against those who try to make them heavier, that war is liberating and holy!".

On November 5, Gabriel Péri, in L’Humanité, refused to use the term “civil war.” In this, he contradicted the remarks made by Paul Nizan three months earlier. In August 1936, in the journal Clarté (belonging to the World Committee Against War and Fascism) edited by Paul Langevin and Romain Rolland, Paul Nizan analyzed the situation in Spain as a “civil war opposing the working people and peasants to rebel troops and fascist bands,” with all the artillery, aviation, automatic weapons, and means of guerrilla warfare. François Delaisi (journalist, CGT activist, member of the LDH and the CVIA), in his work L’Homme réel, asserts that the Spanish conflict cannot be reduced to an internal conflict between two factions of the same people, but a conflict whose character goes beyond the narrow framework in which it was initially posed.

In Le Libertaire of July 31, 1936, Sébastien Faure virulently condemns the inept expression of "fratricidal war", mentioned by both reactionaries and radicals! "Shut up, hypocrites! Yesterday's was and tomorrow's will be a fratricidal war, since it will determine the most monstrous atrocities between humans condemned to kill each other, when (...) they should live as brothers. But the war that, on the other side of the Mediterranean, arms workers against the lazy, slaves against masters, those who aspire to break their chains against those who try to make them heavier, that war is liberating and holy!"

Calls for armed aid are becoming more and more pressing. In opposition to Luna-Park's speech, the now famous slogan "Cannons, planes for Spain!" is chanted during the demonstrations. According to Adrienne Montégudet, editor at La Révolution prolétarienne, "Only Mexico has done its duty !" The slogan "Cannons, planes for Spain !" is taken up by La Révolution espagnole, Le Libertaire, and La Voix Libertaire.

0 notes

Text

Frank Villard and Danièle Delorme in Gigi (Jacqueline Audry, 1949)

Cast: Danièle Delorme, Yvonne de Bray, Gaby Morlay, Jean Tissier, Frank Villard, Paul Demange, Madeleine Rousset, Pierre Juvenet, Michel Flamme, Colette Georges, Yolande Laffon, Hélène Pépée. Screenplay: Pierre Laroche, based on a novel by Colette. Cinematography: Gérard Perrin. Set decoration: Raymond Druart. Film editing: Nathalie Petit-Roux. Music: Marcel Landowski.

The print I saw of Jacqueline Audry’s Gigi was not very good, the images having shifted into high contrast with little variation in the grays, so that the subtitles were often an unreadable white on white. But anyone familiar with either the Colette novella or the 1958 Lerner and Loewe musical version directed by Vincente Minnelli would have little trouble following the story. It’s a movie that retains much of the charm and a little of the bite of the original, and Danièle Delorme is a fetching Gigi, the girl raised to be a grande horizontale who wins the heart and hand of the wealthy Gaston Lachaille (Frank Villard). Delorme and Villard don’t erase memories of Leslie Caron and Louis Jourdan in the musical, but they have their own contributions to make, especially Villard, who is particularly strong in the scenes in which Gaston comes to realize the true nature of his feelings for Gigi. You sense his rising queasiness when she accepts his proposal to become his mistress, especially in the scene in the private room at the restaurant where they are about to consummate their relationship. When she naively asks why the couches in the room have slipcovers and when she chooses his cigar by rolling it between her fingers as she has been taught, the full obscenity of the situation becomes apparent to him. It has been apparent to us from the moment at the beginning of the film when we meet his uncle, Honoré, whom Jean Tissier plays as far more a dirty old man than the elegant Maurice Chevalier did in the musical. Which is not to say that the movie’s moral stance is heavy-handed: Director Audry has a very light touch, the product of a close collaboration with Colette. There are some wonderful period touches throughout the film, including Gaston’s automobile, Aunt Alicia’s (Gaby Morlay) telephone, and the bathing machine that is pulled by a mule into the waves at Deauville. The movie also reminded me that Gigi is a nickname for Gilberte, which is also the name of Swann’s daughter and the narrator’s first infatuation in Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu. There’s also a scene in which Gigi plays hide-and-seek with other schoolgirls in the park, that echoes for me Albertine and her little band of girls in À l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs. Proust was only two years older than Colette, and the Recherche and Gigi very much share the same milieu.

0 notes

Photo

- Tell me what it's like to be in love. - No, it's too horrible to talk about, too delightful to think about...

Olivia, Jacqueline Audry (1961)

#Jacqueline Audry#Colette Audry#Edwige Feuillère#Simone Simon#Marie Claire Olivia#Yvonne de Bray#Suzanne Dehelly#Marina de Berg#Lesly Meynard#Rina Rhéty#Tania Soucault#Elly Claus#Nadine Olivier#Christian Matras#Pierre Sancan#Marguerite Beaugé#1961#woman director

28 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Minne, l'Ingénue Libertine" de Jacqueline Audry (1950) - adapté du roman "L'Ingénue libertine" de Colette (1909) - avec Danièle Delorme, Franck Villard, Claude Nicot, Roland Armontel, Yolande Laffon et Jean Tissier, juillet 2021.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

some thoughts on Olivia (1951), so cw: sexual abuse, csa, grooming

i loved this movie so much, and i want both to read the book by dorothy bussy and explore jacqueline audry’s filmography (which include three adaptations of colette novels). i was prepared for the plot involving grooming and abuse of children & teenagers, but was still taken aback by how it was portrayed. it was tastefully done imo, but felt more brutal than i was expecting. something that affected me a lot were the scenes of olivia lying in bed, immobile, waiting expectantly for mlle. julie; the tension this built, how affecting it was both when she did and did not show up.

was also really fascinated by how vampiric mlle. julie was, and i wonder if i’m just too obsessed with vampires or if that was deliberate. this certainly seemed to be on purpose:

but also the way she would look longingly at the girls and then attempt to control herself, like a vampire smelling blood. or the scenes of olivia in bed, as i mentioned, waiting for that shadowy figure to enter her room. and, of course, maybe most of all, the hold mlle. julie had on the girls, how olivia’s passionate love could be compared to the effects of a vampire thrall.

mlle. cara was one of the saddest parts of the movie for me. she’s emotionally stunted, dependent on julie, desperate for love and attention, and acts like a spoiled little girl. there’s a scene where she says to herself “je suis une petite, une toute petite” and it broke my heart.

there’s a lot more to say about olivia, but i’m not feeling eloquent right now. i’m just struck by how much i loved it, and how so many elements seemed to me to be right out of a horror movie. i think i have a tendency to approximate the movies i love to horror, even when they aren’t considered such, but i do think it fits in this case.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

MADCHEN IN UNIFORM (’31): The First Lesbian Feature Film By Raquel Stecher

Director Leontine Sagan’s MADCHEN IN UNIFORM (’31) wasn’t the first movie that featured lesbian characters but it was certainly a notable one. This German film came during a time between WWI and WWII when there was a thriving gay subculture in parts of Europe. Movies like DIFFERENT FROM THE OTHERS (’19) and MICHAEL (’24) were born out of that era and candidly depicted gay relationships. Marlene Dietrich gave the world the first cinematic lesbian kiss in MOROCCO (’30). PANDORA’S BOX (’29), starring Louise Brooks, featured a lesbian subplot. This was a flourishing time for queer representation and it ended abruptly with the emergence of the Nazi regime.

MADCHEN IN UNIFORM was special in many regards. It’s the first feature film with a solely lesbian theme. It was based on a play written by a woman. It was directed by a woman, with an artistic director credit going to Carl Froelich. And, the cast was completely made up of women. Not a single man can be spotted throughout the whole movie.

Set in a Prussian all-girls boarding school, MADCHEN IN UNIFORM, which translates into “Girls in Uniform,” tells the story of new student Manuela (Hertha Thiele) and her attraction towards her instructor, Fraulein von Bernburg (Dorothea Wieck). The school is run by a strict headmistress, played by Emilia Unda, who extols Prussian virtues of discipline, obedience, restraint and self-denial. In the context of the story, these virtues are seen as old-fashioned and severe, something that the contemporary audience of Germany’s Weimar Republic would have agreed with. The headmistress creates an environment that stifles Manuela and her fellow students who find themselves in a fairly delicate stage of their development. Even though it’s a toned-down version of the original play, Sagan’s film is still a notably frank expression of lesbian romance. There is a kiss between Wieck and Thiele, an exchange of garments, a brief experimentation with gender identity and a passionate declaration of love.

Playwright Christa Winsloe based the story on her own experience at a Prussian boarding school. Writing the play was her way of processing the trauma of her youth. Upon the success of her play, Winsloe moved to Berlin and lived openly as a lesbian. She was once married to a Baron then later became romantically involved with two other women writers, newspaper reporter Dorothy Thompson and Swiss author Simone Gentet.

Winsloe’s play caught the eye of theater producer and actress Leontine Sagan. In her memoir, Sagan recalls MADCHEN IN UNIFORM “was an original play and true to life, but it was technically rough and amateurish in its dramaturgical structure. Nonetheless, I liked this unusual play about girls in a Prussian boarding school and made the author’s acquaintance.” MADCHEN IN UNIFORM would be Sagan’s directorial debut and she would later produce the play for the Duchess Theatre in London.

It was inevitable that changes had to be made to Winsloe’s original story. Overt lesbian themes were dialed back. Artistic director Froelich suggested that the ending be changed from tragedy to something that would be more open-ended. While Winsloe approved of the final film, she still felt a natural possessiveness towards her story. She novelized the film, her way of taking ownership of the story once again, and published MADCHEN IN UNIFORM as a book in 1933.

Upon release, critics and audiences alike raved about the movie. It received glowing reviews. While it was never widely released in the United States, it did ultimately screen in over 1,000 theaters. Andre Sennwald of The New York Times called it a “masterpiece”. Mordaunt Hall of the same publication said in two 1932 reviews “Few motion pictures have been endowed with the magnetic quality of MADCHEN IN UNIFORM… It is a film in which all the characters fasten themselves in one’s mind, not as actors, but as real persons. The performances of all are deserving of the highest praise.” Of course the film met with some opposition. It was “Banned in Boston”, a badge of honor for provocative work. Film producer John Krimsky battled with the Hays Office to get the film approved for distribution.

Producer David O. Selznick was so impressed with Sagan’s debut film that he invited her to Hollywood. She made two films there, both were flops, and returned to the theater where she thrived. Actress Dorothea Wieck was also courted by Hollywood. Paramount executives, intrigued by her striking resemblance to MGM star Norma Shearer, put her under contract. Wieck’s Hollywood films were box-office failures. She was booted out of tinseltown and unfairly labeled a Nazi spy. The irony was that Wieck was an outspoken critic of the Nazi regime and refused to act in Nazi propaganda films.

In fact most of the women involved with MADCHEN IN UNIFORM were courted by the Nazis. Although the film was banned in Nazi Germany and many copies were destroyed, Joseph Goebbels himself was a fan and called it a “magnificently directed, exceptionally natural and exciting film art”. Leontine Sagan, actresses Hertha Thiele and Erika Mann all refused offers by the Nazi government to use their talents for propaganda.

After the war, the film languished under censorship but never lost its appeal. It was remade several times including a 1958 film adaptation starring Lilli Palmer and Romy Schneider. It was in a long line of lesbian-themed stories set in all-girl schools, including Colette’s Claudine novels (she wrote the French subtitles for the film), Jacqueline Audry’s OLIVIA (’51) and William Wyler’s THE CHILDREN’S HOUR (’61). MADCHEN IN UNIFORM enjoyed a resurgence of interest in the 1970s finding fans among a growing community of feminists and lesbians with an interest in women directed films. Today it still stands as a seminal lesbian drama that deserves to be studied and appreciated.

#LGBTQ#lesbian representation#lesbian romance#Prussia#war#boarding school#TCM#Turner Classic Movies#Raquel Stecher

544 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Theirs was a new kind of relationship, and I had never seen anything like it. I can’t describe what it was like to be present when those two were together. It was so intense that sometimes it made others who saw it sad not to have it.

Colette Audry on the relationship between Sartre and Beauvoir, in the interview with Deirdre Bair, March 5, 1986

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(OC) Marlin The Yoshi

Bio: Marlin Yoshi

Name: Marlin

Gender: Male

Age: 25

Sexuality: Straight

Birthday: January 1st

Species: Yoshi

Relationship/Wife: Arilyn

Family Members: Cole (Mother) Micole (Mother) Nivian (Grandma) Midnight (Grandpa) James (Grandpa) Tori (Grandma) Vicktoria (Aunt) Jamarr (Uncle) Victorio (Uncle) Jamell (Uncle) Jamesie (Uncle) Victoire (Aunt) Toree (Aunt) Jame (Uncle) Noora (Sister) Maxwell (Brother) Noel (Sister) Manfried (Brother) Marlyssa (Brother) Moses (Brother) Nerissa (Sister) Nuna (Sister) Nea (Sister) Micoletta (Sister) Mickey (Brother) Luiggi (Brother) Luigina (Sister) Clo (Sister) Coe (Brother) Cloris (Younger Sister) Madea (Younger Sister) Olivia (Younger Sister) Hailee (Youngest Sister) Cube (Youngest Brother) Starr (Youngest Sister) Aryan (Son) Aryeh (Son) Marabella (Daughter) Marabelle (Daughter) Arysta (Daughter) Marcelo (Son) Marcel (Son) Malin (Favorite Son) Arilla (Daughter) Arielle (Daughter) Arietta (Adopted Daughter) Maryn (Adopted Son) Zavier (Piplup Pokemon) Evan (Brother in law) Evans (Nephew) Maxima (Niece) Margolette (Niece) Margo (Nephew) Evanam (Nephew) Maxon (Nephew) Maxton (Nephew) Evanne (Niece) Evander (Nephew) Evanna (Niece) Danny (Brother in law) Delora (Niece) Dallan (Nephew) Dallin (Nephew) Nova (Niece) Nikolas (Nephew) Danae (Niece) Danni (Niece) Danna (Niece) Nooriel (Nephew) Darry (Nephew) Dooley (Nephew) Noah (Younger Nephew) Noa (Younger Niece) Noire (Younger Niece) Donny (Younger Nephew) Noor (Youngest Niece) Norah (Youngest Adopted Niece) Daniyal (Youngest Adopted Nephew) Ryder (Brother in law) Nollan (Nephew) Rylan (Nephew) Ryland (Nephew) Renae (Niece) Noeletta (Niece) Ryden (Nephew) Nohl (Nephew) Noella (Niece) Ryenne (Niece) Noely (Niece) Clover (Sister in law) Clovis (Nephew) Marcie (Niece) Marcy (Niece) Claude (Nephew) Claud (Nephew) Marcellus (Nephew) Cloud (Nephew) Mearl (Nephew) Cova (Niece) Clarke (Niece) Clark (Nephew) Malik (Nephew) Mali (Nephew) Cove ((Niece) Manfred (Nephew) Karl (Brother in law) Marly (Niece) Marlis (Niece) Mirabela (Niece) Carlyle (Nephew) Carlus (Nephew) Carlin (Niece) Cal (Nephew) Karl (Brother in law) Marly (Niece) Marlis (Niece) Mirabela (Niece) Carlyle (Nephew) Carlus (Nephew) Carlin (Niece) Cal (Nephew) Miggy (Niece) Mariam (Niece) Kiri (Nephew) Kerri (Niece) Embo (Nephew) Audrina (Sister in law) Marlo (Nephew) Audey (Nephew) Adya (Nephew) Audley (Nephew) Adney (Nephew) Marrin (Niece) Marry (Niece) Morris (Nephew) Audric (Nephew) Auden (Nephew) Austen (Nephew) Marten (Nephew) Moselle (Niece) Audry (Youngest Niece) Moshe (Youngest Nephew) Marco (Brother in law) Nessa (Niece) Maci (Niece) Marco (Nephew) Neela (Niece) Marc (Nephew) Nestor (Nephew) Marcella (Niece) Marcelle (Niece) Nero (Nephew) Nerian (Nephew) Sunset (Sister in law) Elaine (sister in law) Sandra (Sister In law) Micola (Niece) Sander (Nephew) Sandro (Nephew) Sammy (Nephew) Micolette (Niece) Suzette (Niece) Sandriana (Niece) Michelette (Niece) Michela (Niece) Sanderson (Nephew) Michel (Nephew) Michele (Nephew) Melissa (Sister in law) Mellisa (Niece) Mick (Nephew) Melissza (Niece) Melisha (Niece) Mel (Niece) Micki (Niece) Mickie (Niece) Mike (Nephew) Mikko (Nephew) Melvyn (Nephew) Virginna (Sister in law) Candace (Sister in law) Lydia (Sister in law) Peasly (Brother in law) Tiffiny (Sister in law) Toren (Brother in law) Boone (Uncle) Amarah (Aunt) Nikson (Uncle) Nirvana (Aunt) King Coal (Uncle) Nicole (Aunt) Katie (Cousin) Kylar (Cousin) Coal Jr (Cousin) Aleiza (Cousin) Zeke (Cousin) Tabarious (Cousin) Tavio (Cousin) Adalley (Cousin) Tamburlaine (Cousin) Fuzzy (Cousin) Sabrina (Younger Cousin) Ayden (Younger Cousin) Nikole (Younger Cousin) Koal (Younger Cousin) Cortney (Youngest Cousin) Nicoletta (Youngest Cousin) Nicola (Youngest Cousin) Nicco (Youngest Cousin) Colette (Aunt) Colleen (Cousin) Cox (Cousin) Coxe (Cousin) Clarette (Cousin) Coleta (Cousin) Colley (Cousin) Robley (Cousin) Colie (Cousin) Coline (Cousin) Conrad (Cousin) Conran (Cousin) Coelee (Cousin)

Personality: Clumsy, Active, Shy, Caring, Helpful, Creative, Gamer, And Sensitive

Friends: Clumsy Smurf Nat Smurfling Smurfette Smurf Painter Smurf Cookie (My bestie's oc and Best Friend) Karlie (2nd Best Friend) Javon (3rd Best friend) Boston (4th Best friend) Forest (5th Best friend) Ebbe Muffin (My Bestie's oc and 6th best friend) Laura (My bestie's oc and 7th best friend) Clova (My bestie's oc) Myron (My bestie's oc and 8th best friend) Finnley (My bestie's oc) Julyana (Our oc and 9th best friend) Kaitlin (Our oc) Kaeli (Our oc and 10th best friend) Kaleo (Our oc and 11th best friend) Keara (Our oc) Alysha (My Bestie's oc and 12th best friend) Noelia (13th best friend) Ozzy (My bestie's oc and 14th best friend) Ander (Our oc and 15th best friend) Leevi (Our oc and 16th best friend)

Favorite Color: Green

Favorite Season: Fall And Winter

Favorite Holiday: Thanksgiving And Christmas

Fun Fact: Marlin is kinda a clumsy yoshi, he does trip and drop stuff sometimes. But he always cleans up his mess. Since he's very clumsy. By being clumsy, he is very active, especially during the winter. He love playing in the snow. And mostly love to have snowball fights with his siblings. And at the end of the day after playing in the snow. He snuggles by the fire, and spend time with he's mini crewmate and mini imposter. Being active, he can be very shy. Even when he was a baby yoshi, he was very shy. He isn't use to be around a lot of people, but he love being by his best friend Cookie. He is very caring, especially around he's family. He may be shy, but he is very caring. Being caring, he love helping out, he helps both he's mother's a lot. He also take care of he's mothers mini imposter and mini crewmarte. Why they both are out on a date. He is also very attached to he's younger adopted siblings. He cares so much about them, that he will and always keep them safe. Because he is very helpful and very caring. on he's free time, he can be very creative. He love's drawing, he most makes fanart of his favorite series or franchise. Like he's mother Cole. She does the same. He also love drawing for he's mothers on their birthday. On he's free time. He does play video games. He mostly plays multiplayer games. He love's playing Among Us, and a bunch of Mario games. He mostly plays them with both he's mothers. He also love being the imposter both normal and hide and seek. He does go after he's mother Cole first. Before killing other crewmates. And he can be very sensitive, he doesn't like to see anything scary, he is very sensitive to scary things. It kind always make him sick a little bit. Since he is very sensitive to that kind of stuff.

Marlin belong to: me

Yoshi Species: Nintendo

0 notes

Photo

2/3 LA BATAILLE DU RAIL 27 février 1946 en salle / 1h 25min / Drame, Guerre De René Clément Par Colette Audry, René Clément Avec Jean Daurand, Jean Clarieux, Tony Laurent Regardez "La Bataille du rail ( bande annonce )" sur YouTube https://youtu.be/0CS8iZc1WIw SYNOPSIS Camargue, un chef de gare, aide autant qu'il le peut les juifs à fuir les zones occupées par les nazis, pendant la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. Ces résistants leur font traverser cette frontière entre deux France afin qu'ils ne se fassent pas déporter. Ils organisent également des sabotages d'opérations prévues par les allemands et transmettent des informations précieuses au QG londonien. Ce groupe de héros s'appelle la "Résistance Fer". #culturejaiflash https://www.instagram.com/p/CTjTz4JMtFg/?utm_medium=tumblr

0 notes

Photo

Relato 3 Parte. Lo estás Leyendo??? ...Cuando abrí los ojos, estaba de pie, Sartre me sostenía de un brazo; lo reconocía, pero todo estaba oscuro en mi cabeza. Subimos hasta una casa donde me dieron un vaso de aguardiente, alguien me limpió la cara, mientras Sartre trepaba en su bicicleta para ir a buscar a un médico que se negó a venir. Cuando Sartre regresó, yo había recobrado un poco mi lucidez; recordaba que estábamos de viaje, que íbamos a ir a ver a Colette Audry. Sartre sugirió que volviéramos a montar sobre nuestras bicicletas: no habría que cubrir más que unos quince kilómetros en bajada. Pero me parecía que todas las células de mi cuerpo se entrechocaban; ni siquiera imaginaba volver a pedalear. Tomamos un trencito a cremallera. La gente alrededor me miraba fijamente con aire asustado. Cuando llamé a la puerta de Colette Audry, lanzó un gritito sin reconocerme. Me mire en el espejo; había perdido un diente, uno de mis ojos estaba cerrado; mi rostro había doblado de volumen y la piel estaba arañada; me resultó imposible hacer pasar una uva sobre mis labios entumecidos. Me acosté sin comer, esperando apenas recobrar una cara normal. . . . . https://www.instagram.com/p/CFnQxVFD2Is/?igshid=1b4lv16r3yx0z

0 notes

Photo

Jacqueline Audry In the blind spot between avant-garde pioneer Germaine Dulac and the “Mother of the New Wave” Agnes Varda - there was Jacqueline Audry. Though certainly not the only post-war French female filmmaker, she was the only one working with any regularity, achieving decent success in the French box office with her resplendently decorated tales of feminine transgression and gender subversion adjusted for mid-century tastes. Beginning with her 1945 debut ‘The Misfortunes of Sophie’ Audry directed 16 films by the time she stopped working in the late ‘60s. She was at the height of her powers in the ‘50s a winning (and losing) streak that paralleled Hollywood’s own woman filmmaker of choice, Ida Lupino. Considering recent efforts to cure cultural amnesia of Lupino’s legacy you can imagine how history has treated Audry. In an era when few women got the chance to be behind the camera, Audry’s womanhood worked against her, and also affected how she’s been (or not been) remembered. The long shadow cast by the French New Wave didn’t help, in part because her work embodied precisely the novel adaptation-reliant “cinema of quality” that Francois Truffaut denounced in one of his infamous written kick-offs to the movement. Audry’s fluid camera work suggests the influence of Max Ophüls for whom she worked as an assistant. Like Ophüls, Audry could be described as a “woman’s director” a term for a director who is particularly sensitive to directing actresses, especially in melodramas. Audry’s 13 features, most of which had female protagonists and some of which were censored, include three adaptations from the writer Colette and the 1954 film version of Sartre’s ‘No Exit’. The most intriguing is ‘Le secret du Chevalier d’��on’ (1959) a biopic of the French soldier and diplomat who, after appearing publicly as a man for many years, subsequently identified as a woman (Audry’s film instead portrays the chevalier as a woman masquerading as a man.) Andrew Sarris’s pioneering history ‘The American Cinema’ included a section devoted to those directors he considered ‘Subjects for Further Research’. (at Barbican Centre) https://www.instagram.com/p/B9WVVNwAmCp/?igshid=1a85kygyrzzii

0 notes

Photo

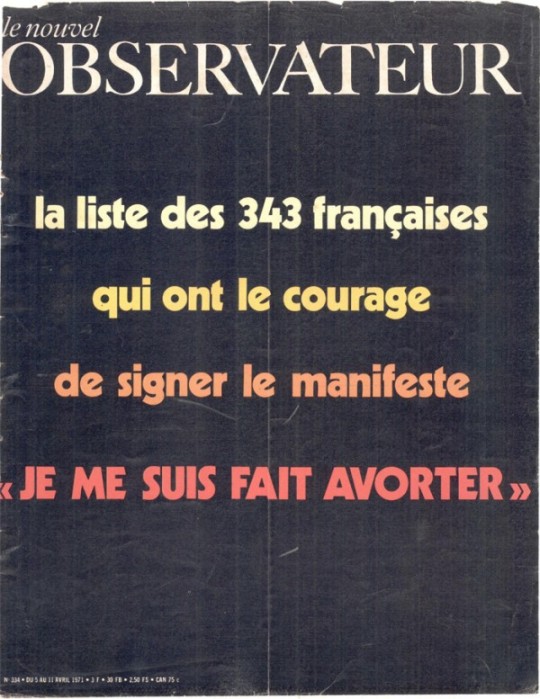

La liste des 343 signataires qui ont eu le courage de publier dans le Nouvel Observateur du 5 avril 1971 ce manifeste : "Je me suis fait avorter", alors qu'elles encouraient des peines de prison.

Merci Mesdames. <3

"J. Abba-Sidick Janita Abdalleh Monique Anfredon Catherine Arditi Maryse Arditi Hélène Argellies Françoise Arnoul Florence Asie Isabelle Atlan Brigitte Auber Stéphane Audran Colette Audry Tina Aumont L. Azan Jacqueline Azim Micheline Baby Geneviève Bachelier Cécile Ballif Néna Baratier D. Bard E. Bardis Anna de Bascher C. Batini Chantal Baulier Hélène de Beauvoir Simone de Beauvoir Colette Bec M.

Bediou Michèle Bedos Anne Bellec Lolleh Bellon Edith Benoist Anita Benoit Aude Bergier Dominique Bernabe Jocelyne Bernard Catherine Bernheim Nicole Bernheim Tania Bescomd Jeannine Beylot Monique Bigot Fabienne Biguet Nicole Bize Nicole de Boisanger Valérie Boisgel Y. Boissaire Silvina Boissonnade Martine Bonzon Françoise Borel Ginette Bossavit Olga Bost Anne-Marie Bouge Pierrette Bourdin Monique Bourroux Bénédicte Boysson-Bardies M. Braconnier-Leclerc M. Braun Andrée Brumeaux Dominique Brumeaux Marie-Françoise.Brumeaux Jacqueline Busset Françoise De Camas Anne Camus Ginette Cano Ketty Cenel Jacqueline Chambord Josiane Chanel Danièle Chinsky Claudine Chonez Martine Chosson Catherine Claude M.-Louise, Clave Françoise Clavel Iris Clert Geneviève Cluny Annie Cohen Florence Collin Anne Cordonnier Anne Cornaly Chantal Cornier J. Corvisier Michèle Cristofari Lydia Cruse Christiane Dancourt Hélène Darakis Françoise Dardy Anne-Marie Daumont Anne Dauzon Martine Dayen Catherine Dechezelle Marie Dedieu Lise Deharme Claire Delpech Christine Delphy Catherine Deneuve Dominique Desanti Geneviève Deschamps Claire Deshayes Nicole Despiney Catherine Deudon Sylvie Dlarte Christine Diaz Arlette Donati Gilberte Doppler Danièle Drevet Evelyne Droux Dominique Dubois Muguette Dubois Dolorès Dubrana C. Dufour Elyane Dugny Simone Dumont Christiane Duparc Pierrette Duperray Annie Dupuis Marguerite Duras Françoise d’Eaubonne Nicole Echard Isabelle Ehni Myrtho Elfort Danièle El-Gharbaoui Françoise Elie Arlette Elkaim Barbara Enu Jacqueline d’Estree Françoise Fabian Anne Fabre-Luce Annie Fargue J. Foliot Brigitte Fontaine Antoinette Fouque-Grugnardi Eléonore Friedmann Françoise Fromentin J. Fruhling Danièle Fulgent Madeleine Gabula Yamina Gacon Luce Garcia-Ville Monique Garnier Micha Garrigue Geneviève Gasseau Geneviève Gaubert Claude Genia Elyane Germain-Horelle Dora Gerschenfeld Michèle Girard F. Gogan Hélène Gonin Claude Gorodesky Marie-Luce Gorse Deborah Gorvier Martine Gottlib Rosine Grange Rosemonde Gros Valérie Groussard Lise Grundman A. Guerrand-Hermes Françoise de Gruson Catherine Guyot Gisèle Halimi Herta Hansmann Noëlle Henry M. Hery Nicole Higelin Dorinne Horst Raymonde Hubschmid Y. Imbert L. Jalin Catherine Joly Colette Joly Yvette Joly Hemine Karagheuz Ugne Karvelis Katia Kaupp Nenda Kerien F. Korn Hélène Kostoff Marie-Claire Labie Myriam Laborde Anne-Marie Lafaurie Bernadette Lafont Michèle Lambert Monique Lange Maryse Lapergue Catherine Larnicol Sophie Larnicol Monique Lascaux M.-T. Latreille Christiane Laurent Françoise Lavallard G. Le Bonniec Danièle Lebrun Annie Leclerc M.-France Le Dantec Colette Le Digol Violette Leduc Martine Leduc-Amel Françoise Le Forestier Michèle Leglise-Vian M. Claude Lejaille Mireille Lelièvre Michèle Lemonnier Françoise Lentin Joëlle Lequeux Emmanuelle de Lesseps Anne Levaillant Dona Levy Irène Lhomme Christine Llinas Sabine Lods Marceline Loridan Edith Loser Françoise Lugagne M. Lyleire Judith Magre C. Maillard Michèle Manceaux Bona de Mandiargues Michèle Marquais Anne Martelle Monique Martens Jacqueline Martin Milka Martin Renée Marzuk Colette Masbou Cella Maulin Liliane Maury Edith Mayeur Jeanne Maynial Odile du Mazaubrun Marie-Thérèse Mazel Gaby Memmi Michèle Meritz Marie-Claude Mestral Maryvonne Meuraud Jolaine Meyer Pascale Meynier Charlotte Millau M. de Miroschodji Geneviève Mnich Ariane Mnouchkine Colette Moreau Jeanne Moreau Nellv Moreno Michèle Moretti Lydia Morin Mariane Moulergues Liane Mozere Nicole Muchnik C. Muffong Véronique Nahoum Eliane Navarro Henriette Nizan Lila de Nobili Bulle Ogier J. Olena Janine Olivier Wanda Olivier Yvette Orengo Iro Oshier Gege Pardo Elisabeth Pargny Jeanne Pasquier M. Pelletier Jacqueline Perez M. Perez Nicole Perrottet Sophie Pianko Odette Picquet Marie Pillet Elisabeth Pimar Marie-France Pisier Olga Poliakoff Danièle Poux Micheline Presle Anne-Marie Quazza Marie-Christine Questerbert Susy Rambaud Gisèle Rebillion Gisèle Reboul Arlette Reinert Arlette Repart Christiane Ribeiro M. Ribeyrol Delya Ribes Marie-Françoise Richard Suzanne Rigail-Blaise Marcelle Rigaud Laurence Rigault Danièle Rigaut Danielle Riva M. Riva Claude Rivière Marthe Robert Christiane Rochefort J. Rogaldi Chantal Rogeon Francine Rolland Christiane Rorato Germaine Rossignol Hélène Rostoff G. Roth-Bernstein C. Rousseau Françoise Routhier Danièle Roy Yvette Rudy Françoise Sagan Rachel Salik Renée Saurel Marie-Ange Schiltz Lucie Schmidt Scania de Schonen Monique Selim Liliane Sendyke Claudine Serre Colette Sert Jeanine Sert Catherine de Seyne Delphine Seyrig Sylvie Sfez Liliane Siegel Annie Sinturel Michèle Sirot Michèle Stemer Cécile Stern Alexandra Stewart Gaby Sylvia Francine Tabet Danièle Tardrew Anana Terramorsi Arlette Tethany Joëlle Thevenet Marie-Christine Theurkauff Constance Thibaud Josy Thibaut Rose Thierry Suzanne Thivier Sophie Thomas Nadine Trintignant Irène Tunc Tyc Dumont Marie-Pia Vallet Agnès Van-Parys Agnès Varda Catherine Varlin Patricia Varod Cleuza Vernier Ursula Vian-Kubler Louise Villareal Marina Vlady A. Wajntal Jeannine Weil Anne Wiazemsky Monique Wittig Josée Yanne Catherine Yovanovitch Annie Zelensky" Manifeste publié dans le “Nouvel Observateur” numéro 334, du 5 avril 1971.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sentiers métropolitainS Repérage - Place de Trion - Champvert - Parc de la passerelle

Participants : Nicolas Husson (guide de cette balade)) Pierre Gonzales Isabelle Clermont (artiste québécoise en résidence à Lyon) Patrick Mathon Gilles Malatray

Ce nouveau parcours des hauteurs prolonge celui effectué préalablement de la Basilique de Fourvière à Vaise, par le parc des hauteurs. C’est cette fois-ci « l’axe vert » de Champvert qui servira de fil rouge, un parcours donc coloré ! Fin de soirée, 18H, place de Trion, c’est donc là notre point de départ pour une nouvelle balade, un nouveau tronçon urbain, entre repérage et questions autour des aménités paysagères et des itinéraires possibles, des jonctions géographiques, pour expérimenter notre futur parcours. La température est un brin fraiche mais le soleil donne au paysage de belles couleurs de fin de journée, et de fin d’année. Nous stationnons quelques instants sur cette belle place du Trion, avec ses arbres, ses bancs, ses commerces alentours, et sa fontaine romaine, vestige des importants travaux d’adduction d’eau que les romains avaient effectués pour alimenter Lyon depuis les hauteurs des Monts du Lyonnais. Malgré l’apparence visuelle bucolique de cet espace public, l’urbanité se fait entendre assez fortement, tant cette place est située sur un nœud passager, un axe fort de la circulation lyonnaise. Juché dans une niche sur une façade bordant la place, un pèlerin nous montre du doigt la direction du chemin de Compostelle, que finalement nous n’emprunterons pas. Notre pèlerinage sera ce soir tout autre, plutôt jalonné d’arbres et de parcs. Nous traverserons un bout de ce quartier pour rejoindre un petit lotissement caché derrière des arbres et venant buter sur les talus de l’ancienne voie de chemin de fer ’Ouest Lyonnais, (la FOL) un autre axe structurant de notre promenade.

De la rue Pierre Audry à l’Avenue Barthélémy Buyer, des vestiges de ponts, des piles d’arches et quelques murs soulignent le tracé de cet ancien « tacot » qui partait de la gare de Saint-Just, maintenant terminus du funiculaire, pour relier Francheville via l’Étoile d’Alaï. Nous pouvons, à certains endroits, grimper sur le talus pour constater comment cette voie a été en partie morcelée, coupée par des privatisations sauvages, et en d’autres endroits aménagée en de curieux lieux de pic-niques ou autres endroits de détente. Arrivés au carrefour de la rue Barthélémy Buyer, face à un « super » marché , qui cherche à se dissimuler sous un de lattes de bois nous stationnons un moment au centre d’une banane qui sépare les quelques routes fort circulantes de cette jonction routière, dans le but de permettre à un membre de notre équipage de nous rejoindre. Ce positionnement sur un terre-plein au centre d’un carrefour est assez anachronique, mais la randonnée urbaine, c’est aussi oser se ménager ce genre de surprises, ou de positions décalées - assumons l’urbanité… L’équipe au complet, nous continuons à longer l’ancienne voie de chemin de fer par un sentier de randonnée « coulée verte », qui dans son intégralité (actuelle), mène de Saint-Just à Tassin la Demi-lune. La nuit est quasiment tombée, et c’est dans un beau clair-obscur, avec des tapis de feuilles mortes aux couleurs de rouille, avec les derniers oiseaux qui nous saluent de leurs chants qui vont bientôt s’éteindre, que nous prenons la première rampe qui nous conduira vers ce chemin aménagé. De nombreux joggers et piétons profitent des derniers beaux jours et de ce poumon vert. Champvert, comme son nom l’indique, autrefois campagne verdoyante aux portes de la ville, a su, avec ses quatre parcs, conserver une végétation, en prolongement d’ailleurs du Parc des hauteurs qui donne à ce quartier une qualité de vie certaine. Le chemin est beau, avec quelques échappées sur des lotissements le bordant, alors que d’autres ont choisit de se barricader dans un enferment plus radical… Chacun chez soi ! Quelques petites mares artificielles ont été aménagées pour conserver, autant que faire se peut, une biodiversité accueillant insectes, batraciens… Un clos bouliste et des jeux de boules sont installés le long de la voie verte. Ils réutilisent les anciennes traverses de voie ferrée pour contenir les boules... La trentaine de mètres du tunnel des Massues, très beau dans l’obscurité, abrite à sa sortie des abris ménagés pour accueillir cette fois-ci des chiroptères, ou plus simplement des chauves souris, en hauteur, et des hérissons dans les parties les plus basses.

Nous empruntons le long cheminement de l’ancienne voie ferrée, entre surplombs et dévers, qui va nous mener dans le Parc de Champvert. Ici se trouve la Villa Neyrand, à l’origine une riche demeure construite en 1913, rappelant quelque peu le style de la Villa Gillet du Parc de la cerisaie dans le 4ème. La belle frise à cheval entre Art Nouveau et Art Déco sous la charpente et les somptueuses boiseries intérieures de cette lugubre bâtisse semblent trahir le faste de son passé déshérité. Le parc est agréable, avec quelques installations de spires de pierres, destinées là encore, à accueillir faune et flore locale, micro-écosystème, ainsi que des « murs à abeilles », celles des villes souvent « abeilles solitaires » contrairement aux abeilles à miel vivant en communautés… dans des ruches que l’on voit de plus en plus souvent dans les villes où l’air serait moins pollué par les pesticides que dans les campagnes ! De retour sur l’ancienne voie ferrée, le chemin est souligné d'un gabion de pierre qui maintient le talus avec une certaine esthétique… Nous parvenons au Parc de la Garde, où nous cherchons, à la lampe de poche, de petites œuvres de land-art disséminées, lucioles lucane cerf-volant et hulottes sculptées. Retour par le même chemin puis la rue Barthélémy Buyer jusqu’au métro Saint-Just. Ces sorties se voulant conviviales,nous terminons notre périple par un excellent repas, cuisine maison, et fraiche, par Colette et Roger tenanciers forts sympathiques, ce qui ne gâche rien. Nous pouvons vous communiquer l’adresse du lieu, pour ceux qui seraient intéressés. En attendant la prochaine proposition de parcours exploratoire.

Visitez l’album photos : https://www.flickr.com/gp/parcoursmetropolitains/185042

0 notes

Photo

Danièle Delorme et Yolande Laffon dans "Minne, l'Ingénue Libertine" de Jacqueline Audry (1950) - adapté du roman "L'Ingénue libertine" de Colette (1909) - juillet 2021.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simone de Beauvoir Dialogos con la Historia

Artículo de Dialogos con la Historia en http://dialogosconlahistoria.com/simone-de-beauvoir/

Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir (París, 9 de enero de 1908 – ibíd. 14 de abril de 1986) fue una escritora, profesora y filósofa francesa defensora de los derechos humanos y feminista.1 Escribió novelas, ensayos, biografías y monográficos sobre temas políticos, sociales y filosóficos. Su pensamiento se enmarca en la corriente filosófica del existencialismo y su obra El segundo sexo, se considera fundamental en la historia del feminismo.3 Fue pareja del también filósofo Jean Paul Sartre.

Juventud Nació en el piso familiar, situado en el parisino bulevar Raspail de París en el marco de una familia burguesa con moral cristiana muy estricta. Era hija de Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir, que trabajó un tiempo como abogado y era un actor aficionado, y de Françoise Brasseur, una mujer profundamente religiosa. Ella y su hermana pequeña Poupette con quien mantuvo siempre una estrecha relación, fueron educadas en colegios católicos.1 Fue escolarizada desde sus cinco años en el Cours Désir, donde solía enviarse a las hijas de familias burguesas. Su hermana menor, Hélène (conocida con el apodo de Poupette), la siguió dos años más tarde.

Desde su niñez, De Beauvoir destacó por sus habilidades intelectuales, que hicieron que acabase cada año primera de su clase. Compartía brillantez escolar con Elizabeth Lacoin (llamada Zaza en la autobiografía de De Beauvoir), que se convirtió rápidamente en su mejor amiga.

Desde adolescente, por otro lado, se rebelaría contra la fe familiar declarándose atea y considerando que la religión era una manera de subyugar al ser humano.1

Después de la Primera Guerra Mundial, su abuelo materno, Gustave Brasseur, entonces presidente del Banco de la Meuse, presentó la quiebra, lo que precipitó a toda la familia en el deshonor y la vergüenza. Como consecuencia de esta ruina familiar, los padres de Simone se vieron obligados a abandonar la residencia señorial del bulevar Raspail y a trasladarse a un apartamento oscuro, situado en un quinto piso sin ascensor en la calle de Rennes. Georges de Beauvoir, que había planeado vivir con el dinero de su esposa y de su familia, vio sus planes defraudados. La culpa que sintió entonces Françoise no la abandonó nunca a lo largo de su vida y la dote desaparecida se convirtió en una vergüenza familiar.

La pequeña Simone sufrió de la situación, y vio como las relaciones entre sus padres se deterioraban poco a poco. Hecho importante en el nacimiento de las ideas políticas feministas de Simone, toda su infancia será marcada por el hecho de haber nacido mujer: su padre no le escondió el hecho de que hubiese deseado un hijo, con el sueño de que hubiese cursado estudios en la prestigiosa Escuela Politécnica de París. Muchas veces le comentó a Simone: «Tienes un cerebro de hombre» de Beauvoir, Simone (1959). Silvina Bullrich, ed. Memorias de una joven formal (1967 edición). Apasionado por el teatro, que practicaba como aficionado, compartía este gusto con su esposa y sus hijas, junto con su amor por la literatura. Georges de Beauvoir le indicó a menudo a Simone que, para él «el oficio más bonito es el de escritor»[cita requerida]. Con su esposa, compartía la convicción de que, dada la mediocre condición económica en la que se hallaba la familia, la única esperanza de mejora social para sus dos hijas eran los estudios.

Los De Beauvoir veranearon a menudo en Saint-Ybard, en la propiedad de Mayrignac situada en Correze. El parque, fundado alrededor de 1880 por su abuelo, Ernest Bertrand de Beauvoir, fue adquirido a principios de siglo XIX por el bisabuelo, Narcisse Bertrand de Beauvoir. De Beauvoir narró estos tiempos felices en sus Memorias de una joven formal. El contacto con la naturaleza y los largos paseos solitarios por el campo hicieron surgir en el espíritu de la joven Simone la ambición de un destino fuera de lo común.

Con solamente quince años, ya estaba decidida sobre la forma de este destino: quería ser escritora. Tras haber aprobado el bachillerato en 1925, De Beauvoir empezó sus estudios superiores en el Instituto Católico de París, institución religiosa privada a la que solían asistir las muchachas de buena familia. Allí completó su formación matemática, mientras que ampliaba su formación literaria en el Instituto Sainte-Marie de Neuilly. Tras su primer año universitario en París, logró obtener certificados de matemáticas generales, literatura y latín. En 1926, se dedicó a estudiar filosofía y obtuvo en junio de 1927 su certificado de filosofía general. Tras estas certificaciones, acabó licenciándose en letras, con especialización en filosofía, en la primavera de 1928, tras haber aprobado también unas certificaciones de ética y de psicología. Sus estudios universitarios concluyeron en 1929 con la redacción de una tesina sobre Leibniz, culminación de sus estudios superiores.

La profesora[editar] Tras haber sido profesora agregada de filosofía en 1929, De Beauvoir, o Castor, apodo que le dio su amigo Herbaud y que Sartre siguió usando, en un juego de palabras entre «Beauvoir» y beaver, en inglés,5 se preparó para ser profesora titular. Su primer destino fue Marsella. Sartre obtuvo a su vez un puesto en Le Havre en marzo de 1931 y la perspectiva de separarse de él destrozó a De Beauvoir. Para que pudiesen ser nombrados en el mismo instituto, Sartre le propuso que se casasen a lo que ella se negó. En La fuerza de las Cosas, explicó el porqué:

Tengo que decir que no pensé en aceptar aquella propuesta ni un segundo. El matrimonio multiplica por dos las obligaciones familiares y todas las faenas sociales. Al modificar nuestras relaciones con los demás, habría alterado fatalmente las que existían entre nosotros dos. El afán de preservar mi propia independencia no pesó mucho en mi decisión; me habría parecido artificial buscar en la ausencia una libertad que, con toda sinceridad, solamente podía encontrar en mi cabeza y en mi corazón. El año siguiente, logró acercarse a Sartre al ser trasladada a Ruán, donde conoció a Colette Audry, que ejercía también de profesora en el mismo liceo. Mantuvo relaciones amorosas con algunas de sus alumnas, entre ellas, Olga Kosakiewitcz y Bianca Bienenfeld: el pacto que la unió a Sartre le permitía conocer estos “amores contingentes”. También mantuvo una breve relación con un alumno de Sartre, apodado “el pequeño Bost,6 futuro marido de Olga. Sartre también cortejó a la muchacha, sin conseguir conquistarla.

Este grupo de amigos, que se llamaban entre ellos «la pequeña familia», permaneció unido hasta la muerte de sus miembros, pese a las tensiones ligeras o a los conflictos más serios que atravesaron. Poco antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, la pareja Sartre-De Beauvoir fue destinada a París. De 1936 a 1938, De Beauvoir enseñó en el liceo Molière, del que fue despedida tras haber entablado una relación amorosa con Bianca Bienenfeld, una de sus alumnas[cita requerida].

Las editoriales Gallimard y Grasset rechazaron su primera novela, Primaldad de lo espiritual, escrita entre 1935 y 1937, que se publicó tardíamente en 1979 con el título Cuando predomina lo espiritual. La Invitada se publicó en 1943; en esta novela, la escritora describía, mediante personajes ficticios, la relación entre Sartre, Olga y ella misma, a la vez que elaboraba una reflexión filosófica sobre la lucha entre las consciencias y las posibilidades de la reciprocidad. Fue un éxito editorial inmediato que la llevó a ser suspendida en junio de 1943 de la Educación Nacional, tras la presentación de una denuncia por incitación a la perversión de personas menores en diciembre de 1941 por la madre de Nathalie Sorokine, una de sus alumnas. Se la reintegró como profesora tras la Liberación; durante la Ocupación trabajó para la radio libre francesa («Radio Vichy»), donde organizó programas dedicados a la música.

La escritora comprometida[editar] Con Sartre, Raymond Aron, Michel Leiris, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Boris Vian y otros intelectuales franceses de izquierda, fue la fundadora de una revista, Les Temps Modernes, que pretendía difundir la corriente existencialista a través de la literatura contemporánea. De forma paralela, continuó sus producciones personales: tras la publicación de varios ensayos y novelas donde hablaba de su compromiso con el comunismo, el ateísmo y el existencialismo, consiguió independizarse económicamente y se dedicó plenamente a ser escritora. Viajó por numerosos países (EE. UU., China, Rusia, Cuba…) donde conoció a otras personalidades comunistas como Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Mao Zedong o Richard Wright. En los Estados Unidos, entabló una relación pasional con el escritor americano Nelson Algren con quien mantuvo una intensa relación epistolar, llegando a intercambiar unas trescientas cartas.

Su consagración literaria tuvo lugar el año 1949: la publicación de El segundo sexo, del que se vendieron más de veintidós mil ejemplares en la primera semana, causó escándalo y fue objeto de animados debates literarios y filosóficos. La Santa Sede, por ejemplo, se mostró contraria al ensayo. François Mauriac, que siempre tuvo animosidad hacia la pareja, publicó en Les Temps Modernes un editorial que creó polémica al afirmar: «ahora, lo sé todo sobre la vagina de vuestra jefa». El segundo sexo se tradujo a varios idiomas: en los Estados Unidos, se vendieron un millón de ejemplares, y se convirtió en el marco teórico esencial para las reflexiones de las fundadoras del movimiento de liberación la mujer. De Beauvoir se convirtió en precursora del movimiento feminista al describir a una sociedad en la que se relega a la mujer a una situación de inferioridad. Su análisis de la condición femenina, en ruptura con las creencias existencialistas, se apoya en los mitos, las civilizaciones, las religiones, la anatomía y las tradiciones. Este análisis desató un escándalo, en particular el capítulo dedicado a la maternidad y al aborto, entonces equiparado al homicidio. Describía el matrimonio como una institución burguesa repugnante, similar a la prostitución en la que la mujer depende económicamente de su marido y no tiene posibilidad de independizarse.

Los Mandarines, publicado el 1945, marcó el reconocimiento de su talento literario por la comunidad intelectual: se le otorgó por esta novela el prestigioso Premio Goncourt. De Beauvoir era por entonces una de las escritoras con más audiencia a nivel mundial. En esta novela, que trata de la posguerra, expuso su relación con Nelson Algren, aunque siempre a través de personajes ficticios. Algren, celoso, ya no aguantaba más la relación que unía a De Beauvoir y Sartre: la ruptura entre ella y Algren demostró la fuerza del lazo que unía a los dos filósofos, y la de su pacto. Posteriormente, de julio de 1952 a 1959, De Beauvoir vivió con Claude Lanzmann.

A partir de 1958, emprendió la escritura de su autobiografía, en la que describe el mundo burgués en el que creció, sus prejuicios, sus tradiciones degradantes y los esfuerzos que llevó a cabo para deshacerse de ellos pese a su condición de mujer. También relata su relación con Sartre, que calificó de éxito total. Pese a todo y a la fuerza del lazo pasional que aún los unía, ya no eran una pareja en el sentido sexual, aunque De Beauvoir se lo hiciese creer a sus lectores.

En 1964, publicó Una muerte muy dulce, que relata la muerte de su madre: Sartre consideró siempre que éste fue el mejor escrito de De Beauvoir. La eutanasia o el luto forman el núcleo de este relato cargado de emoción. A lo largo de su luto, a la escritora le acompaña una muchacha que conoció entonces: Sylvie Le Bon, estudiante en filosofía. La relación que unió a las dos mujeres era ambigua: madre-hija, de amistad o de amor. En su cuarto escrito autobiográfico, Final de cuentas, De Beauvoir declaraba que compartió con Sylvie el mismo tipo de relación que la unió, cincuenta años antes, a su mejor amiga Zaza. Sylvie Le Bon fue adoptada oficialmente como hija por la escritora, y se la nombró heredera de su obra literaria y de sus bienes.

Muerte de Sartre y final de la vida de Beauvoir[editar] Tras la muerte de Sartre en 1980, publicó en 1981 La ceremonia del adiós, donde relató los diez últimos años de vida de su compañero sentimental: los detalles médicos e íntimos de la vida del filósofo fueron mal recibidos por muchos de sus seguidores. Este texto se completó con la publicación de sus conversaciones con Sartre grabadas en Roma entre agosto y septiembre de 1974. En estos diálogos, Sartre reflexionaba sobre su vida y expresaba algunas dudas sobre su producción intelectual. Al publicar estas conversaciones íntimas, De Beauvoir pretendió demostrar cómo su difunta pareja había sido manipulada por el filósofo y escritor francés Benny Lévy: éste hizo que Sartre reconociera una cierta «inclinación religiosa» en el existencialismo, pese a que Sartre y los demás existencialistas hubiesen proclamado siempre que el ateísmo era uno de sus pilares. Para De Beauvoir, Sartre ya no disponía de la plenitud de sus capacidades intelectuales cuando había sostenido este debate con Lévy y no estaba en situación de enfrentarse a éste filosóficamente. En estos textos que desvelan la vida de Sartre, también dejó ver lo mala que fue su relación con la hija adoptiva de Sartre, Arlette Elkaïm-Sartre. Concluye La Ceremonia del adiós con la frase siguiente: «Su muerte nos separa. Mi muerte no nos reunirá. Así es; ya es demasiado bello que nuestras vidas hayan podido juntarse durante tanto tiempo».

De 1955 a 1986, residió en el número 11bis de la calle Victor-Schœlcher de París, donde murió acompañada de su hija adoptiva y de Claude Lanzmann. Se la enterró en el cementerio de Montparnasse de la capital francesa, en la división 20, al lado de Sartre. Simone de Beauvoir fue enterrada llevando en su mano el anillo de plata que le regaló su amante Nelson Algren al despertar de su primera noche de amor.

Relaciones personales[editar] A lo largo de su período universitario en París, Simone de Beauvoir conoció a otros jóvenes intelectuales, entre ellos Jean-Paul Sartre, que calificó con admiración de genio. Una relación mítica nació entre los dos filósofos, que sólo acabó con la muerte de Sartre. Simone será su «amor necesario», en oposición a los «amores contingentes» que los dos conocerán de forma paralela: un pacto de polifidelidad, que renovaban cada dos años, se estableció entre ellos a partir de 1929, más o menos un año tras su encuentro. Ambos cumplieron este pacto filosófico: él tuvo muchos amores contingentes, ella no tantos. El clímax de la carrera universitaria de la pareja sucedió en 1929, cuando Sartre y De Beauvoir se presentaron al concurso de la agregación de filosofía, que ganó él mientras ella quedaba en segundo puesto.

Pese a este éxito, la muerte repentina de su amiga Zaza el mismo año causó un gran sufrimiento a la filósofa. De Beauvoir, criada por una madre religiosa, perdió su fe cristiana con catorce años, tal como relató en sus Memorias de una joven formal:7 años antes de sus estudios filosóficos, la joven se había emancipado de su familia y de sus valores burgueses.

El encuentro con Sartre supone para De Beauvoir el comienzo de una vida de permanente diálogo intelectual con un interlocutor privilegiado de un nivel que ella definía como mayor al suyo, al menos al inicio de la relación. Sartre y De Beauvoir no se separaron desde que se conocieron, ni durante la separación de ésta de su familia. Su relación perduró hasta la muerte de Sartre. Sin embargo, nunca se casaron ni vivieron bajo el mismo techo. Ambos vivieron en completa libertad, practicando el poliamor y sintiéndose felices con el lazo que habían creado entre ellos. Este esquema relacional novedoso se cimentaba en el rechazo profundo y visceral del modo de vida burgués.

Simone se creía única, pero ante Sartre tuvo que reconocer: «Era la primera vez en mi vida que yo me sentía intelectualmente dominada por alguno». Decidieron unir sus vidas, pero en un amor libre porque ni De Beauvoir ni Sartre aceptaban el matrimonio:

Sartre no tenía la vocación de la monogamia; le gustaba estar en compañía de las mujeres, a las que encontraba menos cómicas que los hombres; no comprendía, a los veintitrés años, el renunciar para siempre a su seductora diversidad.[cita requerida] 8

De todos modos ella lo amó y lo aceptó tal como era. Sartre propuso la fórmula de su relación: «Entre nosotros se trata de un amor necesario, pero conviene que también conozcamos amores contingentes[cita requerida]»

Obra literaria[editar] Durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial y la ocupación alemana de París, vivió en la ciudad tomada escribiendo su primera novela, La invitada (1943), donde exploró los dilemas existencialistas de la libertad, la acción y la responsabilidad individual, temas que abordó igualmente en novelas posteriores como La sangre de los otros (1944) y Los mandarines (1954), novela por la que recibió el Premio Goncourt.1

En 1945 junto a Jean Paul Sartre y otros eruditos del momento fundaron la revista Tiempos Modernos

Las tesis existencialistas, según las cuales cada uno es responsable de sí mismo, se introducen también en una serie de obras autobiográficas, cuatro en total, entre las que destacan Memorias de una joven de buena familia (también conocida como Memorias de una joven formal) (1958) y Final de cuentas (1972). Sus obras ofrecen una visión sumamente reveladora de su vida y su tiempo.

Entre sus ensayos destaca El segundo sexo (1949), un análisis sobre el papel de las mujeres en la sociedad y la construcción del rol y la figura de la mujer; La vejez (1970), centrada en la situación de la ancianidad en el imaginario occidental y en donde criticó su marginación y ocultamiento, y La ceremonia del adiós (1981), polémica obra que evoca la figura de su compañero de vida, Jean Paul Sartre.

Además de sus aportaciones en el feminismo cabe destacar sus reflexiones sobre la creación literaria, sobre el desarrollo de la izquierda antes y después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, sobre el dolor y la percepción del yo, sobre los linderos del psicoanálisis y sobre las premisas profundas del existencialismo.

Feminismo[editar] Simone de Beauvoir definió el feminismo en 1963 como una manera de vivir individualmente y una manera de luchar colectivamente explica la doctora en filosofía, Teresa López Pardina una de las principales especialistas en la figura de la escritora y filósofa francesa.9

No se nace mujer, se llega a serlo[editar] Artículo principal: El Segundo Sexo Beauvoir sostiene que “la mujer” o lo que entendemos por mujer es un producto cultural que se ha construido socialmente. Denuncia que la mujer se ha definido a lo largo de la historia siempre respecto a algo (como madre, esposa, hija, hermana) y reivindica que la principal tarea de la mujer es reconquistar su propia identidad específica y desde sus propios criterios. Las características que se identifica en las mujeres no les vienen dadas de su genética, sino por cómo han sido educadas y socializadas. Como resumen de este pensamiento escribió una de sus frases más célebres: “No se nace mujer, se llega a serlo”

Una voz solitaria denunciando la situación de las mujeres[editar] En 1949 cuando publicó “El Segundo Sexo” era una voz solitaria en la sociedad occidental en la que tras el movimiento sufragista y la obtención del derecho al voto femenino se había vuelto a recluir a las mujeres en el hogar. El libro que en su momento fue un escándalo y que con el tiempo se está considerado un “clásico” que permite hacer balance del recorrido hacia la igualdad de los sexos señala la filósofa Alicia Puleo. Las teóricas de las distintas y contrapuestas corrientes del feminismo (liberal, radical y socialista) que resurgiría en los años sesenta después de un largo paréntesis de silencio -señala Puleo- reconocer ser “hijas de Beauvoir”.10

Referencia en las políticas de igualdad y los estudios feministas[editar] El ser humano considera Beauvoir no es una “esencia” fija sino una “existencia”: “proyecto”, “trascendencia”, “autonomía”, “libertad” que no puede escamotearse a un individuo por el hecho de pertenecer al “segundo sexo”. La idea fundamental de El Segundo Sexo -destaca Puleo- es hoy asumida por millones de personas que no han leído esta obra ni han oído hablar de ella y sus principios han sido incorporados a las políticas de igualdad europeas y han dado lugar a los estudios feministas y de género de centros universitarios de vanguardia.10

Beauvoir expresó en los términos de la filosofía existencialista todo un ciclo de reivindicaciones de igualdad de las mujeres que comienza con la Ilustración y lleva a la obtención del voto y al acceso a la enseñanza superior en primer tercio del siglo XX destaca la filósofa Celia Amorós.11

Lucha por el derecho al aborto[editar] Beauvoir tuvo también un papel determinante en la legalización del aborto en Francia. Con Halimi fundó el movimiento Choisir y fue una de las redactoras del Manifiesto de las 343 -firmado por mujeres de la política, la cultura y distintas áreas de la sociedad francesa como la escritora Marguerite Duras, la abogada Gisèle Halimi o las cineastas Françoise Sagan, Jeanne Moreau y Agnes Vardà reconociendo haber abortado- publicado el 5 de abril de 1971 por la revista Le Nouvel Observateur.12

Sobre el aborto señaló:

“El aborto es parte integral de la evolución en la naturaleza y la historia humana. Esto no es un argumento ni a favor o en contra, sino un hecho innegable. No hay pueblo, ni época donde el aborto no fuera practicado legal o ilegalmente. El aborto está completamente ligado a la existencia humana…”.13

La actividad de Simone de Beauvoir fue, junto con la Gisèle Halimi y Elisabeth Badinter, clave para lograr el reconocimiento de los malos tratos sufridos por las mujeres durante la guerra de Argelia.

Premio Simone de Beauvoir[editar] En 2008 con motivo del centenario del aniversario de su nacimiento se creó en su honor el Premio Simone de Beauvoir por la Libertad de las Mujeres a iniciativa de Julia Kristeva financiado por la Universidad Diderot de París con un montante de 20.000 euros para destacar a las personas comprometidas por su obra artística y su acción a promover la liberad de las mujeres en el mundo.14 Controversias[editar] La relación entre la escritora y Jean-Paul Sartre y su posición en relación al poliamor han generado numerosas controversias sobre el tipo de relación que mantenían.15 También la firma en 1977 de Simone De Beauvoir junto a Jean Paul Sartre y otros intelectuales de izquierda contemporáneos de una petición solicitando la liberación de dos hombres arrestados por haber mantenido relaciones sexuales con menores de edad publicada en Le Monde en 1877.16

Obras[editar] Películas[editar] “Violette” “Les Amants du flore” Novelas[editar] La invitada. (1943) La sangre de los otros (1945) Todos los hombres son mortales (1946) Los mandarines (1954, ganadora del Premio Goncourt). Las bellas imágenes (1966) La mujer rota (1968) Cuando predomina lo espiritual (1979)

Simone de Beauvoir y Jean-Paul Sartre entrevistan al Che Guevara en 1960. Foto de Alberto Korda publicada en la revista Verde Oliva. Museo Che Guevara (Centro de Estudios Che Guevara en La Habana, Cuba).

Tumba de Simone de Beauvoir y Jean-Paul Sartre. Ensayos[editar] Para qué la acción (1944) Para una moral de la ambigüedad (1947) El existencialismo y la sabiduría de los pueblos (1948) América al día (1948) El segundo sexo (1949) El pensamiento político de la derecha (1955) La larga marcha (Ensayo sobre China) (1957) La vejez (año 1970) Memorias y diarios[editar] Norteamérica al desnudo (1948) Memorias de una joven formal (1958) La plenitud de la vida (1960) La fuerza de las cosas (1963) Una muerte muy dulce (1964) Final de cuentas (1972) La ceremonia del adiós (1981) Diario de guerra: septiembre de 1939-enero de 1941 (edición póstuma a cargo de Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir) (1990) Cahiers de jeunesse, 1926-1930. Edición a cargo de Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir. Gallimard, 2008. (Inédito en español) Teatro[editar] Las bocas inútiles (1945) Correspondencia[editar] Cartas a Sartre (1990) Cartas a Nelson Algren: un amor transatlántico (1998) Correspondance croisée avec Jacques-Laurent Bost (1937-1940). Edición, presentación y notas de Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir. Gallimard, 2004. (Inédito en español)

0 notes

Text

International Women Pioneers of Cinema By Raquel Stecher

Early women filmmakers are enjoying a renaissance; one they so rightly deserve. Documentary series like Mark Cousins’ WOMEN MAKE FILM help amplify the filmmakers who struggled within the confines of a male-dominated industry to make a space for themselves. These talented women deserve to be appreciated for their sheer talent, perseverance and of course their wonderful films. Let’s take look at some of the more obscure female directors from outside of the English-speaking world and how they paved the way for filmmakers to come.

youtube

For Bulgarian director Binka Zhelyazkova, filmmaking was a means of protest. Fighting back against her home country’s communist regime, each of her films offered its own cutting political critique. Her first film LIFE FLOWS QUIETLY BY… (’57), for which she served as assistant director to Anton Marinovich, was banned by the Bulgarian Communist Party for 30 years and finally released in 1988. Zhelyazkova forged on. She continued to make bold films with strong anti-fascist themes. Her films were often banned in Bulgaria yet highly regarded elsewhere in Europe and beyond. She had a keen eye for creating atmospheric and visually stunning films and was heavily influenced by Italian Neo-Realism, French New Wave and Russian cinema. With her directorial debut WE WERE YOUNG (’61), a haunting love story about two young resistance fighters, she became the first Bulgarian woman to direct a feature-length movie.

Austrian-Hungarian Jewish director Leontine Sagan is best known for her seminal lesbian film MADCHEN IN UNIFORM (’31). A pupil of Max Reinhardt, she trained as both an actress and a theater director. She saw an opportunity to try her hand at filmmaking when she came across German-Hungarian playwright Christa Winsloe’s story of a young woman at an all-girls boarding school who falls in love with her headmistress. Sagan’s MADCHEN IN UNIFORM is extraordinary for being the first feature film to portray lesbian love and for being female driven with a story by a woman writer with a woman director and an all-female cast. The film was a success, garnering rave reviews. Although Nazi politician Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary that it was “magnificently directed, exceptionally natural and exciting film art,” the Nazi regime publicly made an attempt to destroy all copies of the film. Sagan was courted by MGM’s David O. Selznick, who quickly became a fan of her work and invited her to Hollywood. While this didn’t quite pan out, Sagan did go on to direct two British films MEN OF TOMORROW (’32) and GAIETY GEORGE (’46).

Following in the footsteps of Leontine Sagan was French director Jacqueline Audry. OLIVIA (’51) was based on Dorothy Bussy’s autobiographical novel which itself was inspired by MADCHEN IN UNIFORM as well as Colette Claudine’s novels. The story also takes place in an all-girls boarding school but instead of the Prussian Empire we get Belle Epoque France. Audry got her start as a script supervisor before working as an assistant director under the tutelage of Max Ophuls and G.W. Pabst. Her first solo success was GIGI (’49), one of three Colette stories she would adapt to screen. Even in an industry dominated by men, Audry made a space for herself directing films that featured complex and interesting female characters. She told subversive stories through conventional narratives with an eye towards literary adaptations with strong sexual themes. With the French New Wave, Audry’s style of filmmaking became quickly outdated and she was mostly forgotten. Decades later her work, especially OLIVIA, is finally getting the recognition she deserved.